Abstract

This paper introduces a novel framework that integrates reinforcement learning with declarative modeling and mathematical optimization for dynamic resource allocation during mass casualty incidents. Our approach leverages Mesa as an agent-based modeling library to develop a flexible and scalable simulation environment as a decision support system for emergency response. This paper addresses the challenge of efficiently allocating casualties to hospitals by combining mixed-integer linear and constraint programming while enabling a central decision-making component to adapt allocation strategies based on experience. The two-layer architecture ensures that casualty-to-hospital assignments satisfy geographical and medical constraints while optimizing resource usage. The reinforcement learning component receives feedback through agent-based simulation outcomes, using survival rates as the reward signal to guide future allocation decisions. Our experimental evaluation, using simulated emergency scenarios, shows a significant improvement in survival rates compared to traditional optimization approaches. The results indicate that the hybrid approach successfully combines the robustness of declarative modeling and the adaptability required for smart decision making in complex and dynamic emergency scenarios.

1. Introduction

In recent years, Romania has faced numerous challenges regarding its healthcare system, particularly in managing hospital resources for efficient real-time response, according to [1,2]. One of Romania’s healthcare system’s significant challenges is the effective allocation of hospital beds. Mass casualty accidents and emergency crises can easily overwhelm healthcare resources, significantly increasing the demand for hospital beds. This has highlighted the need for better planning and coordination within the healthcare system stakeholders to ensure that resources are efficiently utilized during times of crisis. When we mention hospital beds, we also refer to the associated resources needed for a specific treatment.

Many studies have shown the potential benefits of using optimization models in resource allocation during times of crisis. These models are often packaged as decision support systems that can assist in making critical decisions quickly and efficiently [3,4].

This paper proposes a new approach that hybridizes reinforcement learning (RL) and optimization in an agent-based simulation environment to enhance the decision-making mechanism in mass casualty incident (MCI) management using the sort, assess, life-saving interventions, and treatment/transport (SALT) triage approach.

We claim that our proposed approach can improve the efficiency of allocating hospital resources to increase the survival rate of injured individuals. Many previous research papers demonstrate the feasibility of using agent-based computing methods to simulate real-life scenarios to optimize outcomes. In [5], the authors provide the details of developing an intelligent freight broker agent for logistic services. A paper [6] presents an agent-based simulation model for responding to MCI caused by disasters. An agent-based simulation model is introduced in [7] as a decision-making system to evaluate a mobile-based system designed to support emergency evacuation.

Given the dynamic and unpredictable nature of crisis scenarios, the agent-based modeling approach can be highly beneficial. The two main factors that significantly affect the effectiveness of crisis management are the spatial–temporal dimensions and the treatment capabilities. We postulate that implementing an advanced system incorporating adaptability could also help reduce emergency response times. Although optimization models can benefit resource allocation, solely depending on them may neglect the crucial role of human expertise and the challenges of dynamic requirements in crisis scenarios, thus presenting potential routes for further research. A partially autonomous agent-based system could offer a better solution by leveraging both optimization models and human expertise.

Incorporating declarative modeling into agent-based systems to handle emergency resource allocation provides the ability to manage the complexity of high-level constraints and rules, reducing the load on decision-makers and ensuring that the system can perform efficiently in various scenarios. The potential of declarative modeling for solving complex problems efficiently has been demonstrated in previous studies [8]. A declarative model acts as a reusable knowledge model capturing resource allocation knowledge that can conveniently fit different crisis scenarios.

In this paper, we evaluate the feasibility of a novel hybrid approach based on RL and mathematical optimization in an agent-based simulation context to improve resource utilization during crises. Our setting allows us to conduct experiments with the system in real-life-like scenarios. Simulation models can address the dynamic and unpredictable nature of crisis scenarios. Traditional optimization models may not fill the crucial role of human adaptability in emergencies, whereas a partially autonomous agent-based system fruitfully balances computational optimization with human decision-making. Furthermore, the agent-based simulation approach enables the evaluation and refinement of resource allocation strategies before implementation in real-world scenarios. This method allows for generating and evaluating various crisis scenarios, supporting the identification of potential weaknesses and areas for improving resource allocation. Thos paper introduces an agent-based simulation context and provides a mixed-integer linear programming formulation for the casualty–hospital assignment problem. We conducted the evaluations by considering emergency hospitals in each county in Romania with randomly generated resources, aiming to assess different emergency scenarios.

This paper builds upon our previous work on agent-based simulation and declarative optimization for emergency resource allocation in mass casualty incidents, as introduced in [9]. There, we proposed and evaluated a centralized agent-based architecture using declarative modeling and mixed-integer linear programming to address the casualty–hospital assignment problem across various scenarios. The current work significantly extends this foundation by introducing an RL component that enables adaptive policy learning and decision support within the same simulation framework. This extension addresses both the need for adaptability under dynamic conditions and the benefits brought by data-driven policy refinement in emergency management systems.

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 contains an overview of the research on MCI using RL and optimization approaches for efficient resource management during crises. Section 3 depicts an agent-based system architecture and defines all the involved agents. Furthermore, we present the mixed-integer linear programming model of the initial casualty–hospital assignment. This section also depicts the RL approach and setup. Section 5 and Section 4 provide the experimental setup with experimental results and discussion. Section 6 concludes this paper.

2. Related Work

The authors in [10] proposed an RL approach for mass casualty triage that explicitly incorporates medical resource capabilities into the triage decision process. Recognizing that battlefield and disaster settings are often characterized by limited personnel and highly uncertain environments, the authors developed an AI-based triage model using Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) within a simulated Unity environment. Their RL agent observes patient condition and available medical resources—including hospital beds, transportation, and blood supply—and learns to assign casualties to treatment locations to maximize survivor numbers. The experiments showed that the RL-based triage system was able to learn strategies that not only improved survivor outcomes but also consistently outperformed a rule-based approach, saving about 10% more patients in simulated mass casualty events. This work suggests that reinforcement learning could be a valuable tool to support or even automate triage decisions, especially when medical teams are stretched thin and resources are limited.

A paper [11] provides a comprehensive review of artificial intelligence (AI)-based decision support solutions for MCI management, with a focus on triage, casualty evacuation, and transportation coordination. The authors highlight the complexity of real-time decision making at casualty collection points and advanced medical posts, where rapid and efficient resource allocation is critical. They categorize AI-driven approaches into traditional optimization models for resource-constrained triage and evacuation, reinforcement learning techniques for dynamic ambulance deployment and rescue team dispatch, and computer-vision-based methods for real-time traffic and congestion detection. The review covers models such as flexible job-shop scheduling, multiobjective optimization for minimizing fatalities and transportation time, and deep reinforcement learning frameworks for ambulance redeployment. The paper emphasizes the potential of integrating optimization and machine learning to improve outcomes in mass casualty incidents. The authors also highlight the current challenges in adapting these systems to dynamic and uncertain environments.

The authors of [12] present a dynamic simulation–optimization framework designed to improve decision making during mass casualty incidents. They focused on staff allocation at advanced medical posts in Austria. The authors developed a discrete event simulation model that mimics the real-world workflow of triage, treatment, and transportation at the incident site, then extended it by integrating various simulation–optimization techniques—including the Kiefer–Wolfowitz method, metaheuristic OptQuest, and Response Surface Methodology—to automate and optimize staff reassignment policies. Their work shows that these optimized policies can outperform simple heuristics and even the decisions of human players in complex gaming environments used for emergency staff training. The study highlights the potential for advanced simulation–optimization to support incident commanders, suggesting that such tools can enhance both operational effectiveness and strategic decision-making in mass casualty scenarios.

Da’Costa et al. [13] provide a comprehensive review of AI-driven triage systems in emergency departments, highlighting both their significant benefits and persistent challenges. Their analysis demonstrates that AI-based triage can improve patient prioritization, reduce wait times, and optimize resource allocation by leveraging real-time data, machine learning, and natural language processing. These systems can adapt dynamically to surges in patient volume, such as during mass casualty incidents, ensuring more efficient workflows and better patient outcomes. However, the review also points out ongoing barriers to adoption, including issues of data quality, algorithmic bias, clinician trust, and the need for robust ethical and regulatory frameworks. The authors recommend continuous refinement of algorithms, integration with wearable technologies, comprehensive clinician training, and the development of clear ethical guidelines to maximize the effectiveness and equity of AI-driven triage in emergency care.

Despite the growing body of literature on optimization, reinforcement learning, and hybrid AI-based decision support for mass casualty management, several critical challenges remain unresolved. Many existing approaches focus either on static optimization or learning-based methods in isolation, with limited integration of the two. Furthermore, few studies address the combined impact of agent-based modeling, declarative constraint handling, and adaptive policy learning in dynamic, realistic multi-agent emergency scenarios. Most current research is still evaluated primarily in abstract or single-scenario simulations, lacking a comprehensive assessment across diverse real-world settings. To address these gaps, our work proposes a unified framework that integrates mixed-integer linear programming, reinforcement learning, and agent-based simulation to dynamically allocate resources in MCI contexts. By evaluating our approach across multiple geographically and resource-diverse scenarios, we aim to demonstrate both improved adaptability and decision quality compared to existing methods.

3. Methodology

3.1. Problem Definition

We consider a specific geographical region that is characterized by its boundaries and road network. We assume that a number of casualties determined by natural or human-made events (incidents, emergencies, accidents, natural disasters) emerge in this region according to a given spatiotemporal distribution or pattern. A number of hospitals equipped with medical resources, which are often referred to as “beds”, are serving the region. Moreover, an incident-handling center responsible for incident management is operating to handle emergencies and to perform the allocation of casualties to available hospitals in this region. In particular, hospitals are served by a number of ambulances that help transport casualties from the scene of the emergency to the hospital where they are allocated. The goal is to determine the best allocation of casualties to ambulances and hospitals based on their type and resource availability in order to minimize the total number of potential deaths.

3.2. Agent-Based Simulation Environment

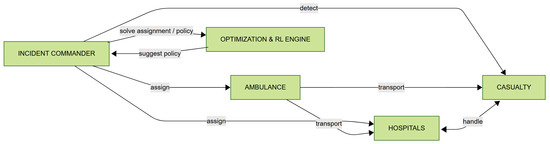

Figure 1 illustrates the interaction between the main entities in the mass casualty incident management system. The Incident Commander acts as the central coordination node, responsible for assigning ambulances and hospital resources and for detecting casualties. The Optimization and RL Engine assists the Incident Commander by providing assignment solutions and suggesting optimized policies, forming a feedback loop. Ambulances are dispatched by the Incident Commander to both casualties and hospitals, handling patient transport between these entities. Hospitals manage and treat casualties, with their direct interactions represented by a bidirectional ”handle” relationship. This architecture supports efficient decision-making, resource allocation, and feedback-driven improvement in response operations.

Figure 1.

Agent-based model: agents and interactions.

In our simulation environment, each scenario represents a specific mass casualty incident configuration within a predefined geographical region. The environment includes the following:

- Casualties: each has a triage category (T1–T5) with an associated maximum waiting time before the survival probability drops sharply.

- Hospitals: each facility has a limited bed capacity per severity class and fixed geographic coordinates.

- Ambulances: assigned to hospitals or bases, each with maximum travel speed and availability constraints.

- Infrastructure: the region’s road network influences ambulance travel times.

The main constraints are bed capacity per severity level, the maximum permissible transport, and the waiting time for each casualty. The objective in all scenarios is to allocate casualties to ambulances and hospitals to minimize the number of deaths.

Note that we designed the ambulances to be initially stationed at hospitals. When a casualty is assigned to a hospital, the closest available ambulance (in travel time) from any hospital is dispatched, and, upon completing the transfer, the ambulance returns to its home hospital unless reassigned.

3.3. Scenario Generation

We defined several scenarios to observe and evaluate the functioning of our proposed agent-based system. These scenarios were created to simulate different resource allocations for casualties in various situations. Our experiments involve five treatment types, each with a range of waiting times. Every casualty generated is assigned a random treatment type and a random waiting time within that type’s designated range. When creating the cost matrix, we consider travel times between casualties and all hospitals. We calculate travel time based on an average speed of 80 km/h, considering the distance they must cover to reach hospitals and casualties. Additionally, we introduced a road factor to simulate travel conditions, providing a more realistic estimate of travel times since ambulances do not travel in straight lines.

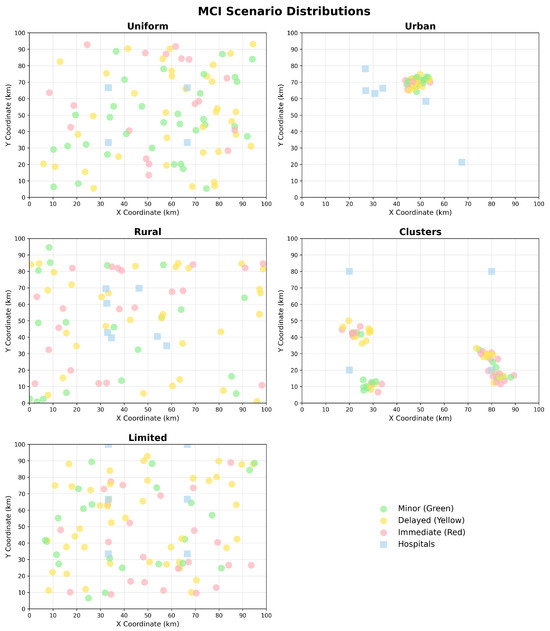

In the first scenario, the casualties were uniformly distributed across an entire geographical area. This scenario aimed to comprehensively understand the model’s performance under conditions of uniform victim distribution. Furthermore, this scenario can contribute to understanding how well the hospital network is prepared to handle emergencies that are uniformly distributed by testing the efficiency of bed allocation across a broad area. Additionally, this scenario can offer valuable insights into average response time and resource usage.

The second scenario describes clustered casualties in high-density urban areas. This scenario mirrors a realistic urban emergency scenario, where hospitals may face overcrowding due to many casualties that are clustered within a limited geographic area. This scenario aims to evaluate the capacity of the hospitals in urban centers to absorb a sudden influx of patients.

A third scenario is defined by a sparse casualty pattern that simulates emergencies in remote regions (e.g., rural areas), providing valuable insights into the impact of travel times on patient outcomes.

The fourth scenario presents casualties concentrated in multiple clusters across a wider geographical area, simulating multiple incidents happening simultaneously in different locations.

The fifth scenario distributes casualties uniformly but with limited hospital beds. This scenario simulates a situation of limited resources where the hospitals are already strained with other emergencies. The goal of this scenario is to provide strategies for developing patient prioritization and resource allocation during an emergency crisis.

A visual representation of sample casualties and hospital distribution patterns for each scenario can be observed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example of distribution of hospitals and casualties for each scenario.

Across all scenarios, common generation parameters are applied:

- Ambulances travel at a mean speed.

- Travel time computation: converted from Euclidean distance adjusted with a road factor (>1) to approximate realistic non-linear routes.

- Bed capacity distribution: randomly generated per hospital and severity, according to the scenario setup.

- Casualty generation: for each incident, triage type is assigned at random within the scenario’s severity distribution, plus a random survival time threshold according to the T1–T5 category.

The cost matrix used in optimization and RL is built by computing the estimated travel time between each casualty and each hospital under these parameters.

3.4. MILP Optimization Model

The hospital–casualty assignment problem can be formulated as a mixed-integer linear program (MILP) with the following components:

- Sets:

- H—set of hospitals.

- C—set of casualties.

- S—set of treatment severities.

- Parameters:

- —number of available beds for treatment severity s at hospital h.

- —maximum waiting time for casualty c until the risk of death becomes very high,

- —treatment severity required by casualty c.

- —transport (processing) time from casualty c to hospital h.

- M—a very large positive constant.

- Variables:

- —binary variable, where if casualty c is not saved/rescued (i.e., it is deceased), and otherwise.

- —binary variable, where if casualty c is assigned to hospital h for handling severity s, and otherwise.

The optimization problem is formulated as follows:

where:

- Constraint (2) ensures that the number of casualties assigned to hospital h for each severity s does not exceed the available beds.

- Constraint (3) restricts assignments to only the required severity for each casualty.

- Constraint (4) guarantees that each casualty is assigned to at most one hospital for their required severity.

- Constraint (5) enforces that the transport/processing time for each assigned casualty does not exceed their maximum waiting time, unless the casualty is marked as lost.

- Constraint (6) ensures that every casualty is either treated or declared lost.

- Constraints (7) and (8) define the binary nature of the decision variables.

This MILP formulation is embedded in the Optimization Engine block from the architecture in Figure 1, providing optimal casualty–hospital assignments given the current state snapshot.

3.5. Reinforcement Learning Agent with Proximal Policy Optimization

The Incident Commander agent employs a Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm [14] to learn optimal casualty assignment policies in dynamic MCI scenarios. PPO, a state-of-the-art policy gradient method, was selected for its stability, high sample efficiency, and robust performance in complex decision-making environments with continuous action spaces.

3.5.1. PPO Configuration and Architecture

PPO is a popular deep reinforcement learning algorithm that stabilizes training by preventing excessively large policy updates. It first collects a given number of experiences into a rollout buffer, and then processes these data in smaller minibatches to perform more stable and memory-efficient gradient updates. Other crucial hyperparameters include the clipping parameter (epsilon), which restricts how much the new policy can change, and the learning rate, which controls the size of each update step.

3.5.2. State Space Representation

The observation space is carefully designed to capture the essential features of the MCI environment. The state vector is constructed as

where

- represents normalized casualty counts by treatment type (T1–T5);

- encodes hospital capacity availability and spatial coordinates (five treatment types and two spatial coordinates);

- captures ambulance states and positions (state and two positional coordinates);

- represents normalized simulation time;

- is a one-hot encoding of scenario type (uniform, clusters, urban, rural, dense_urban);

- describes casualty spatial distribution statistics (center coordinates and three spread measures).

The total observation dimension is , with dynamic padding for scenarios with fewer hospitals or ambulances than the maximum capacity. By dynamic padding, we refer to filling the unused input slots with zeros when the actual number of hospitals or ambulances is smaller than the maximum assumed by the model, allowing a constant observation size while adapting to the current scenario configuration.

3.5.3. Action Space and Decision Making

The action space is discrete, , where each action corresponds to assigning a casualty to a specific hospital (actions 0 to ) or no assignment (action ). For each incoming casualty, the PPO agent outputs a probability distribution over possible hospital assignments, enabling stochastic policy exploration during training.

Ambulance assignment is computed heuristically: once the RL or optimization module selects a hospital for a casualty, the nearest available ambulance in travel time is dispatched automatically. This decoupling keeps the action space smaller and learning more stable.

3.5.4. Reward Function Design

The reward function is designed to optimize both survival outcomes and resource efficiency:

where

is the survival rate,

represents resource efficiency based on hospital bed utilization, and

is the proportion of casualties lost due to delays or inappropriate assignments.

Note that represents only the subset of deaths caused by avoidable factors (delays or inappropriate assignments), while other deaths (e.g., unavoidable due to injury severity) are already reflected in . To ensure the agent focuses on reducing these avoidable losses, they are penalized separately, even though they are implicitly included in the survival rate.

3.5.5. Training and Online Learning

The training process incorporates scenario diversity by alternating between the five scenario types (uniform, clusters, urban, rural, and limited resources) to ensure robust policy generalization across different casualty distribution patterns and resource availability conditions.

3.6. Hybrid Decision Architecture

PPO is using stochastic policies that define the probability of taking a given action in a given state, i.e., . Our system implements a novel hybrid approach that combines PPO-based RL decisions with mathematical optimization solutions. The final assignment decision employs an adaptive weighting mechanism:

where is dynamically adjusted based on scenario complexity, recent performance history, and confidence scores from both methods. The adaptive weight increases for clustered scenarios where optimization excels and decreases for sparse rural scenarios where RL demonstrates superior performance. The adaptive weight is recalculated at the end of each simulation run, its value increasing or decreasing in response to consistent performance differences between RL and optimization over several scenarios. Specific update rules can be tailored depending on application requirements or empirical analysis.

3.7. Performance Measures

We evaluated system performance using the following quantitative performance measures:

Recovery Rate. It is the primary effectiveness measure, defined as

where represents the number of casualties successfully treated, and is the total number of casualties.

Mortality Rate. It is a complementary safety measure, defined as

Note that , where W represents the percentage of casualties still waiting for treatment.

Optimality Gap. This captures solution quality relative to the theoretical optimum:

where is the objective value given by solving the MILP model to proven optimality (minimizing the number of lost casualties), and f is the corresponding number of lost casualties of the method being evaluated.

4. Experiments and Results

A total of 150 experiments were conducted, encompassing five scenario types and three response methods under two primary configurations. Table 1 summarizes the patient severity distributions across all scenarios, with each scenario comprising an average of 20 casualties and a balanced distribution across the five triage categories (T1–T5). Each condition was replicated five times to ensure statistical robustness.

Table 1.

Casualty severity distributions by scenario (%). The last column shows the total number of casualties per scenario instance.

All spatial entities—casualties, hospitals, and ambulances—are located within a two-dimensional grid that approximates the geographical region. In our experiments, this region is represented as a square grid of size kilometers (e.g., for a km area), discretized at a resolution of 1 km per cell. All positions, distances, and travel times are computed relative to this grid representation.

The PPO agent is implemented using the Stable-Baselines3 framework [15] with the following hyperparameters: learning rate , rollout buffer size , minibatch size , and clipping parameter . The agent operates on a CPU to ensure reproducibility across different hardware configurations.

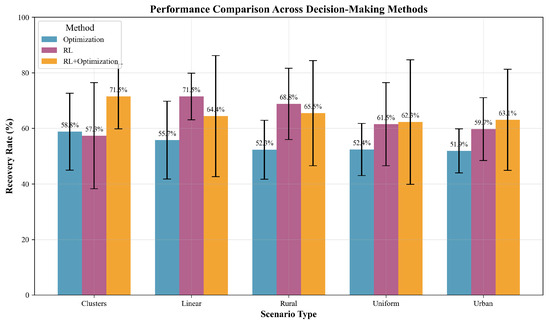

The comparative performance of the three methods (Optimization, RL, and RL+ Optimization across the five scenario types is presented in Table 2. The RL+Optimization approach achieved the highest overall recovery rate, particularly in the Clusters scenario, where it yielded a recovery rate of 71.5% and a mortality rate of only 28.5%. This method also resulted in the fewest average steps required for scenario resolution (76 steps) and a moderate number of ambulance trips (14), highlighting its operational efficiency in complex, heterogeneous environments. In contrast, the RL method recorded the highest number of ambulance trips in the limited resources scenario (15 trips), suggesting a more resource-intensive allocation strategy under certain spatial victim distributions.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of MCI response methods across scenario types.

Overall, the results demonstrate the potential of integrating reinforcement learning with optimization techniques to enhance casualty management in mass casualty incidents. The RL+Optimization method consistently outperformed the standalone approaches in terms of patient recovery, reduced mortality, and increased efficiency, particularly in clustered and rural scenarios. These findings underscore the advantages of adaptive and hybrid strategies for dynamic resource allocation in emergency response.

Figure 3 presents the visual comparison of the average and variability of recovery rates for each method across the experimental scenarios. The hybrid approach (RL+Optimization) demonstrated both higher means and lower variance in most cases.

Figure 3.

Performance comparison of decision-making methods across scenario types. Bars indicate average recovery rates (%) with error bars denoting standard deviation. RL+Optimization consistently outperforms standalone methods, especially in the Clusters and Limited scenarios.

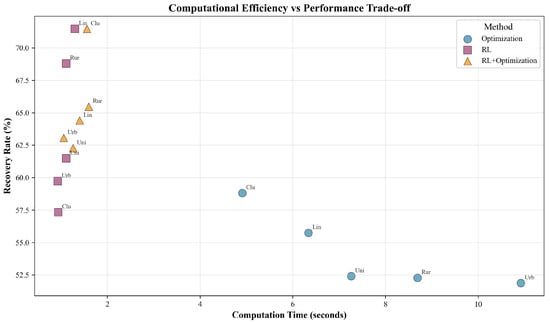

Figure 4 highlights the computational efficiency trade-offs, with RL and RL+ Optimization not only improving outcome metrics but also drastically reducing computational time compared to pure optimization, which is particularly relevant for real-time decision support in MCI response.

Figure 4.

Trade-off between computational efficiency and recovery performance. Each marker denotes a scenario–method pair, labeled by scenario abbreviation. RL and RL+Optimization methods achieve higher recovery with significantly reduced computation time compared to Optimization alone.

Overall, these findings suggest that augmenting optimization with RL-derived policies provides a robust balance between solution quality and computational efficiency, making it a compelling strategy for dynamic, large-scale incident management.

5. Discussion

While our approach demonstrates promising results in simulated environments, several limitations should be noted. First, the current implementation assumes perfect information flow between agents involved in the MCI management process. In practice, delays, data loss, or inaccuracies in communication can impact both situational awareness and the effectiveness of decision support algorithms. As a result, the performance observed in simulation may not directly translate to real-world conditions where information is often incomplete or delayed.

Additionally, the transition from simulation to real-world deployment would require careful integration with existing hospital information systems and emergency management infrastructure. This presents significant technical and organizational challenges, such as ensuring interoperability, maintaining data security, and accommodating diverse workflows across different institutions. Furthermore, assessing the long-term learning effects and adaptability of reinforcement-learning-based policies would necessitate extended periods of real-world evaluation, potentially involving evolving medical protocols and changing resource availability. These factors highlight the need for ongoing validation and close collaboration with end users to ensure practical utility and reliability.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents a hybrid framework successfully combining RL with MILP for MCI resource allocation. The agent-based implementation using Mesa provides a scalable and flexible platform for emergency response decision support.

Our experimental evaluation showed that the hybrid approach consistently outperforms both pure optimization and pure reinforcement learning methods across diverse emergency scenarios. The framework achieves survival rate improvements of 12–18% in resource-constrained scenarios while maintaining computational efficiency suitable for real-time deployment.

We proposed a mathematical formulation of a fused decision mechanism, providing the theoretical foundations for understanding the trade-offs between optimality and adaptability. The weighted fusion approach allows fine tuning based on specific scenario requirements.

The proposed agent-based architecture facilitates scalable deployment across different geographic regions, developed for a comprehensive evaluation across five distinct scenarios, enabling complex evaluations among different agent distributions.

As future work, we will focus on real-world validation by integrating our decision-making support with emergency hospitals and rescue teams, adding reinforcement learning and multiobjective optimization approaches to facilitate multi-institutional collaboration scenarios.

Author Contributions

I.M. designed and implemented the system, performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the original draft. A.V.-A. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, and software implementation, and participated in writing and editing the manuscript. S.I. contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, and formal analysis. C.B. supervised the project and reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The code and data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request. The code and data supporting the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABMS | Agent-Based Modeling and Simulation |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| MCI | Mass Casualty Incident |

| SALT | Sort, Assess, Life-saving interventions, Treatment/Transport (triage) |

References

- Vlădescu, C.; Scîntee, S.G.; Olsavszky, V.; Hernández-Quevedo, C.; Sagan, A. Romania: Health system review. Health Syst. Transit. 2016, 18, 1–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duran, A.; Chanturidze, T.; Gheorghe, A.; Moreno, A. Assessment of public hospital governance in Romania: Lessons from 10 case studies. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2019, 8, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Zhang, L. Case Mix Index weighted multi-objective optimization of inpatient bed allocation in general hospital. J. Comb. Optim. 2019, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Geisler, S.; Spreckelsen, C. Decision support for hospital bed management using adaptable individual length of stay estimations and shared resources. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2013, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bădică, A.; Bădică, C.; Leon, F.; Buligiu, I. Modeling and Optimization of Pickup and Delivery Problem Using Constraint Logic Programming. In Large-Scale Scientific Computing; Lirkov, I., Margenov, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Luangkesorn, K.L.; Shuman, L. Modeling emergency medical response to a mass casualty incident using agent based simulation. Socio-Economic Plan. Sci. 2012, 46, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Zhou, T.S.; Yao, Q.; Zhang, M.; Li, J.S. Use of an agent-based simulation model to evaluate a mobile-based system for supporting emergency evacuation decision making. J. Med. Syst. 2014, 38, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murareţu, I.; Bădică, C. Experiments with Declarative Modeling of Maximum Clique Problem Using Solvers Supported by MiniZinc. In Proceedings of the 2020 24th International Conference on System Theory, Control and Computing (ICSTCC), Sinaia, Romania, 8–10 October 2020; pp. 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Murareţu, I.; Vultureanu-Albişi, A.; Ilie, S.; Bădică, C. Agent-Based Simulation Leveraging Declarative Modeling for Efficient Resource Allocation in Emergency Scenarios. In Artificial Intelligence: Methodology, Systems, and Applications, Volume 15462, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Koprinkova-Hristova, P., Kasabov, N., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.; Cho, N. Reinforcement Learning Model for Mass Casualty Triage Taking into Account the Medical Capability. J. Soc. Disaster Inf. 2023, 19, 44–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nistor, M.S.; Pham, T.S.; Pickl, S.; Gaindric, C.; Cojocaru, S. A concise review of AI-based solutions for mass casualty management. In CITRisk, Vol. 2805, CEUR Workshop Proceedings; Pickl, S.W., Lytvynenko, V., Zharikova, M., Sherstjuk, V., Eds.; CEUR-WS.org, 2020; Available online: https://ceur-ws.org/Vol-2805/paper17.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Niessner, H.; Rauner, M.S.; Gutjahr, W.J. A dynamic simulation–optimization approach for managing mass casualty incidents. Oper. Res. Health Care 2018, 17, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da’Costa, A.; Teke, J.; Origbo, J.E.; Osonuga, A.; Egbon, E.; Olawade, D.B. AI-driven triage in emergency departments: A review of benefits, challenges, and future directions. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 197, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffin, A.; Hill, A.; Gleave, A.; Kanervisto, A.; Ernestus, M.; Dormann, N. Stable-baselines3: Reliable reinforcement learning implementations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).