Abstract

Heavy-duty trucking is central to the U.S. economy, and improving its long-term sustainability requires cost-effective, energy-efficient, and reliable operations. Emerging technologies—advanced powertrains, batteries, and alternative fuels—offer potential solutions, but their economic and operational viability remains uncertain. This study evaluates the performance of Class 8 battery electric (BEV), plug-in hybrid (PHEV), fuel cell electric (FCEV), and diesel trucks in terms of energy use and the levelized cost of driving (LCOD) to determine when these technologies become competitive without compromising operational reliability. The analysis explores how evolving fuel prices and vehicle technology improvements in 2023, 2035, and 2050 influence the cost competitiveness of each powertrain. By comparing the results at both the technology level and the fleet level, the study demonstrates that powertrains that appear cost-effective on individual routes may not always scale to fleet-wide viability, and vice versa. The analysis is based on real-world data from over 15,700 Class 8 truck trips recorded in California in 2022, capturing diverse driving scenarios, payload conditions, and operational constraints. The results show that BEV250 can deliver cost-effective performance in short-haul operations (0–250 miles) under depot electricity prices below USD 0.34/kWh and maintain this advantage through 2050 as battery costs decline. In the 250–500-mile segment, the technology-level analysis indicates that BEV500 often achieves the lowest LCOD on individual tours, particularly under low electricity prices, while the fleet-level results show that FCEVs provide a more consistent cost performance across all tours, especially when the route variability is high. For long-haul operations (>500 miles), where BEVs are assumed to operate without en-route charging, FCEVs emerge as the most cost-effective non-diesel option by 2050, provided hydrogen prices fall below USD 6/kg. PHEVs show a limited long-term competitiveness and are mainly viable under transitional fuel price conditions. Overall, the findings underscore that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Powertrain adoption must be range-aware, infrastructure-sensitive, and fleet-structured. By integrating technology-level and fleet-level perspectives, this study provides actionable insights for fleet operators, policymakers, and industry stakeholders seeking to balance cost, reliability, and sustainability in heavy-duty freight.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the trucking sector, a critical backbone of the U.S. freight economy, has accounted for a disproportionately high share of national fuel consumption relative to its share of total vehicle miles traveled, reflecting its energy-intensive nature and operational importance [1]. As freight demand continues to grow, there is an urgent need to advance technologies that reduce operating costs, improve energy efficiency, and support domestic energy resilience. These needs are particularly pressing as the country seeks to enhance energy affordability, reduce supply chain vulnerabilities, and stimulate economic growth.

To this end, significant research efforts have been directed toward developing advanced powertrain technologies such as power-split hybrid electric trucks (HEVs), plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs), battery electric vehicles (BEVs), and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). These technologies have the potential to lower the total cost of ownership, reduce the dependence on imported fossil fuels, and improve the reliability of freight operations, all of which are essential to ensuring long-term energy security and cost-effective freight mobility. However, determining the most viable and scalable solution for heavy-duty trucking applications remains complex and requires robust analysis.

Several studies have assessed the feasibility of advanced powertrain technologies for freight trucks across both vehicle and fleet levels. Joshi et al. (2021) conducted a simulation-based study on hybrid, electric, and fuel cell powertrains for Medium Heavy-Duty Vehicles, finding significant long-term savings potential with range extenders and electric trucks [2]. Vijayagopal et al. (2021) explored the total ownership cost sensitivity for medium and heavy-duty electric trucks, identifying cost targets for battery packs and potential use cases for early technology adoption [3]. In contrast, Haddad et al. (2019) took a fleet-level approach, using system dynamics modeling to assess energy use and emissions from various vehicle types [4]. Their findings highlighted the need to accelerate the transition to energy-efficient technologies to meet broader system-level and economic goals.

Recent studies have advanced cost and performance modeling by integrating empirical data with comparative techno-economic analysis across emerging powertrain and energy strategies. Sader et al. (2025) [5] evaluated battery electric long-haul trucking in the U.S. and found that, while overnight charging and battery technology show a strong long-term potential, achieving cost competitiveness with diesel will require continued reductions in electricity prices, improvements in charging infrastructure, and advances in battery energy density to minimize payload penalties and operational costs. Bai et al. (2025) [6] analyzed renewable hydrogen, methanol, and ammonia systems for Class 8 trucks, showing that, although battery electric pathways offer strong energy efficiency, alternative fuels may become viable for long-range operations in regions where electricity remains costly. Mu et al. (2024) [7] compared battery electric and fuel cell trucks in China, finding that the relative cost-effectiveness of each depends on local energy markets and fuel infrastructure availability. Expanding the regional scope, Basma and Rodriguez (2023) [8] assessed the total cost of ownership and energy use for diesel, electric, and hydrogen trucks in Europe, projecting that electric powertrains could achieve cost competitiveness by the early 2030s, though outcomes depend heavily on policy support and energy price trends. While these studies provide valuable cost and energy benchmarks, they primarily focus on vehicle- or fleet-level analysis and often overlook the operational variability and infrastructure dynamics needed to inform system-level planning for affordability and reliability.

Similarly, some studies have begun integrating real-world freight activity data to improve the realism of vehicle and fleet modeling frameworks. Sun et al. (2024) [9] developed a total cost of ownership model calibrated with actual operational and financial data from freight fleets, revealing a substantial cost variation across technologies depending on route characteristics and regional energy prices. Complementing this, a growing body of research addresses the broader infrastructure, energy system, and policy context for emerging freight technologies, often through system-level models. Ledna et al. (2024) [10] developed a total cost of driving framework that incorporates grid dynamics and energy reliability considerations, identifying key levers for scaling electric and hydrogen trucks without compromising grid stability. Anderson et al. (2024) [11] examined freight electrification under utility-scale constraints, showing how spatial misalignments between freight routes and grid capacity can affect long-term investment strategies. Lehmann and Winkenbach (2025) [12] added a planning perspective by modeling how uncertainty in future energy costs influences infrastructure deployment and technology selection.

While these studies contribute critical insights into system-wide constraints and opportunities, they often abstract away from the granular variability in trip characteristics, payloads, and terrain that influence real-world truck performance. Moreover, there remains a lack of large-scale, real-world analyses that holistically compare advanced truck technologies in terms of both operational cost and system-level benefits. Addressing this gap is essential to support more reliable, affordable, and energy-secure freight planning across diverse operating conditions. This study seeks to address that gap by evaluating the cost and energy performance of alternative Class 8 powertrain technologies under real-world operating conditions. Using trip data from over 15,700 Class 8 trips recorded in California, this analysis captures variations in payloads, terrains, and duty cycles. By leveraging high-fidelity simulation tools that account for infrastructure readiness, technology trends, and fuel pricing dynamics, this study provides critical insights into how emerging powertrain technologies can support national goals around cost-effective, reliable, and energy-secure freight solutions in the near and long term.

This study is particularly relevant for fleet operators, manufacturers, and policymakers seeking actionable insights to guide technology investment and deployment decisions. By analyzing extensive real-world operational data and projecting performance across multiple future timeframes, it offers a granular understanding of the economic and environmental trade-offs involved in adopting advanced truck powertrains. This knowledge enables stakeholders to identify when these technologies can become cost-competitive and operationally reliable without compromising freight efficiency, helping to mitigate risks and capitalize on emerging market opportunities.

The novelty of this work lies in its holistic assessment that integrates cost-effectiveness, energy consumption, and operational constraints under realistic market scenarios. Unlike previous studies with narrower scopes or idealized assumptions, this analysis provides a robust foundation for evaluating the timing and conditions under which electrification and alternative fuels can reshape the heavy-duty trucking sector, contributing to a more resilient, affordable, and competitive freight system.

Throughout this paper, all vehicle references correspond to Class 8 freight trucks. Class 8 truck powertrain technologies in this study refer to heavy-duty tractor configurations with a GVWR above 33,000 lbs, commonly used for regional-haul and long-haul freight operations. For consistency, we use the abbreviations HEV (hybrid electric vehicle), PHEV (plug-in hybrid electric vehicle), BEV (battery electric vehicle), and FCEV (fuel cell electric vehicle) to refer to the respective Class 8 truck configurations.

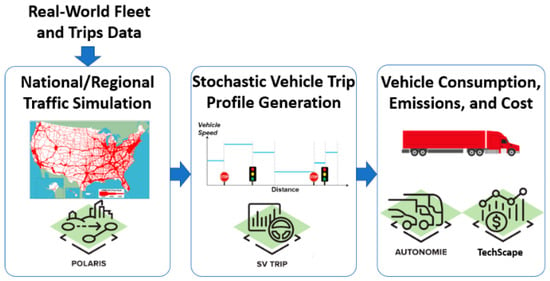

2. Methodology

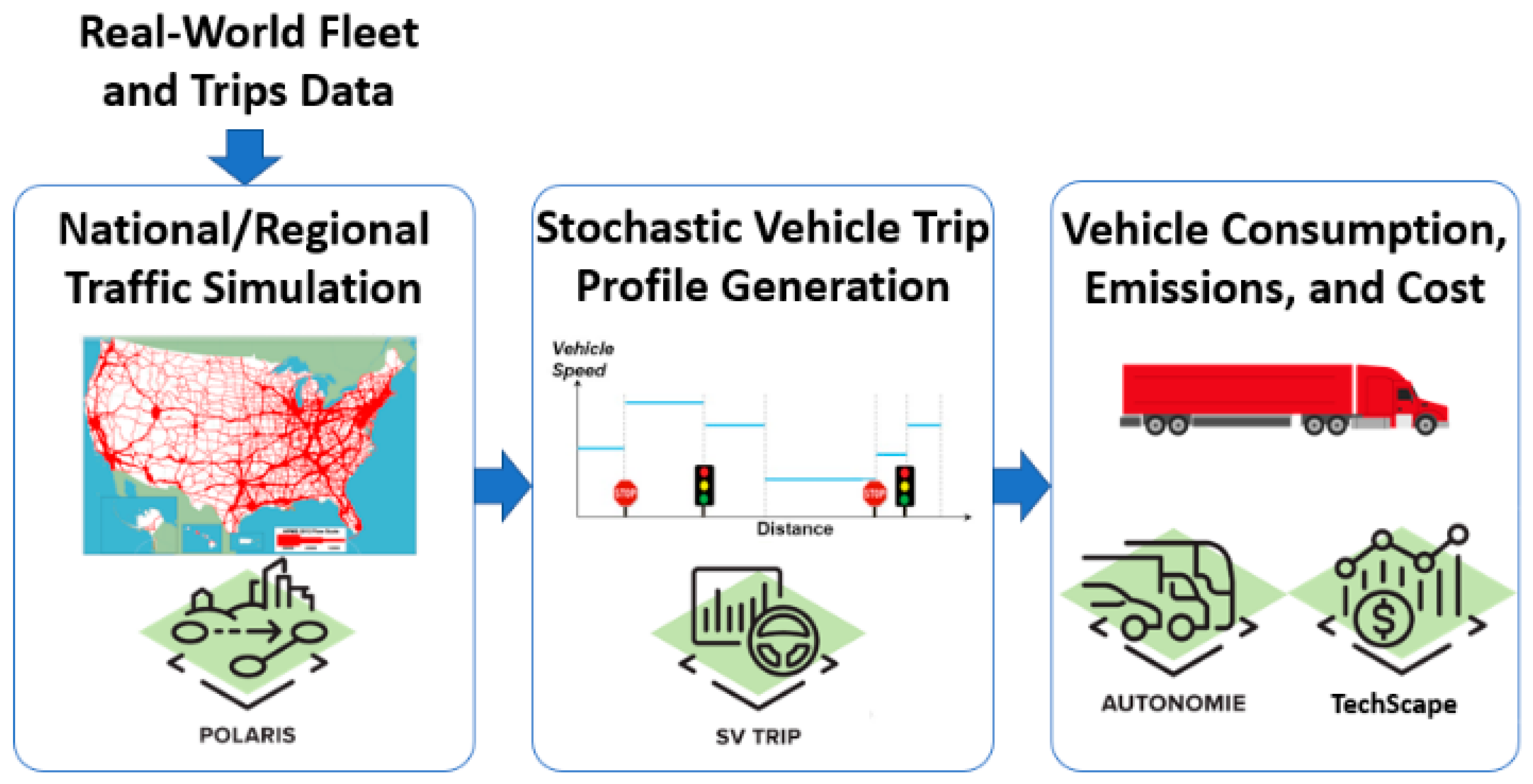

This study follows a multi-step workflow for evaluating the techno-economic and environmental performance of alternative truck powertrains. The workflow, depicted in Figure 1, integrates multiple advanced simulation tools developed at Argonne National Laboratory, each addressing a key aspect of the transportation energy system.

Figure 1.

Workflow for techno-economic evaluation of advanced truck technologies.

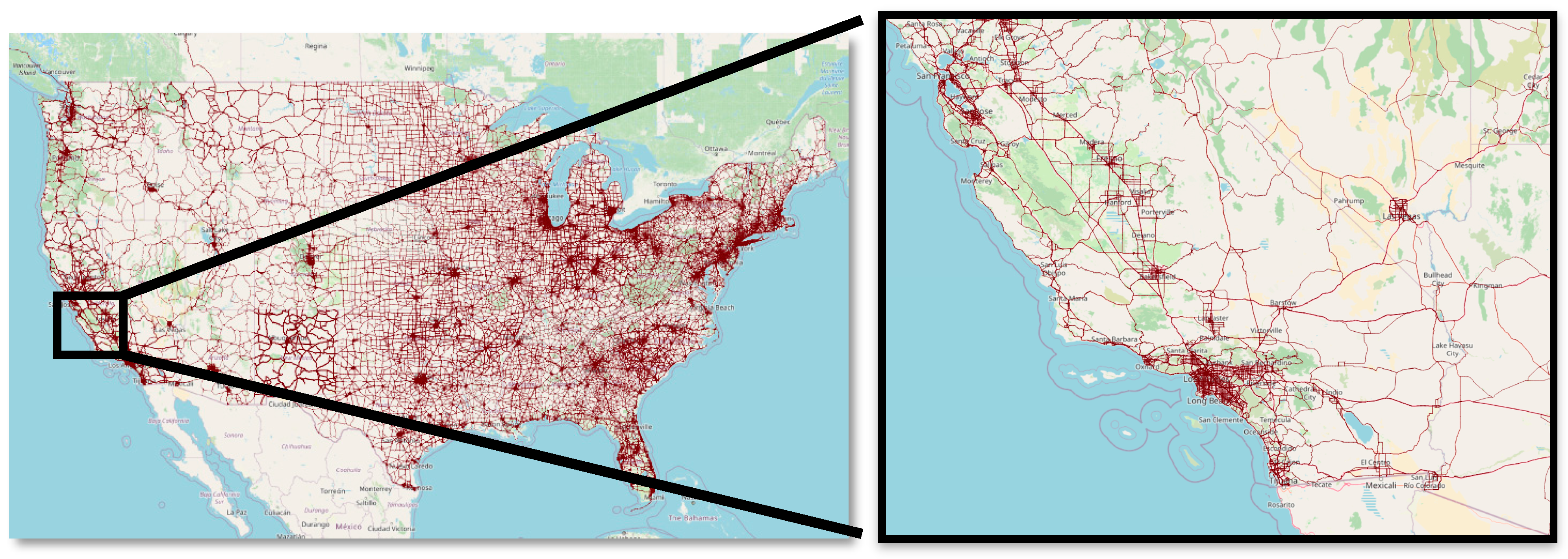

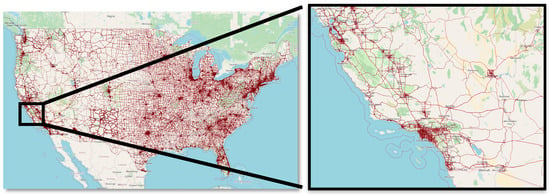

First, the transportation system is represented using POLARIS [13], an agent-based modeling tool that captures travel demand, network conditions, and vehicle operations. The national POLARIS network used in this study consists of 132 zones and over 600,000 roadway links and nodes, as illustrated in Figure 2. This network is used to model freight trips based on origin–destination data derived from real-world operations in California.

Figure 2.

POLARIS national network representation. Note that background map is sourced from Google maps.

2.1. POLARIS for Transportation System Modeling

The simulated routes are then passed to the Stochastic Vehicle Trip Prediction (SVTriP) model [14], which generates high-fidelity, naturalistic vehicle speed profiles for each trip. SVTriP has been trained on large datasets of recorded heavy-duty vehicle driving behavior to ensure a realistic representation of vehicle dynamics under varying traffic and road conditions.

Next, vehicle energy consumption is evaluated using Autonomie [15], a detailed vehicle simulation tool that models powertrain components, vehicle longitudinal dynamics, and control strategies. Each simulated trip is evaluated using Autonomie to estimate the fuel or electricity consumption for different truck powertrain technologies.

Subsequently, the Technology Landscape (TechScape) tool [16] is used to calculate the levelized cost of driving (LCOD) for each truck technology. TechScape integrates cost data, operational assumptions, and simulation outputs from Autonomie to provide lifecycle economic and environmental performance indicators.

To generate realistic freight movement patterns, twelve months of operational data were obtained from a logistics company operating in California. This dataset includes 15,743 individual trips recorded by trucks engaged in predominantly regional operations. Each record contains the following attributes: (1) a unique identification number for each truck, (2) the date and time of operations, (3) details regarding the origin and destination addresses of the trips, (4) the type of truck operations performed, which is determined based on the tasks carried out and the resulting status of the trailer or truck (e.g., dropping off or picking up a trailer, operating with an empty trailer, among others), and (5) the payload mass at trip start.

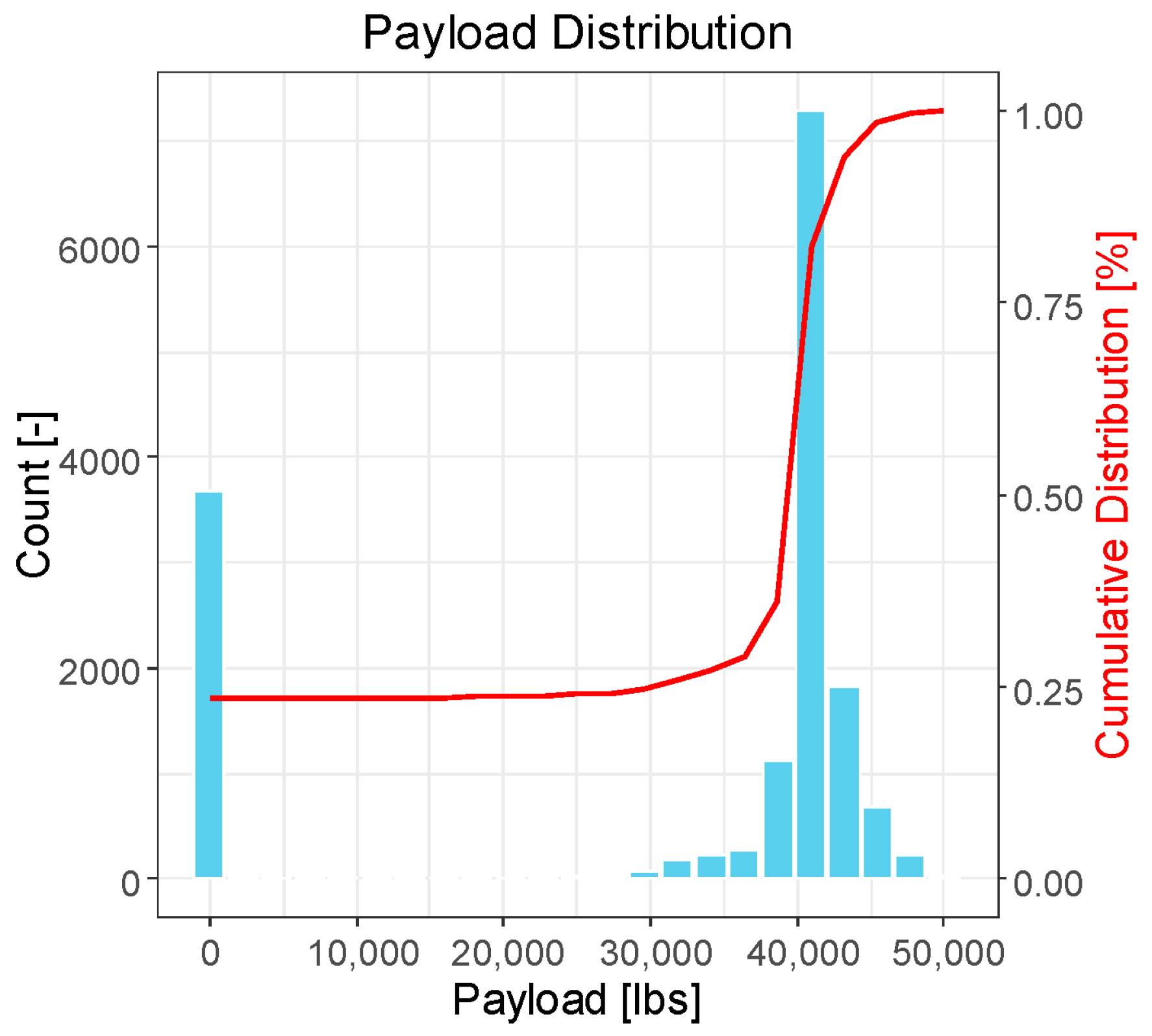

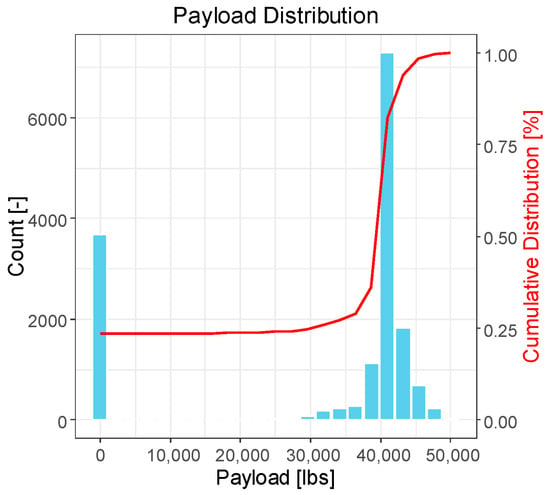

Prior to integration into POLARIS, the dataset underwent a comprehensive data cleaning process. Address fields were corrected for typographical errors and geocoded using the Google Maps API to ensure spatial accuracy. Approximately 1% of trips had missing payload values; these were imputed using a predictive model developed from the observed payload distribution, shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Distribution of payloads across all simulated trips.

Each cleaned trip was simulated in POLARIS using its geocoded origin and destination. The simulation generates a vehicle trajectory composed of network links (average segment length: ~1 km), with an associated average speed for each link. These trajectories serve as inputs to the SVTriP model to produce continuous speed profiles for energy simulation.

To evaluate the realistic daily energy demand and cost-effectiveness of truck operations, all trips conducted by the same vehicle within a single calendar day are aggregated into daily operational tours to assess technology feasibility under realistic operational cycles. Using the unique truck identifier and timestamp information from the logistics dataset, trips were aggregated chronologically to reflect continuous operation. The full battery or fuel level was assumed only at the beginning of the first trip in the tour, while energy depletion and payload mass were tracked across the tour for consistency. This methodology ensures a realistic representation of range constraints, charging and refueling strategies, daily energy usage, and operational feasibility.

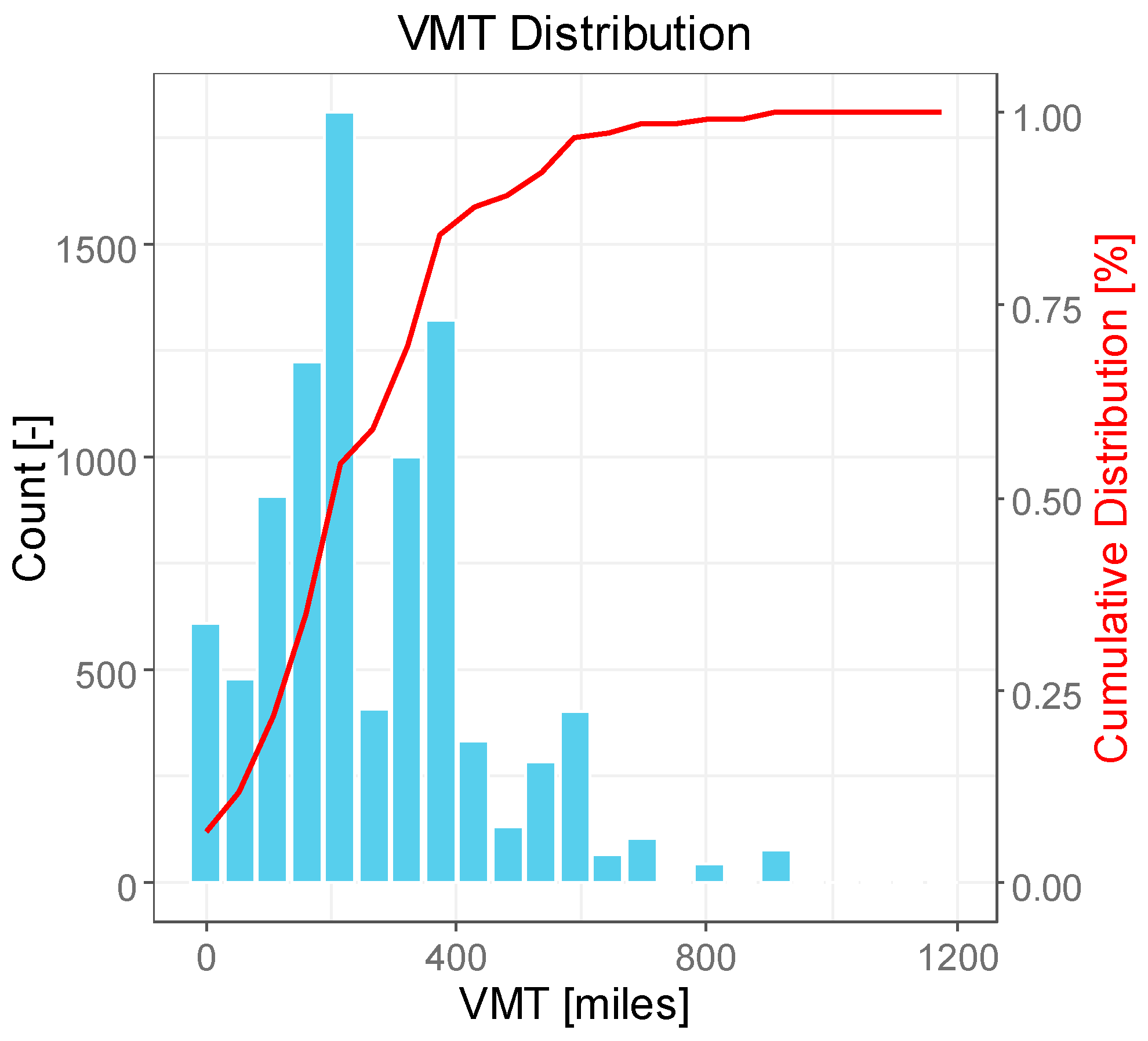

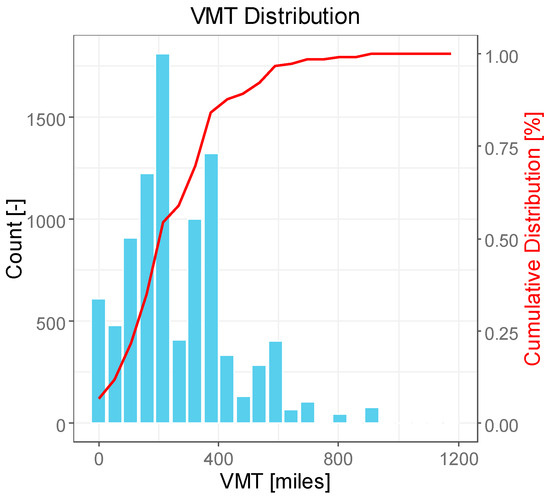

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of payloads across all simulated trips, showing distinct peaks at 0 and 40,000 lbs, indicating that most trips are either lightly loaded or near full capacity. Figure 4 presents the corresponding distribution of the tour distances in terms of vehicle miles traveled (VMT). The analysis shows that most tours consist of two trips: an outbound trip followed by a return to the origin. Some tours include only a single trip, while others consist of three trips in a day. Overall, more than 60% of the tours are under 300 miles, which aligns with typical regional-haul operations. However, a subset of trips exceeds 400 miles, representing long-haul operations within the dataset.

Figure 4.

Distribution of tour distances in vehicle miles traveled based on the twelve-month dataset.

2.2. SVTriP for Trip Profile Generation

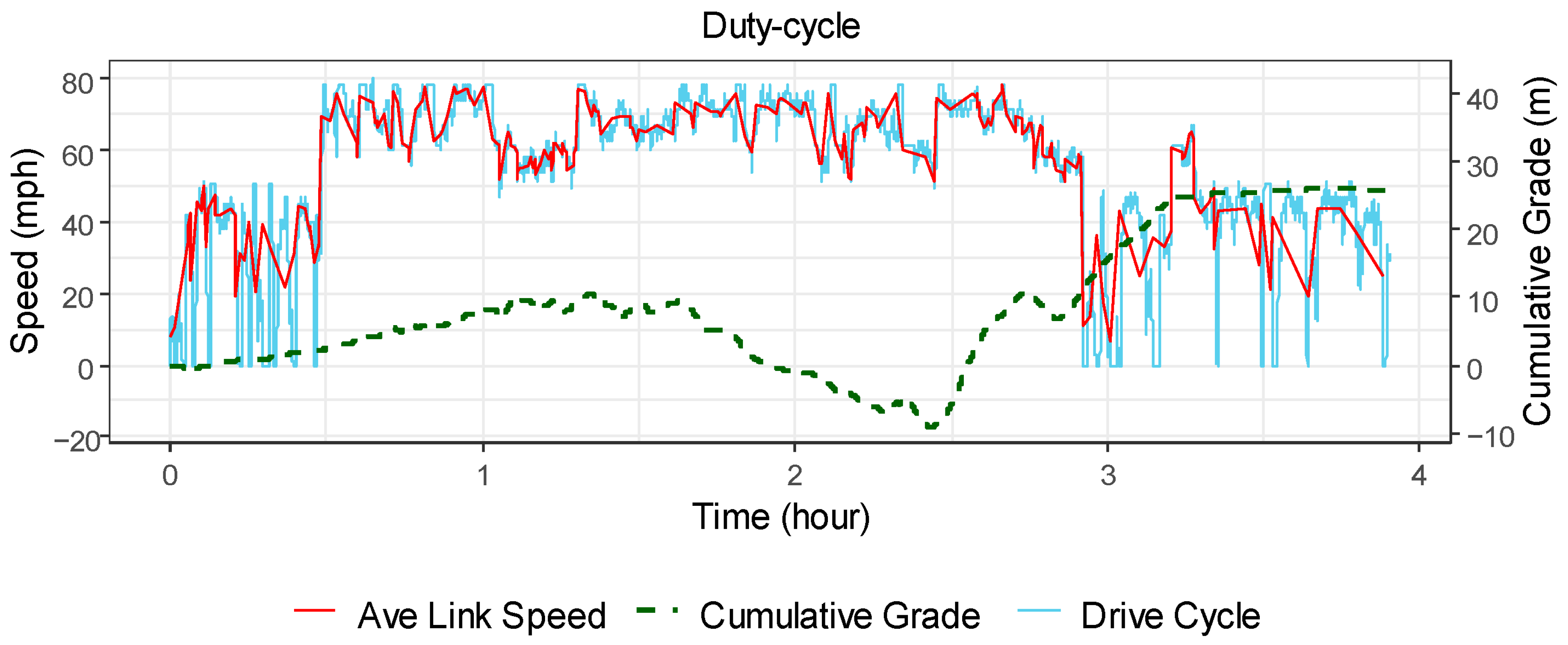

The Stochastic Vehicle Trip Prediction (SVTriP) tool was used to generate detailed driving cycles, i.e., time-resolved velocity profiles, for each freight trip simulated in POLARIS. These driving cycles emulate real-world vehicle operation by capturing speed variability due to congestion, traffic control, and driver behavior. SVTriP uses the sequence of roadway links and associated average speeds from POLARIS as inputs to synthesize second-by-second velocity trajectories for each trip.

In addition to velocity profiles, road grade was derived for each trip, as changes in elevation significantly influence vehicle energy use, especially for heavy-duty trucks. Grade profiles were computed by mapping each link’s geospatial coordinates to a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) obtained from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Elevation change over each link was used to calculate the longitudinal grade.

To ensure the reliability of DEM-derived grades, a validation exercise was conducted. Over 6000 origin–destination (OD) pairs were randomly sampled, and, for each, the corresponding roadway segment grades were retrieved using the HERE API [17], which provides commercial-grade elevation and routing data. A linear regression analysis between the DEM- and HERE-derived grades showed a high degree of agreement (R2 = 0.999), validating the use of DEM data for grade estimation across the simulated network.

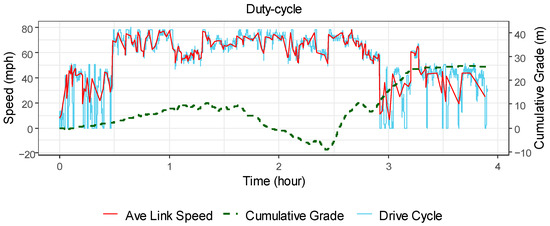

An illustrative driving cycle output from SVTriP, including velocity and grade profiles, is shown in Figure 5. These profiles serve as critical inputs to downstream vehicle energy consumption simulations in Autonomie, enabling a realistic assessment of the impact of topography and driving behavior on truck performance.

Figure 5.

Example SVTriP-generated driving cycle, showing time-resolved velocity and corresponding grade profiles used in energy simulation.

2.3. Autonomie for Energy Consumption Evaluation

Autonomie was used to assess the energy consumption of the investigated truck powertrains. Each powertrain was simulated across the set of tours, and the resulting energy consumption was benchmarked against a baseline diesel powertrain.

The simulations were conducted for model years 2023, 2035, and 2050 using a regional daycab truck configuration for tours less than 250 miles and long-haul sleeper truck for tours exceeding 250 miles. For each year, vehicle models were developed using a two-step framework: (1) collecting assumptions on the evolution of vehicle characteristics and component technologies; and (2) constructing detailed vehicle models in Autonomie, including powertrain component sizing based on performance-driven algorithms [18]. The sizing ensured that each powertrain variant met or exceeded conventional truck performance without trade-offs, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Class 8 trucks performance requirements.

The underlying assumptions reflect input from analysts and technology managers at the U.S. DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office (VTO) and Hydrogen and Fuel Cell Technologies Office (HFTO), supplemented by expert reviews from truck OEMs, fleet operators, and 21CTP partners [19]. These assumptions, summarized in Table 2, capture projected advancements in aerodynamics, rolling resistance, component efficiency, and battery specific energy for 2035 and 2050. The scenario reflects an accelerated technology progress trajectory, enabled by sustained policy support, targeted investments, and industry innovation. It assumes substantial improvements in powertrain efficiency, vehicle design, lightweighting, and energy storage performance in line with DOE research and commercialization targets.

Table 2.

Summary of assumptions for 2035 and 2050 Class 8 trucks.

The resulting truck models’ parameters are summarized in Table 3. These include improvements in the trucks specifications in 2035 and 2050 as compared to 2023, such as reductions in the drag coefficient, rolling resistance, and glider mass, as well as improvements in the powertrain component performance such as the improved efficiency of engines, electric machines, and fuel cell systems, as well as an increase in battery specific energy, among others. For more technical details on component evolution, see [19].

Table 3.

Summary of specifications for Class 8 trucks, model years 2023, 2035, and 2050.

In addition to the previously mentioned assumptions, there were other considerations made in the simulation. For each trip, Autonomie updates the total truck mass by adding the trip-specific payload to the glider and powertrain component masses, while ensuring the combined mass does not exceed the maximum allowable limit of 36,287 kg. The payload remains constant over a trip unless the logistics record indicates a pick-up or drop-off event. This dynamic mass directly affects rolling resistance, grade-related power demand, and acceleration loads. Moreover, for electrified trucks, it was assumed that the battery would be fully charged at the beginning of each trip, with an initial battery state of charge as defined in Table 3.

2.4. TechScape for Techno-Economic Analysis

Based on the energy consumption results obtained from Autonomie, TechScape is utilized to quantify the levelized cost of driving (LCOD) for the examined truck technologies. In general, LCOD calculations using TechScape encompass various factors, including financing, fuel costs, insurance, maintenance and repair, operation, taxes and fees, and the vehicle’s retail price. However, for this study, only the vehicle’s retail price and the cost of fuel are considered and referred to as the levelized cost of driving, as presented in Equation (1). Other cost components, such as maintenance, insurance, or potential charging and hydrogen access fees, are excluded. These costs could influence comparative results; for example, BEVs typically have lower maintenance requirements, whereas FCEVs may incur additional service or fueling-related costs depending on regional infrastructure availability. A full total cost of ownership analysis is outside the scope of this work but represents an important direction for future research.

The retail prices of the trucks for the years 2023, 2035, and 2050 are provided in Table 4, and the costs of the internal combustion battery and fuel cell per unit of power in 2023, 2035, and 2050 are presented in Table 5. Retail prices for 2035 and 2050 are derived using component-level cost projections from Islam et al. [19,20]. These include future estimates of battery USD/kWh, fuel cell USD/kW, engine efficiency improvements, and glider lightweighting.

Table 4.

Class 8 daycab and sleeper truck retail prices.

Table 5.

Internal combustion engine, battery, and fuel cell costs per unit of power.

Battery degradation effects, such as cycle aging, thermal exposure, and depth-of-discharge impacts, are not modeled explicitly in this LCOD framework due to the substantial variability across real-world operating conditions. LCOD values therefore represent cost performance under the assumption of stable battery capacity over the vehicle lifetime. Incorporating battery-aging effects into future techno-economic assessments is an important direction for further research.

where is the year,

is the cost in year “i”,

is the discount rate,

is the vehicle miles traveled at year “i”.

2.5. Operational Evaluation and Analysis Framework

BEVs, unlike their diesel counterparts, are constrained by fixed onboard energy storage, which limits their tour distance and makes flexible redeployment across varying daily routes more difficult, a common requirement in freight operations. To reflect these operational realities, we classified truck tours into three range bins based on real-world BEV capabilities:

- ▪

- 0–250 miles,

- ▪

- 250–500 miles,

- ▪

- 500+ miles.

This range-based classification allows for a fair and feasible comparison of performance and cost across powertrain types, ensuring that BEVs are only evaluated in deployment scenarios within their expected range limits. BEVs are assumed to start each tour with a full charge and complete the daily driving cycle without en-route fast charging. This reflects the current limitations in heavy-duty charging infrastructure and aligns with typical regional-haul operations, especially for depot-based fleets. Because en-route megawatt charging is not modeled, the BEV results presented here apply only to depot charging fleets and regional-haul applications. For long-haul operations, future work should incorporate one or more en-route MW charging events, including dwell time, demand charge, and operational constraint effects, to more completely evaluate BEV feasibility beyond the 500-mile range.

To assess the economic and environmental implications of powertrain selection across these range categories, we evaluated 43 trucks completing more than 9000 tours over a 12-year service life. For each tour, energy consumption and the levelized cost of driving (LCOD) were computed using the integrated simulation workflow described earlier (POLARIS, SVTriP, Autonomie, and TechScape).

We conducted two types of LCOD-based sensitivity analyses to evaluate powertrain performance under a variety of energy price conditions:

- ▪

- Technology-Level Cost Analysis: This analysis evaluates each powertrain independently within each range bin and identifies which technology yields the lowest LCOD under varying electricity, hydrogen, and diesel price scenarios. This approach helps determine under which market conditions a specific technology becomes the most cost-effective. It can support early-stage assessments of emerging technologies or inform technology developers and policymakers on comparative performance under different market environments.

- ▪

- Fleet-Level Cost Analysis: This analysis simulates how a fleet operator might select a single powertrain to serve all tours within a given range bin. By aggregating LCOD across all tours in each bin, this approach identifies the lowest-cost technology at the system level, offering a practical view for strategic fleet planning. This system-level analysis is especially valuable for fleet managers and decision-makers, offering a practical view of which powertrain minimizes costs at scales across typical daily operations. It enables fleet owners to identify the most economically viable technology for each segment of their business and to plan targeted transitions to lower-cost, lower-emission powertrains.

These two cost analysis approaches, one focused on individual vehicle performance and the other on fleet-level optimization, are designed to inform different stakeholder needs. The tour classification and evaluation framework provides a realistic basis for the comparison of emerging powertrains in terms of economic viability.

In the technology-level analysis, hydrogen price is held constant at USD 4/kg to simplify comparisons across powertrains and isolate electricity price sensitivity. In contrast, the fleet-level analysis varies hydrogen price between USD 3–11/kg to reflect uncertainty in future hydrogen production, delivery, and regional availability. This structure keeps the technology-level results interpretable while ensuring the fleet-level maps span a realistic range of future market conditions.

Electricity prices used in the sensitivity analysis represent the all-in delivered energy costs. While demand charges and time-of-use structures are not modeled explicitly, the wide electricity price range evaluated in this study spans values typical of both off-peak depot charging and higher-cost peak or demand charge conditions, thereby implicitly capturing the operational variability associated with commercial charging.

The results of these analyses are presented in the following section and provide detailed insights into how powertrain competitiveness evolves across timeframes, fuel price scenarios, and operational patterns. While stochastic uncertainty quantification (e.g., Monte Carlo) is not implemented, uncertainty is addressed structurally through broad fuel price sensitivity ranges that span plausible 2035–2050 market conditions in Section 3.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Energy Consumption Impact

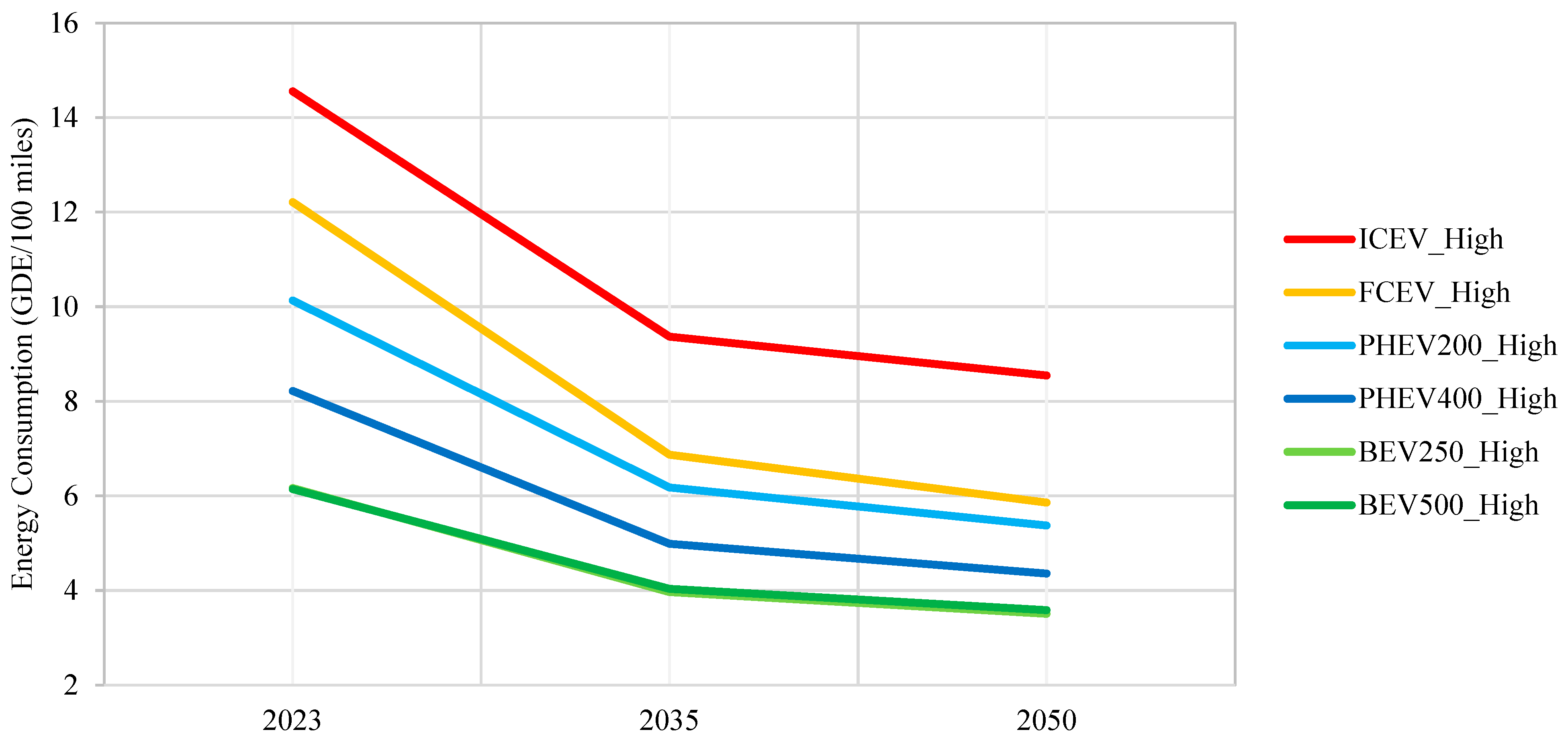

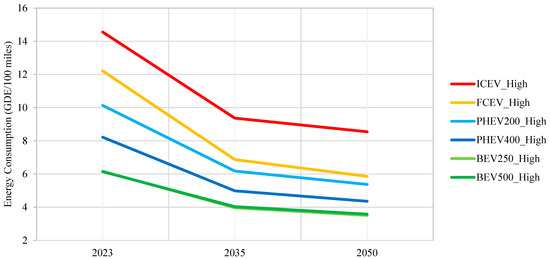

The results in this section illustrate the projected evolution of Class 8 truck powertrain energy consumption, VMT-weighted across all tours, spanning the years 2023, 2035, and 2050. The alternative powertrains, illustrated in Figure 6, show significant reductions in energy consumption despite notable improvements in the ICEV powertrains over the years, signifying the benefits of switching. These results were obtained from simulations of 2023, 2035, and 2050 model year trucks using the workflow described in the Section 2, with each truck simulated to operate over the collected 12-month period in California. Figure 6 provides a summary of energy consumption for the different Class 8 truck powertrain technologies and progress scenarios that were examined during their various tours. Energy consumption is obtained from simulating all the trucks over the 12-month period in Autonomie.

Figure 6.

Consumption projections for the period up to 2050.

In 2023, even with the current technology, alternative powertrains demonstrate a substantial advantage over traditional ICEVs in reducing energy consumption. PHEV200 reduces energy consumption by 30.4% compared to ICEVs, demonstrating the effectiveness of hybrid technology. PHEV400 and BEV500 achieve even greater reductions in energy use by 43.5%, highlighting the potential of higher-capacity hybrids and fully electric trucks. FCEVs, while not as efficient as BEVs, outperform ICEVs, indicating that hydrogen-powered trucks offer a promising pathway toward decarbonization. These results illustrate that even the early-stage adoption of advanced powertrains can provide meaningful environmental benefits, encouraging fleet operators to begin adopting hybrids and electric vehicles.

By 2035, improvements in powertrain technologies will lead to further reductions in energy consumption. PHEV200, PHEV400, and BEV reduce consumption by 34%, 47%, and 57%, respectively, compared to their ICEV counterparts for the same year. FCEVs continue to improve as hydrogen technologies advance, offering a more competitive consumption performance. By 2050, the results show substantial declines in energy consumption, signaling the maturation of advanced powertrain technologies. PHEV400 and BEV250 reduce energy consumption by nearly 50% compared to ICEVs, demonstrating the significant efficiency gains in hybrid and electric propulsion systems. BEV500 achieves a 58% reduction in consumption, reflecting advancements in battery energy density and electric drivetrain technologies. FCEVs continue to show steady improvements, reinforcing the potential of hydrogen as part of a diverse, low-carbon fleet strategy. These results confirm that, as technologies mature, alternative powertrains can consistently outperform ICEVs, making them increasingly viable replacements over time.

The results in this section show that alternative powertrains, especially BEVs and FCEVs, offer substantial reductions in energy consumption from 2023 to 2050. However, the success of these technologies hinges on the ability to evaluate costs alongside performance, ensuring that adoption remains both environmentally and economically sustainable. As fuel prices fluctuate and new technologies emerge, careful cost analysis will be crucial to guide effective decision-making for fleet electrification and powertrain selection. This is further explored in Section 3.2, which evaluates LCOD to provide actionable insights for effective fleet management and powertrain selection.

3.2. Cost Impact

In this section, we delve into the cost implications of truck operations by presenting a comprehensive analysis of the levelized cost of driving for trucks. As outlined in Section 2.4, further details and results of the sensitivity analyses for both the tour level and fleet level are detailed in this section. It is important to note that not all powertrains are considered across all range bins:

- ▪

- 0–250 miles: BEV500 and PHEV400 are excluded, as BEV250 and PHEV250 are sufficient for this range.

- ▪

- 250–500 miles: BEV250 is excluded, since operations are assumed to occur on a single charge.

- ▪

- 500+ miles: No BEVs are included due to range constraints under the single-charge assumption. This limitation will be revisited in future research.

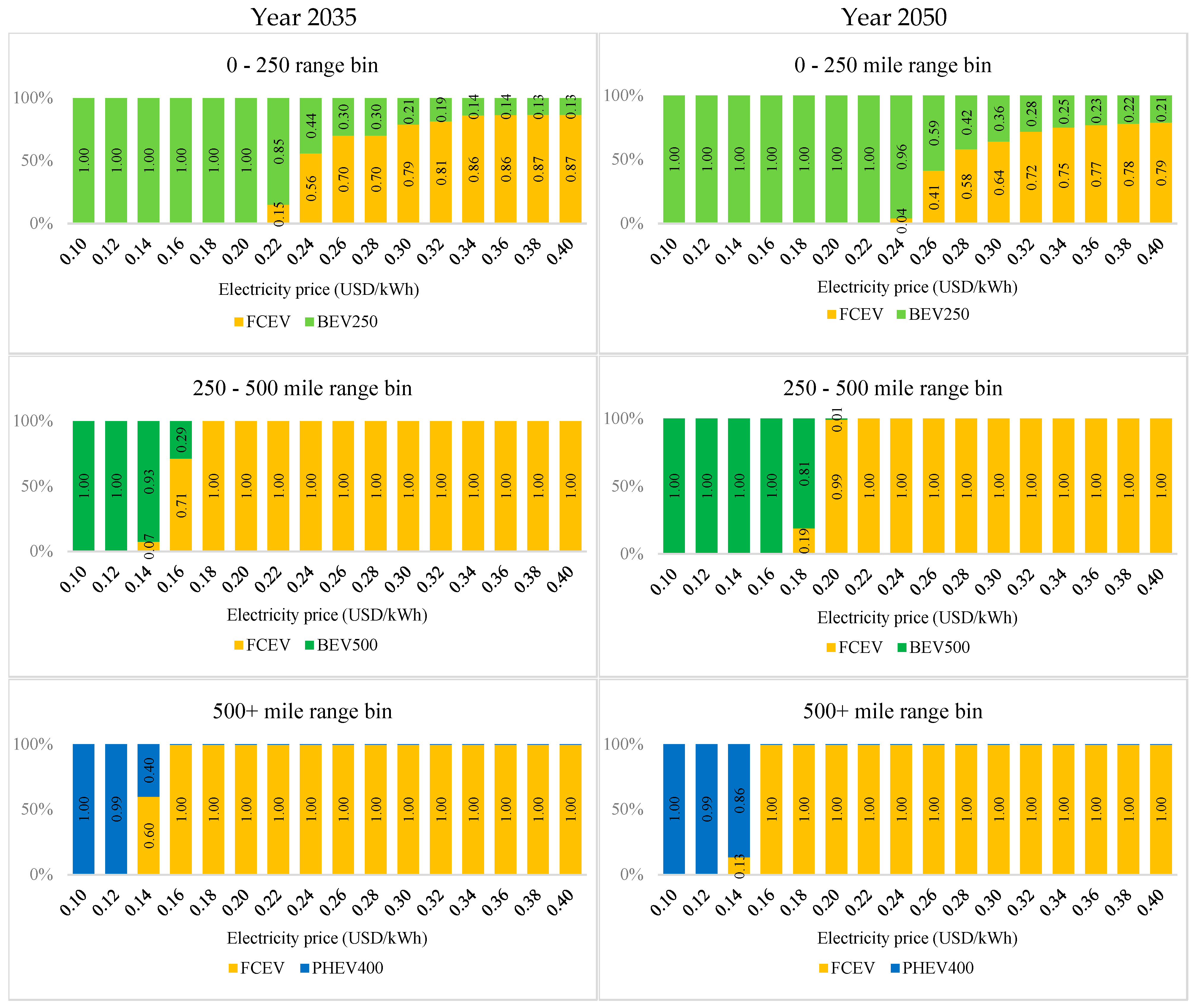

3.2.1. Technology-Level Cost Analysis

In this analysis, each powertrain is simulated across all applicable tours within a given range bin, over a 12-year vehicle lifetime, to calculate the LCOD under varying fuel price scenarios. For each tour, the powertrain yielding the lowest LCOD is recorded, and the aggregated results are used to determine the market share of each powertrain under different electricity price levels. This approach identifies which powertrains are best suited for each range bin and under what energy price conditions they become cost-optimal. The fuel price scenarios considered include the following:

- ▪

- Electricity prices: USD 0.10–0.50/kWh;

- ▪

- Hydrogen price: USD 4/kg (fixed);

- ▪

- Diesel prices (from [21]):

- -

- Reference case: USD 3.21/gal in 2035, USD 3.43/gal in 2050;

- -

- High-cost case: USD 5.325/gal in 2035, USD 5.73/gal in 2050.

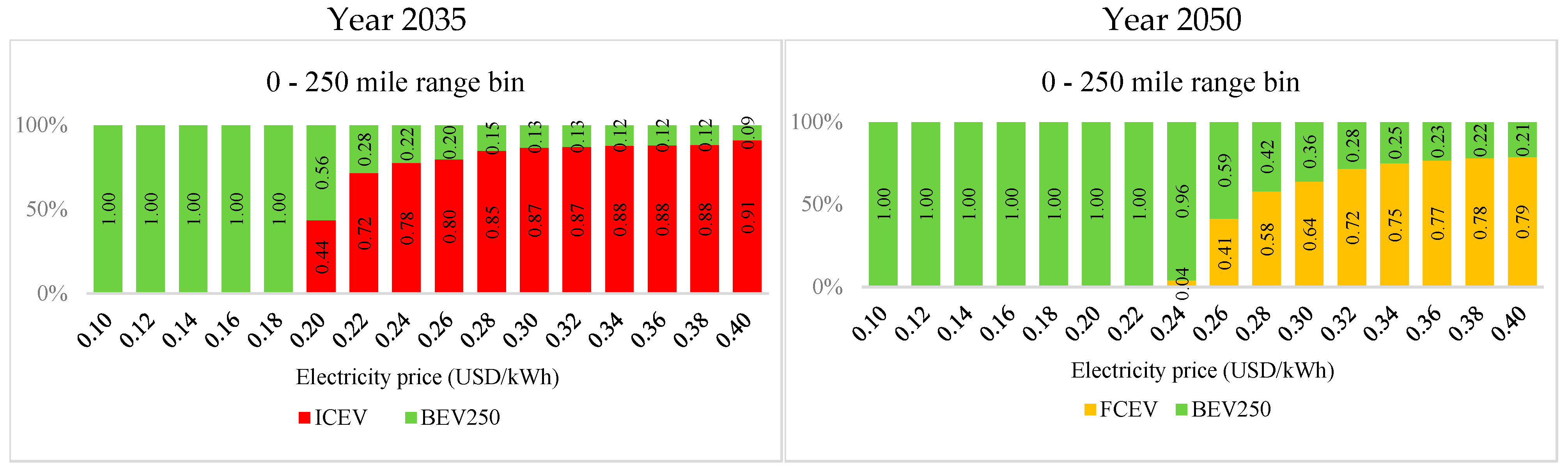

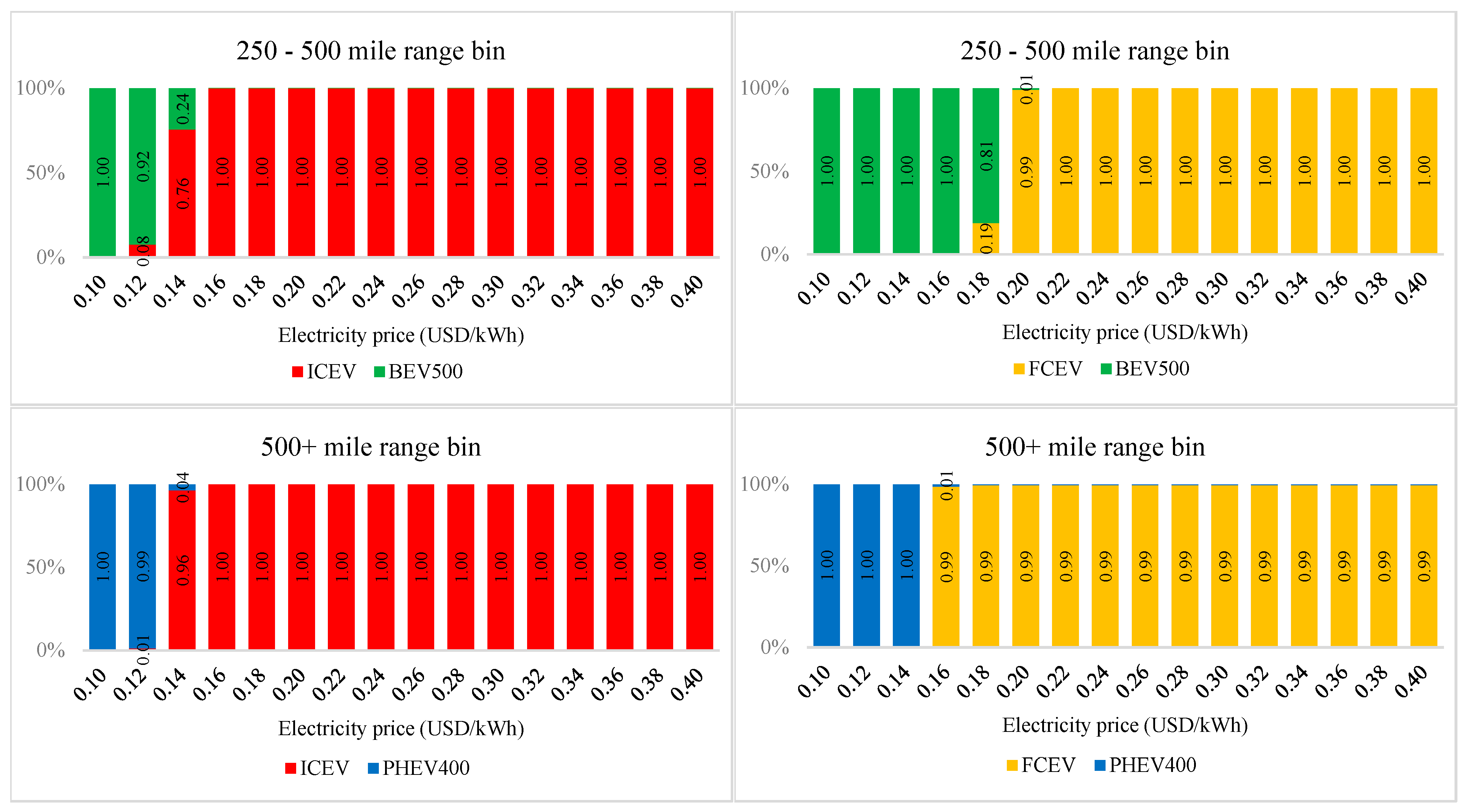

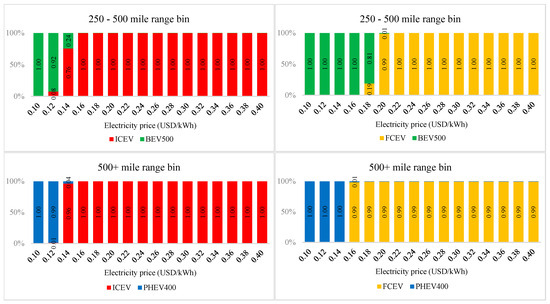

Figure 7 and Figure 8 summarize the share of each powertrain that achieves the lowest LCOD across the electricity price range, for both reference and high-diesel-price scenarios, within each range bin.

Figure 7.

Share of each powertrain across electricity prices under a diesel cost of USD 3.21/gal in 2035 and USD 3.43/gal in 2050.

Figure 8.

Share of each powertrain across electricity prices under a diesel cost of USD 5.325/gal in 2035 and USD 5.73/gal in 2050.

- (a)

- Reference-Diesel-Cost Scenario

Electricity price is a critical driver of powertrain competitiveness. At the 2035 reference diesel cost of USD 3.21/gal, in the 0–250-mile range, BEV250 completes all tours at the lowest LCOD when electricity prices are below USD 0.20/kWh, as illustrated in Figure 7. However, as electricity prices increase beyond this threshold, BEV250’s cost advantage diminishes, and ICEVs rapidly gain market share, capturing 91% of tours at USD 0.40/kWh. This indicates BEV250’s strong early-market potential, provided depot charging prices remain low, but also underscores its vulnerability under high-cost charging scenarios. In the 250–500-mile range, BEV500 remains cost-competitive only below USD 0.14/kWh. As electricity prices exceed this value, ICEVs become more favorable, reflecting BEV500’s relatively high capital costs and increased energy use over longer distances. For 500+-mile tours, PHEV400 achieves the lowest LCOD only when electricity prices are below USD 0.12/kWh. As prices rise, its dual energy cost (electricity + diesel) and higher capital expenses limit its cost-effectiveness, allowing ICEVs to dominate. FCEVs do not appear cost-competitive in 2035 under any electricity price scenario due to high manufacturing and operating costs.

By 2050, at the projected diesel cost of USD 3.43/gal, the cost-effectiveness of advanced powertrains improves notably. In the 0–250-mile range, BEV250 maintains competitiveness up to USD 0.26/kWh, with FCEVs capturing 79% of tours at USD 0.40/kWh. This shift is enabled by anticipated reductions in fuel cell costs and improved drivetrain efficiency. In the 250–500-mile range, BEV500 remains viable up to USD 0.18/kWh, after which FCEVs become the lowest-cost option, outperforming both ICEVs and BEVs. Similarly, for tours exceeding 500 miles, PHEV400 remains feasible only below USD 0.14/kWh. Beyond this point, FCEVs dominate, reflecting lower hydrogen costs and reduced fuel cell vehicle prices. These trends are supported by the projected vehicle price evolution, as, by 2050, the FCEV MSRP drops by 4.93% to USD 182,213, while ICEV prices rise by 3.92% to USD 185,327. As a result, FCEVs and BEVs both improve in relative cost-competitiveness, whereas PHEVs continue to show limited value in high-electricity-price scenarios due to their dual fuel dependency and cost structure.

- (b)

- High-diesel-cost scenario

By 2030, at a diesel cost of USD 5.325/gal, the cost landscape shifts significantly, strengthening the competitiveness of advanced powertrains. In the 0–250-mile range, BEV250 dominates all tours at electricity prices up to USD 0.20/kWh, as illustrated in Figure 8. Above USD 0.22/kWh, FCEVs begin to outperform both BEVs and ICEVs, capturing an increasing share of tour completions at elevated electricity prices. The higher diesel cost effectively reduces the economic attractiveness of ICEVs in this segment. In the 250–500-mile range, BEV500 retains cost competitiveness up to USD 0.14/kWh. However, at prices above this threshold, FCEVs emerge as the lowest LCOD option, reflecting their ability to displace ICEVs more effectively under higher-diesel-price assumptions. For tours exceeding 500 miles, PHEV400 remains viable at electricity prices below USD 0.14/kWh, beyond which FCEVs take over as the most cost-effective powertrain. The elevated diesel cost diminishes the relative competitiveness of ICEVs across all bins, particularly in the longer-range segment.

Compared to the reference-diesel-cost scenario, the most notable shift in 2035 is the early entry of FCEVs as a viable alternative, particularly in mid- and long-range applications. Although their capital costs remain high, the burden placed on diesel-powered trucks by increased fuel prices makes FCEVs economically feasible at lower electricity prices than in the reference scenario.

By 2050, with diesel projected at USD 5.73/gal, the advantage of advanced powertrains becomes even more pronounced. In the 0–250-mile range, BEV250 remains competitive up to USD 0.26/kWh, with FCEVs taking over at higher electricity prices. Compared to 2035, this represents a 20% increase in BEV250’s electricity price tolerance, supported by expected reductions in battery and vehicle costs. In the 250–500-mile range, BEV500 maintains competitiveness up to USD 0.18/kWh, while FCEVs capture the remainder of tours at higher electricity prices, overtaking both BEVs and ICEVs. This mirrors the evolution observed in the reference scenario, but with a more decisive decline in ICEV viability due to rising diesel costs. For tours longer than 500 miles, PHEV400 is viable below USD 0.14/kWh, but FCEVs dominate the cost landscape beyond this point. The higher diesel prices exacerbate the cost burden on ICEVs and hybrid vehicles alike, making FCEVs the clear lowest-cost option across most electricity price points in this bin.

Taken together, the 2050 high-diesel-cost scenario accelerates the transition toward zero-emission powertrains, especially for longer-distance freight operations. ICEVs lose competitiveness across all segments, while FCEVs emerge as the most robust option in scenarios with high electricity prices. Meanwhile, BEVs retain their dominance in short- and mid-range operations where electricity prices remain favorable.

Although PHEVs gain modest cost benefits from the elevated diesel prices, their dual-fuel reliance continues to expose them to high energy cost volatility. As electricity prices increase, the operational reliance on diesel becomes more burdensome, limiting their feasibility, particularly for longer tours that exceed battery-only range.

These findings reinforce the conclusion that high diesel prices substantially shift the economic balance toward BEVs and FCEVs, with the latter proving particularly resilient in mid- and long-haul applications. They also highlight the importance of ongoing investments in charging and hydrogen infrastructure to enable the large-scale deployment of these advanced powertrains.

However, it is important to note that this analysis assumes a fixed hydrogen price of USD 4/kg. The cost-competitiveness of FCEVs in both 2035 and 2050 is highly sensitive to this assumption. If hydrogen prices were to increase to USD 6/kg, ICEVs would retain a significant cost advantage over FCEVs in 2035, particularly in the mid- and long-range bins. Therefore, the economic viability of FCEVs in the near term is conditional on achieving sustained low hydrogen production and distribution costs.

While these tour-level results offer critical insights into the conditions under which each powertrain becomes cost-optimal, fleet-wide decisions must also account for operational simplicity, infrastructure availability, and vehicle deployment strategies. To support such strategic planning, we extend the analysis in the following section using a fleet-level approach.

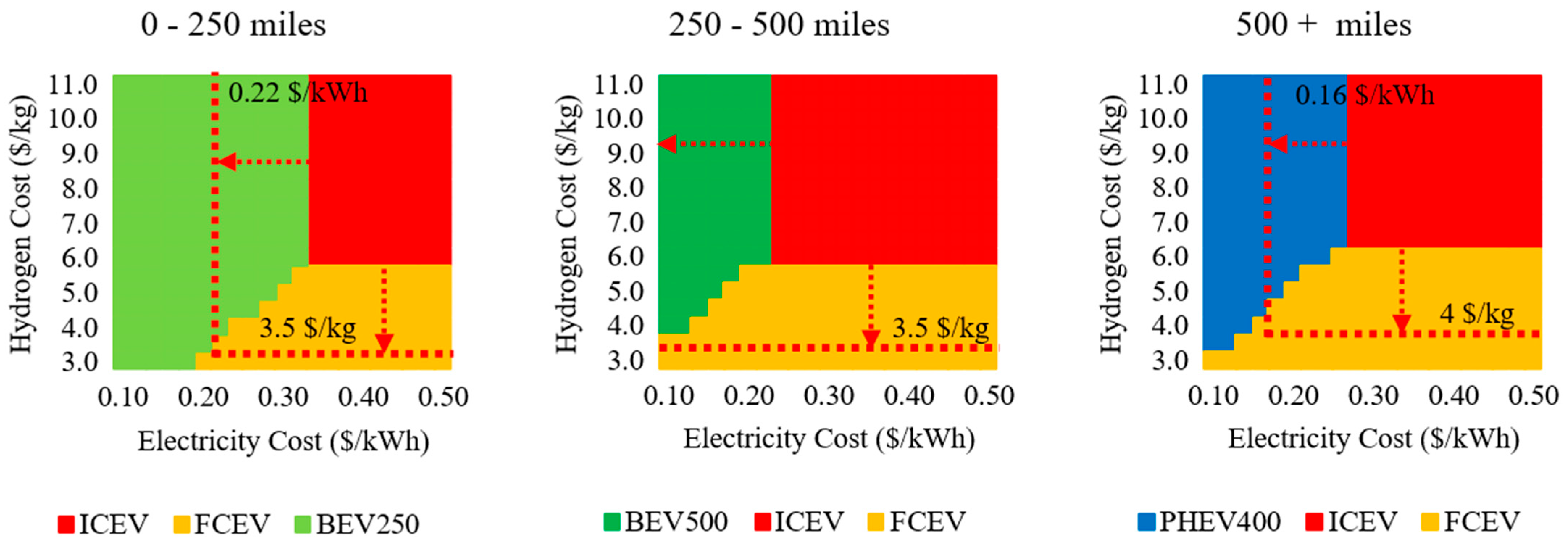

3.2.2. Fleet-Level Cost Analysis

While the tour-level analysis in Section 3.2.1 identifies the lowest-cost powertrain for each individual trip, fleet operators typically make decisions at the system level. They seek to deploy a single dominant powertrain within each operational segment (e.g., short-, medium-, or long-range tours) to simplify logistics, minimize capital investment complexity, and ensure consistent infrastructure planning. To reflect this reality, we perform a fleet-level cost analysis that identifies the powertrain with the lowest aggregate LCOD across all tours within each range bin, under varying fuel price conditions.

For each year evaluated (2035 and 2050), LCOD is calculated for all powertrains across a matrix of electricity, hydrogen, and diesel price combinations. The total energy and vehicle costs for each powertrain are aggregated across all tours within a given range bin and normalized by the total miles traveled. The powertrain with the lowest aggregate LCOD is identified as the fleet-level optimal solution for that segment. Fuel price assumptions vary as follows:

- ▪

- Electricity prices: USD 0.10–0.50/kWh;

- ▪

- Hydrogen prices: USD 3–11/kg;

- ▪

- Diesel prices (from [21]):

- -

- Reference case: USD 3.21/gal in 2035, USD 3.43/gal in 2050;

- -

- High-cost case: USD 5.325/gal in 2035, USD 5.73/gal in 2050.

Given the difficulty of accurately projecting electricity and hydrogen prices in future years, we adopt a wide-ranging sensitivity analysis to explore powertrain cost outcomes under various energy price scenarios. Long-term electricity and hydrogen costs are shaped by factors such as infrastructure development, energy market regulation, fuel production scale, and geopolitical influences, factors not explicitly modeled in this analysis. By varying these fuel prices across broad but plausible ranges, the analysis provides decision-relevant insights for a wide range of 2035 and 2050 energy cost conditions, without relying on a single-point forecast.

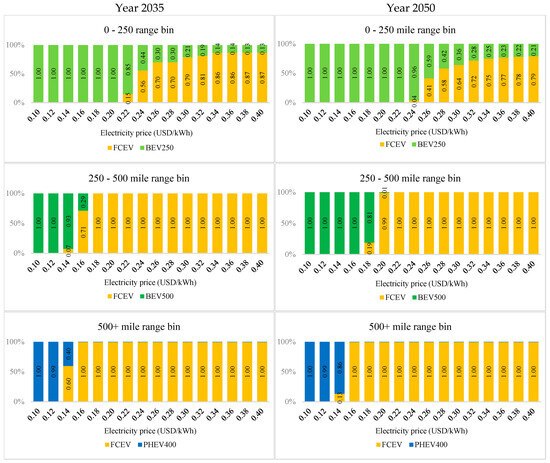

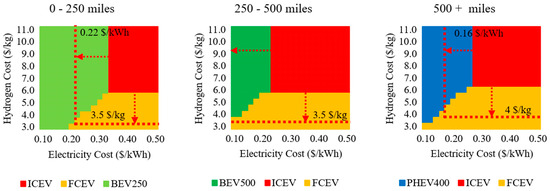

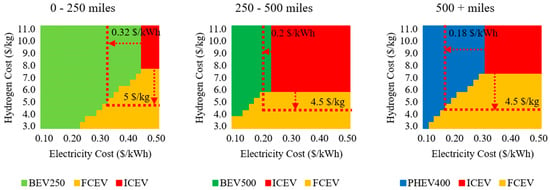

The results are visualized in heat maps (Figure 9 and Figure 10) for the high-diesel-cost scenario. Each heat map shows which powertrain achieves the lowest fleet-wide LCOD at each electricity/hydrogen price combination. A dashed line denotes the competitiveness threshold of ICEVs under reference diesel prices.

Figure 9.

Powertrains with the lowest LCOD in 2035 across electricity and hydrogen price combinations, assuming USD 5.325/gal diesel (ICEV threshold at USD 3.21/gal shown by dashed line).

Figure 10.

Powertrains having the lowest LCOD in 2050 across electricity and hydrogen cost scenarios, with diesel cost at USD 5.73/gal (reference diesel cost at USD 3.43/gal for the dashed lines).

- (a)

- 2035 Results

- 0–250-Mile Range Bin

Under the reference diesel price of USD 3.21/gal, ICEVs dominate across most electricity and hydrogen price combinations in the 0–250-mile range. BEV250 becomes cost-effective only when electricity prices fall below approximately USD 0.20/kWh, reflecting the importance of low charging costs. FCEVs are not cost-competitive under these diesel conditions except in narrow cases where hydrogen drops below USD 3/kg, below even the lowest projected price ranges from current hydrogen roadmaps.

Under the high diesel price of USD 5.325/gal, the dynamics change significantly. BEV250 becomes the dominant fleet-level option up to USD 0.34/kWh electricity, demonstrating its strong cost performance under low-to-moderate electricity prices. FCEVs become viable when hydrogen costs fall below USD 6/kg, particularly when electricity is expensive. ICEVs lose their fleet-level advantage, except in cases where both electricity and hydrogen costs are high, reaffirming their diminishing role under higher fuel costs.

- 250–500-Mile Range Bin

In the 250–500-mile range bin, no single powertrain dominates across all energy price combinations. Under reference diesel prices, ICEVs remain the most cost-effective option for most scenarios. FCEVs only become competitive when hydrogen prices fall below USD 3.5/kg, while BEV500 is not cost-competitive under any scenario due to its high capital cost. Under the high-diesel-price scenario (USD 5.325/gal), the dynamics shift. BEV500 becomes cost-effective when electricity prices are below approximately USD 0.24/kWh and hydrogen is relatively expensive (above USD 6/kg). In contrast, FCEVs outperform when hydrogen costs drop below USD 6/kg, particularly in conditions with higher electricity prices. This creates a zone of competitive overlap between the two technologies.

The fleet-level results suggest that BEV500 is best suited when fleets have access to stable, low-cost depot charging and can match routes to its battery range. Meanwhile, FCEVs offer better operational consistency across a diverse set of tours, particularly when infrastructure constraints or electricity prices undermine BEV deployment. Neither powertrain dominates across the full price space, and selection will depend on energy cost trajectories, route regularity, and infrastructure readiness.

- 500+-Mile Range Bin

For the longest-range bin, BEVs are excluded due to their inability to complete these tours without en-route charging, which is not assumed in this study. Only PHEV400, FCEVs, and ICEVs are evaluated.

At the reference diesel price, ICEVs remain dominant across most of the fuel price space. PHEV400 is cost-effective only when electricity is below USD 0.15/kWh, and FCEVs become viable only when hydrogen prices are below USD 4/kg. These thresholds fall near or below current cost targets and would require substantial market shifts to be realized.

Under high diesel prices, both PHEV400 and FCEVs gain substantial ground. PHEV400 is competitive when electricity remains below USD 0.28/kWh, while FCEVs dominate when hydrogen falls below USD 6.5/kg. At even higher hydrogen prices, PHEVs reclaim the advantage, particularly when electricity remains affordable. ICEVs only maintain cost advantage in extreme price scenarios, reinforcing their vulnerability to rising fuel costs in the long-haul segment.

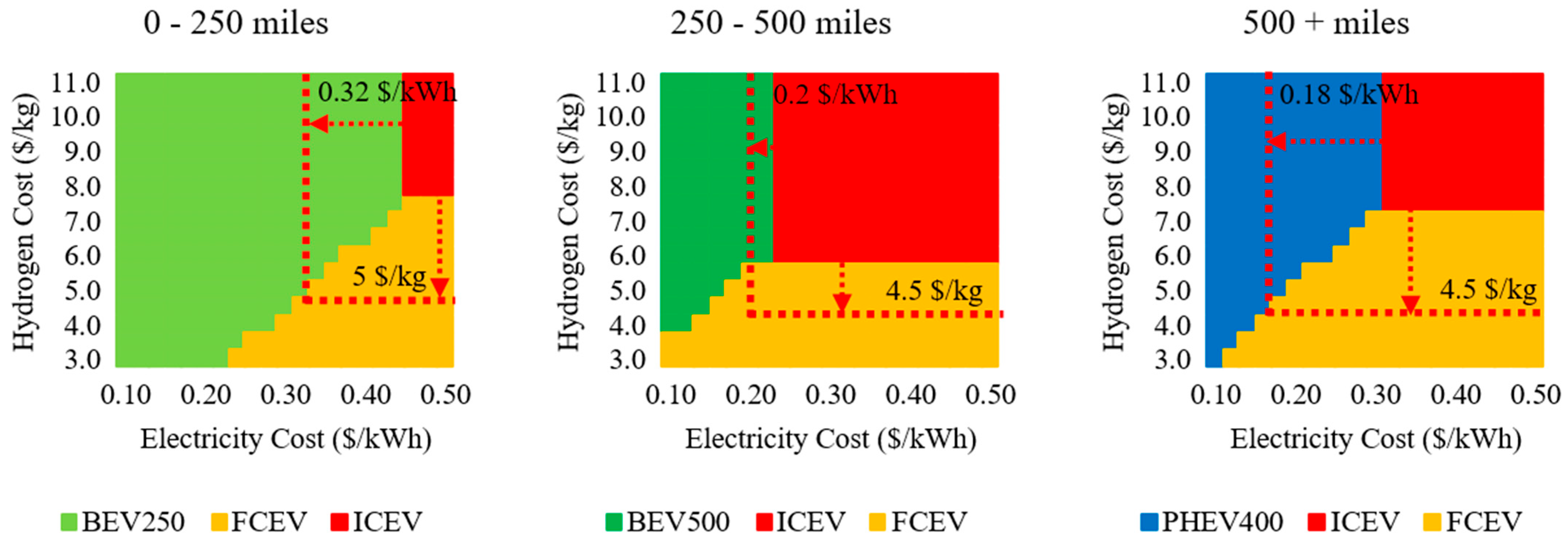

- (b)

- 2050 Results

- 0–250-Mile Range Bin

By 2050, with improved BEV cost and efficiency and a higher diesel price of USD 5.73/gal, BEV250 extends its dominance across nearly the entire electricity–hydrogen cost map. It remains cost-effective up to USD 0.46/kWh, with FCEVs only overtaking in narrow scenarios when electricity prices are extremely high and hydrogen falls below USD 8/kg. Under the reference diesel price of USD 3.43/gal, BEV250 is viable up to USD 0.32/kWh, reflecting its improved cost profile compared to 2035.

- 250–500-Mile Range Bin

By 2050, improvements in vehicle and battery cost reduce BEV500’s LCOD and expand its competitive viability. Under reference diesel prices, FCEVs become cost-effective at hydrogen prices below ~USD 5/kg, while BEV500 becomes viable when electricity is below USD 0.26/kWh. Under high diesel costs (USD 5.73/gal), both BEV500 and FCEVs become strong contenders, with BEV500 competitive up to USD 0.35/kWh electricity and FCEVs viable up to USD 7/kg hydrogen.

This reflects a growing balance between the two technologies. BEV500 benefits from declining battery costs and improved drivetrain efficiency, while FCEVs gain from anticipated reductions in fuel cell and hydrogen system costs. The choice between them becomes increasingly scenario-specific: BEV500 offers a lower cost in stable depot charging conditions, while FCEVs provide resilience under high electricity prices and operational variability.

Overall, the 250–500-mile segment in 2050 represents a highly dynamic competitive space. Rather than a clear-cut winner, BEVs and FCEVs each offer advantages under different infrastructure and energy price regimes. Fleet-level deployment decisions will require nuanced consideration of route consistency, energy supply, and capital budgeting.

- 500+-Mile Range Bin

In 2050, PHEV400 and FCEVs remain the primary alternatives. At reference diesel prices, PHEV400 is cost-effective up to USD 0.18/kWh, while FCEVs are viable below USD 4.5/kg. Under high diesel prices, PHEV400 remains competitive up to USD 0.32/kWh, and FCEVs extend viability to hydrogen prices up to USD 7.5/kg. Compared to 2035, both technologies gain cost resilience, but FCEVs hold a broader competitive window, especially if hydrogen prices fall due to policy support or the scale-up of renewable hydrogen supplies.

These fleet-level results reinforce and deepen the tour-level findings, offering a clear view of how diesel price escalation drives the transition away from conventional ICEVs, particularly in the mid- and long-range segments. BEV250 consistently demonstrates a strong cost performance under both reference and high-diesel-price scenarios, provided electricity prices remain below USD 0.22/kWh (in 2035) and USD 0.32/kWh (in 2050) when diesel is priced around USD 3.3/gal, and below USD 0.34/kWh (in 2035) and USD 0.46/kWh (in 2050) when diesel exceeds USD 5/gal. This cost competitiveness underscores the importance of widespread access to low-cost depot charging, which NREL estimates at approximately USD 0.17/kWh, a level sufficient to support the majority of daily operations for U.S. regional-haul trucks [22]. In contrast, a reliance on fast en-route charging, typically exceeding USD 0.38/kWh [22], significantly reduces the cost-effectiveness of BEVs, particularly for longer trips, and limits their viability outside of depot-based duty cycles.

In the 250–500-mile range, both BEV500 and FCEVs emerge as viable solutions by 2050, but their competitiveness is strongly dependent on fuel price conditions and operational contexts. BEV500 becomes cost-effective when electricity is reliably inexpensive, especially with depot charging, while FCEVs maintain stronger performance under high electricity prices or operational uncertainty. Fleet-level results show no clear dominance; rather, this segment reflects a competitive balance between technologies, each with distinct trade-offs. BEV500 benefits from improvements in battery cost and drivetrain efficiency but still faces capital cost constraints. FCEVs offer a broader range and consistent LCOD across diverse tours, provided hydrogen prices remain below USD 6/kg. Fleet operators will likely base decisions in this segment on infrastructure availability, fuel contracts, and route regularity.

For long-distance operations, PHEVs offer limited cost competitiveness and function mainly as transitional technologies. They are only viable when both electricity is low and hydrogen remains expensive, and, even then, their dual-fuel reliance exposes them to compounding energy price risks. Their viability erodes further in 2050, as FCEV costs improve and diesel prices increase.

Across all scenarios, ICEVs retain a competitive position only in narrow corners of the fuel price space, specifically where both electricity and hydrogen prices are high and diesel remains cheap. As energy markets shift and emissions regulations tighten, this window of economic viability will likely continue to shrink.

Ultimately, this fleet-level analysis confirms that BEVs and FCEVs are emerging as the most economically viable technologies for clean and affordable freight, provided that electricity and hydrogen prices fall within feasible bounds. Their future adoption will depend not only on cost declines, but also on policy coordination and infrastructure development. Fleet managers must align deployment strategies with operational segmentation and regional energy access. Policymakers, in turn, can focus on enabling both low-cost depot charging and hydrogen refueling corridors, particularly for long-haul segments. The future of cost-effective freight will rely not just on advanced vehicle technology, but on smart energy ecosystem planning across multiple fuels and modes.

4. Summary and Conclusions

This study presents a dual-perspective evaluation of advanced truck powertrains, BEVs, FCEVs, PHEVs, and ICEVs, using both technology-level and fleet-level cost analyses. By leveraging real-world tour data, high-fidelity modeling tools, and a wide range of fuel price scenarios, the research identifies when and under what conditions these technologies become cost-effective and environmentally viable without compromising freight reliability.

A key strength of this work lies in the integration of two complementary analytical lenses. The technology-level analysis isolates the performance of each powertrain across individual tours, offering detailed insights into how energy prices influence cost-effectiveness at the vehicle level. The fleet-level analysis aggregates costs across entire tour sets, reflecting how real-world operators must often choose a single powertrain per operational segment to ensure logistical simplicity and cost efficiency.

The two perspectives converge on several key findings. Both analyses confirm that diesel price escalation is a critical trigger for shifting cost-competitiveness toward zero-emission vehicles, especially in mid- and long-range applications. BEV250 demonstrates strong cost performance across all scenarios, assuming electricity prices remain below USD 0.22/kWh–0.34/kWh in 2035 and USD 0.32/kWh–0.46/kWh in 2050, depending on diesel price conditions. This reinforces the importance of widespread access to low-cost depot charging, which supports the majority of regional-haul operations. In contrast, a reliance on fast en-route charging, typically priced above USD 0.38/kWh, significantly reduces BEV cost-effectiveness and limits deployment outside depot-based duty cycles.

In the 250–500-mile segment, neither technology is dominant. The tour-level analysis shows that BEV500 achieves the lowest LCOD on many trips, particularly under low and stable electricity prices, making it a viable option for fleets with consistent mid-range routes and dependable depot charging access. At the fleet level, FCEVs offer a more stable performance across all tours, particularly when electricity prices are high or route variability increases. This segment reflects a competitive overlap, with both technologies offering deployment opportunities depending on energy price conditions, infrastructure availability, and operational strategy. BEVs may capture a meaningful portion of this market, especially if capital costs decline and depot-based charging remains widespread.

For long-haul operations (>500 miles), FCEVs are the most cost-effective non-diesel option by 2050, assuming hydrogen prices remain below USD 6/kg. PHEVs show limited viability, primarily in transitional roles or under narrow fuel price conditions. While PHEVs can reduce cost in some tours, their dual-fuel dependence increases the sensitivity to fuel price volatility, limiting long-term competitiveness at scale.

A key contribution of this work is the demonstration of how technology-level competitiveness does not always scale to fleet-level viability. Some powertrains, such as BEVs, can outperform diesel on specific routes under favorable electricity prices, yet may fall short at the fleet level if they lack consistency across all operational demands. Conversely, FCEVs and ICEVs may not always be lowest-cost on individual trips, but their flexibility and robustness can make them more attractive from a system-wide cost perspective, especially in variable or long-haul operations.

This finding has practical implications. Fleet operators evaluating powertrain transitions must consider not just energy prices or vehicle specs, but also route diversity, charging/refueling access, and the logistics of standardizing powertrain types across segments. The analysis highlights that electrification will require targeted deployment, favoring BEVs where depot charging and route regularity exist, and FCEVs where range flexibility and resilience to fuel price volatility are more critical.

For policymakers, the results emphasize the importance of infrastructure coordination with operational needs. Depot charging investments are essential for unlocking BEV cost advantages. Similarly, hydrogen availability in key freight corridors may be pivotal to realizing FCEV viability. Fuel price signals alone are insufficient if not paired with network readiness.

From a research perspective, this study opens pathways for future work on (1) the route-level optimization of mixed powertrain fleets, (2) the integration of dynamic energy pricing and infrastructure access constraints, and (3) total cost of ownership frameworks that include downtime, maintenance, or asset utilization risk. Importantly, this analysis assumes that all electric trucks operate on a single charge per tour, without modeling en-route recharging or its impact on operations and downtime. While this simplifies the comparative assessment, future work should account for charging infrastructure availability, dwell time, and scheduling constraints, especially for long-range BEV applications.

In addition, the analysis adopts vehicle MSRPs derived from the modeling framework, with battery pack costs assumed at USD 105/kWh in 2035 and USD 62.5/kWh in 2050. While these reflect expected market trends, further reductions in battery costs could lower BEV capital costs more rapidly than assumed here, potentially improving their competitiveness, particularly in mid- and long-range segments. The simulations also assume nominal operating conditions and do not capture weather-related impacts such as cold temperatures, which influence vehicle energy consumption and range.

Ultimately, this work suggests that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Powertrain transitions must be range-aware, infrastructure-sensitive, and fleet-structured. The combination of tour-level and fleet-level insights presented here offers a template for stakeholders aiming to navigate the cost, technology, and operational complexity of decarbonizing heavy-duty trucking.

Although the analysis is based on freight activity in California, the methodological framework is generalizable to other regions. However, the specific cost-competitiveness thresholds may differ due to regional variations in electricity prices, hydrogen availability, terrain, climate, and regulatory environments. Applying this framework to other freight markets would help identify region-specific transition pathways.

This study has several limitations. First, BEV operations are modeled under a single-charge-per-tour assumption, without accounting for the impact of en-route charging on travel time or operational flexibility. Second, the analysis does not incorporate weather-dependent energy consumption effects or thermal management penalties. Finally, uncertainty is treated deterministically rather than through stochastic or probabilistic methods. Future research will incorporate dynamic charging availability, stochastic fleet behavior, mixed powertrain optimization, and interactions between freight electrification and grid capacity constraints to further strengthen system-level planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.; methodology, C.M.; software, S.P. and M.A.; validation, A.K., and J.B.G.; formal analysis, A.K. and J.B.G.; resources, H.B.; data curation, O.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.G. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, H.B., O.S., N.Z.-G., C.M. and V.F.; supervision, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This report and the work described were sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Vehicle Technologies Office (VTO) under the Pathways to Affordable, Convenient, and Efficient Regional Mobility, an initiative of the Energy Efficient Mobility Systems (EEMS) Program.

Data Availability Statement

Some of the datasets presented in this article are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions. Requests for access should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank Cummins Inc. for their technical support and guidance throughout the project. The submitted manuscript has been created by the UChicago Argonne, LLC, Operator of Argonne National Laboratory (Argonne). Argonne, a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science laboratory, is operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The U.S. Government retains for itself, and others acting on its behalf, a paid-up nonexclusive, irrevocable worldwide license in said article to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute copies to the public, and perform publicly and display publicly, by or on behalf of the Government.

Conflicts of Interest

Hoseinali Borhan is an employee of Cummins Inc. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- FHWA. Highway Statistics 2019. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/policyinformation/statistics/2019/vm1.cfm (accessed on 1 June 2022).

- Joshi, S.; Dahodwala, M.; Ahuja, N.; Dhanraj, F.N.; Koehler, E.; Franke, M.; Tomazic, D. Evaluation of Hybrid, Electric and Fuel Cell Powertrain Solutions for Class 6-7 Medium Heavy-Duty Vehicles. SAE Int. J. Adv. Curr. Prac. Mobility 2021, 3, 2955–2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayagopal, R.; Rousseau, A. Electric Truck Economic Feasibility Analysis. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Mansour, C.; Diab, J. System dynamics modeling for mitigating energy use and CO2 emissions of freight transport in Lebanon. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 26–28 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Sader, K.M.; Biswas, S.; Jones, R.; Mennig, M.; Rezaei, R.; Green, W.H. Battery electric long-haul trucking with overnight charging in the United States: A comprehensive costing and emissions analysis. Appl. Energy 2025, 384, 125443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, F.; Zhao, F.; Liu, M.; Liu, Z.; Hao, H.; Reiner, D.M. Assessing the viability of renewable hydrogen, ammonia, and methanol in decarbonizing heavy-duty trucks. Appl. Energy 2025, 383, 125293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Z.; Zhao, F.; Bai, F.; Liu, Z.; Hao, H. Evaluating fuel cell vs. battery electric trucks: Economic perspectives in alignment with China’s carbon neutrality target. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basma, H.; Rodríguez, F. A total cost of ownership comparison of truck decarbonization pathways in Europe. In Proceedings of the International Council on Clean Transportation, Washington, DC, USA, 13 November 2023; Working Paper 2023-28. Available online: https://theicct.org/publication/total-cost-ownership-trucks-europe-nov23/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Sun, R.; Sujan, V.A.; Jatana, G. Systemic decarbonization of road freight transport: A comprehensive total cost of ownership model. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustbader, J.; Selvam, P.; Bennion, K.; Payne, G.; Hunter, C.; Penev, M.; Brooker, A.; Baker, C.; Birky, A.; Zhang, C.; et al. Transportation Technology Total Cost of Ownership (T3CO); National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/transportation/t3co (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Anderson, O.; Hong, W.; Wang, B.; Yu, N. Impact of flexible and bidirectional charging in medium- and heavy-duty trucks on California’s decarbonization pathway. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Winkenbach, M. Technology and energy choices for fleet asset decarbonization under cost uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2025, 139, 104525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, J.; Hope, M.; Ley, H.; Sokolov, V.; Xu, B.; Zhang, K. POLARIS: Agent-based modeling framework development and implementation for integrated travel demand and network and operations simulations. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 64, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbowski, D.; Rousseau, A.; Smis-Michel, V.; Vermeulen, V. Trip Prediction Using GIS for Vehicle Energy Efficiency. In Proceedings of the ITS World Congress, Detroit, MI, USA, 7–11 September 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Moawad, A.; Kim, N.; Shidore, N.; Rousseau, A. Assessment of Vehicle Sizing, Energy Consumption and Cost Through Large Scale Simulation of Advanced Vehicle Technologies; ANL/ESD-15/28; Argonne National Lab. (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argonne National Laboratory. TechScape. Available online: https://vms.taps.anl.gov/tools/techscape/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- HERE Maps. Developer Guide—HERE Routing API. Available online: https://www.here.com/docs/bundle/routing-api-developer-guide-v8/page/README.html (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Mansour, C.; Sabri, E.I.; Vijayagopal, R.; Pagerit, S.; Rousseau, A. Assessing the Potential Consumption and Cost Benefits of Next-Generation Technologies for Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicles: A Vehicle-Level Perspective. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Vehicle Power and Propulsion, Milano, Italy, 23–27 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, E.S.; Nieto Prada, D.; Vijayagopal, R.; Mansour, C.; Phillips, P.; Kim, N.; Alchahir Alhajjar, M.; Rousseau, A. Detailed Simulation Study to Evaluate Future Transportation Decarbonization Potential; Argonne National Laboratory (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2023.

- Islam, E.; Vijayagopal, R.; Rousseau, A. A Comprehensive Simulation Study to Evaluate Future Vehicle Energy and Cost Reduction Potential; Report to the US Department of Energy Contract ANL/ESD-22/6; Argonne National Laboratory (ANL): Argonne, IL, USA, 2022.

- EIA. U.S. Energy Information Administration—EIA—Independent Statistics and Analysis. Available online: https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/aeo/data/browser/#/?id=3-AEO2023&cases=ref2023&sourcekey=0 (accessed on 13 July 2025).

- Bennett, J.; Mishra, P.; Miller, E.; Borlaug, B.; Meintz, A.; Birky, A. Estimating the Breakeven Cost of Delivered Electricity to Charge Class 8 Electric Tractors; National Renewable Energy Lab. (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).