Abstract

Background/Objectives: Cirrhosis significantly alters physiological function and drug metabolism, particularly for medications primarily metabolized by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. This study aims to establish a physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modelling framework capable of predicting pharmacokinetic changes across different stages of cirrhosis, and to determine optimal dosing regimens that achieve drug exposure levels comparable to those in healthy individuals. Methods: We constructed a physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model that incorporates six drugs, including omeprazole, lansoprazole, midazolam, ondansetron, verapamil, and alfentanil, which are metabolized primarily by CYP2C19 or CYP3A4. The pharmacokinetics of these drugs following oral or injectable administration were simulated in 1000 virtual healthy subjects, and the PBPK model was validated using clinical data. The model was further adapted to account for physiological changes in cirrhotic patients, extending its application to a population of 1000 virtual patients with liver cirrhosis. Results: Most observed data fell within the 5th and 95th percentiles of the virtual patient simulation results. Additionally, for most simulations, the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) and peak concentration (Cmax) were within 0.5- to 2-fold of the observed values. Sensitivity analysis indicated that the reduced expression of metabolizing enzymes increased plasma concentrations of drugs, which was a major factor contributing to the elevated drug exposure in patients with cirrhosis. The clinical dosing regimens of the CYP2C19 substrate omeprazole and the CYP3A4 substrate ondansetron were optimized for use in cirrhotic patients. Conclusions: The developed PBPK model successfully predicted the pharmacokinetics of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrates in both healthy individuals and cirrhotic patients and can be effectively used for dose optimization in cirrhotic populations.

1. Introduction

Globally, approximately 2 million people die each year from liver diseases, with half of these deaths attributed to cirrhosis and the remainder primarily resulting from viral hepatitis and liver cancer [1,2,3]. The World Health Organization (WHO) highlights cirrhosis as a major global health burden, responsible for over 1.4 million deaths annually, primarily driven by viral hepatitis, alcohol use, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [4]. As a progressive liver disease marked by architectural distortion and fibrosis, cirrhosis induces extensive physiological alterations that significantly influence the pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) of numerous drugs, thereby complicating clinical management [5,6].

The severity of cirrhosis is commonly assessed using the Child-Pugh (CP) classification system (grades A to C) [7,8], which provides insights into disease progression, evaluates surgical or medication risks, and informs treatment strategies. Cirrhosis induces a spectrum of physiological changes that collectively influence drug disposition. These changes include reduced hepatic blood flow, decreased hepatocellular enzyme activity, altered plasma protein levels, and impaired biliary excretion. Portal hypertension, a hallmark of cirrhosis, redirects blood flow away from the liver through portosystemic shunting, reducing the effective hepatic extraction of drugs. Additionally, the reduced functional hepatocyte mass diminishes the enzymatic capacity, particularly affecting phase I metabolism mediated by CYP enzymes [9]. Cirrhosis also leads to systemic physiological changes, including altered gastrointestinal absorption, renal function, and distribution volume of drugs [10]. Hypoalbuminemia, a common feature of cirrhosis, affects the protein binding of highly bound drugs, increasing their unbound concentrations.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), such as omeprazole and lansoprazole, are extensively metabolized by CYP2C19, with a minor contribution from CYP3A4. Given their widespread use and narrow therapeutic window in certain populations, dose individualization is essential in patients with hepatic impairment. The 2020 guidelines issued by the National Health Commission of the People’s Republic of China recommend limiting omeprazole to ≤20 mg/day in patients with severe liver injury [11]. However, as this dose represents the standard therapeutic amount, such a generalized recommendation may be insufficient for managing interindividual differences among cirrhotic patients.

The cytochrome P450 enzyme system is highly sensitive to liver function impairment. CYP2C19, responsible for the metabolism of drugs such as PPIs and certain antiepileptics exhibits significant interindividual variability in cirrhotic patients [12,13] and plays a key role in converting clopidogrel into its active thiol metabolite; reduced CYP2C19 activity is strongly associated with clopidogrel resistance and an increased risk of stent thrombosis and other cardiovascular events [14]. CYP3A4, the most abundant hepatic CYP enzyme, metabolizes a wide range of drugs, including midazolam, cyclosporine, and statins, and its activity is regulated by both hepatic and extrahepatic factors such as intestinal metabolism. Consequently, CYP3A4 substrate drugs demonstrate significantly altered pharmacokinetics in cirrhotic patients, with midazolam showing markedly increased systemic exposure and prolonged sedation [15]. These pharmacokinetic alterations highlight the need for individualized dose adjustment and therapeutic drug monitoring for drugs metabolized by CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 [16,17]. Consistent with these observations, progressive liver injury has been shown to markedly downregulate hepatic metabolic enzyme expression [18]. In CP-C patients, hepatic CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 protein levels are reduced to 12% and 25%, respectively, of those in healthy individuals. Additionally, intestinal CYP3A4 expression is decreased approximately 3-fold. Such reductions in metabolic capacity substantially affect the in vivo disposition of affected drugs.

Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling has emerged as a powerful tool to predict the impact of cirrhosis on drug metabolism. By integrating physiological and biochemical data, PBPK models can simulate the altered pharmacokinetics of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrates in cirrhotic patients. These models incorporate key parameters such as reduced hepatic enzyme activity, altered plasma protein binding, and changes in hepatic blood flow. Cirrhosis-induced physiological changes profoundly affect the pharmacokinetics of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrate drugs, posing challenges to their clinical use. Understanding the pharmacokinetic alterations of these drugs is critical for optimizing therapeutic outcomes and minimizing adverse effects. PBPK modeling hold promise for improving the prediction of drug behavior in this population. Among published PBPK models [19,20] for liver injury, many include parameters that have been optimized based on clinical data, rather than being directly measured. Therefore, we attempted to adopt a bottom-up approach to develop the model using parameters from in vitro, and to incorporate as many relevant influencing parameters as possible in the modeling process to make it a highly predictive model.

In this study, we developed a PBPK model for PPIs, specifically omeprazole and lansoprazole, which are primarily metabolized by CYP2C19. The model was extended to simulate the pharmacokinetics of drugs metabolized by CYP3A4 in cirrhotic patients and to optimize drug dosing in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Workflow

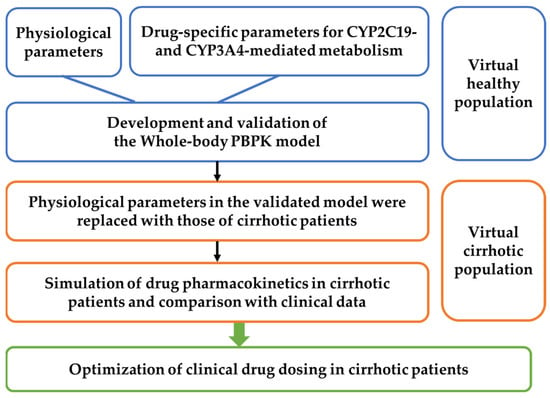

The workflow for developing the PBPK model applicable to healthy subjects and patients with different grades of cirrhosis is shown in Figure 1. A virtual population–based PBPK model was established to characterize pharmacokinetic variability across individuals with different physiological states. A total of 1000 virtual individuals were generated. Clinically reported mean physiological parameters (Table 1) were used as the typical values. Inter-individual variability was introduced by assigning random effects to key pharmacokinetic determinants, including the effective intestinal permeability coefficient (Peff), the blood unbound fraction (fu), hepatic metabolic capacity (Vmax or CLint), the blood-to-plasma concentration ratio (Rb), and the hepatic microsomal protein content (PBSF). These parameters were modeled assuming approximately ±20% variation around their typical values based on clinical and preclinical observations.

Figure 1.

Workflow for developing whole-body PBPK models in healthy individuals and cirrhotic patients and instructing clinical medication.

To simulate inter-individual and intra-individual variability, an exponential model and an additive residual error model were applied. The first-order conditional estimation with the Lindstrom–Bates method (FOCE L-B) was used during population model fitting. Pharmacokinetic simulations were performed for each virtual individual and repeated 10 times to incorporate stochastic uncertainty associated with random sampling, resulting in a total of 10,000 PK profiles. The simulation results were processed in descriptive statistics in Phoenix (Version 8.4, Certara, Princeton, NJ, USA), and the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentiles were derived to describe the population distribution of PK profiles.

The PBPK model was first developed to simulate the pharmacokinetics of omeprazole and lansoprazole in healthy subjects and validated against clinical pharmacokinetic data. After confirmation of adequate predictive performance in a virtual population of 1000 healthy individuals, the model was adapted to liver cirrhosis by updating system specific physiological and biochemical parameters according to disease severity. Subsequently, pharmacokinetics of omeprazole and lansoprazole were predicted in 1000 virtual individuals representing different cirrhosis grades and compared with published clinical observations. Following successful validation in cirrhotic populations, the established PBPK framework was extended to other drugs primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP2C19, and dosage optimization for cirrhotic patients was performed using plasma exposure in healthy subjects as the reference for therapeutic equivalence.

2.2. Model Development

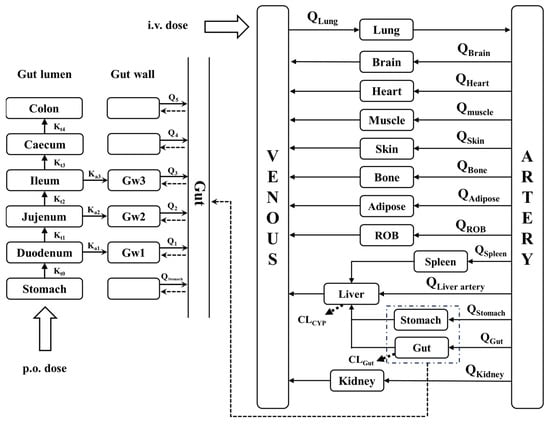

We developed a whole-body PBPK model consisting of intestinal, gut wall, lung, heart, spleen, liver, kidney, brain, adipose, muscle, skin, stomach, arterial blood, venous blood, and the rest of the body (ROB), which are connected by the blood circulatory system (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic structure of the whole-body PBPK model. Kti represents the gastric emptying rate and intestinal transit rate. Gwi represents the gut wall of the duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Kai represents the rate of drug absorption into the gut wall. Q represent the blood flow rate. CL represent the clearance. ROB, rest of body (other tissue).

Drugs are administered either by the intravenous route or the oral route. It is generally accepted that most oral drugs are absorbed in the small intestine (duodenum, jejunum, and ileum) and that the liver is the major metabolizing organ for drugs. In the simulation, it was assumed that the subject drug is eliminated only in the liver and intestine, whereas the absorption of the drug occurs only in the stomach. Drug absorption occurred only in the small intestine. The effective permeability coefficient (Peff) was used to indicate the absorption capability of the drug. The essential structure of the whole-body PBPK model and corresponding mass equations were illustrated in Supplementary Information.

2.3. PBPK Model Development for LC Patients

Alterations to pharmacokinetics in the liver cirrhosis state are mainly caused by changes in hepatic blood flow, liver volume, enzymes and drug unbound fraction.

The drug unbound fraction for patients with liver cirrhosis (fu,cirrhosis) are estimated based on a previously published approach [21]. Among these six drugs, except for verapamil and alfentanil, which primarily binds to α1-acid glycoprotein [22,23], the other drugs primarily bind to albumin [24,25,26,27]. According to the pKa values of the drug it was assumed that it binds to either α1-acid glycoprotein or albumin, and the calculation was carried out via Equation (1).

The blood to plasma ratio (RB:P) was calculated as described before [28]:

HCT represents hematocrit (Table 2). The CErythrocyte/CPlasma was calculated from the Rb values reported in healthy individuals and was fixed to zero if the calculated ratio was less than zero.

For the liver volume and blood flow:

In the liver, drug metabolism is usually described by the following processes:

The changes in gastric emptying and intestinal peristalsis rate constants were calculated as follows:

where Ki,cirrhosis denotes the gastrointestinal transit rate constant in the cirrhotic state, Ki is the gastrointestinal transit rate constant in the normal state, Tgastric,cirrhosis denotes the gastrointestinal emptying time in the cirrhotic state, and Tgastric denotes the gastrointestinal emptying time in the normal state. The gastric emptying time in liver cirrhosis patients was shortened by 1.26 times, thus K0 increased from 0.08 min−1 to 0.1 min−1. The total gastrointestinal emptying time was shortened from 2 days to 1.6 days. After subtracting the gastric emptying time, the intestinal motility rate increased by approximately 1.25 times, with the values listed in Table 2 [29].

2.4. Model Validation

Using the parameters listed in Table 1 and Table 2, plasma concentrations of omeprazole and lansoprazole were predicted in four virtual populations (including normal population, CP-A, CP-B and CP-C patients) following intravenous or oral administration. The drug-specific parameters are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The predictions were performed using Phoenix software (Version 8.3.5, Certara, USA, Inc., Princeton, NJ, USA) and were according to the clinical protocol in literatures. The predictions were further compared with clinical observations. To account for inter-individual variability, we used clinically reported mean physiological parameters as a reference and defined variation ranges (e.g., 80–120% of the mean) to represent subject-to-subject differences. By sampling within these ranges, we generated a virtual population of 1000 individuals, each with a unique set of physiological parameters. For each individual, a pharmacokinetic (PK) profile was simulated and replicated 10 times, resulting in a total of 10,000 virtual PK curves. The simulated data were analyzed using the descriptive statistical module in Phoenix, from which the 5th, 50th, and 95th percentile curves were derived to characterize the distribution of PK profiles across the virtual population.

The model was also applied to other drugs with CYP3A4-mediated metabolism (midazolam, ondansetron, verapamil, alfentanil) to simulate the pharmacokinetic process of the drugs in cirrhosis patients and to optimize the dosage of the drugs in the cirrhosis patients.

The PBPK model was deemed successful if the simulated AUC or Cmax values fell within 0.5- to 2-fold of the observed data or if the observed data lay within the 5th and 95th percentiles of simulations derived from 1000 virtual subjects. At the same time, it also assessed the average fold error (AFE), the average absolute prediction error (PE%) and the geometric mean-fold error (GMFE) of the predictions.

Prediction results are deemed satisfactory for AFE values between 0.8 and 1.25, acceptable for values between 0.5–0.8 or 1.25–2, and poor for values below 0.5 or above 2. In addition, PE% values within 25% are considered satisfactory, values within 25–50% are acceptable, and values beyond 50% indicate poor prediction performance. GMFE values ≤ 1.25 are regarded as satisfactory, 1.25–2 as acceptable, and >2 as poor [30,31].

Table 1.

Physiological parameters of healthy individuals used in the PBPK model [32].

Table 1.

Physiological parameters of healthy individuals used in the PBPK model [32].

| Organs | Volume (mL) | Blood Flow (mL/min) |

|---|---|---|

| Stomach | 160 | 38 |

| Lungs | 1170 | 5600 |

| Muscle | 35,000 | 750 |

| Heart | 310 | 240 |

| Brain | 1450 | 700 |

| Adipose | 10,000 | 260 |

| Skin | 7800 | 300 |

| Liver | 1690 | 300 |

| Kidneys | 280 | 1240 |

| Spleen | 190 | 80 |

| Rest of body | 5100 | 592 |

| Artery blood | 1730 | / |

| Venous blood | 3470 | / |

| Duodenum | 70 | 118 |

| Jejunum | 209 | 413 |

| Ileum | 139 | 244 |

| Cecum | 116 | 44 |

| Colon | 1116 | 281 |

| r1(cm) | 2.00 | / |

| r2(cm) | 1.63 | / |

| r3(cm) | 1.45 | / |

| K0 (min−1) | 0.08 | / |

| K1 (min−1) | 0.07 | / |

| K2 (min−1) | 0.03 | / |

| K3 (min−1) | 0.04 | / |

| K4 (min−1) | 0.003 | / |

| K5 (min−1) | 0.001 | / |

Table 2.

Physiological parameters of patients with cirrhosis used in the PBPK model.

Table 2.

Physiological parameters of patients with cirrhosis used in the PBPK model.

| Parameters | Units | Child–Pugh Class | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | CP-A | CP-B | CP-C | ||

| Qtotal [18] | mL/min | 5600 | 6496 | 7392 | 7896 |

| Hepatic arterial blood flow [33] | mL/min | 300 | 376 | 416 | 509 |

| Liver volume fraction [18] | / | 1.0 | 0.81 | 0.65 | 0.53 |

| Functional liver size [28] | / | 1 | 0.91 | 0.81 | 0.64 |

| Albumin [18] | g/L | 44.7 | 41.1 | 33.9 | 26.3 |

| α1-acid glycoprotein [18] | g/L | 0.8 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.46 |

| Hematocrit [18] | % | 40.9 | 36.6 | 32.9 | 31.9 |

| CYP3A4liver content [34] | pmol/mg protein | 137 | 107 | 70.2 | 42.8 |

| CYP3A4gut content [34] | pmol/mg protein | 65.4 | 65.4 | 39.9 | 31.7 |

| Duodenal CYP3A4 abundance | nmol | 9.7 | 9.7 | 5.92 | 4.70 |

| Jejunal CYP3A4 abundance | nmol | 38.4 | 38.4 | 23.42 | 18.62 |

| Ileal CYP3A4 abundance | nmol | 22.4 | 22.4 | 13.67 | 10.86 |

| CYP2C19liver content [18] | pmol/mg protein | 14 | 4.50 | 3.60 | 1.70 |

| CYP1A2liver content [18] | pmol/mg protein | 52 | 32.9 | 13.6 | 6.10 |

| CYP2D6liver content [18] | pmol/mg protein | 8.0 | 6.10 | 2.60 | 0.84 |

| PBSF | mg protein | 82,472 | 66,802.32 | 53,606.8 | 43,710.16 |

| K0 | min−1 | 0.08 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| K1 | min−1 | 0.07 | 0.088 | 0.088 | 0.088 |

| K2 | min−1 | 0.03 | 0.038 | 0.038 | 0.038 |

| K3 | min−1 | 0.04 | 0.050 | 0.050 | 0.050 |

| K4 | min−1 | 0.003 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| K5 | min−1 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

PBSF is the physiological scale factor, which is calculated based on the Functional liver size ratio. The gastric transit rate constant (K0–5) is based on the ratio of gastrointestinal empty time. The CP parameter changes are based on the ratios reported in the literatures and the healthy individual parameters in Table 1.

2.5. Sensitivity Analysis

Sensitivity analysis was conducted on key parameters, including gastric emptying rate (Kt), plasma unbound fraction of the drug (fu), and metabolic enzyme activities (characterized by Vmax or CLint of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4), based on their actual variation ranges.

2.6. Dose Optimization

Three virtual patient groups were categorized based on different degrees of cirrhosis, with 1000 individuals in each group. Healthy individuals (70 kg) were used as a reference population. The clinical doses for patients were optimized to ensure that their AUC values were comparable to those of healthy individuals receiving the prescribed dose, with deviations within 15%.

3. Results

3.1. Drug Data Set

Two drugs primarily metabolized by CYP2C19 and four drugs primarily metabolized by CYP3A4 were selected from data published in PubMed based on the following criteria:

- (1)

- Pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., AUC or plasma drug concentration) following intravenous and/or oral administration in patients with cirrhosis were available.

- (2)

- Clinical pharmacokinetic data could be obtained from different reports. The collected clinical reports are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Clinical information about CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrates in the simulations.

Table 3. Clinical information about CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrates in the simulations. - (3)

- The pharmacokinetic data were collected from multiple published studies using different analytical methods, which may introduce variability in the validation dataset and influence the comparison between model predictions and observed values.

3.2. CYP2C19 Substrate Drugs

Omeprazole and Lansoprazole

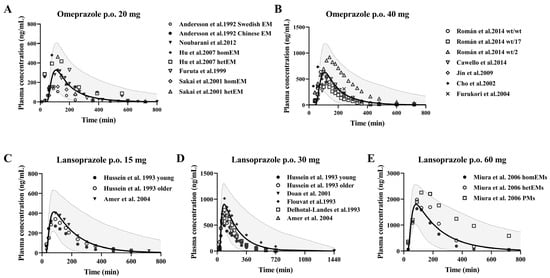

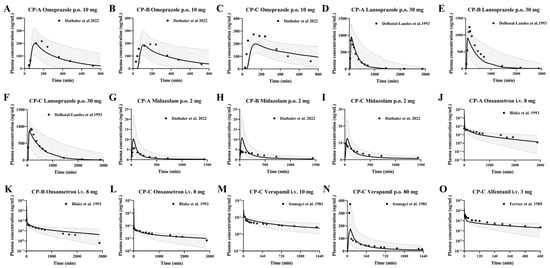

After gastric emptying, enteric formulations should dissolve rapidly in the duodenum. Therefore, the administration time from the stomach to the duodenum is defined as the lag time. We assumed that the drug dissolves rapidly when 90% of the drug reaches the duodenum after gastric emptying [70]. These two drugs are metabolized primarily by CYP2C19 to hydroxylated metabolites, and the rest are metabolized by CYP3A4 to sulphonated metabolites in humans. The pharmacokinetic profile of single-dose oral administration of 20 mg and 40 mg omeprazole in healthy individuals, and single-dose oral administration of 10 mg omeprazole in the three cirrhotic states was predicted using the developed PBPK model. Also, the pharmacokinetics of single dose oral administration of 15 mg, 30 mg, 60 mg lansoprazole in healthy individuals and single dose oral administration of 30 mg lansoprazole in cirrhotic states of three grades were predicted. The predictions were then validated with observations from the clinical research literature, respectively, and the predictions are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Predicted (line) and observed (dot) plasma concentrations of omeprazole and lansoprazole in healthy subjects. Omeprazole (A,B) was administered orally at doses of 20 mg [35,36,37,38,39] and 40 mg [40,41,42,43,44] enteric-coated omeprazole capsules; lansoprazole (C–E) was administered orally at doses of 15 mg [45,46], 30 mg [45,46,47,49,50] and 60 mg [48] enteric-coated omeprazole capsules. The solid line represents the 50th percentile and the dashed lines represent the 5th and 95th percentiles.

3.3. CYP3A4 Substrate Drugs

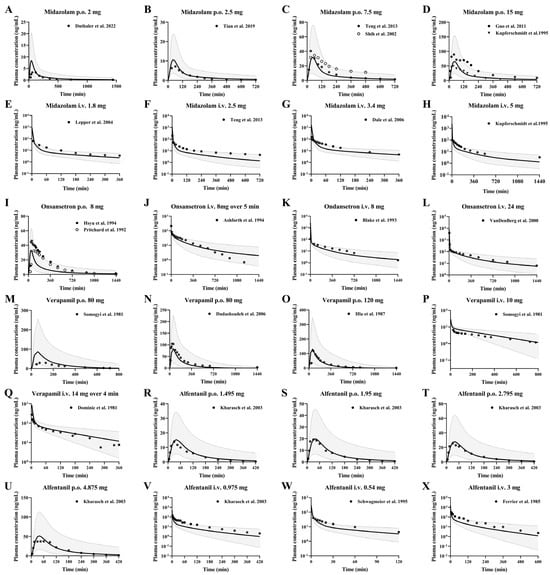

3.3.1. Midazolam and Ondansetron

Midazolam is a typical benzodiazepine anaesthetic with anti-anxiety, sedative and hypnotic properties. Midazolam is predominantly metabolized by hepatic CYP3A4, producing approximately 70% 1-hydroxymidazolam and less than 5% 4-hydroxymidazolam. Ondansetron is primarily metabolized to hydroxylated ondansetron by CYP3A4, with additional contributions from CYP2D6 and CYP1A2. The PBPK model was employed to predict the pharmacokinetic profiles of ondansetron administered as a single 8 mg oral dose, single 8 mg intravenous dose, and single 24 mg intravenous dose in a healthy population, as well as a single 8 mg intravenous dose in individuals with three grades of cirrhosis.

3.3.2. Verapamil and Alfentanil

Verapamil is primarily metabolized in the liver, predominantly by CYP3A4 through N-demethylation to form norverapamil, with additional contributions from CYP3A5 and CYP2C8. Alfentanil is a short-acting opioid analgesic primarily metabolized by the hepatic CYP3A4 enzyme. It also serves as an in vivo probe for assessing hepatic CYP3A4 activity and drug-drug interactions. The developed PBPK model was employed to predict the pharmacokinetics of alfentanil in a healthy population following a single oral dose across four groups, intravenous infusion across three groups, and a single intravenous dose in individuals with cirrhosis under one dosing regimen. The predictions were then validated with observations from the clinical research literature, respectively, and the predictions are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Predicted (line) and observed (dot) plasma concentrations of midazolam, ondansetron, verapamil and alfentanil in healthy subjects. The solid line represents the 50th percentile and the dashed lines represent the 5th and 95th percentiles. Midazolam (A–H) was administered orally at doses of 2 mg [16], 2.5 mg [51], 7.5 mg [52,54], and 15 mg [53,55], and intravenously at doses of 1.8 mg [56], 2.5 mg [54], 3.4 mg [57], and 5 mg [53]. Ondansetron (I–L) was administered orally at dose of 8 mg [59,60], infusion at dose of 8 mg over 5 min [61], intravenously at doses of 8 mg [62], 24 mg [58]. Verapamil (M–Q) was administered orally at doses of 80 mg [65,66], 120 mg [64], intravenously at dose of 10 mg [66], and infusion 14 mg over 4 min [63]. Alfentanil (R–X) was administered orally at doses of 23 μg/kg (1.495 mg), 30 μg/kg (1.95 mg), 43 μg/kg (2.795 mg), 75 μg/kg (4.875 mg) [67], and intravenously at doses of 15 μg/kg (0.975 mg) [67], 0.54 mg [68] and 3 mg [69].

3.4. Development of PBPK Model and Validation Using Pharmacokinetic Parameters from Healthy Subjects Following i.v. or Oral Administrations

Plasma concentration-time profiles after intravenous or oral administration of these six drugs in healthy subjects were simulated using the established PBPK model and compared with clinical observations. The AUC or Cmax values were predicted using 50th percentile profiles and compared with the clinical observations (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9). 95% (143/150) of the predicted pharmacokinetic parameters were within 0.5–2-fold of the observed values. A few outliers were mainly observed for AUC values. These discrepancies may stem from differences in analytical methods used across studies (such as RIA, HPLC-UV, or LC–MS/MS), which can lead to variability in reported concentrations. In addition, population differences or unmodeled physiological variability might also contribute to these deviations.

Table 4.

Observed and predicted values of Cmax, Tmax and AUC0–t of omeprazole in healthy subjects and liver cirrhotic patients.

Table 5.

Observed and predicted values of Cmax, Tmax and AUC0–t of lansoprazole in healthy subjects and liver cirrhotic patients.

Table 6.

Observed and predicted values of Cmax, Tmax and AUC0–t of midazolam in healthy subjects and liver cirrhotic patients.

Table 7.

Observed and predicted values of Cmax, Tmax and AUC0–t of ondansetron in healthy subjects and liver cirrhotic patients.

Table 8.

Observed and predicted values of Cmax, Tmax and AUC0–t of verapamil in healthy subjects and liver cirrhotic patients.

Table 9.

Observed and predicted values of Cmax, Tmax and AUC0–t of alfentanil in healthy subjects and liver cirrhotic patients.

3.5. Prediction of Pharmacokinetic Profiles of Intravenous or Oral CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 Substrates in Cirrhosis Patients Using the Developed PBPK Model

Following validation of the developed PBPK model in healthy subjects, the model was applied to predict the pharmacokinetic profiles of CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 substrate drugs after intravenous or oral administration in 1000 virtual patients with cirrhosis (Figure 5). Pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated using the mean profiles derived from 1000 simulations. The results indicated that the concentrations of most drugs in cirrhosis patients fell within the 5th and 95th percentiles of the pharmacokinetic profiles of the 1000 virtual cirrhotic patients.

Figure 5.

Predicted (line) and observed (dot) plasma concentrations of omeprazole (A–C), lansoprazole (D–F), midazolam (G–I), ondansetron (J–L), verapamil (M,N) and alfentanil (O) in LC subjects. Omeprazole (A−C) was administered orally 10 mg enteric-coated omeprazole capsules [16]. Lansoprazole (D–F) was administered orally 30 mg enteric-coated lansoprazole capsules [50]. Midazolam was administered orally at a dose of 2 mg [16]. Ondansetron was administered intravenously at 8 mg [62]. Verapamil was administered intravenously at 10 mg and orally 80 mg [66]. Alfentanil was administered intravenously at a dose of 3 mg [69]. The solid line represents the 50th percentile and the dashed lines represent the 5th and 95th percentiles.

The AFE, PE and GMFE values of six drugs were calculated using parameters of Cmax, Tmax, and AUC0–t. The results (Table 10) showed that the predictions for all six drugs were within acceptable ranges.

Table 10.

Prediction performance of the six drugs in healthy and cirrhotic subjects.

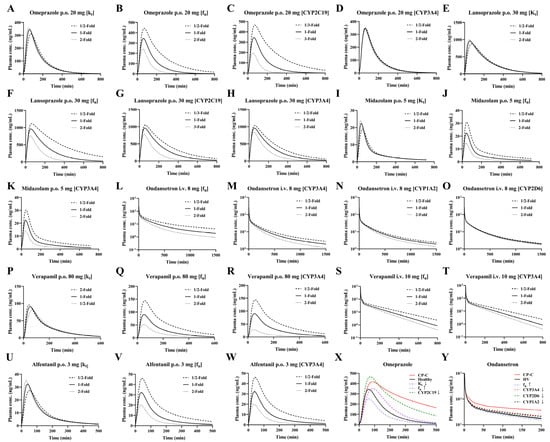

3.6. Sensitivity Analysis of Model Parameters

Plasma concentration-time curves following single-dose oral administration of 20 mg omeprazole, 30 mg lansoprazole, 5 mg midazolam, 80 mg verapamil, and 3 mg alfentanil, as well as intravenous administration of 10 mg verapamil and 8 mg ondansetron, illustrate the sensitivity of pharmacokinetics. Parameters such as gastrointestinal emptying rate, hepatic metabolizing enzyme activity, and plasma unbound drug fraction may influence drug pharmacokinetics. Sensitivity analysis was performed based on the variation ranges of the parameters listed in Table 1 and Table 2. For omeprazole and lansoprazole, sensitivity analyses for CYP2C19 activity were conducted at 1/3-, 1-, and 3-fold to account for the variability in metabolic parameters associated with genetic polymorphisms [70].

The results indicated that the tested parameters affected the pharmacokinetic profiles of the drugs to varying extents (Figure 6). For omeprazole oral, CYP2C19 > fu > Kt > CYP3A4; for lansoprazole oral, fu > CYP2C19 > Kt >> CYP3A4; for midazolam, verapamil and alfentanil oral, fu ≈ CYP3A4 > Kt. For ondansetron, fu > CYP3A4 > CYP1A2 > CYP2D6; for verapamil, CYP3A4 > fu > Kt. For orally administered drugs, the gastric emptying rate (Kt) primarily influenced the time to peak concentration. CYP2C19 played a more significant role than CYP3A4 in the metabolism of omeprazole and lansoprazole, a 66% reduction in CYP2C19 activity has an effect on AUC that is almost equivalent to a 50% reduction in unbound fraction. Whereas CYP3A4 was the primary contributor for the other four drugs, a 50% reduction in CYP3A4 activity has an effect on AUC that is almost equivalent to a 50% reduction in unbound fraction. Additionally, the plasma unbound drug fraction predominantly affected drug distribution to tissues, making it a key parameter for both intravenous and oral administration routes. The contribution of fu, Kt and changes in different metabolic enzymes to the plasma concentrations of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrates and their combined effects were also simulated. The results showed that any decrease in metabolizing enzyme activity resulted in an increase in the plasma concentration; whereas a decrease in fu values resulted in a decrease in the plasma concentration. The net effect was an increase in the plasma concentration. For oral drugs (Omeprazole for example), the decrease in the value of Kt resulted in delayed absorption of the drug and slowed down the rate of absorption in the intestines, with a significant backward shift of Tmax and an increasing trend in the plasma concentration of the drug.

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis (A–Y) after oral administration of 20 mg omeprazole (A–D), 30 mg lansoprazole (E–H), 5 mg midazolam (I–K), 80 mg verapamil (P), 3 mg alfentanil (U–W), and intravenous of 8 mg ondansetron (L–O), 10 mg verapamil (Q–T). Individual contributions of cirrhosis-induced alterations in Kt, enzyme activity and fu to plasma concentrations of omeprazole (X) and ondansetron (Y) following oral 20 mg omeprazole and intravenous of 8 mg ondansetron to LC patients and their integrated effects. HV: healthy volunteer value, CP-C: model predicted value of CP-C with all physiological changes.

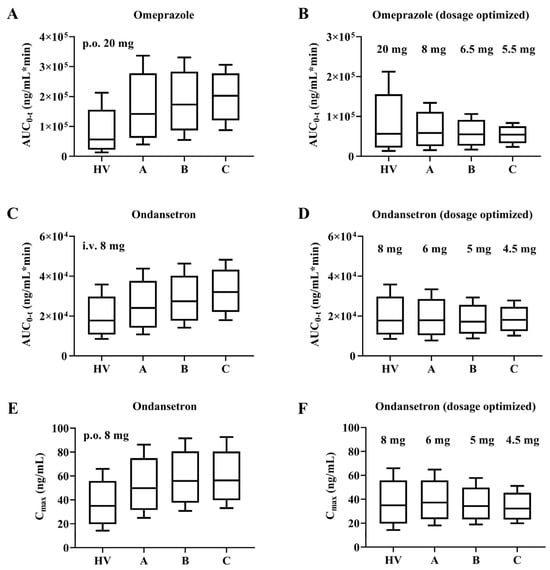

3.7. Dosage Optimization Results

To illustrate the variability in pharmacokinetics within the cirrhosis patient population, we conducted direct comparisons using box-whisker analysis. As shown in Figure 7, at the clinically prescribed dose administered, the AUC ratio of omeprazole (20 mg orally) in patients with CP-A, CP-B, and CP-C versus healthy subjects was 1:2.5:3.1:3.6; and the AUC ratio of ondansetron (8 mg i.v.) was 1:1.4:1.5:1.8. In addition, for the antiemetic ondansetron, the Cmax was strongly correlated with the effect; therefore, a Cmax ratio of 1:1.4:1.6:1.6 was calculated for an oral dose of 8 mg ondansetron.

Figure 7.

Box-Whisker analysis of omeprazole and ondansetron with adjusted dose design. AUC for omeprazole and ondansetron at clinically recommended doses and after dose optimization (A–D). Box-Whisker analysis of Cmax for ondansetron at clinically recommended doses and after adjusted dose design (E,F).

For plasma exposures to be equivalent, the oral dose of omeprazole should be adjusted to 8 mg (CP-A), 6.5 mg (CP-B), and 5.5 mg (CP-C), while the intravenous dose of ondansetron should be adjusted to 6 mg (CP-A), 5 mg (CP-B), and 4.5 mg (CP-C). When 8 mg ondansetron orally, the dosage should be adjusted to 6 mg (CP-A), 5 mg (CP-B), and 4.5 mg (CP-C). This would suggest that for ondansetron, the dose optimized with AUC and Cmax as indicators is consistent.

4. Discussion

Hepatic drug clearance primarily depends on hepatic blood flow, the activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes, and the concentration of unbound drug in plasma [71,72]. In cirrhosis, histological structural abnormalities lead to changes in hepatic blood flow. As the disease progresses, increased vasodilation contributes to the development of hepatorenal syndrome [73], which subsequently elevates cardiac output [74]. Additionally, altered levels of cholecystokinin in cirrhotic patients impair gallbladder contraction, resulting in prolonged gastric emptying time [75]. In patients with cirrhosis, the overall activity of the CYP450 enzyme system is significantly impaired due to a reduction in hepatocyte number, decreased hepatic blood flow, and the loss of functional liver size. Compared with healthy individuals, CYP2C19 expression is reduced by 32%, 26%, and 12% in CP-A, CP-B, and CP-C patients, respectively, while CYP3A4 expression is reduced by 59%, 39%, and 25% [18]. However, changes in drug exposure cannot be solely determined based on cirrhosis grades, as liver extraction ratio of drugs varies, and the activity of different CYP isoforms is affected to varying degrees by the physiological alterations associated with cirrhosis.

The whole-body PBPK model systematically simulates drug pharmacokinetics in healthy individuals by integrating changes in physiological parameters and extending these simulations to patients with varying degrees of cirrhosis. Compared to empirical PK-PD models or semi-PBPK models, whole-body PBPK models provide more detailed information on physiological parameters and drug metabolism mechanisms, leading to enhanced predictive capability [76,77]. These models facilitate in vivo exposure predictions in the early stages of drug clinical trials, without the need for extensive clinical data [78,79,80]. These predictions offer valuable references for clinical trial dose setting in patients with liver dysfunction. Meanwhile, the construction of a whole-body PBPK model can provide valuable insights into the impact of physiological changes on pharmacokinetics under disease conditions and can be used to optimize drug dosing for patient groups in response to disease progression.

Our simulation results demonstrated that nearly all observed plasma concentrations of the drugs fell within the 5th and 95th percentiles of the virtual population simulations generated by the developed PBPK model. Additionally, the predicted-to-observed ratios for most pharmacokinetic parameters, including AUC and Cmax, were within the range of 0.5 to 2.0, indicating that the whole-body PBPK model accurately predicted the pharmacokinetics of midazolam, omeprazole, lansoprazole, ondansetron, verapamil, and alfentanil in both healthy and cirrhotic populations. Sensitivity analysis was conducted using parameter values reported in the literature and the extent of variation in these parameters in healthy and cirrhotic populations. The results revealed that decreased expression of CYP2C19 or CYP3A4 was the primary contributor to the increased in vivo exposure of their substrate drugs, while changes in gastrointestinal transit rates delayed the time to peak concentration. Moreover, elevated plasma unbound drug fractions led to greater drug distribution into tissues, reducing plasma concentrations transiently; however, the net effect was an increase in plasma drug exposure [81].

It is widely acknowledged that dose adjustments are necessary for cirrhotic patients when drug exposure levels exceed twice that of the healthy population. According to our model predictions, the AUC ratios of omeprazole (20 mg orally) in patients with CP-A, CP-B, and CP-C compared to healthy subjects were 1:2.5:3.1:3.6, respectively. In contrast, the AUC ratios of ondansetron (8 mg intravenously) were 1:1.4:1.5:1.8. These findings highlight that, even within the same cirrhosis grade, some drugs may not require additional dose adjustments, whereas others could lead to significant drug accumulation. Although it is reasonable to use AUC and Cmax as indicators for dose optimization, for more extensive situations, it may be necessary to consider indicators such as drug exposure in specific organs or the duration of exposure above threshold concentrations to ensure drug safety. This underscores the potential utility of the PBPK model for optimizing clinical dosing in cirrhotic patients.

However, this study has certain limitations. Due to the limited availability of human physiological data and corresponding clinical studies in cirrhotic patients, the PBPK model primarily accounted for changes in parameters such as hepatic blood flow, CYP450 enzyme activity, cardiac output, and plasma unbound drug fraction. Other potential influencing factors, such as the impact of cirrhosis on metabolizing enzyme activity across different ages or genotypes, were not included [82]. It was demonstrated that for the CYP2C9 substrate drug, lornoxicam, the effect of cirrhosis grade on pharmacokinetics was greater than the effect of genotypic differences [83]. And this study focused on the effect of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 impairment on drug exposure, the model structure already includes dynamic enzyme activity and substrate-competition terms, indicating its potential for drug–drug interaction assessment when reliable inhibition/induction parameters are available. Future extensions of the model may therefore support optimisation of combination therapy in cirrhotic patients. Although the complexity of the discussion limits genotypic depth, our model provided a basis for accurate assessment of genotypes for CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrate drugs subsequent studies. Additionally, although the Child-Pugh class was used as a category in our study to simulate pharmacokinetic changes in different hepatic function states, it is important to note that this system of comprehensive categories based on a wide range of clinical physiological parameters does not adequately reflect the variability of physiological parameters of the patients in each class. The PBPK model was developed using typical parameter values and an assumed 20% variation, which may underestimate the inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability observed in real populations. Future refinements could incorporate known genetic variability to improve prediction accuracy. In future applications expansion, the individual variability values of real patients could be integrated to improve prediction accuracy and clinical adaptability. In data collection, we included as many relevant publications as possible. However, different detection methods vary in terms of sensitivity, specificity, and interference resistance. For example, RIA methods may have cross-reactivity or poor specificity, which may affect the accuracy of some blood drug concentration data.

5. Conclusions

A whole-body PBPK model of CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 substrates containing omeprazole, lansoprazole, midazolam, ondansetron, verapamil, and alfentanil was developed in healthy subjects. After validation with clinical data reported in literatures, the PBPK model was applied to patients with different grades of cirrhosis to predict pharmacokinetic profiles. The developed PBPK model can also be used to guide dose optimization in the liver cirrhosis patient population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pharmaceutics17121582/s1, Kt:p values were calculated using the method of Rodgers et al [84]. Table S1. Drug-specific parameters primarily mediated by CYP2C19 metabolism [70,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92]; Table S2. Drug-specific parameters primarily mediated by CYP3A4 metabolism [93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, validation, data curation, R.M. and X.W.; Data curation, validation, N.H. and H.Y.; Methodology, investigation, resources, writing—original draft preparation J.G., R.M. and J.L.; Software, visualization, R.M. Visualization, writing—review and editing, supervision, project administration, N.H. and H.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82204511), and the China pharmaceutical university “Double First-Class” university project (No. CPU2022QZ21), and Top Talent of Changzhou “The 14th Five-Year Plan” High-Level Health Talents Training Project (2022CZBJ042) and Jiangsu Pharmaceutical Association “Pharmaceutical Research New Voice” Pharmaceutical Scientific Research Project (202564038).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Nan Hu and Hanyu Yang for their helpful advice in writing the English manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC | the area under the curve |

| AUC0–t | the area under the curve from 0 to the last measurable concentration |

| Cmax | the peak concentration |

| Tmax | time to peak drug concentration |

| CYP2C19 | Cytochrome P450 2C19 |

| CYP3A4 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 |

| LC | liver cirrhosis |

| fu | the unbound fraction of drug |

| CL | clearance |

| Rb | the ratio of drug concentration in blood to plasma |

| PBSF | the physiologically based scaling factor |

| Kt | the transit rate constant |

| Kt:p | the ratio of drug concentration in tissue to plasma |

| PBPK | physiologically based pharmacokinetic |

References

- Ginès, P.; Krag, A.; Abraldes, J.G.; Solà, E.; Fabrellas, N.; Kamath, P.S. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2021, 398, 1359–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarbhavi, H.; Asrani, S.K.; Arab, J.P.; Nartey, Y.A.; Pose, E.; Kamath, P.S. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol. 2023, 79, 516–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.Q.; Terrault, N.A.; Tacke, F.; Gluud, L.L.; Arrese, M.; Bugianesi, E.; Loomba, R. Global epidemiology of cirrhosis—Aaetiology, trends and predictions. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Hepatitis Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/hepatitis (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Roehlen, N.; Crouchet, E.; Baumert, T.F. Liver Fibrosis: Mechanistic Concepts and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020, 9, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, D.; Baglieri, J.; Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D.A. Mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its role in liver cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. 2020, 245, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pugh, R.N.; Murray-Lyon, I.M.; Dawson, J.L.; Pietroni, M.C.; Williams, R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br. J. Surg. 1973, 60, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, H.; Osaki, Y. Liver Cirrhosis: Evaluation, Nutritional Status, and Prognosis. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 872152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelmann, C.; Clària, J.; Szabo, G.; Bosch, J.; Bernardi, M. Pathophysiology of decompensated cirrhosis: Portal hypertension, circulatory dysfunction, inflammation, metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75 (Suppl. S1), S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsochatzis, E.A.; Bosch, J.; Burroughs, A.K. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet 2014, 383, 1749–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidelines for the Clinical Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors. Available online: https://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/c100068/202012/b59f1401666645009b64aee17185c87b.shtml (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- El Rouby, N.; Lima, J.J.; Johnson, J.A. Proton pump inhibitors: From CYP2C19 pharmacogenetics to precision medicine. Expert. Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 447–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desta, Z.; Zhao, X.; Shin, J.G.; Flockhart, D.A. Clinical significance of the cytochrome P450 2C19 genetic polymorphism. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2002, 41, 913–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mega, J.L.; Close, S.L.; Wiviott, S.D.; Shen, L.; Hockett, R.D.; Brandt, J.T.; Walker, J.R.; Antman, E.M.; Macias, W.; Braunwald, E.; et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 354–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, N.A.; Kennedy, H.J.; Nicholl, J.; Triger, D.R. Sedation for gastroscopy: A comparative study of midazolam and Diazemuls in patients with and without cirrhosis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1986, 22, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duthaler, U.; Bachmann, F.; Suenderhauf, C.; Grandinetti, T.; Pfefferkorn, F.; Haschke, M.; Hruz, P.; Bouitbir, J.; Krähenbühl, S. Liver Cirrhosis Affects the Pharmacokinetics of the Six Substrates of the Basel Phenotyping Cocktail Differently. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2022, 61, 1039–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delcò, F.; Tchambaz, L.; Schlienger, R.; Drewe, J.; Krähenbühl, S. Dose adjustment in patients with liver disease. Drug Saf. 2005, 28, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.N.; Boussery, K.; Rowland-Yeo, K.; Tucker, G.T.; Rostami-Hodjegan, A. A semi-mechanistic model to predict the effects of liver cirrhosis on drug clearance. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2010, 49, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wei, Y.; He, K.; Zhao, X.; Mu, H.; Wen, Q. Prediction of janagliflozin pharmacokinetics in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with liver cirrhosis or renal impairment using a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 179, 106298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, M.N.; Rasool, M.F.; Alqahtani, F.; Imran, I.; Rehman, A.U.; Ahmed, N. Development and Evaluation of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Drug-Disease Model of Propranolol for Suggesting Model Informed Dosing in Liver Cirrhosis Patients. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 1195–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Mu, R.; Hu, G.; Liu, L.; Liu, X. Simultaneously Predicting the Pharmacokinetics of CES1-Metabolized Drugs and Their Metabolites Using Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model in Cirrhosis Subjects. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGowan, F.X.; Reiter, M.J.; Pritchett, E.L.; Shand, D.G. Verapamil plasma binding: Relationship to alpha 1-acid glycoprotein and drug efficacy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1983, 33, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belpaire, F.M.; Bogaert, M.G. Binding of alfentanil to human alpha 1-acid glycoprotein, albumin and serum. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. Toxicol. 1991, 29, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cartee, N.M.P.; Wang, M.M. Binding of omeprazole to protein targets identified by monoclonal antibodies. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landes, B.D.; Petite, J.P.; Flouvat, B. Clinical pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1995, 28, 458–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaoka, N.; Oda, Y.; Hase, I.; Mizutani, K.; Nakamoto, T.; Ishizaki, T.; Asada, A. Propofol decreases the clearance of midazolam by inhibiting CYP3A4: An in vivo and in vitro study. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 66, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, K.H.; Hicks, F.M. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ondansetron. A review. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1996, 48, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Barton, H.A.; Maurer, T.S. A Mechanistic Pharmacokinetic Model for Liver Transporter Substrates Under Liver Cirrhosis Conditions. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2015, 4, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsen, S.; Fynne, L.; Grønbæk, H.; Krogh, K. Small intestinal transit in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension: A descriptive study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepin, X.J.H.; Johansson Soares Medeiros, J.; Deris Prado, L.; Suarez Sharp, S. The Development of an Age-Appropriate Fixed Dose Combination for Tuberculosis Using Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling (PBBM) and Risk Assessment. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, L. Prediction of Pharmacokinetics for CYP3A4-Metabolized Drugs in Pediatrics and Geriatrics Using Dynamic Age-Dependent Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Models. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, W.M.; Sun, B.B.; Wang, Z.J.; Zheng, X.K.; Zhao, K.J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Liu, P.H.; Zhu, L.; Xu, R.J.; et al. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling for prediction of vonoprazan pharmacokinetics and its inhibition on gastric acid secretion following intravenous/oral administration to rats, dogs and humans. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 852–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, B.G.; Hatley, O.; Jamei, M.; Gardner, I.; Johnson, T.N. Incorporation and Performance Verification of Hepatic Portal Blood Flow Shunting in Minimal and Full PBPK Models of Liver Cirrhosis. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 114, 1264–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladumor, M.K.; Storelli, F.; Liang, X.; Lai, Y.; Enogieru, O.J.; Chothe, P.P.; Evers, R.; Unadkat, J.D. Predicting changes in the pharmacokinetics of CYP3A-metabolized drugs in hepatic impairment and insights into factors driving these changes. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2023, 12, 261–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Regårdh, C.G.; Lou, Y.C.; Zhang, Y.; Dahl, M.L.; Bertilsson, L. Polymorphic hydroxylation of S-mephenytoin and omeprazole metabolism in Caucasian and Chinese subjects. Pharmacogenetics 1992, 2, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubarani, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Motevalian, M.; Keyhanfar, F. Variation in omeprazole pharmacokinetics in a random Iranian population: A pilot study. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2012, 33, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.P.; Xu, J.M.; Hu, Y.M.; Mei, Q.; Xu, X.H. Effects of CYP2C19 genetic polymorphism on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of omeprazole in Chinese people. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2007, 32, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Aoyama, N.; Kita, T.; Sakaeda, T.; Nishiguchi, K.; Nishitora, Y.; Hohda, T.; Sirasaka, D.; Tamura, T.; Tanigawara, Y.; et al. CYP2C19 genotype and pharmacokinetics of three proton pump inhibitors in healthy subjects. Pharm. Res. 2001, 18, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuta, T.; Ohashi, K.; Kobayashi, K.; Iida, I.; Yoshida, H.; Shirai, N.; Takashima, M.; Kosuge, K.; Hanai, H.; Chiba, K.; et al. Effects of clarithromycin on the metabolism of omeprazole in relation to CYP2C19 genotype status in humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1999, 66, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román, M.; Ochoa, D.; Sánchez-Rojas, S.D.; Talegón, M.; Prieto-Pérez, R.; Rivas, Â.; Abad-Santos, F.; Cabaleiro, T. Evaluation of the relationship between polymorphisms in CYP2C19 and the pharmacokinetics of omeprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole. Pharmacogenomics 2014, 15, 1893–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cawello, W.; Mueller-Voessing, C.; Fichtner, A. Pharmacokinetics of lacosamide and omeprazole coadministration in healthy volunteers: Results from a phase I, randomized, crossover trial. Clin. Drug Investig. 2014, 34, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.K.; Kang, T.S.; Eom, S.O.; Kim, J.I.; Lee, H.J.; Roh, J. CYP2C19 haplotypes in Koreans as a marker of enzyme activity evaluated with omeprazole. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2009, 34, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.Y.; Yu, K.S.; Jang, I.J.; Yang, B.H.; Shin, S.G.; Yim, D.S. Omeprazole hydroxylation is inhibited by a single dose of moclobemide in homozygotic EM genotype for CYP2C19. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 53, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui-Furukori, N.; Takahata, T.; Nakagami, T.; Yoshiya, G.; Inoue, Y.; Kaneko, S.; Tateishi, T. Different inhibitory effect of fluvoxamine on omeprazole metabolism between CYP2C19 genotypes. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004, 57, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, Z.; Granneman, G.R.; Mukherjee, D.; Samara, E.; Hogan, D.L.; Koss, M.A.; Isenberg, J.I. Age-related differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lansoprazole. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 36, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, F.; Karol, M.D.; Pan, W.J.; Griffin, J.S.; Lukasik, N.L.; Locke, C.S.; Chiu, Y.L. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole 15- and 30-mg sachets for suspension versus intact capsules. Clin. Ther. 2004, 26, 2076–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, T.T.; Wang, Q.; Griffin, J.S.; Lukasik, N.L.; O’Dea, R.F.; Pan, W.J. Comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of lansoprazole oral capsules and suspension in healthy subjects. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2001, 58, 1512–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, M. Enantioselective disposition of lansoprazole and rabeprazole in human plasma. Yakugaku Zasshi 2006, 126, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flouvat, B.; Delhotal-Landes, B.; Cournot, A.; Dellatolas, F. Single and multiple dose pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole in elderly subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 36, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delhotal-Landes, B.; Flouvat, B.; Duchier, J.; Molinie, P.; Dellatolas, F.; Lemaire, M. Pharmacokinetics of lansoprazole in patients with renal or liver disease of varying severity. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 45, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, D.D.; Leonowens, C.; Cox, E.J.; González-Pérez, V.; Frederick, K.S.; Scarlett, Y.V.; Fisher, M.B.; Paine, M.F. Indinavir Increases Midazolam N-Glucuronidation in Humans: Identification of an Alternate CYP3A Inhibitor Using an In Vitro to In Vivo Approach. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2019, 47, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, P.S.; Huang, J.D. Pharmacokinetics of midazolam and 1’-hydroxymidazolam in Chinese with different CYP3A5 genotypes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2002, 30, 1491–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupferschmidt, H.H.; Ha, H.R.; Ziegler, W.H.; Meier, P.J.; Krähenbühl, S. Interaction between grapefruit juice and midazolam in humans. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1995, 58, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, R.; Butler, K. The effect of ticagrelor on the metabolism of midazolam in healthy volunteers. Clin. Ther. 2013, 35, 1025–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Mao, G.F.; Xia, D.Y.; Su, X.Y.; Zhao, L.S. Pharmacokinetics of midazolam tablet in different Chinese ethnic groups. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2011, 36, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepper, E.R.; Hicks, J.K.; Verweij, J.; Zhai, S.; Figg, W.D.; Sparreboom, A. Determination of midazolam in human plasma by liquid chromatography with mass-spectrometric detection. J. Chromatogr. B 2004, 806, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, O.; Nilsen, T.; Loftsson, T.; Hjorth Tønnesen, H.; Klepstad, P.; Kaasa, S.; Holand, T.; Djupesland, P.G. Intranasal midazolam: A comparison of two delivery devices in human volunteers. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2006, 58, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDenBerg, C.M.; Kazmi, Y.; Stewart, J.; Weidler, D.J.; Tenjarla, S.N.; Ward, E.S.; Jann, M.W. Pharmacokinetics of three formulations of ondansetron hydrochloride in healthy volunteers: 24-mg oral tablet, rectal suppository, and i.v. infusion. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2000, 57, 1046–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsyu, P.H.; Pritchard, J.F.; Bozigian, H.P.; Lloyd, T.L.; Griffin, R.H.; Shamburek, R.; Krishna, G.; Barr, W.H. Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of an ondansetron solution (8 mg) when administered intravenously, orally, to the colon, and to the rectum. Pharm. Res. 1994, 11, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, J.F.; Bryson, J.C.; Kernodle, A.E.; Benedetti, T.L.; Powell, J.R. Age and gender effects on ondansetron pharmacokinetics: Evaluation of healthy aged volunteers. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1992, 51, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, E.I.; Palmer, J.L.; Bye, A.; Bedding, A. The pharmacokinetics of ondansetron after intravenous injection in healthy volunteers phenotyped as poor or extensive metabolisers of debrisoquine. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1994, 37, 389–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake, J.C.; Palmer, J.L.; Minton, N.A.; Burroughs, A.K. The pharmacokinetics of intravenous ondansetron in patients with hepatic impairment. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1993, 35, 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominic, J.A.; Bourne, D.W.; Tan, T.G.; Kirsten, E.B.; McAllister, R.G., Jr. The pharmacology of verapamil. III. Pharmacokinetics in normal subjects after intravenous drug administration. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1981, 3, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hla, K.K.; Henry, J.A.; Latham, A.N. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of two formulations of verapamil. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1987, 24, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadashzadeh, S.; Javadian, B.; Sadeghian, S. The effect of gender on the pharmacokinetics of verapamil and norverapamil in human. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2006, 27, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somogyi, A.; Albrecht, M.; Kliems, G.; Schäfer, K.; Eichelbaum, M. Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability and ECG response of verapamil in patients with liver cirrhosis. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1981, 12, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharasch, E.D.; Hoffer, C.; Walker, A.; Sheffels, P. Disposition and miotic effects of oral alfentanil: A potential noninvasive probe for first-pass cytochrome P4503A activity. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 73, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwagmeier, R.; Boerger, N.; Meissner, W.; Striebel, H.W. Pharmacokinetics of intranasal alfentanil. J. Clin. Anesth. 1995, 7, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, C.; Marty, J.; Bouffard, Y.; Haberer, J.P.; Levron, J.C.; Duvaldestin, P. Alfentanil pharmacokinetics in patients with cirrhosis. Anesthesiology 1985, 62, 480–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xie, L.; Yang, L.; Jiang, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhi, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Liu, L. Prediction of Omeprazole Pharmacokinetics and its Inhibition on Gastric Acid Secretion in Humans Using Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic-Pharmacodynamic Model Characterizing CYP2C19 Polymorphisms. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 1735–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nies, A.S.; Shand, D.G.; Wilkinson, G.R. Altered hepatic blood flow and drug disposition. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1976, 1, 135–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, M. Protein binding and drug clearance. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1984, 9 (Suppl. S1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapper, E.B.; Parikh, N.D. Diagnosis and Management of Cirrhosis and Its Complications: A Review. JAMA 2023, 329, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardi, E.M.; Abbate, A.; Zardi, D.M.; Dobrina, A.; Margiotta, D.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Afeltra, A.; Sanyal, A.J. Cirrhotic cardiomyopathy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010, 56, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acalovschi, M.; Dumitraşcu, D.L.; Csakany, I. Gastric and gall bladder emptying of a mixed meal are not coordinated in liver cirrhosis--a simultaneous sonographic study. Gut 1997, 40, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Chen, Y.; Unadkat, J.D.; Zhang, X.; Wu, D.; Heimbach, T. Applications, Challenges, and Outlook for PBPK Modeling and Simulation: A Regulatory, Industrial and Academic Perspective. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 1701–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loisios-Konstantinidis, I.; Dressman, J. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling to Support Waivers of In Vivo Clinical Studies: Current Status, Challenges, and Opportunities. Mol. Pharm. 2021, 18, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, R.N.; Foster, D.J.; Abuhelwa, A.Y. An introduction to physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2016, 26, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, M.B.; Cabalu, T.D.; de Zwart, L.; Ramsden, D.; Dowty, M.E.; Taskar, K.S.; Badée, J.; Bolleddula, J.; Boulu, L.; Fu, Q.; et al. Building Confidence in Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling of CYP3A Induction Mediated by Rifampin: An Industry Perspective. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 117, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Yu, Z.; Yao, X.; Lei, Z.; Zhao, K.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, D. Prediction of pyrotinib exposure based on physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model and endogenous biomarker. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 972411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland Yeo, K.; Gil Berglund, E.; Chen, Y. Dose Optimization Informed by PBPK Modeling: State-of-the Art and Future. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 116, 563–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgieva, M.; Xenodochidis, C.; Krasteva, N. Old age as a risk factor for liver diseases: Modern therapeutic approaches. Exp. Gerontol. 2023, 184, 112334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.H.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, Y.B. Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling of Lornoxicam: Exploration of doses for CYP2C9 Genotypes and Patients with Cirrhosis. J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 111, 3174–3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, T.; Leahy, D.; Rowland, M. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling 1: Predicting the tissue distribution of moderate-to-strong bases. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 1259–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Johnson, T.N.; Bui, K.H.; Cheung, S.Y.A.; Li, J.; Xu, H.; Al-Huniti, N.; Zhou, D. Predictive Performance of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling of Drugs Extensively Metabolized by Major Cytochrome P450s in Children. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 104, 188–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Gaohua, L.; Zhao, P.; Jamei, M.; Huang, S.M.; Bashaw, E.D.; Lee, S.C. Predicting nonlinear pharmacokinetics of omeprazole enantiomers and racemic drug using physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling and simulation: Application to predict drug/genetic interactions. Pharm. Res. 2014, 31, 1919–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, F.; Zhu, L.; Li, N.; Ge, T.; Xu, G.; Liao, S. Influence of different proton pump inhibitors on the pharmacokinetics of voriconazole. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2017, 49, 403–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katashima, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Sugiura, M.; Sawada, Y.; Iga, T. Comparative pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic study of proton pump inhibitors, omeprazole and lansoprazole in rats. Drug Metab. Dispos. 1995, 23, 718–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanioka, N.; Tsuneto, Y.; Saito, Y.; Maekawa, K.; Sawada, J.; Narimatsu, S. Influence of CYP2C19*18 and CYP2C19*19 alleles on omeprazole 5-hydroxylation: In vitro functional analysis of recombinant enzymes expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Basic. Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2008, 102, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.A.; Kim, M.J.; Park, J.Y.; Shon, J.H.; Yoon, Y.R.; Lee, S.S.; Liu, K.H.; Chun, J.H.; Hyun, M.H.; Shin, J.G. Stereoselective metabolism of lansoprazole by human liver cytochrome P450 enzymes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2003, 31, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steere, B.; Baker, J.A.; Hall, S.D.; Guo, Y. Prediction of in vivo clearance and associated variability of CYP2C19 substrates by genotypes in populations utilizing a pharmacogenetics-based mechanistic model. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2015, 43, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, H.; Inoue, K.; Shaw, P.M.; Checovich, W.J.; Guengerich, F.P.; Shimada, T. Different contributions of cytochrome P450 2C19 and 3A4 in the oxidation of omeprazole by human liver microsomes: Effects of contents of these two forms in individual human samples. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997, 283, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanke, N.; Turk, D.; Selzer, D.; Wiebe, S.; Fernandez, É.; Stopfer, P.; Nock, V.; Lehr, T. A Mechanistic, Enantioselective, Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model of Verapamil and Norverapamil, Built and Evaluated for Drug-Drug Interaction Studies. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, C.Q.; Zhao, K.J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.D. Simultaneously predict pharmacokinetic interaction of rifampicin with oral versus intravenous substrates of cytochrome P450 3A/P-glycoprotein to healthy human using a semi-physiologically based pharmacokinetic model involving both enzyme and transporter turnover. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 134, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezuruike, U.; Zhang, M.; Pansari, A.; De Sousa Mendes, M.; Pan, X.; Neuhoff, S.; Gardner, I. Guide to development of compound files for PBPK modeling in the Simcyp population-based simulator. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 2022, 11, 805–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, S.; Shen, D.D.; Isoherranen, N. Predicting Maternal-Fetal Disposition of Fentanyl Following Intravenous and Epidural Administration Using Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2021, 49, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Hu, M.; Xu, P.; Liu, L.; Liu, X. A mechanistic physiologically based pharmacokinetic-enzyme turnover model involving both intestine and liver to predict CYP3A induction-mediated drug-drug interactions. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 2819–2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obach, R.S.; Lombardo, F.; Waters, N.J. Trend analysis of a database of intravenous pharmacokinetic parameters in humans for 670 drug compounds. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2008, 36, 1385–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baneyx, G.; Parrott, N.; Meille, C.; Iliadis, A.; Lave, T. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling of CYP3A4 induction by rifampicin in human: Influence of time between substrate and inducer administration. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 56, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yerasi, N.; Vurimindi, H.; Devarakonda, K. Frog intestinal perfusion to evaluate drug permeability: Application to p-gp and cyp3a4 substrates. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, J.; Shi, J.; Hu, P. Evaluating a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for predicting the pharmacokinetics of midazolam in Chinese after oral administration. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2016, 37, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).