4.4.1. Performance Comparison Between EDF-NSDE and Other Fusion Baselines

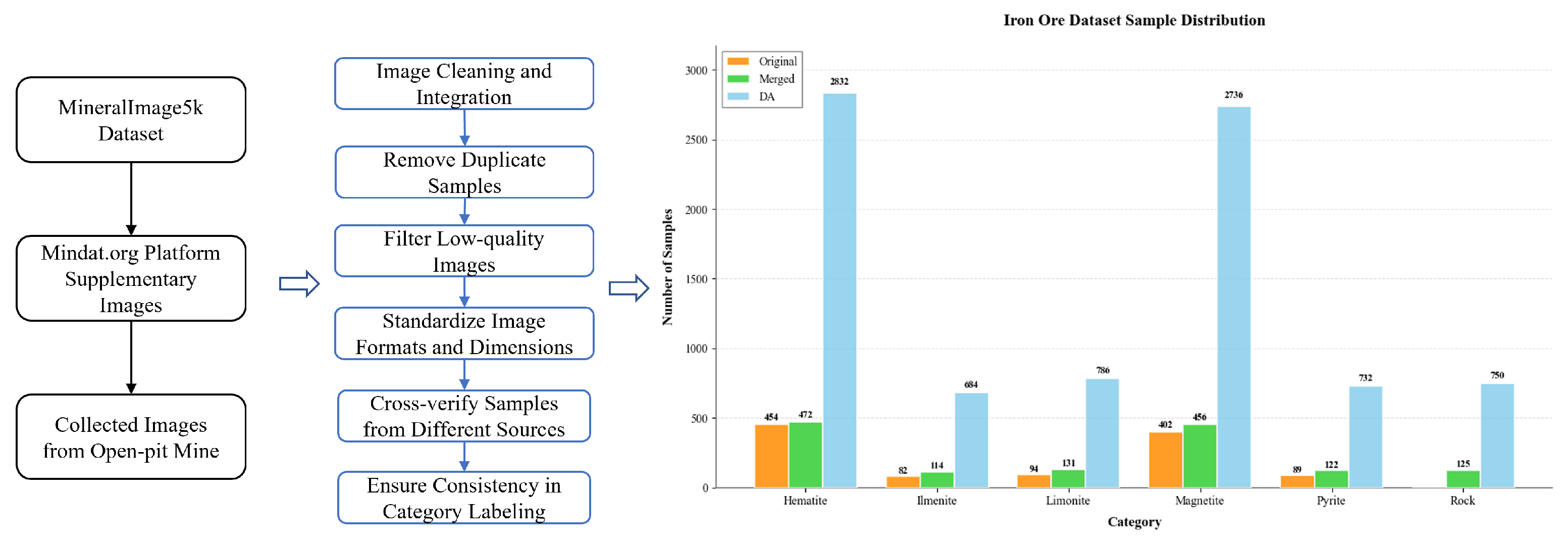

As shown in

Table 3, EDF-NSDE demonstrates superior performance across all evaluation metrics. On the original test set, EDF-NSDE achieves an accuracy of 84.86% and F1-score of 84.76%, outperforming all eight other models. On the data-augmented test set, EDF-NSDE attains an accuracy of 88.38%, precision of 87.05%, recall of 88.76%, and F1-score of 87.86%, achieving optimal or tied optimal performance across all four metrics. These results indicate that evolutionary-driven multi-view feature fusion effectively enhances classification reliability and robustness.

Regarding model complexity, EDF-NSDE has a speed of 11.5G FLOPs and 29.31M Params, comparable to high-capacity models like InceptionV3 (11.5G and 29.29M) and ResNet50 (8.27G and 26.14M). Despite this moderate complexity, its performance gains are substantial: a 2.11% accuracy improvement over DenseNet121 (the best single model on original data) and a 1.70% F1-score improvement over InceptionV3. This trade-off is justified as evolutionary fusion integrates complementary representations from diverse base learners while mitigating single model biases. For industrial real-time systems, EDF-NSDE’s complexity is deployable on edge devices with moderate computing resources, making it feasible for on-site mineral detection where precise classification outweighs marginal complexity increases.

On the original dataset, EDF-NSDE achieves significant improvements over individual models. Compared to the best single model DenseNet121 (accuracy 82.75%), EDF-NSDE demonstrates an accuracy improvement of 2.11%. Relative to InceptionV3 (F1-score 83.06%), EDF-NSDE achieves an F1-score improvement of 1.70%. Compared to lightweight models, EDF-NSDE shows substantial gains: 5.63% over MobileNetV3 (accuracy 79.23%), 4.93% over ResNet50 (accuracy 79.93%), and 7.75% over AlexNet (accuracy 77.11%). These improvements demonstrate that evolutionary search effectively integrates complementary representations from diverse base learners while mitigating performance bottlenecks caused by single-model bias.

After data augmentation, EDF-NSDE maintains its competitive advantage. Compared to the best single model ResNet50 (accuracy 87.32% and F1-score 86.62%), EDF-NSDE achieves improvements of 1.06 and 1.24% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively. Relative to DenseNet121 (accuracy 86.97% and F1-score 86.77%), the improvements are 1.41 and 1.09%, respectively. The recall improvement is particularly notable, with EDF-NSDE achieving 88.76% compared to ResNet50’s 86.74%, indicating more robust detection of minority classes. These results suggest that the complementarity of multi-view features is further amplified after augmentation as evolutionary search automatically identifies sub-models with different sensitivity to augmentation and adaptively configures operators and weights.

The performance analysis reveals distinct advantages across different model categories. Compared to lightweight models (ShuffleNetV2 and MobileNetV3), EDF-NSDE achieves larger F1-score improvements, indicating better inter-class separation on decision boundaries of easily confused classes. Compared to high-capacity models (ResNet50 and InceptionV3), EDF-NSDE demonstrates more stable advantages in recall and F1-score, reflecting superior generalization with data distribution changes. The method’s ability to maintain higher consistency (precision) and coverage (recall) under noise perturbation conditions and appearance variations demonstrates the effectiveness of the evolutionary multi-objective optimization framework in balancing performance and complexity constraints.

Unlike conventional large convolutional neural networks (CNNs) that demand computationally intensive end-to-end fine-tuning, EDF-NSDE operates exclusively at the feature level and requires only a lightweight linear classifier to render the final decision. This design effectively minimizes computational and storage overhead, making it highly suitable for online inference and rapid iteration in industrial environments with limited resources.

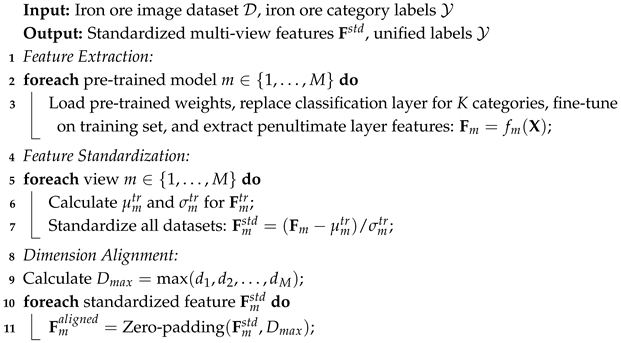

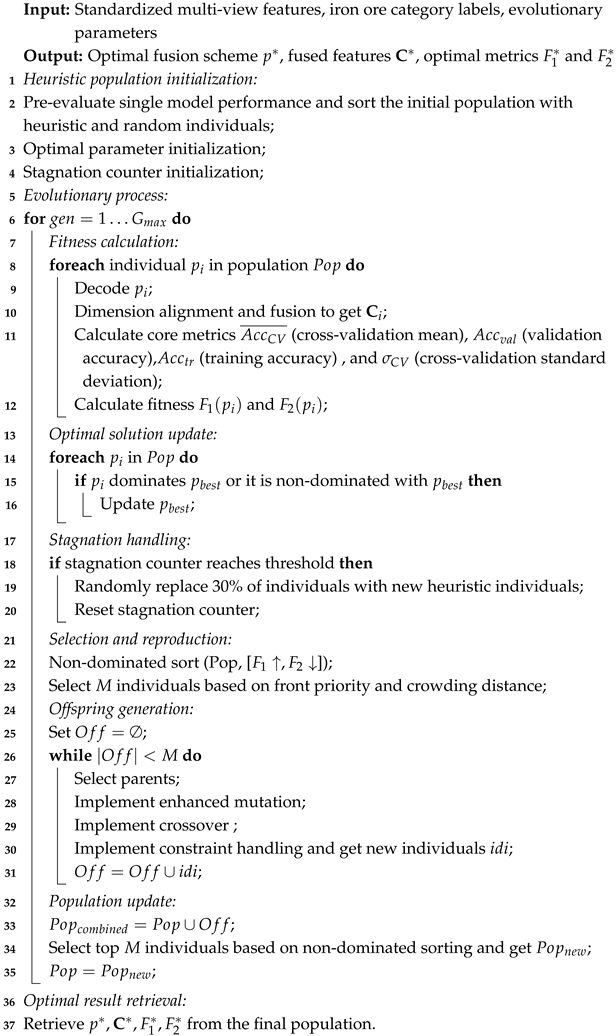

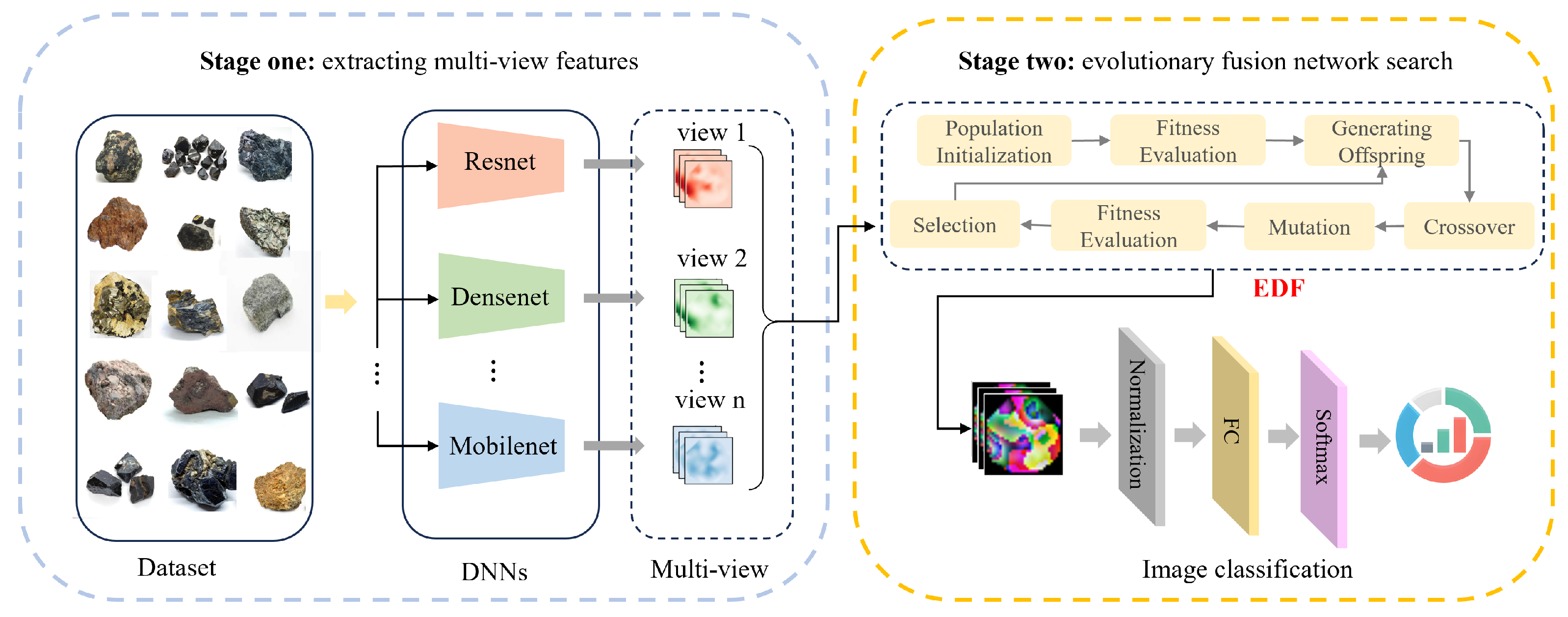

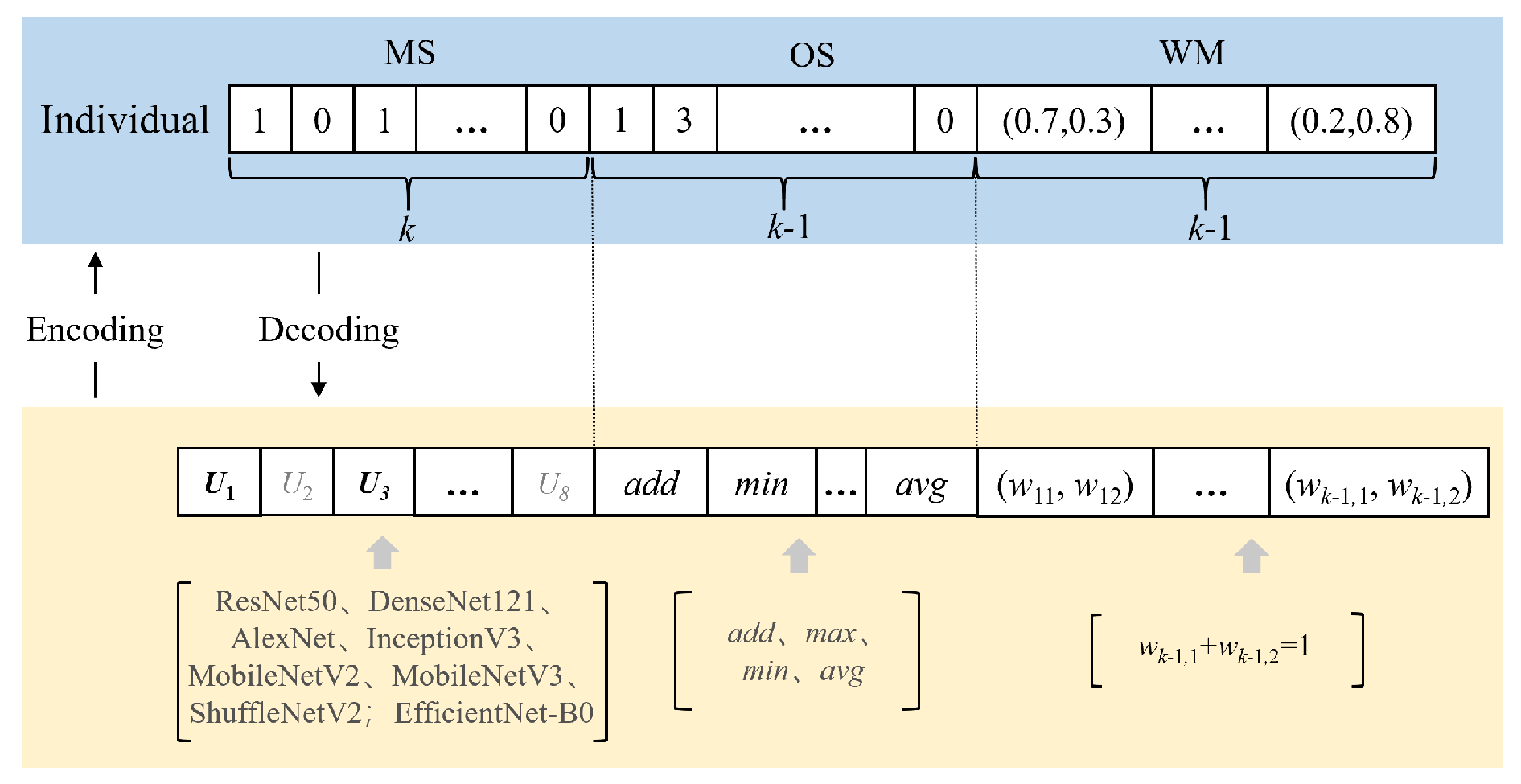

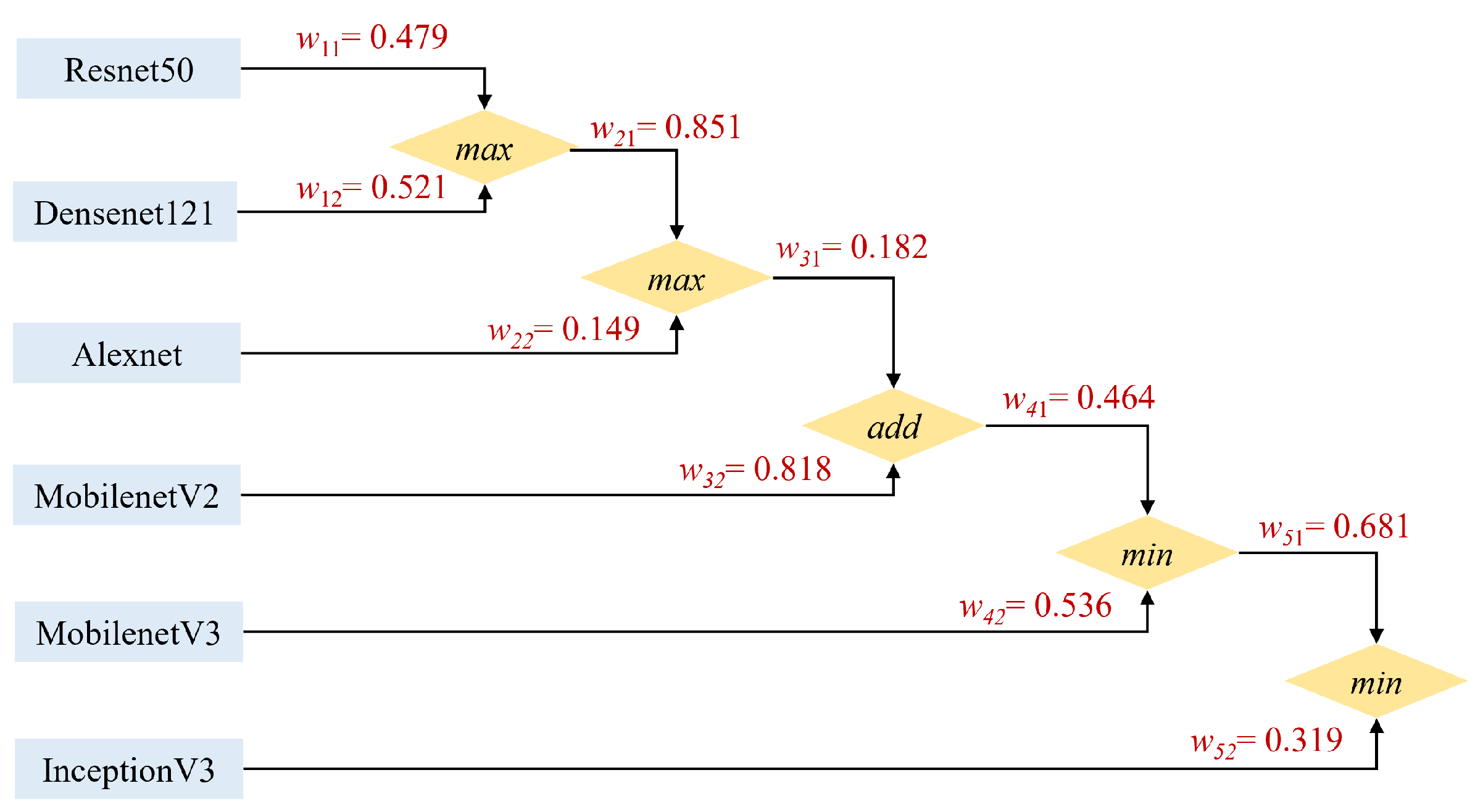

Figure 5 illustrates how the selected backbones first extract features in parallel, followed by being subjected to the sequential element by element fusion steps detailed in the figure caption. This figure depicts the optimal fusion architecture identified using the original dataset and demonstrates how EDF-NSDE automatically acquires efficient feature combination strategies.

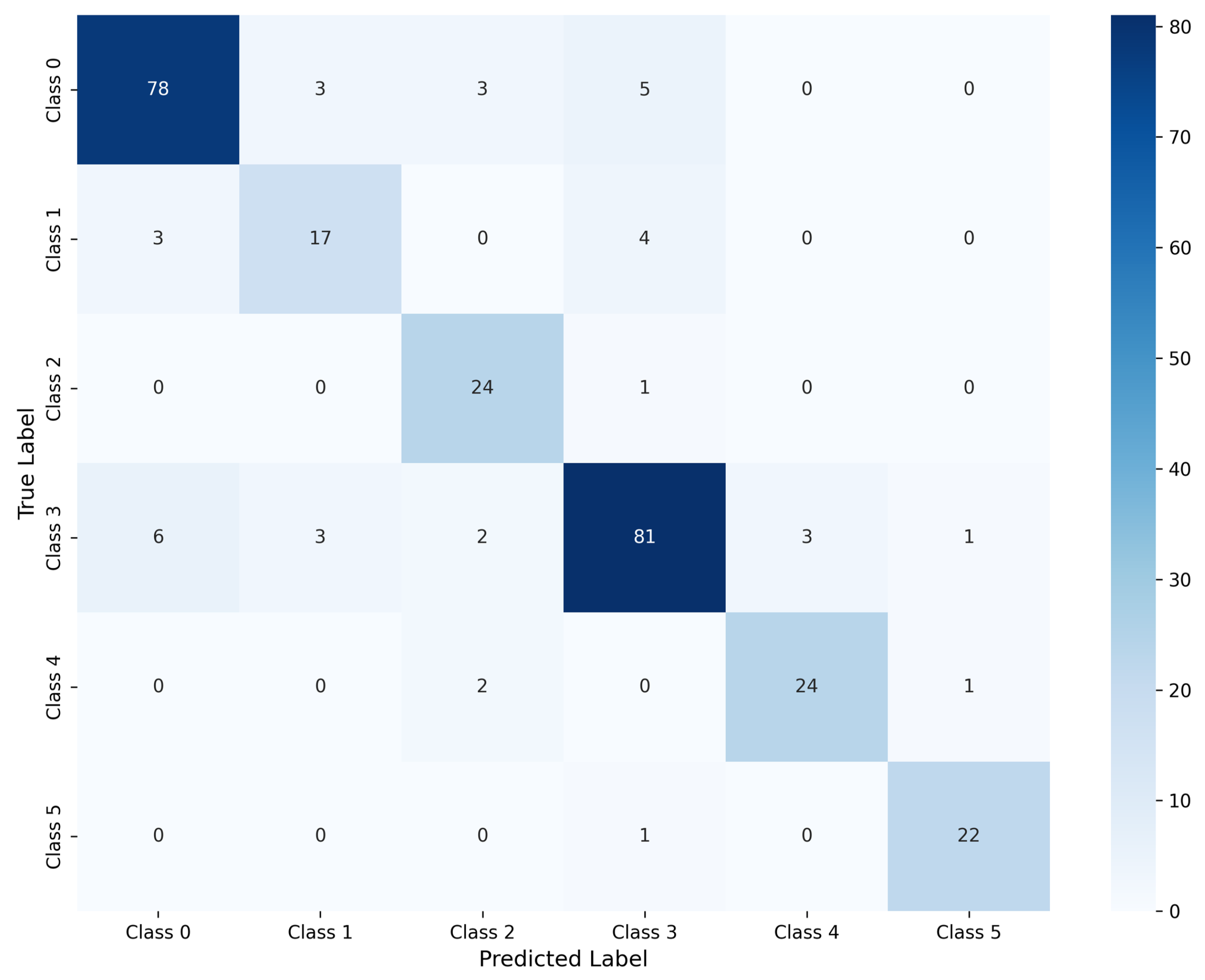

To quantitatively evaluate the fused-feature classifier, we analyzed its confusion matrix (refer to

Figure 6). The model attains an overall accuracy of approximately 86.62%, indicating strong capability in distinguishing the six classes.

At the class level, Class 0 achieves a precision of 89.66% and a recall of 87.64%, reflecting robust recognition. Class 3 also performs well with a precision of 88.04% and a recall of 84.38%. Classes 2, 4, and 5 exhibit even higher precision (85.71%, 92.31%, and 91.67%) and recall (96.00%, 88.89%, and 95.65%), suggesting very high separability for these categories. In contrast, Class 1 shows comparatively lower precision (73.91%) and recall (70.83%), with notable confusion against Classes 0 and 3—likely due to intrinsic feature similarities. Minor misclassifications are also observed between Classes 2 and 3, as well as among Classes 0, 1, and 3, pointing to avenues for enhancing the feature discriminability of these specific class pairs. Overall, the fused-feature model delivers strong and balanced performance across most classes.

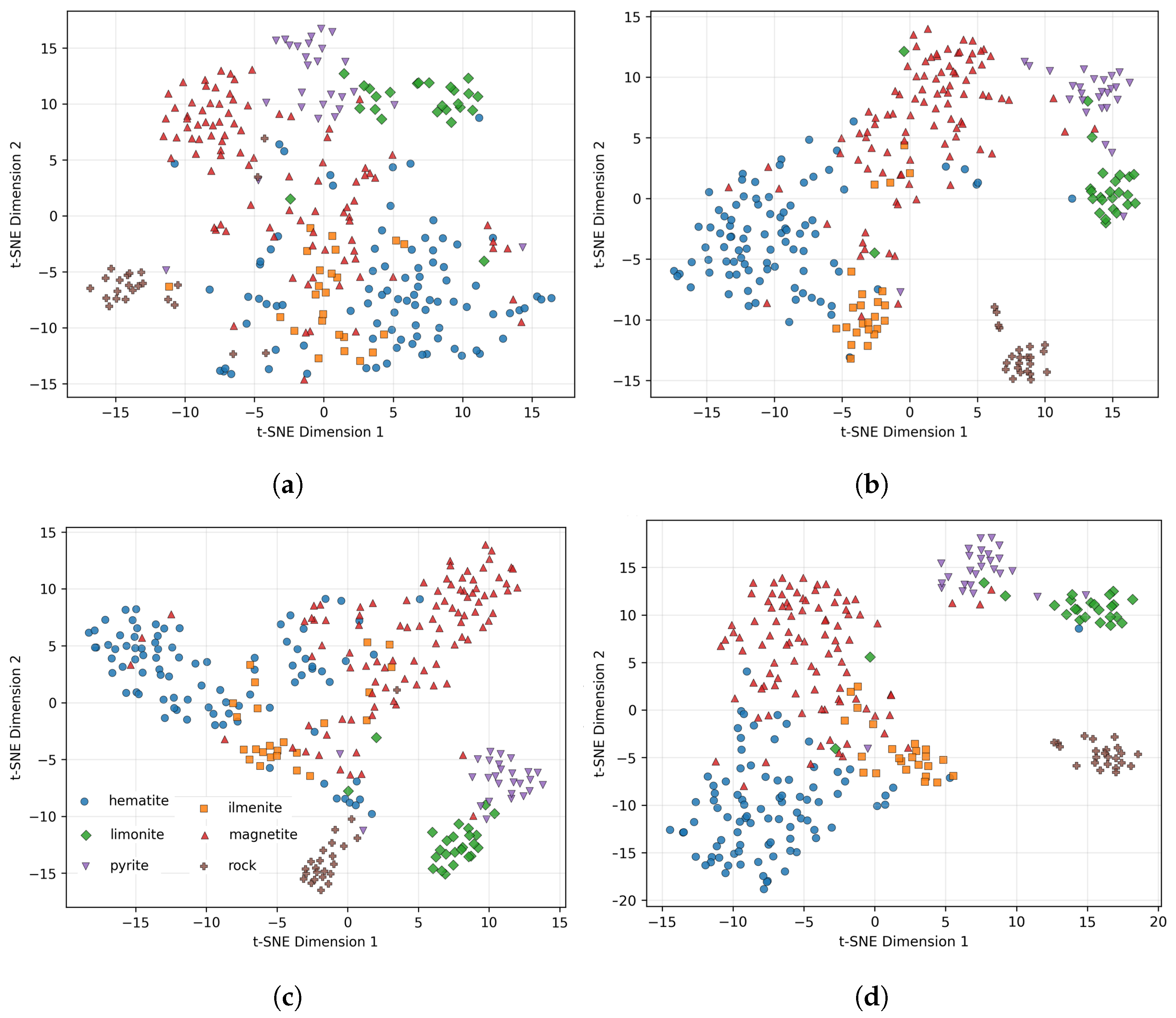

To intuitively evaluate whether the feature representations learned by each model have good class separability, we used t-SNE to reduce high-dimensional test features to two dimensions and compare the distributions of AlexNet, DenseNet121, EfficientNet, and EDF-NSDE features in the same plot. This visualization can demonstrate intra-class compactness and inter-class separation, thereby verifying whether the fusion strategy effectively improves representation quality and helping to identify major confusion classes for subsequent model improvement and ablation analysis.

As observed from

Figure 7, for AlexNet (

Figure 7a), the feature distribution is relatively scattered with significant overlaps between clusters, and inter-class boundaries are unclear. Specifically, hematite and ilmenite, as well as magnetite, show obvious overlapping phenomena; pyrite and rock are relatively independent but still have some scattered points close to other classes. For DenseNet121 (

Figure 7b), the class structure begins to separate, and tighter clusters emerge. Magnetite, pyrite, and rock form relatively tight clusters with clearer boundaries, while hematite and ilmenite still overlap, remaining a pair of difficult-to-distinguish classes. For EfficientNet (

Figure 7c), the overall separability is further improved. Multiple classes are distributed along manifolds, and the clusters become tighter compared with DenseNet121. Pyrite and rock are relatively concentrated with good inter-class separation; the boundaries between limonite and magnetite are significantly clearer than those in AlexNet.

For our EDF-NSDE model (

Figure 7d), the features present the tightest class clusters and the best inter-class separation. Pyrite (purple) and rock (brown) are completely independent, and limonite (green) forms clear and compact clusters on the right side of the figure. The aggregation of hematite (blue) is significantly improved, but there is still local overlap with ilmenite (orange) and some magnetite (red), which is the main source of classification confusion. Visually, the features of EDF-NSDE have the largest inter-class intervals and the smallest intra-class variance, indicating that the proposed fusion strategy effectively improves the separability and robustness of feature representations.

4.4.2. Ablation Study

From

Table 4, EDF-NSDE achieves the highest performance on the original dataset with accuracy of 84.86% and F1-score of 84.76%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the integrated optimization framework. The ablation study reveals the individual contributions of each component to the overall performance.

Single-objective optimization results in performance degradation of 2.82 and 2.95% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively, compared to the complete EDF-NSDE. This substantial decline demonstrates that multi-objective optimization, which simultaneously considers accuracy, model count, and the generalization gap, is significantly superior to pursuing accuracy alone, confirming the effective balancing role of NSGA-II in the optimization process.

Removing differential evolution leads to the largest performance decline, with accuracy and F1-score decreasing by 3.52% and 3.65%, respectively. This result indicates that differential evolution contributes most substantially to exploring solution diversity and enhancing search efficiency, making it a critical component of the optimization framework.

The removal of the generalization penalty results in relatively modest performance decreases of 1.76 and 1.73% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively. Although the quantitative impact is smaller, the generalization penalty plays a crucial role in improving model generalization and effectively suppressing overfitting, particularly important for robust performance in real-world scenarios.

Random initialization leads to performance degradation of 2.74 and 1.81% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively. This result demonstrates that heuristic initialization provides a superior starting point for the evolutionary process, accelerating convergence and improving the quality of the final solution.

The fixed mutation strategy results in performance decreases of 3.17% and 3.19% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively. This outcome confirms that adaptive mutation is superior to fixed strategies as it dynamically adjusts the exploration–exploitation balance according to different evolutionary stages.

In summary, all components contribute substantially to the overall performance, with differential evolution and adaptive mutation having the greatest impact, followed by multi-objective optimization and heuristic initialization. The generalization penalty, while showing smaller quantitative improvements, stably enhances generalization capability. The complete EDF-NSDE achieves optimal performance through the synergistic integration of multi-objective optimization, differential evolution, generalization regularization, heuristic initialization, and adaptive mutation strategies.

4.4.3. Training Dynamics, Overfitting Analysis, and Generalization Performance

Small-sample scenarios tend to exacerbate the risk of overfitting, especially for fusion strategies integrating multiple high-capacity backbones. Although EDF-NSDE enhances recognition accuracy, its training behavior requires verification to confirm that the performance gains do not originate from memorization of the limited training set. Therefore, we monitored the joint evolution of loss and accuracy to characterize the convergence and generalization performance at the given data scale.

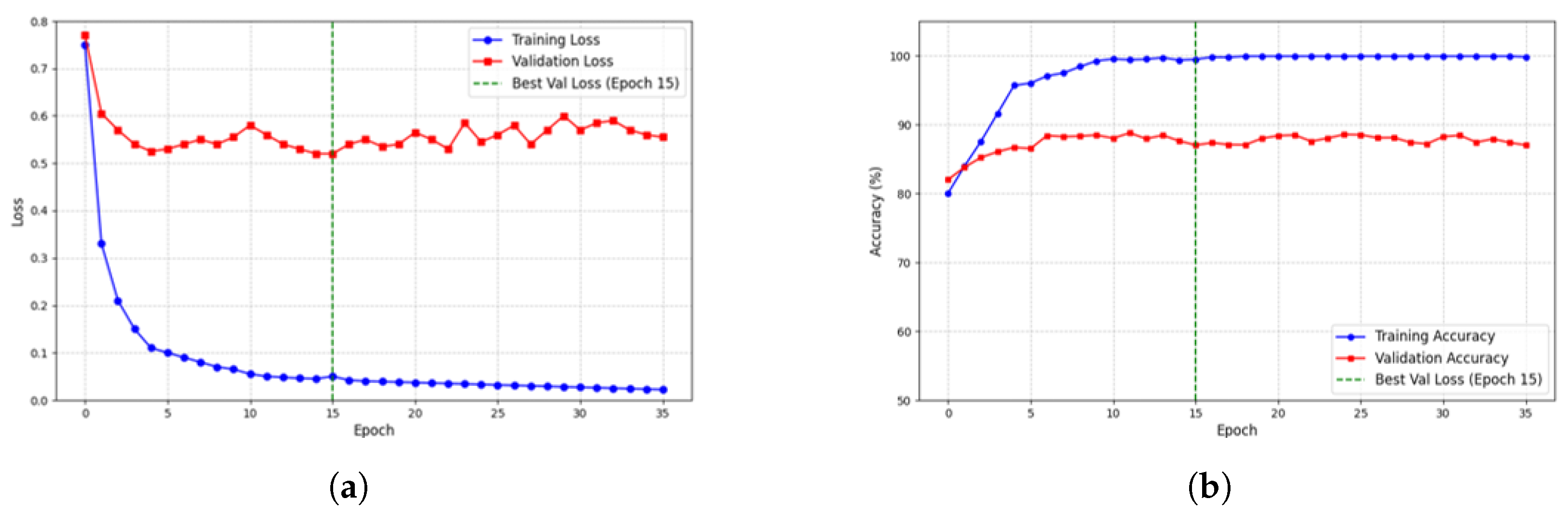

Figure 8a demonstrates that the training loss declines sharply in the initial epochs and stabilizes near 0.04, while the validation loss reaches its minimum at approximately epoch 15 (around 0.52) before oscillating within a narrow range of

. The limited separation between the two curves indicates that EDF-NSDE rapidly internalizes the training distribution while mitigating the generalization gap; no divergence in the validation loss is detected after the early optimum, suggesting that extreme overfitting is avoided despite the small sample size.

Figure 8b corroborates these findings in terms of accuracy. The training accuracy saturates at close to

within five epochs, whereas the validation accuracy improves more gradually and stabilizes between

and

. The persistent gap of approximately 10 percentage points quantifies the extent of residual overfitting, but the plateaued validation curve illustrates stable predictive capability on unseen data. Taken together, the two trajectories confirm that EDF-NSDE converges efficiently while retaining acceptable generalization performance in the small sample regime.

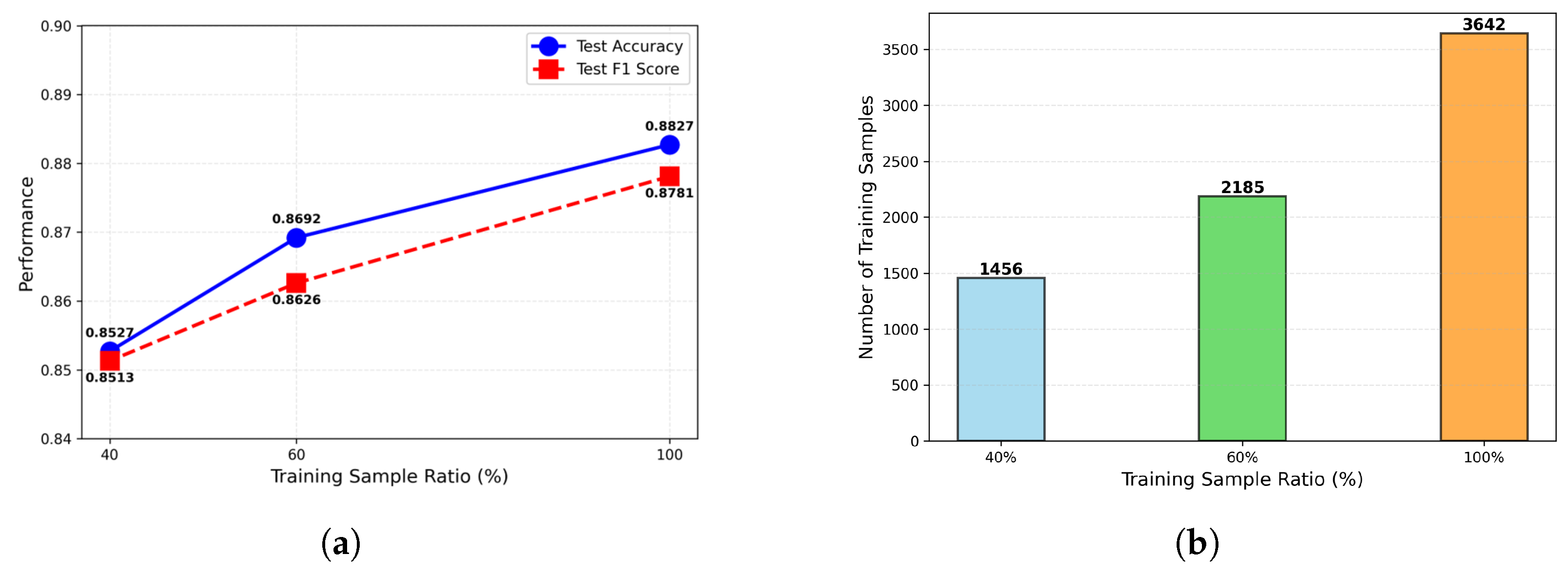

To address the generalization success of the proposed method for different sample sizes, we conducted comprehensive experiments using training ratios of 100%, 60%, and 40% of the original training set. The experiments were performed with stratified sampling to maintain the class distribution, ensuring fair comparison across different sample sizes. As illustrated in

Figure 9, the method demonstrates robust performance across all sample sizes.

As shown in

Figure 9a, when reducing training samples from 100% (3,642 samples) to 40% (1456 samples), the test accuracy decreased by 0.03 (3.40%), from 0.8827 to 0.8527. Similarly, the test F1-score decreased from 0.8781 to 0.8513, representing a reduction of 0.0268 (3.05%). The test accuracy at 60% training ratio (2,185 samples) reached 0.8692, demonstrating that the method maintains strong performance even with moderate sample reduction. These results demonstrate strong robustness of the proposed method across different training sample sizes.

4.4.4. Performance Comparison Between EDF-NSDE and Fusion Baseline Methods

Different fusion operators exhibit distinct inductive biases for feature statistics, including amplitude distribution, outlier robustness, and discriminative peak preservation, which directly influence downstream classification boundaries and generalization performance. To systematically evaluate operator compatibility and performance differences, we conducted controlled experiments by replacing fusion operators while maintaining identical model combinations and training configurations.

We selected four representative sub-models as base classifiers: DenseNet121, MobileNetV2, EfficientNet-B0, and MobileNetV3. Following the existing multi-operator fusion baseline scheme with the operator sequence (Max, Min, Max) and corresponding weight matrix [[0.192, 0.808], [0.684, 0.316], [0.583, 0.417]], we conducted single-operator fusion control experiments. These experiments isolated the influence of optimizer and weight search by changing only the terminal fusion operator to Add, Max, Min, or Avg while keeping all other training and validation settings consistent.

The results in

Table 5 reveal significant performance differences among fusion operators. Min and Avg operators substantially outperform Add and Max operators in both accuracy and F1-score. Specifically, Min achieves 82.92% accuracy and 83.17% F1-score, while Avg attains 82.89% accuracy and 82.86% F1-score. In contrast, Max and Add operators achieve 82.29%/81.98% and 81.75%/80.48% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively.

These results indicate that for the current sub-model output distribution, more conservative aggregation strategies (Min) and smoother mean aggregation (Avg) better suppress individual model overconfidence and noise bias. Conversely, Max and Add operators are more susceptible to influence from single high-confidence but erroneous sub-models, leading to more significant F1-score degradation.

Although single-operator fusion already provides robust performance gains, the evolutionary search-based EDF-NSDE scheme achieves superior results, with 84.51% accuracy and 84.39% F1-score, exceeding the optimal single operator (Min) by approximately 1.6% and 1.2% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively. This advantage demonstrates that across different categories and sample difficulties, the optimal fusion strategy exhibits sample-adaptive characteristics, favoring conservative aggregation for easily confused categories while moderately amplifying the contribution of advantageous sub-models for high-confidence samples. This adaptive behavior is difficult to achieve with fixed single operators, highlighting the effectiveness of the evolutionary optimization approach.

4.4.5. Comparative Experiments on Public Datasets

To further validate the generalization capability of the proposed EDF-NSDE method, we conducted comprehensive comparisons with various other models on the data-augmented Kaggle 7-class mineral identification dataset. This cross-dataset evaluation demonstrates the method’s ability to adapt to different mineral types and imaging conditions beyond the original iron ore classification task. Evaluation metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, ensuring equal consideration of contributions from all classes under imbalanced conditions. As shown in

Table 6, EDF-NSDE selected models DenseNet121, ResNet50, and MobileNetV2 with fusion operators Max and Min and fusion weights [[0.624,0.376], [0.871,0.129]], achieving optimal performance across all four metrics: accuracy 92.51%, precision 92.62%, recall 91.83%, and F1-score 92.44%.

Compared to the best single model MobileNetV2 (accuracy 91.98% and F1-score 91.03%), EDF-NSDE demonstrates improvements of 0.53% in accuracy and 1.41% in F1-score. Compared to EfficientNet-B0 (accuracy 89.84% and F1-score 89.35%), EDF-NSDE achieves improvements of 2.67 and 3.09% in accuracy and F1-score, respectively. Compared to lightweight models and early architectures, EDF-NSDE exhibits more substantial advantages, particularly with F1-score improvement over AlexNet (83.07%) exceeding 9.37%. These results indicate that the fusion strategy significantly mitigates single model performance degradation on minority classes, demonstrating the effectiveness of the evolutionary multi-objective optimization approach in handling class imbalance scenarios.

The above benefits mainly stem from two points: first, the complementarity between multi-view features is explicitly modeled and fully exploited during evolutionary fusion, forming robust discriminative representations across texture, morphology, and color dimensions; second, the joint search mechanism of NSGA-II and differential evolution automatically selects more representative sub-model sets and fusion operator sequences under multi-objective constraints of performance and complexity, thereby maintaining stable advantages for different class distributions and interference conditions. Overall, EDF-NSDE not only improves overall accuracy on average but also enhances macro precision and recall, indicating more balanced recognition capability and stronger generalization across all classes.