Abstract

This paper introduces TRIDENT-DE, a novel ensemble-based variant of Differential Evolution (DE) designed to tackle complex continuous global optimization problems. The algorithm leverages three complementary trial vector generation strategies best/1/bin, current-to-best/1/bin, and pbest/1/bin executed within a self-adaptive framework that employs jDE parameter control. To prevent stagnation and premature convergence, TRIDENT-DE incorporates adaptive micro-restart mechanisms, which periodically reinitialize a fraction of the population around the elite solution using Gaussian perturbations, thereby sustaining exploration even in rugged landscapes. Additionally, the algorithm integrates a greedy line-refinement operator that accelerates convergence by projecting candidate solutions along promising base-to-trial directions. These mechanisms are coordinated within a mini-batch update scheme, enabling aggressive iteration cycles while preserving diversity in the population. Experimental results across a diverse set of benchmark problems, including molecular potential energy surfaces and engineering design tasks, show that TRIDENT-DE consistently outperforms or matches state-of-the-art optimizers in terms of both best-found and mean performance. The findings highlight the potential of multi-operator, restart-aware DE frameworks as a powerful approach to advancing the state of the art in global optimization.

1. Introduction

Global optimization remains a central challenge in computational science, offering indispensable tools for addressing problems of high complexity in diverse domains ranging from engineering and physics to economics, biology, and artificial intelligence. Unlike local search methods that tend to converge toward nearby minima and thus risk entrapment in suboptimal solutions, global optimization seeks to explore the search space more comprehensively in order to identify the true global optimum. The inherent difficulty of such tasks arises from the presence of multimodality, discontinuities, nonconvex structures, and high dimensionality, all of which demand algorithmic strategies that balance exploration with exploitation in a highly adaptive manner.

Global optimization is most clearly grounded in its mathematical formulation. Let be a continuous real-valued function defined on a feasible region . The goal is to determine a global minimizer such that for all . The feasible region is typically modeled as a Cartesian product of closed and bounded intervals, , ensuring that S is compact (and convex under interval bounds). Under these conditions, optimization becomes the systematic pursuit of the minimizer within a well-defined, yet potentially rugged and high-dimensional, landscape.

Over the past decades, a wide variety of optimization algorithms have been introduced, evolving from traditional deterministic approaches to powerful modern metaheuristics. Classical derivative-based methods, such as steepest descent [1] and Newton’s method [2], are efficient for smooth and convex problems but struggle in the absence of gradient information or in the presence of multiple minima. Stochastic search methods like Monte Carlo sampling [3] and simulated annealing [4] introduced robustness to noise and multimodality but at the expense of slower convergence.

A particularly influential family of methods has been population-based metaheuristics. Genetic Algorithms (GA) [5], Differential Evolution (DE) [6,7,8,9], and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) [10,11,12] remain standard references in this field, each exploiting collective dynamics of populations to efficiently explore the solution space. Within this lineage, numerous refinements have been proposed to enhance adaptivity and performance. Self-adaptive Differential Evolution (SaDE) [13] and jDE [14] introduced mechanisms whereby control parameters co-evolve alongside candidate solutions, leading to more resilient search dynamics. Comprehensive Learning Particle Swarm Optimization (CLPSO) [15] extended the PSO paradigm by enhancing the information-sharing process across the swarm, thus improving the ability to escape local minima. The Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) [16], often regarded as one of the most sophisticated evolutionary optimizers, dynamically adapts covariance structures to guide search more effectively in anisotropic landscapes.

DE has evolved through several influential variants that improved either adaptation, sampling, or selection. JADE introduced the DE/current-to-pbest mutation with an external archive and on-the-fly parameter adaptation, substantially strengthening convergence and diversity control [17]. Building on JADE’s ideas, SHADE proposed success-history-based adaptation for F and CR, while L-SHADE further coupled this with linear population-size reduction to enhance late-stage exploitation [18,19]. In parallel, ensemble-style approaches such as CoDE and EPSDE combined multiple trial generators and parameter pools within a single framework, often yielding robust performance across heterogeneous landscapes [20,21]. More recently, jSO distilled the SHADE/L-SHADE family into an efficient adaptive scheme that performed strongly on CEC benchmarks [22], while lines such as LSHADE-RSP and multi-operator LSHADE variants integrated restart and local-search mechanisms [23,24]. Against this background, TRIDENT-DE is positioned as a complementary design: it employs a two-stage acceptance (a greedy refinement step followed by evaluation of the raw trial vector) and integrates this acceptance logic with our DE pipeline. This differs from success-history adaptation and ensemble selection in that it explicitly structures acceptance pressure at the variation level, which we show can improve stability of best and mean performance on real-world problems considered in this work. These developments provide the immediate backdrop against which more specialized and hybrid designs have emerged.

Recent years have also seen the development of highly specialized and hybrid approaches that push the limits of global optimization. The EA4Eig algorithm [25] exploits eigenspectrum information to adjust search directions more intelligently. The UDE3 (also known as UDE-III) method [26] introduces novel recombination schemes that maintain diversity while emphasizing convergence. Such developments underscore a continuing trend toward hybridization and adaptivity, in which classical frameworks are enriched by dynamic control, learning mechanisms, or hybrid ensembles of operators.

Derivative-free approaches such as the Nelder-Mead simplex [27] retain relevance in low-dimensional and gradient-free scenarios, while biologically and physically inspired heuristics such as ant colony optimization [28] and artificial bee colony [29] continue to provide innovative perspectives by mimicking natural processes [30]. These diverse algorithmic families collectively form the backbone of contemporary global optimization research, where robustness, scalability, and adaptivity remain the primary objectives.

The present article introduces TRIDENT-DE, a novel algorithmic framework that distinguishes itself from the aforementioned methodologies through its explicit reliance on a triple-operator ensemble structure combined with adaptive restart and greedy refinement strategies. Unlike standard Differential Evolution variants that typically rely on a single trial vector generation scheme, TRIDENT-DE simultaneously employs best/1/bin, current-to-best/1/bin, and pbest/1/bin within a self-adaptive mechanism, ensuring a dynamic balance between exploration and exploitation. This triadic structure, metaphorically represented as a “trident,” allows the algorithm to probe the search space from complementary perspectives, thereby reducing the likelihood of premature convergence. Furthermore, TRIDENT-DE incorporates a micro-restart mechanism that reinitializes a fraction of the population around the elite solution with Gaussian perturbations, preserving diversity without discarding accumulated information. An additional greedy line-refinement operator accelerates convergence by projecting solutions along base-to-trial directions, enabling more aggressive exploitation of promising regions. In contrast to hybrid algorithms that often combine unrelated strategies in ad hoc ways, TRIDENT-DE presents a cohesive framework where each component synergistically reinforces the others, yielding a method that is not only adaptive and robust but also computationally efficient. This conceptual and practical novelty positions TRIDENT-DE as a competitive advancement in the landscape of global optimization, capable of addressing high-dimensional, multimodal problems with a level of aggressiveness and resilience that surpasses existing methods.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details TRIDENT-DE, including design rationale and implementation aspects. Section 3 introduces the experimental protocol and results: Section 3.1 summarizes settings and computational environment, Section 3.2 enumerates the benchmark suites with emphasis on real-world instances, Section 3.3 analyzes parameter sensitivity, Section 3.4 examines time complexity and scaling behavior, Section 3.6 investigates neural network training with TRIDENT-DE on public classification datasets and Section 3.5 reports the comparative assessment against state-of-the-art solvers. Finally, Section 4 concludes with key findings and directions for future work.

2. The TRIDENT-DE Method

We now present the pseudocode of TRIDENT-DE to make the full control loop explicit. Before diving into it, recall that updates are executed in mini-batches: each agent builds multiple trials using three complementary Differential Evolution operators and retains the best one. A low-cost greedy line refinement is then applied along the base-to-trial direction, while parameters are perturbed via light self-adaptation. Iteration-level progress is assessed explicitly, when stagnation is detected, adaptive micro-restarts refresh diversity without disrupting exploitation around the elite. Feasibility is enforced by box projection, and termination follows an evaluation budget or a maximum-iteration cap. With this context, the pseudocode in Algorithm 1 below summarizes the stages and decision points implemented in TRIDENT-DE.

| Algorithm 1 TRIDENT-DE (Triple-Operator, Restart-Aware DE) |

Input: objective f, dimension n, population N, max iters , max evals , bounds Params: base F, crossover C, operator probs (best/1, cur2best/1, pbest/1), stagnation trigger , restart fraction , elite size , jitter amplitude , elite-kick prob , line-refine factor 01 For i = 1…N do 02 For j = 1…n do 03 sample from Uniform () 04 End for 05 06 End for 07 , ← , , , , 08 While () and () do 09 , update // refresh incumbent 10 For i = 1…N do 11 If i = then continue 12 , // cache current 13 Draw op ∈ {best/1, cur2best/1, pbest/1, none} with probs (r, q, p, ) 14 , 15 , , 16 If op = best/1 then 17 Else if op = cur2best/1 then 18 Else if op = pbest/1 then pick , 19 Else 20 End if 21 Pick uniformly from {1…n} 22 For j = 1…n do 23 If Uniform(0,1) < orj = then else 24 25 End for 26 , , 27 // ============= Two-Stage Acceptance (explicit) ============= 28 // =====Stage 1: Greedy refinement along base-to-trial direction==== 29 , 30 If then 31 , 32 If then , , , update elite ring A keeping 33 Else 34 // =====Stage 2: Evaluate and consider the raw trial vector z===== 35 , 36 If then 37 , 38 If then , , 39 Else 40 , // explicit revert if neither stage improves 41 End if 42 End if 43 End for 44 If no improved then else 45 If then 46 , pick worst m indices set W 47 For each i in W do 48 If Uniform (0, 1) < then 49 sample from 50 Else 51 sample each from Uniform() 52 End if 53 Project to box , 54 , 55 End for 56 57 End if 58 End while 59 Return |

- Notes for pseudocode.

- Objective and domain. , . A candidate is .

- Population and elite. Size N, is the i-th individual, . Best index , elite , . Elite archive A holds up to best solutions (ties by f).

- Operators. One of best/1, current-to-best/1, pbest/1, or none, drawn with probabilities . With :

- Controls. Per-individual jitter and with . Scalar ; vector applies component-wise.

- Crossover and projection. Binomial crossover with rate and one forced index from v ensures . Project: .

- Greedy refinement (one step). With , , ; greedy selection against the snapshot .

- Stagnation and micro-restarts. If no improves, stagnation counter ; if , restart worst individuals bythen project .

- Termination. Primary: ; secondary: .

TRIDENT-DE is a population-based, derivative-free optimizer designed for box-constrained minimization of a continuous objective over . At iteration t, the algorithm maintains a population with fitness values . The incumbent elite is

An elite archive A of capacity stores the best solutions seen so far (ties resolved by f) to support pbest sampling, feasibility is enforced throughout by componentwise projection , where for each coordinate j we set .

- Initialization.

Each coordinate is drawn independently as ; then is evaluated, the elite is set, and the archive is seeded as . This uniform seeding spreads initial mass across S without imposing structural priors on f.

- Per-iteration control flow.

At the start of iteration t, the elite is refreshed so that all subsequent operators are anchored to the most recent best. For each individual i, a rollback snapshot is taken to guarantee non-worsening replacement. A trial-vector generator is selected by a categorical draw with probabilities . This triad yields complementary pressures: best/1 concentrates exploitation around ; current-to-best/1 steers toward while retaining a differential term, pbest/1 exploits to distribute attraction over multiple high-quality anchors, the none branch stabilizes dynamics when parameter jitter is aggressive.

- Light self-adaptation.

Control parameters are perturbed at the individual level using one Gaussian deviate per parameter:

with independent and controlling jitter amplitude. This preserves evaluation efficiency while adapting to local roughness.

- Donor formation, crossover and projection.

With mutually distinct indices drawn uniformly from , the donor v is

and if . Binomial crossover with rate forms z from , forcing one dimension from v to ensure ; feasibility is restored by .

- One-step greedy refinement and acceptance.

Let . A low-cost, one-evaluation line refinement proposes

and evaluates . If , we accept ; otherwise we evaluate the raw trial once, , accepting z if and rolling back to otherwise. Whenever a replacement improves the global best, we set , update , and update the archive A (insert if , else replace the worst).

- Stagnation and adaptive micro-restarts.

A stagnation counter s increments when no improves within an iteration; otherwise it resets. If , we restart the worst individuals. For each restarted index i, with probability we sample an elite-centred Gaussian kick

and with probability we reinitialize uniformly ; in both cases we project with and refresh .

- Budget and ordering.

Termination is governed primarily by the evaluation budget and secondarily by an iteration cap . The ordering elite refresh, operator selection, parameter jitter, donor formation, crossover, projection, greedy refinement, fallback raw-trial, acceptance/archive update, stagnation accounting, and (if needed) micro-restart ensures that refinement reuses a precomputed direction, projection preserves feasibility at every stage, and diversity is injected only under verified stagnation.

As shown in Figure 1, after initialization and elite refresh, each agent undergoes operator selection, parameter jitter, trial construction, and greedy line refinement, followed if necessary by a single raw-trial evaluation. Iteration-level progress is assessed at node U, to avoid ambiguity, the “Yes” and “No” branches lead to separate actions V (reset stagnation counter) and Y (increase stagnation counter) which both feed into W (restart trigger). When the trigger fires, micro-restarts (X) rejuvenate a worst fraction near the elite (or uniformly), after which the loop returns to the main termination check. This organization clarifies control flow, emphasizes the low-cost refinement step, and shows precisely how stagnation governs diversity injection.

Figure 1.

TRIDENT-DE flowchart: triple-operator DE with greedy refinement and adaptive micro-restarts.

3. Experimental Setup and Benchmark Results

3.1. Setup

Table 1 summarizes the core settings of TRIDENT-DE, grouping the population size, the box bounds, and the default DE controls (F, C) together with the jDE-style self-adaptation (resampling probabilities and sampling ranges). It also lists the hyperparameters governing the triple trial-vector ensemble, the greedy line-refinement, and the adaptive micro-restart policy (restart fraction , Gaussian kick scale , stagnation trigger ). Note that operator scheduling follows a round-robin (three operators) scheme in the manuscript, while the implementation uses a round-robin (three operators) to balance exploration and exploitation across iterations. The defaults = and = 500 standardize the computational budget across problems and act as termination criteria, with priority given to the evaluation budget (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Default TRIDENT-DE settings: exploration-exploitation balance and restart mechanisms.

Table 2 reports the configurations of all competitor methods to ensure reproducibility and fairness with respect to population size and iteration budget. For each algorithm, we list its internal controls (e.g., the comprehensive-learning probability for CLPSO, population sizing and coefficients for CMA-ES, JADE-style parameters for EA4Eig, success-history memories and p-best ranges for mLSHADE_RL and UDE3, and adaptation schemes for SaDE) as used in our experiments. Harmonizing the population at N = 100 and the iteration cap at = 500 guarantees comparability, while per-method settings follow the literature and publicly available implementations.

Table 2.

Parameters of other methods.

All experiments were conducted on a high-performance node featuring a cpu with 32 threads running Debian Linux. The evaluation protocol was designed for statistical rigor and reproducibility: each benchmark function was executed 30 times independently, using distinct random seeds to capture the stochastic variability of the algorithms.

The proposed method and all baselines were implemented in optimized ANSI C++ and integrated into the open-source OPTIMUS framework [31]. The source code is hosted at https://github.com/itsoulos/GLOBALOPTIMUS (accessed 25 September 2025), ensuring transparency and reproducibility. Parameter settings exactly follow Table 1 and Table 2. Build environment: Debian 12.12 with GCC 13.4.

The primary performance indicator is the average number of objective-function evaluations over 30 runs for each test function. In all ranking tables comparing solvers, best values are highlighted in green (1st place) and second-best values in blue (2nd place).

3.2. Benchmark Functions

Table 3 compiles the real-world optimization problems used in our evaluation. For each case, we report a brief description, the dimensionality and variable types (continuous/mixed-integer), the nature and count of constraints (inequalities/equalities), salient landscape properties (nonconvexity, multi-modality), as well as the evaluation budget and comparison criteria. The set spans, indicatively, mechanical design, energy scheduling, process optimization, and parameter estimation with black-box simulators, ensuring that conclusions extend beyond synthetic test functions. Where applicable, we also note any normalizations or constraint reformulations adopted for fair comparison.

Table 3.

The real world benchmark functions used in the conducted experiments.

3.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis of TRIDENT-DE

Following Lee et al.’s [52] parameter-sensitivity methodology, we construct a structured analysis to quantify responsiveness to parameter changes and the preservation of reliability across diverse operating regimes.

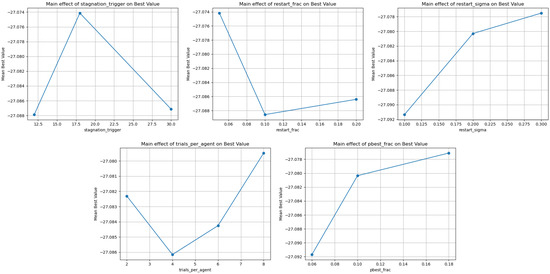

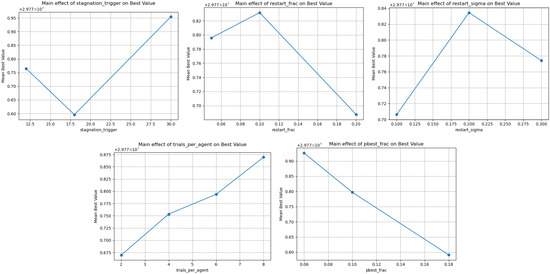

The parameter sensitivity study probes the stability of TRIDENT-DE under controlled variations of key hyperparameters and quantifies whether reliability is preserved across heterogeneous operating conditions. We focus on the stagnation counter before restart , the restart fraction , the elite-centred Gaussian kick scale at restart, the number of trials per agent t, and the top-p fraction that governs the pbest/1 sampling. Each factor is swept over representative values around the defaults in Table 1 while the remaining factors are kept fixed, and we record the impact on mean performance, extrema, and the main-effect range for three complementary test classes: a molecular Lennard-Jones cluster at N = 10, the Tersoff potential for silicon (model B), and the Static Economic Load Dispatch (ELD-1) problem. These three benchmarks span rugged, multimodal physical landscapes and heavily constrained industrial testbeds, making the observed trends transferable rather than instance-specific. For Lennard-Jones, perturbations around = 12/18/30, = 0.05/0.1/0.2, = 0.1/0.2/0.3, t = 2/4/6/8, and = 0.06/0.10/0.18 induce only minor shifts in mean objective value and very small main-effect ranges across all factors, indicating inherent robustness of the method in this multimodal setting. The tight concentration of means around ~−27.08 together with the lack of systematic movement in extremes suggests that the triple-operator ensemble, the mild jDE-style control on F and C, and the one-step greedy line refinement act as dampers against parameter oversensitivity, especially because the refinement reuses a precomputed direction at negligible variance cost. These observations are evident in Table 4 and Figure 2.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the method parameters for the “Lennard-Jones Potential, Dim:10” problem.

Figure 2.

Graphical representation of , , t and for the “Lennard-Jones Potential, Dim:10” problem.

In the Tersoff-Si (model B) potential, the overall robustness pattern persists, with the number of trials per agent t showing the most noticeable albeit still small effect on mean performance and main-effect range. Increasing t slightly improves exploitation of promising directions, occasionally trading off diversity, yet exploration remains safeguarded by adaptive micro-restarts, so the dynamics do not collapse. The gentle drift in mean with t does not overturn the defaults of Table 1, whereas and exert only marginal influence within the probed ranges, underscoring that restarts serve as a safety valve rather than a dominant driver. The quantitative evidence is given in Table 5 and Figure 3.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis of the method parameters for the “Tersoff Potential for model Si (C)” problem.

Figure 3.

Graphical representation of , , t and for the “Tersoff Potential for model Si (C)” problem.

The picture changes more distinctly for ELD-1. Here, the lack of time coupling removes inter-temporal interactions, yet feasibility remains tight due to the power-balance equality and unit output bounds. Depending on the presence of valve-point effects, the landscape can be markedly nonconvex, with ripple-like undulations around local extrema. In this setting, the stagnation threshold still acts as a reliable trigger for rejuvenation when the population gets trapped in shallow basins, but its relative influence is smaller than in dynamic DED-type problems because there are no time-linked plateaus reinforcing stagnation. By contrast, the top-p fraction becomes the primary control knob: it governs how strongly the search is pulled toward p-best elites, mediating the trade-off between aggressive exploitation near top units and the preservation of diversity across alternative feasible corridors. Increasing t (trials per agent) further improves the use of local directions without collapsing exploration, as adaptive micro-restarts with calibrated and inject gentle diversity whenever stagnation is detected. The results in Table 6 and the corresponding Figure 4 indicate that defaults around ≈ 18 and ≈ 0.10 are safe operating points for ELD-1, small local retunings of these two parameters can yield more stable quality jumps when valve-point ripples make the landscape more “toothed,” without requiring adjustments to and beyond the probed ranges.

Table 6.

Sensitivity analysis of the method parameters for the “Static Economic Load Dispatch 1” problem.

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of , , t and for the “Static Economic Load Dispatch 1” problem.

Taken together, the sensitivity profile shows that the defaults in Table 1 are well-balanced across diverse problems: and regulate a gentle injection of diversity without disrupting exploitation, shapes the attraction lattice of pbest/1 across multiple elites, and t enhances the utility of the already computed direction at modest additional cost. The small main-effect ranges observed in Lennard-Jones and Tersoff confirm that the triple-operator design, combined with light jDE-style jitter on F and C, yields a self-stabilising regime in which parameter effects are largely second-order. Conversely, in heavily constrained energy scheduling, and become active control knobs, consistent with a landscape featuring broad plateaus and tight feasibility margins. The practical implication is twofold: first, the proposed defaults deliver portable reliability with minimal pre-tuning, second, when constraints dominate, a narrow local retuning of and around their nominal values preserves the best search rate without sacrificing stability. These conclusions align with the architecture of TRIDENT-DE, where interactions among three trial generators, one-step greedy refinement, and adaptive micro-restarts distribute the burden of adaptation and, as a result, insulate the system from sharp nonlinearities in any single hyperparameter.

3.4. Analysis of Complexity of TRIDENT-DE

Below we provide a bullet-style specification of two real-world optimization problems adopted as representative testbeds for the time-complexity and scaling analysis of the proposed method, we summarise the key decision variables, admissible bounds/domains, and objective functions, and explicitly note relevant modeling assumptions and feasibility penalty terms, so that the ensuing bullets serve as a quick “map” of practical constraints and goals prior to the runtime evaluation.

- GasCycle Thermal CycleVars: .Bounds:Penalty: infeasible .

- Tandem Space Trajectory (MGA-1DSM, EVEEJ + 2 × Saturn)Vars():.Objective:Notes: decreases (log-like) in (≥6 km/s floor), leg/branch costs decrease with TOF.

The time-complexity Figure 5 reveals an almost linear growth of wall-clock time with respect to problem size (40–400) for both GasCycle Thermal Cycle and Tandem Space Trajectory. The monotonic trend and near-constant increments per size step indicate that the proposed architecture scales effectively with in the investigated size parameter, with no signs of exponential or strongly super-linear behavior. Across the two cases, Tandem Space Trajectory consistently exhibits slightly higher times, which is naturally explained by a larger per-evaluation cost of the underlying simulator/objective in that domain. In other words, the dominant contributor to total runtime is the evaluation cost, while the search mechanism itself preserves an approximately constant slope with respect to size. The absence of kinks or abrupt escalations at larger sizes further suggests that components such as the triple trial-vector ensemble, the one-step greedy line refinement, and the adaptive micro-restarts do not introduce hidden overhead that would manifest as degraded asymptotic scaling. Practically, the method remains predictable and efficient as the problem grows, with performance primarily governed by the problem-dependent evaluation burden. The mild, roughly constant offset between the two benchmarks over the 40–400 range reinforces the view that this is a domain-dependent additive cost rather than a change in the algorithm’s scaling rate. Overall, the evidence supports a favorable scaling profile: linear complexity in the examined size parameter, stability under heavier loads, and a clean separation between a stable algorithmic overhead and the variable evaluation cost imposed by each application.

Figure 5.

Time scaling under a fixed iteration budget.

3.5. Comparative Performance Analysis of TRIDENT-DE

This section introduces the experimental component that assesses the proposed method across alternative configurations and problem sets, emphasizing behavioral consistency and reproducibility. Table 7 compiles the corresponding comparative figures and summary evaluation metrics.

Table 7.

Comparison Based on Best and Mean after 1.5 × 105 FEs.

Table 7 reports best and mean performance under a common budget of evaluations across synthetic and real-world problems. On the Lennard-Jones suite (N = 10, 13, 38), TRIDENT-DE reaches energy minima on par with the strongest baselines while keeping the best-mean gap tight evidence that top results are reliably repeatable rather than isolated lucky runs. This contrasts with the pronounced variability seen in some competitors (e.g., large outliers for jDE on LJ-38), underscoring how the triple trial-vector ensemble, one-step greedy refinement, and micro-restarts absorb multi-modality without sacrificing diversity.

For the Tersoff-Si (B/C) potentials, the pattern remains favorable: TRIDENT-DE’s best values are competitive or superior, and, crucially, the mean is often lower than that of many baselines, implying a higher probability of obtaining high-quality solutions in a typical run. The detailed rankings corroborate this view: by mean performance, TRIDENT-DE stays among the top ranks on physical potentials and several real-world tasks (e.g., TNEP, wireless coverage), highlighting robustness under constraints and irregular landscapes (see Table 8 and Table 9).

Table 8.

Detailed Ranking of Algorithms Based on Best after 1.5 × 105 FEs. The values highlighted in green indicate the best performance, while those in blue denote the second-best performance.

Table 9.

Detailed Ranking of Algorithms Based on Mean after 1.5 × 105 FEs. The values highlighted in green indicate the best performance, while those in blue denote the second-best performance.

Across real-world instances, behavior is category-dependent. In Transmission Network Expansion Planning and antenna placement/coverage, TRIDENT-DE shows excellent or strongly competitive outcomes with narrow best-mean spreads, indicating trustworthy single-run performance. In a few specialized settings, such as circular antenna design or the Cassini 2 trajectory problem, isolated top scores emerge from specific baselines (e.g., EA4Eig, CMA-ES), consistent with their aptitude for lower effective dimensional subspaces or smoother subregions. Still, when aggregating global evidence via mean-based rankings and win/placement totals, TRIDENT-DE achieves the best overall average rank among all contenders (Table 10), suggesting that its advantage is portable rather than instance-specific.

Table 10.

Comparison of Algorithms and Final Ranking. The values highlighted in green indicate the best performance, while those in blue denote the second-best performance.

In the energy family, nuances appear. On DED variants, methods with strong adaptive dispersion (e.g., CMA-ES) often secure high placements, reflecting their ability to navigate plateau-like score profiles. Conversely, in ELD-1 without time coupling classical DE flavors may occasionally top the mean ranking, yet TRIDENT-DE remains consistently competitive and close to the optimal operating window, as evidenced by its mean figures in Table 7 and the per-problem ranks in Table 9. Practically, even when a “specialist” baseline dominates a narrow niche, TRIDENT-DE does not collapse in reliability, it maintains a small best-mean gap and stays near the top on average.

Overall, Table 7 reveals two complementary strengths: high best-case performance across a wide variety of instances and consistently strong mean performance that makes those peaks reproducible. When combined with the consolidated standings and Overall Average Rank in Table 9 and Table 10, the picture is clear: TRIDENT-DE delivers strong, stable, and widely transferable performance compared to the alternatives, with only a handful of exceptions where specific competitors exploit landscape idiosyncrasies to claim local wins.

3.6. Neural Network Training with TRIDENT-DE

We conducted an additional set of experiments where TRIDENT-DE was employed as the optimizer for training feedforward artificial neural networks [53,54] Given a training set , with input vectors and targets (for classification, either scalar class indices or one-hot vectors), the objective minimized by TRIDENT-DE was the mean-squared training error:

where denotes the neural network’s mapping parameterized by the weight (and bias) vector . In this setup, each candidate solution encoded all trainable parameters of the network, TRIDENT-DE evolved these parameters directly in continuous space. Unless otherwise noted, inputs were standardized to zero mean and unit variance, categorical labels were one-hot encoded when needed, and training used full batches on each fitness evaluation of (1). To reduce overfitting, we monitored validation error for early stopping, in some runs we also added regularization by augmenting (1) with (small ), without altering the optimizer.

To gauge performance across heterogeneous conditions, we compiled a broad suite of publicly available classification datasets spanning low to moderate dimensionality and varying class balance. Datasets were sourced from:

- The UCI Machine Learning Repository, https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ (accessed on 18 September 2025) [55].

- The KEEL collection, https://sci2s.ugr.es/keel/datasets.php (accessed on 18 September 2025) [56].

- The StatLib archive, https://lib.stat.cmu.edu/datasets/index (accessed on 18 September 2025).

The experiments were conducted using the following datasets:

- Appendicitis: medical classification of acute appendicitis cases [57].

- Alcohol: records related to alcohol consumption patterns [58].

- Australian: heterogeneous banking/credit transaction data [59].

- Balance: psychophysical balance-scale experiment outcomes [60].

- Cleveland: coronary heart disease dataset analyzed in multiple studies [61,62].

- Circular: synthetic two-dimensional nonlinearly separable data.

- Dermatology: clinical attributes for dermatological diagnosis [63].

- Ecoli: protein localization/functional attributes in E. coli [64].

- Fert: relations between sperm concentration and demographic variables.

- Glass: chemical composition measurements for glass type identification.

- Haberman: breast-cancer survival after surgery.

- Hayes-Roth: classic concept-formation benchmark [65].

- Heart: clinical indicators for heart-disease detection [66].

- HeartAttack: medical features targeting early detection of cardiac events.

- Housevotes: U.S. Congressional voting records by bill/party [67].

- Ionosphere: radar returns measuring ionospheric conditions [68,69].

- Liverdisorder: liver function tests widely studied in the literature [70,71].

- Lymphography:imaging/diagnostic attributes of lymphatic diseases [72].

- Mammographic: features for breast-cancer mass prediction [73].

- Parkinsons: voice/acoustic markers of Parkinson’s disease [74,75].

- Pima: diabetes onset in Pima Indian women [76].

- Phoneme: short-duration speech sounds (phoneme recognition).

- Popfailures: climate/meteorology-related experimental observations [77].

- Regions2: medical attributes related to liver diagnostics [78].

- Saheart: cardiovascular risk factors and outcomes [79].

- Segment: multivariate image segmentation benchmark [80].

- Sonar: acoustic echoes distinguishing metal vs. rock objects [81].

- Statheart: additional heart-disease classification dataset.

- Spiral: synthetic two-class intertwined spiral (nonlinear boundary).

- Student: school performance and demographic indicators [82].

- Transfusion: blood-donation behavior and response modeling [83].

- WDBC: Wisconsin Diagnostic Breast Cancer (malignant vs. benign) [84,85].

- Wine: oenological measurements for wine quality/type discrimination [86,87].

- EEG: brain-signal recordings; cases used—Z_F_S, ZO_NF_S, ZONF_S, Z_O_N_F_S [88,89].

- Zoo: animal taxonomy classification via morphological traits [90].

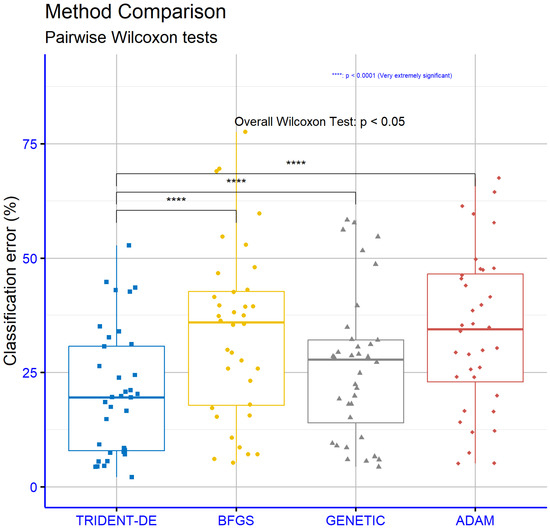

The Table 11 demonstrates a clear advantage of TRIO over BFGS, Genetic, and ADAM in terms of classification error. TRIO attains an average error of 20.46%, compared to 33.80% for BFGS, 26.46% for Genetic, and 34.08% for ADAM amounting to relative reductions of approximately 39.5% vs. BFGS, 22.7% vs. Genetic, and 40.0% vs. ADAM. At the dataset level, TRIO achieves the lowest error on 34 out of 36 benchmarks, with only two exceptions AUSTRALIAN and LIVERDISORDER where Genetic holds a narrow lead (32.10% vs. 33.97% and 31.11% vs. 31.15%, respectively). TRIO’s dominance extends to both “easier” datasets (e.g., ZONF_S 2.10%, STUDENT 4.38%, POPFAILURES 4.43%, CIRCULAR 4.58%, ZOO 5.60%, WINE 7.47%, WDBC 7.63%) and “harder” ones where all methods incur higher errors (e.g., CLEVELAND, ECOLI, SEGMENT, SPIRAL), consistently delivering the best performance. Overall, the results indicate that TRIO combines low average error with strong robustness (median ≈ 19.58%) across heterogeneous benchmarks, whereas BFGS and ADAM lag systematically, and Genetic is competitive only in a small number of cases.

Table 11.

Multi -Dataset Evaluation of Machine-Learning Methods for Classification.

Using R version 4.5 scripts applied to the empirical results tables, we assessed statistical significance via the p-value criterion. Figure 6 reports the significance encoding (ns for p > 0.05, * for p < 0.05, ** for p < 0.01, *** for p < 0.001, **** for p < 0.0001) across the classification datasets and the models under comparison. All three pairwise contrasts yielded ****—that is, p < 0.0001 for TRIDENT-DE vs. BFGS, TRIDENT-DE vs. GENETIC, and TRIDENT-DE vs. ADAM. These results provide very strong statistical evidence that TRIDENT-DE outperforms the baselines on the examined datasets, making it highly unlikely that the observed gains are attributable to random variation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparative Statistical Evaluation on Classification Benchmarks.

4. Conclusions

The empirical evidence demonstrates that TRIDENT-DE delivers strong and transferable performance across heterogeneous settings from rugged physical landscapes (Lennard-Jones, Tersoff) to tightly constrained industrial/energy tasks (ELD/DED) and complex real-world applications (TNEP, wireless coverage, orbital design). Aggregated results in Table 7 show competitive best values accompanied by consistently tight best-mean gaps, indicating reproducible quality rather than isolated lucky hits. This picture is reinforced by the detailed standings in Table 9, where TRIDENT-DE maintains top-tier positions on physical potentials and several real-world tasks, while the final consolidated ranking in Table 10 yields the best Overall Average Rank among all contenders evidence of broad portability rather than niche specialization.

Mechanistically, the parameter-sensitivity study in Section 3.3 indicates an intrinsically self-stabilising regime: the principal hyperparameters exert second-order effects across most domains, with targeted leverage for the stagnation threshold and the top-p fraction (p-best) on heavily constrained landscapes. In Lennard-Jones and Tersoff, main-effect ranges remain small near the defaults, consistent with the triple operator ensemble, light jDE-style control on F, C and one-step greedy line refinement acting as dampers against parameter oversensitivity. In energy scheduling (ELD/DED), strict feasibility and plateau-like regions elevate the roles of and as control knobs for timely rejuvenation and exploitation-exploration balance, respectively. This behaviour is quantified in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 and the accompanying figures.

Time-scaling evidence (Figure 5) adds a key dimension: wall-clock time grows approximately linearly with size in two representative domains (“GasCycle Thermal Cycle” and “Tandem Space Trajectory”), with no super-linear pathologies. The slightly higher curve of the latter reflects a domain-dependent additive evaluation cost rather than a shift in the algorithm’s scaling rate, yielding predictability under load and a clean separation between stable algorithmic overhead and problem-dependent evaluation burden.

Beyond physical and industrial benchmarks, the experiments in Section 3.6 show that TRIDENT-DE is also an effective trainer for artificial neural networks, directly optimizing weights and biases by minimizing the mean-squared error. Evaluations on a broad suite of public classification datasets (UCI, KEEL, StatLib) consistently yielded lower error rates than BFGS, Genetic, and ADAM, with significance tests confirming p < 0.0001 for all pairwise contrasts against TRIDENT-DE. These results extend the portability of our conclusions from pure black-box optimization to machine-learning settings, indicating that the triple trial-vector ensemble, the one-step greedy refinement, and adaptive micro-restarts translate into robust gains for parameter tuning in learned models.

In sum, the findings articulate a triad of strengths: (i) consistently strong mean performance with small best-mean gaps (Table 7), (ii) dominant consolidated standings across diverse tasks (Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10), and (iii) favourable scaling without hidden overheads (Figure 5). The synergy among the triple trial-vector generator, line refinement, and adaptive micro-restarts distributes the burden of adaptation across exploration, exploitation, and diversity maintenance, explaining why hyperparameter effects remain modest over wide operating regions.

Limitations. Despite the positive aggregate view, certain boundaries are worth noting. In ELD/DED, performance is more sensitive to and under constrained congestion, while defaults are safe operating points, local retuning can further stabilise progress (see Section 3.3). In a few specialised scenarios (e.g., Cassini 2, circular antenna arrays), individual baselines attain isolated wins signalling landscape idiosyncrasies where added specialisation may help. Finally, the time-scaling study rests on two cases, although indicative, a broader scaling sweep (multiple sizes/dimensions/workloads) would strengthen external validity.

Future Work. Several promising avenues emerge. First, higher-level adaptivity (hyper-heuristics) could learn online operator-mix policies using credit assignment and success signals per generation, deepening the self-stabilising behaviour observed in Section 3.3. Second, targeted self-regulation of and in constrained domains (ELD/DED) via bandit-style or Bayesian controllers may reduce plateau effects while preserving diversity. Third, integrating surrogate models for costly evaluations (e.g., lightweight GP/SVR) can leverage the observed linear scaling to maximise efficiency under tight budgets. Fourth, parallelisation (vectorised trials, GPU-friendly line refinement) promises additional wall-clock gains without altering stochastic dynamics. Fifth, extending to multi-objective and hard/soft constrained variants with explicit feasibility enforcement and adaptive penalties would probe robustness in more realistic settings. Finally, a theoretical strand (e.g., Markov-chain or drift analyses) could formalise the interplay among triple operators, restart, and refinement that is empirically evident. These directions follow naturally from Table 7, Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10, Figure 5, and Section 3.3, aiming to convert empirical advantages into systematically scalable and theoretically grounded benefits.

Author Contributions

V.C. and I.G.T. conducted the experiments employing several datasets and provided the comparative experiments. A.M.G. and V.C. performed the statistical analysis and prepared the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been financed by the European Union: Next Generation EU through the Program Greece 2.0 National Recovery and Resilience Plan, under the call RESEARCH–CREATE– INNOVATE, project name “iCREW: Intelligent small craft simulator for advanced crew training using Virtual Reality techniques” (project code: TAEDK-06195).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tapkin, A. A Comprehensive Overview of Gradient Descent and its Optimization Algorithms. Int. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2023, 10, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawade, S.; Kudtarkar, A.; Sawant, S.; Wadekar, H. The Newton-Raphson Method: A Detailed Analysis. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. (IJRASET) 2024, 12, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonate, P.L. A Brief Introduction to Monte Carlo Simulation. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2001, 40, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglese, R.W. Simulated annealing: A tool for operational research. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1990, 46, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, W.; Shang, S.; Cai, X.; Zhao, H.; Song, Y.; Xu, J. An improved differential evolution algorithm and its application in optimization problem. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 5277–5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, M.; Zaheer, H.; Garcia-Hernandez, L.; Abraham, A. Differential Evolution: A review of more than two decades of research. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 90, 103479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G.; Tzallas, A.; Karvounis, E. Modifications for the Differential Evolution Algorithm. Symmetry 2022, 14, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G. A Parallel Implementation of the Differential Evolution Method. Analytics 2023, 2, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle swarm optimization. In Proceedings of the ICNN’95—International Conference on Neural Networks, Washington, DC, USA, 27 May–1 June 1995; Volume 4, pp. 1942–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G. Toward an Ideal Particle Swarm Optimizer for Multidimensional Functions. Information 2022, 13, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G.; Tzallas, A. An Improved Parallel Particle Swarm Optimization. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Luan, J. A novel differential evolution algorithm with multi-population and elites regeneration. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0302207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Z. An improved differential evolution with adaptive population allocation and mutation selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 258, 125130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.J.; Qin, A.K.; Suganthan, P.N.; Baskar, S. Comprehensive learning particle swarm optimizer for global optimization of multimodal functions. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2006, 10, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, N.; Ostermeier, A. Completely derandomized self-adaptation in evolution strategies. Evol. Comput. 2001, 9, 159–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Serson, A.C. JADE: Adaptive Differential Evolution with Optional External Archive. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2009, 13, 945–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Success-History Based Parameter Adaptation for Differential Evolution. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, Cancun, Mexico, 20–23 June 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanabe, R.; Fukunaga, A.S. Improving the Search Performance of SHADE Using Linear Population Size Reduction. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Beijing, China, 6–11 July 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, Q. Differential Evolution with Composite Trial Vector Generation Strategies and Control Parameters. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2011, 15, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallipeddi, R.; Suganthan, P.N.; Pan, Q.-K.; Tasgetiren, M.F. Differential Evolution Algorithm with Ensemble of Parameters and Mutation Strategies. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 1679–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brest, J.; Maučec, M.S.; Bošković, B. Single Objective Real-Parameter Optimization: Algorithm jSO. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Donostia, Spain, 5–8 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmedova, S.; Stanovov, V.; Semenkin, E. L-SHADE Algorithm with a Rank-Based Selective Pressure Strategy for Solving CEC 2017 Benchmark Problems. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 8–13 July 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, D.; Trivedi, A.; Shivani. A Multi-operator Ensemble LSHADE with Restart and Local Search Mechanisms for Single-objective Optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.15994. [Google Scholar]

- Bujok, P.; Kolenovský, P. Eigen crossover in cooperative model of evolutionary algorithms applied to CEC 2022 single objective numerical optimisation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), Padua, Italy, 18–23 July 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, M.; Trojovská, E.; Trojovský, P.; Malik, O.P. OOBO: A new metaheuristic algorithm for solving optimization problems. Biomimetics 2023, 8, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelder, J.A.; Mead, R. A simplex method for function minimization. Comput. J. 1965, 7, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorigo, M.; Di Caro, G. Ant Colony Optimization. In Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation-CEC99*, Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 July 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1470–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D. An idea based on honey bee swarm for numerical optimization: Artificial bee colony (ABC) algorithm. J. Glob. Optim. 2005, 39, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyrou, G.; Charilogis, V.; Tsoulos, I.G. Improving the Giant-Armadillo Optimization Method. Analytics 2024, 3, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoulos, I.G.; Charilogis, V.; Kyrou, G.; Stavrou, V.N.; Tzallas, A. OPTIMUS: A Multidimensional Global Optimization Package. J. Open Source Softw. 2025, 10, 7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Abraham, A.; Chakraborty, U.K.; Konar, A. Differential evolution using a neighborhood-based mutation operator. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2009, 13, 526–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluabwang, J.; Thomthong, T. Solving parameter identification of frequency modulation sounds problem by modified adaptive tabu search under management agent. Procedia Eng. 2012, 31, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ahandan, M.A.; Alavi-Rad, H.; Jafari, N. Frequency modulation sound parameter identification using shuffled particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Appl. Evol. Comput. 2013, 4, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lennard-Jones, J.E. On the determination of molecular fields. Proc. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1924, 106, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofer, E.P. Optimization of bifunctional catalysts in tubular reactors. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1976, 18, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luus, R.; Dittrich, J.; Keil, F.J. Multiplicity of solutions in the optimization of a bifunctional catalyst blend in a tubular reactor. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 1992, 70, 780–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luus, R.; Bojkov, B. Global optimization of the bifunctional catalyst problem. Can. J. Chem. 1994, 72, 160–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javinsky, M.A.; Kadlec, R.H. Optimal control of a continuous flow stirred tank chemical reactor. Aiche J. 1970, 16, 916–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Soukkou, A.; Khellaf, A.; Leulmi, S.; Boudeghdegh, K. Optimal control of a CSTR process. Braz. Chem. Eng. 2008, 25, 799–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pinheiro, C.I.C.; de Souza, M.B., Jr.; Lima, E.L. Model predictive control of reactor temperature in a CSTR with constraints. Comput. Chem. Eng. 1999, 23, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tersoff, J. New empirical approach for the structure and energy of covalent systems. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 6991–7000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tersoff, J. Modeling solid-state chemistry: Interatomic potentials for multicomponent systems. Phys. Rev. B 1989, 39, 5566–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Stoica, P.; Li, J. Designing unimodular sequence sets with good correlations-Including an application to MIMO radar. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2009, 57, 4391–4405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garver, L.L. Transmission network estimation using linear programming. IEEE Trans. Power Appar. Syst. 1970, 89, 1688–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweppe, F.C.; Caramanis, M.; Tabors, R.D.; Bohn, R.E. Spot Pricing of Electricity; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balanis, C.A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design, 4th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Biscani, F.; Izzo, D.; Yam, C.H. Global Optimization for Space Trajectory Design (GTOP Database and Benchmarks). European Space Agency, Advanced Concepts Team. 2010. Available online: https://www.esa.int/gsp/ACT/projects/gtop/ (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Calles-Esteban, F.; Olmedo, A.A.; Hellín, C.J.; Valledor, A.; Gómez, J.; Tayebi, A. Optimizing antenna positioning for enhanced wireless coverage: A genetic algorithm approach. Sensors 2024, 24, 2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y. Optimization of 5G base station coverage based on self-adaptive genetic algorithm. Comput. Commun. 2024, 218, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Mallipeddi, R.; Suganthan, P.N.; Wang, R.; Chen, H. Problem definitions and evaluation criteria for the CEC 2011 real-world optimization competition (Technical Report). In Proceedings of the IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (CEC), New Orleans, LA, USA, 5–8 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Filliben, J.; Micheals, R.; Phillips, J. Sensitivity Analysis for Biometric Systems: A Methodology Based on Orthogonal Experiment Designs. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2013, 117, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, O.I.; Jantan, A.; Omolara, A.E.; Dada, K.V.; Mohamed, N.A.; Arshad, H. State-of-the-art in artificial neural network applications: A survey. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryadevara, S.; Yanamala, A.K.Y. A Comprehensive Overview of Artificial Neural Networks: Evolution, Architectures, and Applications. Rev. Intel. Artif. Med. 2021, 12, 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, M.; Longjohn, R.; Nottingham, K. The UCI Machine Learning Repository. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- Alcalá-Fdez, J.; Fernandez, A.; Luengo, J.; Derrac, J.; García, S.; Sánchez, L.; Herrera, F. KEEL Data-Mining Software Tool: Data Set Repository, Integration of Algorithms and Experimental Analysis Framework. J. Mult.-Valued Logic Soft Comput. 2011, 17, 255–287. [Google Scholar]

- Sholom, M.W.; Casimir, A.K. Computer Systems That Learn: Classification and Prediction Methods from Statistics, Neural Nets, Machine Learning, and Expert Systems; Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.: Burlington, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tzimourta, K.D.; Tsoulos, I.; Bilero, I.T.; Tzallas, A.T.; Tsipouras, M.G.; Giannakeas, N. Direct Assessment of Alcohol Consumption in Mental State Using Brain Computer Interfaces and Grammatical Evolution. Inventions 2018, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, J.R. Simplifying Decision Trees. Int. J. Man-Mach. Stud. 1987, 27, 221–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultz, T.; Mareschal, D.; Schmidt, W. Modeling Cognitive Development on Balance Scale Phenomena. Mach. Learn. 1994, 16, 59–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.H.; Jiang, Y. NeC4.5: Neural ensemble based C4.5. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2004, 16, 770–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiono, R.; Leow, W.K. FERNN: An Algorithm for Fast Extraction of Rules from Neural Networks. Appl. Intell. 2000, 12, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demiroz, G.; Govenir, H.A.; Ilter, N. Learning Differential Diagnosis of Eryhemato-Squamous Diseases using Voting Feature Intervals. Artif. Intell. Med. 1998, 13, 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Horton, P.; Nakai, K. A Probabilistic Classification System for Predicting the Cellular Localization Sites of Proteins. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1996, 4, 109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes-Roth, B.; Hayes-Roth, B.F. Concept learning and the recognition and classification of exemplars. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1977, 16, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononenko, I.; Šimec, E.; Robnik-Šikonja, M. Overcoming the Myopia of Inductive Learning Algorithms with RELIEFF. Appl. Intell. 1997, 7, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, R.M.; Chater, N. Using noise to compute error surfaces in connectionist networks: A novel means of reducing catastrophic forgetting. Neural Comput. 2002, 14, 1755–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dy, J.G.; Brodley, C.E. Feature Selection for Unsupervised Learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2004, 5, 845–889. [Google Scholar]

- Perantonis, S.J.; Virvilis, V. Input Feature Extraction for Multilayered Perceptrons Using Supervised Principal Component Analysis. Neural Process. Lett. 1999, 10, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcke, J.; Griebel, M. Classification with sparse grids using simplicial basis functions. Intell. Data Anal. 2002, 6, 483–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcdermott, J.; Forsyth, R.S. Diagnosing a disorder in a classification benchmark. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2016, 73, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cestnik, G.; Konenenko, I.; Bratko, I. Assistant-86: A Knowledge-Elicitation Tool for Sophisticated Users. In Progress in Machine Learning; Bratko, I., Lavrac, N., Eds.; Sigma Press: Wilmslow, UK, 1987; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Elter, M.; Schulz-Wendtland, R.; Wittenberg, T. The prediction of breast cancer biopsy outcomes using two CAD approaches that both emphasize an intelligible decision process. Med. Phys. 2007, 34, 4164–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, M.A.; McSharry, P.E.; Roberts, S.J.; Costello, D.; Moroz, I. Exploiting Nonlinear Recurrence and Fractal Scaling Properties for Voice Disorder Detection. BioMed Eng OnLine 2007, 6, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, M.A.; McSharry, P.E.; Hunter, E.J.; Spielman, J.; Ramig, L.O. Suitability of dysphonia measurements for telemonitoring of Parkinson’s disease. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2009, 56, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.W.; Everhart, J.E.; Dickson, W.C.; Knowler, W.C.; Johannes, R.S. Using the ADAP learning algorithm to forecast the onset of diabetes mellitus. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Computer Applications and Medical Care IEEE Computer Society Press, Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 November 1988; pp. 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, D.D.; Klein, R.; Tannahill, J.; Ivanova, D.; Brandon, S.; Domyancic, D.; Zhang, Y. Failure analysis of parameter-induced simulation crashes in climate models. Geosci. Model Dev. 2013, 6, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakeas, N.; Tsipouras, M.G.; Tzallas, A.T.; Kyriakidi, K.; Tsianou, Z.E.; Manousou, P.; Hall, A.; Karvounis, E.C.; Tsianos, V.; Tsianos, E. A clustering based method for collagen proportional area extraction in liver biopsy images. In Proceedings of the Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, EMBS, Milan, Italy, 25–29 November 2015; pp. 3097–3100. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. Non-parametric logistic and proportional odds regression. JRSS-C Appl. Stat. 1987, 36, 260–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, M.; Liu, H.; Scheuermann, P.; Tan, K.L. Fast hierarchical clustering and its validation. Data Knowl. Eng. 2003, 44, 109–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorman, R.P.; Sejnowski, T.J. Analysis of Hidden Units in a Layered Network Trained to Classify Sonar Targets. Neural Netw. 1988, 1, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, P.; Silva, A.M.G. Using data mining to predict secondary school student performance. In Proceedings of the 5th FUture BUsiness TEChnology Conference (FUBUTEC 2008), Porto, Portugal, 9–11 April 2008; pp. 5–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, I.C.; Yang, K.J.; Ting, T.M. Knowledge discovery on RFM model using Bernoulli sequence. Expert. Syst. Appl. 2007, 36, 5866–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasingh, S.; Veluchamy, M. Modified bat algorithm for feature selection with the Wisconsin diagnosis breast cancer (WDBC) dataset. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. APJCP 2017, 18, 1257. [Google Scholar]

- Alshayeji, M.H.; Ellethy, H.; Gupta, R. Computer-aided detection of breast cancer on the Wisconsin dataset: An artificial neural networks approach. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2022, 71, 103141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymer, M.; Doom, T.E.; Kuhn, L.A.; Punch, W.F. Knowledge discovery in medical and biological datasets using a hybrid Bayes classifier/evolutionary algorithm. IEEE Trans. Syst. Cybern. Part Cybern. Publ. IEEE Syst. Man Cybern. Soc. 2003, 33, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, P.; Fukushima, M. Regularized nonsmooth Newton method for multi-class support vector machines. Optim. Methods Softw. 2007, 22, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejak, R.G.; Lehnertz, K.; Mormann, F.; Rieke, C.; David, P.; Elger, C.E. Indications of nonlinear deterministic and finite-dimensional structures in time series of brain electrical activity: Dependence on recording region and brain state. Phys. Rev. E 2001, 64, 061907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzallas, A.T.; Tsipouras, M.G.; Fotiadis, D.I. Automatic Seizure Detection Based on Time-Frequency Analysis and Artificial Neural Networks. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2007, 13, 80510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, M.; Sood, K. Exact Bayesian Structure Discovery in Bayesian Networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2007, 5, 549–573. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).