Optimization of Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Lines for Fuel–Electric Vehicle Co-Production Under Workstation Sharing

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- How can the workstation sharing between EVs and FVs be balanced in a mixed-vehicle, multi-operator environment?

- (2)

- How can the genetic algorithm be improved to make it suitable for the constraints of shared workstations?

- (3)

- Compared with the traditional model without workstation sharing, what improvements can be achieved in terms of the number of workstations, human resource utilization, and workload balance?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution of Assembly Line Balancing Research

2.2. Multi-Manned and Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing

2.3. Theoretical Background

2.4. Recent Research Trends

3. Mathematical Model

3.1. Model Assumptions

- (1)

- The priority relationship constraints among tasks are known.

- (2)

- The same assembly work needs to be assigned to the same workstation.

- (3)

- The transportation time of the product between workstations is not considered.

- (4)

- The switching time between different model products is not considered.

- (5)

- One task can only be assigned to one workstation.

- (6)

- The standard time for completing the operation is scientifically determined and fixed.

- (7)

- The equipment is movable, and any operation can be assigned to any workstation.

- (8)

- The completion time of the operation does not change due to the assignment to a workstation.

- (9)

- Workers at all workstations possess identical skill levels and are capable of performing any assigned task.

- (10)

- The time required by different workers to complete the same task element is assumed to be identical.

- (11)

- The cumulative processing time of tasks allocated to an individual worker must not exceed the specified cycle time.

- (12)

- The maximum number of workers permitted at each workstation is predefined.

- (13)

- Each worker remains fixed at the assigned workstation during one production cycle.

- (14)

- Within a workstation, workers may move freely to support other operations if idle time occurs after completing their assigned tasks.

3.2. Notation Description

3.3. Objective Functions

3.4. Constraints

4. Algorithm Design

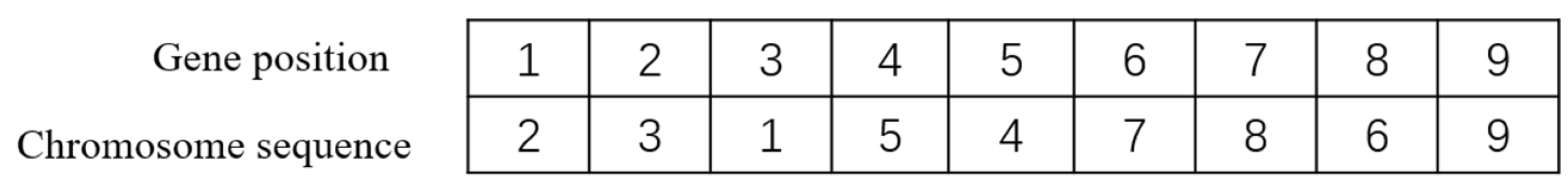

4.1. Encoding and Decoding Mechanism

4.1.1. Encoding Strategy

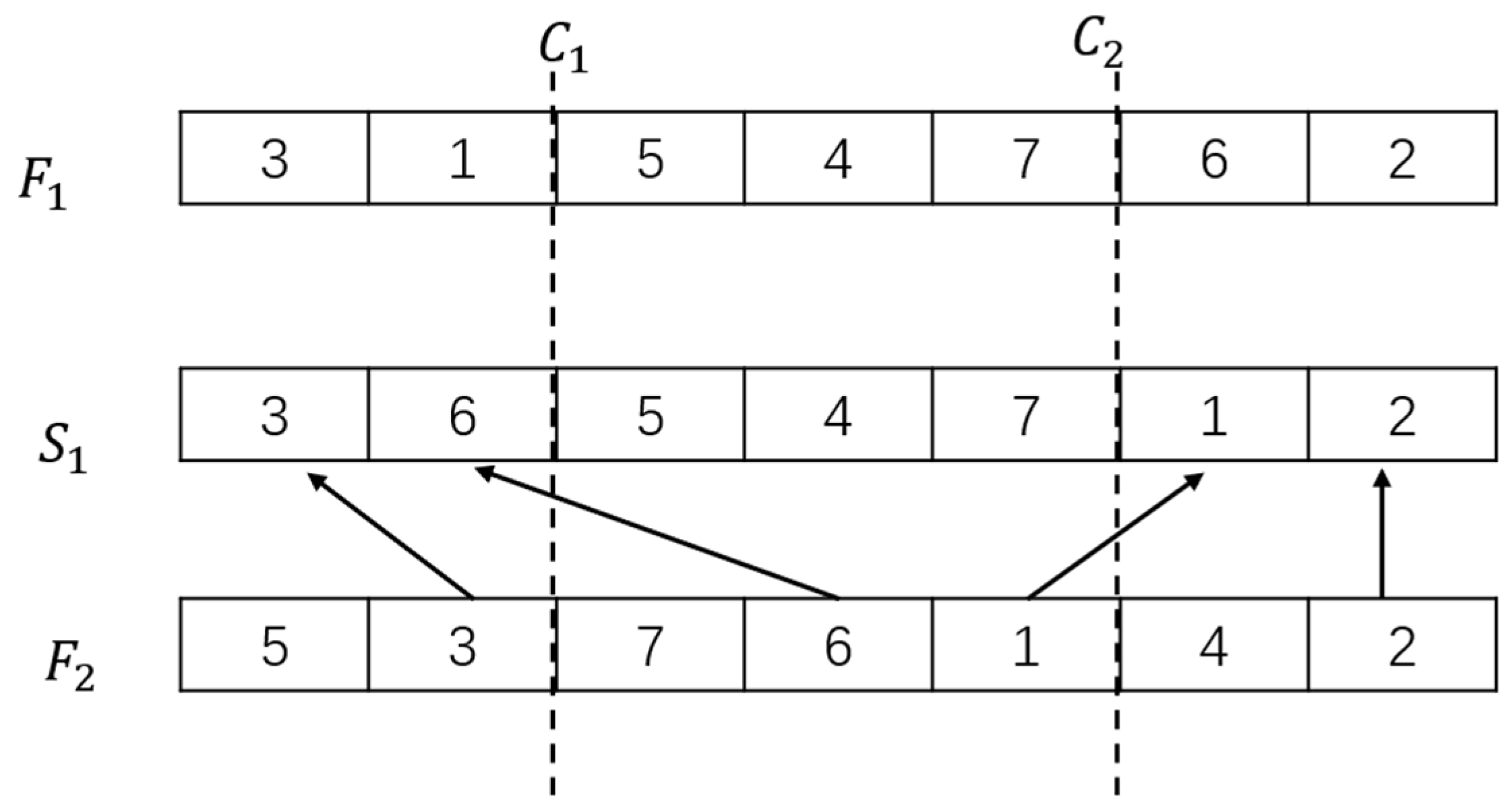

4.1.2. Decoding Strategy

- (1)

- The required fixture or geometric position for EV- and FV-specific tasks is compatible.

- (2)

- The combined workload of both task types does not exceed the cycle time CT.

4.2. Parameter Selection Justification

4.3. Generation of Initial Population

- (1)

- Extract tasks without predecessors or whose predecessors have been completed from task set I, forming a candidate set P;

- (2)

- Randomly select task and add it to the chromosome sequence, then remove it from P;

- (3)

- Update the candidate set P and repeat the operation until all tasks are assigned.

- (4)

- Repeat the above process NP times to obtain an initial population containing NP feasible chromosomes.

4.4. Fitness Evaluation

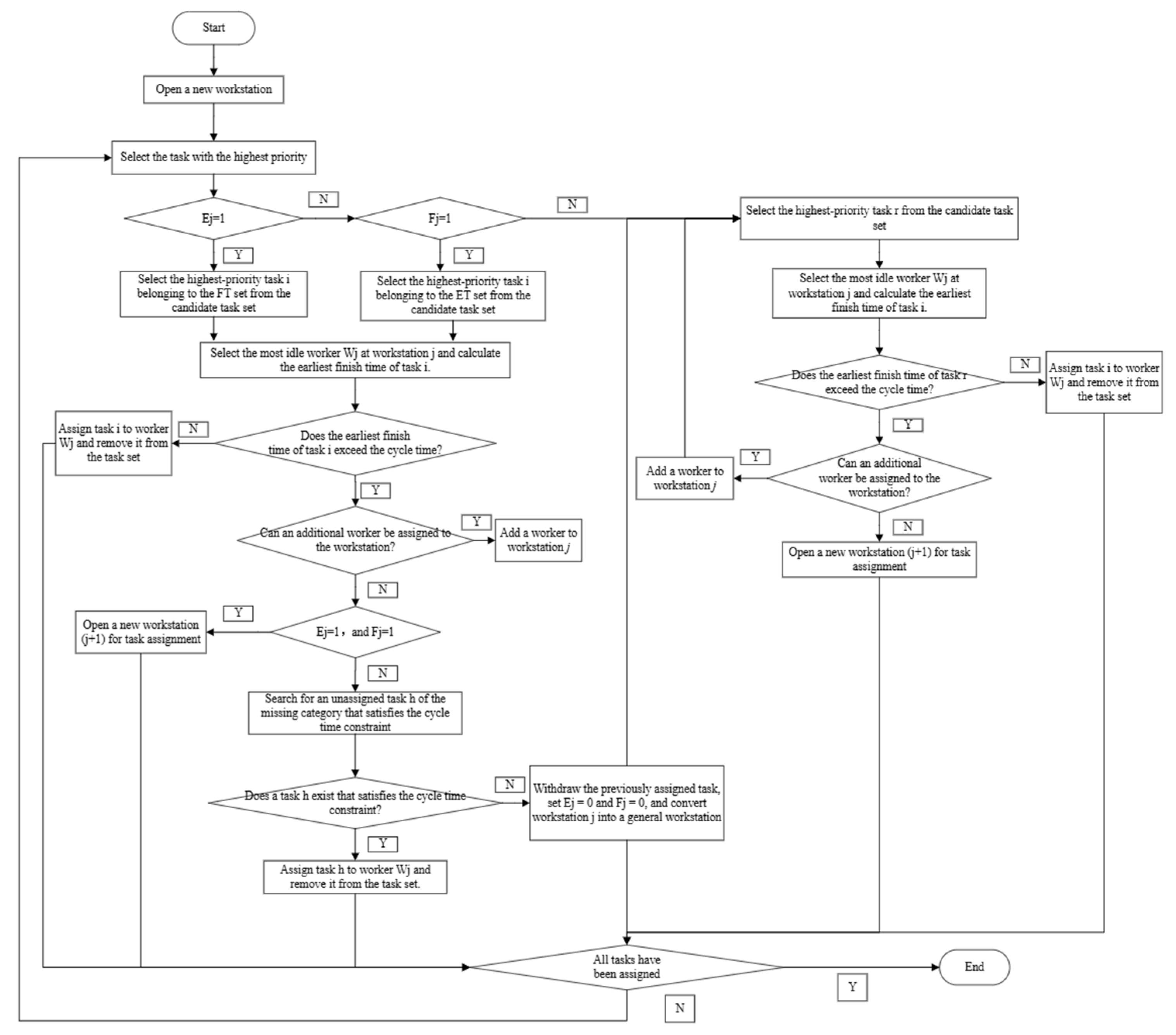

4.5. Genetic Operators

4.5.1. Selection Operator Design

4.5.2. Crossover Operator Design

4.5.3. Mutation Operator Design

4.6. Termination Criteria

4.7. Summary

5. Case Study and Experimental Validation

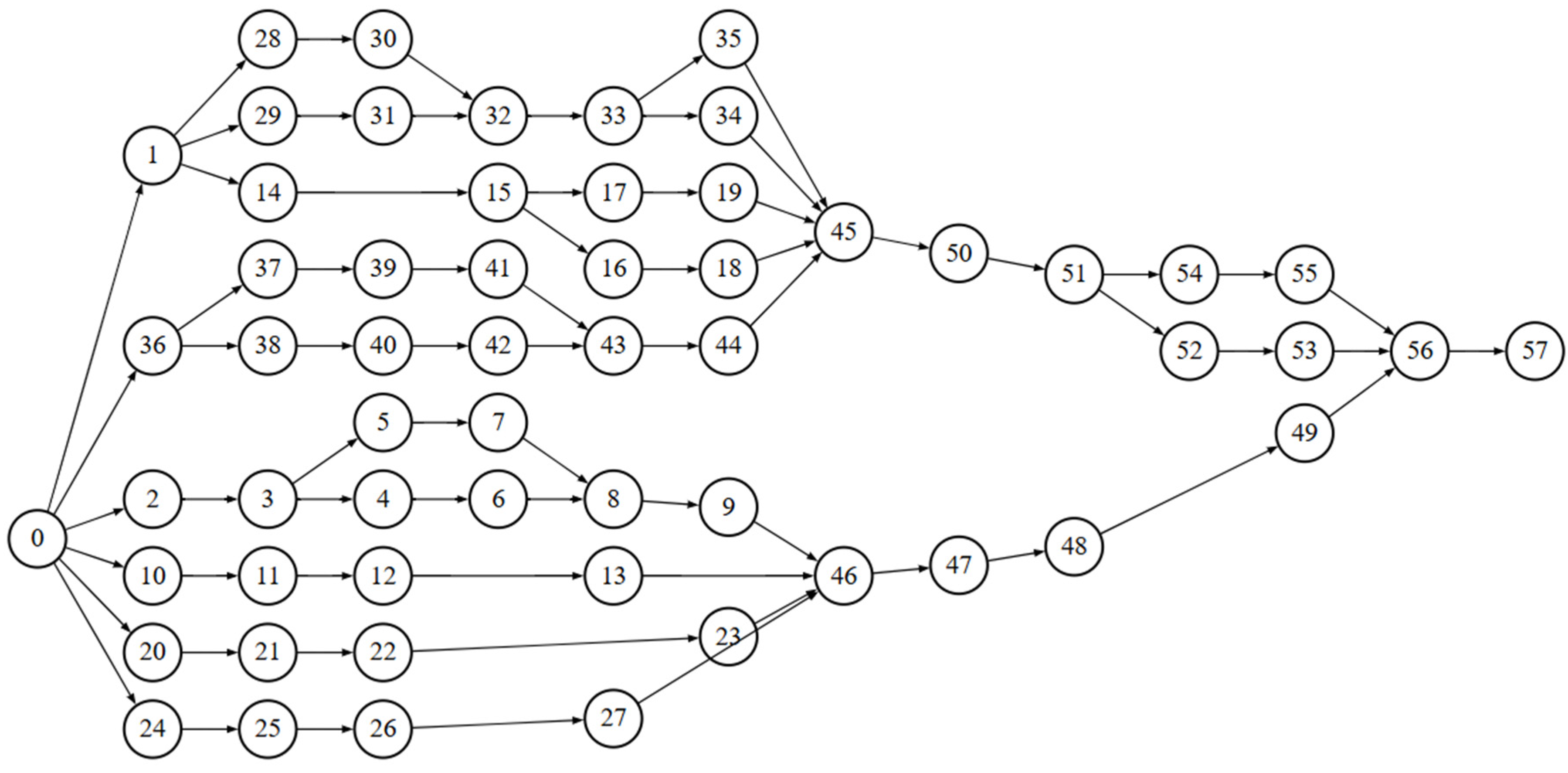

5.1. Assembly Line Data

5.2. Results and Discussion

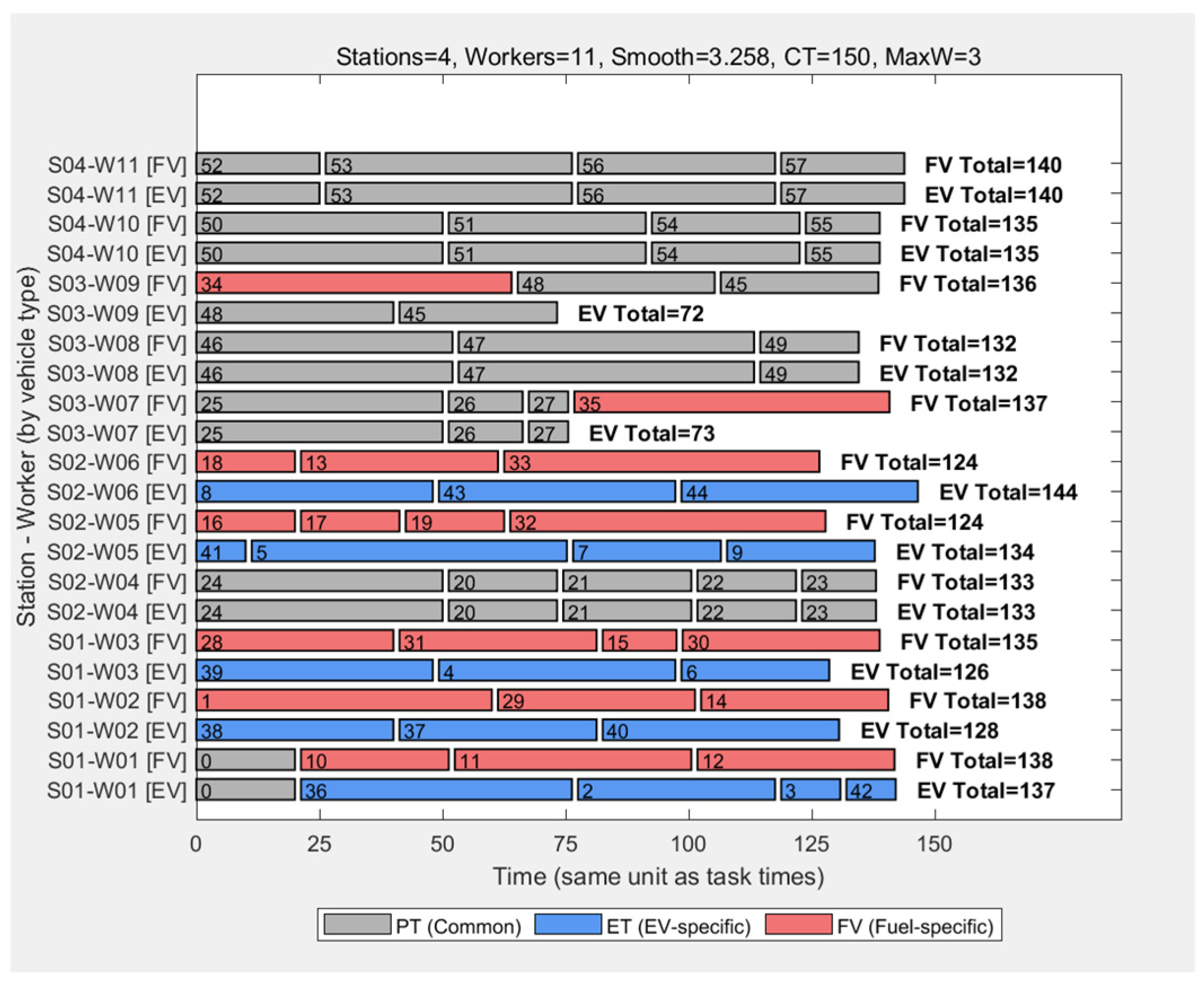

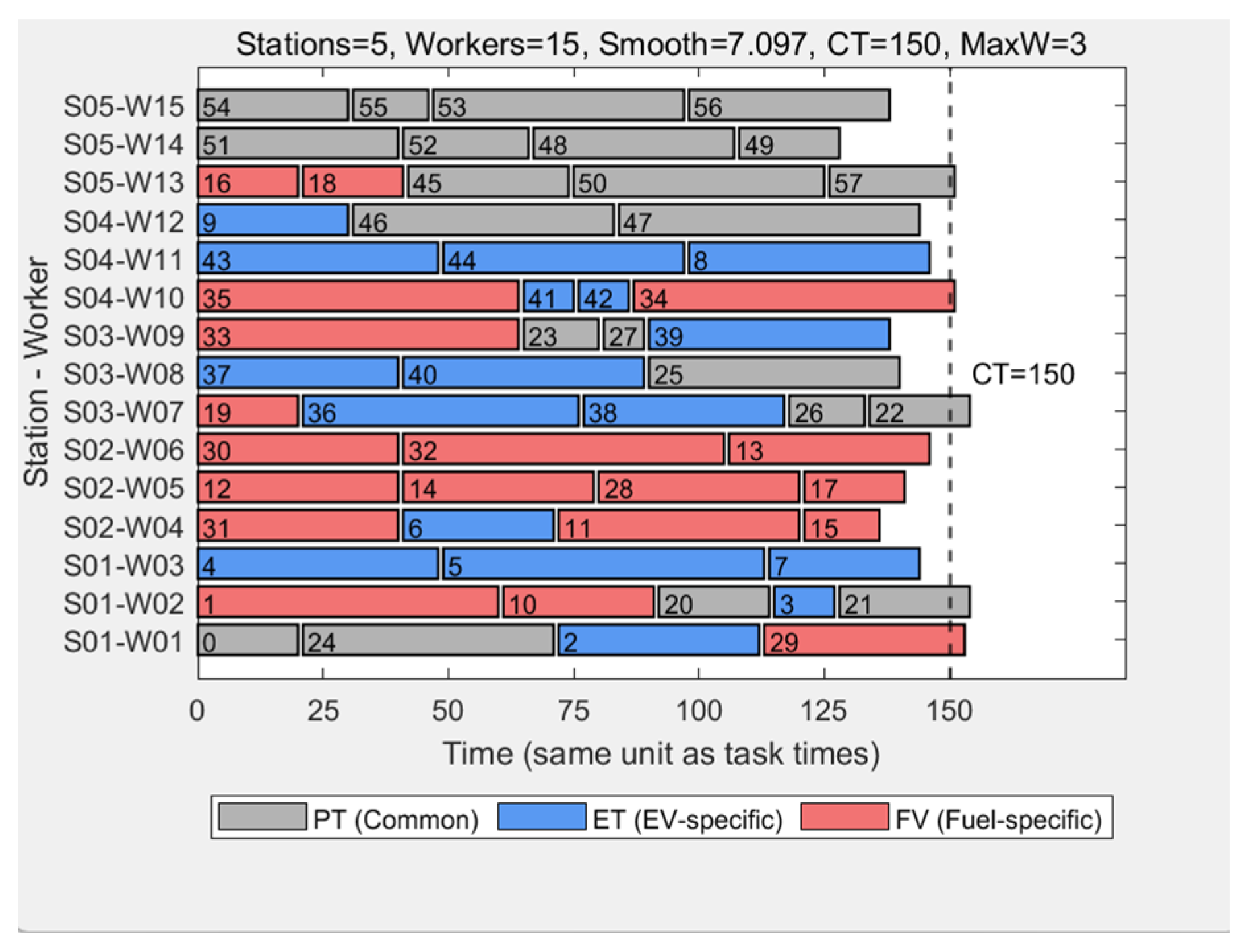

5.2.1. Experimental Results Presentation

5.2.2. Comparative Analysis of Results

- (1)

- Number of Workstations: After optimization, the required number of workstations was reduced to four, representing a 25% decrease compared with the baseline model. This indicates an improvement in space efficiency and an enhancement in task grouping.

- (2)

- Number of workers: After optimization, the total number of workers decreased from 15 to 11, a reduction of 27%.

- (3)

- Smoothness index: The smoothness index dropped from 7.08 to 3.26, a decrease of nearly 50%, indicating a more balanced workload among workers.

- (4)

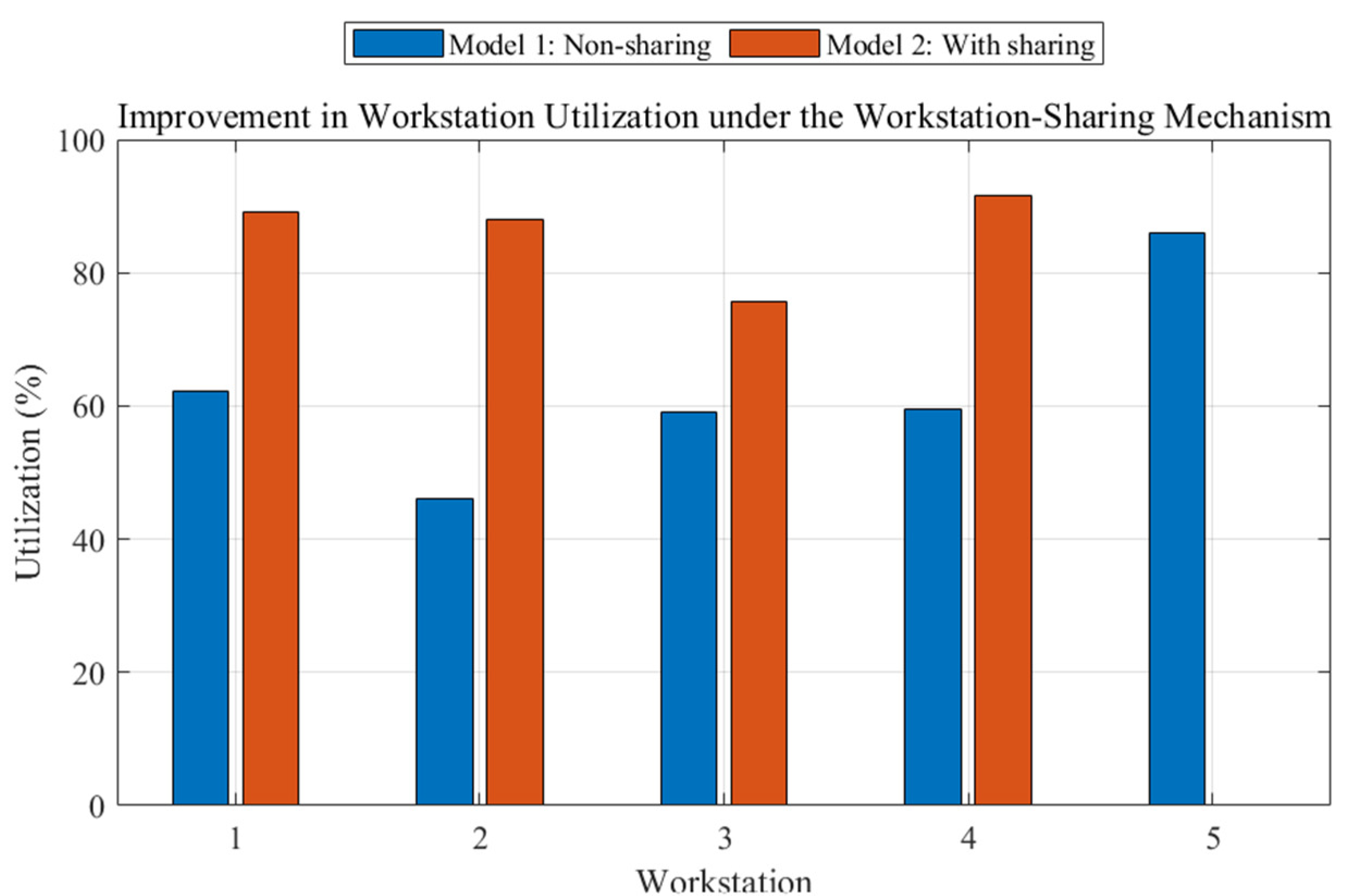

- Worker load efficiency: The average worker load rate increased from 63% to 86%, resulting in a 23% improvement in labor productivity and workload balance.

- (5)

- Task allocation rationality: Dedicated EV tasks and dedicated FV tasks are assembled on shared workstations, reducing idle workstations and enabling tasks with structural differences between EV and FV to share workstations.

5.2.3. Verification of the Workstation-Sharing Effect

5.3. Summary of Case Findings

6. Conclusions and Future Work

6.1. Conclusions

6.2. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MMuALBP-WS | Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem, considering Workstation Sharing |

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| FV | Fuel vehicle |

| EV | Electric vehicle |

| IGV | Improved genetic algorithm |

| ALBP | Assembly Line Balancing Problem |

| SALBP | Single-Model Assembly Line Balancing Problem |

| MALBP | Mixed-Model Assembly Line Balancing Problem |

| MuALBP | Multi-Manned Assembly Lines Problem |

| MMuALBP | Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| ACO | Ant Colony Optimization |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| SA | Simulated Annealing |

| ABC | Artificial Bee Colony |

| VNS | Variable Neighborhood Search |

| ET | EV-exclusive tasks |

| FT | FV-exclusive tasks |

References

- Agency (IEA), I.E. Global Electric Vehicle Outlook 2025: Scaling up the Transition to E-Mobility; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cimen, T.; Baykasoğlu, A.; Akyol, S. Assembly Line Rebalancing and Worker Assignment Considering Ergonomic Risks in an Automotive Parts Manufacturing Plant. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2022, 13, 363–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, C.; Scholl, A. A Survey on Problems and Methods in Generalized Assembly Line Balancing. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 168, 694–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, S.G. Assembly Line Balancing and Group Working: A Heuristic Procedure for Workers’ Team Formation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2006, 44, 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Pilati, F.; Ferrari, E.; Gamberi, M.; Margelli, S. Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing: Workforce Synchronization for Big Data Sets Through Simulated Annealing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattahi, P.; Roshani, A.; Roshani, A. A Mathematical Model and Ant Colony Algorithm for Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 53, 363–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryton, B. Balancing of a Continuous Production Line. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, S.-G.; Zhang, Y.-B.; Sang, C.-Y.; Liu, H. A Genetic Algorithm for Balancing and Sequencing of Mixed-Model Two-Sided Assembly Line with Unpaced Synchronous Transfer. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 146, 110638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, U.; Toklu, B. Balancing of Mixed-Model Two-Sided Assembly Lines. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2009, 57, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomopoulos, N.T. Line Balancing-Sequencing for Mixed-Model Assembly. Manag. Sci. 1967, 14, B-59–B-75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.D.; Villa, C.D. On a Multiproduct Assembly Line-Balancing Problem. AIIE Trans. 1970, 2, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilarinho, P.; Simaria, A.S.; Pedroso, L. A Two-Stage Heuristic Method for Balancing Mixed-Model Assembly Lines with Parallel Workstations. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2002, 40, 1405–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.-Y.; Lee, A.H.I. An Evolutionary Genetic Algorithm for a Multi-Objective Two-Sided Assembly Line Balancing Problem: A Case Study of Automotive Manufacturing Operations. Qual. Technol. Quant. Manag. 2023, 20, 66–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, A.; Sedighi, A. A Cost-Oriented Model for Balancing Mixed-Model Assembly Lines with Multi-Manned Workstations. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 16, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellegöz, T. Assembly Line Balancing Problems with Multi-Manned Stations: A New Mathematical Formulation and Gantt Based Heuristic Method. Ann. Oper. Res. 2017, 253, 377–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, T.C.; Pastre, G.V.; Michels, A.S.; Magatão, L. Flexible Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem: Model, Heuristic Procedure, and Lower Bounds for Line Length Minimization. Omega 2020, 95, 102042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, A.S.; Lopes, T.C.; Magatão, L. An Exact Method with Decomposition Techniques and Combinatorial Benders’ Cuts for the Type-2 Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshani, A.; Ghazi Nezami, F. Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem: A Mathematical Model and a Simulated Annealing Approach. Assem. Autom. 2017, 37, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Machouti, S.; Hlyal, M.; El Alami, J. A Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for Multi-Objective Multi-Manned Assembly Line Worker Allocation and Balancing Problem. Eng. Proc. 2025, 97, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, M.; Kellegöz, T. Benders’ Decomposition Based Exact Solution Method for Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem with Walking Workers. Ann. Oper. Res. 2023, 321, 507–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshani, A.; Paolucci, M.; Giglio, D.; Tonelli, F. A Hybrid Adaptive Variable Neighbourhood Search Approach for Multi-Sided Assembly Line Balancing Problem to Minimise the Cycle Time. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 59, 3696–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, B.S.; Fabrycky, W.J. Systems Engineering and Analysis; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Meerkov, S.M. Production Systems Engineering; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B. Manufacturing Systems Design and Analysis; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Eun, Y.; Liu, K.; Meerkov, S.M. Production Systems with Cycle Overrun: Modelling, Analysis, Improvability and Bottlenecks. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2022, 60, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourmohammadi, A.; Fathi, M.; Ng, A.H.C.; Mahmoodi, E. A Genetic Algorithm for Heterogenous Human-Robot Collaboration Assembly Line Balancing Problems. Procedia CIRP 2022, 107, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jia, X.; He, Q. A Novel Bi-Level Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Integrated Assembly Line Balancing and Part Feeding Problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 580–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharia, P.T.; Nearchou, A.C. A New Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Solving the Fuzzy Stochastic Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Wang, L. A Synergistic Genetic and Particle Swarm Optimization Approach for Multi-Objective Process Parameter Optimization in Reconfigurable Assembly Lines. Informatica 2025, 49, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzam, N.; Elakkad, A. Time and Space Multi-Manned Assembly Line Balancing Problem Using Genetic Algorithm. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2021, 14, 733–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didden, J.B.H.C.; Lefeber, E.; Adan, I.J.B.F.; Panhuijzen, I.W.F. Genetic Algorithm and Decision Support for Assembly Line Balancing in the Automotive Industry. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2023, 61, 3377–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.-G.; Sang, C.-Y.; Liu, A.-W.; Liu, H. Solving Type-I Unpaced Synchronous Mixed-Model Two-Sided Assembly Line Balancing Problem Using a Genetic Algorithm. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 184, 107257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Represent task | |

| Represent workstations | |

| Product type indicator, for FV, For EV. | |

| Task set | |

| Workstation set | |

| Set of workers assigned to stations, | |

| Set of EV-specific tasks | |

| Set of FV-specific task | |

| PT | Set of shared tasks |

| Set of immediate predecessor tasks of task i | |

| Set of all predecessor tasks of task i | |

| Set of tasks with no predecessors, | |

| Upper bound on the number of workers allowed per workstation. | |

| Operation time of task i for product type m | |

| Operation time of task i for product type m | |

| Finish time of task i for product type m | |

| Total assembly time of worker w | |

| Average completion time of all workers | |

| Completion time associated with task i | |

| Cycle time of the production line | |

| A sufficiently large positive constant | |

| Binary variable equal to 1 when task i is handled by worker w, and otherwise, 0. | |

| Binary variable equal to 1 when task i is assigned to workstation j; otherwise, 0. | |

| Binary variable taking value 1 if worker w operates at workstation j; otherwise, 0. | |

| Oih | Indicator variable equal to 1 when tasks i and h share the same worker, with i preceding h in sequence. |

| Binary indicator that equals 1 if, within the same station, task i is processed before p. | |

| Utilization flag for workstation j; 1 if active, 0 otherwise. | |

| Worker assignment flag: 1 if worker w performs at least one task. | |

| Binary variable: equals 1 if workstation j is a shared (mixed) workstation; otherwise, 0. | |

| Binary variable: 1 if workstation j contains tasks belonging to ET; otherwise, 0. | |

| Binary variable: 1 if workstation j contains tasks belonging to FT; otherwise, 0. |

| Task ID | Task | Task Time (s) | Immediate Predecessors | Task Set |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Chassis positioning and initial alignment | 20 | - | PT |

| 1 | Tighten the engine | 60 | 0 | FT |

| 2 | Fasten the drive motor | 40 | 0 | ET |

| 3 | Place the motor on both left and right mounts | 12 | 2 | ET |

| 4 | Install the left hover | 48 | 3 | ET |

| 5 | Install the right mount | 64 | 3 | ET |

| 6 | Install the left mount to the subframe end | 30 | 4 | ET |

| 7 | Install the right mount to the subframe end | 30 | 5 | ET |

| 8 | After installation, mount it onto the drive motor | 48 | 6, 7 | ET |

| 9 | After installation, mount it to the subframe end | 30 | 8 | ET |

| 10 | Install the left suspension bracket of the engine | 30 | 0 | FT |

| 11 | Install the mount on the right side of the engine | 48 | 10 | FT |

| 12 | Install the left suspension of the engine | 40 | 11 | FT |

| 13 | Install the right-side mount of the engine | 40 | 12 | FT |

| 14 | The gearbox is rear mounted onto the gearbox | 38 | 1 | FT |

| 15 | The transmission is rear mounted onto the vehicle body | 15 | 14 | FT |

| 16 | Install the transmission to the engine | 20 | 15 | FT |

| 17 | Install the transmission to the engine | 20 | 15 | FT |

| 18 | Place the three-way catalytic converter assembly | 20 | 16 | FT |

| 19 | Install the three-way catalytic converter assembly | 20 | 17 | FT |

| 20 | Install the vacuum tank assembly | 22 | 0 | PT |

| 21 | Install the small bracket assembly of the vacuum pump | 26 | 20 | PT |

| 22 | Tighten the bolts of the vacuum pump bracket | 20 | 21 | PT |

| 23 | Connect the front wiring harness | 15 | 22 | PT |

| 24 | Place the brake pedal assembly | 50 | 0 | PT |

| 25 | Install the brake pedal assembly | 50 | 24 | PT |

| 26 | Install the pin shaft and lock pin | 15 | 25 | PT |

| 27 | Apply lubricating grease | 8 | 26 | PT |

| 28 | Place the three-way catalytic converter assembly | 40 | 1 | FT |

| 29 | Install the three-way catalytic converter assembly | 40 | 1 | FT |

| 30 | Install the parking brake control assembly | 40 | 28 | FT |

| 31 | Connect the wiring harness | 40 | 29 | FT |

| 32 | Place the handbrake cable assembly onto the front floor | 64 | 30, 31 | FT |

| 33 | Install the handbrake cable assembly to the front floor | 64 | 32 | FT |

| 34 | Place the handbrake cable assembly on the rear floor | 64 | 33 | FT |

| 35 | Install the handbrake cable assembly to the rear floor | 64 | 33 | FT |

| 36 | Install the charging and distribution system | 55 | 0 | ET |

| 37 | Place the power battery | 40 | 36 | ET |

| 38 | Lift the power tray | 40 | 36 | ET |

| 39 | Place the bolts for the power battery | 48 | 37 | ET |

| 40 | Pre-tighten the bolts of the power battery | 48 | 38 | ET |

| 41 | Tighten the bolts of the left power battery | 10 | 39 | ET |

| 42 | Tighten the bolts of the right power battery | 10 | 40 | ET |

| 43 | Connect the grounding bolt | 48 | 41, 42 | ET |

| 44 | Connect the front wiring harness | 48 | 43 | ET |

| 45 | Add the brake fluid reservoir cap | 32 | 34, 35, 18, 19, 44 | PT |

| 46 | Arrange the rear brake hard pipe assembly | 52 | 9, 13, 23, 27 | PT |

| 47 | After installation, brake the hard pipe assembly | 60 | 46 | PT |

| 48 | Connect the front brake hard pipe assembly | 40 | 47 | PT |

| 49 | Tighten the brake hard pipe assembly before fastening | 20 | 48 | PT |

| 50 | Place the brake master cylinder booster assembly | 50 | 45 | PT |

| 51 | Connect the brake master cylinder booster assembly | 40 | 50 | PT |

| 52 | Connect the brake master cylinder | 25 | 51 | PT |

| 53 | Tighten the brake master cylinder | 50 | 52 | PT |

| 54 | Install the ABS module assembly onto the bracket | 30 | 51 | PT |

| 55 | Install the ABS bracket assembly onto the vehicle body | 15 | 54 | PT |

| 56 | Place the rear wheel speed sensor | 40 | 49, 53, 55 | PT |

| 57 | Install the rear wheel speed sensor | 25 | 56 | PT |

| Worker | EV (Model 1) | FV (Model 1) | EV (Model 2) | FV (Model 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worker 1 | 110 | 110 | 137 | 138 |

| Worker 2 | 60 | 138 | 128 | 138 |

| Worker 3 | 142 | 0 | 126 | 135 |

| Worker 4 | 30 | 103 | 133 | 133 |

| Worker 5 | 0 | 138 | 134 | 124 |

| Worker 6 | 0 | 144 | 144 | 124 |

| Worker 7 | 130 | 55 | 73 | 137 |

| Worker 8 | 138 | 50 | 132 | 132 |

| Worker 9 | 71 | 87 | 72 | 136 |

| Worker 10 | 20 | 128 | 135 | 135 |

| Worker 11 | 144 | 0 | 140 | 140 |

| Worker 12 | 142 | 112 | – | – |

| Worker 13 | 107 | 147 | – | – |

| Worker 14 | 125 | 125 | – | – |

| Worker 15 | 135 | 135 | – | – |

| Total Idle Time | 896 | 778 | 296 | 178 |

| Total Available Working Time | 2250 | 2250 | 1650 | 1650 |

| Overall Load Rate | 60.18% | 65.42% | 82.06% | 89.21% |

| Workstation | Workers | Task Time per Worker (s) | Total Work Time (s) | Total Available Time (s) | Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (EV) | 3 | 110, 60, 142 | 312 | 450 | 69.33% |

| S1 (FV) | 3 | 110, 138, 0 | 248 | 450 | 55.11% |

| S2 (EV) | 3 | 30, 0, 0 | 30 | 450 | 6.67% |

| S2 (FV) | 3 | 103, 138, 144 | 385 | 450 | 85.56% |

| S3 (EV) | 3 | 130, 138, 71 | 339 | 450 | 75.33% |

| S3 (FV) | 3 | 55, 50, 87 | 192 | 450 | 42.67% |

| S4 (EV) | 3 | 20, 144, 132 | 296 | 450 | 65.78% |

| S4 (FV) | 3 | 128, 0, 112 | 240 | 450 | 53.33% |

| S5 (EV) | 3 | 107, 125, 135 | 367 | 450 | 81.56% |

| S5 (FV) | 3 | 147, 125, 135 | 407 | 450 | 90.44% |

| Average | - | - | - | - | 62.58% |

| Workstation | Workers | Task Time per Worker (s) | Total Work Time (s) | Total Available Time (s) | Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 (EV) | 3 | 137, 128, 126 | 391 | 450 | 86.89% |

| S1 (FV) | 3 | 138, 138, 135 | 411 | 450 | 91.33% |

| S2 (EV) | 3 | 133, 134, 144 | 411 | 450 | 91.33% |

| S2 (FV) | 3 | 133, 124, 124 | 381 | 450 | 84.67% |

| S3 (EV) | 3 | 73, 132, 72 | 277 | 450 | 61.56% |

| S3 (FV) | 3 | 137, 132, 136 | 405 | 450 | 90.00% |

| S4 (EV) | 2 | 135, 140 | 275 | 300 | 91.67% |

| S4 (FV) | 2 | 135, 140 | 275 | 300 | 91.67% |

| Average | 86.14% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, L.; Sukhotu, V. Optimization of Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Lines for Fuel–Electric Vehicle Co-Production Under Workstation Sharing. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120666

Hu L, Sukhotu V. Optimization of Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Lines for Fuel–Electric Vehicle Co-Production Under Workstation Sharing. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):666. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120666

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Lingling, and Vatcharapol Sukhotu. 2025. "Optimization of Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Lines for Fuel–Electric Vehicle Co-Production Under Workstation Sharing" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120666

APA StyleHu, L., & Sukhotu, V. (2025). Optimization of Mixed-Model Multi-Manned Assembly Lines for Fuel–Electric Vehicle Co-Production Under Workstation Sharing. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120666