Abstract

Obtaining enzymes through bioconversion depends on a complex relationship between the microorganisms and the biomass used. Here, we evaluate xylanase production by diverse actinobacterial species, cultivated using xylan as the sole carbon source and complex media containing sorghum as the substrate. Fifty-three actinobacteria were tested for xylanase production in a solid medium. Seventeen strains produced xylanase and were tested for their ability to produce xylanase, total cellulases (filter paper activity, FPase), and endoglycanase in submerged culture using a defined liquid medium. The best xylanase-producing species was Streptomyces capoamus, yielding 24 IU·mL−1. For FPase, Streptomyces sp. showed the highest yield (1.12 IU·mL−1); for endoglycanase, the best producer was Streptomyces ossamyceticus (0.99 IU·mL−1). When sweet sorghum was used alone, S. curacoi, S. ossamyceticus, and S. capoamus showed xylanase activities of 4.5 IU·mL−1, 4.4 IU·mL−1, and 0.8 IU·mL−1, respectively. However, FPase activity was not detected under the assay conditions. The results showed that there is an intraspecific difference in xylanase, endoglucanase, and FPase production by actinobacteria, with the species S. curacoi, S. ossamyceticus, and S. capoamus able to use sorghum as a carbon source, demonstrating biotechnological potential.

1. Introduction

Enzymatic hydrolysis is a sustainable method to convert biomass into biofuels and biotechnological products [1]. This process has been shown to facilitate the release of sugars that make up the plant’s cell wall without generating undesirable by-products [2]. From a commercial perspective, the high cost of these enzymes is directly related to the substrates used to cultivate the producing microorganisms [3]. It is imperative to explore the use of lower-cost, readily available substrates to increase the competitiveness of enzyme production [3].

Agro-industrial residues have been documented as a potential means of reducing the cost of enzyme production [4,5,6]. Sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench), a C4 grass with a high capacity to convert solar energy into chemical energy, can be used as a carbon source to grow enzyme-producing microorganisms [6,7,8]. This sorghum variety has stalks with juice rich in fermentable sugars, like sugarcane juice. The processing of this juice meets the demand to produce first-generation ethanol in the same facilities used for sugarcane [9]. The juice can be used to make sorghum syrup and sorghum molasses. The bagasse, which is the resulting lignocellulosic biomass, has a higher biological value than sugarcane bagasse for animal feed and can be used to generate heat, energy, second-generation ethanol [9,10,11] and generate high value-added products such as oligosaccharides [12], lactic acid [13], growth promoting substrates [14], biopesticides [15], bioplastics [16], biosurfactants [17] solvents and bioactive compounds [18], butyric acid, hydrogen and methane [19] waxes, proteins and allelopathic compounds such as sorgoleone, the latter a biomolecule that has been studied as a natural herbicide [20,21] and algaecide [22] and is considered promising in a biorefinery context.

The composition of plant biomass is mainly cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, which can be broken down into fermentable sugars and high-value molecules [23]. The cell wall of sorghum differs structurally from that of other grasses, such as maize. Studies suggest that interactions between triple-threaded xylan and amorphous cellulose dominate the architecture of the sorghum cell wall. In sorghum, the holocellulosic fraction (cellulose and hemicellulose) is mainly made up of arabinoxylans, which show variations in the ratio between the structural xylose and arabinose, forming a triple screw conformation due to dense arabinosyl substitutions, in close proximity to cellulose [24]. The secondary cell walls of sorghum have a high proportion of amorphous and crystalline cellulose compared to those of dicotyledonous plants. In addition, the structure of the lignin in the plant cell wall can vary in the ratio of syringyl/guaiacyl monolignols (S/G) between different cultivars [25]. The diversity of plant cell wall constituents underscores the need to use lignocellulosic biomass in enzyme production tests, as synthetic media may not reflect the original structure to be transformed [19].

Deconstructing the plant cell wall requires a set of enzymes specific to the substrate, which is why some microorganisms can use one carbon source to the detriment of another; evolutionarily, they have acquired distinct genetic alterations directed by the environment and their symbiotic relationships [26]. Additionally, different microorganisms respond differently to this stimulus because they act synergistically in their natural environment. Testing a substrate with different microorganisms helps determine its productive performance. Studies show that different enzymes with the same activity from different organisms vary in terms of robustness, temperature, and pH tolerance, which makes the taxonomic, physiological, and ecological diversity of the organisms studied desirable [26]. Selecting microorganisms that produce holocellulolytic enzymes will enable the construction of an optimized cocktail for sorghum biomass to obtain monomers of interest.

Actinobacteria are among those microorganisms and have the potential to produce enzymes capable of degrading holocellulose [27,28,29]. The significance of this production extends beyond the agricultural sector, encompassing applications across food, pharmaceuticals, textiles, and paper manufacturing [29]. In fact, actinobacterial enzymes can either complement or substitute for chemical analogs, yielding satisfactory outcomes. Streptomyces species are among the leading producers of biologically active secondary metabolites, with enzymes as the main products after antibiotics [30]. They can biodegrade various recalcitrant organic molecules, thereby reducing the need for chemical additives to alter biomass rheology [31]. From a commercial standpoint, the high cost of these enzymes is directly related to the substrates utilized to cultivate the producing microorganisms. To enhance the competitiveness of enzyme production, it is imperative to explore the use of lower-cost, readily available substrates [28,32].

The description of new hydrolytic enzymes is an essential step in developing techniques that use lignocellulosic materials as a starting point to produce fuels and derived bioproducts. Therefore, the present study was carried out to evaluate the potential of Actinobacteria isolated from Brazilian Cerrado soils, cultivated in synthetic medium (xylan) and lignocellulosic biomass (sweet sorghum), to produce hydrolytic enzymes, including xylanase, FPase, and endoglycanase.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass

The sweet sorghum samples were obtained from experiments conducted by the sorghum breeding program at Embrapa Maize and Sorghum—Sete Lagoas, Minas Gerais, Brazil. The sweet sorghum stalks of the CMSXS5021 genotype were harvested by hand and crushed in an IRBI DM540 chopper (IRBI, Araçatuba, SP, Brazil). The material was then dried in a Solab model SL102/96 air circulation oven (Solab, Limeira, SP, Brazil) at 65 °C until constant weight. The samples were then ground to a particle size of 2 mm in a Willey-type knife mill R-TE-650/1 (Tecnal, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil). The physical and chemical characterization was carried out according to the methodology described by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) [33,34,35].

2.2. Microorganisms

The experiment involved an initial screening of 53 strains previously isolated and identified in advance [36,37] belonging to the Collection of Multifunctional Microorganisms and Phytopathogens of Embrapa Maize and Sorghum (CMMP-MS), Sete Lagoas, MG (Table 1). The experiments were conducted at the Laboratory of Microbiology and Biochemistry of Soils, part of Embrapa Maize and Sorghum.

Table 1.

List of used actinobacteria.

2.3. Selection of Xylanase-Producing Actinobacteria and Cultivation Conditions

Microorganisms were selected by identifying xylanase enzyme activity in a solid medium, as follows. Colonies isolated from each bacterial strain grown in BDA medium were resuspended in a sterile 0.85% saline solution, and 200 μL aliquots of this suspension were distributed in ELISA plate wells containing 96 cavities. Subsequently, a sample of each suspension was transferred to a 150 × 15 mm2 Petri dish containing 10 g L−1 xylan medium (beechwood xylan, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). The following substances were used in the experiment: 0.6 g L−1 yeast extract, 7.0 g L−1 KH2PO4, 2.0 g L−1 K2HPO4, 0.1 g L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 1.0 g L−1 (NH4)2SO4, 15 g L−1 agar. The pH was corrected to 5.3. The halos surrounding each colony were measured using a universal analog caliper (series 530, Mitutoyo Corporation, kawasaki, Kanagawa, Japan) after a 72 h incubation period at 30 °C. These halos represent the xylan-degrading capacity of the samples, and their enzymatic indices (EI) were estimated according to the methodology recommended by LOPES et al. [38]. The EI was calculated using the following equation: EI = ratio of halo diameter/ratio of colony diameter.

The degradation halo was revealed using Congo Red (1%), followed by successive washes with 1 M NaCl and stabilization of the growth by a wash/flood of the plate with 1 M HCl [39,40].

2.4. Evaluation of Enzymatic Activity on Beechwood Xylan in Submerged Fermentation (Smf)

The capacity of Actinobacteria to produce xylanase in a liquid medium containing xylan as a carbon source was investigated. The medium contained 10.0 g·L−1 xylan (xylan beechwood—Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA). The following substances were used: 3.0 g L−1 yeast extract, 7.0 g L−1 KH2PO4, 2.0 g L−1 K2HPO4, 0.1 g L−1 MgSO4·7H2O, 1.0 g L−1 (NH4)2SO4, 5.0 g L−1 peptone. The pH was corrected to 6.0. The media were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min. A fully colonized mycelial disk was transferred to a 50 mL Erlenmeyer flask containing 30 mL of the previously described culture medium. The inoculum was cultivated for 48 h at 150 rpm and 30 °C.

2.5. Evaluation of Enzymatic Activity in Submerged Fermentation (Smf) of Lignocellulosic Biomass Using Sweet Sorghum as the Sole Carbon Source

For this evaluation, the sweet sorghum CMSXS5021 line was used. The CMSXS5021 line is a fertility-restoring (R) line and is being used as a male parent to obtain sweet sorghum hybrids. This line was selected for its high combining ability, resulting in hybrids with high biomass production and high stalk sugar/fiber content during final hybrid evaluation trials in recent harvests across different regions of the country. The CMSXS5021 line is sensitive to photoperiod, and its hybrids have a long cycle in spring sowing, an average flowering time of 120 to 150 days, and a height greater than 5 m with fresh biomass production exceeding 60 t ha−1, resistance to lodging, and moderate resistance to anthracnose, helminthosporium leaf spot, and rust. The line and its hybrids are suitable as raw materials for ethanol production, and its bagasse for steam/energy cogeneration and/or second-generation ethanol/biogas production.

The tests started by transferring 1 mL of a cell suspension (108 cells mL−1) obtained from an initial inoculum produced in liquid medium, as described in the previous section, after 24 h of culture. The actinobacteria were inoculated into a liquid medium containing 1% w/v fresh, dried sweet sorghum biomass CMSXS 5021 (without pretreatment) as the sole carbon source, along with 0.01 g K2HPO4·L−1, (NH4)2SO4 0.01 g·L−1, NaCl 0.01 g·L−1, and MgSO4·7H2O 0.01 g·L−1 [41]. The media were sterilized at 121 °C for 20 min. For this stage, three batches of inoculum were grown, the first for 48 h, the second for 72 h, and the third for 96 h at a rotational velocity of 150 rpm and a temperature of 30 °C.

2.6. Determination of Enzymatic Activities

Following the conclusion of the fermentation period, the medium was filtered using qualitative filter paper, Whatman Nº1 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences; Piscataway, NJ, USA). The medium was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 5 °C for 10 min. To evaluate enzyme activity, the crude cell-free supernatant was used as the enzyme source.

To ascertain the xylanase activity, 10 μL of the crude supernatant was added to 20 μL of xylan (xylan beechwood 2%—Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO, USA) (w/v) (substrate) with sodium citrate/citric acid buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0).

For the FPase (Filter paper activity—total cellulases) activity assay, Whatman® filter paper disks were used as the substrate with sodium citrate/citric acid buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.0), and the reaction was conducted for 60 min at 50 °C.

β-Glucosidase activity was measured using 15 mM cellobiose as the substrate in a sodium citrate/citric acid buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.0) for a 30 min reaction at 50 °C.

The substrate blank was fabricated by replacing the enzyme volume with sodium citrate/citric acid buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.0), and the enzyme blank was fabricated by replacing the substrate with buffer. For the negative control, the assay did not contain exogenous substrate.

After the enzymatic hydrolysis reaction, the DNS (Dinitrosalicylic acid) method [41] determined the release of sugars by measuring absorbance at 540 nm with a spectrophotometer FLUOstar Omega (BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany) using the Omega—Control software (program version 3.31, BMG LABTECH, Ortenberg, Germany). Enzymatic hydrolysis and DNS (3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid) reaction activities were performed in a Veriti 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

One unit of enzymatic activity (IU) was defined as the amount of enzyme required to produce 1 μmol of reducing sugar from each substrate per minute under the conditions described in the assay.

2.7. Data Analysis

All experiments were performed in biological triplicate. The data were analyzed using analysis of variance and the Scott-Knott test, with results considered significant at the p < 0.05 level in the R software environment (version 4.5.1) [42].

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Screening

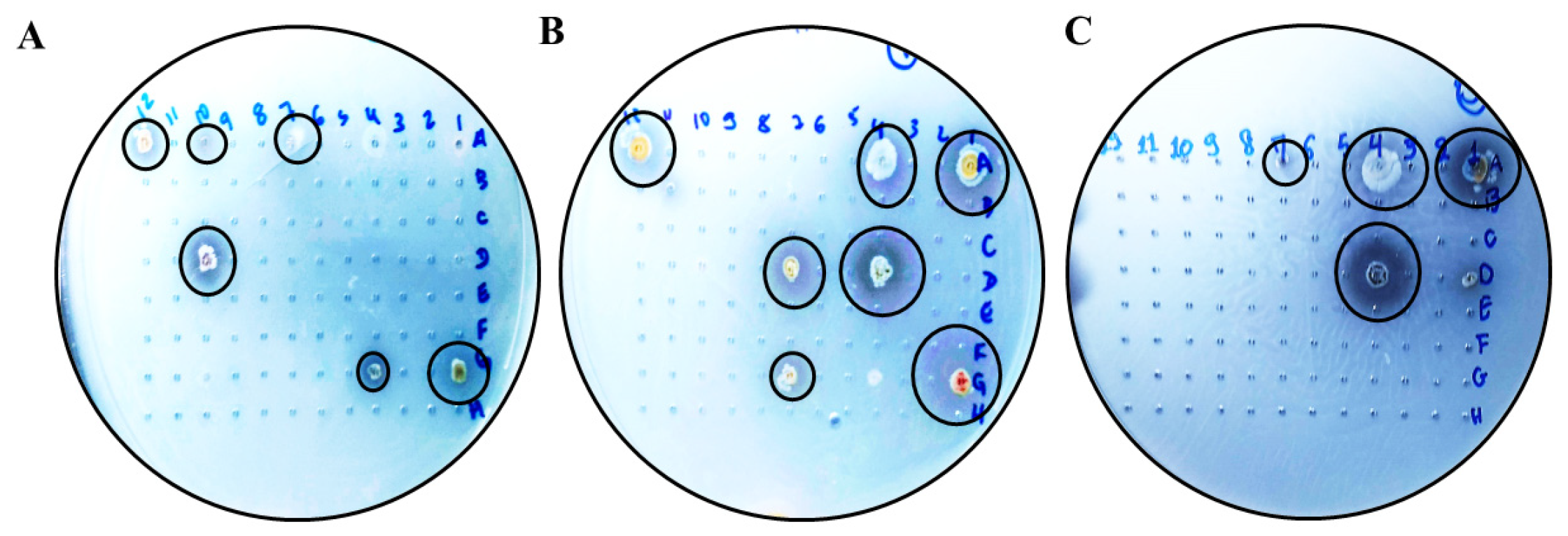

In the preliminary assay, xylan degradation was observed in only 17 of the 53 tested strains (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hydrolysis halos in solid media containing xylan as the sole carbon source. Actinobacteria grown in Petri dishes on a solid medium containing xylan as the sole carbon source (1%) to reveal a hydrolysis halo. (A–C) Visualization of halos. Highlighted in a black circle for better visualization. The strains (A505) Streptomyces sp., (AMSJ45) Streptomyces curacoi, (ARLJ49) Amycolatopsis rhabdoformis, (ACSL1) Streptomyces seymenliensis, (A404) Streptomyces chartreusis, (A465) Streptomyces sp., (ARLJ51) Streptomyces griseoruber, (ARLJ55) Streptomyces sp., (ACJ1) Streptomyces ossamyceticus, (ACJ26) Streptomyces capoamus, (ARLJ48) Streptomyces chiangmaiensis, (A509) Streptomyces deserti, (ACT115) Streptomyces thioluteus, (AE3J64) Streptomyces sp., (A402) Streptomyces sp., (AEPFSRII31) Streptomyces phaeopurpureus, (K18A18) Streptomyces sp. were able to meet the criterion of EI > 2.5.

All strains had an EI > 2.5 (Table 2). In this study, 32% of microorganisms showed positive xylanase production, thereby meeting the selection criterion of exceeding 2.5 (EI).

Table 2.

List of Actinobacteria isolates from the Embrapa Maize and Sorghum Collection of Multifunctional Microorganisms and Phytopathogens (CMMP-MS) that have been selected by the enzymatic index (IE).

3.2. Enzymatic Activity on Beechwood Xylan in Submerged Fermentation (Smf)

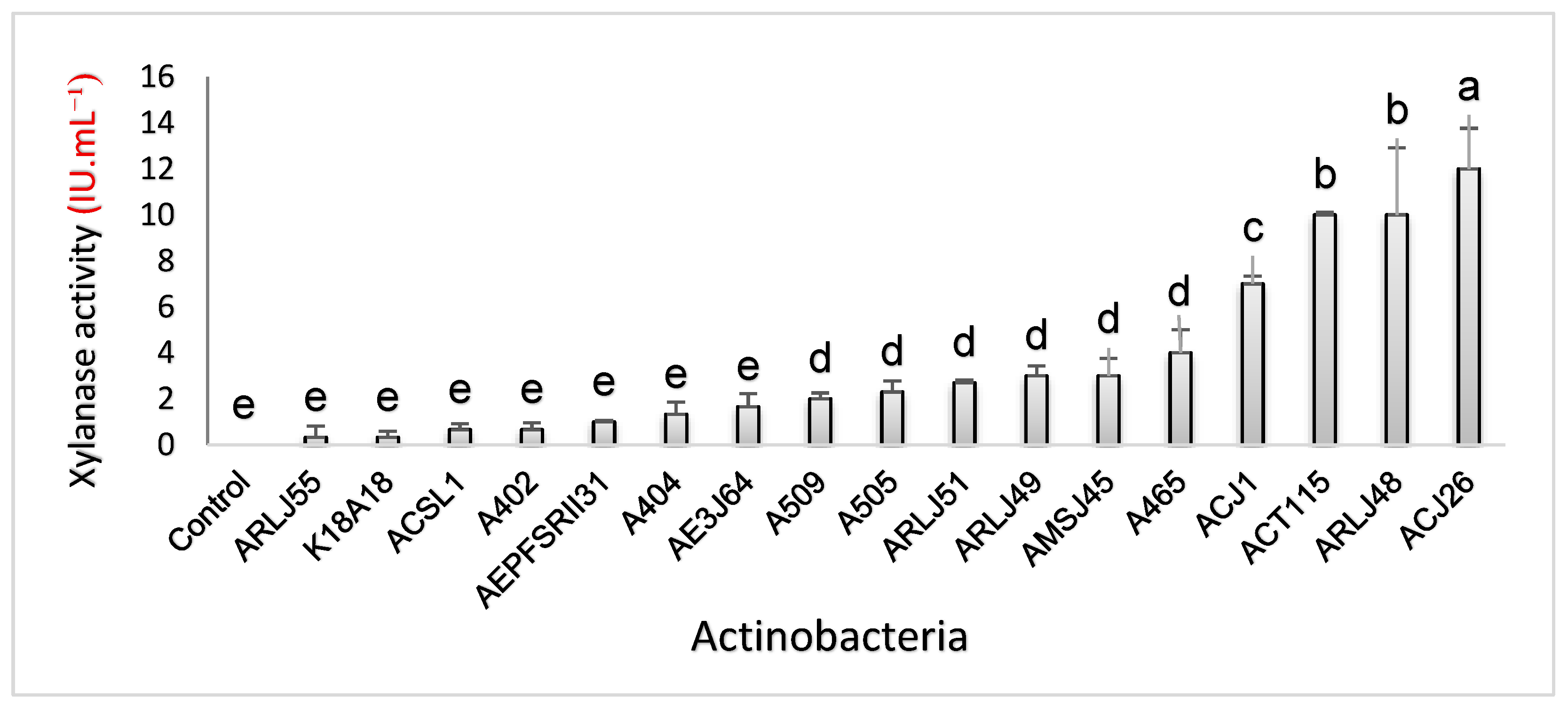

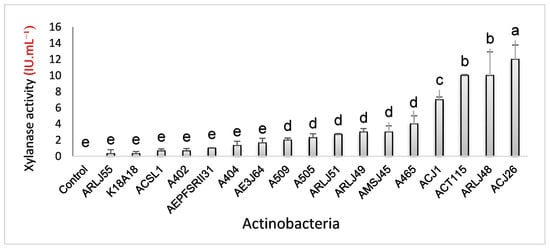

All 17 actinobacteria selected by EI in the solid culture stage produced enzymes in submerged culture when xylan was the sole carbon source (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Xylanase enzymatic activity in submerged culture containing xylan as the only carbon source. Different letters (a, b, c, d, e) indicate statistical differences according to the Scott-Knott test (p < 0.05).

In the submerged culture test using a medium containing xylan as the sole carbon source, the actinobacterium Streptomyces capoamus (ACJ26) was the best producer (12 ± 1.76 IU·mL−1), which differed statistically from the others. In second place, Streptomyces chiangmaiensis (ARLJ48) and Streptomyces thiolutheus (ACT115) were the best producers, presenting (10 ± 2.9 IU·mL−1) and (10 ± 0.11 IU·mL−1), respectively, with no statistical difference between them and differing statistically from the others. Ranked third in enzyme production, Streptomyces ossamyceticus (ACJ1) with (7 ± 0.33 IU·mL−1). Streptomyces sp. (A465) (4 ± 1 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces curacoi (AMSJ45) (3 ± 0.75 IU·mL−1), Amycolatopsis rhabdoformis (ARLJ49) (3 ± 0.43 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces griseoruber (ARLJ51) (3 ± 0.11 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces sp. (A505) (2 ± 0.48 IU·mL−1) and Streptomyces deserti (A509) (2 ± 0.25 IU·mL−1) were the fourth producing group with no statistical difference between them and the strains (AE3J64) Streptomyces sp. (2 ± 0.56 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces chartreusis (A404) (1 ± 0.52 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces phaeopurpureus (AEPFSRII31) (1 ± 0.06 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces sp. (A402) (0.66 ± 0.30 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces seymenliensis (ACSL1) (0.66 ± 0.25 IU·mL−1, Streptomyces sp. (K18A18) (0.33 ± 0.27 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces sp. (ARL55) (0.33 ± 0.48 IU·mL−1) present basal enzyme production, not differing statistically from the control.

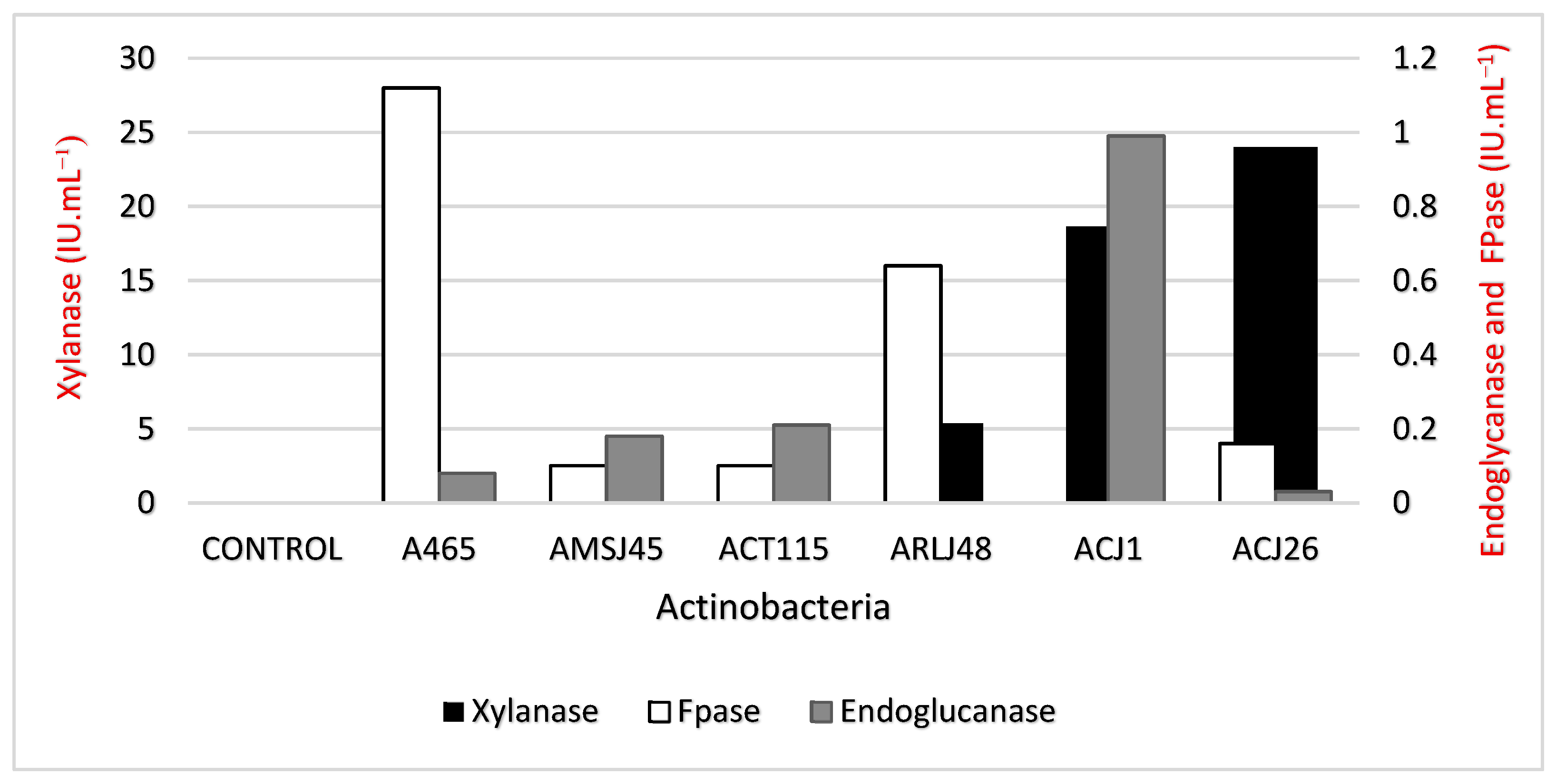

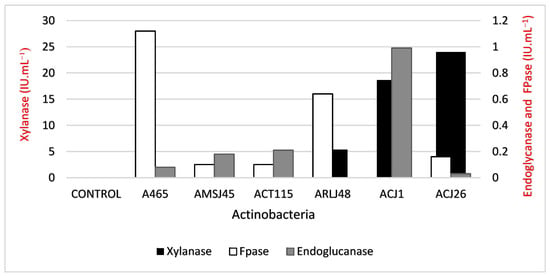

3.3. Enzymatic Activity in Submerged Culture Using Xylan as the Only Carbon Source

The six best producers of xylanase enzyme in submerged culture, Streptomyces capoamus (ACJ26), Streptomyces chiangmaiensis (ARLJ48), Streptomyces thiolutheus (ACT115), Streptomyces sp. (A465), Streptomyces curacoi (AMSJ45), and Amycolatopsis rhabdoformis (ARLJ49), were selected for further evaluation of their cellulolytic and xylanolytic activity. The activity of the enzymes xylanase, endoglycanase, and FPase (Table 3) was measured using the crude supernatant obtained at the end of 48 h of submerged fermentation.

Table 3.

Evaluation of enzymatic activity using a crude supernatant obtained from a culture of actinobacteria in a medium containing xylan (Sigma Aldrich) as the sole carbon source. Xylanase, FPase, and Endoglucanase produced by the actinobacteria S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1), S. capoamus (ACJ26), S. curacoi (AMSJ45), Streptomyces sp. (A465), S. chiangmaiensis (ARLJ48), and S. thiolutheus (ACT115) were evaluated at 48 h.

The activities for xylanase using xylan were identified. As demonstrated in Figure 3, S. capoamus (ACJ26) was the most prolific producer, reaching 24 IU·mL−1. For FPase, the highest activity was observed in Streptomyces sp. (A465), with a value of 1.12 IU·mL−1.

Figure 3.

Enzymatic activity of xylanase, FPase, and endoglycanase produced by actinobacteria when grown in a medium containing xylan as the sole carbon source.

3.4. Enzymatic Activity in Submerged Cultivation Using Sweet Sorghum Biomass as the Only Carbon Source

The carbon source in the growing medium for this step of the assay was dry sweet sorghum stalk biomass. The chemical composition of the sorghum biomass used in the test was investigated in relation to its structural sugars. The results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Structural sugars of sweet sorghum and lignin composition.

In the present study, the highest values of xylanase activity were recorded after 96 h of fermentation, when the actinobacterium S. curacoi (AMSJ45) exhibited the highest activity (4.5 ± 0.3 IU·mL−1), followed by S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1) (4.4 ± 0.9 IU·mL−1) and S. capoamus (ACJ26) (0.8 ± 0.07 IU·mL−1).

In the submerged fermentation assay using sweet sorghum biomass as the sole carbon source, FPase and endoglucanase enzymatic activity could not be detected at any of the evaluated time points, as per the assay conditions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Preliminary Screening

Xylanase activity was used as the primary criterion for selecting strains capable of expressing xylanase in a solid medium. This was followed by the obtention of a crude supernatant from the liquid medium, which was expected to contribute to the deconstruction of the hemicellulosic fraction of plant biomass. It is acknowledged that the enzymatic index, as defined on soil medium, may not reflect the enzyme production in submerged fermentation. Therefore, all microorganisms tested for xylanase production in the solid medium were also tested in the liquid medium. This procedure is followed because actinobacteria exhibit substantial heterogeneity in their developmental and metabolic processes across diverse response surfaces. It is well known that most actinobacteria do not complete their sporulation cycle in liquid medium, and their physiology is directly linked to the production of metabolites, such as extracellular enzymes [43].

Among the seventeen actinobacteria tested on solid media, the three strains with the highest EI were Streptomyces sp. (A505), S. curacoi (AMSJ45), and Amycolatopsis rhabdoformis (ARJ49) with EIs of 6.5, 5.7, and 5.6, respectively, indicating good expression of the enzyme on solid media. In turn, the three best producers of the xylanase enzyme in submerged culture were Streptomyces capoamus (ACJ26), with (12 ± 1.76 IU·mL−1), Streptomyces chiangmaiensis (ARLJ48), with (10 ± 2.9 IU·mL−1), and S. thiolutheus (ACT115), with (10 ± 0.11 IU·mL−1), differing from the best producers in solid medium. These results show that the culture medium interferes with enzyme expression, not only with respect to the composition of the substrate but also with the culture medium’s physical conditions, depending on the physiological response of the tested microorganisms.

Several authors have described the enzyme index (EI) as a reproducible and straightforward method for evaluating the enzymatic activity of microorganisms isolated from diverse environments in solid media. These include Dornelas et al. [36], who, in their work characterizing actinobacteria isolated from Cerrado soil, found amylase, cellulase, and lipase activity in most of the tested isolates. Among these, the strains S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1) and S. capoamus (ACJ26) showed EI values of 4.42 and 3.83, respectively, for cellulase using carboxymethylcellulose as a substrate. In the present study, xylan was used as a substrate in the solid medium, and the same microorganisms showed an EI of 3 for xylanase activity. Omar et al. and Sanjivkumar et al. [43,44] reported a maximum EI of 3.25 for the actinobacteria tested for xylanase production, i.e., values lower than those reported in this study, indicating significant variability among the samples.

Integrating these two processes proved particularly valuable. This is because choosing the method of enzyme production considers the microorganism’s morphophysiology and how it can affect substrate hydrolysis [26]. Actinobacteria can produce filamentous vegetative cells that adhere to solid surfaces [45]. In liquid media, they can produce exopolysaccharides, forming structures that capture particulates from xylan or biomass suspended in the medium, demonstrating different strategies for nutrient capture depending on the environment in which they are inserted [46].

4.2. Enzymatic Activity on Beechwood Xylan in Submerged Fermentation (Smf)

The literature shows that the xylanolytic activity of enzymes produced by Streptomyces varies across species and cultivation conditions. Tuncer et al. [47] obtained 22.41 IU·mL−1 in optimized production conditions in a medium containing oat xylan after 4 days of incubation at 30 °C. Here, the best producer, Streptomyces capoamus (ACJ26), reached an activity of 12 ± 1.76 IU·mL−1 after 48 h. Nascimento et al. [48], working with actinobacteria isolated from Cerrado soil, observed xylanase activities of 70 U·mL−1 with Larchwood’s xylan as substrate. Higher activity values were observed here, but after a longer cultivation time. Cultivation time can be crucial for determining enzymatic activity, as some actinobacterial strains grow slowly, requiring a longer production interval. Activities that investigate optimization models are also helpful in improving activity levels because they yield comparatively higher values than the initial screening, thereby promoting adjustments in nutritional, physical, and chemical parameters to improve production.

In previous work, Dornelas et al. [36] evaluated endoglycanase production (CMcase) by S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1) and S. capoamus (ACJ26) in solid medium using CMC as substrate. Their hypothesis was corroborated in the present study, now in liquid medium, though with a very low endoglycanase production. In addition, S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1) did not show FPase activity in any of the tests. The FPase activity of S. capoamus (ACJ26) was also considered low (0.16 U·mL−1). This suggests that both actinobacterial strains could be used to degrade xylan in processes where cellulolytic enzymes should be absent [49].

In studies evaluating the production of cellulase-free xylanases by Streptomyces sp., Techapun et al. [50] and Praddeep et al. [51] observed enzymatic activities of 12.5 U·mL−1 and 4197.1 U·mL−1, respectively, using milled sugarcane bagasse and wheat bran as carbon sources. The initial study yielded results lower than those observed here, whereas the second study reported significantly higher values. This discrepancy can be attributed to the methodology used in the second study, which included a purification step of the enzyme. These microorganisms are recommended for the paper bleaching industry, as it is considered an eco-friendly bleaching method that significantly reduces the load of toxic waste from lignin chlorination [51,52].

In his work with actinobacteria isolated from soil, Hamedi [52] reported a pulp bleaching process for paper production that reduced the use of chlorinates by 25% when using only fermentation juice, without enzymatic purification. The results were comparable to those obtained with purified broth, reinforcing the idea that biotechnological approaches are environmentally friendly and serve as alternatives to traditional chemical methods. Porsuk [49] reported values of 255 U mL−1 in an optimized assay at 60 °C, using a medium supplemented with yeast extract and xylan spelt, under submerged fermentation at an alkaline pH.

4.3. Enzymatic Activity in Submerged Cultivation Using Sweet Sorghum Biomass as the Only Carbon Source

S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1), S. capoamus (ACJ26), and S. curacoi (AMSJ45) demonstrated the ability to produce xylanase using sweet sorghum as the only carbon source. In contrast, this enzyme was undetected under the same experimental conditions in Streptomyces sp. (A465), S. chiangmaiensis (ARLJ48), and S. thioluteus (ACT115), indicating intraspecific variation in xylanase expression within the genus Streptomyces. In addition, the observed difference may be due to the biomass used, as sorghum has not undergone pretreatment. The pretreatment influences the availability of hydrolyzable fractions of the plant cell wall, which require the coordinated action of several enzymes and auxiliary molecules for effective degradation [53,54,55,56].

Regarding the incubation period for xylanase production, enzyme activity was detected after 48 h when xylan was used as the sole carbon source. On the other hand, the highest xylanase production with sorghum was reached after 96 h. Although xylanase production was lower and with a more extended incubation period, the result was considered satisfactory given that plant cell walls are interwoven structures that are recalcitrant to degradation [57,58]. Even so, three strains were able to use the biomass. Some hypotheses may explain the delay in detecting the sugars, such as the concentration of the initial inoculum, the consumption of sugars released to maintain cell growth [56,59], and the lignin content of sorghum (around 23%), which may prevent the enzymes from accessing the hemicellulose fractions, limiting the performance of the strains evaluated [59].

Previous studies indicate that xylanase production from sorghum as a carbon source can vary significantly depending on experimental conditions. For example, Adhyaru [60] reported higher xylanase production from sorghum than from other agricultural residues, with an optimal biomass concentration of 3%, a value higher than the 1% used in this work. Nitrogen is required for the biosynthesis of enzymes and other biological molecules, and a nitrogen deficit may underestimate microbial production. Dias [61] reported that sorghum, when used as a substrate to induce lignocellulolytic enzymes by filamentous fungi (A. niger) in solid culture, was most effective when supplemented with 0.5% peptone. The best fermentation condition for xylanase activity was 300 U/g. This result demonstrates that the use of sorghum can be optimized, since it has a lower nitrogen content than peptone, a commonly used nitrogen source. Danso [62], in his test with an actinobacterium isolated from termites, obtained cellulase and xylanase production after ten days of cultivation in a medium containing 15 g·L−1 wheat straw and yeast extract at 1.5%·L−1 of wheat straw and 1.5% yeast extract. The activities were estimated at 6.560 and 0.866 U mL−1, respectively, values very close to those obtained in the present work, even without nutritional enrichment, when sorghum was used.

The results demonstrate that the enzymatic activity of the actinobacteria tested using sweet sorghum biomass as the sole carbon source may be promising and can be optimized in future studies, mainly because the sorghum used in this study has not undergone any prior chemical pretreatment. In contrast, no detectable FPase activity has been observed. The highest xylanase production was observed after 96 h of fermentation, and S. curacoi (AMSJ45), S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1), and S. capoamus (ACJ26) were the best producers. This finding suggests that sorghum is a viable option for the microorganisms under discussion.

5. Conclusions

Among the actinobacterial strains evaluated for xylanase production in solid medium, 32% showed an EI between 2.5 and 6.5, indicating a good enzyme production relative to cell growth. In submerged fermentation tests, the species S. capoamus (ACJ26) and Streptomyces ossamyceticus (ACJ1) stood out for their ability to produce endoxylanase with Beechwood xylan as a carbon source, indicating their biotechnological potential for processes that require xylanolytic enzymes. Its activities reached 24 IU·mL−1 and 19 IU·mL−1, respectively. The work showed that there are intraspecific differences between actinobacteria for the enzymatic production of xylanase, Fpase, and Endoglucanase, with Streptomyces being the most representative group among the tested strains. We also concluded that the actinobacteria S. curacoi (AMSJ45), S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1), and S. capoamus (ACJ26), with results of 4.5 IU·mL−1, 4.4 IU·mL−1 and 0.8 IU·mL−1, respectively, were able to use sweet sorghum biomass as the sole carbon source to induce the production of xylanolytic enzymes without any pretreatment of the biomass. Finally, S. curacoi (AMSJ45), Streptomyces sp. (A465), S. ossamyceticus (ACJ1), S. capoamus (ACJ26), S. chiangmaiensis (ARLJ48), and S. thiolutheus (ACT115) did not show FPase activity using sweet sorghum as the only carbon source.

Overall, the production of holocellulolytic enzymes by the actinobacterial strains varied among individual isolates. Sweet sorghum induced xylanase activity in certain strains. However, responses varied considerably, possibly because some strains were unable to produce other enzymes needed to degrade sorghum biomass, given the diversity of traits, such as enhanced robustness, temperature tolerance, and pH stability. Such taxonomic, physiological, and ecological diversity is crucial for bioprospection aimed at enhancing enzymatic hydrolysis to convert plant biomass into fermentable sugars. Future work should focus on process optimization and detailed enzymatic characterization to better understand the capabilities and limitations of these actinobacteria.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.D.d.S.B., E.d.C.J., I.E.M. and M.L.F.S.; methodology, R.D.d.S.B., I.E.M., M.L.F.S. and R.A.d.C.P.; formal analysis, R.D.d.S.B.; investigation, R.D.d.S.B.; data curation, R.D.d.S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.D.d.S.B. and E.d.C.J.; writing—review and editing, E.d.C.J., I.E.M., M.L.F.S. and R.A.d.C.P.; supervision, E.d.C.J., I.E.M. and M.L.F.S.; project administration, E.d.C.J. and I.E.M.; funding acquisition, I.E.M. and M.L.F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend thanks to the Research Support Foundation of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, project no. 312781/2022-9), for E.d.C.J.’s productivity fellowship; and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, project code 0001) for providing the fellowship to R.D.S.B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated in this study are associated with microbial strains and biotechnological relevance and are therefore not publicly available at this stage, but are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Ederson da Conceição Jesus is employed by EMBRAPA Agrobiologia. Rafael Augusto da Costa Parrella, Ivanildo Evódio Marriel and Maria Lúcia Ferreira Simeone are employed by EMBRAPA Maize and Sorghum. The research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EMBRAPA | Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária |

| FPase | Filter Paper Activity |

| DNS | Dinitrosalicylic acid |

References

- Vasić, K.; Knez, Ž.; Leitgeb, M. Bioethanol production by enzymatic hydrolysis from different lignocellulosic sources. Molecules 2021, 26, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B.; Garron, M.-L. CAZac: An activity descriptor for carbohydrate-active enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D625–D633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Tsai, M.-L.; Nargotra, P.; Chen, C.-W.; Kuo, C.-H.; Sun, P.-P.; Dong, C.-D. Agro-industrial food waste as a low-cost substrate for sustainable production of industrial enzymes: A critical review. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhuja, D.; Ghai, H.; Rathour, R.K.; Kumar, P.; Bhatt, A.K.; Bhatia, R.K. Cost-effective production of biocatalysts using inexpensive plant biomass: A review. Biotech 2021, 11, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmel, M.E.; Ding, S.-Y.; Johnson, D.K.; Adney, W.S.; Nimlos, M.R.; Brady, J.W.; Foust, T.D. Biomass recalcitrance: Engineering plants and enzymes for biofuels production. Science 2007, 315, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriani, A.; Maharani, A.; Yanto, D.H.; Pratiwi, H.; Astuti, D.; Nuryana, I.; Agustriana, E.; Anita, S.H.; Juanssilfero, A.B.; Perwitasari, U.; et al. Sequential production of ligninolytic, xylanolytic, and cellulolytic enzymes by Trametes hirsuta AA-017 under different biomass of Indonesian sorghum accessions-induced cultures. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2020, 12, 100562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengerdy, R.P.; Szakács, G.; Sipocz, J. Bioprocessing of sweet sorghum with in situ-produced enzymes. In Seventeenth Symposium on Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 1996, 57–58, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonia, K.G.; Chadha, B.S.; Saini, H.S. Sorghum straw for xylanase hyper-production by Thermomyces lanuginosus (D2W3) under solid-state fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2005, 96, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laopaiboon, L.; Thanonkeo, P.; Jaisil, P.; Laopaiboon, P. Ethanol production from sweet sorghum juice in batch and fed-batch fermentations by Saccharomyces cerevisiae. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 23, 1497–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, E.; Nieves, I.; Rondon, V.; Sagues, W.; Fernández-Sandoval, M.; Yomano, L.; York, S.; Erickson, J.; Vermerris, W. Potential for ethanol production from different sorghum cultivars. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamenković, O.S.; Siliveru, K.; Veljković, V.B.; Banković-Ilić, I.B.; Tasić, M.B.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Prasad, P.V.V. Production of biofuels from sorghum. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 124, 109769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarr, P.S.; Tibiri, E.B.; Fukuda, M.; Zongo, A.N.; Compaoré, E.; Nakamura, S. Phosphate-solubilizing fungi and alkaline phosphatase trigger the P solubilization during the co-composting of sorghum straw residues with Burkina Faso phosphate rock. Front. Environ. Sci. 2020, 8, 559195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeimi, S.; Khosravi, V.; Varga, A.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Kredics, L. Screening of organic substrates for solid-state fermentation, viability and bioefficacy of Trichoderma harzianum AS12-2, a biocontrol strain against rice sheath blight disease. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanamool, V.; Imai, T.; Danvirutai, P.; Kaewkannetra, P. An alternative approach to the fermentation of sweet sorghum juice into biopolymer of poly-β-hydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) by newly isolated Bacillus aryabhattai PKV01. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2013, 18, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, A.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Chen, X.; Tucker, M.; Liang, Y. Sweet sorghum bagasse and corn stover serving as substrates for producing sophorolipids. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, C.; Qin, P.; Miao, Q.; Zhang, C.; Tan, T. Acetone–butanol–ethanol from sweet sorghum juice by an immobilized fermentation-gas stripping integration process. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 211, 704–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Shen, Z.; Tan, B.; Zhai, X. Changing the polyphenol composition and enhancing the enzyme activity of sorghum grain by solid-state fermentation with different microbial strains. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2024, 104, 6186–6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitfield, M.B.; Chinn, M.S.; Veal, M.W. Processing of materials derived from sweet sorghum for biobased products. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 37, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umakanth, A.V.; Kumar, A.A.; Vermerris, W.; Tonapi, V.A. Sweet sorghum for biofuel industry. In Breeding Sorghum for Diverse End Uses; Woodhead Publishing: Delhi, India, 2019; pp. 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimsing, A.L.; Bælum, J.; Dayan, F.E.; Locke, M.A.; Sejerø, L.H.; Jacobsen, C.S. Mineralization of the allelochemical sorgoleone in soil. Chemosphere 2009, 76, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimbal, C.I.; Pedersen, J.F.; Yerkes, C.N.; Yerkes, D.N.; Weller, S.C. Phytotoxicity and distribution of sorgoleone in grain sorghum germplasm. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1343–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.R.; Min, S.K.; Kim, J.D.; Park, S.U.; Pyon, J.Y. Sorgoleone, a sorghum root exudate: Algicidal activity and acute toxicity to the ricefish Oryzias latipes. Aquat. Bot. 2012, 98, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvarajan, E.; Swathi, S.; Sindhu, V. Xylanases: For Sustainable Bioproduct Production. In Microbial Bioprospecting for Sustainable Development; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Lipton, A.S.; Wittmer, Y.; Murray, D.T.; Mortimer, J.C. A grass-specific cellulose–xylan interaction dominates in sorghum secondary cell walls. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simeone, M.L.F.; Oliveira, P.A.d.; Canuto, K.M.; Parrella, R.A.C.; Damasceno, C.M.B.; Schaffert, R.E. Caracterização de Genótipos de Sorgo Doce Para Produção de Bioetanol; Technical Document; Embrapa Agroenergia: Brasília, Brazil, 2016; Available online: https://www.alice.cnptia.embrapa.br/alice/bitstream/doc/1109526/1/Caracterizacaogenotipos.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Hu, J.; Arantes, V.; Saddler, J.N. The enhancement of enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic substrates by the addition of accessory enzymes such as xylanase: Is it an additive or synergistic effect? Biotechnol. Biofuels 2011, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Jurado, M.; López-González, J.; Estrella-González, M.; Martínez-Gallardo, M.; Toribio, A.; Suárez-Estrella, F. Characterization of thermophilic lignocellulolytic microorganisms in composting. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 697480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, M.; Fiedler, H.-P. A guide to successful bioprospecting: Informed by actinobacterial systematics. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2010, 98, 119–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, G.R.; Carlos, C.; Chevrette, M.G.; Horn, H.A.; McDonald, B.R.; Stankey, R.J.; Fox, B.G.; Currie, C.R. Evolution and ecology of Actinobacteria and their bioenergy applications. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 70, 235–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskay, M.; Üsame, A.; Cem, A. Antibacterial activity of some actinomycetes isolated from farming soils of Turkey. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2004, 3, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, A.J.; Williams, S.T. Actinomycetes as agents of biodegradation in the environment a review. Gene 1992, 115, 189–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalak, T. Potential use of industrial biomass waste as a sustainable energy source in the future. Energies 2023, 16, 1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Hyman, D.; Payne, C.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Wolfe, J. Determination of total solids in biomass and total dissolved solids in liquid process samples. Natl. Renew. Energy Lab. 2008, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, A.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.J. Determination of extractives in biomass. Lab. Anal. Proced. (LAP) 2005, 1617, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; Crocker, D.L. Determination of structural carbohydrates and lignin in biomass. Lab. Anal. Proced. 2008, 1617, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dornelas, J.C.M.; Figueiredo, J.E.F.; de Abreu, C.S.; Lana, U.G.P.; Oliveira-Paiva, C.A.; Marriel, I.E. Characterization and phylogenetic affiliation of Actinobacteria from tropical soils with potential uses for agro-industrial processes. Genet. Mol. Res. 2017, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AleloMicro Consultas. Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária (Embrapa); Seção “Linhagem”. 2021. Available online: https://am.cenargen.embrapa.br/amconsulta/linhagem?id=72141 (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Lopes, F.; Motta, F.; Andrade, C.C.P.; Rodrigues, M.I.; Maugeri-Filho, F. Thermo-stable xylanases from non conventional yeasts. J. Microbiol. Biochem. Technol. 2011, 3, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teather, R.M.; Wood, P.J. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1982, 43, 777–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Kapoor, V.; Kumar, V. Utilization of agro-industrial wastes for the simultaneous production of amylase and xylanase by thermophilic actinomycetes. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2012, 43, 1545–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. A: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 31 December 2025).

- Omar, S.M.; Norsyafawati, M.F.; Nurfathiah, A.M.; Zaima, A.Z. Verrucosispora sp. K2-04, potential xylanase producer from Kuantan Mangrove Forest sediment. Int. J. Food Eng. 2017, 13, 20160187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjivkumar, M.; Silambarasan, T.; Palavesam, A.; Immanuel, G. Biosynthesis, purification and characterization of β-1,4-xylanase from a novel mangrove associated actinobacterium Streptomyces olivaceus (MSU3) and its applications. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 130, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flärdh, K.; Buttner, M.J. Streptomyces morphogenetics: Dissecting differentiation in a filamentous bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H.-C.; Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, M.; Kuru, A.; Isikli, M.; Sahin, N.; Celenk, F.G. Optimization of extracellular endoxylanase, endoglucanase and peroxidase production by Streptomyces sp. F2621 isolated in Turkey. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 97, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, R.P.; Coelho, R.R.R.; Marques, S.; Alves, L.; Gírio, F.M.; Bon, E.P.S.; Amaral-Collaço, M.T. Production and partial characterisation of xylanase from Streptomyces sp. strain AMT-3 isolated from Brazilian cerrado soil. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2002, 31, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsuk, I.; Özakın, S.; Bali, B.; Yilmaz, E.I. A cellulase-free, thermoactive, and alkali xylanase production by terrestrial Streptomyces sp. CA24. Turk. J. Biol. 2013, 37, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Techapun, C.; Sinsuwongwat, S.; Watanabe, M.; Sasaki, K.; Poosaran, N. Production of cellulase-free xylanase by a thermotolerant Streptomyces sp. grown on agricultural waste and media optimization using mixture design and Plackett–Burman experimental design methods. Biotechnol. Lett. 2002, 24, 1437–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, G.C.; Choi, Y.H.; Choi, Y.S.; Seong, C.N.; Cho, S.S.; Lee, H.J.; Yoo, J.C. A novel thermostable cellulase-free xylanase stable in broad range of pH from Streptomyces sp. CS428. Process Biochem. 2013, 48, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, J.; Vaez Fakhri, A.; Mahdavi, S. Biobleaching of mechanical paper pulp using Streptomyces rutgersensis UTMC 2445 isolated from a lignocellulose-rich soil. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chater, K.F. Recent advances in understanding Streptomyces. F1000Research 2016, 5, 1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantzeskakis, L.; Di Pietro, A.; Rep, M.; Schirawski, J.; Wu, C.-H.; Panstruga, R. Rapid evolution in plant–microbe interactions: A molecular genomics perspective. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sruthi, N.; Rao, P.; Bennett, S.; Bhattarai, R. Formulation of a synergistic enzyme cocktail for controlled degradation of sorghum grain pericarp. Foods 2023, 12, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, Y.; Dolfing, J.; Guo, Z.; Chen, R.; Wu, M.; Li, Z.; Feng, Y. Important ecophysiological roles of non-dominant Actinobacteria in plant residue decomposition, especially in less fertile soils. Microbiome 2021, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, M.; Wang, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, J.; Yang, N.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, W. Pretreatment of sweet sorghum straw and its enzymatic digestion: Insight into the structural changes and visualization of hydrolysis process. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2019, 12, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tom, L.M.; Aulitto, M.; Wu, Y.W.; Deng, K.; Gao, Y.; Xiao, N.; Rodriguez, B.G.; Louime, C.; Northen, T.R.; Eudes, A.; et al. Low-abundance populations distinguish microbiome performance in plant cell wall deconstruction. Microbiome 2022, 10, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravichandra, K.; Balaji, R.; Devarapalli, K.; Cheemalamarri, C.; Poda, S.; Banoth, L.; Pinnamaneni, S.R.; Prakasham, R.S. Impact of structure and composition of different sorghum xylans as substrates on production of xylanase enzyme by Aspergillus fumigatus RSP-8. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 188, 115660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhyaru, D.N.; Bhatt, N.S.; Modi, H.A. Enhanced production of cellulase-free, thermo-alkali-solvent-stable xylanase from Bacillus altitudinis DHN8, its characterization and application in sorghum straw saccharification. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2014, 3, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, L.M. Produção de Celulases e Hemicelulases por Aspergillus fumigatus e A. niger Utilizando Sorgo Biomassa como Principal Fonte de Carbono. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Uberlândia, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, B.; Ali, S.S.; Xie, R.; Sun, J. Valorisation of wheat straw and bioethanol production by a novel xylanase- and cellulase-producing Streptomyces strain isolated from the wood-feeding termite, Microcerotermes species. Fuel 2022, 310, 122333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.