Abstract

In order to solve the problems of slow convergence speed, insufficient accuracy, and easily falling into the local optimum of the traditional whale optimization algorithm (WOA) in mobile robot path planning, an improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) combined with the bird navigation mechanism was proposed. Specific improvement measures include using logical chaos mapping to initialize the population to enhance the randomness and diversity of the initial solution, designing a nonlinear convergence factor to prevent the algorithm from prematurely entering the shrinking surround phase and extending the global search time, introducing an adaptive spiral shape constant to dynamically adjust the search range to balance exploration and development capabilities, optimizing the individual update strategy in combination with the bird navigation mechanism, and optimizing the algorithm through companion position information, thereby improving the stability and convergence speed of the algorithm. Path planning simulations were performed on 30 × 30 and 50 × 50 grid maps. The results show that compared with WOA, MSWOA, and GA, in the 30 × 30 map, the path length of IWOA is shortened by 3.23%, 7.16%, and 6.49%, respectively; in the 50 × 50 map, the path length is shortened by 4.88%, 4.53%, and 28.37%, respectively. This study shows that IWOA has significant advantages in the accuracy and efficiency of path planning, which verifies its feasibility and superiority.

1. Introduction

As one of the key technologies of mobile robots, path planning plays a vital role in the navigation of mobile robots [1,2]. In recent years, the research on path planning algorithms has formed a relatively mature system. According to the solution ideas and core mechanisms, it can be summarized into two categories: traditional path planning algorithms and intelligent path planning algorithms [3].

Among traditional path planning algorithms, Dijkstra’s algorithm [4], as a classic shortest path solving algorithm, realizes global path searching by traversing grid nodes. It has the advantages of strong stability and certain solution results. However, it lacks heuristic information guidance, has low search efficiency in high-dimensional complex environments, and cannot take into account path optimization needs. The A* algorithm [5] introduces a heuristic function to improve the search strategy, which greatly improves the path solution speed and has become one of the most widely used traditional algorithms in the grid modeling environment. However, it still has the problems of insufficient path smoothness and limited adaptability when facing dynamic obstacles. The artificial potential field method [6] achieves real-time obstacle avoidance by simulating the mechanical balance of attraction and repulsion. The principle is simple, and the response is rapid. However, it is prone to inherent defects such as unreachable targets and local minima, which limits its application in complex scenarios. Such traditional algorithms generally rely on the accuracy of environmental modeling and struggle to meet actual needs in unstructured environments or multi-constraint optimization scenarios, which has promoted the development of intelligent optimization algorithms in the field of path planning.

Intelligent path planning algorithms have become a research hotspot in this field due to their advantages of strong global search capabilities, wide adaptability, and their lack of a requirement to rely on accurate environmental models. Among them, the particle swarm optimization algorithm (PSO) [1] simulates the foraging behavior of a flock of birds and achieves optimal solution searching through individual collaboration. It has the characteristics of fast convergence and simple principles, but it is easy to fall into local optimality in the later stages of iteration. The genetic algorithm (GA) [7] is based on the theory of biological evolution and achieves population evolution through selection, crossover, and mutation operations. It is highly robust but has high computational complexity and limited adaptability to high-dimensional environments. The whale optimization algorithm (WOA) [8] is a new intelligent optimization algorithm proposed in 2016. Inspired by the group hunting behavior of humpback whales in nature, it has the unique advantages of simple structure, few optimization parameters, and strong global search capabilities. In recent years, its application in the field of path planning has gradually attracted attention.

However, the original WOA still exposes obvious shortcomings in path planning practice: slow convergence speed, easily falling into local optimal solutions, and insufficient optimization accuracy, especially in multi-obstacle, large-scale, or dynamic environments. These problems can lead to path redundancy, obstacle avoidance failure, or poor optimization performance [9,10]. In order to make up for the above shortcomings, domestic and foreign scholars have proposed a variety of improvement strategies: existing studies have improved the WOA through various strategies. Reference [11] proposed the whale optimization algorithm IMWOA based on the ideas of trapezoidal traction strategy and variable strategy, which enhanced the balance between global exploration and local development of the algorithm and greatly improved the convergence performance and accuracy. However, in some multimodal functions and high-dimensional non-convex function optimization problems, the algorithm is prone to insufficient convergence accuracy. Reference [12] uses an adaptive step size Gaussian walk strategy for global searching, weighing the global and local development capabilities of the whale optimization algorithm. Reference [13] integrates the golden sine algorithm to enhance the global search capability of the whale optimization algorithm. The convergence speed is accelerated, but it may lead to a decrease in the search ability of the algorithm when facing unknown data. Reference [14] proposed a whale optimization algorithm based on an improved predation and feedback mechanism, which improved the stability of the algorithm, but there is still room for further optimization in terms of the algorithm’s global search ability, convergence speed, and population diversity. Reference [15] prevents the algorithm from falling into a local optimal state in the late iteration by applying the reverse learning strategy of convex lens imaging.

In view of the core problems of the whale optimization algorithm in path planning, such as slow convergence speed, low optimization accuracy, and easily falling into local optima, this paper proposes an improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) path planning method that integrates the bird navigation mechanism. Logistic chaos mapping [16] is introduced to initialize the population to enhance the randomness and uniformity of the initial solution; nonlinear dynamic convergence factors are designed to adaptively adjust the weight of global exploration and local development according to the iterative process to improve convergence accuracy; adaptive spiral parameters are introduced to balance the search breadth and depth of the algorithm to avoid premature convergence; the bird navigation mechanism is integrated to further improve the algorithm’s operational stability and convergence speed through information interaction and direction guidance between individuals. Through simulation experiments, the IWOA was compared with the original whale optimization algorithm, the genetic algorithm, and the algorithm found in the literature [15] in environments with varying complexity, and the superiority of the proposed algorithm was verified from multiple dimensions such as path length and smoothness.

2. Whale Optimization Algorithm

The whale optimization algorithm (WOA) simulates the unique hunting behavior of humpback whales. It updates the position of individual whales through three methods—random search, encircling prey, and spiral predation—to obtain the optimal solution.

2.1. Random Search

When some individual whales are far away from the current optimal solution, they will move based on a random position as a reference. At this stage, solutions other than the current optimal solution can be found to avoid falling into the local optimal solution. The mathematical model of this process can be expressed as:

where denotes the distance between the position of the current individual whale and the position of a random individual whale; represents the position of the random individual whale; is the position of the current individual whale; denotes the current iteration number; and and are coefficient vectors. The calculation formulas of and are as follows:

where , is a random vector within the range [0, 1], and is a linear convergence factor that decreases from 2 to 0. The expression of a is as follows:

where denotes the maximum number of iterations.

2.2. Encircling Prey

When an individual whale’s position is closer to the current optimal solution, it will move to the position of the current optimal solution. At this time, the mathematical model can be expressed as:

where represents the position of the current optimal individual and denotes the distance between the current individual whale and the optimal individual.

2.3. Spiral Predation

When humpback whales are hunting, they release bubbles to form a spiral bubble network. This strategy is transformed into a process in which the search agent conducts a spiral search around the best solution [17]. The mathematical model at this stage is:

where is a constant for the spiral shape, usually set to 1; and is a random number within the range [−1, 1].

After individual whales approach their prey through both prey encircling and spiral predation, one of the two methods is chosen for predation based on probability. The specific formula is as follows:

where is the predation probability, and it is a random number within [0, 1].

For the random search and prey-encircling stages, the magnitude of vector determines which behavior mode to adopt. When , the algorithm focuses on global exploration and adopts the random search mode; when , the algorithm focuses on local exploitation and adopts the prey-encircling mode. Details are as follows:

3. Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm (IWOA)

In view of the WOA’s problems, such as insufficient initial population quality, linear decline in convergence factors leading to local optima, and fixed spiral parameters affecting search diversity, this paper makes improvements in four aspects: using logistic chaos mapping to initialize the population; designing nonlinear convergence factors; introducing adaptive spiral shape constants; and integrating bird navigation mechanisms to improve stability.

3.1. Logistic Chaotic Mapping

The initial positions of population individuals are initialized using logistic chaotic mapping, which helps the algorithm escape local optima, search for the global optimal solution more effectively, and improve the performance of the optimization algorithm. The mathematical model is as follows:

where is the control parameter. When = 4, the logistic chaotic mapping is in a fully chaotic state, exhibiting the strongest randomness and unpredictability. Therefore, = 4 is adopted in this paper.

3.2. Nonlinear Convergence Factor

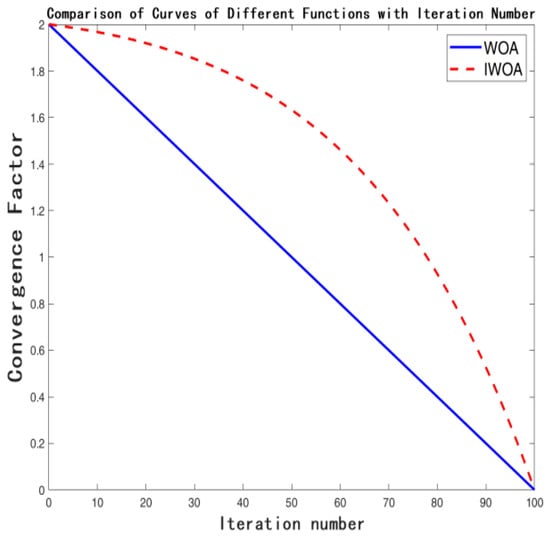

In the algorithm’s search process, the vector coefficient determines whether to search for solutions beyond the optimal one, preventing trapping in local optima. The magnitude of the convergence factor dictates the size of [18]. The larger is, the larger the coefficient is, and the smaller is, the smaller the coefficient is. When , the algorithm tends to conduct global exploration, guiding whale individuals away from the currently known optimal position to search a broader solution space. This helps discover new and potentially better regions, avoiding premature convergence to local optima. When , the algorithm enters exploitation mode [19], which is more biased towards local development, allowing individual whales to conduct a refined search around the currently found better solution, continuously optimizing existing solutions and mining solutions corresponding to better fitness values in the area, thereby improving convergence accuracy. Therefore, to ensure the algorithm can better escape local optima, the decrease of can be appropriately slowed to extend the global search duration. Based on this idea, introducing a nonlinear convergence factor is a feasible approach. The comparison of the convergence factors before and after improvement is shown in Figure 1. The mathematical formula for the improved convergence factor is as follows:

Figure 1.

Comparison of the curves of convergence factor before and after improvement.

3.3. Adaptive Spiral Shape Constant

In the WOA, the spiral shape parameter b is usually set to a constant so that individual whales lack diversity in posture when searching for prey [20]. The value of the spiral shape constant b determines the size of the spiral shape during the predation phase of the bubble net. The larger b is, the larger the spiral shape is and the wider the search range is; the smaller b is, the smaller the spiral shape is and the smaller the search range is. Therefore, this article chooses an adaptive spiral shape constant, specifically:

where is set to 2 and to 0.1. When b = 2, the spiral is relatively loose, facilitating global exploration. As the number of iterations increases, b decreases to 0.1, and the spiral gradually tightens, enhancing local exploitation capability. This aligns with the transition requirement from global exploration to local optimization.

3.4. Bird Navigation Mechanism

During the migration process of flying birds, the young birds will follow their parents [21], and this behavior can be integrated into the whale optimization algorithm. After the bird navigation method is introduced, individual whales can judge their own movement direction based on the positions of their surrounding companions, which can avoid blindly searching areas far away from the optimal solution and improve the quality and stability of the algorithm. Secondly, under the influence of peers, individual whales trapped in local optima have the opportunity to continue looking for other solutions and improve the accuracy of the algorithm. Finally, individual whales will gradually approach their companions who are already in a better area, improving the convergence speed of the algorithm. The specific method is as follows: let the position of a randomly selected whale be ; randomly select n individuals from all individuals as companions of this whale, with their positions denoted as . Calculate the average position of all companions :

The weight coefficient w is used to adjust the influence degree of the average position of companions on the whale individual and update the whale’s position. The specific approach is as follows:

where w is a constant within the range of [0, 1].

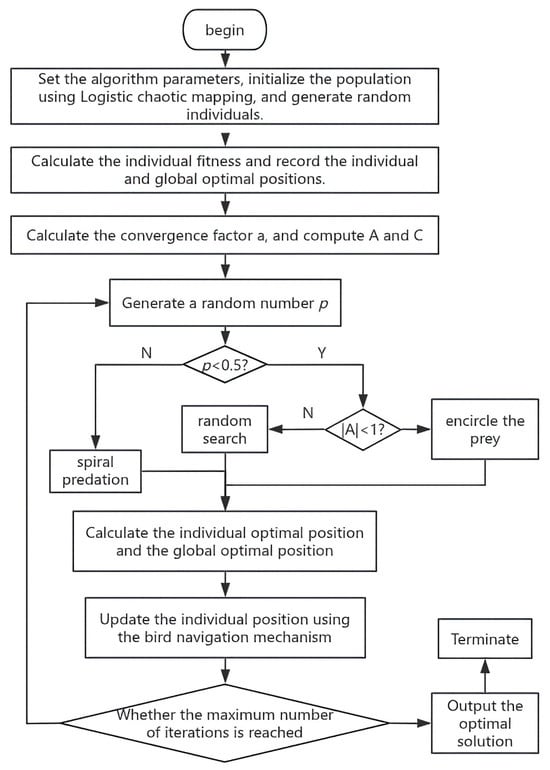

3.5. Flow of the Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm

The flowchart of the improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) is shown in Figure 2. The algorithm implementation steps are as follows:

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the improved whale optimization algorithm.

Step 1: set the algorithm parameters, use logistic chaos mapping to initialize the population, and generate random individuals.

Step 2: calculate individual fitness, and record the individual and global optimal positions.

Step 3: calculate the convergence factor, vector coefficients and , and generate random number .

Step 4: calculate the fitness of the individual whale at the current position through the formula, and compare it with the individual fitness of the whale at the previous moment. If the individual fitness at the current position is better than the original position, update the optimal individual position to the global optimal position.

Step 5: randomly select several individuals from all whale populations as partners of a single whale, and obtain the new individual position by calculating the average position of the surrounding partners and combining it with its own position.

Step 6: determine whether the algorithm reaches the maximum number of iterations. If the maximum number of iterations is not reached, return to Step 3; if the maximum number of iterations is reached, the optimal solution is output.

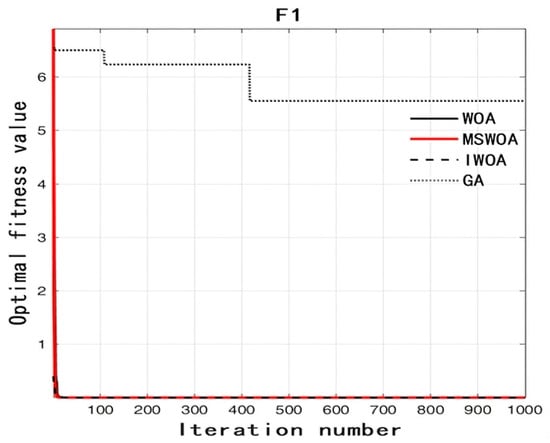

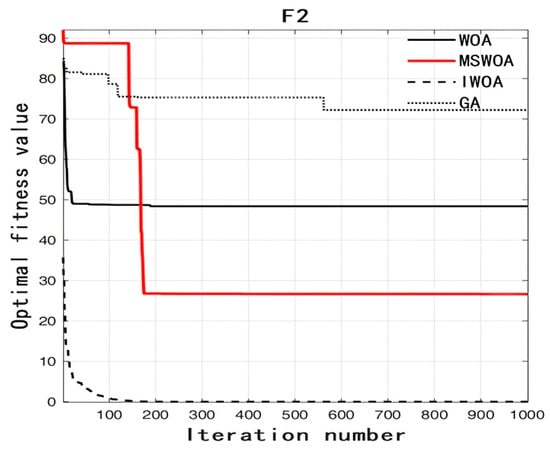

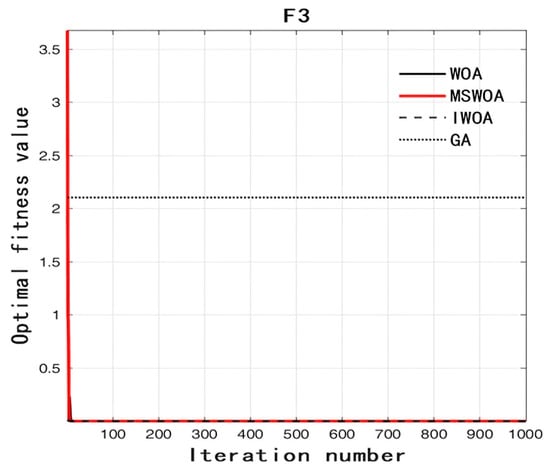

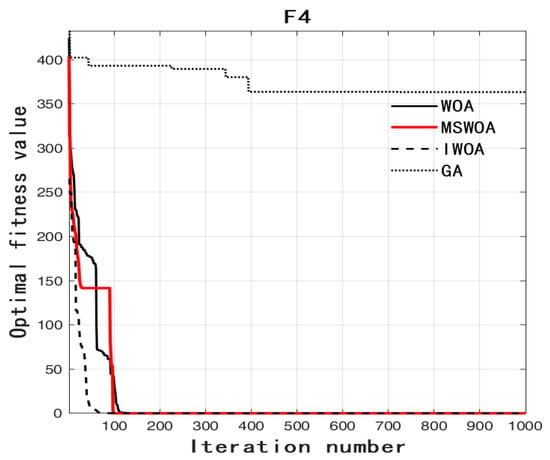

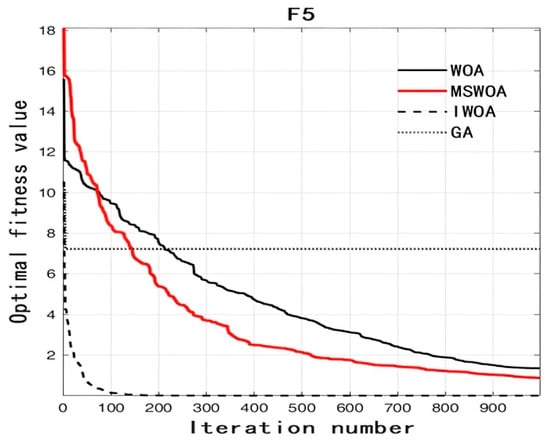

4. Performance Test of the Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm

Five test functions from the cec2005 test function set were selected, MATLAB R2024a was used to test the performance of IWOA, and comparative analysis was conducted with the traditional whale optimization algorithm (WOA), the algorithm in Ref. [15] (MSWOA), and the genetic algorithm (GA). The mathematical expression and optimal value of the test function are shown in Table 1. In this table, F1 is the sphere function, F2 is Schwefel’s problem 2.21, F3 is the Rosenbrock function, F4 is the Rastrigin function, and F5 is the Griewank function. In this test, the number of algorithm populations is 30, the dimension is 30, the number of tests is 10, and the maximum number of iterations is 1000. The test results are shown in Table 2, and the fitness and iteration number curve is shown in Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Table 1.

Mathematical expressions, function intervals, and optimal values of test functions.

Table 2.

Test results of CEC2005 under 30 dimensions and 1000 iterations.

Figure 3.

Fitness curve vs. iteration number of function F1.

Figure 4.

Fitness curve vs. iteration number of function F2.

Figure 5.

Fitness curve vs. iteration number of function F3.

Figure 6.

Fitness curve vs. iteration number of function F4.

Figure 7.

Fitness curve vs. iteration number of function F5.

As can be seen from Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, no matter which test function it is, the IWOA can basically find the optimal solution. In particular, when the test functions are F2, F4, and F5, the effect is more obvious. When the test functions are F2, F4, and F5, one can see that the IWOA can find the optimal solution at the early stage of iteration. From the average value shown in Table 2, one can also see that the IWOA can find the optimal solution in every test, and its performance is stable. This shows that the IWOA uses adaptive spiral parameters to expand the search range in the early iteration so that the optimal solution is found faster; secondly, the IWOA makes its performance more stable by integrating the bird navigation mechanism.

5. Application of the Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm in Path Planning

5.1. Establishment of the Objective Function

In the path planning process, each node can be regarded as an individual whale. The individual whale finally obtains a path through continuous updating and screening. In order to determine whether this path is the optimal path, an evaluation function needs to be defined [22].

In point-to-point obstacle avoidance path planning, path length is an important evaluation index [23]. In the path planning process, Euclidean distance is used to calculate the sum of distances between each two nodes, specifically:

where denotes the coordinates of the i-th node, and n is the total number of nodes in the path. To ensure the robot does not collide during path planning, a collision penalty term C needs to be defined [24]. When the current node does not collide with obstacles, C should be 0. When the node collides with obstacles, C should be set to a large value to eliminate this path and ensure safety, and it is set to 500 in this paper. The specific expression is:

To ensure the smoothness of the path [25], the entire path should have fewer inflection points. The calculation of the number of inflection points is as follows:

Let the node sequence of a path be

where represents the coordinates of the i-th node. Select every three consecutive nodes , , in the current path, and let the direction vectors of two adjacent node pairs be and . The included angleθ between the two direction vectors is calculated as follows:

Let an angle threshold be . When , the number of inflection points is increased by 1. Traverse the entire node sequence to obtain the final number of inflection points M. In this paper, is set to .

By integrating the above three indicators, an evaluation function is obtained as follows:

where is set to 0.8, is set to 0.1, and is set to 0.1.

5.2. Simulation of Path Planning Experiments

The experiments were conducted on a computer with the Windows 11 (64-bit) operating system, using MATLAB R2024a software. The computer is equipped with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-12450H processor and 16 GB of memory. The grid method [26] was adopted to model the robot’s working environment, with map sizes of 30 × 30 and 50 × 50.

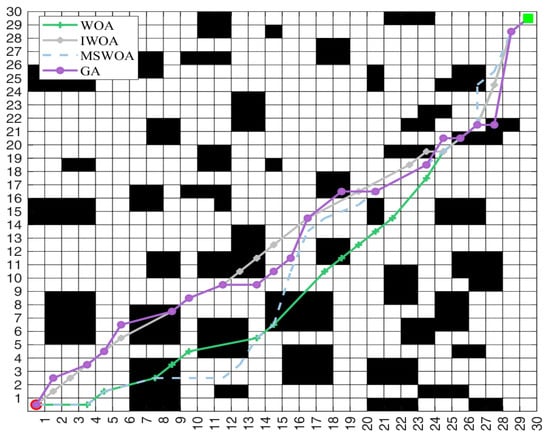

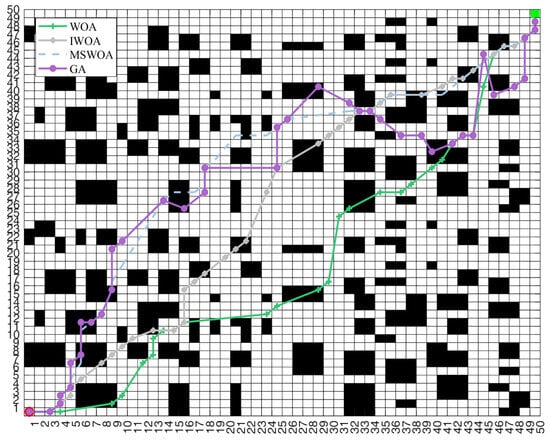

We set the starting point and ending point on the map; observed and compared the length of the journey to the ending point and the number of turning points of the traditional whale optimization algorithm (WOA), the reference [15] algorithm (MSWOA), the genetic algorithm (GA), and the improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) on different maps; and analyzed the feasibility of the improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) in path planning.

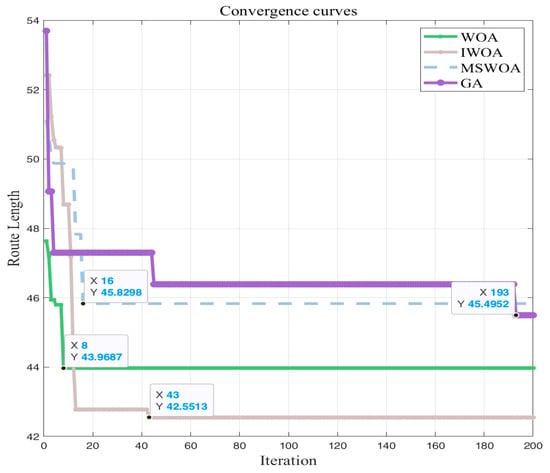

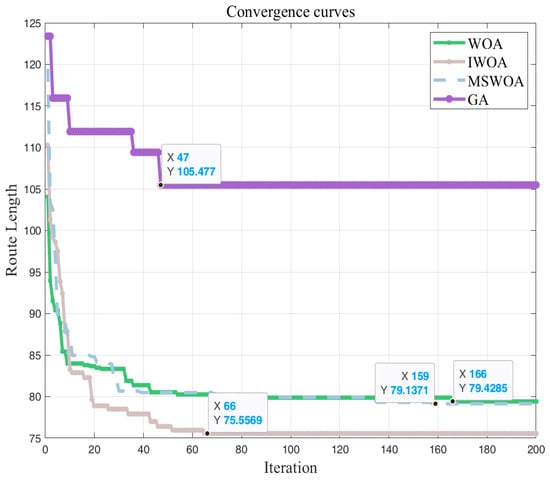

In this simulation, the algorithm population size is set to 200, the maximum number of iterations is 200, and the weighting coefficient w in the bird navigation mechanism is set to 0.3. Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 shows the convergence curves and path planning results of different algorithms on different maps, while Table 3 records the path length, number of iterations, number of inflection points, and evaluation function values of different algorithms on different maps.

Figure 8.

Comparison of iteration curves of four algorithms on 30 × 30 maps.

Figure 9.

Comparison of iteration curves of four algorithms on 50 × 50 maps.

Figure 10.

Path planning results of four algorithms on 30 × 30 maps.

Figure 11.

Path planning results of four algorithms on 50 × 50 maps.

Table 3.

Simulation results of point-to-point path planning.

It can be seen from Table 3 that in the 30 × 30 map, compared with the three algorithms of the WOA, MSWOA, and GA, the IWOA shortened the path length by 3.23%, 7.16%, and 6.49%, respectively. In a 50 × 50 map, compared with the WOA, MSWOA, and GA, the IWOA shortened the path length by 4.88%, 4.53%, and 28.37%, respectively, and had obvious advantages in the number of iterations and the number of inflection points. Therefore, the feasibility of the IWOA in path planning is proven. As can be seen from Figure 8 and Figure 9, although the IWOA has more iterations in the simulation, it has advantages in terms of path length and smoothness. This shows that although the nonlinear convergence factor used by the IWOA increases the random search time of the algorithm, it is able to find better optimal solutions and avoid falling into local optima, which proves the feasibility of the improved algorithm.

6. Conclusions

This paper studies the core problems of the traditional whale optimization algorithm (WOA) in mobile robot path planning. These problems include slow convergence, insufficient accuracy, and the tendency to fall into local optima. To this end, an improved whale optimization algorithm that integrates bird navigation mechanism is proposed to improve the efficiency and quality of path planning.

The main research methods focus on four aspects of improvement: using logistic chaos mapping to initialize the population to enhance the randomness and diversity of the initial solution; designing nonlinear convergence factors to prevent the algorithm from prematurely entering the shrinking surround stage and extending the global search time; introducing adaptive spiral shape constants to dynamically adjust the search range to balance exploration and development capabilities; integrating the bird navigation mechanism and optimizing individual update strategies through companion position information to improve algorithm stability and convergence speed. The performance was verified through five functions in the CEC2005 test function set, and path planning simulation experiments were carried out in two specifications of raster maps: 30 × 30 and 50 × 50. The improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) was compared with the traditional WOA, the algorithm found in the literature [15] (MSWOA), and the genetic algorithm (GA) in multiple dimensions.

The research results indicate that the improved whale optimization algorithm (IWOA) exhibits outstanding performance in the performance tests. In relation to comparative algorithms, it can find a better optimal function value and demonstrates faster convergence speed and stronger stability. In the path planning application, the path length generated by the IWOA is significantly shortened. Specifically, in a 30 × 30 grid map, the path length of the IWOA is reduced by 3.23%, 7.16%, and 6.49%, respectively, compared with that of the whale optimization algorithm (WOA), modified shuffled whale optimization algorithm (MSWOA), and genetic algorithm (GA). In a 50 × 50 grid map, the corresponding reductions are 4.88%, 4.53%, and 28.37%. At the same time, it has obvious advantages in controlling the number of inflection points, which verifies the significant superiority of the algorithm in path planning accuracy and efficiency.

Although the IWOA has achieved good results, there are still certain research gaps: first, the algorithm’s path planning adaptability in dynamic environments (such as obstacle movement, new obstacles) has not been verified, and the real-time response capability of complex dynamic scenes needs to be further explored; second, the current research does not consider the verification of mobile robots on real benchmark robot platforms or standard test sets and has not been applied to real robots; third, for larger-scale raster maps or multi-robot collaborative path planning scenarios, there is still room for improvement in the computational complexity and resource consumption optimization of the algorithm. Future research can conduct in-depth exploration in dynamic environment modeling, robot real-vehicle testing, large-scale scenarios, multi-robot collaborative adaptation, etc., to further expand the practical application scope and practical value of the algorithm.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.G. and T.Z.; methodology, T.Z.; software, T.Z.; validation, T.Z. and Z.G.; formal analysis, H.S.; investigation, S.J., Y.T. and Y.L.; resources, S.J., Y.T. and Y.L.; data curation, H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.G. and T.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.G. and T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 51675163.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

Author S.J., Y.T., and Y.L. were employed by the company Henan Kairui Vehicle Inspection and Certification Center Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Amr, M.; Bahgat, A.; Rashad, H.; Ibrahim, A.; Youssef, A. Optimizing Navigation in Mobile Robots: Modified Particle Swarm Optimization and Genetic Algorithms for Effective Path Planning. Algorithms 2025, 18, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zakaria, M.A.; Younas, M. Path Planning Trends for Autonomous Mobile Robot Navigation: A Review. Sensors 2025, 25, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.S.; Mohd-Mokhtar, R.; Arshad, M.R. A comprehensive review of coverage path planning in robotics using classical and heuristic algorithms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 119310–119342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Lin, C.J.; Lin, Y.J.; Lin, F.C. Application of Multi-Objective Optimization for Path Planning and Scheduling: The Edible Oil Transportation System Framework. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, B.; Jiang, H.; Liu, P. Path Planning for Construction Robot Based on the Improved A* Algorithm and Building Information Modeling. Buildings 2025, 15, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, J.; Wu, X.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J. Obstacle Avoidance Path Planning for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle in Workshops Based on Parameter-Optimized Artificial Potential Field A* Algorithm. Machines 2025, 13, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Bai, X.; Zhang, S.; Xu, C. The Path Planning of Mobile Robots Based on an Improved Genetic Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The whale optimization algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Kang, S.; Yu, J.; Wen, C. Path Planning of Robot Based on Improved Multi-Strategy Fusion Whale Algorithm. Electronics 2024, 13, 3443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Xu, H. An Improved Whale Migration Optimization Algorithm for Cooperative UAV 3D Path Planning. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Y. A Multi-Strategy Fusion Whale Optimization Algorithm and Its Application. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Jiang, S.Y.; Dong, Y.Q. Dynamic UAV Path Planning Based on Modified Whale Optimization Algorithm. Comput. Appl. 2025, 45, 928–936. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, G.C.; Ye, J.; Song, S.Y.; Sun, Q. An Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm for Robot Path Planning. J. Gun Launch Control 2025, 46, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.J. Research on Path Planning of Mobile Robot Based on Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm. Ph.D. Thesis, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, L. A multistrategy-improved whale optimization algorithm and its application. J. Harbin Eng. Univ. 2025, 46, 997–1004. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, G.C.; Baleanu, D. Discrete fractional logistic map and its chaos. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 75, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.Q.; Xu, J. Mobile Robot Path Planning Based on a Multi-Strategy Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm. Sens. Microsyst. 2025, 44, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.L.; Li, J.G.; Zhao, L.J.; Ji, J.; Ren, Y. Full-Coverage Operation Path Planning for Field Plots in Hilly and Mountainous Areas Based on Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2024, 40, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Fu, X.J.; Li, S.; Zhuang, Y. Path Planning of Wheeled Mobile Robots Based on Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm. Mach. Des. Res. 2024, 40, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Pan, J.B.; Wang, L.L.; Chen, H.C. Path Planning of Ground Pay-off Robot Based on Improved Whale Algorithm and A* Algorithm. Mod. Manuf. Eng. 2023, 12, 68–75+83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G. Bird Migration Navigation and Orientation. J. Tianshui Normal Coll. 1992, 2, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, T.B.; Yang, C.B. Dynamic Path Planning of Mobile Robots Based on Improved A*-DWA Algorithm. Chem. Autom. Instrum. 2025, 52, 893–901+955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.S. Research on Path Planning of Lawn Mower Robot in Open Environment. Master’s Thesis, Qilu University of Technology, Jinan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, W.; Yan, T.H. Path Planning Algorithm for Mobile Robot Based on Gradient Optimization. Mod. Electron. Tech. 2023, 46, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.F.; Wan, L.P. Research on Robot Path Planning Optimized by Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm. Mech. Sci. Technol. Aerosp. Eng. 2022, 41, 1759–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.Q.; Luo, K.W.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, T.Y. Path Planning of Improved A* Algorithm Based on Map Optimization. Comput. Simul. 2025, 42, 18–22+30. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).