Abstract

Efficient resource allocation is a central challenge in multi-tenant cloud, fog, and edge environments, where heterogeneous tenants compete for shared resources under dynamic and uncertain workloads. Static or purely heuristic methods often fail to capture strategic tenant behavior, whereas many existing game-theoretic approaches overlook stochastic demand variability, fairness, or scalability. This paper proposes a Dynamic and Stochastic Game-Theoretic Allocation (DSGTA) model that jointly models non-cooperative tenant interactions, repeated strategy adaptation, and random workload fluctuations. The framework combines a Nash-like dynamic equilibrium, achieved via a lightweight best-response update rule, with an approximate Shapley-value-based fairness mechanism that remains tractable for large tenant populations. The model is evaluated on synthetic scenarios, with a trace-driven setup built from the Google 2019 Cluster dataset, and a scalability study is conducted with up to heterogeneous tenants. Using a consistent set of core metrics (tenant utility, resource cost, fairness index, and SLA satisfaction rate), DSGTA is compared against a static game-theoretic allocation (SGTA) and a dynamic pricing-based allocation (DPBA). The results, supported by statistical significance tests, show that DSGTA achieves higher utility, lower average cost, improved fairness and competitive utilization across diverse strategy profiles and stochastic conditions, thereby demonstrating its practical relevance for scalable, fair, and economically efficient resource allocation in realistic multi-tenant cloud environments.

1. Introduction

Cloud computing has profoundly transformed how computational resources are provisioned and consumed, providing elastic, pay-as-you-go services to enterprises, service providers, and end users [1]. Yet, efficiently managing these shared resources in multi-tenant infrastructures remains challenging. Tenants generate heterogeneous and time-varying workloads, compete for limited CPU and memory capacity, and operate under diverse service-level agreements (SLAs) [2]. In such environments, suboptimal allocation decisions can quickly propagate into economic and performance issues: over-provisioning wastes capacity and inflates operational costs, while under-provisioning degrades QoS, increases response times, and leads to SLA violations and customer dissatisfaction [3].

To address these challenges, a rich body of work has explored heuristic and metaheuristic optimization, machine learning (ML), and queuing-theoretic models. Heuristic and metaheuristic methods can find near-optimal allocations, but they often require careful tuning and may react slowly to abrupt workload changes [4]. ML-based approaches can predict future demands and support adaptive autoscaling policies, but they depend on large training datasets, introduce additional model-management complexity, and may be difficult to generalize across tenants and platforms [5]. Queuing models provide valuable analytical insights into congestion and waiting times, yet they frequently rely on restrictive assumptions that limit their applicability in complex, highly heterogeneous cloud, fog, and edge settings [6].

Game theory offers a complementary perspective by explicitly modelling tenants as strategic agents that compete or cooperate to maximize their own objectives. Non-cooperative games capture selfish behavior and use Nash equilibrium as a notion of strategic stability, while cooperative games employ constructs such as the Shapley value to design fair and incentive-compatible sharing rules [7,8]. Existing game-theoretic resource allocation schemes, however, typically fall into one of three categories. Static models solve a single-shot game under fixed demand and capacity assumptions, which limits their ability to react to temporal dynamics. Dynamic (repeated) games allow strategy updates over time but often ignore stochastic demand fluctuations and SLA heterogeneity. Stochastic formulations introduce probabilistic state transitions, yet they rarely integrate explicit fairness mechanisms such as the Shapley value or address the computational cost of these mechanisms at scale.

Moreover, most prior work is evaluated either on small-scale synthetic settings or on simplified benchmarks, with limited consideration of scalability, real-world traces, or statistical significance of the observed improvements. As a result, there is still a gap between theoretically elegant game-theoretic models and practically viable controllers that can operate in large multi-tenant cloud, fog, and edge infrastructures under realistic, bursty workloads.

In this article, we propose a Dynamic and Stochastic Game-Theoretic Allocation (DSGTA) model that targets this gap. DSGTA jointly captures (i) the strategic interactions among tenants through a non-cooperative game, (ii) the temporal adaptation of strategies via repeated interactions, (iii) the uncertainty and burstiness of workloads through a stochastic game perspective, and (iv) fairness via a Shapley-value-based sharing principle. The model is instantiated as a lightweight, decentralized update rule in which tenants adjust their strategies based on observed utilities, while the provider enforces capacity constraints and monitors fairness and SLA satisfaction. The approach is evaluated on synthetic scenarios and on realistic Google Cluster traces, and its scalability is assessed up to hundreds of tenants with heterogeneous SLAs.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

- We develop a unified dynamic and stochastic game-theoretic model for resource allocation in multi-tenant cloud environments, explicitly combining non-cooperative games, repeated interactions, and stochastic states to capture strategic adaptations and demand uncertainty.

- We integrate Nash equilibrium and Shapley value concepts practically: Nash-like equilibria are reached via a decentralized best-response update. At the same time, fairness is enforced through an approximate Shapley-based mechanism that remains computationally tractable for large tenant populations.

- We provide a comprehensive empirical evaluation of DSGTA, using synthetic scenarios and a trace-driven setup based on Google Cluster data, and we analyze its behavior under diverse strategy profiles, stochastic demand perturbations, and different numbers of tenants (up to ) with heterogeneous SLAs.

- We conduct a comparative study against a static game-theoretic allocation (SGTA) and a dynamic pricing-based allocation (DPBA), and we show that DSGTA consistently achieves higher tenant utility, lower costs, and better fairness while maintaining controlled utilization.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on resource allocation in cloud, fog, and edge computing, with a particular focus on game-theoretic approaches. Section 3 introduces the theoretical foundations of the proposed model, including the utility formulation, Nash equilibrium, and Shapley-based fairness. Section 4 presents the dynamic and stochastic instantiation of DSGTA, with the decentralized strategy-update algorithm. Section 5 reports and analyses the simulation results on synthetic and trace-driven scenarios, while Section 6 details the comparative evaluation with baseline schemes. Section 7 discusses the broader implications, scalability aspects, and potential extensions of the model. Finally, Section 8 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Enhancing scalability, optimizing resource usage, guaranteeing QoS, complying with SLAs, and reducing operational costs are central challenges in modern cloud computing environments. To address these objectives, the literature has explored a wide range of approaches, including heuristic and metaheuristic algorithms, queuing theory, machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and game theory.

Metaheuristic algorithms are widely adopted because they can efficiently handle large and complex optimization problems, such as task scheduling and resource allocation. Zuo et al. [9] proposed an improved ant-colony-based multi-objective scheduling model that simultaneously reduces makespan, cost, and deadline violations. Tsai et al. [10] provided a comprehensive survey of metaheuristic techniques for cloud scheduling, highlighting their ability to enhance solution quality for difficult optimization tasks. Zhou et al. [11] compared several metaheuristic load-balancing strategies, including Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), and showed that PSO achieves better makespan, throughput, and response time than alternative methods. Nanda et al. [12] reviewed metaheuristic-based resource allocation mechanisms and reported improvements in resource utilization, energy efficiency, and cost reduction across different cloud scenarios. More recently, Barut et al. [13] combined metaheuristics with ML in a rule-based scheduler that substantially accelerates decision making, demonstrating the suitability of these methods for real-time cloud systems.

Queuing theory constitutes another important family of techniques, providing analytical models to predict and evaluate cloud system performance. Khazaei et al. [14] developed an M/G/m/m+r queuing model capable of accurately estimating key performance indicators such as mean response time and blocking probability. Srivastava et al. [15] extended queuing-based models to support elastic scaling of containerized services, thereby improving SLA satisfaction and resource utilization. Ghazali et al. [16] adopted a processor-sharing queue to study task scheduling under heavy traffic and showed that the model enhances system stability and load management. Ghandour et al. [17,18] proposed queuing-theoretic frameworks for dynamic workload and resource management in cloud data centers, achieving SLA compliance, QoS improvements, and resource optimization, with simulation and AWS-based validation. El Kafhali et al. [19] introduced a scalable queuing model for elastic container management, which reduces operating costs while improving service quality. In addition, Chauhan et al. [20] presented a thorough survey of queuing theory applications in cloud computing, underlining their robustness for performance optimization and resource management.

ML- and DL-based methods have recently emerged as powerful tools for cloud resource management, providing predictive capabilities and data-driven decision support. Chaudhary et al. [21] proposed an AI-driven framework based on deep neural networks and reinforcement learning for dynamic scheduling, achieving substantial reductions in average waiting time and better resource utilization. Saxena and Singh [22] investigated ML models for workload forecasting and showed that accurate predictions enable proactive resource provisioning and help prevent SLA violations. Zhang et al. [23] examined ML-based optimization techniques for cloud resource scheduling and reported improved scheduling quality and lower operational costs in realistic settings. Wang and Yang [24] designed an intelligent allocation scheme that combines LSTM-based demand prediction with DQN-based scheduling, leading to higher utilization and reduced response times. Complementarily, Mungoli et al. [25] studied scalable distributed AI frameworks on cloud infrastructures and demonstrated that appropriate optimization and parallelization strategies can speed up deep learning training while keeping deployment costs low.

Game theory provides a principled way to model strategic interactions between cloud tenants and providers. Zafari et al. [8] proposed a cooperative game-theoretic framework for resource sharing among providers, improving resource utilization and user satisfaction. Srinivasan et al. [26] applied game-theoretic dynamic pricing to demand-side energy management, achieving significant peak-load reduction and cost savings while aligning economic incentives. Maldonado-Carrascosa et al. [27] combined game theory with particle swarm optimization to design VM migration policies that enhance energy efficiency and resource usage in data centers. Bataineh et al. [7] modeled cloud platforms as two-sided markets for data services and showed that their game-theoretic mechanism increases profit and improves allocation between data providers, platforms, and users.

More recently, mechanism-design and auction-based game-theoretic models have gained traction in closely related domains such as mobile crowdsensing and vehicular IoT. Chen et al. [28] introduced SVRANet, a deep-learning-assisted reverse auction for semantic communication in IoV crowdsensing, jointly deciding task assignment, data pricing, and communication resource allocation under budget and bandwidth constraints while satisfying incentive compatibility, individual rationality, and budget feasibility. In a related direction, Zhang et al. [29] proposed an optimal reverse affine maximizer auction for task allocation in mobile crowdsensing. Their approach formulates task assignment as a reverse auction and employs affine maximizer mechanisms to achieve truthfulness, budget feasibility, and near-optimal utility, illustrating that carefully designed auction mechanisms can scale to realistic large-scale sensing environments.

Lastly, Kakkad et al. [30] surveyed game-theoretic applications in cloud computing and cybersecurity, and concluded that game theory offers flexible and effective tools for modeling and resolving complex interaction and security problems in distributed systems.

Table 1 succinctly summarizes and clarifies the distinctive features and contributions of the discussed papers, providing clear insight into each methodological approach’s strengths and specific application areas.

Table 1.

Comparative analysis and summary of related research works in cloud computing resource management.

3. Proposed Theoretical Model

This section introduces a robust theoretical model grounded in non-cooperative game theory to address the dynamic resource allocation challenge in multi-tenant cloud computing. The primary objective is to create a strategic interaction environment where multiple tenants, viewed as rational decision-making entities, seek optimal resource distribution to maximize their utility. The utility of each tenant reflects the benefits obtained from allocated resources, the associated financial costs, and potential penalties arising from non-compliance with the SLA.

3.1. Non-Cooperative Game Formulation

In this subsection, we formalise the resource allocation problem as a non-cooperative game in which tenants act as self-interested decision-makers. The goal is to capture how their individual resource requests, driven by performance, cost, and SLA considerations, interact within a shared-capacity environment and lead to stable operating points.

3.1.1. Players: Tenants as Strategic Decision-Makers

We define each tenant as an individual strategic actor in a non-cooperative game. Tenants represent organizations or users who consume shared computational resources (such as CPU, memory, bandwidth, and storage) to execute their applications or services. As rational players, tenants aim to enhance their performance outcomes by intelligently managing resource demands while concurrently minimizing incurred costs and avoiding SLA violation penalties.

The utility each tenant derives depends primarily on three elements: allocated resources, costs linked to those resources, and adherence to SLA conditions. Thus, tenants must strategically choose their resource demand level based on the anticipated behavior of competing tenants and the limited availability of cloud resources.

3.1.2. Resource Allocation Actions and Strategies

In this non-cooperative framework, tenants can adopt distinct strategies regarding their resource requests. Each tenant’s chosen strategy influences the overall system performance, creating dynamic interactions among participants. Three primary resource allocation strategies emerge:

- An Aggressive strategy involves requesting substantially more resources than necessary to ensure adequate allocation during periods of high competition.

- A Moderate strategy closely aligns resource requests with actual tenant requirements, balancing between performance and cost efficiency.

- A Conservative strategy entails minimal resource requests, emphasizing cost savings but risking insufficient allocation during peak resource demands.

These strategies have significant effects on system efficiency as a whole. For instance, mass usage of aggressive strategies leads to resource congestion and deterioration in performance, whereas just conservative strategies can lead to extreme under-utilization, limiting overall system productivity. Hence, tenants must strategically modify their decisions based on the current level of competition and resource availability conditions.

3.2. Mathematical Formalization of Tenant Utility

To quantify tenants’ strategic behavior and decision-making processes, we define a comprehensive tenant utility function as follows:

where each term clearly expresses a vital aspect of tenant satisfaction:

- -

- The performance component characterizes the quality of service derived from allocated resources . This term can be modeled as a logarithmic function, capturing diminishing returns as resource allocations increase:where is a tenant-specific scaling parameter reflecting performance sensitivity.

- -

- The cost component represents the financial burden incurred due to allocated resources. Typically, resource usage charges follow a linear structure defined bywhere indicates the cost per resource unit.

- -

- The SLA penalty term accounts for financial or operational penalties tenants face if allocated resources are insufficient compared to their demanded resources :where denotes penalty severity. This penalty discourages tenants from underestimating resource needs significantly.

From a modeling viewpoint, the parameters , , and control the trade-off between performance gains, monetary costs and SLA penalties, and they should be interpreted as design proxies built from observable QoS and billing indicators rather than as tenants’ latent subjective preferences. Increasing magnifies the marginal value of additional resources, whereas increasing or makes tenants more sensitive to costs and SLA violations. Analytically, the qualitative shape of and the structure of best responses are preserved when are rescaled within reasonable ranges, and different tenants can be assigned distinct triples to capture heterogeneous profiles.

3.3. Tenant Interactions and Nash Equilibrium

Tenant interactions, guided by competitive resource allocation, form the foundation of our game-theoretic model. Each tenant selects a strategy anticipating the behavior of others, resulting in an equilibrium state known as the Nash equilibrium. At this equilibrium, tenants have no incentive to deviate from their chosen strategies since unilateral changes would not improve their utility outcomes.

Mathematically, the Nash equilibrium for tenants is established when

where represents equilibrium resource requests and denotes other tenants’ equilibrium strategies. Computationally, this equilibrium can be approximated through iterative algorithms such as gradient-based methods or decentralized optimization, enabling tenants to progressively adapt their strategies based on system dynamics.

In DSGTA, the Nash-like operating point is reached through repeated play driven by local feedback. At each decision round, tenants observe their realised utility (which already aggregates performance, cost and SLA penalties) and update their requested resources according to a simple, local rule: if utility is low (typically due to poor QoS or SLA violations), the tenant increases its demand by switching to a more aggressive strategy; if utility is very high (indicating over-provisioning and unnecessary costs), it moves towards a more conservative strategy; otherwise it remains in a moderate regime. Because all tenants share a finite capacity, any change in one tenant’s strategy modifies the utilities of the others, which in turn triggers further adjustments. Repeating this process across rounds leads to a dynamic equilibrium in which strategies and utilities stabilise, so that no tenant can significantly improve its long-term utility by unilaterally changing its behavior given the strategies of the others.

3.4. Ensuring Fairness: Integration of Shapley Value

To supplement equilibrium-driven efficiency with fairness considerations, we integrate the Shapley value from cooperative game theory into our model. This integration guarantees equitable resource allocation reflecting tenants’ marginal contributions to the collective system performance. The Shapley value allocation for tenant i is formally defined as

where represents the aggregated performance of coalition S, and N denotes the full tenant set. This approach ensures that tenants who significantly enhance collective outcomes receive proportionally greater resource allocations, preventing monopolization and promoting cooperative fairness.

In the dynamic, non-cooperative setting considered in this work, the Shapley value is used as a fairness layer on top of DSGTA. For each decision window, we consider the set of tenants that are active in that window and compute their marginal contributions to a system-wide performance measure. The corresponding Shapley values serve as long-term fairness references that can be mapped to resource entitlements or to credit/revenue redistribution, ensuring that tenants with larger contributions receive a proportionally larger share of the global benefit. Importantly, the Shapley computation is performed ex post and does not intervene in the fast inner loop of strategy updates, so it does not alter the local best-response dynamics described above. To avoid the exponential complexity of the exact formula when many tenants are present, we rely on standard Monte Carlo approximations that sample a limited number M of random permutations of tenants and estimate each marginal contribution along these permutations. This reduces the complexity to per window. In large-scale scenarios, we further restrict Shapley-based analysis to the most active tenants while monitoring global equity through aggregate indices such as Jain’s fairness index. This yields a practically scalable way to incorporate Shapley-based fairness into a dynamic, non-cooperative allocation framework.

3.5. Incentive Mechanisms for Honest Resource Requests

To encourage tenants toward genuine resource demands, incentive mechanisms are employed. Progressive pricing schemes, where charges escalate disproportionately with excessive resource requests, effectively discourage wasteful allocations. Additionally, penalties for resource under-utilization incentivize accurate demand forecasting, thereby enhancing overall system efficiency. These incentives collectively guide tenants to align their strategic decisions closely with true operational requirements.

3.6. Rationale for Model Decomposition

Given the intrinsic complexity and dual nature of cloud resource allocation (in terms of strategic interactions among tenants and the dynamic unpredictability of resource demands), we decompose the overall modeling framework into two interrelated components. This first theoretical component focuses explicitly on defining strategic interactions, resource allocation mechanisms, equilibrium determination, and fairness. The subsequent dynamic and stochastic component (presented separately) specifically addresses real-time adaptability to demand variations and unforeseen fluctuations inherent in cloud environments. By separating these aspects, the model ensures comprehensive theoretical clarity, easier computational implementation, and practical applicability within realistic cloud operational contexts.

3.7. Summary and Model Overview

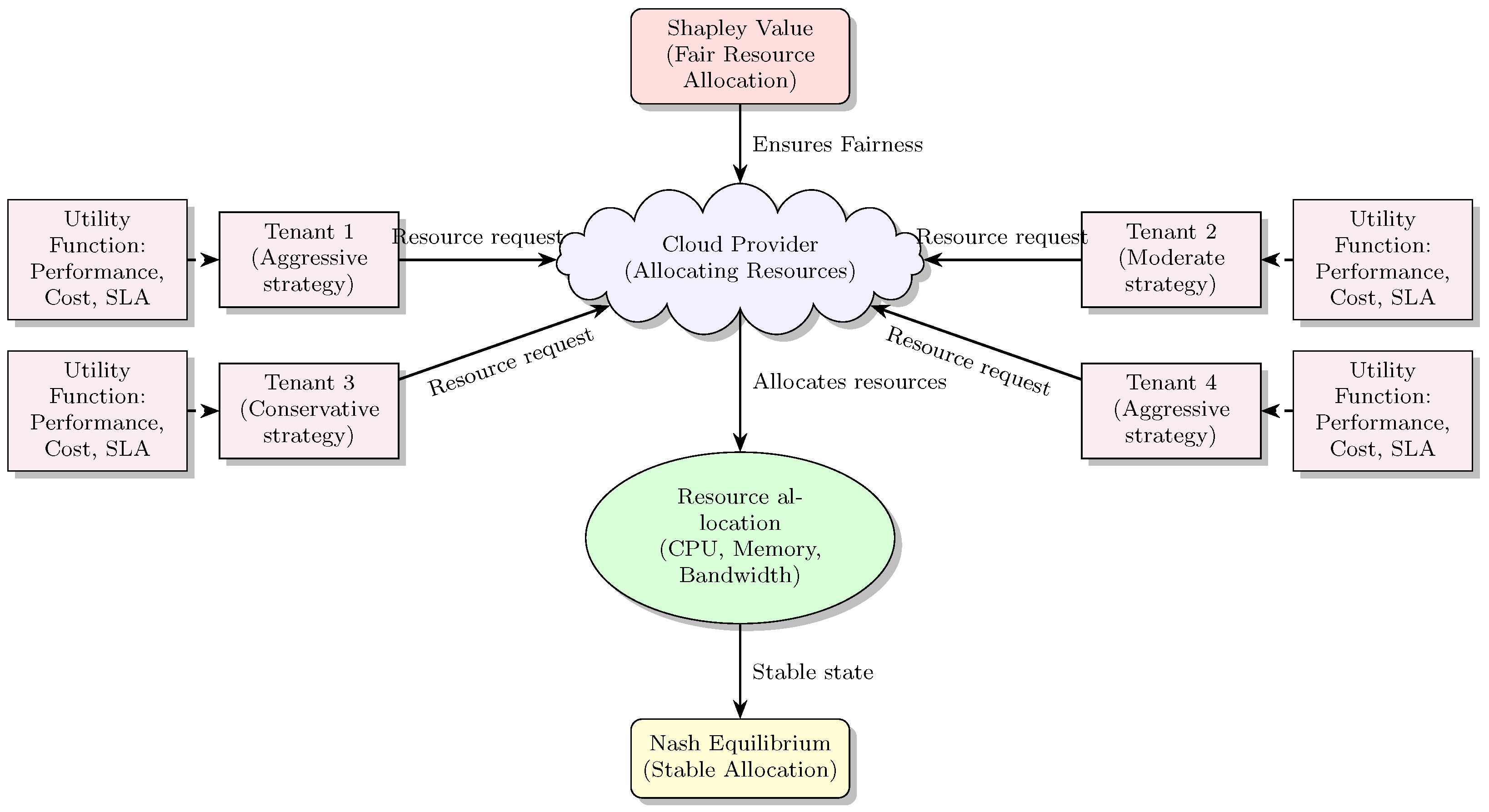

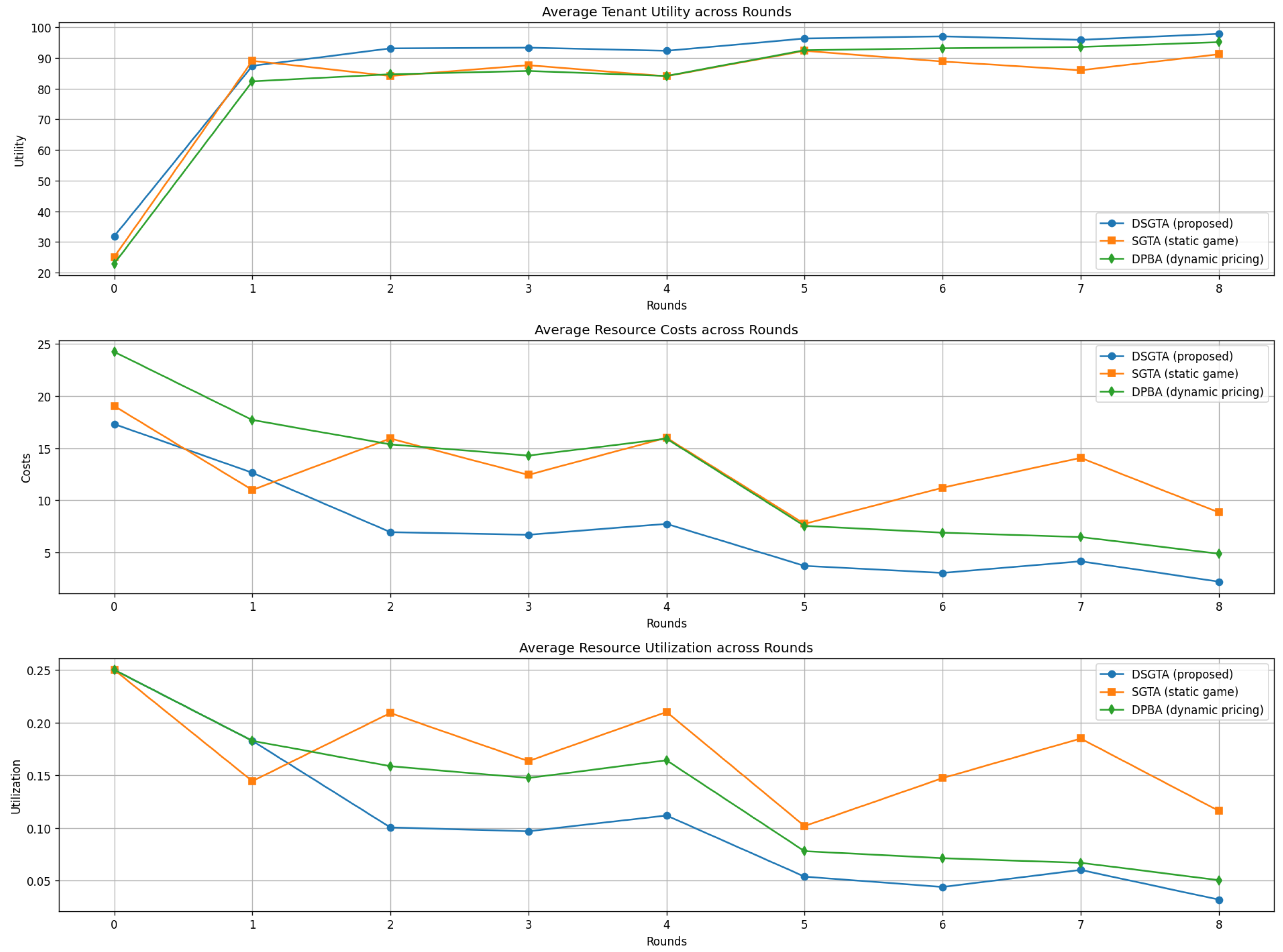

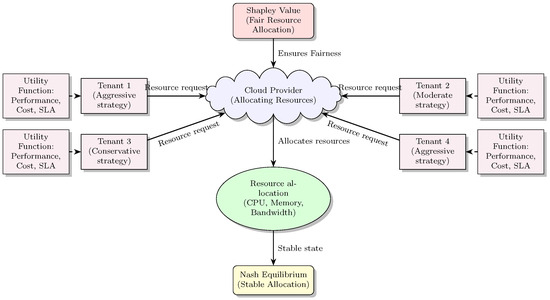

Figure 1 summarizes the proposed game-theoretic resource allocation model, explicitly illustrating tenant interactions, strategy selection, resource allocations by the cloud provider, Nash equilibrium, and fairness enforced via Shapley value integration. The visualization succinctly captures the structured interaction dynamics, strategic complexity, and fairness mechanisms central to our proposed theoretical model, providing an intuitive understanding of the modeled strategic ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Proposed model for Game-Theoretic resource allocation in Multi-Tenant cloud computing.

Ultimately, our theoretical framework presents a robust, efficient, and fair solution capable of addressing the complex dynamics and competitive interactions characterizing modern multi-tenant cloud resource allocation scenarios.

4. Dynamic and Stochastic Model for Scalability

This section develops a detailed mathematical framework capturing the dynamic and stochastic aspects inherent in resource allocation within multi-tenant cloud environments. The model aims to provide a robust analytical basis to ensure scalability, adaptability, and effective management of resource fluctuations. Specifically, it addresses two interconnected facets: dynamic adjustments through repeated interactions (Repeated Games) and resource allocation under uncertainty (Stochastic Games). This decomposition allows clear handling of temporal variations and unpredictable demand fluctuations, enhancing the practical effectiveness and theoretical soundness of the proposed approach.

4.1. Repeated Games for Dynamic Resource Allocation

Cloud environments are characterized by continual interactions where tenants regularly request resources from the cloud provider. To accurately represent this continual interaction and adaptation, we employ the framework of repeated games. Unlike static allocation scenarios, repeated games allow tenants to dynamically adjust their resource allocation strategies based on previous interactions, received feedback, and evolving performance metrics.

At each time step t, tenant i strategically selects resource demands to maximize their utility. Tenant utility at each time t integrates allocated resource performance , cost , and SLA penalties :

To capture the dynamic adaptation of tenant strategies, we define an adjustment mechanism based on feedback from previous allocation outcomes. This adaptation is formally expressed through a strategy update function:

where encapsulates tenants’ decision-making rules informed by their past utility and the feedback provided by the cloud system regarding resource utilization and SLA compliance. Tenants increase resource requests if previous allocations failed to meet performance requirements and reduce requests if previous rounds resulted in unnecessary expenditures.

In the DSGTA implementation, this generic update rule is instantiated as a simple, fully decentralized algorithm that approximates a dynamic Nash equilibrium under limited information. Initially, all tenants select one of the three strategies (aggressive, moderate, conservative) and submit the corresponding resource requests based on their trace-derived baseline demand. After each round, each tenant receives local feedback in the form of its realized utility, cost, and SLA status only. If falls below a lower threshold (low satisfaction, often due to SLA violations), the tenant i switches to a more aggressive strategy at round ; if exceeds an upper threshold (very high satisfaction with potentially unnecessary cost), it switches to a more conservative strategy; otherwise, it remains in a moderate regime. Because all tenants share a finite capacity, changing one tenant’s strategy modifies the allocation and thus the utilities of the others, which in turn triggers further updates. Iterating this threshold-based best-response rule across rounds leads to a fixed point where strategies no longer change and utilities fluctuate within a narrow band. This fixed point corresponds to a dynamic equilibrium of the repeated game, consistent with the Nash condition in Equation (5), but obtained through local adaptation rather than global, closed-form optimization.

Algorithm 1 summarizes the dynamic best-response procedure used in DSGTA. At the beginning of each decision window, each tenant selects an initial strategy (aggressive, moderate, or conservative) and requests resources accordingly. After the allocation is performed, the tenant observes its realized utility, which combines performance, cost, and SLA penalties. If the utility falls below a lower threshold, the tenant switches to a more aggressive strategy in the next round; if the utility exceeds an upper threshold, it switches to a more conservative strategy; otherwise, it keeps a moderate behavior. This procedure is repeated until the strategies and utilities no longer change across successive rounds, which corresponds to a dynamic Nash-like equilibrium of the repeated game.

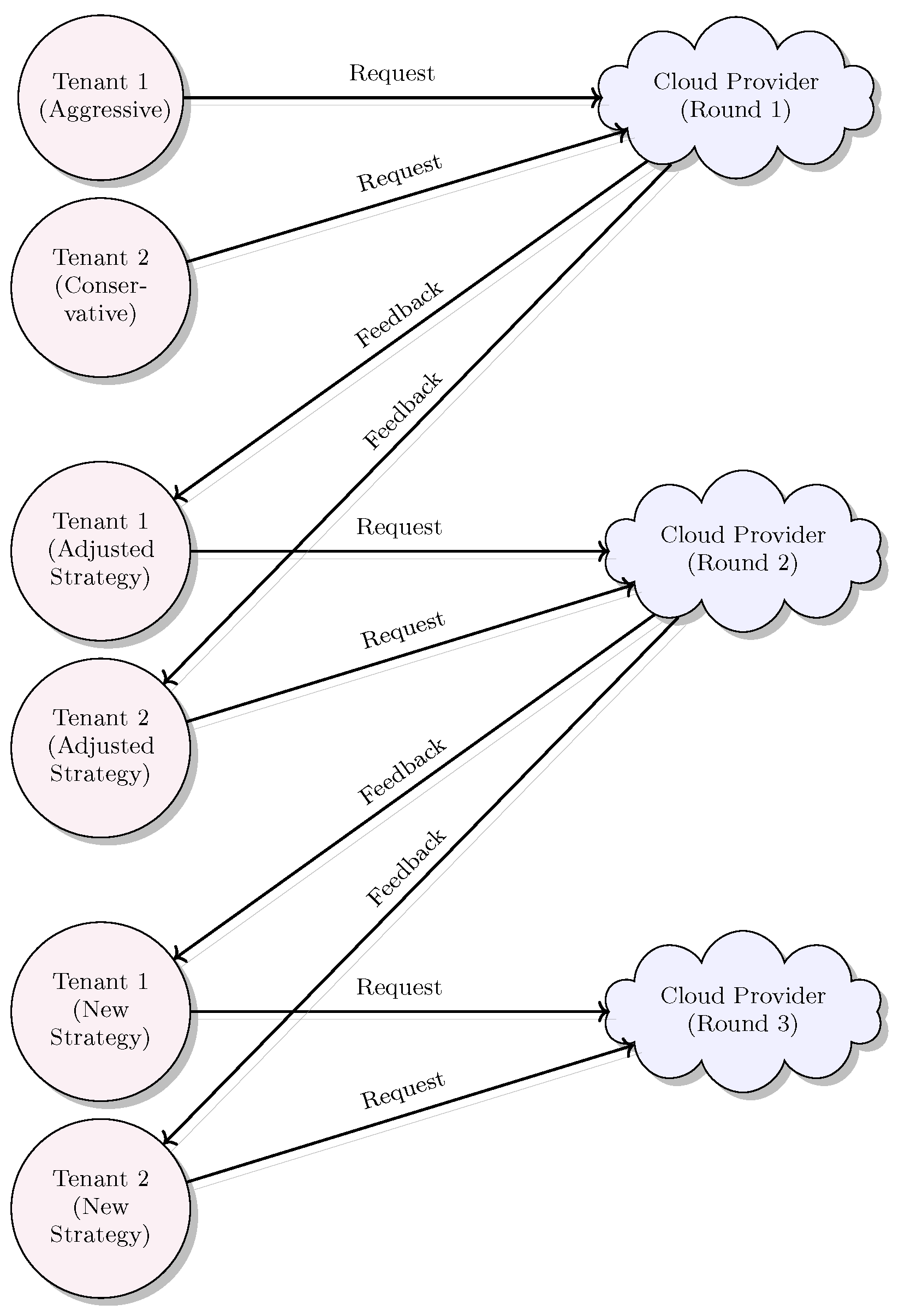

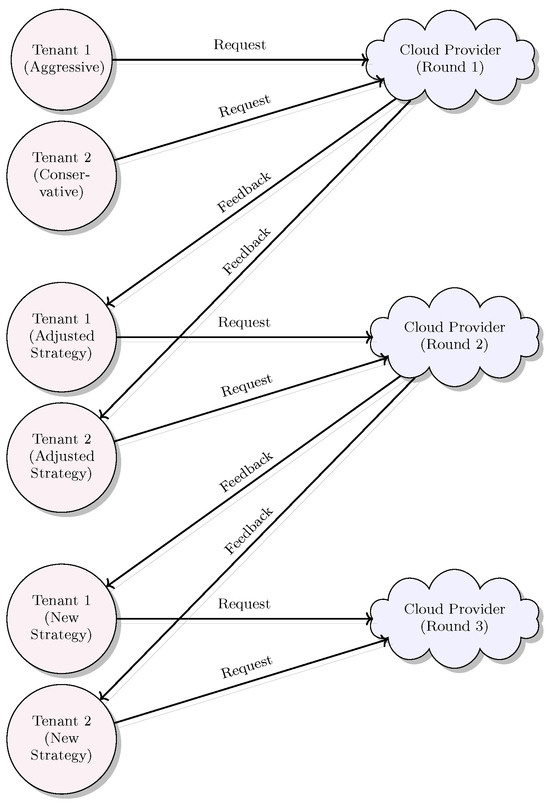

Figure 2 visually summarizes this dynamic interaction process, highlighting continuous feedback loops between tenants and the cloud provider. This representation emphasizes the iterative, adaptive nature of tenants’ strategies, continuously evolving to match dynamic system conditions.

Figure 2.

Repeated Games: Two Tenants Adjust Strategies Across Three Rounds.

This repeated interaction model explicitly addresses scalability challenges by allowing continuous recalibration of resource allocations. Such adaptive strategies lead to a more efficient equilibrium over time, enhancing overall system responsiveness and resource utilization efficiency.

| Algorithm 1 Dynamic best-response update in DSGTA |

|

4.2. Stochastic Games: Managing Uncertainty in Resource Allocation

In realistic cloud environments, tenants frequently encounter unpredictable variations in resource demand, including sudden spikes or unanticipated drops in workload. To accurately model this uncertainty, we extend the repeated game framework into a stochastic game formulation, incorporating probabilistic elements to capture random variations in demand and system conditions.

Formally, we define a stochastic game as a sequence of allocation rounds, each characterized by a specific environmental state . Each state s represents different workload scenarios (such as traffic spikes, moderate demands, low workloads), each occurring with a probability . Tenant utility in this stochastic context is described by the expected utility across all possible states, mathematically represented as follows:

where and indicate state-specific resource allocations and SLA conditions, respectively. By optimizing expected utility, tenants strategically account for future uncertainties, enhancing robustness and stability in their allocation decisions.

The equilibrium condition under this stochastic framework extends the Nash equilibrium definition to a state-dependent form, ensuring tenants cannot improve their expected utility by unilaterally altering their strategy in any potential state:

To make the link with the expected-utility formulation in Equation (9) explicit, we interpret Equation (10) as a state-wise best-response condition induced by a stationary strategy profile. The overall objective of each tenant is to maximize its expected utility over the distribution of states , but decisions are taken myopically at each round based on the currently realized state and on local feedback. Under standard assumptions (ergodicity of the state process and stationarity of strategies), satisfying the state-wise Nash condition in (10) for almost all realized states is equivalent to maximizing in (9). The repeated-game dynamics of DSGTA thus implement a stochastic Nash equilibrium in expected utility: tenants adapt their strategies round after round using only local observations, yet the resulting stationary profile maximizes their long-run expected utility over the random workload trajectories.

In this context, denotes optimal resource allocation strategies tailored to each possible state s. This equilibrium ensures strategic stability and efficient resource distribution despite inherent unpredictability in cloud workloads.

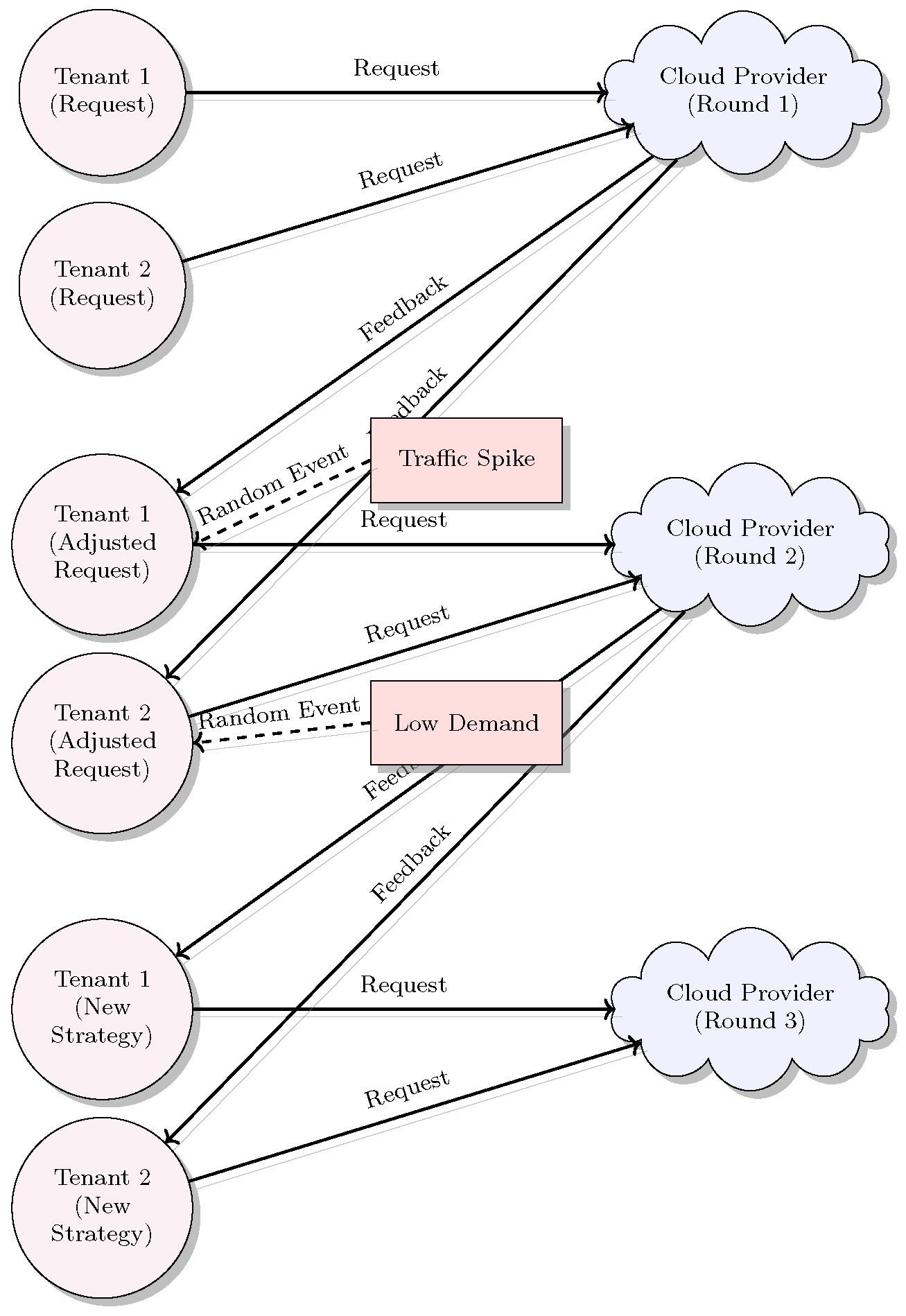

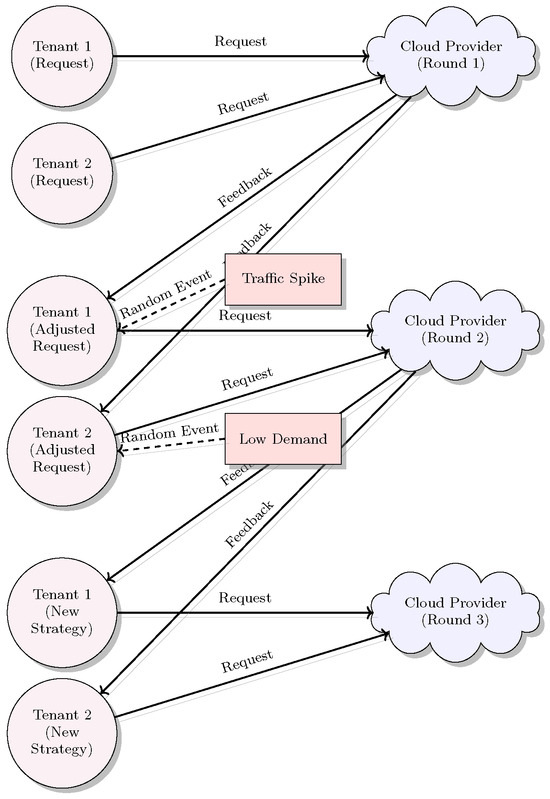

The stochastic game paradigm is illustrated in Figure 3, schematically illustrating how randomness influences tenant behavior. This illustration makes comprehensible the adaptive behavior of tenants to unexpected variations and thereby guarantees the stability of system performance and resource-efficient operation under intense variability.

Figure 3.

Stochastic Game Model of Tenant Strategy Adaptation under Random Variability.

4.3. Explanation of Decomposition of Model into Dynamic and Stochastic Elements

Splitting the scalability model into stochastic (stochastic games) and dynamic (repeated games) components is of analytical as well as practical interest. The repeated game pattern is ideal for managing expected dynamic variation because it tracks temporal strategy adjustment across multiple rounds. Yet, the stochastic game extension addresses unpredictable fluctuations and inserts uncertainty into strategy planning. Complex cloud environments are broken down into manageable pieces of analysis by this process, each of which deals with a distinct operational challenge: strong decision-making under uncertainty for unforeseen changes and adaptive changes for expected changes.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents and discusses the outcomes of the simulation campaign carried out to evaluate the proposed Dynamic and Stochastic Game-Theoretic Allocation (DSGTA) model. We first describe the synthetic scenarios used to stress different strategic behaviors, then analyze their results. We then complement this analysis with a trace-driven evaluation based on the Google Cluster dataset, including a large-scale experiment with hundreds of tenants. The combined results aim to assess the efficiency and the robustness of DSGTA in realistic multi-tenant cloud environments.

5.1. Simulation Environment and Scenario Descriptions

All simulations were implemented in Python 3.13.7, using NumPy 2.3.2 for numerical computations and Matplotlib 3.10.5 for graphical reporting. Unless otherwise stated, experiments were run on a single machine equipped with an Intel Core i7 processor and 16 GB of RAM. This setting is sufficient to emulate the decision logic of the controller and to study its dynamic behavior over many rounds.

To capture a broad range of strategic behaviors, four synthetic scenarios were designed:

Scenario 1 (Aggressive-dominant). Two tenants adopt aggressive strategies and consistently over-request resources to maximize their performance, while the remaining tenants follow moderate and conservative policies. This scenario creates strong initial contention and tests the ability of DSGTA to stabilize the system.

Scenario 2 (Moderate-balanced). All tenants start from moderate strategies, with requests that closely track their expected needs. This balanced configuration is used to assess the efficiency and fairness of DSGTA in a regime without deliberately extreme behaviors.

Scenario 3 (Conservative-dominant). Most tenants behave conservatively and significantly limit their requests to minimize costs, while one or two tenants keep moderate or aggressive stances. This scenario examines how the model reacts to potential under-utilization of resources and whether it can still reach a fair equilibrium.

Scenario 4 (Complex multi-strategy). The number of tenants is increased, and a mixture of aggressive, moderate, and conservative policies is considered. This setting is designed as a synthetic stress test for scalability and robustness in heterogeneous environments.

5.2. Analysis of Synthetic Scenario Results

We first analyze the behavior of DSGTA under the four synthetic scenarios described in Section 5. In these experiments, tenant workloads are generated from controlled demand patterns that emulate aggressive, moderate, and conservative behaviors, allowing us to stress-test the dynamic game-theoretic controller under well-identified conditions. For each scenario, we monitor three core indicators over successive decision rounds: tenant utilities, resource utilization, and resource costs. Utilities capture the trade-off between delivered performance, monetary cost, and SLA violations; utilization quantifies how much of the available capacity is actually consumed; and costs represent the economic impact on tenants.

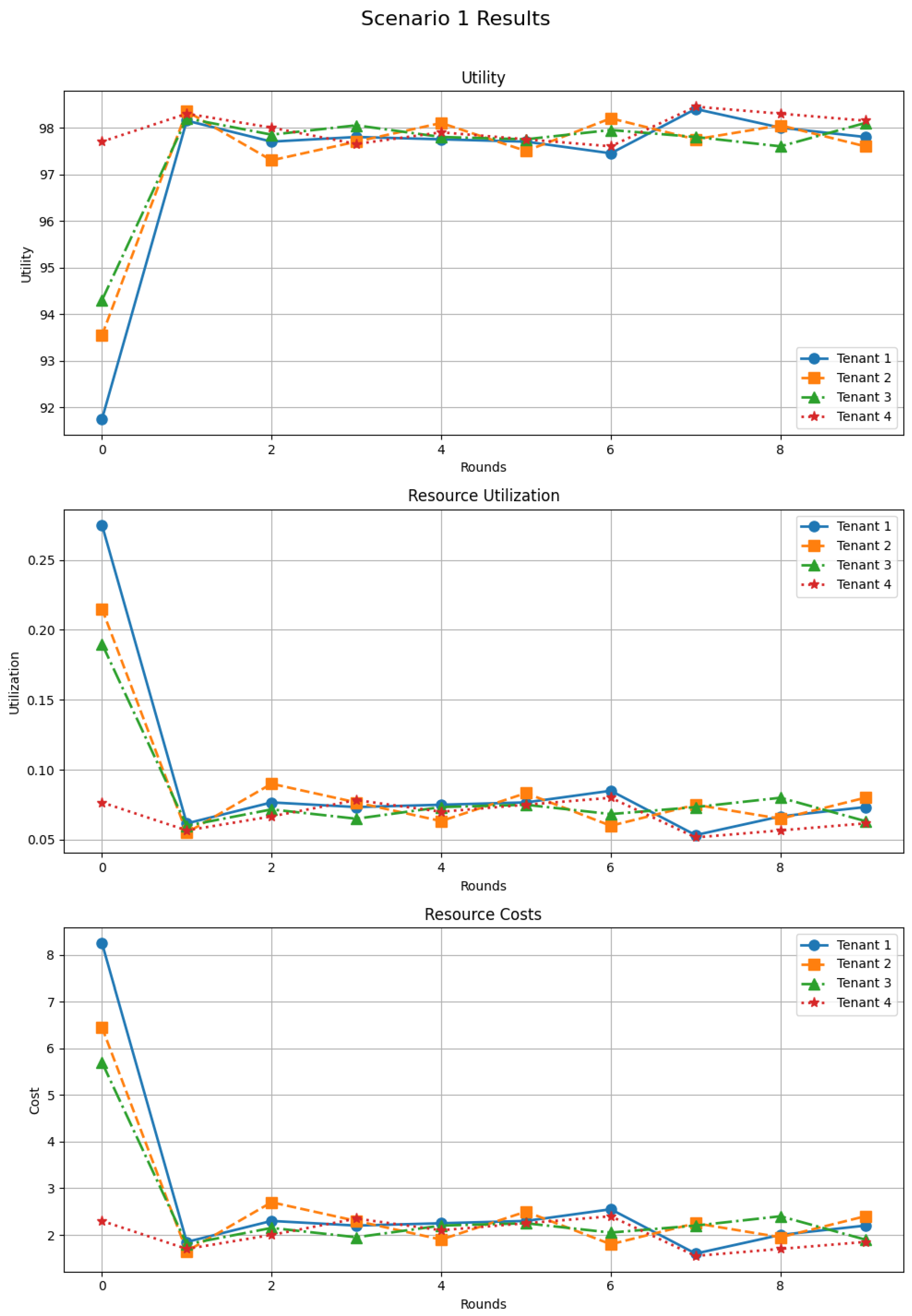

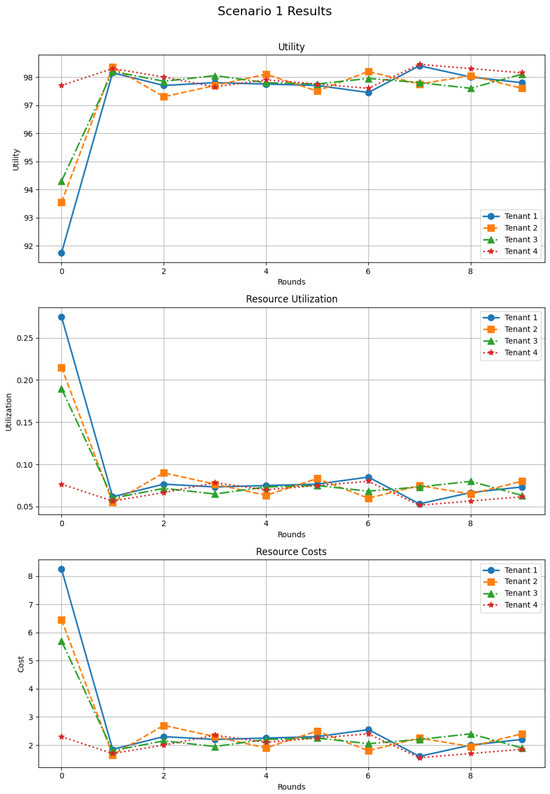

5.2.1. Scenario 1 Results (Aggressive-Dominant)

Figure 4 reports the results for Scenario 1. At the first round, aggressive requests induce relatively low utilities (in the low 90s), high utilization (around 25%), and elevated costs (6–8 units). After a few rounds of interaction, utilities increase and stabilize near 98 for all tenants, while utilization and costs converge towards lower, more homogeneous levels. This confirms that DSGTA can quickly dampen the effects of initial over-provisioning and drive the system towards a stable equilibrium with high satisfaction and controlled costs.

Figure 4.

Resource allocation performance under aggressive-dominant tenant strategies (synthetic workload).

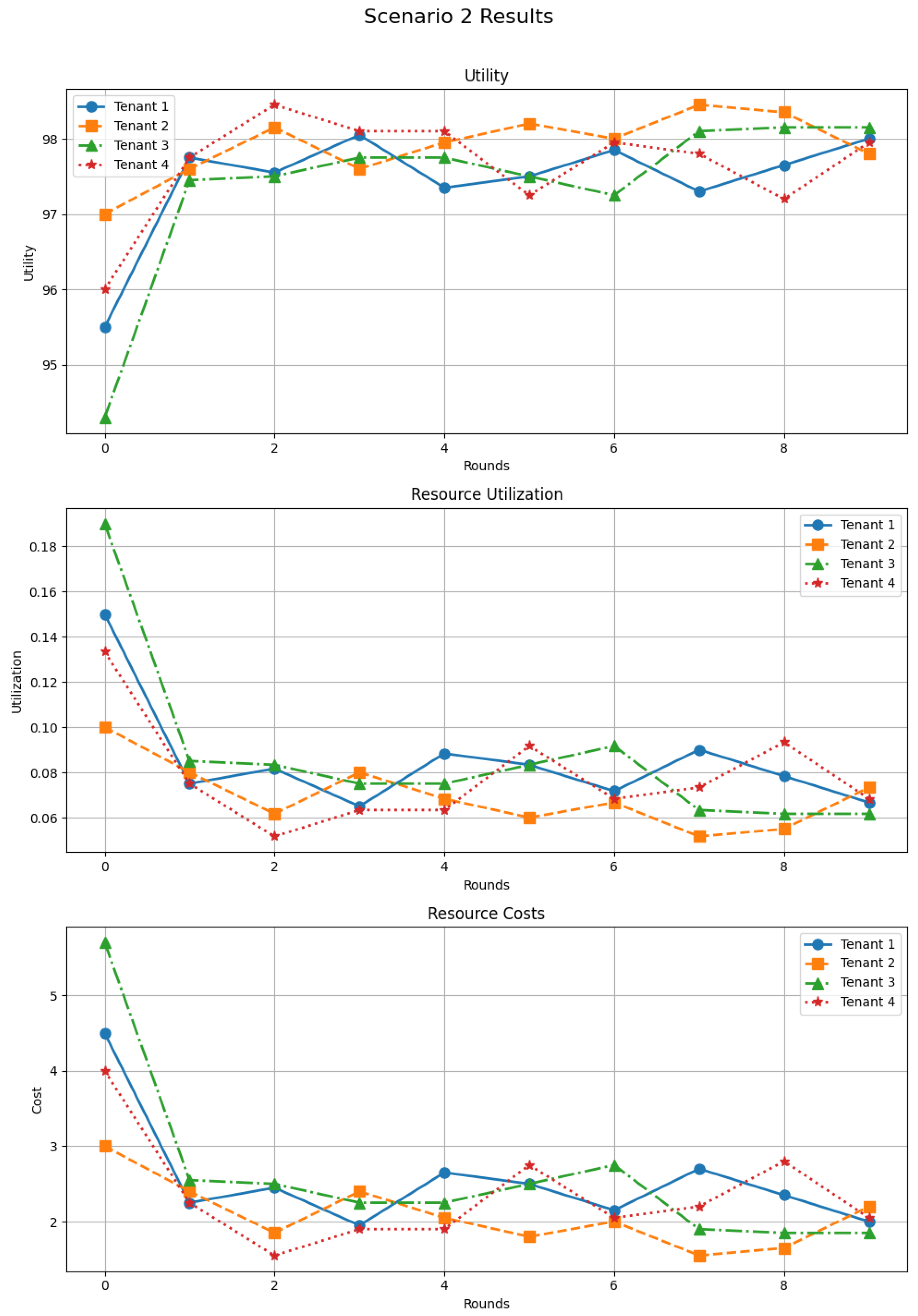

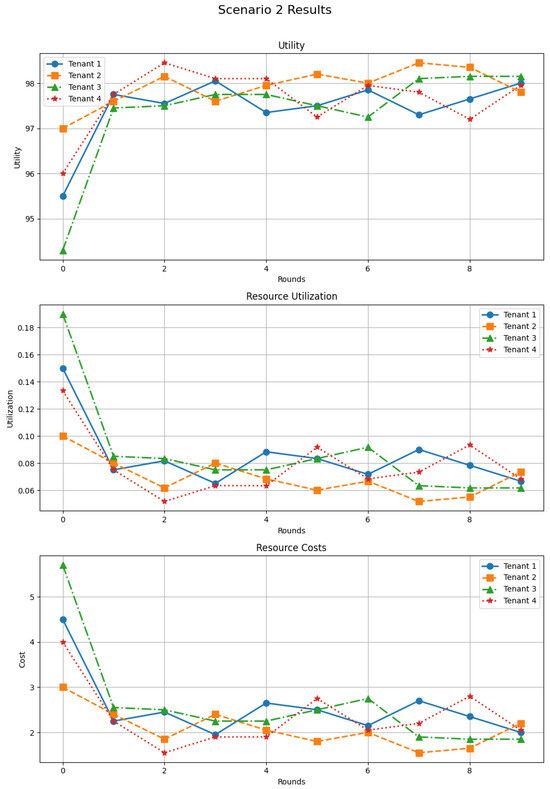

5.2.2. Scenario 2—Moderate-Balanced Results

Scenario 2 (Figure 5) exhibits even more regular behavior. Utilities start at reasonably high values and rapidly converge towards a narrow band around 98. Resource utilization remains moderate (below 10%) and costs, initially slightly higher (4–5 units), rapidly stabilize near 2 units. In this balanced setting, DSGTA maintains efficiency and fairness: no tenant is starved, no tenant monopolizes the shared pool, and all tenants converge towards similar utilities and costs.

Figure 5.

Resource allocation efficiency in moderate-balanced tenant environments (synthetic workload).

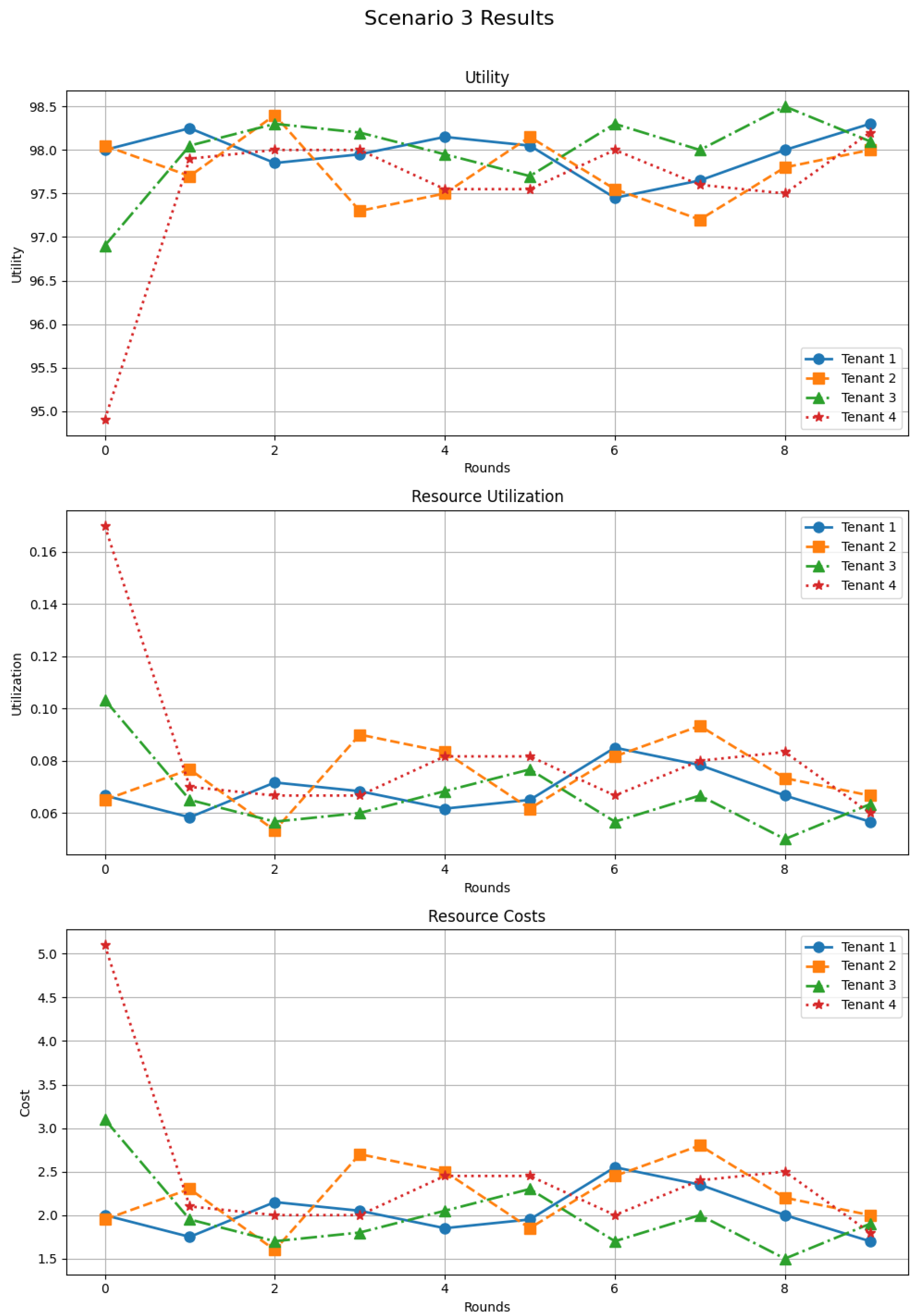

5.2.3. Scenario 3—Conservative-Dominant Results

The outcomes of Scenario 3 are presented in Figure 6. Utilities start slightly below their eventual plateau (around 95–97) and converge towards 98 despite the predominance of conservative behaviors. An initially aggressive tenant causes a short-lived spike in utilization (around 16%), which quickly normalizes to values in the 6–8% range. Costs show a similar pattern: they begin around 5 units for the most demanding tenant and gradually decrease to about 1.5–2.5 units. These results underline the adaptability of DSGTA: even when most tenants are reluctant to request resources, the model is able to rebalance allocations and maintain high satisfaction without inducing wasteful over-provisioning.

Figure 6.

Evaluation of conservative-dominant tenant resource management (synthetic workload).

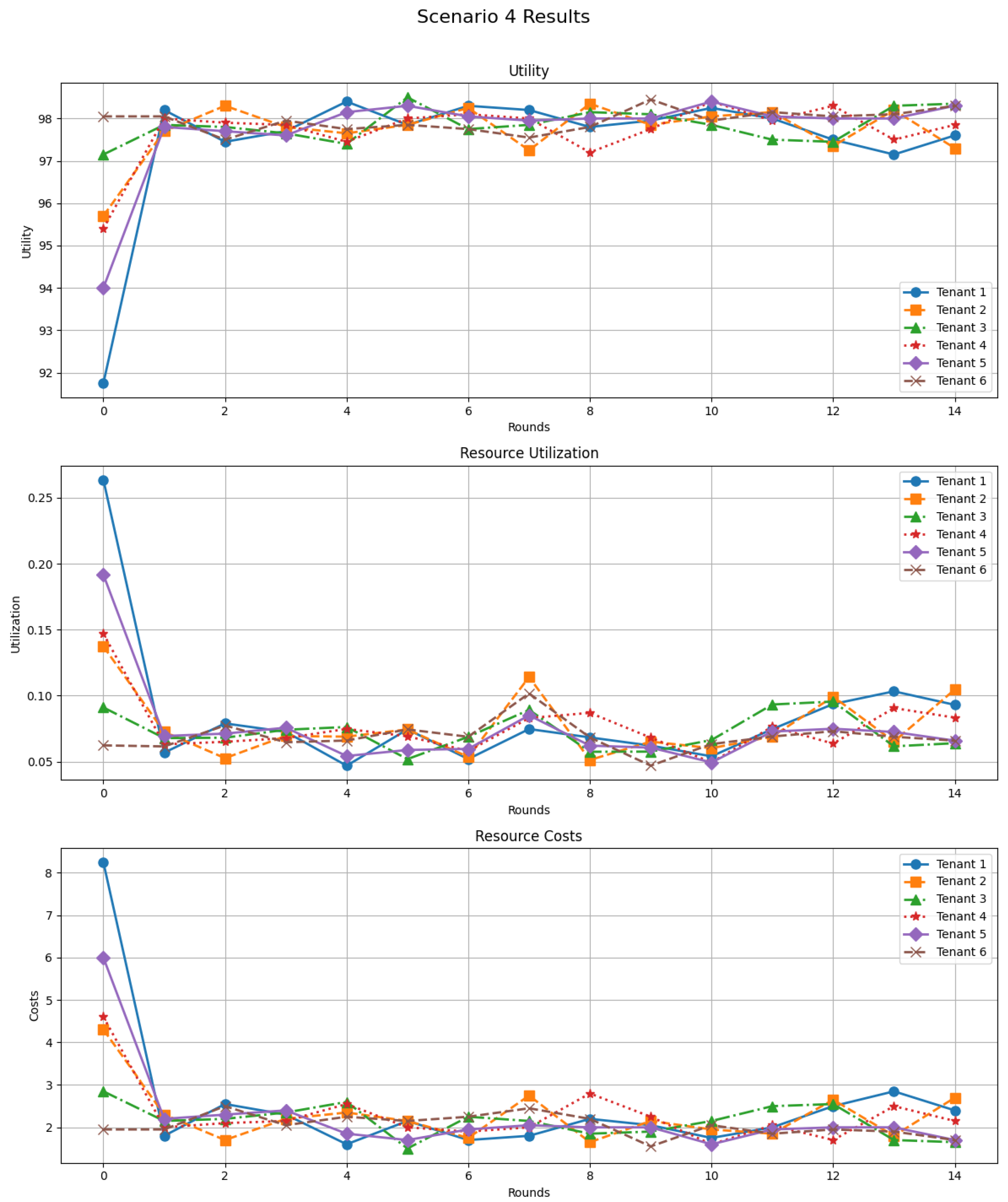

5.2.4. Scenario 4—Complex Scenario Results

Figure 7 depicts the behavior of the complex multi-strategy Scenario 4. At the beginning of the game, utilities are heterogeneous (low-to-mid 90s), utilization is relatively high, and costs are around 7–8 units. After the first few rounds, utilities converge towards approximately 98 for all tenants, while utilization becomes more balanced (5–10%) and costs drop to about 2 units. This scenario demonstrates that the DSGTA framework retains its stability and fairness properties when the number of tenants increases, and strategies are strongly heterogeneous.

Figure 7.

Resource allocation adaptability in complex mixed-strategy multi-tenant clouds (synthetic workload).

5.3. Real-World Trace-Based Evaluation

To complement the synthetic scenarios and assess practical relevance, we now evaluate DSGTA on a real multi-tenant workload built from Google Cluster traces. This trace-driven study allows us to verify that the dynamic game-theoretic controller remains effective and scalable when confronted with heterogeneous, bursty resource demands observed in an operational cloud environment.

5.3.1. Dataset Description

We rely on the Google 2019 Cluster Sample dataset [31], a publicly available trace collected from Google’s Borg cluster management system and hosted on the Kaggle platform. This dataset contains anonymised records describing the execution of tasks and jobs in a large-scale, multi-tenant compute cluster [32].

Each record in the trace includes, among others, temporal information (start and end times), a user identifier, and a structured description of the resources requested by the job or collection, in particular CPU and memory. In our setting, we interpret the user field as a tenant identifier, and we focus on the requested CPU and memory as the primary resource demands. This allows us to view the trace as a multi-tenant workload where different users compete for shared cluster resources over time.

To align the trace with the round-based structure of the DSGTA framework, we discretise time into non-overlapping slots of fixed duration. Each job or collection is assigned to the slot corresponding to its start time. For every pair (tenant, time slot), we then aggregate the requested CPU and memory over all jobs submitted by that tenant during the slot. This yields, for each tenant, a time series of CPU and memory demands that naturally plays the role of the exogenous demand profile in our game-theoretic model.

Since the trace contains a large number of tenants with highly heterogeneous activity levels, we concentrate on the most active ones in order to build clear, interpretable scenarios. We rank tenants by their cumulative CPU demand over the observation period and select a small set of “heavy” tenants to instantiate the four scenarios described below. For these selected tenants, the aggregated demands are arranged into matrices where rows correspond to tenants and columns to consecutive time slots. These matrices provide realistic, trace-driven demand patterns that preserve the heterogeneity, burstiness, and multi-tenant nature of the original Google workload, while remaining compatible with the dynamic and stochastic game-theoretic framework of DSGTA.

In all Google Cluster trace–driven experiments, time is discretized into fixed slots of duration s (5 min). Tenant resource requests are generated by scaling their trace-derived baseline demands with three discrete strategy factors: for aggressive behavior, for moderate behavior, and for conservative behavior. SLA constraints are modelled through tenant-specific performance strictness levels in the range and associated penalty coefficients between 10 and 20, which jointly determine the severity of SLA violations in the utility function.

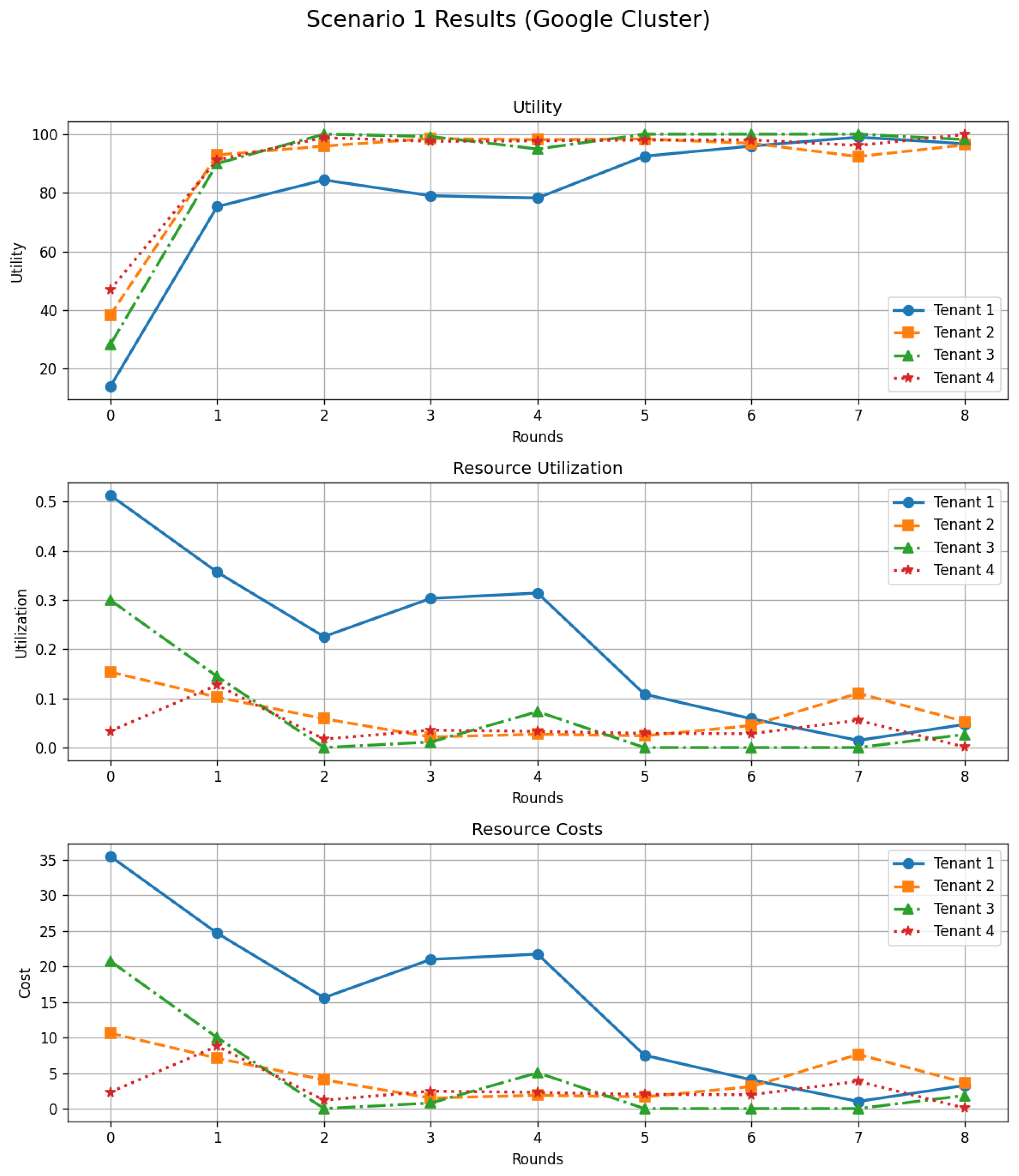

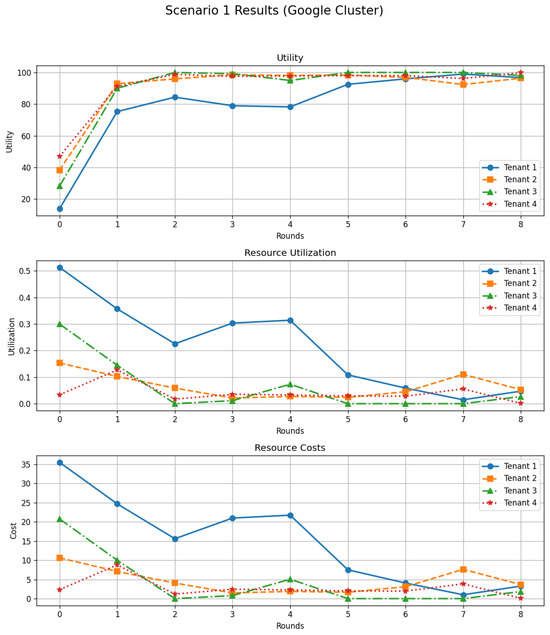

5.3.2. Scenario 1—Mixed Tenant Strategies Under Google Cluster Workload

In the first trace-driven scenario, we consider the four most CPU-intensive tenants extracted from the Google Cluster dataset. The aim is to reproduce, on real traces, the aggressive-dominant configuration studied previously with synthetic workloads: two tenants start with highly aggressive resource-request strategies, one tenant adopts a moderate behavior, and the remaining tenant follows a conservative strategy.

At each decision round, the demand of tenant i is obtained by scaling its baseline CPU and memory requirements (derived from the trace) by a strategy factor: aggressive tenants request substantially more than their historical demand, moderate tenants slightly over-provision, and conservative tenants stay closer to their baseline needs. The cloud provider exposes a fixed amount of CPU and memory, dimensioned from the 90th percentile of the aggregate demand over all four tenants, so that the system may occasionally experience moderate contention but remains globally provisioned.

Given the per-round requests, the DSGTA controller allocates CPU and memory proportionally across tenants, ensuring that no tenant receives more than it requested and that the total capacity is not exceeded. The resulting trajectories for the four tenants are depicted in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Scenario 1 results with Google Cluster traces: per-tenant trajectories of utility, resource utilization, and resource costs over successive rounds.

The utility curves show a clear transient phase followed by a rapid convergence. At the initial round, utilities are heterogeneous: the two aggressive tenants experience relatively low utility due to high costs and occasional penalties, whereas the moderate and conservative tenants achieve intermediate levels of satisfaction. After one to two rounds, all utilities sharply increase and converge towards a narrow band around 95–100, with only small fluctuations afterwards. This behavior reflects the dynamic adaptation of strategies: tenants that observe low utility in a given round tend to switch to a more aggressive stance, while those with very high utility progressively move towards more conservative requests. The repeated interaction thus steers the system towards a regime where additional requested resources no longer compensate their cost, which is consistent with a Nash-like equilibrium of the non-cooperative game.

The utilization panel of Figure 8 indicates that, although the system starts with relatively high usage for some tenants, the effective share of capacity allocated to each of them decreases and stabilizes over time. This is due to the fact that, as utilities improve, tenants naturally reduce their over-provisioning and settle on requests that are closer to their effective needs. As a consequence, the overall utilization remains moderate, and no tenant monopolizes the shared resources.

Finally, the cost trajectories exhibit a complementary trend: the most aggressive tenant initially incurs a very high cost, which declines steadily as its strategy is adjusted in response to the observed utility. The other tenants also see their costs decrease over the rounds, often stabilizing near zero when their requests become well aligned with their demand and the available capacity. Taken together, these results confirm that, even under a realistic and heterogeneous workload extracted from the Google Cluster trace, DSGTA can coordinate mixed tenant strategies and drive the system towards a stable regime that balances utility, resource utilization, and cost fairly.

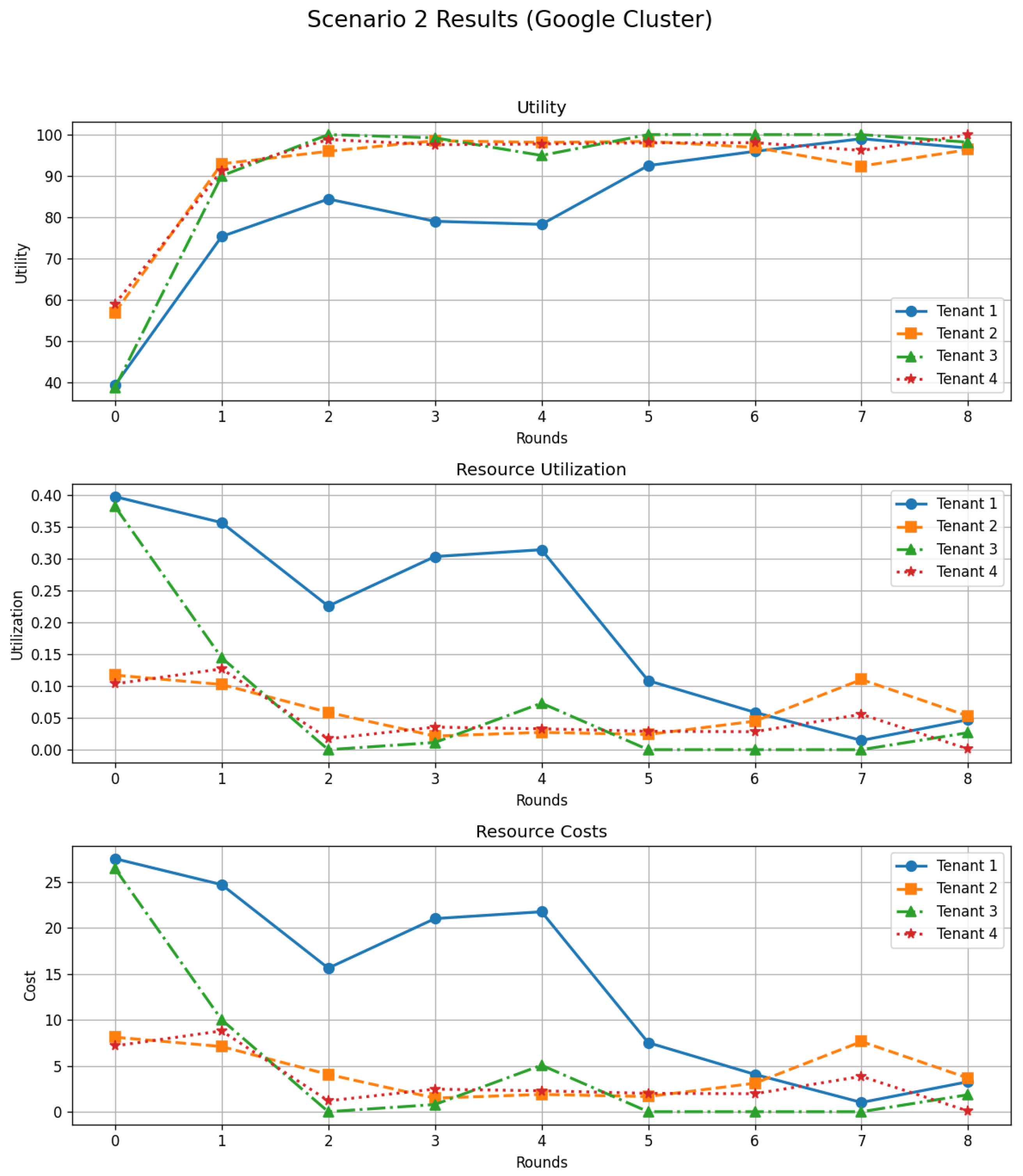

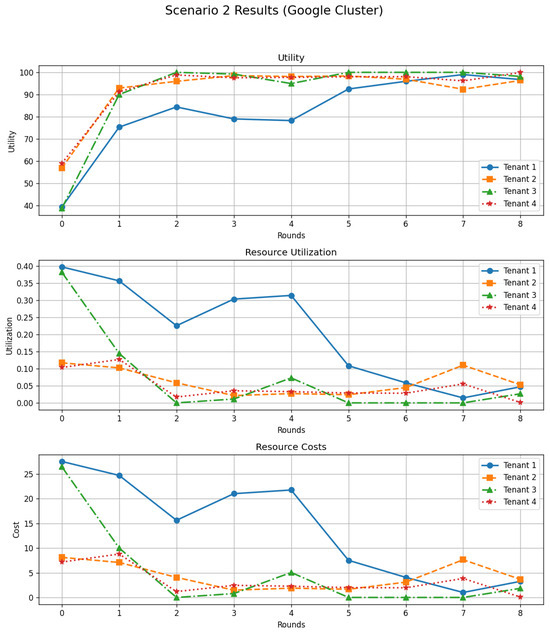

5.3.3. Scenario 2—Homogeneous Moderate Strategies Under Google Cluster Workload

In the second trace-driven scenario, all four selected tenants initially adopt a moderate request strategy. Unlike Scenario 1, where the system starts in an aggressive-dominant configuration, here, no tenant deliberately over-provisions by a large factor. The goal of this scenario is to observe how DSGTA behaves when tenants are symmetric at the outset and only adapt their strategies based on the utilities observed over time.

As in Scenario 1, each tenant’s baseline CPU and memory demands are derived from the Google Cluster trace, and the cloud provider exposes a fixed pool of resources sized from the upper quantiles of the aggregate demand. At each round, tenants scale their baseline requirements according to their current strategy (moderate, possibly evolving towards aggressive or conservative), and DSGTA applies a proportional allocation subject to global capacity constraints. Utilities, costs, and effective utilization are then computed for every tenant and fed back into the strategy-update mechanism for the next round.

The utility trajectories in Figure 9 exhibit a short transient phase followed by a rapid and stable convergence. At the first round, utilities lie between approximately 40 and 60, reflecting a mix of mild under-provisioning and non-negligible costs. After one or two iterations, however, all tenants see their utilities increase sharply, converging towards values close to 95–100. The convergence is smoother than in Scenario 1, since no tenant starts in an extremely aggressive state: the adjustment primarily consists of fine-tuning around the moderate baseline rather than correcting large over-provisioning. Once utilities enter the high range, tenants tend to switch progressively towards more conservative strategies, stabilizing around a configuration where marginal gains from additional resources are compensated by their cost.

Figure 9.

Scenario 2 results with Google Cluster traces: per-tenant trajectories of utility, resource utilization, and resource costs over successive rounds.

The middle panel of Figure 9 shows the evolution of resource utilization for each tenant. Initially, one tenant consumes a relatively high share of the available capacity, while the others use smaller fractions. As the system evolves, these utilizations decrease and become more balanced: tenants gradually reduce their requested resources, leading to lower individual shares and preventing persistent monopolization of the shared pool. Overall, the system operates with moderate utilization levels, indicating that DSGTA avoids chronic under-utilization and sustained overload in this homogeneous moderate regime.

Finally, the cost curves follow a pattern consistent with the utilities and utilization. The tenant that initially consumes the largest share of capacity incurs the highest cost at the beginning of the process. As its strategy adapts, this cost declines steadily, while the other tenants also see their costs reduced as they move towards less demanding configurations. After a few rounds, costs are close to zero for most tenants, confirming that the combination of moderate initial strategies and DSGTA’s dynamic feedback encourages resource requests that are closely aligned with effective needs.

In summary, Scenario 2 illustrates that, when tenants start from homogeneous moderate strategies under a realistic Google Cluster workload, DSGTA quickly drives the system towards a stable and fair operating point. Utilities converge near their maximum, resource utilization remains controlled, and costs are significantly reduced, demonstrating that the proposed model is effective in more balanced, symmetric settings.

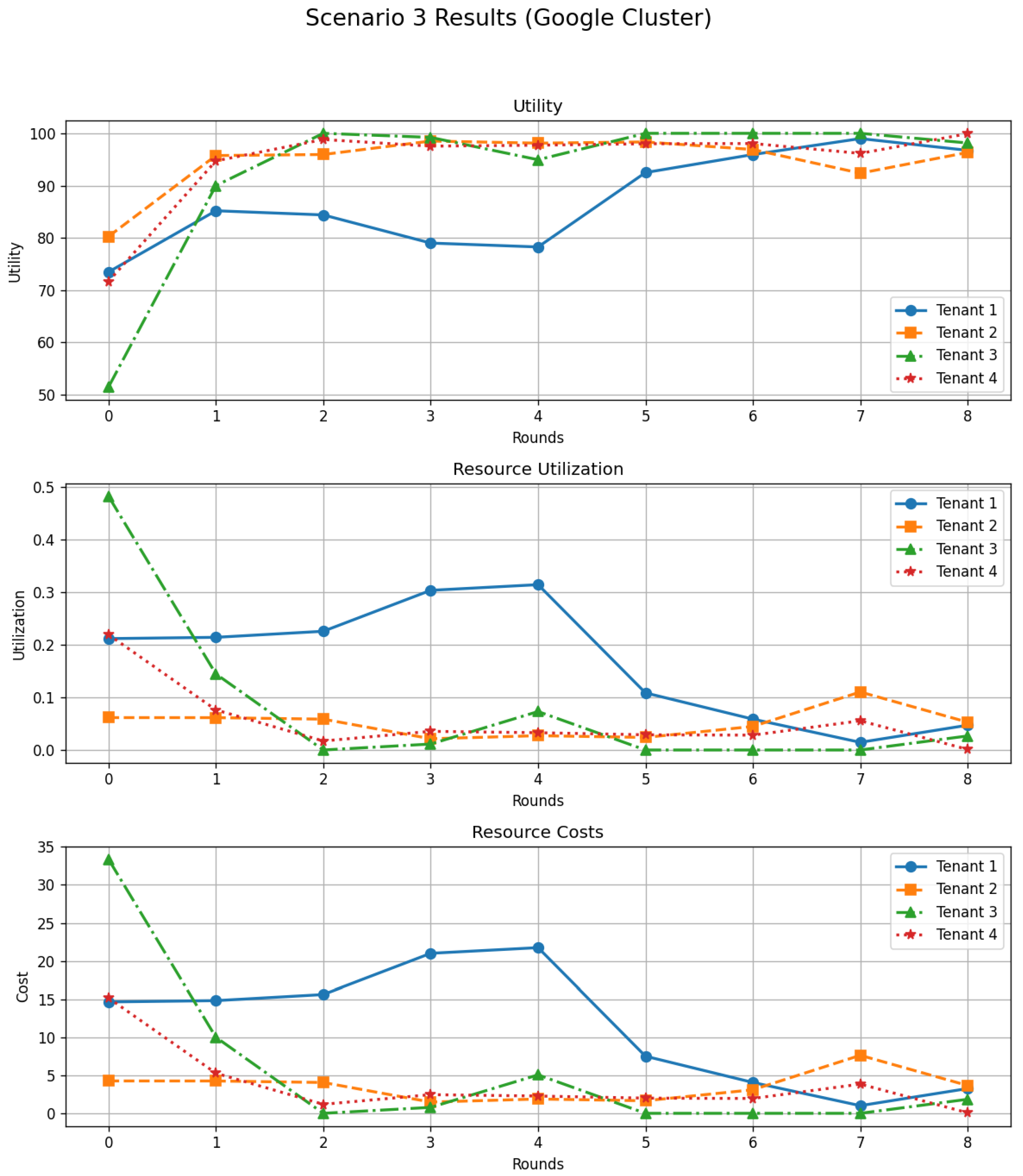

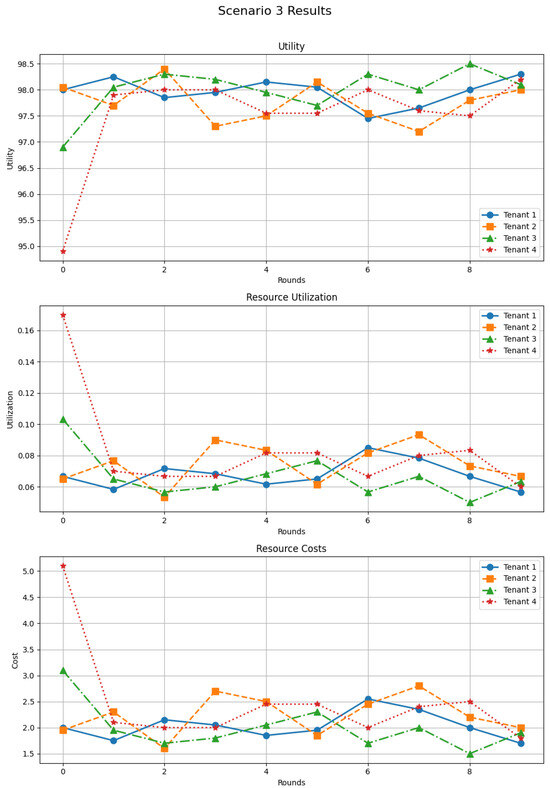

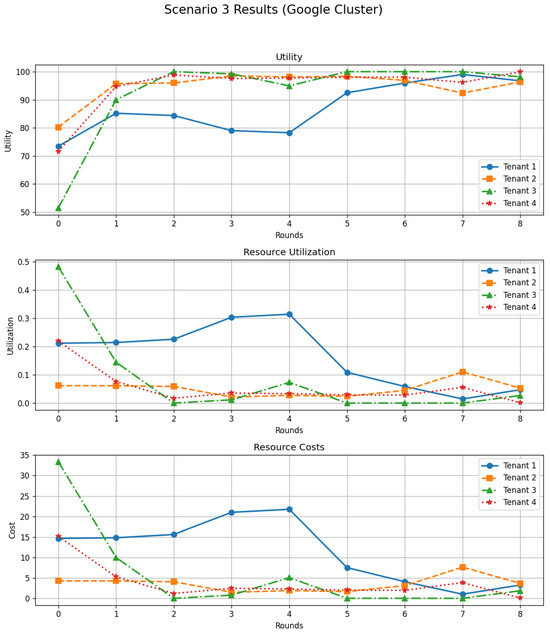

5.3.4. Scenario 3—Conservative-Dominant Strategies Under Google Cluster Workload

In the third trace-driven scenario, the system starts from a configuration where conservative strategies dominate: most tenants initially request resources close to, or slightly below, their baseline demand, while one tenant behaves more aggressively and another adopts an intermediate (moderate) stance. This setting is intended to emulate an environment in which the majority of tenants are cautious and risk under-provisioning, whereas a minority attempts to secure more resources in order to improve performance.

As in the previous scenarios, baseline CPU and memory demands are extracted from the Google Cluster trace and aggregated per tenant and time slot. At each round, tenants scale these baselines according to their current strategy (conservative, moderate, or aggressive), and the DSGTA controller performs a proportional allocation subject to the fixed cluster capacity. Utilities, costs, and utilization are computed for each tenant and fed back into the dynamic strategy-update rule.

The top panel of Figure 10 shows that initial utilities are heterogeneous. Some tenants, particularly those that start from under-provisioned or highly imbalanced requests, experience relatively low utility due to penalties for SLA violations or to inefficient cost–performance trade-offs. Others obtain intermediate levels of satisfaction when their conservative requests happen to match the available capacity. After a small number of rounds, however, the utilities of all tenants increase sharply and converge towards a narrow band around 95–100, with only minor oscillations. Tenants suffering from low utility in early rounds tend to move towards more aggressive strategies, securing additional resources and reducing SLA penalties, whereas tenants enjoying very high utility progressively switch to more conservative strategies to avoid unnecessary costs. This mutual adjustment leads to a stable operating point that is again consistent with a Nash-like equilibrium of the underlying non-cooperative game.

Figure 10.

Scenario 3 results with Google Cluster traces: per-tenant trajectories of utility, resource utilization, and resource costs over successive rounds.

The evolution of resource utilization, depicted in the middle panel of Figure 10, reflects this adaptation process. Initially, one tenant consumes a relatively high fraction of the total capacity while others remain at very low utilization levels, characteristic of a conservative-dominant state with one heavier user. As strategies evolve, utilizations become more balanced and eventually decrease, indicating that tenants no longer over-request resources as aggressively as in the transient phase. The system therefore avoids persistent under-utilization and long periods of strong contention.

The bottom panel of Figure 10 illustrates the corresponding behavior of resource costs. At the beginning of the scenario, the most demanding tenants incur substantial costs, while conservative tenants pay very little but may suffer from performance penalties reflected in their utility. Over successive rounds, the cost of heavily consuming tenants decreases as they reduce their requests in response to the feedback provided by DSGTA, and the costs of other tenants also tend towards low values as their strategies align more closely with their effective needs and the cluster capacity.

Overall, Scenario 3 demonstrates that DSGTA can effectively regulate a system that initially operates in a conservative-dominant regime with a small number of more demanding tenants. Even under a realistic workload derived from Google Cluster traces, the proposed dynamic and stochastic game-theoretic framework succeeds in driving all tenants towards a stable configuration that balances utility, resource utilization, and cost fairly and efficiently.

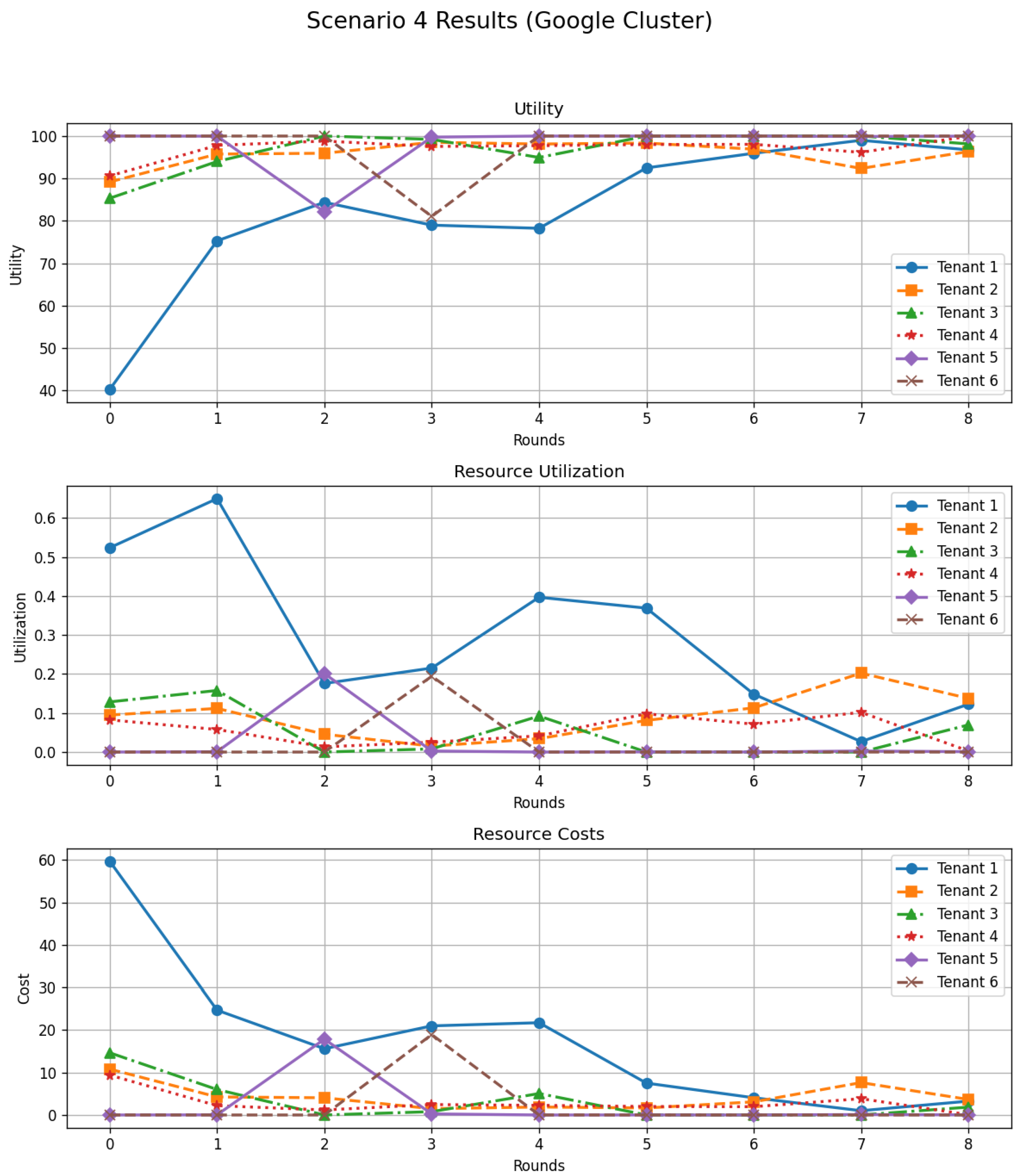

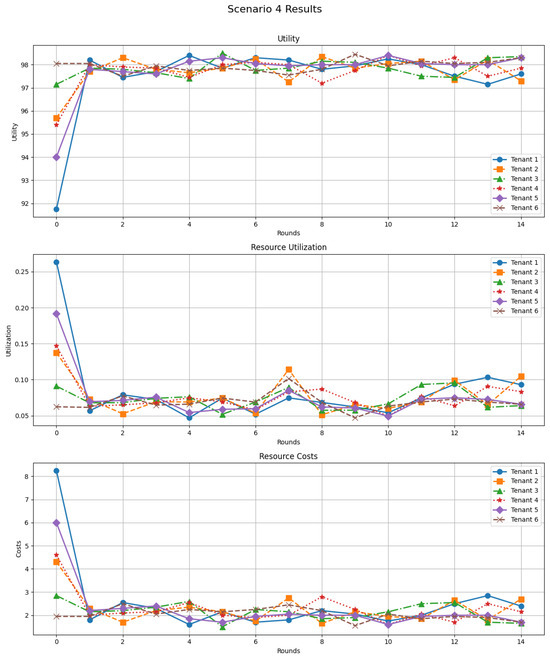

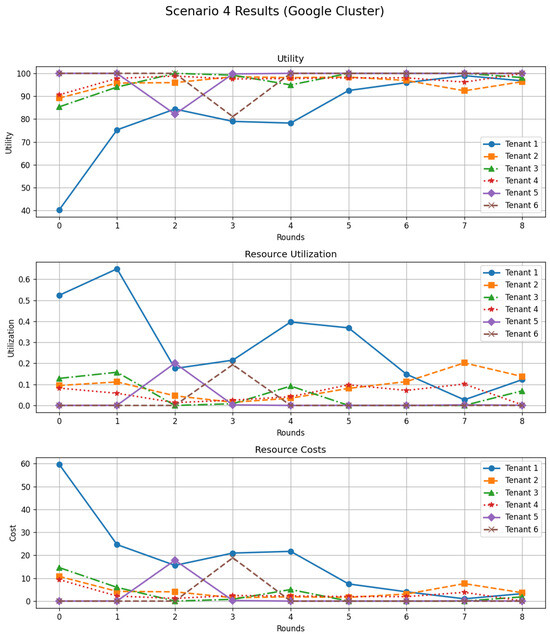

5.3.5. Scenario 4—Heterogeneous Tenants with Dynamic Capacity and SLA Constraints

The fourth trace-driven scenario increases the level of heterogeneity and scale by considering six tenants instead of four, each characterized by a distinct profile combining an initial strategy (aggressive, moderate, or conservative), a specific SLA strictness level, and a different penalty for SLA violations. This setting is designed to emulate a realistic multi-tenant environment where users have heterogeneous QoS targets and sensitivity to violations.

Baseline CPU and memory demands are again obtained from the Google Cluster dataset and aggregated per tenant and time slot. In contrast to the previous scenarios, the cluster capacity is made dynamic: at each round, the available CPU and memory are set as a fixed margin over the total baseline demand observed in that round. This models an elastic cloud provider that adapts its provisioned capacity to the current workload, while still exposing limited resources at each decision step.

For each tenant i and round t, the requested resources are computed by scaling the baseline demand with the factor associated with the tenant’s current strategy. The DSGTA controller applies a proportional allocation under the dynamic capacity, and we evaluate utility, cost, SLA satisfaction, and effective utilization using an SLA-aware utility function: a tenant receives a non-zero penalty whenever the achieved performance ratio falls below its SLA strictness threshold. Tenants then update their strategies based on the utility observed in the previous round, moving towards more aggressive behavior when utility is low and towards more conservative behavior when utility is very high.

Figure 11 shows the evolution of utility, utilization, and cost for the six tenants. The utility curves reveal a noticeable heterogeneity at the beginning of the scenario: some tenants start with relatively low utility, especially those with strict SLAs or initially aggressive strategies that incur high costs and penalties, while others achieve higher satisfaction thanks to more balanced configurations. After a few rounds, however, all utilities converge towards a high plateau around 95–100, despite the diversity in SLA parameters and initial strategies. This demonstrates that DSGTA is able to harmonise the behavior of tenants with heterogeneous QoS requirements under a dynamic capacity regime.

Figure 11.

Scenario 4 results with Google Cluster traces: per-tenant trajectories of utility, resource utilization, and resource costs over successive rounds for six heterogeneous tenants under dynamic capacity and SLA constraints.

The middle panel of Figure 11 depicts the corresponding resource utilization. Initially, one tenant consumes a large share of the available capacity, while the others exhibit much lower utilizations. As the game unfolds and strategies adapt, these shares become more balanced and progressively decrease, indicating that tenants reduce unnecessary over-provisioning once the marginal benefit of additional resources is outweighed by their cost and potential penalties. The system therefore succeeds in avoiding sustained resource congestion and long-term under-utilization, even when capacity fluctuates over time.

Finally, the cost trajectories (bottom panel) highlight the impact of the dynamic capacity and SLA-aware pricing. The most aggressive tenant initially pays a very high cost, which decreases steadily as its strategy is adjusted in response to the low utility observed in early rounds. Tenants with stricter SLAs and high penalties also see their costs and penalties diminish as DSGTA steers them towards strategies that better match their effective needs and the dynamically provisioned capacity. After several rounds, most tenants operate in a regime where costs are low, and SLA violations become rare, despite the heterogeneous SLAs and the variability of the underlying Google workload.

Overall, Scenario 4 confirms that the proposed dynamic and stochastic game-theoretic framework scales to a larger and more heterogeneous tenant population, and remains effective when resource capacity and SLA constraints vary over time. DSGTA is able to reconcile high utility, controlled utilization, and low cost across tenants with diverse strategies and service requirements.

5.3.6. Scalability with Large Tenant Populations

To further assess the scalability of DSGTA under realistic and heterogeneous conditions, we perform an additional experiment on the Google Cluster traces in which the number of active tenants is progressively increased. Starting from the full set of tenants extracted from the trace, we draw random subsets of size . For each value of K, we instantiate a variant of Scenario 4: tenants have heterogeneous SLA targets and penalties, capacity is dynamically adjusted to the current aggregate demand with occasional demand spikes, and the DSGTA dynamics are run for several rounds. Each configuration is repeated over multiple random draws, and we record four aggregate metrics at the first decision round (“initial”) and at the last decision round (“final”): mean utility, fairness index, mean cost, and SLA satisfaction rate.

Table 2 summarizes the results averaged over all runs. Across all values of K, DSGTA consistently improves the mean utility between the initial and final rounds; for instance, the mean utility increases from 86.75 to 97.79 for , and from about 80 to 85 for K between 150 and 500. The fairness index also improves and remains close to 0.9 or higher, even when the number of tenants reaches 500, indicating that resources and benefits are shared in a nearly egalitarian way despite the heterogeneity in SLAs and penalties. At the same time, the mean cost per tenant decreases systematically, while the SLA satisfaction rate increases by several points for all K (e.g., from 0.78 to 0.97 for , and from around 0.67 to more than 0.70 for large K).

Table 2.

Scalability evaluation with heterogeneous tenants and SLAs: initial vs final round metrics for different numbers of tenants K (averaged over multiple runs).

These results show that the dynamic and stochastic game-theoretic controller preserves its desirable properties when scaled from a few tens to several hundreds of tenants, thereby supporting the practical scalability claims of DSGTA.

5.4. Discussion

The combined synthetic and trace-driven experiments confirm the effectiveness and applicability of the proposed game-theoretic model in a wide variety of strategic situations. Across all scenarios, DSGTA rapidly drives the system towards stable configurations characterized by high utilities, balanced resource utilization, and reduced costs, even in the presence of strong competition for resources or conservative consumption patterns. The convergence of utilities and the consistently high fairness indices highlight the ability of the model to share benefits equitably among tenants with different behaviors and requirements.

The real-world experiments based on Google Cluster traces reinforce these conclusions. They show that the qualitative behavior observed in controlled synthetic settings persists under realistic, bursty workloads, and that DSGTA remains robust when tenants exhibit heterogeneous SLAs and penalty structures. Moreover, the large-scale evaluation with up to 500 tenants demonstrates that the controller maintains good performance and fairness properties when the system size increases, while keeping mean costs and SLA violation rates under control.

Taken together, these findings indicate that DSGTA is a promising candidate for deployment in real multi-tenant cloud systems. By jointly considering strategic adaptation, stochastic workload variations and fairness, the proposed model can support resource allocation policies that are efficient, economically viable, and robust to diverse tenant behaviors at scale.

6. Comparative Evaluation

To critically evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of our DSGTA model, we compare it against two representative baseline mechanisms that are widely discussed in recent cloud resource–allocation literature: a Static Game-Theoretic Allocation (SGTA) scheme [33] and a Dynamic Pricing-Based Allocation (DPBA) scheme [34]. The comparison is conducted first on the synthetic scenarios introduced in Section 5, and then on the Google Cluster trace to verify that the observed trends persist under real workloads.

The SGTA model [33] adopts a conventional static non-cooperative game in which tenants submit resource requests once and for all. Resource allocation is then computed based on these fixed strategies, with no possibility for tenants to revise their decisions in response to observed performance. This assumption of time-invariant resource requirements prevents SGTA from capturing evolving operational conditions or strategic adaptations, which may lead to suboptimal allocations, unnecessarily high costs, and lower overall system efficiency.

Conversely, the DPBA model [34] employs a dynamic pricing mechanism in which resource prices are periodically adjusted according to aggregate demand. This endows DPBA with a certain degree of responsiveness to workload fluctuations. However, DPBA does not explicitly model strategic interactions between tenants, nor does it account for stochastic variations in workload and SLA penalties in the same way as DSGTA. As a result, DPBA may still fall short of maximising tenant utility, particularly in highly dynamic, multi-tenant environments.

For a fair comparison, all three approaches are evaluated under identical capacity constraints and workload profiles. SGTA and DPBA are re-implemented using the same utility and cost functions as DSGTA, and their configuration parameters (such as pricing sensitivity in DPBA) are empirically tuned on preliminary runs. Each method is then evaluated in terms of three aggregate indicators: average tenant utility, average resource utilization, and average resource costs across the decision rounds.

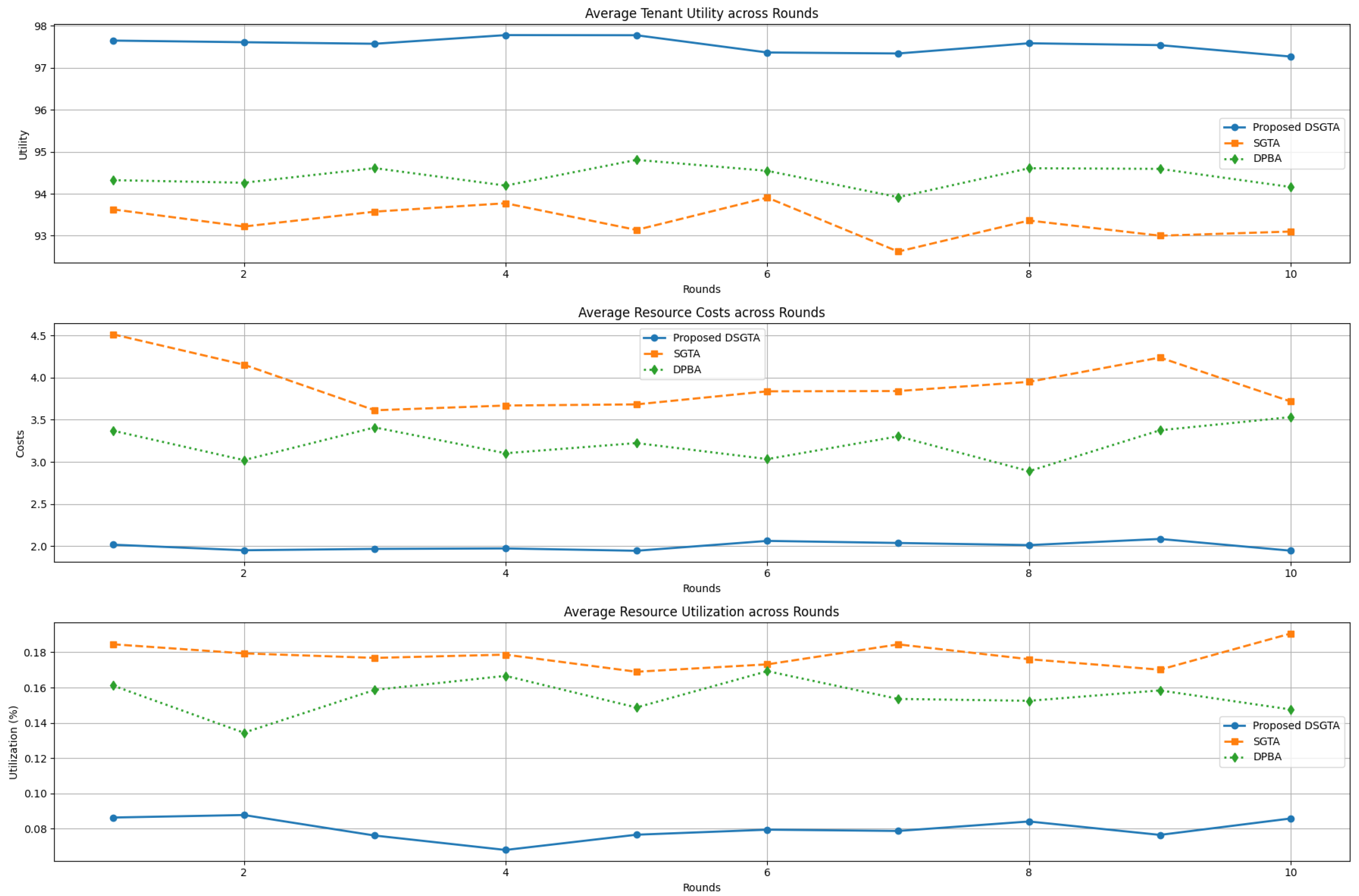

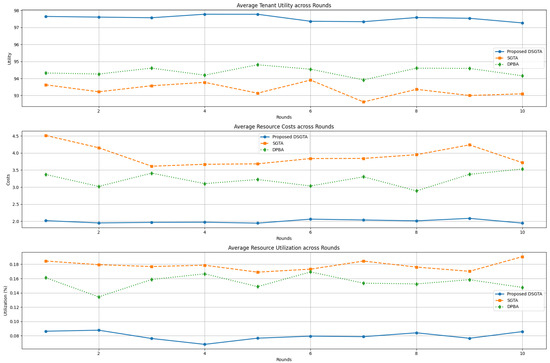

On the synthetic scenarios, the analysis of tenant utility (top panel of Figure 12) indicates a clear and persistent advantage for DSGTA. After the transient rounds, DSGTA delivers utilities close to 98, whereas SGTA saturates in the low 90s and DPBA in the mid 90s. These gaps reflect the additional benefit of explicitly modeling repeated strategic interactions and stochastic events: DSGTA allows tenants to adapt their strategies over time, while SGTA is locked into its initial configuration and DPBA reacts only through price updates.

Figure 12.

Comparative performance of DSGTA, SGTA, and DPBA on the synthetic workload: average utility, average cost, and average utilization across rounds.

The cost curves further highlight the economic efficiency of DSGTA. Throughout the simulated horizon, DSGTA maintains the lowest average cost, stabilizing around two cost units once the system has converged. SGTA, by contrast, incurs the highest costs due to its inability to correct over-provisioning decisions. DPBA achieves intermediate cost levels, reflecting some savings from dynamic pricing but still lacking the full strategic coordination provided by DSGTA.

A similar pattern emerges for resource utilization (bottom panel). DSGTA converges to moderate utilization levels (about 6–9%), suggesting that resources are used efficiently without persistent overloading. SGTA exhibits consistently higher utilization, which indicates that tenants often request and receive more resources than strictly necessary. DPBA again lies in between, with utilization around 14–16%. Overall, these results show that DSGTA achieves the best trade-off between high utility, low cost, and controlled utilization in the synthetic setting.

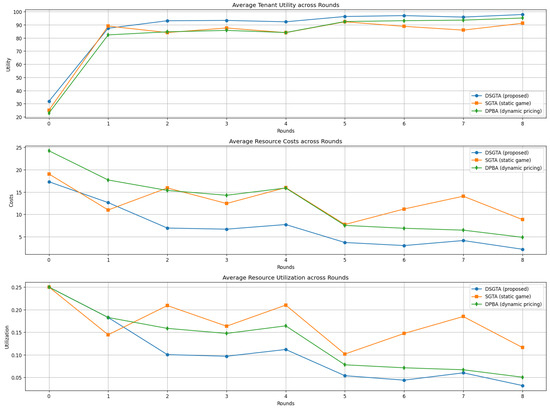

To verify that these conclusions hold under realistic workloads, we repeat the comparative experiment using the Google Cluster trace as input. In this case, each method receives the same trace-derived demand profiles and is evaluated with the same performance metrics. The results, summarized in Figure 13, confirm the superiority of DSGTA in the trace-driven setting. The proposed model again reaches the highest average utilities, close to their theoretical maximum, while SGTA and DPBA remain a few points below.

Figure 13.

Comparative performance of DSGTA, SGTA, and DPBA on the Google Cluster trace: average utility, average cost, and average utilization across rounds.

In terms of costs, DSGTA systematically yields the lowest average values, even when workload bursts and heterogeneous SLAs are present in the trace. SGTA remains the most expensive scheme, and DPBA only partially closes the gap thanks to its pricing mechanism. Average utilization under DSGTA is also more stable and avoids the pronounced peaks observed with SGTA and, to a lesser extent, DPBA. This indicates that DSGTA is able to absorb workload variability and tenant heterogeneity without resorting to persistent over-provisioning.

Taken together, the synthetic and trace-based comparisons underscore the critical improvements offered by our DSGTA approach. By combining repeated strategic interactions, stochastic modeling, and fairness-aware utilities, DSGTA consistently delivers higher tenant satisfaction, lower costs, and more efficient resource utilization than SGTA and DPBA. The fact that these advantages persist on a real production trace strengthens the claim that DSGTA is a practically viable solution for dynamic multi-tenant cloud environments characterized by frequent demand fluctuations.

Statistical Validation of the Comparative Results

To assess whether the performance gaps observed in Figure 12 and Figure 13 are statistically meaningful, we carried out a set of paired statistical tests on the Google Cluster comparison. For each metric (utility, cost, and utilization), we considered the sequence of per-round averages for the three models (DSGTA, SGTA, and DPBA) and applied paired Student t-tests between DSGTA and each baseline, as well as a Friedman test to jointly compare the three methods under a repeated-measures setting.

Table 3 reports the test statistics and p-values obtained on the per-round averages. For tenant utility, the paired tests show that DSGTA significantly outperforms SGTA and DPBA (DSGTA vs. SGTA: , ; DSGTA vs. DPBA: , ). For resource costs, the t-statistics are negative (DSGTA vs. SGTA: , ; DSGTA vs. DPBA: , ), confirming that DSGTA achieves significantly lower average costs. A similar pattern holds for utilization (DSGTA vs. SGTA: , ; DSGTA vs. DPBA: , ), indicating that DSGTA avoids persistent over-utilization of resources. In all cases, the Friedman tests also reject the null hypothesis of identical distributions among the three models for a given metric (all ).

Table 3.

Paired t-tests and Friedman tests comparing DSGTA with SGTA and DPBA on the Google Cluster workload (per-round averages).

We further repeated the analysis on all tenant×round observations instead of per-round averages. The resulting p-values are even smaller (for example, utility: for DSGTA vs. SGTA and for DSGTA vs. DPBA; cost: and , respectively), and the Friedman tests again yield highly significant results (all ). This confirms that the superiority of DSGTA over SGTA and DPBA in terms of higher utility, lower costs, and more controlled utilization is statistically robust and not an artifact of random fluctuations in the simulation.

7. General Discussion and Limitations

The efficient allocation of resources in multi-tenant cloud computing environments remains a challenging problem due to the dynamic and often unpredictable nature of user demands. Static resource allocation models lack adaptability, resulting in persistent under- or over-provisioning, while overly simplistic dynamic methods fail to fully capture strategic tenant interactions and heterogeneous service requirements. The proposed DSGTA model was designed precisely to bridge this gap by combining non-cooperative games, repeated interactions, and stochastic state transitions within a unified framework that explicitly accounts for utilities, costs, SLA penalties, and fairness.

A key conceptual contribution of this work is the two-fold modeling approach that separates the theoretical game-theoretic foundations from the dynamic and stochastic operational layer. The theoretical model formalises tenants as strategic players endowed with utility functions that trade off performance gains, monetary costs, and SLA penalties. Nash equilibrium provides a principled notion of strategic stability, while the Shapley value introduces an explicit fairness criterion based on marginal contributions to the global outcome. Building on this foundation, the dynamic and stochastic layer implements a repeated-game mechanism in which tenants iteratively adjust their strategies based on local feedback, and a stochastic game view that captures random workload variations and heterogeneous SLA states. This decomposition clarifies how the model can be instantiated in practice while retaining a rigorous strategic interpretation.

The simulation campaign, combining synthetic scenarios and a trace-driven evaluation based on Google Cluster data demonstrates that DSGTA achieves consistent improvements over representative baselines across multiple metrics. In all synthetic scenarios, DSGTA rapidly drives the system towards stable configurations characterized by high tenant utilities, significantly lower resource costs, and controlled utilization levels that avoid chronic under-use and saturation. These trends persist under realistic, bursty workloads derived from Google traces and in large-scale settings with up to 500 tenants, where the controller preserves high utility, near-egalitarian fairness, reduced costs, and better SLA satisfaction rates. The additional statistical tests confirm that the observed gains in utility, cost, and utilization are not artifacts of random fluctuations but are statistically significant when compared to SGTA and DPBA. This directly strengthens the empirical credibility of the model.

From a robustness standpoint, the analysis of the utility parameters shows that DSGTA remains qualitatively stable when the scaling coefficients , , and are varied within reasonable ranges. While these parameters do influence the absolute levels of utility and costs, they do not alter the relative ranking between DSGTA and the baselines nor the overall shape of the learning dynamics. This indicates that the mechanism is not overly tuned to a specific hand-picked configuration and can accommodate different operator preferences regarding performance, pricing, and penalty severity. Similarly, the scalability experiment with increasing numbers of heterogeneous tenants confirms that the controller maintains its desirable properties when the system size grows.

The discussion of computational aspects is also important for practical deployment. A naive computation of Shapley values is exponential in the number of tenants, which would indeed be prohibitive at scale. In the proposed framework, however, the Shapley component is used as an ex-post fairness guideline rather than as a strict real-time decision rule. We rely on Monte Carlo approximations based on a limited number of random permutations, yielding a complexity of order per window with , and focus this computation on the most active tenants. Together with the linear-time best-response updates described in Algorithm 1, this makes the controller compatible with large multi-tenant settings, including cloud, fog, and edge layers, where hundreds of users or services may compete for limited resources.

In hierarchical IoT and fog architectures, DSGTA can naturally be instantiated at different levels (such as gateway, fog node, central cloud) to coordinate local resource allocation games while preserving fairness and efficiency across the whole infrastructure. Beyond pure game theory, the proposed framework also opens the door to tighter integration with machine learning techniques. The current implementation already relies on empirical observations of utilities and SLA outcomes to drive strategy updates, but these feedback loops could be enriched with predictive models. For instance, time-series forecasting or reinforcement learning agents could be used to anticipate future demand states, tune the thresholds and , or adapt the price and penalty factors in a data-driven way. Likewise, clustering or classification methods could automatically infer tenant profiles (aggressive, moderate, conservative, or more refined categories) from historical behavior, providing a more granular and realistic set of strategies. Such hybrid game-theoretic/ML controllers are particularly promising for edge and IoT environments, where workload patterns are highly non-stationary and local context information can be exploited to refine decision-making.

At the same time, several limitations of the present study must be acknowledged. First, although the trace-driven experiments with Google Cluster data significantly improve the realism of the evaluation, the model has not yet been deployed on a real cloud, fog, or edge testbed, and thus does not account for network latencies, failures, or control-plane overheads. Second, the baselines considered (SGTA and DPBA) are representative but not exhaustive, and do not include recent ML-based or Kubernetes-native autoscaling mechanisms; a broader comparison with state-of-the-art controllers is a natural extension. Third, the current metrics focus on tenant utility, resource cost, utilization, fairness, and SLA satisfaction; explicit response time, throughput, and energy consumption are not modelled directly and would require coupling DSGTA with lower-level simulators or measurement frameworks. Finally, the theoretical analysis of convergence is intentionally kept at an intuitive level, and the model assumes rational, non-colluding tenants with access to truthful local feedback. Extending the framework to account for partial observability, strategic misreporting, or coalition formation remains an open research direction.

Overall, the discussion of these results and limitations suggests that DSGTA constitutes a solid and extensible foundation for scalable, fair, and efficient resource allocation in multi-tenant cloud ecosystems. Its combination of repeated and stochastic games, fairness-aware allocation, and trace-validated robustness makes it a promising candidate for integration into future cloud, fog, and edge orchestration systems, while leaving ample room for enhancement through machine learning and more advanced game-theoretic analysis.

8. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we have introduced and extensively evaluated the Dynamic and Stochastic Game-Theoretic Allocation (DSGTA) model for resource management in multi-tenant cloud infrastructures. The proposed framework explicitly models tenants as strategic agents engaged in a repeated, non-cooperative game, while incorporating stochastic variations in workload intensity and heterogeneous SLA requirements. A Nash-like equilibrium is reached through a decentralised best-response update rule, and fairness is enforced by an approximate Shapley-value mechanism that remains computationally tractable even when the number of tenants grows.

The simulation results on synthetic scenarios and Google Cluster traces demonstrate that DSGTA consistently delivers high tenant utility, reduced average cost, improved fairness, and strong SLA satisfaction while maintaining controlled resource utilization. The large-scale experiments with up to tenants, with the explicit reporting of key parameters and statistical tests, substantiate the scalability and robustness of the approach. The comparative study against SGTA and DPBA confirms that the benefits of DSGTA are not artifacts of weak baselines, but stem from its joint modeling of strategic adaptation and stochastic demand.

Several avenues remain open for future research. A first direction is to integrate predictive analytics and machine learning components (such as demand forecasting or reinforcement learning–based policy refinement) to further accelerate convergence and improve performance under highly bursty IoT, fog, and edge workloads. A second direction is to implement a proof-of-concept prototype on real cloud or edge orchestration stacks, detailing the required APIs, monitoring hooks, and computational overheads of the controller. Finally, extending the framework to account explicitly for network latency, energy consumption and communication overhead, as well as studying stronger notions of equilibrium under partial information or collusion, would further enhance the practical applicability of DSGTA in next-generation distributed cloud–edge–IoT ecosystems.

Author Contributions