Ontology-Driven Emotion Multi-Class Classification and Influence Analysis of User Opinions on Online Travel Agency

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Ontology-Based Text Mining

2.2. Social Network Analysis for Influencer Detection

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Selection

3.2. Data Preprocessing

- Financial: A high frequency of keywords such as “refund”, “payment”, and “money” in the word cloud, along with trigram patterns like “uang customer tiketcom” (customer money tiket.com), “tiketcom penuh refund” (tiket.com full refund), and “agoda proses refund” (Agoda refund process), highlighting significant user complaints regarding financial matters. This category encompasses user statements related to service pricing, promotional offers, refund processes, delays in fund disbursement, and other financial issues. The sub-aspects grouped under this category include the following: pricing, payment, discount, and refund.

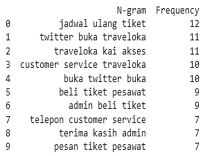

- Booking and support: The presence of keywords such as “customer service”, “booking”, “buy ticket”, and “admin” in the word cloud, as well as trigrams like “customer service Traveloka”, “beli tiket kereta” (buy train ticket), “pesan hotel agoda” (book hotel Agoda), “jadwal ulang tiket” (reschedule ticket), and “telepon customer service” (call customer service), reflects concerns centered around the booking process and interactions with customer support. This category covers discussions related to ticket booking, cancelations or rescheduling, and various forms of user contact with support services. The identified sub-aspects within this group include the following: ticket booking, customer service, and cancelation.

- Platform experience: The emergence of keywords such as “error”, “system”, “application”, and “feature” in the word cloud, as well as trigrams like “kecewa banget agoda” (very disappointed with Agoda) and “twitter buka Traveloka” (Twitter opens Traveloka), indicate user dissatisfaction related to the functionality and usability of the platform. This category includes reviews about system errors, bugs, crashes, or general feedback regarding the ease of use of the application. Accordingly, the sub-aspects defined here are as follows: application errors, usability, and access speed.

- Event: This category specifically captures tweets related to ticket purchases for entertainment events, such as concerts. The reviews range from the ease of buying event tickets and user experiences during the event, to problems encountered in the ticketing process. This aspect was identified due to the prevalence of concert-related reviews, especially on Tiket.com, where keywords like “war” appeared frequently in the word cloud referring to high competition in purchasing concert tickets. Therefore, the event category is treated as a distinct theme, predominantly observed within the context of Tiket.com.

3.3. Ontology Development

- Domain and objective identification. This stage defined the research domain focusing on the user reviews of three OTA platforms—Traveloka, Tiket.com, and Agoda. The primary goal of the ontology is to establish a semantic structure that enables the organization of user opinions according to relevant service aspects.

- Entity and relationship definition. Key concepts and their relationships within the OTA domain were identified. Each entity was connected through object properties that define semantic relationships between aspects.

- Ontology structuring. The ontology was developed using a bottom-up approach, where class hierarchies and relationships were derived directly from data analysis of user-generated content. This approach ensured that the resulting ontology accurately reflected real user opinions and language use patterns. The ontology structure was implemented using the Web Ontology Language (OWL) format in Protégé, with classes, subclasses, and object properties organized progressively from data-level observations to conceptual abstraction.

- Integration with aspect classification. The completed ontology was integrated into the classification pipeline as a semantic structure for aspect mapping. Each tweet was automatically associated with one or more service aspects represented in the ontology, allowing for context-aware and multi-label classification. The resulting aspect mappings were subsequently used as labeled data to train the machine learning models for emotion and sentiment classification.

3.4. Data Tranformation

- Tokenization with WordPiece: Tweets were segmented into WordPiece subwords using the IndoBERT vocabulary (indobenchmark/indobert-base-p2), with [CLS] prepended and [SEP] appended.

- Insertion of Special Tokens: In addition to WordPieces, custom tokens such as [CLS] (Class Token) are added at the beginning of each input sequence and [SEP] (Separator Token) at the end of a sentence. An input sequence refers to the series of tokens (subwords) fed into the model after tokenization, including special tokens such as [CLS] at the beginning and [SEP] at the end. This differs from a natural sentence, which is a raw textual form before preprocessing or token segmentation.

- Conversion to Numeric ID: Each WordPiece and custom token is then converted into a unique numeric ID based on the vocabulary that has been trained. The Embeddings token is further obtained by mapping these numerical IDs into solid vectors stored in a pre-trained embedding table. Each vector represents the initial lexical meaning of the WordPiece or related token. The following is an example of a process:Input Text: Pelayanan hotel sangat ramah dan cepat.WordPiece Tokenization: pelayan, ## an, hotel, sangat, ramah, dan, cepat.Custom Tokens: [CLS], pelayan, ## an, hotel, sangat, ramah, dan, cepat, [SEP].Numeric ID: [CLS] = 101, pelayan = 2345, ## an = 123, hotel = 6789, sangat = 4321, ramah = 987, dan = 54, cepat = 3210, [SEP] = 102. IDs 101 and 102 are the standard IDs for [CLS] and [SEP] in BERT.

- 4.

- Embedding Construction: For each token, three embeddings are retrieved and summed elementwise:where represents the lexical meaning of the token; indicates the sentence origin of the token (segment ID 0 or 1); and encodes the absolute position of the token in the sequence.

- 5.

- Label Encoding: For the emotion classification task, categorical labels were converted into integer indices using the LabelEncoder class from the Scikit-learn library. In contrast, for the multi-label aspect classification task, the MultiLabelBinarizer class was employed to transform each set of aspect labels into a binary vector, where each dimension represents the presence (1) or absence (0) of a particular aspect category.

- 6.

- Attention Mask Creation: Binary masks marked valid tokens (1) and padding tokens (0) to optimize encoder computation.

3.5. Data Modeling

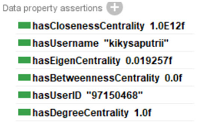

3.6. Social Network Analysis

3.6.1. SNA with Gephi

- Selecting relevant crawled data, extracting source (initiator) and target (recipient) users from the username and in_reply_to_screen_name fields, forming a directed graph (G) (V:E) where nodes V represent users such as individuals, organizations, or other entities and edges (E) indicate reply relationships [42,43].

- The dataset was then imported into Gephi for network statistics computation, including the following: Average Weighted Degree provided insight into the strength of interactions; Network Diameter measured the furthest distance between users in the network; and Modularity revealed the extent to which the network could be divided into distinct communities. A higher modularity score indicated more clearly separated user clusters, often aligning with topic-specific discussions.

- Network Visualization. Node colors were assigned not only according to modularity classes but also to the dominant emotion expressed, green and blue signifying positive tones (joy and positive surprise), while red, orange, and yellow marked negative expressions (anger, sadness, fear, disgust, and negative surprise). This dual color coding allowed for sentiment patterns within communities to be quickly recognized. Node sizes were scaled by weighted degree, making highly connected or influential actors more visually prominent. To optimize layout clarity, the Yifan Hu algorithm was first applied to group related nodes and minimize visual clutter [31], followed by Fruchterman Reingold to further balance spatial distribution and reduce overlaps [44,45].

- Centrality measures. In this study, four basic centrality (degree, betweenness, closeness, and eigenvector) metrics are analyzed [42].

- Degree centrality identifies accounts with the highest interaction activity, calculated as the sum of in-degree and out-degree [46]. It is calculated as [47]:Here, equals 1 if an edge exists from to . The term represents the total incoming edges to (in-degree), and represents the total outgoing edges from (out-degree).

- Betweenness Centrality: Measures how often a node serves as a bridge in the shortest paths among other nodes [3,12,13]. The more often a node is passed in the shortest path between other pairs of nodes, the higher the value of its centrality [48,49]. It is calculated [47], as follows:where is the total number of shortest paths from node i to node j and is the number of those paths that pass through node v.

- Closeness Centrality: Calculates the average of the shortest distance from one node to all other nodes. Nodes with high values have the ability to efficiently spread information throughout the network [5] with the formula used in the equation below [47]:where is the shortest distance from node i to node j and V is the set of all nodes in the network.

- Eigenvector Centrality: Measures a node’s influence based on connections with other nodes that also have an effect. Nodes with high values play a role in strengthening the flow of information [13,14]. The metric is calculated as [47,48,50]:where is the centrality of node which is the centrality value of the nodes connected to which represents the element of the adjacency matrix (1 if a link exists, 0 otherwise), and λ is the largest eigenvalue of the matrix. This ensures that a node’s score is proportional to the sum of its neighbors’ centrality scores, scaled by the principal eigenvalue.

3.6.2. Influence Score

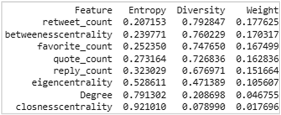

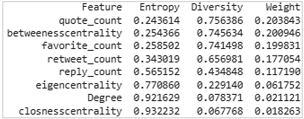

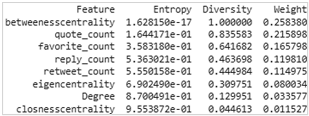

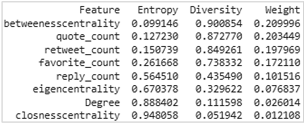

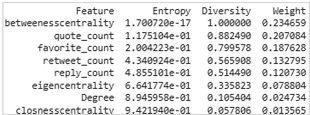

Entropy Weight

- 1.

- Normalization Process: Because these features have different value ranges, normalization was applied to ensure comparability and avoid bias from high-range variables. Using MinMaxScaler, all values were rescaled to the [1] interval before weighting, using the following:where is the value of feature j for user i. This process produced a normalized dataset in which each metric contributed equally prior to the entropy weight calculation.

- 2.

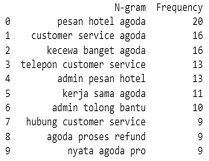

- Entropy Weighting: The entropy weighting method was applied to determine the objective weight of each feature, encompassing both centrality and tweet engagement metrics. This method is preferred as it evaluates the diversity of information in each criterion, ensuring that features with greater variability across users are assigned higher weights. This approach minimizes subjective bias in the evaluation process [51].

- Feature probability (): The first step involves transforming normalized feature values into probabilities, representing the proportion of a user’s contribution to a given feature relative to all users. This is calculated by dividing the normalized value () by the total of that feature across all users, as shown in Equation [5,38,51,52]:where is a small constant to avoid division by zero.

- Entropy per feature (: Entropy, , measures uncertainty in feature j using the following:Higher entropy indicates that feature values are evenly distributed across users (less informative), while a lower entropy suggests concentration on a few users (more informative). Here, is the probability distribution for user I on feature j, n is the number of users, and is a small constant added to avoid undefined logarithmic values [5,38,51,52].

- Information Diversity (: The information diversity score, , is obtained by converting the entropy value of feature j into an information utility measure, using the following:A high entropy value () indicates that data are evenly distributed across users, resulting in low diversity (), whereas low entropy reflects concentrated values and thus higher diversity [38,51,52,53].

- Entropy Weight (: Once the diversity scores are obtained, entropy weighting is applied to determine each feature’s relative contribution to the final influence score, using the following equation [38,51]:Here, m is the total number of features. Each is divided by the sum of all diversity scores to normalize the weights so that Features with higher diversity values indicating greater variability and informativeness are assigned larger weights. This weighting ensures that both network structure metrics and engagement indicators are proportionally represented in the influence score calculation, with features containing more discriminative information receiving greater emphasis.

- Traveloka

- 2.

- Agoda

Influence Score (TOPSIS)

- A-lister Influencers: The highest tier with global influence, typically international celebrities or prominent industry figures with over one million followers, frequently collaborating with major brands, and capable of shaping public opinion and consumer trends.

- Mega Influencers: Generally possessing one million or more followers, but with influence segmented within specific domains. This group often includes business professionals, brokers, or news broadcasters, characterized by high centrality and active information dissemination.

- Macro Influencers: Having between 100,000 and one million followers, they act as a bridge between mass media and niche audiences, often including local celebrities, expert bloggers, or viral content creators, with the potential to transition into mega influencers.

- Micro Influencers: Users with 10,000–100,000 followers, typically exhibiting lower engagement and centrality, with interaction patterns focused on entertainment or educational content.

- Nano Influencer: Users with fewer than 100,000 followers, often consisting of acquaintances or local networks. Despite smaller reach, they possess high accessibility and authenticity, fostering strong personal connections.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Exploratory Data Analysis

4.1.1. Traveloka Exploratory Analysis

4.1.2. Tiket.com Exploratory Analysis

4.1.3. Agoda Exploratory Analysis

4.2. IndoBERT Evaluation

4.3. Ontology for OTAs

4.3.1. Class and Subclass

4.3.2. Object Property

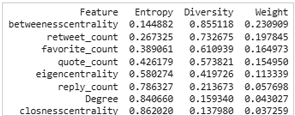

4.3.3. Data Property

4.3.4. Axiom

- Class: ota:AkunUser, SubClassOf: ota:Akun: This axiom states that every entity classified as AkunUser inherently belongs to the Akun class, reflecting the logical hierarchy in which all users are considered account entities.

- DatatypeProperty: ota:hasFullText, Domain: ota:Tweet, Range: xsd:string: This axiom defines the hasFullText property used to store the complete text content of a tweet. It applies only to individuals of the tweet class, with values restricted to the string data type.

- ObjectProperty: ota:membahasAspek, Domain: ota:Tweet, Range: ota:AspekLayanan: This axiom specifies the relationship between a tweet and the AspekLayanan category it addresses, allowing for the representation of tweets that relate to one or more specific service aspects.

4.3.5. Instances by Class

4.3.6. SPARQL

- Retrieving tweets with the fear emotion and highest retweet counts. The query searches for tweets labeled with the fear emotion, orders them by retweet count, and includes related metadata such as platform, category, and username. The SPARQL query used to retrieve these tweets is shown below:SELECT ?tweet ?fullText ?retweetCount ?platformNameWHERE {?tweet rdf:type ota:Tweet .?tweet ota:hasEmosi ota:fear .?tweet ota:hasRetweetCount ?retweetCount .?tweet ota:belongsToPlatform ?platformUri .}ORDER BY DESC(?retweetCount)LIMIT 10Most tweets related to fear involved scam alerts and fraudulent refund requests, particularly targeting Traveloka and Agoda users.

- 2.

- Retrieving anger tweets on Traveloka with >100 retweets. Filters tweets expressing anger from Traveloka’s dataset, focusing on those exceeding 100 retweets. The SPARQL query used to retrieve these tweets is shown below:SELECT ?fullText ?retweetCountWHERE {?tweet rdf:type ota:Tweet .?tweet ota:hasEmosi ?emotionInstance .?emotionInstance rdf:type ota:Anger .?tweet ota:belongsToPlatform ota:TravelokaPlatform .FILTER (?retweetCount > 100) .}ORDER BY DESC(?retweetCount)High-retweet anger tweets were often about delayed refunds, accidental purchases, and scams under “Travel Expert” branding.

4.3.7. Consistency Evaluation

4.4. SNA

4.4.1. Traveloka Social Network Analysis

4.4.2. Tiket.com Social Network Analysis

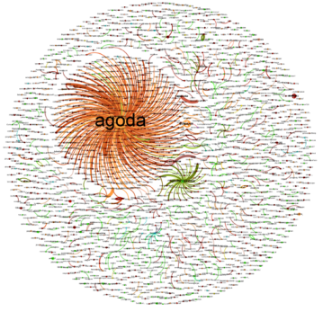

4.4.3. Agoda Social Network Analysis

4.4.4. Spearman

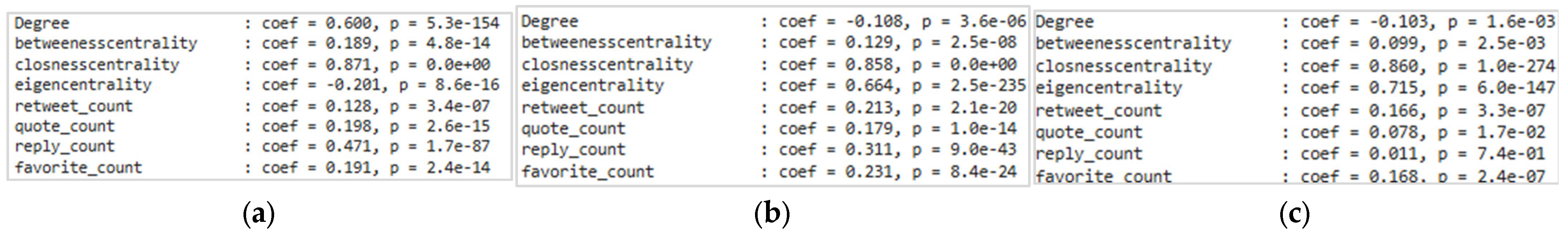

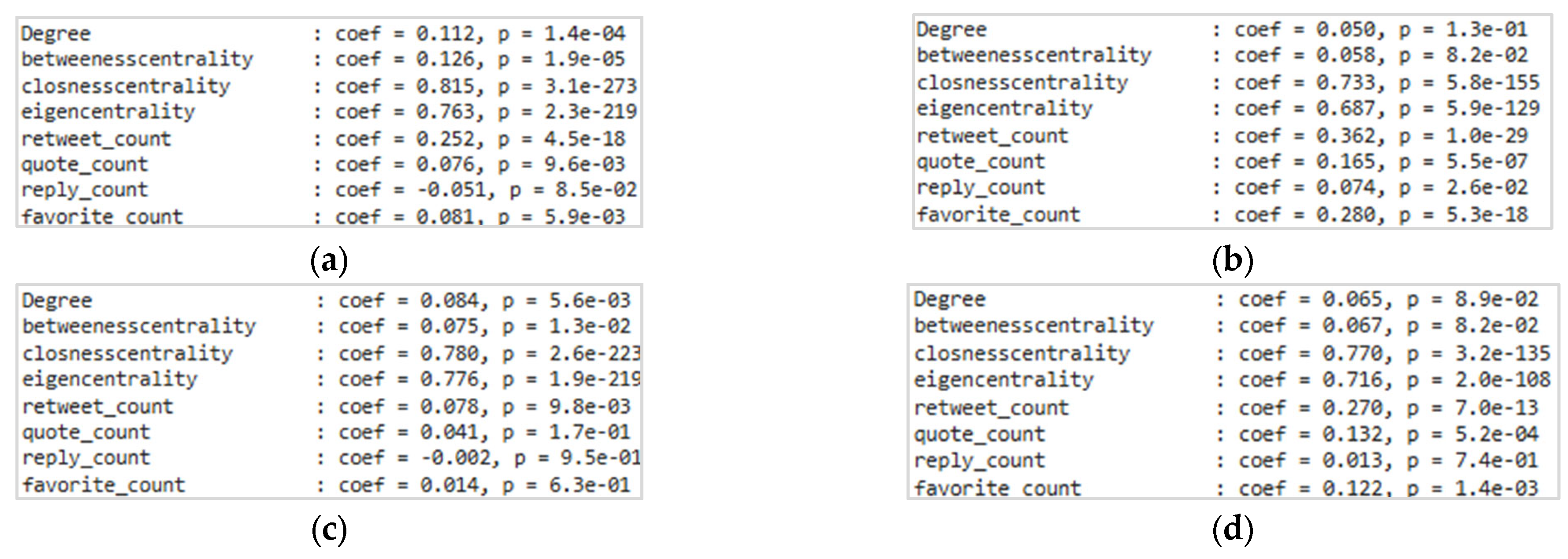

Spearman Correlation for Traveloka

Spearman Correlation for Tiket.com

Spearman Correlation for Agoda

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarmast Hasan Kiadeh, Z.; Shokouhyar, S.; Omarzadeh, A.; Shokoohyar, S. Warranty Operation Enhancement through Social Media Knowledge: A Deep-Learning Methods. INFOR 2024, 62, 273–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresa Borges-Tiago, M.; Arruda, C.; Tiago, F.; Rita, P. Differences between TripAdvisor and Booking.Com in Branding. Co-Creation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, A.R.; Fachrizal, F.; Lubis, M. The Effect of Social Media to Cultural Homecoming Tradition of Computer Students in Medan. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 124, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhayati, H. Most Popular Online Travel Agencies Among Consumers in Indonesia as of June 2023; Statista: Hamburg, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Butar, J.B.; Lusa, S.; Handayani, S.; Yusuf, A.A. Analyzing Abstention Discourse in Presidential Elections: Knowledge Discovery in X Using ML, LDA and SNA. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2024, 14, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahra, M.; Fennan, A. Smart City: An Advanced Framework for Analyzing Public Sentiment Orientation toward Recycled Water. Int. J. Electr. Comput. Eng. 2024, 14, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratiwi, H.; Benkő, R.; Kusuma, I.Y. Navigating the Asthma Network on Twitter: Insights from Social Network and Sentiment Analysis. Digit. Health 2024, 10, 20552076231224075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueger, J.; Dolfsma, W.; Aalbers, R. Mining and Analysing Online Social Networks: Studying the Dynamics of Digital Peer Support. MethodsX 2023, 10, 102005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. An Argument for Basic Emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P.; Sorenson, E.R.; Friesen, W.V. Pan-Cultural Elements in Facial Displays of Emotion. Science 1969, 164, 86–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sam, K.M.; Chatwin, C.R. Ontology-Based Sentiment Analysis Model of Customer Reviews for Electronic Products. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation & Technology (ICMIT), Bali, Indonesia, 11–13 June 2012; pp. 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentaruk, I.; Herdiani, A.; Puspandari, D. Analisis Sentimen Twitter Transportasi Online Berbasis Ontologi (Studi Kasus: Go-Jek). e-Proceeding Eng. 2019, 6, 2029–2047. [Google Scholar]

- Koto, F.; Rahimi, A.; Lau, J.H.; Baldwin, T. IndoLEM and IndoBERT: A Benchmark Dataset and Pre-Trained Language Model for Indonesian NLP. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2020), Online, 8–11 December 2020; pp. 757–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, T.; Bhatt, A. HWSMCB: A Community-Based Hybrid Approach for Identifying Influential Nodes in the Social Network. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2020, 545, 123590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ait Rai, K.; Agouti, T.; Machkour, M.; Antari, J. Identification of Complex Network Influencer Using the Technology for Order Preference by Similarity to an Ideal Solution. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1743, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Pan, L. Data-Driven Influential Nodes Identification in Dynamic Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 17th EAI International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing, Suzhou, China, 16–17 October 2021; ISBN 9783030926373. [Google Scholar]

- Al Zaabi, H.; Bashir, H. Modeling and Analyzing Project Interdependencies in Project Portfolios Using an Integrated Social Network Analysis-Fuzzy TOPSIS MICMAC Approach. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2020, 11, 1083–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, H. A Social Network Analysis in Dynamic Evaluate Critical Industries Based on Input-Output Data of China. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, D.K.; Qamar, S.; Sangwan, S.R.; Ding, W.; Kulkarni, A.J. Ontology-Based Natural Language Processing for Sentimental Knowledge Analysis Using Deep Learning Architectures. ACM Trans. Asian Low-Resour. Lang. Inf. Process. 2024, 23, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradeh, A.; Kurdy, M.B. ArEmotive Bridging the Gap: Automatic Ontology Augmentation Using Zero-Shot Classification for Fine-Grained Sentiment Analysis of Arabic Text. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81318–81330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma’aly, A.N.; Pramesti, D.; Fathurahman, A.D.; Fakhrurroja, H. Exploring Sentiment Analysis for the Indonesian Presidential Election Through Online Reviews Using Multi-Label Classification with a Deep Learning Algorithm. Information 2024, 15, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, Y.; Kim, M.; Hong, S.H. Identification of Emotional Spectrums of Patients Taking an Erectile Dysfunction Medication: Ontology-Based Emotion Analysis of Patient Medication Reviews on Social Media. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e50152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahri, M.T. Evidence of the Digital Nomad Phenomenon: From “Reinventing” Migration Theory to Destination Countries Readiness. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.; Ye, J.H. A Social Network Analysis of College Students’ Online Learning during the Epidemic Era: A Triadic Reciprocal Determinism Perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essameldin, R.; Ismail, A.A.; Darwish, S.M. Quantifying Opinion Strength: A Neutrosophic Inference System for Smart Sentiment Analysis of Social Media Network. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essameldin, R.; Ismail, A.A.; Darwish, S.M. An Opinion Mining Approach to Handle Perspectivism and Ambiguity: Moving Toward Neutrosophic Logic. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 63314–63328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusuma, I.Y.; Suherman, S. The Pulse of Long COVID on Twitter: A Social Network Analysis. Arch. Iran. Med. 2024, 27, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, B. The Furniture of the World: Essays in Ontology and Metaphysics, 9th ed.; Hurtado, G., Nudler, O., Eds.; Brill: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 9789401207799. [Google Scholar]

- Antoniou, G.; Harmelen, F.V. A Semantic Web Primer, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; Volume 24, ISBN 9780262012423. [Google Scholar]

- Slimani, T. A Study Investigating Typical Concepts and Guidelines for Ontology Building. J. Emerg. Trends Comput. Inf. Sci. 2014, 5, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Jin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, J. Ontological Method for the Modeling and Management of Building Component Construction Process Information. Buildings 2023, 13, 2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubis, A.R.; Prayudani, S.; Lubis, M.; Nugroho, O. Sentiment Analysis on Online Learning During the Covid-19 Pandemic Based on Opinions on Twitter Using KNN Method. In Proceedings of the 2022 1st International Conference on Information System & Information Technology (ICISIT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 27–28 July 2022; pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lubis, F.S.; Lubis, M.; Hakim, L.; Fakhrurroja, H. The Text Mining Analysis Approach for Electronic Information and Transaction (ITE) Implementation Based on Sentiment in the Social Media; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Cotfas, L.-A.; Delcea, C.; Roxin, I.; Paun, R. Twitter Ontology-Driven Sentiment Analysis. In New Trends in Intelligent Information and Database Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 598, pp. 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Saraswat, M. A Robust Approach for Aspect-Based Sentiment Analysis Using Deep Learning and Domain Ontologies. Electron. Libr. 2024, 42, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, A.R.; Thomas, A.; Mishra, L.; Murthy, R.N.; Straub, T. An Ontology-Based Text Mining Dataset for Extraction of Process-Structure-Property Entities. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, F.; El-Sappagh, S.; Kwak, D. Fuzzy Ontology and LSTM-Based Text Mining: A Transportation Network Monitoring System for Assisting Travel. Sensors 2019, 19, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.F.; Jiang, Q. Evaluation of Regional Innovation Capacity Based on Social Network Analysis and Entropy-Based GC-TOPSIS. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2024, 2024, 3149746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamba, M.; Madhusudhan, M. Text Mining for Information Professionals; Springer Nature: Delhi, India, 2022; ISBN 9783030850845. [Google Scholar]

- Leppink, J.; Pérez-Fuster, P. Social Networks as an Approach to Systematic Review. Health Prof. Educ. 2019, 5, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharuddin, F.; Naufal, M.F. Fine-Tuning IndoBERT for Indonesian Exam Question Classification Based on Bloom’s Taxonomy. J. Inf. Syst. Eng. Bus. Intell. 2023, 9, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, M.; Muruganantham, A. Potential Influencers Identification Using Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2015, 57, 1179–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zhou, Y. Social Network Analysis: Studying Social Interactions and Relations in the Workplace. In Methodological Approaches for Workplace Research and Management; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 144–157. ISBN 9781000892628. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Fruchterman, T.M.J.; Reingold, E.M. Graph Drawing by Force-Directed Placement. Softw. Pract. Exp. 1991, 21, 1129–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacomy, M.; Venturini, T.; Heymann, S.; Bastian, M. ForceAtlas2, a Continuous Graph Layout Algorithm for Handy Network Visualization Designed for the Gephi Software. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e98679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Koufi, N.; Belangour, A. Toward a Recommender System for Assisting Customers at Risk of Churning in E-Commerce Platforms Based on a Combination of Social Network Analysis (SNA) and Deep Learning. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2024, 10, 100425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, Y.M.; Plapper, P. A Survey of Information Entropy Metrics for Complex Networks. Entropy 2020, 22, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litterio, A.M.; Nantes, E.A.; Larrosa, J.M.; Gómez, L.J. Marketing and Social Networks: A Criterion for Detecting Opinion Leaders. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 26, 347–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Z.; Sun, H.; Cheng, J.; Wang, H.; Yao, Z. China’s Rare Earth Industry Technological Innovation Structure and Driving Factors: A Social Network Analysis Based on Patents. Resour. Policy 2021, 73, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhrurroja, H.; Atmaja, M.N.; Panjaitan, J.N.C.G.; Alamsyah, A.; Munandar, A. Crisis Communication on Twitter: A Social Network Analysis of Christchurch Terrorist Attack in 2019. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society(ICISS), Bandung, Indonesia, 19–20 November 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J. Combining Entropy Weight and TOPSIS Method for Information System Selection. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems, Chengdu, China, 21–24 September 2008; pp. 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahan, A.; Edwards, K.L.; Bahraminasab, M. Multiattribute Decision-Making for Ranking of Candidate Materials. In Multi-criteria Decision Analysis for Supporting the Selection of Engineering Materials in Product Design; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 43–82. ISBN 978-0-08-100536-1. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, J.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Yuan, L. Research on Entropy-Weighting TOPSIS Method Basedon Shanghai Digital Economy Index System. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computer Science, Information Engineering and Digital Economy (CSIEDE 2022), Guangzhou, China, 28–30 October 2022; Volume 103, pp. 656–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.N.; Kim, H. Analyzing the International Connectivity of the Major Container Ports in Northeast Asia. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2022, 7, 332–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.M.; Imran, M.; Sajjad, H. Understanding Types of Users on Twitter. arXiv 2024, arXiv:1406.1335. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.; Farrell, J.R. More than Meets the Eye: The Functional Components Underlying Influencer Marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cohen’s Kappa | Results |

|---|---|

| Sentiment Label | 0.73 |

| Emotion Label | 0.58 |

| Average Cohen’s Kappa | 0.65 |

| Percentage Cohen’s Kappa | 65% |

| Detail Preprocessing Stage | Traveloka | Tiket.com | Agoda |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Tweets | 19,037 | 17,220 | 6899 |

| Tweet After Data Cleaning | 4025 | 2605 | 2479 |

| Tweets Processed (Case Folding Stage) | 3383 | 1948 | 1595 |

| Total Token Count | 76,380 | 50,559 | 46,376 |

| Average Tokens per Tweet | 18.9 | 19.4 | 18.7 |

| Tweets Processed (Spell Correction Stage) | 3467 | 2138 | 2026 |

| Unique Tokens (Pre-Stemming) | 7471 | 6231 | 5662 |

| Unique Tokens (Post-Stemming) | 6071 | 5165 | 4700 |

| OTA | Trigram | Word Cloud |

|---|---|---|

| Traveloka |  |  |

| Tiket.com |  |  |

| Agoda |  |  |

| Data | Entropy Weight Result |

|---|---|

| Booking and Support |  |

| Financial |  |

| Platform Experience |  |

| Data | Entropy Weight Result |

|---|---|

| Booking and Support |  |

| Financial |  |

| Platform Experience |  |

| Event |  |

| Data | Entropy Weight Result |

|---|---|

| Booking and Support |  |

| Financial |  |

| Platform Experience |  |

| Aspect | Joy | Sadness | Anger | Fear | Positive Surprise | Negative Surprise | Disgust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booking and Support | Customer Service | 514 | 294 | 212 | 167 | 18 | 13 | 13 |

| cancelations | 163 | 70 | 58 | 22 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Ticket Orders | 1899 | 400 | 213 | 100 | 47 | 26 | 18 | |

| Financial | Discounts | 1371 | 57 | 30 | 15 | 19 | 5 | 1 |

| Prices | 320 | 99 | 65 | 14 | 25 | 12 | 5 | |

| Payments | 231 | 161 | 108 | 89 | 8 | 6 | 6 | |

| Refunds | 187 | 100 | 96 | 35 | 6 | 5 | 5 | |

| Platform Experience | Application Errors | 10 | 64 | 32 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 0 |

| Access Speed | 67 | 60 | 58 | 14 | 4 | 1 | 6 | |

| Usability | 559 | 130 | 97 | 27 | 9 | 14 | 23 | |

| Aspect | Joy | Sadness | Anger | Fear | Positive Surprise | Negative Surprise | Disgust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booking and Support | Customer Service | 206 | 175 | 232 | 40 | 22 | 8 | 12 |

| Cancelations | 15 | 33 | 53 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 4 | |

| Ticket Orders | 700 | 429 | 583 | 116 | 81 | 36 | 37 | |

| Event | Concert | 146 | 125 | 254 | 51 | 35 | 9 | 13 |

| Financial | Discounts | 217 | 39 | 34 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| Prices | 299 | 42 | 76 | 7 | 18 | 5 | 4 | |

| Payments | 79 | 64 | 198 | 25 | 13 | 4 | 3 | |

| Refunds | 70 | 56 | 150 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 3 | |

| Platform Experience | Application Errors | 34 | 55 | 97 | 15 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Access Speed | 63 | 58 | 121 | 13 | 8 | 0 | 2 | |

| Usability | 184 | 98 | 208 | 37 | 19 | 8 | 21 | |

| Aspect | Joy | Sadness | Anger | Fear | Positive Surprise | Negative Surprise | Disgust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booking and Support | Customer Service | 91 | 222 | 463 | 73 | 6 | 13 | 91 |

| Cancelations | 11 | 98 | 193 | 35 | 3 | 8 | 11 | |

| Ticket Orders | 283 | 200 | 334 | 107 | 18 | 36 | 283 | |

| Financial | Discounts | 149 | 35 | 64 | 13 | 9 | 8 | 149 |

| Prices | 182 | 31 | 53 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 182 | |

| Payments | 69 | 153 | 296 | 103 | 1 | 8 | 69 | |

| Refunds | 58 | 257 | 417 | 51 | 4 | 7 | 58 | |

| Platform Experience | Application Errors | 1 | 14 | 52 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Access Speed | 21 | 42 | 62 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 21 | |

| Usability | 76 | 106 | 119 | 34 | 3 | 48 | 76 | |

| Class | Subclass Of |

|---|---|

| Class: ota:Akun | SubClassOf: owl:Thing |

| Class: ota:AkunUser | SubClassOf: ota:Akun |

| Class: ota:PlatformOTA | SubClassOf: owl:Thing |

| Class: ota:Tweet | SubClassOf: owl:Thing |

| Class: ota: AspekLayanan | SubClassOf: owl:Thing |

| Class: ota:AspekFinancial | SubClassOf: ota:AspekLayanan |

| Class: ota:AspekBookingSupport | SubClassOf: ota:AspekLayanan |

| Class: ota:AspekPlatformExperience | SubClassOf: ota:AspekLayanan |

| Class: ota:AspekEvent | SubClassOf: ota:AspekLayanan |

| Class: ota:Diskon | SubClassOf: ota:AspekFinancial |

| Class: ota:Refund | SubClassOf: ota:AspekFinancial |

| Class: ota:Pembayaran | SubClassOf: ota:AspekFinancial |

| Class: ota:Harga | SubClassOf: ota:AspekFinancial |

| Class: ota:CustomerService | SubClassOf: ota:AspekBookingSupport |

| Class: ota:Pembatalan | SubClassOf: ota:AspekBookingSupport |

| Class: ota:PemesananTiket | SubClassOf: ota:AspekBookingSupport |

| Class: ota:KecepatanAkses | SubClassOf: ota:AspekPlatformExperience |

| Class: ota:Usability | SubClassOf: ota:AspekPlatformExperience |

| Class: ota:ErrorAplikasi | SubClassOf: ota:AspekPlatformExperience |

| Class: ota:Konser | SubClassOf: ota:AspekEvent |

| Class: ota:Opini | SubClassOf: owl:Thing |

| Class: ota:Sentimen | SubClassOf: ota:Opini |

| Class: ota:Emosi | SubClassOf: ota:Opini |

| Class: ota:Positif | SubClassOf: ota:Sentimen |

| Class: ota:Negatif | SubClassOf: ota:Sentimen |

| Class: ota:PositifEmosi | SubClassOf: ota:Emosi |

| Class: ota:Joy | SubClassOf: ota:PositifEmosi |

| Class: ota:SurprisePositif | SubClassOf: ota:PositifEmosi |

| Class: ota:NegatifEmosi | SubClassOf: ota:Emosi |

| Class: ota:Anger | SubClassOf: ota: NegatifEmosi |

| Class: ota:Sadness | SubClassOf: ota: NegatifEmosi |

| Class: ota:Fear | SubClassOf: ota: NegatifEmosi |

| Class: ota:Disgust | SubClassOf: ota: NegatifEmosi |

| Class: ota:SurpriseNegatif | SubClassOf: ota: NegatifEmosi |

| Object Property | Description |

|---|---|

| ObjectProperty: ota:belongsToPlatform Domain: ota:Tweet Range: ota:PlatformOTA | Connecting a tweet to the OTA platform mentioned or associated with the tweet. |

| ObjectProperty: ota:hasEmosi Domain: ota:Tweet Range: ota: Emosi | Connecting a tweet to the emotions expressed in an opinion. |

| ObjectProperty: ota:hasSentimen Domain: ota:Tweet Range: ota:Sentimen | Connecting a tweet to the overall sentiment (positive/negative) expressed. |

| ObjectProperty: ota:postedBy Domain: ota:Tweet Range: ota:AkunUser | Connect a tweet to the account of the user who posted it. |

| ObjectProperty: ota:membahasAspek Domain: ota:Tweet Range: ota:AspekLayanan | Linking a tweet to the topic category contained in the tweet related to the specific service aspect being discussed (e.g., Refunds, Pricing, and CS, etc.) |

| ObjectProperty: ota:hasMainAspectCategory Domain: ota:Tweet Range: ota:AspekLayanan | To show the categories of key service aspects that are discussed or relevant to the tweet. |

| Data Property | Description |

|---|---|

| DatatypeProperty: ota:hasUserID Domain: ota:AkunUser Range: xsd:string | Storing a unique ID from a user account. |

| DatatypeProperty: ota:hasUsername Domain: ota:AkunUser Range: xsd:string | Save your username from your account. |

| DatatypeProperty: ota: hasFullText Domain: ota:Tweet Range: xsd:string | Save the full text of a tweet. |

| DatatypeProperty: ota:hasLabelManual Domain: ota:Tweet Range: xsd:string | Keeping sentiment labels on tweets. |

| DatatypeProperty: ota:hasReplyCount Domain: ota:Tweet Range: xsd:integer | Save the number of replies for tweets. |

| DatatypeProperty: ota:hasRetweetCount Domain: ota:Tweet Range: xsd:integer | Save the number of retweets for a tweet. |

| DatatypeProperty: ota: hasQuoteCount Domain: ota:Tweet Range: xsd:integer | Save the number of quotes for tweets. |

| DatatypeProperty: ota:hasFavoriteCount Domain: ota:Tweet Range: xsd:integer | Save the number of likes or favorites for a tweet. |

| Class or Subclass | Instances | Description |

|---|---|---|

| PlatformOTA | Agoda Platform Tiket Platform Traveloka Platform | Individuals representing each OTA. |

| AspekBookingSupport | Booking | Instances that represent the Booking topic in the ontology. |

| AspekFinancial | Financial | Instances that represent the Financial topic. |

| AspekPlatformExperience | Platform Experience | This instance represents the Platform experience topic. |

| AspekEvent | Event | This instance represents the Event topic. |

| AspekLayanan | {AspekName}Aspect Instance | Individuals created for each specific service aspect. |

| NegatifEmosi | anger, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise_negatif | Emotion instances classified as negative emotions. |

| PositifEmosi | joy, surprise_positif | Emotion instances classified as positive emotions. |

| AkunUser | User_{id} , e.g., User_1f10ab2de3857c4d23dca2892112a80d |  |

| Tweet | Tweet_{OTA}_{AspekLayanan}_{id} , e.g., Tweet_Tiket_PlatformExperience_511 |  |

| Category | Network | Results | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

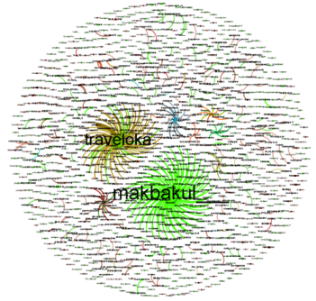

| Booking and Support | Graph |  | The discussion about booking and support at Traveloka involved several different communities with a high weighted degree of interaction in it. Information can spread relatively quickly (low network diameter). The existence of the “traveloka” and “makbakul” accounts as prominent nodes indicates their important role in this discussion network either as information centers or frequently interacting parties. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.895 | ||

| Network Diameter | 3 | ||

| Modularity | 0.823 | ||

| Communities | 320 | ||

| Financial | Graph |  | Discussions about the financial category on Traveloka has the highest weighted degree value among all categories, characterized by a very strong and intensive interaction between users. Although the dissemination of information may be a little slower, it is characterized by higher network diameter values than others. Although high in communities, the boundaries between communities are not very strict, allowing for more interaction between groups in discussing financial issues. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.953 | ||

| Network Diameter | 4 | ||

| Modularity | 0.716 | ||

| Communities | 401 | ||

| Platform Experience | Graph |  | Discussions about the platform experience on Traveloka show the rapid dissemination of information, but with a very separate community and interactions that tend to occur within groups. The prominent account “makbakul” shows its significant role in this discussion, perhaps as the main source of feedback or opinions regarding the platform. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.768 | ||

| Network Diameter | 2 | ||

| Modularity | 0.888 | ||

| Communities | 214 |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| Frimawan | 0 | 0.00000 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 1370 | 300 | 940 | 12,190 | 0.5016 | 2010 | 212.3K | 911 | Personal | Macro Influencer |

| makbakul___ | 216 | 0.00000 | 0.00 | 0.6384 | 2580 | 40 | 7140 | 2020 | 0.4773 | 2018 | 126.1K | 3641 | Personal (v) | Macro Influencer |

| Widino | 36 | 0.00005 | 0.75 | 0.1313 | 120 | 10 | 42 | 670 | 0.3522 | 2010 | 193.4K | 1140 | Personal (v) | Micro Influencer |

| chillinfangurl | 2 | 0.00002 | 0.00 | 0.0368 | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1406 | 2019 | 291 | 452 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| claudiasilvinia | 3 | 0.00000 | 0.00 | 0.0080 | 66 | 0 | 2 | 29,996 | 0.1021 | 2010 | 56.9K | 554 | Personal | Micro Influencer |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| aldapstsr | 30 | 0.00001 | 1.0000 | 0.0641 | 16,490 | 380 | 850 | 117,650 | 0.6318 | 2017 | 198.6K | 1870 | Personal (v) | Micro Influencer |

| Widino | 11 | 0.00000 | 0.0000 | 0.0212 | 17,680 | 1560 | 3640 | 31,270 | 0.5510 | 2010 | 193.4K | 1140 | Personal (v) | Micro Influencer |

| hhaijuli | 7 | 0.00001 | 0.5652 | 0.0046 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0.3123 | 2014 | 9566 | 2978 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| waudira | 9 | 0.000004 | 1.0000 | 0.0151 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0.2031 | 2013 | 40.2K | 2359 | Personal (v) | Micro Influencer |

| zakahats | 4 | 0.000004 | 0.4815 | 0.0027 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0.2031 | 2011 | 1057 | 778 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| Frimawan | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.0081 | 1370 | 300 | 940 | 12,190 | 0.4943 | 2010 | 212.3K | 911 | Personal | Macro Influencer |

| makbakul___ | 123 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 1.0000 | 2580 | 40 | 7140 | 2020 | 0.4943 | 2018 | 126.1K | 3641 | Personal (v) | Macro Influencer |

| Vita_ANJell | 5 | 0.00001 | 1.0 | 0.0325 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3597 | 2009 | 105 | 208 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| caramlecchiato | 2 | 0.000002 | 1.0 | 0.0081 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.1146 | 2012 | 1497 | 2113 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| rzkynduls | 2 | 0.000002 | 1.0 | 0.0081 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.1145 | 2010 | 1521 | 833 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| Category | Network | Results | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

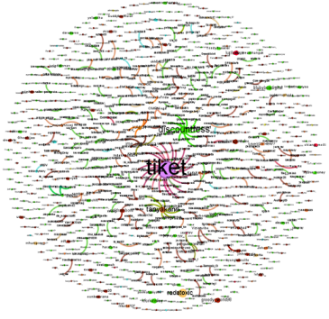

| Booking and Support | Graph |  | In the Booking and Support network, the interaction between users in this network is on average not very intense (low weighted degree). Information can spread quickly (low diameter), booking and support discussions in Tiket.com tend to be fragmented in many small communities that are less connected to each other (high modularity) which suggests that interactions tend to occur within individual groups, with little interaction between groups. This is also shown by the large value of communities. Prominent “ticket” accounts and official accounts serve as a central repository for questions or complaints from these various separate communities. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.663 | ||

| Network Diameter | 2 | ||

| Modularity | 0.982 | ||

| Communities | 0.663 | ||

| Financial | Graph |  | Discussions on the topic of Finance in Tiket.com are also characterized by strong community fragmentation (high modularity) and low intensity of interaction (low weighted degree). Communities are less evident than Booking and Support, but still show significant fragmentation. Although information can spread quickly, conversations tend to take place in relatively isolated groups. Similarly to the previous category, several different color groups are visible, with the “tickets” and “discountfess” nodes prominent. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.665 | ||

| Network Diameter | 2 | ||

| Modularity | 0.972 | ||

| Communities | 225 | ||

| Platform Experience | Graph |  | Discussions about the platform experience in Tiket.com are also highly fragmented in many small communities that are less connected and have relatively low interaction (high modularity and low weighted degree). The emergence of the “officialJKT48” and “KAI21” accounts as important actors shows that there is a discussion on the experience platform related to the JKT 48 group event and a discussion of services or products in collaboration with KAI. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.667 | ||

| Network Diameter | 2 | ||

| Modularity | 0.982 | ||

| Communities | 280 | ||

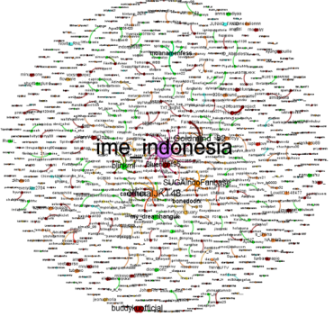

| Graph |  | Discussions about events in Tiket.com show high community fragmentation with the lowest average interaction intensity. The emergence of the promoter of the event “ime_indonesia” and the related parties of the event “officialJKT48” as important actors shows the focus of the discussion on the promotion and information related to the event. | |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.653 | ||

| Event | Network Diameter | 2 | |

| Modularity | 0.981 | ||

| Communities | 192 |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| officialJKT48 | 3 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.0578 | 219 | 140 | 303 | 3538 | 0.5745 | 2011 | 4.9M | 260 | Fanbase | A-Listers Influencer |

| kikysaputrii | 1 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.0193 | 144 | 243 | 299 | 1389 | 0.5169 | 2009 | 290.7K | 462 | Personal (v) | Macro Influencer |

| indiiikk | 4 | 0.000001 | 1.0 | 0.3054 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.3694 | 2010 | 590 | 185 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| AkhidIhsanudin | 2 | 0.000001 | 1.0 | 0.0193 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 0.3694 | 2019 | 12 | 593 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| aesple | 2 | 0.000001 | 1.0 | 0.0193 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0.3686 | 2021 | 93 | 1442 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| discountfess | 13 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.3714 | 128 | 273 | 363 | 1831 | 0.5033 | 2020 | 702.3K | 14.8K | Business (v) | Macro Influencer |

| rararsmn | 0 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.0000 | 43 | 4 | 246 | 29 | 0.1464 | 2010 | 3482 | 1309 | Personal (v) | Nano Influencer |

| kyomiethurr | 0 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.0000 | 63 | 19 | 7 | 44 | 0.1017 | 2012 | 729 | 855 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| twelvefordks | 0 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.0000 | 54 | 1 | 2 | 37 | 0.0820 | 2022 | 401 | 572 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| TrinityTravele | 2 | 0.00000 | 0.0 | 0.4647 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 86 | 0.0606 | 2009 | 272.9K | 1052 | Personal | Macro Influencer |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| kikysaputrii | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.0000 | 126 | 470 | 297 | 863 | 0.4594 | 2009 | 290.7K | 462 | Personal (v) | Macro Influencer |

| dlayyyyyyyy | 2 | 0.000003 | 1.0 | 0.0179 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 0.3902 | 2022 | 11.1K | 849 | Personal | Micro Influencer |

| crescentbin | 2 | 0.000003 | 1.0 | 0.0179 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0.3894 | 2017 | 868 | 875 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| afnanboma10 | 4 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 1.0000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1072 | 2019 | 2027 | 1710 | Personal (v) | Nano Influencer |

| naim_pasha | 2 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.5000 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 109 | 0.0621 | 2012 | 2324 | 5333 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| officialJKT48 | 8 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.1586 | 219 | 140 | 303 | 3538 | 0.5486 | 2011 | 4.9M | 260 | Fanbase (v) | A-Listers Influencer |

| miunggii | 2 | 0.000006 | 1.0 | 0.0198 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4452 | 2020 | 14.1K | 4304 | Personal (v) | Micro Influencer |

| ime_indonesia | 21 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 1.0000 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1110 | 2017 | 77.2K | 58 | Business | Micro Influencer |

| naim_pasha | 2 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.6034 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 110 | 0.0718 | 2012 | 2324 | 5333 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| rnrubyjane | 2 | 0.000000 | 0.0 | 0.6034 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.0694 | 2016 | 436 | 444 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

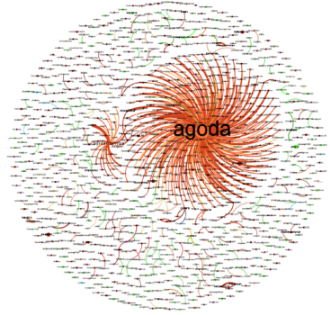

| Category | Network | Results | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Booking and Support | Graph |  | In the booking and support network, Agoda has an average value. The weighted degree is high; the intensity of conversations between users in the discussion network is very strong. The network is relatively small in diameter, indicating that the longest path between two users in this network is only four steps. This implies a fairly rapid dissemination of information. Low modularity values indicate unclear boundaries between communities and high potential for interaction. Agoda’s official account “agoda” plays a central role in this network. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.995 | ||

| Network Diameter | 4 | ||

| Modularity | 0.576 | ||

| Communities | 230 | ||

| Financial | Graph |  | In the Agoda financial network, a high weighted degree value indicates a strong and intensive interaction between users. A larger diameter than Booking and Support indicates a slightly slower dissemination of information or more intermediaries. In addition, the modularity value is moderate, showing a clearer boundary between communities than Booking and Support, but not a very firm one. There is a tendency to form more specific groups but there is still interaction between groups. The “agoda” node is still seen as the main actor with many connections. The number of communities is the largest, showing a variety of discussion groups related to financial issues. |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.934 | ||

| Network Diameter | 6 | ||

| Modularity | 0.744 | ||

| Communities | 392 | ||

| Platform Experience | Graph |  | The weighted degree value is high, indicating a fairly strong interaction between users in the discussion of the platform’s experience. The relatively small diameter, shows a fairly fast dissemination of information related to the platform’s experience. The value of modularity is quite high, indicating that the boundaries between communities that are quite clear and that interactions are more likely to occur within each group. In addition, the number of communities is the least, indicating fewer discussion groups |

| Average Weighted Degree | 0.877 | ||

| Network Diameter | 3 | ||

| Modularity | 0.834 | ||

| Communities | 125 |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| DeanOrDeen | 4 | 0.000002 | 1.0 | 0.0088 | 94,040 | 2230 | 690 | 178,720 | 0.7342 | 2020 | 17.5K | 820 | Personal | Micro Influencer |

| txtdrdigital | 6 | 0.000007 | 1.0 | 0.0132 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 10 | 0.2755 | 2022 | 47.8K | 429 | Media | Micro Influencer |

| sidhanty | 4 | 0.000007 | 0.8 | 1.0000 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 0.2754 | 2009 | 1269 | 387 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| wdrtdewi | 3 | 0.000004 | 1.0 | 0.0088 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0.1765 | 2009 | 530 | 304 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| HayatiJunia | 4 | 0.000002 | 1.0 | 0.0088 | 0 | 10 | 110 | 0 | 0.0951 | 2020 | 0 | 65 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| eddthinksdesign | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 53,340 | 3910 | 910 | 86,250 | 0.7253 | 2014 | 21.7K | 741 | Professional | Micro Influencers |

| novirahayuni__ | 3 | 0.000004 | 0.75 | 0.0039 | 0 | 10 | 80 | 0 | 0.2334 | 2019 | 4650 | 28 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| DeanOrDeen | 7 | 0.000003 | 1.00 | 0.0156 | 260 | 0 | 30 | 1360 | 0.1866 | 2020 | 17.5K | 820 | Personal | Micro Influencer |

| novafah_ | 6 | 0.000003 | 0.60 | 0.0071 | 0 | 10 | 120 | 0 | 0.1855 | 2022 | 2 | 4 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| tamabicara | 6 | 0.000003 | 0.78 | 0.0031 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0.1854 | 2020 | 5 | 32 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| Account | Centrality Metrics | Counts of Tweet Engagement | Influence Score | Account Year | Followers | Following | Account Types | Influencer Types | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | BC | CC | EC | RT | QT | RP | FV | |||||||

| cheesenuttie | 14 | 0.000045 | 1.00 | 0.1116 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4570 | 2023 | 162 | 182 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| twt_lutfi | 1 | 0.000000 | 1.00 | 0.0000 | 220 | 0 | 30 | 1430 | 0.4222 | 2014 | 1867 | 1668 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| FoxyriaR | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 270 | 20 | 70 | 470 | 0.4093 | 2022 | 950 | 866 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| cvtejeen | 16 | 0.000000 | 0.00 | 0.1374 | 170 | 20 | 380 | 0 | 0.2946 | 2021 | 456 | 531 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

| berisikok | 0 | 0.000000 | 0.00 | 0.0000 | 0 | 70 | 220 | 10 | 0.2773 | 2012 | 49 | 47 | Personal | Nano Influencer |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rukmana, P.U.; Lubis, M.; Fakhrurroja, H.; Asriana; Muttaqin, A.N. Ontology-Driven Emotion Multi-Class Classification and Influence Analysis of User Opinions on Online Travel Agency. Future Internet 2025, 17, 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120582

Rukmana PU, Lubis M, Fakhrurroja H, Asriana, Muttaqin AN. Ontology-Driven Emotion Multi-Class Classification and Influence Analysis of User Opinions on Online Travel Agency. Future Internet. 2025; 17(12):582. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120582

Chicago/Turabian StyleRukmana, Putri Utami, Muharman Lubis, Hanif Fakhrurroja, Asriana, and Alif Noorachmad Muttaqin. 2025. "Ontology-Driven Emotion Multi-Class Classification and Influence Analysis of User Opinions on Online Travel Agency" Future Internet 17, no. 12: 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120582

APA StyleRukmana, P. U., Lubis, M., Fakhrurroja, H., Asriana, & Muttaqin, A. N. (2025). Ontology-Driven Emotion Multi-Class Classification and Influence Analysis of User Opinions on Online Travel Agency. Future Internet, 17(12), 582. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi17120582