Abstract

The complexity and interconnectivity of modern automotive systems are rapidly increasing, particularly with the rise of distributed and cooperative driving functions. These developments increase exposure to a range of disruptions, from technical failures to cyberattacks, and demand a shift towards resilience-by-design. This study addresses the early integration of resilience into the automotive design process by proposing a structured method for identifying gaps and eliciting resilience requirements. Building upon the concept of resilience scenarios, the approach extends traditional hazard and threat analyses as defined in ISO 26262, ISO 21448 and ISO/SAE 21434. Using a structured, graph-based modeling method, these scenarios enable the anticipation of functional degradation and its impact on driving scenarios. The methodology helps developers to specify resilience requirements at an early stage, enabling the integration of resilience properties throughout the system lifecycle. Its practical applicability is demonstrated through an example in the field of automotive cybersecurity. This study advances the field of resilience engineering by providing a concrete approach for operationalizing resilience within automotive systems engineering.

1. Introduction

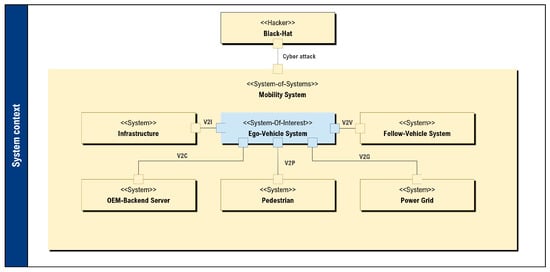

With the increasing degree of automation, vehicles are taking on more and more responsibility for the driving task. They have to interpret the traffic situation independently, make well-founded decisions and ensure the safety of both the occupants and other road users [1]. To fulfill these responsibilities, vehicles rely on high-performance computing and accurate environmental perception. Despite their capabilities, these systems reach their limits in reliably executing complex tasks such as autonomous driving. To overcome these limits, vehicles are expanding their range of information by communicating with external systems and form a large system of systems known as mobility systems. This type of data exchange is referred to as Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X) [2]. V2X technologies enable vehicles to exchange information like from other vehicles (V2V) [3], infrastructure (V2I) [4], cloud services (V2C) [5], the power grid (V2G) [3] and even pedestrians (V2P) [6]. This additional information enables the vehicle to create a more comprehensive representation of its surroundings and assess complex driving situations more precisely. Figure 1 shows the mobility system and the different types of communication. In such a mobility system, each subsystem retains a degree of operational independence, but contributes to an overall emergent behavior that is essential for coordinated and resilient driving.

Figure 1.

Extract from the mobility system based on Dibae et al. [7].

As an example, an intersection management system or cooperative driving functions can be implemented to significantly increase safety and efficiency in road traffic. Such functions that are tailored and implemented in different systems in the mobility system are called distributed cooperative driving functions [8,9]. However, this increasing connectivity and system complexity also brings with it new challenges. Since modern driving functions depend on the cooperation of multiple internal and external systems, even minor malfunctions can lead to critical consequences [10]. At the same time, the high level of connectivity represents a potential target for cyberattacks, which can compromise both the safety of individual vehicles and the trustworthiness of the entire mobility system. In this context, so-called black hats become an important component of the overall system analysis (see Figure 1). Therefore, they are also taken into account using methods such as attacker modeling [11,12].

To meet these challenges, important properties, such as resilience, must be considered and integrated into the system or functions already in the early stage of the development process. Resilience describes the ability of a system to maintain its intended functionalities despite internal errors or external disruptions or to recover quickly. In the context of autonomous driving, this characteristic is even more important, as there is no human driver available as a fallback level to directly take the control. In order for vehicles to be resilient during operation, appropriate resilience properties like disruption tolerance, availability or adaptability must be taken into account in the early phase of system design [13,14,15]. The basis for this are the system requirements, which explicitly define resilience as an integral part of the system or the function.

The resilience requirements must be identified at an early stage, documented and taken into account in the systems architecture design and throughout the remaining development process. This paper introduces a structured method for systematically deriving resilience requirements in the early concept phase of automotive system development. To support this method, the concept resilience scenario is introduced. This is based on the Resilience Graph (see Section 2.2). Based on the resilience scenarios, specific requirements can be defined to ensure that the vehicle remains functional even under disruptions. To demonstrate the practical applicability of the method, we illustrate it using a well-known case study from the field of cybersecurity in the automotive industry. By integrating resilience considerations into the concept phase, automotive systems can be better equipped to handle both foreseeable and unforeseen operational disruptions.

2. Background and Problem Statement

With the increasing number of component and interaction of vehicle systems, their development is becoming ever more complex. Since this complexity is unavoidable, it must be addressed and mastered with the help of new methods and approaches in engineering. Systems engineering offers a structured and methodical approach to overcoming this challenge [16]. In the automotive industry, this challenge is all the more pressing when you consider the number of interfaces that can arise both within the system and within and between companies (OEM, Tier 1, Tier 2, etc.). This has led to the development of a domain-specific discipline, Automotive Systems Engineering, tailored to the specific requirements and expectations of vehicle development.

A central framework for its implementation is the V-model, which depicts the main phases of system development. The left-hand side of the model describes the system design process, in which requirements are systematically transferred into a vehicle architecture [13,17]. The following section explains the challenges that vehicles encounter in dynamic environments and the role of resilience as a solution. It then shows how requirements management contributes to the integration of resilience properties as an enabler for resilience by design.

2.1. Challenges of the Highly Dynamic Vehicle Environment

A wide range of unpredictable events can occur in the highly dynamic environment of a vehicle in the mobility system. A vehicle must be able to deal with disruptions and unexpected events. These can be both external and internal in nature: (1) External influences like a wild animal suddenly jumping onto the road or an unexpected maneuver from another road user and (2) internal disruptions like failure of an essential vehicle component or a cyber attack on the system. To overcome these challenges, developers rely on scenario-based testing to identify as many realistic situations as possible during the development phase [18,19]. Simulations like in X-in-Loop and virtual tests can be used to check the behavior of the vehicle system under a variety of scenarios [18,19,20,21]. Nevertheless, it is impossible to foresee all potential situations in development before the testing in the real vehicle [22]. SOTIF HARA therefore deals with the identification and evaluation of unexpected events. However, this focuses strongly on safety aspects and primarily analyses hazards due to inadequate system performance, for example, due to faulty sensor perception or environmental influences [23].

2.2. Resilience as the Key to Dealing with Disruptions and Unforeseen Scenarios

As not all scenarios can be tested in advance, connected and autonomous vehicles must be able to handle disruptions and unforeseeable events in operation. This means that it must recognize disruptions, analyze them depending on the situation and take appropriate decisions. Integrated resilience properties in the systems design phase (Resilience-by-Design) give the connected and autonomous vehicles the capability to deal with unforeseen scenarios in operation (Resilience in Operation or Operational Resilience) [13]. Resilience, as defined in prior research, will be used in the context of this paper. According to our previous work [13], resilience is defined as follows:

Resilience describes the ability of a system to maintain its intended functionality and availability despite disruptive events.

The disruptive events are in the automotive resilience context cyber attacks, unexpected environmental changes, internal system failures, disrupted communication, incorrectly received messages. This definition illustrates the need to consider resilience as an integral part of the development phase of connected and automated vehicles. This definition also emphasizes the close interrelation between resilience, safety, and cybersecurity. This naturally underscores the statement that improvement measures recommended or implemented as part of safety or cybersecurity analysis also serve to improve resilience in the first instance. A more detailed examination can be carried out as part of a trade-off analysis to ensure, for example, that the measures are not contradictory, redundant or expensive. This lead to the establishment of a new domain: Automotive Resilience Engineering. To gain a better understanding of resilience, the concept is illustrated by the Resilience Graph in Figure 2.

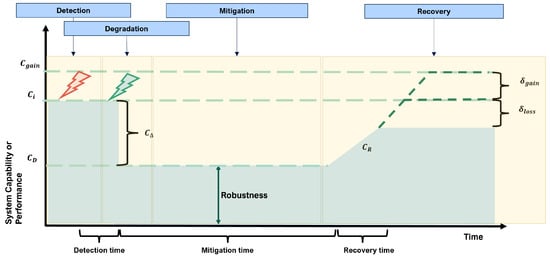

Figure 2.

Resilience Graph according to Bita et al. [13].

The Resilience Graph illustrates the time course of the system capability after the occurrence of a disruption. Given is a system with an implemented capability . A disruption may occur or be caused during runtime. This is shown in the graph as a red flash. At this point, the system recognizes the disruption—the so-called Detection phase begins. A resilient system continuously monitors capability and may be able to detect disruptions. After the disruptive event is detected (see green flash on Figure 2), a degradation procedure can be started. The system capability initially at drops to a level and a gap appears . In the subsequent mitigation phase, an attempt is made to stop the degradation and establish a stable state. After successful mitigation, the system can take three possible courses in the recovery phase: (1) The system capability is only partially restored, which leads to a final state below the initial level. The difference to corresponds to the loss of function . (2) The system returns to the original level , which corresponds to a complete recovery. (3) The system capability exceeds the original value—there is a function gain [13,24,25,26]. This graphical model thus serves as a reference framework for identifying resilience-relevant system behaviors and deriving technical resilience requirements accordingly.

2.3. Conceptual Distinctions: Resilience vs. Robustness

The terms resilience and robustness are often used interchangeably in engineering literature, yet they reflect fundamentally different system capabilities. Clarifying their distinction is crucial to position resilience-by-design as a complementary and necessary extension to traditional robustness.

The resilience graph shows the behavior of a resilient system. Robustness also plays a role in this context and can be seen in the graph. This relationship is also presented and examined in various literature from different fields of research. A precise understanding of the conceptual differences between robustness and resilience is essential in order to position resilience as an independent system property in the context of modern vehicle development. Robustness classically describes the ability of a system to maintain its performance under known, modeled, and limited disturbances, such as fluctuations in input signals, sensor noise, or deterministic component failures. It is usually achieved through static measures such as redundancy, tolerance to deviations, or fault tolerance. Bernardeschi et al. investigate robustness in the field of neural networks. In his work [27], robustness is defined as the ability of a neural network to maintain its classification performance under input perturbations. Bernardeschi et al. [27] use resilience as a property within the robustness analysis of a neural network, not as an independent resilience concept at the system level. The term resilience is sometimes used synonymously with adversarial robustness to describe resistance to targeted input manipulations. However, this usage remains at the component level and differs fundamentally from the concept of resilience used in this paper, which encompasses adaptive system responses, state changes, and recovery mechanisms [27].

Resilience, on the other hand, goes far beyond this aspect. It encompasses not only the ability to endure disruptions, but also their early detection, controlled degradation of the functional level, targeted mitigation of the effects, and the ability to recover after a disruptive event. These four phases are structurally represented in the Resilience Graph (see Figure 2) and show that resilience takes into account dynamic system responses and adaptation mechanisms. As Patriarca et al. [28] emphasize, resilience focuses in particular on unexpected, unmodelable events and their systemic consequences, including cascading failures in complex SoS (Systems of Systems) architectures. Hulse et al. [29] also differentiate between different levels of resilience, which are particularly essential in highly networked, dynamically changing environments such as the automotive V2X ecosystem. While robustness is often formalized in the form of hard limits (e.g., through worst-case analyses), resilience requires a context-specific and adaptive interpretation in order to be able to respond appropriately even in the face of uncertainty and incomplete system knowledge.

Robustness is a part of resilience, but primarily addresses resistance to predictable disturbances, while resilience additionally ensures responsiveness and adaptability under unpredictable, often safety-critical conditions. Both properties are necessary for highly automated vehicle systems, but should be clearly distinguished from each other conceptually and addressed specifically.

2.4. The Role of Requirements Engineering in Automotive Systems Development

Requirements are essential for creating the architecture and for the overall development of a system. Architecture frameworks such as TOGAF place requirements engineering at the heart of the framework. In requirements engineering, the objectives, functions, restrictions and also the properties that must be implemented in the system are defined. Magnus Ågren has analysed in his study [30] the impact of requirements on the development speed of a system in the automotive industry. The systematic elicitation of requirements therefore plays a crucial role in the development of complex vehicle systems. However, higher-level properties of systems, such as resilience, safety or security, cannot be specified directly in requirements engineering. For the elicitation requirements, extensive analysis are required.

In case of the automotive safety, a so called hazard analysis and risk assessment (HARA) is carried out in accordance with ISO 26262 (for the functional safety, also called FuSa [31]) and ISO 21448 (for the safety of the intended functionality, also called SOTIF [23]). These methods are used to define safety goals, which are then formulated as safety requirements. The Automotive Cybersecurity in the other hand conduct a so called Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment (TARA) in accordance with the ISO/SAE 21434 (for cybersecurity engineering [32]), from which cybersecurity goals are derived, which in turn are translated into specific cybersecurity requirements. Currently, there is no established method for systematically eliciting automotive resilience requirements. This raises the question of how these requirements can be defined and which methods are suitable for eliciting them.

2.5. Lack of Consideration of Resilience Goals and Requirements

In the context of automotive safety and security, a distinction is made between the terms goals and requirements. Goals, often referred to as system goals, are higher-level protection objectives that are defined during domain-specific analysis in order to minimise the risks of a system or function. In the automotive safety, these protection objectives are called to as safety goals and result from the safety analysis. While the FuSa HARA formulates safety goals against systematic and random failure, the SOTIF HARA focuses on system failure without technical defects, for example, due to insufficient perception or incorrect interpretation of the environment [23,31]. The concept is used also for the automotive cybersecurity. Here, the high-level protection goals are called cybersecurity goals or, more generally, security goals. These are derived from the TARA and define the protection goals against cyber attacks, which are intended to ensure that the system is not compromised by external threats. Systems requirements are then derived from these system goals. These requirements are more detailed and can already specify technical solutions or restrictions (constraints). While goals provide a general direction for system development, requirements specify how these goals are to be realised technically [32].

The same concept can be applied to automotive resilience engineering. The resilience goals define the high-level protection goals that ensure that the system or function remains available despite malfunctions and continues to fulfil its intended functionalities. These goals define the system’s ability to recognise faults (detection), to reduce performance in a controlled manner (degradation), to control and limit damage (mitigation), and to recover from a disruption (recovery). The resilience requirements derived from these resilience goals then specify concrete measures and technical solutions to ensure the resilience of the system in operation [13].

While safety and cybersecurity goals and requirements are systematically collected, there is no corresponding methodology for identifying resilience goals and requirements. This raises the central question of how resilience can be integrated as a system capability and which methods are suitable for eliciting resilience goals and requirements.

2.6. Elicitation of Resilience Requirements Through Resilience Scenarios

The concept of the resilience graph is used in this work as a basis for systematically identifying resilience requirements. The resilience graph is a structured representation of how a resilient system works. The focus of the model is to represent the behaviour when disturbances occur. Magnus Ågren also demonstrates in his study [30] that domain-specifics tools can positively affect the work practices and increase the development speed. Model-based requirements is considered in the study as one of the most important desire for working with requirements.

As already mentioned, resilience in the automotive sector is based on the principles of safety and cybersecurity. Close cooperation between these disciplines is therefore necessary. This paper presents a method for capturing resilience requirements by describing concrete scenarios. These scenarios are referred to as resilience scenarios. Since resilience is intended to ensure that the system and functions remains available and maintain the intended functionality, resilience scenarios focus on incidents—i.e., what happens if a disruption occurs. The resilience graph forms a solid basis for the systematic description of these scenarios. The findings derived from this serve as input for the elicitation of resilience requirements. Building on these conceptual foundations, the following section explores the current state of research and existing methods for eliciting resilience requirements in automotive systems design.

3. State of the Art and Related Work

This section examines the current state of the art in the field of requirements elicitation, scenario modeling and resilience engineering in the automotive context. First, methods for eliciting requirements were analyzed, followed by an examination of relevant work on hazard & damage scenarios, threat scenarios and resilience scenarios. Another central topic is the visualization of scenarios, as this has a significant influence on the elicitation and analysis of resilience requirements. Finally, methods for formulating requirements were considered.

3.1. Research Objectives

To systematically investigate the state of the art, the following research questions guide this study:

- RO1-

- What methods exist for eliciting requirements?

- RO2-

- What types of scenarios are relevant for the resilience analysis in the concept phase?

- RO3-

- How can resilience scenarios be visualized using information from existing analyses, such as safety and security?

- RO4-

- How can resilience requirements be formulated?

3.2. Requirements Elicitation Methods

A central contribution to requirements elicitation comes from Pohl in [33] who present various methods for the systematic elicitation of requirements. He identifies three main sources for requirements: Stakeholders, documents and existing systems in operation. The author divides requirements elicitation techniques into several groups, including survey techniques such as interviews and questionnaires, creativity techniques such as brainstorming and workshops, and document-centered methods such as system archaeology. Observation techniques such as field observation are also described, which make it possible to derive requirements directly from practice. One example of a document-centric method is system archaeology, in which requirements are determined by analyzing existing systems, source codes and logical structures. However, this method requires a high level of technical expertise and is time-consuming. Another frequently used technique is field observation, in which processes and workflows are analyzed on site in order to derive requirements directly from operations. This method is suitable for physically visible processes, but has limitations when analyzing purely digital processes. While Pohl [33] primarily consider scenarios in the context of model-based requirements documentation, Koch et al. [34] show how scenarios can be used specifically to specify security protocols. The authors demonstrate how scenarios can be used to define security requirements by combining a model-based and scenario-based approaches.

3.3. Relevant Scenario Types and Identification Methods

Scenarios play a central role in the validation and approval of vehicles, as they describe the functionality of a system under certain given conditions and defined scene [35]. In addition to describing the desired functionality of a system under optimal conditions, misuse cases are also considered as part of further analyses [18,19]. These focus on potential threats or malfunctions and are essential in order to identify and rectify functional insufficiencies at an early stage [22,36]. For the resilience, these types of scenarios are relevant: hazard and threat scenarios. Hazard scenarios or hazardous scenarios describe potentially dangerous situations and are considered in the context of ISO 26262 [31] and ISO 21448 [23]. Hazard scenarios are identified using methods such as FMEA, FTA, HAZOP or STPA, whereby the trigger condition plays an important role [17,23,31,37]. In the field of cybersecurity, threat scenarios are used, which are identified as part of a TARA analysis in accordance with ISO/SAE 21434 [32]. Threat scenarios describe situations in which an attacker exploits a vulnerability in the system in order to compromise the system [32,38,39]. In Japs et al. [40], the authors present the necessity of cooperation between safety and security in the automotive industry. In the paper, the author presents a method for identifying threats at the system level in the design phases. Several methods such as SAHARA [41], STPA-Sec [42], STPA-SafeSec [43], CHASSIS [44] or SAVE [40] can be used to combine safety and cybersecurity in the development phase [45].

3.4. Representation of Scenarios

Literature analysis reveals multiple forms of scenario representation. In addition to textual descriptions and visual modeling, for example, using UML or SysML diagrams, there are various formal methods such as the Scenario Description Language (SDL) or fault and attack trees. There are also table-based representations and graphic sketches that enable compact and intuitive visualization [20,39,40,46,47]. An established framework for structured scenario description in Automotive is the 6-layer model, which was developed as part of the Pegasus research project. This model divides scenarios into six thematic levels, ranging from the road and vehicle level, through the driver and object level, to the environmental and control level [20]. Subsequent research projects such as V&V-Methods have extended this model to cover urban environments [35]. In addition, there are two industry standards, OpenScenario and OpenDrive, which specialize in the static and dynamic modelling of traffic scenarios and are used for simulations [46].

At the same time, ISO 34501 [48] offers a standardized model for describing scenarios across four levels of abstraction, ranging from conceptual to concrete test implementation. Functional Scenario describes the intended behavior of the system in natural language and at a high level of abstraction, e.g., “A vehicle overtakes another on a country road.” This level is independent of concrete system parameters and serves to initially identify relevant situations. Abstract Scenario refines the functional scenario by clearly naming actors and elements and enabling structured descriptions. However, no concrete values or complete parameter ranges are specified at this stage. The aim is to pass on the scenario in a machine-readable and structured form. Logical scenario specifies the abstract scenario with concrete parameter ranges, value intervals, and conditions. Influencing factors such as speed, distance, weather conditions, etc., are quantified, but without specifying individual characteristics. Concrete Scenario represents a complete instantiation of a logical scenario with precisely defined values for all parameters. It is suitable for concrete tests and simulation-based validations [48,49].

In this paper, the resilience graph (see Figure 2) is used as an analysis tool to describe system behavior in fault situations. Its structure maps functional resilience scenarios. These describe how the system should respond in the event of a fault, but without technical detail parameters. Accordingly, the Resilience Graph can be clearly classified at the functional scenario level in accordance with ISO 34501.

3.5. Formulation of Requirements

Pohl describes a step-by-step procedure for formulating requirements that is based on five elements [33]: (1) Determination of legal requirements, (2) definition of the requirements core, (3) characterization of system activity, (4) integration of objects and (5) definition of logical and temporal conditions. This methodology serves as a basis for the structured and consistent formulation of requirements. In the area of resilience requirements, Brtis et al. [50] provides special resilience patterns that exist in three forms. They exist in natural language, structured data and model-based representations such as SysML or DoDAF. These methods enable the direct integration of resilience requirements into model-based development approaches [50]. A formalized way to express resilience requirements according to Britis et al. [50] is as follows:

The <system> encountering <adversity>, which imposes <stress> affecting delivery of <capability> during <scenario timeframe> and under <scenario constraints>, shall achieve <resilience target> for <resilience metric>.

3.6. Related Concept—Obstacle Analysis in Requirements Engineering

In the field of requirements engineering, there is a similar practice called obstacle analysis. This is a systematic method that deals with the identification, analysis and resolution of obstacles that stand in the way of stakeholders’ goals or requirements. Obstacles are defined here as possible undesirable conditions [51,52,53]. In comparison, the method developed here for resilience scenario-based requirements analysis pursues a domain-specific, extended approach that focuses on the design of resilient system architectures in an automotive context. The method developed in this paper uses concrete, identified scenarios from the areas of cybersecurity (TARA according to ISO/SAE 21434 [32]) and safety (HARA according to ISO 26262 [31] and ISO 21448 [23]) in order to create resilience scenarios based on them. These describe the desired way of dealing with disruptions, which in turn is formulated as resilience requirements. The proposed resilience scenario method can be understood as a resilience-specific extension of goal-oriented requirements engineering, particularly inspired by obstacle analysis. It places emphasis on system-specific disruptions and the integration of resilience into architectural design.

3.7. Contribution of This Work

The analysis of the state of the art shows that many existing approaches to requirements elicitation, scenario modeling and requirements formulation are isolated solutions that are not specifically geared towards resilience engineering. While there are established methods for automotive safety and cybersecurity, to the best of our knowledge, there is, to the best of our knowledge, no holistic and standardized method available for systematically eliciting resilience requirements in the early design phase of automotive systems. This work presents a systematic method for requirements elicitation that specifically addresses resilience in an automotive context. It follows a scenario-based approach that can be used in the early concept phase. The methodology is applied using a specific use case to demonstrate its suitability for practical use.

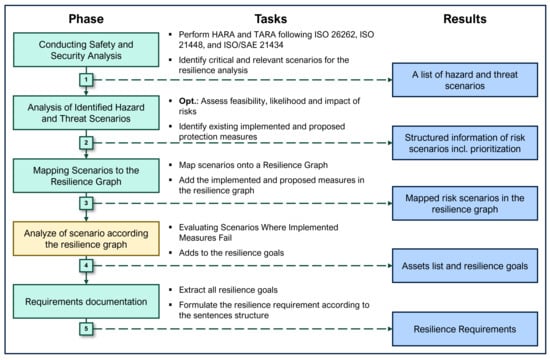

4. Method to Design Resilience Scenarios and Extract Resilience Requirements

This section introduces a method for systematically deriving resilience requirements in automotive systems through scenario-based analysis using the resilience graph framework. The method comprises five successive phases that are necessary to systematically identify resilience requirements. The proposed methodology for scenario-based resilience requirement elicitation can be described as follows:

- Perform domain-specific hazard and threat analysis (HARA, TARA)

- Extract relevant scenarios and map them into the Resilience Graph

- Analyze the scenario with respect to detection, degradation, mitigation, and recovery

- Derive resilience goals and document them

- Transform goals into structured resilience requirements (INCOSE template)

Figure 3 provides an overview of the entire method for deriving resilience requirements. The figure outlines each step of the method, including the associated tasks and expected outputs.

Figure 3.

Method for scenario-based requirement elicitation for automotive resilience [23,31,32].

The process begins with a domain-specific analysis in which safety-critical hazards and cyber threats are identified according to ISO/SAE 21434 [32]. Potential hazards and threats to the ego-vehicle as system-of-interest are identified. These identified scenarios are the basis for the subsequent analyses. The next step is to transfer the identified scenarios to the resilience graph. This systematically records and structures the events from the scenario analysis. If protective measures have already been implemented or corresponding control mechanisms are in place, these can also be entered into the graph to enable a holistic view. Once the scenarios have been integrated into the resilience graph, the actual resilience analysis follows. This involves analysing scenarios in which existing protective measures fail or are inadequate.

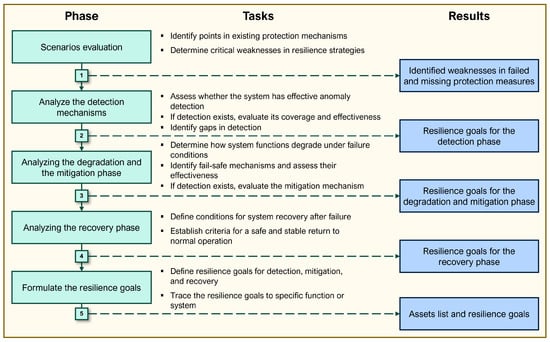

Figure 4 shows the systematic analysis approach used in this step. The aim is to identify weaknesses and potential for improvement in order to derive targeted resilience goals and measures. The resilience graph was selected because it enables a unified and intuitive representation of system behavior across all resilience phases (detection, degradation, mitigation, recovery). This makes it particularly suitable for linking resilience goals directly to requirements and for integrating safety and cybersecurity disruptions in a single framework. Based on this analysis, resilience goals are formulated to ensure that the system is resilient to internal and external disruptions.

Figure 4.

Details of the steps in the scenario analysis (4th step of Figure 3) according to the resilience graph.

In the final step of Figure 3, all identified resilience goals from Figure 4 are documented and systematically converted into requirements. For this purpose, the INCOSE requirements template is used, which ensures a consistent and structured formulation of the requirements [50]. The following listing shows the pseudocode of the overall method.

5. Case Study: Jeep Hacking Incident

As case study, we use the well-known Jeep hacking case in the field of automotive cybersecurity as an application example [11]. This incident played a key role in highlighting the relevance of cybersecurity in modern connected vehicles. In this case, researchers Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek demonstrated how hackers can gain remote access via the infotainment system of a networked vehicle. The vulnerability lay in the Uconnect infotainment system, which was connected to the internet and allowed unauthenticated remote access. Using open mobile phone connections, the researchers were able to hack into the system and take complete control of the vehicle, including steering, brakes and engine control [11].

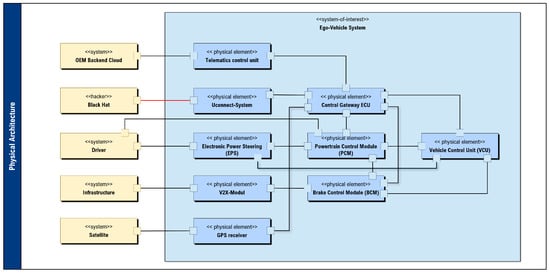

In this work, physical architecture is used to map the concrete technical implementation and physical distribution of the system components within the ego vehicle system under consideration. This representation is particularly important for the case study on the Jeep hacking incident. Based on publicly available information from the technical white paper [11] by Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek, the relevant aspects of the physical system architecture of the affected vehicle were modeled. The physical architecture in Figure 5 shown forms the essential technical context for further analysis. In practice, the system architecture is created as part of the system architecture design. This can then be handed over to the domain experts for further analysis. Each domain examines the architecture with a specific focus, such as cybersecurity, safety, or resilience. At the heart of the architecture is the Uconnect system, a telematics and infotainment system that communicates with the outside world via a mobile phone connection and can therefore represent the entry point for an attack. The Uconnect system is connected internally to the Central Gateway ECU (CGW) via the so-called infotainment CAN bus. The CGW acts as the central link between various internal networks in the vehicle—in particular between the infotainment area and safety-critical areas such as the powertrain and chassis [11].

Figure 5.

Example of an physical architecture of a connected vehicle system with the interaction in the mobility system.

5.1. Phase 1: Conducting Safety and Cybersecurity Analysis

In the first phase of the methodology, a domain-specific analysis is performed, which serves as the basis for deriving resilience requirements. Methods from established disciplines such as functional safety (e.g., HARA according to ISO 26262 [31]) and cybersecurity (e.g., TARA according to ISO/SAE 21434 [32]) are used. These analyses can also be performed using cross-domain methods such as SAHARA or STPA-Sec. The aim is to systematically record known sources of risk so that they can then be further examined from a resilience perspective. The results of these analyses – in particular, identified threat and hazard scenarios – thus form the decisive basis for the subsequent resilience assessment. This case study focuses on cybersecurity, as the Jeep hack analyzed was a clearly documented cyberattack. Accordingly, a TARA was performed in accordance with ISO/SAE 21434 [32]. This is typically carried out by experts in the field of cybersecurity engineering, in this case based on publicly available information from the report by Miller and Valasek. The methodology focuses on the essential steps: identification of assets, derivation of possible damage scenarios, and formulation of concrete threat scenarios.

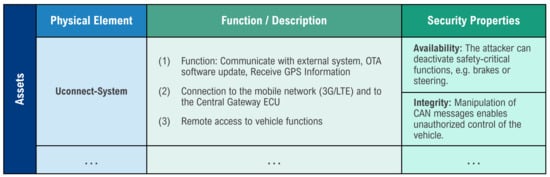

First, the so-called assets must be identified. One key asset identified is the Uconnect system. It plays a central role in the architecture as a communication interface between the vehicle and external systems, such as the OEM backend cloud or satellite services. The system’s functions include over-the-air (OTA) updates, GPS information processing, and connection to the mobile network (3G/LTE). Critical here is the bidirectional connection to the central gateway ECU, through which potentially safety-critical control units such as EPS (Electronic Power Steering), PCM (Powertrain Control Module), and BCM (Brake Control Module) can be accessed. It was precisely this connectivity that was exploited in the documented attack. Figure 6 shows the identified assets along with their associated cybersecurity properties that need to be protected.

Figure 6.

Assets with the corresponding cybersecurity property.

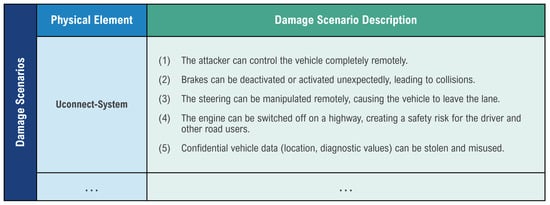

Based on this asset analysis, various damage scenarios were derived in the next step. These illustrate the safety-critical consequences that could occur if the Uconnect system were compromised. These include complete remote control of the vehicle, uncontrolled shutdown of the engine while driving, or deactivation of safety-related systems such as steering and brakes. The breach of confidentiality through the theft of sensitive vehicle data was also taken into account. Figure 7 shows the derived damage scenarios.

Figure 7.

Derived damage scenario from the assets.

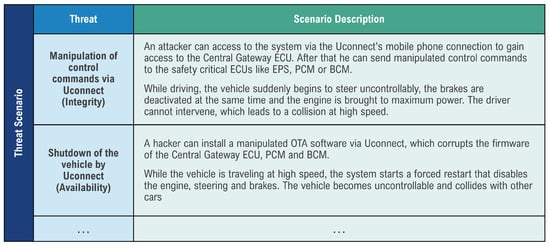

Based on the identified damage scenario, two specific threat scenarios were modeled: (1) The manipulation of control commands via the Uconnect system, which constitutes a breach of integrity, and (2) the complete shutdown of the vehicle by a compromised OTA update, which jeopardizes availability. Both scenarios illustrate how security-related functions can be specifically disabled via a central communication module. Figure 8 shows the threat scenarios derived.

Figure 8.

Derived threat scenarios from the damage scenarios.

The focus of this phase is therefore not only on the structured collection and assessment of risks, but also on the selection of scenarios that are particularly relevant for resilience analysis—especially where existing protective measures may fail or be insufficient. The results of this phase—a prioritized list of relevant threat scenarios—are then transferred to the Resilience Graph in order to identify specific vulnerabilities and derive resilience goals.

5.2. Phase 2: Analysis of Identified Hazard and Threat Scenarios

In this phase, the actual resilience analysis begins based on the previously identified scenarios from the cybersecurity domain. The focus is on gaining a detailed understanding of the selected threat scenario. In this case, the scenario involving the manipulation of control commands via the Uconnect system, which was already identified in the TARA (see Figure 8), is analyzed as an example. First, all relevant information about the scenario is extracted from TARA, in particular the description of the threat, the specific actions in the scenario, and their impact on the overall system. The aim is to reconstruct the sequence of events in the scenario over time so that it can later be mapped onto the resilience graph. In addition, it is checked whether protective measures have already been implemented or recommended. This information can come from the risk treatment step of TARA, for example.

Domain-specific evaluation parameters can be used to prioritize scenarios for resilience analysis. In the case of cybersecurity, this prioritization is based on the risk value as defined in the TARA according to ISO/SAE 21434 [32]. The risk value is derived from a combination of the attack feasibility rating, which describes how realistic an attack on a specific component or function is and how much effort it would require, and the impact, which assesses the potential consequences of a successful attack on the system. ISO/SAE 21434 [32] provides an assessment matrix for this purpose, which enables a consistent and comprehensible classification of risks. In practice, several threat scenarios can be identified as part of the cybersecurity analysis. For further resilience analysis, preference is given to those scenarios with the highest risk value, as they represent the greatest potential threat to system availability, integrity, or security.

While classic security analyses such as TARA focus on preventing attacks, resilience analysis goes one step further. It also considers situations in which protective measures fail or are circumvented—in other words, what happens when an attack is actually successful. This line of thinking is at the heart of this step. For example, it analyzes what happens when an attacker successfully gains access to the system, manipulates control commands, and thereby causes an accident. The result of this phase is a structured collection of relevant information on the scenarios under consideration, which now serves as the basis for transfer to the Resilience Graph.

5.3. Phase 3: Mapping Scenarios to the Resilience Graph

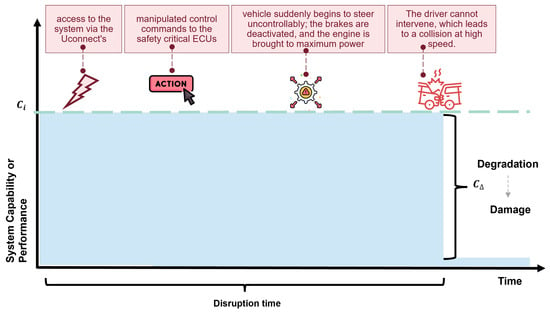

Mapping the identified scenarios onto the resilience graph is a key step in the resilience analysis. In this step, the previously structured information from the security and threat analysis is transferred to the graph in its entirety and in the correct chronological order. The aim is to clearly illustrate the causal relationships between threats, system responses, and potential damage. A key focus is on the chronological presentation of the scenarios. It must be clearly recognizable when the threat begins, what actions it triggers in the system, how system performance changes, and at what point a functional impairment or damage occurs. The resilience graph serves as a visual aid to map the course of the disruption over time. The disruption phase extends from the initial intrusion into the system to the occurrence of damage. Figure 9 shows an example of how the important information from the threat scenario (Figure 8) is mapped onto the resilience graph.

Figure 9.

Mapping of the important scenario information into the resilience graphs.

Using the case study as an example, the relevant threat scenario, namely the manipulation of control commands via the Uconnect system, was transferred to the graph. The corresponding information comes from the threat scenario and the damage scenario. The figure shows that the attack begins with access via the Uconnect system’s mobile connection. The attacker then sends manipulated control commands to safety-critical control units such as the VCU, PCM, or BCM. This causes the vehicle to suddenly steer uncontrollably, the brakes to be deactivated, and the engine to be brought to maximum power. Ultimately, the driver is no longer able to intervene, resulting in a high-speed accident.

In addition, existing or recommended protective measures are also taken into account in this step, provided that they have been documented in the cybersecurity analysis, particularly in the risk treatment step of TARA. These measures are entered in the resilience graph in order to evaluate their temporal effect and contribution to the detection, mitigation, or prevention of the disruption. The result of this step is a fully mapped scenario within the Resilience Graph, which forms an important basis for the subsequent derivation of concrete resilience goals.

5.4. Phase 4: Analysis of Scenario According to the Resilience Graph

In this step, the scenarios are analyzed in detail with regard to resilience. Filling the resilience graph as completely and precisely as possible in the previous step facilitate the resilience analysis, as gaps and weaknesses can become apparent at first look. The analysis can be carried out both through visual identification of problems and through a systematic approach. To ensure a structured investigation, a five-step analysis approach is used that takes various aspects of resilience into account.

5.4.1. Scenario Evaluation

The first step is to evaluate the identified threat scenario. In the case under investigation, this involves the manipulation of control commands via the Uconnect system. The report by Miller and Vala-sek shows that the attack is carried out via a vulnerability in the Uconnect system’s mobile access, enabling an attacker to send unauthorized commands to safety-critical control devices (e.g., VCU, PCM, BCM). The analysis examines whether protective measures were in place for this. According to the report, at the time of the analysis, there was no effective authentication or anomaly detection on the cellular interface, which represents a significant security gap. Both technical and organizational protective measures to prevent the attack were lacking, which was documented as a vulnerability in the security target system.

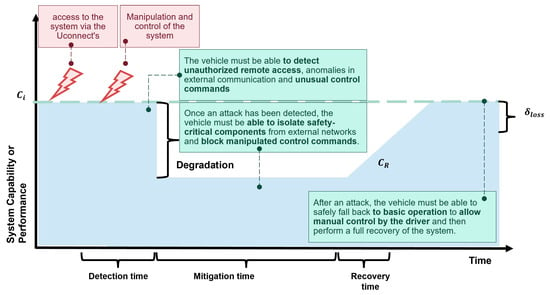

5.4.2. Analyze the Detection Mechanisms

A key goal of resilience is not only to protect systems against attacks, but also to ensure that they detect them when they do occur. According to the report, the vehicle was unable to detect the attack, indicating a lack of detection mechanisms. In Figure 10, a resilience goal was included on the resilience graph stating that the vehicle must be able to detect unauthorized remote access and unusual control commands. This can be achieved, for example, through anomaly detection methods at the communication or behavioral level. The resilience analysis shows that such detection did not exist in the present case, which allowed the attack to proceed unhindered. Accordingly, a resilience goal is derived: “The vehicle must be able to detect unauthorized access and unusual control commands.”.

Figure 10.

Mapping of the threat scenario into the resilience graph incl. resilience goals.

5.4.3. Analyze the Degradation and Mitigation Phase

The next methodological step consists of analyzing the degradation and mitigation phase. A resilient system design assumes that disruptions cannot always be completely prevented. This concept extends the classical principle of fault tolerance by explicitly considering not only internal system faults, but also external influences, unforeseen system failures, and targeted attacks such as cyber intrusions [13,14]. Instead, the system must be able to reduce its functionality to a safe level after detecting a disruption in order to avoid dangerous conditions. This principle is referred to in the literature as graceful degradation [29]. In contrast to pure fault tolerance, the aim here is to actively switch to a controlled operating state. In the context of the presented case study, the disruption originates from a successful cyberattack via the Uconnect system, which allows manipulated control commands to be injected into safety critical ECUs.

It is important to note that, in the context of resilience, the degradation phase can only be initiated after the fault has been successfully detected. In the present case study, based on the technical report [11], this did not happen: the attack was not detected, which is why no degradation mechanisms were activated. According to the report, there was no architecture or logic in the vehicle that allowed certain components to be isolated or transferred to a safe state in the event of an attack. Accordingly, no graceful degradation could take place. The system remained compromised until it was completely overtaken.

To counteract this, targeted degradation strategies would have been necessary. For example, if unusual communication patterns were detected via the Uconnect system, the module could be immediately disconnected from safety-critical components. This corresponds to a fail-safe approach, as also used in functional safety in accordance with ISO 26262 [31]. However, since complete shutdowns (e.g., of CAN communication) could impair safety-critical functions, degradation must be carefully measured and priority-controlled. This highlights the need for a graduated degradation concept.

The paper by Hulse et al. [29] describes degradation modeling as a strategic means of increasing resilience as early as the design phase. It identifies so-called fragile operating conditions—i.e., system states in which even minor disturbances can have serious consequences. It is precisely these states that need to be safeguarded by means of suitable degradation paths. In a figurative sense, the case study could, for example, provide for a fallback to a basic safe mode that disconnects all external communication channels, puts safety-critical control units into redundant operating modes, and leaves manual control to the driver.

The aim of this analysis is to define resilience targets for the degradation and mitigation phases. The degradation analysis considers how much system performance may decline before a critical point is reached that requires recovery measures. In the literature, the term degradation factor is used for this purpose [14,21]. Mitigation, on the other hand, comprises measures that prevent the spread of a fault or attack in the system and limit the impact on other components [54]. These measures are intended to ensure that the system continues to maintain a minimum range of functions even in the event of a disruption, rather than failing completely [55].

In the resilience analysis of this case study, the goal is to detect communication in the event of an attack, isolate security-critical components, and limit control access to the bare minimum—as shown in Figure 10.

5.4.4. Analyze the Recovery Phase

Once the disruption has been identified and contained, the recovery phase begins, during which the system is gradually restored to a functional state. The aim is not only to restore the original performance, but also to ensure that the system remains stable after the attack and does not slip back into a critical state [55]. An uncontrolled or hasty return to normal function can itself create new risks, which is why recovery must be carefully planned and carried out step by step [13]. For effective recovery, the prerequisites for starting the recovery process must first be defined. In the context of the case study, this means that recovery can only begin once the attack has been successfully isolated. The Uconnect system and other affected systems must report that no further attacks are taking place. This can be performed by digitally verifying the firmware signature, checking communication patterns, or cross-checking with backup components.

In the context of resilience, the term recovery path is used. A possible recovery path in this scenario could look as follows: First the system allows the transition to safe basic operation. The vehicle reduces its functions to a minimum, allows only local control by the driver, deactivates all external communication interfaces, and limits the vehicle speed. This allows the driver to bring the vehicle to a controlled stop. Before a complete recovery, security-critical components must be checked for compromise. Only when the system confirms that no further threats are present can the full range of functions be gradually restored. This can be performed, for example, by re-enabling communication interfaces one after the other and checking their integrity. The resilience goals defined in this phase must therefore not only include the restoration of functionality, but also criteria for stabilizing the system after recovery. This phased recovery protects the system from renewed instability, such as that which could arise from an attack that has not been completely neutralized or from residual errors in the control units. The resilience goals to be defined in this phase therefore include not only the restoration of functionality, but also stabilization measures that ensure a safe transition from the degraded state to normal operation—as shown in Figure 10.

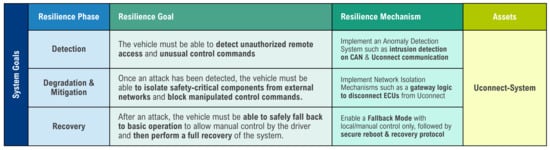

5.4.5. Formulate the Resilience Goals

The final step in this phase consists of structured and systematic documentation of the resilience goals. This involves consolidating all previously identified goals from the areas of detection, degradation & mitigation, and recovery, and assigning them to specific functions or system components. Appropriate resilience mechanisms that can contribute to achieving the documented resilience goals are also identified. These mechanisms represent the bridge between the analysis phase and the subsequent technical implementation. For example, to achieve the detection goal, the implementation of an anomaly detection system that recognizes unusual control commands or unauthorized access attempts may be proposed. Figure 11 clearly summarizes the formulated resilience goals for each resilience phase and presents the associated mechanisms. This table can be used later as a basis for deriving technical requirements or for trade-off analyses between security, availability, and performance. The consolidated presentation makes it possible to identify potential gaps at an early stage and address them in a targeted manner. In addition, this structured approach promotes the traceability of scenarios for resilience requirements and thus strengthens the traceability in the development process of safety-critical systems.

Figure 11.

Resilience Goals and Mechanisms for the Uconnect-System.

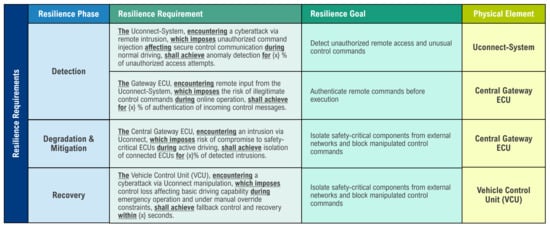

5.5. Phase 5: Requirements Documentation

In the final phase, the previously defined resilience goals are systematically converted into formal, verifiable requirements. The INCOSE sentence template is used to ensure consistent, clear, and comprehensible documentation of the requirements. The template provides a structured way of presenting relevant influencing factors such as the affected system, the type of disruption, the affected functional area, and the desired resilience goal in a uniform format. The requirements are documented in a requirements management tool to ensure traceability and version control. Figure 12 shows the list of resilience requirements for the system derived from the resilience goals.

Figure 12.

Resilience Requirements for the Jeep Hacking Use Case.

For the use case under consideration, the identified resilience goals were translated into specific requirements. Each requirement is specifically assigned to an element of the physical system architecture, such as the Uconnect system, the gateway ECU, or the vehicle control unit (VCU). This ensures that technical measures to increase resilience are directly embedded in the system design.

For example, the Uconnect system must be able to detect anomalies and unauthorized remote access in order to provide early warning of cyber attacks. The gateway ECU, in turn, should isolate safety-critical control units from the external network when attacks are detected. The VCU must ensure that, in the event of a successful attack, an immediate fallback level is activated, allowing the driver to take manual control of the vehicle, followed by a secure recovery of the entire system.

This completes the resilience analysis cycle. The documented requirements are specifically assigned to the relevant system components so that appropriate technical measures can be implemented and the system architecture adapted in the next iteration step. On this basis, established domain-specific analysis methods such as TARA for cybersecurity, HARA for functional safety, and the resilience methodology presented in this paper can be applied again. This iterative process achieves continuous improvement in system resilience—from identification and formulation to implementation and verification of specific requirements.

6. Discussion and Limitations

The presented method provides a structured approach to derive resilience goals and requirements based on resilience scenarios in the context of automotive systems engineering. By integrating established domain-specific analysis methods from automotive safety and cybersecurity, the method ensures a comprehensive consideration of resilience aspects. The application of the method to the well-known case study by Miller and Valasek demonstrates its practical applicability and effectiveness in identifying resilience goals.

However, several aspects need to be discussed in more detail to understand the strengths and limitations of the method. The following section explains some open questions that arose in the course of the work and discusses the methodology. Since the methodology presented in this paper is part of a larger research project, this paper is placed in that context.

6.1. Resilience-by-Design in Automotive

In automotive systems engineering, the isolated consideration of resilience alongside established domains such as functional safety and, more recently, cybersecurity engineering represents a paradigm shift. It is therefore important that processes, methods, and tools are developed specifically with a focus on resilience. This serves to provide engineers with the tools they need to integrate resilience characteristics at an early stage of system development. However, there are already established domains in system development. These must be taken into account in order to create synergy in development. This synergy can be observed, for example, in the approach. Resilience analysis is performed with the help of the system architecture that comes from the Systems Architecture Design & Definition Process. Furthermore, resilience analysis builds on the results of cybersecurity and safety analysis. This creates strong collaboration between the three domains.

Requirements play a central role in system development, as they are used to implement the specific technical solution. Requirements can be used to describe the most important characteristics of the system. For this reason, a method has been developed to describe resilience characteristics in the form of requirements. Modern standards increasingly demand robust systems that are prepared for failures, attacks, or unpredictable situations. Resilience requirements explicitly and systematically meet these demands. In complex and networked systems (such as networked vehicles or autonomous systems), it is unrealistic to foresee all disruptions. Resilience requirements make it possible to design the system to be adaptable and robust.

6.2. Scalability of the Method

This paper presents a method for deriving resilience requirements. These were developed based on a case study—the well-known Jeep hacking case. The method presented can be used for both simple embedded systems and complex systems such as a vehicle. As can be seen in Section 5, the method depends on the number of identified scenarios. However, these can increase exponentially during development, particularly in the areas of functional safety and cybersecurity engineering. It is important to take a pragmatic approach and prioritize strongly. Prioritization can be carried out using the risk factor, for example. This could be used to analyze the scenarios with the highest value first. The analysis also depends on the so-called target of evaluation. This determines which section or parts of the system are analyzed. Here, too, the more complex the system, the greater the effort required for the analysis. The analysis can be performed at different levels of abstraction. In this way, system engineers can first understand the big picture and derive the high-level requirements, then take a closer look at specific subsystems or interfaces as needed.

6.3. Trade-Offs and Goal Conflicts

In system designs, it is crucial to recognize that resilience goals cannot be viewed in isolation. As a rule, they interact or even conflict with goals from other domains such as safety and security. Safety goals and security goals are determined within the framework of HARA and TARA. In resilience by design, one of the activities is to systematically identify and resolve these conflicts. Therefore, the methodology checks whether security measures have already been implemented and, at the same time, safety measures must also be entered in the resilience graph. A typical example is the conflict of objectives between resilience and security. While resilience aims to maintain system operation as far as possible even in a disturbed state, security may require immediate shutdown to limit damage or stop attacks. However, this work focuses on the derivation and specification of resilience requirements in the early concept phase. An in-depth methodological consideration of systematic trade-off analysis and the handling of competing goals is identified as an important topic for future research.

6.4. Qualitative and Quantitative Resilience Metrics

Metrics play an essential role in analysis and evaluation in the context of resilience. In this context, resilience can be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively. In the context of this work, qualitative assessment was used. This is suitable for describing system behavior in the event of a disruption and is particularly suitable in the early development phase, as the analysis is performed with the aid of the system architecture. Quantitative metrics can be used in a later phase of system development. This involves defining specific values and parameters such as detection latency, degradation factor, or recovery time. This plays a role particularly in connection with simulation. However, the development and investigation of metrics are not within the scope of this work.

6.5. Model-Based System Architecture Design and Analysis in Resilience-by-Design

With the increasing complexity of modern vehicle systems, MBSE is becoming increasingly important, especially in the development and analysis of system architecture. This case study demonstrated a consistent chain of reasoning from domain-specific system analysis to the derivation of resilience goals. With a growing number of components, scenarios, and interactions, such a process is hardly scalable without model-based approaches and is difficult to implement in a comprehensible manner.

The model-based system architecture thus represents a central building block for the practical implementation of the resilience-by-design paradigm. It not only enables the structured representation of complex relationships, but also traceability throughout the entire analysis and development artifacts. This is particularly relevant with regard to the subsequent traceability and argumentation of resilience properties in the context of homologation processes.

The systematic linking of these elements in a consistent model not only supports the quality and consistency of the architecture, but also creates the basis for automated analysis, validation, and verification of resilient systems. A stronger focus on model-based approaches will be explored in greater depth in future work. Modern MBSE tools will be used in a targeted manner to ensure end-to-end tool support for the development of resilient vehicle systems.

7. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents a structured method for deriving resilience goals and requirements based on resilience scenarios in the context of automotive systems engineering. The method is based on established domain-specific analysis methods from automotive safety and cybersecurity and extends them with a specific focus on resilience. The scenarios obtained from the safety and cybersecurity analysis serve as inputs and are further refined for the resilience assessment. To validate the method, it was applied using a well-known case study from automotive cybersecurity by Miller and Valasek. The results show that the method presented can be used to systematically consider and integrate resilience properties in the early development phase. This helps to specifically improve the resilience of vehicle systems and ensure the design of a resilient system architecture. This work thus provides an initial approach for a resilience-by-design concept and lays the foundation for the establishment of resilience engineering as an independent discipline in automotive development.

Nevertheless, there are still open questions that should be investigated in future work. One of the key challenges is that resilience takes a system-wide perspective and ensures that the system remains functional and available even in the event of disruptions. When formulating resilience goals, both safety and cybersecurity goals must therefore be taken into account, which may be contradictory. This requires a targeted trade-off analysis to identify and resolve potential conflicts of objectives between these areas. A methodology for the systematic implementation of this trade-off analysis must therefore be further developed. To complement the qualitative analysis presented in this study, future research should aim to develop a quantitative assessment. For example, resilience metrics such as coverage of resilience goals, detection latency, and recovery time can be used to validate whether sufficient resilience is achieved.

Another open point is the integration of the method into existing development processes. It should be investigated how support from MBSE tools can improve the efficiency and scalability of resilience analysis. Further research could focus on linking the method with MBSE to enable automated analysis and visualization of resilience scenarios. While the current work focuses on a single-system case study, the methodology is designed to be scalable to multi-subsystem automotive architectures. Hierarchical resilience graphs and automated scenario mapping in MBSE tools will be investigated in future work to improve scalability and reduce manual effort. Such integration would support traceability, model consistency, and reduce manual engineering effort. By further developing these aspects, the integration of resilience properties can become an integral process in automotive systems engineering, opening up a new perspective on the resilience of future connected autonomous vehicle systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.B. and A.H.; methodology, I.M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M.B.; writing—review and editing, I.M.B. and E.U.; supervision, A.H. and R.D.; funding acquisition, A.H. and R.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) in the project ConnRAD, grant number 16KISR031. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BCM | Brake Control Module |

| CGW | Central Gateway |

| CHASSIS | Combined Harm Assessment of Safety and Security for Information Systems |

| DoDAF | Department of Defense Architecture Framework |

| EPS | Electronic Power Steering |

| FMEA | Failure Modes and Effects Analysis |

| FuSa | Functional Safety |

| FTA | Fault Tree Analysis |

| HARA | Hazard Analysis and Risk Assessment |

| HAZOP | Hazard and Operability Study |

| INCOSE | International Council on Systems Engineering |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| OEM | Original Equipment Manufacturer |

| OTA | Over-the-Air |

| PCM | Powertrain Control Module |

| SAE | Society of Automotive Engineers |

| SAHARA | Security-Aware Hazard Analysis and Risk Assessment |

| SDL | Scenario Description Language |

| SOTIF | Safety Of The Intended Functionality |

| STPA | System-Theoretic Process Analysis |

| TARA | Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment |

| V2C | Vehicle-to-Cloud communication |

| V2G | Vehicle-to-Grid communication |

| V2I | Vehicle-to-Infrastructure communication |

| V2P | Vehicle-to-Pedestrians communication |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle communication |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything communication |

| VCU | Vehicle Control Unit |

References

- SAE J3016_202104; Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. SAE: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, J.; Shi, Y.; Peng, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, L. Vehicle-to-Everything (v2x) Services Supported by LTE-Based Systems and 5G. IEEE Commun. Stand. Mag. 2017, 1, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Chau, K.T.; Wu, D.; Gao, S. Opportunities and Challenges of Vehicle-to-Home, Vehicle-to-Vehicle, and Vehicle-to-Grid Technologies. Proc. IEEE 2013, 101, 2409–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, H.; Kamalanathsharma, R.K. Eco-driving at signalized intersections using V2I communication. In Proceedings of the 2011 14th International IEEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Washington, DC, USA, 5–7 October 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liao, X.; Zhao, X.; Han, K.; Tiwari, P.; Barth, M.J.; Wu, G. A Digital Twin Paradigm: Vehicle-to-Cloud Based Advanced Driver Assistance Systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 91st Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2020-Spring), Antwerp, Belgium, 25–28 May 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Certad, N.; Del Re, E.; Varughese, J.; Olaverri-Monreal, C. V2P Collision Warnings for Distracted Pedestrians: A Comparative Study with Traditional Auditory Alerts. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 22–25 June 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1340–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibaei, M.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, K.; Abbas, R.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xiang, Y.; Yu, S. Attacks and defences on intelligent connected vehicles: A survey. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2020, 6, 399–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, M.V.; Beyerer, J.; Buck, H.S.; Deml, B.; Ehrhardt, S.; Frese, C.; Kleiser, D.; Lauer, M.; Roschani, M.; Ruf, M.; et al. Cooperative Automated Driving for Bottleneck Scenarios in Mixed Traffic. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–7 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tao, Q.; Feng, S.; Li, L. Distributed Cooperative Driving in Multi-Intersection Road Networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 5390–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnieder, L.; Hosse, R.S. Leitfaden Safety of the Intended Functionality; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOActive Research Team. Remote Exploitation of an Unaltered Passenger Vehicle; Technical White Paper; IOActive: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://www.ioactive.com/wp-content/uploads/pdfs/IOActive_Remote_Car_Hacking.pdf#page=9.23 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Casimiro, A.; Ortmeier, F.; Bitsch, F.; Ferreira, P. (Eds.) Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpidi Bita, I.; Hovemann, A.; Dumitrescu, R. Resilience-By-Design: Standard-based definition of Resilience and identification of action fields for the systems design of mobility system. Proc. Des. Soc. 2025, 5, 2781–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterbenz, J.P.; Hutchison, D.; Çetinkaya, E.K.; Jabbar, A.; Rohrer, J.P.; Schöller, M.; Smith, P. Resilience and survivability in communication networks: Strategies, principles, and survey of disciplines. Comput. Netw. 2010, 54, 1245–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Rodrigues, M.; Theilliol, D.; Shen, Y. Fault-Tolerant Control for Discrete Linear Systems with Consideration of Actuator Saturation and Performance Degradation. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2015, 48, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walden, D.D.; Roedler, G.J.; Forsberg, K.; Hamelin, R.D.; Shortell, T.M. (Eds.) Systems Engineering Handbook: A Guide for System Life Cycle Processes and Activities, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kharatyan, A.; Günther, M.; Anacker, H.; Japs, S.; Dumitrescu, R. Security- and Safety-Driven Functional Architecture Development Exemplified by Automotive Systems Engineering. Procedia CIRP 2022, 109, 586–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, W.L.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, N.N.; Wang, F.Y. Intelligence Testing for Autonomous Vehicles: A New Approach. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2016, 1, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törngren, M.; Gallina, B.; Schoitsch, E.; Troubitsyna, E.; Bitsch, F. (Eds.) Computer Safety, Reliability, and Security. SAFECOMP 2025 Workshops; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholtes, M.; Westhofen, L.; Turner, L.R.; Lotto, K.; Schuldes, M.; Weber, H.; Wagener, N.; Neurohr, C.; Bollmann, M.H.; Kortke, F.; et al. 6-Layer Model for a Structured Description and Categorization of Urban Traffic and Environment. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 59131–59147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillebrand, M. Entwicklungssystematik zur Integration von Eigenschaften der Selbstheilung in Intelligente Technische Systeme. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Paderborn, Paderborn, Germany, 2021. Volume 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tao, J.; Tan, K.; Törngren, M.; Sánchez, J.M.G.; Ramli, M.R.; Tao, X.; Gyllenhammar, M.; Wotawa, F.; Mohan, N.; et al. Finding Critical Scenarios for Automated Driving Systems: A Systematic Mapping Study. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 2023, 49, 991–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21448; Road Vehicles—Safety of the Intended Functionality. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Cho, J.H.; Xu, S.; Hurley, P.M.; Mackay, M.; Benjamin, T.; Beaumont, M. STRAM. ACM Comput. Surv. 2019, 51, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madni, A.M.; Jackson, S. Towards a Conceptual Framework for Resilience Engineering. IEEE Syst. J. 2009, 3, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Tian, J.; Shi, C.; Ling, J.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Z. A multi-stage quantitative resilience analysis and optimization framework considering dynamic decisions for urban infrastructure systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 243, 109851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardeschi, C.; Lami, G.; Merola, F.; Rossi, F. Verifying Robustness of Neural Networks in Vision-Based End-to-End Autonomous Driving. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 71688–71704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; de Paolis, A.; Costantino, F.; Di Gravio, G. Simulation model for simple yet robust resilience assessment metrics for engineered systems. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 209, 107467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulse, D.; Irshad, L. Using Degradation Modeling to Identify Fragile Operational Conditions in Human- and Component-driven Resilience Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/AIAA 41st Digital Avionics Systems Conference (DASC), Portsmouth, VA, USA, 18–22 September 2022; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnus Ågren, S. Manager Perspective Follow-Up Instrument; Zenodo, European Organization for Nuclear Research: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 26262; Road Vehicles—Functional Safety. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO/SAE 21434; Road Vehicles—Cybersecurity Engineering. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Pohl, K. Requirements Engineering Fundamentals: A Study Guide for the Certified Professional for Requirements Engineering Exam; Foundation Level—IREB Compliant, 2nd ed.; Rocky Nook Computing; Rocky Nook: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, T.; Trippel, S.; Dziwok, S.; Bodden, E. Integrating Security Protocols in Scenario-based Requirements Specifications. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Model-Driven Engineering and Software Development, Online, 6–8 February 2022; SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications: Setúbal, Portugal, 2022; pp. 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbas, R.; Nolte, M.; Eberle, U.; Hungar, H.; Mosebach, H.; Salem, N.F.; Schittenhelm, H.; Reich, J.; Kirschbaum, T.; Westhofen, L. V&V Methods Safety Assurance Positioning Paper; The German Aerospace Center (DLR): Cologne, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Tekaat, J.; Kharatyan, A.; Anacker, H.; Dumitrescu, R. Potentials for the Integration of Design Thinking along Automotive Systems Engineering Focusing Security and Safety. Proc. Des. Soc. Int. Conf. Eng. Des. 2019, 1, 2883–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezcan, M.; Iskesen, T.; Isman, B.; Kocahan, T. Theoretical Proposal in SOTIF based Hazardous Scenario Generation. In Proceedings of the 2024 Innovations in Intelligent Systems and Applications Conference (ASYU), Ankara, Turkiye, 16–18 October 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, R.E.; Moller, D.P.F. Automotive connectivity, cyber attack scenarios and automotive cyber security. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Electro Information Technology (EIT), Piscataway, NJ, USA, 14–17 May 2017; pp. 635–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]