Thermal Performance Assessment of Lithium-Ion Battery Packs Under Air-Cooling Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Simulation

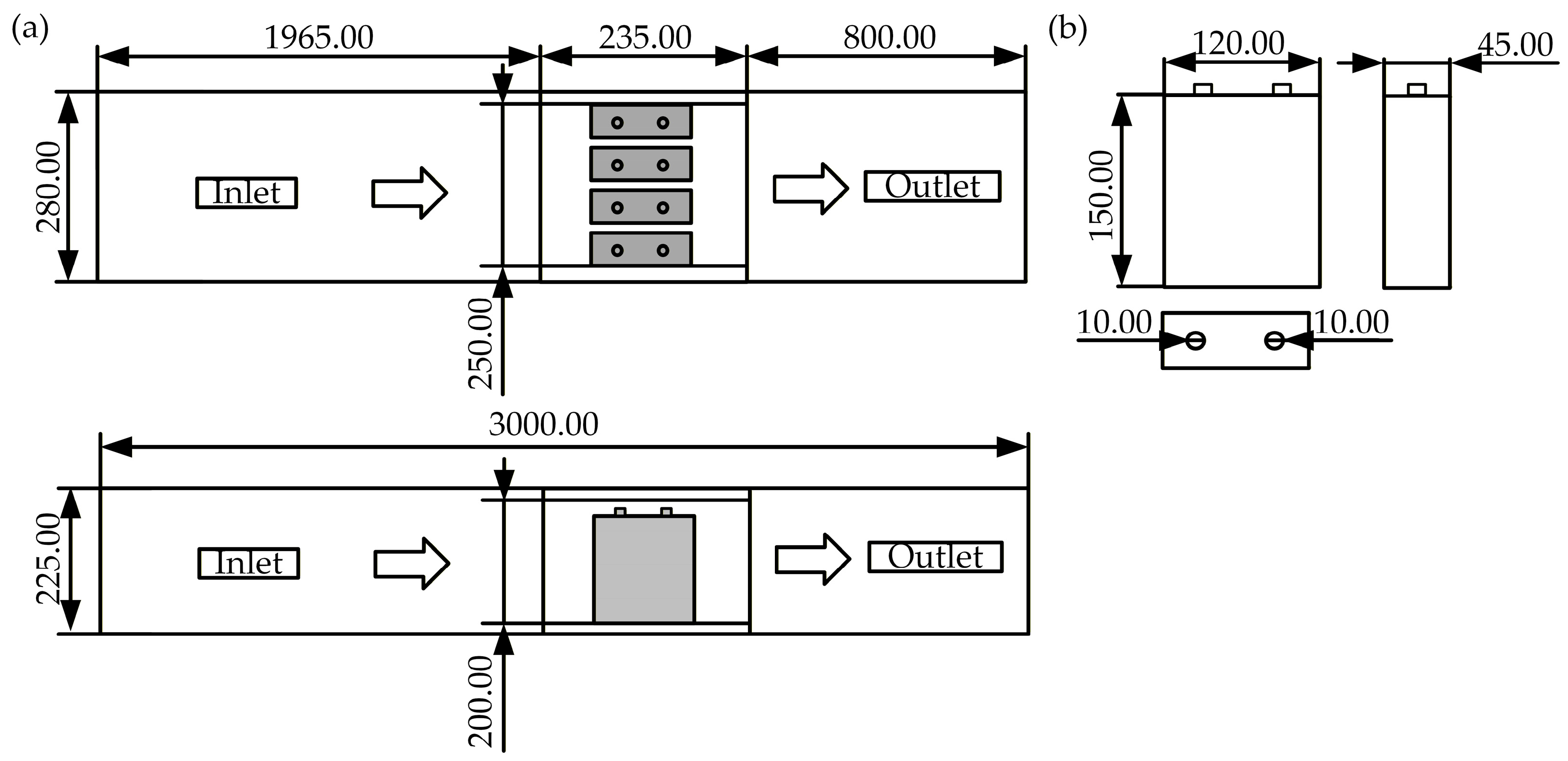

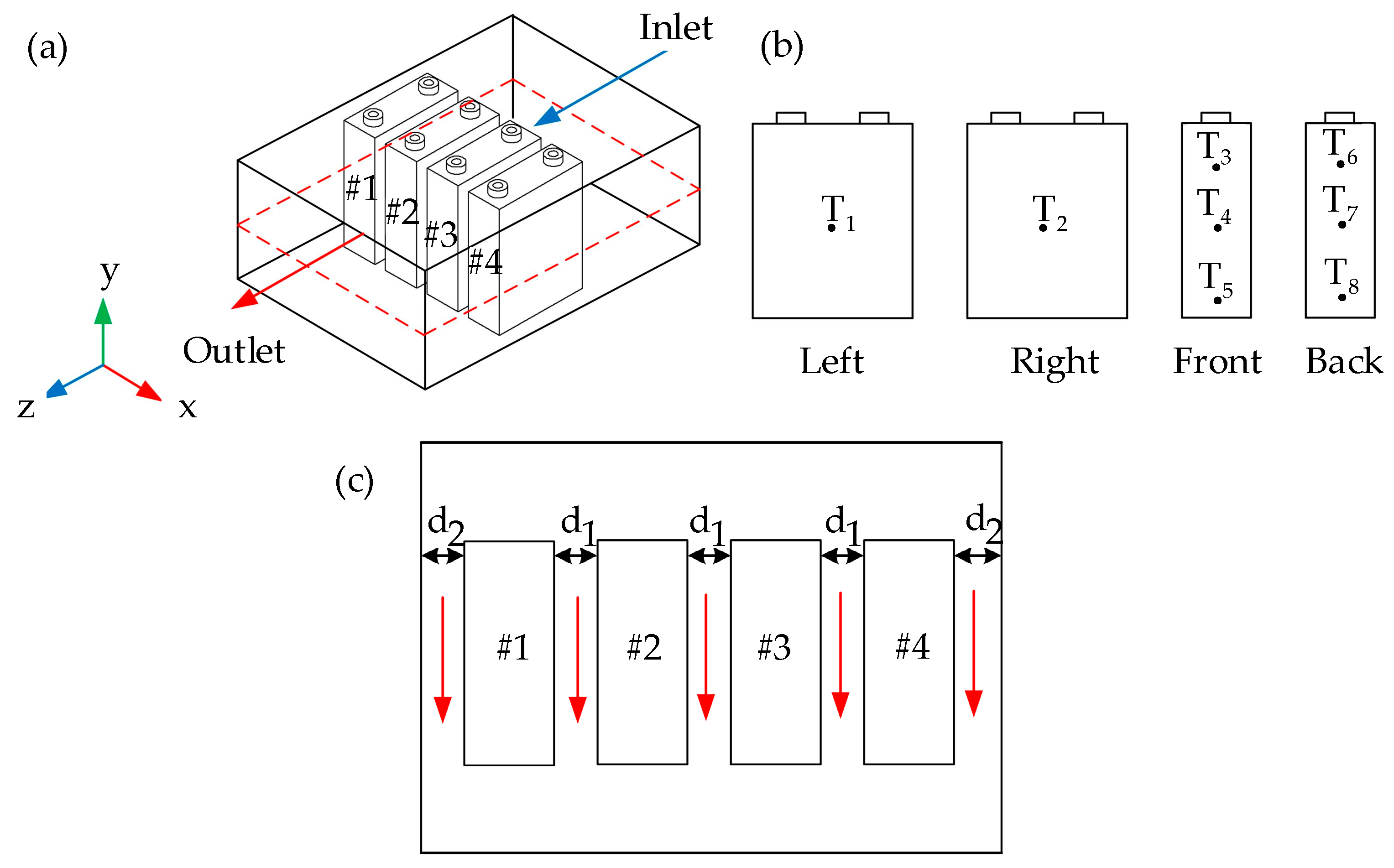

2.1. Geometry Model

2.2. Equations and Methods

2.3. The Simulation Results

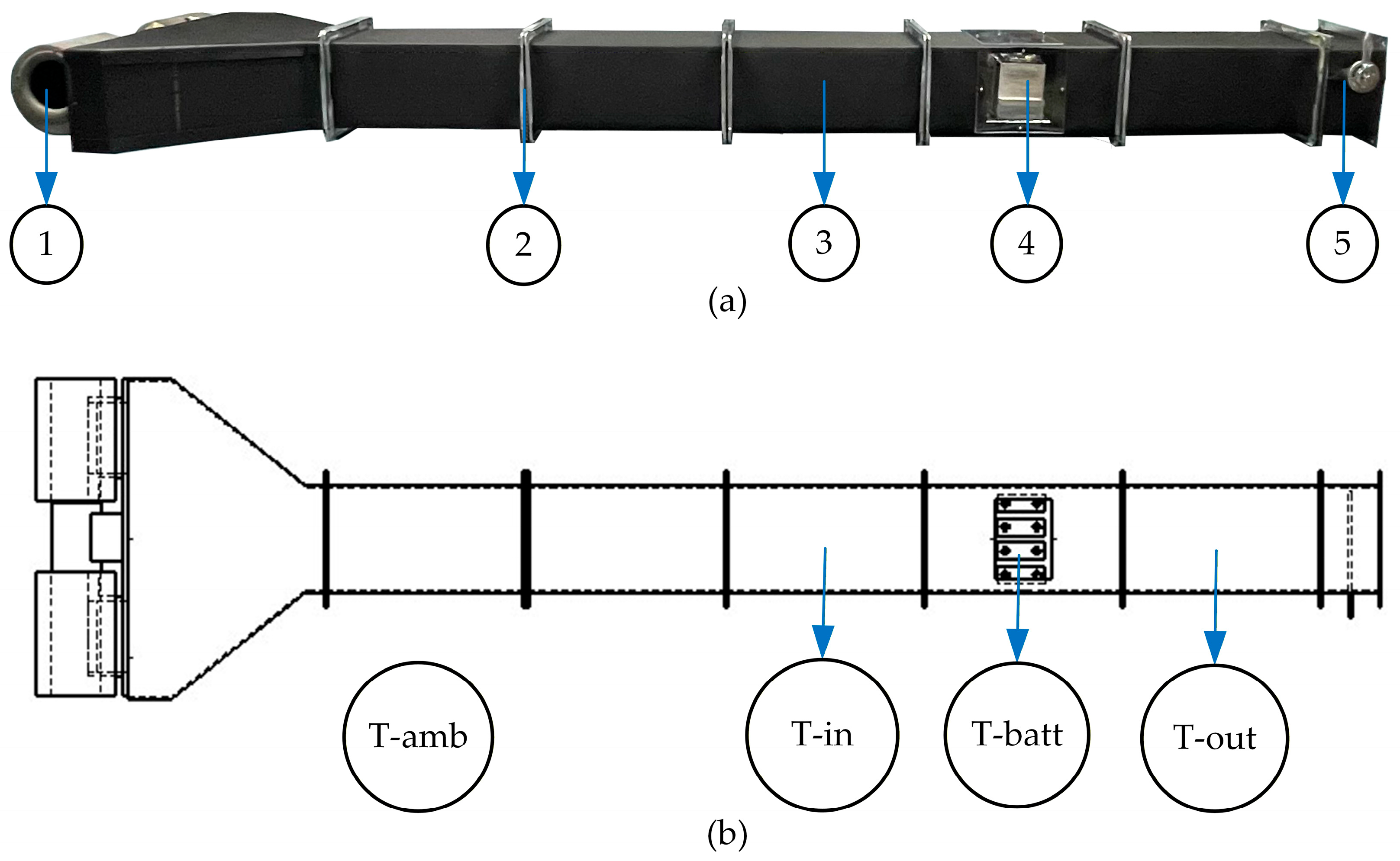

3. Experimental Procedure

3.1. Experimental Preparation

- (1)

- A centrifugal blower with a power rating of 141 W was used to create a pressure difference inside the wind tunnel and was equipped with a speed control system (variable speed drive).

- (2)

- A grille increased air distribution evenly throughout the cross-section.

- (3)

- The air flow rate inside the wind tunnel was controlled at values of 0.50, 0.75, and 1.00 g/s. The average air flow rate across the cross-section was derived from 25 measurements using an Air Velocity and IAQ instrument (Testo 440 dp) connected to a 16 mm vane probe (range: 0.6–50 m/s; accuracy: ±0.2 m/s). The measurement locations were defined according to the Log-Tchebycheff rule, as recommended by ASHRAE Standard 111:2008.

- (4)

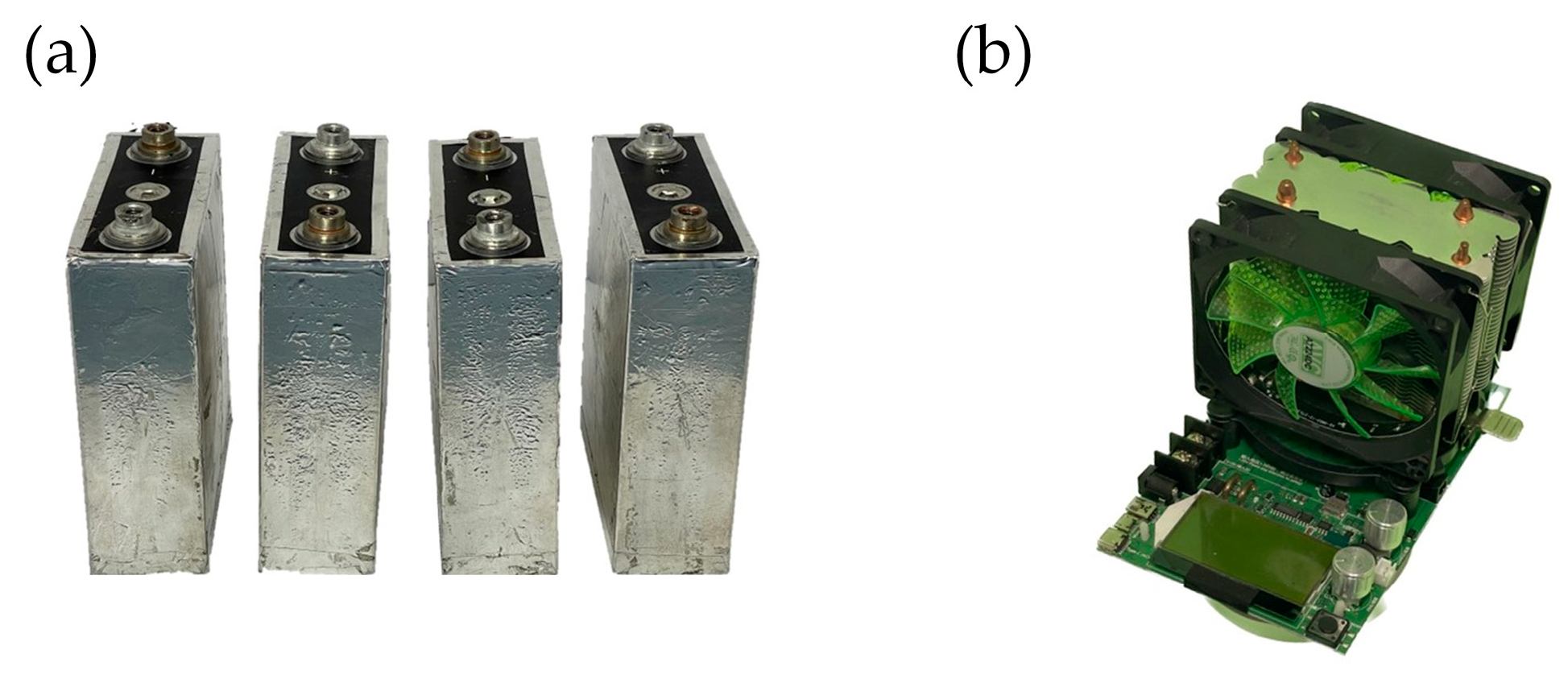

- Location of four prismatic-shaped battery cells: The four battery packs used in the experiment were LiFePO4 prismatic-shaped lithium-ion batteries (Brand: NBCELL) with dimensions of 135.3 × 29.3 × 185.3 mm3. The battery had a capacity of 50 Ah, a nominal voltage of 3.2 volts, and a continuous maximum discharge rate of 3 C-rate. These batteries are commonly used in electric golf carts. In addition, the experimental discharge rate control device was an Electric Load Battery Tester (Brand: Chin) with a power rating of 180 W. It can control a maximum discharge rate of 20 A with a current measurement range of 0.0–20 A, with an accuracy of ± 0.01 A, and a voltage measurement range of 0.0–200 V, with an accuracy of ±0.01 V.

- (5)

- The damper was used to control the mass flow rate.

3.2. Battery Pack and Controlling Device

3.3. Experimental Procedures

4. Results and Discussion

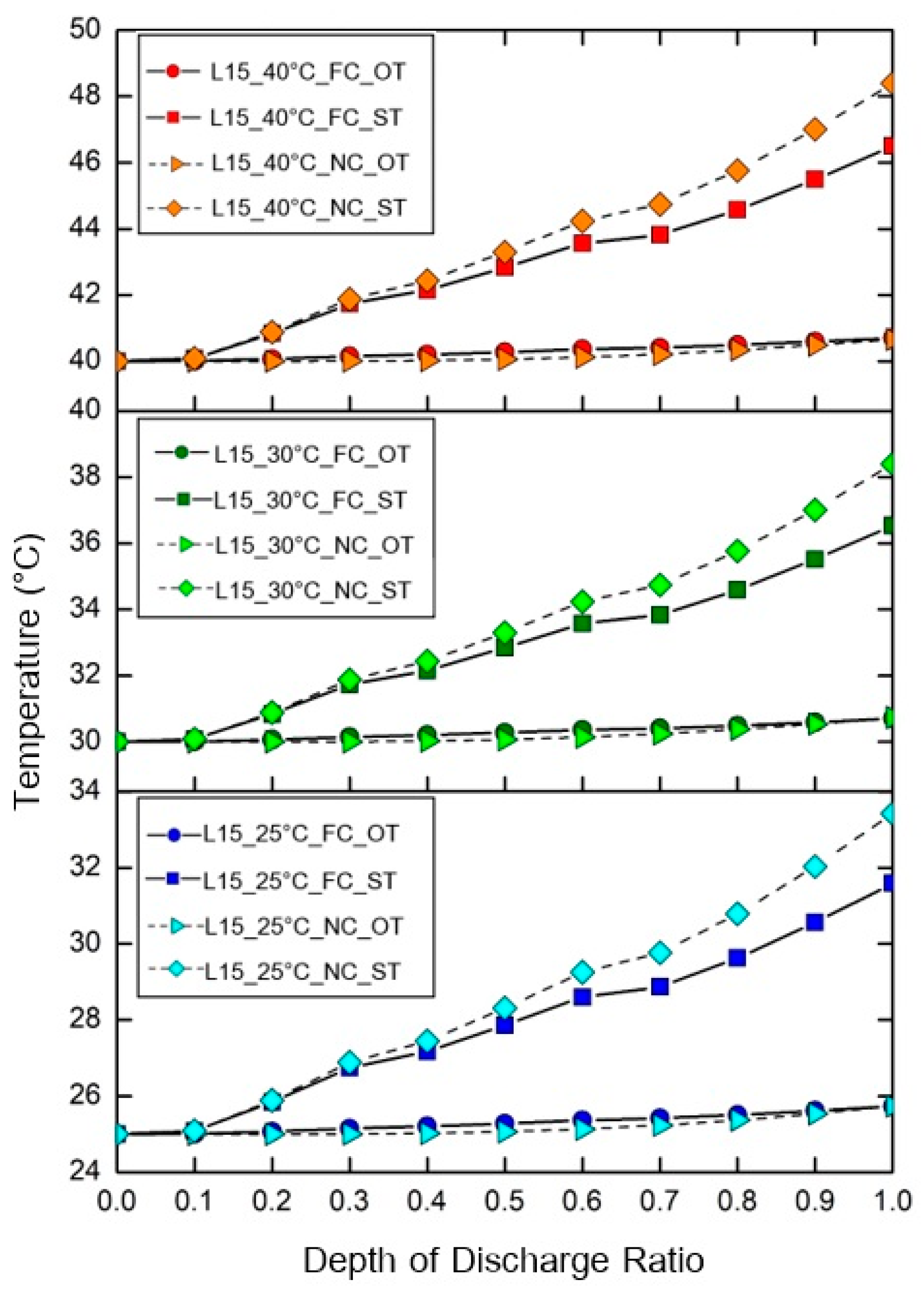

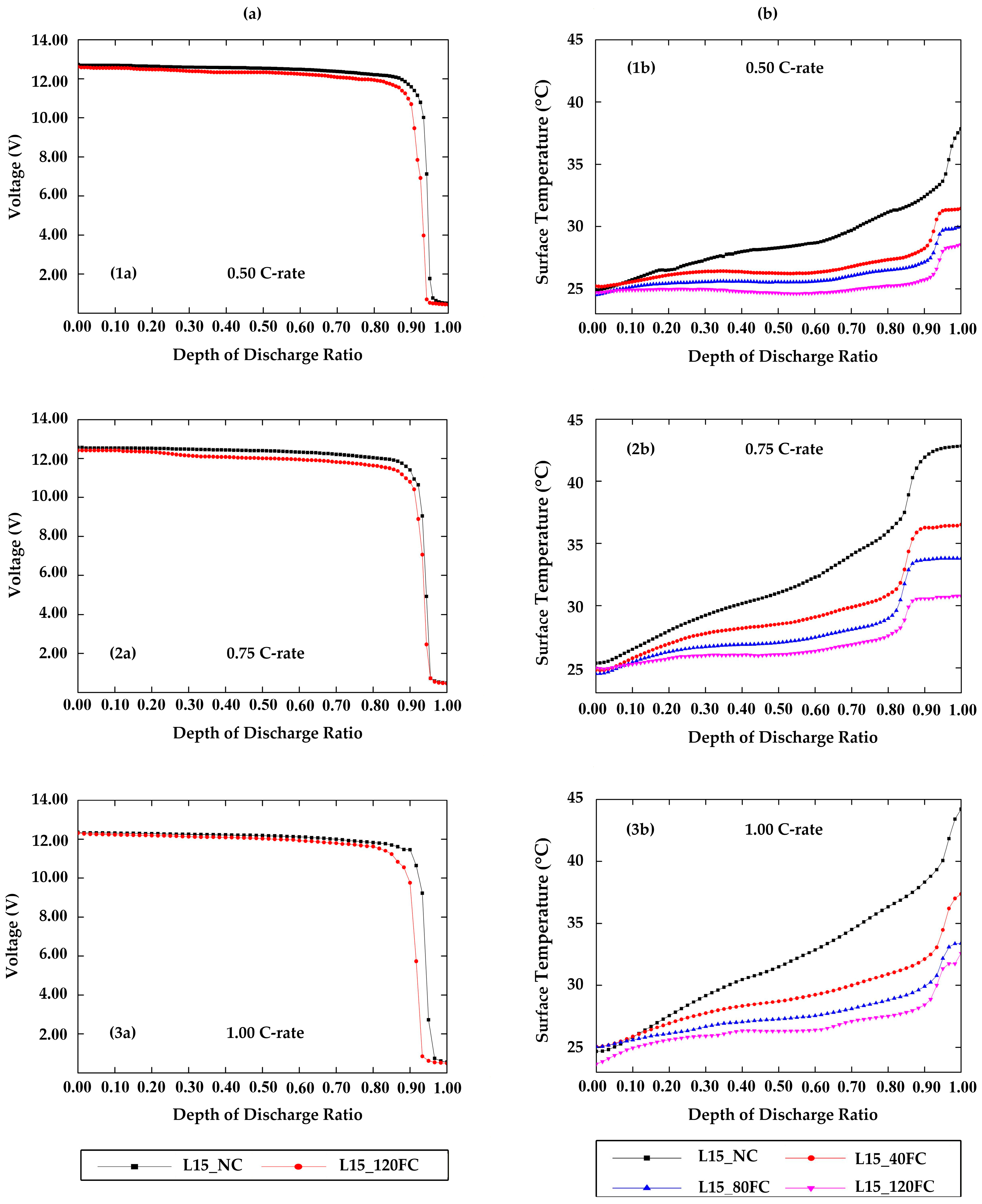

4.1. The Effect of Depth of Discharge (DOD)

4.2. The Effect of Battery Voltage

4.3. The Effect of Battery Cell Spacing

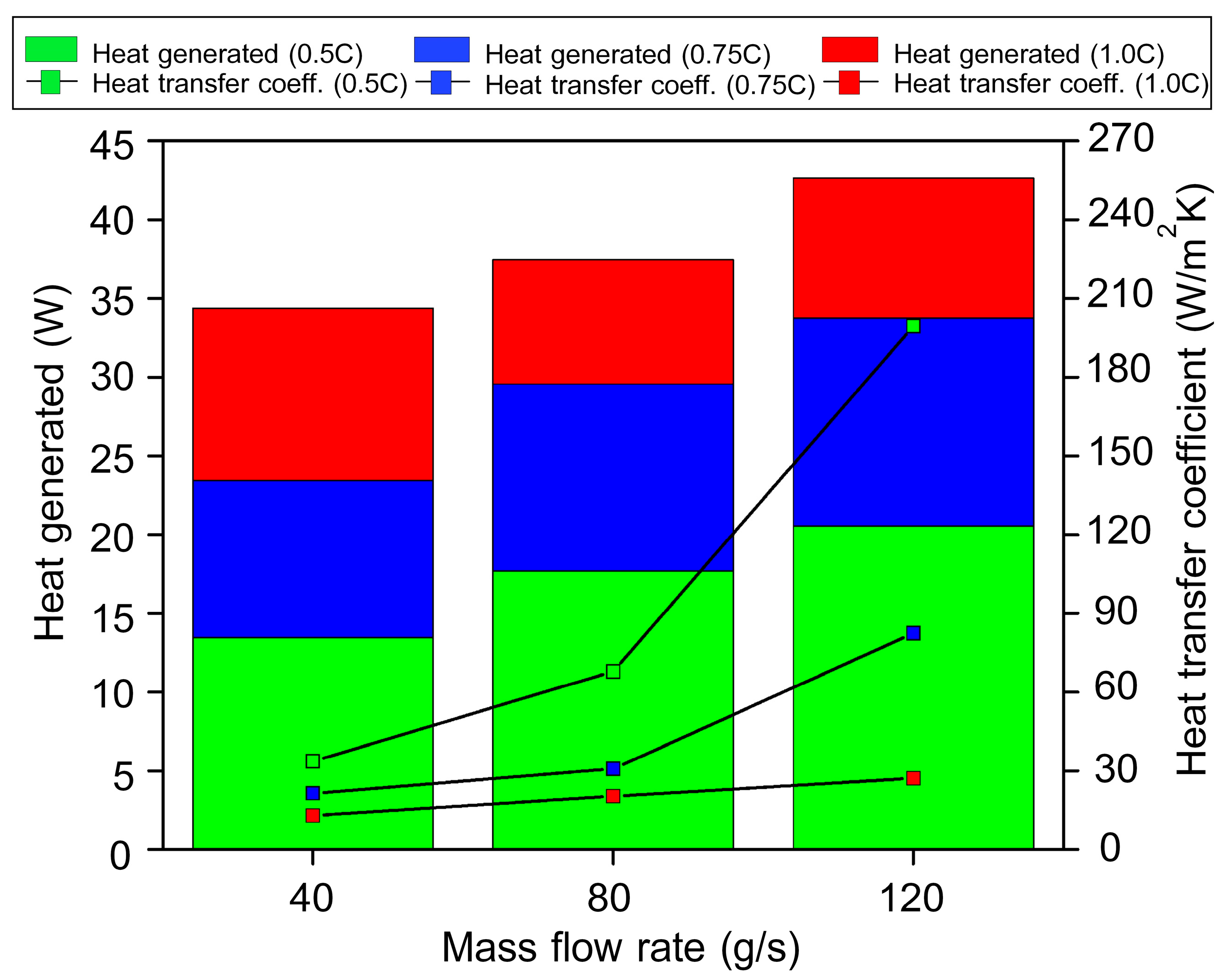

4.4. The Effect of Air Flow Rate

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The battery surface temperature tended to increase, and the average surface temperature of the battery pack was not significantly different when the discharge rate increased.

- (2)

- The voltage difference in the electric vehicle battery pack under conditions of natural convection and forced convection at 120 g/s was only slight until the depth of discharge ratio was in the range of 0.90; the voltage dropped rapidly to the point that there was almost no voltage remaining in the battery. This may have been caused by a reaction of the solution in the battery.

- (3)

- Increasing the battery pack spacing resulted in a downward trend in the surface temperature of the battery pack.

- (4)

- The increased air flow rates resulted in higher heat transfer rates and heat convection coefficients. When the discharge rate increased, the heat value of the battery increased as well, but the heat convection coefficient decreased. The highest heat transfer value was obtained with a battery cell spacing of 15 mm and a discharge depth ratio of 1.00 at forced convection of 120 g/s, and the highest heat convection coefficient was obtained under the condition of a battery cell spacing of 15 mm with a discharge depth ratio of 0.50 and forced convection of 120 g/s.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C-rate | Discharge rate |

| DOD | Depth of discharge |

| EVs | Electric vehicles |

| FC | Forced convection |

| LiFePO4 | Lithium iron phosphate |

| NC | Natural convection |

| T-amb | The ambient temperature |

| T-batt | The battery surface |

| T-in | The inlet of the wind tunnel |

| T-out | The outlet of the wind tunnel |

References

- Etacheri, V.; Marom, R.; Elazari, R.; Salitra, G.; Aurbach, D. Challenges in the development of advanced Li-ion batteries: A review. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 3243–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Li, Y. A flexible-possibilistic stochastic programming method for planning municipal-scale energy system through introducing renewable energies and electric vehicles. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 772–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguemont, J.; Boulon, L.; Dubé, Y. A comprehensive review of lithium-ion batteries used in hybrid and electric vehicles at cold temperatures. Appl. Energy 2016, 164, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Wang, X.; Negnevitsky, M.; Zhang, H. A review of air-cooling battery thermal management systems for electric and hybrid electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2021, 501, 230001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srithai, S.; Pisitsungkakarn, S.S.H.; Sriariyakul, W.; Prusomboon, T.; Ditdanai, P.; Sikhant, A. Numerical Investigation of Thermal Cooling Performance of Prismatic Lithium-Ion Battery Pack for Electric Vehicle. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2024, 923, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, W.-T. Three-dimensional thermal modeling of Li-ion battery cell and 50 V Li-ion battery pack cooled by mini-channel cold plate. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 147, 829–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, S.; Dincer, I.; Agelin-Chaab, M.; Fraser, R.; Fowler, M. Design and simulation of a lithium-ion battery at large C-rates and varying boundary conditions through heat flux distributions. Measurement 2018, 116, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahjalal, M.; Shams, T.; Islam, E.; Alam, W.; Modak, M.; Bin Hossain, S.; Ramadesigan, V.; Ahmed, R.; Ahmed, H.; Iqbal, A. A review of thermal management for Li-ion batteries: Prospects, challenges, and issues. J. Energy Storage 2021, 39, 102518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, M.; Kovalenko, M.V.; Kravchyk, K.V. Challenges and benefits of post-lithium-ion batteries. New J. Chem. 2020, 44, 1677–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abada, S.; Marlair, G.; Lecocq, A.; Petit, M.; Sauvant-Moynot, V.; Huet, F. Safety focused modeling of lithium-ion batteries: A review. J. Power Sources 2016, 306, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausmann, A.; Depcik, C. Expanding the Peukert equation for battery capacity modeling through inclusion of a temperature dependency. J. Power Sources 2013, 235, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, M.; Kong, Q.; McGrory, J.; Fowler, M. Simulation of lithium ion battery replacement in a battery pack for application in electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2017, 349, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, B.; Kamath, H.; Tarascon, J.-M. Electrical Energy Storage for the Grid: A Battery of Choices. Science 2011, 334, 928–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gungor, S.; Cetkin, E.; Lorente, S. Thermal and electrical characterization of an electric vehicle battery cell, an experimental investigation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 212, 118530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgren, J.; Lund, P.D. Effect of extreme temperatures on battery charging and performance of electric vehicles. J. Power Sources 2016, 328, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, F.; Ma, L. Thermal management of cylindrical batteries investigated using wind tunnel testing and computational fluid dynamics simulation. J. Power Sources 2013, 238, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Qu, Z. Lithium–ion battery thermal management using heat pipe and phase change material during discharge–charge cycle: A comprehensive numerical study. Appl. Energy 2019, 242, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Wang, S.; Wu, W.; Chen, K.; Hong, S.; Lai, Y. A critical review of battery thermal performance and liquid based battery thermal management. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 182, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; He, W.; Pecht, M.; Tsui, K.L. State of charge estimation of lithium-ion batteries using the open-circuit voltage at various ambient temperatures. Appl. Energy 2014, 113, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, S.; Yan, T.; Liu, X. Hybrid Battery Thermal Management System in Electrical Vehicles: A Review. Energies 2020, 13, 6257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Rao, Z.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Xiong, R. Evaluating the performance of liquid immersing preheating system for Lithium-ion battery pack. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 190, 116811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Shi, S.; Tang, J.; Wu, H.; Yu, J. Experimental and analytical study on heat generation characteristics of a lithium-ion power battery. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 122, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisomi, M.K. Thermal Management of Lithium-Ion Batteries: A Comparative Study of Phase Change Materials and Air-Cooling Systems Equipped with Fins. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.10244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X. Design and Optimization of Air-Cooled Structure in Lithium-Ion Battery Pack. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Energy Systems and Power Engineering (EESPE), Shenyang, China, 17–19 March 2025; pp. 827–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, X.; Cen, P.Y.; Chen, Q.; Cordeiro, I.M.D.C.; Kong, L.; Lin, P.; Li, A. A Comparative Numerical Study of Lithium-Ion Batteries with Air-Cooling Systems towards Thermal Safety. Fire 2024, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yu, G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, R. Cooling performance of battery pack as affected by inlet position and inlet air velocity in electric vehicle. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2022, 39, 102382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; He, H.; Guo, H.; Ding, Y. Modeling for Lithium-Ion Battery used in Electric Vehicles. Procedia Eng. 2011, 15, 2869–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Shen, J.; Xu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Xu, X.; Long, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F. Performance analysis of hybrid thermal management system integrating air-cooling topology fin and phase change material for eVTOL aircraft battery. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 280, 128455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Fang, L.; Jiao, S.; Sun, J.; Xin, Z. Numerical Simulation of Immersed Liquid Cooling System for Lithium-Ion Battery Thermal Management System of New Energy Vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 7673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, J.; Yuan, J.; Duan, J.; Liang, C. Simulation and analysis of air cooling configurations for a lithium-ion battery pack. J. Energy Storage 2021, 35, 102270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wu, L.; Qiu, C.; Yang, J.; Yuan, X.; Cai, Y.; Shi, H. Experimental and numerical studies on lithium-ion battery heat generation behaviors. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 5064–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, W.; Chen, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, Q. Numerical study on tab dimension optimization of lithium-ion battery from the thermal safety perspective. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 142, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Akrami, M. Advanced Thermal Management of Cylindrical Lithium-Ion Battery Packs in Electric Vehicles: A Comparative CFD Study of Vertical, Horizontal, and Optimised Liquid Cooling Designs. Batteries 2024, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassiliadis, N.; Schneider, J.; Frank, A.; Wildfeuer, L.; Lin, X.; Jossen, A.; Lienkamp, M. Review of fast charging strategies for lithium-ion battery systems and their applicability for battery electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Battery Pack Number | Depth of Discharge (DOD) Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 24.71 ± 0.07 a | 28.21 ± 0.08 b | 31.12 ± 0.06 c | 34.97 ± 0.09 c | 45.62 ± 0.09 c |

| 2 | 24.64 ± 0.16 a | 27.67 ± 0.16 a | 30.08 ± 0.15 a | 33.53 ± 0.15 a | 42.92 ± 0.54 b |

| 3 | 24.63 ± 0.16 a | 27.78 ± 0.27 a | 30.40 ± 0.27 b | 34.05 ± 0.23 b | 41.51 ± 0.15 a |

| 4 | 24.60 ± 0.07 a | 29.66 ± 0.19 c | 34.02 ± 0.27 d | 38.82 ± 0.21 d | 46.67 ± 0.25 d |

| Battery Pack Number | Depth of Discharge (DOD) Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 | 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 24.81 ± 0.11 c | 26.91 ± 0.13 c | 27.35 ± 0.13 b | 28.34 ± 0.14 a | 35.14 ± 0.36 d |

| 2 | 24.10 ± 0.15 a | 26.01 ± 0.12 a | 26.74 ± 0.15 a | 27.79 ± 0.23 a | 32.44 ± 0.67 b |

| 3 | 24.76 ± 0.21 c | 26.39 ± 0.27 b | 26.71 ± 0.30 a | 27.75 ± 0.29 a | 30.82 ± 0.29 a |

| 4 | 24.58 ± 0.18 b | 27.25 ± 0.23 d | 27.88 ± 0.28 a | 29.13 ± 0.24 d | 32.11 ± 0.24 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pisitsungkakarn, S.S.-H.; Chankerd, S.; Chankerd, S.; Thomrungpiyathan, T.; Bilsalam, A. Thermal Performance Assessment of Lithium-Ion Battery Packs Under Air-Cooling Conditions. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120667

Pisitsungkakarn SS-H, Chankerd S, Chankerd S, Thomrungpiyathan T, Bilsalam A. Thermal Performance Assessment of Lithium-Ion Battery Packs Under Air-Cooling Conditions. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):667. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120667

Chicago/Turabian StylePisitsungkakarn, Sumol Sae-Heng, Supanut Chankerd, Supawit Chankerd, Thansita Thomrungpiyathan, and Anusak Bilsalam. 2025. "Thermal Performance Assessment of Lithium-Ion Battery Packs Under Air-Cooling Conditions" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120667

APA StylePisitsungkakarn, S. S.-H., Chankerd, S., Chankerd, S., Thomrungpiyathan, T., & Bilsalam, A. (2025). Thermal Performance Assessment of Lithium-Ion Battery Packs Under Air-Cooling Conditions. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 667. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120667