Abstract

Image classification is central to computer vision, supporting applications from autonomous driving to medical imaging, yet state-of-the-art convolutional neural networks remain constrained by heavy floating-point operations (FLOPs) and parameter counts on edge devices. To address this accuracy–efficiency trade-off, we propose a unified lightweight framework built on a pruning-aware coordinate attention block (PACB). PACB integrates coordinate attention (CA) with L1-regularized channel pruning, enriching feature representation while enabling structured compression. Applied to MobileNetV3 and RepVGG, the framework achieves substantial efficiency gains. On GTSRB, MobileNetV3 parameters drop from 16.239 M to 9.871 M (–6.37 M) and FLOPs from 11.297 M to 8.552 M (–24.3%), with accuracy improving from 97.09% to 97.37%. For RepVGG, parameters fall from 7.683 M to 7.093 M (–0.59 M) and FLOPs from 31.264 M to 27.918 M (–3.35 M), with only ~0.51% average accuracy loss across CIFAR-10, Fashion-MNIST, and GTSRB. Complexity analysis further confirms PACB does not increase asymptotic order, since the additional CA operations contribute only lightweight lower-order terms. These results demonstrate that coupling CA with structured pruning yields a scalable accuracy–efficiency trade-off under hardware-agnostic metrics, making PACB a promising, deployment-ready solution for mobile and edge applications.

1. Introduction

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have achieved dominant performance in image classification [1], leading to breakthroughs across advanced applications like autonomous driving and medical diagnosis. However, this success is heavily reliant on models with millions of parameters and substantial computational demands. This complexity poses a critical challenge for deployment in resource-constrained environments, such as mobile devices, embedded systems, and edge platforms, where power, memory, and latency budgets are severely limited [2]. The core research tension in this field is the persistent need to develop models that strike an optimal balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency [3,4,5].

Efforts to mitigate the excessive demands of deep CNNs fall into two major categories that aim to enhance deployability. The first involves the design of lightweight network architectures, which are fundamentally efficient. Representative work includes SqueezeNet [3], which pioneered methods for reducing model size while maintaining accuracy; Google’s MobileNet series [6,7,8], which employs depthwise separable convolutions and inverted residuals; ShuffleNet V2 [4], which provides robust guidelines for practical hardware efficiency; and RepVGG [9], which utilizes structural reparameterization to accelerate inference. More recently, EfficientNet [5] offered a unified scaling approach to systematically balance depth, width, and resolution for optimal performance. The second category focuses on model optimization techniques that refine existing architectures. These include attention mechanisms [10,11], which enhance feature representation by enabling models to focus on salient regions; structural pruning [12,13,14,15], which removes redundancy to reduce memory footprint and floating-point operations (FLOPs); knowledge distillation [16], which transfers knowledge from a large teacher model to optimize training; and quantization [17], which accelerates runtime by reducing numerical precision, e.g., to INT8. Contemporary state-of-the-art models often employ hybrid strategies that combine these largely orthogonal techniques to maximize deployment efficiency.

While these strategies have advanced efficiency, their isolated or simple hybrid application often leads to limitations. Architectural simplifications alone often compromise accuracy. Conversely, complex hybrid approaches, such as knowledge distillation or quantization, frequently require additional training stages or specialized hardware support, which complicates the deployment pipeline. This study addresses the need for a streamlined, integrated framework focused purely on structural optimization—the permanent alteration of the network architecture. Our objective is to systematically combine representation enhancement with structural compression in a co-optimized manner to achieve efficiency gains beyond individual techniques. Crucially, this framework delivers an efficient, hardware-agnostic, and deployment-ready baseline, achieved without resorting to expensive neural architecture search (NAS) [18,19,20] or relying on orthogonal techniques such as knowledge distillation or quantization in the initial compression phase.

Motivated by the goal of constructing highly efficient, deployment-ready models, this study proposes a novel framework that integrates the position-sensitive coordinate attention (CA) mechanism [10] with L1-regularized channel pruning [15] within lightweight architectures (MobileNetV3 [8] and RepVGG [9]). By embedding a pruning-aware coordinate attention block (PACB) into the baseline models, we aim to demonstrate that this synergistic approach significantly improves the accuracy-efficiency trade-off, enabling substantial reduction in computational resources while maintaining competitive predictive performance.

The main contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- Unified lightweight framework: We propose a novel lightweight framework that systematically integrates the position-sensitive CA mechanism with L1-regularized structured channel pruning into a single, co-optimized PACB.

- Rigorous empirical and efficiency demonstration: We provide a rigorous empirical demonstration that the combined CA-pruning strategy achieves superior efficiency, reporting substantial reductions in parameters (up to 6.53 M) and FLOPs (24.3%), thereby proving the practical effectiveness of the framework.

- Critical architectural analysis: We perform a comparative analysis, particularly examining the CA mechanism’s architectural limitations on low-resolution datasets, providing crucial insights for the future design of position-aware attention modules in lightweight models.

- Generalizability across baselines: We demonstrate that this integrated methodology offers a robust and generalizable optimization paradigm, showing consistent performance gains when applied to two distinct lightweight architectures: MobileNetV3 and RepVGG.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces the proposed lightweight image classification framework, which integrates the CA mechanism, channel pruning, and lightweight network design, along with the algorithmic complexity analysis, a four-stage implementation workflow, and the pseudocode of the core PACB. Section 3 describes the experimental setup and presents the quantitative results, including ablation studies and comparative evaluations. Section 4 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Proposed Lightweight Image Classification Framework

To rigorously assess the generalizability of the proposed approach, we conduct comparative experiments on three benchmark datasets with markedly different characteristics: CIFAR-10 [21], Fashion-MNIST [22], and GTSRB [23]. Leveraging multiple datasets offers three distinct advantages: (i) enabling a comprehensive evaluation of adaptability to diverse image features, resolutions, and semantic complexities; (ii) facilitating assessment of feature extraction capability across varied object categories and visual domains; and (iii) providing insight into stability under differing data volumes. To establish a consistent evaluation basis, we adopt three primary indicators—classification accuracy, the number of trainable parameters, and FLOPs—which serve as the foundation for the subsequent complexity analysis and experimental validation.

2.1. Datasets

2.1.1. CIFAR-10 [21]

The CIFAR-10 dataset comprises 60,000 color images evenly distributed across 10 distinct classes, with 6000 images per class. Each image is an RGB color picture with a spatial resolution of 32 × 32 pixels. The dataset encompasses a diverse range of object categories, including airplane, automobile, bird, cat, deer, dog, frog, horse, ship, and truck. These images provide a compact yet challenging benchmark for evaluating image classification models, owing to their low resolution, balanced class distribution, and variability in object appearance and background context.

2.1.2. Fashion-MNIST [22]

The Fashion-MNIST dataset consists of 70,000 grayscale images of fashion products, evenly distributed across 10 categories, with 7000 images per category. Each image has a spatial resolution of 28 × 28 pixels and represents one of the following classes: T-shirt/top, trouser, pullover, dress, coat, sandal, shirt, sneaker, bag, and ankle boot. Designed as a more challenging drop-in replacement for the original MNIST handwritten digit dataset, Fashion-MNIST serves as a widely adopted benchmark for evaluating image classification models, particularly in scenarios involving low-resolution, single-channel inputs.

2.1.3. GTSRB [23]

The GTSRB comprises over 50,000 RGB images of traffic signs, spanning 43 distinct classes. The images vary in resolution, illumination, and viewing conditions, reflecting the complexity of real-world traffic environments. Each class corresponds to a specific traffic sign category, such as speed limits, prohibitions, warnings, and mandatory instructions. The dataset’s diversity in scale, perspective, and background clutter makes it a rigorous benchmark for assessing both the accuracy and robustness of image classification models in safety-critical applications.

2.2. Lightweight Networks

2.2.1. MobileNetV3 [8]

MobileNetV3 employs depthwise separable convolutions to reduce computational complexity, incorporates an inverted residual structure, and adopts the h-Swish activation function to enhance feature extraction efficiency. Its architecture comprises linear bottlenecks and an SENet attention module. Owing to its compact design and strong representational capability, MobileNetV3 is well-suited for image classification tasks.

2.2.2. RepVGG [9]

RepVGG employs a structural reparameterization strategy that transforms a multi-branch training architecture into a single 3 × 3 convolutional layer for inference, thereby improving computational efficiency. During training, each block consists of parallel 3 × 3 and 1 × 1 convolutions along with an identity mapping. At inference time, these branches are equivalently merged into a single branch, enabling streamlined computation and facilitating efficient deployment.

2.3. CA [10]

CA is a lightweight attention mechanism that decomposes channel attention into two complementary one-dimensional encoding processes along the horizontal and vertical spatial directions. This design allows the network to capture long-range dependencies along one dimension while retaining precise positional information along the other. The resulting direction-aware attention maps are applied to the input features to selectively emphasize informative regions. CA modules are inserted after the convolutional blocks of the baseline architectures, thereby enhancing the representation of salient regions with only a negligible increase in computational overhead. In our framework, CA will later be uniformly integrated into the repeating blocks of MobileNetV3 and RepVGG (see Section 2.7).

Mathematically, the input feature map in (where , , and denote the channels, height, and width, respectively) is first encoded into two one-dimensional feature maps through average pooling kernels of size (, ) and (, ) along the horizontal and vertical directions, yielding and , respectively. We define as the element value of the input feature map at channel , height , and width , where , , and . Based on this definition, the aggregated outputs of the -th channel at a given height index (averaged over the width dimension) and at a given width index (averaged over the height dimension) are given by

and

respectively.

These aggregated maps are concatenated and transformed by a shared convolution (a linear transformation) followed by a non-linear activation (e.g., ReLU), resulting in an intermediate feature in , where is the reduction ratio. This intermediate feature is calculated as:

is then split back into and . These split features are transformed by two separate convolutions and (linear transformations), followed by the sigmoid activation , to produce the attention weights and :

The output feature map is obtained by element-wise multiplication, and its element value, denoted as , is given by

where and denote the attention weight elements at channel for the respective height and width coordinates. This formulation rigorously embeds positional information, thereby enhancing the ability of CNNs to capture and process spatially relevant features.

2.4. Channel Pruning [15]

Channel pruning is realized by leveraging the learnable scaling factors in batch normalization (BN) layers and applying L1 regularization to induce sparsity, thereby identifying and removing channels with minimal contribution to the final prediction. The procedure follows three sequential stages: (i) sparsity-inducing training, where L1-regularized scaling factors drive uninformative channels toward zero; (ii) threshold-based channel removal, in which channels with scaling factors below a predefined magnitude are pruned; and (iii) fine-tuning of the compact model to recover potential performance loss. In this study, channel pruning is applied to the trained networks, effectively reducing parameters and FLOPs while preserving competitive accuracy.

The pruning process is guided by the L1-regularized training objective:

where is the classification loss, is the network function, denotes the input sample, denotes the corresponding ground-truth label, denotes the BN scaling factor associated with the -th channel, is the set of all trainable weights excluding the BN scaling factors, and is the sparsity-inducing coefficient controlling the strength of the L1 regularization. The term represents the L1 norm over the set of all BN scaling factors . This regularization encourages uninformative channels to vanish by shrinking their scaling factors toward zero, thereby enabling their subsequent removal.

2.5. Algorithmic Complexity Analysis

We define and as the input and output channel counts of a convolutional layer, respectively, and let denote the kernel size. For a standard convolutional layer, the computational complexity is . MobileNetV3 reduces this cost by employing depthwise separable convolutions, which decompose the operation into a depthwise part with complexity and a pointwise part with complexity . In RepVGG, after structural reparameterization, each block is equivalent to a single convolution, thus retaining the same order of complexity as the standard convolution. The CA module involves global pooling along spatial dimensions and two convolutions, with complexity . After pruning, the overall complexity for PACB based on MobileNetV3 becomes , where , , and denote the effective input, output, and intermediate channel counts after pruning, respectively. For PACB based on RepVGG, the complexity is . In both cases, the dominant terms remain the pruned convolutional operations, while the CA module contributes only lower-order terms that do not affect the overall asymptotic order.

Consequently, the proposed framework does not introduce higher-order complexity beyond the baseline architectures. While CA is integrated into every repeating block, its additional operations—global pooling and 1 × 1 convolutions—remain lightweight compared to the dominant convolutional terms. After pruning, the effective channel counts are further reduced, leading to a net decrease in overall computational cost while preserving the representational benefits of CA. Thus, the uniform placement of CA maintains the lightweight principle without altering the asymptotic order of complexity.

2.6. Complementarity of CA and Channel Pruning

The synergistic design of our framework is motivated by the research gap highlighted in the Introduction: the limitations of applying enhancement and compression techniques in isolation. The integration of CA and channel pruning within the PACB provides a balanced trade-off between representational enhancement and structural efficiency. CA enriches feature encoding by embedding direction-aware, position-sensitive attention into the convolutional layers, thereby improving the discriminative power of the network. In parallel, channel pruning minimizes computational cost by systematically removing uninformative channels identified through L1-regularization of the BN scaling factors. By co-optimizing these two components—leveraging CA to enhance feature representations prior to sparsity-inducing training—the PACB ensures that the model compresses only channels that are genuinely redundant, resulting in lightweight models that are both performance-oriented and deployment-ready for resource-constrained environments.

2.7. Implementation Workflow

The proposed framework follows a four-stage workflow:

- Architecture integration: Embed the CA module after the convolutional layers of the baseline models (creating the ‘Baseline+CA’ architecture). The strategic placement of the CA module is critical. In both MobileNetV3 and RepVGG, we integrate CA into every repeating feature extraction block (bottlenecks or layers). By adopting this uniform placement strategy, we eliminate the need for computationally expensive NAS to determine layer-specific attention positions, thereby adhering to the lightweight principle of minimizing both design complexity and computational overhead. Although alternative placements (e.g., inserting CA only in early or late stages) could in principle be explored, we adopt a uniform integration strategy for both simplicity and effectiveness. This uniform placement also ensures architectural consistency and facilitates deployment across different platforms.

- Sparsity-inducing training—Train the integrated (Baseline+CA) model, applying L1 regularization to the BN layer scaling factors as defined in Equation (7) to encourage channel sparsity.

- Pruning and fine-tuning—After sparsity training, remove channels whose scaling factors are below a predefined threshold. Subsequently, fine-tune the pruned, smaller network to recover any performance loss.

- Evaluation—Assess the final models (Baseline, Baseline+CA, and the pruned Baseline+CA) in terms of classification accuracy, parameter count, and FLOPs.

2.8. Pseudocode for the PACB

To illustrate the unique system architecture integrating the core components, the following pseudocode formally presents the operational flow of the PACB. The PACB is designed to augment the standard feature extraction blocks (e.g., MobileNetV3 Bottleneck or RepVGG structural block). The core architectural contribution lies in maintaining the BN scaling factors for pruning within the block structure where the CA mechanism is inserted. The pseudocode describing the operational flow of the PACB is presented in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: Pseudocode of PACB. |

|

3. Experimental Results

To explicitly address the challenges of image classification on resource-constrained devices, our experiments are designed with three considerations: (i) heterogeneous datasets (CIFAR-10, Fashion-MNIST, and GTSRB) are selected to reflect varying levels of complexity and domain diversity; (ii) lightweight baseline architectures (MobileNetV3 and RepVGG) are chosen to highlight the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency; and (iii) evaluation incorporates not only classification accuracy, parameter count, and FLOPs, but also inference latency, ensuring that the proposed framework is validated in terms of predictive performance, model compactness, and real-time deployment feasibility. These metrics jointly reflect both accuracy and efficiency, thereby directly addressing the efficiency and lightweight aspects emphasized in the title.

3.1. Experimental Environment Setup and Implementation Details

All experiments were conducted on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7-9700K CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 GPU. The models were implemented using the PyTorch 1.13.1 framework under the Windows 10 operating system. The detailed hardware and software configurations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental environment configuration.

For training, all models were optimized using stochastic gradient descent with momentum 0.9 and weight decay 5 × 10−4. The initial learning rate was set to 0.1 and decayed by a factor of 0.1 at epochs 100 and 150. Each model was trained for 200 epochs with a batch size of 128. Standard data augmentation techniques were applied, including random cropping with 4-pixel padding, random horizontal flipping, and per-channel normalization. For our experiments, following [15], the pruning threshold was set by sorting the BN scaling factors and pruning a predefined percentage of channels, such that approximately 70% of channels were retained per layer. The sparsity-inducing coefficient for L1 regularization on BN scaling factors was set to 1 × 10−4.

3.2. Ablation Study on MobileNetV3 Variants

3.2.1. Overall Performance Comparison of MobileNetV3 Variants

Starting from the baseline MobileNetV3 architecture, the CA module and channel pruning technique were sequentially incorporated to assess their impact on model performance, with the results summarized in Table 2. All accuracy values are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five independent runs. On the CIFAR-10 dataset, replacing the SE attention module in the bottleneck layers with the CA module reduced detection accuracy by 7.28% compared with the SE-based baseline, while decreasing the parameter count by 4.64 M. When channel pruning was subsequently applied, accuracy dropped by 0.72%, while parameters were reduced by 1.89 M and FLOPs decreased by 19.6%, indicating that a slight accuracy loss can yield substantial gains in compactness and efficiency. On Fashion-MNIST, incorporating CA improved accuracy by 0.55% and reduced parameters by 4.64 M; subsequent pruning decreased accuracy by 3.22% while further reducing parameters by 1.89 M and FLOPs by 26.6%, again achieving a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off. For GTSRB, CA increased accuracy by 1.72% and reduced parameters by 4.64 M, while pruning caused a 1.44% accuracy drop, reduced parameters by 1.72 M, and decreased FLOPs by 26.6%. Interestingly, the introduction of the CA module led to a slight performance drop on CIFAR-10, in contrast to the consistent improvements observed on Fashion-MNIST and GTSRB. We attribute this to the relatively simple and homogeneous visual patterns in CIFAR-10, where the additional channel attention may over-emphasize local correlations and reduce the diversity of learned representations. This effect can be interpreted as a mild form of overfitting, as the model becomes more specialized to training features without yielding generalization gains. A similar phenomenon has been reported in prior studies, where attention modules occasionally degrade performance on small-scale datasets with limited complexity [24,25]. Across all datasets, these results demonstrate that modest accuracy reductions can deliver significant improvements in model compactness and computational efficiency, while the reported standard deviations confirm that the observed trends are statistically consistent and reproducible.

Table 2.

Performance of MobileNetV3 variants on CIFAR-10, Fashion-MNIST, and GTSRB. MobileNetV3_CA denotes the MobileNetV3 architecture with the SE attention module in the bottleneck layers replaced by the CA module, and MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned refers to MobileNetV3_CA further enhanced through channel pruning. Acc (%) denotes the classification accuracy, calculated as (correctly classified samples/total samples) × 100. Accuracy values are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five independent runs. Params (M) denotes the total number of trainable parameters divided by 106. FLOPs (M) denotes the total number of floating-point operations for a single forward pass divided by 106.

3.2.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis of MobileNetV3_CA and MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned

While Table 2 summarizes the overall performance metrics of the MobileNetV3 variants across the three datasets, these aggregate figures alone do not fully capture the nature of the classification errors. To gain deeper insight into how the CA module and subsequent channel pruning affect class-level performance, confusion matrices for MobileNetV3_CA and MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned were examined on CIFAR-10, Fashion-MNIST, and GTSRB. This analysis reveals not only the correctly classified samples but also the specific patterns of misclassification, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the trade-offs introduced by the architectural modifications.

For this analysis, 1000 test images were randomly sampled from each class in every dataset to ensure a consistent evaluation size. To enable fair comparison across datasets with differing numbers of classes, the GTSRB dataset was consolidated from its original 43 categories into 10 super-classes, following the functional grouping methodology described in prior work [26]. This consolidation preserves essential semantic distinctions while mitigating class imbalance and facilitating cross-dataset comparisons.

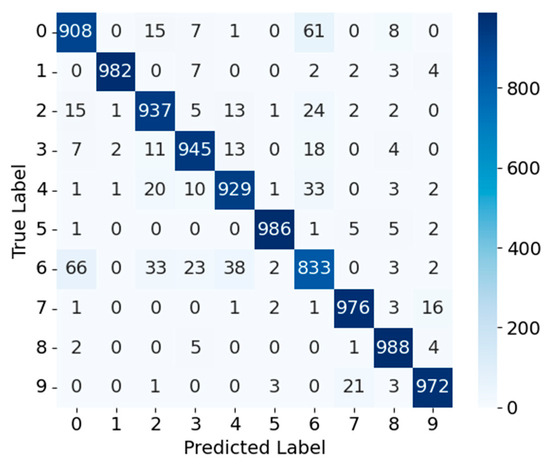

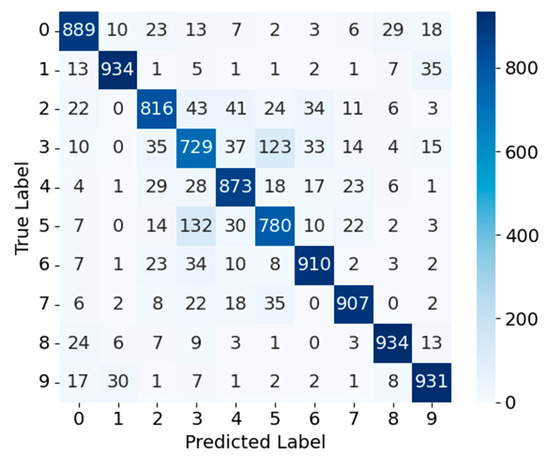

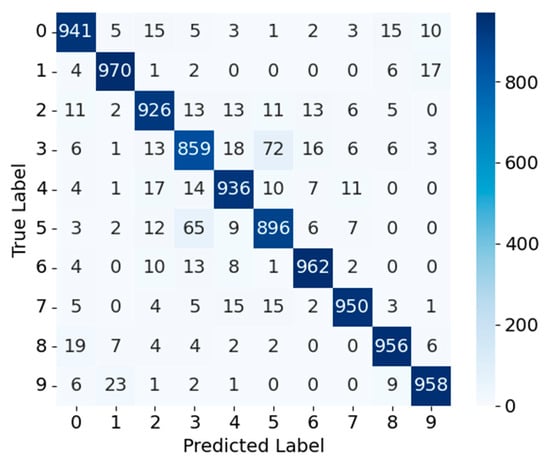

CIFAR-10—Figure 1 and Figure 2 present the confusion matrices for MobileNetV3_CA and MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned on the CIFAR-10 dataset, respectively. For MobileNetV3_CA, most samples are concentrated along the diagonal, indicating high classification accuracy; for example, class 0 has 908 correctly classified samples and class 1 has 982. Although class 6 exhibits some misclassifications—primarily into classes 0, 2, and 4—the overall number of errors is small, and the model maintains strong classification performance. In contrast, MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned shows a marked decrease in correct classifications for several classes (e.g., class 2: 937 → 816, class 3: 945 → 729, class 5: 986 → 780) and a clear increase in misclassifications, particularly for classes 2 and 3 being confused with other categories. These results indicate that while pruning substantially reduces model complexity, it also weakens feature representation, thereby increasing confusion between visually similar object categories. Consequently, pruning strength should be carefully tuned to balance lightweight design and classification accuracy, particularly when mitigating confusion among visually similar objects, ensuring a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 1.

Confusion matrix of MobileNetV3_CA on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

Figure 2.

Confusion matrix of MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

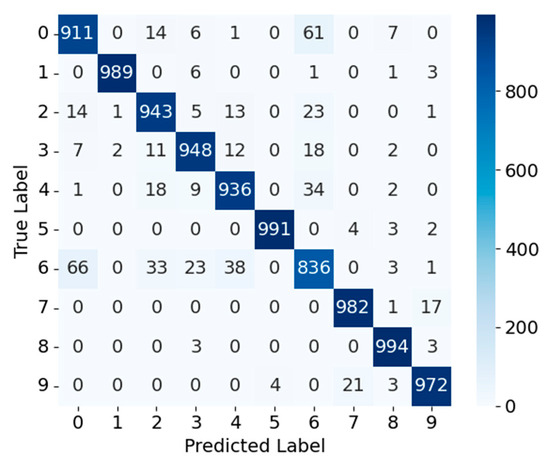

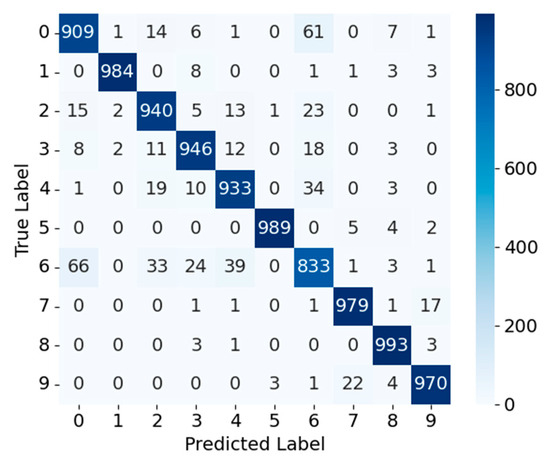

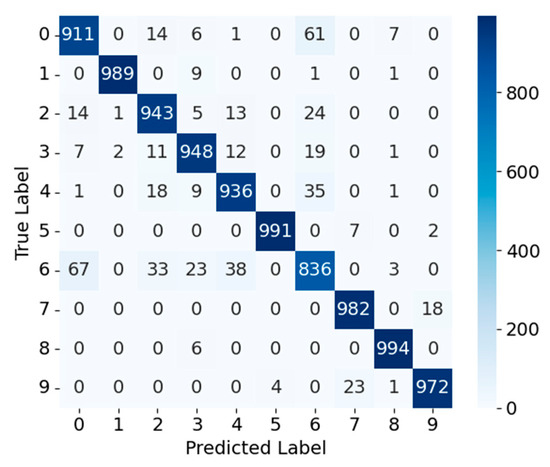

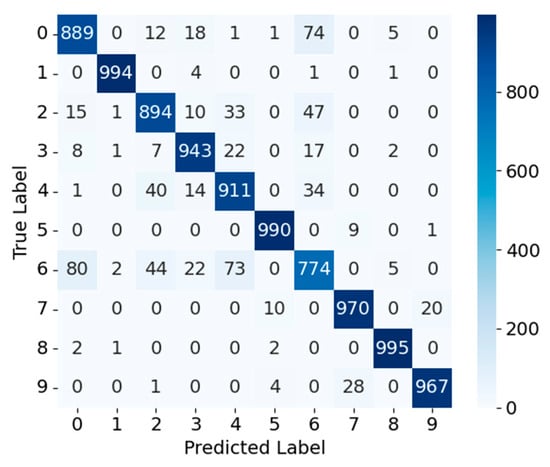

Fashion-MNIST—Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the confusion matrices for MobileNetV3_CA and MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned on the Fashion-MNIST dataset. For MobileNetV3_CA, most samples are concentrated along the diagonal, reflecting high classification accuracy; for instance, class 0 and class 1 have 911 and 989 correctly classified samples, respectively. A notable exception is class 6, which exhibits higher misclassification rates into classes 0, 4, and 2, indicating difficulty in distinguishing structurally similar apparel items. After pruning, the MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned model maintains comparable overall performance, with class 0 and class 1 achieving 909 and 984 correct classifications, respectively. The correct classification counts for other classes remain largely unchanged, and the misclassification patterns of class 6 into classes 0, 4, and 2 are similar to those observed before pruning. Overall, channel pruning exerts minimal impact on most categories, with only a modest reduction in fine-grained discrimination for visually similar classes. Consequently, pruning strength should be carefully tuned to balance lightweight design and classification accuracy, ensuring a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 3.

Confusion matrix of MobileNetV3_CA on the Fashion-MNIST dataset.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix of MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned on the Fashion-MNIST dataset.

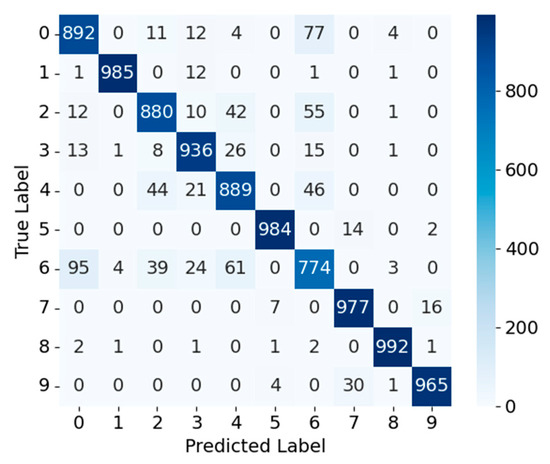

GTSRB—Figure 5 and Figure 6 present the confusion matrices for MobileNetV3_CA and MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned on the GTSRB dataset (consolidated into 10 super-classes). For MobileNetV3_CA, most predictions align along the diagonal, indicating strong classification performance; for example, class 0 and class 1 achieve 941 and 970 correct classifications, respectively. Some categories, such as class 3, exhibit noticeable misclassifications—primarily into class 5—suggesting that certain traffic signs share similar visual features, leading to occasional confusion. After pruning, the MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned model maintains high accuracy for most classes, with several categories even showing improved performance compared to the unpruned model (e.g., class 1: 970 → 989, class 7: 950 → 982, class 8: 956 → 994, class 9: 958 → 972). Class 4 remains stable in correct classifications (936 → 936) but shows reduced misclassification rates. However, class 6 experiences a substantial drop in correct classifications (962 → 836) and a marked increase in confusion with other categories, indicating that pruning has a more pronounced impact on fine-grained feature discrimination for this class. Consequently, pruning strength should be carefully tuned to balance lightweight design and classification accuracy, particularly for traffic sign categories with subtle visual differences, ensuring a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix of MobileNetV3_CA on the GTSRB dataset.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix of MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned on the GTSRB dataset.

Cross-Dataset Summary—Across the three datasets, the confusion matrix analysis shows a consistent pattern in how the CA module and subsequent channel pruning influence MobileNetV3’s compact, depthwise-separable architecture. In all cases, MobileNetV3_CA delivers high classification accuracy, with predictions predominantly aligned along the diagonal and only minor confusion between visually or structurally similar categories. Channel pruning largely retains this performance, and in some categories even improves accuracy—likely due to reduced overfitting and better generalization. Nevertheless, a small subset of classes with high intra-class variability or subtle inter-class similarities (e.g., CIFAR-10 classes 2 and 3, Fashion-MNIST class 6, GTSRB class 6) exhibit increased misclassification rates after pruning. These findings suggest that while pruning effectively reduces parameters and FLOPs, its effect on fine-grained feature discrimination is dataset- and class-dependent. Careful calibration of pruning intensity is therefore essential to preserve MobileNetV3’s efficiency advantages without compromising its ability to separate closely related categories.

3.3. Ablation Study on RepVGG Variants

3.3.1. Overall Performance Comparison of RepVGG Variants

Starting from the baseline RepVGG architecture, the CA module and channel pruning technique were sequentially incorporated to assess their impact on model performance, with the results summarized in Table 3. All accuracy results are presented as mean ± standard deviation across five independent runs. On the CIFAR-10 dataset, adding CA increased detection accuracy by 0.86% with a marginal parameter increase of 0.21 M. When channel pruning was subsequently applied, accuracy dropped by 0.42%, while parameters were reduced by 0.83 M and FLOPs decreased by 14%, indicating that a slight accuracy loss can deliver substantial reductions in model size and computational cost. On Fashion-MNIST, CA improved accuracy by 0.02% with a parameter increase of 0.21 M; subsequent pruning decreased accuracy by 0.17% while reducing parameters by 0.84 M and FLOPs by 11%, again achieving a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off. For GTSRB, CA increased accuracy by 0.18% with a parameter increase of 0.21 M, while pruning caused a 0.93% accuracy drop, reduced parameters by 0.80 M, and decreased FLOPs by 11%. Across all datasets, these results demonstrate that modest accuracy reductions can yield significant gains in model compactness and computational efficiency, while these deviations confirm that the performance differences are statistically consistent and reproducible.

Table 3.

Performance of RepVGG variants on CIFAR-10, Fashion-MNIST, and GTSRB. RepVGG_CA denotes the RepVGG architecture with the CA module incorporated, and RepVGG_CA_Pruned refers to RepVGG_CA further enhanced through channel pruning. Accuracy values are reported as mean ± standard deviation over five independent runs. Performance indicators (Acc, Params, FLOPs) are defined as in Table 2.

3.3.2. Confusion Matrix Analysis of RepVGG_CA and RepVGG_CA_Pruned

Following the performance results presented in Table 3, we conducted a class-wise error analysis to investigate how the CA module and subsequent channel pruning influence RepVGG’s classification behavior. This analysis moves beyond aggregate accuracy, parameter counts, and FLOPs to uncover patterns of correct cl and systematic misclassification. Given RepVGG’s plain, structured convolutional design, such an investigation is particularly relevant for assessing whether architectural modifications affect its ability to discriminate between visually similar categories—a capability that may be sensitive to pruning.

To capture these effects more precisely, confusion matrices for RepVGG_CA and RepVGG_CA_Pruned were generated for CIFAR-10, Fashion-MNIST, and GTSRB. As outlined in Section 3.2.2, a uniform sampling of 1000 test images per class was applied across all datasets, and the GTSRB dataset was consolidated from 43 categories into 10 super-classes using the functional grouping approach in [26]. This preprocessing standardizes evaluation conditions, mitigates class imbalance, and ensures that differences in classification patterns are attributable to model architecture rather than dataset heterogeneity, thereby enhancing the interpretability of the comparative analysis.

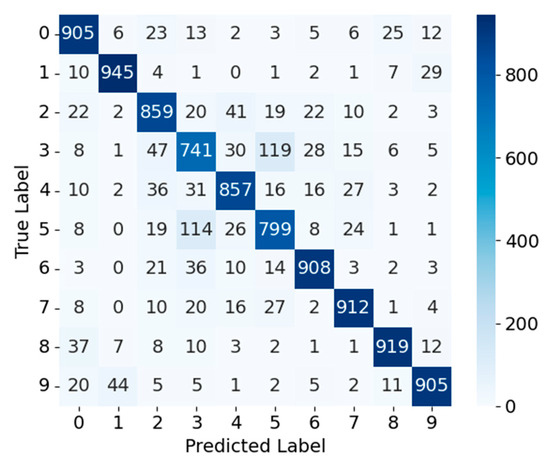

CIFAR-10—Figure 7 and Figure 8 present the confusion matrices for RepVGG_CA and RepVGG_CA_Pruned on the CIFAR-10 dataset, respectively. For RepVGG_CA, most samples are concentrated along the diagonal, indicating high classification accuracy; for example, class 0 has 905 correctly classified samples and class 1 has 945. Misclassifications are relatively minor, with only limited confusion between visually similar categories. After pruning, RepVGG_CA_Pruned maintains similar performance for most classes (e.g., class 0: 897, class 1: 947) but shows a slight increase in confusion for certain categories, such as class 3 being misclassified as class 5, and increased confusion between classes 2 and 4. These changes suggest that pruning may slightly weaken fine-grained feature discrimination for visually similar categories. Consequently, pruning strength should be carefully tuned to balance lightweight design and classification accuracy, particularly when mitigating confusion among visually similar objects, ensuring a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix of RepVGG_CA on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix of RepVGG_CA_Pruned on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

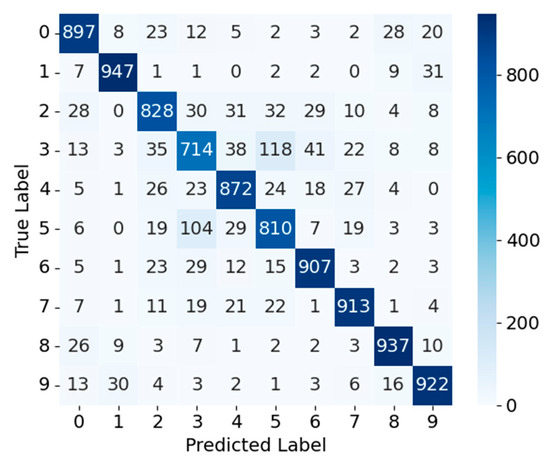

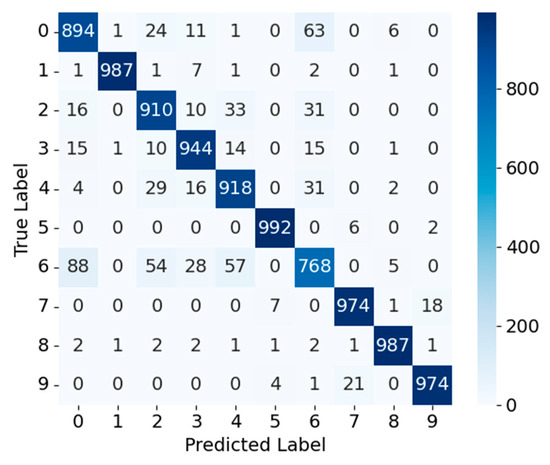

Fashion-MNIST—Figure 9 and Figure 10 show the confusion matrices for RepVGG_CA and RepVGG_CA_Pruned on the Fashion-MNIST dataset. For RepVGG_CA, most samples are concentrated along the diagonal, reflecting high classification accuracy; for instance, class 0 and class 1 achieve 894 and 987 correct classifications, respectively. Misclassifications are generally limited across most categories, although class 6 exhibits a higher error rate, particularly being misclassified as classes 0, 4, and 2. This suggests that these categories share similar visual features, making them more challenging to distinguish. After pruning, the RepVGG_CA_Pruned model maintains comparable overall performance, with class 0 and class 1 achieving 895 and 988 correct classifications, respectively—only marginal changes compared to the unpruned model. Notably, the confusion between class 6 and classes 0 and 4 persists but shows slight improvement, possibly because pruning simplified the network structure and enhanced its focus on certain discriminative features. However, confusion between classes 2 and 4 increases slightly, which may be due to pruning reducing the model’s ability to extract fine-grained features, thereby weakening its discrimination between visually similar apparel categories. Consequently, pruning strength should be carefully tuned to balance lightweight design and classification accuracy, especially for tasks requiring fine-grained discrimination between structurally similar apparel items, ensuring a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 9.

Confusion matrix of RepVGG_CA on the Fashion-MNIST dataset.

Figure 10.

Confusion matrix of RepVGG_CA_Pruned on the Fashion-MNIST dataset.

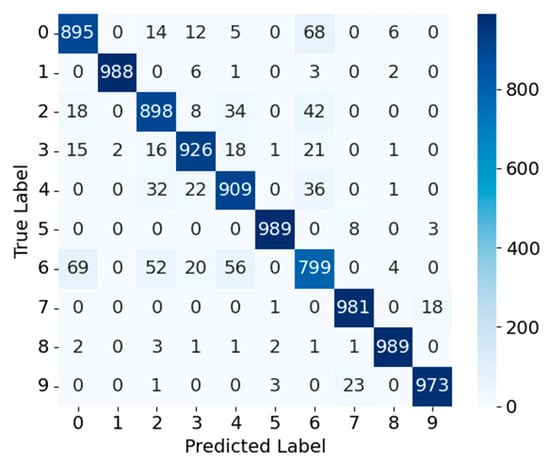

GTSRB—Figure 11 and Figure 12 present the confusion matrices for RepVGG_CA and RepVGG_CA_Pruned on the GTSRB dataset (consolidated into 10 super-classes). For RepVGG_CA, most predictions align along the diagonal, indicating strong classification performance; for example, class 0 and class 1 achieve 889 and 994 correct classifications, respectively. Misclassifications are relatively limited overall, although class 6 exhibits a noticeable error pattern, being frequently misclassified as classes 0, 2, and 4. This suggests that these categories share certain visual similarities, making them more challenging to distinguish. After pruning, the RepVGG_CA_Pruned model maintains high accuracy for most classes, with class 0 and class 1 achieving 892 and 985 correct classifications, respectively—changes that are minimal compared to the unpruned model. However, some misclassifications increase slightly, such as the confusion between classes 2 and 4, while the misclassification rate for class 6 remains relatively high. These observations imply that pruning may reduce the model’s ability to capture fine-grained features, thereby weakening its discrimination between visually similar traffic sign categories. Consequently, pruning strength should be carefully tuned to balance lightweight design and classification accuracy, particularly for traffic sign categories with subtle visual differences, ensuring a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off for deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Figure 11.

Confusion matrix of RepVGG_CA on the GTSRB dataset.

Figure 12.

Confusion matrix of RepVGG_CA_Pruned on the GTSRB dataset.

Cross-Dataset Summary—Across all three datasets, the confusion matrix analysis highlights similar trends in the impact of CA integration and channel pruning on RepVGG’s plain-structured, reparameterization-optimized design. RepVGG_CA consistently achieves strong class-level accuracy, with most predictions concentrated along the diagonal and limited confusion between visually similar categories. Channel pruning generally maintains this high-level performance, occasionally yielding accuracy gains in certain classes—likely from improved generalization. However, as with MobileNetV3, a small number of classes characterized by high intra-class diversity or subtle inter-class differences (e.g., CIFAR-10 classes 2 and 3, Fashion-MNIST class 6, GTSRB class 6) show increased confusion after pruning. This underscores the importance of tailoring pruning strategies to RepVGG’s architecture, ensuring that efficiency gains do not come at the expense of its capacity to discriminate between visually similar traffic signs, apparel items, or natural image categories.

3.4. Overall Comparison and Analysis

While sample images could be provided for qualitative illustration, we instead employ confusion matrices and quantitative metrics, which more comprehensively capture class-level classification patterns across the entire dataset. This approach avoids the subjectivity of a few selected examples and ensures that the comparison between baseline and proposed models remains systematic and rigorous.

3.4.1. Impact of CA Across Architectures

A cross-model synthesis of the ablation results on MobileNetV3 and RepVGG reveals several consistent patterns as well as architecture-specific distinctions. First, the integration of the CA mechanism alters feature representation in both architectures, but the magnitude and direction of its impact vary with network topology and dataset characteristics. In MobileNetV3, whose depthwise-separable convolutions inherently limit cross-channel interaction, CA delivers clear gains on datasets with strong spatial–channel dependencies (e.g., +1.72% on GTSRB, +0.55% on Fashion-MNIST), but leads to a notable accuracy drop on CIFAR-10 (−7.28%), likely due to over-emphasis on certain spatial cues in low-resolution, texture-rich images that disrupts the balance between local and global feature encoding. In RepVGG, the plain-structured, reparameterization-optimized design already offers strong baseline separability; CA yields incremental but stable improvements across datasets, suggesting that its primary role here is to refine rather than overhaul feature encoding.

3.4.2. Effect of Structured Channel Pruning

As noted in Section 3.1, we adopted a fixed pruning ratio by sorting the BN scaling factors and retaining approximately 70% of channels per layer. Structured channel pruning consistently reduces parameter count and FLOPs in both architectures, with MobileNetV3 exhibiting larger relative reductions due to its higher initial redundancy in depthwise and pointwise convolution channels. Accuracy degradation from pruning is generally modest, but its impact is class- and dataset-dependent: categories with high intra-class variability or subtle inter-class boundaries (e.g., CIFAR-10 classes 2/3, Fashion-MNIST class 6, GTSRB class 6) are more susceptible to performance drops. This sensitivity underscores the need for pruning strategies that are not only architecture-aware but also data-aware.

Beyond these dataset-specific effects, pruning performance is also sensitive to the choice of thresholds. In fine-grained classification tasks, overly aggressive thresholds may remove channels encoding subtle discriminative cues, leading to over-pruning and accuracy degradation. This limitation highlights the importance of adaptive or data-driven threshold selection strategies, which could provide more robust accuracy–efficiency trade-offs across diverse datasets.

3.4.3. Interaction Between CA and Pruning

The interaction between CA and pruning is non-trivial. In both models, CA can partially offset the loss of discriminative capacity introduced by pruning, particularly in classes where spatial context is critical for correct classification. However, excessive pruning can still erode fine-grained feature separability beyond what CA can recover, indicating that the two techniques must be co-tuned rather than applied independently.

3.4.4. Cross-Architecture Performance Comparison

When comparing the two architectures under equivalent optimization, MobileNetV3 variants tend to achieve higher absolute accuracy on simpler datasets (e.g., Fashion-MNIST) with greater efficiency gains from pruning, making them attractive for ultra-low-power deployments. RepVGG variants, by contrast, deliver more stable accuracy across heterogeneous datasets and maintain stronger resilience to pruning in complex visual domains, aligning them with scenarios where robustness is prioritized alongside efficiency.

3.4.5. Overall Implications

These findings confirm that the proposed CA-plus-pruning framework is adaptable across distinct lightweight architectures, but optimal performance requires tailoring the balance between representational enhancement and structural compression to both the network design and the target application domain. This comparative insight directly informs the deployment strategies discussed in Section 3.5, ensuring that architecture selection and pruning configuration are aligned with the computational constraints and accuracy requirements of specific mobile and edge-based scenarios.

3.5. Application Scenarios

The proposed lightweight image classification framework demonstrates strong potential for deployment across diverse mobile network application scenarios, where computation resources, memory capacity, and energy budgets are inherently constrained. Representative cases include real-time visual classification on smartphones, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), and edge devices integrated into 5G/6G network infrastructures. In these settings, models must sustain high predictive accuracy while meeting stringent latency requirements to support tasks such as intelligent traffic monitoring, mobile augmented reality, and on-device content filtering. By integrating CA to enhance feature representation and applying channel pruning to reduce structural redundancy, the proposed approach achieves a favorable balance between accuracy and efficiency. This enables reliable inference directly on mobile or edge hardware without reliance on continuous cloud connectivity, thereby reducing communication overhead, enhancing data privacy, and improving system responsiveness in resource-constrained mobile network deployments. Moreover, these attributes also align with the principles of federated environments, where efficient local computation and reduced reliance on centralized servers are critical for scalability and privacy preservation.

3.6. Inference Latency on Edge Hardware

In addition to the workstation environment described in Section 3.1, and to complement the accuracy, parameter, and FLOPs analyses presented in Table 2 and Table 3, inference latency was measured on an NVIDIA Jetson Nano (FP32 precision, batch size = 1) to evaluate deployment feasibility on edge hardware. As summarized in Table 4, pruning consistently reduced latency by approximately 25–35% compared with the corresponding baselines, confirming that structural compression translates into tangible runtime benefits on resource-constrained devices. In contrast, the addition of the CA module alone introduced only a marginal overhead of about 0.6–0.8 ms per image, reflecting the lightweight nature of the attention mechanism.

Table 4.

Inference latency (ms) of MobileNetV3 and RepVGG variants measured on an NVIDIA Jetson Nano (batch size = 1). MobileNetV3_CA denotes the MobileNetV3 architecture with the SE attention module in the bottleneck layers replaced by the CA module, and MobileNetV3_CA_Pruned refers to MobileNetV3_CA further enhanced through channel pruning. RepVGG_CA denotes the RepVGG architecture with the CA module incorporated, and RepVGG_CA_Pruned refers to RepVGG_CA further enhanced through channel pruning. Values are reported as the mean latency per image over five independent runs.

Across datasets, MobileNetV3 variants achieved lower absolute latency than RepVGG due to their more compact design, with the pruned MobileNetV3_CA model sustaining sub-15 ms inference, which is suitable for real-time applications such as mobile augmented reality, UAV perception, and on-device filtering. RepVGG variants, while inherently slower, benefited substantially from pruning, with RepVGG_CA_Pruned reducing latency to around 19–21 ms while maintaining stable accuracy across heterogeneous datasets. These findings indicate that MobileNetV3 is preferable when ultra-low latency is the primary requirement, whereas RepVGG offers a stronger balance between robustness and efficiency in more complex visual domains.

It should be noted that the reported latency values are specific to the Jetson Nano hardware and FP32 precision setting. While absolute numbers may vary on other devices or with mixed-precision inference, the relative trends are expected to remain consistent. Overall, the latency evaluation confirms that the proposed CA plus pruning framework not only improves model compactness but also delivers practical speedups that directly enhance the feasibility of real-time deployment on mobile and edge platforms.

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

In this work, we proposed the PACB, a lightweight framework that integrates CA with structural channel pruning to enhance representational capacity while maintaining computational efficiency. Across benchmark datasets, PACB-based models achieved accuracy improvements on several tasks and maintained competitive performance on others, while consistently reducing parameters, FLOPs, and inference latency. For example, on MobileNetV3, PACB reduced parameters from 16.2 M (Base) to 9.7 M and FLOPs from 11.3 M to 8.6 M on GTSRB, while still achieving 97.37% accuracy compared to 97.09% for the baseline. On Fashion-MNIST, PACB improved accuracy to 95.16% (vs. 94.61% baseline) with 40% fewer parameters and further reduced FLOPs to 7.5 M. For RepVGG, PACB reduced parameters from 7.68 M to 7.06 M and FLOPs from 31.3 M to 27.9 M on GTSRB, while maintaining 96.74% accuracy. Latency measurements on Jetson Nano confirmed the lightweight principle: PACB achieved 12.4–14.0 ms per image compared to 18.7–20.5 ms for the baseline in MobileNetV3 and 19.1–21.2 ms compared to 27.8–29.7 ms in RepVGG, corresponding to latency reductions of over 30%. Together with the algorithmic complexity analysis in Section 2.5, which confirmed that CA integration does not alter the asymptotic order of complexity, both theoretical and empirical evidence support the efficiency and lightweight nature of PACB.

While our study focused on uniform placement of CA modules within PACB, alternative strategies such as inserting CA only in early or late stages could in principle be explored. A more exhaustive ablation across different depths may provide additional architectural insights and remains an interesting direction for future research. Beyond structural pruning, PACB could also be combined with orthogonal compression strategies such as knowledge distillation or quantization. In addition, future work should address broader challenges in lightweight image classification, including improving training efficiency, validating scalability on larger and more diverse datasets, and exploring deployment-oriented optimizations for edge and mobile devices. These directions will further strengthen the applicability and robustness of PACB in real-world scenarios. Moreover, the lightweight and decentralized nature of PACB makes it a promising candidate for federated environments, where local computation reduces communication overhead and enhances privacy. Exploring PACB’s integration into federated learning frameworks represents an important avenue to broaden its applicability and impact in distributed systems.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study are openly available in references [21,22,23].

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadji, I.; Wildes, R.P. What do we understand about convolutional networks? arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.08834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50× fewer parameters and <0.5MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, H.T.; Sun, J. ShuffleNet V2: Practical guidelines for efficient CNN architecture design. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 116–131. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. MobileNets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.C. MobileNetV2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.C.; Tan, M.; Chu, G.; Vasudevan, V.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Ma, N.; Han, J.; Ding, G.; Sun, J. RepVGG: Making VGG-style ConvNets great again. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13728–13737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13708–13717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, G. Lightweight Image Classification Network Based on Feature Extraction Network SimpleResUNet and Attention. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=tItq3cwzYc (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Li, H.; Kadav, A.; Durdanovic, I.; Samet, H.; Graf, H.P. Pruning filters for efficient ConvNets. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1608.08710. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.; Pool, J.; Tran, J.; Dally, W.J. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural networks. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), Montreal, QC, Canada, 7–12 December 2015; pp. 1135–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Mu, H.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Z.; Yang, X.; Cheng, T.; Sun, J. MetaPruning: Meta learning for automatic neural network channel pruning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3296–3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J. Channel pruning for accelerating very deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the Knowledge in a Neural Network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rastegari, M.; Ordonez, V.; Redi, E.; Farhadi, A. Xnor-Net: Imagenet Classification Using Binary Convolutional Neural Networks. In Computer Vision—ECCV 2016, Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 525–541. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, X.; Mu, H.; Heng, W.; Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Sun, J. Single path one-shot neural architecture search with uniform sampling. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Yao, W.; Peng, S.; Yao, S. Automatic Filter Pruning Algorithm for Image Classification. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.; Yao, L.; Liu, F.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Chen, N.; Xu, S.; Zhou, J. RemoteTrimmer: Adaptive Structural Pruning for Remote Sensing Image Classification. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A. CIFAR-10 Dataset. University of Toronto. Available online: https://www.cs.toronto.edu/~kriz/cifar.html (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Xiao, H.; Rasul, K.; Vollgraf, R.; Fashion-MNIST Dataset. Zalando Research. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/zalando-research/fashionmnist (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Stallkamp, J.; Schlipsing, M.; Salmen, J.; Igel, C. GTSRB—German Traffic Sign Recognition Benchmark. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/meowmeowmeowmeowmeow/gtsrb-german-traffic-sign (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Chen, X.; Hu, Q.; Li, K.; Zhong, C.; Wang, G. Accumulated Trivial Attention Matters in Vision Transformers on Small Datasets. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 2–7 January 2023; pp. 1003–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y. MSCViT: A Small-Size ViT Architecture with Multi-Scale Self-Attention Mechanism for Tiny Datasets. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.06040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, S. Traffic sign recognition based on deep learning and simplified GTSRB dataset. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1881, 042052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).