Abstract

Although the combination of solar power and electric vehicles is widely considered beneficial, practical applications reveal substantial variance. To determine the proportion of solar energy used for charging and to identify the main drivers of a high solar share, a dataset containing measured 5 min energy time series of 725 households with PV and EVs was analyzed. In the existing literature, this represents a novelty, as most studies in this field are simulation-based, rely on synthetic profiles, use lower time resolutions, or are based on questionnaires. The share of solar energy used for EV charging is highly dispersed and varies by about ±40% around a median of 60%. The analysis shows that clustering by preferred charging times has strong explanatory potential: at the median, EVs charged predominantly during the daytime achieve a solar share that is more than 40% higher than those charged in the evening. In the latter case, home battery storage increases the solar share by an average of 20 percentage points. A similar magnitude of a 25-percentage-point increase could be reached with solar surplus charging compared to uncontrolled charging. On average, households with PV, battery, and EVs cover more than 56% of their total demand with self-generated solar energy; with solar-adapted charging, median values exceed 77%. If a heat pump is used on site, the self-sufficiency decreases but can still reach median values above 45% and up to 61% for optimized households.

1. Introduction

Solar power (PV) and electric vehicles (EVs) are key elements of a fossil-free energy transition [1]. Combining PV systems with EVs is particularly attractive for residential consumers, as self-generated solar electricity is more cost-effective than grid supply. Surveys confirm that home charging is the dominant mode of EV charging in Germany, with more than 75% of the total charging volume occurring through private chargers [2]. Owners of PV systems increasingly invest in EVs to utilize surplus energy, while EV users show growing interest in PV adoption [3]. In Germany, about 16% of PV households also operate an EV [4,5], compared to only 3% of the general population [6]. This dominance, combined with the increasing use of PV systems for self-consumption, highlights the relevance of analyzing solar–EV households in detail. While environmental motivations play a role, economic considerations are becoming the dominant driver, as highlighted in several case studies (e.g., [7,8,9,10]).

Martin et al. [7] analyzed the effect of different smart charging strategies to cover the individual demand of EVs in Switzerland. The authors based their findings on a relatively small sample of 78 charging behaviors recorded among above-average wealthy individuals. Moreover, the households were only simulatively equipped with a PV system. The low temporal resolution of the simulated PV output of 30 min resulted in limited representativeness of the determined solar share of the EV charge. The works of Fachrizal et al. [8] and Kern et al. [9] used synthetic datasets or small datasets with just 20 households. Furthermore, they primarily addressed the grid impacts of EV charging, self-sufficiency, or V2G revenue streams rather than real-world charging behavior. The results of survey-based studies (e.g., USCALE [10] and NOW [2]) are usually limited to averages or ranges. In-depth analyses are rarely possible, and input parameters for system modeling are lacking.

From a grid perspective, the available database is broader but remains limited in contextualization. Previous studies have used smart-meter data to analyze aggregated residential EV charging behavior [11], rather than household-level datasets. More recent work has addressed uncertainty in EV and PV integration using statistically modeled datasets [12], and large datasets of charging behavior at public stations have been published [13]. The literature analysis shows that comprehensive statistical analyses of residential EV-PV households, capable of simultaneously addressing economic and grid-related questions, are still especially lacking. An in-depth analysis of high-resolution data based on real measurements from several hundred households has not yet been published in the literature.

To address this gap, this paper presents high-resolution monitoring data from more than 3800 households using charging EVs paired with PV systems in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, with data from 2022 and 2023. The dataset enables the first statistically robust assessment of how mobility patterns, PV sizing, battery storage, and solar smart charging shape the energetic and economic performance of mass-market EV-PV households. Furthermore, for the first time, the self-sufficiency levels of several hundred fully electrified households that have not been determined using simulation are presented. By providing empirical evidence, this work bridges the gap between conceptual studies and practical applications in the “D-A-CH region”.

The application of this is wide-ranged: houseowners could easily look to reliable results and adapt their behavior according to the findings. Installers and energy experts could use the data for simulation studies and, furthermore, validate their results based on the findings of these measurement data, thus achieving more realistic results. Lastly, the dataset is promising for policy and decision makers, as it show actual charging behavior in PV-EV-systems, which they could consider in funding and/or regulatory frameworks.

A preliminary version of this study was presented at EVS38 in Gothenburg, Sweden [14]. In parallel, the same database was used for a German study on solar charging [15] linked in the Supplementary Material. The manuscript has since been expanded, refined, and contextualized in the present version.

2. Materials and Methods

This section provides an overview of the dataset. Section 2.1 describes the raw data, while Section 2.2 outlines the preparation steps. In addition to data curation, enhanced metadata were derived through calculation procedures, as well as key performance indicators, including the solar share of electric vehicle charging and the household degree of self-sufficiency. These metrics form the basis for subsequent evaluation of system behavior and energy flows.

2.1. Monitoring Data—Basic Description

The data analyzed were provided by Fronius International, an Austrian solar system integrator. The company offers all system components, from the inverter to the EV charger and the energy meter. To ensure appropriate operation of its system to customers, Fronius collects energy-related data through a web-monitoring portal. The portal provides transparency on operational functions, showing energy consumption types and solar energy shares. In addition, power flows and time series data on load, EV charging, and generation are displayed at 5 min intervals.

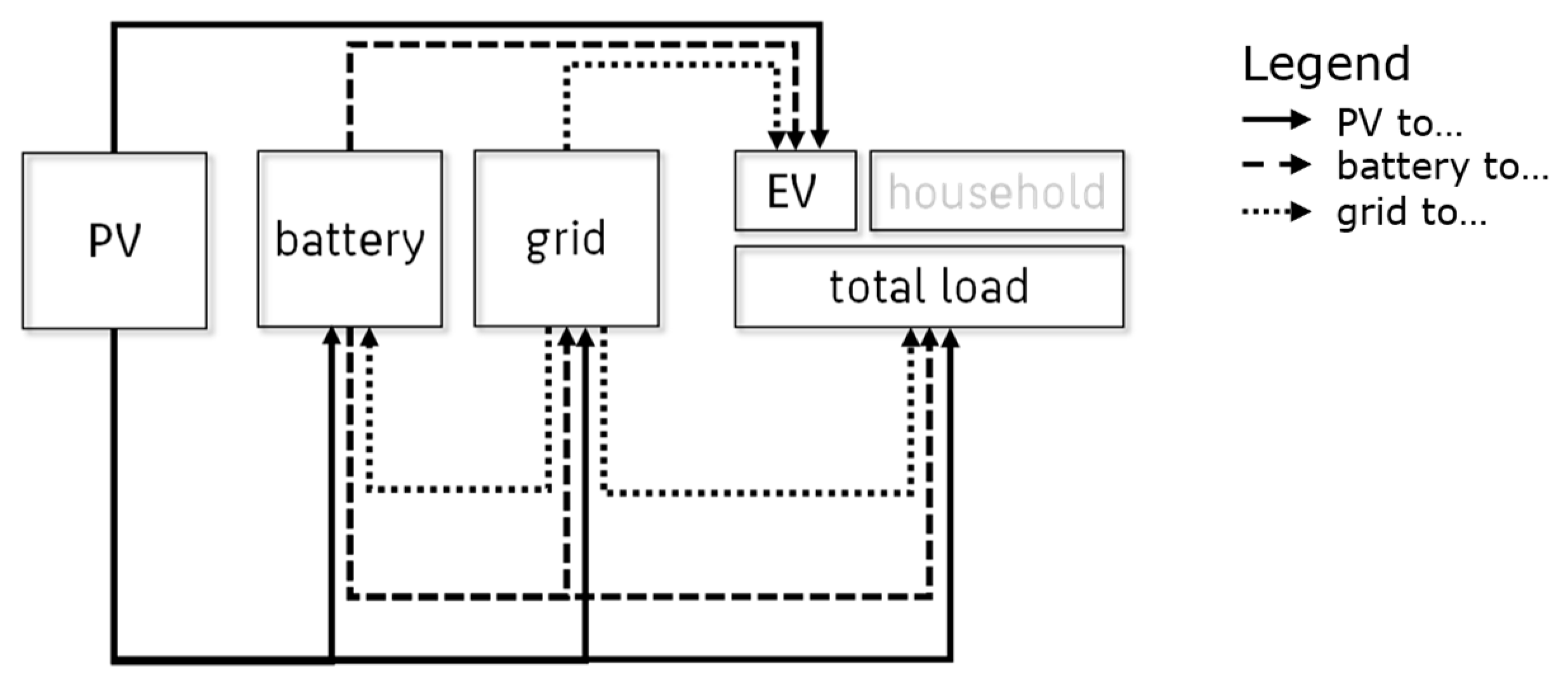

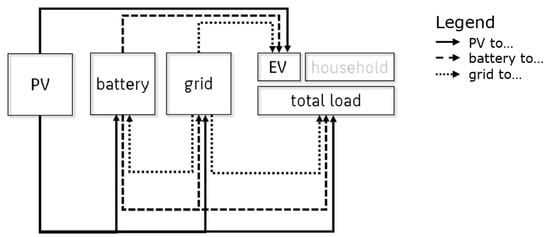

An energy system depicted in the data is illustrated in Figure 1, showcasing all relevant power flows. The system consists of a grid-connected PV generator, which includes a battery system, residential load, EV charging as a sub-entity, and a grid connection. Both the PV and battery system can supply power to different loads or feed surplus energy into the grid. The loads are categorized into different sinks, such as households and thermal applications on the one hand, and the EV on the other. Note that EV usage is measured separately, while total load is the residual power. In Figure 1, boxes represent the system elements, while arrows indicate the flow of power from a source to a sink.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the represented home energy system elements. Arrows symbolize power flow from one end the other.

Thus, PV power is represented by a straight arrow, battery power by a dashed arrow, and grid power by a dotted arrow. It is worth noting that not all quantities within the data are measured by a dedicated meter. For example, EV power is given by the electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE), while PV and battery power are provided by a calculation from the system integrator. It integrates PV (DC-) converter values, battery (DC-) converter values, and AC values from the PV battery inverter.

Only the grid power is measured by a dedicated energy meter. The total load is therefore the value that results when all other values within a certain time step are added together. The power flows between the units were taken from Fronius International’s calculation; however, they can be recalculated using the initial measurement. Contrary to the original data, this study states that the PV system prioritizes household demand before powering the EV, rather than powering both according to their share of the total load. This is crucial when assessing the solar contribution to EV charging.

Since the system integrator holds more than the provided data of interest (PV + EV + X), export filters were applied. First, only data that include EVSE were included. Second, at least one year of monitoring was acquired to ensure accurate solar evaluations; therefore, two years of data per household were provided by Fronius International to meet this requirement. Since one household could have up to two years of usable data, they were analyzed as two separate datasets, even though they may be very similar. Third, data were extracted solely from the “D-A-CH region” (Germany, Austria, and Switzerland), assuming a comparable socio-economic environment.

The 3808-household-dataset provided consists of a metadata table and a time series table for each anonymous user. The metadata table includes a system description, including installed PV power, presence of a battery system, country, four-digit postal code, and Boolean representation of other system elements. Time series with a resolution of 5 min are available for PV power and power to the battery, total load, EV, and grid. In addition, power from the battery to the total load, EV, and grid and the state of charge (SOC) can be used for the analysis. Finally, all power flows from the grid to the battery, total load, and EV can be found in the dataset. Note that the calculated time series are not perfectly balanced. This may be due to the combination of DC and AC values on one side and differences within one time stamp on the other side. Additionally, measurement deviations must be considered. The dataset is suitable for evaluations over one year.

2.2. Monitoring Data—Data Preparation

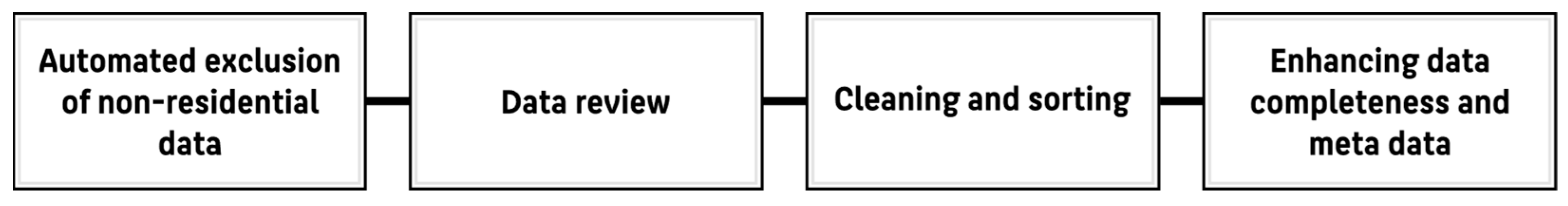

To reliably capture diurnal and seasonal patterns of PV generation, only data with high-quality recordings that are nearly complete for the full year are considered. Data processing is documented in the following section. A schematic overview of the data processing is given in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart outlining the data processing procedure used in this study.

First, general exclusion rules were defined to specify the dataset. Therefore, PV power above 30 kW and a load without an EV greater than 15 MWh/a were assumed to be non-residential and omitted. This assumption is based on empirical knowledge, e.g., [16], and similar applications of power limits in other studies [17,18,19].

In a second step, the data were reviewed, and records with poor data quality or implausibility were excluded. Examples of frequent exclusion criteria include changes in the installation (PV or battery) during recording, the start of recording within the year, unmonitored devices such as combined heat and power generators or additional PV, and frequent occurrences of nightly PV surplus or zero-load periods.

Third, the data were cleaned and sorted for further processing. Small data tips of less than one hour were interpolated. Examples of data tips include artifacts, negative or zero load, and constant or missing values. Missing values of less than one week in a row were accepted, but manually revised. Those gaps were typically filled with data from the same recording, e.g., for the load using values from one week earlier and for PV using temporally adjacent values. This approach preserves typical temporal patterns in a persistence-based manner.

Additionally, households with missing EV loads greater than one month were excluded. Since charging behavior remains relatively constant throughout the year, more than 10% of the charged energy is often missing. In these cases, it is no longer possible to perform a detailed and accurate evaluation of charging behavior.

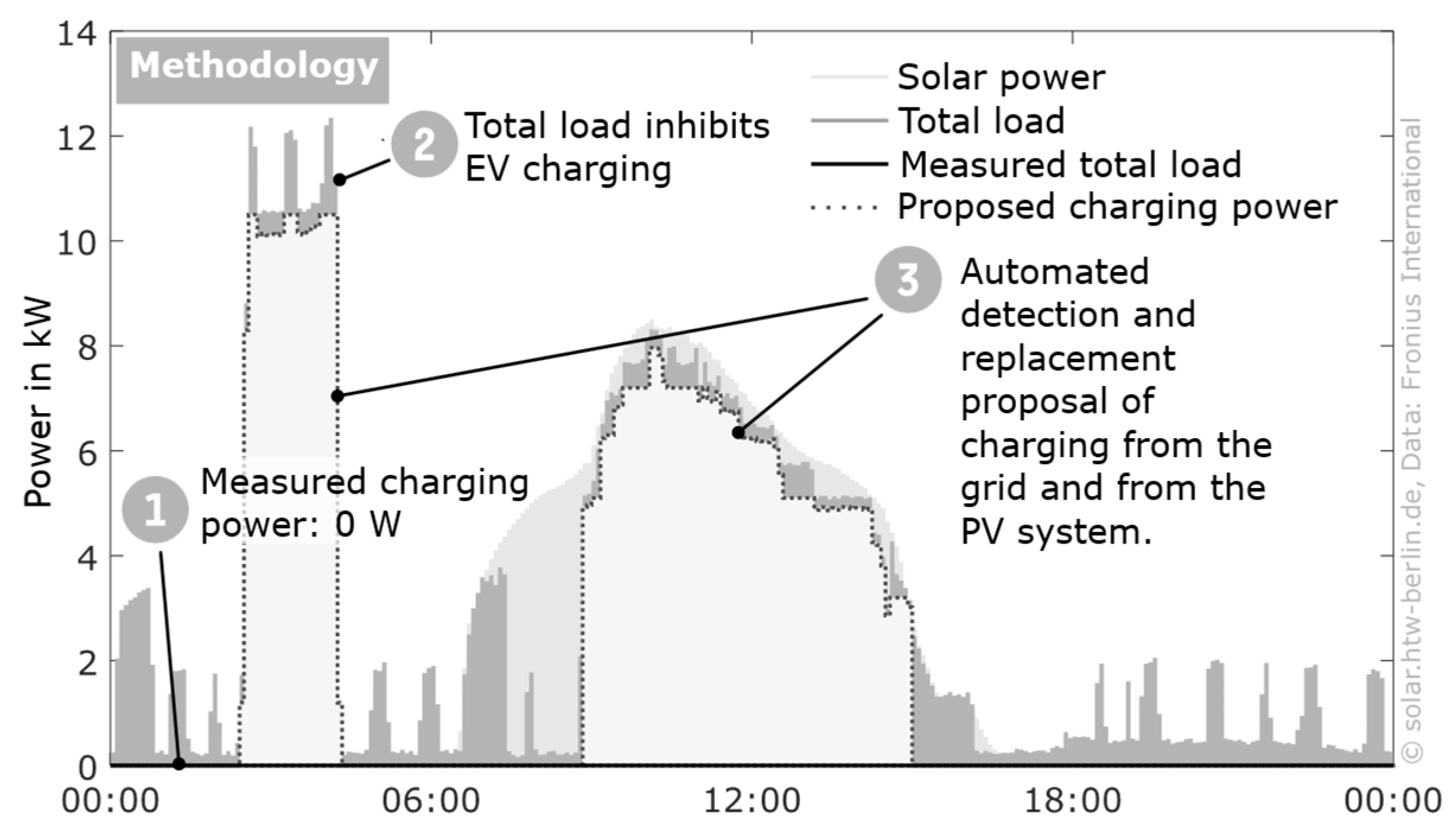

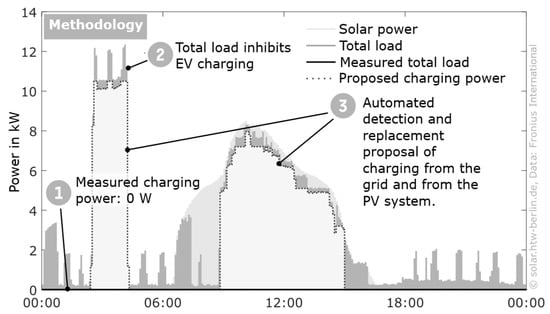

A common issue for data completeness is the disconnection of the EVSE from the internet or an unmonitored secondary EVSE, resulting in unmonitored charging events; see Figure 3. As a result, this may lead to an increased household load, as the EV cannot be subtracted from the total load in the calculation. To address this problem, a generic detection algorithm was implemented to identify charging events with steep power edges, indicating uncontrolled grid charging or solar charging, by finding loads that align with solar power for a longer period.

Figure 3.

Methodological framework for detecting unrecorded charging events. Data: Fronius International.

The detection algorithm first identifies the maximum charging power, as this may be individually limited by user-defined settings. In a second step, all load edges at this power level are detected, since they are likely to indicate charging events.

In addition, temporal alignment of the load with PV generation is used as an indicator of solar charging. Potential charging events shorter than 30 min or with an energy content below 3 kWh are neglected, as other applications (e.g., cooking or water heating) are more probable in this range.

Moreover, the energy consumption of the identified potential charging events is analyzed. If the corresponding day or surrounding time steps exhibit unusually high energy consumption, or if a smaller, measured charging event occurs shortly before or after, the likelihood of an unrecorded charging event is increased.

Based on the identified potential charging intervals, the charging power is reconstructed using the statistical distribution of measured EV charging power under comparable total load conditions. In essence, the temporal profile of a replaced charging event follows the characteristic shape of a charging event with similar power levels. This approach allows individual load profile characteristics to be preserved. At the same time, the stochastic nature of the reconstruction leads to slightly increased power fluctuations compared to directly measured charging events.

The detection algorithm was validated against fully recorded charging events. Detected but unmonitored charging events were reviewed and replaced if deemed acceptable. In particular, when a heat pump is active, the resulting load profile can resemble grid-based EV charging, which leads to conservative omission in most cases after a review. The addition of further charging events made it necessary to recalculate secondary power flows, e.g., direct consumption of PV energy by the EVSE.

In addition, some metadata have been partially corrected and expanded. According to the provider, the metadata sometimes contain manual entries by installers or costumers and are therefore prone to errors. At the same time, some PV systems have been expanded over the course of the year and the metadata only contain the higher value. In particular, PV power was adjusted to plausible values where necessary. Indicators for misleading values were the specific PV energy and maximum power output compared to the noted installed power. Furthermore, Boolean entries of further system elements were set to plausible values, for example, if a battery system was expected from the metadata but no power flow could be found in the time series.

Note: A quality classification was applied during the review process, since some of the data were not applicable to all analyses. This led to different numbers in various analyses. Table 1 provides an indicative view of the total dataset numbers. Over 13% of the households have more than one year of monitoring data. Since each year represents a distinct observation with different load and generation patterns, each annual record is treated as a separate household-level dataset. For readability, all records are referred to simply as “households” throughout the study.

Table 1.

Data sample statistics, showing the share of the sample suitable for general statistics and all analyses, sorted by one-year time series and households, which may include two years of recording.

Since the metadata lack relevant entities like the presence of electrical heating devices, such as heat pumps or batteries, these metadata were derived from an analysis of the individual time series. Furthermore, quantities for evaluation can be derived from the data. The methodological approach is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Methods to enhance the metadata.

Additional statistical analyses used to support the interpretation of the results are described in Appendix A.

3. Results

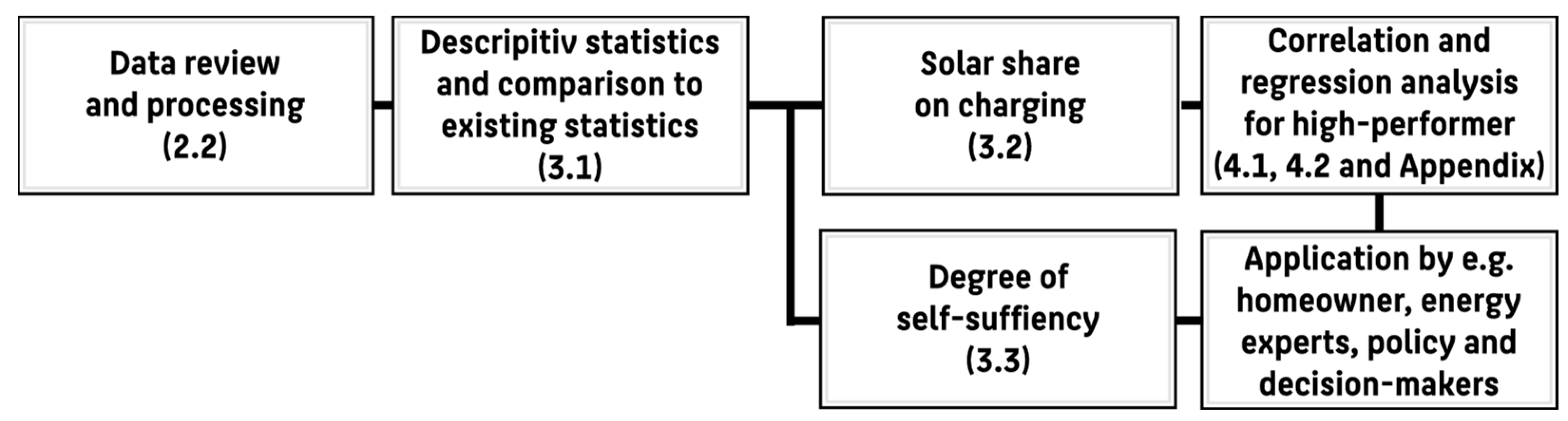

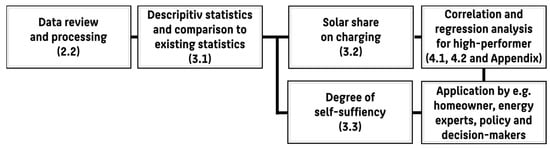

To explore the data, descriptive statistics and visualizations were used. This provides a better understanding of charging behavior and solar utilization patterns. The flowchart in Figure 4 presents an overview on the exploration approach.

Figure 4.

Flowchart illustrating the structure of result presentation. Numbers refer to the corresponding sections.

Preliminary data were prepared and filtered; see Section 2.2. The results were structured into three sections. Section 3.1 provides descriptive statistics to support data interpretation. Basic metrics of photovoltaic system capacity, household electricity consumption, and electric vehicle charging are presented, and differences from publicly available datasets are identified and classified.

Section 3.2 examines the solar share of EV charging. Influences such as installed PV power, charging behavior, and charging frequency are analyzed. This section concludes with an assessment of technical measures to increase the solar share, specifically the impact of stationary battery systems and the comparison between dynamically controlled charging and uncontrolled charging at maximum power.

Section 3.3 extends the analysis to the household level by evaluating the overall solar share of electricity demand, expressed as the degree of self-sufficiency.

To support the interpretation of the observed patterns, the results presented in this section are further discussed in the following section, with a focus on households achieving high solar shares. Additional statistical analyses are provided in the Appendix A, including correlation analyses (Appendix A.1) and logistic regression models assessing factors associated with high solar shares (Appendix A.2).

3.1. Statistic Description

According to Table 1, the absolute number of analyzed data is more than 725 years within 642 households. All households operate a PV system and an EV. The proportion of households with a stationary battery storage system (BAT) is 48%. The battery capacity is less than 15 kWh in more than 90% of cases. In addition to the battery, an electrical heating system is observed frequently. Users who already operate a heat pump or other electric auxiliary heating systems accounted for 42% (HP). This is particularly relevant as households with thermal applications have a higher energy demand, especially in winter.

The sample appears to be significant in comparing German households, according to a study by the KfW Institute [5]. Table 3 compares the prevalence of selected technical appliances. The sample shows a 7% higher share of heat pump households, which may result from data processing effects but also from the different regional basis: while the KfW survey covers Germany only, the dataset includes households from the D-A-CH region. Below is a statistical description of the dataset, focusing on PV system characteristics and load analysis. Special attention is given to the EV charging analysis.

Table 3.

Proportion of household equipment according to KfW and the sample (PV: solar system; EV: electric vehicle; HP: heat pump; BAT: battery storage). Data: KfW [5] and Fronius International.

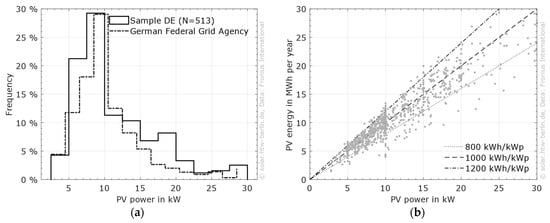

3.1.1. PV Statistics

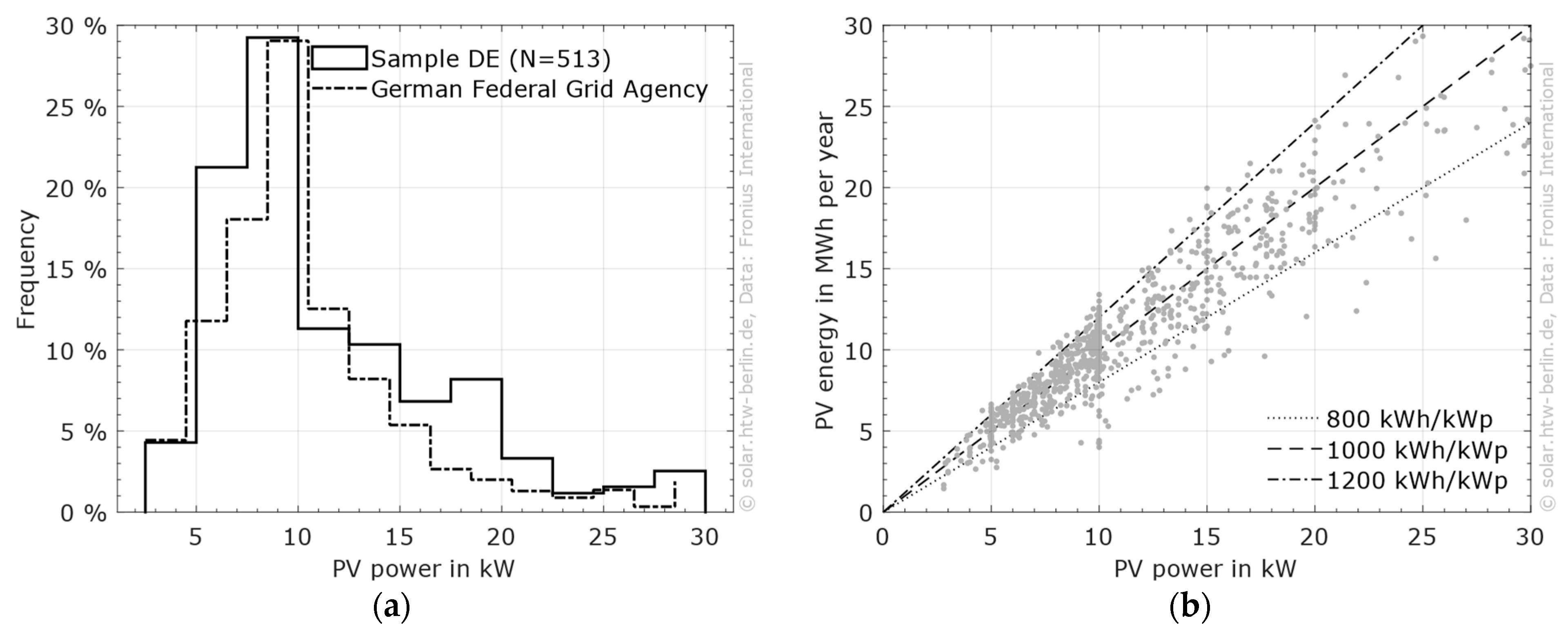

The distribution of the installed PV power is shown in Figure 5a and compared to the distribution of the PV system power between 1 kW and 30 kW according to the German Federal Grid Agency [22]. This highlights the generalizability of the dataset.

Figure 5.

(a) Distribution of the installed PV power. (b) Yield and specific yield ( n = 849). Data: Fronius International; German Federal Grid Agency.

The PV power in the sample is slightly higher on average than would have been expected based on the Federal Grid Agency. Hence, the distribution is not typical for PV installations in general but may be biased by PV-EV households. The distribution has its median at 10 kW and the middle 50% range from 7.5 kW to 14.7 kW.

The specific yield of PV systems is a key measure for the quality of PV systems, varying along geographical locations and shading of the system. Figure 5b illustrates the specific yield versus PV power of the sample. The median specific annual yield for the PV systems in the dataset is 960 kWh/kW, with the middle 50% ranging from 830 kWh/kW to 1090 kWh/kW. The absolute annual yield is adjusted based on the installed PV capacity, resulting in a wider range of values. Annual yields vary from 4.5 MWh to 30 MWh, with a median value of 10 MWh. It is noteworthy that 90% of the systems in the sample achieve an annual yield greater than 7000 kWh, which, for many households, equals net production. Hence, PV self-sufficiency is mostly linked to the alignment of consumption.

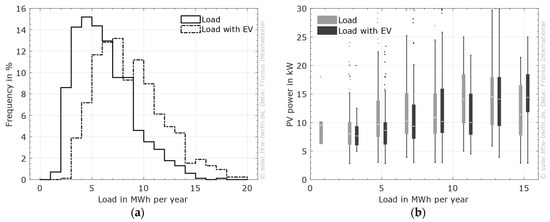

3.1.2. Load Statistics

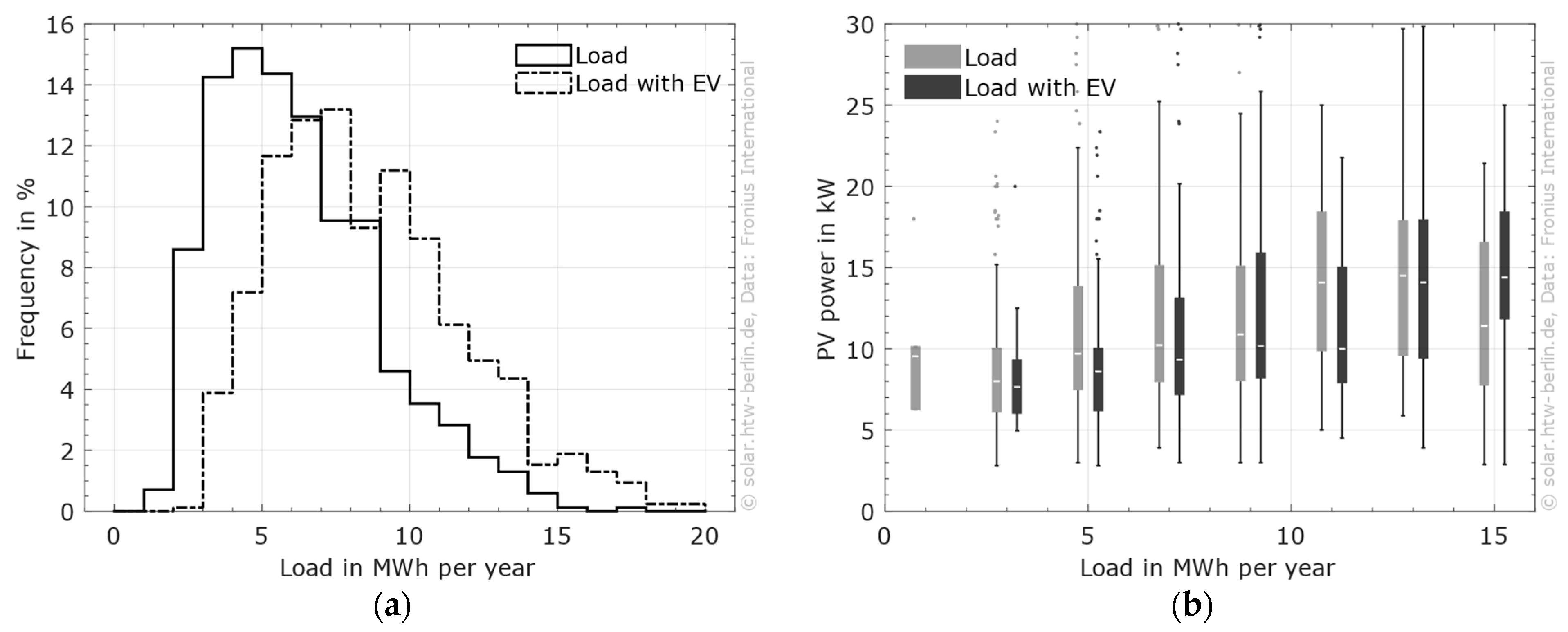

As Figure 1 in Section 2.2 shows, the load of the considered systems can be divided into three parts: total load, household load, and EV load. Figure 6a shows the distribution of the household load and the total load. At the median of the dataset, 5.6 MWh per year are consumed by the household and 8.1 MWh if an EV is included.

Figure 6.

(a) Distribution of the total load and the load excluding EV. (b) Correlation of PV power and load. n = 849; data: Fronius International.

The distribution is wide, with the middle 50% of the households’ load ranging between 3.9 MWh and 7.5 MWh per year. A similar variation around the median appears for the total load with an EV.

The energy consumption of the households is slightly higher than expected from other surveys [23]. This can be explained by the fact that a larger part of the sample already uses electric or partially electric heating appliances. On the one hand, this increases the energy demand; on the other hand, it indicates that the sample is likely to be biased in terms of income, environmental awareness, and household equipment compared to the general population. Median energy consumption is summarized in Table 4 for households with different appliance combinations.

Table 4.

Median energy demand with and without EV.

In Figure 6b, energy demand is correlated with solar power, linking the already-known entities. It is classified in 2.5 MWh bins to simplify visualization. Installed power increases with energy demand, by a median of 0.5 kW per 1000 kWh. It remains unclear whether high consumption or high production drives this observation. Nevertheless, this is not unplausible, due to rebound effects, and could align with behavioral adaption shifting consumption in sunny hours [24,25].

3.1.3. EV Statistics

The following section focuses on vehicle use. It should be noted that complete data on vehicle use is not available in this study, and that only the proportion of energy charged at home is considered. Several studies have shown that, on average, this accounts for about 70% to 75% of the energy charged [2,10,26]. However, as the NOW company states in its survey on EV users, “There is some variation in the proportion of private charging. While half of the respondents said that more than 90% of the charging was done at home, 10% said that only up to a quarter of the total charging volume was done at home” [2].

The energy charged by electric vehicles at home within the sample ranges from 500 kWh to 6000 kWh per year. The median is around 2000 kWh, and 50% of the households’ charge between 1400 kWh and 2800 kWh per year at home. It is worth noting that locations with lower population densities have on average 10% more charged energy than densely populated locations. This is plausible because daily commuting times are longer in rural areas than in urban centers.

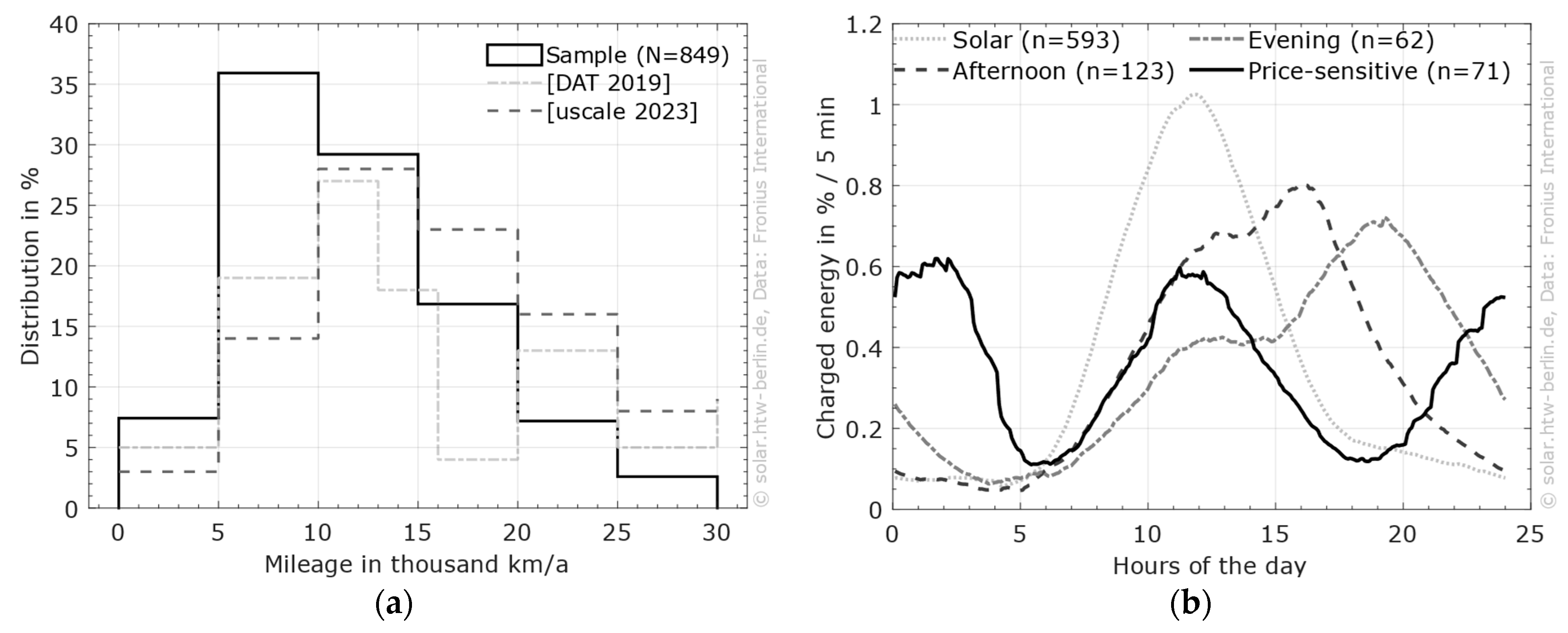

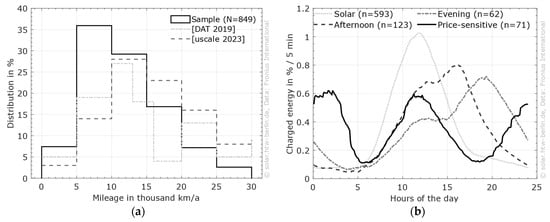

For better comparability between fossil and electric mobility, the amount of energy can be roughly converted into annual kilometers driven (mileage). To account for real-world driving conditions and charging losses, a conservative average electricity consumption of 20 kWh per 100 km is assumed. Therefore, Figure 7a shows the distribution of kilometers driven for the sample, a survey on EV users conducted by the market research firm USCALE [10], and a survey of all drivers conducted by the German Automobile Trust [27].

Figure 7.

(a) Distribution of the mileage in comparison to different studies. (b) Clustered distribution of charged energy over the day. Data: Fronius International.

The USCALE survey sample covers an average mileage of 12,670 km per year. This is slightly higher than the value of 12,320 km per year stated by the Germany’s Federal Motor Transport Authority [17]. With 11,032 km per year, the median mileage of the sample of this article is even lower. This can be explained by the fact that only home charging is included in the monitoring data. The 70% to 75% of home-charged energy mentioned above would fit quite well for this distribution to resample the USCALE survey distribution. On the other hand, the automobile trust survey on fossil fuel drivers gives a lower mileage distribution, which may indicate that EV users drive more than their fossil equivalents [27].

Besides driving, which impacts total energy consumption, the timing of charging has a huge impact on what energy source is used in the car. If the charging process is started in the morning or during the day, it is likely that a greater proportion will come from solar energy. On the other hand, dynamic tariffs, with low prices at night and midday, are obliged to encourage grid-friendly charging behavior by shifting loads from the morning and evening to lower-priced times.

One measure to gain insight into individual charging behavior is a mean day profile, which contains the energy portion of each time step. A k-means cluster analysis was performed on these mean daily profiles to identify representative charging patterns. Four clusters were chosen, as they provide the most meaningful differentiation of functional charging patterns. Additional clusters did not reveal new behavioral types but merely split the existing four categories into less informative subgroups. The resulting typical profiles are shown in Figure 7b. The average daily pattern could be clustered into four groups:

- At 70%, most of the households charge in a solar charging pattern (n = 587). They can be divided into two groups: those who charge as soon as possible and those who charge during the day.

- In total, 15% of the sample tend to charge in the afternoon but partially use solar charging whenever possible (n = 123).

- A total of 7% charge in the evening hours, often charging at maximum power on arrival (n = 61); this is a typical behavior of users without a PV system [2].

- Lastly, 8% shift their charging to midday or night hours, off-peak relative to grid load. These households are assumed to use dynamic tariffs (n = 71).

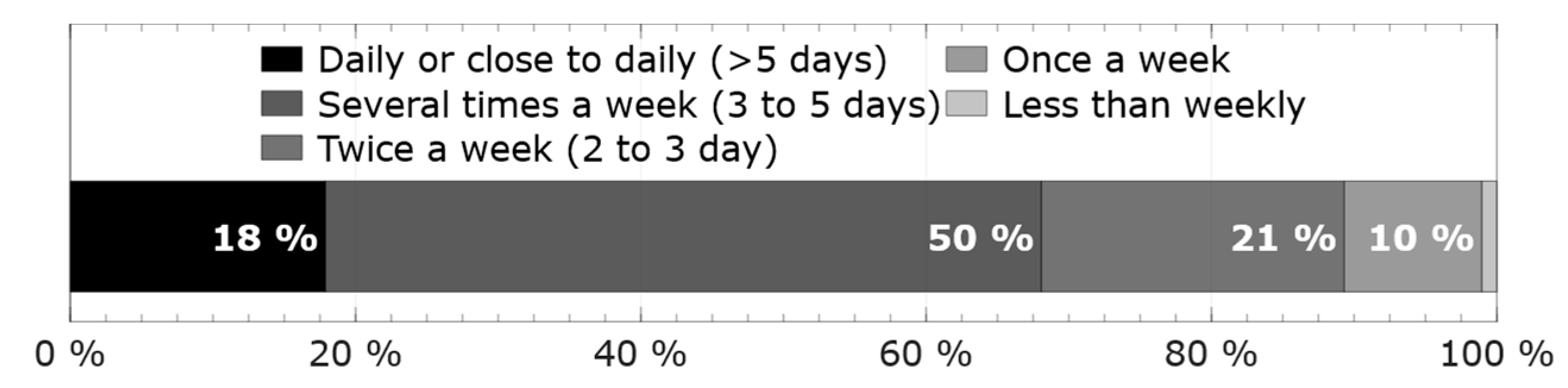

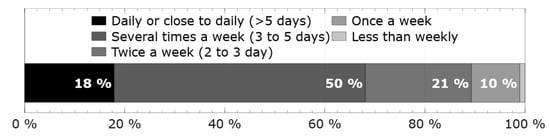

The distribution of the charging frequency of the 849 datasets is shown in Figure 8: In total, 18% of households plug in their electric vehicle every day or at least 5 days a week. Exactly half of the households charge their vehicle 3 days to 5 days per week. For 10% and 1% of the households, respectively, charging four times a month or less is the exception rather than the rule. There is a tendency for higher charging frequencies to be associated with higher energy demand.

Figure 8.

Distribution of charging frequency n = 849. Data: Fronius International.

A question remains: what are the reasons for households with low charging frequency, e.g., less than twice a week, to shift their charging? These households are found to charge more frequently on the weekends, have slightly smaller PV installations, and charge more energy at once. Hence, two complementary interpretations are possible: either drivers are confident that their battery capacity is sufficient for all weekly trips, or they intend to charge using solar energy but cannot do so during the week, resulting in weekend charging when cleaner energy may be available.

As the energy charged per charging session is distributed within an individual household, the median of the charging events for each household can be compared more easily. For 75% of households, the median charge event consumes less than 12 kWh of energy, while the median is 9 kWh. The median energy per charge of this infrequent charging subsample increases by about 30% to 11.5 kWh, which is close to the upper interquartile of the full sample. Seventy-five percent charge less than 18.5 kWh per charge. The distribution within the individual households is more spread out compared to the full sample.

Beyond total energy, charging frequency, and energy per event, the dataset also allows the identification of charging interruptions. Solar charging sessions often exhibit such interruptions, typically caused by operational constraints such as phase switching or waiting for surplus PV power above the minimum charging threshold. The number of phase switching events could not be determined, as the dataset has a temporal resolution of five minutes, and such events typically last less than one minute. However, interruptions longer than five minutes could be estimated. Within the sample, 15% of chargers exhibited fewer than 182 power-off events per year. More than 53% recorded over 365 interruptions annually, while 12% experienced more than 730 power-off events. This corresponds to an average of 1.5, 2.3, and 3.2 interruptions per charging event, respectively. These results indicate that repeated pauses are common and vary substantially across households.

3.2. Solar Share on EV Charging

Solar power has a strong diurnal and seasonal progression; car use is dominated by daily or weekly usage patterns. As already shown in Figure 7b, the majority of the sample shows charging behavior adapted to the solar generation. Most of them adapt the charging power to the solar surplus power that would otherwise be fed into the grid. But the question is as follows: to what extent can a solar system power an electric vehicle? And what are the most important factors for a high solar share?

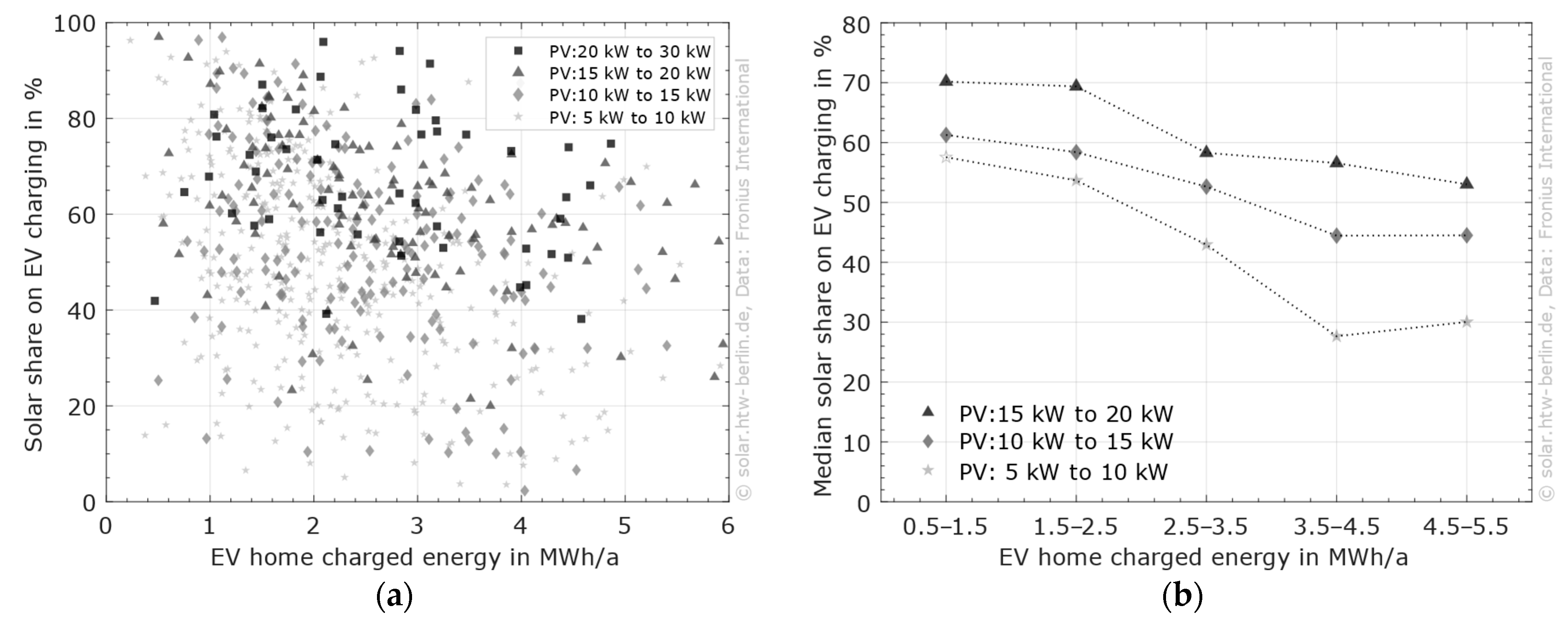

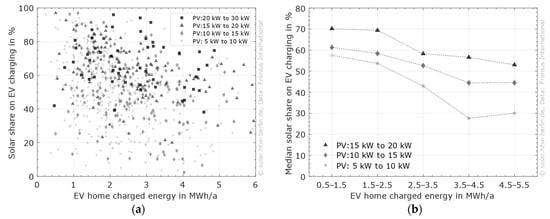

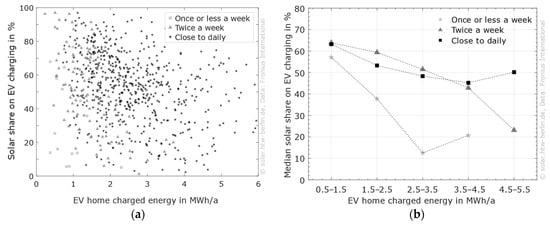

3.2.1. Installed PV Power

As a higher installed power is associated with increased energy production, it could be assumed that the solar share also increases. However, Figure 9a shows a highly dispersed solar share of charged energy in relation to the amount of energy charged and the PV power indicated by the color and style of the marker. The share of solar energy varies by about ±40% around a median of about 60%, decreasing slightly with higher energy demand and kilometers driven. The available solar energy is one reason for the distribution of the solar share, as darker data points, indicating larger PV installations, are mainly in the upper region, and lighter data points tend to be in the lower left corner. But households with similar PV capacities can achieve very different solar shares. This indicates that surplus alone cannot explain the observed variation, which motivates the subsequent analysis of behavioral charging patterns.

Figure 9.

(a) Solar share of charging versus the energy that is charged at home by the EV (n = 725). Colors and size indicate PV power and PV yield. (b) Median of the solar share of charging versus classified home-charged energy and PV power (n = 632). Data: Fronius International.

However, the tendencies could also be described by the median shown on the right side of Figure 9b. It can be seen that 75% of smaller PV systems could use more than one third of solar energy in their EV, while 50% make up more than 48% and 25% even more than 63% of solar share. A typical residential PV system of just over 10 kW will power the EV for half of its home-charged journeys, and for more than 25% of the households, 2/3 of their EV mobility comes from the sun. PV systems larger than 15 kW have a big advantage in terms of solar energy availability during winter and transitional periods. More than 75% reach 50%, and the top 25% is able to power more than 70–80% of their home charging by the sun.

Across all power classes, an increase of 5 kW to the next power class was found to increase the total solar share by about 2% to 10%. Within the sample, this is associated with an increase in energy consumption, as the median user with 5 kW to 10 kW consumes 2 MWh per year for mobility, while households with larger PV systems consume, on average, around 2.5 MWh per year. The increase in solar share is therefore slightly higher in a comparable setting.

Note: The highest solar shares, above 80%, require a PV system of more than 10 kW. A smaller PV system can only achieve comparable results at very low annual mileage. Even if the availability of solar energy is a reasonable explanation, it cannot explain all the diversity.

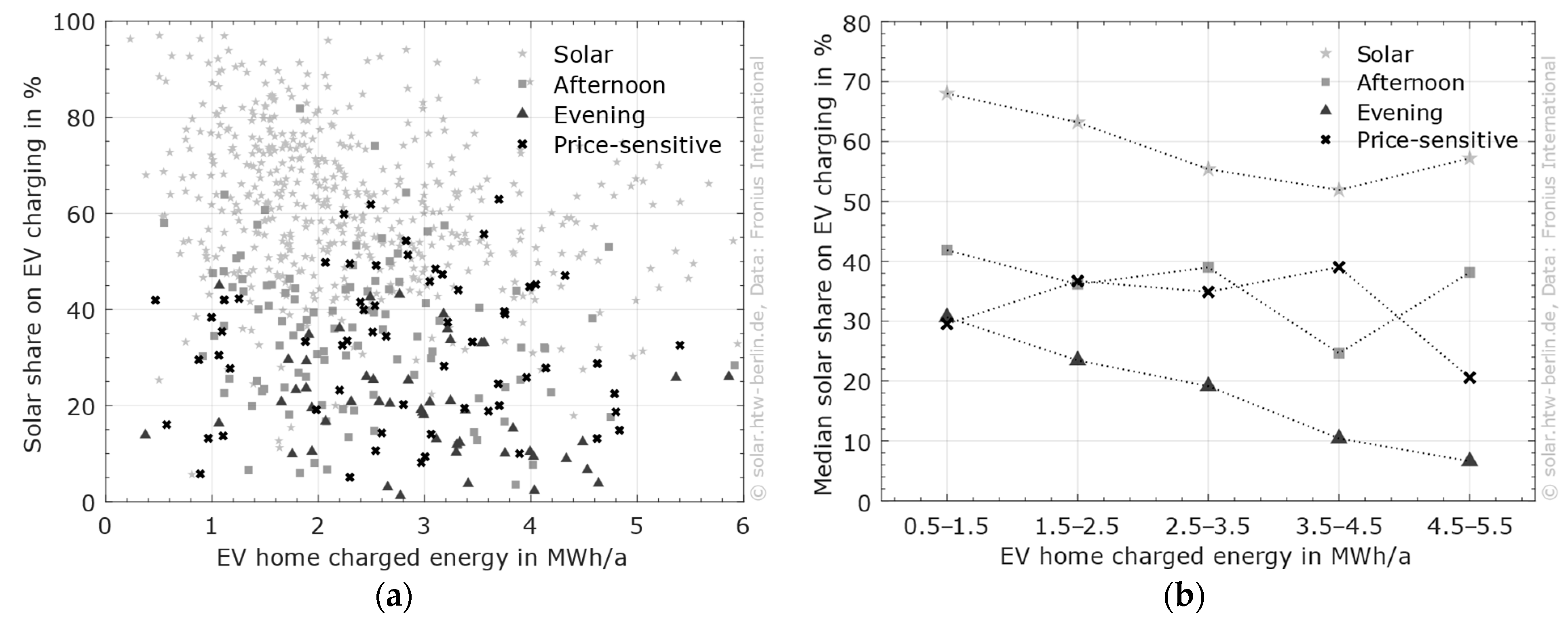

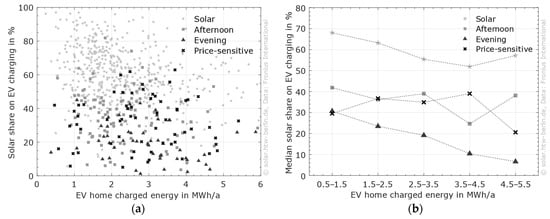

3.2.2. Charging Cluster

Another plausible source of variation is charging behavior. Accordingly, the charging patterns are examined in analogous manner to PV power. Figure 10a shows the full distribution. Contrary to the above-mentioned figure, here, colors and marker styles indicate the different clusters identified in Section 3.1.3 instead of PV power. Not surprisingly, a solar-adapted charging pattern is the main driver for the highest solar shares of EV charging. Even if some households that tend to charge in the afternoon or are price-sensitive might have higher solar shares, the majority can be found below 50%. Households from the usual evening charging cluster remain well below 30% solar share.

Figure 10.

(a) Solar share of charging versus the energy that is charged at home by the EV for different charging clusters (n = 725). (b) Median of the solar share of charging versus classified home-charged energy by sensitivity of charging clusters (n = 715). Data: Fronius International.

The median values in Figure 10b show that solar chargers could easily drive more than 2/3 just by using their PV system. Even though the share decreases, the absolute solar kilometers increase with higher mileage. The median solar share decreases by about 25 percentage points, when charging is often shifted to the afternoon. Nevertheless, 75% of this cluster could cover more than 30% of their daily trips with cheap solar energy and the top 25% even more than 50%. In addition, from 62 households that charge primarily in the evening, the median uses the grid for more than 80% of the charged energy. Not surprisingly, these households consume more energy per charging session while charging less frequently. Among them, the middle 50% can reach solar shares between 10% and 25%.

In between these clusters lies the price-sensitive cluster. Even if their charging takes place mainly during the night hours, solar-intensive charging sessions can also be observed on weekends. At the same time, their energy demand drops dramatically on Mondays and Tuesdays. It is worth noting that the median solar share sorted by cluster shows a very low dependence on the charged energy. Finally, it can be stated that solar shares of around 30% can be achieved by most of the charging profiles in the sample. It is assumed that any restrictions on vehicle availability do not influence the results. Only a small adjustment of charging behavior is required to increase the solar share, e.g., plugging in more often or charging only what is needed from the grid, such as target SOC. For the highest solar shares, solar-adapted behavior is required.

Figure 10 demonstrates that charging behavior explains a substantial share of the observed variation. The clusters form distinct levels of achievable solar share, showing that the temporal alignment between charging and PV availability is more decisive than PV capacity alone. Solar-adapted charging consistently yields the highest shares, whereas evening-dominated patterns remain structurally limited to low solar contributions.

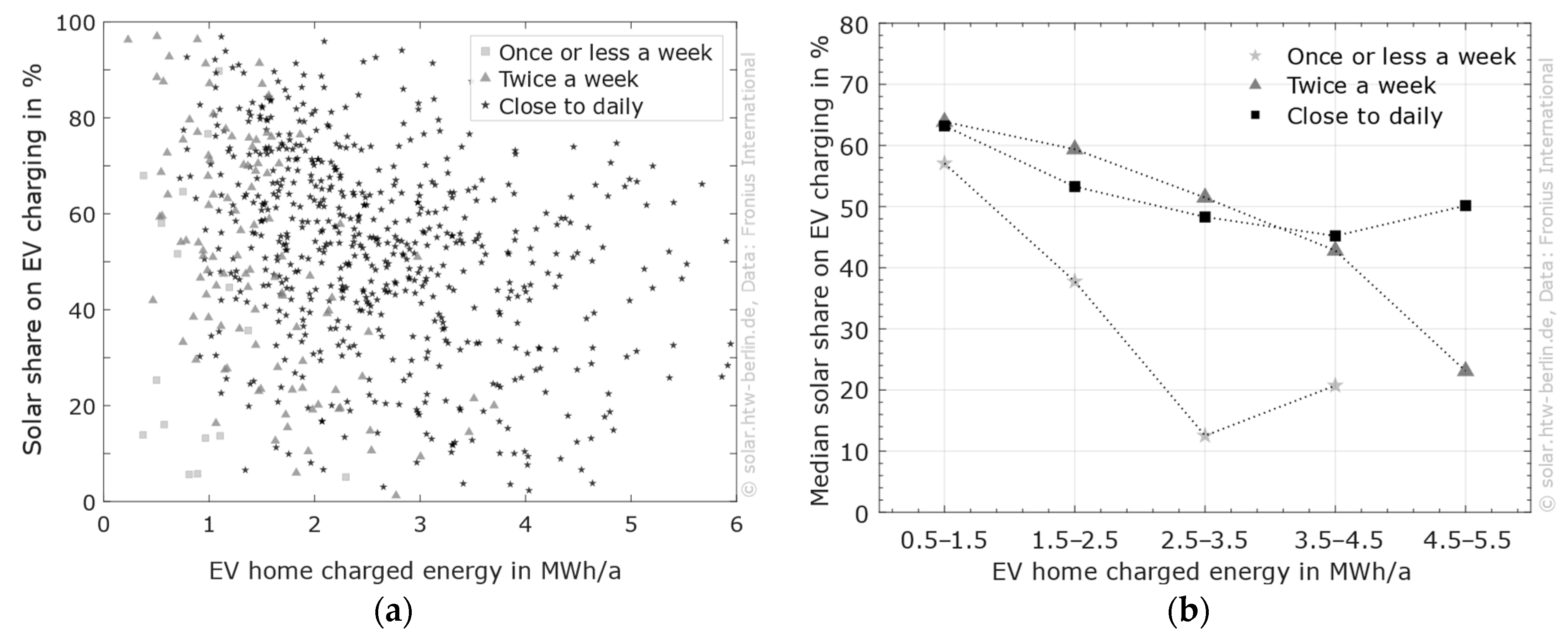

3.2.3. Frequency of Charging

The proportion of solar energy can also be assessed in relation to charging frequency. Figure 11 illustrates the correlation between home-charged energy and solar share, with color indicating weekly charging events.

Figure 11.

(a) Solar share of charging versus the energy that is charged at home by the EV frequency of charging (left, n = 725). (b) Median of the solar share of charging versus classified home-charged energy by sensitivity of charging events per week (n = 715). Data: Fronius International.

The overall pattern in Figure 11a remains highly dispersed. Households with low annual mileage (<2 MWh) achieve high solar shares almost independently of their charging pattern, as their energy demand can easily be met during sunny hours. In addition, households that charge daily or nearly daily are mostly located in the region where solar charging is common.

Together with Figure 9 and Figure 10, the data indicate that larger PV capacity combined with solar-adapted charging behavior increases the likelihood of frequent charging, often following a ‘plug-in and forget’ routine. A smaller group, however, achieves high solar shares through targeted daytime charging.

Median values in Figure 11b confirm that frequent charging supports higher solar shares, consistent with the diurnal pattern of solar generation. Households that align charging with sunny hours can achieve high solar shares with relatively few sessions; however, this is limited to vehicles with low annual mileage (<3.5 MWh), as higher usage requires energy volumes beyond single daytime sessions.

Overall, Figure 11 shows that charging frequency mainly reflects mobility demand and is not a major driver of solar utilization. Behavioral alignment with PV availability remains far more decisive than frequency alone.

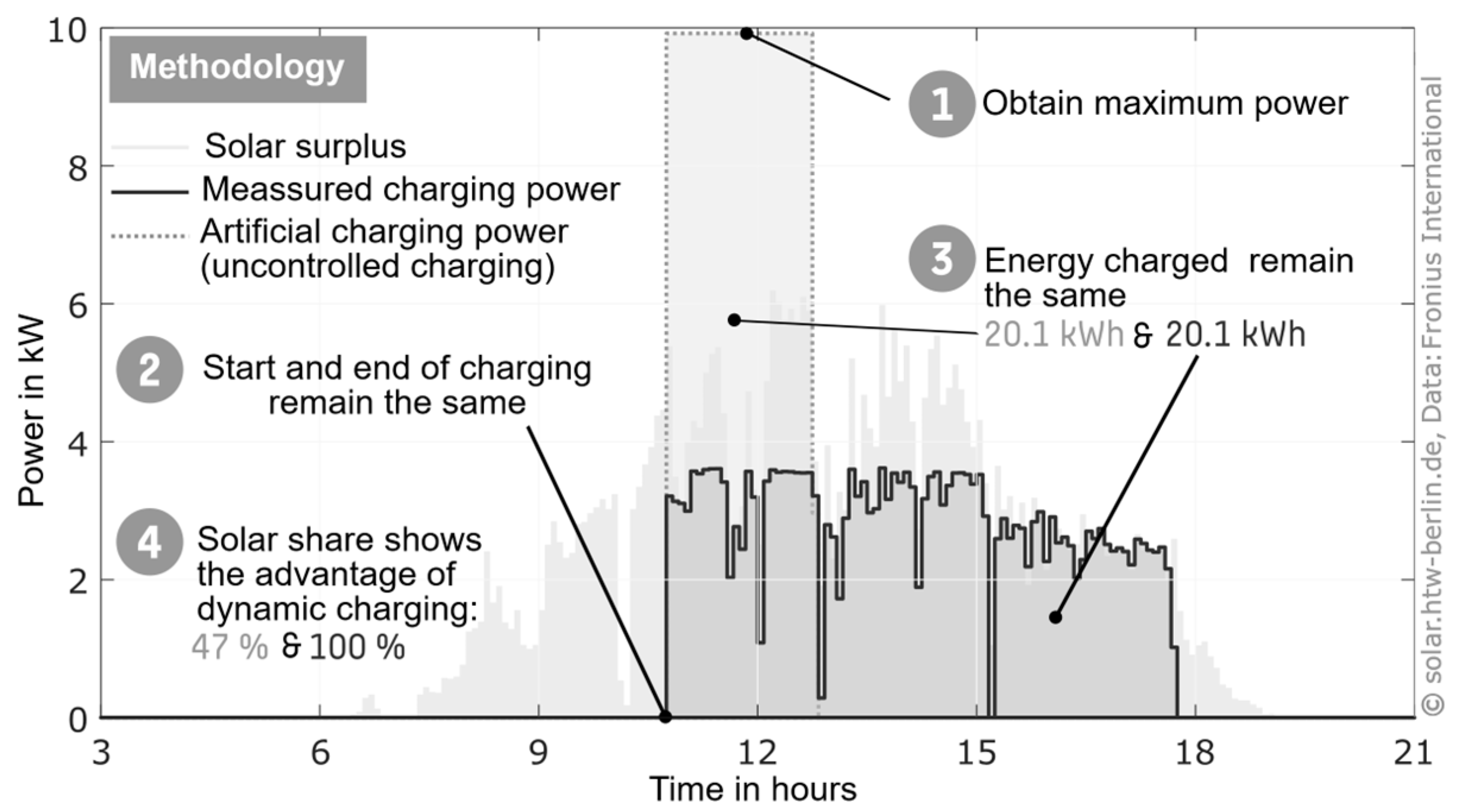

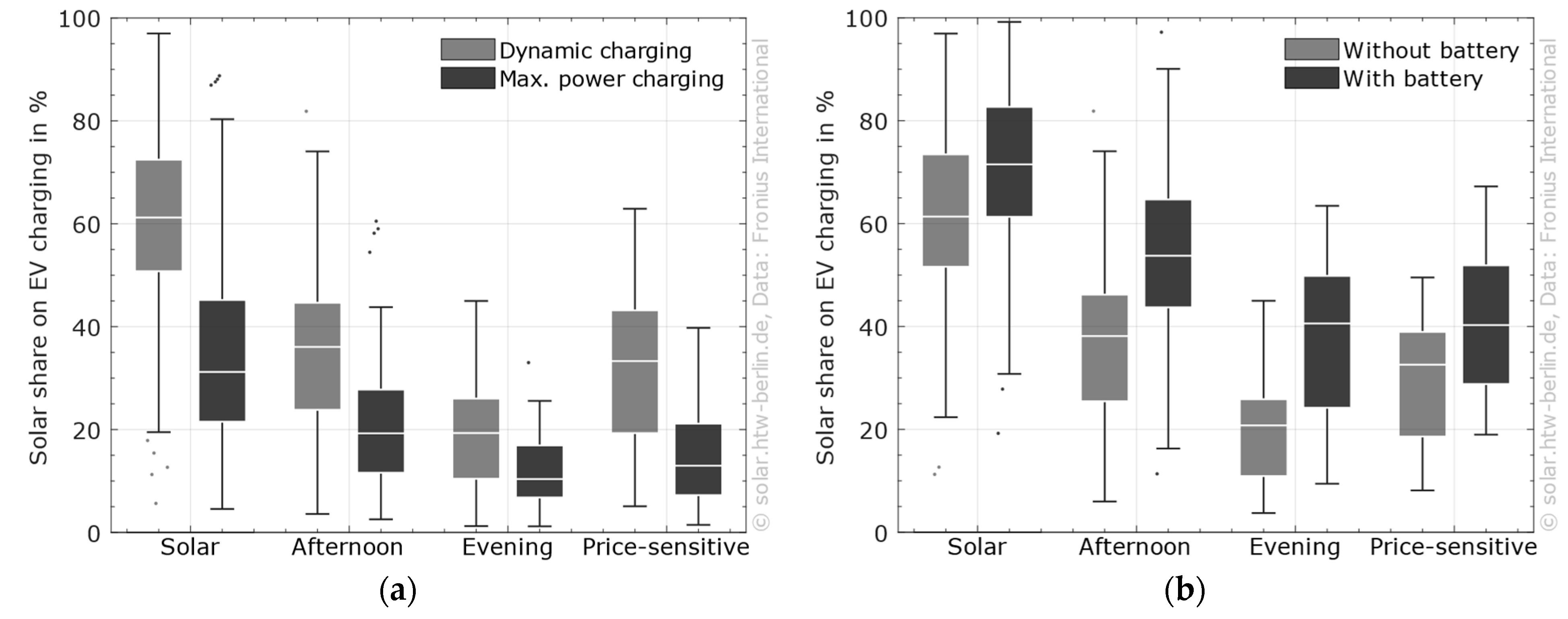

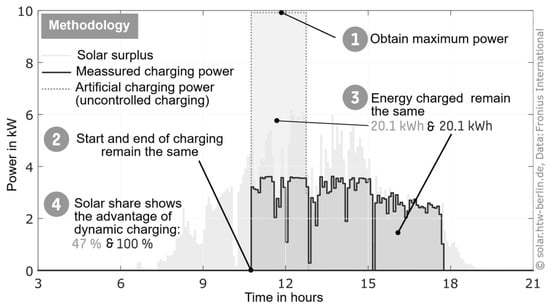

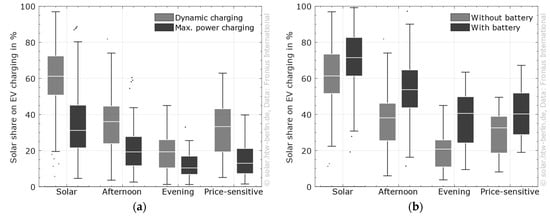

3.2.4. Benefits of Dynamic Charging and a Battery

Since most users in the sample use solar charging, the gain of surplus charging can be determined from the dataset by artificially generating uncontrolled charging time series. A methodological approach is shown in Figure 12. An artificial charging profile is set up that starts charging at the same time as the original profile (2) and charges the same amount of energy (3), but at the maximum power of the individual charging profile (1). For example, if a household charges dynamically but limits charging to 7.5 kW, this is considered.

Figure 12.

Methodology to evaluate the value of dynamic surplus charging. Data: Fronius International.

Adjustments have been made concerning small charging events, such as trickle charge. Charges of less than 3 kWh were ignored in the first step but cumulated in a second step to allocate them to a longer charge. It must be mentioned that not all households charge dynamically even if they have a solar-adapted charging pattern. In households with large PV systems, a considerable share of solar energy can be achieved without dynamic control, as uncontrolled charging may already reach the desired level.

Figure 13a shows the results of the analysis. It reveals that the benefit of dynamic charging strongly depends on the charging pattern. The median solar share of a dynamically charging EV could increase by about 30 percentage points compared to an EV that charges at maximum power, when the EV is usually charged during the daytime. The households that charge mainly in the afternoon and are price-sensitive benefit from an increased median solar share of about 17 percentage points to 21 percentage points. On the other hand, the median solar share increases by only 9 percentage points for households in the evening charging cluster. It should be noted, however, that variation within a cluster could be greater than the increase in the median.

Figure 13.

(a) Solar share on EV charging for clustered households comparing dynamic and maximum power charging (n = 725). (b) Increasing solar share advantages by a stationary battery (total number distribution of time series with a battery: solar n = 242, afternoon n = 67, evening n = 27, and price-sensitive n = 21). Data: Fronius International.

The analysis did not account for onboard charger efficiency. Prior work has shown that efficiency depends on charging power [28]. Low-power charging typically results in lower efficiency, while high-power charging achieves higher efficiency. The appliance of a median efficiency curve suggests losses of approximately 13% for solar charging compared to 10% for maximum-power charging. This estimate is approximate, as the specific EV models are unknown, and reduces the accuracy of the analysis. Nevertheless, the efficiency effect is comparably low relative to the gains of smart charging.

In addition, the timing of charging could be partially compensated by storage capacity. For example, stationary batteries typically range from only a few kilowatt-hours to less than 20 kWh, while EV batteries range from 50 kWh to 80 kWh, so it is not expected that solar charging can be fully replaced. On the other hand, stationary batteries are capable of fast, watt-precise control that EVSEs lack sometimes. Therefore, looking at the power flows shows that stationary batteries can buffer control errors and therefore maximize direct solar use.

Figure 13b shows how a stationary battery affects the solar share of EV charging for the clustered households. Note that only households with a stationary battery were considered for these analyses. Stationary battery utilization is highest when charging occurs frequently in the evening hours. If a stationary battery is considered, the median solar share of EV charging increases from 20% to about 40%. There is an increase of about 15 percentage points for afternoon charging. As expected for solar and price-sensitive charging households, a stationary battery has the least impact. It increases the median solar share of EV charging by less than 10 percentage points.

Note that battery capacity is evenly distributed across all clusters, with a median capacity of roughly 10 kWh. The distribution of installed PV capacity is also almost the same for all clusters, except for solar, which tends to have a higher installed capacity.

Figure 13 illustrates how two measures—smart charging and the use of a stationary battery—can substantially increase the solar share of EV charging. Smart charging becomes essential whenever charging power is constrained, which is relevant not only for onsite PV utilization but also for grid-connected charging under flexible connection agreements [29]. As expected, households that already charge substantial amounts of solar energy benefit most from smart charging, while evening-dominated charging profiles show only limited improvements.

The figure further shows that the effect of a stationary battery is comparable in magnitude to the timing of charging. Both measures therefore address the same underlying limitation—the temporal mismatch between PV generation and charging demand—while the latter can be implemented without additional investment costs.

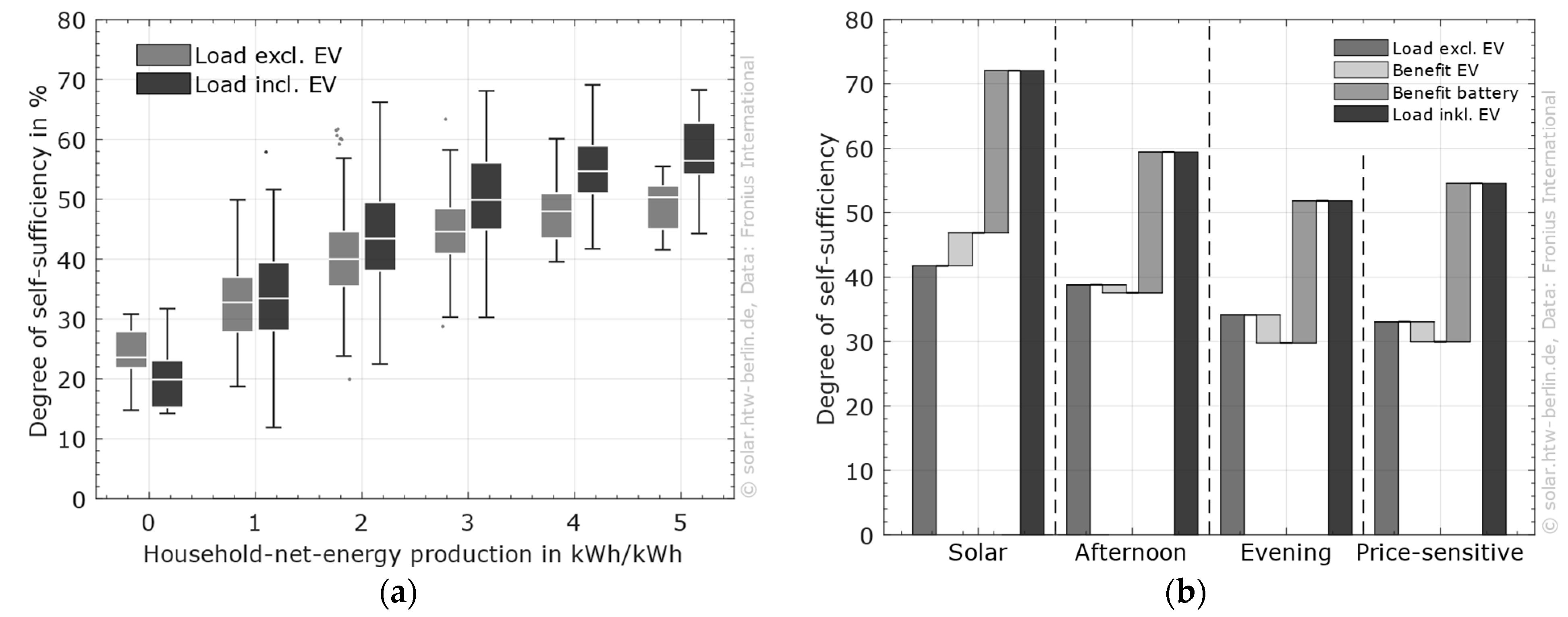

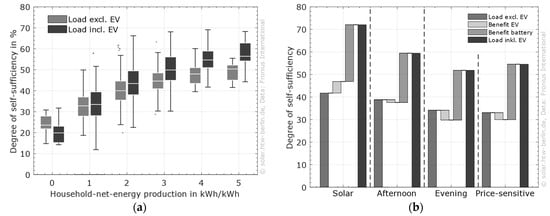

3.3. Degree of Self-Sufficiency

Section 3.2. provides a detailed analysis of the solar contribution to EV charging. In this section, a more detailed look is taken at the household load, as well as at the total load, by analyzing the degree of self-sufficiency. For better comparability of different households, the solar output has been normalized to the load (e.g., [30]). A value of one indicates net-zero consumption; i.e., the annual solar production is equal to the consumption of the household. A value of two indicates that the energy produced is twice the amount consumed. Note: Because consumption and solar production do not always coincide, the household could still be using power from the grid.

Figure 14 shows the degree of self-sufficiency as a function of net household energy production. Light gray indicates the base case without an EV and dark gray with an EV. Since only a few households (n = 11) exceed a net household energy production of five, the above values are neglected, as the boxplot would not be meaningful at all.

Figure 14.

(a) Degree of self-sufficiency correlated with household net energy production incl. and excl. EV (n = 722). (b) Median change in degree of self-sufficiency by an EV and a stationary battery sorted by clustered households with a stationary battery (n = 357). Solar n = 242; afternoon n = 67; evening n = 27; price-sensitive n = 21. Data: Fronius International.

As the available PV energy increases, the degree of self-sufficiency also increases, until a saturation point is reached. This saturation is determined by the temporal overlap of load and generation. This can be seen for the boxes without an EV, between 4 kWh/kWh and 5 kWh/kWh. The electric vehicle increases the load by about one third on average. Thus, the additional supply of the electric vehicle reduces the surplus of solar energy, but this additional load can be managed to potentially increase the time overlap of load and generation. Consequently, the charging behavior can either reduce or increase the degree of self-sufficiency. On average, it decreases with net energy consumption, e.g., values below 1, and increases with net energy production, e.g., values above 2.

A closer look at the data shows that the increase strongly depends on the load profile, here analyzed by looking at the clusters mentioned in Section 3.1.3; see Figure 7b. Four bars are shown for each cluster in Figure 14b. The first bar shows the degree of self-sufficiency for the household load only. Second, the light gray bar represents the change with an EV. The third bar additionally shows the increase in self-sufficiency with stationary battery storage, while the dark gray bar sums up the previous bars.

Therefore, households that charge their vehicles using primarily solar energy increase their self-sufficiency by about 5 percentage points on average, due to the controlled charging of the electric vehicle. In particular, households that produce more than twice as much electricity as they consume benefit the most. Adjusting the charging behavior shifts about 6 percentage points of the total load to the daytime and 1.5 percentage points to summer. This increases the utilization of onsite PV energy by about 12 percentage points on average.

This is completely different for all other clusters, as the degree of self-sufficiency decreases with the addition of an EV. There is only a small decrease for households that charge mainly in the afternoon and those that are price-sensitive. Afternoon charging households shift their load by 3 percentage points to the daytime, but not seasonally.

Conversely, price-sensitive households tend to shift their EV charging to nighttime hours in response to low dynamic tariffs, thereby increasing their energy consumption during off-peak periods without solar energy.

The load shifts by 1.5 percentage points to the summer, indicating that these households are likely to charge more externally in winter. Households that charge in the evening and at night experience a net loss of about 5 percentage points in self-sufficiency due to the EV. The load does not shift significantly, but this still results in a 6-percentage-point increase in onsite solar energy consumption.

A battery increases the degree of self-sufficiency by decoupling generation and consumption over time. On average, a battery increases the level of self-sufficiency by about 24 percentage points. Not all households benefit equally from the battery. A total of 90% of households increase their self-sufficiency by more than 16 percentage points, but only 10% by more than 32 percentage points.

It also depends on the appliances used. Households with heat pumps increase their self-sufficiency by 19 percentage points on average, while households without heat pumps increase their self-sufficiency by 26 percentage points. Furthermore, households that charge in the evening and at night receive less benefit from the battery than those that charge at midday or in the afternoon. This can be explained by the overcompensation of the negative impact of the EV.

The sample shows that a household with a PV battery and an EV can be supplied by its own PV system by more than 56% on average. If solar-adapted charging is used, median values of more than 77% are possible. If a heat pump is used onsite, the self-sufficiency decreases but can still reach median values above 45% and up to 61% for optimized households.

4. Discussion

The discussion is structured into five sections. First, a summary of the influence of the parameters described in Section 3.1 and Section 3.2 is provided, including an explanation of the highest solar shares observed in the sample, which highlights the importance of techno-behavioral adaptation. Second, the effects of technical measures such as smart-controlled charging and battery integration are contextualized. The third section takes a closer look at the overall solar share of fully electrified households. Fourth, the limitations of this study are discussed. Finally, the discussion concludes with an outlook on further aspects to be analyzed.

4.1. Explanations for Highest Solar Share

Households with a high solar share, above 75% (n = 108), and the highest shares, above 85% (n = 78), for EV charging without a stationary battery were seemingly well adapted to solar energy. Compared to households with only 50% to 75% solar share, these high-performing households generate more solar energy on average and charge significantly less overall. This is plausible, since higher generation with lower consumption leaves more energy for flexibility, like smart charging.

Surprisingly, the number of charging events in all three groups still ranges between two and four days per week, with only a slight decrease for households with the highest solar shares. This reduction is likely linked to their lower total charged energy, but it is not statistically significant in multivariate analysis. The energy delivered per charging session remains largely consistent across the sample, with only a modest reduction for this subgroup.

A meaningful adaptation for the high performers might be to align with the seasonal and diurnal production patterns of PV. The highest shares can only be achieved if charging takes place during the day and if charging at home is seasonally adapted. This means that more energy is charged during summer than winter. This is supported by the lower share of heat pumps in this group, which compete for the limited solar energy available in winter. Households with the highest solar share have roughly half as many heat pumps as the reference group, which reduces their winter energy demand. This is surprising, since the solar energy produced between November and February is twice as high as the charged energy for high solar shares. In households with the highest solar shares, it is four times as high.

These descriptive findings are further supported by a binomial logistic regression analysis. The results confirm that behavioral factors related to the timing of charging—particularly daytime charging—exhibit the highest explanatory potential for achieving high solar shares. Indicators of seasonal adaptation, especially reduced charging during winter months, are also significantly associated with high performance, while the absolute amount of charged and produced energy plays a secondary but still significant role. Detailed statistical results are provided in the Appendix A.

This implies that diurnal adaptation and a larger PV system with sufficient energy production during the darker months are key to achieving the highest solar shares. Diurnal adaptation is feasible for many EV users, for example, when charging can be shifted to weekends, home-office days, or occasional trips by bike or public transport. In situations where further PV expansion is limited, dynamic electricity tariffs can provide an ecologically comparable alternative by incentivizing charging during periods of low grid carbon intensity. Nevertheless, the presence of a battery has a significant influence on the highest solar shares, providing additional flexibility that will be discussed in the next section

4.2. Smart Charging and Battery Storage

The evaluation confirms that dynamic charging is an effective measure for increasing the solar share, which is consistent with the statistically supported results reported in the Appendix A and confirms several simulation studies, e.g., [7,31]. Particularly it is most effective for households that frequently charge during daylight hours. Solar-adapted users can achieve substantial gains in solar share. Afternoon and price-sensitive clusters also benefit, though to a lesser extent, while evening charging patterns remain constrained by the absence of surplus PV power. Hence, the effectiveness of smart charging depends on the availability of PV surplus; without sufficient midday PV generation, controlled charging cannot increase the solar share, which explains why evening-dominant users benefit far less from dynamic charging strategies.

Stationary batteries provide complementary flexibility by buffering control deviations and extending solar utilization into evening hours. The largest gains are observed in households with evening charging behavior. Here, the storage increases the median solar share by 20 percentage points. However, the limited capacity of residential batteries restricts their ability to fully charge EV batteries. For households charging during the day, the overall gain of a stationary battery is comparatively smaller, around 8 to 10 percentage points. This is because these households can already align their charging with PV generation, so that the battery can only add a small amount of solar energy to the car. Even so, the stationary batteries still provide a considerable advantage in the winter months, when PV production is low and diurnal mismatches become more pronounced.

A conclusion from this analysis is that dynamic charging is a very useful feature, especially for those who charge frequently during the day. On the other hand, a stationary battery can compensate for a lack of flexibility if charging is often performed in the evening hours. The maximum charge power should therefore consider the limitations of the battery. However, even for late-charging households, it is worth adapting to the available solar power to save costs, e.g., on weekends, so it can be concluded that dynamic charging is a must. These findings support the hypothesis that both behavioral alignment and technical optimization are required to maximize local renewable integration in EV charging. They imply that policy measures promoting smart charging could be as effective as large batteries in households.

4.3. Solar Share of Fully Electrified Household

Besides EV charging, the dataset is particularly interesting as it reveals real-world solar shares of fully electrified households. The solar share could be directly associated with savings of grid energy and related costs and is the economic driver for residential PV systems.

The data reveals that more than 50% of the households with an EV can cover around 46% of their total demand with solar energy, and this rate rises to a median of more than 73% when a battery is included. This is roughly 10% higher than expected for comparable households without an EV [30]. However, it can be explained by the fact that these households not only shift EV charging toward sunny hours but also adjust the operation of household appliances accordingly [24].

Households equipped with both EV and a stationary battery rely on the grid for only one quarter of their demand. However, this residual demand often occurs during high-load periods, such as winter periods with low PV energy and empty batteries. Current tariff structures in Germany, which levy grid fees exclusively on energy consumption, therefore provide little incentive to relieve or refinance the grid [32].

A more balanced picture emerges for fully electrified households with an additional heat pump: their median demand doubles compared to households without an EV or heat pump but is largely compensated by PV generation and battery storage. Notably, 10% of these households supply more than 75% of their demand from solar energy, typically with large PV systems exceeding 20 kW and batteries larger than 15 kWh. This allows the owners to power their heat pump by local solar energy under cold conditions as well and to provide sufficient flexibility to bridge low-irradiance days. With declining battery costs, such configurations are likely to become more common in Germany, as trends already show [33]. Nevertheless, the grid consumption of those households shifts almost entirely to the winter season. This seasonal concentration challenges existing tariff structures. Furthermore, it leaves residential battery assets underutilized for the sunnier part of the year, as they are typically not fully discharged overnight. It is therefore essential to discuss strategies for activating these substantial storage capacities to provide effective grid relief.

4.4. Limitations

This limitation discussion highlights several critical aspects of the dataset and the study’s findings. First, the data were provided by a solar integrator, indicating a customer group with a likely affinity toward solar energy. This introduces bias, as more than 85% of households charge in alignment with solar availability. Similar patterns have been reported in surveys, such as those conducted by NOW GmbH, which show that EV users with PV installations are more willing to adapt charging to solar generation [2]. Nevertheless, the sample also includes households without solar-controlled charging, offering a contrasting perspective. Household equipment further suggests that the sample represents slightly higher-income groups, which is not fully generalizable but consistent with typical EV users during the study period [10].

Second, quality control during data preparation was standardized and manually checked but not automated, leaving potential for errors in individual datasets. Statistical evaluation mitigates this effect, but some influence remains. For example, minor classification bias cannot be ruled out, as data processing steps may have assigned heat pump status to more households than originally present in the raw data. While this does not affect the qualitative findings, it may slightly influence quantities where heat pumps are captured separately, as well as the absolute distribution of appliance types. Furthermore, charging clusters were identified using k-means, with the number of clusters reduced to improve interpretability. While this approach preserves major behavioral patterns, assignment of individual profiles is not always unequivocal, resulting in quantitative uncertainty.

Third, missing EV charging data represent a significant limitation. This includes both non-recorded and external charging. Non-recorded sessions were largely reconstructed, although not completely, but rely on certain algorithms to detect those charging events. External charging, such as at workplaces, remains unknown and is therefore excluded. Vehicles with low solar shares or low annual mileage may rely more on external charging. Consequently, the reported solar share refers only to home charging. As noted in Section 3.1.3, it is likely that 70% to 75% of total charging events are captured in the dataset [2,10,26].

Fourth, the statistical analyses are subject to several limitations. While the regression and correlation results identify robust associations, they do not allow causal inference, and some effects may be influenced by correlated behavioral and technical factors that cannot be fully disentangled within the available observational data. The reported effects are statistically supported at conventional significance levels, as shown by the regression and correlation analyses provided in the Appendix A. Besides that, a limitation is that statistical significance is partly driven by the relatively large sample size, so even small effect sizes may appear significant and should therefore be interpreted primarily in terms of their practical relevance

4.5. Outlook

Finally, the study addresses selected aspects but cannot comprehensively cover all relevant factors influencing solar-based EV charging. Seasonal effects, such as reduced charging during winter months and regional variation, are only briefly mentioned here and require further investigation. In addition, households equipped with heat pumps deserve particular attention, as the combined operation of PV systems, EV charging, and heat pumps may lead to high simultaneous load peaks and increased grid stress. While stationary batteries or vehicle-to-grid (V2G) concepts could mitigate these effects, their widespread deployment in European markets remains limited. It is clear that dynamic tariffs could change the value streams and change user behavior. A better understanding of the link between charging behavior, solar production, and dynamic tariffs would be insightful and needs to be investigated. Overall, future studies could build on the presented results by jointly analyzing solar share, charging flexibility, and grid impacts, thereby capturing additional dimensions of user behavior and system integration.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed the interaction of PV generation and EV charging based on a large real-world monitoring dataset. After describing the dataset, an initial analysis of the data statistics showed expected biases typically found in EV surveys, for example, a greater prevalence of high energy demand, heat pumps, and mobility patterns associated with higher-income groups. Four dominant charging clusters were identified: Solar adapted, afternoon and evening charger and price sensitive drivers.

The analysis showed that the share of solar energy for charging and load contribution (degree of self-sufficiency) varies within a certain range. Several factors contributing to high solar energy shares have been identified. Both seasonal and diurnal adjustments were found to have a significant influence. While a stationary battery can increase the flexibility of diurnal adaptation, seasonal adaptation has been found in two ways: first, by increasing the production of solar energy even in the darkest month, and second, by suspended charges at home during the winter months. Solar-oriented charging proved essential, increasing the solar share by roughly 25 percentage points compared to uncontrolled charging. Since the degree of self-sufficiency is directly influenced by the solar share of the charged energy, it decreases if the proportion of solar energy in the EV is low compared to the household load. As the data show, a stationary battery can overcompensate for this to a certain degree but reduces the possible degree of self-sufficiency significantly.

The findings highlight the importance of solar-adapted charging strategies for households aiming to maximize PV utilization and self-sufficiency. Installers and energy advisors can use these insights to optimize PV sizing, battery integration, and charging configurations. Policymakers and grid operators benefit from empirical evidence on real-world charging behavior, which can support the design of smart-charging incentives and grid-friendly tariff structures.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://solar.htw-berlin.de/studien/solares-laden-von-elektrofahrzeugen/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B., N.O. and V.Q.; methodology, J.B. and N.O.; software, J.B. and N.O.; validation, J.B. and N.O.; formal analysis, J.B.; investigation, J.B. and N.O.; resources, J.B. and N.O.; data curation, J.B. and N.O.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.; writing—review and editing, V.Q. and L.M.; visualization, J.B. and N.O.; supervision, V.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Protection, grant number 03EI3039A.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from Fronius International and are available form Joseph Bergner with the permission of Fronius International.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank Fronius International for their data contribution. Furthermore, we thank our project partners from Fraunhofer ISE and ADAC.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AC | Alternating Current |

| ADAC | Allgemeiner Deutscher Automobil-Club (lit. ‘General German Automobile Club’) |

| BAT | Battery |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DoU | Degree of Urbanization |

| DACH | Germany, Austria, and Switzerland region (Deutschland, Österreich, Schweiz) |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| EVSE | Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment, EV charger |

| HP | Heat Pump |

| ISE | Institute for Solar Energy Systems |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| SOC | State of Charge |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Statistical Analyses—Kendall’s Tau Correlation Analysis

To complement the descriptive analysis, a non-parametric correlation analysis was conducted to assess the monotonic relationships between the solar share of EV charging and relevant technical and behavioral variables. Kendall’s τ was selected due to non-normal distributions, the presence of ordinal variables (e.g., charging shares), and binary indicators (e.g., presence of a battery or a heat pump).

The analysis was performed separately for households with and without stationary battery storage. Correlation coefficients and corresponding p-values are reported to indicate direction and relative strength of associations. Given the large sample size, statistical significance is interpreted with caution; emphasis is placed on the magnitude and consistency of effects rather than on p-values alone.

Across both subsamples, the strongest associations are observed for behavioral variables related to charging time, particularly the share of daytime charging, while winter-related variables consistently show negative associations with the solar share of EV charging. These findings support the interpretation that temporal alignment between charging behavior and PV generation is more influential than absolute energy quantities.

Table A1.

Kendall’s tau correlation between solar share of EV charging and explanatory variables (without stationary battery, n = 784).

Table A1.

Kendall’s tau correlation between solar share of EV charging and explanatory variables (without stationary battery, n = 784).

| Variable | Kendall’s τ | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime share | 0.603 | <1 × 10−99 | Very strong positive association. Charging during daylight hours is the dominant behavioral driver of high solar shares. |

| Winter share | −0.319 | <1 × 10−40 | Strong negative association. A higher share of winter charging substantially limits solar utilization. |

| EVSE energy in November, December and January | −0.312 | <1 × 10−39 | Strong negative association. High charging demand during low-PV months strongly reduces achievable solar shares. |

| PV energy | 0.302 | <1 × 10−36 | Moderate positive association. Higher PV generation supports higher solar shares, but less strongly than charging behavior. |

| Energy per charge | −0.202 | <1 × 10−17 | Moderate negative association. Larger charging sessions reduce temporal alignment with PV generation. |

| EVSE energy | −0.201 | <1 × 10−16 | Moderate negative association. Higher total charging demand lowers achievable solar shares. |

| Binary HP | −0.109 | <0.001 | Weak negative association. Heat pumps slightly reduce solar shares due to increased winter electricity demand. |

Table A2.

Kendall’s tau correlation between solar share of EV charging and explanatory variables (without stationary battery, n = 781).

Table A2.

Kendall’s tau correlation between solar share of EV charging and explanatory variables (without stationary battery, n = 781).

| Variable | Kendall’s τ | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime share | 0.576 | <1 × 10−99 | Very strong positive association. Daytime charging remains the key determinant even in the presence of battery storage. |

| Winter share | −0.347 | <1 × 10−47 | Strong negative association. Seasonal mismatch remains a major limitation despite additional flexibility. |

| EVSE energy in November, December and January | −0.345 | <1 × 10−46 | Strong negative association. High winter charging demand continues to constrain solar utilization. |

| PV energy | 0.327 | <1 × 10−42 | Moderate positive association. PV generation becomes more relevant when combined with storage. |

| Binary battery | 0.230 | <1 × 10−14 | Moderate positive association. Stationary batteries increase flexibility and enable higher solar shares. |

| EVSE energy | −0.222 | <1 × 10−20 | Moderate negative association. Higher overall charging demand still reduces achievable solar shares. |

| Energy per charge | −0.202 | <1 × 10−17 | Moderate negative association. Large charging sessions remain disadvantageous for solar alignment. |

| Binary HP | −0.143 | <0.001 | Weak negative association. Heat pumps slightly reduce solar shares. |

| Frequency of charging | −0.050 | 0.038 | Negligible effect. Statistically significant due to large sample size, but practically irrelevant. |

Appendix A.2. Statistical Analyses—Logistic Regression for High Solar Shares (>85%)

In addition to the correlation analysis, binomial logistic regression models were estimated to identify factors associated with achieving very high solar shares of EV charging. The dependent variable is defined as a binary indicator equal to one if the solar share exceeds 85% and zero otherwise. Separate models were estimated for households with and without stationary battery storage.

The regression models include technical characteristics (e.g., PV power, winter PV generation), charging behavior metrics (e.g., daytime and winter charging shares), and household characteristics (e.g., presence of a heat pump or battery). Coefficient estimates indicate the direction and relative strength of effects, while p-values are reported to assess statistical relevance.

The regression results largely confirm the correlation analysis and the descriptive findings presented in the main text. In both models, daytime charging behavior exhibits the strongest positive association with achieving very high solar shares, whereas charging during winter months and high winter charging energy significantly reduce the likelihood of high performance. The presence of a stationary battery shows a positive and statistically significant effect, indicating additional flexibility, but does not outweigh the importance of charging behavior.

Overall, the regression analysis increases confidence that the observed patterns are not driven by visual inspection alone, but reflect robust relationships between charging behavior, seasonal effects, and solar utilization.

Table A3.

Logistic regression of high solar share without battery (>85%, n = 784).

Table A3.

Logistic regression of high solar share without battery (>85%, n = 784).

| Variable | Estimate | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVSE energy | 0.002046 | 0.0275 | Positive effect; more energy charged via the EVSE slightly increases the probability of high solar share |

| PV energy in November, December, and January | 0.002120 | 0.0410 | Positive effect; higher PV generation in winter increases probability of high solar share |

| EVSE energy in November, December, and January | −0.010768 | 0.00436 | Negative effect; higher winter EVSE charging reduces probability of high solar share |

| Daytime share | 55.557 | 2.23 × 10−6 | Strong positive effect; daytime EVSE charging strongly increases probability of high solar share |

| Winter share | 3.5382 | 0.3871 | Not significant |

| PV power | 0.052607 | 0.6273 | Not significant |

| Binary HP | 0.51092 | 0.4205 | Not significant |

| Energy per charge | −0.14853 | 0.1644 | Not significant |

| Frequency of charging | −0.39585 | 0.4842 | Not significant |

| PV energy | −2.7724 × 10−5 | 0.8472 | Not significant |

| Ratio PV/EV in November, December, and January | −0.005692 | 0.7822 | Not significant |

Table A4.

Logistic regression of high solar share with battery (>85%, (n = 781).

Table A4.

Logistic regression of high solar share with battery (>85%, (n = 781).

| Variable | Estimate | p-Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| EVSE energy | 0.001754 | 0.0292 | Positive effect; more EVSE energy slightly increases probability of high solar share |

| Daytime share | 33.178 | 4.02 × 10−8 | Strong positive effect; daytime EVSE charging increases probability of high solar share |

| Winter share | 9.4011 | 0.0374 | Positive effect; winter EVSE activity increases probability |

| EVSE energy in November, December, and January | −0.014699 | 1.27 × 10−5 | Negative effect; higher winter EVSE charging reduces probability |

| Ratio PV/EV in November, December, and January | 0.16411 | 0.00330 | Positive effect; higher winter PV/EVSE ratio increases probability |

| Binary battery | 2.1851 | 0.00590 | Positive effect; presence of a battery increases probability |

| Energy per charge | −0.091741 | 0.3769 | Not significant |

| Frequency of charging | 0.49981 | 0.3333 | Not significant |

| PV power | −0.075835 | 0.4946 | Not significant |

| Binary HP | −0.73286 | 0.1852 | Not significant |

| PV energy | 0.000225 | 0.1252 | Not significant |

References

- Internation Energy Agency IEA (Ed.) World Energy Outlook 2023; Internation Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- National Centre for Charging Infrastructure (Ed.) Einfach Zuhause Laden Studie Zum Ladeverhalten von Privatpersonen Mit Elektrofahrzeug und Eigener Wallbox—(engl: Easy Charging at Home Study on the Charging Behavior of Private Individuals with Electric Vehicles and Their Own Wallboxes); NOW GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2024; Available online: www.nationale-leitstelle.de (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- Gezelius, M.; Mortazavi, R. Effect of Having Solar Panels on the Probability of Owning Battery Electric Vehicle. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADAC (GERMAN AUTOMOBILE CLUB). ADAC Survey on EV 2024. Available online: https://www.adac.de/fahrzeugwelt/magazin/e-mobilitaet/elektroauto-studie/ (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- KfW (German Promotional Bank) (Ed.) KfW-Energiewendebarometer 2024 (Energy Transition Opinion Survey). 2024. Available online: https://www.kfw.de/PDF/Download-Center/Konzernthemen/Research/PDF-Dokumente-KfW-Energiewendebarometer/KfW-Energiewendebarometer-2024.pdf (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- ISEA RWTH Aachen University. Mobility Charts. Available online: https://www.mobility-charts.de/?page_id=531 (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Martin, H.; Buffat, R.; Bucher, D.; Hamper, J.; Raubal, M. Using rooftop photovoltaic generation to cover individual electric vehicle demand—A detailed case study. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 157, 111969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachrizal, R.; Munkhammar, J. Improved Photovoltaic Self-Consumption in Residential Buildings with Distributed and Centralized Smart Charging of Electric Vehicles. Energies 2020, 13, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, T.; Dossow, P.; Morlock, E. Revenue opportunities by integrating combined vehicle-to-home and vehicle-to-grid applications in smart homes. Appl. Energy 2022, 307, 118187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USCALE (Ed.) Private Charging Studie. Stuttgart. 2023. Available online: https://uscale.digital/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/Private-Charging-Study-2024-Auszug.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Kim, J.D. Insights into residential EV charging behavior using energy meter data. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashmi, M.U.; Gioffrè, D.; Nagels, S.; Van Hertem, D. Analyzing electric vehicle, load and photovoltaic generation uncertainty using publicly available datasets. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Lee, E.; Kim, J. A dataset for multi-faceted analysis of electric vehicle charging transactions. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergner, J.; Orth, N.; Meissner, L.; Quaschning, V. Solar charging—Lessons learned from field observation. In Proceedings of the 38th International Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exhibition (EVS38), Gothenburg, Sweden, 15–18 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Orth, N.; Bergner, J.; Salehi, S. Solares Laden von Elektrofahrzeugen; HTW Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2025; Available online: https://solar.htw-berlin.de/studien/solares-laden-von-elektrofahrzeugen/ (accessed on 22 January 2026).

- co2online. Information Portal for Comparing Household Electricity Consumption—Stromspiegel. Available online: https://www.stromspiegel.de/ (accessed on 14 January 2026).

- Kraschewski, T.; Brauner, T.; Heumann, M.; Breitner, M.H. Disentangle the price dispersion of residential solar photovoltaic systems: Evidence from Germany. Energy Econ. 2023, 121, 106649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]