Abstract

The rapid advancement of social media and the exponential increase in online information have made open-source intelligence an essential component of modern criminal investigations. However, existing digital forensics standards mainly focus on evidence derived from controlled devices such as computers and mobile storage, providing limited guidance for social media–based intelligence. Evidence captured from online platforms is often volatile, editable, and difficult to verify, which raises doubts about its authenticity and admissibility in court. To address these challenges, this study proposes a systematic and legally compliant open-source intelligence framework aligned with digital forensics principles. The framework comprises five stages: identification, acquisition, authentication, preservation, and validation. By integrating blockchain-based notarization and image verification mechanisms into existing forensic workflows, the proposed system ensures data integrity, traceability, and authenticity. The implemented prototype demonstrates the feasibility of conducting reliable and legally compliant open-source intelligence investigations, providing law enforcement agencies with a standardized operational guideline for social media–based evidence collection.

1. Introduction

Social media has become an indispensable component of modern communication, shaping how individuals interact, share content, and disseminate information. Popular platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and others collectively host billions of active users worldwide [1]. This extensive and diverse ecosystem provides a vast reservoir of publicly accessible information that can be leveraged for investigative purposes, particularly in open-source intelligence (OSINT) contexts.

Law enforcement agencies have increasingly utilized social media content to identify suspects and reconstruct criminal activities. A well-known example occurred after the 2021 U.S. Capitol riot [2], when the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) extensively used Facebook data and user-generated posts to identify participants and gather supporting evidence. Similarly, in the 2015 United Kingdom cyclist insurance fraud case [3], investigators analyzed Facebook photos to reveal inconsistencies between the suspect’s claims and his actual activities, ultimately leading to a criminal conviction. These cases demonstrate the evidentiary potential of open-source information available through Facebook.

Although digital forensics standards such as ISO/IEC 27037:2012 [4] and ISO/IEC 27043:2015 [5] provide comprehensive guidance for handling evidence from computers, mobile devices, and storage media, they offer limited applicability to open-source intelligence. Evidence obtained from social media platforms is typically volatile, may be altered or deleted remotely, and is often captured as screenshots without verifiable provenance. Such conditions make it difficult to prove authenticity and maintain evidential integrity in judicial proceedings. Consequently, ensuring the reliability of social media evidence has become a significant challenge in digital forensics and legal practice.

To address these challenges, this study advances three core contributions that differentiate it from prior OSINT or blockchain-based forensic research. First, we operationalize a complete OSINT evidence lifecycle that incorporates multi-factor user identity correlation before acquisition, ensuring that only attributable and case-relevant social media content is collected. This design responds directly to recurring judicial concerns about the inability to link social media accounts to real-world individuals. Second, the proposed system supports both on-site OSINT acquisition for first responders and office-based OSINT processing, reflecting the realities of criminal investigation workflows and enabling consistent handling of OSINT across operational contexts. Third, we introduce on-acquisition notarization through a permissioned judicial blockchain infrastructure, providing immediate and cross-agency verifiable proof of evidentiary integrity, authenticity, and timing for volatile OSINT. These three components collectively close the OSINT-to-courtroom gap and establish an end-to-end, legally oriented framework for handling social media evidence.

To realize this design, this study proposes a blockchain-based forensic framework for OSINT evidence collection and user identification. The framework integrates established digital forensics standards with blockchain-supported notarization and timestamping mechanisms to ensure the integrity, authenticity, and traceability of collected intelligence across various social media and online platforms.

2. Related Work

2.1. Digital Evidence Standards and Challenges in OSINT

To ensure the rigor, consistency, and reliability of forensic procedures, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has developed a comprehensive series of standards related to this field. ISO/IEC 27037 provides essential guidelines for managing the digital-evidence lifecycle [4], offering detailed instructions for identification, collection, acquisition, and preservation. Its primary objective is to preserve evidence integrity from the outset and to prevent contamination caused by improper handling. ISO/IEC 27041:2015 builds on this foundation by emphasizing the evaluation of the suitability and effectiveness of forensic methodologies and tools [6]. ISO/IEC 27042:2015 focuses on the analysis and interpretation of digital evidence, improving analytical reliability and the consistency of results [7]. Furthermore, ISO/IEC 27043:2015 defines overarching principles and an integrated procedural framework for digital-evidence investigations, encompassing the entire process from incident response and evidence management to final analytical reporting [5]. Collectively, these standards provide a systematic foundation for digital-forensics activities, particularly in cases involving computers, mobile devices, and storage media.

While these ISO/IEC standards have been widely adopted in traditional digital forensics environments, their applicability to open-source intelligence remains limited. Evidence obtained from social media platforms is typically collected in the form of screenshots or captured web content, which presents significant challenges in judicial evaluation. Courts must determine whether such evidence truly originates from the platform or has been modified. Unlike evidence stored on local devices, online information is highly volatile and subject to platform updates, user-side changes, and remote deletions. These characteristics complicate the preservation and verification of evidence. As open-source intelligence becomes an increasingly important component of digital investigations, establishing reliable mechanisms to ensure the authenticity and credibility of OSINT evidence has become a pressing issue for both forensic practice and judicial proceedings.

2.2. Judicial Practices and Admissibility of OSINT Evidence

In United States courts, the admissibility of open-source intelligence is primarily governed by Rule 901 of the Federal Rules of Evidence, entitled Authenticating or Identifying Evidence [8]. Under this rule, the proponent bears the burden of demonstrating that the offered evidence is what it is claimed to be. The most reliable way to meet this standard is to prepare a comprehensive digital forensics collection report that documents cryptographic hash values, source URLs, precise timestamps, and the identity of the personnel involved in the acquisition process. A broad corpus of judicial literature indicates that courts are increasingly relying on open-source intelligence, particularly social media content, in both criminal and civil proceedings [9,10,11,12].

One of the earliest and most influential decisions, Lorraine v. Markel American Insurance Company (2007) [12,13], established a five-factor framework for authenticating electronically stored information. The ruling emphasized the importance of collection integrity, metadata verification, authorship attribution, and complete procedural documentation. Subsequent rulings continued to reinforce methodological rigor. In Capitol Records v. Thomas Rasset (2011) [12,14], the court held that electronically stored information-derived evidence must be reproducible, independently verifiable, and supported by disclosures regarding tool limitations. In People v. Price (2015) [15], a New York appellate court ruled that Facebook screenshots were inadmissible because they were captured eighteen months after the alleged event, and neither authorship nor authenticity could be demonstrated to satisfy Rule 901. In United States v. Farrad (2017) [12,16], the court addressed the authentication of social media evidence collected through open-source intelligence techniques and clarified that screenshots may be admissible only when adequately authenticated. The court required the proponent to explain how the content was accessed, what tools were used, the steps taken to preserve data integrity, and any methodological limitations that might affect reliability [12]. These requirements highlight the importance of transparent acquisition procedures and robust verification practices when collecting social media evidence.

Civil proceedings have reached similar conclusions. In Montanez v. Future Vision Brain Bank (2021) [12], the court scrutinized OSINT-based evidence under principles of authenticity, chain of custody, reliability, and proportionality. This case showed that when the collection methodology lacks clarity or sufficient documentation, opposing parties may request forensic examination of the investigator’s device to verify data integrity and the reliability of the acquisition process. Consistent with this trend, many judicial decisions from both civil and criminal contexts affirm that social media evidence is not automatically admissible [17]. Courts frequently dismiss digital content that lacks proper authentication, sufficient metadata, or a verifiable chain of custody. Because social media posts can be easily modified, deleted, or removed from their original context, judges routinely insist on reliable methods for preserving the original content, proving authorship, and documenting the forensic steps taken during collection. Numerous rulings involving fraud claims, personal injury disputes, and criminal investigations show that improperly collected social media evidence is susceptible to challenges related to authorship, manipulation, or incompleteness. These patterns indicate that without rigorous authentication procedures, metadata preservation, and chain-of-custody documentation, social media evidence may be ruled inadmissible [17].

Case law from multiple jurisdictions further illustrates the risks associated with improper handling of open-source intelligence. In Canada, the ruling in R v. Hamdan (2017) [12,18] criticized investigators for relying on basic screenshot tools that did not record metadata or generate hash values, concluding that such practices weaken evidentiary reliability. A related Canadian decision, Regina v. Othman Ayed Hamdan, emphasized that open-source intelligence cannot transition from raw intelligence into admissible evidence without rigorous digital forensic procedures, including metadata extraction, cryptographic verification, and comprehensive chain-of-custody documentation. Similar considerations appear in Taiwan Supreme Court Judgment Number 320 (2023) [19], where the court held that when original digital data cannot be produced, substitute evidence such as screenshots is admissible only when supported by reliable verification methods demonstrating consistency with the original information.

These judicial decisions show that the admissibility of open-source intelligence depends not on the type of evidence but on how it is collected, authenticated, preserved, and documented. Although courts frequently admit social media evidence when proper procedures are followed, many cases demonstrate exclusion due to procedural weaknesses such as unverifiable screenshots, missing metadata, inconsistent timestamps, or insufficient documentation. These findings underscore the importance of standardized and forensic-grade OSINT workflows.

2.3. Technical Challenges in OSINT Evidence Collection and Identification

Beyond judicial case law, recent academic studies also acknowledge that the increasing reliance on open-source intelligence has created an urgent need for standardized practices in OSINT evidence collection and identification. Basumatary et al. [20] conducted a holistic review of social media forensics and identified three major admissibility challenges: integrity, data provenance, and probative value. Integrity concerns arise because social media content can be easily fabricated through the use of fake profiles or unauthorized account manipulation, making it difficult to establish that the collected data has not been altered. Issues of data provenance further complicate admissibility, as courts require clear traceability of ownership, custody, and modification history; however, provenance management in social media environments remains underdeveloped. Probative value also depends heavily on metadata such as timestamps, geolocation information, and modification history, which conventional web crawling or device-based extraction tools often fail to capture. These findings reinforce that without consistent procedures for metadata extraction, authenticity assessment, and chain-of-custody documentation, social media evidence may lack the reliability required for legal acceptance.

Gupta et al. [10] also examined methods for recovering digital traces from social media platforms and identified two central challenges. The first is the absence of a standardized methodology tailored for social media forensics, since existing frameworks do not address platform-specific constraints. The second is the lack of specialized tools capable of integrating social media artifacts into traditional forensic workflows, as most conventional tools cannot effectively process social media data. These limitations highlight the continued need for dedicated methodologies and tools that support reliable social media forensic analysis.

To address such challenges, several studies propose technical frameworks to support forensic OSINT workflows. Vidya et al. [21] introduced a system with acquisition and analysis functionalities that can crawl websites, preserve digital objects, and generate reports for both acquisition and analysis. Although this approach offers strong webpage archiving capabilities, it often collects excessive amounts of irrelevant data when applied to social media platforms, which makes it difficult for investigators to reconstruct case-relevant narratives. Greco et al. [22] proposed a certification framework based on a controlled browser operated by a certification authority to capture screenshots with comprehensive metadata. This approach enhances integrity but faces practical restrictions in real investigations because social media platforms frequently limit content access through privacy controls that require authenticated sessions.

These limitations suggest that although existing automated frameworks offer valuable features, they are insufficient for practical use in real-world criminal investigation environments. Investigators often work with devices seized at the crime scene that are already logged into the suspect’s social media accounts, and they must preserve this authenticated environment without altering the original digital state of the device. In other situations, investigators may need to obtain OSINT evidence from an office environment rather than from a suspect’s device, which further underscores the need for a consistent, user-friendly, and operationally flexible tool that supports frontline personnel in both field-based and office-based OSINT acquisition tasks. In addition, many automated collection architectures generate large volumes of irrelevant social media data that still require manual examination to determine evidentiary value. This creates a significant analytical burden for investigators and may delay urgent investigations. Excessive automation without effective relevance filtering does not necessarily improve operational efficiency and can increase the workload for personnel in real criminal cases.

2.4. Blockchain Applications in Judicial Evidence Preservation and OSINT

Blockchain technology has emerged as a vital solution for secure data preservation and evidence management, largely due to its decentralized architecture and inherent security characteristics. As noted in [23], blockchain systems exhibit several essential attributes, including decentralization, autonomy, data integrity, immutability, verifiability, fault tolerance, anonymity, auditability, and transparency. Through the use of cryptographic hashing algorithms such as SHA-256 and digital signatures, blockchain ensures high data trustworthiness, preserving integrity and preventing unauthorized alteration.

In practical applications, blockchain technology effectively addresses key challenges in digital evidence preservation, particularly within judicial contexts. For example, Ref. [24] proposed a blockchain-enabled judicial evidence framework that integrates the Interplanetary File System (IPFS). In this model, the IPFS distributed storage system is used to store digital evidence, while blockchain records and secures the corresponding hash values and transactional metadata. This integration enhances the security, authenticity, and integrity of judicial evidence. Similarly, Ref. [25] demonstrated that combining blockchain with cloud-storage environments through distributed-ledger mechanisms and Provable Data Possession (PDP) protocols can ensure the long-term credibility, integrity, and accessibility of electronic records, providing a reliable foundation for sustainable evidence management. To clearly distinguish the contributions of our work, Table 1 provides a comparative analysis of this study against these aforementioned blockchain-based digital evidence preservation approaches.

Table 1.

Comparison of this study with other blockchain-based digital evidence preservation approaches.

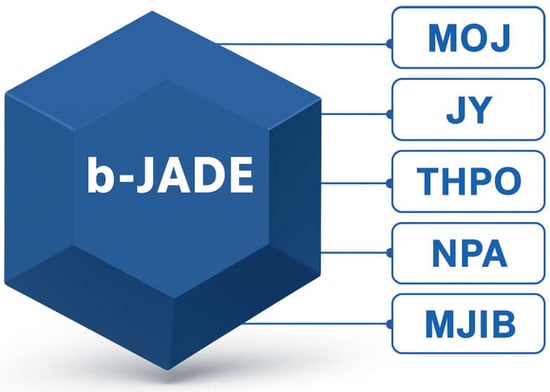

To strengthen digital transformation and improve data integrity in the judicial sector, Taiwan established the Blockchain-applied Judicial Alliance for Digital Era (b-JADE) in 2022 [26]. The consortium blockchain was jointly developed by five founding institutions in Taiwan: the Ministry of Justice (MOJ), Judicial Yuan (JY), Taiwan High Prosecutors Office (THPO), National Police Agency (NPA), and Ministry of Justice Investigation Bureau (MJIB) as shown in Figure 1. The b-JADE infrastructure is based on the Hyperledger Fabric framework and employs a permissioned blockchain architecture that requires authorized participation.

Figure 1.

Blockchain-applied Judicial Alliance for Digital Era.

Operationally, once digital evidence is collected, the system automatically generates a cryptographic hash of the file. The hash value, along with relevant case information, timestamps, and metadata, is encapsulated into a transaction and uploaded to the blockchain for notarization. Each transaction must be endorsed by validation nodes, which are independently managed by consortium members, through a consensus algorithm. After consensus is reached, the transaction is permanently recorded on the shared ledger [27].

Building on these implementations, blockchain technology offers significant advantages when applied to OSINT evidence collection. By generating cryptographic hashes and recording OSINT data on-chain at the time of acquisition, the proposed framework ensures immutability, verifiability, and a tamper-evident record. This real-time notarization mitigates risks associated with data volatility, unauthorized modification, or deletion, thereby improving the evidential reliability and legal admissibility of OSINT in judicial proceedings.

While this study focuses on the integrity and preservation of OSINT data, recent advancements in 2025 have significantly expanded the scope of blockchain forensics, particularly in attribution and fraud detection. Emerging research has demonstrated the efficacy of AI-enhanced models and dynamic graph neural networks (GNNs) for identifying illicit activities on public ledgers. For instance, recent studies such as Sheng et al. (2025) [28] and Tian et al. (2025) [29] have proposed novel architectures like Dynamic Feature Fusion and DiT-SGCR (Directed Temporal Structural Representation), which integrate global graph structures with local semantic features to detect sophisticated fraud patterns in real-time. Similarly, advancements in large-scale data processing presented in [30,31] leverage dynamic graph-based approaches to analyze transaction flows with greater granularity, while [32] highlights the potential of combining machine learning with massive blockchain datasets to trace complex cybercriminal behaviors. Although our framework primarily targets the preservation of social media evidence rather than on-chain financial fraud detection, these advanced analytical methods offer a complementary perspective. They suggest that future forensic frameworks could integrate such AI-driven attribution models to further correlate OSINT findings with on-chain transactional evidence, thereby strengthening the link between digital identities and real-world actors.

2.5. Social Network User Identification

Although blockchain-based solutions ensure the immutability, verifiability, and tamper-evident preservation of OSINT data, they do not inherently reveal the real-world identities of account holders. Even when digital evidence is securely notarized on-chain, identifying the individual behind a social media account remains one of the most challenging tasks in forensic investigations. Solving this problem requires systematic strategies that integrate multiple sources of user-generated data and behavioral indicators to enable probabilistic or deterministic inference of user identities. Existing user-identification techniques on social networks can generally be divided into two main categories: profile-based and network-structure-based approaches.

2.5.1. Profile-Based User Identification

User profile information consists of data voluntarily provided or selected during social-network registration, such as usernames, gender, birth dates, and other personal attributes that are publicly available online. Prior research has shown considerable similarity in user-profile features across different social networks, revealing a degree of cross-platform consistency that can be exploited for user identification.

Zafarani et al. [33] were among the earliest to propose a cross-platform identification approach by comparing usernames across distinct social-networking sites. Wang et al. [34] extracted alphanumeric and date-related patterns from usernames to improve matching accuracy. Li et al. [35] analyzed variations in username-selection behaviors across networks and applied machine-learning algorithms to detect accounts likely belonging to the same user. Motoyama et al. [36] crawled and analyzed user profiles from multiple platforms, representing them as keyword sets and calculating similarity scores between these sets to estimate account correspondence. Raad et al. [37] designed a matching method using the Friend-of-a-Friend (FOAF) ontology, converting profile data into standardized FOAF descriptors and applying decision algorithms to quantify inter-account similarity. Iofciu [38] introduced a subjective-weighting model that combined usernames and user-generated tags to compute weighted similarity, whereas Ye et al. [39] adopted an objective-weighting scheme derived from subjective evaluations to measure attribute-based similarity among profiles.

2.5.2. Network-Structure-Based User Identification

Network-based identification relies on the topology of social connections, particularly friendship relations, to match users by analyzing node-similarity metrics. The interaction networks generated by user activities often exhibit structural symmetry across different social platforms. Because friendship networks tend to remain stable over time, cross-platform user identification can be achieved by examining overlaps among mutual acquaintances detected on multiple networks.

Narayanan et al. [40] first demonstrated successful identification using network-topology information alone. Building on this foundation, Cui et al. [41] integrated user-profile data with graph-similarity measures to link accounts between email-based networks and Facebook’s social-network structure.

Both profile-based and network-based methods have inherent limitations when used independently, particularly in criminal investigations where user data are sparse, fragmented, or incomplete. Combining the two approaches allows investigators to leverage complementary strengths, resulting in more reliable and higher-confidence identification. This integrated strategy provides a robust analytical framework for associating OSINT-derived digital traces with real-world identities while maintaining the integrity, traceability, and admissibility of the corresponding evidence.

3. Proposed OSINT Evidence Collection Methodology

To address these challenges, this study establishes a systematic and legally compliant framework for the collection and preservation of OSINT evidence. The framework is developed in accordance with international digital-forensics standards, including ISO/IEC 27037, 27041, 27042, and 27043, which collectively define procedures for the identification, acquisition, authentication, preservation, and validation of digital evidence. The proposed methodology follows this structure to ensure procedural clarity and maintain consistency with established forensic best practices.

While ISO/IEC 27037 formally defines four primary stages of digital evidence handling (identification, collection, acquisition, and preservation), this study extends the framework by incorporating the authentication and validation concepts outlined in ISO/IEC 27041 and ISO/IEC 27043. This enhancement ensures procedural transparency, auditability, and legal defensibility throughout the entire OSINT investigation workflow, aligning the proposed framework with the most recent international standards for end-to-end digital forensic processes.

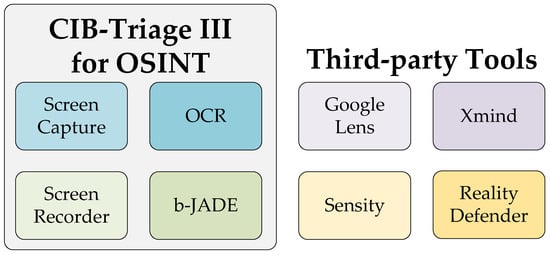

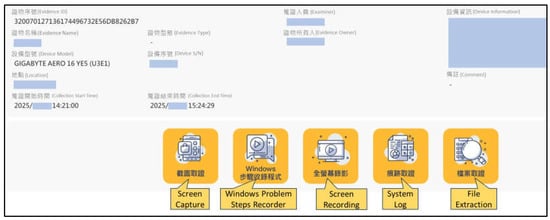

To realize this framework in practice, a digital-evidence collection system named CIB-Triage III (Figure 2) was developed. The system operates the framework by supporting modular acquisition, metadata extraction, hashing, and verification within a unified workflow. It enables evidence collection from mobile devices, computers, and cloud platforms, and its automated processes minimize human intervention, thereby reducing the risk of contamination or tampering.

Figure 2.

(a) CIB-Triage III integrates evidence collection tools for computers, mobile devices, and cloud data, along with mechanisms for on-chain evidence registration and verification. (b) The screenshot and recording functions within the digital forensic toolkit allow investigators to capture visual data from social networking platforms as digital evidence. (c) Each captured image is automatically annotated with metadata, including the timestamp and file size, and a cryptographic hash value is generated to verify the integrity and authenticity of the evidence.

Unlike traditional digital forensics, OSINT data are typically obtained from open networks and social media platforms rather than devices owned by suspects. As such, linking online evidence to a specific individual in the real world presents a significant challenge. Establishing this connection requires a combination of behavioral analysis, profile correlation, and network structure assessment to verify that the collected information accurately represents the activities of the identified person. This verification process is essential for ensuring that OSINT evidence is both authentic and attributable before it is formally acquired and preserved.

Within the context of OSINT, the Evidence Identification Phase differs from traditional digital-forensics practice. Although ISO/IEC 27037 defines identification as the process of recognizing potential sources of digital evidence, OSINT extends this phase to include the evaluation of publicly available materials distributed across social media and online ecosystems. This phase focuses on identifying and validating OSINT data that is relevant to the specific investigation target. By examining contextual relationships, user interactions, and data provenance, the process determines whether the collected online content can be legitimately associated with the subject under investigation. This refined identification phase ensures that subsequent acquisition, authentication, preservation, and validation procedures are performed on evidence that is both relevant and verifiably connected to the intended individual or incident.

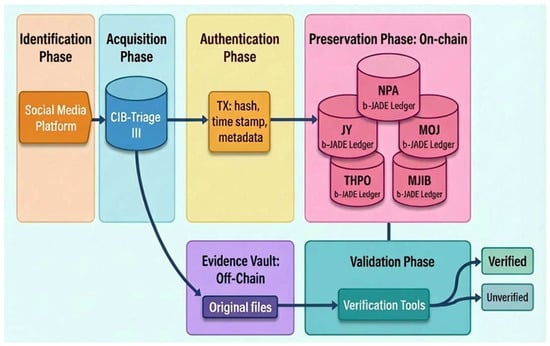

After OSINT authenticity has been verified and the social media account has been credibly linked to a real-world individual, the corresponding evidentiary data are collected using CIB-Triage III. This system performs modular acquisition of verified OSINT artifacts from online platforms, ensuring that each item is accompanied by metadata, precise timestamps, and cryptographic hash values (e.g., SHA-256, acquisition timestamp, collector ID, content length) to maintain data integrity and verifiability. The evidence bytes remain off-chain in the evidence vault. The verified and authenticated evidence, along with its metadata and hash values, is subsequently uploaded to b-JADE for blockchain notarization. By leveraging the decentralized and immutable architecture of blockchain, the framework preserves authoritative evidence states, enables immediate verification of authenticity, and mitigates risks associated with the volatility of online content. Integration with the Police Digital Evidence Chain further enhances inter-agency trust and procedural transparency, strengthening the legal defensibility of OSINT-derived evidence in judicial and administrative proceedings.

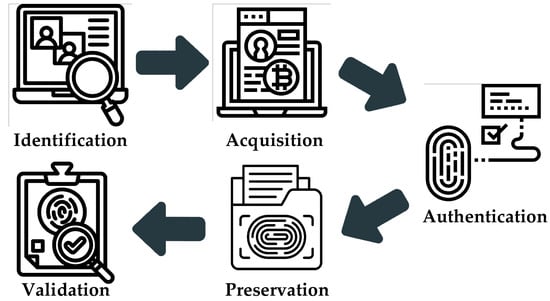

The following sections provide a detailed explanation of the proposed framework, elaborating on the identification, acquisition, authentication, preservation, and validation phases (Figure 3). Each phase is discussed in terms of its objectives, procedures, and mechanisms, illustrating how the framework systematically implements OSINT evidence management in a transparent and legally defensible manner. To further enhance clarity, Figure 4 visualizes the complete data flow from OSINT collection through identity correlation, off-chain storage, and on-chain notarization. This architectural illustration highlights the interaction between CIB-Triage III and b-JADE, the separation of trust boundaries, and the integration between on-chain and off-chain components, providing a clear understanding of how evidence moves through the system.

Figure 3.

Operational workflow of the proposed OSINT evidence collection framework.

Figure 4.

System architecture of the proposed OSINT evidence framework.

3.1. Identification Phase

3.1.1. Platform and Tool Preparation

The platform and tool preparation sub-phase ensures that all technical resources are ready and that pre-existing intelligence is systematically organized, establishing a solid foundation for subsequent investigative activities. All hardware and software required for evidence collection are configured and validated according to the specific objectives of the investigation. Core tools include screen-capture applications, Optical Character Recognition (OCR) utilities for converting text embedded in images into machine-readable formats, and analytical software such as mind-mapping tools used to conduct relational analysis and visualize complex intelligence structures.

Integrated forensic platforms, such as CIB-Triage III, further enhance operational rigor by enabling continuous recording of digital interactions, automatic extraction of textual content, and secure computation and storage of cryptographic hash values alongside essential metadata, including timestamps and source identifiers. Collected evidence can be uploaded either immediately or in batches to b-JADE, leveraging blockchain’s decentralized, immutable, and auditable characteristics to ensure authenticity and integrity across the entire chain of custody. By formalizing these preparatory procedures and aligning them with forensic and legal standards, the framework enhances both operational efficiency and the reliability of the resulting evidence.

3.1.2. Target Background and Relevant Information

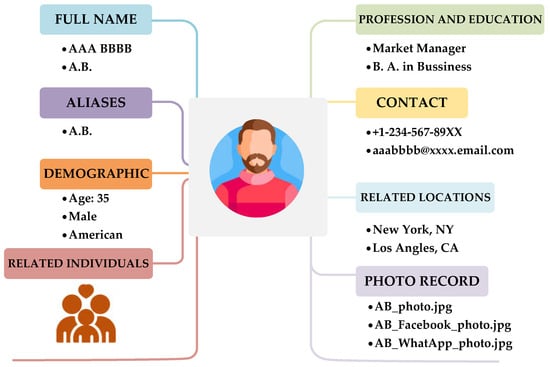

Before initiating active OSINT collection, investigators systematically compile comprehensive background information on the target of the investigation. This preparatory step ensures that subsequent data acquisition and analysis are conducted with precision, legality, and a clear understanding of the context. The compiled information includes personal identifiers such as full names, known aliases, demographic characteristics, professional and educational backgrounds, contact details, frequently visited locations, and photographic records.

The data compilation also extends to individuals closely associated with the target, including family members, colleagues, and other relevant affiliates, along with any supporting documentation, such as news articles, social media posts, or public records. This structured dataset serves as a critical foundation for subsequent stages of OSINT investigation, facilitating correlation, behavioral analysis, and identity verification. By conducting this process under standardized forensic and legal protocols, investigators ensure that all preparatory activities are performed within a methodologically sound and legally defensible framework.

3.1.3. User Identity Correlation Phase

The User Identity Correlation Phase focuses on verifying and correlating online identities with real-world individuals through a progressive multifactor comparison mechanism. The process begins with surface-level indicators available on social media and gradually advances toward more detailed and personalized information that provides stronger corroboration. This layered approach ensures that identity attribution proceeds from low-risk, easily observable factors to high-confidence, evidence-based verification, thereby enhancing both accuracy and legal defensibility.

By integrating multiple identification criteria in a structured sequence, OSINT data are cross-validated across diverse sources to minimize misidentification risks and strengthen investigative precision. The verification process consists of four levels, each increasing in depth and reliability, building upon the previous one.

- Identical Account or Name Comparison

This method represents the entry point of the analysis, identifying potential users based on identical or highly similar usernames across multiple platforms. For example, if a person uses the account name A1 on platform Alpha and a nearly identical username on platform Beta, there is a strong probability that both accounts are operated by the same individual. The reliability of this approach increases with the uniqueness or rarity of the username.

- 2.

- Relationship Network Comparison

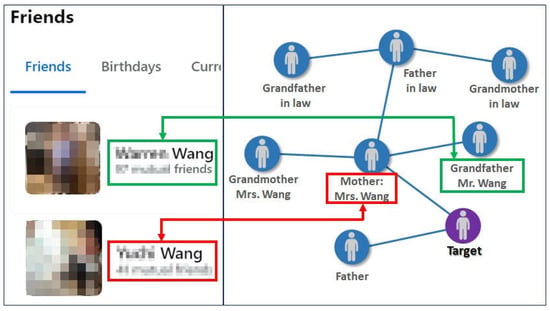

The next level examines social relationships and connections between followers and friends within online platforms. If user A is known to have siblings named Alpha and Beta, and those accounts appear in the friend list of a particular Facebook profile, it can be reasonably inferred that the profile is likely controlled by user A. This method leverages stable interpersonal ties as mid-level corroborative evidence, enhancing confidence in user identification.

- 3.

- Special Event Comparison

At this stage, the analysis incorporates identifiable events with distinct temporal markers such as birthdays or anniversaries. For instance, if user A′s birthday is known to be March 3 and a Facebook account receives numerous birthday messages precisely on that date, the likelihood that the account belongs to user A increases significantly. Event-based temporal correlation thus provides contextual validation linking digital activity with real-world timelines.

- 4.

- Individualized Content Comparison

The final and most in-depth layer focuses on highly personalized information voluntarily or inadvertently disclosed online. Examples include photographs with recognizable locations, visible vehicle license plates, or images related to banks. If user A posts a photograph that clearly displays identifiable features such as a car license plate or a distinctive environment, it provides compelling corroborative evidence that the account is indeed operated by that individual. This method yields the highest level of confidence, provided that the evidence is obtained and preserved in compliance with legal and forensic standards.

3.2. Acquisition Phase

The Acquisition Phase translates the outputs of the Identification Phase into actionable evidence collection. Building on the previously established verified OSINT targets and sources, this stage focuses on the controlled acquisition of relevant data while maintaining strict forensic soundness. All collection activities are conducted in accordance with ISO/IEC 27037 guidelines to ensure that each acquired item retains its authenticity, integrity, and traceability throughout the process.

3.2.1. Collection

The Collection sub-phase involves the systematic acquisition of publicly available data that have been pre-validated as relevant to the investigation. Data sources include major social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram, and X), instant messaging applications, online forums, blogs, and cryptocurrency exchanges. To preserve authenticity and integrity, investigators use digital screenshots, continuous screen recording, and other non-intrusive methods that do not alter the original data.

Key elements of interest include usernames, account identifiers, profile attributes, user-generated content, social relationships (friends, followers, commenters), temporally defined activities (birthday posts, event participation), and individualized digital artifacts such as images, videos, vehicle license plates, and geolocation data. Formalizing and standardizing these procedures ensures reproducibility, completeness, and compliance with evidentiary requirements.

3.2.2. Analysis

After collection, the acquired data are organized and filtered to remove redundancy and irrelevant information. The analysis aims to extract critical, individualized intelligence components that contribute to establishing evidential value. Each dataset is examined for authenticity, integrity, and temporal accuracy before being prepared for authentication and preservation.

Analytical tools assist this process: Google Lens can detect duplicate images across platforms, while deep-fake-detection tools such as Sensity [42] and Reality Defender [43] verify content authenticity. Captured images are processed with OCR software to facilitate textual indexing, and visualization applications such as Xmind [44] help investigators map and understand complex relationships within the collected intelligence.

3.3. Authentication Phase

The authentication phase ensures that all OSINT evidence collected in the acquisition stage is genuine, unaltered, and traceable to its original source. This phase verifies the integrity and authenticity of each data item by applying forensic validation techniques and establishing a clear chain of custody. The authentication process is particularly critical for OSINT because the information originates from open and dynamic online environments, where digital content can be modified, deleted, or fabricated without notice.

Verification begins by confirming the provenance and consistency of each evidence item. Metadata such as timestamps, URLs, device information, and digital signatures are analyzed to confirm their coherence with the original collection records. Cryptographic hash values generated during acquisition are recalculated and compared to the originals to verify that no alterations occurred. Any discrepancy triggers an integrity review, and the affected data are either revalidated or excluded from further evidentiary use.

To further enhance reliability, blockchain-based notarization mechanisms such as b-JADE are utilized to record hash values and essential metadata on a decentralized ledger. This ensures long-term immutability and auditability, allowing investigators and judicial authorities to independently verify the authenticity of evidence at any point in time. Additionally, all authentication activities are documented within the forensic management system to ensure procedural transparency and compliance with ISO/IEC 27001:2022 [45] and 27002:2022 [46] requirements.

Through this systematic verification process, the framework guarantees that every authenticated OSINT artifact meets the evidentiary standards of integrity, originality, and reproducibility required for legal admissibility.

3.4. Preservation

The Preservation Phase focuses on maintaining the integrity, authenticity, and continuity of OSINT evidence after authentication. To reinforce evidentiary reliability, the proposed framework integrates the preservation process directly into the CIB-Triage III platform. This integration enables automated computation of unique cryptographic hash values for each digital artifact, ensuring that all evidence is systematically verified and securely recorded. Immutable hash records serve as digital fingerprints, preventing post-collection modification and maintaining an unbroken chain of custody.

By embedding OSINT preservation procedures into an established forensic platform, the framework extends conventional digital-evidence management practices. It provides investigators with a standardized, reproducible, and legally defensible methodology for long-term intelligence preservation, fully compliant with the principles outlined in ISO/IEC 27042 and 27043.

3.5. Validation Phase

The Validation Phase consolidates and formalizes all outputs from the preceding collection, analysis, and identification stages into a structured, auditable, and transparent forensic record. Within this phase, all investigative findings, analytical reasoning, and operational methodologies are systematically documented to ensure reproducibility, traceability, and evidentiary validity.

Following the principles outlined in the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations [47], the framework structures the final report to include:

- Clearly defined investigative objectives;

- Comprehensive description of the methodology, including procedural steps and adherence to legal and forensic standards;

- A chronological account of activities conducted during collection, analysis, and identification;

- Detailed documentation of data sources and provenance to maintain transparency and traceability;

- Acknowledgment of uncertainties, data gaps, or limitations encountered during the investigation; and

- Evidence-based findings supported by actionable recommendations.

Furthermore, the framework incorporates visual analytic representations, such as network diagrams, charts, and relational maps, to illustrate complex interconnections and facilitate the interpretation of analytical conclusions. By formalizing the report generation process within this structure, the Validation Phase ensures that OSINT investigations are systematic, transparent, and legally defensible, while also providing a replicable methodology for knowledge transfer and future investigative or judicial use.

3.6. Legal Admissibility and Compliance Mapping

This section maps the OSINT lifecycle employed in this study, which consists of Identification, Acquisition, Authentication, Preservation, and Validation, to the evidentiary requirements of the United States Federal Rules of Evidence (FRE). This alignment ensures that each stage of the proposed framework satisfies specific legal thresholds required for admissibility:

- Authenticity (FRE 901): The requirement of Rule 901(a) is satisfied through a documented, repeatable process. The system captures comprehensive logs, precise timestamps, and the SHA-256 hash of the original data at the moment of capture. This digest, along with minimal metadata, is immediately notarized on the b-JADE consortium ledger to freeze the state of evidence.

- Self-Authentication (FRE 902): Requirements under Rules 902(13) and 902(14) regarding certified records of generated electronic information are met through a dual-verification mechanism. This involves a custodian’s certificate describing the system’s operation and a verifiable match between the hash of the preserved object in the off-chain vault and the immutable digest recorded on-chain (referenced by transaction ID).

- Best Evidence Rule (FRE 1001–1003): The framework complies with the “Best Evidence” principle by preserving the original binary data in a Write-Once-Read-Many (WORM) evidence vault. It allows for the production of the original or a bit-for-bit duplicate, with integrity demonstrated through deterministic re-hashing and on-chain proof verification.

Through these mechanisms, our framework ensures that OSINT evidence collected through the proposed lifecycle meets the legal standards for authentication, integrity, provenance, and evidentiary sufficiency required in judicial proceedings. By embedding admissibility considerations directly into the forensic workflow, the system strengthens the reliability and defensibility of OSINT evidence in both investigative and courtroom contexts.

4. Implementation of the OSINT Evidence Collection Framework

This section presents a prototype implementation of the proposed framework that demonstrates feasibility and workflow integration; large-scale, real-world deployment and evaluation are left to future work. The implementation follows the five sequential phases established in Section 3, namely identification, acquisition, authentication, preservation, and validation. Each phase has been modularized into dedicated software components and operational procedures to ensure that the investigative workflow remains systematic, legally compliant, and forensically verifiable.

Given its large user base, Facebook [1] is used here as a case study platform for implementing and demonstrating the pipeline. However, the system architecture is designed to be applicable to other OSINT sources such as X (Twitter), Instagram, and additional social network platforms. This platform, once fully developed, can potentially serve as a foundation for testing and validating the proposed framework. The system architecture is designed to be extensible and can be expanded in future versions to incorporate other OSINT sources.

The implementation emphasizes procedural rigor and reproducibility while integrating cryptographic verification and blockchain-based preservation mechanisms to ensure the integrity of digital evidence throughout the forensic process.

4.1. Identification Phase

In the identification phase, investigators prepare the technical environment and compile relevant background information on the investigative target. This preparation ensures that all required tools and intelligence resources are properly organized before active evidence collection begins. The identification phase, therefore, serves as the foundation of the entire OSINT workflow, linking investigative planning with the operational procedures described in subsequent stages.

4.1.1. Platform and Tools Preparation

The platform and tools preparation phase ensures that investigators are equipped with the essential technical resources, software platforms, and baseline intelligence required to perform efficient and legally compliant OSINT evidence collection. All tools incorporated into the framework correspond to the five functional phases of the OSINT evidence collection process, namely identification, acquisition, authentication, preservation, and validation. Excluding the validation phase, seven primary tools have been implemented to support the core operations of the system. These tools establish a standardized and reproducible technical environment that aligns with the principles of ISO/IEC 27037, supporting accurate, transparent, and legally defensible OSINT operations within a forensic context.

Among these tools, CIB-Triage III serves as the central platform, providing comprehensive functionality for screen capture, continuous screen recording, Optical Character Recognition (OCR), and blockchain-based preservation through b-JADE. The Google Lens utility, accessible directly via the Chrome browser, enables rapid image correlation and cross-platform verification. Xmind (version 26.01) facilitates structured visualization and relationship mapping, while deepfake detection tools such as Sensity and Reality Defender are employed to verify the authenticity of visual content (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Tools utilized in the implementation of the OSINT evidence collection framework.

4.1.2. Target Background and Relevant Information

During this stage, investigators compile comprehensive background and familial information concerning the target. Police information systems are accessed to retrieve a list of the target’s relatives, including the collection of fundamental biographical data such as names, photographs, and dates of birth for all individuals within the fourth-degree kinship range. Public academic databases such as Google Scholar, along with advanced search queries using filters like “site:edu.xx” or “site:ac.xx,” are also utilized to identify the target’s academic background, research expertise, and potential classmates or collaborators.

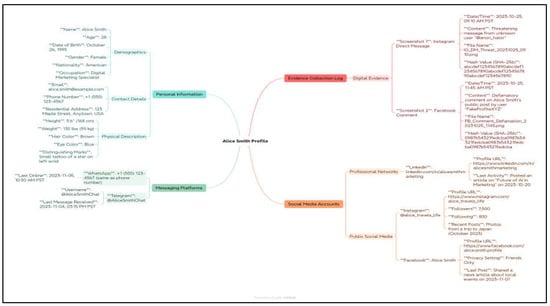

Additional data sources, such as stop and search records, co-travel information from immigration databases, and visitation logs from detention facilities, are examined to uncover the target’s close associates or possible accomplices. All gathered intelligence is subsequently organized with Xmind to construct a comprehensive mind map of the target (Figure 6), providing a visual overview that facilitates subsequent data analysis and operational assessment.

Figure 6.

Map of target basic and relative information.

4.1.3. User Identity Correlation Phase

A multi-factor verification approach is employed to confirm account attribution. Relying on a single factor, such as a matching photograph, provides limited confidence due to the potential for impersonation or coincidental similarity. To address this limitation, the verification process follows a probabilistic reasoning model inspired by Bayesian theory. Each independent indicator contributes to the posterior probability of correct attribution according to the formula:

where represents the probability that the account truly belongs to the target given N independent corroborating factors . The constant k is a normalization factor that ensures the total probability across all potential account candidates equals one. In practical applications, investigators are primarily concerned with relative probabilities rather than the explicit value of k, since the normalization term does not affect comparative attribution results.

In this operational framework, the specific weights are assigned according to the evidentiary strength of each category. For example, ‘Individualized Content Comparison’ (high weight) receives a substantially higher weight than ‘Identical Account Name’ (low weight) because the likelihood of accidental duplication is far lower for physical identifiers such as license plates or geolocated imagery than for usernames. This hierarchical weighting ensures that identity correlation is grounded in high-confidence indicators prior to final attribution.

As additional consistent evidence is incorporated, such as overlapping friend networks, recurring event timestamps, and unique identifiers, the cumulative probability of accurate attribution increases multiplicatively. This quantitative framework mirrors fingerprint identification principles, in which each new point of correspondence raises the overall confidence level and significantly reduces the likelihood of false attribution.

To operationalize this framework, investigators apply the four OSINT evidence classification methods introduced in Section 3.1.3. Representative examples are shown in Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 and are described as follows:

Figure 7.

LINE and Facebook accounts using the same username “PKNEVXXXXXE,” demonstrating cross-platform identity correlation.

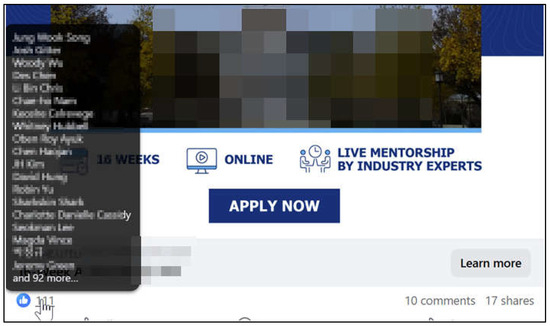

Figure 8.

Facebook “Like” interaction records illustrating relationship mapping through engagement patterns.

Figure 9.

Comparison between the target’s social media connections and known family and friend relationships.

Figure 10.

Facebook post containing a special event message “Happy Birthday!”, showing temporal and relational cues useful for identity verification.

Figure 11.

Facebook post displays a car license plate, representing individualized content that supports identity corroboration.

- Identical Account or Name Comparison. Investigators begin by using keywords or names to locate accounts with identical or similar usernames. For instance, Facebook’s search function can identify accounts displaying public profile pictures, posts, and interaction histories. LINE is a messaging and social platform widely used in East Asia, and its functionalities are similar to those of WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. LINE allows account searches using either user IDs or phone numbers. As shown in Figure 7, correlation is strengthened when both platforms use the same account name, such as the username “PKNEVXXXXXE.”

- Special Event Comparison. Posts associated with birthdays, memorials, or anniversaries (Figure 10) often reveal key personal relationships and life events, helping to corroborate identity.

- Individualized Content Comparison. Posts may inadvertently disclose distinctive information such as locations, vehicle license plates, or household environments. Although each element may appear minor, these details become valuable when corroborated with other intelligence (Figure 11).

Once multi-factor identification confirms the actual user of a social media account, investigators then transition back to the Collection sub-phase to conduct broader data acquisition. At this stage, the CIB-Triage III system functions as the core acquisition platform, providing real-time screen capture and continuous recording capabilities. These functionalities support a comprehensive collection of both static and dynamic data across websites, social media platforms, and other publicly accessible sources, ensuring completeness and traceability of collected intelligence. Intelligence directly related to the target, such as check-in records or tagged locations, provides valuable insights into the target’s activities, timeline, and associations. Finally, all information relevant to the investigation is securely preserved through the Preservation sub-phase by recording integrity-protected artifacts, such as hash values, onto the b-JADE blockchain, ensuring long-term traceability and evidentiary admissibility.

4.2. Acquisition Phase

4.2.1. Collection

The Collection sub-phase involves the systematic acquisition of publicly available data that have been pre-validated as relevant to the investigation. The CIB-Triage III system serves as the core acquisition platform, providing real-time screen capture and continuous recording capabilities (Figure 12). To preserve authenticity and integrity, investigators employ digital screenshots, continuous screen recording, and other non-intrusive techniques that do not modify the original data.

Figure 12.

Real-time screen capture and continuous recording are performed using the CIB-Triage III platform.

These functionalities support comprehensive acquisition of both static and dynamic data across websites, social media platforms, and other publicly accessible sources, ensuring completeness and traceability of collected intelligence. By centralizing these operations within a single platform, the framework achieves consistent data-handling procedures that comply with ISO/IEC 27037 guidelines and maintain forensic soundness throughout the acquisition process.

4.2.2. Analysis

After collection, the acquired data are systematically organized, filtered, and verified to remove redundancy and irrelevant information. The analysis aims to extract critical and individualized intelligence components that contribute to establishing evidential value. Each dataset is examined for authenticity, integrity, and temporal accuracy before being prepared for authentication and preservation.

To enhance analytical rigor and efficiency, multiple complementary tools are integrated into the framework:

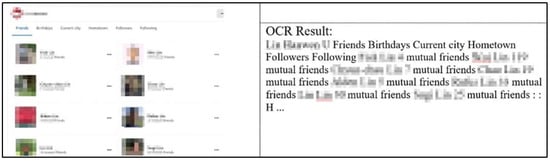

- OCR within CIB-Triage III converts textual content embedded in images into searchable formats, enabling rapid extraction of relevant information from large datasets (Figure 13).

Figure 13. Extraction and analysis of Facebook friend lists using the OCR function within CIB-Triage III.

Figure 13. Extraction and analysis of Facebook friend lists using the OCR function within CIB-Triage III. - Mind-mapping software, such as Xmind, provides structured visualization and relational analysis, allowing investigators to systematically synthesize fragmented intelligence (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Mind mapping of the investigative target and associated relationships created with Xmind.

Figure 14. Mind mapping of the investigative target and associated relationships created with Xmind. - Reverse image search tools, such as Google Lens, enable verification of whether visual content is already publicly available, misappropriated, or altered.

- Deepfake detection platforms, such as Sensity and Reality Defender, are employed to evaluate the authenticity of images and videos, minimizing the risk of incorporating manipulated content into the investigation.

After the analytical process is completed, verified datasets are forwarded to the Authentication Phase, where hash values and metadata are generated to ensure evidentiary integrity and forensic verifiability.

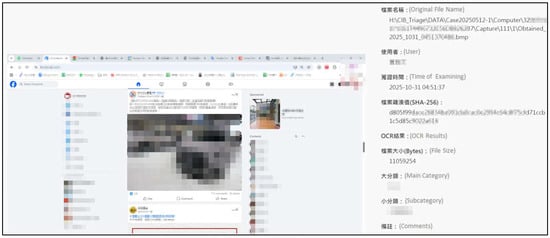

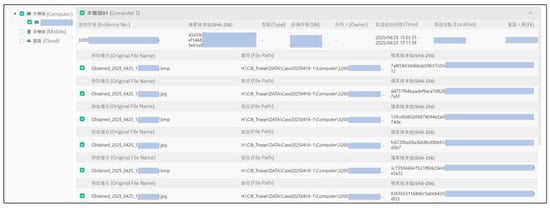

4.3. Authentication and Preservation Phase

In the Authentication Phase, CIB-Triage III (Figure 15) automatically generates cryptographic hash values for all captured screenshots and video recordings. These hash values, together with associated metadata such as timestamps and collector identity, are securely stored in b-JADE (Figure 16). This procedure ensures that each piece of evidence can be independently verified during judicial review and remains tamper-proof throughout its lifecycle.

Figure 15.

Hash value generation and metadata recording are performed within the CIB-Triage III platform.

Figure 16.

Evidence preservation and blockchain-based verification performed through the integration of CIB-Triage III with the b-JADE.

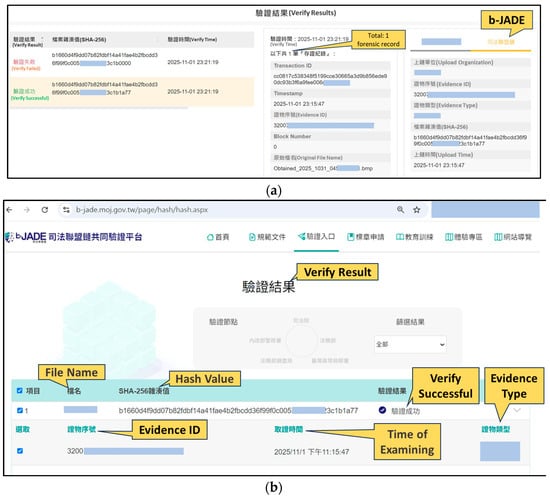

4.4. Validation Phase

This phase is the final operational step of the framework. It consolidates and validates outputs from identification, acquisition, authentication, and preservation. The system performs consistency checks, revalidates evidence integrity, and generates structured exports to support report preparation for judicial or administrative use.

- Data integrity revalidation

The platform rechecks hash values, timestamps, and blockchain notarization identifiers produced during authentication and preservation. Hash records stored in b-JADE are compared with the local evidence registry to confirm that no alterations occurred during storage or transfer (Figure 17).

Figure 17.

Verification of digital evidence integrity on the b-JADE blockchain. (a) Verification performed through the connection between the CIB-Triage III forensic platform and b-JADE. (b) Verification conducted via the b-JADE Common Verification Platform web interface (https://b-jade.moj.gov.tw/page/hash/hash.aspx) (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- 2.

- Procedural traceability review

Operational logs are compiled and linked to their corresponding digital objects. Logs include acquisition timestamps, collector identifiers, analytic actions, and version information. These linkages establish an auditable chain of custody suitable for judicial review.

- 3.

- Reporting support and structured export

Validated findings, metadata, and integrity references are organized into exportable fields aligned with Section 3.5 and the Berkeley Protocol. The framework does not auto-generate the final report. Investigators can directly use exported fields, such as key findings and identity correlation evidence, as well as the associated acquisition and authentication metadata, cryptographic hashes, and blockchain transaction IDs. Additionally, they can appendices that list artifact manifests and hash indexes.

Through these validations and structured outputs, the Validation Phase completes the forensic workflow, ensuring that OSINT evidence managed by CIB-Triage III is verifiable, traceable, and suitable for legal admissibility.

4.5. Performance Evaluation and Scalability Analysis

Social media evidence is characterized by high velocity and volatility, which requires the underlying notarization mechanism to respond rapidly and remain stable under varying workloads. To evaluate whether the proposed blockchain-based framework meets these operational requirements, we conducted a series of performance and scalability experiments focusing on the hash-to-on-chain process in the b-JADE environment.

4.5.1. Experimental Setup and Scenarios

The experiments were performed on VMware ESXi virtual machines equipped with 4 virtual CPUs, 8 GB of RAM, and a 120 GB solid-state drive, running Ubuntu 20.04 and Hyperledger Fabric. The blockchain network was configured with a batch timeout of 2 s, a maximum message count of 500 transactions per block, and an absolute maximum block size of 10 megabytes. These parameters reflect a representative configuration for permissioned blockchain deployments in practical forensic environments.

To evaluate the impact of increasing data volume on system latency, we generated a comprehensive set of hash values and conducted write-latency tests across four batch sizes: 10, 100, 1000, and 10,000 entries. Because Hyperledger Fabric does not explicitly record block-finalization timestamps, the completion time for each test was determined using the header timestamp of the final transaction included in the last confirmed block, which provides millisecond-level precision. To ensure reliability and reduce the influence of outliers, each test scenario was executed 5 times, and the average completion time was used for analysis.

4.5.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

The results summarized in Table 2 demonstrate a clear relationship between batch size and write latency while confirming the operational stability of the system. For small batches of 10 hashes, the average completion time was 42 milliseconds. As the batch size increased to 100 and 1000 hashes, the average latency rose to 2.24 s and 51.25 s, respectively. The largest batch of 10,000 hashes required 555.21 s (approximately 9 min).

Table 2.

Test result for 10 to 10,000 hash values.

These increases in latency reflect the computational overhead inherent to block ordering and validation within a permissioned blockchain network. Nonetheless, the performance remains within acceptable limits for forensic operations. In practical investigative contexts, the ability to notarize thousands of digital artifacts, such as chat logs or image collections, within minutes is sufficient to preserve volatile social media evidence before suspects can alter or delete content. These results demonstrate that the b-JADE infrastructure provides the throughput and stability required for real-world investigative scenarios that demand timely OSINT preservation.

5. Conclusions

This research establishes an integrated digital-forensics framework that transforms OSINT from a loosely organized investigative activity into a legally admissible evidentiary process. By combining standardized identification, controlled acquisition and analysis, cryptographic authentication, and blockchain-based preservation, the proposed model operationalizes the full OSINT lifecycle in accordance with forensic and legal standards.

Through the implementation of the CIB-Triage III prototype, the framework demonstrates that OSINT evidence can be recognized, collected, analyzed, authenticated, and validated within a single coherent workflow. This integration closes the long-standing gap between open-source information gathering and judicially recognized digital evidence. The b-JADE blockchain infrastructure further extends this capability by providing immutable notarization and cross-agency verification, creating an auditable chain of custody that meets the evidentiary requirements of international courts and law enforcement cooperation.

The study’s methodological contribution lies in formalizing a replicable, end-to-end process that aligns the principles of the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations with ISO/IEC 27037 and related standards. Technically, it delivers a prototype that unifies multi-factor identity correlation, integrity verification, and digital preservation within a single forensic platform. Practically, it offers judicial institutions a verifiable path to admit OSINT-derived evidence while maintaining transparency, reproducibility, and ethical compliance.

By consolidating these theoretical, technical, and procedural advances, the framework establishes a new paradigm for OSINT forensics. It provides an actionable model that enhances investigative credibility, strengthens transnational evidentiary reliability, and promotes judicial confidence in the lawful use of open-source intelligence worldwide. Future research should further evaluate whether the deployment of a production-level version of CIB-Triage III can empirically improve the judicial acceptance and evidentiary weight of OSINT in real court proceedings.

While the current framework establishes a robust foundation for data integrity using permissioned blockchains, future iterations will integrate advanced privacy-preserving technologies and intelligent analysis modules. Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) represent a promising direction for privacy-preserving OSINT, enabling investigators to prove the possession or validity of evidence without disclosing sensitive collection methods or source identities on the ledger. Furthermore, as discussed in Section 2.4, incorporating AI-driven anomaly detection, deepfake detection, and dynamic graph analysis will enhance automated identification of manipulated content and fraudulent on-chain behaviors. Integrating these smart and privacy-preserving analytical components within the b-JADE infrastructure represents a natural evolution of the framework, transforming it from a passive preservation mechanism into an active, intelligent forensic ecosystem.

Author Contributions

All authors discussed the content of the manuscript and contributed equally to its preparation. Specifically, H.-W.H. performed the experiments; C.-H.S. and C.-Y.L. designed and supervised the study; H.-Y.T. analyzed the experimental results; and C.-Y.L. assisted in interpreting the results. C.-H.S. and C.-Y.L. reviewed the manuscript, while C.-Y.L. and H.-W.H. drafted the initial version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The CIB-Triage III prototype used in this study is not publicly available due to copyright and intellectual property restrictions. No new datasets were generated or analyzed beyond those incorporated within the framework’s controlled testing environment.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-5, ChatGPT-4o, and Grammarly (version 1.2.198.1762) to assist with text refinement and language editing through human–machine–human iterations. Furthermore, ChatGPT-5 and Freepik were utilized to optimize the visual aesthetics, specifically the color schemes and structural layout, of Figure 1 and Figure 4 based on the original designs. The authors have carefully reviewed and edited all outputs and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Statista. Biggest Social Media Platforms by Users 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- AP News. Capitol Rioters’ Social Media Posts Influencing Sentencings. Available online: https://apnews.com/article/media-prisons-social-media-capitol-siege-sentencing-0a60a821ce19635b70681faf86e6526e (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Insurance Business, UK. Another Fraudulent Insurance Claim Foiled by Social Media. Available online: https://www.insurancebusinessmag.com/uk/news/breaking-news/another-fraudulent-insurance-claim-foiled-by-social-media-193531.aspx (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- ISO/IEC 27037:2012; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Guidelines for Identification, Collection, Acquisition, and Preservation of Digital Evidence. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- ISO/IEC 27043:2015; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Guidelines for the Analysis and Interpretation of Digital Evidence. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO/IEC 27041:2015; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Incident Investigation Principles and Processes. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ISO/IEC 27042:2015; Information Technology—Security Techniques—Guidance on Assuring Suitability and Adequacy of Incident Investigative Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- US Law Rule 901. Authenticating or Identifying Evidence. Available online: https://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/fre/rule_901 (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- CourtListener. (n.d.). Search Results for Courts: All Query: Social Media Evidence. Available online: https://www.courtlistener.com/?type=r&q=social%20media%20evidence&type=r&order_by=score%20desc (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Gupta, K.; Oladimeji, D.; Varol, C.; Rasheed, A.; Shahshidhar, N. A Comprehensive Survey on Artifact Recovery from Social Media Platforms: Approaches and Future Research Directions. Information 2023, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzakis, J. Social Media Evidence Key Factor in Estimated 500,000 Litigation Cases Last Year. Available online: https://blog.pagefreezer.com/social-media-evidence-500000-litigation-cases (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Wright, P. Neal Ysart Legal Scrutiny of OSINT Evidence and the Access to Digital Devices in Court: Key Case Law and Best Practices. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/legal-scrutiny-osint-evidence-access-3gbjf/ (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- 06-1893—Lorraine et al v. Markel American Insurance Company—Content Details. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCOURTS-mdd-1_06-cv-01893 (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- 06-1497—Capitol Records, Inc et al v. Thomas-Rasset—Document in Context. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/USCOURTS-mnd-0_06-cv-01497/context (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- People v. Price 2017 New York Court of Appeals Decisions New York Case Law New York Law U.S. Law Justia. Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/new-york/court-of-appeals/2017/58.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- United States v. Farrad, No. 16-6730 (6th Cir. 2018) Justia. Available online: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/ca6/16-6730/16-6730-2018-07-17.html (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Can Social Media Be Used in Court? 23 Court Cases That Prove Social Media Evidence Can Make or Break a Case. Available online: https://blog.pagefreezer.com/social-media-digital-evidence-forensics-court-cases (accessed on 22 November 2025).

- Supreme Court of British Columbia, C.C. ICD—R. v. Hamdan—Asser Institute. Available online: https://www.internationalcrimesdatabase.org/Case/3306/ (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- Taiwan Supreme Court Judgment No. 320. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20251129025708/https://judgment.judicial.gov.tw/FJUD/data.aspx?ty=JD&id=TPSM,112%2c%e5%8f%b0%e4%b8%8a%2c320%2c20230817%2c1 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Basumatary, B.; Kalita, H.K. Social Media Forensics—A Holistic Review. In Proceedings of the 2022 9th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 23–25 March 2022; pp. 590–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidya, V.; Saly, K.; Balan, C. Forensic Acquisition and Analysis of Webpage. In Proceedings of the 2022 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT), Hubli, India, 24–26 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, C.; Ianni, M.; Seminara, G.; Guzzo, A.; Fortino, G. A Forensic Framework for Screen Capture Validation in Legal Contexts. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Cyber Security and Resilience (CSR), London, UK, 2–4 September 2024; pp. 127–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Yu, X. A Survey on Blockchain Technology and Its Security. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2022, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, Q. A Study of a Blockchain-Based Judicial Evidence Preservation Scheme. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2024, 5, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Ren, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yin, X.; Shen, Z.; Kim, H.J. Blockchain-Based Trusted Electronic Records Preservation in Cloud Storage. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2019, 58, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Justice, Taiwan. Blockchain-Applied Judicial Alliance for Digital Era Common Verification Platform. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20250505075608/https://b-jade.moj.gov.tw/Default.aspx (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Transaction Flow—Hyperledger Fabric Docs Main Documentation. Available online: https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/en/latest/txflow.html (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Sheng, Z.; Song, L.; Wang, Y. Dynamic Feature Fusion: Combining Global Graph Structures and Local Semantics for Blockchain Phishing Detection. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2025, 22, 4706–4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Song, L.; Qian, P.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Jia, Y. DiT-SGCR: Directed Temporal Structural Representation with Global-Cluster Awareness for Ethereum Malicious Account Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.20123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Tian, Y.; Huang, Y.; Xue, T.; Li, P.; Liu, Y. The Role of Transformer Models in Advancing Blockchain Technology: A Systematic Survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2026, 163, 112968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Tian, Y.; Qian, P. LMAE4Eth: Generalizable and Robust Ethereum Fraud Detection by Exploring Transaction Semantics and Masked Graph Embedding. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 10260–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Jia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, S. Ethereum Fraud Detection via Joint Transaction Language Model and Graph Representation Learning. Inf. Fusion 2025, 120, 103074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafarani, R.; Liu, H. Connecting Corresponding Identities across Communities. In Proceedings of the Third International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, San Jose, CA, USA, 17–20 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, T.; Tan, Q.; Shi, J.; Guo, L. Identifying Users across Different Sites Using Usernames. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 80, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Peng, Y.; Ji, W.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q. User Identification Based on Display Names Across Online Social Net-works. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 17342–17353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motoyama, M.; Varghese, G. I Seek You: Searching and Matching Individuals in Social Networks; ACM Digital Library: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781605588087. [Google Scholar]

- Raad, E.; Chbeir, R.; Dipanda, A. User Profile Matching in Social Networks. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Network-Based Information Systems, Takayama, Japan, 14–16 September 2010; pp. 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iofciu, T.; Fankhauser, P.; Abel, F.; Bischoff, K. Identifying Users Across Social Tagging Systems. In Proceedings of the Fifth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media, Barcelona, Spain, 17–21 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Na, Y.; Yinliang, Z.; Lili, D.; Genqing, B.; Liu, E.; Clapworthy, G.J. User Identification Based on Multiple Attribute Decision Making in Social Networks. China Commun. 2013, 10, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, A.; Shmatikov, V. De-Anonymizing Social Networks. Proc IEEE Symp Secur Priv 2009, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Pei, J.; Tang, G.; Luk, W.-S.; Jiang, D.; Hua, M. Finding Email Correspondents in Online Social Networks. World Wide Web 2012, 16, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensity AI: Best Deepfake Detection Software in 2025. Available online: https://sensity.ai/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Deepfake Detection—Reality Defender. Available online: https://www.realitydefender.com/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Xmind—Mind Mapping App. Available online: https://xmind.com/ (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- ISO/IEC 27001:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Management Systems—Requirements. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- ISO/IEC 27002:2022; Information Security, Cybersecurity and Privacy Protection—Information Security Controls. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.