Abstract

The increasing inclusion of robots in social areas requires continuous improvement of behavioral strategies that robots must follow. Although behavioral strategies mainly focus on operational efficiency, other aspects should be considered to provide a reliable interaction in terms of sociability (e.g., methods for detection and interpretation of human behaviors, how and where human–robot interaction is performed, and participant evaluation of robot behavior). This scoping review aims to answer seven research questions related to robotic motion in socially aware navigation, considering some aspects such as: type of robots used, characteristics, and type of sensors used to detect human behavioral cues, type of environment, and situations. Articles were collected on the ACM Digital Library, Emerald Insight, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, MDPI, and SpringerLink databases. The PRISMA-ScR protocol was used to conduct the searches. Selected articles met the following inclusion criteria. They: (1) were published between January 2018 and August 2025, (2) were written in English, (3) were published in journals or conference proceedings, (4) focused on social robots, (5) addressed Socially Aware Navigation (SAN), and (6) involved the participation of volunteers in experiments. As a result, 22 studies were included; 77.27% of them employed mobile wheeled robots. Platforms using differential and omnidirectional drive systems were each used in 36.36% of the articles. 50% of the studies used a functional robot appearance, in contrast to bio-inspired appearances used in 31.80% of the cases. Among the frequency of sensors used to collect data from participants, vision-based technologies were the most used (with monocular cameras and 3D-vision systems each reported in 7 articles). Processing was mainly performed on board (50%) of the robot. A total of 59.1% of the studies were performed in real-world environments rather than simulations (36.36%), and a few studies were performed in hybrid environments (4.54%). Robot interactive behaviors were identified in different experiments: physical behaviors were present in all experiments. A few studies employed visual behaviors (2 times). In just over half of the studies (13 studies), participants were asked to provide post-experiment feedback.

1. Introduction

Presently, robot presence in human environments has increased and will continue to do so in the coming years. In this context, a key challenge for mobile robots is to model human presence and motion, which involves the implementation of safety factors, the personal intentions of people, and the rules established by society []. In fact, these rules and intentions can vary depending on the spatial and temporal context, e.g., by cultural heritage or generation. Robots must adapt or modify their motion following socially aware constraints to perform their tasks efficiently in human environments, just as humans do. The latter is crucial for a successful integration of robots in realistic scenarios, where navigation must be efficient and socially acceptable [].

Robots are commonly displayed in restricted areas (i.e., a cage) for industrial settings. In contrast, Human–Robot Interaction (HRI) is developed mainly in domestic and public environments [], where the social phenomena should be considered.

In HRI robots and humans coexist in shared spaces [], where respect should be a key factor, i.e., sociability. Sociability is reached when people’s comfort is achieved. Kruse T. et al. [] define sociability as “the adherence to explicit high-level cultural conventions” and comfort as “the absence of annoyance and stress for humans in interaction with robots”. Therefore, it is essential to carefully design robotic movement techniques that emulate conventions so that comfort increases in specific interactions.

Robotic motion techniques in HRI belong to the sub-field of Socially Aware Navigation (SAN). According to Rios-Martinez et al. [], SAN is defined as “the strategy exhibited by a social robot which identifies and follows social conventions (in terms of management of space) in order to preserve a comfortable interaction with humans. The resulting behavior is predictable, adaptable, and easily understood by humans”. In this regard, Rios-Martinez J. et al. define social conventions as “behaviors created and accepted by the society that help humans to understand intentions of others and facilitate the communication”.

Robots’ capabilities must emulate behaviors according to social conventions; for that purpose, robots require a certain level of communication and understanding of human intentions. In this regard, it is fundamental to characterize the signals or behavioral cues expressed by humans during social interactions. According to [], behavioral cues are defined as “a set of temporal changes in neuromuscular and physiological activity that last for short intervals of time”. Furthermore, they propose a classification of elementary social cues (e.g., physical appearance, gesture and posture, face and eye behavior).

Robotic navigation is interpreted as the ability to move from one point to another. Mobile robots navigate following their specific configurations, which involve characteristics such as the type of locomotion, the kinematic model, or the environment []. For instance, the recovery motion behavior commonly used to estimate robot position is different for a differential-drive robot, a non-holonomic robot, and vehicles with Ackermann steering. In each case, the motion technique must take into account the robot’s kinematics while designing the robot’s motion [].

It is important to note that implementing a robotic behavior is an interdisciplinary problem, since it involves modeling socially aware navigation and kinematics according to the robot, the environment, and the interaction with people.

Robots must operate under traditional constraints while prioritizing comfort and quality of interaction with people []. The characteristics of the robots used in these contexts transcend physical functionality. They represent an area of opportunity for improving software architectures, the perception system, and the operational frameworks designed for the decision-making process.

Several reviews have been published on robot motion addressing SAN [,,]. Specifically, Venture G. and Kulic. D. [] focused on the use of robotic expressive motions, examining how movement can communicate information while achieving a task. Additionally, they described how different motion primitives are achieved in anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic robots, and how expressivity has been evaluated. They highlighted that the role of robot motion expressivity could affect people’s behavior. Although the authors mentioned the evaluation process used to assess robot behavior in terms of expressivity, they did not explain the metrics used in the evaluation. Furthermore, the authors did not include the type of feedback used in the experiments.

Pascher M. et al. review robot motion intent [] and identify the intent types used to make robot actions more predictable and understandable. While Venture G. and Kulic. D. focused on expressive motions, the emphasis of Pascher M. et al. lies in the communication mechanisms that enable humans to infer what the robot is going to do. This approach encompasses the information expressed through signals rather than the motion primitives that the robot performs. Although understanding intent information is a key aspect in improving human–robot communication, the review lacks the description of the strategy parameters related to motion techniques.

Nocentini O. et al. [] propose a detailed description of the model underlying the robot’s behavior and the role of humans in the experiments. This review focuses on the description and classification of the mechanisms that allow emulation of social behaviors. However, it does not provide a detailed description of the metrics or evaluation instruments, nor does it discuss the use of sensor technologies. The review focuses on the behavior model and the variables involved, resulting in a disconnection between the robot’s behavior and the experimental trials evaluated.

1.1. Roadmap

The ultimate goal of this scoping review is to map the current landscape of human behavioral cues and robot motion techniques in socially aware navigation. To achieve this, we identify the key motion and interaction behaviors reported in the articles and analyze how they are processed. Our approach aims to cover the techniques and evaluation methods used in experiments with human participants, including the robot types, sensors, experimental environments, evaluation metrics, and the feedback from participants. The results of this work are limited by the selection of sources and the search process. However, the scoping review proposes preliminary insights about the state of the art to guide future research on socially aware navigation.

1.2. Contributions

The primary contribution of this scoping review is the application of the PRISMA-ScR to map the motion techniques in socially aware navigation. In contrast to previous works that may have isolated socially aware concepts (e.g., expressivity, behavior, intention), the review reports the entire experimental methodology. Starting from the robot type, through the environment where the experiments are conducted, the human behavioral cues and robot motion implemented, to the evaluation and feedback collection. Based on this, the main contributions of this scoping review are:

- 1.

- To identify the type of robot and sensor technology used in the studies (e.g., locomotion, drive system, type of sensor).

- 2.

- To present the behavioral cues processed in the studies (location of the processing, behavioral cues, biological signals).

- 3.

- To describe the type of environment and situation employed in the experiments (e.g., environment type, location, experimental scenario).

- 4.

- To describe the motion and interaction behaviors that drive the robot motion to assess socially aware navigation.

- 5.

- To describe the evaluation metrics used in the studies (e.g., quantitative and qualitative metrics, statistical analysis, safety considerations).

- 6.

- To report the participant feedback considered in the studies (e.g., sample size, gender, age, feedback).

2. Methods

This scoping review was conducted in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) proposed by Tricco A. et al. []. Additionally, the review follows the framework proposed by Arksey, H., and O’Malley, L. []. This framework involves five stages: (1) identification of research questions, (2) identification of relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. The following section describes the methodology through the first four stages.

2.1. Identification of Research Questions

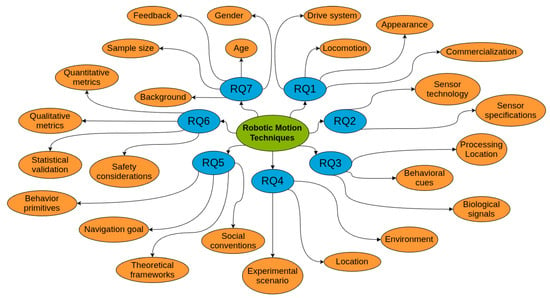

According to [,,], there are key elements involved in the interaction of humans with robots. Based on this, the following research questions (RQ) were stated:

- RQ1.

- What type of robot is used in the studies?: As addressed by Lawrence et al. [], it is important to select appropriate robot platforms to study social norms in HRI. Therefore, the type of robot involves aspects describing the robot platform employed in order to address SAN.

- RQ2.

- What sensors are used to collect data from behavioral cues to enable robot motion in socially aware navigation?: The identification of sensors used during interaction is relevant because it enables the identification of potential emerging technologies, as well as opportunity areas.

- RQ3.

- How are behavioral cues processed to enable robot motion in socially aware navigation?: The processed behavioral cue is connected to the sensors used, but the focus is on the interpretation of the behavioral cue rather than the hardware. The processing or interpretation of these clues or signals has been included through research questions in previous reviews [,,].

- RQ4.

- To what type of environment and situation is the robot exposed in the experiments conducted to assess robot motion in socially aware navigation?: It is necessary to identify the environment because it enables us to contrast how robot behavior generalizes across environments and the differences between simulation and the real world [].

- RQ5.

- What motion and interaction behaviors drive the robot’s motion to assess socially aware navigation?: The robot motion is a key aspect to study the effect of different navigation policies [], as well as what kind of social norms have been incorporated into the robot’s behavior [], and what types of behaviors a robot should exhibit to ensure social norm compliance [].

- RQ6.

- Which evaluation metrics were used to assess the robot’s social performance?: As stated before by Francis et al. [], it is fundamental to identify the methods, metrics, and safety factors in order to obtain insights about the effects of different robot motion techniques.

- RQ7.

- Were participants involved in the experiments?: As a result of conducting experiments with volunteers, a new dimension emerges that goes beyond the evaluation of the experiments and focuses on reporting sample characteristics and post-experiment feedback.

2.2. Identification of Relevant Studies

Articles were collected in six databases: ACM Digital Library, Emerald Insight, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, MDPI, and SpringerLink. The records had to contain the keyword “behavior” in the title and include the keywords “robot”, and “interaction” in the document. These keywords were selected based on the fundamental terminology in the reviews presented in Table 1. In this regard, several keywords could be additionally associated with the behavior and motion of robots. Based on [,,] “human”, “aware”, and “navigation” were included as search keywords. Nevertheless, studies using related terms such as “human-computer”, “social awareness” or “social behavior” may have been excluded. The Boolean operator “AND” was used to combine the keywords. Thus, the final search query was: [Title: behavior] AND [All: robot] AND [All: interaction] AND [All: human] AND [All: aware] AND [All: navigation].

Table 1.

Search strategies identified in previous works. The asterisk (*) indicates that the search includes all variations of the keyword suffix.

The searches were conducted in January 2025. Moreover, an update on the search for articles was performed in August 2025. The query was applied uniformly across all information sources. In addition, a filter was included in the search tools to delimit the date range and type of publication (peer-reviewed articles or conference proceedings) according to the inclusion criteria as described below.

2.3. Study Selection

Articles were excluded if they: (1) were handbooks, reviews, or editorial notes, and (2) focused on autonomous underwater vehicles (AUV). Records were included if they: (1) were published between January 2018 and August 2025, (2) were written in English, (3) were published in journals or conference proceedings, (4) focused on socially aware robots, (5) addressed SAN, and (6) conducted experiments with human participants. In addition, records were excluded if, based on title and abstract, they did not fit into the SAN and HRI scopes. The search was restricted to articles published between 2018 and 2025 to include and review the most recent developments in motion techniques in socially aware navigation, considering the fast evolution of the field and its technological applications. The criterion to exclude AUVs is included to narrow the scope to aerial and ground-based navigation, because social robots are more frequent in these environments. In these contexts, there is an increasing use of experimental protocols for human–robot interaction. These types of studies entail different methodological challenges. To address these aspects, we only include articles that conduct experiments with human participants.

2.4. Charting the Data

- RQ1.

- What type of robot is used in the studies?Despite the existence of common robotic features in SAN, there are several platforms and systems. The configuration of these platforms determines the locomotion mechanism and drive system. These aspects are key to analyzing the robot motion because they condition the navigation strategy employed and introduce limitations. In this regard, the theoretical framework to describe the locomotion and drive system used is based on the frameworks proposed by Jahanian O. and Karimi G. [], and Francisco R. et al. []. Additional aspects to describe the type of robot in the context of SAN are the appearance and commercialization. The definition and classification of the appearance will follow the proposal of Baraka K. et al. []. Thereby, RQ1 analyzes the following parameters:

- 1.

- Locomotion: According to Jahanian O. and Karimi G. [], locomotion is defined as “the capability for a living being or an inanimate object to move from one place to another”. For this scoping review, wheeled mobile robots [] and rotary-wing drones will be used as locomotion types.

- 2.

- Drive system: Drive configuration and restraints related to the maneuverability, controllability, and stability of the robot (e.g., differential, omnidirectional, bipedal) as presented by Francisco R. et al. [].

- 3.

- Appearance: According to Baraka K. et al. [], appearance is defined as the “physical presence of robots in a shared time and space with humans” and is classified as bio-inspired, artifact-shaped, or functional.

- 4.

- Commercialization: it refers to a commercial robot that is available for purchase.

- RQ2.

- What sensors are used to collect data from behavioral cues to enable robot motion in socially aware navigation?Sensors are classified according to criteria such as level of processing complexity, passive-active, and proprioceptive-exteroceptive []. On the other hand, there are taxonomies that group sensors with similar functionalities. For instance, a taxonomy of visual systems is proposed by Martinez-Gomez J. et al. []. In this approach, in order to identify the sensors employed, we define the following parameters:

- 1.

- Sensor technology: Sensors used to collect data from behavioral cues and grouped by the level of processing complexity (e.g., force-sensitive sensors, joysticks, monocular cameras).

- 2.

- Sensor specifications: Details of the features associated with the sensors (e.g., latency, range, resolution).

- RQ3.

- How are behavioral cues processed to enable robot motion in socially aware navigation?After describing the sensor technologies used to collect data from behavioral cues, it is necessary to identify the data processing that enables robot motion. Frameworks address this process of quantifying the behavioral cues through several approaches. For instance, they use psychophysiology measurements [], social cues [], and physical interactions [,]. In this regard, Q3 examines how behavioral cues are processed through the following parameters:

- 1.

- Location of the processing unit: The location of data processing, whether it is outside the robot, inside the robot, or with hybrid management.

- 2.

- Behavioral cues: According to Vinciarelli et al. [], behavioral cues “describe a set of temporal changes in neuromuscular and physiological activity that last for short intervals of time”. In this regard, they grouped the cues into several classes. For this scoping review, physical appearance, gesture and posture, face and eye behavior, vocal behavior, and space and environment will be used as behavior cue classes.

- 3.

- Biological signals: Information related to the monitoring of participants’ biological signals.

- RQ4.

- To what type of environment and situation is the robot exposed in the experiments conducted to assess robot motion in socially aware navigation?It is necessary to analyze the contexts in which the experiments were conducted in order to replicate the results and understand how the environments influenced the results. Consequently, the experimental environment is described using three parameters: (i) the environment type, which can be real, simulated, or hybrid environment where the experiments are conducted; (ii) the experiment location [], and (iii) the experimental scenario to understand the properties of the interaction [].

- 1.

- Environment type: Classifies the nature of the environment of the human–robot interaction as real, simulated, or hybrid.

- 2.

- Location: According to [], location “characterizes with more detail where the task takes place (setting) and may define some of the requirements for the robot and the task” (e.g., a kitchen, an elevator, a shopping mall).

- 3.

- Experimental scenario: Describes the activity or instructions followed by the robot and participants during the interaction.

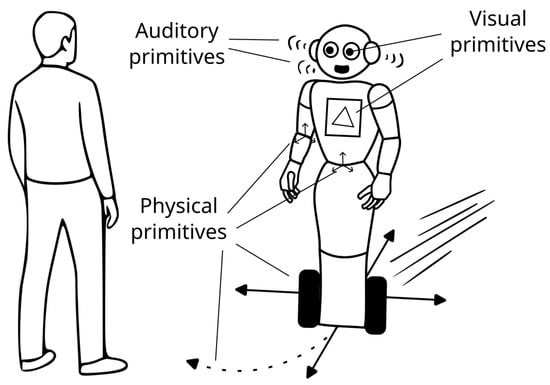

- RQ5.

- What motion and interaction behaviors are used to assess socially aware navigation?The concept of behavior primitives can be used as a descriptor of the elemental or low-level actions that a robot can perform: this concept has been explored as expression intent behavior [] or primitive []. The navigation goal seeks to provide a clear description of the target condition or requirements to finish the interaction []. In order to analyze the social dimension of the robot’s motion, it is crucial to identify: (i) the social conventions used by the robot, and (ii) a description of the theoretical framework that explains how the robot’s motion and behavior are modeled []. These parameters are defined as follows:

- 1.

- Behavior primitives: Description of the low-level actions or behaviors that a robot can perform, and is divided into physical, auditory, and visual primitives.

- 2.

- Navigation goal: Physical motion or sequence of behavior primitives that the robot must perform to fulfill the experimental scenario.

- 3.

- Social conventions: According to [], social conventions are defined as “behaviors created and accepted by the society that help humans to understand intentions of others and facilitate the communication” (e.g., personal space management, legible navigation, understandable navigation).

- 4.

- Theoretical framework: Core theory (or theories) that govern the overall robot behavior.

- RQ6.

- Which evaluation metrics were used to assess the robot’s social performance?The evaluation of the experiments may involve the robot’s performance, instruments measuring participants’ perceptions [], and metrics or mechanisms designed to guarantee the participant’s safety []. Metrics can be quantitative [] or qualitative []. Additionally, statistical tests are an essential methodological instrument to evaluate the results [,]. Based on this, the following parameters are proposed:

- 1.

- Quantitative metrics: Metrics that evaluate objective aspects and their measurements are repeatable and verifiable.

- 2.

- Qualitative metrics: Metrics that evaluate subjective aspects and their measurements are based on observations and human perception.

- 3.

- Statistical validation: Process of applying a set of statistical tests to verify the reliability of data and validate the analytical method.

- 4.

- Safety considerations: mechanisms or considerations related to the safety of participants while interacting with the robot.

- RQ7.

- Were participants involved in the experiments?According to [,], a key aspect to assess the robot performance in HRI is the feedback of volunteers who participated in the experiments. Based on this, the following data were extracted for each article:

- 1.

- Sample: Number of volunteers who participated in the experiments.

- 2.

- Gender: The gender of volunteers.

- 3.

- Age: The ages of the participants.

- 4.

- Participant’s background: Information provided by the authors on participant’s features (e.g., educational level, medical condition, nationality).

- 5.

- Participant’s feedback. This involves participants’ opinions on the robot’s performance collected via questionnaires and interviews.

Figure 1 presents each research question with its corresponding parameters extracted from the articles.

Figure 1.

Visual map of the parameters of each research question. Nodes of blue color indicate a research question, nodes of an orange color indicate the corresponding parameters.

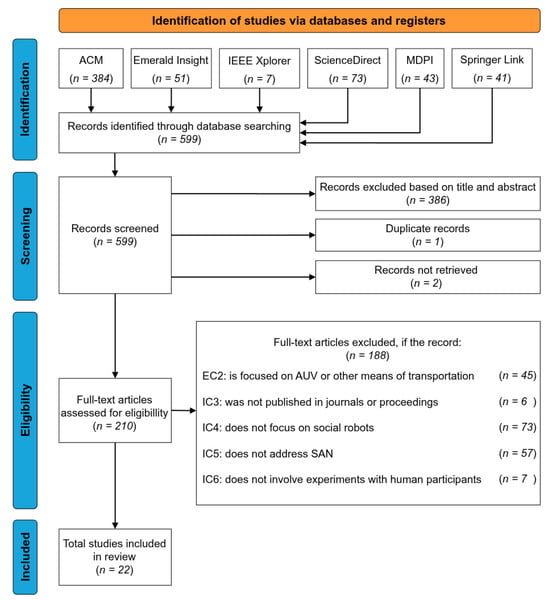

3. Results

Initially, 599 articles were retrieved from the databases. After analyzing the title and abstract, 386 articles were eliminated. Two articles were not available, and one article was duplicated. As a result, 210 articles were analyzed to determine whether they met the inclusion criteria. Articles were excluded because: (i) they were focused on autonomous underwater vehicles (); (ii) they were not published in journals or conference proceedings (); (iii) they did not focus on social robots (); (iv) they did not address socially aware navigation (), and (v) they did not conduct experiments with human participants (). Specifically, we used the SAN definition as a part of the criterion to dismiss experiments that did not consider a behavioral strategy in terms of space management [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]. Only 22 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in this review for further analysis (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the PRISMA-ScR protocol, where EC = exclusion criteria and IC = inclusion criteria.

3.1. RQ1 What Type of Robot Is Used in the Studies?

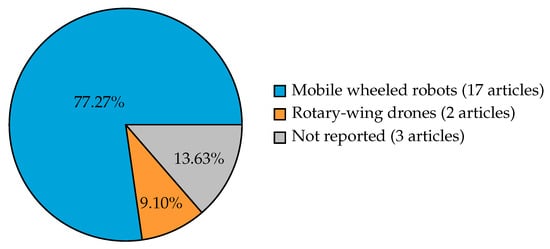

3.1.1. Locomotion

Based on the robot locomotion, the robots employed in the articles could be classified as mobile wheeled robots. Most articles (77.27%) employed mobile wheeled robots (17/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]), while a few articles (9.10%) employed rotary-wing drones (2/22: [,]). Nevertheless, based on the information provided by the articles, we were unable to identify the locomotion mechanism used in 13.63% of the articles (3/22: [,,]). Figure 3 summarizes the robot locomotion mechanisms used in the articles.

Figure 3.

Distribution of locomotion mechanisms ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

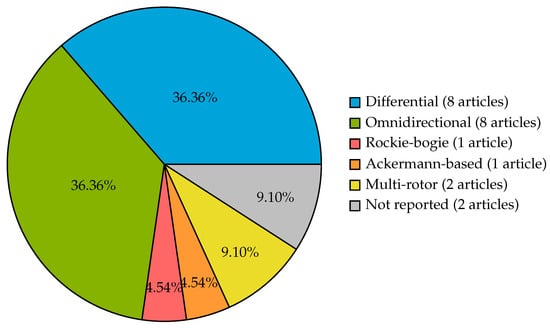

3.1.2. Drive System

Regarding the driving systems of mobile wheeled robots, we found the presence of differential systems in 36.36% (8/22: [,,,,,,,]), and omnidirectional in 36.36% (8/22: [,,,,,,,]) of the articles. Additionally, a rocker-bogie and an Ackermannn-based system was identified in 4.54% (1/22: []) and 4.54% (1/22: []) of the articles respectively. Regarding the rotary-wing drones, we found the use of multi-rotor systems in 9.10% of the articles (2/22: [,]). Nevertheless, we were unable to identify the drive system used in 9.10% of the articles (2/22: [,]). Figure 4 summarizes the robot drive systems used in the articles.

Figure 4.

Distribution of robot drive systems ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

3.1.3. Robot Appearance

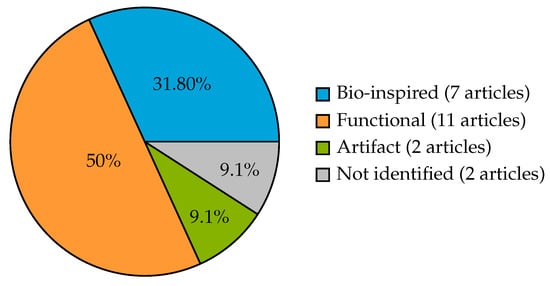

In the context of the robot appearance, three types of robots were used in the articles: bio-inspired in 31.80% (7/22: [,,,,,,]), functional in 50% (11/22: [,,,,,,,,,,]), artifact in 9.10% (2/22: [,]) of the articles. Bio-inspired articles used Pepper [,,,], Viva [], Robovie [], and Kuri [] robots. Focusing on functional robots, articles employed: Mirob [,], Jetbot [], Beam Pro [,], Jackal [], Parrot [], and Frog []. Additionally, three robots [,,] were identified as functional based only on their appearance. Frog and Parrot were classified as functional because, despite their names, they do not resemble animals, and the name is only a conceptual inspiration. Robot appearance was not identified in 9.10% of the articles (2/22: [,]). Figure 5 summarizes the robot appearance designs identified in the articles.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the robot appearance designs identified ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

3.1.4. Commercial Robots

The commercial robots included Pepper [,,,], Beam Pro [,], Parrot [], and Kuri [] robots, while another third of the articles employed non-commercial robots such as Mirob [,], Robovie [], Jetbot [], and Frog [].

The remaining articles were not classified as using commercial or non-commercial robots, as they employed simulated robots [,], treated robots as point particles [,], or did not specify the robot model used [,,,,]. Table 2 summarizes the parameters analyzed in RQ1.

Table 2.

Summary of robot types identified, where Not reported = NR, ✓ = Yes, and ✗ = No.

In summary, the results for RQ1 suggest a higher frequency of mobile wheeled robots (77.27%). Functional robot appearances (50%) are the most employed, although bio-inspired appearances (31.80%) constitute a considerable portion of the articles.

3.2. RQ2 What Sensors Are Used to Collect Data from Behavioral Cues to Enable Robot Motion in Socially Aware Navigation?

3.2.1. Sensor Technology

More than two thirds (72.73%) of the articles (16/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]) reported the sensor technology used to detect the behavioral cues. Only 27.27% of the articles (6/22: [,,,,,]) did not provide this information.

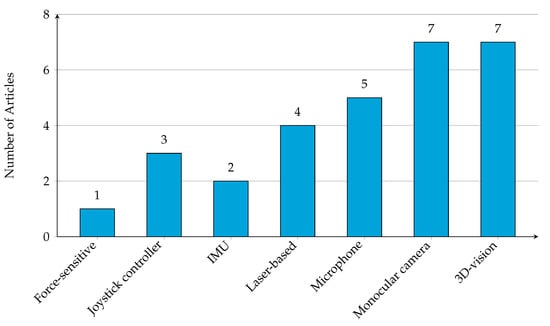

The sensor technologies found were arranged based on the level of processing complexity. At the lowest level of processing we found force-sensitive resistors (1 article: []), microphones (5 articles: [,,,,]), Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) sensors (2 articles: [,]), joystick controllers (3 articles: [,,]), and laser-based sensors (4 articles: [,,,]). At the highest level of processing complexity, we found monocular cameras (7 articles: [,,,,,,]), and 3D-vision sensors, i.e., technologies with depth processing capabilities, specifically RGBD cameras and stereo vision (4 articles: [,,,]) and motion capture systems (3 articles: [,,]). With regard to sensor technologies, it should be noted that in some cases, the controls and motion capture systems described come from a Virtual Reality (VR) headset [,]. Figure 6 summarizes the sensor technologies reported in the articles.

Figure 6.

Frequency of sensor technologies used ( articles). The horizontal axis represents the sensors ordered according to their processing complexity [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

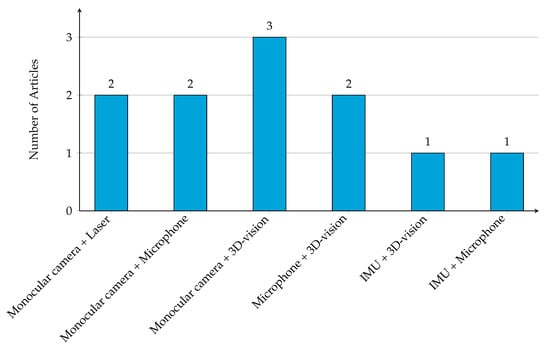

Focusing on the articles reporting the sensor technology used, there were studies employing only one type of sensor (i.e., monosensor: [,,,]), and other studies used various types of sensors (i.e., multisensor: [,,,,,,,,,,,]). According to frequency of use, the most frequent combinations were monocular cameras with laser-based sensors (2 articles: [,]), microphones (2 articles: [,]), and 3D-vision technologies (3 articles: [,,]). Moreover, other combinations involved 3D-vision with an IMU (1 article: []), and microphones (2 articles: [,]). The least combination used in the articles was an IMU and a microphone (1 article: []). Few studies (1 article: []) reported the integration of multiple sources, i.e., sensor fusion []. Figure 7 summarizes the combination of sensors used in the articles.

Figure 7.

Frequency of sensor technologies combined ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,].

3.2.2. Sensor Specifications

Regarding sensor specifications, a few articles have reported the features of the sensors used to collect data from behavioral cues. Specifically, Prakash and Varun G. [] reported a 360-degree field of view and a camera frame rate of 15 frames per second (fps). In terms of frequency rates, ref. [] reported an information extraction rate of 2 Hz, while [] mentioned an action command execution rate of 10 Hz. Additionally, ref. [] employed a high-frequency acquisition of 180 Hz, with a motion accuracy of 1 mm. Focusing on latency, Angelopoulos et al. [] provided information on time delays, reporting human detection latencies between and s, and contextual information latencies between and s.

Despite these insights, most articles (77.27%, 17/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]) did not provide information on how the data were collected using sensors. Almost a third of the articles (22.73%, 5/22: [,,,,]) provided this information.

The results for RQ2 indicate that vision-based technologies (monocular and 3D-vision) are most frequent. While most studies (72.73%) report the sensor technology used, 77.27% of the articles reviewed omit reporting on sensor specifications.

3.3. RQ3 How Are Behavioral Cues Processed to Enable Robot Motion in Socially Aware Navigation?

3.3.1. Location of the Processing Unit

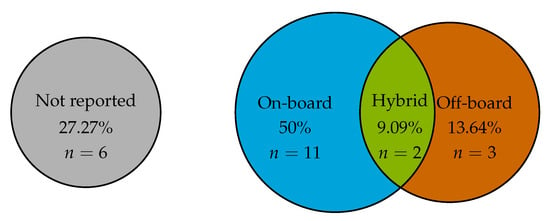

Regarding the locations of the processing unit, 50% of the articles reported the sensor information processed on board the robot (11/22: [,,,,,,,,,,]). Few studies (13.64% of the articles) provided the processing location off-board (3/22: [,,]), while only a 9.09% reported a hybrid management approach (2/22: [,]). The location of the processing unit was not reported in the 27.27% remaining articles (6/22: [,,,,,]). Figure 8 summarizes the location of the processing unit identified in the articles.

Figure 8.

Location of the processing unit to enable robot motion ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

3.3.2. Behavioral Cues

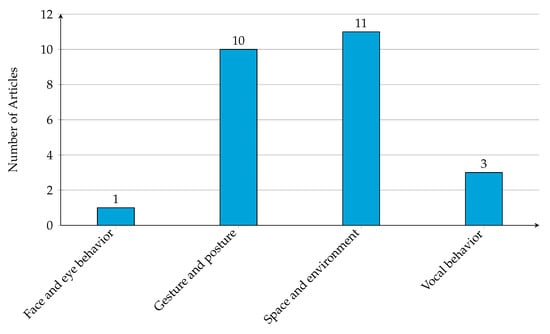

Based on the behavioral cue classification, the space and environment class were more frequent (11 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,]) behavioral cue. These behavioral cues include the measurement of the volunteer’s position [,,,,,,], as well as interpersonal distance [,,], occupied area [], individual danger zones [], and markers []. Gesture and posture cues were the second most used class (10 articles: [,,,,,,,,,]) in the articles. The gesture and posture include the participant orientation [], skeleton joints [,], deictic gestures [], action recognition [], clinking behavior [,,,], and walking speed [,,]. The least used class was vocal behavioral cues (3 articles: [,,]), which only include speech recognition. As well as face and eye behavior (1 article: []), specifically gaze detection. Figure 9 summarizes the type of behavioral cues identified in the articles. Almost a quarter of the studies (5 articles: [,,,,]) did not report the behavioral cues processed.

Figure 9.

Frequency of types of behavioral cues employed ( articles). A total of 4 behavioral cues were extracted across the 17 articles reporting them [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

3.3.3. Biological Signals

None of the studies reported the use of biological signals to enable human perception.

Regarding RQ3, half of the articles (50%) reviewed utilize on-board processing. The processed cues are mostly spatial (11 articles) or gestural (10 articles) cues. In addition, there is a complete absence of a biological signal to enable human perception.

3.4. RQ4 To What Type of Environment and Situation Is the Robot Exposed in the Experiments Conducted to Assess Robot Motion in Socially Aware Navigation?

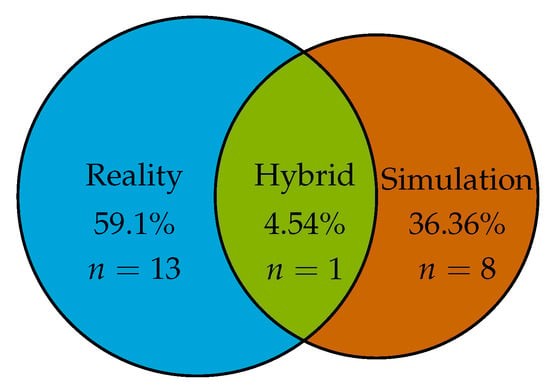

3.4.1. Environment Type

Over a half of the experiments (59.1%) were conducted in real-world environments (13/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,]), followed by 36.36% in simulations (8/22: [,,,,,,,]). Just 4.54% of the articles include a hybrid approach (1/22: []). Figure 10 summarizes the environment type identified in the articles.

Figure 10.

Environment types used in the experiments () [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

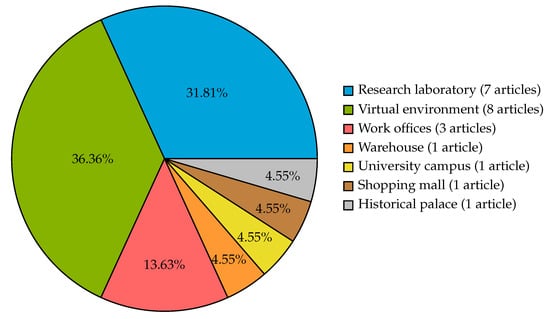

3.4.2. Location

The real-world environments include multiple locations. 31.81% of the articles were research laboratories (7/22: [,,,,,,]) and 36.36% virtual environments (8/22: [,,,,,,,]). The remaining articles include: 13.63% in work offices (3/22: [,,]), 4.55% in shopping malls (1/22: []), 4.55% in university campus (1/22: []), 4.55% in warehouses (1/22: []), and 4.55% in a historical palace (1/22: []). Figure 11 summarizes the locations identified in the articles.

Figure 11.

Distribution of the locations identified in the experiments ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

3.4.3. Experimental Scenario

The experimental scenarios identified cover a diverse range of activities. In this regard, a few scenarios simulate areas of domestic activities [,,], and conversational group settings [,]. Other experimental scenarios simulate typical daily activities. Specifically, moderately crowded scenes [,], a hallway [], a corridor [], crossing scenarios [,], an empty room ([]), and plain areas without obstacles []. In contrast with environmental types and locations, the remaining experimental scenario simulates unique activities. Specifically, a dance floor [], a solitary drinking experience at home [], a hat store with narrow aisles [], an office building with an elevator [], an exposition in the Royal Alcázar Palace [], a hallway setting at a university [], an obstacle course [] (a step, a soft plastic bag, and a plastic bottle), a medical package delivering [], a mail delivering []. Table 3 summarizes the parameters analyzed in RQ4.

Table 3.

Summary of types of environment and situations identified in the articles.

The results for RQ4 suggest that real-world experiments (59.1%) are more frequent than simulations (36.36%). Moreover, they are often conducted in controlled research laboratories (31.81%). The experimental scenarios, in contrast, include different approaches with few common baselines.

3.5. RQ5 What Motion and Interaction Behaviors Drive the Robot’s Motion to Assess Socially Aware Navigation?

3.5.1. Behavior Primitives

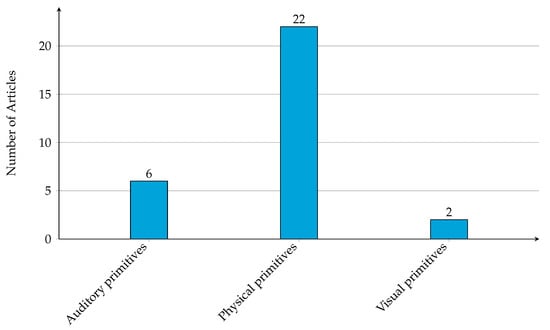

Several robot behavior primitives were identified to modify the robot’s motion. The primitives are grouped into physical, auditory, and visual. Figure 12 illustrates different behavior primitives associated with each group.

Figure 12.

Illustration of different behavior primitives in a one-to-one interaction.

In terms of frequency of use, all studies employed physical primitives (22 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]). This covers the robot’s capacity to change its joint movements [,], body gestures [,,], and trajectory-based motions [,,,]. As well as locomotion and drive-associated behaviors, specifically changing the position [,,,,,,], direction [,,,], orientation [,,,], velocity [,,,], and acceleration []. Continuing with physical primitives, other actions include turning, moving laterally, moving backward, and stopping [,,], mutual distancing [,], and vibrations or levers []. Just over a third of the articles included auditory primitives (6 articles: [,,,,,]). This covers speech phrases or voice commands [,,,,], and alert sounds []. Finally, a few articles included visual primitives (2 articles: [,]). This cover front-screen displays [], eye animations and pointers [], and LED light signaling []. Figure 13 summarizes the behavior primitives identified.

Figure 13.

Frequency of the behavior primitives identified ( articles). A total of 3 behavior primitives were extracted across the 22 articles reporting them [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

3.5.2. Navigation Goal

Despite the common environments and locations, the navigation goals remain unique among the articles analyzed. Navigation goals include the adjustment of the robot’s proximity to humans [] or robots passing between two people talking in a hallway []. In this sense, other navigation goals encompass robots: joining conversation groups [,] and initiating interactions while approaching humans in close encounters [,]. In crowded environments, navigation goals address the navigation through crowds [,], robots avoiding danger zones [], and finding preferred trajectories []. Goals oriented to expressiveness aspects include robots: expressing legible navigation through non-verbal cues [], yielding to people while passing through narrow halls [] or public spaces [], and adjusting the movement based on participants’ verbal communication []. Specific task oriented navigation goals include robots: following participants to maintain joint navigation [], serving as guides for museum or gallery visitors [], moderating participants’ alcohol consumption [], applying dance improvisation concepts [], and positioning themselves according to social norms when sharing elevators [] or delivering packages [,]. Finally, cross-cultural navigation goals were included, with robots that must adjust their proximity distances according to the cultural context [].

3.5.3. Social Conventions

The most frequently observed social conventions are personal space management [,,], and group joining behavior [,]. Moreover, another group of articles focuses on navigation-related conventions, such as legible navigation [,], understandable navigation [], joint navigation [], navigation in crowded environments [,], and telepresence navigation []. In contrast, some articles focus on unique social conventions, such as dance improvisation [], delivery service [,,], natural language [], tour guiding [], alcohol consumption moderation [], multimodal social interaction [], and human safety [].

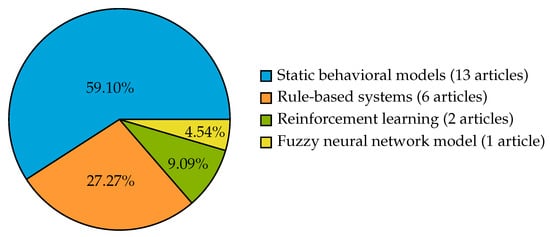

3.5.4. Theoretical Framework

The robot’s architecture determines how and when the robot’s motion is activated. Each architecture uses a different model or theoretical framework. In particular, 59.10% of the articles used static behavioral models (13/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,]). 27.27% used rule-based systems (6/22: [,,,,,]). Finally, the remaining articles use reinforcement learning (9.09%, 2/22: [,]), and fuzzy neural network (4.54%, 1/22: []). Figure 14 summarizes the theoretical frameworks identified in the articles.

Figure 14.

Distribution of the theoretical frameworks used to guide the robot’s motion in the experiments ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

In summary, all the studies include physical primitives (22 articles) to enable SAN. While we found several social conventions, static behavior models (59.10%) constitute the most common theoretical framework used for their implementation.

3.6. RQ6 Which Evaluation Metrics Were Used to Assess the Robot’s Social Performance?

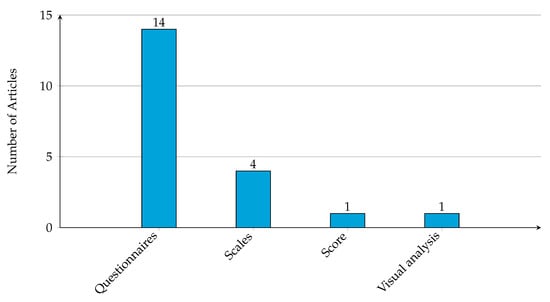

3.6.1. Qualitative Metrics

Questionnaires are the most frequently used qualitative metric (14 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,]). This includes custom questionnaires [,,,,,,,,,], the Robotic Social Attributes Scale (RoSAS) questionnaire [,,], and the Godspeed questionnaire []. Scale-based metrics (4 articles: [,,,]), included the source credibility scale [], system usability scale [], automation trust scale [], and the self-construal scale []. Finally, a few studies used feedback score (1 article: [])or visual analysis (1 article: []). Figure 15 summarizes the frequency of each type of qualitative metrics identified in the articles.

Figure 15.

Frequency of the qualitative metrics grouped by type of metric. ( articles). A total of 4 types of metrics were extracted across the 17 articles reporting them [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

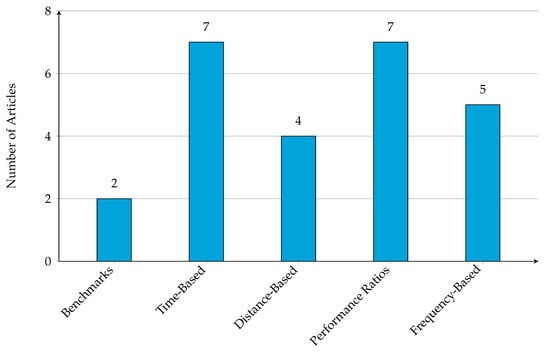

3.6.2. Quantitative Metrics

Due to the high diversity of quantitative metrics, we grouped them by measurement type, frequency, ratios, distance, duration, and benchmarks. Figure 16 summarizes the frequency of each group of quantitative metrics identified in the articles. The frequency-based metrics (5 articles: [,,,,]) include the number of interactions and danger frequency [], the number of speech-to-intent errors and interactions [], the number of collisions [,], and the number of times participants showed persuasiveness or social adherence []. The performance ratio-based (7 articles: [,,,,,,]) includes the collision and interaction index [], error rate of the speech-to-intent [], timeout rate [], success rate [,,], collision rate [,], robot’s ratio of passing through [], path efficiency and irregularity [], topological complexity [], average energy [], and average acceleration [].

Figure 16.

Frequency of the quantitative metrics grouped by type of metric. ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,].

The distance-based metrics (4 articles: [,,,]) represent spatial measurements related to the robot’s proximity to people or objects. Including distance to goal [], minimum distance [], path length [], and distances to primary and secondary agents []. The time-based metrics (7 articles: [,,,,,,]) include total path duration [], time per unit path length [], task completion time [], crossing onset time [], time to minimum uncertainty [], and general time to reach the goal []. Finally, the composite benchmarks (2 articles: [,]) include the Jackrabbot benchmark [] and the ORCA benchmark [].

3.6.3. Statistical Analysis

Based on the statistical analysis, the most frequently used tests were ANOVA approaches (9/22: [,,,,,,,,]). Different approaches include Mann–Whitney U tests (2/22: [,]), Fisher’s exact test (1/22: []), and Wilcoxon tests (3/22: [,,]) used to compare distributions without parametric assumptions. Chi-square tests were also included to analyze categorical data and test independence (3/22: [,,]). Table 4 summarizes the statistical analysis identified.

Table 4.

Statistical tests, test type, and their purposes in HRI articles, where P = parametric, NP = non-parametric, B = both, and NR = not reported.

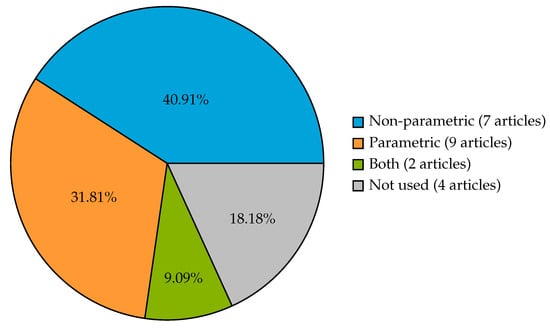

Almost a half of the articles (40.91%) used parametric statistical tests (9/22: [,,,,,,,,]) and 31.81% used non-parametric tests (7/22: [,,,,,,]). 9.09% of the articles employed both approaches (2/22: [,]), and the remaining 18.18% articles did not include a statistical test (4/22: [,,,]). Figure 17 summarizes the type of test used in the articles.

Figure 17.

Distribution of the statistical test types used to evaluate the experiments ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

In some cases, an additional statistical analysis about assumptions, reliability, and effect size was performed. In this regard, Bonferroni corrections were considered [,,,], as well as Jarque-Bera tests for normality verification []. Internal consistency was addressed using Cronbach’s alpha [,,,]. Cohen’s kappa [] and Fleiss’ kappa [] were used to measure inter-rater reliability. Welch’s t-test was used when the assumption of homogeneity of variances was violated [,].

Power analysis was included to check the validity of the sample size [,]. Effect size measures include Cohen’s d [,], rank-biserial correlation, and common language effect size [], and Spearman’s correlation []. Table 5 summarizes the additional statistical analysis.

Table 5.

Assumptions, reliability and power, and effect sizes reported to evaluate experiments, where NR = not reported.

3.6.4. Safety Considerations

Safety-related considerations were identified in eight studies. These included perceived safety abstractions such as risk perception [], risk zones [], and safety perception [], as well as functional safety measures such as emergency stop [,], maximum speed thresholds [,], and safety distance [].

Regarding RQ6, we found a high use of qualitative questionnaires (14 articles). In comparison, quantitative metrics show a high frequency of performance ratios (7 articles) and time-based metrics (7 articles). Regarding statistical approaches, we found non-parametric (40.91%) and parametric (31.81%) tests. Safety considerations or mechanisms were only reported in 8 of the 22 studies.

3.7. RQ7 Were Participants Involved in the Experiments?

3.7.1. Sample

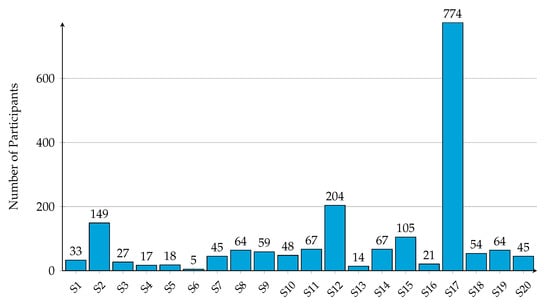

Studies reporting sample sizes ranged notably among the studies. Minimum sample size includes 5 participants [], and maximum sample size is 774 volunteers []. Only four studies exceeded 100 participants [,,,]. Furthermore, the remaining studies reporting a sample size range from 1 to 67 volunteers [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]. A few studies [,] did not report the sample size employed. Figure 18 summarizes the sample size used in the studies.

Figure 18.

Frequency of sample sizes used in the experiments ( articles). The x-axis labels correspond to the following studies: S1 [], S2 [], S3 [], S4 [], S5 [], S6 [], S7 [], S8 [], S9 [], S10 [], S11 [], S12 [], S13 [], S14 [], S15 [], S16 [], S17 [], S18 [], S19 [], S20 [].

3.7.2. Gender

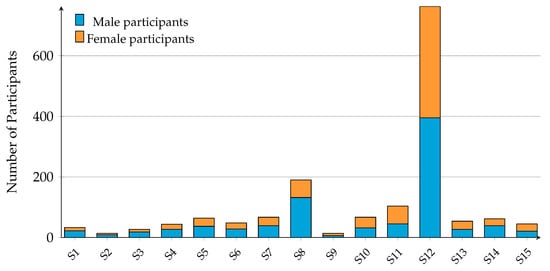

Regarding gender distribution, fewer articles were identified reporting gender than those reporting sample size. Only 15 articles indicate the gender distribution [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,], while the remaining articles did not provide gender information (7 articles: [,,,,,,]). Overall, male participants are more frequent in experiments (11 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,]). The presence of a non-binary participant (2 articles: [,]), and anonymous volunteers (2 articles: [,]) was also considered. Figure 19 summarizes the gender distribution used in the articles.

Figure 19.

Frequency of gender participation in the experiments ( articles). The x-axis labels correspond to the following studies: S1 [], S2 [], S3 [], S4 [], S5 [], S6 [], S7 [], S8 [], S9 [], S10 [], S11 [], S12 [], S13 [], S14 [], S15 [].

3.7.3. Age

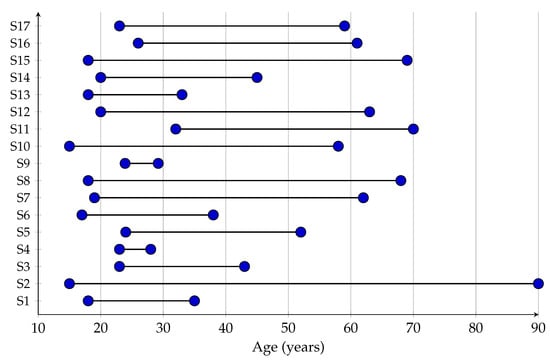

The age of participants varied across the reviewed articles. Most of the studies reported the participant age (17 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]), while the remaining articles did not provide related information (5 articles: [,,,,]). Overall, participants’ age ranges from 15 to 90 years. Young adults aged between 18 and 38 years are more frequent in experiments (9 articles: [,,,,,,,,]). Figure 20 summarizes the age ranges used in the articles without focusing on age distribution.

Figure 20.

Frequency of age ranges of the participants ( articles). The y-axis labels correspond to the following studies: S1 [], S2 [], S3 [], S4 [], S5 [], S6 [], S7 [], S8 [], S9 [], S10 [], S11 [], S12 [], S13 [], S14 [], S15 [], S16 [], S17 [].

3.7.4. Participant’s Background

Participant background varied considerably across the articles. Student populations were more frequent across the experiments (7 articles: [,,,,,,]), including university community members, students of different grades, and South Asian and Korean participants. A completely blind [] and multi-national [] participant sample were also included. Few articles addressed uncontrolled scenarios with participants without specific instructions. This included actual customers in a store (1 article: []), Daimler Truck employers (1 article: []), Amazon mechanical turk employers (1 article: []), and professional dancers (1 study: []).

3.7.5. Participant’s Feedback

The interview, reported in [,,,,,,], is used to understand the robot’s behavior and collect suggestions. While open-ended comments were used in [,,,] to describe their prior experience without limitations. The qualitative comments were collected to identify areas of improvement and cultural implications []. Furthermore, structured questionnaires were employed to evaluate the overall experience []. However, in the remaining studies [,,,,,,,], no information was provided regarding the participant feedback. A description of the feedback collected is summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Participant feedback reported at the end of the experiments.

The results for RQ7 suggest notable differences in sample sizes (from 5 to 774 participants) and a major participation of young adults (18–38) and student populations. Participant feedback was collected in 13 studies, often through interviews or open-ended comments.

3.8. Additional Results

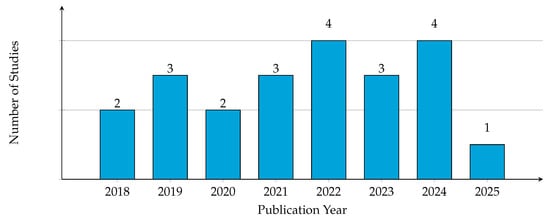

Focusing on the frequency of the articles published per year, Figure 21 shows that the number of studies published on robotic motion in SAN in journals and proceedings remains steady from 2022 to 2024 (at least three studies published in each year). Conversely, there was a drop in the number of studies published in 2018 and 2020.

Figure 21.

Frequency of articles on robotic motion in SAN published from 2018 to 2025 ( articles) [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,].

4. Discussion and Future Directions

4.1. RQ1 What Type of Robot Is Used in the Studies?

Based on the locomotion mechanisms, mobile wheeled robots are the dominant robot type (77.27%, 17/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]). This preference may be related to the motion stability of these mechanisms for navigation. However, it also suggests that there are locomotion mechanisms that have not been fully explored, such as rotary-wing drones (9.10%, 2/22: [,]). Furthermore, this highlights an area of opportunity in scenarios where kinematics or terrain would require the use of bipedal locomotion, which has not been found in the reviewed articles.

The results indicate that differential drive (8/22: [,,,,,,,]) and omnidirectional drive (36.36%, 8/22: [,,,,,,,]) are present in the 36.36% of the articles, while rocker-bogie (4.54%, 1/22: []) and Ackermann (4.54%, 1/22: []) are less used. The preference for differential-drive systems is likely influenced by the simplicity of their mechanical design and control, in contrast with omnidirectional and Ackermann-steered platforms, which are mechanically more complex. Therefore, the drive system may be more related to the advantages of the mechanical design and control rather than a specific social navigation aspect.

The robot appearance revealed that functional robots (50%, 11/22: [,,,,,,,,,,]) are used more often than bio-inspired robots (31.80%, 7/22: [,,,,,,]). This represents two approaches: functional robots for service-task scenarios where the performance is fundamental, and bio-inspired robots for human-like interaction, where the embodiment is the core characteristic of the study. However, the fact that 9.10% of the studies did not identify the robot’s appearance (2/22: [,]) indicates a possible reproducibility limitation. The distinction between commercial and non-commercial robots suggests that studies employing Pepper, or Beam Pro, could support their development on standardized software, whereas non-commercial robots may limit the generalization of SAN strategies.

Based on this, opportunity areas in terms of the robot type used in the studies could be:

- To explore underrepresented locomotion mechanisms (e.g., quadrupeds, cobots, drones) to evaluate how embodiment affects the interaction.

- To design multi-factorial experiments to compare how functional and bio-inspired appearances influence user perceptions.

- To establish minimum robot specification reporting standards (e.g., locomotion, drive system, speed/acceleration limits) for SAN research to improve reproducibility.

4.2. RQ2 What Sensors Are Used to Collect Data from Behavioral Cues to Enable Robot Motion in Socially Aware Navigation?

Vision-based technologies, including monocular cameras (7 articles: [,,,,,,]) and 3D-vision (7 articles: [,,,,,,]), were employed in most of the studies that reported sensors. This result may be influenced by the growing development of computer vision models. It was unexpected that the second most used sensor was the microphone (5 articles: [,,,,]). This suggests that current microphone technologies are adequate for correctly capturing and identifying speech or voice commands. Despite the use of VR headsets and controllers (3 articles: [,,]), the sensors in the headset are partially used and represent an area of opportunity in data collection. Despite a combination of sensors ([,,,,,,,,,,,]), we highlight that only one article reported the use of sensor fusion to improve the data collection process [].

It was unexpected that 27.27% of the studies did not specify their sensing technologies (6/22: [,,,,,]). Meanwhile, a few studies reported (22.73%) sensor specifications (e.g., latency, resolution, rate). Conversely, the majority of the studies did not provide details in this regard (77.27%, 17/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]). Missing information limits the methodological reproducibility.

Based on this, opportunity areas in terms of the sensors used to collect behavioral cues could be:

- To combine multimodal inputs (e.g., audio, tactile, haptic) using sensor fusion, so that robots could interact with people involving several behavioral cues as humans do.

- To integrate wearable technologies, such as VR headsets.

- To develop and integrate benchmarks for multimodal SAN sensing, including ground-truth reports.

- To require systematic reporting of sensor specifications (e.g., latency, frame rate, resolution) to improve methodological reproducibility.

4.3. RQ3 How Are Behavioral Cues Processed to Enable Robot Motion in Socially Aware Navigation?

Most studies processed sensor data on board the robot (50%, 11/22: [,,,,,,,,,,]), while a few relied exclusively on off-board processing (13.64%, 3/22: [,,]) and two use hybrid approaches (9.09%, 2/22: [,]). This highlights the preference for autonomy and real-time performance, although it demonstrates a limited use of hybrid or distributed architectures.

Regarding the types of behavioral cues, two categories were dominant: space and environment cues (11 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,]) and gesture and posture cues (10 articles: [,,,,,,,,,]). Less frequent behavioral cues include vocal behavior (3 articles: [,,]) and face/eye behavior (1 article: []). The focus on spatial and kinematic information suggests that SAN is mostly addressed as a kinematic or proxemic problem, rather than a different cognitive interpretation (e.g., context, memory, communication). Remarkably, no study reports the use of biological signals. In addition to the focus on spatial and kinematic information, this reveals a missed opportunity: vocal behaviors and biosignals, which could improve human–robot interaction.

Based on this, opportunity areas in terms of behavioral cue processing could be:

- To explore behavioral cues to incorporate voice intensities, or facial features.

- To include biosignals to contrast volunteers’ answers with physiological data and double-check the participant perception.

- To develop hybrid processing architectures, balancing robot autonomy with cloud-based heavy processing.

4.4. RQ4 To What Type of Environment and Situation Is the Robot Exposed in the Experiments Conducted to Assess SAN?

Most of the studies was performed in real-world environments (59.1%, 13/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,]), with fewer in simulation (36.36%, 8/22: [,,,,,,,]) and only one using hybrid approaches (4.54%, 1/22: []). Despite the majority of experiments being conducted in real-world settings, they are conducted in research laboratories (31.81%, 7/22: [,,,,,,]). It is desirable to use real-world scenarios that are not fully controlled to improve SAN. Moreover, most reported environments do not exploit digital twins.

In real-world environments, experiments with public setups were less frequent, such as shopping malls (4.55%, 1/22: []), warehouses (4.55%, 1/22: []), historical palaces (4.55%, 1/22: []), and offices (13.63%, 3/22: [,,]). Simulations, as expected, were typically used for simple scenarios (36.36%, 8/22: [,,,,,,,]). Experimental scenarios ranged from different applications. This reflects a diversity of locations and settings, but also, a lack of standardized benchmarks and baselines, making it difficult to compare the performance of navigation strategies across studies.

Based on this, opportunity areas in terms of environments and situations could be:

- To design standardized experimental scenarios with systematically varied social density, or interaction types.

- To conduct multi-location studies to validate findings across different contexts.

- To explore simulation-to-real navigation technologies (e.g., digital twins, virtual reality, cloud-based technologies) to increase the variability of scenarios.

4.5. RQ5 What Motion and Interaction Behaviors Drive the Robot’s Motion to Assess Socially Aware Navigation?

The behavior physical primitives were found in all experiments (22 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]). This behavior primitive includes several actions, such as velocity changes, orientation changes, stopping, lateral moves, and distancing. In contrast, auditory primitives (6 articles: [,,,,,]) and visual primitives (2 articles: [,]) were less frequent. This indicates a general focus on locomotion rather than multimodal expressivity to assess SAN. This may happen because most strategies focus on performance during navigation rather than social interaction. At the same time, it could represent a barrier since not all possible communication channels are explored. Particularly in the case of visual primitives, we identified an area of opportunity to explore visual mechanisms that support the robot’s motion.

The social conventions most frequently addressed were personal space management (e.g., [,,]), and group joining behavior (e.g., [,]). This could be due to the influence of the study of personal space (i.e., proxemics) that is developed in HRI. Few studies involved unique social conventions such as dance improvisation (1 study: []) and tour guiding (1 study: []), which reinforces the diversity of SAN discussed before. In general, our preliminary results suggest that there is no dominant social convention, which might suggest the need for a unifying framework.

Regarding theoretical frameworks, static behavioral models (59.10%, 13/22: [,,,,,,,,,,,,]) and rule-based systems (27.27%, 6/22: [,,,,,]) were more frequent. Meanwhile, less frequent frameworks were reinforcement learning (9.09%, 2/22: [,]), and fuzzy neural networks (4.54%, 1/22: []). In this regard, rule-based models represent a transparent but inflexible framework, while machine learning approaches improve adaptation but imply concerns regarding the explainability of the behavior. The preference for static, rule-based systems is related to the preference for kinematics-based behavioral cues observed in RQ3 and the controlled laboratory environments of RQ4. Although these preferences collectively may be a well-established setup, it suggests a need to explore different setups and decision-making schemes.

Based on this, opportunity areas in terms of behavior primitives and navigation goals could be:

- To establish a taxonomy of SAN behavior primitives in concordance with recent trends and with a clear map to the navigation goals involved.

- To develop multimodal strategies combining behavior primitives, such as motion, audio, and visual cues, to improve legibility.

- To implement multi-objective navigation planners, balancing operational efficiency, comfort, and safety under social constraints.

- To perform studies to measure the contribution of different primitives in human-to-human interaction.

- To increase the development of cross-cultural SAN models.

- To combine rule-based safety constraints with machine learning frameworks for more flexible and robust navigation.

- To establish safety frameworks or protocols to improve SAN in general scenarios.

4.6. RQ6 Which Evaluation Metrics Were Used to Assess the Robot’s Social Performance?

The qualitative metrics identified were primarily questionnaires (14 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,]). In this regard, there is a significant use of custom questionnaires, in contrast with standardized instruments such as RoSAS (3 articles: [,,]) or Godspeed questionnaires (1 article: []). A few studies applied scores (1 article: []) or visual analysis (1 article: []). In general, the use of Likert scale questionnaires stands out as the most appropriate tool for assessing participants’ subjective perceptions. This reliance on non-standard metrics limits the comparability across studies, but is consistent with the diversity of settings (RQ4), social conventions addressed (RQ5), and navigation goals (RQ5) previously identified.

The quantitative metrics identified were primarily performance ratios (7 articles: [,,,,,,]) and time-based metrics (7 articles: [,,,,,,]). Frequency-based (5 articles: [,,,,]) and distance-based (4 articles: [,,,]) measures were also common. Although the articles use qualitative and quantitative metrics in parallel, the studies reviewed do not include assessment tools that measure task efficiency and social acceptance at the same time, i.e., that effectively connect qualitative and quantitative aspects.

Statistical testing balanced parametric (40.91%, 9/22: [,,,,,,,,]) and non-parametric tests (31.81%, 7/22: [,,,,,,]), but power analyses were rare (2/22: [,]). Furthermore, 18.18% of articles did not include a statistical test (4/22: [,,,]). This reveals a considerable weakness in the planning of the experimental arrangements, i.e., the lack of general guidelines for a correct statistical planning of the data analysis. Safety considerations were explicitly mentioned in only 8 of 22 studies ([,,,,,,]). However, they are usually implemented through reactive mechanisms, such as distance-based, velocity-based, or emergency stops. The absence of safety mechanisms contrasts with the increasing regulations in ethical protocols, since their increase will promote the inclusion of security mechanisms.

Based on this, opportunity areas in terms of evaluation metrics could be:

- To develop standardized instruments based on fundamental social conventions and promote the use of already standardized instruments (e.g., RoSAS, Godspeed).

- To promote robust statistical practices, including power analysis, effect sizes, and methodological pipelines.

- To improve the safety evaluation mechanism to include dangers or undesired behaviors beyond collision avoidance.

4.7. RQ7 Were Participants Involved in the Experiments?

Sample sizes varied from small exploratory studies (1 study: [], 5 participants) to large-scale cross-cultural studies (1 study: [], 774 participants). Gender was reported in 15 of 22 studies (15 articles: [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,]), with a male majority in 11 of the articles reporting the gender. Age was reported in 17 studies [,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,], most participants were students (7 articles: [,,,,,,]), with exceptions such as professional dancers (1 study: []), and store customers (1 study: []). This strong reliance on young and student populations could represent a bias for the representation of the target population, since young people have a greater connection with technology. Feedback was collected in 13 of 22 studies (59.10%), mostly via interviews (7 articles: [,,,,,,]). However, 9 articles (40.91%) did not provide any feedback report ([,,,,,,,]). It can be observed that, although SAN is a human-centered field, just over 40% of the studies did not explicitly request feedback from participants.

Based on this, future directions for research in terms of the participation of volunteers could be:

- To improve demographic reporting standards (e.g., gender, age, cultural background) in SAN studies. Although sociodemographic analysis is not required for research design in human–robot interaction, demographic variables play a key role in analyzing the sociability in human–robot interaction and in comparing results of studies across populations to identify sociocultural differences. Therefore, the results of this review suggest that studies should report demographic variables such as age, gender, and country of residence, as well as whether the participant has previous experience with robots.

- To design questionnaires that collect the participants’ feedback during the interaction with the robot.

- To collect biosignals from the participants (e.g., electroencephalography signals, electrodermal activity, respiration) in order to analyze their emotions and reactions while they are interacting with the robot. None of the studies included in this review has used sensors to collect biological activity from the participants during the interaction.

- To promote workshops in the scientific, academic, and industrial communities in order to explore experimental designs for human–robot interaction in real scenarios and to collect feedback from participants and stakeholders, so that guidelines could be obtained for further research in terms of SAN strategies and experimental design.

4.8. Limitations

This scoping review presents the following limitations that should be considered in the interpretation of the results:

- Databases (DBs): The search was limited to a specific set of databases. Although these cover several relevant studies, it is possible that studies published in other sources may have been excluded from the analysis.

- Keywords: The keywords include “behavior” in the title and “robot”, and “interaction” in the document. These keywords were selected based on the selection of previous work presented in Table 1. Additionally, based on [,,] the keywords “human”, “aware”, and “navigation” were included. Nevertheless, studies using related terms or variations such as “human-computer”, “social awareness” or “social behavior” may have been excluded.

- Access: Only studies that were open access or accessible through the author’s institution were analyzed. This may have introduced selection bias by excluding works published in non-accessible sources.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This scoping review mapped the current state of motion techniques in socially aware navigation (SAN), identifying trends, methodological gaps, and opportunity areas. The review of 22 studies found wheeled robots with differential or omnidirectional drive systems. As well as a focus on functional robots in contrast with bio-inspired appearance. Experiments were frequently conducted in controlled laboratory environments, although there is an interest in public or cultural spaces. A domain of computer vision technologies to assess behavioral cues was observed, specifically color cameras, while multimodal sensing (e.g., tactile, audio, biosignals) remains underexplored. Only a minority of the studies reported sensor specifications or acquisition parameters, which restricts reproducibility. The processing of behavioral cues is focused on spatial and kinematic signals, with limited attention to voice, gaze, or biosignals that could improve social understanding. Regarding the evaluation, most studies relied on custom questionnaires or performance ratios, while a few studies used validated instruments such as RoSAS or Godspeed questionnaires. Several statistical analysis approaches were used, and only two studies reported power analyses. Although participant feedback is considered in some studies, almost half omitted it.

Based on this review, several directions for future work are identified. The lack of shared frameworks in robot description, sensing, and evaluation metrics represents different challenges for experimental comparability. Therefore, to advance the maturity of the SAN field, methodological standardization and integration of multimodal approaches are required. A development of minimum reporting standards for robot characteristics, sensing technologies, and evaluation metrics is also needed to improve cross-study comparison. Additionally, there is a need to integrate underexplored behavioral cues, modalities, and biosignals to enrich the robot’s interpretation of the interaction. Regarding experimental evaluation, it is necessary to establish validated and standardized instruments for different social conventions and promote robust statistical practices such as power analyses and effect size reporting. Incorporating systematic feedback instruments after experimentation is also necessary to double-check volunteers’ perceptions. Finally, it is recommendable to conduct experiments across multiple cultural, demographic, and situational contexts in order to address generalizable principles for SAN. In conclusion, the scoping review demonstrates progress in robot motion and the integration of social behaviors in socially aware navigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.E.H.-D. and A.M.-H.; data curation, J.E.H.-D.; methodology, J.E.H.-D. and E.J.R.-R.; formal analysis, J.E.H.-D.; writing—original draft preparation, J.E.H.-D.; writing—review and editing, J.E.H.-D., A.M.-H. and E.J.R.-R.; supervision, A.M.-H. and E.J.R.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the APC was funded by Universidad Veracruzana.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

J.E. Hermosilla-Diaz thanks Mexican National Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation Secihti (Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación) for funding his PhD studies (CVU number: 1150011).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mavrogiannis, C.; Baldini, F.; Wang, A.; Zhao, D.; Trautman, P.; Steinfeld, A.; Oh, J. Core Challenges of Social Robot Navigation: A Survey. J. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2023, 12, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, M.M.; Ben Allouch, S. Exploring influencing variables for the acceptance of social robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1476–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiders, E.; Kanstrup, A.M.; Kjeldskov, J.; Skov, M.B. Domestic Robots and the Dream of Automation: Understanding Human Interaction and Intervention. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’21), Yokohama, Japan, 8–13 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, T.; Pandey, A.K.; Alami, R.; Kirsch, A. Human-aware robot navigation: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2013, 61, 1726–1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Martinez, J.; Spalanzani, A.; Laugier, C. From Proxemics Theory to Socially-Aware Navigation: A Survey. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2015, 7, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinciarelli, A.; Pantic, M.; Bourlard, H.; Pentland, A. Social signal processing: State-of-the-art and future perspectives of an emerging domain. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Multimedia (MM ’08), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 26–31 October 2008; pp. 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klančar, G.; Zdešar, A.; Blažič, S.; Škrjanc, I. Chapter 2—Motion Modeling for Mobile Robots. In Wheeled Mobile Robotics; Klančar, G., Zdešar, A., Blažič, S., Škrjanc, I., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 13–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, T.; Soma, R.; Holthaus, P. Movement acts in breakdown situations: How a robot’s recovery procedure affects participants’ opinions. Paladyn J. Behav. Robot. 2021, 12, 336–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, H.; Akgun, S.A.; Saleh, S.; Dautenhahn, K. A survey on the design and evolution of social robots — Past, present and future. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2022, 156, 104193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venture, G.; Kulić, D. Robot Expressive Motions: A Survey of Generation and Evaluation Methods. J. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2019, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascher, M.; Gruenefeld, U.; Schneegass, S.; Gerken, J. How to Communicate Robot Motion Intent: A Scoping Review. In Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’23), Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nocentini, O.; Fiorini, L.; Acerbi, G.; Sorrentino, A.; Mancioppi, G.; Cavallo, F. A Survey of Behavioral Models for Social Robots. Robotics 2019, 8, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillén Ruiz, S.; Calderita, L.V.; Hidalgo-Paniagua, A.; Bandera Rubio, J.P. Measuring Smoothness as a Factor for Efficient and Socially Accepted Robot Motion. Sensors 2020, 20, 6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, F.; Kraus, J.; Baumann, M. Findings From A Qualitative Field Study with An Autonomous Robot in Public: Exploration of User Reactions and Conflicts. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2022, 14, 1625–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, S.; Jouaiti, M.; Hoey, J.; Nehaniv, C.L.; Dautenhahn, K. The Role of Social Norms in Human–Robot Interaction: A Systematic Review. J. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2025, 14, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Perceived Appropriateness: A Novel View for Remediating Perceived Inappropriate Robot Navigation Behaviors. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2023 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (HRI ’23), Stockholm, Sweden, 13–16 March 2023; pp. 781–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chan, I.Y.; Dong, Z.; Guo, Q.; Hong, J.; Twum-Ampofo, S. Biosignal measurement for human-robot collaboration in construction: A systematic review. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 68, 103652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, A.; Pérez-D’Arpino, C.; Li, C.; Xia, F.; Alahi, A.; Alami, R.; Bera, A.; Biswas, A.; Biswas, J.; Chandra, R.; et al. Principles and Guidelines for Evaluating Social Robot Navigation Algorithms. J. Hum.-Robot Interact. 2025, 14, 1–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, K.; Kostavelis, I.; Gasteratos, A. Recent trends in social aware robot navigation: A survey. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2017, 93, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanian, O.; Karimi, G. Locomotion Systems in Robotic Application. In Proceedings of the 2006 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics, Kunming, China, 17–20 December 2006; pp. 689–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, F.; Valero, F.; Llopis-Albert, C. A review of mobile robots: Concepts, methods, theoretical framework, and applications. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2019, 16, 1729881419839596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraka, K.; Alves-Oliveira, P.; Ribeiro, T. An Extended Framework for Characterizing Social Robots. In Human-Robot Interaction: Evaluation Methods and Their Standardization; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 21–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, V.R.; Rao, V.S. Exploring Modern Sensor in Robotics: A review. In Proceedings of the 2024 Asia Pacific Conference on Innovation in Technology (APCIT), Mysore, India, 26–27 July 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Gomez, J.; Fernandez-Caballero, A.; Garcia-Varea, I.; Rodriguez, L.; Romero-Gonzalez, C. A Taxonomy of Vision Systems for Ground Mobile Robots. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2014, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethel, C.L.; Salomon, K.; Murphy, R.R.; Burke, J.L. Survey of Psychophysiology Measurements Applied to Human-Robot Interaction. In Proceedings of the RO-MAN 2007-The 16th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 26–29 August 2007; pp. 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]