Abstract

Water deficit and heat are the primary abiotic stresses affecting plants. We conducted in vitro experiments to investigate how citron watermelon seedlings respond to water deficit and heat, focusing on growth, water status, reserve mobilization, hydrolase activity, and metabolite partitioning, including non-structural carbohydrate availability, during the vulnerable stage of seedling establishment crucial for crop production. To reveal the involvement of phytosterols (stigmasterol, sitosterol, and campesterol) in combined stress tolerance, four citron watermelon genotypes were investigated under varying osmotic potential [−0.05 MPa, −0.09 MPa and −0.19 MPa] and temperature (26 °C and 38 °C). Phytosterols were analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Seedlings subjected to osmotic stress from polyethylene glycol (PEG) exhibited reduced growth, linked to relative water content (RWC) changes, delayed starch mobilization in cotyle-dons, and decreased non-structural carbohydrate availability in roots. High temperature retarded the photosynthetic apparatus’s establishment and compromised photosynthetic pigment activity and dry matter production. The results suggest that inherent stress tolerance in citron watermelon is characterized by the increased accumulation of lipids, mainly sterols, especially in heat/drought-stressed plants. This study provides valuable information about the metabolic response of citron watermelon to combined stress and metabolites identified, which will encourage further study in transcriptome and proteomics to improve drought tolerance.

1. Introduction

Essential features of citron watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides (L.H. Bailey) Mansf. Ex Greb.) contribute to its broad use in genetic studies [1]. Several key traits significantly influence genetic variability in citron watermelon. Its diploid nature, characterized by possessing two sets of chromosomes and a high degree of inbreeding, results in a stable, relatively uniform genetic structure within populations [2]. Citron watermelon’s low chromosome number simplifies genetic mapping and manipulation, facilitating research and breeding efforts [3]. The ease of cross-breeding allows for the introduction of desirable traits from different genotypes. At the same time, its adaptability to a wide range of climatic conditions promotes genetic diversity by enabling cultivation in diverse environments. Together, these factors create a rich foundation for exploring and enhancing genetic variability within the crop [1,3]. Due to its geographic adaptability and natural tolerance to drought, heat, or salinity, there is an increasing interest in identifying the stress-response mechanisms in citron watermelon.

Numerous studies have focused on its response to abiotic stresses, such as drought in citron watermelon [4,5], heat in cucurbits [6], and salinity in watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) [7,8,9]. Most of these reports [4,5,6,7,8,9] are centered on the influence of single stress; however, plants are usually exposed to multiple abiotic stresses under field conditions. For example, drought is often accompanied by high temperatures, and their combined effects significantly impact citron watermelon yield more than the effects of a single stress alone [10].

Abiotic stresses (drought, extreme temperatures, salinity and nutrient deficiencies) significantly impact crop growth and development [11,12]. These environmental factors disrupt physiological processes, leading to reduced photosynthesis, impaired nutrient uptake, and stunted growth. Drought stress, for example, causes wilting and decreased yield by limiting water availability, while extreme temperatures hinder flowering and fruit set [13,14]. Salinity affects soil structure and plant nutrient availability, further compromising crop health [15].

Reports have revealed that the reaction of plant(s) to combined stresses is unique and cannot be directly extrapolated from the response of the plant exposed to individual stress as reported in potato (Solanum tuberosum) and alpine plants (Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora) [16,17]. However, it is known that drought in wild watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) and muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.) [18,19], high temperature in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and melons [20,21], and salinity in fig leaf gourd (Cucurbita ficifolia) [22] induce oxidative damage, and thus similar molecular responses may also occur in plants.

The available data on the combined effects of abiotic stresses on citron watermelon are limited, especially regarding changes in lipids under multiple abiotic stresses [23]. Improved high resolution and sensitivity in mass spectrometry (MS) have facilitated identification and characterizing key compounds in biological processes, including metabolites, proteins, and lipids [24,25,26,27]. Due to technological advances, modern lipidomic approaches use optimized and tailored MS-based methods [28], which have been successfully applied to plant lipid research [29].

Lipids (a group of biomolecules) are present in all plant tissues; they exert multiple roles and functions: constituents of the cell membrane [30], storage molecules of metabolic energy [31] and signaling factors in response to stressors [32]. Considering the different lipid classes, sterols are of great importance as they exert a structural function in cell membranes, contributing to the modulation of their fluidity. Sterols exist freely or as esterified molecules with fatty acids or carbohydrates. Phytosterols mainly comprise campesterol, β-sitosterol, and stigmasterol [33,34].

Apart from their structural function, phytosterols also play a regulatory role in plants. The relative phytosterol composition is altered by stress, changing the characteristics of the cell membrane and its biological functions [35]. Moreover, it is assumed that plant adaptation to stress may be determined by the ability of phytosterols to resist oxidation by reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are generated under various stress conditions. ROS react with unsaturated molecules, changing their structure and cellular functions [36].

Stigmasterol modulates plant membrane fluidity and is a precursor for synthesizing important phytohormones (brassinosteroids) essential for growth and development [37]. Dufourc [38] reported that campesterol plays a vital role in cell membrane structure and function—its conversion to brassinosteroids further underscores its regulatory importance. β-Sitosterol, the most prevalent plant sterol, contributes to membrane stability and participates in signaling pathways, regulating plant responses to environmental stress [39]. Together, these sterols maintain membrane integrity and influence critical developmental and stress-response pathways in plants.

We hypothesized that phytosterol changes in citron watermelon seedling axis are differentially expressed under combined stress compared to a single stress. Second, we postulated that genetics and environmental factors interact to influence phytosterol changes, and this study demonstrated the significance of both factors. Therefore, this study aimed to identify the multiple abiotic-stress-induced modifications in different phytosterols (campesterol, sitosterol, and stigmasterol) in seedling axis (embryonic leaf and root) of genetically distinct citron watermelon accessions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

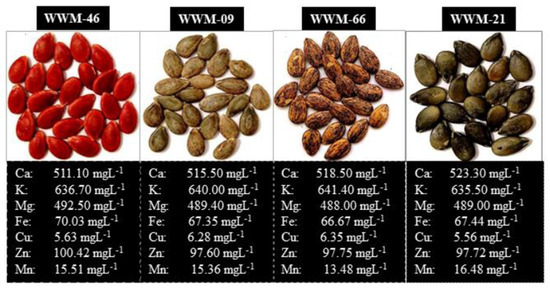

The Limpopo Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, South Africa, provided 40 citron watermelon landrace accessions. Four genotypes were selected from previous work based on the high-stress tolerance index [5]. The mineral element composition of selected genotypes is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Citron watermelon genotypes used for the study and their estimated mineral element composition from fast atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS).

2.2. In Vitro Culture

2.2.1. Water Agar Preparation

Following the method described by [40] with minor modifications, 20 g of agar powder for tissue culture [CAS No. 9002-18-0] purchased from Sisco Research Laboratories, Mumbai, India, was measured using an analytical balance (Shimadzu AP124W), Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan and suspended in 1000 mL double-distilled water. The agar was boiled to dissolve it completely. Completely dissolved water agar was sterilized by autoclaving at 15 Pa (121 °C) for 15 min in a Biobase autoclave (Model: BKQ-B50II), Biobase Biodustry (Shandong) Co., Ltd., Jinan, China.

2.2.2. Design of Simulated Water Stress Conditions

Following the method described by [41], 0, 5, and 10% polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions with osmotic potentials of 0.00, −0.09 and −0.19 MPa, respectively, were prepared. The solutions’ osmotic potential (OP) in Table 1 was measured using a CX-2 water potential meter (Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, Washington, DC, USA).

Table 1.

Osmotic potential of polyethylene glycol (PEG-6000) solutions.

2.3. Water and Heat Stress Treatments

The experiment was a 4 (genotypes) × 3 (osmotic potential) × 2 (temperature regimes) factorial design replicated three times to give 72 experimental units. Day-old seedlings were transferred to 100 mL transparent cups containing 5 gL−1 water agar for water stress treatment. Drought stress was induced by injecting a syringe of 15 mL of PEG solution of different OPs (0.00, −0.09 and −0.19 MPa) into the water agar. Lower OPs were avoided as they cease seedling development. The top of the agar was covered with cotton wool to reduce agar contamination. Transparent cups were covered with aluminum foil paper to block light from influencing root growth. The cups were placed in a growth chamber (Micro-Clima Arabidopsis Chamber, ECP01E, Snijders, The Netherlands) for 5 days. Growth chamber conditions were set at 25 ± 1 °C, 70% relative humidity, illumination of 4000 lux for 12 h and 350 ppm CO2. Set values were controlled by the control unit (JUMO IMAGO 500), JUMO GmbH & Co. KG, Fulda, Germany. Day-old seedlings were transplanted to 5 g L−1 water agar in 100 mL transparent cups for heat stress treatment and maintained in an incubator at 26 °C (control) and 38 °C (heat stress) for 5 days.

2.4. Seedling Growth

The average daily growth rate (ADGR) for the seedling under different treatments was measured according to Equation (1), where H1 and H2 are plant height at times T1 and T2 [42].

Five days after taking daily growth measurements, seedlings were uprooted, washed, and sectioned into cotyledon, hypocotyl, and roots. Fresh mass was measured soon after uprooting, and dry mass was measured after samples were oven-dried for 48 h at 75 °C.

2.5. Relative Water Content (RWC)

Samples of the different seedling parts whose fresh weight (FW) was previously measured were immersed in distilled H2O and maintained at 25 °C for 60 min. The samples were blotted on paper towels to remove excess water and weighed to quantify the turgid weight (TW) using an analytical balance (Shimadzu AP124W), Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan. Finally, the samples were oven-dried at 75 °C for 48 h to obtain the DW. Equation (2) was used to calculate the relative water content (RWC) [43].

2.6. Biochemical Analysis Samples

Samples reserved for the biochemical analysis were frozen at −70 °C in a freezer (HERAfreeze TDE TDE50086FV), Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA, for 24 h and lyophilized in a freeze drier (Larry Virtis 255L), SP Scientific, PA, USA at −126.5 °C for 96 h. Dried embryonic leaves, hypocotyl, and roots were separately ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle and stored in a chest freezer at −5 °C.

2.7. Estimation of Photosynthesis Pigments

Total chlorophyll content, chlorophyll ‘a’, chlorophyll ‘b’, and carotenoids were extracted and quantified using the method described by [44]. Total chlorophylls and carotenoids were extracted from 50 mg of fresh leaf tissue by maceration with 10 mL of 80% (v/v) acetone (C3H6O) under reduced luminosity. Samples were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 20 min using a GenFuge 24D (Mexborough, UK). The supernatants were collected, and readings were taken at 450, 645, and 663 nm using Shimadzu UV-1800 UV/Visible Scanning Spectrophotometer, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan. Following the extraction and analysis, the relative amounts of chlorophyll ‘a’, chlorophyll ‘b’, and total chlorophyll content were estimated using Equations (3)–(5).

A: Absorbance at specific wavelengths; V: final volume of chlorophyll extract in 80% acetone; W: fresh weight of tissue extracted; Constants: 12.7, 2.69, 22.9, 4.68, 20.2, and 8.02.

2.8. Non-Structural Carbohydrates (NSC)

Soluble metabolites were extracted from 200 mg of frozen FW, which were fragmented and transferred to tubes containing 1.5 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol. The tubes were sealed with parafilm tape and incubated at 60 °C for 30 min. Supernatants were harvested, and the residues were extracted again to yield 3 mL of ethanolic extract per sample. Total soluble sugars (TSS) were quantified with the anthrone reagent, using D-glucose as standard [45]. Non-reducing sugars (NRS) were measured by modifying the anthrone method, employing a sucrose standard curve [46]. The content of both metabolites (TSS and NRS) was calculated as µmol g−1 DW.

Starch was extracted from pellets obtained after the extraction of soluble metabolites. The pellets were macerated with 0.5 mL of 30% (v/v) perchloric acid (HClO4) and the homogenates were centrifuged at 6000 rpm for 20 min. The supernatants were collected, and the pellets were re-extracted twice, yielding 1.5 mL of extract per sample. These procedures were performed at ≈4 °C. Starch was also determined using a D-glucose standard curve with the anthrone method [47]. The starch content was calculated according to [48] and expressed as mg part−1.

2.9. Oxidative Stress Marker (Malondialdehyde)

Following the method described by [49], malondialdehyde (MDA) was measured in 80% (v/v) methanol extracts of 100 mg dry plant material. Extracts were mixed with 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (C4H4N2O2S) prepared in 20% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) (or with 20% TCA without TBA for the controls) and then incubated at 95 °C for 20 min. After stopping the reaction, the supernatant absorbance was measured at 532 nm. The non-specific absorbance at 600 and 440 nm was subtracted, and MDA concentration was calculated using the equations described by McElroy and Kopsell [50].

2.10. Phytosterols Analysis with Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

Phytosterols (campesterol, stigmasterol, and sitosterol) were estimated using the method described by [51]. Two grams of freeze-dried samples (cotyledons, hypocotyl and roots) were dissolved in 10 mL n-Hexane (chromatographic reagent grade, purchased from Chem Lab Supplies (Benrose, Johannesburg, South Africa) for 30 min. The mixture was filtered through Whatman No. 5 filter paper, and the sample filtrate aliquots were stored in scintillation vials. Analysis was carried out using a GCMS-QP2010 SE (Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with a ZB-5MSplus column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d. × 0.25 µm film thickness) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and deactivated tubing guard column (Zebron 5 m × 0.25 mm).

For each sample, 1.0 μL was injected at 310 °C in the split mode (split ratio 20:1). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate (1.8 mL min−1). The GC temperature program was initiated at 200 °C, held for 30 s, increased to 310 °C at 30 °C min−1, and held for 10 min. An electron ionization (EI) source was applied, and electron energy was 70 eV. The source and interface temperatures were set at 230 °C and 310 °C, respectively. The mass analyzer was set in the selected ion monitoring mode for qualitative and quantitative analyses. For qualitative analyses, the values of the ions selected were m/z 382, 147, and 81 to identify campesterol, m/z 394, 255, 81 for stigmasterol, and m/z 396, 213, and 43 for sitosterol.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

A combined two-way analysis of variance was performed for measured parameters using Genstat 23rd edition (VSN International, Hempstead, UK). Means were separated using Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) test when treatments showed significant effects on measured parameters at 5% significance level. Principal component analysis (PCA) and the biplot diagrams were exploited to identify the principal axes of variance within a dataset using XLSTAT software, v2023.5 (Data Analysis and Statistical Solution for Microsoft Excel, Addinsoft, v2023.5, Paris, France, 2022).

3. Results

3.1. Seedling Growth

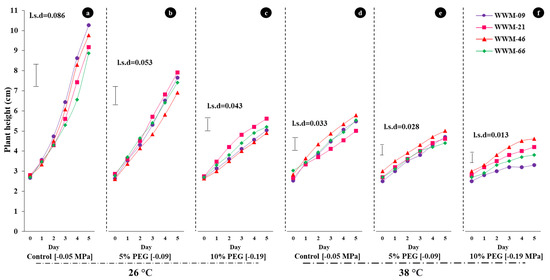

After five days of treatment exposure, a decrease in plant height was intricately linked with decreasing osmotic potential and increasing temperature (Figure 2). The highest plant height (10.267 cm) was observed in WWM-09 at [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C] after five days of treatment exposure (Figure 2a). After five days of treatment exposure, the lowest plant height (3.300 cm) was recorded in WWM-09 at [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C] (Figure 2f).

Figure 2.

Effect of heat and water stress on hypocotyl growth of four citron watermelon landrace accession over five days after exposure to combined stress (water and heat) treatment; (a) [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], (b) [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], (c) [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], (d) [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], (e) [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], and (f) [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C].

At [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], plant height after five days ranged from 8.867 in WWM-66 to 10.267 cm in WWM-09 (Figure 2a). At [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], plant height ranged from 6.900 cm in WWM-46 to 7.900 cm in WWM-21 (Figure 2b). The highest (5.600 cm) and lowest (4.900 cm) plant heights were observed in WWM-21 and WWM-46, respectively, at [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C] (Figure 2c).

Landrace accessions WWM-21 and WWM-46 recorded the lowest (5.000 cm) and highest (5.767 cm) plant height at [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C] (Figure 2d). At [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], plant height ranged from 4.400 cm (WWM-66) to 5.000 cm (WWM-46) (Figure 2e). At [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C], plant height ranged from 3.300 cm in WWM-09 to 4.600 cm in WWM-46 (Figure 2f).

There were significant differences (p < 0.001) in average daily growth rate (ADGR) of citron watermelon seedlings under varying osmotic potential and temperature. The ADGR values at [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C] ranged from 1.175 cm day−1 in WWM-66 to 1.569 cm day−1 in WWM-09. The treatment combination [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C] reduced the ADGR to a range of 0.843 to 1.028 cm day−1. At [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], the highest average daily growth rate (0.575 cm day−1) was recorded in WWM-21 and the lowest (0.475 cm day−1) was recorded in WWM-09 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Mathematical representation (y = mx + c) of average daily growth rate (cm day−1) of citron watermelon accessions under heat and water stress.

Landrace accessions WWM-46 and WWM-21 recorded the highest (0.580 cm day−1) and lowest (0.448 cm day−1) ADGR under [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C]. At [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], WWM-09 recorded the highest ADGR and WWM-66 recorded the least ADGR of 0.434 cm day−1 and 0.349 cm day−1, respectively. At [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C], WWM-46 had highest ADGR (0.343 cm day−1), followed by WWM-21 (0.277 cm day−1), WWM-66 (0.231 cm day−1), and WWM-09 (0.154 cm day−1) (Table 2).

3.2. Seedling Axis

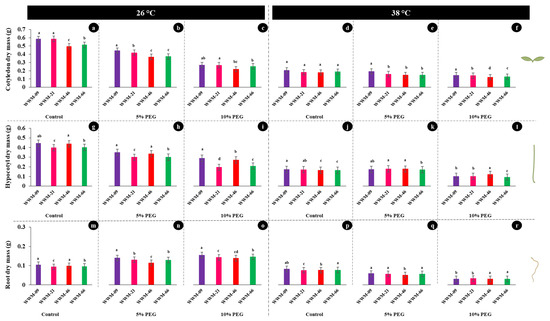

Cotyledon dry mass (CDM), hypocotyl dry mass (HDM), and root dry mass (RDM) were significantly different (p < 0.05) with significant interactions among landraces at both temperature regimes (26 °C and 38 °C) and varying osmotic potentials (−0.05, −0.09, and −0.19 MPa) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Dry mass of citron watermelon seedling axis (cotyledon, hypocotyl, and roots) at day five after exposure to osmotic stress and heat stress. (a) [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], (b) [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], (c) [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], (d) [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], (e) [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], and (f) [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C], (g) [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], (h) [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], (i) [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], (j) [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], (k) [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], and (l) [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C]. (m) [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], (n) [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], (o) [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], (p) [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], (q) [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], and (r) [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C]. Means with the same letters are statistically similar, while those with different letters are significantly distinct.

The cotyledon dry mass at [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C] ranged from 0.584 g in WWM-09 to 0.496 g in WWM-46 (Figure 3a). Accessions WWM-09 and WWM-66 recorded the highest (0.444 g) and lowest (0.372 g) CDM under [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], respectively (Figure 3b). At [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], the highest CDM (0.267 g) was recorded in WWM-09 and WWM-21, while the least CDM (0.219 g) was recorded in WWM-46 (Figure 3c). WWM-09 had the highest CDM of 0.205 g, while WWM-46 recorded the lowest CDM (0.179 g) at [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C] (Figure 3d). In Figure 3e ([−0.09 MPa; 38 °C]), WWM-09 recorded the highest CDM (0.192 g) and WWM-66 had the lowest CDM (0.148 g). The highest (0.147 g) and the lowest (0.122 g) CDM at [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C] were recorded in WWM-09 and WWM-66, respectively (Figure 3f).

Hypocotyl dry mass (HDM) at [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C] ranged from 0.398 g in WWM-21 to 0.445 g in WWM-09 (Figure 3g). Accessions WWM-09 and WWM-21 recorded the highest (0.349 g) and lowest (0.299 g) HDM at [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], respectively (Figure 3h). At [−0.19 MPa; 26°C], the highest HDM (0.289 g) was recorded in WWM-09 and the lowest HDM (0.195 g) was recorded in WWM-21 (Figure 3i). WWM-09 had the highest HDM of 0.175 g, while WWM-46 recorded the lowest HDM (0.165 g) at [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C] (Figure 3j). The highest (0.180 g) and the lowest (0.171 g) HDM at [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C] were recorded in WWM-21 and WWM-66, respectively (Figure 3k). Accessions WWM-46 and WWM-09 recorded higher HDM values (0.122 and 0.103 g) than WWM-21 (0.102 g) and WWM-66 (0.094 g) at [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C] (Figure 3l).

At 26 °C, increased root dry mass (RDM) among landraces was linked with lowering the osmotic potential of the water agar (Figure 3m,n). At [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], the highest RDM (0.104 g) was recorded in WWM-09 and the lowest RDM (0.094 g) was recorded in WWM-21 (Figure 3m). Accessions WWM-09 and WWM-21 recorded higher RDM values (0.140 and 0.130 g) than WWM-66 and WWM-46 (0.129 and 0.114 g) at [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C] (Figure 3n). At [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], highest RDM (0.155 g) was recorded in WWM-09 and WWM-21, while the lowest RDM (0.139 g) was recorded in WWM-46 (Figure 3o). At 38 °C, RDM decreased with increasing negativity of the osmotic potential across landrace accessions evaluated (Figure 3p–r). At [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], RDM ranged from 0.076–0.082 g (Figure 3p). Figure 3q shows the RDM range of 0.051–0.059 g at [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C]. At higher temperatures (38 °C) and lowest osmotic potential (−0.19 MPa), RDM ranged from 0.031 to 0.033 g (Figure 3r).

3.3. Relative Water Content (RWC)

The analysis of variance showed significant differences in RWC for single factors (genotype, osmotic potential, and temperature) (p < 0.001). Significant treatment interactions were observed for treatment combinations: genotype × temperature and osmotic potential × temperature (p < 0.05) (Table 3). At [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], the highest RWC (90.03%) was recorded in WWM-09 and the lowest RWC (81.19%) was recorded in WWM-46. The highest and lowest RWC were recorded in WWM-09 (82.98%) and WWM-66 (70.89%), respectively, at [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C]. Accessions WWM-09 (72.72%) and WWM-21 (65.18%) had highest and lowest RWC at [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], respectively. A continuous decrease in RWC of the embryonic leaf was observed with increasing temperature and osmotic potential negativity. At [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], RWC ranged from 73.04% in WWM-66 to 84.05% in WWM-09. Accessions WWM-09 (75.36%) and WWM-66 (65.00%) had highest and lowest RWC at [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], respectively. At [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C], RWC was highest in WWM-09 (67.21%) and lowest in WWM-66 (52.93%) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Analysis of variance with mean squares and significant tests of relative water content and photosynthetic pigments of four citron watermelon genotypes under varying temperatures and osmotic potential after five days of treatment exposure.

Table 4.

Means for percentage relative water content of citron watermelon embryonic leaf under varying temperatures and osmotic potential.

3.4. Photosynthetic Pigments

There were significant differences and significant treatment interactions in Chl a, Chl b, Chl a+b, Chl a/b, and carotenoids among citron watermelon genotypes (p < 0.05) (Table 3). At [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], Chl a ranged from 3.299 to 4.159 mg g−1, Chl b ranged from 1.238 to 1.298 mg g−1, Chl a+b ranged from 4.565 to 5.444 mg g−1, Chl a/b ranged from 2.632 to 3.237, and carotenoids ranged from 0.938 to 0.955 mg g−1. The highest values of Chl a (3.508 mg g−1), Chl b (1.120 mg g−1), Chl a+b (4.628 mg g−1), Chl a/b (3.158), and carotenoids (0.908 mg g−1) were recorded in WWM-09, while the lowest values of Chl a (2.800 mg g−1), Chl b (0.912 mg g−1), Chl a+b (3.738 mg g−1), Chl a/b (2.775), and carotenoids (0.851 mg g−1) were recorded in WWM-46, WWM-66, WWM-66, WWM-46, and WWM-46 at [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], respectively. At [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], highest Chl a (2.875 mg g−1), Chl b (0.839 mg g−1), Chl a+b (3.702 mg g−1), Chl a/b (3.480), and carotenoids (0.637 mg g−1) were recorded in WWM-09, WWM-66, WWM-09, WWM-09, and WWM-09, respectively—lowest Chl a (2.114 mg g−1), Chl b (0.769 mg g−1), Chl a+b (2.897 mg g−1), Chl a/b (2.861), and carotenoids (0.499 mg g−1) were recorded in WW-46, WW-21, WW-46, WW-66, and WW-66 (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean values for photosynthetic pigments (chlorophyll and carotenoids) under varying temperatures and osmotic potential.

At [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], highest Chl a (2.427 mg g−1), Chl b (0.840 mg g−1), Chl a+b (3.267 mg g−1), Chl a/b (3.325), and carotenoids (0.755 mg g−1) were recorded in WWM-21, WWM-21, WWM-21, WWM-09 and WWM-46, respectively—lowest Chl a (2.200 mg g−1), Chl b (0.717 mg g−1), Chl a+b (2.921 mg g−1), Chl a/b (3.079), and carotenoids (0.718 mg g−1) were recorded in WW-66, WW-46, WW-46, WW-46, and WW-66. At [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], highest Chl a (1.869 mg g−1), Chl b (0.614 mg g−1), Chl a+b (2.483 mg g−1), Chl a/b (3.078), and carotenoids (0.594 mg g−1) were recorded in WWM-21, WWM-21, WWM-21, WWM-09, and WWM-09, respectively—lowest Chl a (1.773 mg g−1), Chl b (0.541 mg g−1), Chl a+b (2.133 mg g−1), Chl a/b (2.944), and carotenoids (0.460 mg g−1) were recorded in WW-09, WW-46, WW-46, WW-46, and WW-66. At [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C], highest Chl a (1.344 mg g−1), Chl b (0.452 mg g−1), Chl a+b (1.797 mg g−1), Chl a/b (3.037), and carotenoids (0.529 mg g−1) were recorded in WWM-21, WWM-21, WWM-21, WWM-66, and WWM-09, respectively—lowest Chl a (1.022 mg g−1), Chl b (0.351 mg g−1), Chl a+b (1.373 mg g−1), Chl a/b (3.000), and carotenoids (0.316 mg g−1) were recorded in WW-46, WW-46, WW-46, WW-09, and WW-66 (Table 5).

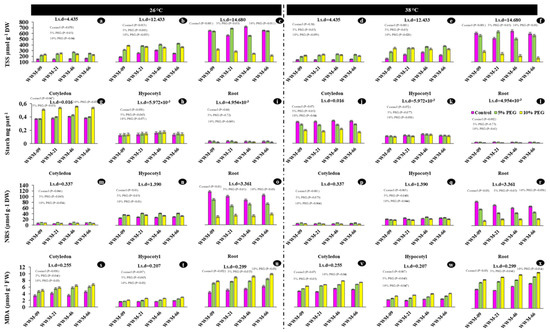

3.5. Non-Structural Carbohydrates

The TSS quantified in cotyledon, hypocotyl, and roots increased with increasing PEG concentration at 26 °C and 38 °C (Figure 4a–f). The highest TSS was recorded in WWM-46 (718.000 µmol g−1 DW) at [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C] in the root (Figure 4c), while the lowest TSS (135.490 µmol g−1 DW) were recorded in the cotyledons of WWM-09 at [−0.05; 38 °C] (Figure 4d).

Figure 4.

Total soluble solutes (a–f), starch (g–l), non-reducing sugars (m–r), and malondialdehyde (s–x) of citron watermelon seedling axis (cotyledon, hypocotyl and roots) at day five after exposure to osmotic and heat stress.

Starch content accumulated in the embryonic leaf, hypocotyl and roots of evaluated citron watermelon accessions significantly differ (p < 0.05) under varying osmotic potentials and temperature (Table 6). Highest (≥0.589 mg part−1) starch content was accumulated in the embryonic leaf in WWM-46 and WWM-66 at [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C] (Figure 4g). The starch in cotyledons, hypocotyl, and roots all decreased with increasing PEG concentration and temperature, with the greatest reductions occurring under the highest water stress (−0.19 MPa) (Figure 4g–l).

Table 6.

Analysis of variance with mean squares and significant tests of non-structural carbohydrates of four citron watermelon genotypes under varying temperatures and osmotic potential after five days of treatment exposure.

The non-reducing sugars (NRS) accumulated in the cotyledon, hypocotyl and roots of evaluated citron watermelon accession significantly differ (p < 0.05) under varying osmotic potentials and temperature (Table 6). The highest NRS (≥84.093 µmol g−1 DW) was recorded under [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C] in the roots, while the lowest NRS (4.387 µmol g−1 DW) was recorded at [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C] in the cotyledons.

The ANOVA revealed genotype, temperature, osmotic potential, and seedling axis, and their interactions were statistically significant for MDA. The highest MDA levels (11.65 μmol g−1 FW) were recorded in roots at [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C] in WWM-66. The lowest MDA (≤2.04 μmol g−1 FW) was recorded in WWM-09 and WWM21 in the hypocotyl at [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C] (Figure 4).

3.6. Phytosterols

The ANOVA revealed genotype, temperature, osmotic potential, and seedling axis, and their interactions were statistically significant for stigmasterol, sitosterol, campesterol, and total phytosterol, as shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Analysis of variance showing mean squares and significant tests for phytosterols (stigmasterol, sitosterol, and campesterol) of 4 citron watermelon landrace accessions evaluated under combined stress (heat and osmotic stress).

At 26 °C, the highest stigmasterol was recorded in the roots of WWM-09 (0.535 mg g−1 DW) at −0.19 MPa. The lowest stigmasterol (≤0.095 mg g−1 DW) was recorded in the embryonic leaves of WWM-21 and WWM-46 at −0.05 MPa. The highest sitosterol (≥0.258 mg g−1 DW) was recorded in the roots of WWM-09 and WWM-21 at −0.19 MPa. The lowest sitosterol concentration was recorded in the roots of WWM-09 (0.109 mg g−1 DW) at −0.05 MPa. The highest campesterol (≥0.563 mg g−1 DW) was recorded in roots of WWM-09 and WWM-46 at −0.19 MPa (Table 8).

Table 8.

Mean values for stigmasterol, sitosterol, and campesterol in citron watermelon seedling axis (cotyledon and roots) under different temperatures and osmotic potential.

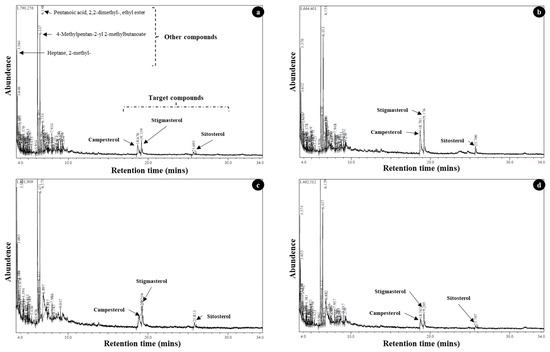

At 38 °C, the highest stigmasterol was recorded in the roots of WWM-09 (1.003 mg g−1 DW) at −0.19 MPa. The lowest stigmasterol (0.225 mg g−1 DW) was recorded in the cotyledon of WWM-21 at −0.05 MPa. The highest sitosterol (0.886 mg g−1 DW) was recorded in the roots of WWM-09 at −0.19 MPa. The lowest sitosterol concentration was recorded in the cotyledon of WWM-21 and WWM-46 (≤0.339 mg g−1 DW) at −0.05 MPa. The highest campesterol (≥0.899 mg g−1 DW) was recorded in the roots of WWM-21 and WWM-46 at −0.19 MPa, while the lowest campesterol (0.216 mg g−1 DW) was recorded in the cotyledon of WWM-66 at −0.05 MPa (Table 8). The peak area (abundance) of target compound (campesterol, stigmasterol, and sitosterol) in the sample was used to calculate quantify concentrations of phytosterols (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The electron impact ionization mass spectra of phytosterols (campesterol, stigmasterol, and sitosterol) in samples of (a) cotyledon [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], (b) roots [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], (c) cotyledon [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C], and (d) roots [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C].

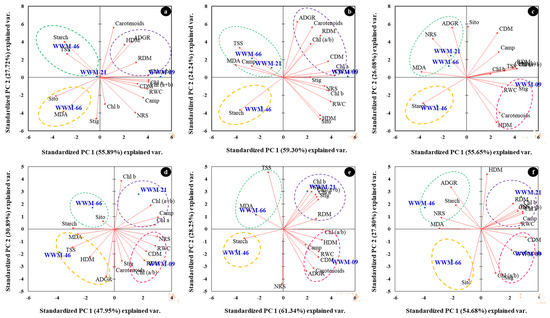

3.7. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for Assessed Traits

Table 9 shows the PCA with factor loadings, eigenvalues, and percent variance for the evaluated traits. Under [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], PC1 accounted for 55.89% of the total variation and was positively correlated with CDM, RDM, RWC, Chl a, NRS, and campesterol. Principal component 2 was positively correlated with ADGR, HDM, starch, and carotenoids, contributing to 27.72% of the total variation. PC3 accounted for 16.39% of the total variation and was positively correlated with HDM, RDM, and stigmasterol.

Table 9.

Summary of factor loadings, eigenvalue, percent, and cumulative variation for dry matter, pigments, non-structural carbohydrates, malondialdehyde, and phytosterols among 4 citron watermelon accessions under varying temperatures and osmotic potential.

At [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], PC1 accounted for 59.30% of the total variation and was positively correlated with RWC, Chl a, Chl b, Chl (a+b), and sitosterol. PC 2 was positively correlated with ADGR, RDM, and carotenoids, contributing to 24.24% of the total variation. Stigmasterol and campesterol were positively correlated with PC3, accounting for 16.47% of the total variation (Table 9).

Under [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], RDM, Chl a, Chl (a+b), Chl a/b, and stigmasterol were positively correlated with PC1, accounting for 55.65% of the total variation. PC 2 was positively correlated with CDM and sitosterol, contributing to 26.08% of the total variation. Relative water content and Chl b were positively correlated with PC3, accounting for 18.27% of the total variation (Table 9).

At [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], PC1 accounted for 47.96% of the total variation and was positively correlated with RWC, Chl a, Chl (a+b), NRS, and campesterol. PC 2 was positively correlated with Chl b, contributing to 30.89% of the total variation. Stigmasterol and sitosterol were positively correlated with PC3, accounting for 21.15% of the total variation (Table 9).

At [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], PC1 accounted for 61.34% of the total variation and was positively correlated with CDM, HDM, RWC, Chl (a/b), stigmasterol and sitosterol. PC 2 was positively correlated with Chl b and TSS, contributing to 28.25% of the total variation. Campesterol and RDM were positively correlated with PC3, accounting for 10.41% of the total variation (Table 9).

At [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C], PC1 accounted for 54.68% of the total variation and was positively correlated with CDM, Chl a, Chl (a+b), TSS and campesterol. PC 2 was positively correlated with HDM and ADGR, contributing to 27.81% of the total variation. Carotenoids and starch were positively correlated with PC3, accounting for 17.52% of the total variation (Table 9).

The PC biplots based on PCA analysis were used to picture the relationship among citron watermelon landraces based on evaluated parameters under varying temperatures and osmotic stress (Figure 6a–f). Traits represented by parallel vectors or close to each other revealed a strong positive association, and those located nearly opposite (at 180°) showed a highly negative association. In contrast, the vectors toward sides expressed a weak relationship.

Figure 6.

Principal component (PC) biplot of PC 1 vs. PC 2 demonstrating the relationships among dry matter, pigments, non-structural carbohydrates, malondialdehyde and phytosterols of 4 citron watermelon accessions evaluated under (a) [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], (b) [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C], (c) [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], (d) [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], (e) [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], and (f) [−0.19 MPa; 38 °C].

At [−0.05 MPa; 26 °C], accessions WWM-21 and WWM-46 are grouped based on high starch and TSS. Accession WWM-09 is grouped based on high HDM and RDM. WWM-66 is grouped based on high sitosterol and MDA (Figure 6a). At [−0.09 MPa; 26 °C]. WWM-66 and WWM-21 are grouped based on high campesterol, MDA, and TSS (Figure 6b). In Figure 6c [−0.19 MPa; 26 °C], WWM-21 and WWM-66 are grouped based on high MDA, NRS, and ADGR.

At [−0.05 MPa; 38 °C], WWM-66 was grouped based on high starch and sitosterol; WWM-21 is associated with high Chl (a+b), campesterol and Chla. Accession WWM-46 and WWM-09 are associated with high (MDA, TSS, and HDM) and (stigmasterol, Chl (a/b), NRS, and RWC), respectively (Figure 6d). At [−0.09 MPa; 38 °C], WWM-66 is associated with MDA and TSS, and WWM-21 is associated with stigmasterol, RDM, and Chl b. WWM-09 is associated with carotenoids, campesterol, and RWC (Figure 6e). In Figure 6f, accession WWM-46 is associated with high starch, NRS, and MDA. WWM-21 is associated with high RDM, campesterol, RWC, and Chla. WWM-09 is associated with high stigmasterol, CDM and Chl (a/b).

4. Discussion

Water and heat stress act synergically under field conditions, making it challenging to define their contribution to drought stress in plants [52,53,54]. Therefore, this experiment was conducted in a growth chamber at a controlled temperature and varied osmotic potential to identify multiple abiotic-stress-induced modifications in different phytosterols in the seedling axis (embryonic leaf and root) of genetically distinct citron watermelon accessions. Combined stress affects biomass partitioning and growth more than the individual stresses of heat and drought [55]. Our results showed that low osmotic potential (−0.19 MPa) and high temperature (38 °C) retarded seedling growth rate and dry matter accumulation in citron watermelon seedling axis (Figure 2; Table 2). The primary effect of drought stress is a decline in relative water content, and it is accompanied by changes in molecular, physiological, morphological, and biochemical events.

The genotypic response regarding dry matter allocation under all stress conditions varied significantly among citron watermelon accessions (Figure 3). Organ-specific translocation and allocation of dry matter is an important attribute for drought tolerance rather than total biomass production [12,56]. Citron watermelon partitioned more carbon to roots than shoots under lowest osmotic potential (−0.19 MPa) (Figure 3), which could be attributed to the drought and heat-stress-tolerance ability of WWM-09 and WWM-46. Increased root biomass under drought will increase water and nutrient acquisition, an important mechanism of drought tolerance in citron watermelon [56].

Combined stress (drought and heat) severely impaired the photosynthetic system. Carotenoids, Chla, and Chlb significantly declined under stress, particularly combined stress (Table 5). These changes lead to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, which causes the photoinhibition and oxidative injury of cellular components, such as the photosynthesis pigments [57,58]. Carotenoids are potential antioxidants during plant stress [50]. They act as light harvesters, quenchers and scavengers of triplate state chlorophylls and singlet oxygen species, dissipation excess energy during stress and membrane stabilizers [59]. Excess ROS production under drought and heat stress leads to cell oxidative damage, consequent inhibition of photosynthesis, damage to cellular structures, growth reduction and premature senescence [60,61,62]. Lipid peroxidation, an important criterion for evaluating the negative effects of stress on cell membranes, can be indirectly measured by malondialdehyde (MDA) content and electrolyte leakage. Combined stress reduced non-structural carbohydrates in cotyledons and hypocotyl except for roots (Figure 4). Different stresses significantly reduced starch, TSS, and NRS concentration, relative to the control.

Increased production of phytosterols imparted cross-tolerance to combined stress of heat and drought (Table 8). Under different stress combinations, we observed a relatively higher expression of campesterol in the cotyledon of WWM-09 and WWM-21 (Table 8). Campesterol is a precursor of oxidized steroids acting as growth hormones collectively named brassinosteroids (BRs). Ahammed, et al. [63] reported that brassinosteroids induce stress tolerance to abiotic stresses (high temperature, chilling, drought, salinity, and heavy metals).

Increased production of phytosterols has been observed to impart cross-tolerance to the combined stresses of heat and drought (Table 8). Phytosterols, particularly campesterol, are crucial in enhancing stress tolerance mechanisms. Under varying stress conditions, the cotyledons of WWM-09 and WWM-21 displayed significantly higher expression levels of campesterol (Table 8). Campesterol is a precursor to oxidized steroids that function as growth hormones collectively known as brassinosteroids (BRs).

Brassinosteroids are vital in plant growth and development and enhance resistance to various abiotic stresses. This enhanced stress tolerance is achieved through multiple pathways, including the upregulation of stress-responsive genes, improvement in photosynthetic efficiency, and stabilization of cell membranes. Additionally, brassinosteroids facilitate the synthesis of antioxidant enzymes, which mitigate oxidative damage caused by environmental stresses [64].

The interplay between campesterol and brassinosteroids highlights the sophisticated mechanisms plants employ to cope with adverse environmental conditions. The higher expression of campesterol in WWM-09 and WWM-21 suggests a robust adaptive response, contributing to their resilience under combined heat and drought stress. This finding underscores the potential of manipulating phytosterol pathways to enhance crop tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses, which is crucial for sustaining agricultural productivity in the face of climate change. Research indicates that further investigation into brassinosteroids’ specific pathways and regulatory mechanisms could provide deeper insights into developing stress-resistant crops [65,66]. Understanding these complex interactions will enable the development of strategies to improve crop resilience, ensuring food security in increasingly unpredictable climates.

In Figure 6e (−0.09 MPa; 38 °C), stigmasterol was observed to be highly associated with Chl a and Chl b. Stigmasterols play a crucial role in transmembrane signal transduction by forming specialized lipid microdomains within the cellular membranes. These microdomains, often called “lipid rafts”, serve as essential anchoring platforms for various signaling enzyme complexes, facilitating the efficient transmission of signals across the membrane [67,68]. Beyond their structural role in membrane architecture, sitosterols significantly influence the activity of integral membrane proteins. This includes a wide range of functional proteins, such as enzymes, ion channels, receptors, and components of signal transduction pathways, notably ATPases. These proteins are crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis and mediating responses to environmental stimuli [69]

The presence of stigmasterol and sitosterol in the membrane contributes to the dynamic organization and fluidity of the lipid bilayer, which is vital for the proper functioning of these integral proteins. The modification of membrane fluidity and protein activity by these sterols highlights their importance in cellular processes, particularly under stress conditions, such as high temperatures and osmotic stress, as indicated by the experimental conditions in Figure 6e.

5. Conclusions

Drought stress reduces relative water content and membrane stability, affecting plant growth. The tolerant accessions maintained significantly higher growth rates and biomass under combined stress (heat and drought) than the sensitive accessions, mainly due to the protection of the photosynthetic pathway. The combined stress also increased osmolyte concentration and antioxidative compounds in tolerant accessions. The results confirm that campesterol is a major component of the sterol fraction of citron watermelon embryonic leaves. Considering different genotypes and treatment conditions, variations in sterol composition depend on both the genotype and environmental factors, while changes in the main lipid classes are mainly determined by genetic background. During exposure to stress, citron watermelon tends to accumulate specific sterols, suggesting that sterols have a prominent role in plants’ tolerance to stress. It was also found that increased synthesis of stigmasterol during heat/drought may be associated with the inherent stress resistance of citron watermelon. The characteristics of phytosterol changes in examined accessions allowed the selection of interesting citron watermelon genotypes, i.e., WWM-09 and WWM-21, to be chosen for in-depth examination. Additional research on other treatments, such as salinity and other parameters (lipid peroxidation), could be investigated and monitored. The relation of campesterol levels in WWM-09 and WWM-21 with respect to stigmasterol content is another aspect that would be worth examining.

Author Contributions

T.M. (Takudzwa Mandizvo) carried out the paper’s initial conceptualization. T.M. (Takudzwa Mandizvo) then led the paper’s write-up, and all authors (T.M. (Tafadzwanashe Mabhaudhi), J.M. and A.O.O.) reviewed and approved the paper before submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, the study did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD), Bela-Bela, Limpopo Province, South Africa, is acknowledged for providing citron watermelon accessions used in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mashilo, J.; Shimelis, H.; Odindo, A.O.; Amelework, B. Genetic diversity and differentiation in citron watermelon [var.] landraces assessed by simple sequence repeat markers. Sci. Hortic. 2017, 214, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwepe, R.M.; Shimelis, H.; Mashilo, J. Variation in South African citron watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides [L.H. Bailey] Mansf. ex Greb.) landraces assessed through qualitative and quantitative phenotypic traits. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 2495–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwepe, R.M.; Mashilo, J.; Shimelis, H. Progress in genetic improvement of citron watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides): A review. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2019, 66, 735–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, D.; Seymen, M.; Süheri, S.; Yavuz, N.; Türkmen, Ö.; Kurtar, E.S. How do rootstocks of citron watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides) affect the yield and quality of watermelon under deficit irrigation? Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 241, 106351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandizvo, T.; Odindo, A.O.; Mashilo, J.; Magwaza, L.S. Drought tolerance assessment of citron watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides (L.H. Bailey) Mansf. ex Greb.) accessions based on morphological and physiological traits. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2022, 180, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saroj, P.L.; Choudhary, B.R. Improvement in cucurbits for drought and heat stress tolerance—A review. Curr. Hortic. 2020, 8, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes do Ó, L.M.; Cova, A.M.W.; Neto, A.D.d.A.; da Silva, N.D.; Silva, P.C.C.; Santos, A.L.; Gheyi, H.R.; da Silva, L.L. Osmotic adjustment, production, and post-harvest quality of mini watermelon genotypes differing in salt tolerance. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 306, 111463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, N. Can grafting affect yield and water use efficiency of melon under different irrigation depths in a semi-arid zone? Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.L.D.; Pereira, F.H.F.; Sousa, V.F.D.E.O.; Suassuna, C.D.F.; Santos, A.P.D.L.; Barros JÚNior, A.P. Cytokinin and Auxin Influence on Growth and Quality of Watermelon Irrigated with Saline Water. Rev. Caatinga 2022, 35, 677–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.M.R.; Barros, A.C.; Silva, R.B.; Galdino, W.d.O.; Souza, J.W.G.d.; Marques, I.C.d.S.; Sousa, J.I.d.; Lira, V.d.S.; Melo, A.F.; Abreu, L.d.S.d. Impact of Photosynthetic Efficiency on Watermelon Cultivation in the Face of Drought. Agronomy 2024, 14, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawaha, A.R.M.S.; Odat, N.; Benkeblia, N.; Kerkoub, N.; Labidi, Z.; Boumendjel, M.; Nasri, H.; Imran; Amanullah; Khalid, S. Breeding Crops for Tolerance to Salinity, Heat, and Drought. In Climate Change and Agriculture: Perspectives, Sustainability and Resilience; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 95–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kunene, S.; Odindo, A.O.; Gerrano, A.S.; Mandizvo, T. Screening Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subterranea L. Verdc) Genotypes for Drought Tolerance at the Germination Stage under Simulated Drought Conditions. Plants 2022, 11, 3562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.H.; Pramanik, K.; Ajaharuddin, S.; Kundu, S.; Alam, M.A.; Islam, S.; Pal, A.; Atta, K.; Pande, C.B. Effects of Climate Change on Plant Growth and Development. In Climate-Resilient Agriculture; Apple Academic Press: Waretown, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 9–79. [Google Scholar]

- Stagnari, F.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M. Drought stress effects on crop quality. In Water Stress and Crop Plants: A Sustainable Approach; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Volume 2, pp. 375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Shabaan, M.; Asghar, H.N.; Zahir, Z.A.; Zhang, X.; Sardar, M.F.; Li, H. Salt-tolerant PGPR confer salt tolerance to maize through enhanced soil biological health, enzymatic activities, nutrient uptake and antioxidant defense. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 901865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, U.; Morris, W.L.; Ducreux, L.J.M.; Yavuz, C.; Asim, A.; Tindas, I.; Campbell, R.; Morris, J.A.; Verrall, S.R.; Hedley, P.E.; et al. Physiological, Biochemical, and Transcriptional Responses to Single and Combined Abiotic Stress in Stress-Tolerant and Stress-Sensitive Potato Genotypes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magana Ugarte, R.; Escudero, A.; Gavilan, R.G. Metabolic and physiological responses of Mediterranean high-mountain and alpine plants to combined abiotic stresses. Physiol. Plant 2019, 165, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akashi, K.; Miyake, C.; Yokota, A. Citrulline, a novel compatible solute in drought-tolerant wild watermelon leaves, is an efficient hydroxyl radical scavenger. FEBS Lett. 2001, 508, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, W.A.; Atri, N.; Ahmad, J.; Qureshi, M.I.; Singh, B.; Kumar, R.; Rai, V.; Pandey, S. Drought mediated physiological and molecular changes in muskmelon (Cucumis melo L.). PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, R.M.; Ruiz, J.M.; Garcia, P.C.; Lopez-Lefebre, L.R.; Sanchez, E.; Romero, L. Resistance to cold and heat stress: Accumulation of phenolic compounds in tomato and watermelon plants. Plant Sci. 2001, 160, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonny, M.E.; Rodriguez Torresi, A.; Cuyamendous, C.; Reversat, G.; Oger, C.; Galano, J.M.; Durand, T.; Vigor, C.; Nazareno, M.A. Thermal Stress in Melon Plants: Phytoprostanes and Phytofurans as Oxidative Stress Biomarkers and the Effect of Antioxidant Supplementation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8296–8304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Bie, Z.; He, S.; Hua, B.; Zhen, A.; Liu, Z. Improving cucumber tolerance to major nutrients induced salinity by grafting onto Cucurbita ficifolia. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 69, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandizvo, T.; Odindo, A.O.; Mashilo, J. Citron Watermelon Potential to Improve Crop Diversification and Reduce Negative Impacts of Climate Change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Wang, L.; Shao, P.; Lu, B.; Chen, Y.; Sun, P. Simultaneous analysis of free phytosterols and phytosterol glycosides in rice bran by SPE/GC–MS. Food Chem. 2022, 387, 132742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Yang, H.; Ma, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Q.; Chen, M.; Ma, Y. Determination of three oryzanols in rice by mixed-mode solid-phase extraction coupled with high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Se Pu Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2022, 40, 746–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlag, S.; Gotz, S.; Ruttler, F.; Schmockel, S.M.; Vetter, W. Quantitation of 20 Phytosterols in 34 Different Accessions of Quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 9856–9864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Dai, T.; Chen, M.; Liu, C.-m.; Ruan, R.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Characterization of lipid compositions, minor components and antioxidant capacities in macadamia (Macadamia integrifolia) oil from four major areas in China. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, T.W.T.; Roessner, U. Extraction of Plant Lipids for LC-MS-Based Untargeted Plant Lipidomics. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1778, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, K.M.; Prabutzki, P.; Leopold, J.; Nimptsch, A.; Lemmnitzer, K.; Vos, D.R.N.; Hopf, C.; Schiller, J. A new update of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in lipid research. Prog. Lipid Res. 2022, 86, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamode Cassim, A.; Gouguet, P.; Gronnier, J.; Laurent, N.; Germain, V.; Grison, M.; Boutte, Y.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P.; Simon-Plas, F.; Mongrand, S. Plant lipids: Key players of plasma membrane organization and function. Prog. Lipid Res. 2019, 73, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, S.M.; Fernie, A.R.; Nikoloski, Z.; Brotman, Y. Towards model-driven characterization and manipulation of plant lipid metabolism. Prog. Lipid Res. 2020, 80, 101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q.; Ufer, G.; Bartels, D. Lipid signalling in plant responses to abiotic stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 1029–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Szakiel, A. The role of sterols in plant response to abiotic stress. Phytochem. Rev. 2020, 19, 1525–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valitova, J.N.; Sulkarnayeva, A.G.; Minibayeva, F.V. Plant Sterols: Diversity, Biosynthesis, and Physiological Functions. Biochemistry 2016, 81, 819–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, Y.; Gerbeau-Pissot, P.; Buhot, B.; Thomas, D.; Bonneau, L.; Gresti, J.; Mongrand, S.; Perrier-Cornet, J.M.; Simon-Plas, F. Depletion of phytosterols from the plant plasma membrane provides evidence for disruption of lipid rafts. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 3980–3991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, M.A.; Wani, S.H.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Burritt, D.J.; Tran, L.-S.P. Drought Stress Tolerance in Plants; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboobucker, S.I.; Suza, W.P. Why do plants convert sitosterol to stigmasterol? Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dufourc, E.J. The role of phytosterols in plant adaptation to temperature. Plant Signal Behav. 2008, 3, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, R.; Ewas, M.; Harlina, P.W.; Khan, S.U.; Zhenyuan, P.; Nie, X.; Nishawy, E. beta-Sitosterol differentially regulates key metabolites for growth improvement and stress tolerance in rice plants during prolonged UV-B stress. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Kawasaki, K.; Daimon, S.; Kitagawa, W.; Yamamoto, K.; Tamaki, H.; Tanaka, M.; Nakatsu, C.H.; Kamagata, Y. A hidden pitfall in the preparation of agar media undermines microorganism cultivability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 7659–7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Hao, W.; Gong, D. Effects of Water Stress on Germination and Growth of Linseed Seedlings (Linum usitatissimum L.), Photosynthetic Efficiency and Accumulation of Metabolites. J. Agric. Sci. 2012, 4, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, C. Growth, Development, Transpiration and Translocation as Affected by Abiotic Environmental Factors. In Plant Factory; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.; Bian, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Jin, L. An efficient greenhouse method to screen potato genotypes for drought tolerance. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 253, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meher, P.; Shivakrishna, P.; Ashok Reddy, K.; Manohar Rao, D. Effect of PEG-6000 imposed drought stress on RNA content, relative water content (RWC), and chlorophyll content in peanut leaves and roots. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 25, 285–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turakainen, M.; Hartikainen, H.; Seppanen, M.M. Effects of selenium treatments on potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) growth and concentrations of soluble sugars and starch. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 5378–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panjekobi, M.; Einali, A. Trehalose treatment alters carbon partitioning and reduces the accumulation of individual metabolites but does not affect salt tolerance in the green microalga Dunaliella bardawil. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2021, 27, 2333–2344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, P.; Jacobs, J.L.; Deighton, M.H.; Panozzo, J.F. A high-throughput method using Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography to determine water-soluble carbohydrate concentrations in pasture plants. Grass Forage Sci. 2018, 73, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCready, R.M.; Guggolz, J.; Silviera, V.; Owens, H.S. Determination of Starch and Amylose in Vegetables. Anal. Chem. 2002, 22, 1156–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, D.M.; DeLong, J.M.; Forney, C.F.; Prange, R.K. Improving the thiobarbituric acid-reactive-substances assay for estimating lipid peroxidation in plant tissues containing anthocyanin and other interfering compounds. Planta 1999, 207, 604–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, J.S.; Kopsell, D.A. Physiological role of carotenoids and other antioxidants in plants and application to turfgrass stress management. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2009, 37, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Niu, Y.; Liu, L.; Su, A.; Hu, C.; Meng, Y. Development of a GC–MS/SIM method for the determination of phytosteryl esters. Food Chem. 2019, 281, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altunoglu, Y.C.; Keles, M.; Can, T.H.; Baloglu, M.C. Identification of watermelon heat shock protein members and tissue-specific gene expression analysis under combined drought and heat stresses. Turk. J. Biol. 2019, 43, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesca, S.; Vitale, L.; Arena, C.; Raimondi, G.; Olivieri, F.; Cirillo, V.; Paradiso, A.; Pinto, M.C.; Maggio, A.; Barone, A.; et al. The efficient physiological strategy of a novel tomato genotype to adapt to chronic combined water and heat stress. Plant Biol. 2021, 24, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, D.; Rouphael, Y.; Colla, G.; Venema, J.H. Grafting as a tool to improve tolerance of vegetables to abiotic stresses: Thermal stress, water stress and organic pollutants. Sci. Hortic. 2010, 127, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, S.K.; Pandey, R.; Sharma, S.; Gayacharan; Vengavasi, K.; Dikshit, H.K.; Siddique, K.H.M.; Singh, M.P. Cross tolerance to phosphorus deficiency and drought stress in mungbean is regulated by improved antioxidant capacity, biological N2-fixation, and differential transcript accumulation. Plant Soil. 2021, 466, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandizvo, T.; Odindo, A.O.; Mashilo, J.; Sibiya, J.; Beck-Pay, S.L. Phenotypic Variability of Root System Architecture Traits for Drought Tolerance among Accessions of Citron Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus var. citroides (L.H. Bailey). Plants 2022, 11, 2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Gill, S.S.; Fujita, M. Drought stress responses in plants, oxidative stress, and antioxidant defense. In Climate Change and Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 209–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mathur, S.; Agrawal, D.; Jajoo, A. Photosynthesis: Response to high temperature stress. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2014, 137, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uarrota, V.G.; Stefen, D.L.V.; Leolato, L.S.; Gindri, D.M.; Nerling, D. Revisiting Carotenoids and Their Role in Plant Stress Responses: From Biosynthesis to Plant Signaling Mechanisms During Stress. In Antioxidants and Antioxidant Enzymes in Higher Plants; Gupta, D.K., Palma, J.M., Corpas, F.J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 207–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hajihashemi, S.; Sofo, A. The effect of polyethylene glycol-induced drought stress on photosynthesis, carbohydrates and cell membrane in Stevia rebaudiana grown in greenhouse. Acta Physiol. Plant 2018, 40, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Hassan, M.; Rasool, T.; Iqbal, C.; Arshad, A.; Abrar, M.; Abrar, M.M.; Habib-ur-Rahman, M.; Noor, M.A.; Sher, A.; Fahad, S. Linking Plants Functioning to Adaptive Responses Under Heat Stress Conditions: A Mechanistic Review. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2021, 41, 2596–2613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, A.; Gelani, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Heat tolerance in plants: An overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 61, 199–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, G.J.; Li, X.; Liu, A.; Chen, S. Brassinosteroids in plant tolerance to abiotic stress. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2020, 39, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Alam, M.N.; Chan, Z.; Sabagh, A.E.; Fahad, S.; Hasanuzzaman, M. Heat-Induced Oxidative Stress in Plants: Consequences and Survival Mechanisms. In Improvement of Plant Production in the Era of Climate Change; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 41–70. [Google Scholar]

- Vardhini, B.V.; Anjum, N.A. Brassinosteroids make plant life easier under abiotic stresses mainly by modulating major components of antioxidant defense system. Front. Environ. Sci. 2015, 2, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajguz, A.; Hayat, S. Effects of brassinosteroids on the plant responses to environmental stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Ikonen, E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature 1997, 387, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingwood, D.; Simons, K. Lipid Rafts As a Membrane-Organizing Principle. Science 2010, 327, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, I.; Milon, A.; Nakatani, Y.; Ourisson, G.; Albrecht, A.-M.; Benveniste, P.; Hartman, M.-A. Differential effects of plant sterols on water permeability and on acyl chain ordering of soybean phosphatidylcholine bilayers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 6926–6930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).