Abstract

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is the third most important food crop worldwide and a cornerstone of food security across the Andean region. However, its production is increasingly threatened by the potato psyllid Bactericera cockerelli (Šulc), the vector of Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum, the causal agent of the purple-top complex associated with zebra chip disease, which severely reduces both tuber yield and quality. This study was conducted from September 2024 to February 2025 in the province of Huancabamba, Peru, to evaluate the efficacy of biological and chemical control agents against B. cockerelli under field conditions. A randomized complete block design was implemented with five treatments and four replicates, totaling 20 experimental units, each consisting of 20 potato plants (S. tuberosum L.), of which 10 plants were evaluated. Treatments included an untreated control (T0), a chemical control (thiamethoxam + lambda-cyhalothrin, abamectin, and imidacloprid) (T1), and three biological control agents: Beauveria bassiana CCB LE-265 (>1.5 × 1010 conidia g−1) (T2), Paecilomyces lilacinus strain 251 (1.0 × 1010 conidia g−1) (T3), and Metarhizium anisopliae (1.0 × 1010 conidia g−1) (T4). Foliar applications targeted eggs, nymphs, and adults of the psyllid. Results indicated that B. cockerelli mortality across developmental stages was lower under biological treatments compared with T1, which achieved the lowest probability of purple-top symptom expression (46%) and a zebra chip incidence of 60.60%. Among the biological agents, M. anisopliae (T4) reduced incidence to 56.60%, while P. lilacinus (T3) demonstrated consistent suppression of nymphal populations. In terms of yield, T1 achieved the highest tuber weight (198.86 g plant−1) and number of tubers (7.74 plant−1), followed by T3 (5.08) and T4 (4.24). Nevertheless, all treatments exhibited low yields and small tuber sizes, likely due to unfavorable environmental conditions and the presence of the invasive pest. Overall, chemical control was more effective than biological agents; however, the latter showed considerable potential for integration into sustainable pest management programs. Importantly, vector suppression alone does not guarantee the absence of purple-top complex symptoms or zebra chip disease in potato tubers.

1. Introduction

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.; Solanales: Solanaceae) is currently the third most important food crop worldwide [1,2]. It originated in the Andes of South America, particularly between the regions of Peru and Bolivia, where it was domesticated approximately 7000 to 10,000 years ago [3,4,5]. This center of origin harbors an extraordinary diversity of native potato genotypes, underscoring their cultural and genetic significance to global agriculture [6]. Over time, potato cultivation has diversified into more than 4000 edible varieties, largely as a result of clonal propagation through tubers. This reproductive strategy has contributed to a substantial expansion of its genome, particularly in resistance-related genes compared with sexually propagated Solanaceae crops [7,8].

The potato psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli (Šulc) (Hemiptera: Triozidae), is an oligophagous insect widely distributed across cultivated and natural habitats, feeding mainly on solanaceous hosts [9,10,11]. Native to North America [12], the pest has progressively expanded its distribution to Central America and parts of Europe [13], successfully adapting to semi-arid and temperate climates [14,15]. In Peru, B. cockerelli has been established since 2021, with damage reports dating back to 2019 in the province of Huancabamba [16]. Both nymphs and adults are responsible for transmitting Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum (CLso) [17], the causal agent of the economically important disease complex known as zebra chip (ZC) [4,10,11]. CLso infection directly affects phloem tissues, reducing yields by 35–40% and compromising marketable quality through necrotic streaks, vascular discoloration, and abnormal sprouting, rendering tubers unfit for commercialization [11,18].

As S. tuberosum serves as a primary host for B. cockerelli, its genetic resources face a critical threat from the purple-top complex, which is caused by CLso and transmitted by this psyllid, also known as the tomato–potato psyllid [19]. The disease is characterized by apical chlorosis, foliar reddening or purpling, stunted growth, and internal tuber deformities, often associated with zebra chip symptoms that reduce the commercial value of the crop [20].

In addition to biotic stressors, abiotic factors such as drought also exacerbate potato susceptibility to pest infestation. Water stress significantly impairs plant defense capacity and disrupts nutrient balance [17,21]. In tomato plants subjected to moderate water stress, increased susceptibility to B. cockerelli colonization was observed, as evidenced by higher nymphal survival and adult emergence rates compared to well-watered controls [22]. Moreover, drought conditions often reduce the efficacy of chemical insecticides, promoting resistance within psyllid populations and increasing environmental contamination [23,24]. Vector management for ZC remains heavily reliant on insecticides, a strategy that is neither environmentally sustainable nor economically viable in the long term [11,25]. The indiscriminate use of agrochemicals also contributes to higher production costs and ecological degradation [26].

Given these challenges, sustainable and environmentally compatible alternatives are increasingly necessary. Entomopathogenic fungi such as Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae have emerged as promising candidates for biological control in Peru, demonstrating up to 99% mortality under laboratory conditions and 88% efficacy in the field, comparable to synthetic insecticides [27]. In addition, the nematophagous fungus Paecilomyces lilacinus has been proposed as a biocontrol agent targeting the nymphal stages of B. cockerelli, which are particularly difficult to manage. Its field application is especially relevant under arid conditions, where plant susceptibility to psyllid feeding toxins increases, leading to apical yellowing and leaf curling [28].

This study aimed to (i) evaluate the population dynamics of B. cockerelli under field conditions during the phenological development of potato; (ii) assess the symptom expression of the purple-top complex and zebra chip incidence in the potato cultivar UNICA subjected to biological and chemical treatments; and (iii) determine the agronomic response of the crop to psyllid infestation under field conditions. This integrative approach seeks to identify adaptive management strategies suitable for Andean agroecosystems, where climate variability and phytosanitary pressure increasingly threaten both food security and the genetic diversity of this staple crop.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Meteorological Conditions

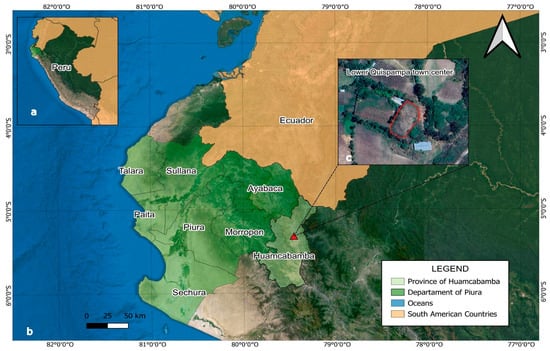

The experiment was conducted in the rural community of Quispampa Bajo, district and province of Huancabamba, Peru, from September 2024 to February 2025, coinciding with the phenological development period of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) (latitude 5°15′22.2048″ S, longitude 79°26′58.0848″ W, elevation 2044 m a.s.l.; Figure 1). The site was selected due to the confirmed presence of the potato psyllid Bactericera cockerelli (Šulc) in local potato fields [16] and the detection of the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum (CLso) in the same district, officially reported in 2024 by the National Agricultural Health Service (SENASA) [29]. At the time of the study’s installation, the research area was surrounded by two potato fields in bloom, an alfalfa field, and a hedge of banana plants. Weed control was carried out manually at three stages: before the first hilling, during the second hilling, and after flowering. Irrigation was carried out every 25 days using surface gravity irrigation, due to the water deficit in the reservoirs in the area. No fungicides were applied, except for the treatment corresponding to chemical control.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the study area: (a) Geographic position of the northern Andes of Peru; (b) Location of Huancabamba Province, Piura; (c) Quispampa Bajo. The red line in the satellite image delimits the experimental area.

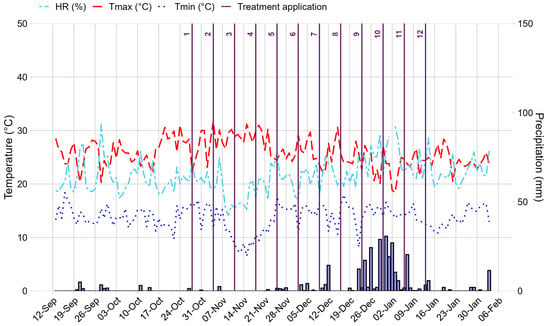

The soils of Quispampa Bajo are heterogeneous, predominantly of alluvial and colluvial origin, with fertility variations related to topographic slope. The soil analysis conducted by the Soil, Water, and Foliar Laboratory of the National Institute of Agrarian Innovation (INIA) determined that the soil belongs to the sandy loam texture class and has the following values: pH: 7.3; electrical conductivity: 16.2 mS/m; organic matter: 2.5%; available phosphorus: 30.3 mg/kg; and available potassium: 707.2 mg/kg. As for exchangeable bases (Ca, Mg, Na, and K), the values were 31.4, 5.0, 0.3, and 2.1 cmol(+)/kg, respectively. Calcium carbonate equivalent: 3.3%, exchangeable acidity: <0.4 cmol (+)/kg, and exchangeable aluminum < 0.4 cmol (+)/kg. Meteorological data—including maximum and minimum air temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and daily precipitation (mm)—were obtained from the Huancabamba Conventional Meteorological Station (Code 105055) managed by the National Service of Meteorology and Hydrology of Peru (SENAMHI/DRD), Directorate of Observation Networks and Data (Figure 2). During the study period, precipitation ranged from 6.9 mm in October to 150.2 mm in December. Average daily temperatures varied between 13.7 °C (minimum) and 25.7 °C (maximum), with a mean relative humidity of 67.5%. Days were generally warm, providing favorable conditions for the development of B. cockerelli populations under natural field exposure. Rainfall during the first three months of crop establishment was very low, below 5 mm per day, reaching values close to 0. Likewise, during October and November of 2024, the maximum temperature exceeded 30 °C.

Figure 2.

Meteorological data of temperature (°C), precipitation (mm), relative humidity (%) and treatment application (weekly) recorded during the field experiment conducted in the community of Quispampa Bajo, Piura Region, Peru from September 2024 to February 2025. The vertical lines represent the moment when the treatments were applied. The lines in the columns represent the time of application of the treatments, which were carried out every seven days.

2.2. Target Insect

The target insect was the potato psyllid (Hemiptera: Triozidae) [30], which was first reported in the United States in the 1920s causing yellowing symptoms in potato plants [31]. This psyllid exhibits seven developmental stages: egg, five immature nymphal instars, and the adult stage [9,13,32]. In this study, the taxonomic identification of B. cockerelli was based on morphological traits observed in the egg (Figure 3a), nymphal (Figure 3b,c), and adult stages (Figure 3d–h), which, according to previous reports, exhibit limited mobility [33].

Figure 3.

Developmental stages of Bactericera cockerelli observed on potato plants of the cultivar UNICA: (a) egg stage; (b) first-instar nymph; (c) flattened fifth-instar nymph; (d) irregular emergence of the adult showing incomplete transition from the nymphal stage; (e) adult psyllid with stable coloration patterns distinguishing the abdomen and thorax—eyes narrower than the mesothorax; (f) adult with golden-yellow body; (g) adult with brown body showing a rhinarium on the fourth antennal segment; (h) copulating mature adults displaying a dark body with a whitish dorsal band on the first abdominal segment; (i) adult with fully expanded wings showing the venation of the anterior wings and white bands on the first and last abdominal segments; (j) whitish secretions on potato foliage; (k) symptoms of the purple-top complex on the UNICA variety; (l) tubers exhibiting zebra-chip symptoms. © G. Cárdenas-Huamán.

2.3. Target Crop

The target crop was potato (Solanales: Solanaceae), which is commonly affected by the psyllid Bactericera cockerelli. The plant material consisted of 400 seed tubers of the variety UNICA (CIP 392797.22), developed by the International Potato Center (CIP, Lima, Peru) and released in 1998 [34]. The seed tubers corresponded to the Pre-Basic Seed Class, as defined in the Specific Potato Seed Regulation of Peru [35]. Planting was performed at a spacing of 0.3 × 1.0 m under field conditions simulating commercial production during the 2024–2025 agricultural season (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Seed tubers of the potato variety UNICA (CIP 392797.22): (a) pre-basic seed; (b) uniform sprouting; (c) development of sprouts and promising root initials; (d) field planting.

The UNICA variety is characterized by slight apical dormancy, with a dormancy period of 40–50 days. It exhibits an early growth cycle, reaching maturity within 70–90 days after sowing (DAS), and may be considered semi-early (90–110 DAS) under low-tropical conditions such as coastal or inter-Andean valleys (0–1500 m a.s.l.). This variety also shows a high yield potential, estimated at 50 t/ha [34].

Agronomic management began with the preparation of the land using oxen or a “yoke.” Furrowing was done manually with a straight spade. For basal fertilization, 500 kg/ha of island guano was applied in a continuous stream. Additionally, a compound fertilizer of NPK 15-5-15 + 2MgO + 3S (Molimax Papa Sierra, MOLINOS & CIA, Lima, Peru) was used at a dose of 189-00-120 kg/ha.

2.4. Experimental Design and Treatments

The experiment was established under a randomized complete block design (RCBD) consisting of five treatments with four replications each, totaling 20 experimental units. Each experimental unit comprised 20 potato plants. Ten fixed plants were evaluated in each experimental unit. Treatments were uniformly applied to all plants within each experimental unit.

The evaluated treatments were as follows: untreated control (T0); chemical control—thiamethoxam + lambda-cyhalothrin, abamectin, and imidacloprid (T1); and three commercial biological control agents: Beauveria bassiana strain CCB LE-265 (>1.5 × 1010 conidia g−1) (T2), Paecilomyces lilacinus strain 251 (1.0 × 1010 conidia g−1) (T3), and Metarhizium anisopliae (1.0 × 1010 conidia g−1) (T4).

Applications were targeted to the egg, nymph, and adult stages of Bactericera cockerelli. Spraying commenced once plants reached 98% emergence, approximately 45 days after sowing (DAS), and was performed directly on all aerial plant organs at seven-day intervals. Treatment protocols followed integrated pest and disease management guidelines for potato cultivation [11,32,36].

2.5. Application Methodology of Treatments

The control treatment (T0) consisted solely of water. All other treatments included an agricultural adjuvant composed of 90% soybean oil and 10% emulsifiers at a dose of 5 mL/L, along with a pH regulator applied at 1 mL/L. In addition, a plant growth promoter formulated as a soluble concentrate (SL), containing indole-3-butyric acid (auxin, 2.84 g/L) and 6-benzylaminopurine (cytokinin, 0.02 g/L), was applied at a rate of 500 mL per 200 L of water during the first three spray applications of the crop cycle.

For the chemical control (T1), in addition to the adjuvant and pH regulator, insecticides were applied in weekly rotation. The commercial insecticides Pupilo, with the active ingredients Thiamethoxam + Lambda-cyhalothrin (141 g/L EC; 106 g/L SC, Trustchem Co. Ltd., Nanjing, China), ABAFIN 1.8 EC, containing the active ingredient Abamectin (18 g/L, ARIS INDUSTRIAL, Lima, Peru), and Kohinor® 350 SC, with the active ingredient Imidacloprid (350 g/L SC, ADAMA Andina B.V., Barranquilla, Colombia), were used. Two formulations were used: Formulation 1: (a) thiamethoxam + lambda-cyhalothrin (200 mL per 200 L) combined with abamectin (300 mL per 200 L), and Formulation 2: (b) thiamethoxam + lambda-cyhalothrin (200 mL per 200 L) combined with imidacloprid (500 mL per 200 L). In T1, two fungicides were applied preventively for foliar disease management: metiram (550 g/kg) + pyraclostrobin (50 g/kg) in WG formulation (2.5 kg/ha), and cymoxanil (80 g/kg) + mancozeb (640 g/kg) in WP formulation (0.5 kg per 200 L). These fungicides were applied every 15 days, totaling four applications during the vegetative stage and one additional application after flowering, following phytosanitary protection recommendations for potato [37].

Suspensions of the biological control agents Beauveria bassiana (formulated product: YURAK WP; Productos Biológicos para la Agricultura E.I.R.L, Lima, Peru), Paecilomyces lilacinus (formulated product: MATANEM WP, Productos Biológicos para la Agricultura E.I.R.L, Lima, Peru), and Metarhizium anisopliae (formulated product: METARIZO WP, Productos Biológicos para la Agricultura E.I.R.L, Lima, Peru) were prepared according to the manufacturers’ technical specifications. Beauveria bassiana (T2; 200 g per 200 L), Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3; 400 g per 200 L), and Metarhizium anisopliae (T4; 200 g per 200 L). To enhance fungal effectiveness, a pH regulator (1 mL L−1) and agricultural oil (5 mL L−1) were added to each mixture. The solution was then stirred until fully homogenized and left to rest under shade for 30 min prior to use to preserve conidial viability [38,39]. To prevent cross-contamination among the three biological agents, separate sprayer tanks were used for each treatment.

All applications were performed in situ under shaded conditions during morning hours at weekly intervals. Manual backpack sprayers equipped with fine-cone nozzles were used to ensure uniform coverage of both adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces, as well as terminal and lateral shoots and stems [40]. To isolate each treatment, plastic barriers were installed between plots. Each plant surface received three uniform spray passes per application. Afterward, all equipment was thoroughly washed and dried before reuse, following operational protocols to maintain both treatment efficacy and biological agent viability [41].

The treatment application schedule is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

2.6. Entomological Variables and Visual Inspection Methodology for Field Assessment of Bactericera cockerelli Life Stages

The quantification of Bactericera cockerelli presence was conducted using a direct visual inspection method based on systematic field counts. The evaluation consisted of recording the number of eggs, nymphs, and adults on potato plants within each experimental unit through visual sampling of aerial organs. Evaluations were conducted weekly for 12 weeks starting at 45 days after sowing (DAS). Ten plants were selected and evaluated at all evaluation times. The entomological variables were assessed on all the leaves across the four quadrants of the plant. Both the adaxial and abaxial leaf surfaces, stems, petioles, lateral and terminal shoots, and flower calyces were inspected throughout the entire vegetative cycle of the crop, following the protocol established by the International Potato Center [42].

Three entomological variables were assessed: (a) number of eggs, (b) number of nymphs, and (c) number of adults, all identified based on the morphological characteristics of the psyllid on plant foliage [43]. Evaluations were performed weekly between 09:00 and 15:00 h under natural light conditions, four days after treatment application, considering that oviposition typically begins between the fourth and fifth day after adult emergence [43].

Egg counts of B. cockerelli (Šulc) were carried out systematically along leaf margins, followed by detailed examination of both leaf surfaces, leaflets, and secondary branch shoots—preferred oviposition sites for females. The primary morphological diagnostic feature of the egg stage is the pedicel, by which the egg is attached to the plant tissue [36]. This method has proven reliable for detecting and quantifying egg populations under field conditions, providing an accurate estimation of initial infestation density [42].

Nymphal stages were evaluated using a portable entomological magnifier (200×) attached to an Android smartphone camera, enabling in situ identification of first through fifth instar nymphs. Diagnostic morphological features included body size, translucent yellow coloration, and the presence of marginal wax filaments [36,44].

Adult psyllids were quantified through careful plant inspection, focusing primarily on the upper foliage, where adults typically congregate, particularly during mating or oviposition on young leaves [36,44]. Adults were identified by their distinct morphological traits: an elongated body of dark brown to black color, transparent wings with clear venation, long segmented antennae, and two characteristic whitish abdominal bands [42,45].

Adult assessments were complemented with an indirect sampling method—yellow sticky traps—following the procedure described by Butler & Trumble (2012) and Cameron et al. [36,46]. The traps were installed around the plot perimeter to monitor population dynamics and weekly fluctuations of the vector in the environment [25]. This trapping method is widely used for monitoring sap-sucking pests due to its high efficiency in tracking population trends of hemipteran vectors such as B. cockerelli [33,36,40].

Twelve rectangular traps (40 × 25 cm per side) were installed around the perimeter of the plot. After counting the adult psyllids, the traps were replaced. Each trap was coated on both sides with the commercial entomological adhesive TEMO-O-CID (NATURE FIRST, Lima, Peru). A total of 192 sticky traps were installed during the study [25]. The traps were fixed to support structures at two heights: 15 cm above the ground level from planting to hilling, and 30 cm thereafter until harvest, following population dynamics criteria reported in previous studies [44]. Traps were replaced weekly after counting the captured adults (Figure 3i). This approach enabled continuous recording of vector population fluctuations, complementing direct plant evaluations and providing a reliable indicator of psyllid pressure within the agroecosystem [45]. Data on adult captures from yellow traps are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

2.7. Agronomic Variables

The agronomic variables evaluated were yield (g/plant) and number of tubers per plant. Yield was quantified as the total fresh weight of tubers obtained per plant, expressed in grams, using a precision balance (T-Scale TB, capacity 3000 g, accuracy 0.1 g). The number of tubers per plant was determined through direct counting of each experimental plant sample.

Both variables were assessed following the standard procedures for potato yield trials described by De Haan et al. at the International Potato Center (CIP) [47]. This protocol involves the individual harvesting of experimental plants, followed by tuber counting and weighing with a precision balance. The method provides reliable estimations of yield parameters under field conditions.

2.8. Methodology for the Diagnosis of the Purple-Top Complex and Zebra Chip Disease

The presence of purple-top symptoms was assessed in field and the incidence of zebra chip disease was assessed in the laboratory, both conditions being associated with infection by Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum transmitted by Bactericera cockerelli [45].

To diagnose the presence of purple-top symptoms in potato plants, a binary categorical scale was used, where 0 = absence and 1 = presence, following the qualitative nature of the variable. This approach has been previously applied to identify phytoplasma-associated symptoms in potato and other crops, allowing accurate recording of disease incidence. Morphological characterization of symptoms associated with the purple-top complex included apical leaf yellowing (Figure 3j), foliar reddening or purpling, chlorotic apical growth, leaf curling, stunting (Figure 3k), leaf deformation and formation of aerial tubers [45,48]. Plants exhibiting more than three of these symptoms were assigned a value of “1” whereas those showing none of the seven described traits were assigned a value of “0”. The probability (%) of the purple-top complex was then calculated for each treatment and replication based on the proportion of symptomatic plants relative to healthy plants, in order to allow the corresponding analysis.

The incidence (%) of zebra chip disease in potato tubers was evaluated using the fresh tuber cross-section method described by Munyaneza [45]. Each harvested tuber from evaluated plants was transversely cut and visually inspected for characteristic symptoms, particularly dark brown to black necrotic streaks in the medullary tissue (Figure 3l). The incidence percentage was subsequently calculated using the formula proposed [49], commonly employed in epidemiological studies to quantify disease incidence and severity. This method enables the morphological characterization of zebra chip symptomatology in potato tubers caused by Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum [45,48].

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 4.5.0 [50]. Data were analyzed using a linear mixed-effects model (LMM), applied using the lme4 package [51], to account for the structure of the experiment and the presence of random factors, providing robustness against potential deviations from normality and homoscedasticity assumptions [52]. Model significance was assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and mean comparisons were performed with Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05) using the emmeans package [53].

The model applied was:

lmer(nda ~ 0 + (1|block) + (1|repetition) + control.type* id_variable)

In this model, nda represents the response variable (number of psyllids), Tipo.de.control (control type) and id_variable (sampling date) are fixed effects, while block and repeticion (replicate) are treated as random effects to account for the hierarchical structure and repeated measures of the experiment. The model can be expressed as:

where

observed value of psyllid count

: overall mean

fixed effect of control type

: fixed effect of sampling date

: = interaction between control type and sampling date

: random effect of block

: random effect of repetition

: residual error

This model structure adequately captures the experimental variability and allows evaluating treatment effects across sampling dates [54,55].

Binary variables (presence/absence), such as the incidence of punta morada, were analyzed using generalized linear models (GLMs) with a binomial distribution. The adequacy of this model was verified through the diagnostic assumptions provided in the Supplementary Figures S1 and S2.

3. Results

3.1. Population Dynamics of the Potato Psyllid

To evaluate the effect of biological and chemical treatments on psyllid population dynamics, the presence of Bactericera cockerelli (Šulc) in its three developmental stages (egg, nymph, and adult) was monitored in the aerial organs of Solanum tuberosum L. var. UNICA through direct visual inspection and insect counts throughout the entire phenological cycle of the crop (Figure 3).

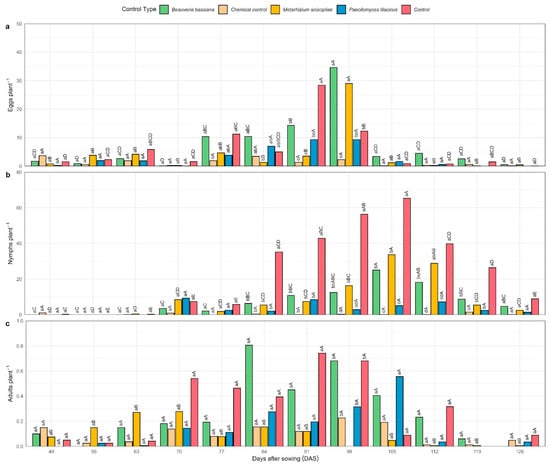

Statistical analysis revealed that egg counts differed significantly among treatments at 77, 91, and 98 days post-installation (dpi) (p < 0.05; Figure 5a). At 77 dpi, treatment T1 exhibited the most effective control with an average of 3.0 eggs, significantly lower than the control T0 (10.9 eggs), but statistically similar to T2 (9.94 eggs), T3 (3.65 eggs), and T4 (4.50 eggs). At 91 dpi, T1 and T4 achieved superior control with 2.0 and 3.0 eggs, respectively, significantly outperforming T0 (28.20 eggs) and T2 (13.75 eggs). Finally, at 98 dpi, T1 maintained the lowest number of eggs (2.17), significantly lower than T0 (11.99), T2 (32.40), and T4 (28.49), while showing no significant difference compared to T3 (8.94). Overall, T1 (chemical control) and T3 (Paecilomyces lilacinus) demonstrated the most stable suppression of egg density during the phenological cycle, with no significant differences across sampling dates (p > 0.05). Their highest mean values were observed at 49 dpi (3.50 eggs) and 98 dpi (8.94 eggs), respectively.

Figure 5.

Evaluation of the pest insect Bactericera cockerelli at its three developmental stages, monitored weekly on the foliar area of potato plants under field conditions in Quispampa Bajo, Huancabamba Province, Piura, Peru. The results of the entomological variables (a) number of eggs, (b) number of nymphs, and (c) number of adults per plant are presented. The comparisons of means were performed using Tukey’s HSD test (α = 0.05). Uppercase letters denote statistically significant differences within each treatment across application time, whereas lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences among treatments in each time.

Significant differences were also observed in nymphal populations at 70, 84, 91, 98, 105, 112, and 119 dpi (p < 0.05; Figure 5b). At 70 dpi, T1 achieved the lowest mean nymph count (0.92), significantly outperforming T3 (9.10) and T4 (8.19). At 84 and 91 dpi, all treated plots exhibited lower nymph numbers than the control (T0). At 98, 105, and 112 dpi, both T1 and T3 sustained the highest suppression of nymphal populations, differing significantly from the remaining treatments. By 119 dpi, T1 maintained the lowest nymph count (1.31), significantly lower than T0 (26.14) and T2 (8.73). Treatments T1 and T3 displayed consistent control throughout the crop cycle, without significant fluctuations (p > 0.05), reaching their maximum means of 1.31 (T1) and 9.10 (T3) nymphs at 119 and 70 dpi, respectively.

Regarding adult populations, significant differences were recorded at 84, 91, 98, and 105 dpi (p < 0.05; Figure 5c). At 84 dpi, T1 and T4 exhibited the greatest control (0.13 adults), significantly lower than T2 (0.67). At 91 dpi, both T1 and T4 again outperformed the control (T0) with 0.09 adults. However, at 98 dpi, T0, T1, T2, and T3 exhibited the lowest adult counts (0.58, 0.54, 0.26, and 0.19 adults, respectively), significantly surpassing T4 (4.44 adults). Treatments T1 and T3 maintained stable adult suppression across the phenological period, showing no significant differences (p > 0.05), with their highest means recorded at 98 dpi (0.19 adults) and 105 dpi (0.46 adults), respectively.

Additionally, a total of 2000 adult psyllids were captured in the 192 adhesive traps installed around the perimeter of the study area, providing consistent evidence of adult vector activity in the experimental field. Detailed data on adult captures in the traps are presented in the Supplementary Table S2.

3.2. Symptomatology of Purple-Top Complex in Plants and Zebra Chip Disease in Potato Tubers

To assess the effect of biological and chemical treatments on the expression of purple-top symptoms in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) var. UNICA under field conditions, the probability of incidence of the purple-top complex and the presence of zebra chip (ZC) were evaluated. The incidence of purple-top was determined based on morphological characteristics observed in the plants, whereas zebra chip incidence was assessed in tubers according to the presence of characteristic necrotic streaks [45,48].

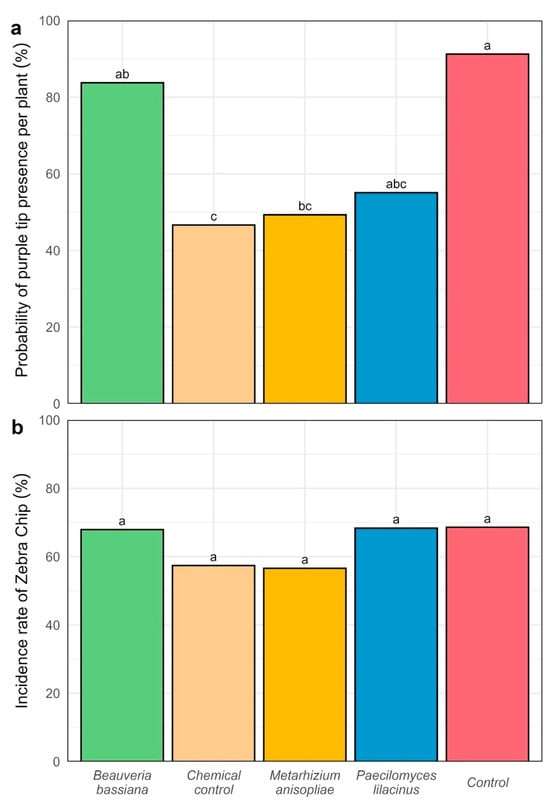

The results showed that the application of treatments produced significant differences (p < 0.05) in the probability of purple-top complex occurrence (Figure 6a). The chemical control (T1) exhibited the lowest probability of symptom presence (46%), significantly lower than T0 (91%) and T2 (83%). Likewise, Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) showed a lower probability of occurrence (49%) compared to T0, T2, and T3, although it differed statistically only from the untreated control (T0).

Figure 6.

Evaluation of purple-top symptomatology in potato plants during the flowering stage of the UNICA variety (CIP 392797.22) (a) Probability of purple-top occurrence in plants (%); Symptoms of zebra chip disease in tubers were identified based on morphological characteristics, including brown splinter-like streaks observed after transverse cutting of harvested tubers. (b) Incidence rate of zebra chip disease (%). Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences (Tukey HSD, p < 0.05).

In contrast, no significant differences (p = 0.778) were observed among treatments for the incidence rate of zebra chip in tubers (Figure 6b). Despite the lack of statistical differences, treatment T4 exhibited the lowest incidence rate (56.60%), while the highest incidence was recorded in the untreated control (T0) with 68.61%.

3.3. Agronomic Response of Potato Crop Under the Presence of Bactericera cockerelli

To evaluate the effect of biological and chemical treatments on the yield performance of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) var. UNICA under field conditions, the number of tubers per plant and fresh tuber weight were determined. Measurements followed the methodology established by the International Potato Center (CIP), which enables the estimation of yield parameters under field conditions while distinguishing treatment effects from environmental influences on crop productivity [47].

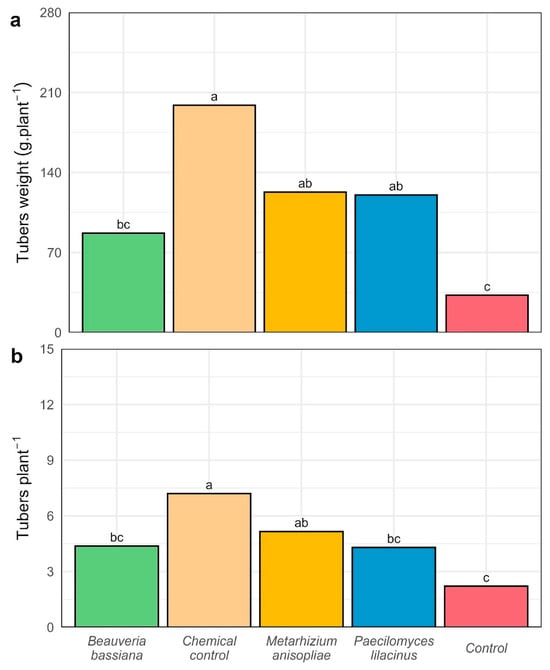

The results showed that the application of treatments produced significant differences (p < 0.05) in tuber fresh weight per plant (Figure 7a). The chemical control (T1) exhibited the highest tuber weight, averaging 198.86 g plant−1, significantly exceeding T0 (32.63 g) and T2 (86.93 g). Similarly, Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3) and Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) significantly outperformed the untreated control (T0), with mean tuber weights of 120.41 g and 122.84 g, respectively.

Figure 7.

Agronomic variables evaluated in the potato variety UNICA (a) tuber weight per plant and (b) number of tubers per plant. Different letters above the bars indicate significant differences (Tukey HSD, p < 0.05).

For the variable number of tubers per plant, treatment effects were also statistically significant (p < 0.05; Figure 7b). The T1 treatment produced the highest value, averaging 7.74 tubers per plant, statistically superior to the other treatments. T2, T3, and T4 also exceeded the control (T0 = 2.16 tubers per plant) with mean values of 4.28, 5.08, and 4.24 tubers per plant, respectively.

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the occurrence of the invasive pest in potato crops in the northern highlands of Peru, the probability of purple-top symptom expression, the incidence rate of zebra chip disease, and the agronomic performance of Solanum tuberosum L. var. UNICA under field conditions. The results demonstrated the differential effects of chemical control (T1) and biological agents (T2, T3, T4) on the pest–disease complex, providing insight into their efficacy, limitations, and potential for integration into sustainable management strategies for potato cultivation under field conditions.

4.1. Analysis of Population Dynamics of the Potato Psyllid

The results obtained for the number of Bactericera cockerelli eggs indicate that the evaluated treatments exerted differential effects throughout the phenological cycle of Solanum tuberosum. The higher initial efficacy observed with the chemical control (T1) at 77 days after installation, compared with the untreated control (T0), can be attributed to the complementary modes of action of thiamethoxam (a systemic neonicotinoid), lambda-cyhalothrin (a contact pyrethroid), and abamectin (a translaminar avermectin). These compounds interfere with feeding behavior and neural signal transmission in hemipterans, thus reducing oviposition rates [56]. Similar findings were reported by Yang et al. [44], who demonstrated that insecticidal treatments can suppress female feeding activity and consequently decrease egg deposition. This combined effect is consistent with studies in which sequential applications of systemic and contact insecticides resulted in rapid suppression of B. cockerelli populations at early developmental stages [17]. At 91 days, the superior performance of Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) and chemical control (T1) compared with Beauveria bassiana (T2) and the control (T0) suggests greater adaptability of M. anisopliae to local environmental conditions. This entomopathogenic fungus demonstrates optimal germination and virulence in climates with temperatures ranging from 25 to 28 °C and relative humidity between 65 and 75%, conditions that match those recorded in Quispampa Bajo [57]. In contrast, B. bassiana tends to exhibit reduced persistence under high solar radiation, which may decrease its medium-term efficacy [57]. At 98 days, Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3) showed efficacy comparable to the chemical control (T1), a noteworthy finding considering that P. lilacinus is primarily a nematophagous fungus, and its application in B. cockerelli management remains relatively novel.

During the nymphal stage, although the chemical treatment (T1) exhibited an initial advantage, all treatments eventually outperformed the untreated control, suggesting that the interaction between field water stress and biological agents may have limited nymphal development [21]. This pattern aligns with the findings of Harrison et al. [58], who reported that abiotic stress can reduce the developmental rate of Bactericera cockerelli by altering the composition of phloem sap. The efficacy of Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3) may be attributed to its ability to colonize plant tissues, which likely allowed it to affect immature nymphal stages internally, thereby explaining the sustained suppression of nymph populations observed in this study. Moreover, studies such as that of Athanassiou et al. [59] have confirmed that Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) remains effective against sap-sucking insects even under conditions of low relative humidity, owing to its capacity to persist within the microclimate of the plant canopy.

In the adult stage, Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) and the chemical control (T1) were the most effective during the initial evaluations, whereas Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3) and T1 maintained consistent suppression of adult populations throughout the crop cycle. Previous research by Pacheco Hernández et al. [60] has demonstrated that entomopathogenic fungi not only cause direct mortality but also reduce longevity and fecundity, contributing to long-term population suppression across successive generations. This effect has been further corroborated by Lacey et al. [40], who emphasized the importance of entomopathogenic fungi as sustainable tools within integrated pest management (IPM) programs. The agroecological context of Quispampa Bajo, characterized by average maximum temperatures of 25.7 °C and relative humidity of 67.5%, is favorable for B. cockerelli development, as this pest thrives in temperate environments with moderate humidity [17]. These environmental conditions promote both rapid insect reproduction and the performance of specific biological control agents. Therefore, synchronizing treatment applications with population peaks is a critical factor for maximizing the efficacy of control strategies [17,61].

Overall, the chemical control (T1) maintained superior efficacy at key points of the crop cycle, largely due to the rotational use of active ingredients, and significantly outperformed most biological treatments. However, the findings of this study also support the potential of Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3) as a viable alternative to chemical control, particularly under field conditions characterized by water stress. These results reinforce the importance of developing integrated pest management (IPM) strategies that combine insecticide rotation with the application of fungal-based biological agents, optimizing application timing according to climatic conditions and pest phenology. Similarly, Lacey et al. [40] demonstrated that the integration of biological and chemical control can enhance suppression of B. cockerelli populations without increasing resistance selection pressure. Such integration can reduce dependence on broad-spectrum insecticides, mitigate the risk of resistance development, and sustain long-term control efficacy in potato production systems affected by this pest [17].

4.2. Symptomatology of Purple-Top Complex in Plants and Zebra Chip in Potato Tubers

The analysis of the probability of purple-top complex occurrence revealed significant differences among treatments, with the chemical control (T1) exhibiting the lowest value (0.46). Since values closer to zero indicate the absence of symptom expression, this result reflects a reduced likelihood of symptom development compared with the untreated control (T0) and Beauveria bassiana (T2). This suggests that the mode of action of T1—whether chemical or due to the synergistic combination of its active ingredients—was more effective in reducing the activity of the vector Bactericera cockerelli or in limiting the expression of purple-top complex symptoms. Previous studies have demonstrated that a reduction in infection probability can be associated with interference in the feeding behavior of B. cockerelli and a consequent decrease in the transmission rate of Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum between the host plant and the vector [11,62].

In turn, the application of the biological agent Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) resulted in a probability of symptom occurrence of 0.49, lower than T1, T2, and T3. Although the difference was statistically significant only when compared with the untreated control (T0), the reduction in purple-top symptomatology under this treatment was moderate, suggesting a trend toward a lower risk of symptom expression in plants. This effect could potentially be optimized through adjustments in application frequency or timing. The behavior observed in this study aligns with the findings of Mora et al. [62], who reported that water deficit conditions can alter host plant physiology and vector–pathogen interactions, thereby affecting the effectiveness of control strategies. Drought stress can modify plant physiological processes, alter vector feeding behavior, and influence disease progression—factors that likely contributed to the moderate symptom reduction observed in this treatment.

Regarding disease incidence, no significant differences were detected among treatments (p = 0.778). However, Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) exhibited the lowest incidence rate (56.60%) compared with the other treatments, which presented higher percentages and, consequently, a greater risk of zebra chip symptom expression in tubers. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it may hold agronomic relevance, as values approaching 100% indicate a high probability of visible damage and significant losses in commercial quality [36]. Additionally, Stoop et al. [63] noted that, under field conditions, environmental variability can often mask statistical effects, even when the agronomic impacts are evident to growers.

The joint interpretation of the probability of purple-top complex occurrence and the incidence rate of zebra chip (ZC) suggests that the chemical control (T1) is the most promising treatment for reducing the likelihood of purple-top symptom expression, whereas Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) may contribute to lowering the incidence of tuber symptoms. Similar results were reported by Greenway & Rondon [37], who emphasized that even in the absence of statistical significance, consistent reductions observed under field conditions can be highly relevant for integrated pest management (IPM) programs.

These findings are critical for field-level decision-making: low values of probability and incidence represent a reduced phytosanitary and economic risk, whereas high values indicate the need for immediate implementation of control measures. It is worth highlighting that Bactericera cockerelli (Šulc) is the primary vector responsible for transmitting Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum (CLso), the etiological agent associated with zebra chip disease, as documented in studies conducted in other regions of North America and Europe [14,32].

4.3. Influence on Yield and Commercial Quality of Tubers

The results showed that the chemical control (T1) achieved the highest yield, both in tuber weight and number per plant, significantly outperforming all other treatments. This behavior can be attributed to the greater efficacy of the product combining thiamethoxam and lambda-cyhalothrin, supported by the rotational use of insecticides containing abamectin and imidacloprid, as described in the methodology. These active ingredients exerted a direct effect on reducing Bactericera cockerelli pressure, thereby minimizing physiological damage and promoting tuber development. The products used are listed in Annex 2 of the Resolución Jefatural Nº D000141-2024-MIDAGRI-SENASA-JN, which recommends their strategic application for chemical control [29]. However, despite this relative advantage, the absolute values of tuber weight and number remained well below the expected yields for the UNICA variety under optimal conditions [34]. This suggests that the persistence of the pest still limited the productive potential of the crop. The low yields observed in this study may also be attributed to the limited water availability during critical stages such as tuber initiation, which directly affects both tuber size and number [64]. Under water deficit conditions, reductions in photosynthetic activity and alterations in the partitioning of photoassimilates toward storage organs result in fewer and smaller tubers [65], even when biotic stress—such as psyllid infestation—has been effectively controlled.

In contrast, the treatments with entomopathogenic fungi—Beauveria bassiana (T2), Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3), and Metarhizium anisopliae (T4)—showed relatively low and statistically similar yields among them. Although their performance was lower than that of the chemical control (T1), they still produced higher yields compared with the untreated control (T0), indicating that these agents exerted a certain degree of pest suppression and partially mitigated yield losses. The reduced productive response observed in the fungal treatments may be related to their strong dependence on environmental factors for conidial germination and sporulation [60], as well as the possible recolonization of the psyllid population during the crop’s phenological cycle [40]. The combined interaction of the vector and the bacterium constitutes a key factor contributing to yield reduction and deterioration of tuber quality, as evidenced by the visible brown streaking and necrotic patches observed in the harvested tubers.

To date, no commercial potato varieties have been identified that exhibit complete resistance to the psyllid Bactericera cockerelli or to zebra chip disease caused by Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum [33,36,45]. Although some genotypes have shown lower symptom incidence or reduced tuber damage, these responses are generally regarded as partial tolerance or avoidance rather than true resistance. Such mechanisms may be associated with specific plant traits, including trichome density, leaf architecture, the presence of secondary metabolites with deterrent or antibiotic properties, or phenological patterns that shorten the exposure period to the pest [11]. It is important to note that effective vector control alone does not guarantee the complete absence of purple-top complex symptoms, nor does it prevent the occurrence of zebra chip in potato tubers.

4.4. Limitations and Perspectives

Regarding the productive impact, it is necessary to evaluate complementary strategies, such as adjusting the timing of the first application of biological control strains and assessing their performance across different cropping seasons. Since this study represents one of the first field-based investigations on the purple-top complex in Peru, certain limitations were encountered in advancing the epidemiological understanding of zebra chip (ZC). The transfer of infected plant material to external laboratories for diagnostic purposes is currently restricted under national phytosanitary regulations [29]. Nevertheless, the weekly monitoring approach employed for the vector insect provided a reliable estimation of the population dynamics throughout the potato crop’s vegetative cycle. In addition, the morphological evaluation of purple-top complex symptoms and zebra chip presence in tubers proved to be a practical and applicable field strategy for estimating disease incidence. This approach, when complemented by molecular assays for the detection of Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum, would yield a more accurate estimation of zebra chip incidence in potato-producing areas currently affected by Bactericera cockerelli.

The viability of the conidia was not verified in this study; therefore, we recommend conducting this type of control through a germination test in the laboratory.

5. Conclusions

Based on the results obtained, the psyllid Bactericera cockerelli exhibited lower mortality under biological treatments compared with chemical control (T1), and water deficit conditions appeared to favor its persistence and damage potential. The symptom probability associated with the purple-top complex (46%) and the incidence of zebra chip disease (60.60%) were lowest under T1, followed by Metarhizium anisopliae (T4) with 56.60% incidence. Tuber yield and number were statistically higher in T1, indicating that chemical control was the most effective treatment, followed by T4 and Paecilomyces lilacinus (T3). Nevertheless, all treatments exhibited low yields and small tubers, reflecting the combined influence of pest pressure and environmental stress. Chemical vector control contributed to reducing the manifestation of purple-top and zebra chip symptoms. However, the results also highlight the potential of biological control agents as integral components of sustainable and integrated pest management (IPM) programs for potato production under field conditions affected by B. cockerelli.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijpb16040136/s1, Supplementary Materials: ESM_1 and ESM_2.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.-H.; methodology, G.C.-H. and F.L.-I.; data collection, G.C.-H.; data curation, S.C.-N. and F.L.-I.; data analysis and interpretation, G.C.-H., S.V.-N., H.M.-R. and S.C.-N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.-R., F.L.-I. and S.C.-N.; writing—review and editing, L.D.V.-A., F.L.-I. and M.R.-R.; visualization, G.C.-H. and F.L.-I.; software, S.C.-N. and F.L.-I.; resources, M.R.-R. and J.C.; project administration, M.R.-R. and J.C.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute of Agricultural Innovation (INIA) through investment project No. 2472190 “El Chira”.

Data Availability Statement

All original data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and its Supplementary Materials. Reproducible datasets and analytical scripts are available in Supplementary Materials ESM_2 and accessible via the GitHub repository at: https://github.com/Sebass96/prochira_papa. (accessed on 12 November 2025).

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the National Institute of Agricultural Innovation (INIA) for financial support through the project “El Chira” (No. 2472190) and to the institutional research service for their assistance during this study. We also thank Milagros Ninoska Munoz-Salas for her valuable assistance in translating the manuscript into English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- González-Orozco, C.E.; Reyes-Herrera, P.H.; Sosa, C.C.; Torres, R.T.; Manrique-Carpintero, N.C.; Lasso-Paredes, Z.; Cerón-Souza, I.; Yockteng, R. Wild Relatives of Potato (Solanum L. Sec. Petota) Poorly Sampled and Unprotected in Colombia. Crop Sci. 2024, 64, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Dutt, S.; Raigond, P.; Changan, S.S.; Lal, M.K.; Sharma, D.; Singh, B. Potato Probiotics for Human Health. In Potato: Nutrition and Food Security; Raigond, P., Singh, B., Dutt, S., Chakrabarti, S.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 271–287. ISBN 978-981-15-7662-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolao, R.; Gaiero, P.; Castro, C.M.; Heiden, G. Solanum malmeanum, a Promising Wild Relative for Potato Breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1046702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rondon, S.I.; Carrillo, C.C.; Cuesta, H.X.; Navarro, P.D.; Acuña, I. Latin America Potato Production. In Insect Pests of Potato; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 317–330. ISBN 978-0-12-821237-0. [Google Scholar]

- Spooner, D.M.; Ghislain, M.; Simon, R.; Jansky, S.H.; Gavrilenko, T. Systematics, Diversity, Genetics, and Evolution of Wild and Cultivated Potatoes. Bot. Rev. 2014, 80, 283–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, D.; Bates, R.; Brennan, M.; Gill, T. Peru Potato Potential: Biodiversity Conservation and Value Chain Development. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2018, 33, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, R.K.; Singh, V. A Mini Review on Origin, History and Taxonomic Status of the Potato. FarmManage 2022, 7, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Jia, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, P.; Bao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Feng, S.; Zhu, X.; et al. Genome Evolution and Diversity of Wild and Cultivated Potatoes. Nature 2022, 606, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; He, X.Z.; Zhou, P.; Wang, Q. Life History and Behavior of Tamarixia Triozae Parasitizing the Tomato-Potato Psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli. Biol. Control. 2023, 179, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebiola, M.; Mauck, K.E. Symbiont Infection and Psyllid Haplotype Influence Phenotypic Plasticity during Host Switching Events. Ecol. Entomol. 2024, 49, 719–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenninger, E.J.; Rashed, A. Biology, Ecology, and Management of the Potato Psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae), and Zebra Chip Disease in Potato. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2024, 69, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vereijssen, J.; Smith, G.R.; Weintraub, P.G. Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae) and Candidatus Liberibacter Solanacearum in Potatoes in New Zealand: Biology, Transmission, and Implications for Management. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2018, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumner-Kalkun, J.C.; Sjölund, M.J.; Arnsdorf, Y.M.; Carnegie, M.; Highet, F.; Ouvrard, D.; Greenslade, A.F.C.; Bell, J.R.; Sigvald, R.; Kenyon, D.M. A Diagnostic Real-Time PCR Assay for the Rapid Identification of the Tomato-Potato Psyllid, Bactericera cockerell (Šulc, 1909) and Development of a Psyllid Barcoding Database. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwandharathne, N.I.; Holwell, G.I.; Avila, G.A. Current and Future Potential Geographical Distribution of Bactericera cockerelli: An Invasive Pest of Increasing Global Importance. Austral Entomol. 2023, 62, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereijssen, J. Bactericera cockerelli (Tomato/Potato Psyllid). CABI Compendium. CABI Int. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamarra, H.; Correa, Y.; Huaman, E.; Kreuze, J. Reporte Sobre Colecta de Bactericera cockerelli En Huancabamba-Piura, Perú; International Potato Center: La Molina, Peru, 2022; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar, S.C.; Hatt, S.; Philips, A.; Akter, M.; Milroy, S.P.; Xu, W. Tomato Potato Psyllid Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae) in Australia: Incursion, Potential Impact and Opportunities for Biological Control. Insects 2023, 14, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastas, K.K. Bacterial Diseases of Potato and Their Control. In Potato Production Worldwide; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 179–197. ISBN 978-0-12-822925-5. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.; Wang, R.; Ren, Y.; McKirdy, S. Potential Distribution and the Risks of Bactericera cockerelli and Its Associated Plant Pathogen Candidatus Liberibacter Solanacearum for Global Potato Production. Insects 2020, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyaneza, J.E. Zebra Chip Disease, Candidatus Liberibacter, and Potato Psyllid: A Global Threat to the Potato Industry. Am. J. Potato Res. 2015, 92, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.; Basu, S.; Crowder, D.W. Drought Stress Affects Interactions between Potato Plants, Psyllid Vectors, and a Bacterial Pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2023, 99, fiac142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huot, O.B.; Tamborindeguy, C. Drought Stress Affects Solanum lycopersicum Susceptibility to Bactericera cockerelli Colonization. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2017, 165, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerna, E.; Ochoa, Y.; Aguirre, L.; Flores, M.; Landeros, J. Determination of Insecticide Resistance in Four Populations of Potato Psillid Bactericera cockerelli (Sulc.) (Hemiptera: Triozidae). Phyton 2013, 82, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, K.; Zhong, X.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yi, L.; Zhang, N. Enhanced Control Efficacy of Different Insecticides Mixed with Mineral Oil Against Asian Citrus Psyllid, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, Under Varying Climates. Insects 2025, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, O.M.; Michels, G.J.; Pierson, E.A.; Heinz, K.M. A Predictive Degree Day Model for the Development of Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae) Infesting Solanum tuberosum. Environ. Entomol. 2015, 44, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page-Weir, N.E.M.; Jamieson, L.E.; Chhagan, A.; Connolly, P.G.; Curtis, C. Efficacy of Insecticides against the Tomato/Potato Psyllid (Bactericera cockerelli). NZPP 2011, 64, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocampo-Hernández, J.A.; Tamayo-Mejía, F.; Tamez-Guerra, P.; Gao, Y.; Guzmán-Franco, A.W. Different Host Plant Species Modifies the Susceptibility of Bactericera cockerelli to the Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria Bassiana. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 984–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaborklu, S. Biocontrol Potential of Beauveria Bassiana and Metarhizium Anisopliae Isolates from Turkey against Hyphantria Cunea (Drury) (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae) Larvae under Laboratory and Field Conditions. Biosci. J. 2022, 38, e38015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servicio Nacional de Sanidad Agraria (SENASA). Resolución Jefatural N° D000141-2024-MIDAGRI-SENASA-JN; Ministerio de Desarrollo Agrario y Riego: Lima, Peru, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Burckhardt, D.; Lauterer, P. A Taxonomic Reassessment of the Triozid Genus Bactericera (Hemiptera: Psylloidea). J. Nat. Hist. 1997, 31, 99–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyer, J.R.; Crawford, R.F. Observations on the Feeding Habits of the Potato Psyllid (Paratrioza cockerelli Sulc.) and the Pathological History of the “Psyllid Yellows” Which It Produces. J. Econ. Entomol. 1933, 26, 846–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereijssen, J. Ecology and Management of Bactericera cockerelli and Candidatus Liberibacter Solanacearum in New Zealand. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronesi, E.R.; Thompson, C.J.; Goldson, S.L. Insect Biological Control of the Tomato-Potato Psyllid Bactericera cockerelli, a Review. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2023, 53, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Rosales, R.O.; Espinoza-Trelles, J.A.; Bonierbale, M. UNICA: Variedad Peruana Para Mercado Fresco y Papa Frita Con Tolerancia y Resistencia Para Condiciones Climáticas Adversas. Rev. Latinoam. Papa 2016, 14, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministerio de Agricultura y Riego (MINAGRI). Decreto Supremo N.° 010-2018-MINAGRI, Que Aprueba El Reglamento Específico de Semillas de Papa; Lima, Peru, 2018. Available online: https://www.gob.pe/institucion/midagri/normas-legales/190800-010-2018-minagri (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Butler, C.D.; Trumble, J.T. The Potato Psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli (Sulc) (Hemiptera: Triozidae): Life History, Relationship to Plant Diseases, and Management Strategies. Terr. Arthropod. Rev. 2012, 5, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenway, G.A.; Rondon, S. Economic Impacts of Zebra Chip in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington. Am. J. Potato Res. 2018, 95, 362–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.A.; Dunlap, C.A.; Jaronski, S.T. Ecological Considerations in Producing and Formulating Fungal Entomopathogens for Use in Insect Biocontrol. BioControl 2010, 55, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, G.M.; Jaronski, S.T. The Production and Uses of Beauveria Bassiana as a Microbial Insecticide. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, L.A.; Liu, T.-X.; Buchman, J.L.; Munyaneza, J.E.; Goolsby, J.A.; Horton, D.R. Entomopathogenic Fungi (Hypocreales) for Control of Potato Psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli (Šulc) (Hemiptera: Triozidae) in an Area Endemic for Zebra Chip Disease of Potato. Biol. Control. 2011, 56, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, G.D.; Goettel, M.S.; Butt, T.M.; Strasser, H. Use of Hyphomycetous Fungi for Managing Insect Pests. In Fungi as Biocontrol Agents: Progress, Problems and Potential; Butt, T.M., Jackson, C., Magan, N., Eds.; CABI Publishing: UK, 2001; pp. 23–69. ISBN 978-0-85199-356-0. [Google Scholar]

- International Potato Center. Informe de Visita a Huancabamba, Piura de Comitiva SENASA Nivel Central Intervención de Especialistas SENASA-CIP; International Potato Center: Lima, Peru, 2022; p. 13. ISBN 978-92-9060-652-9. [Google Scholar]

- Roque Enriquez, A.; Beltrán Beache, M.; Ochoa Fuentes, Y.M.; Delgado Ortiz, J.C. Parámetros Poblacionales de Bactericera cockerelli En Plantas de Tomate Tratadas Con Menadiona. Remexca 2024, 15, e3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.-B.; Zhang, Y.-M.; Hua, L.; Peng, L.-N.; Munyaneza, J.E.; Trumble, J.T.; Liu, T.-X. Repellency of Selected Biorational Insecticides to Potato Psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Psyllidae). Crop Prot. 2010, 29, 1320–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyaneza, J.E. Zebra Chip Disease of Potato: Biology, Epidemiology, and Management. Am. J. Pot. Res. 2012, 89, 329–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, P.J.; Surrey, M.R.; Wigley, P.J.; Anderson, J.A.D.; Hartnett, D.E.; Wallace, A.R. Seasonality of Bactericera cockerelli in Potatoes (Solanum Tuberosum) in South Auckland, New Zealand. New Zealand J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2009, 37, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, S.; Forbes, A.; Amoros, W.; Gastelo, M.; Salas, E.; Hualla, V.; De Mendiburu, F.; Bonierbale, M. Metodologías de Evaluación Estándar y Manejo de Datos de Clones Avanzados de Papa; Modulo 2: Evaluación del rendimiento de tubérculos sanos de clones avanzados de papa. Guía para Colaboradores Internacionales; Centro Internacional de la Papa: Lima, Perú, 2014; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Liefting, L.W.; Sutherland, P.W.; Ward, L.I.; Paice, K.L.; Weir, B.S.; Clover, G.R.G. A New ‘Candidatus Liberibacter’ Species Associated with Diseases of Solanaceous Crops. Plant Dis. 2009, 93, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderplank, J. Plant Diseases: Epidemics and Control; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S.; Christensen, R.H.B.; Singmann, H.; Dai, B.; Scheipl, F.; Grothendieck, G.; Green, P.; et al. lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using “Eigen” and S4. 2025. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4 (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Schielzeth, H.; Dingemanse, N.J.; Nakagawa, S.; Westneat, D.F.; Allegue, H.; Teplitsky, C.; Réale, D.; Dochtermann, N.A.; Garamszegi, L.Z.; Araya-Ajoy, Y.G. Robustness of Linear Mixed-Effects Models to Violations of Distributional Assumptions. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1141–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V.; Bolker, B.; Buerkner, P.; Giné-Vázquez, I.; Herve, M.; Jung, M.; Love, J.; Miguez, F.; Piaskowski, J.; Riebl, H.; et al. Emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, Aka Least-Squares Means; CRAN: Wien, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.-C. Towards understanding and use of mixed-model analysis of agricultural experiments. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2010, 90, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, E.; Hui, F.K.C. Symbolic Formulae for Linear Mixed Models. In Statistics and Data Science. RSSDS 2019. Communications in Computer and Information Science; Nguyen, H., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerna, E.; Ail, C.; Landeros, J.; Sánchez, S.; Badii, M.; Aguirre, L.; Ochoa, Y. Comparación de la toxicidad y selectividad de insecticidas para la plaga Bactericera cockerelli y su depredador Chrysoperla carnea. Agrociencia 2012, 46, 783–793. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Teja, K.N.P.; Rahman, S.J. Characterisation and Evaluation of Metarhizium Anisopliae (Metsch.) Sorokin Strains for Their Temperature Tolerance. Mycology 2016, 7, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, K.; Mendoza-Herrera, A.; Levy, J.G.; Tamborindeguy, C. Lasting Consequences of Psyllid (Bactericera cockerelli L.) Infestation on Tomato Defense, Gene Expression, and Growth. BMC Plant. Biol. 2021, 21, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, C.G.; Kavallieratos, N.G.; Rumbos, C.I.; Kontodimas, D.C. Influence of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Insecticidal Efficacy of Metarhizium Anisopliae against Larvae of Ephestia Kuehniella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) on Wheat. J. Insect. Sci. 2017, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco Hernández, M.L.; Reséndiz Martínez, J.F.; Arriola Padilla, V.J.; Pacheco Hernández, M.d.L.; Reséndiz Martínez, J.F.; Arriola Padilla, V.J. Organismos entomopatógenos como control biológico en los sectores agropecuario y forestal de México: Una revisión. Rev. Mex. Cienc. For. 2019, 10, 4–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaman, K.; Higgins, C.; O’Neill, M.; Begay, S.; Koudahe, K.; Allen, S. Population Dynamics of Six Major Insect Pests During Multiple Crop Growing Seasons in Northwestern New Mexico. Insects 2019, 10, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, V.; Ramasamy, M.; Damaj, M.B.; Irigoyen, S.; Ancona, V.; Avila, C.A.; Vales, M.I.; Ibanez, F.; Mandadi, K.K. Identification and Characterization of Potato Zebra Chip Resistance Among Wild Solanum Species. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 857493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoop, W.A.; Adam, A.; Kassam, A. Comparing Rice Production Systems: A Challenge for Agronomic Research and for the Dissemination of Knowledge-Intensive Farming Practices. Agric. Water Manag. 2009, 96, 1491–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, M.M.; Gumiere, S.J.; Gallichand, J.; Celicourt, P.; Gumiere, T. Impacts of Water Stress Severity and Duration on Potato Photosynthetic Activity and Yields. Front. Agron. 2020, 2, 590312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Deng, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Zhang, H. Potato Growth, Photosynthesis, Yield, and Quality Response to Regulated Deficit Drip Irrigation under Film Mulching in a Cold and Arid Environment. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).