Abstract

Background/Objectives: This article brings forward a novel methodology for the intra-op approach of forearm amputation stumps to facilitate their subsequent wireless connection to a neural prosthesis. A neural prosthesis offers the amputee more motor functions compared to myoelectric prostheses, but the neural prosthesis must be connected to the patient’s stump nerves. Methods: An experimental animal study was conducted on 15 Wistar rats. Under anesthesia, the sciatic nerve was carefully dissected and preserved using a folding technique to maintain maximum length without tension. Nerves were repositioned with consideration for future use with biocompatible conduits. Morphometric measurements (nerve length, external diameter, fascicle count) were performed, followed by statistical analysis of length–diameter correlations. Results: The techniques show that the length of the nerves in the amputation stump can be preserved and integrated into the muscle masses with appropriate methods and biomaterials, which ensures the transmission of motor impulses to control the movements of a prosthesis. Fibrosis and mechanical injury have a lower risk of occurring with the nerves protected in the muscle mass. Through statistical analysis we find that sciatic nerve length and diameter have a positive correlation (r = 0.71, p = 0.003), supporting anatomic plausibility for human extrapolation of results. Conclusions: The amputation technique preserves much of the nerve length and viability and is simple to perform. Neural electrode implantation can be facilitated by folding the nerve within a large muscle mass and using biomaterial conduits. Better rehabilitation of the patient may occur with the use of a prosthesis equipped with more functions and superior control.

1. Introduction

Traumatic injuries of the upper extremities are common. In Europe, the incidence of hand injuries ranges from 7 to 37 cases per 1000 inhabitants per year. Nerve injuries occur at an estimated rate of 0.14 cases per 1000 inhabitants per year, with the nerves of the upper extremities being the most frequently affected [1]. Despite medical and surgical advances, amputation remains a major global problem [2], with the World Health Organization reporting that over 50 million people (0.5–0.8% of the world population) have experienced limb loss in the past decade, increasing by at least one million annually [3,4]. The highest number of upper-limb amputations occurs in East Central Asia (7 million), followed by Europe (4 million), South Asia (4 million), Africa (2 million), North America (2 million), and the Middle East (1 million) [5]. Nearly 40% of upper-limb amputation victims develop post-traumatic stress or pathological grief [6].

Forearm amputations are life-altering events, most often resulting from sudden trauma. The initial priority in treatment is to preserve life, but the ultimate goal is to maintain function [7]. During upper-extremity amputations, the main surgical objective is to retain maximum forearm length and preserve elbow joint mobility, as these factors directly influence post-operative rehabilitation and prosthesis adaptation. The procedure involves creating balanced anterior and posterior skin flaps, ligating the radial and ulnar arteries, and transecting the 20 forearm muscles. The radial, median, and ulnar nerves are also transected and resected to a level where they rest in healthy tissue to prevent neuroma formation and pain. Bone division and contouring of the ulna and radius aim to preserve at least 5 cm of the ulna for better elbow flexion and prosthetic fitting, followed by layered closure of fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and skin [7].

Amputation due to traumatic injury presents significant challenges for both patients and surgeons. Although prosthetic rehabilitation remains a standard approach, most commercially available prostheses—especially myoelectric ones—offer limited motion and lack the dexterity required for complex daily activities such as eating, hygiene, and communication [8]. Reported prosthesis use among upper-limb amputees varies widely between 30% and 80%, with abandonment rates ranging from 20% to over 50%, primarily due to discomfort, inadequate function, and lack of intuitive control [9,10,11]. Current prosthetic technology struggles to effectively capture and utilize neural signals from the residual peripheral nerves, particularly the median and ulnar motor fascicles, which are often damaged or removed during surgery. Furthermore, complications such as neuromas, nerve degeneration, and suboptimal electrode placement hinder the performance of neural prostheses, limiting their ability to replicate natural hand and finger movements [12].

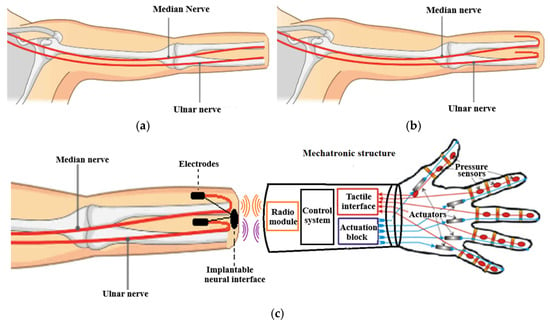

We propose a technique that focuses on preserving both the length and viability of distal peripheral nerves within the stump, as to enhance the success rate of electrode intrafascicular implantation, specifically in cases eligible for neuronal prosthesis (Figure 1). Details regarding the connection of a neural interface to the nerves in the patient’s stump are presented in the papers [13,14].

Figure 1.

Presentation of the method of preserving the median and ulnar nerves from the amputation stump: (a) the classic amputation method; (b) the amputation method with preservation of the median and ulnar nerves for prosthetics; (c) connecting the nerves from the amputation stump to the neural prosthesis.

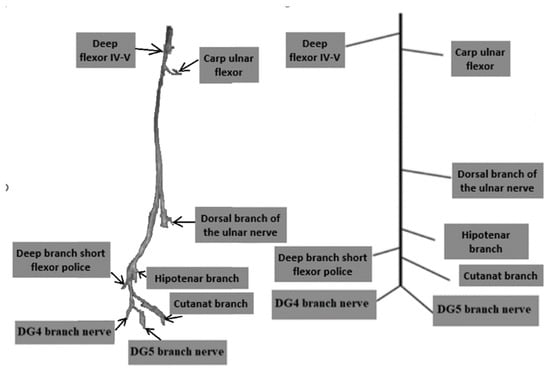

Current prosthetic devices on the market rely on myoelectric control and provide only a limited set of predefined functions, which often do not help patients in performing basic daily activities [15]. Neural prostheses aim to generate finger movements by capturing neural signals from the remaining portions of the median and ulnar nerves within the amputation stump. Obtaining distinct signals from these nerves to control each prosthetic finger independently is challenging. Most of the motor branches of both nerves are lost during the amputation procedure, leaving only the main nerve trunks in the stump. These trunks contain all motor fascicles, which are difficult to distinguish individually, making the acquisition of separate neural signals for each finger movement difficult (Figure 2) [16,17]. The overall 3D structure of the ulnar nerve with all motor and sensory branches is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Fascicular Topography of the ulnar nerve in the forearm and palm for Neuroprostheses and the 3D modelling of ulnar nerve topography [12].

Cortical reorganization after limb amputation is ensured by cortical areas from adjacent territories taking over the lost limb representation area. Amputation does not eradicate relays and connections in these areas, allowing them to be utilized as target for user-prosthesis interface [18,19].

Between 50% and 80% of amputees experience a painful dysesthesic perception in the missing limb, known as phantom limb pain (PLP), which adds to their overall disability. Cortical reorganization in both the motor and somatosensory systems is more pronounced in patients with PLP and is considered its neuro-anatomical substrate [19].

Peripheral nerve interfaces are designed to detect the electrical activity of nerve fibers and/or to selectively stimulate them. From a neuroprosthetic perspective, invasive peripheral nerve interfaces provide a strong balance between the high invasiveness of cortical implants and the low selectivity offered by electroencephalographic (EEG) or electromyographic (EMG) systems. At the same distance from a nerve fiber, large myelinated fibers are detected more effectively than small myelinated or unmyelinated fibers. As a result, tactile or positional sensations can be selectively elicited without triggering pain, while motor signals directed to extrafusal fibers are recorded more easily than signals to intrafusal or autonomic fibers [19].

As alternatives to chronically implanted electrode arrays, techniques such as TMR and surface-skin electrode myoelectric control merit attention. In TMR, the severed residual nerves are surgically transferred and coopted to redundant target muscles, which then serve as intuitive biological amplifiers of cortical motor commands—thereby improving the number and quality of independent control sites for prostheses [20,21,22,23]. The principal advantages of TMR include enhanced intuitive control, increased degrees of freedom and mitigation of neuroma/phantom-limb pain. However, the technique remains surgically demanding, may not always yield stable long-term signal fidelity, and relies on appropriate patient anatomy and rehabilitation. On the other hand, skin-surface EMG-based control remains non-invasive, and the electrode technology is widely available and safe; yet it suffers from limited signal specificity, electrode shift, soft-tissue motion artefacts and lower channel count—all of which reduce the effective selectivity and thus functional dexterity of current myoelectric prostheses [22].

Developing multielectrode arrays with the high pixel densities needed to treat complex deficits has proven difficult. Two major limitations are the local tissue anatomy and the formation of highly resistive scar tissue between the electrodes and the target neurons. Anatomical constraints often prevent placing the prosthesis close to the neurons of interest. Because stimulation efficiency decreases with distance, even a small increase in separation can significantly raise the stimulation thresholds. This problem is made worse by the development of encapsulating scar tissue, which forms as part of the immune response to certain implant materials and can also arise in many degenerative diseases. Scar tissue not only increases the distance between the electrode and the target neurons but also has a higher electrical resistance than native tissue. Together, these factors can raise the stimulation thresholds to levels that exceed safe limits for both tissue and the electrodes. Since tissue damage is partly related to charge density, this becomes a critical concern [24].

Also, the need for improved outcomes in nerve repair and prosthetic function has led to a growing interest in the use of advanced bioengineering techniques, such as nerve conduits, to protect and preserve neural structures at the time of amputation (Figure 1). Nerve conduits, which are often made from biocompatible materials such as collagen or synthetic polymers, have shown promise in promoting nerve regeneration and facilitating the integration of neural interfaces for prosthetic devices. These conduits not only provide structural support but also serve as vehicles for the delivery of neurotrophic factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which are critical for promoting nerve survival and outgrowth after injury [25].

Nerve conduits play a crucial role in this approach by serving as both a protective barrier and a scaffold for nerve regeneration. The materials used for these conduits can be either natural, such as collagen and chitosan, or synthetic, such as silicone polymers. Natural polymers like chitosan and collagen mimic the extracellular matrix and have demonstrated biodegradability and nerve regeneration properties. Synthetic polymers, on the other hand, offer enhanced mechanical and physiological properties, although they must often be removed post-surgery due to their non-degradable nature [26].

Moreover, the conduit will not only protect the nerve but also support localized delivery of neurotrophic factors, which are essential for stimulating nerve repair. These factors, often lacking in sufficient quantities after injury, can be administered through the conduit to promote neuronal survival and guide neurite outgrowth, improving the chances of successful nerve repair and prosthetic integration [27,28].

The primary objective of this study is to introduce a novel surgical approach for the management of traumatic forearm amputation, with a particular focus on preserving the length and viability of distal peripheral nerves within the amputation stump. By employing techniques that protect the remaining motor branches of the median and ulnar nerves, this method aims to enhance the success of electrode implantation for neuronal prostheses. In future investigations, biocompatible nerve conduits will be integrated into the surgical procedure to facilitate the biointegration of electrodes and mitigate common postoperative complications, such as neuroma formation, nerve degeneration, and electrode malposition.

2. Materials and Methods

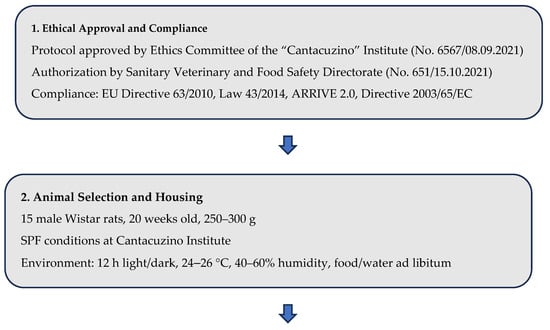

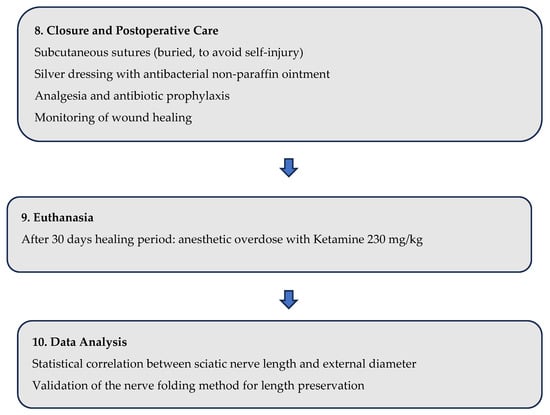

In this study, we utilized 15 laboratory-grade white rats (Rattus norvegicus), anesthesia system, surgical and microsurgical instruments (including scalpel, forceps, and scissors), nerve recording plug electrodes (e.g., needle and wire electrodes compatible with nerve size), sterile gloves, a Hioki 50 LCR HiTester (Nagano, Japan), suture materials, and wound dressing (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Flowchart—Experimental Design and Surgical Procedure (Rat Sciatic Nerve Model).

The experimental procedures adhered to the Public Health Service Policy on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (2015) and were conducted under the oversight of the Romanian Sanitary Veterinary Directorate. This ensured ethical compliance and the humane treatment of the animal subjects.

This study was conducted in strict compliance with the ethical norms regarding the use of animals for scientific purposes. A total number of 15 male Wistar rats, 20-week-old, from the SPF (Specific Pathogen Free) animal breeding facility of the “Cantacuzino” National Military-Medical Institute for Research and Development were used for the research. The animals were housed in the experimental space of the Preclinical Testing Unit of the Cantacuzino Institute, under permanently controlled and monitored conditions: Light-dark cycle 12 h light/12 h dark, ambient temperature 24–26 °C, relative humidity 40–60% and free access to water and food (ad libitum). All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with EU Directive 63/2010, Law 43/2014 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes and the “ARRIVE guidelines 2.0” guide [29] for reporting research using animals. The study protocol was evaluated and received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Medical-Military Research and Development “Cantacuzino” (opinion no. 6567/08 September 2021) and the Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Directorate Bucharest (opinion no. 651/15 October 2021), the study being conducted in a facility authorized for the use of animals for scientific purposes. The authors declare that they have complied with all principles and regulations regarding animal welfare, minimization of suffering and responsible use of laboratory animals in scientific research. The procedure for accessing the sciatic nerve involved general anesthesia of each of the animals with Ketamine (75 mg/kg, Vetased, Farmavet, Bucharest, Romania) and Medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg, DorbeneVet, Biotur, Alexandria, Romania). At the end of the tests, the animals were euthanized by anesthetic overdose (Ketamine 230 mg/kg).

All the procedures from the animal experiments follow the guidelines outlined in the Directive 2003/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 July 2003 amending Council Directive 86/609/EEC on the approximation of laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States regarding the protection of animals used for experimental and other scientific purposes [30,31].

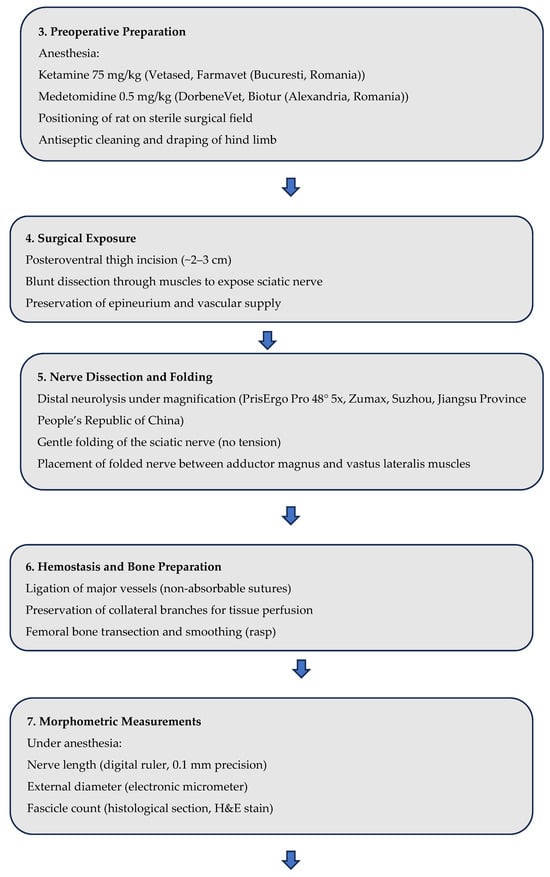

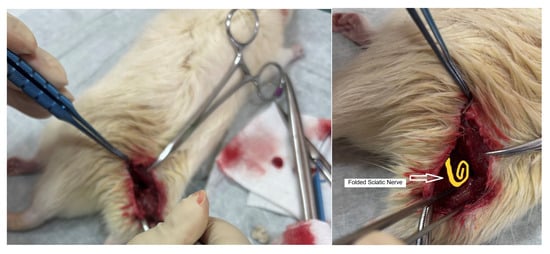

The surgical procedure was carried out under general anesthesia to ensure the comfort and safety of the animals. We scrubbed the area with antiseptic solutions and draped the hind limb with sterile towels. Each rat was anesthetized to ensure immobility and analgesia. The hind limb was cleaned with antiseptic and positioned securely on a sterile surgical tray. A small incision (~2–3 cm) was made along the posteroventral thigh to expose the sciatic nerve. Blunt dissection was carefully performed to separate the surrounding tissues and muscles, taking care not to damage the nerve or its adjacent structures (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Dissection during surgery to access the animal’s sciatic nerve and graphic representation of the folded sciatic nerve.

Taking care not to injure the nerve and its blood supply, its dissection was continued distally with surgical lens (PrisErgo Pro 48° 5x) maintaining its length as much as possible. After dissecting the nerve free from surrounding tissue, while carefully preserving epineurium, a distal neurolysis was performed by sectioning the nerve at its terminal branch so that the nerve was gently folded onto itself (creating a loop shape) without creating tension. A critical aspect of this technique was the folding of the nerve, performed to maintain the maximum possible nerve length without inducing tension. (Figure 4)

This step is vital because excessive tension can lead to ischemia, nerve degeneration, or even rupture. The nerve was then carefully positioned within the locum between the adductor magnus and vastus lateralis muscles, ensuring that it remained protected from mechanical injury and fibrosis during healing. The rationale behind this placement is to provide a natural cushion for the nerve, reducing its exposure to post-surgical trauma while maintaining its structural and functional integrity by minimizing future exposure to fibrosis and neural tissue loss [32].

Additionally, we anticipate the use of “wrap around” conduits (biodegradable such as collagen-based or more active hydrogels made of poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(lactic acid) (PEG-PLA) that can release neurotrophins, which may aid in nerve viability.

To ensure proper hemostasis during the procedure, major vessels in the surgical area were carefully ligated using non-absorbable sutures, to reduce the risk of hematoma formation. Ensuring that the stump remained adequately perfused, while securing the main vessels, we made a deliberate effort to preserve enough collateral branches at the stump level to maintain blood supply to the surrounding soft tissues, for the vascularization needed for skin flap integration, and overall tissue viability, including the neural tissue proximal to the stump

Following vascular control, the femoral bone was transected (in order to simulate local elements of an amputation surgery as close as possible) at the appropriate level using surgical saws. Once the bone was cut, it was meticulously smoothed using a rasp. Smoothing the bone end is a critical step as it prevents sharp edges, which can cause soft tissue irritation or compromise the integrity of overlying skin and muscle tissue (and possibly epineurium damage through pressure). The smoothed bone also reduces the risk of pressure sores or tissue lesions as a tardive post-surgical complication and presents as an issue for prosthetic fitting.

For the morphometric characterization of the experimental model, the sciatic nerve was exposed by careful dissection of the posterior compartment of the thigh, under general anesthesia, according to the previously described protocol. The length of the nerve was measured with a precision digital ruler (0.1 mm) from the point of emergence in the pelvis to the tibial and peroneal bifurcation. The external diameter was determined using a calibrated electronic micrometer in the middle portion of the nerve trajectory. The number of fascicles was assessed by transverse sectioning of distal fragments and histological examination after hematoxylin-eosin staining. These measurements were performed to document individual variability and to validate the plausibility of the experimental technique of preserving nerve length, while providing a comparative data set for future studies.

The skin closure involved the elevation of skin flaps. These flaps were created to provide sufficient coverage over the stump while minimizing tension at the closure site. The skin was then sutured in subcutaneous fashion (by burying the sutures in the subcutaneous tissue, we effectively eliminated any external sutures that the animal could access, thereby preventing complications such as wound dehiscence or infection from self-inflicted trauma) and a silver dressing was applied as a nonadherent tulle with antibacterial properties is impregnated with a neutral ointment, without additives of vaseline or other paraffins. It is not cytotoxic and has an antibacterial effect for at least 7 days, followed by monitoring signs of wound healing complications [33]. Routine post operative treatment (including pain management and antibiotic prophylaxis), following complete healing of the stump at day 30 post-surgery, each rat was anesthetized in the same fashion and euthanized.

3. Results

In this study, we successfully performed a surgical procedure aimed at preserving the nerve length in a rat model by employing a technique of nerve folding. After exposing the sciatic nerve, we carefully dissected it free from the surrounding tissue while ensuring the epineurium remained intact. The nerve was then gently folded, without creating tension, to maintain its maximum possible length. This approach allowed us to secure the nerve within the locum between the adductor magnus and vastus lateralis muscles, offering protection and minimizing the risk of future mechanical injury or fibrosis. We achieved a significantly greater retention of distal nerve length compared to standardized amputation procedures, where the nerve is typically cut shorter.

We established that folding the nerve is a viable method for preserving nerve length during amputation. The technique provides a method for protecting nerves in preparation for future neuronal electrode implantation. The strategic positioning of the nerve stump within the muscle tissue can help shield the nerve from mechanical injury and other external factors., provides a foundation for utilizing biomaterials or nerve conduits in future surgeries, potentially improving neural repair and electrode implantation outcomes.

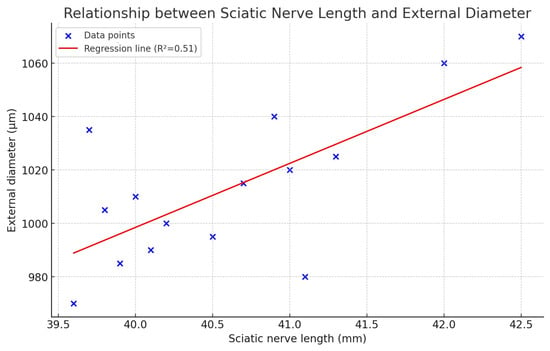

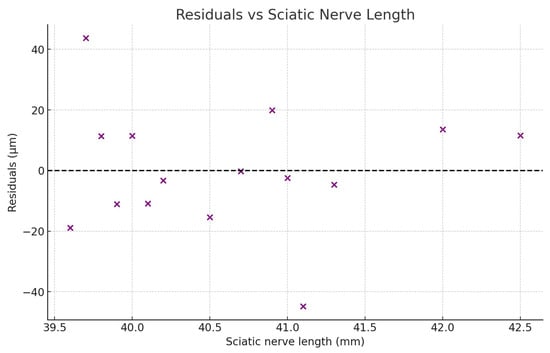

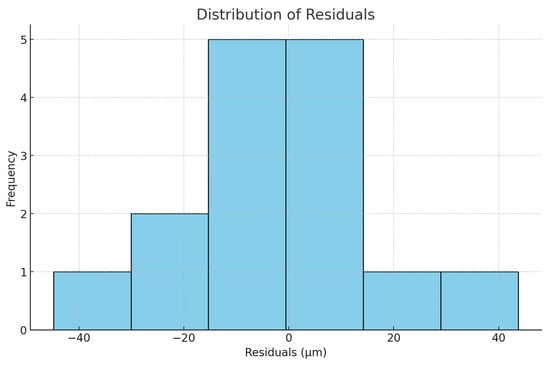

The morphometric measurements of the sciatic nerve in the 15 Wistar rats included in the study (age 20 weeks, males, weight 250–300 g) are presented in Table 1, highlighting the individual variability of length, external diameter and number of fascicles. The relationship between the sciatic nerve length and the measured external diameter is presented in Figure 5, while the residuals versus sciatic nerve length are shown in Figure 6 and the distribution of residuals is shown in Figure 7.

Table 1.

Morphometric measurements of the sciatic nerve in 15 male Wistar rats.

Figure 5.

The relationship between the sciatic nerve length and the measured external diameter.

Figure 6.

The relationship between the residuals versus the sciatic nerve length.

Figure 7.

The distribution of residuals.

4. Discussions

The rat sciatic nerve is widely recognized as the gold standard pre-clinical model for peripheral nerve research and neural interface development due to its anatomical, physiological, and functional homology to human mixed peripheral nerves, including the median and ulnar nerves. Specifically, the sciatic nerve is a large mixed trunk containing both motor and sensory fibers, enclosed within the same hierarchical connective-tissue architecture (endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium) that characterizes human peripheral nerves. These shared structural and cellular features ensure that the fundamental biological processes studied—such as axonal conduction, Wallerian degeneration, regeneration, and excitability—are highly conserved across species [34,35].

From a technical standpoint, the rat sciatic nerve offers several key advantages that make it an optimal first-stage experimental platform. It is relatively large (~1.5–2 mm diameter), easily accessible surgically, and allows for reproducible placement of electrodes or injury models with minimal inter-animal variability [36]. These properties permit detailed functional testing (e.g., electrophysiology, EMG, and behavioral gait analysis) and long-term evaluation of implanted devices under ethically and economically feasible conditions.

Importantly, the functional and compositional similarity between the rat sciatic and human median/ulnar nerves—as mixed motor-sensory pathways responsible for limb movement and tactile sensation—makes findings from sciatic experiments directly informative for upper-limb prosthesis research. Studies of electrical stimulation thresholds, selectivity, and recording fidelity in the sciatic model provide critical parameters that guide scaling and design of interfaces later adapted for human arm nerves [37,38]. Furthermore, biological responses to implants, such as fibrotic encapsulation, inflammatory signaling, and axonal remodeling, are comparable between rodent and human peripheral nerves, making the model predictive of long-term device–nerve interactions [39].

Finally, the use of the rat model aligns with the 3R principles (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) in biomedical research. It provides a scientifically valid and ethically responsible platform for proof-of-concept testing before translation to large-animal models (e.g., pig, non-human primate) and, ultimately, to human median and ulnar nerve applications.

In summary, the rat sciatic nerve represents a biologically relevant, experimentally tractable, and ethically appropriate analog for early-stage investigation of neural prosthesis technologies targeting the human upper limb.

Histological examination of the amputation stump was not performed in this initial study except for a hematoxylin-eosin staining of the end of the distal fragments in order to count the number of fascicles, as meaningful histological and regenerative findings require a longer postoperative period; these assessments will be included in a subsequent study designed to evaluate long-term nerve regeneration and tissue integration.

Our findings suggest that nerve folding during amputation not only preserves the length of the nerve but also creates a safer environment for future surgical interventions by preventing the adherence of the surgically transected nerve to bone or to the subdermal layer. We propose to explore this concept in a subsequent study design.

The formation of scar tissue around implants can impede the conduction of electrical signals between the nerve and the prosthetic device, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the prosthesis. To mitigate this issue, future research will need to focus on developing more biocompatible materials that minimize the body’s immune response. This could include detailed histological analysis to evaluate the long-term preservation of nerve integrity and axonal regeneration. This will provide insight into the effectiveness of the nerve folding technique combined with conduit use, offering further evidence of the method’s potential to improve neuronal electrode implantation and reduce complications like neuromas or nerve degeneration.

Statistical analysis showed that the average length of the sciatic nerve was 40.6 ± 0.86 mm, the average external diameter was 1013.3 ± 28.9 µm, and the number of fascicles varied between 3 and 4, these values being consistent with the ranges reported in the literature for adult Wistar rats [40].

All quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Mean values and standard deviations were calculated for sciatic nerve length, external diameter, and fascicle number. The relationship between nerve length and diameter was evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A linear regression model was used to assess the predictive relationship between the two parameters. Model assumptions were verified through residual analysis and the Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical validity was established.

We looked into the relationship between the sciatic nerve length and the measured external diameter, as this would be relevant to providing an intraoperative prediction of sciatic diameter (relevant to estimating the implant’s dimensions) based on sciatic length, which would vary with height in humans. We found that the sciatic nerve length had a mean of 40.62 mm, with a range of 39.6 mm to 42.5 mm and a standard deviation of 0.86 mm, while the external diameter of the sciatic nerve ranged from 970 µm to 1070 µm, with a mean of 1013.3 µm and a standard deviation of 28.9 µm. The Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was 0.71, and the p-value was 0.003, indicating a moderately strong, statistically significant positive correlation between nerve length and diameter. The regression analysis, with a linear regression model Diameter (µm) = 39.70 + 23.97 × Length (mm), shows that with an R2 = 0.51 about 51% of the variability in diameter can be explained by nerve length. This suggests that longer sciatic nerves tend to have larger diameters—this relationship is statistically significant, although not perfectly predictive, having a moderate correlation.

In the residuals plot these appear randomly scattered around zero, without a clear pattern, suggesting that the linear regression model is appropriate with no major violations of linearity or homoscedasticity. In the histogram they are roughly bell-shaped, without strong skewness or outliers. The Shapiro–Wilk normality test produces W = 0.962 and p = 0.72. Since p > 0.05, we fail to reject the null hypothesis, meaning that the residuals are consistent with a normal distribution.

The technique plans to adapt to current advancements in bioengineering by incorporating a 3D printed nerve conduit. “Recently developed nerve conduits made from combinative materials, using modern technologies possess good mechanical properties and biological functions, ensuring the nerve regeneration.” [16]. These technologies allow for the precise customization of conduit shapes and sizes to match the specific anatomical and physiological requirements of individual patients. By incorporating bioactive molecules such as growth factors into these scaffolds, it is possible to create a microenvironment that actively promotes nerve repair and reduces the likelihood of complications such as neuroma formation.

This combined approach fulfills multiple objectives. By wrapping the nerve end within a specialized conduit, it works to limit fibrosis and prevent nerve adhesion to surrounding muscle tissue. These issues can severely affect nerve function and complicate future surgical procedures.

A major goal of this technique is to minimize, or potentially eliminate, the future surgical resection of the nerve stump. Resection is usually performed to expose healthy nerve tissue. By preserving the integrity of the nerve end, this method may significantly reduce the need for such invasive procedures in future implantations.

Despite the promising outcomes of the nerve folding technique described in this study, several limitations remain. First, while the rat model provides valuable insights due to its anatomical and physiological similarities to humans, the translatability to human patients needs further investigation. Therefore, clinical trials will be essential to validate the safety and efficacy of this technique in human populations.

Another limitation is the variability in nerve regeneration outcomes based on patient-specific factors, such as age, health status (genetic or immune diseases, diabetes mellitus, active infections, nutritional deficits), and the extent of nerve damage from nerve degeneration. Some patients may experience more rapid nerve regeneration than others, and these individual differences must be considered when developing personalized treatment plans. Moreover, the long-term effects of nerve folding and conduit use on neural tissue need to be proven. Future studies will need to focus on monitoring patients over extended periods to assess the durability of these interventions.

When compared with existing literature, our findings are consistent with previous studies that highlight fibrosis and scar tissue formation as major barriers to effective nerve regeneration and electrode implantation. Several experimental investigations on rat sciatic nerve models have demonstrated that post-surgical fibrosis at the nerve repair or folding site can significantly impair neural conductivity and limit the long-term success of neural interfaces [41,42,43,44]. For instance, Hu et al. (2013) reported that excessive collagen deposition and fibroblast proliferation at the nerve repair site hinder axonal sprouting and delay functional recovery [41]. Similarly, Sunderland and Bradley (2010) emphasized that perineural fibrosis following nerve injury or manipulation can restrict nerve gliding and increase mechanical stress, potentially leading to chronic neuropathic pain [42]. Moreover, Lundborg and Hansson (2012) observed in rat sciatic nerve repairs that scar tissue formation around the epineurium created a physical barrier impeding reinnervation and signal transmission [43]. Recent advances using biomaterial nerve conduits—such as chitosan, collagen, or polyglycolic acid scaffolds—have been shown to reduce fibrotic encapsulation and enhance axonal alignment and regeneration at the folding or repair site [44]. These findings are further supported by Jiang et al. (2017), who demonstrated that the application of chitosan-based nerve guidance conduits significantly reduced connective tissue infiltration and improved neural regeneration in rat sciatic nerve models [44]. Collectively, these studies support the rationale behind integrating bioengineered conduits into our nerve folding technique, as they provide a controlled microenvironment that mitigates fibrosis, maintains nerve pliability, and improves the long-term potential for functional reinnervation and electrode implantation. Thus, the present work aligns with prior experimental findings on the rat sciatic model and extends them by proposing a combined nerve folding and conduit-based strategy to preserve nerve length and minimize fibrosis.

Lastly, the integration of advanced neural interfaces with prosthetic limbs is still in its early stages. While progress is being made, significant technical challenges remain, apart from only the technological aspect of the prosthesis.

5. Conclusions

The proposed methodology offers a promising surgical approach for preserving the length and viability of peripheral nerves during limb amputations, particularly in the forearm, by enabling the identification and preservation of functional motor branches of the median and ulnar nerves from the initial amputation stage. These nerves can be integrated into the residual muscle masses using appropriate biomaterials and microsurgical techniques, while careful dissection and folding of the nerves within muscle septa allow for greater nerve length retention compared to traditional methods—an essential factor for future neuronal electrode implantation. The use of nerve conduits to minimize fibrosis and promote regeneration further enhances the potential for successful integration with advanced neural prostheses. Although the technique requires individual customization based on the patient’s biological and anatomical criteria, especially in cases of distal traumatic amputations, it maximizes neural preservation and improves the feasibility of wireless electrode implantation for prosthetic control. By retaining a greater number of motor nerve branches, the method hopes enable the acquisition of richer neural signals, potentially allowing prosthetic hands to perform more precise and diverse movements. Experimental findings from the rat sciatic nerve model revealed a statistically significant positive correlation between nerve length and diameter, validating the approach’s biological foundation. Overall, this innovative surgical strategy could significantly advance the development of prosthetic limbs with enhanced dexterity and control, paving the way for clinical applications that improve long-term patient outcomes and redefine neural-prosthetic integration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G.M.; methodology, W.B.-E.; software, R.D.D.; validation, C.C.; investigation, B.M.B.; resources, L.D.A.; data curation, M.R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, M.-E.P.; supervision, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in strict compliance with the ethical norms regarding the use of animals for scientific purposes. A total of 15 male Wistar rats, 20-week-old, from the SPF (Specific Pathogen Free) animal breeding facility of the “Cantacuzino” National Military-Medical Institute for Research and Development were used for the research. The animals were housed in the experimental space of the Preclinical Testing Unit of the Cantacuzino Institute, under permanently controlled and monitored conditions: Light-dark cycle 12 h light/12 h dark, ambient temperature 24–26 °C, relative humidity 40–60% and free access to water and food (ad libitum). All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with EU Directive 63/2010, Law 43/2014 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes and the “ARRIVE guidelines 2.0” guide [16] for reporting research using animals. The study protocol was evaluated and received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Medical-Military Research and Development “Cantacuzino” (opinion no. 6567/08 September 2021) and the Sanitary Veterinary and Food Safety Directorate Bucharest (opinion no. 651/15 October 2021), the study being conducted in a facility authorized for the use of animals for scientific purposes. The authors declare that they have complied with all principles and regulations regarding animal welfare, minimization of suffering and responsible use of laboratory animals in scientific research. The procedure for accessing the sciatic nerve involved general anesthesia of the animals with Ketamine (75 mg/kg, Vetased, Farmavet, Bucharest, Romania) and Medetomidine (0.5 mg/kg, DorbeneVet, Biotur, Alexandria, Romania). At the end of the tests, the animals were euthanized by anesthetic overdose (Ketamine 230 mg/kg).

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the peculiarities of the software used to record them.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5 for the purposes of graphic figure generation. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. All authors have equally contributed to the realization of this proof-of-concept article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Vancea, C.-V.; Grosu-Bularda, A.; Cretu, A.; Hodea, F.-V.; Al-Falah, K.; Stoian, A.; Chiotoroiu, A.L.; Mihai, C.; Hariga, C.S.; Lascar, I.; et al. Therapeutic strategies for nerve injuries: Current findings and futureperspectives. Are textile technologies a potential solution? Ind. Textila 2022, 73, 704–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurichi, J.E.; Ripley, D.C.; Xie, D.; Kwong, P.L.; Bates, B.E.; Stineman, M.G. Factors Associated with Home Discharge After Rehabilitation Among Male Veterans with Lower Extremity Amputation. PM&R 2013, 5, 408–417. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, M.; Albala, S.; Seghers, F.; Kattel, R.; Liao, C.; Chaudron, M.; Afdhila, N. Applying market shaping approaches to increase access to assistive technology in low- and middle-income countries. Assist. Technol. 2021, 33 (Suppl. S1), 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, C.L.; Westcott-McCoy, S.; Weaver, M.R.; Haagsma, J.; Kartin, D. Global prevalence of traumatic non-fatal limb amputation. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2021, 45, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomares, G.; Coudane, H.; Dap, F.; Dautel, G. Epidemiology of traumatic upper limb amputations. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2018, 104, 273–276. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877056818300331 (accessed on 8 December 2023). [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.; Gonzalez, M.; Romero, A.; Kerns, J. Neuromas of the Hand and Upper Extremity. J. Hand Surg. 2010, 35, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokan, A.; Saber, A.Y. Forearm Amputation. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560932/ (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Apagüeño, B.; Munkwitz, S.E.; Mata, N.V.; Alessia, C.; Nayak, V.V.; Coelho, P.G.; Fullerton, N. Optimal Sites for Upper Extremity Amputation: Comparison Between Surgeons and Prosthetists. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminger, S.; Stino, H.; Pichler, L.H.; Gstoettner, C.; Sturma, A.; Mayer, J.A.; Szivak, M.; Aszmann, O.C. Current rates of prosthetic usage in upper limb amputees- have innovations had an impact on device acceptance? Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 3708–3713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddiss, E.; Chau, T. Upper-limb prosthetics: Critical factors in device abandonment. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2007, 86, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, L.; Borgia, M.; Clark, M. A National Survey of Prosthesis Use in Veterans with Major Upper Limb Amputation: Comparisons by Gender. PM&R 2020, 12, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, T.S.; Henderson, J. Management of traumatic amputations of the upper limb. BMJ 2014, 348, g255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, O.N.; Franti, E.; Carbunaru, V.; Moldovan, C.; Dinulescu, S.; Ion, M.; Dragomir, D.C.; Mihailescu, C.M.; Lascar, I.; Oproiu, A.M.; et al. System of Implantable Electrodes for Neural Signal Acquisition and Stimulation for Wirelessly Connected Forearm Prosthesis. Biosensors 2024, 14, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldovan, C.A.; Ion, M.; Dragomir, D.C.; Dinulescu, S.; Mihailescu, C.; Franti, E.; Dascalu, M.; Dobrescu, L.; Dobrescu, D.; Gheorghe, M.-I.; et al. Remote Sensing System for Motor Nerve Impulse. Sensors 2022, 22, 2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igual, C.; Pardo, L.A., Jr.; Hahne, J.M.; Igual, J. Myoelectric Control for Upper Limb Prostheses. Electronics 2019, 8, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Martínez, I.; Badia, J.; Pascual-Font, A.; Rodríguez-Baeza, A.; Navarro, X. Fascicular Topography of the Human Median Nerve for Neuroprosthetic Surgery. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oproiu, A.M.; Lascar, I.; Dontu, O.; Florea, C.; Scarlet, R.; Sebe, I.; Dobrescu, L.; Moldovan, C.; Niculae, C.; Cergan, R.; et al. Topography of the Human Ulnar Nerve for Mounting a Neuro-Prosthesis with Sensory Feedback. Rev. Chim. 2018, 69, 2494–2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oproiu, A.M.; Lascar, I.; Moldovan, C.; Dontu, O.; Pantazica, M.; Mihaila, C.; Florea, C.; Dobrescu, L.; Sebe, I.; Scarlet, R.; et al. Peripheral Nerve WIFI Interfaces and Electrodes for Mechatronic Prosthetic Hand. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2018, 21, 129–138. [Google Scholar]

- Di Pino, G.; Benvenuto, A.; Tombini, M.; Cavallo, G.; Denaro, L.; Denaro, V.; Ferreri, F.; Rossini, L.; Micera, S.; Guglielmelli, E.; et al. Overview of the implant of intraneural multielectrodes in human for controlling a 5-fingered hand prosthesis, delivering sensorial feedback and producing rehabilitative neuroplasticity. In Proceedings of the 2012 4th IEEE RAS & EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), Rome, Italy, 24–27 June 2012; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 1831–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheesborough, J.E.; Smith, L.H.; Kuiken, T.A.; Dumanian, G.A. Targeted Muscle Reinnervation and Advanced Prosthetic Arms. Semin. Plast. Surg. 2015, 29, 062–072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmeister, K.D.; Salminger, S.; Aszmann, O.C. Targeted Muscle Reinnervation for Prosthetic Control. Hand Clin. 2021, 37, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereu, F.; Leone, F.; Gentile, C.; Cordella, F.; Gruppioni, E.; Zollo, L. Control Strategies and Performance Assessment of Upper-Limb TMR Prostheses: A Review. Sensors 2021, 21, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, A.; Ramsey, M.; Park, S.; Dumanian, G. Targeted Muscle Reinnervation—An Up-to-Date Review: Evidence, Indications, and Technique. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2025, 52, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, J.O.; Cogan, S.F.; Rizzo, J.F. Neurotrophineluting hydrogel coatings for neural stimulating electrodes. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2007, 81B, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Rezza, A.; Kulahci, Y.; Gorantla, V.S.; Zor, F.; Drzeniek, N.M. Implantable Biomaterials for Peripheral Nerve Regeneration–Technology Trends and Translational Tribulations. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 863969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Hao, M.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, L.; Gao, Y.; Jin, Y.; Lei, P.; Zhuo, Y. The application of collagen in the repair of peripheral nerve defect. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 973301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval-Castellanos, A.M.; Claeyssens, F.; Haycock, J.W. Bioactive 3D Scaffolds for the Delivery of NGF and BDNF to Improve Nerve Regeneration. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 734683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Li, D.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Xiao, J. Growth factors-based therapeutic strategies and their underlying signaling mechanisms for peripheral nerve regeneration. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1289–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Sert, N.P.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 242. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2003/65/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council. EUR-Lex—32003L0065—EN. Official Journal L 230, 16/09/2003 P. 0032–0033. 8 December 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ENG/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX%3A32003L0065 (accessed on 8 December 2023).

- Yang, Y.; De Laporte, L.; Rives, C.B.; Jang, J.-H.; Lin, W.-C.; Shull, K.R.; Shea, L.D. Neurotrophin releasing single and multiple lumen nerve conduits. J. Control. Release 2005, 104, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretterklieber, B.; Pretterklieber, M.L.; Kerschan-Schindl, K. Topographical Anatomy of the Adductor Muscle Group in the Albino Rat (Rattus norvegicus). Life 2023, 13, 2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avino, A.; Cozma, C.-N.; Balcangiu-Stroescu, A.-E.; Tanasescu, M.-D.; Balan, D.G.; Timofte, D.; Stoicescu, S.M.; Hariga, C.-S.; Ionescu, D. Our Experience in Skin Grafting and Silver Dressing for Venous Leg Ulcers. Rev. Chim. 2019, 70, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalbruch, H. Fiber composition of the rat sciatic nerve. J. Comp. Neurol. 1986, 243, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuna, S. The sciatic nerve injury model in pre-clinical research. J. Neurosci. Methods 2015, 243, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, X. Functional evaluation of peripheral nerve regeneration and target reinnervation in the rat sciatic nerve model. J. Neurosci. Methods 1998, 8, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Raspopovic, S.; Capogrosso, M.; Petrini, F.M.; Bonizzato, M.; Rigosa, J.; Di Pino, G.; Carpaneto, J.; Controzzi, M.; Boretius, T.; Fernandez, E.; et al. Restoring natural sensory feedback in real-time bidirectional hand prostheses. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 222ra19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, C.E.; Meng, E. A review for the peripheral nerve interface designer. J. Neurosci. Methods 2020, 342, 108775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, H.M.; Mishra, P.; Kohn, J. The overwhelming use of rat models in nerve regeneration research—Translation issues. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 2015, 21, 555–565. [Google Scholar]

- Prodanov, D.; Feirabend, H.K. Morphometric analysis of the fiber populations of the rat sciatic nerve, its spinal roots, and its major branches. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007, 503, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Huang, J.; Ye, Z.; Xia, L.; Li, M.; Zhu, S. Effect of collagen and fibroblast activity on nerve regeneration following sciatic nerve injury in rats. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2013, 101, 2343–2351. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland, S.; Bradley, K.C. The pathology of perineural fibrosis and its clinical significance. Brain 2010, 133, 2332–2344. [Google Scholar]

- Lundborg, G.; Hansson, H.A. Regeneration of peripheral nerves through preformed nerve grafts: Influence of scar formation and axonal growth. Exp. Neurol. 2012, 237, 290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X.; Lim, S.H.; Mao, H.Q.; Chew, S.Y. Current applications and future perspectives of artificial nerve conduits. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 223, 86–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).