Abstract

Salmonella enterica from low-moisture food has been found to have a higher thermal tolerance than from high-moisture food. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the association of thermal tolerance of this pathogen with low-moisture foods, such as peanut butter and peanut spread, has not been fully elucidated. We previously found that mutants of S. Tennessee with a defective gene encoding a cell membrane lipoprotein (Lpa) or cell division protein (ZapC) formed significantly (p ≤ 0.05) less biofilm than the wildtype strain. To assess the possible role of these genes in the thermal tolerance of S. Tennessee, this study compared the surviving populations of the wildtype S. Tennessee and its mutants defective in Lpa or ZapC in different types of peanut products (regular, reduced-fat, and natural) at 74 °C for 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, or 50 min. Results showed that mutants with a defective lpa or zapC significantly affected the survival of Salmonella in peanut products during heat treatments. Significantly, a higher reduction in Salmonella population was observed in regular peanut butter, followed by natural and reduced-fat peanut spreads. The study provides new insight into one of the molecular mechanisms underlying the thermal tolerance of Salmonella enterica.

1. Introduction

Low-moisture foods have been recognized as a novel vehicle for transmitting foodborne pathogens in recent years [1]. Low-moisture conditions, in general, do not support the growth of foodborne bacterial pathogens. However, cells of some pathogens, like Salmonella, could survive in low-moisture foods during long-term storage. These pathogens have been found to have enhanced tolerance to heat treatment compared to those from high-moisture environments (aw > 0.9) [2,3,4,5]. Peanut butter, one of the low-moisture foods, was first linked to an outbreak of salmonellosis in 2007 [6]. Since then, outbreaks of Salmonella infection associated with peanut product consumption occurred again in 2008, 2009, and 2022 [7].

Commercial peanut butter production involves several key steps including roasting, blanching, and grinding, followed by tempering, cooling, and packaging [8,9,10]. After roasted peanuts are ground and milled to peanut paste, additional ingredients such as salt, sugar, and stabilizers are added [11]. To homogenize and prevent the peanut butter from separating, stabilizers are added at a temperature higher than their melting points, ranging from 60 to 74 °C [10]. The grinding process raises the peanut butter temperatures to 71–77 °C for approximately 20 min [4]. These temperatures might not be sufficient to eliminate pathogens like Salmonella due to the thermal tolerance of pathogen cells [4,12,13,14].

Both intrinsic (strain variability, cell surface structure, and biofilm-forming ability) and extrinsic factors (food composition and water activity) could impact the thermal tolerance of Salmonella in low-moisture foods. Peanut butter is a concentrated colloidal suspension of lipids and water, which may impact Salmonella survival during heat treatment. Other food components, such as glycerol, and sucrose, are also among factors affecting Salmonella heat tolerance [15,16,17,18].

The ability of Salmonella to survive thermal treatment is associated with the expression of certain genes. For example, the expression of rpoS, encoding for sigma factor RpoS, and fimbria genes were upregulated in S. Typhimurium after exposure to mild heat treatment at 42 °C [19]. According to Gruzdev et al. [20], subjecting S. Typhimurium to desiccation stress induced the expression of heat shock proteins DnaK, GroEL, and IbpA. These proteins act as chaperones to stabilize cellular proteins, preventing protein denaturation during heat treatment [20].

Other than molecular regulation, another intrinsic factor, cells’ ability to form biofilms, could reduce heat conductivity, protect cells from thermal stress, and enhance bacterial tolerance to heat treatment. Mutant Escherichia coli deficient in the expression of colanic acid, one of the essential bacterial extracellular structures involved in biofilm formation, had increased susceptibility to heat treatment [21]. Biofilm-forming S. Enteritidis strains were found to be significantly more tolerant of heat treatment than the non-biofilm-forming strains in wheat flour [22]. Furthermore, cells embedded in biofilms had enhanced heat tolerance compared to planktonic cells [23].

In a previous study, we acquired several knock-off mutants from wildtype S. Tennessee, the peanut butter outbreak strain [24]. Two of the mutants had a defective gene encoding for a bacterial cell membrane lipoprotein or cell division protein. The mutants were found to accumulate significantly (p ≤ 0.05) less biofilm mass on polystyrene tissue culture plates compared to their wildtype parent [24]. However, there is scarce information on the relationship between these biofilm-formation-associated genes and Salmonella survival during thermal treatment. The goal of this study was to evaluate whether the two knock-off mutants obtained from our previous study had a differential heat tolerance compared to their wildtype parent in peanut butter and peanut spread at 74 °C for various lengths of time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Salmonella Culture and Growth Conditions

Bacterial isolates used in this study are listed in Table 1. Salmonella enterica serovar Tennessee from the 2017 peanut butter outbreak was the wildtype parent strain. S. Tennessee mutants used in the study included L7 and S32, and, as described previously, each mutant had a defective gene that encodes for a bacterial cell membrane lipoprotein or cell division protein [24]. The wildtype strain was grown in Luria Bertani with no salt (LBNS; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA), whereas the mutants were grown in the same broth supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/mL) and nalidixic acid (30 μg/mL) at 25 °C for 48 h. Each culture was transferred to fresh broth at two consecutive 48 h intervals. The antibiotics used in this study were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Ward Hill, MA, USA).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in the study.

2.2. Peanut Products

Commercially available regular peanut butter, reduced-fat peanut spread, and natural peanut spread were purchased from a retail supermarket (Walmart, Bentonville, AR, USA). The nutrient profiles of peanut butter and peanut spreads used in the current project are shown in Table 2. According to the Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, peanut butter must contain at least 90% peanuts and less than 55% fat, and additional ingredients, such as seasoning and hydrogenated oil stabilizer, can be added [25]. The peanut product that does not conform to the standard identity for peanut butter is recognized as “peanut spread” [26]. All three products had a water activity of 0.35.

Table 2.

Nutrient profile of peanut butter (regular) and peanut spreads (reduced-fat, natural).

2.3. Inoculation of Peanut Products with Salmonella

Wildtype S. Tennessee and its mutants (L7 and S32) were freeze-dried as described previously [27]. Briefly, cell cultures grown in LBNS broth with or without the antibiotics at 37 °C for 24 h were centrifuged at 5000× g for 5 min. The pelleted cells were re-suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and spun down under the same conditions. The resulting pellets were re-suspended in 10% sterile skim milk (Walmart, Bentonville, AR, USA). The cell suspensions were distributed into sterilized 10 mL glass tubes (Fisher Scientific, Asheville, NC, USA) and placed in a freezer at −20 °C for 24 h. The frozen samples were placed in a Free Zone Benchtop Freeze Dry System (Labconco, Kansas City, MO, USA) for lyophilization, at a condenser temperature of −40 °C and a chamber pressure of <0.05 mbar, overnight. The lyophilized cultures were stored at −20 °C until use.

The peanut butter and peanut spreads were pre-heated at 37 °C for 3 h before inoculation to reduce product viscosity and enhance uniform mixing. Precisely, 150 g of each peanut product was placed into a sterilized 250 mL glass beaker, and a pre-determined amount of each freeze-dried S. Tennessee culture was added to the product to achieve a 6-log CFU/g inoculation level. The peanut product and Salmonella culture were mixed using a KitchenAid® hand mixer at room temperature for 10 min. Inoculated peanut products (5 g per sample) were placed into a sterilized aluminum foil bag (2.8 × 5.1 inch, EONJOE/Amazon). The sample bags containing the peanut products were flattened into a thin layer and sealed using a Foodsaver® heat sealer (Food Saver, Boca Raton, FL, USA).

2.4. Heat Treatment

The three peanut products described above were inoculated with wildtype S. Tennessee, mutant L7, or S32 with a targeted inoculation level of 6 log CFU/g. This level of inoculation allowed us to observe the heat inactivation differences between different bacterial inocula. The inoculated products were submerged in a water bath (Precision Scientific Group, Chicago, IL, USA) at 74 °C. Samples were collected after the samples were heated for 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, or 50 min. The heating temperatures were monitored using the SL4TH-A Button Temperature and Relative Humidity logger (Signatrol Ltd., Gloucestershire, UK). After the heat treatments, the samples were removed from the water bath, drained for 2 s, and placed in an ice bucket to lower the temperature of the samples. Ten ml of PBS was added to each bag to achieve a 2-fold dilution. The samples were then mixed vigorously by pummeling in a stomacher at high speed for 2 min. The suspensions were serially diluted in 9 mL PBS, surface plated on bismuth sulfite agar (BSA; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA), and TSA supplemented with or without the antibiotics. The reduction in the population of Salmonella (logNt/N0) in various samples was documented, where Nt and N0 are the Salmonella cell counts (log CFU/g) at treatment time t and 0, respectively.

2.5. Data Analysis

All experiments were replicated in two independent experiments, with duplicates of each sample included. The significant difference in cell population reduction between the wildtype Salmonella and its mutants in peanut products during the heat treatment was analyzed using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference test (SAS, Institute, Version 9.4, Cary, NC, USA). The population reduction in Salmonella cells as affected by different treatment times was also analyzed using the same test. The significant difference was determined at a 95% confidence interval.

3. Results

Table 3 shows the mean cell population reduction in the wildtype and mutant Salmonella recovered from different sampling points or peanut products. On average, Salmonella cells in the reduced-fat peanut product had the highest tolerance to the heat treatment, followed by the natural and regular types of products, as the mean cell population reductions were 1.41, 1.69, and 1.83 log CFU/g in the reduced-fat peanut butter, natural, and regular products, respectively. Overall, the population of Salmonella decreased as heating time increased. The mean reduction in the population of wildtype (1.43 log CFU/g) was significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower than the population reductions in L7 and S32 (1.80 and 1.70 log CFU/g) on TSA. L7 had a significantly higher population reduction compared to S32 according to the enumeration results from TSA, but the population reductions in the two mutants from BSA were insignificantly (p > 0.05) different.

Table 3.

Average cell population reduction in Salmonella cultures in different peanut products after being heated at 74 °C for various lengths of time.

The mean reductions in each Salmonella culture in individual types of peanut product from all sampling intervals are shown in Table 4. On TSA, all three tested cultures had significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher population reduction in the regular peanut butter and natural peanut spread than the reduced-fat peanut spread, except for S32 which had a significantly higher population reduction in the reduced-fat peanut spread than the natural peanut spread. The mean reductions in the population of L7 and S32 were insignificantly (p > 0.05) different in the regular peanut butter and reduced-fat peanut spread when cells in these samples were enumerated on TSA, and these reductions were significantly higher than the population reduction in the wildtype. In natural peanut spread, L7 had a significantly higher population reduction than S32, and both mutants had a significantly higher population reduction than the wildtype. Similarly, when cells were enumerated on BSA, L7 and S32 had a significantly higher population reduction than the wildtype in all types of peanut products except for S32 in the natural peanut spread.

Table 4.

Mean population reductions in peanut products inoculated with individual Salmonella cultures from all sampling intervals.

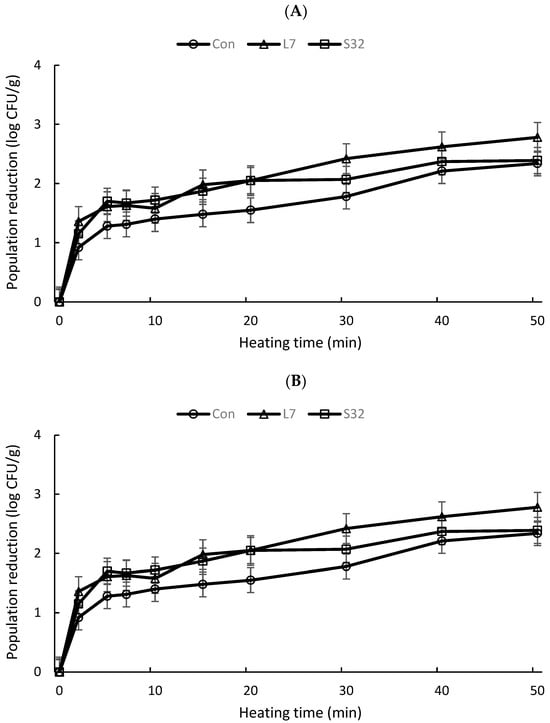

Detailed changes in the population reduction in each culture inoculated in different types of peanut products at various sampling times on TSA and BSA are shown in Figure 1A and Figure 1B, respectively. The population of Salmonella cells sharply decreased at the beginning of the heating process (2.5 min), followed by a slower reduction pace with an asymptomatic tail. When cells were enumerated on TSA, mutants L7 and S32 consistently had higher population reductions than the wildtype at every sampling time until the end of the 40 min treatment (Figure 1A). Reductions in the population of L7, S32, and the wildtype from TSA were 1.36, 1.15, and 0.92 log CFU/g, respectively, at the 2.5 min sampling point, and the population reductions continuously increased up to 2.78, 2.39, and 2.34 log CFU/g at the 50 min sampling point. On BSA similarly, mutant strains were consistently more sensitive to the heat treatments compared to the wildtype during the 50 min of treatment (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Mean cell population reductions in all three peanut products inoculated with each Salmonella culture at different sampling points. (B) Mean Salmonella population reductions in all three peanut products at different sampling points.

4. Discussion

It was found in the current study that L7 and S32 had significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher population declines compared to the wildtype when exposed to heat treatment at 74 °C for 50 min (Table 4). Since L7 and S32 carried a defective gene for a cell membrane lipoprotein or cell division protein, these results revealed an association between the two proteins with biofilm formation, as shown in our previous study [24], but also with Salmonella survival under heat treatment in low-moisture food like peanut butter and peanut spreads.

Bacterial lipoproteins are crucial cell membrane proteins anchored to either the inner or outer membrane [28] and have been shown to have a myriad of physiological roles, including cell membrane maintenance, nutrient uptake, cell adhesion, conjugation, and antibiotic resistance [29,30]. Thus, the correct localization of lipoproteins is essential to maintain cell membrane integrity and bacterial pathogenicity. The localization of most bacterial lipoproteins is mediated by the lipoprotein outer membrane localization (Lol) pathway [31]. Mutation of lolB in Xanthomonas campestris has been shown to result in damage to cell membrane integrity and enhanced heat sensitivity compared to the wildtype [32].

The cell division process is one of the fundamental processes for bacterial proliferation [33]. ZapC, a cell division-related protein, is responsible for the stabilization of the Z-ring structure, an essential apparatus for the development of the septum [34]. A mutation at ZapC of E. coli resulted in Z-ring mislocalization and alteration of cell morphology, leading to the formation of elongated and filamentous cells [35,36]. Furthermore, a defective LocZ in Streptococcus pneumoniae caused misplacement of the Z-ring structure and cell morphology deformation, leading to asymmetric cell division and the generation of unequally sized daughter cells [11]. The LocZ mutant had been shown to have significantly lower growth than the wildtype at elevated temperature (40 °C) compared to the growth at optimal temperature (37 °C). However, whether elongated or unequally sized, daughter cells of S. Tennessee had different heat tolerance than normal cells, which calls for further investigation. It is worth noting that these cited mechanisms are inferred rather than confirmed in S. Tennessee.

We found that the population reduction curves demonstrated an increasing downward concave as heating time increased, meaning that Salmonella cells reduced rapidly at the beginning of the heating process (2.5 min), followed by a slower reduction rate thereafter (Figure 1). The shape of the thermal inactivation curve could be affected by bacterial strain and the food matrix involved, as well as the condition of thermal treatment [37]. A similar shape of thermal inactivation curve was observed when Salmonella cells in peanut butter were heated at 70 to 90 °C for up to 50 min [4,13,14]. The rapid decline followed by a slow reduction in population could be partially attributed to cell variability in heat sensitivity within a population and bacterial adaptation to heat treatment at a later stage of the heating process. Shachar and Yaron [14] described that the heterogeneous nature of the peanut butter matrix could have been attributed to the decreased heat sensitivity over time by exposing cells to different local environments. In our study, when peanut butter was inoculated with wildtype strain and heated at 74 °C, a 1.3-log reduction was observed during the first 5 min (Figure 1A), which is comparable to the observation of a previous study where a reduction of 1.4 log CFU/g was reported when peanut butter inoculated with Salmonella cells was heated at 70 °C [14]. The 4 °C difference in heating temperature between the two studies did not result in significant differences in the reported results.

In the current study, we observed that Salmonella cells were most resistant to heat in reduced-fat peanut spread, followed by natural peanut spread and regular peanut butter (Table 4). Consistent with several previous studies [13,14,16], the results suggest that the composition of peanut butter could be an important factor influencing the heat resistance of Salmonella. Shachar and Yaron [14] and Li et al. [13] found that low moisture and low fat content of peanut products provided a protective effect on Salmonella from heat stress. The two main factors of peanut products, high fat and low moisture, are known to contribute to the endurance of Salmonella cells to heat treatment, but the observed high tolerance to heat by Salmonella in reduced-fat peanut spread suggests that fat content is not the only factor affecting bacterial heat resistance. Reduced-fat peanut spread contains a relatively higher amount of carbohydrates (5% daily value) than the other products (3% daily value) used in the study. A similar observation was made previously: Salmonella survival in high-carbohydrate peanut butter was enhanced compared to the low-carbohydrate peanut butter [13,14]. Li et al. [13] suggested that carbohydrates including simple sugar may protect Salmonella cells from dehydration, thus elevating the heat resistance of the pathogen. In addition, we observed that Salmonella survival during heat treatment was also higher in the natural peanut spread, which has a lower sodium content, than the regular peanut butter. He et al. [15] reported that the population reduction in Salmonella in peanut butter with 0.25% salt was greater than in peanut butter without salt. However, this observation is generally in disagreement with another study reporting that sodium chloride in the medium has a protective effect for Salmonella [38]. Different compositions in peanut butter may have synergistic or antagonistic effects affecting the thermal tolerance of Salmonella. Additional studies are needed to verify the finding of the current study, that the thermal resistance of Salmonella is enhanced if a peanut product is low in fat, high in carbohydrates, or low in sodium.

5. Conclusions

Low-moisture environment tends to make bacterial cells more persistent to various environmental stressors including thermal treatment. Cells that survived thermal treatments may survive in shelf stable food for an extended period of time, jeopardizing consumer safety. The current study used two knock-off mutants, L7 and S32, with defective genes that have previously been shown to have a critical role in biofilm formation, to elucidate the mechanism of thermal resistance of S. Tennessee in peanut products. The study observed that the thermal resistance of L7 and S32, with a defective gene encoding for lipoprotein or cell division protein, exhibited significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower thermal resistance compared to the wildtype in peanut butter and peanut spreads. The thermal resistance of Salmonella in the peanut products was affected by heating time and product composition. The population reduction in Salmonella in the reduced-fat peanut spread was significantly lower than in the natural peanut spread and regular peanut butter. However, future study is called for to verify the impact of product composition on bacterial thermal tolerance. But the current observation emphasizes that biofilm-associated proteins are a resistance factor employed by bacteria to maintain cell membrane integrity and cell morphology during heat stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.C. and F.K.; methodology, S.L. and J.C.; formal analysis, S.L. and J.C.; data curation, S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, J.C. and F.K.; project administration, J.C.; funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2014-67017-21705.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank USDA NIFA for making the study possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Acuff, J.; Dickson, J.S.; Farber, J.M.; Grasso-Kelley, E.M.; Hedberg, C.; Lee, A.; Zhu, M.-J. Practice and progress: Updates on outbreaks, advances in research, and processing technologies for low-moisture food safety. J. Food Prot. 2023, 86, 100018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, S.L.; Gehm, E.R.; Weissinger, W.R.; Beuchat, L.R. Survival of Salmonella in peanut butter and peanut butter spread. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 89, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, S.; Condell, O.; McClure, P.; Amézquita, A.; Fanning, S. Mechanisms of survival, responses and sources of Salmonella in low-moisture environments. Front. Microbiol. 2013, 4, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, G.; Gerner-Smidt, P.; Mantripragada, V.; Ezeoke, I.; Doyle, M.P. Thermal Inactivation of Salmonella in peanut butter. J. Food Prot. 2009, 72, 1596–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podolak, R.; Enache, E.; Stone, W.; Black, D.G.; Elliott, P.H. Sources and risk factors for contamination, survival, persistence, and heat resistance of Salmonella in low-moisture foods. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 1919–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, A.N.; Hoekstra, M.; Patel, N.; Ewald, G.; Lord, C.; Clarke, C.; Villamil, E.; Niksich, K.; Bopp, C.; Nguyen, T.-A.; et al. A national outbreak of Salmonella serotype Tennessee infections from contaminated peanut butter: A new food vehicle for salmonellosis in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. FDA. Outbreak Investigation of Salmonella: Peanut Butter (May 2022). 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/outbreaks-foodborne-illness/outbreak-investigation-salmonella-peanut-butter-may-2022#:~:text=of%20new%20recalls.-,As%20of%20May%2025%2C%202022%2C%20CDC%20reports%20that%20of%20the,illnesses%20in%20this%20current%20outbreak (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Hvizdzak, A.L.; Beamer, S.; Jaczynski, J.; Matak, K.E. Use of electron beam radiation for the reduction of Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium and Tennessee in peanut butter. J. Food Prot. 2010, 73, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kataoka, A.; Enache, E.; Black, D.G.; Elliott, P.H.; Napier, C.D.; Podolak, R.; Hayman, M.M. Survival of Salmonella Tennessee, Salmonella Typhimurium DT104, and Enterococcus faecium in peanut paste formulations at two different levels of water activity and fat. J. Food Prot. 2014, 77, 1252–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorrepati, K.; Balasubramanian, S.; Chandra, P. Plant based butters. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 3965–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holečková, N.; Doubravová, L.; Massidda, O.; Molle, V.; Buriánková, K.; Benada, O.; Kofroňová, O.; Ulrych, A.; Branny, P. LocZ Is a new cell division protein involved in proper septum placement in Streptococcus pneumoniae. mBio 2015, 6, e01700-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections associated with peanut butter and peanut butter-containing products—United States, 2008–2009. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2009, 58, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Huang, L.; Chen, J. Comparative study of thermal inactivation kinetics of Salmonella spp. in peanut butter and peanut butter spread. Food Control 2014, 45, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shachar, D.; Yaron, S. Heat tolerance of Salmonella enterica serovars Agona, Enteritidis, and Typhimurium in peanut butter. J. Food Prot. 2006, 69, 2687–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Li, Y.; Salazar, J.K.; Yang, J.; Tortorello, M.L.; Zhang, W. Increased water activity reduces the thermal resistance of Salmonella enterica in peanut butter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 4763–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Guo, D.; Yang, J.; Tortorello, M.L.; Zhang, W. Survival and heat resistance of Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in peanut butter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8434–8438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, V.K.; Eblen, B.S. Heat inactivation of Salmonella typhimurium DT104 in beef as affected by fat content. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 30, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lock, J.L.; Board, R.G. The fate of Salmonella enteritidis PT4 in deliberately infected commercial mayonnaise. Food Microbiol. 1994, 11, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirsat, S.A.; Burkholder, K.M.; Muthaiyan, A.; Dowd, S.E.; Bhunia, A.K.; Ricke, S.C. Effect of sublethal heat stress on Salmonella Typhimurium virulence. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2011, 110, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruzdev, N.; Pinto, R.; Sela, S. Effect of desiccation on tolerance of Salmonella enterica to multiple stresses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Doyle, M.P.; Chen, J. Insertion mutagenesis of wca reduces acid and heat tolerance of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 3811–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Rojas, R.; Zhu, M.-J.; Paul, N.C.; Gray, P.; Xu, J.; Shah, D.H.; Tang, J. Biofilm forming Salmonella strains exhibit enhanced thermal resistance in wheat flour. Food Control 2017, 73, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, V.K.; Dodd, C.E. Susceptibility of suspended and surface-attached Salmonella enteritidis to biocides and elevated temperatures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 1731–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Chen, J. Identification of the genetic elements involved in biofilm formation by Salmonella enterica serovar Tennessee using mini-Tn10 mutagenesis and DNA sequencing. Food Microbiol. 2022, 106, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. FDA. Food Standard Innovations: Peanut Butter’s Sticky Standard. 2022. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/histories-product-regulation/food-standard-innovations-peanut-butters-sticky-standard#:~:text=FDA%20proposed%20a%20standard%20for,did%20prevail%20as%20the%20US (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Code of Federal Regulation. Part 102—Common or Usual Name for Nonstandaridized Foods. 2025. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-102 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Cui, Y.; Liu, D.; Chen, J. Fate of Salmonella enterica and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli on vegetable seeds contaminated by direct contact with artificially inoculated soil during germination. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 1218–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, H.; Kurokawa, K.; Lee, B.L. Lipoproteins in bacteria: Structures and biosynthetic pathways. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 4247–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Hantke, K. Lipoproteins: Structure, Function, Biosynthesis. In Bacterial Cell Walls and Membranes, Subcellular Biochemistry; Kuhn, A., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 39–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs-Simon, A.; Titball, R.W.; Michell, S.L. Lipoproteins of bacterial pathogens. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 548–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, S.; Matsuyama, S.; Tokuda, H. Lipoprotein trafficking in Escherichia coli. Arch. Microbiol. 2004, 182, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.-T.; Li, C.-E.; Chang, H.-C.; Hsu, C.-H.; Chiang, Y.-C.; Hsiao, Y.-M. The lolB gene in Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris is required for bacterial attachment, stress tolerance, and virulence. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedyaykin, A.D.; Ponomareva, E.V.; Khodorkovskii, M.A.; Borchsenius, S.N.; Vishnyakov, I.E. Mechanisms of bacterial cell division. Microbiology 2019, 88, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand-Heredia, J.M.; Yu, H.H.; De Carlo, S.; Lesser, C.F.; Janakiraman, A. Identification and characterization of ZapC, a stabilizer of the FtsZ ring in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A.; Ray, S.; Singh, D.; Dhaked, H.P.S.; Panda, D. ZapC promotes assembly and stability of FtsZ filaments by binding at a different site on FtsZ than ZipA. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, C.A.; Shiomi, D.; Liu, B.; Bernhardt, T.G.; Margolin, W.; Niki, H.; de Boer, P.A.J. Identification of Escherichia coli ZapC (YcbW) as a component of the division apparatus that binds and bundles FtsZ polymers. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 1393–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, A.A.M.; Prestes, F.S.; Silva, A.C.M.; Nascimento, M.S. Evaluation of the thermal resistance of Salmonella Typhimurium ATCC 14028 after long-term blanched peanut kernel storage. LWT 2020, 117, 108701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mañas, P.; Pagan, R.; Leguérinel, I.; Condon, S.; Mafart, P.; Sala, F. Effect of sodium chloride concentration on the heat resistance and recovery of Salmonella typhimurium. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2001, 15, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.