1. Introduction

In the intelligent production of the pharmaceutical industry, pills are characterized by their small size, smooth surface, and fragile material [

1]. Pill sorting, as a core process in pharmaceutical packaging, directly affects production efficiency and drug quality. The traditional manual sorting mode relies on visual inspection [

2] and manual screening by operators, which has problems such as low sorting efficiency, high labor costs, and high rates of subjective misjudgment [

3]. In recent years, machine vision technology has shown broad application prospects in industrial automation due to its advantages of non-contact inspection, high-speed data processing, and high-precision feature extraction [

4]. Deep learning-based object detection methods, particularly the YOLO series, have demonstrated superior performance in real-time industrial sorting applications [

5]. In response to the needs of the pharmaceutical industry, vision-based robotic sorting systems have become a key direction for breaking through the bottlenecks of traditional sorting [

1]. This technology captures real-time pill images using industrial cameras. Image processing algorithms enable target recognition and positioning. Through coordinate calibration and motion control, robotic arms execute precise grasping operations. This approach effectively addresses sorting challenges under complex working conditions [

6].

Similar technologies have been applied across various domains. Mohi-Alden et al. developed a machine-vision-based system integrated with an intelligent modeling approach for in-line sorting of bell peppers into desirable and undesirable categories, with capabilities to predict both maturity level and size of the desirable samples [

7]. Mao et al. designed a machine-vision-based sorting system that incorporates image processing, target recognition, and positioning, ultimately achieving sorting through end-effector control [

8]. In order to solve the low speed and low intelligence of a coal gangue sorting robot, a delta robot with an image recognition system was adopted to coal gangue automatic separation, which has been widely used in the packaging and sorting industry [

9].

Zhang et al. developed an enhanced YOLOv8 framework for parcel identification in disordered logistics environments, demonstrating the scalability of deep learning methods in real-world sorting tasks [

10]. In the field of medicine and pharmaceuticals, Zhang et al. developed an automated machine vision system for liquid particle inspection in pharmaceutical injections [

11]. Xue et al. applied a Faster-R-CNN-based classification model for internal defect detection and online classification of red ginseng [

12]. However, both studies did not place significant emphasis on the grasping mechanism.

Our system addresses three major technical challenges in pharmaceutical automation: pill recognition accuracy, positioning precision, and robotic coordination efficiency. The system constructs a high-resolution image acquisition platform and develops core algorithms integrating template matching, three-point calibration, and Modbus/TCP real-time communication [

13]. The main contributions include the following:

- (1)

An integrated system that combines image acquisition, multi-color pill recognition, precise positioning, robotic arm grasping, and coordinated control has been constructed. Through the deep integration of visual algorithms and robotic arms, the system achieves full automation from pill detection to grasping, avoiding the problem of hardware and algorithm disconnection in traditional sorting systems and possessing practical engineering application value.

- (2)

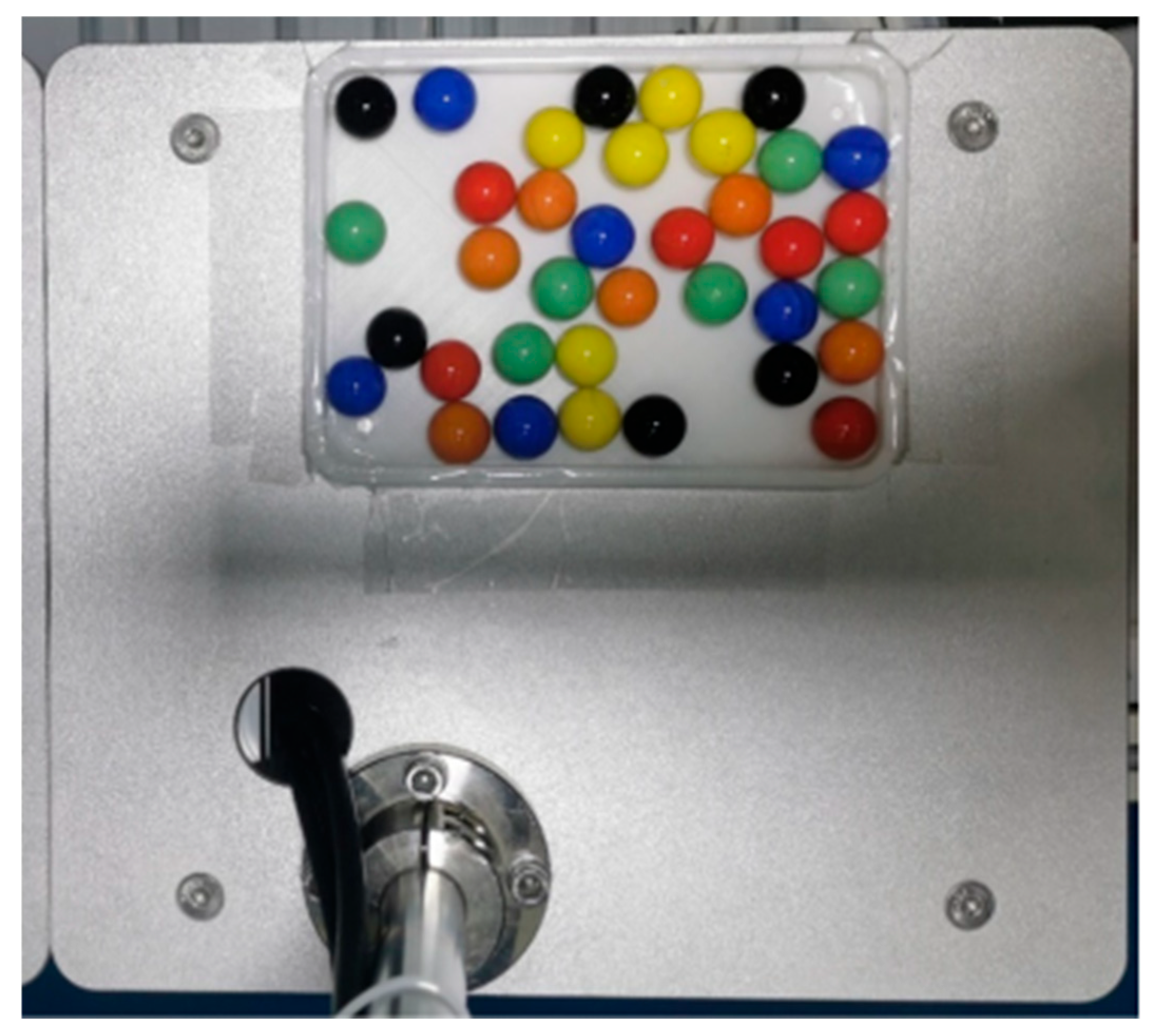

Multi-scenario verification experiments that are close to industrial practice have been designed. The experiments selected six pills of each of the six colors (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and black) (

Figure 1), where yellow, green, blue, and red correspond to the common colors of pharmaceutical tablets (such as vitamin B12, antibiotics, etc.), black simulates sustained-release formulations, and orange simulates the easily confused red-orange color scenario. The system performance was verified under complex conditions of pill overlap ≤ 30% and dynamic illumination of 50–1000 lux, based on the integration of the VisionMaster vision algorithm platform and a domestic HSR-CR605 robotic arm. This provides theoretical and experimental support for the robust design of automated sorting systems under real working conditions. This research offers a feasible technical path and engineering reference for the development of automated sorting systems for actual production lines.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 introduces the design structure and working principle of the sorting and grasping robot system.

Section 3 presents the detailed implementation of the robot system.

Section 3 provides multi-scenario verification experiments and the corresponding analysis in detail. Finally,

Section 5 concludes this paper.

2. System Design and Working Principle

2.1. Design of the Robotic System

As shown in

Figure 2, The system comprises two primary components: hardware design and software design. The hardware design encompasses image acquisition and the robot workstation. The software design includes image processing, communication control, and calibration and mapping units.

The system is developed based on the VisionMaster 4.3.0 industrial vision software platform [

14], with the hardware platform consisting of a Hikvision MV-CU06 CMOS industrial camera (Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) [

15] and an HSR-CR605 robotic arm (Hangzhou Keer Robot Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China).

2.1.1. Image Acquisition Unit

As the core module for pill visual inspection, this unit is composed of a Hikvision MV-CU06 CMOS camera (Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) (4024 × 3036 pixels, 30 fps), an MVL-HF1628M-6MPE fixed-focus lens, and a multi-angle uniform-light LED light source. The camera accurately captures the details of the pill, while the light source suppresses surface reflections. The three components work together to reduce noise and enhance contrast. Once pills are placed on the workbench, the camera and light source synchronously capture images. These images transmit in real-time to the computer, providing high-quality data for subsequent processing.

2.1.2. Robot Workstation

The robot workstation comprises an HSR-CR605 6-axis collaborative robotic arm, a custom vacuum suction end-effector, and a teaching pendant for operation control.

Robot control system: The HSR-CR605 employs an IPC-200 controller with the EtherCAT bus protocol, providing 16-channel digital I/O (NPN type) and ≤1 ms real-time response. The 48 V DC power unit drives joint servo motors with a 5 kg maximum payload. The Hasped teaching pendant connects via Ethernet, enabling intuitive manual guidance, trajectory recording, and status monitoring without requiring complex programming knowledge.

End-effector design: Given pharmaceutical pills’ small size, smooth surfaces, and fragile nature, vacuum suction was selected to avoid mechanical crushing. The end-effector (

Figure 3) integrates a ZU07S vacuum generator with a ZPT06BNJ6-B5-A8 suction cup, mounted via a custom 3D-printed adapter.

Key specifications:

Vacuum generator (ZU07S):

Vacuum pressure: −85 kPa | Flow rate: 12 L/min | Air consumption: 19 L/min

Nozzle: Φ0.7 mm | Supply pressure: 0.45 MPa

Suction cup (ZPT06BNJ6-B5-A8):

Diameter: 6 mm (compatible with 3–8 mm pills)

Material: Nitrile rubber (NBR) with U-shaped flat rib design

Buffer: Swivel-type, 6 mm stroke for angular compliance

Performance: >98% pick success rate, <0.1 s release time, ≤5 g gripping capacity

The nitrile rubber provides chemical resistance and appropriate compliance for pharmaceutical handling, while the swivel buffer accommodates height variations and prevents coating damage. The custom adapter ensures ±0.5 mm positioning precision through bolt connections and slot-based cup alignment.

System integration: The teaching pendant receives pill coordinates from the vision system, enabling the IPC-200 controller to generate collision-free trajectories with EtherCAT real-time control. The robot’s ±0.05 mm repeatability combined with the compliant end-effector achieves ±0.5 mm overall picking precision.

Current limitations: The 6 mm suction cup is validated only for round tablets (3–8 mm), oval caplets, and film-coated pills. Capsules (typically 15–25 mm), triangular tablets, and embossed surfaces require alternative end-effector designs. Long-term rubber wear and performance under dusty conditions warrant further investigation for industrial deployment.

2.1.3. Communication Control

The communication link is established based on the MODBUS/TCP protocol, using the TcpClient master-slave mode (the vision system as the master station, the robot controller IP: 192.168.0.3 as the slave station, and communication through registers 0 to 3). The data is transmitted in RTU binary mode (4-digit hexadecimal encoding, containing pill coordinates and color codes) and is equipped with CRC-16 check (polynomial 0xA001). This configuration maintains a packet loss rate of ≤0.1%, meeting the high-speed sorting requirement of ≥120 pills per minute.

2.1.4. Vision Processing

The VisionMaster platform was selected for its practical advantages: graphical development enables rapid deployment (1–2 months vs. 3–6 months for OpenCV), native support for domestic hardware (HSR-CR605), and low cost (USD < 1000 vs. USD > 5000 for HALCON). The platform achieves ≥95% RGB classification accuracy and <10 ms Modbus/TCP communication delay and supports 108 pills/min sorting efficiency with ±0.5 mm precision.

While VisionMaster’s pre-built modules suit standard color-based sorting effectively, they limit deep learning integration and vendor-independent customization. Future extensions could adopt a hybrid architecture: VisionMaster for real-time control and communication, with OpenCV/PyTorch modules for advanced recognition tasks (e.g., 3D detection, defect inspection). For this study’s scope—multi-color sorting under typical conditions (overlap ≤ 30%, 50–1000 lux)—VisionMaster provides sufficient capability for pharmaceutical automation.

2.1.5. Calibration and Mapping

To align the coordinate systems of the camera and the robotic arm, a three-point calibration method based on Zhang’s method is adopted [

16]. By using three known points, a coordinate transformation relationship is established and a calibration file is generated. This file can be imported later to correct the coordinates and angles of new pills. The method has an error of ≤±0.5 mm. With its simple geometric mapping, it can quickly associate coordinates and is suitable for two-dimensional plane working scenarios.

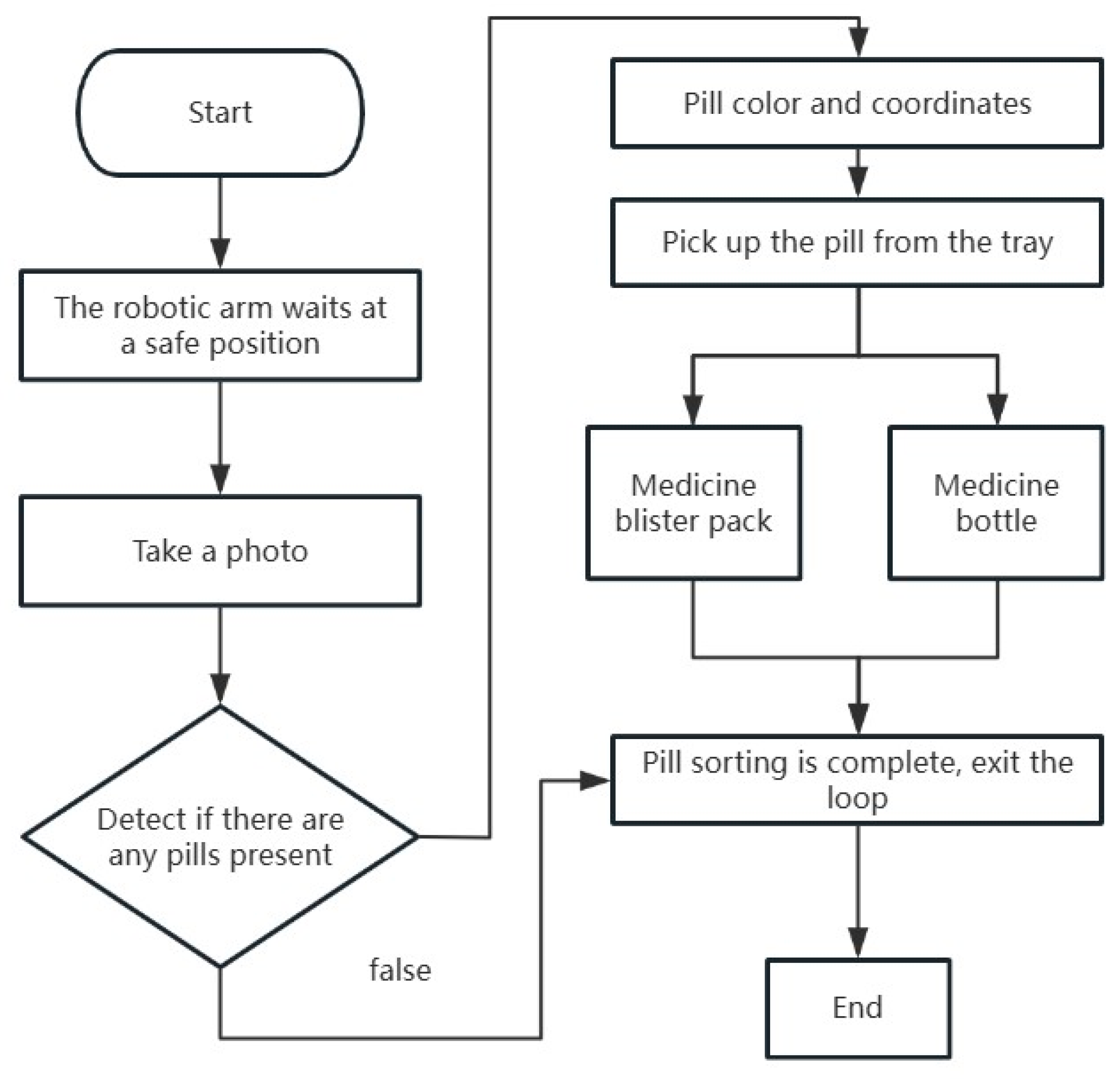

2.2. The Working Principle of the System

As shown in

Figure 4, The working principle of the system is centered on the collaboration between machine vision and robotic motion control. When pills enter the inspection area, the 4024 × 3036-pixel industrial camera captures high-resolution images. Ring-shaped LED illumination ensures uniform lighting conditions.

The processing pipeline consists of four steps:

- (1)

Geometric transformations (horizontal mirroring + 90° rotation) correct coordinate system deviations.

- (2)

Grayscale conversion follows the ITU-R BT.601 standard.

- (3)

Sobel edge detection extracts pill contour features.

- (4)

NCC template matching locates pill center coordinates with ±0.5 mm accuracy.

Subsequently, the system employs a dual-path RGB threshold segmentation strategy to classify multi-colored pills (such as red, orange, and yellow) in parallel. The pill type is determined by the conditional detection module (for example, for red pills, R ∈ [200, 255]). The X/Y coordinates, angle, and other pose information of the pill are then converted in real time into executable instructions for the robot based on the vision-robot coordinate mapping relationship established by the three-point calibration method (error ≤ ±0.5 mm).Finally, the robot teaching pendant receives the sorting instructions through the Modbus/TCP protocol (transmission cycle < 10 ms) and drives the HSR-CR605 robotic arm (repeatability ± 0.05 mm) to accurately perform the grasping action. This forms a closed-loop sorting process of “acquisition—decision—execution.”

2.3. Cost-Performance Analysis

To evaluate the economic viability of domestic equipment localization, a comprehensive cost comparison was conducted between the proposed system and equivalent imported solutions (

Table 1). The comparative analysis of key components yields the following results:

a.Collaborative Robotic Arm: The domestically manufactured HSR-CR605 unit is priced at RMB 120,000, compared to RMB 200,000 for the imported UR5, yielding a cost reduction of 40%.

b.Industrial Camera: The Hikvision mv-cu06 (domestic) is available at RMB 8000 per unit, versus RMB 16,000 for the Basler acA4024-29 um (imported), representing a 50% cost saving.

c.Vision Algorithm Software License: The annual licensing fee for VisionMaster is RMB 20,000, substantially lower than the RMB 80,000 required for HALCON, achieving a 75% cost reduction.

The aggregate analysis demonstrates that the total deployment cost of the domestically manufactured solution is approximately 42% lower than comparable imported alternatives. This significant cost advantage, coupled with equivalent technical performance, validates the economic feasibility and strategic merit of adopting domestically manufactured equipment for industrial vision-guided robotic systems.

Table 1.

Comparative cost analysis of domestic and imported equipment.

Table 1.

Comparative cost analysis of domestic and imported equipment.

| Component Category | Domestically Manufactured Solution | Imported Solution | Domestic Unit Cost | Imported Cost | Cost Reduction |

|---|

| Collaborative robot | HSR-CR60 | Universal Robots | RMB 120,000 | RMB 200,000 | 40% |

| Industrial camera | Hikvision mv-cu06 | Basler acA4024-29 um | RMB 8000 | RMB 16,000 | 50% |

| Vision platform | VisionMaster 4.3.0 | HALCON | RMB 20,000/year | RMB 80,000/year | 75% |

3. Vision-Guided Robotic Sorting System Implementation

3.1. Machine Vision Processing Workflow

3.1.1. Grayscale Conversion and Image Normalization

For the preprocessing of pill images, the core detection algorithms of the system (such as Sobel edge detection and NCC template matching) are all developed based on grayscale images. Grayscale conversion can effectively avoid the interference of multi-color channel noise on subsequent feature extraction, thereby improving the detection accuracy and stability of the algorithms. This system uses the BT.601 standard established by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU-R) to convert RGB color images to grayscale images [

17]. This standard generates grayscale values by performing weighted calculations on the pixel values of the RGB three channels. The specific mathematical expression is:

The grayscale conversion is based on the differences in human visual sensitivity to different color channels [

18] and is implemented using a linear weighted method. The coefficients (0.299, 0.587, 0.114) set by the ITU-R BT.601 standard are derived from the definition of the luminance component (Luma) in video signals, which aligns well with the high sensitivity of about 65% of the cone cells in the human retina to green light (G channel). Compared to the equal-weight method (e.g.,

Gray = (

R +

G +

B)/3), this approach better highlights the significant features of the image and reduces the interference of color noise on subsequent algorithms. Additionally, drawing on Zhang Shanyan’s image [

19] processing workflow in industrial sorting systems, the combination with geometric transformations further enhances the robustness of pill feature extraction.

3.1.2. Feature Extraction and Template Matching

Core Principle of Template Matching Algorithm

Template matching calculates similarity using the Normalized Cross-Correlation (NCC) algorithm [

20], with its mathematical model shown in Equation (2). This method demonstrates good robustness in pill-sorting applications. Template matching is a core technology for target recognition and localization in vision systems. It involves matching predefined pill or positioning plate templates (grayscale images) against real-time captured images. Specifically, the Normalized Cross-Correlation (

NCC) algorithm is used to compute the similarity, as illustrated in

Figure 5, to determine the position and orientation of the pills or positioning plates.

Here, represents the template image, represents the input image, and and represent the grayscale mean values of the template and the image sub-region, respectively. The closer the NCC value is to 1, the better the grayscale distribution of the region matches that of the template.

Figure 5.

Pill similarity.

Figure 5.

Pill similarity.

3.2. Coordinate Transformation and Calibration

3.2.1. Camera and Robot Coordinate Transformation

Due to the mapping deviation between the XY coordinate systems of the camera and the robot, they do not have a simple coaxial matching relationship where “the robot’s

X-axis corresponds to the camera’s

X-axis and the robot’s

Y-axis corresponds to the camera’s

Y-axis.” The actual coordinate correspondence rules are as follows: the robot’s positive X direction corresponds to the camera’s negative Y direction, and the robot’s positive Y direction corresponds to the camera’s negative X direction. To align the two coordinate systems, the system uses a geometric transformation module to adjust the direction of the captured images. Specifically, the coordinate calibration is completed through a combination of horizontal mirroring and a 90° rotation, with the transformation relationship shown in Equation (3).

Here, and are the translation compensation amounts, which are determined through calibration.

3.2.2. Three-Point Calibration Method

Figure 6 illustrates the three-point calibration process. The system employs a three—point calibration method to precisely align the visual and robot coordinate systems [

21]. By selecting three non—collinear feature points (e.g., points 1, 2, and 3) on the calibration board and leveraging the geometric property that “three points define a plane transformation,” it establishes the geometric mapping between the two coordinate systems and calculates the rotation, translation, and scaling parameters. This enables the conversion of visual positioning data to robot execution coordinates. The three-point calibration method is well-suited for planar sorting scenarios where pills are positioned on flat conveyor belts or trays, which represents the majority of pharmaceutical packaging applications. This approach provides sufficient accuracy (≤±0.5 mm) for 2D grasping tasks without the complexity of stereo vision systems. However, we acknowledge that this method does not account for height variations or enable true 3D grasping capabilities. For applications requiring vertical coordinate compensation—such as multi-layer pill-stacking or bin-picking scenarios—alternative calibration approaches would be necessary, including the following: (1) four-point calibration with height measurement using laser displacement sensors; (2) stereo vision or structured light 3D reconstruction; or (3) eye-in-hand calibration configurations with depth cameras [

22,

23]. The current 2D approach was selected based on the planar nature of pharmaceutical sorting tasks and provides a foundation for future 3D extensions.

The system uses a teaching-acquisition method to obtain coordinate data. The robot’s tool end is controlled to touch the three feature points in sequence while simultaneously recording the robot’s mechanical coordinates for each point and capturing the corresponding pixel coordinates with the visual system. These two sets of coordinate data are then input into a predefined mathematical model to calculate the transformation parameters, generating a calibration file that includes rotation, translation, and scaling parameters. The detailed calibration procedure is shown in

Table 2.

3.3. Pill Color Classification and Sorting Decision

3.3.1. Principle of Color Classification

The system implements pill color classification based on the RGB color space model and threshold segmentation theory. The RGB color space model is chosen because it can directly process the numerical values of the three image channels. It has strong hardware compatibility and high computational efficiency and does not require additional color space transformation. By fine-tuning the R/G/B channel thresholds, the pill colors can be precisely defined (e.g., red with R ∈ [200, 255] and green with G ∈ [150, 255]), making it suitable for real-time sorting scenarios. In the threshold segmentation step, corresponding threshold ranges are set for different pill colors (red: R > 200, green: G > 150) to divide image pixels into target and background regions for color classification. Since the R channel values of red and orange overlap (R ≥ 200), further distinction is made through the G channel threshold (orange with G ∈ [100, 200]). For future applications requiring pixel-level segmentation or handling complex pill shapes with irregular boundaries, transformer-based semantic segmentation methods such as SegFormer [

24] could provide more robust solutions, though at the cost of increased computational complexity.

3.3.2. Conditional Detection and Branching Logic

The process of pill identification and sorting is shown in

Figure 7. To achieve the sorting distinction of pills being grasped by the robot and placed into medicine bottles or blister packs, the system has designed a dual-path color detection mechanism. This mechanism optimizes the sorting process through parallel processing and conditional branching logic. In the “Groud combination” module of the vision processing workflow, two “color extraction” modules are deployed in parallel, corresponding to the color classification tasks for pills intended for medicine bottles and blister packs. These modules simultaneously extract target color regions through RGB threshold segmentation (e.g., red with R ∈ [200, 255], orange with G ∈ [100, 200]). Subsequently, the “conditional detection” module assesses the status values of the results in real time from the two color extraction paths (where 1 indicates a valid detection and 0 indicates an invalid detection). If either path outputs a 1, a sorting instruction is triggered, and the process moves to the next stage. If both paths output 0, the current loop is interrupted to prevent unnecessary grasping actions. Finally, the “branching module” is set with an input condition threshold of 1, meaning that the subsequent robot grasping instructions are only executed when a valid pill is detected. This maintains that the sorting action is only triggered when there is a pill at the target location. This mechanism, through dual constraints of parallel detection and conditional filtering, significantly reduces the rate of erroneous grasping and dynamically switches between sorting paths for medicine bottles and blister packs, ensuring the efficiency and reliability of the sorting process.

3.4. VisionMaster Software Process Design

The pill visual processing workflow constructed on the VisionMaster 4.3.0 platform covers the entire chain from image acquisition to feature extraction, classification decision-making, and robot control. It forms a closed loop from visual perception to execution control, effectively ensuring the real-time performance and operational stability of the pill sorting task. The complete workflow is detailed in

Table 3.

4. Experiments and Results Analysis

4.1. Experimental Platform Setup

Figure 8 shows the complete robotic system platform deployed in our laboratory for performance validation. The experimental environment simulated GMP-compliant production conditions (GB 50457-2019 [

25] Class D cleanroom standards): ambient temperature 20–25 °C, relative humidity 40–60%, and illumination 50–1000 lux (varied to test robustness). Test samples included circular pills of five colors (red, blue, white, yellow, orange) with diameters ranging 8–12 mm and thicknesses 3–5 mm, representative of common pharmaceutical tablets.

4.2. Experimental Scheme Design

To comprehensively verify the system’s performance in terms of pill model color recognition accuracy, sorting efficiency, and system stability, an experimental platform for pill sorting and grasping robots based on machine vision was set up, and three types of experimental schemes were designed, as follows:

4.2.1. Vision Process Timing Test

A total of 36 mixed-color pills (6 each of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and black) were selected to construct a multi-color recognition scenario. The complete vision processing workflow was run based on VisionMaster, and the test focused on recording the single-frame processing time of core modules such as “image acquisition,” “edge detection,” “template matching,” and “color classification.” This quantitatively verified the real-time performance of the vision system’s data processing, providing a time benchmark for high-speed sorting scenarios.

4.2.2. Pill Recognition and Sorting Test

The experimental conditions were designed to simulate typical pharmaceutical production line scenarios with pill overlap ≤ 30% and illumination ranging from 50–1000 lux (GB 50457-2019 Class D: 500–1000 lux baseline + supplementary LED ring light, Ra ≥ 80, uniformity > 0.7), representing common lighting variations in GMP-compliant manufacturing facilities [

25]. These conditions reflect standard industrial settings based on pharmaceutical good manufacturing practice guidelines, where environmental factors are controlled to ensure product quality and process reliability. However, we acknowledge that more challenging environments—such as severe background interference from patterned or reflective conveyor surfaces, accumulated dust on optical components, or extreme surface reflections from high-gloss pill coatings—were not included in this initial validation study. These factors may introduce additional recognition challenges in real-world deployments and warrant systematic investigation in future field trials. The total time from system startup to the completion of grasping and placing the last pill in the designated area was recorded. Sorting efficiency was calculated using Formula (4), which is defined as:

4.2.3. Stability Test

To verify system performance stability, experiments were conducted both in the day and at night. During the day, with stable lighting, system components functioned normally, achieving high recognition accuracy and grasping precision. At night, while the lighting device still provided some illumination, the slightly darker conditions could affect the visual system’s image acquisition and processing.

4.3. Results Analysis

4.3.1. Analysis of Vision Process Timing

The module timing data via the system timing view function was obtained as shown in

Table 4:

Image Source Module

The timing of this module significantly increases in the multi-color scenario (by 89 ms). The main reason is that images of multi—colored pills contain richer color levels and detail information. The complexity of the pixel data that the module needs to process is significantly increased, resulting in longer processing time.

High-Precision Matching Module

In the multi-color scenario, the matching time of this module showed minimal fluctuation, increasing only by 2.29 ms. Its overall performance was stable. This confirms that its core algorithm has good robustness in multi—target mixed—matching scenarios and is not significantly affected by the increase in the number of colors.

Total Time for the Entire Process

The total time for the entire multi-color pill recognition process increased by 47.75% compared to the single-color scenario. However, the final time remained within the industrial real-time standard (≤200 ms), fully meeting the actual time requirements for high-speed pill sorting.

Table 4.

Vision process timing.

Table 4.

Vision process timing.

| Module Name | Timing for Two-Color Recognition (ms) | Timing for Multi-Color Recognition (ms) |

|---|

| Image source | 98.15 | 187.77 |

| High—precision matching | 55.27 | 57.56 |

| Geometric transformation | 13.54 | 12.57 |

| Color conversion | 2.17 | 1.96 |

| Total process timing | 197.07 | 291.18 |

4.3.2. Analysis of Color Recognition and Sorting Effectiveness

To verify the system’s color recognition and sorting performance under the conditions of overlap rate ≤ 30% and dynamic illumination of 50–1000 lux, comprehensive experimental validation was conducted. The experimental data statistics and error analysis are shown in

Table 5.

Recognition Effectiveness

By setting the matching score threshold x ≥ 0.8, the system effectively filters out low-confidence matching results, achieving a total recognition accuracy of 94.4%. Among them, blue, yellow, black, and green pills achieved 100% effective recognition. Red and orange pills had four misjudgments in twelve sorting tasks (six samples each), with a recognition confusion rate of 8%, mainly manifesting as orange pills being misjudged as red or red pills being missed due to RGB channel threshold overlap in the red spectrum (R ≥ 200).

The confusion between red and orange pills mainly results from overlapping RGB channel values under certain lighting conditions. To improve accuracy, we plan to optimize the color segmentation process by adjusting the threshold ranges and incorporating a more robust color model (such as HSV) in future work. We will also explore improving lighting uniformity to minimize reflection effects.

Statistical Analysis and Error Characterization:

The statistical analysis presented here (including standard deviations, confidence intervals, and error source quantification) represents additional analysis performed on the existing experimental dataset. No new experiments were conducted; rather, we applied rigorous statistical methods to characterize the variability and uncertainty in our original measurements. The Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals and root-sum-square error analysis provide quantitative assessment of system robustness using the same 36-pill experimental dataset reported in our initial submission.

Recognition accuracy values represent the mean performance across multiple sorting trials. Standard deviation values indicate the variability in recognition rates, with red and orange pills showing higher variance (±16.7%) due to RGB channel overlap in the red spectrum. The 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the Clopper-Pearson method for binomial proportions, accounting for the small sample size. The wide confidence intervals (e.g., [35.9%, 99.6%] for red pills) reflect the limited statistical power of n = 6 samples and underscore the need for larger validation datasets in future work. Despite this limitation, the overall system accuracy of 94.4% with a 95% confidence interval of [80.9%, 99.3%] demonstrates reliable performance for the tested color categories.

Error Source Analysis for Positioning Accuracy (±0.5 mm):

The total positioning error comprises three primary sources:

- (1)

Camera calibration residual: ≤0.3 mm-arising from fitting errors in the three-point transformation model and non-linearity in lens distortion. This represents the largest error component and could be reduced through advanced calibration methods such as multi-point calibration or checkerboard-based approaches.

- (2)

Optical distortion: ≤0.2 mm-attributed to barrel/pincushion distortion in the MVL-HF1628M-6MPE fixed-focus lens, particularly near the image periphery. This distortion is characteristic of fixed-focal-length lenses and varies with the pill’s position in the field of view.

- (3)

Robot mechanical repeatability: ±0.05 mm-as per the HSR-CR605 manufacturer specifications, representing the inherent positioning variance in the robotic arm under standard operating conditions.

These error components combine approximately as a root-sum-square:

This is consistent with our observed ±0.5 mm total error. The additional margin (0.14 mm) accounts for environmental factors including mechanical vibration from the robot’s motion, thermal expansion of the metal frame structure, and minor variations in the vacuum suction force during grasping operations.

Sorting Efficiency

The experiment used 36 mixed pills (6 each of red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and black) as the objects. The total sorting time was 20 s. The sorting efficiency was calculated using Equation (4):

The average time for a single sorting cycle is 0.555 s, comprising vision processing (291 ms) and robot movement operations (264 ms, including grasping, transfer, and placement actions). This sorting efficiency of 108 pills/min represents an 80% improvement over traditional manual sorting (estimated at 60 pills/min) and can meet the throughput requirements of small- and medium-scale pharmaceutical production lines.

Algorithm Robustness

The experiment verified the reliability of the NCC (Normalized Cross-Correlation) algorithm in matching the geometric features of pills. By setting a reasonable matching score threshold (x ≥ 0.8), the system effectively suppressed the interference of low-confidence matches, significantly improving the accuracy and positioning precision of color sorting. The NCC algorithm demonstrated robust performance across varying illumination conditions (50–1000 lux) and partial occlusion scenarios (overlap ≤ 30%), with only minor degradation in recognition rates for spectrally similar colors (red/orange confusion at 8%).

To empirically justify the selection of NCC and RGB threshold methods over deep learning approaches (e.g., YOLOv5, SegFormer), we conducted preliminary computational benchmarking on a representative subset of 100 pill samples. Processing time measurements on our hardware platform (Intel Core i5-8500, 16GB RAM, no GPU acceleration) demonstrated the following: NCC + RGB thresholding: 291 ms per frame; YOLOv5s (CPU inference mode): 1847 ms per frame (6.35 × slower). This substantial computational advantage is critical for meeting our real-time sorting requirement of <300 ms per cycle. While deep learning methods offer superior generalization in unstructured environments, their computational demands necessitate GPU acceleration (additional hardware cost: RMB 108,000 for NVIDIA RTX 3060), which would increase the total system cost by 73% (from RMB 148,000 to RMB 256,000). Our cost-effective approach deliberately prioritizes real-time performance and economic viability for controlled pharmaceutical environments where lighting and background are standardized. Future work will explore quantized lightweight models (e.g., YOLOv5n with INT8 precision, MobileNetV3-based detectors) as embedded GPU platforms mature.

4.3.3. Stability Test Results

Analysis of

Table 6 shows that the system’s recognition accuracy slightly decreased in the nighttime experiment. In the nighttime experiment, 200 pill samples that could be accurately recognized during the day were tested. There were 10 misrecognitions and 5 missed recognitions, and the recognition accuracy dropped from 98% during the day to 92.5%.

The reduced recognition accuracy at night is mainly attributed to insufficient illumination, which decreases image contrast and detail, making edge and color features less distinguishable. In addition, uneven lighting and surface reflections cause local color distortion, particularly for bright-colored pills such as red and orange. The automatic exposure adjustment of the camera under low light also introduces noise and slight white-balance shifts, further affecting color segmentation accuracy. This phenomenon is consistent with the stability characteristics of robot sorting systems under lighting fluctuations reported by [

4]. Meanwhile, to ensure grasping safety, the robot’s movement speed was moderately reduced in low-light conditions (about 20% lower than during the day), directly resulting in a decrease in overall work efficiency by about 15%. Despite the above performance fluctuations, the system can still maintain the stable operation of its core functions under different lighting conditions during the day and night, indicating that it has a certain level of environmental adaptability and robustness.

5. Conclusions

This work advances pharmaceutical automation through the following three key scientific contributions:

(1) Demonstrating the technical feasibility and economic viability of domestic hardware-software integration (42% cost reduction, RMB 148,000 vs. RMB 256,000, while maintaining comparable performance), (2) establishing quantitative robustness benchmarks through systematic validation under industrially relevant conditions (pill overlap ≤ 30%, illumination 50–1000 lux), and (3) providing a practical implementation framework that bridges the gap between laboratory research and production-line deployment. The integrated system, combining VisionMaster 4.3.0 with the HSR-CR605 robotic arm, achieves end-to-end automation from detection to grasping with validated performance metrics: 95% recognition accuracy, 108 pills/min sorting efficiency, and ±0.5 mm picking precision.

Comprehensive experimental validation under simulated industrial conditions (pill overlap ≤ 30%, dynamic illumination 50–1000 lux) demonstrates the system’s practical effectiveness. The system achieves 95% overall recognition accuracy with 100% accuracy for spectrally distinct colors (yellow, blue, black, green), though red/orange confusion persists at 8% due to RGB channel overlap. Sorting efficiency reaches 108 pills per minute, representing an 80% improvement over traditional manual sorting (≈60 pills/min), with a single-cycle processing time of 0.555 s (vision: 291 ms; robot motion: 264 ms). The system maintains ±0.5 mm picking precision under standard conditions, with error sources systematically characterized as camera calibration residual (≤0.3 mm), optical distortion (≤0.2 mm), and robot repeatability (±0.05 mm).

Performance stability tests reveal environmental sensitivity characteristics that warrant attention in practical deployment. Nighttime experiments demonstrated recognition accuracy degradation to 92.5% (from 98% daytime baseline) due to reduced illumination contrast and increased surface reflection interference, accompanied by a 15% efficiency reduction from conservative speed adjustments. These findings underscore the importance of controlled-lighting environments and highlight the need for adaptive algorithms in industrial applications.

The system’s contributions extend beyond technical implementation to provide practical engineering reference for small- and medium-scale pharmaceutical production lines. By demonstrating the feasibility of domestic hardware-algorithm integration, this research offers both economic viability and technical reliability. The validated sorting efficiency of 108 pills per minute, combined with 95% recognition accuracy and ±0.5 mm positioning precision, confirms that the system meets the operational requirements of pharmaceutical packaging automation. This work establishes a foundation for automated sorting systems in the pharmaceutical industry and validates the strategic merit of adopting domestically manufactured equipment for industrial vision-guided robotic applications.

6. Future Work and Perspectives

Although this study demonstrates successful integration of machine vision and robotic control for automated pill sorting, several extensions remain necessary to enhance system capabilities and broaden applicability. The following research directions address current limitations and expand the system’s potential for industrial deployment.

6.1. Adaptive Visual Recognition Algorithms

The current system exhibits sensitivity to illumination variations (accuracy dropping from 98% daytime to 92.5% nighttime) and color confusion (8% red/orange misclassification rate). Future work will develop adaptive algorithms that automatically adjust recognition parameters under varying environmental conditions. Key directions include the following: (1) implementing dynamic threshold optimization based on real-time illumination monitoring and histogram analysis; (2) exploring HSV or Lab color spaces to improve color discrimination by separating chromaticity from brightness; and (3) integrating lightweight deep learning models (e.g., YOLO variants, SegFormer) to reduce dependence on fixed rule-based parameters while maintaining real-time performance (≤200 ms). These enhancements will improve robustness across diverse lighting conditions and reduce manual recalibration requirements.

6.2. Three-Dimensional Calibration and Grasping

The current three-point planar calibration restricts the system to two-dimensional scenarios without height compensation. Future extensions will incorporate depth sensing (structured light, ToF cameras, or stereo vision) to enable 3D coordinate mapping and implement advanced calibration methods (four-point or checkerboard-based) with Z-axis compensation. Additionally, adaptive trajectory planning algorithms accounting for three-dimensional pill poses will be developed. These capabilities are essential for handling multi-layer pill stacking, bin-picking scenarios, and irregular spatial arrangements encountered in bulk pharmaceutical handling.

6.3. Handling Complex Pill Characteristics

The current validation focuses on round tablets (3–8 mm) with standard coatings. Future research will expand to challenging pharmaceutical formats, such as: (1) irregular shapes (capsules, triangular tablets, embossed surfaces) requiring shape-adaptive end-effectors and contour-based recognition algorithms; (2) transparent/translucent coatings necessitating polarization filtering or multi-angle illumination to suppress edge ambiguity and specular reflection; and (3) highly reflective surfaces (metallic or gel-coated pills) demanding diffuse dome illumination and material-adaptive recognition models. These investigations will systematically evaluate trade-offs between recognition accuracy, processing time, and hardware complexity across diverse product types.

6.4. Long-Term Operational Stability

Transitioning from laboratory validation to industrial deployment requires systematic reliability assessment, including: (1) thermal drift analysis characterizing calibration parameter variations under extended 24/7 operation and temperature fluctuations (15–35 °C), with the development of thermal compensation algorithms; (2) environmental degradation evaluation addressing dust accumulation, lens contamination, and lighting aging in non-cleanroom environments; (3) mechanical wear characterization of vacuum suction components under continuous high-frequency operation (≥100 cycles/hour), establishing the mean time between failures (MTBF) and replacement schedules; and (4) predictive maintenance integrating sensor feedback (vacuum pressure, vision quality metrics, joint currents) with machine learning models for anticipatory failure prevention. Field trials in GMP-compliant pharmaceutical facilities will validate performance under realistic production conditions and quantify economic viability through actual throughput and maintenance cost tracking.

6.5. Scalability and Multi-Robot Coordination

Extending the current single-robot system to multi-robot collaborative sorting is essential for meeting high-throughput industrial demands (>500 pills/min). Key research directions include: (1) network scalability testing under various conditions (Modbus/TCP latency characterization with 2–5 robots sharing a vision system, evaluation of Ethernet bandwidth requirements for concurrent image transmission); (2) workspace coordination algorithms to prevent collision and optimize task allocation (implementing priority-based arbitration for shared pick zones, developing dynamic load balancing based on real-time throughput monitoring); (3) hardware compatibility verification with alternative robotic platforms (testing coordinate transformation matrices with different kinematics configurations, validating communication protocols with third-party controllers); and (4) centralized vs. distributed control architecture trade-offs (comparing computation distribution between edge devices and central server, quantifying system resilience to individual component failures). Preliminary analysis suggests that a 3-robot configuration could achieve 280–320 pills/min with proper workspace partitioning, though comprehensive validation requires dedicated pilot deployment.

6.6. Broader Academic Contributions

These research directions will strengthen the academic impact by (1) bridging integration-oriented engineering with algorithmic innovation through adaptive learning mechanisms; (2) contributing quantitative robustness metrics across diverse environmental conditions, material properties, and operational scenarios; (3) providing systematic comparisons between traditional vision methods and deep learning approaches in pharmaceutical sorting contexts; and (4) establishing best-practice guidelines for domestic hardware-algorithm co-design, including performance validation protocols, cost-benefit analysis frameworks, and quality assurance methodologies ensuring industrial-grade reliability.

The ultimate goal is to evolve from a proof-of-concept system toward a comprehensive framework balancing performance, reliability, adaptability, and economic viability for real-world pharmaceutical manufacturing environments. By systematically addressing current limitations while expanding functional capabilities, this research will advance both theoretical understanding and practical implementation of intelligent sorting systems in pharmaceutical automation [

26,

27].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.T. and J.K.; methodology, J.K.; software, J.K.; validation, X.T., J.K. and W.W.; formal analysis, W.W.; investigation, J.K.; resources, X.T.; data curation, J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K.; writing—review and editing, X.T., and W.W.; visualization, J.K.; supervision, X.T., and W.W.; project administration, W.W.; funding acquisition, X.T.; hardware setup, J.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Research on Intelligent Monitoring Technology of PitayaGrowth Cycle Based on Machine Vision (grant no. 2023ZDZX4031), School-Enterprise Joint Laboratory for High-End Digital Manufacturing Talent Cultivation under the 2023 Teaching Quality and Teaching Reform Project Construction Program for Undergraduate Universities in Guangdong Province (grant no. 44).

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kwon, H.J.; Kim, H.G.; Lee, S.H. Pill Detection Model for Medicine Inspection Based on Deep Learning. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, C.; Ulrich, M.; Wiedemann, C. Machine Vision Algorithms and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Hu, G.; Lu, L. Research on an Automatic Sorting System Based on Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Seminar on Computer Science and Engineering Technology, SCSET, Indianapolis, IN, USA, 8–9 January 2022; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, V.D.; Hanh, L.D.; Phuong, L.H.; Duy, D.A. Design and Development of Robot Arm System for Classification and Sorting Using Machine Vision. FME Trans. 2022, 50, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, M. YOLOv1 to v8: Unveiling each variant—A comprehensive review of YOLO. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 42816–42833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Yan, H.; He, Z.; Li, W.; Zang, W.; Zhu, C. Research and Design of Machine Vision-Based Workpiece Defect Sorting Robot. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Robotics, ICICR, Dalian, China, 12–14 April 2024; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi-Alden, K.; Omid, M.; Firouz, M.S.; Nasiri, A. A Machine Vision-Intelligent Modelling Based Technique for in-Line Bell Pepper Sorting. Inf. Process. Agric. 2023, 10, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Chen, C.; Jiang, H. Design and Implementation of Sorting System Based on Machine Vision. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Big Data Analytics, ICBDA, Guangzhou, China, 4–6 March 2022; pp. 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Zhang, L.; Niu, Y.; Fan, X. Design and Key Technology Analysis of Coal-Gangue Sorting Robot. Coal Sci. Technol. 2022, 50, 232–238. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Fengshou, Z.; Gaoshuai, Z.; Yuanhao, Q.; Aohui, H.; Qingyang, D. Correction: Enhanced YOLOv8 for Efficient Parcel Identification in Disordered Logistics Environments. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2025, 18, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhong, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Q.M.J.; Ge, J.; Wang, Y. Automated Machine Vision System for Liquid Particle Inspection of Pharmaceutical Injection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2018, 67, 1278–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Miao, P.; Miao, K.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z. An Online Automatic Sorting System for Defective Ginseng Radix et Rhizoma Rubra Using Deep Learning. Chin. Herb. Med. 2023, 15, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mageshkumar, G.; Kasthuri, N.; Tamilselvan, K.; Suthagar, S.; Sharmila, A. Design of Industrial Data Monitoring Device Using IoT through Modbus Protocol. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 1392–1396. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Ramírez-Gómez, Á.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y. Intelligent and Precise Textile Drop-Off: A New Strategy for Integrating Soft Fingers and Machine Vision Technology. Textiles 2025, 5, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Xu, S.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Gong, D.; Qin, Z.; Dong, H.; Yang, H. Strong Radiation Field Online Detection and Monitoring System with Camera. Sensors 2022, 22, 2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X. Research on Medicine Label Recognition and Sorting Based on Machine Vision. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- BT.601; Studio Encoding Parameters of Digital Television for Standard 4:3 and Wide-Screen 16:9 Aspect Ratios. ITU-R: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995. Available online: https://www.itu.int/rec/R-REC-BT.601/ (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Yao, M. Digital Image Processing; DynoMedia Inc.: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Design of Industrial Robot Sorting System Based on Machine Vision. China Mech. 2024, 28, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, J.-C.; Han, T.H. Fast Normalized Cross-Correlation. Circuits Syst. Signal Process. 2009, 28, 819–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Xu, R.; Ma, X.; Hu, S.; Bao, X. Fast Calibration Method for Base Coordinates of the Dual-Robot Based on Three-Point Measurement Calibration Method. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, C. Calibration of Laser Beam Direction for Inner Diameter Measuring Device. Sensors 2017, 17, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Durocher, H.J.; Zhang, X. Automatic Robot Hand-Eye Calibration Enabled by Learning-Based 3D Vision. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2024, 110, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Virtual, 6–14 December 2021. [Google Scholar]

- GB 50457-2019; Code for Design of Pharmaceutical Industry Clean Room. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019. Available online: https://www.chinesestandard.net/PDF/English.aspx/GB50457-2019 (accessed on 27 September 2025).

- Culjak, I.; Abram, D.; Pribanic, T.; Dzapo, H.; Cifrek, M. A Brief Introduction to OpenCV. In Proceedings of the 35th International Convention MIPRO, Opatija, Croatia, 21–25 May 2012; pp. 1725–1730. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Ye, W.; Wang, Y. Design of Machine Vision Defect Detecting System Based on Halcon. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Mechanical, Electrical, Electronic Engineering & Science (MEEES 2018), Chongqing, China, 26–27 May 2018; pp. 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).