1. Introduction

With the increasing severity of environmental issues, achieving peak carbon emissions and carbon neutrality has become a top priority for China [

1]. Driven by a series of related policies, China’s electric vehicle industry and supporting charging infrastructure have experienced rapid development [

2]. According to data from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, by the end of 2024, the number of electric vehicles in China was predicted to reach 24.72 million, accounting for 7.05% of the total number of vehicles, with a cumulative total of 9.596 million charging infrastructure units and an annual increase of 4.222 million units. This indicates that charging facilities have become an indispensable urban infrastructure. However, there are still many contradictions in the construction of charging infrastructure. In June 2023, the State Council issued the “Guiding Opinions of the General Office of the State Council on Further Constructing a High-Quality Charging Infrastructure System,” pointing out that there are still issues with the layout, structure, service, and operation of charging infrastructure, such as inadequate planning, irrational structure, unbalanced service, and insufficient regulation.

According to survey data from the China Charging Alliance (2023), the installation rate of charging facilities in residential areas built over 10 years ago is only 28.7%. In older residential areas with high population density, the vehicle-to-charger ratio is 5.3:1, resulting in insufficient charging facility supply and creating a situation of effective supply shortage. However, in commercial center areas, due to factors such as commercial support and policy guidance, the imbalance between the supply and demand of charging facilities not only results in land and resource wastage but also exacerbates range anxiety among electric vehicle users, severely hindering the promotion and widespread adoption of electric vehicles [

3]. In the process of constructing charging facilities in urban residential areas, on the one hand, due to delays in design and planning and the rapid growth in the number of vehicles, the number of reserved parking spaces in some residential areas often fails to meet the rapidly growing parking demand [

4]. On the other hand, the construction of charging facilities creates conflicts of interest between government agencies and property management companies, with uneven distribution of benefits, which restricts the construction and development of charging infrastructure [

5].

In the early stages of urban charging facility construction, the lack of proper planning and layout, along with temporary [

6] and disorderly construction [

7], has led to a significant imbalance between the supply and demand of charging facilities, resulting in both overcapacity and shortages. There are significant differences in the accessibility [

8] and utilization rates [

9] of charging facilities. This often leads to long queues at some charging points, while others experience underutilization [

10]. The supply–demand imbalance is also evident in the fact that, even within the same city, EV users may struggle to find charging facilities in some areas, while in others, charging stations remain unused [

11]. Based on real charging data from Berlin, an analysis of the utilization rates of charging facilities revealed that in areas with higher population density, such as the city center, charging demand is significantly higher. However, their study only examined the supply and demand of charging facilities in the city center and at the urban fringe, without further exploring the differing charging demands in various types of areas such as shopping centers, tourist attractions, and so on [

3]. The rational layout of charging facilities is key to solving the supply–demand imbalance and requires a more systematic approach to planning and building electric vehicle infrastructure.

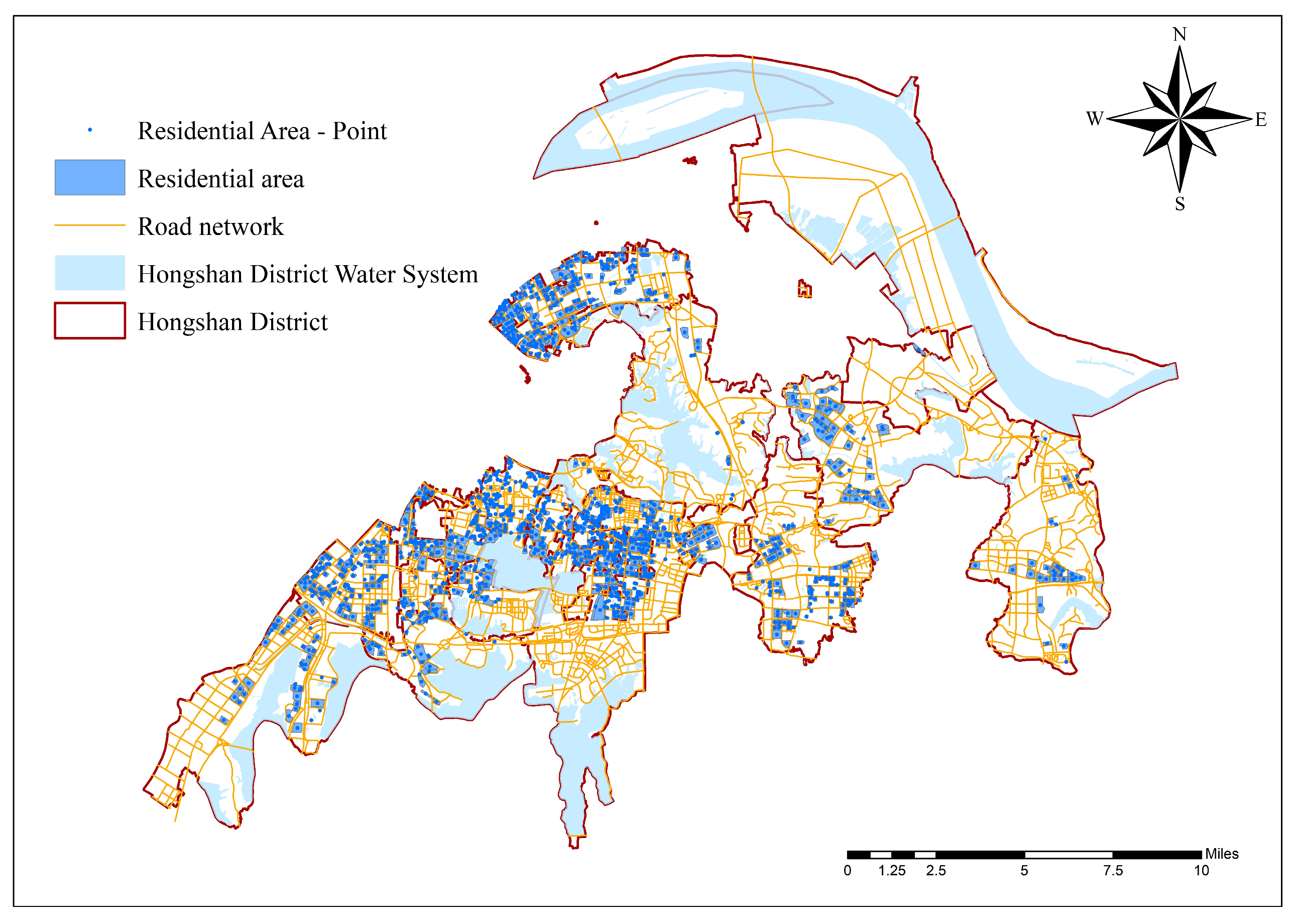

In recent years, Wuhan has actively responded to the national strategy for the development of new energy vehicles, vigorously promoting the popularization and application of electric vehicles, and actively advancing the construction and development of charging infrastructure. The Wuhan Development and Reform Commission has emphasized the need to accelerate the construction of charging infrastructure in residential areas, highlighting that the improvement and optimization of residential area charging facilities is one of the key areas of focus in the current electric vehicle infrastructure development. Hongshan District is one of the central urban districts of Wuhan and an important economic, educational, and cultural area of the city (

Figure 1). According to relevant policies, from 2024 to 2025, the district plans to build and upgrade a total of 7890 charging piles, 82 public charging stations, and 8 battery swapping stations. By the end of 2024, it was said that there would be a total of 1464 residential areas under the jurisdiction of Hongshan District, with 287 effective charging facilities. This study provides relevant recommendations and strategies for the construction and improvement of charging facilities in residential areas of Hongshan District, based on the perspective of collaborative service supply and the balance of residential charging demand.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

(1) The objective of this study is to balance the supply–demand relationship of residential-area charging facilities, which differs from previous research that primarily focused on site selection and capacity determination. To address this issue, we develop a “residential area–charging facility” collaborative service network model based on complex network methods. Unlike traditional approaches that emphasize topological connections between facilities, the proposed model highlights actual service relationships and demand allocation to quantify the collaborative service capacity among facilities, thereby providing a new network-based perspective for supply–demand analysis.

(2) By combining the utilization of existing charging facilities with their collaborative service capabilities, the study employs cluster analysis to summarize the supply–demand balance status of residential area charging facilities. It identifies three different supply–demand structure types and proposes targeted construction strategies, offering valuable reference for the guidance of charging facility development and enriching the research methodology for charging infrastructure construction.

(3) This paper collects actual charging data from Hongshan District, Wuhan, which differs from electric vehicle user data and simulation data, thus providing a more accurate reflection of the real usage of charging facilities.

2. Literature Review

Existing research on the planning and siting of electric vehicle charging infrastructure, demand analysis, and facility utilization has produced a substantial body of knowledge, which provides an essential foundation for this study.

In terms of planning layout and site selection, existing discussions primarily focus on three aspects: the factors influencing the siting of charging stations [

12,

13] cost optimization [

14] and advancements in model algorithms [

15,

16]. Multi-objective planning methods are one of the key approaches for addressing charging-station planning problems that aim to minimize costs or maximize benefits [

17]. Such research provides effective tools for charging-station siting and capacity determination in specific application scenarios [

18,

19,

20]. In addition, simulation methods are also among the most commonly used approaches in charging infrastructure planning [

21,

22]. However, most of these methods focus primarily on the planning stage, while comparatively limited attention has been paid to systematically evaluating how an existing facility network matches its actual service capacity with real and complex demand dynamics.

In terms of charging-demand analysis, existing studies primarily follow two paradigms: traffic-flow-based demand forecasting and user-travel-behavior-based demand prediction [

23]. Scholars have conducted in-depth investigations from multiple perspectives, including the spatiotemporal distribution of charging demand, charging preferences, and demand forecasting [

24,

25,

26]. There is a consensus that charging demand is significantly influenced by multiple factors, including population density, parking availability, and traffic conditions, and exhibits pronounced spatial heterogeneity [

27,

28,

29].Accurate estimation of electric vehicle charging demand requires the support of multi-source, heterogeneous data. Based on this, this study collects various data on factors influencing charging demand and conducts in-depth demand analysis.

In terms of facility utilization analysis, utilization rate is a key metric representing both demand intensity and operational efficiency of the facilities [

9,

30]. High-demand areas are typically associated with higher facility utilization rates [

11,

31]. Analyzing the factors influencing charging facility utilization can support decision-making regarding facility layout and improve operational efficiency [

32]. Therefore, analyzing utilization is crucial for identifying priority areas for development and optimizing operational decision-making [

33,

34,

35]. This study aims to analyze the differences between charging demand and the utilization of existing charging facilities to identify priority cities and areas for charging facility construction and guide the scientific development of charging infrastructure.

In recent years, complex network theory has been introduced into this field, offering a new perspective for studying charging infrastructure from a systemic viewpoint [

36]. Wang Wentao et al. constructed an electric vehicle charging infrastructure network model based on complex network theory, and applied this model to analyze the charging infrastructure networks of four cities: Shanghai, Xi’an, Hefei, and Dalian [

37]. Liu Qiwei investigated the utilization efficiency of new energy vehicle charging facilities based on complex network theory [

38]. Li et al. employed an evolutionary game approach within a complex network framework to examine the impact of government policies on the diffusion of electric vehicles (EVs) [

39]. Fang et al. established an evolutionary game model based on complex networks to analyze the dynamic impacts of government subsidies and tax policies on the proportion of charging station construction [

40]. R.Chen et al. constructed an evolutionary game model based on networks to investigate the effects of various electric vehicle charging infrastructure (EVCI) incentive policies on promoting EVCI deployment in China [

41]. D. Zhao et al. proposed a three-stage evolutionary game model to explore how to promote the diffusion of new energy vehicles in the context of complex networks [

42]. Huang et al. introduced an agent-based evolutionary game model in a complex network environment to understand and predict the diffusion dynamics of electric vehicle (EV) charging stations [

43]. Network-based evolutionary game models provide an effective means of gaining insights into the promotion of public charging stations. However, the aforementioned studies primarily focus on the application and analysis of complex networks in network topology, with limited discussion on the supply and demand relationship between nodes and functional areas.

In summary, existing research on charging infrastructure often focuses on independent site selection or macro-level demand forecasting, neglecting the collaborative service capabilities of the charging infrastructure network as a complex system and its spatial matching relationship with the charging demand in specific functional areas. Therefore, based on relevant theories and methods of complex network analysis, this study takes Wuhan’s Hongshan District as a case study, constructing a “residential area–charging facility” collaborative service network. The study explores the differentiated supply and demand structural characteristics between charging facilities and residential areas, and proposes construction strategies for different supply–demand types.

3. Methodology

This study proposes a comprehensive analysis framework of the “Residential Area Charging Demand Spatial Unit-Collaborative Service Network” by integrating geographic spatial analysis with complex network theory (

Figure 2). First, the spatial representation of demand and supply is achieved by quantifying residential charging demand and analyzing the utilization rate of charging facilities. Next, a collaborative service network is constructed, and its topological indicators are calculated to systematically evaluate the collaborative supply capability of the facilities from the overall, local, and node levels. Finally, based on this, a dataset is constructed by integrating demand, utilization rate, and network structure characteristics, and K-means clustering is used to identify differentiated supply and demand structure types, providing scientific basis for proposing precise and differentiated optimization strategies.

3.1. Residential Charging Demand Analysis

To quantify the spatial differences in residential charging demand, this section first defines charging demand spatial units based on user spatial behavior theory, and then constructs a residential charging demand index by integrating multiple data sources.

(1) Residential Charging Demand Spatial Unit Division

This study introduces the Charging Facility Searching Radius (CFSR) and the Charging Demand Unit (CDU) to quantitatively analyze the spatial matching relationship between charging facility layout and user demand.

CFSR refers to the maximum travel cost users are willing to incur when actively searching for a charging facility under constraints of range anxiety and traffic accessibility. In this study, the cost is defined by the maximum acceptable travel time rather than Euclidean distance. The calculated value is CFSR = 4500 m. The quantitative model is as follows:

In the equation:

T

max = 15 min (the maximum acceptable time threshold for users to search for a charging facility, data sourced from a questionnaire survey with a sample size of

);

km/min (the effective driving speed of electric vehicles under low battery conditions, empirically validated using onboard GPS data [

44]); G represents the actual road network within the study area. The effective speed Veff(G) is not a fixed value; rather, it is a dynamic parameter determined jointly by the topology, hierarchy, and traffic conditions of the road network.

CDU is defined as the continuous coverage area of the CFSR delineated through road network analysis, with the urban residential area as the spatial origin (

Figure 3). It represents the fundamental matching unit between the service capacity of charging facilities and users’ spatial demand (

Figure 4).

(2) Calculation of Residential Charging Demand

Static data such as residential travel survey data, census data, and vehicle registration data are commonly used in charging demand studies [

45]. Factors related to parking lot density, road density, transportation hub density, and built environment characteristics reflect the convenience of transportation [

46,

47]. The number of electric vehicles (EVs) in a given area refers to the total number of EVs in that region. Areas with a higher number of EVs tend to have higher charging demand [

48]. Therefore, the number of electric vehicles is an important indicator of the charging market size. Based on a review of the literature, questionnaire surveys, and field research, this study identifies six residential charging demand influencing factors: residential population density, parking lot density, road density, density of consumer-related POIs (points of interest), transportation hub density, and the number of electric vehicles. The variables are explained in

Table 1. The value ranges of each indicator within the residential charging demand units are shown in

Figure 5.

The weights of the indicators are determined using the Coefficient of Variation (CV) method. The CV method is an objective weighting approach based on the degree of data dispersion, which measures the variability of indicators through the ratio of standard deviation to mean. A larger coefficient of variation indicates stronger spatial heterogeneity of the indicator and higher explanatory power for demand differentiation [

49], making it suitable for weight distribution in multi-source heterogeneous data [

50]. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the equation:

ωj: Final weight of the -th indicator;: Standard deviation of the -th indicator across all spatial units;: Mean value of the -th indicator across all spatial units;: Total number of indicators (6 in this study);: Coefficient of variation (CV) of the -th indicator.

To ensure the reliability of weight assignment, this study conducted a multicollinearity test alongside the calculation of the coefficient of variation (CV). Multicollinearity may distort the independent contribution of each indicator, thereby affecting the validity of CV-based weighting. Diagnostics were performed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Generally, a VIF value below 5 indicates that multicollinearity is within an acceptable range.

The descriptive statistics of each indicator, the calculated CV values, and the VIF test results are shown in

Table 2. The results indicate that the density of transportation hubs (CV = 4.479) exhibits a significantly higher coefficient of variation than the other indicators, implying the greatest spatial heterogeneity among residential areas in Hongshan District. This suggests that it has the strongest explanatory power for the spatial differentiation of charging demand and therefore receives the highest final weight (0.356). This is followed by consumption-related POI density (CV = 2.684) and parking-lot density (CV = 2.300). Meanwhile, all indicators have VIF values below the threshold of 5. Although transportation hub density (VIF = 3.632) and parking-lot density (VIF = 3.885) show mild multicollinearity, they remain within the acceptable range, indicating that the CV-based weighting scheme is robust and reliable.

The Charging Demand Index (CDI) is an indicator that reflects the intensity of residential charging demand by weighting multiple influencing factors. The weighted sum model is a linear multi-criteria decision-making method, where the standardized indicator values are multiplied by their corresponding weights and then summed to obtain the comprehensive demand index. The calculation formula is as follows:

In the equation:: Comprehensive charging demand index for the -th residential area;: Weight of the -th influencing factor; : Standardized value of the -th indicator for the -th residential area; : Total number of influencing factors (in this study, ).

The Residential CDI for Hongshan District, as calculated, is shown in

Figure 6.

3.2. Charging Facility Actual Utilization Rate Analysis

The total transaction power of a charging station refers to the amount of electricity provided by the charging piles to electric vehicles within a specific time period, and it can effectively reflect the utilization of charging facilities [

51]. In this study, the average transaction power of the charging piles at each charging station is used to reflect the utilization rate of the charging facilities. The research time window is set from 14 February to 22 February 2025, and the monitoring scope covers 287 public charging stations in Hongshan District, Wuhan, with a total of 5520 charging piles. A 60 min sampling interval was used, and the real-time status of each charging pile was recorded, including the following four states: in use, idle, faulty, and available, along with data such as total transaction power. The calculation formula is as follows.

In the equation:

represents the sum of the total transaction power at all time points during the study period;

represents the average total transaction power per time point during the study period;

represents dividing by the number of charging piles to obtain the average transaction power per charging pile.

The spatial distribution of charging facility utilization rates in Hongshan District shows a significant spatial heterogeneity pattern (

Figure 7). Most facilities have low utilization rates, especially in the peripheral areas of the city (below 0.083). These areas have scattered charging demand and low traffic flow, leading to low facility utilization. In contrast, in the core areas of the city, such as the Wuhan Railway Station hub area and the Wuchang Inner Ring core area, utilization rates are higher (above 0.418), indicating concentrated charging demand in these areas and the presence of a synergistic effect between the facilities.

3.3. Collaborative Service Network Modeling and Structural Analysis Metrics

To evaluate the collaborative service capacity of charging facilities from a system perspective, this study constructs a collaborative service network through the following three steps (

Figure 8). The service relationships between residential areas and charging facilities are shown in

Figure 8a. This model analyzes the complex service relationships between facilities based on three dimensions: the existence of service relationships, the breadth of collaborative coverage, and the intensity of collaborative load.

3.3.1. Construction of the Residential Area–Charging Facility Bipartite Network

First, the service relationship between residential area Q and charging facility S is established. A bipartite network matrix

of size |Q| × |S| constructed, where edges represent charging facilities located within the charging demand unit (CDU) of a residential area, and the edge weight is the charging demand index (CDI) of that residential area. If facility

serves residential area Q

k then the matrix element B

i,k = CDI

k; otherwise, it is 0 (

Figure 8b).

3.3.2. Construction of the Charging Facility Counting Collaborative Network

The counting collaborative network aims to quantify the degree of connectivity between facilities based on the shared service of residential areas. A matrix C of size is |S| × |S| constructed. The off-diagonal elements C

i,j (where i ≠ j) represent the number of residential areas jointly served by facilities S

i and S

j; the diagonal elements C

i,i represent the number of residential areas independently served by facility S

i (

Figure 8c). This network reveals the breadth of collaborative services between facilities.

3.3.3. Construction of the Weighted Demand Collaborative Service Network

The weighted demand collaboration is a weighted matrix W of size ∣S∣ × ∣S∣ (

Figure 8d), which simultaneously considers the independent service capability of nodes and the intensity of collaborative services between nodes. The weight calculation is based on a demand allocation model that takes into account facility capacity and distance.

First, the attraction weight α

ik of facility S

i to residential area Q

k is calculated, which is determined by its capacity C

i (the number of charging piles) and the Euclidean distance

dik to the residential area. The formula is:

Subsequently, the total demand CDIk of residential area Qk is allocated to all facilities within its demand zone according to the weight proportion:

where Φk is the set of facilities serving residential area Qk.

Finally, the elements of the matrix W are calculated:

The node weight represents the self-service capability of facility Si:

The edge weight represents the collaborative service intensity between facilities Si and Sj, which is the average of the demand load borne by both facilities in the residential area Qk that they jointly serve:

The actual service relationships between residential areas and charging facilities in the study area are shown in

Figure 9. The collaborative service network of charging facilities, constructed based on actual data, is shown in

Figure 10.

To analyze the structural characteristics of the collaborative service network of charging facilities from multiple dimensions, this study selects key indicators at the overall, local, and individual levels (

Table 3).

Based on the definitions of the above indicators, the calculation methods are as follows:

Network Density:

where P is the network density, L is the number of actual links in the network, and n is the number of actual nodes in the network.

Clustering Coefficient:

where C

i represents the local clustering coefficient of node i, E

i is the number of edges between the k

i neighbors of node i, and C

2 represents the overall clustering coefficient of the network. n is the total number of nodes in the network.

Degree Centrality:

where C

RD(ni) is the relative degree centrality of node i, d

r(ni) is the in-degree of the node (the number of other nodes connecting to this node, i.e., the number of relations directed towards the node), d

c(ni) is the out-degree of the node (the number of relations originating from the node), and N is the size of the network.

Betweenness Centrality:

where C

ABi is the absolute betweenness centrality, b

jk(i) is the probability of node i appearing on the shortest path between nodes j and k, and n is the total number of nodes.

4. Results

This chapter presents and interprets the topological structure analysis results of the Residential Area–Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network in Hongshan District. Through the calculation of network density, k-core, clustering coefficient, and centrality indicators, the overall connectivity, core–periphery structure, local clustering characteristics, and the functionality of key nodes in the network are revealed.

4.1. Overall Network Structure

The analysis results show that the density of the collaborative service network is 0.0980. This indicates that, among the 287 charging facility nodes, the actual number of collaborative service connections established is less than one-tenth of the total possible connections, reflecting a relatively sparse overall connectivity in the collaborative service network. The majority of facilities lack effective collaborative service relationships. Among the 287 facilities, only 231 (80.49%) have established service relationships with residential areas, while 56 facilities have no service connections with any residential area and are in an isolated state. This structure suggests that the current charging facility network is a collection of many independent nodes rather than an organically coordinated system.

4.2. Local Structural Characteristics Analysis

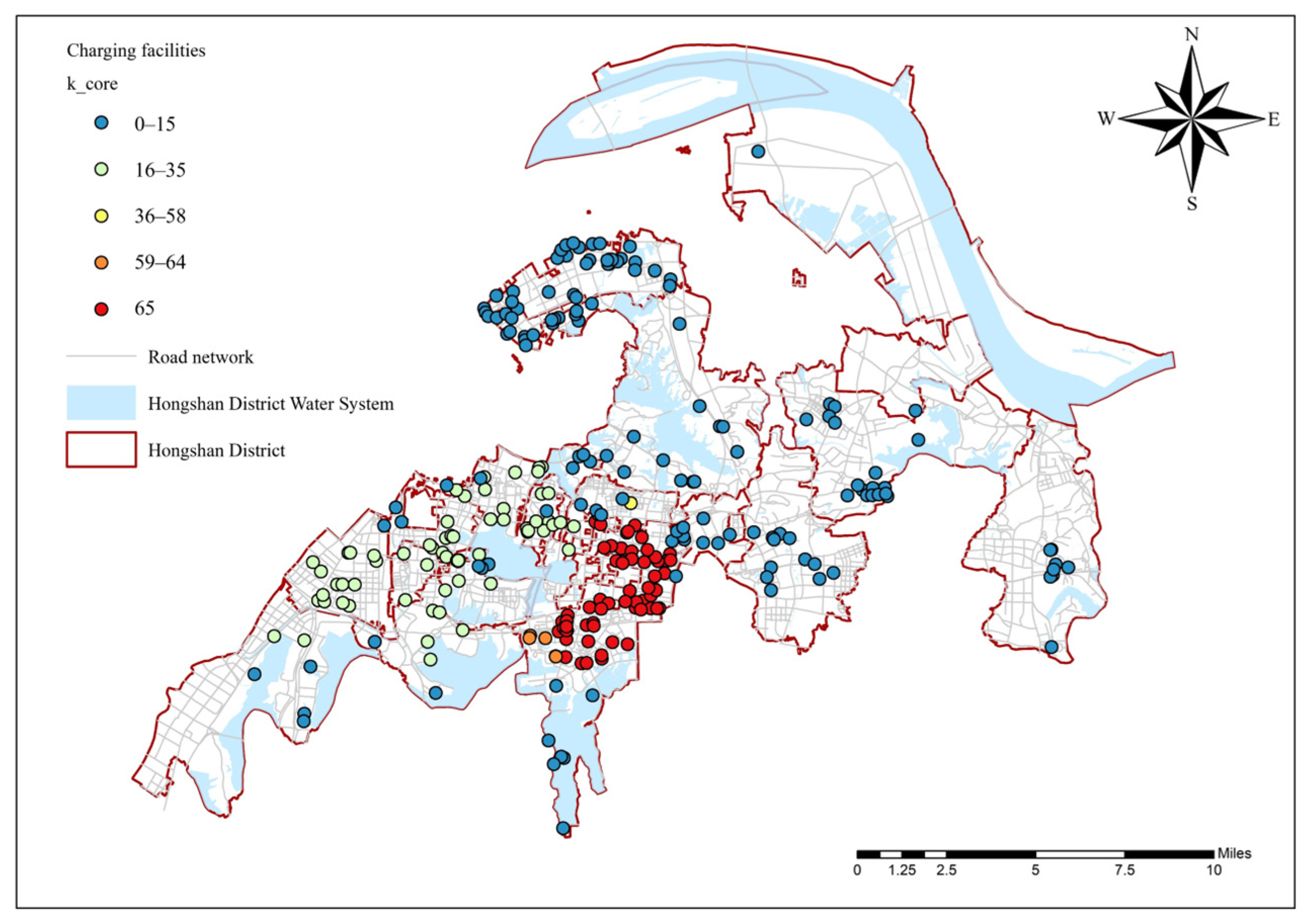

The k-core decomposition results (

Table 4) clearly reveal the hierarchical structure of the network. A k = 65 maximum subcluster consisting of 66 facilities (23.0%) forms the core hub group of the network. These facilities bear the highest density of collaborative service tasks in the network, constituting the backbone of the network. Meanwhile, the number of peripheral facilities with k = 0 is as high as 147 (51.2%). These facilities are in a completely or nearly isolated state within the network and have not integrated into the collaborative service network. This distribution indicates that the service load of the network is highly concentrated on a few core facilities, while more than half of the facilities are located at the periphery of the network topology. This “highly concentrated core, widely distributed periphery” structure means that the collaborative service load of the network is mainly concentrated on the approximately 23% of core facilities, while over half of the facilities fail to contribute to collaborative service effectiveness.

From the spatial distribution perspective (

Figure 11), the core-layer facilities (k-core ≥ 58) are highly concentrated in the continuous core belt in the eastern and central parts of Hongshan District, which is the area with the highest density of residential areas. This indicates that the core topology of the charging network is fundamentally driven by the spatial distribution of high-demand residential areas. In contrast, the peripheral facilities with k-core = 0 are widely dispersed in the western and southern periphery of the urban built-up area. These areas typically correspond to low-density residential areas or areas with low electric vehicle adoption rates. Therefore, the “core–periphery” structure of the network is essentially a systematic mapping of the spatial differentiation pattern of “high-demand residential clusters–low-demand residential areas” onto the collaborative service network.

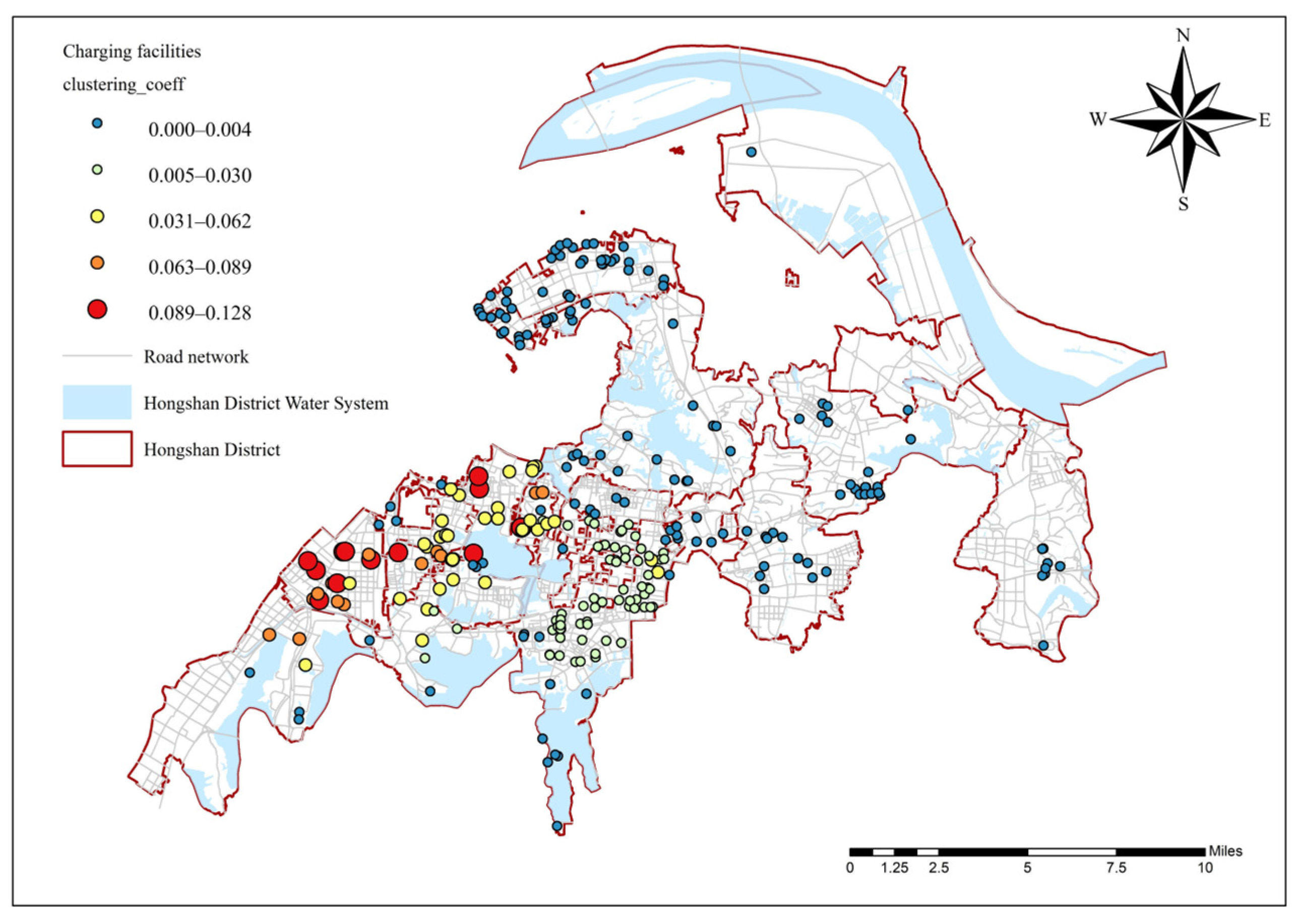

The global average clustering coefficient of this network is 0.0183, and 80.5% of the facilities have a clustering coefficient below 0.2. The number of facilities with a high clustering coefficient (>0.5) is zero, while facilities with a low clustering coefficient (<0.2) account for as much as 80.5% (231 facilities). This result indicates that the network lacks tight triangular connections at the local scale, i.e., the “cluster effect” is weak. Taking key facilities S136 and S195 as examples, although they play critical “bridge” roles in the global network, their clustering coefficients are only 0.0017 and 0.0021, respectively. The direct connections between facilities in their neighborhoods are very sparse, forming star-shaped structures centered around them rather than more redundant mesh-like structures. This suggests that when the network faces local disturbances, its service load cannot form effective collaborative services between adjacent facilities, reducing the network’s local robustness and service redundancy.

The spatial distribution of clustering coefficients is shown in

Figure 12. The clustering coefficient of the vast majority of facilities falls within the lowest range (0.000–0.004), and their spatial distribution is dispersed. This indicates that, even in areas with dense high-demand residential areas, the layout of charging facilities shows a “point dispersal” rather than a “clustered collaboration” characteristic. The fundamental reason for this is that the facilities generally respond to the demand of individual residential areas in a point-based manner, rather than planning for entire residential areas as a whole. As a result, multiple facilities serving the same densely populated high-demand residential area lack opportunities to form a local “triangle” mutual support network, severely limiting the local resilience of the network.

4.3. Individual Feature Analysis

4.3.1. Connectivity Degree: Degree Centrality

The top 10 facilities ranked by degree centrality all have values higher than 0.24 (

Table 5), significantly surpassing the network’s average level. These facilities are directly connected to over 24% of the other facilities in the network. Among them, facilities S4 and S195 serve as the most widely connected service hubs. These high-degree-centrality facilities form the backbone of the collaborative service network and are typically located at transportation hubs or demand-intensive areas. Through their extensive direct connections, they effectively enhance the service redundancy and reliability in localized regions.

The spatial distribution of degree centrality (

Figure 13) shows that high-degree-centrality facilities form several localized service clusters, with their locations precisely corresponding to several large and mature high-demand residential areas within Hongshan District, such as the areas along the South Lake and the Luoyu Road corridor. Each local hub collaborates with many other facilities to cover the same or adjacent high-demand residential clusters. Therefore, these clusters represent the spatial aggregation and overlap of residential charging demand, forming the most robust modular foundation of the service network.

4.3.2. Connectivity Dependence: Betweenness Centrality

The analysis results indicate that this metric exhibits a highly uneven distribution within the study area (

Table 4). Facility S136 has the highest betweenness centrality value (0.1407), which suggests that it appears far more frequently in the shortest path for users seeking charging services compared to other nodes, making it structurally critical for the overall connectivity efficiency of the network.

Facilities S195 (0.1208) and S37 (0.1187) also exhibit relatively high betweenness centrality, and together with S136, they form the key dependency points within the collaborative service network. These facilities are typically located on transportation corridors connecting different geographic or functional areas, playing an indispensable structural hub role in the network’s topology. This distribution pattern means that the operational status of these key facilities will have a decisive impact on the overall accessibility and robustness of regional charging services.

The spatial distribution of betweenness centrality (

Figure 14) accurately identifies the few “strategic bridges” in the network. These facilities (e.g., S136, S195) are usually located on key passages that connect different residential clusters. Their core value lies in transferring and facilitating charging service flows between residential clusters, such as linking the “South Lake large residential area” and the “outer residential areas of the Wuchang core.” This implies that the charging facility network must not only meet static demand within residential areas but also ensure the continuity of charging services for dynamic travel between residential zones. These key nodes are strategically crucial for maintaining overall network connectivity.

4.3.3. Node Role Analysis

Based on the centrality metrics and facility utilization data, this study identifies the different functional roles that nodes play within the collaborative service network.

On one hand, the nodes in the network exhibit functional differentiation. For example, facilities S4 and S195, as high-connectivity hubs, provide a broad direct service range, whereas facilities S136 and S37, as high-dependency bridges, are crucial for maintaining overall network connectivity.

On the other hand, the data analysis reveals different combinations of centrality roles and utilization efficiency. Taking facility S136 as an example, it has the highest network connectivity dependence, but its actual utilization level is relatively low. In contrast, facility S195 has high connectivity, high dependency, and high utilization efficiency.

These different functional roles and utilization efficiency combinations provide key insights for the multi-dimensional supply–demand structure clustering of residential areas, which will be discussed in

Section 5.

5. Discussion

This chapter aims, based on the network structure analysis results presented in Chapter 4, to conduct a clustering analysis integrating multidimensional features, with the following research objectives: (1) to identify differentiated supply–demand structure types of residential charging facilities within the study area, with a particular focus on detailed analysis of the dominant “transitional mixed type”; (2) to explore the formation mechanisms and core issues of different types (and subclasses) in depth; and (3) based on the above diagnosis, to propose a hierarchical optimization framework and differentiated strategies—“overall network optimization–local cluster coordination–individual facility enhancement”—thereby translating structural research findings into actionable planning and management insights.

5.1. Supply–Demand Structure Type Identification Framework

The study establishes a comprehensive quantitative feature system as the basis for clustering analysis. This system integrates three main dimensions: demand side, supply side, and network structural attributes, to analyze the multifaceted characteristics of residential charging services.

(1) Construction of Clustering Feature System

Charging Demand Index (CDI): This index represents the potential charging demand intensity of a residential area. The higher the value, the stronger the potential demand for charging services in that area.

Aggregated Utilization Rate (ŪR): This indicator measures the overall operational efficiency of all charging facilities serving a particular residential area. It is calculated through a weighted aggregation based on the weights obtained from the demand distribution model in

Section 3.3.1. The calculation formula is as follows:

where:

Φk is the set of facilities serving residential area k; Si ← k is the demand weight allocated to facility i from residential area k; URi is the utilization rate of facility i.

Aggregated Degree Centrality (Ďegree): This indicator represents the overall influence and connection breadth of all charging facilities serving a residential area in the collaborative service network. It is similarly aggregated by the demand distribution weights, and the calculation formula is as follows:

Using the above methods, this study aggregates the facilities and data to the residential area (CDZ) level, constructing a dataset that includes 1445 residential area samples, with each sample containing three feature values: (CDI, ŪR, Ďegree).

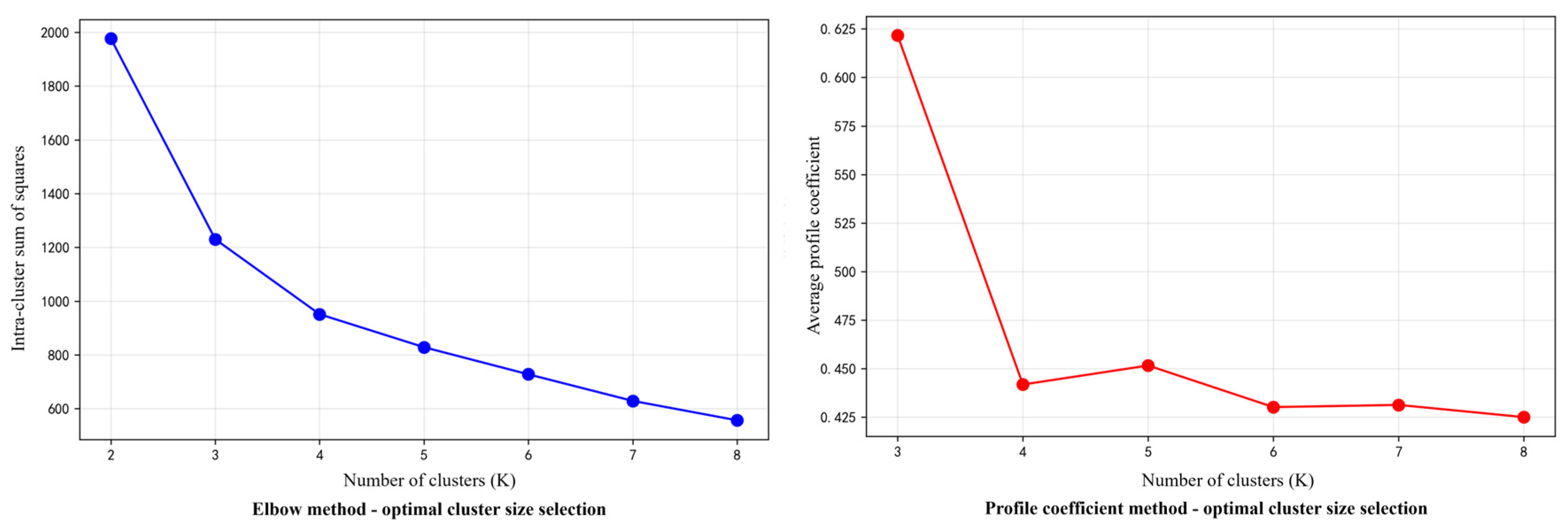

(2) Clustering Process and Parameter Determination

The Z-score method is used to eliminate the dimensional influence of the feature data. To avoid subjective pre-setting of the number of clusters, this study uses a combination of the elbow method and silhouette coefficient for cross-validation. As shown in

Figure 15, when k = 3, the elbow method curve exhibits a clear inflection point in the rate of decline. After calculating the average silhouette coefficient for various k values (k = 2 to 8), it was found that when k = 3, the silhouette coefficient reached its maximum value of 0.625, indicating that this is the optimal number of clusters.

(3) K-means Clustering Execution

Based on the optimal number of clusters (k = 3) determined above, the study applies the K-means algorithm to perform clustering analysis on the feature data. To ensure the optimization of the initial centroids and reproducibility of the results, a random seed of 42 is set.

5.2. Clustering Results Analysis

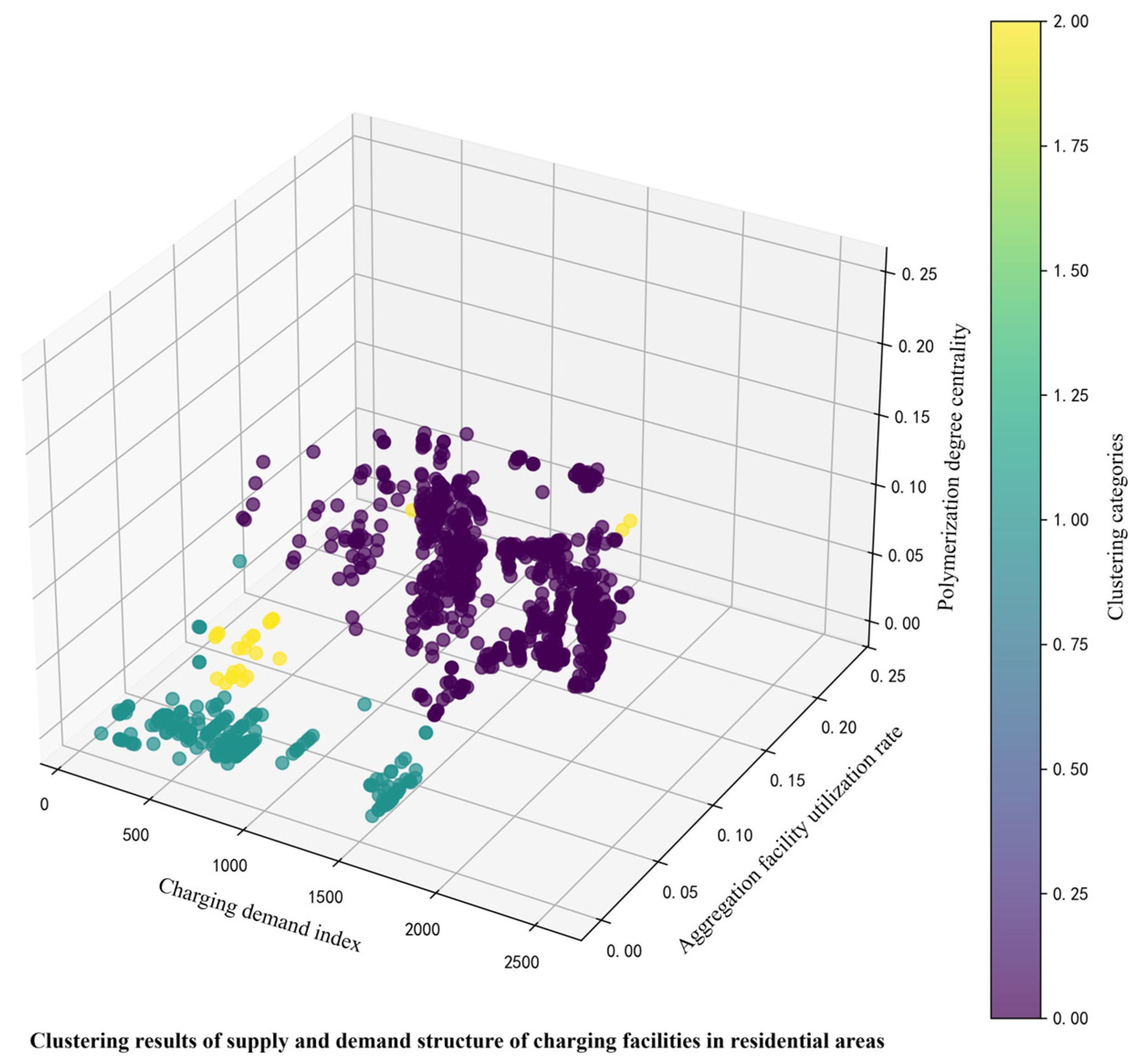

Based on the previous K-means clustering analysis, the 1445 district CDUs in Hongshan District are divided into three clusters with distinct characteristics. These clusters are clearly separated in the three-dimensional feature space. This section will systematically present and thoroughly interpret the clustering results.

5.2.1. Supply–Demand Structure Type Feature Analysis

As shown in the clustering result in

Figure 16, the three types of supply–demand structures identified in this study exhibit clear separation and gradient variation in the three-dimensional feature space of “Charging Demand Index–Aggregated Facility Utilization Rate–Aggregated Degree Centrality” (

Table 6).

Efficient Collaborative Type (Type I) districts occupy the ‘high–high–high’ quadrant, forming a compact cluster. Transitional Mixed Type (Type II) districts, being the majority in number, do not exhibit a specific value but rather are characterized by significant internal heterogeneity. The sample points of this type are the most dispersed and widespread in the three-dimensional space, suggesting that these districts are not a homogeneous group but rather a collection of various supply–demand imbalance scenarios. Low-Demand Marginal Type (Type III) districts cluster around the ‘low–low–low’ origin, indicating that these districts are not only lagging in a single dimension but are simultaneously in a systemic predicament of low levels in all three core dimensions of charging demand, facility utilization, and network collaboration capacity.

This clear separation validates the effectiveness of the clustering algorithm and visually reveals that the supply–demand status of residential charging facilities in Hongshan District exhibits non-homogeneous, hierarchical structural types.

5.2.2. Multidimensional Feature Correlation and Hierarchical Structure

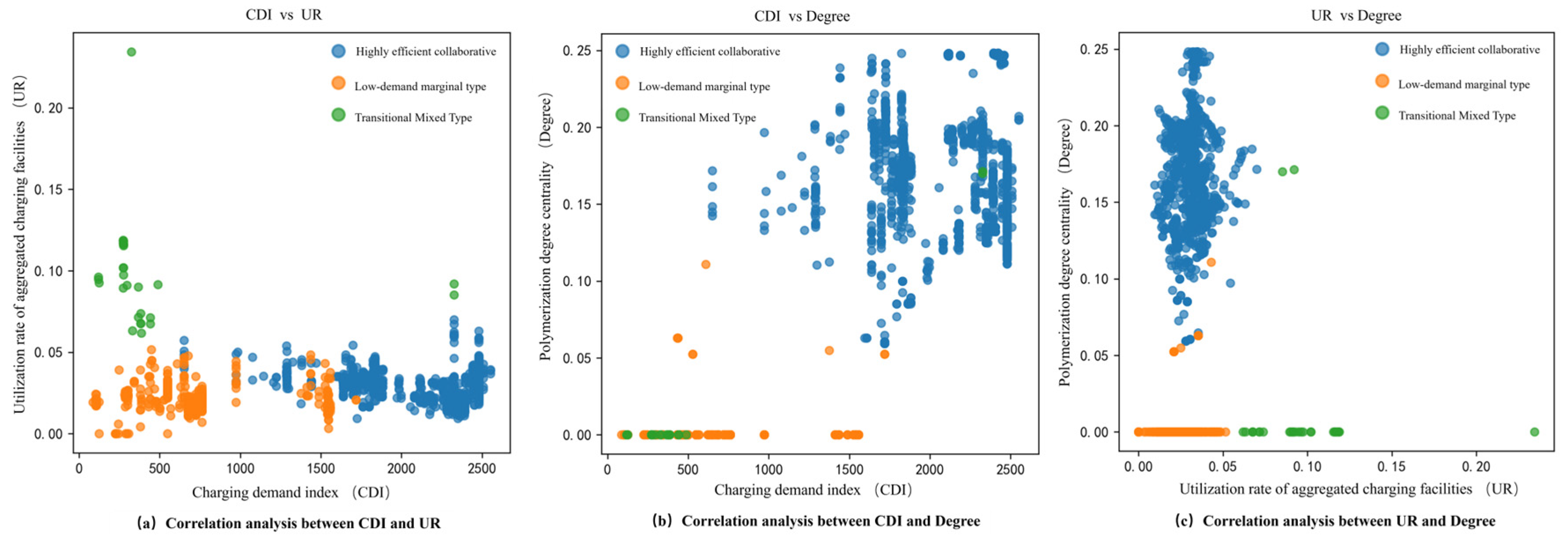

Based on the identification of the three typical residential types, this section further analyzes the intrinsic correlations between their multidimensional features and examines the systematic hierarchical structure they form. By exploring the relationships between the charging demand index, facility utilization, and network centrality, the deep mechanisms driving the differentiation of supply–demand structures are revealed.

The Fundamental Driving Role of the Demand Side. In

Figure 17a, two key phenomena can be observed. First, the charging demand index (CDI) is the dominant dimension distinguishing different types. The high-efficiency collaborative type and the low-demand marginal type are almost completely separated along the horizontal axis (CDI), indicating that the intrinsic demand intensity of a residential area is the foundation determining whether it can enter a positive development trajectory. Second, overall, CDI shows a significant positive correlation with facility utilization, confirming the basic logic that demand creates supply, and supply guides usage. However, it is worth noting that in the transitional mixed type of residential areas, particularly in the CDI range of 500 to 1500, there is a large fluctuation in utilization rates, from below 0.05 to close to 0.20. This indicates that for these types of residential areas, besides the demand level, the operational status of the facilities themselves, accessibility, service quality, or other unobserved factors such as electricity prices, play a crucial role in moderating the final usage efficiency.

Spatial Coupling of Network Structure and Demand.

Figure 17b reveals the matching relationship between supply-side planning and demand-side distribution. High-efficiency collaborative residential areas not only have high demand but also rely on charging facilities that occupy central positions within the network, achieving a high coupling between high-demand residential areas and high-network-centrality facilities. In contrast, some transitional mixed residential areas exhibit characteristics of high demand and low centrality. These areas are typical examples of planning lag, where their strong charging demand has not been integrated into an efficient collaborative service network, leading to potential service gaps and a decline in user experience. This is a priority area to address in future network optimization efforts.

The Synergistic Enhancement Effect of Network Centrality and Facility Utilization Rate. As shown in

Figure 17c, the three clusters are arranged along the diagonal, presenting a strong positive correlation and linear trend. This empirically demonstrates the synergistic enhancement effect between network advantages and operational efficiency. A facility located at the center of the collaborative network is prioritized by users due to its high accessibility and service redundancy, which increases its utilization rate. Conversely, a high utilization rate further consolidates and strengthens the facility’s hub position within the network. This finding provides key support for the core argument of this paper: treating charging facilities as an interconnected network, rather than isolated points, and optimizing the network structure to improve overall operational efficiency is a scientifically sound and necessary shift in planning paradigms.

In the analysis of

Figure 17 it was observed that in all three scatter plots, a certain number of sample points had feature values approaching zero. These “zero-value” samples are not data anomalies but accurately depict the extreme supply–demand imbalance faced by the “Low Demand Marginal” residential areas. Specifically, a CDI approaching zero means that the residential area has an extremely low potential charging demand intensity, derived from its population, vehicle ownership, and supporting infrastructure, under the current evaluation system. A ŪR approaching zero indicates that the charging facilities serving these residential areas are essentially completely idle, revealing a severe case of “ineffective supply.” Meanwhile, a Ďegree approaching zero further confirms from a network topology perspective that these facilities are isolated “service islands” without collaborative service relationships with other nodes in the network, making them highly vulnerable. The appearance of these zero values not only corroborates the clustering results from

Section 5.2.1 but also, from the perspective of continuous variables, highlights the systemic planning blind spots in the city’s edge or low-density areas.

5.2.3. Second-Level Clustering Analysis of the Transitional–Mixed Type

We applied a probabilistic approach using the Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to perform a second-order clustering analysis on the dominant “transitional-mixed” residential areas. The results indicate that this type can be further subdivided into three subclasses (

Table 7).

5.3. Differentiated Construction Strategies Based on Supply–Demand Structure Types

Based on the clustering analysis results mentioned above, this study proposes differentiated optimization strategies for the three types of residential areas, focusing on their core characteristics and main issues.

5.3.1. Efficient Collaborative Type: Key Hub Expansion and Resilience Enhancement

This network structure is mature but experiences concentrated load, so the strategy focuses on ensuring the operation of key nodes and optimizing the network structure to disperse risks.

(1) For facilities with high degree centrality and utilization rates consistently above 85% (e.g., S4, S195), implement flexible expansion. This can be achieved by adding more charging spaces, upgrading to high-power chargers, or installing backup power generation systems to directly increase service capacity.

(2) For facilities with high betweenness centrality but relatively low utilization (e.g., S136), optimize service accessibility. Measures such as improving traffic signage to the facility, offering exclusive discounts on electricity rates, and guiding traffic flow can help activate its underutilized strategic connections and redistribute traffic for the entire network.

(3) In areas served by a single high-centrality facility, plan and construct backup charging stations or strengthen physical connections with nearby facility clusters. This will create alternative service pathways and reduce over-reliance on a single point.

5.3.2. Transitional Hybrid Type: Network Structure and Efficiency Optimization

This type is key to improving the overall network effectiveness. The strategy focuses on concurrently optimizing the network structure and improving the operational efficiency of existing facilities.

(1) Filling Service Gaps and Enhancing Connections: For high-demand, low-supply areas with a high CDI but low Ďegree, prioritize the planning and construction of new public charging stations. Site selection should focus on key corridors connecting existing facility clusters, or leverage large public parking spaces to fill gaps in network coverage and enhance the service connections between facilities. This will physically strengthen the collaborative potential of the network.

(2) Demand Guidance and Reliability Management: For high-demand but inefficient areas (high CDI, low ŪR), implement time-of-use electricity pricing and use navigation apps to direct users to the charging stations during off-peak hours. This helps balance the load and increases the utilization efficiency of idle capacity. Additionally, establish an operation and maintenance response system to ensure that faulty charging stations are promptly repaired, improving the reliability of the facilities.

(3) Differentiated Service Mode Configuration: In commuting areas, increase the number of DC fast chargers. In older residential communities, collaborate with property management to focus on deploying AC slow chargers and explore models such as “community unified construction and operation,” allowing the supply model to better match specific demand characteristics.

5.3.3. Low-Demand Peripheral Type: Demand Induction and Network Integration

The core challenge in this type of district is the vicious cycle caused by low demand and the marginalization of network facilities. The strategy focuses on activating potential demand and organically integrating peripheral facilities into the collaborative service network.

(1) Demand Activation through Incentives: Given the low electric vehicle ownership in this type of district, implement phased charging service discounts and reward points at facilities within the area to stimulate market demand.

(2) Positioning Peripheral Facilities as “Refueling Nodes”: For peripheral facilities located along the connecting corridors between core and edge areas, clearly designate them as “refueling nodes” for regional commuting. Prioritize these facilities in the route planning of navigation apps, and label them as “long-distance range support stations” to transform them from service islands into functional nodes within the network, catering to cross-regional traffic flows.

(3) Building Local “Micro-Networks”: In areas with multiple peripheral facilities, create self-sustaining “micro-networks” that enhance the overall service reliability and collaboration of facilities in the region. This strategy breaks the dependence on the main network and improves the resilience of the local service structure.

5.4. Implementation Framework and Steps of the “Evaluation–Diagnosis–Optimization” Approach

To systematically advance the optimization strategy, this study proposes a three-stage implementation framework—Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Optimization (

Table 8).

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the persistent supply–demand imbalance of electric vehicle (EV) charging facilities within urban residential areas. By developing a collaborative “residential area–charging facility” service network and incorporating comprehensive spatial clustering analyses, the research provides a novel analytical framework and planning implications for mitigating spatial mismatches in charging infrastructure supply and demand. The main conclusions drawn from this research are as follows:

Firstly, in terms of the overall network structure, the collaborative service network of charging facilities in the study area presents a “sparse overall, core concentration” topology. The network density is only 0.098, and more than half of the facilities are located at the network’s periphery (k-core = 0), indicating a lack of effective collaboration and a low degree of systematization among the facilities. However, a tight core layer consisting of approximately 23% of the facilities (k-core = 65) bears most of the collaborative service load in the network. This provides a structural basis for the transition from a “point-based layout” to a “networked operation” planning model.

Secondly, in terms of spatial matching between supply and demand, residential units can be divided into three distinct types of supply–demand structures. Among them, the “highly efficient collaborative” residential areas (23.6%) successfully achieve a spatial coupling of high charging demand with highly networked central facilities. The “transitional mixed” residential areas (65.5%) exhibit significant internal heterogeneity, making them the most dynamic and flexible component of the system. “Low-demand peripheral” residential areas (10.9%) are trapped in a systemic dilemma of “low demand–low utilization rate–low network integration.” This classification accurately diagnoses the spatial differentiation patterns of current supply–demand imbalances.

Finally, at the system-level mechanisms, this study finds that the charging demand index is a foundational dimension driving supply–demand differentiation, and there is a significant synergistic enhancement effect between facility utilization rates and network centrality. This suggests that improving the collaborative ability of facilities within the network is not only a technical means to optimize spatial layout but also a key mechanism to drive the system toward a virtuous cycle and improve the overall efficiency of supply-side resources.

This study also has several limitations. The charging facility utilization data used for analysis covers only a specific period. Although this data window provides a solid basis for assessing supply–demand conditions, it may not fully capture the medium- to long-term dynamics of charging demand and usage patterns. Therefore, conclusions drawn from this data—particularly regarding absolute utilization levels and determinations of “high/low efficiency”—need to be validated in future studies using longer-time-series data. The constructed collaborative service network is primarily based on residential charging demand and does not fully account for the complexity of a single charging facility serving multiple functional areas, such as residential, commercial, and office zones. For newly developed areas, emphasis should be placed on forward-looking planning synchronized with the “collaborative service network” blueprint; for older residential areas, lightweight and retrofit solutions, such as “shared charging” and “community-wide coordinated construction,” should be explored. Analyzing these cross-functional service relationships is an important topic for future research. Moreover, the growth of electric vehicle (EV) ownership has a decisive impact on charging demand. This study mainly relies on current data and does not incorporate forecasts of future EV ownership. Therefore, future research should strengthen forward-looking predictions of EV scale under different urban policy scenarios, incorporating key policy measures such as fiscal subsidies. Future studies could integrate long-term operational data, EV ownership projections, and urban development scenarios.

By combining charging demand, facility utilization, and network collaboration, this study proposes a “assessment–diagnosis–optimization” framework for differentiated analysis. This framework not only provides a new tool for identifying the spatial logic of supply–demand imbalance but also, by revealing the system mechanism of “collaborative enhancement,” offers a reference pathway for promoting scientific planning and coordinated development of urban charging infrastructure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. (Yunfang Zha), Y.H. and Y.Z. (You Zou); Methodology, Y.Z. (Yunfang Zha) and Y.Z. (You Zou); Software, Y.Z. (Yunfang Zha); Formal Analysis, Y.Z. (Yunfang Zha); Survey, Y.H., H.R. and Y.W.; Resources, Y.H.; Data Processing, Y.Z. (Yunfang Zha) and H.R.; First Draft Writing, Y.Z. (You Zou) and Z.F.; Review and Editing, X.J. and Y.H.; Visualization, Y.Z. (Yunfang Zha) and D.C.; Supervision, Y.H. and X.J.; Project Management, Y.H. and X.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China under the National Foreign Experts Project “Research on the Planning and Layout of Electric Vehicle Charging Facilities”, grant number G2023027008L, and by the Xiangyang Hubei University of Technology Industrial Research Institute under the project “Intelligent Design and Renovation of Industrial, XYYJ2023A07. Buildings”, grant number XYYJ2023A07 (Category A).

Data Availability Statement

The underlying data for this study can be found within the article. For further inquiries, please contact the corresponding author directly.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Hubei University of Technology for providing the testing equipment and for its valuable assistance during the model development process. All individuals mentioned in this section have expressly consented to being cited.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Nomenclature | Description |

| CDU | Charging Demand Unit |

| CFSR | Charging Facility Search Radius |

| CDI | Charging Demand Index |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| EVCI | Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure |

| POI | Point of Interest |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| ŪR | Aggregated Utilization Rate |

| Ďegree | Aggregated Degree Centrality |

References

- Wang, S.; Liu, D.; Yu, L.; Zhao, Q. A Multi-Stage Planning Method for Electric Vehicle Charging Facilities Considering the Coupling of Transportation and Distribution Networks Based on Data Envelopment Analysis. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2022, 42, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, X.-H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, R.-Y.; Jia, J.-W.; Chang, Z.-L.; Li, B.; Zhao, X. Collaborative Planning of Community Charging Facilities and Distribution Networks. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Guo, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, K. The Sequential Construction Research of Regional Public Electric Vehicle Charging Facilities Based on Data-Driven Analysis—Empirical Analysis of Shanxi Province. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 134948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Tu, J.; Lei, X.; Shao, Z.; Jian, L. A Cost-Effective and High-Efficient EV Shared Fast Charging Scheme with Hierarchical Coordinated Operation Strategy for Addressing Difficult-to-Charge Issue in Old Residential Communities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Ma, L.; Mao, Z.; Ou, X. Setting up Charging Electric Stations within Residential Communities in Current China: Gaming of Government Agencies and Property Management Companies. Energy Policy 2015, 77, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caulfield, B.; Furszyfer, D.; Stefaniec, A.; Foley, A. Measuring the Equity Impacts of Government Subsidies for Electric Vehicles. Energy 2022, 248, 123588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Weng, X.; Duan, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J. Bayesian Network Governance of Electric Vehicle Charging Pile Disordered Charging Load Impacts on the Grid. J. Combin. Math. Combin. Comput. 2025, 127, 7901–7921. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-W.; Fingerman, K. Public Electric Vehicle Charger Access Disparities across Race and Income in California. Transp. Policy 2021, 100, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Wang, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Dorrell, D.G.; Li, X. Battery Electric Vehicle Usage Pattern Analysis Driven by Massive Real-World Data. Energy 2022, 250, 123837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liu, L.; Peng, Z.; Wu, H.; Wang, F.; Jiao, H.; Wang, J. Planning Public Electric Vehicle Charging Stations to Balance Efficiency and Equality: A Case Study in Wuhan, China. Sustain. Cities Society 2025, 124, 106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xu, M.; Xing, Q.; Cui, L.; Jiao, L. A Fuzzy Demand-Profit Model for the Sustainable Development of Electric Vehicles in China from the Perspective of Three-Level Service Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harshil, B.; Nagababu, G. Strategies and Models for Optimal EV Charging Station Site Selection. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1372, 012106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronin, V.; Nepsha, F.; Ilyushin, P. A Demand Factor Analysis for Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, Z.; Luo, S. Location Optimization of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations: Based on Cost Model and Genetic Algorithm. Energy 2022, 247, 123437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. Public Charging Station Location Determination for Electric Ride-Hailing Vehicles Based on an Improved Genetic Algorithm. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ren, H.; Jia, X.; Yu, X.; Xie, D.; Zou, Y.; Chen, D.; Yang, Y. A Spatially Aware Machine Learning Method for Locating Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, D.; An, S.; Cai, H.; Wang, J.; Cai, H. An Optimization Model for Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Planning Considering Queuing Behavior with Finite Queue Length. J. Energy Storage 2020, 29, 101317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merhy, G.; Nait-Sidi-Moh, A.; Moubayed, N. A Multi-Objective Optimization of Electric Vehicles Energy Flows: The Charging Process. Ann. Oper. Res. 2021, 296, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitencourt, L.; Abud, T.P.; Dias, B.H.; Borba, B.S.M.C.; Maciel, R.S.; Quirós-Tortós, J. Optimal Location of EV Charging Stations in a Neighborhood Considering a Multi-Objective Approach. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2021, 199, 107391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazari, V.; Chassiakos, A. Multi-Objective Optimization of Electric Vehicle Charging Station Deployment Using Genetic Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolbertus, R.; Van Den Hoed, R.; Kroesen, M.; Chorus, C. Charging Infrastructure Roll-out Strategies for Large Scale Introduction of Electric Vehicles in Urban Areas: An Agent-Based Simulation Study. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2021, 148, 262–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Tan, J. A Data-Driven Approach of Layout Evaluation for Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Using Agent-Based Simulation and GIS. Simulation 2024, 100, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Sun, M. Using AHP-Entropy Method to Explore the Influencing Factors of Spatial Demand of EVs Public Charging Stations: A Case Study of Jinan, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 491, 144779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ji, Y.; Guo, Z.; Pei, H.; Zhou, Z. A Method for Allocation of Supply-Demand Equilibrium in Urban Electric Vehicles Shared Charging Facilities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 131, 106682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kong, H.; Lin, Z.; Dang, A. Mapping the Dynamics of Electric Vehicle Charging Demand within Beijing’s Spatial Structure. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Liu, R.; Li, M.; Tan, X.; Ma, P.; Zhang, H. An Approach to Optimizing the Layout of Charging Stations Considering Differences in User Range Anxiety. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 38, 101292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, C.; Zhang, X.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, K.; Yang, Y. Research on Charging Demands of Commercial Electric Vehicles Based on Voronoi Diagram and Spatial Econometrics Model: An Empirical Study in Chongqing China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 105, 105335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, Z.; Yang, P.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z. Electric Vehicle Charging Facility Planning Based on Flow Demand—A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, F.; Shuai, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Ouyang, X. Analysis of Charging Demands, Influencing Factors and Spatial Effects of Electric Vehicles Based on Multi-Source Data and Local Spatial Models. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Q.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, R.; Zhang, T. Modelling Driving and Charging Behaviours of Electric Vehicles Using a Data-Driven Approach Combined with Behavioural Economics Theory. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, W.; Bao, Y.; Yan, Y.; Yuan, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. Sequential Construction Planning of Electric Taxi Charging Stations Considering the Development of Charging Demand. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortimer, B.J.; Hecht, C.; Goldbeck, R.; Sauer, D.U.; De Doncker, R.W. Electric Vehicle Public Charging Infrastructure Planning Using Real-World Charging Data. World Electr. Veh. J. 2022, 13, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borlaug, B.; Yang, F.; Pritchard, E.; Wood, E.; Gonder, J. Public Electric Vehicle Charging Station Utilization in the United States. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 114, 103564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellrich, M.; Block, A.; Leikert-Böhm, N. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Electric Vehicle Charging Station Utilization: A Nationwide Case Study of Switzerland. Environ. Res. Infrastruct. Sustain. 2022, 2, 021003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Wu, F.; Cheng, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, J. A Large-Scale Empirical Study on Impacting Factors of Taxi Charging Station Utilization. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 118, 103687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; An, M.; Yuan, H.; Bao, X. Research on Complex Network Modeling of Building Materials Supply and Demand and Characteristics of Communities. Heliyon 2024, 10, e26766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xu, X. A Study on the Rationality of Electric Vehicle Charging Facility Layout Based on Complex Network Theory. Technol. Econ. 2017, 36, 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Le, W.; Guo, B. Research on the Utilization Efficiency of New Energy Vehicle Charging Facilities Based on Complex Networks. Manag. Rev. 2021, 33, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiao, J.; Tang, Y. An Evolutionary Analysis on the Effect of Government Policies on Electric Vehicle Diffusion in Complex Network. Energy Policy 2019, 129, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wei, W.; Mei, S.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S. Promoting Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Considering Policy Incentives and User Preferences: An Evolutionary Game Model in a Small-World Network. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 258, 120753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Fan, R.; Wang, D.; Yao, Q. Effects of Multiple Incentives on Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure Deployment in China: An Evolutionary Analysis in Complex Network. Energy 2023, 264, 125747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Ji, S.; Wang, H.; Jiang, L. How Do Government Subsidies Promote New Energy Vehicle Diffusion in the Complex Network Context? A Three-Stage Evolutionary Game Model. Energy 2021, 230, 120899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Lin, Y.; Lim, M.K.; Zhou, F.; Liu, F. Electric Vehicle Charging Station Diffusion: An Agent-Based Evolutionary Game Model in Complex Networks. Energy 2022, 257, 124700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H. Research on the Layout Method of Public Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in the Central Urban Area of Xi’an. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abotalebi, E.; Ferguson, M.R.; Mohamed, M.; Scott, D.M. Design of a Survey to Assess Prospects for Consumer Electric Mobility in Canada: A Retrospective Appraisal. Transportation 2020, 47, 1223–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.; Ma, J.; Wei, R.; Haycox, J. Electric Vehicle Charging Point Placement Optimisation by Exploiting Spatial Statistics and Maximal Coverage Location Models. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 67, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metais, M.O.; Jouini, O.; Perez, Y.; Berrada, J.; Suomalainen, E. Too Much or Not Enough? Planning Electric Vehicle Charging Infrastructure: A Review of Modeling Options. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 153, 111719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fu, Z.-L.; Guo, W.; Liang, R.-Y.; Shao, H.-Y. What Influences Sales Market of New Energy Vehicles in China? Empirical Study Based on Survey of Consumers’ Purchase Reasons. Energy Policy 2020, 142, 111484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Huang, X. Screening of Urban Environmental Vulnerability Indicators Based on Coefficient of Variation and Anti-Image Correlation Matrix Method. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the Methodological Framework of Composite Indices: A Review of the Issues of Weighting, Aggregation, and Robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Q.; Schonfeld, P. Prediction of Charging Requirements for Electric Vehicles Based on Multiagent Intelligence. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 2309376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Hongshan District.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of Hongshan District.

Figure 2.

Methodological Framework.

Figure 2.

Methodological Framework.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of residential in Hongshan District.

Figure 3.

Spatial distribution of residential in Hongshan District.

Figure 4.

Spatial Units for Charging Demand in Residential.

Figure 4.

Spatial Units for Charging Demand in Residential.

Figure 5.

Factors affecting charging demand. (a) Electric vehicle ownership. (b) Road density. (c) Density of consumer-related POI. (d) Transportation hub density. (e) Population density. (f) Parking density.

Figure 5.

Factors affecting charging demand. (a) Electric vehicle ownership. (b) Road density. (c) Density of consumer-related POI. (d) Transportation hub density. (e) Population density. (f) Parking density.

Figure 6.

Residential Charging Demand Index.

Figure 6.

Residential Charging Demand Index.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of charging facility utilization rate.

Figure 7.

Spatial distribution of charging facility utilization rate.

Figure 8.

Construction of the Residential Area–Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network. (a) Residential Area-Charging Facility Collaborative Service Relationship. (b) Bipartite network matrix B: Q1*0.8 means that the charging demand of residential area Q1 is 0.8. (c) Counting cooperative network matrix C. (d) Weighted demand collaborative network matrix W.

Figure 8.

Construction of the Residential Area–Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network. (a) Residential Area-Charging Facility Collaborative Service Relationship. (b) Bipartite network matrix B: Q1*0.8 means that the charging demand of residential area Q1 is 0.8. (c) Counting cooperative network matrix C. (d) Weighted demand collaborative network matrix W.

Figure 9.

Residential Area–Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network.

Figure 9.

Residential Area–Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network.

Figure 10.

Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network.

Figure 10.

Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network.

Figure 11.

Spatial Distribution of k-core.

Figure 11.

Spatial Distribution of k-core.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of clustering coefficient.

Figure 12.

Spatial distribution of clustering coefficient.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of degree centrality.

Figure 13.

Spatial distribution of degree centrality.

Figure 14.

Spatial distribution of intermediate centrality.

Figure 14.

Spatial distribution of intermediate centrality.

Figure 15.

Determination of the optimal number of clusters.

Figure 15.

Determination of the optimal number of clusters.

Figure 16.

Clustering results of supply and demand structure of charging facilities in residential areas.

Figure 16.

Clustering results of supply and demand structure of charging facilities in residential areas.

Figure 17.

Correlation analysis of clustering results.

Figure 17.

Correlation analysis of clustering results.

Table 1.

Factors affecting charging demand and their explanation.

Table 1.

Factors affecting charging demand and their explanation.

| Charging Demand Indicators | Unit | Indicator Meaning | Calculation Formula | Formula Explanation |

|---|

| Population density | People per square kilometer | Population within the land area of each charging demand unit | | P: Total Population

Pr: Total Population of the Region

A: Area of the Region (km2)

Npk: Number of Parking Lots

Lroad: Total Road Length

D/S/R: Number of Points of Interest (POIs) for Dining/Shopping/Leisure

H: Number of Points of Interest (POIs) for Transportation Hubs

Ee: Number of Electric Vehicles in the Region

Oe: Number of Electric Vehicles in the City |

| Parking density | Units per square kilometer | Number of parking lots within each charging demand unit | |

| Road density | km/km2 | The ratio of the total road network mileage to the area of each charging demand unit | |

| Density of consumer-related POI | People per square kilometer | Number of catering services, shopping services, and leisure and entertainment points of interest within each charging demand unit | |

| Transportation hub density | Units per square kilometer | Number of points of interest at transportation hubs within each charging demand unit | |

| Electric vehicle ownership | vehicle | Electric vehicle fleet within each charging demand unit | |

Table 2.

Calculation and analysis of the weights of influencing factors based on the CV method.

Table 2.

Calculation and analysis of the weights of influencing factors based on the CV method.

| Charging Demand Indicator | Mean (μ) | Std. Dev. (σ) | CV | Weight | VIF | Collinearity Assessment |

|---|

| Population density | 10,976.006 | 6742.410 | 0.614 | 0.049 | 1.044 | None |

| Parking density | 0.776 | 1.784 | 2.300 | 0.183 | 3.885 | Mild |

| Road density | 2.544 | 4.884 | 1.920 | 0.153 | 1.010 | None |

| Density of consumer-related POI | 8.026 | 21.542 | 2.684 | 0.214 | 1.122 | None |

| Transportation hub density | 0.374 | 1.675 | 4.479 | 0.356 | 3.632 | Mild |

| Electric vehicle ownership | 0.584 | 0.337 | 0.576 | 0.046 | 1.031 | None |

Table 3.

Selection and Interpretation of Analysis Indicators for Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network.

Table 3.

Selection and Interpretation of Analysis Indicators for Charging Facility Collaborative Service Network.

| Network Characteristics | Indicator | Meaning in the Collaborative Service Network of Charging Facilities |

|---|

| Overall Characteristics | Network Density | Represents the completeness of actual connectivity between all charging facilities in the region. The higher the density, the stronger the overall network integrity, and the closer the collaborative service relationships between facilities. |

| Local Characteristics | k-core | Identifies the core–periphery hierarchical structure of the network. Facility groups with a high k-core value form the core hubs of the service network, characterized by stable connections and strong collaborative service capability. |

| Clustering Coefficient | Measures the closeness of facilities within a local neighborhood. A high clustering coefficient indicates that multiple facilities are closely adjacent, forming a service cluster that can provide more reliable collaborative services to the covered area. |

| Individual Characteristics | Degree Centrality | Measures the number of direct connections a single facility node has. The higher the value, the more facilities the charging facility jointly serves, indicating greater attraction and direct influence. |

| Betweenness Centrality | Identifies key facilities on which the network’s connectivity relies. The higher the value, the stronger the network’s dependency on that node for connectivity. If it fails, it will significantly disrupt the connections between different facility clusters and reduce the service accessibility of the entire area. |

Table 4.

The k-core decomposition results.

Table 4.

The k-core decomposition results.

| k-Core | Number of Facilities | Proportion (%) | Structural Role and Characteristics |

|---|

| 0 | 147 | 51.2 | Peripheral Facilities, Not integrated into the collaborative network. |

| 15–35 | 65 | 22.7 | Transitional Layer Facilities, Limited collaborative capacity. |

| 58–64 | 75 | 26.1 | Core Layer Facilities, Form the backbone of the service network. |

| 65 | 66 | 23.0 | Most Core Group, Most tightly connected. |

Table 5.

Analysis of the top 10 facilities in terms of centrality ranking.

Table 5.

Analysis of the top 10 facilities in terms of centrality ranking.

| Ranking | Facility ID | Degree Centrality | Ranking | Facility ID | Betweenness Centrality |

|---|

| 1 | S4 | 0.2657 | 1 | S136 | 0.1407 |

| 1 | S195 | 0.2657 | 2 | S195 | 0.1208 |

| 3 | S61 | 0.2587 | 3 | S37 | 0.1187 |

| 4 | S52 | 0.2552 | 4 | S123 | 0.0801 |

| 4 | S156 | 0.2552 | 5 | S190 | 0.0488 |

| 4 | S157 | 0.2552 | 5 | S243 | 0.0488 |

| 4 | S185 | 0.2552 | 7 | S78 | 0.0196 |

| 4 | S186 | 0.2552 | 8 | S242 | 0.0128 |

| 9 | S13 | 0.2483 | 9 | S56 | 0.0121 |

| 9 | S14 | 0.2483 | 10 | S38 | 0.0106 |

Table 6.

Supply and demand structure type analysis.

Table 6.

Supply and demand structure type analysis.

| Cluster Type | CDI | ŪR | Ďegree | Number of Districts | Percentage (%) | Core Feature Description |

|---|

| Type I: Efficient Collaborative | High | High | High | 341 | 23.6% | Strong demand, full utilization of facilities, and strong network synergy create a virtuous cycle. |

| Type II: Transitional Mixed | Medium | Medium | Medium | 948 | 65.5% | All dimensions are at a moderate level, representing the transitional and main parts of the system. |

| Type III: Low-Demand Marginal | Low | Low | Low | 156 | 10.9% | Both demand and supply are at low levels, and the network is becoming marginalized. |

Table 7.

Second-order cluster analysis of “transitional mixed” residential areas.

Table 7.

Second-order cluster analysis of “transitional mixed” residential areas.

| Sub-Class | Sample Size | Proportion (Within Type II) | Core Characteristics | Main Diagnostic Issues |