Abstract

The electrification of transport is rapidly reshaping power distribution networks, introducing new technical, regulatory, and operational challenges for Distribution System Operators (DSOs). This article presents an international review of electromobility integration strategies, analyzing experiences from Europe, Canada, Australia, and Greece. It examines how DSOs address grid impacts through smart charging, vehicle-to-grid (V2G) services, and demand flexibility mechanisms, alongside evolving regulatory and market frameworks. European initiatives—such as Germany’s Energiewende and the UK’s Demand Flexibility Service—demonstrate how coordinated planning and interoperability standards can transform electric vehicles (EVs) into valuable distributed energy resources. Case studies from Canada and Greece highlight region-specific challenges, such as limited access in remote communities or island grid constraints, while Australia’s high PV penetration offers unique opportunities for PV–EV synergies. The findings emphasize that DSOs must evolve into active system operators supported by digitalization, flexible market design, and user engagement. The study concludes by outlining implementation barriers, policy implications, and a roadmap for DSOs.

1. Introduction

The electrification of transport is a central pillar of global decarbonization strategies. As EV adoption accelerates, DSOs face growing challenges related to grid capacity, voltage quality, and the integration of charging infrastructure. Initially viewed as a low-voltage phenomenon, electromobility now affects medium- and high-voltage levels, particularly as fast-charging hubs and heavy-duty transport become electrified.

Different regions have adopted diverse electromobility strategies shaped by unique regulatory frameworks, technological maturity, geography, and social acceptance. This article compares key experiences in Europe, Canada, Australia, and Greece, identifying best practices and the remaining challenges. To enhance clarity and analytical rigor, the revised version incorporates an expanded methodology section, clearly defined evaluation criteria, and cross-case synthesis previously missing from the manuscript.

2. Methodology

This section outlines the methodology underpinning the international comparative analysis.

2.1. Literature Review Approach

A structured literature review was conducted between January and September 2025. Sources included:

- Peer-reviewed journals: IEEE [1,2]; World Electric Vehicle Journal (EVJ) [3]; Energies [4];

- Regulatory documents: the EU Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) §14a [5]; the German Energy Industry Act (EnWG) [6], the Canadian Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandates [7]);

- Official data portals: the International Energy Agency (IEA) [8,9]; European Alternative Energy Fuel Observatory (EAFO) [10], and Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) [11];

- DSO [12] and TSO [13] publications;

- Major demonstration project reports: e.g., Powerloop [14], ShareQ [15] and ARENA V2G trials [16].

The purpose of this review was to gather consistent and comparable information on electromobility integration strategies, evaluate technological maturity, and evaluate how different regulatory ecosystems shape DSO practices.

2.2. Methodological Approach

The methodological approach adopted in this review combines structured literature screening, defined selection criteria, and a multidimensional evaluation framework to allow a coherent and comparable analysis of electromobility integration strategies in different countries. Identification of relevant regions and case studies was guided by the need to capture a broad spectrum of technical, regulatory, and geographical conditions that influence DSO strategies. Countries were selected when they demonstrated significant developments in EV adoption, the presence of documented smart charging or V2G initiatives, unique grid characteristics, or substantial regulatory evolution. This approach ensured that mature markets (such as several European countries) were evaluated alongside emerging contexts such as remote communities in Canada, Greece’s island systems, and Australia’s high-PV distribution grids. The analysis relied exclusively on reliable and traceable sources, including peer-reviewed scientific publications, official reports from regulatory bodies and system operators, data sets from international agencies, and documentation from large-scale demonstration projects. Priority was given to sources that provide transparent methodologies, recent data, or measurable indicators of the impacts of the EVs on the grid. To maintain consistency across case studies, quantitative information (e.g., EV penetration, charging infrastructure density, peak demand impacts) was cross-validated using multiple independent datasets whenever possible. The comparative evaluation was based on four analytical dimensions. The technical dimension examined hosting capacity challenges, voltage quality, grid reinforcement needs, and the maturity of smart charging and V2G implementations. The regulatory dimension assessed the alignment of national frameworks with flexibility markets, interoperability standards, and DSO responsibilities. The economic dimension evaluated investment requirements, tariff design, and incentive structures that influence consumer charging behavior. The operational dimension considered real-time visibility, DSO–CPO (Charge Point Operator) collaboration mechanisms, and user participation in flexibility schemes. Together, these elements form a unified methodological basis that supports the structured comparison of international electromobility practices and the identification of common and region-specific challenges.

3. Overview of DSO Strategies and Regulatory Frameworks for EV Charging

DSOs are implementing various strategies for electromobility integration, characterized by a segmented approach due to individual use cases and varying locations.

- Charging Pattern Strategies: This includes the rise of home charging (smart chargers with time-of-use tariffs to shift evening peaks), workplace charging (load management systems, solar PV integration), and fast charging (in robust grid areas with energy storage for demand buffering).

- Technical Mitigation Measures: Smart charging involves vehicle-to-grid (V2G) and unidirectional charging with grid signal modulation. Demand response programs enroll EVs with peak reduction incentives. Battery integration near high-demand charging hubs provides energy storage. Grid reinforcement includes predictive modeling for transformer and line upgrades and dynamic line rating with real-time monitoring. For example, the UK National Grid Energy System Operator (NESO) Demand Flexibility Service (DFS) cut more than 3300 MWh of peak electricity use across 22 events in winter 2022/23 [13].

- Collaboration Models: DSO-Charge Point Operator (CPO) partnerships involve data sharing on grid capacity, charger locations, and usage. Standard interfaces, such as CPO adoption, facilitate seamless integration. To improve the standardization process and the seamless EV integration, NESO supports a few pilot projects like the V2G Powerloop trial (135 households, enrolled capacity <1 MW). This project aims at documenting and testing in the field the implementation of the smart-charging/V2G flexibility mechanisms. The trial demonstrated notable consumer and system-level benefits. Participating households achieved annual savings of up to £180 compared to smart charging and £840 compared to unmanaged charging on a flat tariff (adjusted for 10,000 miles/year). At the system level, V2G-enabled EVs were shown to provide a lower-cost option to balance electricity demand than current balancing mechanism (BM) alternatives, reducing overall consumer bills and reliance on carbon-intensive fuels. The trial results also confirmed the technical capacity to aggregate domestic V2G assets, with charge and discharge patterns successfully coordinated by the Electricity National Control Center (ENCC) to meet balancing requirements while maintaining user charging preferences. This demonstrated the potential of aggregated EVs to satisfy BM data requirements and respond dynamically to instructions. Finally, the study highlighted the viability of future entry into BM, identifying current barriers such as minimum thresholds, aggregation rules, and metering standards. While most are short-term and expected to ease with market growth, operational metering standards remain a critical blocker, requiring regulatory attention to unlock the full value of V2G resources [14].

- Renewable Energy Integration: Solutions include battery storage at charging stations to store excess renewable energy. Advanced forecasting aligns renewable generation with EV demand. Cost management is supported by public funding and carbon credits for renewable-powered charging. The V2G synergies use EVs as flexible loads. Germany’s “Energiewende” (Germany’s national strategy for transitioning to a low-carbon, nuclear-free energy system) exemplifies EV charging integrated with wind and solar through smart grids and V2G pilots [17]. Within the framework of the German Energiewende, V2G technologies are increasingly recognized as a critical element of the future power system’s flexibility. Recent regulatory initiatives, such as the draft Market Integration of Storage and Charging Points (MiSpeL), seek to place bidirectional charging at the same level as stationary battery storage, thus granting V2G-enabled electric vehicles access to remuneration and market participation opportunities comparable to other storage assets [18]. In parallel, amendments to the Energy Industry Act (§ 14a EnWG) enable DSOs to modulate charging loads during periods of grid stress, embedding EVs within broader demand-side management strategies [6]. These measures are aligned with Germany’s overarching strategy to improve grid flexibility through a portfolio of resources, including interconnections, storage, demand-side response, and digitalized grid management [19]. Modeling studies suggest that even moderate penetration of V2G can deliver substantial system-level benefits, such as reducing the need for stationary storage, lowering congestion and redispatch costs, and improving integration of variable renewables [3], [20]. For consumers, V2G offers additional economic incentives when coupled with dynamic tariffs or on-site generation, with the potential for significant savings in electricity costs [21]. Nonetheless, the realization of these benefits depends on several enabling conditions, including sufficient deployment of V2G-capable vehicles and charging infrastructure, consumer willingness to participate in flexible charging schemes, and clear regulatory frameworks for metering, remuneration, and market access [6,18] Operational challenges, such as communication standards and aggregation mechanisms, must also be resolved to ensure reliable integration into the balancing system [19]. Taken together, the German energy transition foresees V2G not only as a niche innovation, but also as an integral contributor to cost-effective system flexibility, reduced reliance on fossil resources, and the secure integration of renewable energy at scale.

For an optimal market structure and regulatory framework, hybrid models that combine competitive and regulated elements are emerging. Competitive elements drive innovation and cost reduction and cater to high-demand areas, while regulated elements prevent market failures in rural and low-income areas and ensure grid integration. A clear delineation between these approaches is needed. Grid stability rules and incentives include dynamic Time-of-Use (ToU) tariffs and smart charging incentives (subsidies for V2G and demand response capable chargers). Grid upgrades involve cost-sharing mechanisms between DSOs, CPOs, and EV users, along with a fast-track permitting procedure for accelerated deployment. California’s rebate programs (e.g., CALeVIP [22]) and the utility time of use (ToU) rates [23] support the build-out toward the state’s goal of 250,000 chargers by 2025 [24].

Key regulatory framework pillars include:

- Interoperability: Protocols like OCP and ISO15118-20:2022: Road vehicles—Vehicle to grid communication interface are crucial for EVs [25].

- Affordability: Regulating pricing and providing subsidies for low-income users.

- Accessibility: Ensuring minimum charger density requirements and ADA-compliant designs.

- Data transparency: Real-time sharing of availability, pricing, and status.

Global success models include Norway, where EVs accounted for more than 90% of new car sales in 2024 [8], supported by long-running purchase-tax (VAT) exemptions [10]. Another example is China; rapid EV growth is underpinned by the national plan (NEV 2021–2035 [9]), generous tax incentives [26], a dual-credit mandate [27], and state-supported expansion of charging infrastructure [8]. The following sections provide additional detail and discussion on these country-specific case studies.

4. Grid Integration of Sustainable Transport: A European Perspective

According to the European Commission, achieving sustainable transport requires mobility solutions that are user-centric, affordable, accessible, healthy, and clean, strengthening the overall transition towards climate neutrality [28]. Electromobility plays a pivotal role in this transition, driven primarily by environmental concerns and the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Although EVs were initially expected to affect mainly low-voltage networks, the rapid growth of high-power charging infrastructure—frequently connected to medium- or even high-voltage levels—now means that EV integration directly influences the entire electricity system, including transformer loading, voltage stability, cable capacity, and potential imbalances during charging.

To address these challenges, Working Group 1 (WG1) of the European Technology and Innovation Platform for Smart Networks for Energy Transition (ETIP SNET) [29] developed a position document exploring how the integration of sustainable transport, particularly EVs, can accelerate the transition to a zero-emission, climate-neutral European energy system. WG1 highlights that transportation electrification is closely linked to power system flexibility and the adoption of renewable energy. EVs support decarbonization by reducing tailpipe emissions and simultaneously introducing new sources of flexibility to the power system. Smart charging enables real-time modulation of charging demand to accommodate higher shares of renewable generation, while V2G technologies allow EVs to inject electricity back into the grid, helping to balance supply and demand. Battery energy storage systems (BESS), including stationary storage and second-life EV batteries, also represent essential enablers of EV-grid integration. They can mitigate peak loads, support voltage control, and complement V2G strategies by absorbing excess renewable generation and releasing it during high-demand periods. Hybrid configurations that combine batteries with other fast-response technologies—such as flywheels—offer enhanced operational flexibility and cost efficiency. As the EVs penetration increases, integrating charging infrastructure into the electricity grid presents growing planning and operational challenges. DSOs must anticipate future charging demand, forecast behavioral patterns, and plan for necessary upgrades—particularly in constrained areas. Uncoordinated charging infrastructure deployment can lead to transformer overload, excessive voltage drops, or congestion in the distribution feeders. Therefore, coordinated siting and sizing of charging stations are essential to ensure system reliability and minimize reinforcement costs.

Close collaboration of CPOs and DSOs is critical in this context. Data sharing on grid capacity, usage patterns, and planned infrastructure deployments helps align grid upgrades with electromobility rollout. Regulatory frameworks increasingly emphasize standardized communication protocols and interoperable systems—both prerequisites for smart charging and automated grid-supportive behaviors. A strong policy foundation supports Europe’s electromobility strategy. Key regulations include the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR) [5] and recent Industrial Action Plans, promote investments in charging infrastructure, encourage grid modernization, and support flexibility services [30].

However, challenges remain with respect to the public acceptance of V2G and the use of second-life batteries. Some users are reluctant to hand over control of their assets to DSOs or aggregators. Technological advances that consider the entire energy system (from transmission and distribution networks to active customer participation) are crucial to preventing instability, particularly given the decreasing availability of reactive power caused by increased distributed generation. Research must focus on integrated solutions, supported by coherent policy frameworks and market incentives, to unlock the full potential of electromobility and grid convergence.

5. Electromobility in the Canadian Context: Managed Charging, Flexibility, and Remote Access

Canada has committed to an ambitious national decarbonization strategy that mandates 100% zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) sales by 2035, with interim targets of 20% by 2026 and 60% by 2030 [7,31]. Federal financial incentives have played an important role in supporting early EV adoption; however, the iZEV rebate program was paused in January 2025 due to budget exhaustion [32]. EV uptake across the country remains highly uneven. Provinces such as British Columbia and Quebec continue to lead adoption with rates exceeding 20%, while regions such as Alberta and parts of the Atlantic provinces remain closer to 5–6%. Canada’s national averages—approximately 11.7% of EV sales in 2023 and 14.6% in 2024—remain significantly lower than those of the leading European markets, where adoption varies from 25–30% (France, UK, The Netherlands) to more than 90% in Norway. This regional variability is reflected in the deployment of the charging infrastructure. Urban centers benefit from relatively dense charging networks, while rural, northern, and Indigenous communities continue to experience limited or unreliable access [33]. Although several provinces have launched initiatives to bridge these gaps—such as British Columbia’s “Electric Highway”—many remote communities still lack year-round coverage. Geospatial analysis confirms that accessibility challenges persist in sparsely populated regions, often exacerbated by climatic constraints and long travel distances [31].

The growing penetration of EVs places increasing pressure on distribution networks. DSOs report concerns related to peak demand growth, transformer loading, voltage stability, and coincident heating–charging peaks during winter. For instance, one major DSO serving Edmonton shifted from constructing a new substation roughly every five years to building one every year, largely due to anticipated EV-driven load increases. These challenges demonstrate a clear need for enhanced real-time visibility, advanced load-forecasting tools, and region-specific planning methodologies capable of accounting for Canada’s diverse climate and geography.

The institutional and regulatory diversity further shapes the electromobility landscape. In Alberta, where the electricity system operates under an unbundled market model with numerous small distribution utilities, DSOs face different constraints than in provinces with vertically integrated structures. Despite these differences, DSOs across the country are investing in hosting capacity estimation, disaggregated consumption analytics, and distributed energy resource planning. However, barriers persist, particularly the absence of a clear regulatory framework for flexibility services and the prohibition or strict limitation of DSO ownership and operation of energy storage systems, which restricts their ability to deploy innovative grid support solutions.

Given Canada’s vast spatial diversity and harsh winter conditions, the development of electromobility requires strong coordination among regulators, DSOs, municipalities, Indigenous governments, and technology providers. Interoperability standards and cybersecurity requirements must be strengthened to support automation, while climate-adjusted modeling remains essential to ensure reliable operation in extreme cold. Table 1 summarizes the tools and methodologies used in Canada to support EV integration [28].

Table 1.

Tools and Methodologies to Support EV Integration.

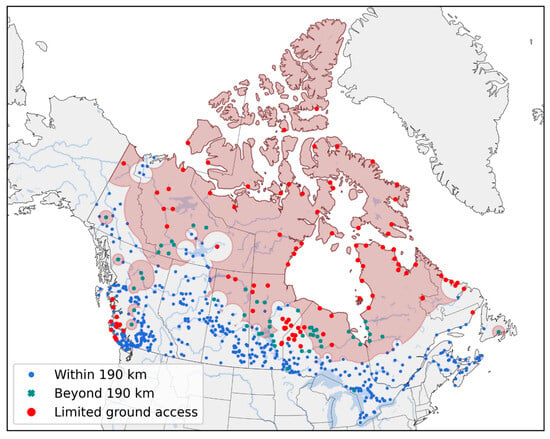

A consistent challenge across the country is the lack of a nationally coordinated charging strategy. While provincial programs have expanded access, a unified national approach remains necessary to ensure equitable coverage. Figure 1 highlights the disparities in charging availability, particularly in rural and Indigenous regions [2].

Figure 1.

Infrastructure-Restricted EV Charging Access in Canada. Regions highlighted in red correspond to areas where inadequate EV charging infrastructure significantly constrains EV adoption (Source: [2]).

For remote communities relying on isolated microgrids and diesel generation, integrating EV charging with distributed energy resources (DERs), energy storage, and hybrid microgrids is critical. Table 2 provides a comparison of EV charging characteristics between Canada and Europe, highlighting key differences in adoption rates, infrastructure density, charging standards, and regulatory maturity.

Table 2.

EV Charging Comparison (source: [4]).

The Canadian experience illustrates that while the EV adoption can progress rapidly under supportive policy and market conditions, infrastructure readiness, climate resilience, and regulatory modernization remain decisive factors in ensuring a reliable and equitable integration of electromobility across diverse regions.

6. Electromobility in Greece: Island Testbeds

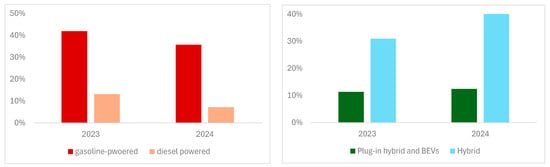

Greece has experienced a steady increase in EV adoption, reaching a market share of about 6.1% in the previous year. Public charging infrastructure has expanded rapidly, with more than 7600 publicly accessible charging points at roughly 3000 locations [34]; [35]. Updated national registries reported 6619 charging points at the end of 2024 [36] and 8561 by the third quarter of 2025, according to the statistics of the European Alternative Fuels Observatory (EAFO) statistics [10]. The national ecosystem of charging operators and e-mobility service providers continues to grow, including companies such as Joltie—founded in 2022 and already responsible for more than 500 charging points—supported through European Investment Bank financing [37], as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Vehicles share sales in Greece (source: [38]).

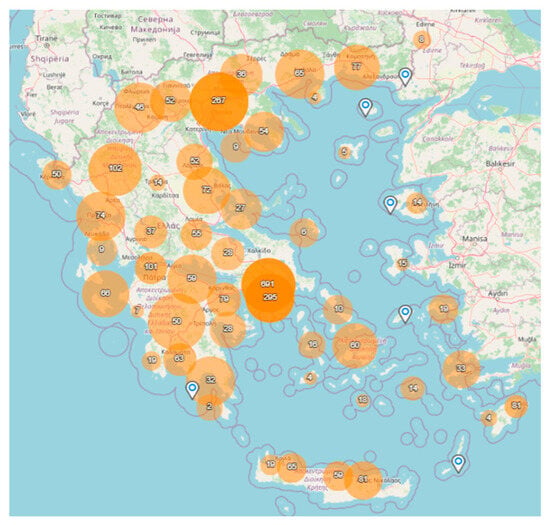

Most public chargers in Greece are AC chargers rated at ≤22 kW, representing approximately 81% of the installed base [39]. However, the deployment of high-power charging (HPC) infrastructure is accelerating, including stations rated at 350 kW and higher, following European market trends led by networks such as Ionity and manufacturers such as ABB [40,41]. Some Greek installations already achieve 360 kW [36]. This increasing diversity of charging power (from 3.3 kW household chargers to 350 kW HPC hubs [36] as illustrated in Figure 3), poses significant challenges for distribution grid planning and operation. This growth, coupled with a significant increase in charging power, raises concerns about grid impact.

Figure 3.

Charging Stations in Greece (Source: [42]).

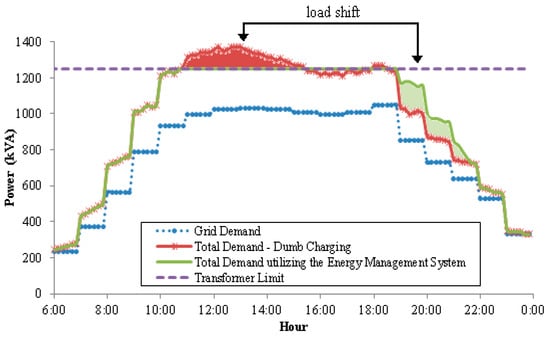

According to analysis from the International Transport Forum (ITF-OECD), if Greece wants to reach the fast-charging targets foreseen in the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation (AFIR), many Greek substations must be converted to higher peak load categories; this transformation requires significant reinforcements in the existing distribution grids [39]. The European Distribution System Operators (EDSO) association also warns of local congestion risks and voltage instability associated with ultrafast charging above 350 kW, reinforcing the need for proactive DSO coordination and smart charging [12]. ToU tariffs and controlled charging have shown a strong potential to shift demand away from peak periods, particularly during the summer season when grid constraints intensify [43], as illustrated in Figure 4 [43].

Figure 4.

Interaction of EV Charging with the grid (source: [44]).

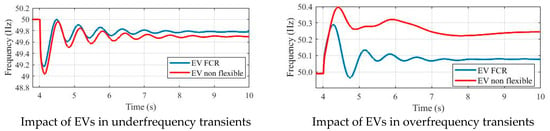

Greece has taken initial steps toward enabling flexibility services, with preliminary regulatory frameworks introduced in 2019. Several energy suppliers now offer electromobility-oriented tariffs (such as PPC BluePass, NRG InCharge, and Elpedison Drive Green Electricity) featuring incentives such as discounted home charging or bundled e-mobility packages [45,46,47]. However, a comprehensive regulatory framework for smart charging is still lacking, and flexibility markets are still under development. Greek islands—many of which remain isolated—serve as valuable testbeds for electromobility. The ShareQ project [15] demonstrated that intelligent management of charging capacity can prevent transformer overload and voltage deviations, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6 [48].

Figure 5.

Results of the ShareQ project (source: [48]).

Figure 6.

Frequency Containment Reserves (source: [48]).

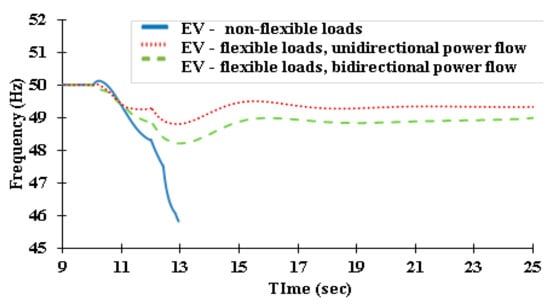

Simulations further revealed that uncontrolled charging can exacerbate frequency instability during system disturbances, while flexible EV loads can support frequency containment and prevent blackouts, as shown in Figure 7 [43].

Figure 7.

Grid’s frequency: Three phase short-circuit at a high voltage bus with simultaneous loss of two generation units connected at the same bus in Crete (simulation). (source: [43]).

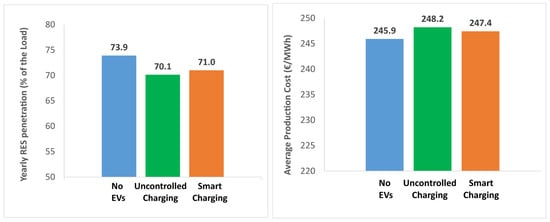

Initiatives such as the “Smart Island” program aim to achieve renewable energy penetration above 70% by integrating EVs, stationary storage, hybrid RES systems, and electric public transport, as illustrated in Figure 8 [46]. These projects provide replicable models for islanded systems and offer valuable insights into the interplay between EV charging, renewable generation, and local flexibility services.

Figure 8.

Astypalea: EVs and High RES penetration (source: [46]).

7. Electromobility in Australia: PV Integration and Unique Challenges

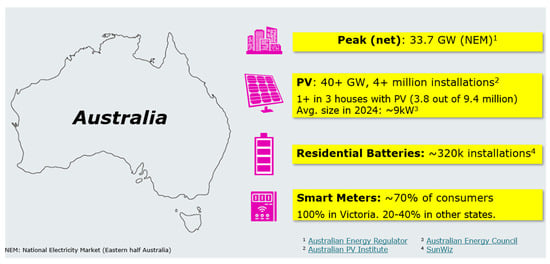

Australia has one of the highest rooftop PV penetration levels in the world, with more than one in three households operating residential solar systems. EV adoption remains comparatively low (only about 1% of the national light-vehicle fleet) due in part to historical policy barriers and limited vehicle availability. Recently, however, lower-cost EV imports from China have accelerated uptake, as shown in Figure 9 and as illustrated in the documents published by the Australian Energy Regulator [49], the Australian PV Institute [50] the Australian Energy Council [51] and in the Australian Batteries market report 2025 [52].

Figure 9.

Australian Context|Some Stats 2024/2025 (Sources: [49,50,51,52]).

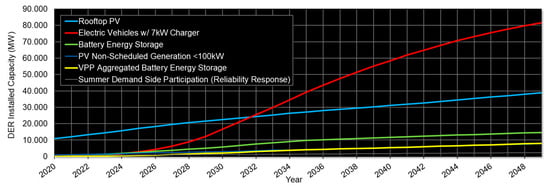

Even at current adoption levels, the EV integration interacts with the existing challenges caused by the high distributed PV generation. Daytime voltage rise, reverse power flows, and local congestion are common issues, while EV charging may intensify evening voltage drops and night-time feeder loading. The projections of the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) suggest significant future DER growth (Figure 10) [11], underscoring the need for coordinated distribution network planning.

Figure 10.

DER Installed Capacity Forecast (source: [11]).

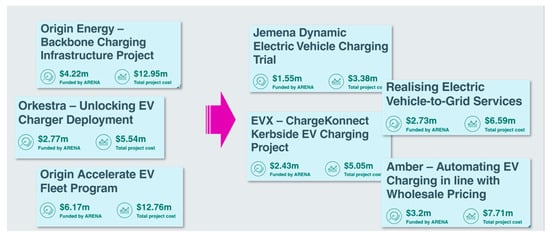

Residential charging (typically 3.7 to 7.4 kW) can substantially increase household evening peaks, although the aggregated coincidence factor is roughly 1 kW. Australian demonstration projects have evolved from simple infrastructure trials to sophisticated smart-charging and V2G pilots (Figure 11) [16].

Figure 11.

From infrastructure development to V2G (source: [16]).

Despite encouraging technical results, consumer willingness to participate in V2G remains modest, with greater potential in fleet and depot-based applications where charging schedules are more predictable. Structural challenges persist. Time-of-use tariffs designed by DSOs to influence charging behavior are often neutralized by retailers offering flat tariffs. DSOs also face difficulties in identifying EV connections at the feeder level due to limited data granularity. The variation in the standards of the curbside charging infrastructure complicates deployment, especially compared to European cities where uniform curbside charging is more common. Furthermore, widespread electrification policies—such as Victoria’s ban on new gas connections—will increase electricity demand, necessitating advanced demand-management strategies. Technologies that enable flexible PV exports may eventually facilitate flexible EV imports, allowing dynamic charging-limit controls. In practice, the most promising near-term bidirectional applications in Australia are Vehicle-to-Load (V2L) and Vehicle-to-Home (V2H), which enable backup power during outages and household load support. Large-scale V2G participation for system services remains limited due to high grid reliability, insufficient monetary incentives, and user preference to maintain control over charging.

8. Key Discussion Points

Several overarching themes emerge from the comparison of different electromobility integration strategies. Time-of-use tariffs are widely used to shift charging away from peak periods; however, they can unintentionally create secondary demand peaks when many users charge simultaneously during low-price windows. More dynamic or granular tariffs could mitigate this risk, but existing regulations restrict tariff innovation in several regions. Customer acceptance represents a major barrier to large-scale participation in V2G. Although empirical evidence suggests that battery degradation caused by V2G is minimal within warranty limits, many EV owners remain reluctant to relinquish control over charging unless compensated with clear, attractive incentives.

Interoperability remains another critical challenge. While current standards enable DSOs to manage bidirectional charging, DSOs often prefer to apply connection-level limits and rely on aggregators for behind-the-meter control due to liability concerns. Advances in inverter technology (particularly Volt/Var capabilities) offer promising voltage-regulation benefits even when PV output is low. Similarly, smart EV chargers provide valuable flexibility services, but their integration into grid-operation systems remains partial and fragmented.

The connection of the EV charging infrastructure to the distribution networks continues to be a major obstacle. Planning procedures must evolve to incorporate the flexibility potential of controlled charging and DER coordination. Close collaboration between DSOs and CPOs is essential for siting HPC chargers, managing feeder capacity, and ensuring local hosting-capacity adequacy.

International experiences demonstrate that there is no universal strategy for EV-grid integration. Geography, regulation, population density, DER penetration, and market structure significantly shape the design and impact of electromobility strategies. Nonetheless, widely applicable best practices include strong regulatory clarity, robust data-exchange frameworks, coordinated planning, and user-centric flexibility programs.

9. Cross-Case Synthesis, Policy Implementation Challenges for DSOs, and Conclusions

The international case studies examined—Europe, Canada, Greece, and Australia—demonstrate that electromobility integration challenges share common technical foundations while remaining deeply shaped by regional geographic, regulatory, and technological conditions. In all regions, DSOs face a similar set of core operational challenges, including peak load increases linked to uncoordinated charging, transformer loading issues, voltage deviations at the feeder level, and limited real-time observability of distribution networks. Smart charging, V2G functionality, and flexibility markets consistently emerge as essential mechanisms for mitigating these impacts. Interoperability standards such as ISO 15118 and coordinated DSO–CPO planning are universally required to unlock the flexibility benefits of EVs.

At the same time, the case studies reveal unique challenges and context-dependent solutions. Canada faces extreme climatic conditions and vast geographical disparities that limit charging accessibility in rural, northern, and Indigenous communities. The absence of a national flexibility framework and restrictions on DSO storage ownership further constrain innovation. Greece, particularly its non-interconnected islands, highlights the need for flexibility to maintain frequency stability and avoid transformer overloads. Microgrid-level strategies, hybrid RES–storage solutions, and controlled charging provide valuable insights for islanded or weak-grid contexts. Australia demonstrates how exceptionally high rooftop PV penetration reshapes EV–grid interactions, creating voltage rise and reverse power flow challenges not observed elsewhere. V2L and V2H applications currently hold more promise than large-scale V2G, owing to consumer preferences and high grid reliability. The European Union, through binding frameworks such as the Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation, provides a clear example of how strong regulatory alignment can accelerate infrastructure deployment, standardize interoperability, and support DSO innovation through flexibility platforms and digitalization.

Across regions, a convergent solution pathway becomes evident. Successful EV-grid integration depends on advanced smart charging and V2X capabilities that shift or modulate load in response to system needs; coordinated infrastructure planning, aligning charging deployment with feeder hosting-capacity constraints; clear, robust regulatory frameworks enabling flexibility markets, data exchange, and the use of storage; user-centric incentives and business models that address concerns about battery degradation, loss of control, and compensation adequacy; and digitalization and real-time system visibility, giving DSOs the tools required for active, data-driven system operation.

Electromobility is not a standalone technological transition but a systemic transformation that spans distribution system operations, regulation, market design, consumer behavior, and urban planning. International experience demonstrates that although there is no universal integration model, common lessons can guide DSOs in developing flexible, resilient, and future-proof distribution networks capable of fully exploiting the opportunities offered by electric mobility. The rapid expansion of EVs is reshaping electricity distribution systems around the world, introducing both significant opportunities for decarbonization and complex operational challenges. While EV integration can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and support renewable energy deployment, it also places considerable stress on existing grid infrastructures, particularly at low- and medium-voltage levels. Evidence from Europe, Australia, Canada, and Greece shows that successful integration requires a multifaceted approach combining technological innovation, regulatory adaptation, market-based incentives, and active stakeholder engagement. Advanced solutions such as smart charging, V2G services, and distributed storage integration can mitigate many technical issues; however, their large-scale deployment remains constrained by regulatory barriers and varying levels of social acceptance. Furthermore, the diversity of regional grid architectures and market designs underscores the need for tailored strategies rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

Despite the growing convergence around digitalization and market-based flexibility, it is important to acknowledge that the implementation of these solutions remains uneven across regions. DSOs operating in areas with limited infrastructure or incomplete regulatory frameworks face significant constraints that delay the transition from passive network management to active system operation. As illustrated in Canada’s remote communities with sparse charging access or in Greek island systems where reinforcement costs are disproportionately high, DSOs may lack both the digital visibility needed to manage EV loads in real time and the regulatory permission to deploy storage or participate in flexibility markets. Similarly, in liberalized markets such as Australia, tariff structures set by retailers can undermine DSO-driven smart charging policies, while fragmented standards limit interoperability between EVs, chargers, and grid platforms. These cases demonstrate that digitalization and flexibility must be complemented by region-specific regulatory reforms, investment in basic communication and monitoring infrastructure, and coordinated planning frameworks that enable DSOs to deploy or procure flexibility resources. Therefore, achieving equitable and scalable electromobility integration requires not only advanced market and digital solutions but also targeted policy and investment support to ensure that DSOs in weaker or underserved regions can fully participate in and benefit from the emerging flexibility ecosystem.

User engagement and interoperability are addressed in several regional initiatives, yet their international standardization remains essential to unlock cross-border mobility, scalable flexibility markets, and user-centric business models. A harmonized approach should combine binding technical standards with convergent business rules that enhance consumer trust and enable EVs to behave as universally accessible distributed energy resources. On the technical side, emerging standards such as ISO 15118 (vehicle–grid communication), Open Charge Point Protocol (OCPP), and plug-type harmonization already provide an international basis; however, their full implementation requires a common certification framework for chargers, aggregators, and EV manufacturers to ensure that smart charging and V2G functionalities respond consistently to grid signals. On the user-engagement side, international alignment on incentive structures—such as minimum compensation rules for flexibility participation, transparent tariff signals, and opt-in safeguards—can help overcome reluctance related to battery degradation and loss of control over charging. Experience from the EU, where AFIR mandates interoperability and open data access, and the Canadian and Australian contexts, where user incentives and standards remain fragmented, suggests that convergence must be driven by regulatory coordination between system operators, manufacturers, mobility service providers, and standardization bodies. Therefore, international cooperation on certification, standardized user incentives, and interoperable communication interfaces represents a prerequisite for scalable smart charging and user participation in global flexibility markets.

Policy Implications and Roadmap for DSOs

The integration of electromobility into distribution networks requires DSOs to evolve toward active system operation supported by flexibility resources, digital tools, and collaborative market structures. Within the ETIP-SNET large stakeholders group, a roadmap has been proposed during the previous years, with the latest version [53] addressing the following aspects (in the form of Priority Project Concepts):

- Technical and economic implications of decarbonization of the transport sector, including alternative strategies, funding mechanisms, and the impact on investments and system operation costs, as well as the system value of smart electromobility in providing control services.

- Enhancing the effectiveness of energy system operation and resilience with electromobility by assessing the benefits of smart control of charging infrastructures in providing system services through IoT connectivity.

- Integrated planning of energy and transport sectors, developing probabilistic system-planning approaches for large-scale deployment of transport electrification and storage technologies, harmonized standards and digital services enabling full interoperability, and electricity system design codes that incorporate secure smart charging and V2G practices for both slow and rapid charging infrastructures.

- Adapting policy and market frameworks for seamless, cost-effective integration of transport and energy sectors, including market designs that enable responsive charging infrastructure.

- Demonstration activities.

Based on the international evidence reviewed, key elements for a policy and regulatory roadmap include:

- Regulatory clarity and flexible markets: Achieving effective EV integration requires clear regulation defining the roles and responsibilities of DSOs, aggregators, and CPOs in smart charging and V2G service provision. DSOs must be enabled to procure flexibility services and, where appropriate, to own or operate storage assets as non-market resources to address local network constraints. A transparent set of rules governing user participation—such as minimum compensation mechanisms, stable remuneration structures, and consumer protection guidelines—helps ensure confidence in flexibility markets and encourages participation.

- Interoperable standards and open data frameworks: Interoperability is a prerequisite for scalable electromobility integration. Certification schemes for chargers, EVs, and aggregators based on international standards such as ISO 15118 and OCPP are essential to ensure that smart charging and bidirectional capabilities respond consistently to grid signals. Furthermore, real-time data exchange between DSOs and CPOs must rely on secure, machine-readable communication protocols and open-access principles similar to those mandated by AFIR in the EU. Such frameworks facilitate coordination, enhance operational visibility, and support advanced flexibility management.

- Targeted infrastructure investments and tailored deployment: Infrastructure investments should prioritize digital observability—through smart metering, feeder-level monitoring, and advanced grid analytics—before resorting to traditional reinforcement. This approach makes it possible to defer costly upgrades while improving operational efficiency. Dedicated investment programs are needed for regions with weak grids, remote communities, or isolated systems where microgrids, distributed storage, or flexibility-based solutions can offer more cost-effective alternatives to large-scale reinforcements.

- Consumer-centric incentives and engagement models: User participation in smart charging and V2G requires transparent and consistent incentive schemes. Harmonized tariffs and remuneration models can encourage controlled charging, V2G provision, and behind-the-meter flexibility services while safeguarding user autonomy and battery warranties. Equally important are measures that enhance consumer trust, including interoperable roaming, clear and comparable pricing, and universal accessibility of public charging networks. A consumer-centric approach increases the likelihood of widespread behavioral adoption and strengthens the overall flexibility ecosystem.

- Collaborative planning and cross-sector coordination: Effective integration of electromobility demands strong coordination between DSOs, municipalities, mobility operators, and charging service providers. Joint planning efforts should align charging infrastructure deployment with feeder hosting capacity and local network development plans. Transport electrification must be fully integrated into national energy strategies and urban mobility plans, particularly for public fleets, depots, and logistics hubs. Such cross-sector collaboration allows for optimized siting of charging infrastructure, avoids network bottlenecks, and enhances long-term system resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L.; methodology, I.L.; supervision, I.L.; formal analysis, I.L., P.M., N.d.S.e.S., and N.H.; investigation, I.L., P.M., N.d.S.e.S., and N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, I.L., P.M., N.d.S.e.S., and N.H.; writing—review and editing, I.L., P.M., N.d.S.e.S., and N.H.; visualization, I.L., P.M., N.d.S.e.S., and N.H.; funding acquisition, I.L. and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been financed by: the Research Fund for the Italian Electrical System under the Three-Year Research Plan 2025–2027 (MASE, Decree n.388 of 6 November 2024), in compliance with the Decree of 12 April 2024 and the resilient and Clean Energy Systems (RCES) Initiative under the Major Innovation Fund program of the Government of Alberta, Canada.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Nando Ochoa, from the Smart Grids and Power Systems Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering for providing us with the information that have been used to describe the contents of paragraph 7.

Conflicts of Interest

Ilaria Losa is employees of Ricerca sul Sistema Energetico and Nuno Sousa e Silva is employees of R&D Nester Redes Energéticas Nacionais. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Fesli, U.; Ozdemir, M.B. Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Integration, Adoption, and Optimization. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 140908–140931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barradas, A.; Musilek, P. A Geospatial Analysis of Public Charging Infrastructure and Electric Vehicle Accessibility in Indigenous Canada. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Humanitarian Technologies Conference (IHTC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 13–15 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fattler, T.; Zepter, J.; Weinhardt, C. Congestion management with electric vehicles: Potential cost savings in the German transmission grid. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 14, 328. [Google Scholar]

- Zema, T.; Sulich, A.; Grzesiak, S. Charging Stations and Electromobility Development: A Cross-Country Comparative Analysis. Energies 2023, 16, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulation; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu/transport-themes/clean-transport/alternative-fuels-sustainable-mobility-europe/alternative-fuels-infrastructure_en (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Schimeczek, A.; Ketelsen, P.; Klobasa, M. Impacts of §14a EnWG on grid operation and electric vehicle integration in Germany. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 16, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Zero-Emission Vehicles Policies and Regulations. 12 June 2025. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/transport/zero-emission-vehicles/zero-emission-vehicles-policies-and-regulations.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Trends in Electric Cars. 2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024/trends-in-electric-cars (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- International Energy Agency. Chinese NEV Development Plan 2035–English Translation; Internationale Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://changing-transport.org/wp-content/uploads/2021_NEV_Development_Plan_2035.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Alternative Fuels Observatory. Incentives and Legislation. 2024. Available online: https://alternative-fuels-observatory.ec.europa.eu/transport-mode/road/norway/incentives-legislations (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Australian Energy Market Operator. 2022 Integrated System Plan Inputs, Assumptions and Scenarios. 2022. Available online: https://aemo.com.au/en/energy-systems/major-publications/integrated-system-plan-isp/2022-integrated-system-plan-isp/current-inputs-assumptions-and-scenarios (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- European Distribution System Operators (EDSO). Smart Charging: Integrating a Large Widespread of Electric Cars in Electricity Distribution Grids. 2018. Available online: https://www.edsoforsmartgrids.eu/edso-publications/smart-charging-integrating-a-large-widespread-of-electric-cars-in-electricity-distribution-grids/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- National Energy System Operator (NESO). Demand Flexibility Service Delivers Electricity to Power 10 Million Households. Available online: https://www.neso.energy/news/demand-flexibility-service-delivers-electricity-power-10-million-households (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- National Energy System Operator (NESO). Powerloop: Trialling Vehicle-toGrid Technology. June 2023. Available online: https://www.neso.energy/document/281316/download (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ShareQ Project Consortium. ShareQ Project. Available online: https://shares-project.eu/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Australian Renewable Energy Agency. Australian Renewable Energy Agency: Projects. Available online: https://arena.gov.au/projects/ (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- German Federal Foreing Officer. The German Energiewende. Available online: https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/resource/blob/610620/5d9bfec0ab35695b9db548d10c94e57d/the-german-energiewende-data.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ELECTRIVE. Germany to Align Bidirectional Charging with Stationary Storage. 22 September 2025. Available online: https://www.electrive.com/2025/09/22/germany-to-align-bidirectional-charging-with-stationary-storage (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Agora Energiewende. How Is Germany Increasing Flexibility in the Power System; Agora Energiewende: Berlin, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://www.agora-energiewende.org/about-us/the-german-energiewende/how-is-germany-increasing-flexibility-in-the-power-system/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Guéret, A.; Carlos Gaete-Morales, C.; Wolf, P.S. A moderate share of V2G outperforms large-scale smart charging of electric vehicles and benefits other consumers. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2509.15284. [Google Scholar]

- Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE. Economic Potential of Bidirectional Charging. 30 October 2024. Available online: https://www.electrive.com/2024/10/30/fraunhofer-looks-into-economic-potential-of-bidirectional-charging/ (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- CSE for the California Energy Commission. California Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Project (CALeVIP). Available online: https://calevip.org/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- California Public Utlitites Commssion. Electricity Vehicles Rates and Cost of Fueling. Available online: https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/industries-and-topics/electrical-energy/infrastructure/transportation-electrification/electricity-rates-and-cost-of-fueling (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- California Energy Commission. Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Assessment–AB 2127. Available online: https://www.energy.ca.gov/data-reports/reports/electric-vehicle-charging-infrastructure-assessment-ab-2127 (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- ISO 15118-20:2022; Road Vehicles—Vehicle to Grid Communication Interface. ISO Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/77845.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- The State Council the People’s Republic of China. China Extends Preferential Purchase Tax Policy for NEVs. 21 June 2023. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/news/202306/21/content_WS64929394c6d0868f4e8dd11c.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- International Council on Clean Transportation. China’s New Energy Vehicle Mandate Policy. 2018. Available online: https://theicct.org/sites/default/files/publications/China-NEV-mandate_ICCT-policy-update_20032018_vF-updated.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- European Commission. Overview—Transport, Climate Action. 2024. Available online: https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/transport/overview_en (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- European Technology and Innovation Platform Smart Networks for Energy Transition (ETIP SNET). ETIP SNET WG1. Available online: https://smart-networks-energy-transition.ec.europa.eu/working-groups/wg1 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- European Commission. Industrial Action Plan for the European Automotive Sector; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2025; Available online: https://transport.ec.europa.eu/document/download/89b3143e-09b6-4ae6-a826-932b90ed0816_en (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- The Council of Canada. Regulations Amending the Passenger Automobile and Light Truck Greenhouse Gas Emission Regulations: SOR/2023-275. 15 December 2023. Available online: https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2023/2023-12-20/html/sor-dors275-eng.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Govenrment of Canada. Pause of the Incentives for Zero-Emission Vehicles Program. 10 January 2025. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/transport-canada/news/2025/01/pause-of-the-incentives-for-zero-emission-vehicles-program.html (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Rudri, B.; Giang, A.; Javed, B.; Kandlikar, M. Equitable charging infrastructure for electric vehicles: Access and experience. Prog. Energy 2024, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Electrokinisi. Charging Points Accessible to the Public Interconnected with the Register of Infrastructure and Electric Mobility Market Managers (M.Y.F.A.I.). Available online: https://electrokinisi.yme.gov.gr/public/ChargingPoints/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- European Commission: European Alternative Fuels Observatory. Greece: EV and PHEV Sales Soar by 36% in 2024. 2024. Available online: https://alternative-fuels-observatory.ec.europa.eu/general-information/news/greece-ev-and-phev-sales-soar-36-2024 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Hellenic Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport. Publicly Accessible Charging Points. 2025. Available online: https://electrokinisi.yme.gov.gr/public/ChargingPoints/?party=En (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Electrive. €17.5m for EV Charging in Greece and Cyprus. Available online: https://www.electrive.com/2025/09/09/e17-5m-for-ev-charging-in-greece-and-cyprus/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- ENERGYPRESS. SEAA: 60.9% of New Vehicles in the First Quarter Were Hybrid and Electric. Available online: https://energypress.gr/news/seaa-ybridika-kai-ilektrika-609-ton-neon-ohimaton-trimino (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- International Transport Forum. Advancing Sustainable Mobility in Greece—Electric Vehicles. 2023. Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/sites/default/files/advancing_sustainable_mobility-greece-ev_full_el.pdf (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- ABB. Terra High Power Charger—Up to 350 kW. 2024. Available online: https://new.abb.com/ev-charging/high-power-charging (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ionity. High Power Charging Network. 2024. Available online: https://www.ionity.eu/ (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Ectrokinisky. Register of Infrastructure and Electric Vehicle Market Entities. Available online: https://electrokinisi.yme.gov.gr/public/Account/Login?ReturnUrl=%2Fpublic%2F (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Karfopoulos, E.L.; Voumvoulakis, E.M.; Hatziargyriou, N. Steady-state and dynamic impact analysis of the large scale integration of plug-in EV to the operation of the autonomous power system of Crete Island. In Medpower; IET: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karfopoulos, E. Optimal Management of Electric Vehicles for Their Efficient Integration into Electricity Networks. Ph.D. Thesis, National Technical University of Athens, School of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Athens, Greece, 2017. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- DEI Greece. BluePass; DEI Greece: Athens, Greece; Available online: https://www.dei.gr/en/home/electricity/bluepass/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- NRG Greece. Incharge NRG. Available online: https://www.nrg.gr/el/nrgonthego (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Elpedison Greece. ELPEDISON DriveGreen Electricity 2. Available online: https://www.elpedison.gr/en/for-home/electricity/elpedison-drivegreen-electricity-2_133989/ (accessed on 4 July 2025).

- Karakitsios, I.; Lagos, D.; Dimeas, A.; Hatziargyriou, N. How Can EVs Support High RES Penetration in Islands. Energies 2023, 16, 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Energy Regulator. Annual Generation Capacity and Peak Demand–NEM. Available online: https://www.aer.gov.au/industry/registers/charts/annual-generation-capacity-and-peak-demand-nem (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Australian PV Institute. Australian PV Market Since April 2001. Available online: https://pv-map.apvi.org.au/analyses (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Australian Energy Council. Solar Report Q1 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.energycouncil.com.au/media/xlzd5qrl/solar-report-q1-2025.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Sunwiz. Battery Market Report–Australia 2025. Available online: https://www.sunwiz.com.au/battery-market-report-australia-2025/ (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- ETIP SNET. ETIP SNET, R & I Roadmap 2022–2031. 2022. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6092adfd-c2e8-11ed-a05c-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 27 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.