Abstract

In order to solve the problems of thermal management efficiency and temperature control accuracy in the passenger compartment of electric vehicles, the phase change thermal storage design concept and the model-free adaptive control method are applied to the thermal management temperature control system of the passenger compartment. Aiming at the characteristics of waste heat utilization of the whole vehicle and the preheating demand of the passenger compartment, an integrated vehicle thermal management model with a heat exchanger and storage function and an intelligent temperature control system scheme for the passenger compartment is designed. Aiming at the demand for adaptive control of the thermal management system of the passenger compartment of the whole vehicle, a composite strategy of PID control of compressor speed and model-free adaptive control of water pump speed are proposed, and the effect of the application of different control strategies under the demand for temperature control of the passenger compartment is compared and analyzed in simulation. The study shows that the phase change heat storage system and its model-free adaptive control in this paper are more stable, with smaller overshoot and high temperature regulation accuracy; the overshoot of PID control and fuzzy PID control is 14.17% and 8.58%, respectively, while the overshoot of model-free adaptive control is only 0.42%, which verifies the superiority of the designed thermal management system and the effectiveness of the control algorithm, and will effectively enhance the thermal comfort of the passenger compartment of electric vehicles.

1. Introduction

Against the backdrop of the global energy transition and the rapid development of electric vehicles, traditional passive thermal control technologies struggle to meet the dynamic demands of complex operating conditions; as a core element for enhancing energy efficiency and occupant comfort, thermal management technology for passenger compartments is accelerating its evolution toward adaptive, high-precision solutions [1]. Currently, China’s independent innovation capabilities in electric vehicle thermal management still require breakthroughs, particularly in key technological areas such as extreme environment adaptability and real-time simulation accuracy, where gaps remain compared to international advanced standards [2]. The thermal management system of the passenger compartment directly impacts its energy efficiency ratio and user experience, making it a crucial strategic direction for the development of electric vehicles.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in simulation technology, intelligent algorithms, and system integration for occupant compartment thermal management both domestically and internationally. Sun Gangguo et al. [3] utilized AMESim software to develop a comprehensive thermal management system model integrating the air conditioning and battery systems; they investigated the effects of parameters such as compressor speed and electronic expansion valve opening on cabin temperature. Luo Yong et al. [4] focused on extended-range electric vehicles, designing a passenger compartment heating system capable of utilizing multiple heat sources such as engine waste heat and electric drive system waste heat, and investigated and analyzed the total energy consumption of integrated multiheat source heating strategies under varying ambient temperatures. Dai Chunjiang et al. [5] proposed and evaluated a model predictive control (MPC) strategy optimized using the NSGA-II algorithm for thermal management in electric vehicles; the proposed MPC strategy effectively controlled both passenger compartment and battery temperatures, reducing fluctuations in both. Additionally, the MPC strategy significantly reduced the energy consumption of the thermal management system. Zhu Jie [6] conducted an in-depth analysis of the performance of electric vehicle electrothermal phase change energy storage systems within the context of new energy and low-carbon development; the study explored the system’s operating principles, methods for optimizing dynamic heat storage performance, material characteristics, and heat storage efficiency and stability. Angel [7] proposed an adaptive temperature control system based on fuzzy neural networks, by integrating occupant thermal comfort models with real-time environmental data; the study analyzed issues related to temperature control accuracy and response speed. Toyota Japan [8] has developed a virtual passenger compartment model based on digital twin technology; by adjusting simulation parameters in real time using sensor data, the company achieves rapid iterative optimization of its thermal management system. Li [9] proposed a method for predicting transient temperatures of critical heating elements within the passenger compartment, and this approach combines an equivalent thermal circuit model with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling to establish a rapid zero-dimensional integrating accurate three-dimensional optimization model; it also incorporates a correction method for the passenger compartment’s output temperature. Zhao et al. [10] analyzed the impact of varying urban conditions and passenger behavior on the performance of passenger compartment thermal management systems, proposing that a MISO algorithm can enhance the predictive capabilities of SVM. Vikram et al. [11] proposed a novel integrated thermal management system that combines the passenger compartment thermal management system with the battery thermal management system, simulating the energy efficiency of integrated thermal management in electric vehicles. Ma [12] introduced a novel method for the coordinated control of a vehicle thermal management system encompassing both the battery and passenger compartment, and the study analyzed the performance of different control strategies in terms of temperature fluctuations, energy consumption, and temperature control accuracy. Abdul Hai Alami [13] introduced the phase change materials (PCMs) into battery thermal management systems, and enables the implementation of phase change material-based cooling systems to achieve optimal cooling performance, thereby delivering the most favorable temperature distribution, and significant achievements have been made in battery life-cycle costs and operational safety.

Research indicates that model-free adaptive control (MFAC) is a data-driven control method, its controller design relies solely on input/output measurement data from the controlled object, requiring no structural or dynamic information about the object. Consequently, it eliminates the need for modeling processes, modeling dynamics, and theoretical assumptions regarding object dynamics. Furthermore, MFAC controller parameters adjust online based on real-time input/output data changes, endowing this control method with strong adaptive capabilities.

Based on this, the paper applies the MFAC method to the thermal management system of electric vehicles. Its novelty primarily lies in the following: the controller design employed is independent of the model parameters of the controlled object, enabling adaptive control under uncertain conditions. Simultaneously, fuzzy PID control is used for the compressor speed, while model-free adaptive control is applied to the water pump speed, achieving a synergistic combination of the advantages of both control modes.

To meet the demands for temperature control precision and thermal comfort in electric vehicle passenger compartments, it is necessary to develop novel thermal management efficiency solutions and intelligent cabin temperature control systems based on the vehicle’s overall thermal management architecture. This paper investigates thermal management control strategies and precise temperature regulation design for passenger compartments, aiming to provide design insights for enhancing the intelligence and efficiency of electric vehicle thermal management systems.

2. Intelligent Temperature Control System Solution for the Passenger Compartment

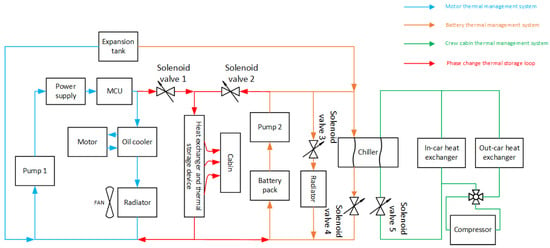

This paper designs a vehicle-mounted heat exchange and storage device based on phase change materials, integrated into the thermal management system. It fully utilizes residual heat from the motor and battery, enhancing the energy utilization efficiency and integration of the thermal management system. The passenger compartment thermal management system employs a heat pump air conditioning system for cooling and heating. The battery pack and motor circuit are connected via a phase change heat storage module, enabling the collection of residual heat from both circuits to provide heating for the passenger compartment. The integrated vehicle thermal management system architecture based on phase change heat storage is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Vehicle-integrated thermal management system architecture based on phase change heat storage.

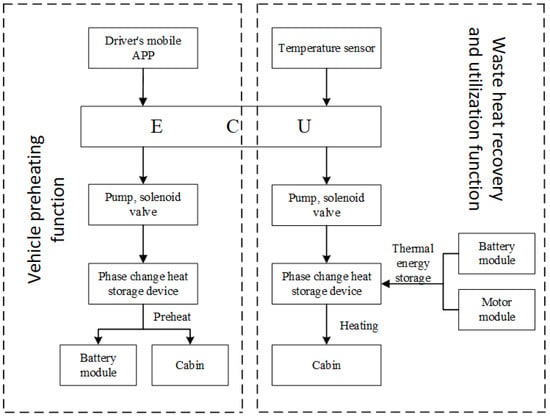

The intelligent cabin temperature control system and control solution for integrated vehicle thermal management systems is illustrated in Figure 2. This temperature control system integrates phase change heat storage with the vehicle’s overall thermal management system. The core modules within the integrated thermal management system architecture are described as follows:

Figure 2.

Intelligent temperature control system of passenger compartment with phase change heat storage.

- (1)

- Vehicle Preheating Function: Remotely sends signals to the vehicle based on driver preference to preheat the entire vehicle in advance;

- (2)

- Waste Heat Recovery Function: Collects temperature data from relevant batteries and motors;

- (3)

- Data Analysis Module (ECU): Analyzes collected temperature data to classify different operating modes;

- (4)

- Phase Change Heat Storage Module: Stores waste heat from batteries and motors, facilitating heat exchange with the cab;

- (5)

- Cab Control Module: Prioritizes the heat storage system to heat the cab based on preset temperature values.

When vehicle thermal management requirements or environmental conditions change, the vehicle system and control strategy depicted in Figure 1 and Figure 2 serve as the foundational platform. Utilizing the virtual simulation model and intelligent control algorithm proposed in this paper, the application effectiveness can be fully validated through simulation results.

To efficiently utilize residual heat from the motor and battery, this paper employs a phase change heat storage device and integrates it into the thermal management system solution for electric vehicles under study. After comprehensive evaluation, an inorganic hydrated salt phase change material—Na2SO4·10H2O—was selected for solid–liquid phase change energy storage. This material offers high latent heat (245 kJ/kg), excellent thermal conductivity, non-toxicity, and low cost. Research indicates the solid thermal conductivity of this phase change material is 0.5 (W/(m·°C)).

3. Simulation Design on Intelligent Refrigeration Temperature Control System for the Passenger Compartment

3.1. Simulation Model Development of Air Conditioning System for the Passenger Compartment

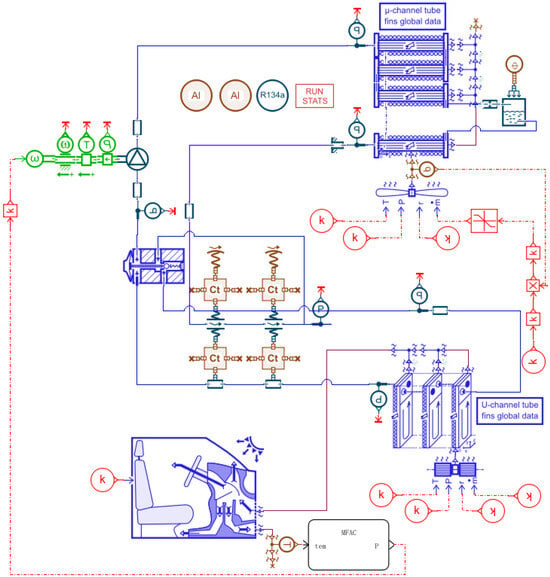

The operation of an automotive air conditioning system primarily consists of four processes: compression, heat dissipation, throttling, and heat absorption. Before establishing the passenger compartment air conditioning system simulation model, selection and matching calculations must first be performed. These calculations determined the summer and winter thermal loads for the vehicle’s passenger compartment to be 4050 W and 3370 W, respectively. To evaluate the cooling performance of the cab air conditioning system under various operating conditions, a simulation model of the passenger compartment air conditioning system was created in AMESim Version 2021.1 software, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Passenger compartment air conditioning system AMESim model diagram.

3.2. Adaptive Speed Controller Design for the Compressor

Due to the nonlinear nature of air conditioning systems, traditional PID controllers exhibit strong model dependency, often resulting in suboptimal control performance, and the conventional fuzzy PID control mitigates the reliance on precise modeling of the controlled object to some extent; its heavy dependence on expert knowledge significantly increases the cost of controller design. Model-free adaptive control (MFAC) is an online data-driven control method that achieves adaptive control of the controlled object through online adjustment of the designed control law. It does not rely on precise control models, requiring only input and output measurement data from the controlled object, and adaptive control is realized through online adjustment of the controller. The electric vehicle air conditioning system studied in this paper is a single-input–single-output discrete-time nonlinear system, represented by Equation (1):

In the equation, and represent the controlled system at time; and denote the system’s unknown order; is the system’s unknown nonlinear law function.

The system satisfies Equation (1) while also meeting the following two assumptions:

Assumption 1.

Except at finite time points, the partial derivatives of with respect to the variable are continuous.

Assumption 2.

Except at finite time points, the system satisfies the generalized Lipschitz condition, namely for any , , ≥ 0, ≥0 and , we obtain the following:

In the equation, = 1, 2; >0 is a constant.

Lemma 1.

If Assumptions 1 and 2 hold, when occurs, there must exist a time-varying parameter ∈R, referred to as a pseudo partial derivative (PPD), this enables the system to be converted into the following CFDL (Compact Form Dynamic Linearization) data model.

In the equation, represents the change in output between two adjacent time points; represents the change in input between two adjacent time points, and is bounded for any time point .

Based on Equation (3), the CFDL-MFAC controller is designed.

The following control input objective function is considered: Equation (4):

In the equation, > 0 is a weighting factor used to limit the variation in the control input; is the desired output signal.

Substituting Equation (3) and into Equation (4), differentiating with respect to , and setting it equal to zero yields the following control algorithm:

In the equation, ∈ (0, 1] is the step size factor, and is introduced to enhance the generality of the control algorithm. Since the system model is unknown, the partial derivatives must be estimated using the input–output data of the controlled system, as shown in Equation (6):

In the equation, > 0 is the weighting factor. Taking the limit of Equation (6) with respect to yields the estimated calculation for PPD as shown in Equation (7):

In the formula, ∈(0, 1] is the step size factor, which endows the algorithm with greater flexibility and generality; is the estimated value of .

In the formula, > 0 is a weighting factor used to limit the variation in control inputs, > 0 is a weighting factor, ∈ (0, 1] is a step size factor, designed to enhance the generality of the control algorithm, ∈ (0, 1] is the step size factor introduced which endows the algorithm with greater flexibility and generality, is a sufficiently small positive number, and is the initial value of .

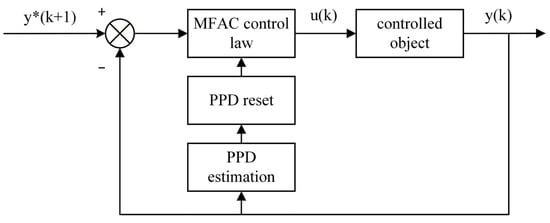

In summary, the CFDL-MFAC scheme is shown in Equations (8)–(10), while the flowchart of the model-free adaptive control scheme is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Model-free adaptive control system schematic diagram.

A joint simulation model of the passenger cabin air conditioning system was constructed using AMESim and MATLAB/SIMULINK software, with the MATLAB/SIMULINK version being R2021b. The simulation conducted comparative analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of PID control, fuzzy PID control, and model-free adaptive control (MFAC). The actual cabin temperature is transmitted to SIMULINK via the co-Sim co-simulation interface. The model-free adaptive controller built in SIMULINK outputs a compressor speed signal, which is fed back into AMESim to regulate the compressor speed.

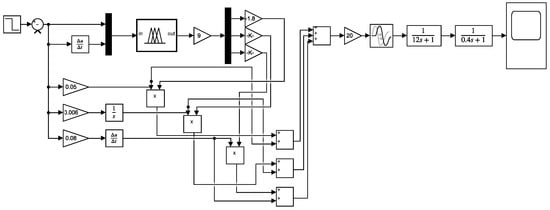

Additionally, fuzzy PID control offers outstanding robustness, effectively addressing issues such as time-varying systems and time delays. It overcomes the limitation of PID control where parameters cannot be adjusted in real time, and it significantly enhances steady-state accuracy and response speed. The fuzzy PID control simulation analysis model established in this paper is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The fuzzy PID control model.

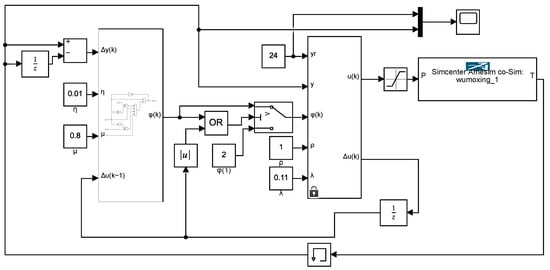

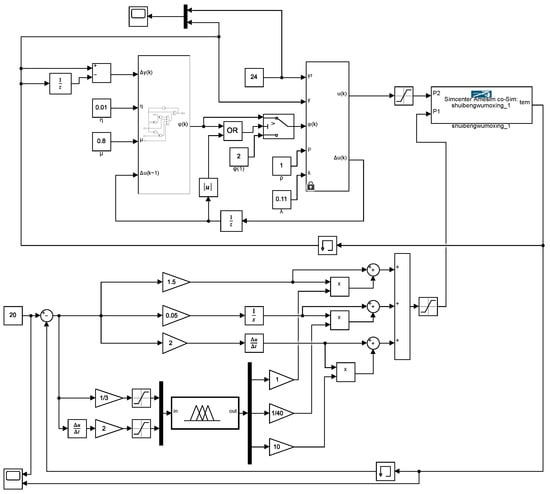

The model-free adaptive control simulation analysis model established in this paper is shown in Figure 6. The parameter selection of the model-free adaptive controller mainly depends on the dynamic linearization technique and the pseudo partial derivative (PPD) estimation. The PPD parameters are estimated online by the input and output data of the controlled system without the system model. In the closed-loop system, the variable tracking setting value is realized by adjusting the controller weight factor, the specific controller parameters are described in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Model-free adaptive control model.

Table 1.

The specific controller parameters for each controller.

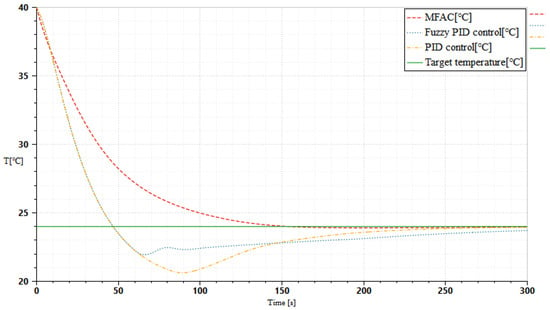

3.3. Simulation Comparison Analysis of Cabin Temperature Control

At the same driving speed, with an initial ambient temperature 40 °C and the passenger compartment air conditioning set to 24 °C, the cooling curves for the cockpit based on PID control, fuzzy PID control, and model-free adaptive control are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

The temperature change curve of passenger compartment under three different control modes.

As shown in Figure 7, the overshoot of PID control and fuzzy PID control is 14.17% and 8.58%, respectively, while the overshoot of model-free adaptive control is only 0.42%. The model-free adaptive control reaches the preset temperature in about 150 s, the PID control and the fuzzy PID control reach the preset temperature in 250 s and 300 s, respectively. Therefore, compared to the significant overshoot exhibited by PID control and fuzzy PID control, model-free adaptive control demonstrates greater stability with reduced overshoot. Additionally, the final temperature values for PID control and fuzzy PID control were approximately 23.95 °C and 23.70 °C, respectively, while the final temperature value for model-free adaptive control was approximately 23.96 °C. This control method exhibits a smaller control error and achieves the highest precision in regulating the passenger compartment temperature. Therefore, model-free adaptive control delivers superior performance in regulating compressor speed and air conditioning temperature, better meeting the thermal comfort requirements of electric vehicle passenger compartments.

4. Simulation Design on Intelligent Heating Temperature Control System for the Passenger Compartment

This study achieves effective utilization of residual heat from the motor and battery in the passenger compartment by regulating the pump speed within the heat exchange and storage circuit of the vehicle thermal management model. By establishing an AMESim simulation model linking the passenger compartment and heat exchange/storage module, the battery and motor are assigned mass and material properties to supply heat to the phase change heat storage device, thereby enabling more efficient and stable control of passenger compartment temperature.

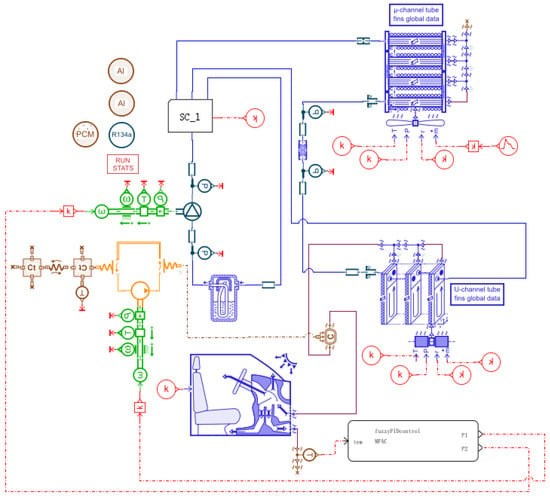

In this study, the pump speed of the heat exchange and storage circuit employs model-free adaptive control. To intuitively analyze the impact of model-free control on the pump speed of the heat exchange and storage circuit for cabin temperature regulation, the air conditioning compressor speed control continues to utilize fuzzy PID control. The AMESim physical simulation model of the passenger compartment air conditioning system and heat exchange/storage module is shown in Figure 8. Additionally, the integrated simulation model of the passenger compartment intelligent temperature control system, developed using AMESim and MATLAB/SIMULINK software, is depicted in Figure 9. As shown in Figure 9, the model incorporates both a fuzzy PID control module and a model-free adaptive control module. Through the co-simulation interface, it enables separate control of the air conditioner compressor speed and the pump speed within the heat exchange energy storage loop.

Figure 8.

AMESim model of passenger compartment air conditioning system.

Figure 9.

Intelligent heating temperature control system control model of passenger compartment.

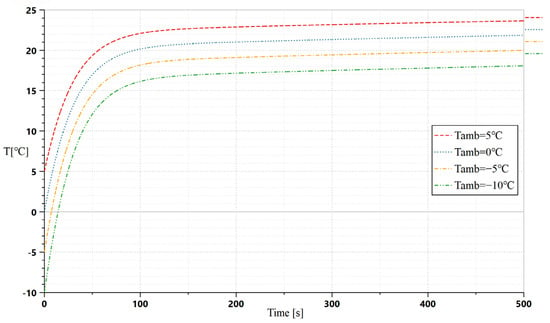

Simulation studies were conducted using a joint simulation model of the intelligent cabin temperature control system. The cabin air conditioning temperature was set to 20 °C, with a simulation duration of 500 s. Ambient temperatures in the simulated conditions were set to −10 °C, −5 °C, 0 °C, and 5 °C. The cabin temperature variations based on model-free adaptive control are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Heating temperature change diagram of passenger compartment under temperature control system.

As shown in Figure 10, the passenger compartment temperature rises from its initial value to a steady-state temperature following a similar pattern. Starting from ambient temperatures of −10 °C, −5 °C, 0 °C, and 5 °C, the temperatures reach steady-state values of 18 °C, 20 °C, 22 °C, and 24 °C, respectively. The higher the initial temperature, the higher the achievable steady-state temperature, enabling faster attainment of the preset value of 20 °C. Simultaneously, the intelligent heating temperature control system in the passenger compartment achieves minimal temperature fluctuation with a smooth temperature rise curve. This is attributed to the implementation of a model-free adaptive control scheme for the heat exchanger/storage circuit water pump speed, which enhances both the heating energy efficiency of the passenger compartment and occupant thermal comfort.

5. Conclusions

The efficiency of electric vehicle thermal management and the precision of temperature control are critical to human comfort. The integrated vehicle thermal management model and intelligent passenger compartment temperature control system solution designed in this paper, which combines heat exchanger and energy storage functions, offers significant advantages in passenger compartment thermal management system applications; the overshoot of PID control and fuzzy PID control is 14.17% and 8.58%, respectively, while the overshoot of model-free adaptive control is only 0.42%.

- (1)

- To address thermal management efficiency and temperature control precision in electric vehicle passenger compartments, an integrated vehicle thermal management model with heat exchange and storage capabilities was designed and developed alongside an intelligent passenger compartment temperature control system. This solution enables both vehicle residual heat recovery and preheating requirements for the passenger compartment.

- (2)

- To meet adaptive control requirements for the vehicle’s passenger compartment thermal management system, a composite strategy combining compressor speed PID control and model-free adaptive control for water pump speed was proposed. Simulation comparisons analyzed the effectiveness of different control strategies under passenger compartment temperature control demands. Results demonstrate that this control mode exhibits greater stability, reduced overshoot, and minimal control error, significantly improving passenger compartment temperature regulation precision.

- (3)

- The phase change heat storage system and its model-free adaptive control demonstrated outstanding performance in this study, validating the superiority of the designed thermal management system and the effectiveness of the control algorithm. This provides a comprehensive solution for enhancing the thermal management efficiency and occupant thermal comfort of electric vehicles.

Looking ahead, two development paths can be identified: (1) Model-free adaptive control-based thermal management, leveraging machine learning and reinforcement learning to enhance real-time control capabilities and better adapt to dynamic temperature demands in driving environments; (2) this paper has only explored relevant research at the theoretical level and through simulation modeling. The application advantages of fuzzy PID and model-free adaptive control in vehicle thermal management systems should be fully considered, with real-vehicle validation conducted to assess the reliability of their algorithms and control strategies.

6. Discussion

The core concept of adaptive control is to enable the controller to identify changes in the system’s dynamic characteristics in real time and automatically adjust its control strategy or parameters, thereby maintaining optimal or near-optimal performance under various operating conditions. Comparative analysis of several control system methods with model-free adaptive control (MFAC) are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of several control system methods with model-free adaptive control (MFAC).

Automotive thermal management control heavily relies on real-time data from sensors measuring temperature, pressure, and flow rate. If data distortion occurs due to interference or sensor failure, control strategies may make erroneous decisions, leading to severe safety issues such as thermal runaway and permanent component damage. Traditional control methods typically employ fixed parameters calibrated and optimized under specific laboratory conditions. When confronted with wide-ranging variations and severe fluctuations in external environments, controllers with fixed parameters can exhibit either “sluggish” or “overly aggressive” responses. The model-free adaptive control method proposed herein designs controllers solely based on input/output measurements of the controlled object. It requires no structural or dynamic information about the object, eliminating modeling processes and theoretical assumptions about object dynamics. The design accounts for model uncertainty and external disturbance boundaries, enabling controller parameters to automatically adapt to system dynamics while maintaining consistently superior control performance.

When confronted with sudden temperature changes or significant fluctuations, this research system can dynamically adjust driving strategies in real time based on external conditions and its own operational state. Key advantages include the following: (1) Rapid and stable response to abrupt changes and fluctuations, significantly reducing overshoot and oscillations. (2) Precise control ensures actuators operate only when most needed and at optimal power points, preventing energy waste. (3) Adaptation to gradual performance degradation, such as component aging and scaling, extends the system’s high-performance lifespan.

This study integrates phase change materials (PCMs) into the thermal management system of electric vehicles, forming a composite system of “PCM + active temperature control.” The PCM leverages its unique latent heat absorption/release properties to handle transient, short-duration high-power surges while ensuring temperature uniformity. The active cooling system is responsible for the long-term, stable dissipation of stored heat and system-generated heat into the external environment. This combination thus fully leverages the dual advantages of passive safety and active regulation. The impact of phase change thermal storage on the overall energy management (electricity/thermal energy) of electric vehicles is, on the whole, revolutionary and highly positive, representing the inevitable future direction for high-performance electric vehicle thermal management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Z. and X.D.; methodology, W.X.; software, W.X.; validation, Z.Z. and X.D.; investigation, Z.Z. and X.D.; data curation, W.X.; writing—original draft preparation, W.X.; writing—review and editing, X.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Yantai Science and Technology Innovation Development Program University-Local Integration Project under Grant 2023XDRH002.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Duzgun, M.; Ozarisoy, B.; Altan, H.; Moshaver, S. Analysis of Technological Systems for Improving Drivers’ Thermal Comfort. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e70128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Hou, B.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, R.; Li, S.; Li, X. A novel online prediction method for vehicle cabin temperature and passenger thermal sensation. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 245, 122853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.G.; Wei, M.S.; Zheng, S.Y.; Song, P.P. Simulation study on integrated thermal management of air conditioning and battery in pure electric vehicles. Refrig. Technol. 2022, 42, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, X.B.; Li, L.S.; Sun, Q. Design and simulation of a multi-heat source heating scheme for the passenger compartment of a supercharged electric vehicle. J. Chongqing Univ. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 38, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, C.J.; Lin, W.Y.; Li, S.Q.; Chen, X.; Song, W.J.; Feng, Z.P.; Kuznik, F. Development and performance of MPC strategy for electric vehicle thermal management system based on NSGA-II optimization. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2025, 14, 2200–2214. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J. Thermal performance analysis of electric vehicle electrothermal phase change energy storage system in the context of new low-carbon energy. Energy Storage Sci. Technol. 2024, 13, 4406–4408. [Google Scholar]

- Recalde, A.; Cajo, R.; Velasquez, W.; Alvarez-Alvarado, M.S. Machine learning and optimization in energy management systems for plug-In hybrid electric vehicles: A comprehensive review. Energies 2024, 17, 3059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyota Motor Corporation. Advanced Thermal Comfort System for All-Electric Vehicles. SAE Int. J. Altern. Powertrains 2025, 14, 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Xiao, H. Thermal management of electric vehicle power cabin based on fast zero-dimensional integrating accurate three-dimensional optimization model. Appl. Energy 2025, 378, 124783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, M.; Dan, D.; Xie, Y.; Zheng, S.; Zhang, Y. A data-driven performance analysis and prediction method for electric vehicle cabin thermal management system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 240, 122150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, S.; Vashisht, S.; Rakshit, D.; Wan, M.P. Performance analysis of integrated battery and cabin thermal management system in Electric Vehicles for discharge under drive cycle. J. Energy Storage 2025, 114, 115678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Liu, A.; Zhang, P.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Y. Collaborative thermal management of power battery and passenger cabin for energy efficiency optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 293, 117514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.H.; Maghrabie, H.M.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Sayed, E.T.; Yasser, Z.; Salameh, T.; Olabi, A.G. Potential applications of phase change materials for batteries’ thermal management systems in electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2022, 54, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).