Abstract

This paper presents the development and validation of an IoT-enabled temperature-sensing device for real-time monitoring of the thermal insulation properties of glass windows. The system integrates contact and non-contact temperature sensors into a compact PCB platform equipped with WiFi connectivity, enabling seamless integration into smart home and building management frameworks. By continuously assessing window insulation performance, the device addresses the challenge of energy loss in buildings, where glazing efficiency often degrades over time. The collected data can be transmitted to cloud-based services or local IoT infrastructures, allowing for advanced analytics, remote access, and adaptive control of heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems. Experimental results demonstrate the accuracy and reliability of the proposed system, confirming its potential to contribute to energy conservation and sustainable living practices. Beyond energy efficiency, the device provides a scalable approach to environmental monitoring within the broader future internet ecosystem, supporting the evolution of intelligent, connected, and human-centered living environments.

1. Introduction

Temperature-sensing devices have been widely employed in the fields of medicine, industry, agriculture, and other areas and have become the principal method of information collection due to the rapid development of microelectronics and sensor technology. These sensors are placed at key locations within the monitored area to capture thermal characteristics with high accuracy, and then are usually transmitted to users via wireless communication equipment [1,2]. Distributed temperature sensors with high processing capability and low power consumption are used in smart homes, and they can capture data on a resident’s interactions with the environment [3]. These settings are designed to recognize situations to support users in their daily activities and offer smart solutions to some of the issues brought on by the expanding population [4].

These devices can be utilized to lower the energy consumption of building components that may lose their insulating capacity over time. The most vulnerable component of the building is the window where the outside protective structure’s heat insulation is the weakest. Additionally, it is a crucial tool for visual performance, which contributes significantly to building energy savings. Contradictions exist between energy consumption, visual performance, and thermal environment because of the weather and sun radiation. Consequently, an efficient optimization technique is required to optimize the mentioned parameters. Most of the studies that are now available for window design concentrate more on the examination of energy consumption performance. Additionally, the best way to arrange windows and a shading system with various climatic zones and orientations has been determined. The building’s energy use has increased significantly in recent years. A recent study [5] stated that 36% of the world’s energy usage and carbon emissions have been attributed to it. Due to a lack of energy and high energy prices, the modern building industry is paying increasing attention to energy efficiency. Countries have implemented relevant energy-saving regulations and policies, and energy efficiency as an aspect of architectural design is a crucial factor [6].

Moreover, purpose design can be seamlessly integrated into smart home systems by IoT technologies, enabling additional functionalities such as heating control, energy management, and other smart home applications [7]. This multifunctional approach enhances the overall utility of such systems, making them adaptable to various user needs. To achieve this level of functionality, researchers frequently employ platforms like Arduino or Raspberry Pi, which provide the computational power and flexibility required to meet the system’s demands [8,9]. These platforms enable the creation of advanced, integrated devices that combine energy efficiency with smart home capabilities.

Multi-Layer Glazing

Nowadays, most of the windows in private or industrial areas are made of multi-layer glazing, which has excellent thermal insulation. Moreover, the space between the two glass panels is filled with special gas to reduce the thermal conductivity between these glass panels [10]. Most commonly used internal gases in multi-layer glazing are argon (Ar) and krypton (Kr), which have better insulating properties than ordinary air [11].

Contemporary insulators include vacuum insulation panels [12], gas-filled panels, aerogels [13], and thermal insulation materials. The primary characteristics of insulating materials include very low thermal conductivity and their potential transparency. The authors of [14,15] point out that the gas will leak over time. The rate of leakage depends on the production quality of the window, installation, the building’s climate, including its exposure to the sun and altitude, and other factors. Even after several years of gradual depressurization, a window can be expected to maintain its properties and effectiveness. The stress between the glass panels and the seal due to cyclic thermal loading causes the deformation and weakening of the seal, which leads to the infiltration of gases into the glass chamber. This can lead to the dilution of the inert gas concentration [16].

There are two key components of the multi-layer glazing construction. The first one consists of glass panels that are attached together by a frame and special glue. A special gas is used to fill the space between the glass panels, reducing the thermal conductivity of the area between two or more glass panels [17]. For example, argon gas is heavier than oxygen and has less energy and heat transmission than diatomic molecules. The second component is the plastic frame that holds the glass panel. Typically, the structure is separated into multiple chambers to increase insulation properties [18].

The gas leakage or the deterioration of the inner gas properties inside the multi-layer glazing is very difficult to measure or evaluate. One possible way to measure the gas properties between two glass panels is to place a sensor inside the gap during the assembly. Another way is to place the needed sensor inside the multi-layer glazing, where it can measure environmental variables, as well as the temperature.

This study presents a compact environmental monitoring system for multi-layer glazing, capable of measuring both contact and gas temperatures. The versatile temperature-sensing device supports various IoT and smart home applications, enhancing energy efficiency and offering valuable insights into long-term insulation property trends.

2. Related Work

Several authors have addressed heat transfer in multi-layer glazing systems using thermocouples. The authors of [19] used several thermocouples to measure the temperature inside triple-chamber glazing. Two thermocouples were placed inside each cavity to measure the heat transfer through the glazing. However, this research focuses on the comparison of the thermal performance of four triple-glazed window configurations (TG, TG-LW, TG-PCM, TG-LW-PCM) in the range from 20 °C up to 50 °C. Another author [20] used a similar approach by using the TRNSYS program within a temperature range from 17 °C up to 40 °C with an additional cooling phase. The authors of [21] used different simulation models for glazing windows filled with a special phase change material. These authors have stated that accurate thermal monitoring within the glazing system requires measuring the glass panel’s contact temperature and the air temperature inside the cavity.

A practical approach is to use a compact sensor module mounted on a small PCB. Thermocouples or resistance temperature detectors are ideal due to their minimal thermal mass and fast response time for contact measurement of the temperature. Digital sensors like BMP280 offer high accuracy and low power consumption for temperature measurement [22]. Moreover, the sensor is very small with dimensions of 2.5 × 2.5 × 1 mm [23], and it is suitable for temperature measurement, which is used as a basis task for this research.

Furthermore, the authors of [24] proposed integrating ultra-thin flexible temperature sensors laminated directly onto the glass surface to minimize disturbance of the thermal field while enabling high-resolution spatiotemporal monitoring. Other research [25] has focused on wireless passive sensors, such as RFID-based temperature probes, which can be hermetically sealed within the glazing cavity during manufacture. Furthermore, machine-learning-assisted interpretation of temperature profiles has been investigated as a method for estimating the remaining insulating lifespan of glazing systems under varying environmental loads [26]. These solutions demonstrate the growing interest in non-intrusive diagnostic tools capable of detecting changes in thermal properties.

3. Materials and Methods

This section outlines the materials, experimental setup, and analytical methods employed to evaluate the thermal and environmental performance of the proposed system. The research integrates advanced simulation techniques with controlled physical experiments to provide a comprehensive understanding of the heat transfer dynamics, sensor functionality, and overall energy efficiency of the window.

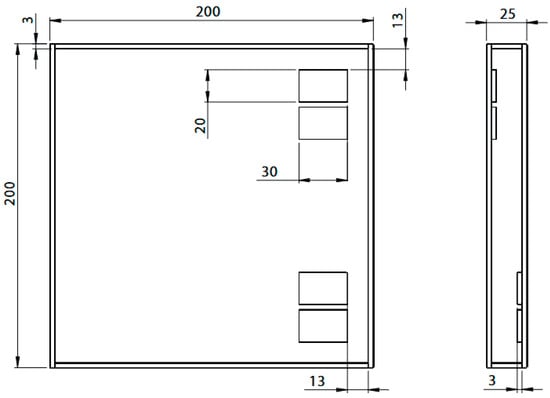

In common applications, such a window is intended to have dimensions of up to several meters, reflecting the standard sizes commonly used in building construction for energy-efficient glazing systems. This full-scale design would allow for a comprehensive evaluation of the window’s performance in practical scenarios, including its thermal insulation capabilities and integration with building management systems. However, for this research, a scaled-down model with dimensions of 200 × 200 mm was designed. This smaller prototype was designed to replicate the essential features of the larger window while remaining applicable for computational simulations and laboratory experiments. The reduced size enabled temperature control over the experimental conditions and facilitated the efficient application of computational fluid dynamics (CFD) techniques, which require detailed meshing and significant computational resources.

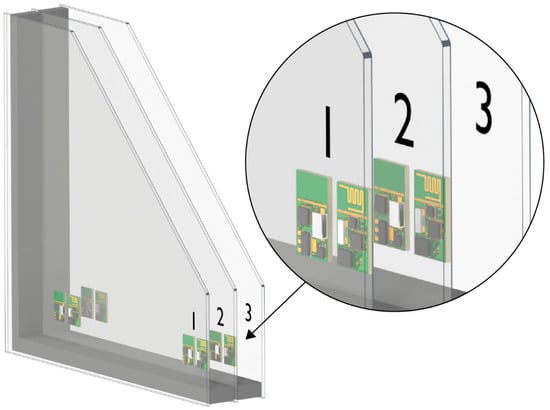

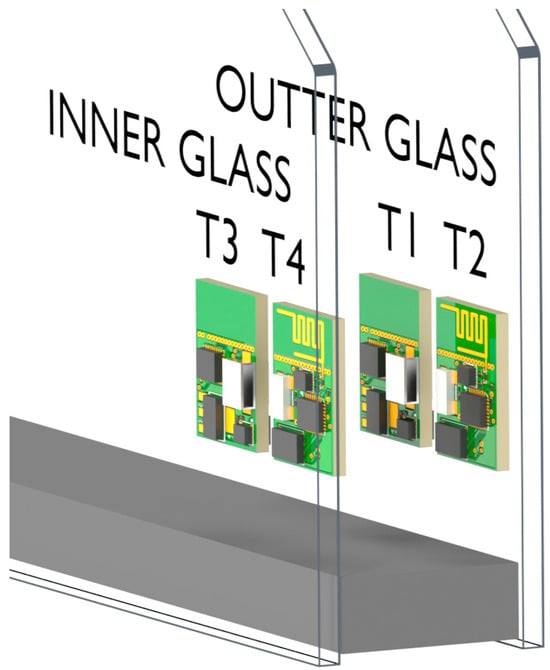

The designed system in the form of several printed circuit boards (PCBs) (Printed s.r.o., Melnik, Czech Republic) with sensors is placed inside the glazing on the inner and outer glass panels. Two boards were placed on each glass panel, where all boards consisted of the microcontroller with a wireless communication interface and a pair of BME280 environmental sensors (Printed s.r.o., Melnik, Czech Republic). All boards were glued to the side of each glass panel for temperature measurement. Each sensor was strategically positioned on the board, ensuring accurate readings of both indoor and outdoor environmental conditions. The sensors operate within a wide temperature range, making them suitable for measuring environmental conditions. The concept can be extended to any number of chambers, where each chamber needs to have four boards. The proposed concept is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The concept of temperature-sensing device design placed in multi-layer glazing.

The proposed system was designed to seamlessly integrate with modern building management systems. It can provide real-time environmental data to optimize heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) operations, reducing energy consumption and improving. In this research, a compact model facilitated the setup of controlled thermal gradients and sensor measurements, ensuring accurate data collection without the logistical challenges associated with handling a full-sized window. Despite its smaller dimensions, the prototype maintained the key characteristics of the larger window, including gas-filled gaps and integrated sensors for temperature. By scaling down the window for this study, it was possible to test its performance while ensuring that the results could be extrapolated to a full-scale implementation. This approach provided a practical and efficient pathway to validate the system’s functionality and establish its potential for energy efficiency applications. The scaled-down model for both scenarios can be found in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The scaled-down model of the single-layer glazing.

The chamber system incorporates standard glass panels with gas-filled gaps to enhance thermal insulation. Each panel was made from low-emissivity glass, which reduces heat transfer and improves energy efficiency. The inner and outer panels are coated with a thin metallic layer to reflect infrared radiation, while the middle panels are left untreated to facilitate temperature distribution analysis. The frame between the panels was constructed from aluminum, and the sealing material ensures airtightness to maintain consistent environmental conditions within the gaps. The list of material properties of the single-layer glazing is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Material properties of the single-layer glazing.

3.1. Setup for the Real Experiment

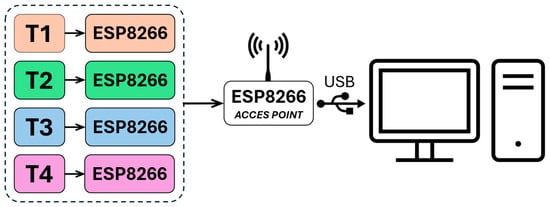

In the experimental setup, each embedded ESP8266-based sensing board (Printed s.r.o., Melnik, Czech Republic) communicated with a nearby ESP8266 access point positioned 1 m from the glazing surface. Although the PCB was installed inside the window cavity, the short transmission distance ensured stable WiFi connectivity throughout the entire measurement period. While full RF characterization (RSSI, packet loss rate, or latency under varying thermal conditions) was not performed, the stable operation at this range is consistent with typical ESP8266 performance, where RSSI values around −40 to −55 dBm are expected at a line-of-sight distance of 1 m, even with moderate attenuation from glass. For data transmission, each embedded board operated as an independent client node. Outside the glass panel, an additional ESP8266 module was configured as a WiFi access point (AP) acting as the central server. During the experiment, all boards established a wireless connection to this AP and periodically transmitted their measured temperature values. The access point was connected to a PC, where all incoming data were collected and stored for further analysis. This architecture enabled reliable communication between the sensor boards and the data acquisition system without requiring any physical data cables within the window chamber (Figure 3). No data retransmissions or communication interruptions were observed during the experiment, indicating that the system remained sufficiently reliable for continuous temperature reporting over this short-range link.

Figure 3.

Communication architecture of the proposed system.

3.2. Temperature Sensors for Glazing Applications

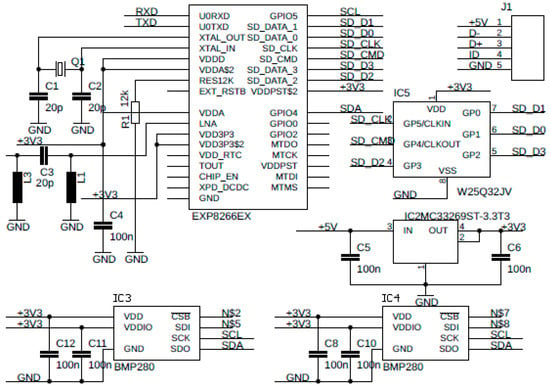

The core of the system is based on the ESP8266 microcontroller, chosen for its reliability and flexibility in handling sensor data and wireless communication. It supports low-power operation to align with the energy efficiency goals of the smart window. The microcontroller’s firmware is programmed to process sensor data, namely the temperature received from the connected sensors. The schematic part of the board can be found in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The schematic design of the board embedded into a single −layer glazing.

The board has all the components necessary for external and internal communication. The main microcontroller placed on the board, ESP8266, is responsible for internal communication with sensors, and it is also responsible for external wireless communication. It uses the 40 MHz crystal for the lower power voltage of 3.3 V. All components use the I2C communication interface, which is used for communication between the sensors and the main microcontroller. The main microcontroller has a small package, an important communication interface, and sufficient computing power.

The input voltage of +5V for the whole device is supplied by the USB terminal, and it must be converted to +3V3, which is suitable for the different components in the design. It also has the input and output sets of the capacitors, which can smooth the output voltage in case of a sinusoidal input. The final physical design of the PCB must be small enough to fit in the gap inside the window frame. In the study by Osorio-de-la-Rosa et al. [27], a comparable compact IoT sensing platform is presented, where the complete wireless sensor is implemented on a 20 × 20 mm PCB. This provides a useful engineering benchmark for the required miniaturization of embedded sensing electronics. In our case, although the ESP8266 module imposes slightly larger spatial requirements, the resulting PCB layout of 20 × 30 mm remains within the dimensional limits of the glazing cavity and satisfies the constraints for integration inside the window chamber. The terminal for the USB interface is placed at the edge of the mainboard. The Wi-Fi antenna is located on the top part of the PCB.

3.3. Manufacturing Process of the Single-Layer Glazing

The designed boards were manufactured from a composite material FR-4 1,5/Cu 35 µm, which is a usual material and can be manufactured by a common manufacturer on the market. The soldering of the components on the board is also a standard procedure. For this research, the components were soldered on the board by an external manufacturer. Figure 5 presents a sectional view of a single-glazed window, illustrating the placement of four temperature sensors (T1–T4) used for thermal analysis.

Figure 5.

The placement of the sensors inside the single-layer glazing.

Two boards were positioned on the outer glass panel: T1, which measured the temperature of the outer glass surface, and T2, which measured the temperature of the environment close to the outer glass. On the inner glass panel, T3 measured the environment temperature near the inner glass, while T4 measured the temperature of the inner glass surface. This setup enabled a detailed evaluation of heat transfer across the window, capturing temperature variations between the inner and outer environments and assessing the insulating performance of the gas between the glass panels.

All boards with sensors and other electronic components were embedded into the chamber of the window in the fabrication process, where the boards were attached to the glass panels. A heat-conducting adhesive was used for attaching the boards to the glass panels. For the experiments, the boards were powered using an ultra-thin flexible PCB cable. Its minimal thickness ensured that it did not create a significant thermal bridge inside the window chamber, allowing the temperature measurements to remain unaffected by heat conduction from the power supply. Once the boards were glued to the glass panel and connected via the flexible strip, the aluminum frame could be placed along the edges of the glass panel. Finally, the second glass panel could be placed on the frame with the boards closed inside. The same manufacturing process can also be used for multi-layer glazing.

3.4. Experimental and Simulation Approaches

To comprehensively evaluate the thermal insulation properties of the developed temperature-sensing device, two complementary approaches were employed: computational modeling and laboratory testing. First, a Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) simulation was carried out to analyze heat transfer mechanisms and temperature distribution across the single-glass window under controlled boundary conditions. This allowed for a detailed examination of thermal behavior without external disturbances. Second, a real experimental setup was designed to validate the simulation results under practical conditions, using heated air and integrated sensors to measure thermal responses of the glazing system. Together, these approaches provided both predictive insights and empirical verification, ensuring robust assessment of the device’s performance.

3.4.1. Solution Approach Using CFD Simulation

The performance of the smart window system was evaluated through CFD simulation. The window was designed as a single-glazed structure equipped with integrated sensors to monitor the surface temperature of the environment inside the window. These sensors were strategically placed to capture accurate data across the window. The primary goal of the analysis was to investigate the heat transfer characteristics across the single-layered construction of the window. Additionally, the study aimed to determine the temperature distribution at specific measurement points, including the inner and outer surfaces of the glass layers and the air cavities in between.

The operating conditions were selected to simulate realistic environments. The outdoor air temperature range was set from 0 °C up to 73 °C, while the indoor air temperature was set to 15 °C, reflecting an indoor environment. These temperatures created a gradient, enabling the assessment of thermal performance under challenging conditions. This approach ensured that the results were relevant to real scenarios and could contribute to the development of energy-efficient glazing systems.

The CFD simulation was designed to achieve a detailed analysis of the thermal performance of the window system. To provide a more accurate representation of the thermal environment, two distinct regions were created within the model. The inner region represented the indoor space adjacent to the window, while the outer region represented the outdoor space exposed to external environmental conditions. In both regions, low-intensity airflow was assumed to mimic natural convection effects. The equation that represents the conservation of energy in a physical system and is crucial for understanding heat transfer is listed in Equation (1).

Equation (1) balances the total energy within a system by accounting for energy storage, transport, and sources. This balance is vital in applications such as thermal analysis of materials, fluid dynamics, and the design of systems such as energy-efficient windows.

The left-hand side of the equation expresses energy storage and transport. The first term denotes the rate of change of total energy (internal plus kinetic) within the system, showing how energy is accumulated or depleted over time. The second term represents convective transport, where fluid motion carries energy in the form of enthalpy and kinetic energy. Together, these terms describe how energy evolves and moves through the system.

The right-hand side accounts for mechanisms of energy transfer and generation. The first term corresponds to heat conduction, governed by Fourier’s law, which drives heat flow through temperature gradients. The second term captures energy transport due to mass diffusion, as different species in a mixture contribute to the balance. The third term reflects viscous dissipation, where internal friction converts mechanical energy into heat. Finally, the volumetric source term includes additional energy inputs or losses, such as those from radiation, chemical reactions, or electrical processes.

To investigate the heat transfer and thermal insulation performance of the proposed smart window system, a comprehensive computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation was conducted, closely aligned with the experimental configuration. The digital model was constructed to replicate the physical test sample in all key geometric and material aspects, ensuring that the simulation results would be directly comparable to empirical data.

The CAD model defined all relevant physical domains: solid components, such as the glass panes, the structural aluminum frame, and the printed circuit boards (PCBs) housing the sensors, as well as multiple fluid zones representing the interior room air, the external environment, and the insulating cavity between the glass layers. The spatial placement and thickness of each domain strictly followed the actual test specimen, with precise accommodation of the sensor boards’ geometry, since their thermal interaction with the glazing system may influence local heat flow and temperature gradients.

The computational mesh was generated using Ansys Fluent (version 2024R1), leveraging polyhedral elements to achieve greater flexibility and accuracy in modeling complex geometries and fine structures. The total mesh density reached 13.3 million cells, with targeted refinement in regions of expected high thermal gradients and velocity shear, notably within the insulating cavity and near the sensors. Throughout the mesh generation process, particular attention was paid to the wall-adjacent flow zones, reflected in adaptive local refinements based on the evolving wall function parameter Y+, which was carefully constrained to remain below 1. Whenever steeper gradients developed during the simulation, automated mesh adaptation further improved local resolution. Mesh-independence was assessed through simulations on several mesh densities; when increasing the mesh density led to negligible variation (below 2%) in the tracked temperatures and heat flows, the grid was deemed sufficiently converged for reliable results.

The CFD solver setup was based on a pressure-based, pseudo-transient approach, utilizing a relaxation factor of 0.5 to ensure numerical stability while capturing the thermal dynamics efficiently. Pressure–velocity coupling employed the pseudo-transient scheme, with momentum and energy equations discretized at second-order upwind accuracy, and pressure discretization set to the body-force-weighted scheme. Radiative transfer was included using the Discrete Ordinates (DO) model, discretized at first order upwind. These choices guaranteed sufficient accuracy for both strong transient behavior and smooth propagation of heat fronts through solid and fluid regions.

A detailed analysis of the flow regime was conducted prior to simulation via computation of dimensionless numbers—Prandtl, Grashof, and Reynolds—for each fluid domain. While laminar conditions prevailed in some smaller cavities, most regions experienced transitional or low-turbulence flow due to the imposed thermal gradients and geometric constraints. Accordingly, the k-ω SST turbulence model was selected for its well-documented ability to handle both laminar-to-turbulent transitions and near-wall effects accurately, ensuring robust simulation of convective heat transfer.

Material properties were defined with high fidelity: air was modeled as an incompressible ideal gas, with temperature-dependent density (using the NASA 9-piecewise polynomial function for specific heat) and thermal conductivity (calculated by kinetic theory), while dynamic viscosity followed Sutherland’s law. Solid domains, including glass, aluminum, and PCBs, were assigned literature-based values for density, specific heat capacity, and thermal conductivity. Of particular importance is that the thermal contact resistance between the sensor PCB and the inner glass surface was physically modeled as a thin resistive layer, corresponding to the heat-conducting adhesive used in the assembly, with resistance values matching manufacturer data (~0.0015 m2K/W), a factor shown to be critical in local thermal dynamics.

Boundary and initial conditions were rigorously derived from the experimental protocol. The window system’s outer surface was exposed to a controlled heating ramp, starting at 3 °C and rising to 73 °C according to the linear formula theat = 0.031 [°C s−1] * t + 3 [°C]. Ambient temperature was maintained at 11 °C for both interior and exterior domains. Gravity acted in the negative y-direction, instigating natural convection within the air cavities and ensuring that buoyancy-driven flows reproduced their real-life counterparts. All initial temperatures within fluid and solid domains matched their respective ambient conditions.

Time-stepping was assigned with great care to ensure numerical robustness. The minimum characteristic length scales-primarily the thicknesses of the glass and PCB-dictated a strict maximum stable time-step via the CFL criterion, found to be approximately 3 s. The simulation adopted an adaptive approach; initial highly transient phases were resolved with a time-step of 0.005 s to accurately capture rapid changes, after which the step size was gradually increased to 0.5 s as gradients stabilized. For every time step, 20 solver iterations were performed, and key residuals were tightly controlled: energy equations required convergence below (10−6) to (10−7), while other equations converged below (10−4) to (10−5). Additionally, heat flow and temperature changes were monitored to ensure solution change below 1% between iterations.

Throughout the simulation, critical quantities were continuously monitored—sensor temperatures, maximum and average temperatures across each component, heat fluxes through the glazing system, and maximum flow velocities within the fluid domains. These data streams enabled both local and global validation against experimental measurements and facilitated multipoint comparison of temperature trajectories over time. The entire post-processing procedure was carried out using Ansys Fluent’s suite of visualization and analysis tools.

This sophisticated computational approach, with the rigorous definition of all mesh, solver, boundary, and material parameters, guarantees methodological transparency and reproducibility. By capturing and quantitatively evaluating heat transfer phenomena at high spatial and temporal acuity, the CFD simulation provides a solid foundation for direct comparison with experiment and ensures the scientific credibility of all subsequent claims regarding the insulation performance and dynamic behavior of the smart window system.

3.4.2. Solution Approach Using Real Experiment

The experimental setup was designed to closely replicate the boundary conditions of the computational model. Hot air was used as the heat transfer medium. An electric oven was used to uniformly heat the outer glass panel from 0 to 73 °C. The manufactured boards with temperature sensors were placed on the glass surfaces within each chamber and secured with heat-conductive adhesive to ensure accurate data collection.

The experiment was conducted in a controlled laboratory environment at a constant temperature of 15 °C and 50% relative humidity, eliminating external variables such as ambient temperature fluctuations. The air temperature was monitored with a digital thermometer and heated incrementally to minimize thermal shock and accurately observe the glazing’s response. This controlled setup ensured reliable results focused solely on the interaction between the glazing and the heated air.

3.5. Temperature Sensor Calibration

The temperature sensors BME280 used in the prototype were calibrated prior to the experiment using a traceable reference thermometer (accuracy ±0.1 °C, ISO/IEC 17025 [28] certified). The calibration was performed inside a temperature-controlled chamber in the range of 10–80 °C, which corresponds to the expected operating conditions of insulated glazing units. A total of eight calibration points (from 10 °C to 80 °C) were selected with a dwell time of 10 min at each temperature to ensure thermal stabilization.

At every calibration point, five repeated measurements were taken to evaluate sensor repeatability, for which the coefficient of variation remained below 0.2%. A linear regression model was used to fit the measured values to the reference instrument, as no significant nonlinearity was detected within the calibration range. The resulting correction factor (slope and offset) was applied during the data-processing stage.

The expanded measurement uncertainty (k = 2) of the calibrated sensors was estimated to be approximately ±0.25 °C by combining reference instrument uncertainty, chamber stability, and sensor repeatability. Potential hysteresis effects were assessed by repeating the calibration cycle in reverse order (cool-down), with maximum observed deviation not exceeding 0.1 °C, indicating negligible hysteresis for the intended application.

To evaluate the influence of integration into the glazing system, a post-embedding verification was performed by comparing the calibrated sensor output against the reference thermometer after mounting the PCB inside the glass cavity. An additional offset of 0.1–0.2 °C was observed, attributed to conductive and radiative coupling with the PCB–adhesive–glass stack; this offset is included in the uncertainty budget. No measurable drift was detected during the 24 h experimental period.

3.6. Impact of Miniaturization on Measurement Accuracy

The integration of electronic components inside the glazing cavity imposes strict constraints on device miniaturization, which directly affect thermal accuracy, measurement dynamics, and wireless communication performance. The PCB must remain as small as possible to minimize the thermal disturbance introduced into the cavity. A larger board increases thermal mass and alters the local heat distribution, potentially biasing the temperature readings. As shown in recent compact IoT sensing platforms [27], PCB footprints on the order of 20 × 20 mm are feasible and help reduce thermal inertia. In the present design, the use of ESP8266-based electronics required a slightly larger footprint of 20 × 30 mm, which still fits within the glazing gap while keeping added thermal mass low.

Copper density on the PCB is also a critical factor; high copper coverage increases heat spreading and slows sensor response. To minimize this effect, only essential copper traces were used, and no ground plane was placed directly under the temperature sensor. The selected FR-4 substrate (1.0 mm thickness) (Printed s.r.o., Melnik, Czech Republic) limits thermal conduction while providing sufficient mechanical support. Similarly, SMD package size affects thermal inertia; the BME280 sensor in its LGA package exhibits low thermal mass, enabling a rapid response to changes in air temperature within the glazing cavity.

The adhesive layer used for mechanical fixation introduces additional thermal resistance. To reduce offset effects, a thin, low-conductivity optical adhesive was applied only at the PCB perimeter, avoiding direct contact with the sensor region. Pre- and post-embedding calibration confirmed that adhesive-induced offsets remained within the expected uncertainty range.

From an IoT standpoint, proximity to glass and metallic window frames may detune the PCB antenna and attenuate the Wi-Fi signal. Although the communication distance in the experiment was only 1 m, RSSI remained stable, indicating that the PCB-mounted antenna performed reliably despite the confined environment. Future iterations may employ antenna matching or external antenna routing to further mitigate detuning.

3.7. Influence of Embedded Electronics on the Thermal Field

Embedding active electronics inside the glazing cavity introduces localized heat sources that can affect temperature measurements if they are not properly controlled. Although the ESP8266 and the associated voltage-regulation circuitry dissipate heat during operation, several measures were taken to minimize their impact on the thermal field. First, the boards were operated with a low-duty communication cycle, and during the experiment, the Wi-Fi transmission load was minimal because the access point was located only 1 m from the window chamber. As a result, RF-related heating was negligible, and no observable temperature steps correlated with transmission activity were detected in the recorded data.

To further limit electronics-induced heating, the voltage regulator and power distribution traces were placed away from the sensor region, and the BME280 was positioned on the thermally isolated edge of the PCB. Thermal mass was minimized through reduced copper coverage and a compact 20 × 30 mm board layout. Measurements performed with the system idle (no Wi-Fi transmission) showed no measurable offset compared with fully active operation, indicating that self-heating remained below the sensor’s uncertainty range.

The flexible PCB power cable used in the experiment introduced an insignificant thermal bridge due to its very small cross-section, preventing heat conduction from external equipment into the cavity. Overall, the observed thermal gradients were dominated by the glazing behavior rather than the electronics, and the implemented design practices effectively limited hardware-related thermal bias.

4. Results and Discussion

The results from the simulation and the experiment provide valuable insights into the performance of the thermal conductivity in the window, demonstrating the effectiveness of the single-layer glazing design in energy-efficient thermal insulation. The main objective of this study was to validate the simulation model using experimental data, ensuring that the computational predictions were aligned with the observed behavior.

4.1. Results Using CFD Simulation

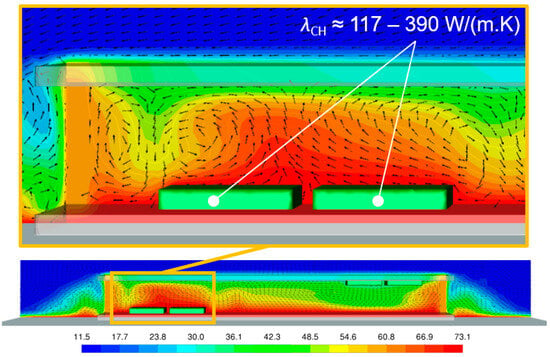

The CFD simulation revealed a distinct temperature gradient across the glazing chamber, increasing steadily from the cooler interior toward the heated exterior panel. Within the air gap, buoyancy-driven circulation developed as warmer, less dense air rose and cooler, denser air sank, creating a continuous convective loop. Similar natural convection phenomena in enclosed cavities have been widely reported in recent CFD studies, such as [29], confirming that buoyancy effects dominate heat transfer within narrow glazing gaps.

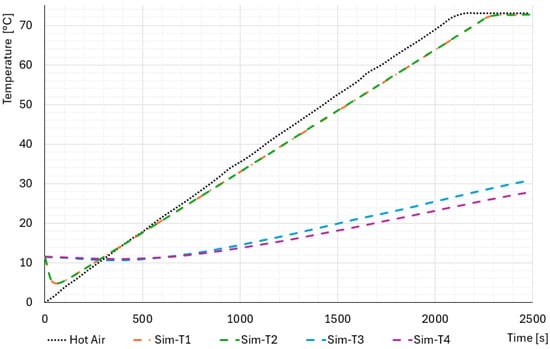

The transient behavior of the simulated sensors further illustrates this effect. Sensor Sim-T1, located closest to the heated panel, recorded the fastest temperature rise, while Sim-T4, positioned near the opposite side, responded more slowly. This delay reflects the time required for heat to propagate through the gas and glass layers. Comparable delays in transient sensor response have been noted in [30], where gas conduction and convection govern thermal dynamics. The outcome of the simulation model can be found in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The outcome of the CFD simulation model.

The graph in Figure 6 illustrates the temperature progression over time as heat was gradually applied to the outer side of the glass panel. The x-axis represents time in seconds, while the y-axis shows temperature in degrees Celsius. The lines labeled Sim-T1, Sim-T2, Sim-T3, and Sim-T4 correspond to the readings from four simulated sensors placed within the chamber, capturing the heat transfer through the cavity gas from the heated panel to the opposite panel. The black line represents the medium temperature of heating.

These results not only validate the physical accuracy of the simulation but also align with advanced 3D CFD investigations of window systems, which emphasize the importance of convective and conductive interactions across both glazing cavities and frame structures [31]. Together, the findings reinforce that CFD is a reliable tool for predicting the thermal behavior of glazing systems and for identifying areas—such as cavity convection and frame conduction—that strongly influence insulation performance.

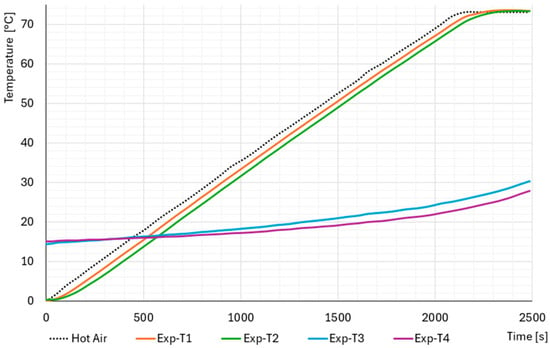

4.2. Results Using Real Experiment

The heating source used in the experiment was a laboratory oven, where one of the side panels was removed and replaced by the tested glazing chamber. In this configuration, the inner side of the chamber was exposed directly to the controlled hot-air environment inside the oven, while the outer side remained in contact with ambient room air, enabling a well-defined temperature gradient across the window. The oven’s heating element ensured stable and uniform thermal conditions on the hot side, while no forced convection was applied; thus, heat transfer occurred under natural convection on both sides. The temperature distribution was recorded over time using four sensors placed within the chamber. As heating progressed, the air temperature within the chamber steadily increased, and heat flowed through the glazing as sensed by the temperature sensors. Sensor T1—closest to the heated outer panel—records the most rapid increase, while T4, located near the inner side, responds more slowly. This gradient underscores that ordinary air, with its higher thermal conductivity, transfers heat more quickly across the cavity than inert gases would. In fact, Cho et al. [32] reported that reducing the argon filling rate from 95% to 0% led to roughly a 10.9% decline in thermal performance, corroborating our findings of accelerated heat transfer with air-filled gaps. Additionally, recent work by Rimshin et al. [33] highlights the effectiveness of inert gas fillings and thermal coatings in improving window insulation. These external studies align well with our high-resolution, second-by-second temperature data, reinforcing that using low-conductivity gases is key for enhancing the thermal efficiency of single-layer glazing systems.

The graph in Figure 7 demonstrates a consistent temperature gradient, with all sensors showing a steady rise in temperature over time. The steeper slopes of the sensor readings compared to experiments with inert gases highlight the reduced insulation properties of air, emphasizing the importance of using low-conductivity gases in glazing systems for enhanced thermal insulation. The data collection process captured detailed thermal performance metrics of the single-layer glazing system, with temperature measurements taken every second for high-resolution results. Calibrated sensors and a data logger ensured accurate and continuous data recording, which was analyzed using software to visualize temperature trends in graphical form.

Figure 7.

The outcome of the experiment with the heated air.

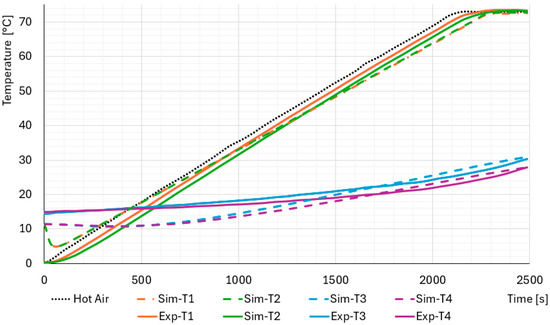

4.3. Comparison Between CFD Simulation and Real Experiment

The mathematical model and equations used in the simulation were validated through experimental testing to assess their accuracy in predicting thermal behavior. The experiment replicated the simulated conditions by gradually heating one side of the chamber and measuring the heat transfer through the glazing using several temperature sensors. The comparison between simulated and experimental results demonstrated a strong correlation, confirming the reliability of the model. A key finding was the measured temperature difference across the glazing, which plays a crucial role in thermal insulation. This difference directly influences the effectiveness of the window in minimizing heat loss, making it a critical factor in energy-efficient building design.

The simulation results revealed clear temperature gradients across the chamber of the window, with the outer glass panel exposed to the rising temperature, where the outer glass panel reflected the rising temperature, the middle air gap exhibiting moderate temperatures, and the inner glass panel showing the lowest temperatures. These findings were consistently mirrored in the experiment. Temperature measurements taken from the physical prototype confirmed the predicted thermal behavior, with each chamber displaying distinct temperature zones that corresponded closely with the simulation data. The comparison between the simulation and the experiment is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison between the CFD simulation and the experiment.

The graph in Figure 8 presents the temperature evolution over time, illustrating the thermal insulation properties of the window. The x-axis represents time in seconds (0–2500 s), while the y-axis shows temperature in degrees Celsius (0–73 °C). A dotted black line represents the reference temperature of the air, which increases steadily. Experimental (Exp) and simulation (Sim) data are provided for four measurement points (T1–T4), with experimental values shown as solid lines and simulated values as dashed lines. The temperature trends indicate that T1 and T2 experience a rapid increase, closely following the air temperature. In contrast, T3 and T4 exhibit a significantly slower temperature rise, indicating thermal resistance. The close alignment between experimental and simulated data confirms the accuracy of the computational model.

The simulation also revealed that the temperature sensors themselves contributed to heat conduction within the system. The heat from the glass was transferred to the sensors, which then acted as a thermal bridge, conducting heat into the chamber. This unintended behavior introduced an additional pathway for heat transfer, potentially affecting the accuracy of the measurements. Such sensor-induced heat conduction is undesirable, and it can change the thermal dynamics of the glazing system and introduce errors in the experimental data. These findings emphasize the need for careful sensor design and placement to minimize their impact on the system’s thermal performance.

4.4. Quantitative Validation Metrics

To provide a rigorous evaluation of the agreement between the CFD simulation and the experimental measurements, a quantitative comparison was performed using common statistical error metrics. For each temperature sensing position (T1–T4), the root-mean-square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), bias error, and Pearson correlation coefficient r were computed based on paired experimental and simulated temperature data. These metrics allow for the assessment of absolute accuracy (RMSE, MAE), systematic over- or underestimation (bias), and temporal agreement in dynamic response (r).

The results show a high correlation between the simulated and measured temperature curves (r ≥ 0.98 for all measurement points), indicating that the CFD model accurately reproduces the temporal evolution of the thermal process. The RMSE values range from approximately 2.9 °C to 3.3 °C, and the MAE varies between 2.3 °C and 2.7 °C across all sensors. The bias values remain between −2.1 °C and +1.4 °C depending on the sensor location, demonstrating that the model does not exhibit any substantial systematic offset. Overall, these quantitative results confirm that the simulation provides a reliable approximation of the thermal behavior observed in the experiments.

4.5. Heat Circulation and Thermal Bridges in the Chamber

The simulation results revealed that the spacer frame connecting the two glass panels acts as a significant thermal bridge within the system. Heat conduction through the frame and adjacent glass edges creates an additional pathway for thermal transfer between the inner and outer surfaces. This effect reduces the overall insulation efficiency of the glazing unit, as more heat can escape or enter the chamber. The airflow visualization further illustrates the presence of convection currents that circulate warm air across the chamber, intensifying heat exchange near the edges. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing spacer frame materials and geometry to minimize thermal bridging and improve the thermal performance of glazing systems. The temperature distribution and airflow patterns corresponding to this effect are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Visualization of the temperature convection of the CFD simulation.

A key source of discrepancy between the simulation and the experiment arises from the representation of the temperature sensor. In the simulation, the sensor is modeled as a full board, whereas in reality, it has a thickness of only 1 mm. This difference introduces potential errors, as the real sensor possesses thermal mass and can conduct heat between the glass and chamber air, effectively acting as a thermal bridge. Its material composition also enables it to absorb and store heat, slowing its response time and influencing transient readings. Additionally, physical contact with the glass introduces localized thermal resistance not captured in the numerical model. Prior studies confirm that sensor design and thermal inertia significantly affect accuracy; for example, Taler [34] showed that the presence of a thermowell or added mass increases thermal capacitance and delays response, while Małek and Koczyk [35] demonstrated that even small sensor inaccuracies can substantially alter the interpretation of thermal experiments.

Despite certain limitations, the close correlation between simulation and experimental outcomes validates the proposed smart window design. The study revealed areas for refinement, including mitigating the impact of the higher thermal conductivity of air compared to inert gas fills and minimizing the thermal influence of sensors acting as heat bridges. Beyond confirming thermal performance, the integration of IoT functionality enables continuous real-time monitoring, wireless data transmission, and seamless connection with building automation or HVAC systems. This combination of accurate thermal characterization and IoT connectivity demonstrates the potential for scalable deployment in smart homes and buildings, contributing to long-term energy efficiency and sustainable living practices.

5. Conclusions

The integration of multiple sensors into a single IoT-enabled device embedded within glazing represents a significant advancement in building technology and energy management. By combining computational simulations with controlled experiments, this research provides valuable insights into the thermal behavior of glazing materials and the influence of sensor placement on overall performance. The experiments, conducted with air as the heating medium, revealed that the absence of inert gases such as argon or krypton significantly reduces insulation effectiveness due to air’s higher thermal conductivity. Moreover, the study highlighted that the sensors themselves acted as thermal bridges, reinforcing the need for improved sensor design to minimize unintended heat transfer.

Despite these challenges, the strong correlation between experimental and simulated results validates the scalable design of the proposed system. Crucially, embedding a temperature-sensing IoT device within glazing extends its function beyond passive insulation toward active, data-driven building management. Real-time monitoring enables continuous performance assessment, cloud-based analytics, and seamless integration with HVAC control systems, ensuring adaptive energy optimization in smart homes and buildings.

This research demonstrates the feasibility of transforming glazing into an intelligent, connected subsystem within the Internet of Things ecosystem. Such integration not only enhances thermal insulation but also contributes to holistic environmental monitoring, supporting energy-efficient, sustainable, and resilient living spaces. The proposed approach lays the foundation for next-generation smart building solutions, where materials and embedded devices collaborate to actively reduce energy consumption and promote a more sustainable built environment. Future work will focus on testing the connectivity, stability, and operational limits of the device within IoT infrastructures, ensuring robust long-term performance in real-world applications.

Author Contributions

V.M.: conceptualization of the study, methodology development, and manuscript writing. J.V.: administration, reviewing and editing. M.A.: system design, integration of multiple sensors, and experimental setup. P.D.: software implementation, data acquisition, and validation of sensor measurements. P.S.: hardware development, sensor placement optimization, and system calibration. S.D.: data processing, statistical analysis, and interpretation of results. L.K.: writing, reviewing and editing, literature research, and discussion of findings. A.M.: administration, resource allocation, reviewing, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Internal Grant Agency of Tomas Bata University in Zlín, under the project No. IGA/CebiaTech/2024/002.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5) to support the preparation of this manuscript. The tool was employed for language refinement, improving textual coherence, and standardizing references in accordance with the journal’s guidelines. All outputs were thoroughly reviewed, revised, and validated by the authors, who assume full responsibility for the content and integrity of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Gao, C.; Wang, F.; Lin, T.; Chen, Y. An adaptive sliding window for anomaly detection of time series in wireless sensor networks. Wirel. Netw. 2022, 28, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Li, K.; Huang, B.; Cao, Y. A multi-sensor data-fusion method based on cloud model and improved evidence theory. Sensors 2022, 22, 5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, A.; Chen, W. SUNS: A user-friendly scheme for seamless and ubiquitous navigation based on an enhanced indoor-outdoor environmental awareness approach. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, R.A.; Hidalgo, A.S.; Bouguelia, M.-R.; Estevez, M.E.; Quero, J.M. Efficient activity recognition in smart homes using delayed fuzzy temporal windows on binary sensors. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2020, 24, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Si, P.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Huang, C.; Huang, D.; Jin, Z. Study on the effect of radiant insulation panel in cavity on the thermal performance of broken-bridge aluminum window frame. Buildings 2023, 13, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, J. Multi-objective optimization design for windows and shading configuration: Considering energy consumption, thermal environment, visual performance and sound insulation effect. Int. J. Energy Environ. Eng. 2021, 12, 805–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayastha, S.; Upadhyaya, P. Design and implementation of a cost-efficient smart home system with Raspberry Pi and cloud services. In Proceedings of the 2019 Artificial Intelligence for Transforming Business and Society (AITB), Kathmandu, Nepal, 21–23 November 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, Q.-Q.; Ta, Q.-B.; Park, J.-H.; Kim, J.-T. Raspberry Pi platform wireless sensor node for low-frequency impedance responses of PZT interface. Sensors 2022, 22, 9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andreas, C.R.A.; Putra, H.W.; Hanafiah, N.; Surjarwo, S.; Wibisurya, A. Door security system for home monitoring based on ESP32. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 157, 673–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Liu, W.; Su, H.; Wu, X. Numerical analysis on the advantages of evacuated gap insulation of vacuum-water flow window in building energy saving under various climates. Energy 2019, 174, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K.; Kim, L. Optimum design and energy performance of hybrid triple glazing system with vacuum and carbon dioxide filled gap. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantucci, S.; Garbaccio, S.; Lorenzati, A.; Perino, M. Thermo-economic analysis of building energy retrofits using VIP—Vacuum insulation panels. Energy Build. 2019, 199, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thie, C.; Quallen, S.; Ibrahim, A.; Xing, T.; Johnson, B. Study of energy saving using silica aerogel insulation in a residential building. Gels 2023, 9, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh-Rad, H.; Choudhry, T.A.; Ng, A.W.M.; Rajabi, Z.; Rais, M.F.; Zia, A.; Tariq, M.A.U.R. An energy performance evaluation of commercially available window glazing in Darwin’s tropical climate. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Kim, S.-H. Analysis of the performance of vacuum glazing in office buildings in Korea: Simulation and experimental studies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Hayat, N.; Farukh, F.; Imran, S.; Kamran, M.; Ali, H. Key design features of multi-vacuum glazing for windows: A review. Therm. Sci. 2017, 21, 2673–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, C.; Xia, X.-L. Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity and absorption coefficient identification of quartz window up to 1100 K. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 32, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, M.; Roy, S.; Roskilly, A.P.; Smallbone, A. The performance and efficiency of novel oxy-hydrogen-argon gas power cycles for zero emission power generation. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 244, 114510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nsaif, M.A.; Jali, J.M.; Baccar, M. Experimental investigation of the thermal performance of triple glazed windows integrated with PCM and low-e glass. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2024, 42, 1735–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, G.; Liu, J. A new validated TRNSYS module for phase change material-filled multi-glazed windows. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, R.; Lu, Y.; Arici, M.; Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Qi, Z.; Li, D. Parametric research on thermal and optical properties of solid-solid phase change material packaged in glazing windows. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, D.; Vorotović, G.; Bengin, A.; Petrović, P. Quadcopter altitude estimation using low-cost barometric, infrared, ultrasonic, and LIDAR sensors. FME Trans. 2021, 49, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, G.V.; Glubokov, N.A.; Yupashevsky, A.V.; Kazmina, A.S. Air flow sensor based on environmental sensor BME280. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference of Young Specialists on Micro/Nanotechnologies and Electron Devices (EDM), Erlagol, Russia, 29 June–3 July 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, C.; Loureiro, J.; Duarte, P.; Marques, J.; Figueira, J.; Ropio, I.; Ferreira, I. V2O5 thin films for flexible and high sensitivity transparent temperature sensor. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2016, 1, 1600077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornemann, S.; Lang, W. Considerations and limits of embedding sensor nodes for structural health monitoring into fiber metal laminates. Sensors 2022, 22, 4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Artificial neural network-based smart aerogel glazing in low-energy buildings: A state-of-the-art review. iScience 2021, 24, 103420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osorio-de-la-Rosa, E.; Valdez-Hernández, M.; Vázquez-Castillo, J.; Franco-de-la-Cruz, A.; Woo-García, R.; Castillo-Atoche, A.; La-Rosa, R. Plant microbial fuel cells as a bioenergy source used in precision beekeeping. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 60, 103499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO/IEC 17025; General Requirements for the Competence of Testing and Calibration Laboratories. ISO/IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xiong, J.; Mao, G.; Qi, Y. Computational fluid dynamics for cavity natural heat convection: Numerical analysis and optimization in greenhouse application. Adv. Math. Phys. 2023, 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, Y.; Confrey, T.; Callaghan, D.; Kent, N.; Nolan, C. CFD analysis of thermal and flow physics in buildings utilizing smart glazing for mitigation of solar gain. In Proceedings of the 5th Thermal and Fluids Engineering Conference (TFEC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–8 April 2020; Begell House: Danbury, CT, USA, 2020; pp. 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basok, B.; Novikov, V.; Pavlenko, A.; Davydenko, B.; Koshlak, H.; Goncharuk, S.; Lysenko, O. CFD simulation of heat transfer through a window frame. Rep. Struct. Eng. 2024, 26, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, K.; Cho, D.; Koo, B.; Yun, Y. Thermal performance analysis of windows, based on argon gas percentages between window glasses. Buildings 2023, 13, 2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimshin, V.; Khamrakulov, R.; Alikabulov, S.; Radjabov, Y.; Abdurakhmonov, A.; Mirazimova, G.; Jamolova, M. Study on the possibilities of increasing the effectiveness of thermal insulation of enclosing structures in window openings using low-emission coatings and films. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 563, 02024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taler, D.; Sobota, T.; Jaremkiewicz, M.; Taler, J. Influence of the thermometer inertia on the quality of temperature control in a hot liquid tank heated with electric energy. Energies 2020, 13, 4039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Małek, M.T.; Koczyk, H. Influence of temperature sensor (Pt100) accuracy on the interpretation of experimental results of measuring temperature on the surface. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2024, 34, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).