MOF-Engineered Platelet-Mimicking Nanocarrier-Encapsulated Cascade Enzymes for ROS Scavenging and Anti-Inflammation in Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Cell Lines and OGD/R Model

2.3. Animals and MCAO Model

2.4. Platelet Isolation and Membrane Extraction

2.5. Synthesis and Characterization of PLSCZ

2.6. Hemolysis Assay

2.7. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.8. Enzyme Activity Assays

2.9. Evaluation of Antioxidant Stress and Neuroprotection In Vitro

2.10. Microglial Polarization Analysis

2.11. Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Trafficking

2.12. In Vitro and In Vivo Targeting and Permeability

2.13. Neuroprotection Evaluation

2.14. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.15. Western Blotting

2.16. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and Characterization of SZ, CZ, SCZ, PLSCZ

3.2. SCZ Exerts Neuroprotective Effects Through Anti-Oxidative Stress

3.3. Cellular Uptake and Intracellular Processes

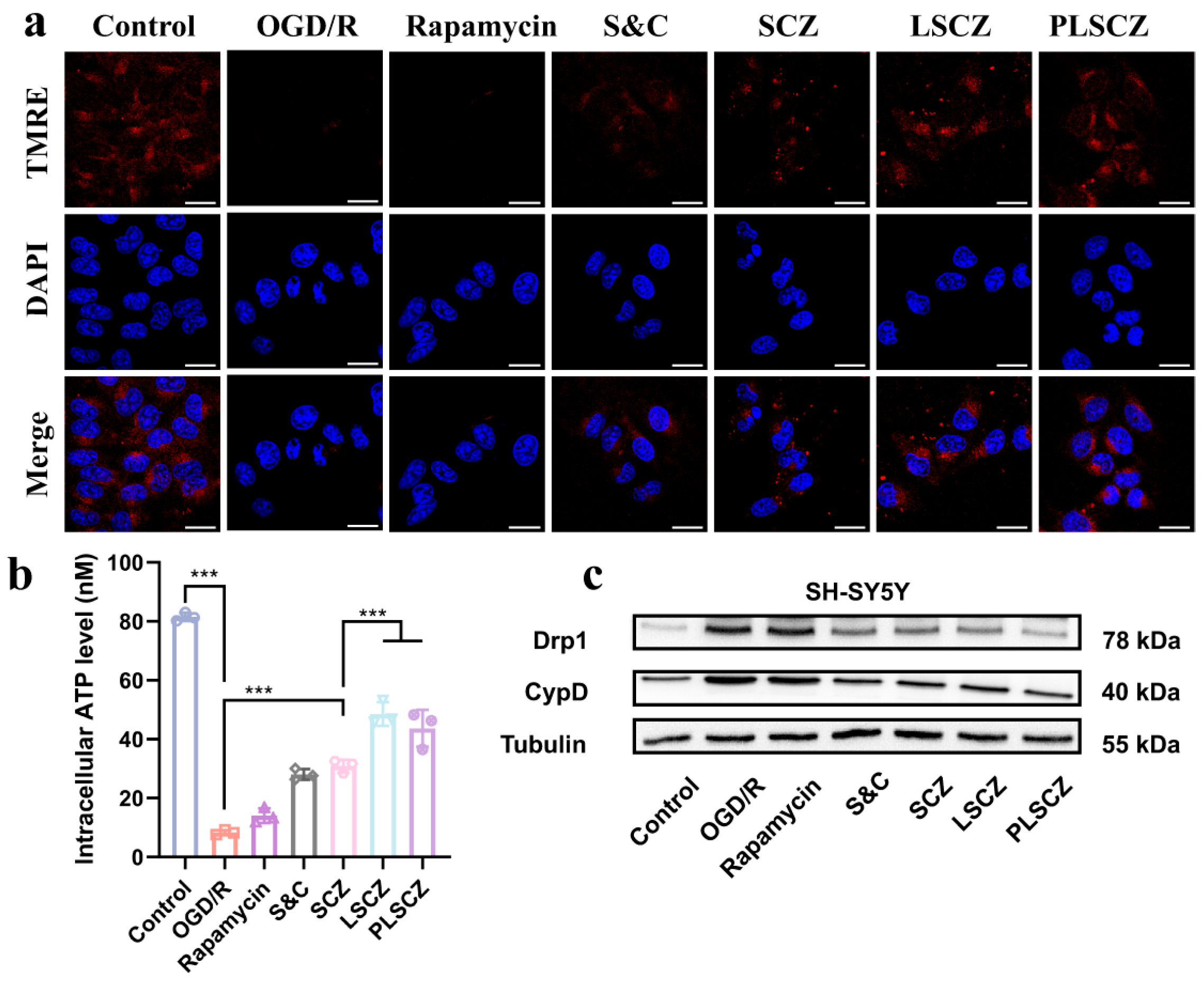

3.4. Mitochondrial Protection and Energy Recovery

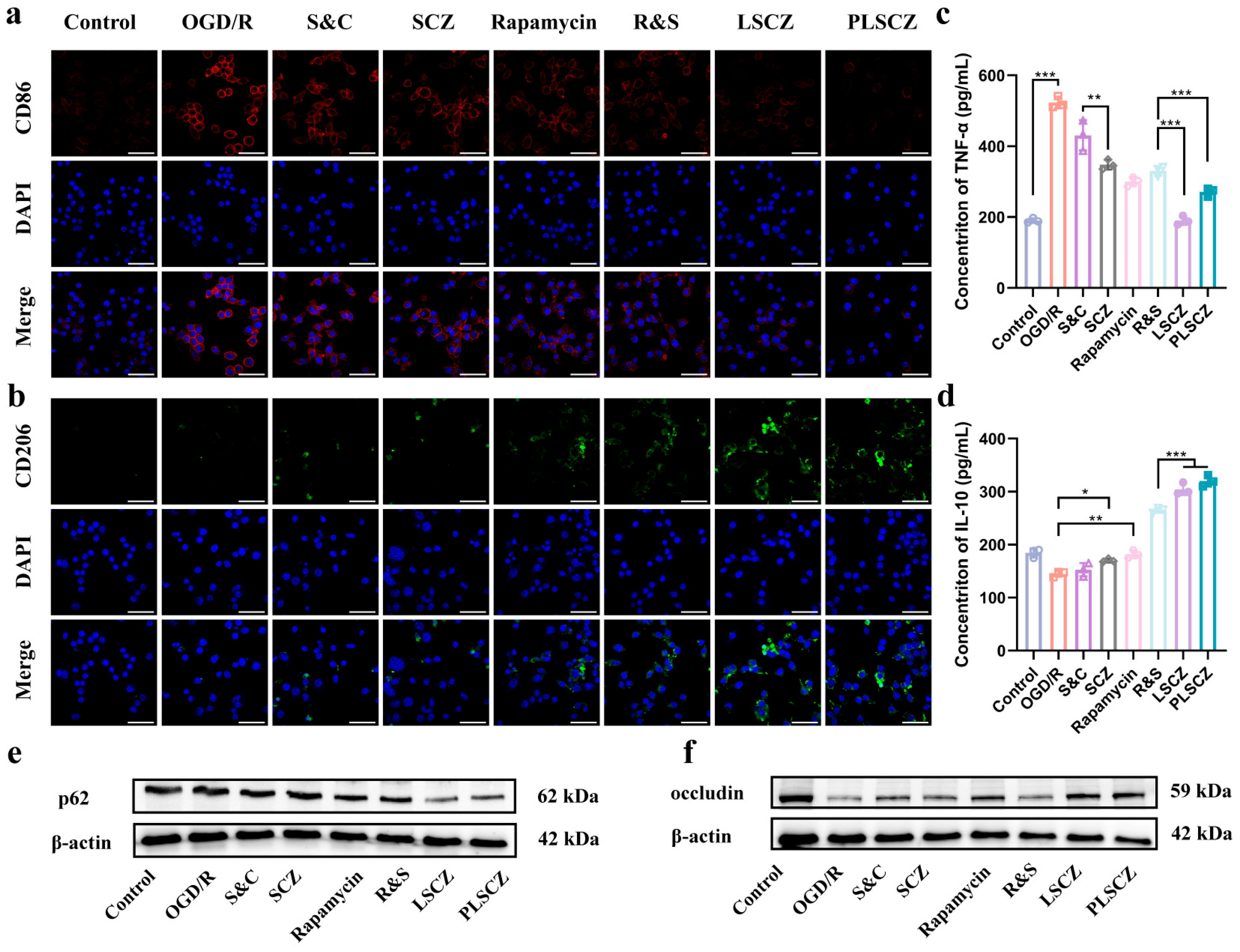

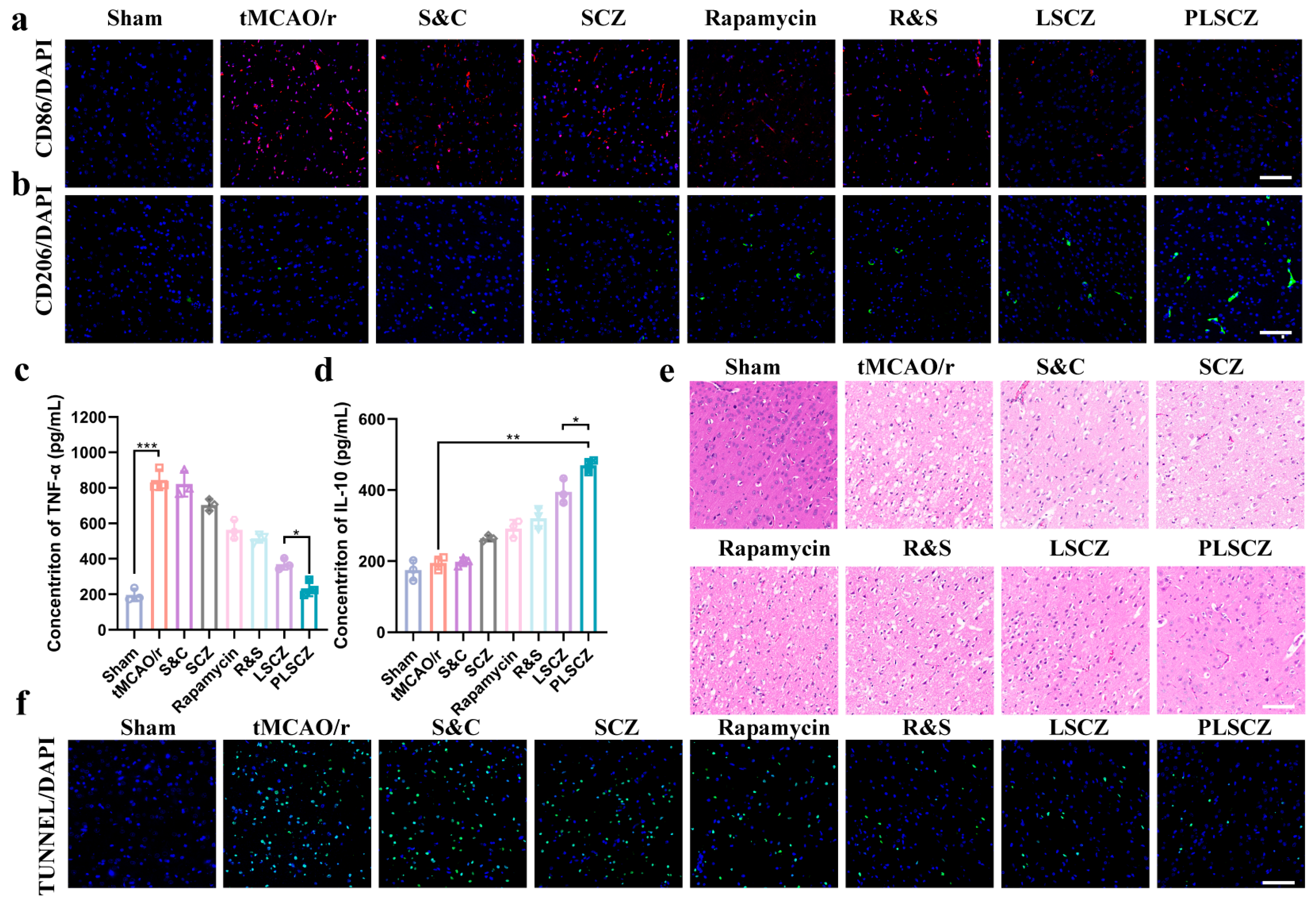

3.5. Microglial Polarization and Anti-Inflammation In Vitro

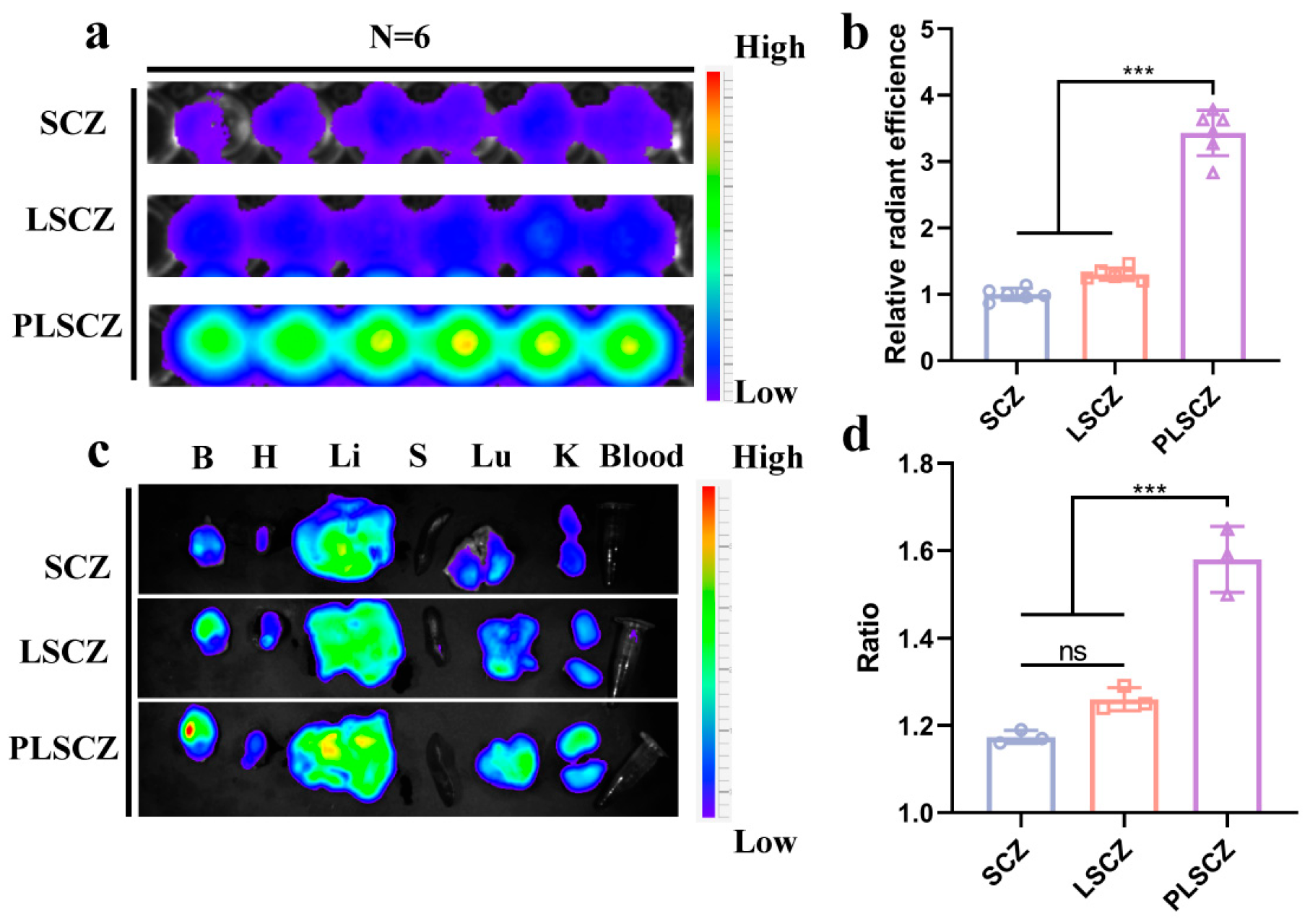

3.6. Brain Occlusions Targeting Ability and Endothelial Repair of PLSCZ

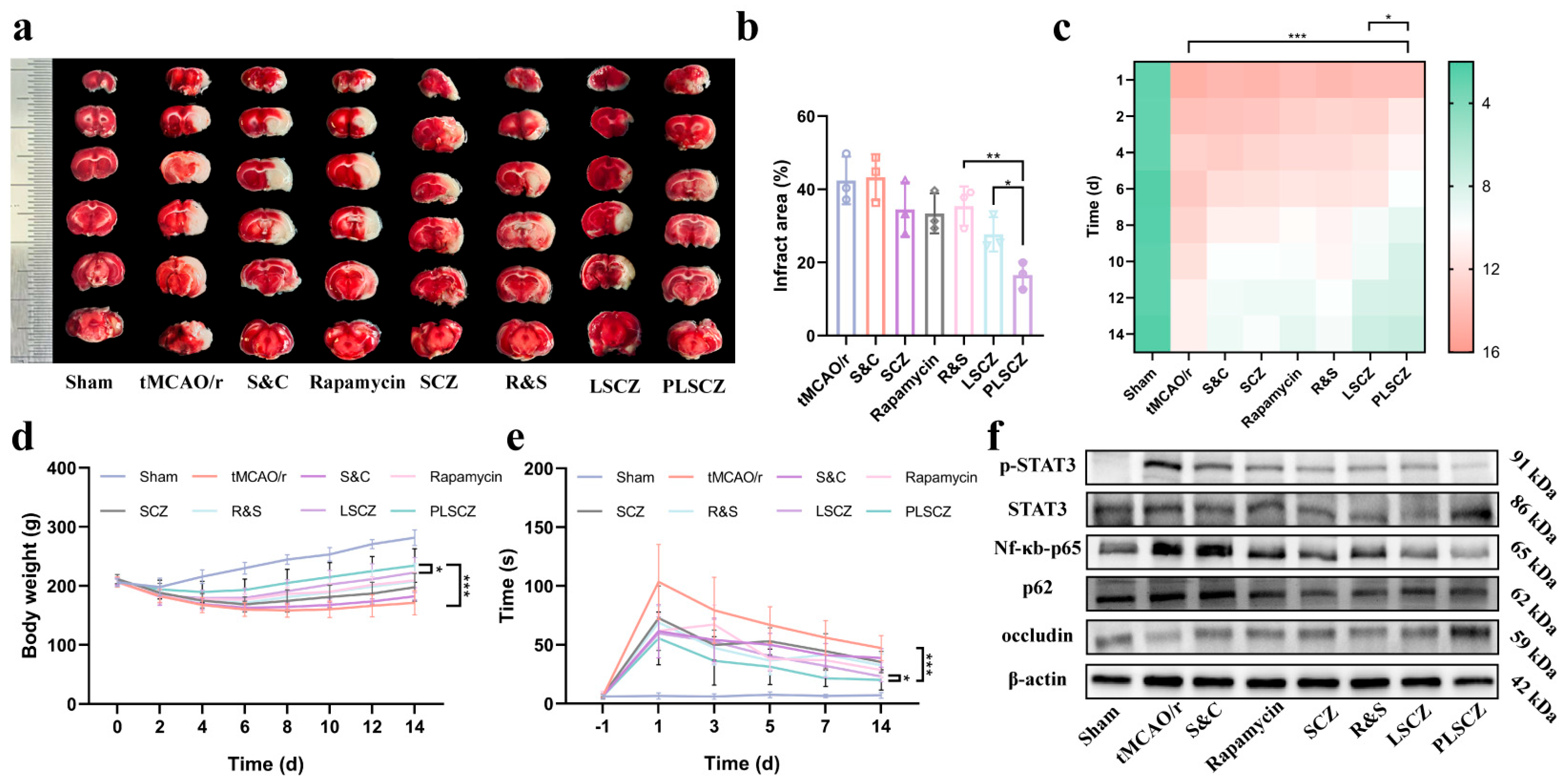

3.7. Evaluation of Neuroprotective Effect

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gardener, H.; Wright, C.B.; Rundek, T.; Sacco, R.L. Brain Health and Shared Risk Factors for Dementia and Stroke. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 11, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2019 Stroke Collaborators. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Stroke and Its Risk Factors, 1990-2019: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 795–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Chu, R.; Wang, Y. Neuroprotective Treatments for Ischemic Stroke: Opportunities for Nanotechnology. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2209405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, Y.; Kim, S.; Chung, H.-T.; Pae, H.-O. Reactive Oxygen Species in the Activation of MAP Kinases. Methods Enzymol. 2013, 528, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, L.; Ye, X.; Hao, Q.; Zhang, T.; Cui, G.; Yu, M. Nrf2/ARE Pathway Inhibits ROS-Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in BV2 Cells after Cerebral Ischemia Reperfusion. Inflamm. Res. 2018, 67, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Huang, L.; Cheng, C.; Li, G.; Xie, J.; Shen, M.; Chen, Q.; Li, W.; He, W.; Qiu, P.; et al. Design, Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Chalcone Analogues with Novel Dual Antioxidant Mechanisms as Potential Anti-Ischemic Stroke Agents. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2019, 9, 335–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Liang, X.; Shan, J.; Gu, W.; Qiu, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, G. Functionalized Nanoparticles with Monocyte Membranes and Rapamycin Achieve Synergistic Chemoimmunotherapy for Reperfusion-Induced Injury in Ischemic Stroke. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2021, 19, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Xiong, X.; Wu, X.; Ye, Y.; Jian, Z.; Zhi, Z.; Gu, L. Targeting Oxidative Stress and Inflammation to Prevent Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valko, M.; Leibfritz, D.; Moncol, J.; Cronin, M.T.D.; Mazur, M.; Telser, J. Free Radicals and Antioxidants in Normal Physiological Functions and Human Disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2007, 39, 44–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, R453–R462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziveleka, L.-A.; Tammam, M.A.; Tzakou, O.; Roussis, V.; Ioannou, E. Metabolites with Antioxidant Activity from Marine Macroalgae. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.; Brenner, J.S. Developing Targeted Antioxidant Nanomedicines for Ischemic Penumbra: Novel Strategies in Treating Brain Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Redox Biol. 2024, 73, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubota, R.; Asayama, S.; Kawakami, H. Catalytic Antioxidants for Therapeutic Medicine. J. Mater. Chem. B 2019, 7, 3165–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Talalay, P. Direct and Indirect Antioxidant Properties of Inducers of Cytoprotective Proteins. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, S128–S138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghorbani, M.; Izadi, Z.; Jafari, S.; Casals, E.; Rezaei, F.; Aliabadi, A.; Moore, A.; Ansari, A.; Puntes, V.; Jaymand, M.; et al. Preclinical Studies Conducted on Nanozyme Antioxidants: Shortcomings and Challenges Based on US FDA Regulations. Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 1133–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Review. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 1893–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorecki, M.; Beck, Y.; Hartman, J.R.; Fischer, M.; Weiss, L.; Tochner, Z.; Slavin, S.; Nimrod, A. Recombinant Human Superoxide Dismutases: Production and Potential Therapeutical Uses. Free Radic. Res. Commun. 1991, 12, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, M.; Han, G.; Wan, J.; Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Zong, W.; Niu, Q.; Liu, R. Catalase and Superoxide Dismutase Response and the Underlying Molecular Mechanism for Naphthalene. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 736, 139567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Brynskikh, A.M.; S-Manickam, D.; Kabanov, A.V. SOD1 Nanozyme Salvages Ischemic Brain by Locally Protecting Cerebral Vasculature. J. Control Release 2015, 213, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Hussain, N.; Américo-Pinheiro, J.H.P.; Almulaiky, Y.Q.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Multi-Enzyme Co-Immobilized Nano-Assemblies: Bringing Enzymes Together for Expanding Bio-Catalysis Scope to Meet Biotechnological Challenges. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 186, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Hussain, N.; Américo-Pinheiro, J.H.P.; Almulaiky, Y.Q.; Iqbal, H.M. Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIF-8) for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021, 28, 7023–7075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Deng, Z.; Cao, G.; Chu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Peng, X.; Han, G. Co–Ferrocene MOF/Glucose Oxidase as Cascade Nanozyme for Effective Tumor Therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1910085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, C.; Du, X.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Biomimetic Engineering of a Neuroinflammation-Targeted MOF Nanozyme Scaffolded with Photo-Trigger Released CO for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Chem. Sci. 2024, 15, 13201–13208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, F.; Lin, C.; Lu, J.; Sun, D. Integrating Artificial DNAzymes with Natural Enzymes on 2D MOF Hybrid Nanozymes for Enhanced Treatment of Bacteria-Infected Wounds. Small 2023, 20, 2307256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Kou, X.; Shen, J.; Chen, G.; Ouyang, G. “Armor-Plating” Enzymes with Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 8786–8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, W.; Flint, K.; Yao, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, L.; Doonan, C.; Huang, J. Enhanced Bioactivity of Enzyme/MOF Biocomposite via Host Framework Engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 20365–20374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markopoulou, P.; Forgan, R.S. Chapter 12—Postsynthetic Modification of MOFs for Biomedical Applications. In Metal-Organic Frameworks for Biomedical Applications; Mozafari, M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2020; pp. 245–276. ISBN 978-0-12-816984-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Yuan, H.; Hu, F. Cell Membrane Coated-Nanoparticles for Cancer Immunotherapy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3233–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibbitt, M.W.; Dahlman, J.E.; Langer, R. Emerging Frontiers in Drug Delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-M.J.; Fang, R.H.; Wang, K.-C.; Luk, B.T.; Thamphiwatana, S.; Dehaini, D.; Nguyen, P.; Angsantikul, P.; Wen, C.H.; Kroll, A.V.; et al. Nanoparticle Biointerfacing by Platelet Membrane Cloaking. Nature 2015, 526, 118–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.A.; Chen, J.; Whitelock, J.L.; Morales, L.D.; López, J.A. The Platelet Glycoprotein Ib–von Willebrand Factor Interaction Activates the Collagen Receptor A2β1 to Bind Collagen: Activation-Dependent Conformational Change of the A2-I Domain. Blood 2005, 105, 1986–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, Z.; Hu, C.; Maitz, M.F.; Yang, L.; Luo, R.; Wang, Y. Platelet Membrane-Coated Nanocarriers Targeting Plaques to Deliver Anti-CD47 Antibody for Atherosclerotic Therapy. Research 2022, 2022, 9845459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.-C.; Luo, T.; Feng, B.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, H.; Yang, X.; Wen, J.; Bai, X.; Cui, Z.-K. Exploring the Translational Potential of PLGA Nanoparticles for Intra-Articular Rapamycin Delivery in Osteoarthritis Therapy. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, Z.-L.; Deng, Y.-J.; DU, H.-Y.; Suo, X.-B.; Wang, X.-Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Cui, L.-J.; Duan, N. Preparation of a Liposomal Delivery System and Its in Vitro Release of Rapamycin. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 9, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groth, C.G.; Bäckman, L.; Morales, J.-M.; Calne, R.; Kreis, H.; Lang, P.; Touraine, J.-L.; Claesson, K.; Campistol, J.M.; Durand, D.; et al. Sirolimus (Rapamycin)-Based Therapy In Human Renal Transplantation. Transplantation 1999, 67, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, C.; Chen, Q.; Liu, P.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Liang, D.; et al. Microthrombus-Targeting Micelles for Neurovascular Remodeling and Enhanced Microcirculatory Perfusion in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1808361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longa, E.Z.; Weinstein, P.R.; Carlson, S.; Cummins, R. Reversible Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion without Craniectomy in Rats. Stroke 1989, 20, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, J. A Rapid and Simple MTT-Based Spectrophotometric Assay for Determining Drug Sensitivity in Monolayer Cultures. J. Tissue Cult. Methods 1988, 11, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqui, A.; Chance, B. Enhanced Superoxide Dismutase Activity of Pulsed Cytochrome Oxidase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1986, 136, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afri, M.; Frimer, A.A.; Cohen, Y. Active Oxygen Chemistry within the Liposomal Bilayer. Part IV: Locating 2′,7′-Dichlorofluorescein (DCF), 2′,7′-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein (DCFH) and 2’,7’-Dichlorodihydrofluorescein Diacetate (DCFH-DA) in the Lipid Bilayer. Chem. Phys. Lipids 2004, 131, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Mei, S.; Jin, H.; Zhu, B.; Tian, Y.; Huo, J.; Cui, X.; Guo, A.; Zhao, Z. Identification of Two Immortalized Cell Lines, ECV304 and bEnd3, for in Vitro Permeability Studies of Blood-Brain Barrier. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0187017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldlust, E.J.; Paczynski, R.P.; He, Y.Y.; Hsu, C.Y.; Goldberg, M.P. Automated Measurement of Infarct Size with Scanned Images of Triphenyltetrazolium Chloride-Stained Rat Brains. Stroke 1996, 27, 1657–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, D.; Lu, M.; Chopp, M. Therapeutic Benefit of Intravenous Administration of Bone Marrow Stromal Cells after Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. Stroke 2001, 32, 1005–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Chopp, M. Quantitative Measurement of Motor and Somatosensory Impairments after Mild (30 Min) and Severe (2 h) Transient Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion in Rats. J. Neurol. Sci. 2000, 174, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candelario-Jalil, E.; Mhadu, N.H.; Al-Dalain, S.M.; Martínez, G.; León, O.S. Time Course of Oxidative Damage in Different Brain Regions Following Transient Cerebral Ischemia in Gerbils. Neurosci. Res. 2001, 41, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinouchi, H.; Epstein, C.J.; Mizui, T.; Carlson, E.; Chen, S.F.; Chan, P.H. Attenuation of Focal Cerebral Ischemic Injury in Transgenic Mice Overexpressing CuZn Superoxide Dismutase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 11158–11162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, J.H.; Giffard, R.G. Overexpression of Copper/Zinc Superoxide Dismutase Decreases Ischemia-like Astrocyte Injury. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2005, 38, 1112–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; He, M.; Chen, B.; Hu, B. Size- and Dose-Dependent Cytotoxicity of ZIF-8 Based on Single Cell Analysis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 205, 111110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamames-Tabar, C.; Cunha, D.; Imbuluzqueta, E.; Ragon, F.; Serre, C.; Blanco-Prieto, M.J.; Horcajada, P. Cytotoxicity of Nanoscaled Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 2, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearier, E.; Cheng, P.; Zhu, Z.; Bao, J.; Hu, Y.H.; Zhao, F. Surface Defection Reduces Cytotoxicity of Zn(2-Methylimidazole)2 (ZIF-8) without Compromising Its Drug Delivery Capacity. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 4128–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, Á.; Dirnagl, U.; Urra, X.; Planas, A.M. Neuroprotection in Acute Stroke: Targeting Excitotoxicity, Oxidative and Nitrosative Stress, and Inflammation. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 869–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresolí-Obach, R.; Busto-Moner, L.; Muller, C.; Reina, M.; Nonell, S. NanoDCFH-DA: A Silica-Based Nanostructured Fluorogenic Probe for the Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species. Photochem. Photobiol. 2018, 94, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.-Y.; Li, Y.-N.; Qi, J.-S.; Niu, T. Peroxynitrite-Induced Protein Nitration Contributes to Liver Mitochondrial Damage in Diabetic Rats. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2008, 22, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, C.; Clark, H.B.; Ross, M.E.; Iadecola, C. Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Expression in Human Cerebral Infarcts. Acta Neuropathol. 1999, 97, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birben, E.; Sahiner, U.M.; Sackesen, C.; Erzurum, S.; Kalayci, O. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Defense. World Allergy Organ. J. 2012, 5, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couto, N.; Wood, J.; Barber, J. The Role of Glutathione Reductase and Related Enzymes on Cellular Redox Homoeostasis Network. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016, 95, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirrlinger, J.; Dringen, R. Multidrug Resistance Protein 1-Mediated Export of Glutathione and Glutathione Disulfide from Brain Astrocytes. Methods Enzymol. 2005, 400, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Homolya, L.; Váradi, A.; Sarkadi, B. Multidrug Resistance-Associated Proteins: Export Pumps for Conjugates with Glutathione, Glucuronate or Sulfate. Biofactors 2003, 17, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angabo, S.; Pandi, K.; David, K.; Steinmetz, O.; Makkawi, H.; Farhat, M.; Eli-Berchoer, L.; Darawshi, N.; Kawasaki, H.; Nussbaum, G. CD47 and Thrombospondin-1 Contribute to Immune Evasion by Porphyromonas Gingivalis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2405534121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, T.H.; Reynolds, C.A.; Kumar, R.; Przyklenk, K.; Hüttemann, M. Molecular Mechanisms of Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Brain: Pivotal Role of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Reactive Oxygen Species Generation. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012, 47, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panickar, K.S.; Anderson, R.A. Effect of Polyphenols on Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neuronal Death and Brain Edema in Cerebral Ischemia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 8181–8207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, S.; Raj, Y.; Krishnamurthy, R. CypD: The Key to the Death Door. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2015, 14, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flippo, K.H.; Lin, Z.; Dickey, A.S.; Zhou, X.; Dhanesha, N.A.; Walters, G.C.; Liu, Y.; Merrill, R.A.; Meller, R.; Simon, R.P.; et al. Deletion of a Neuronal Drp1 Activator Protects against Cerebral Ischemia. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 3119–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Xiao, L.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Q. Regulation of Microglia Polarization after Cerebral Ischemia. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1182621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yang, G.-Y. The Biphasic Function of Microglia in Ischemic Stroke. Prog. Neurobiol. 2017, 157, 247–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, U.; Rajasingh, S.; Samanta, S.; Cao, T.; Dawn, B.; Rajasingh, J. Macrophage Polarization in Response to Epigenetic Modifiers during Infection and Inflammation. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sica, A.; Erreni, M.; Allavena, P.; Porta, C. Macrophage Polarization in Pathology. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 4111–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.-S.; Qin, Q.-L.; Huang, C.; Li, Z.-R.; Wang, Z.-H.; Wang, Y.-Y.; He, X.-Y.; Zhao, X.-M. The Pathological Mechanism of Neuronal Autophagy-Lysosome Dysfunction After Ischemic Stroke. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 3251–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, K.M.; Hess, D.L.; Sazonova, I.Y.; Periyasamy-Thandavan, S.; Barrett, J.R.; Kirks, R.; Grace, H.; Kondrikova, G.; Johnson, M.H.; Hess, D.C.; et al. Rapamycin Up-Regulation of Autophagy Reduces Infarct Size and Improves Outcomes in Both Permanent MCAL, and Embolic MCAO, Murine Models of Stroke. Exp. Trans. Stroke Med. 2014, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiese, K. Cutting through the Complexities of mTOR for the Treatment of Stroke. Curr. Neurovascular Res. 2014, 11, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugsley, H.R. Assessing Autophagic Flux by Measuring LC3, P62, and LAMP1 Co-Localization Using Multispectral Imaging Flow Cytometry. J. Vis. Exp. 2017, 125, 55637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, D.; Hu, J.; Lin, J.; Man, W.; et al. Polydatin Protects Cardiomyocytes against Myocardial Infarction Injury by Activating Sirt3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 1962–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Fonseca, A.C.C.; Matias, D.; Garcia, C.; Amaral, R.; Geraldo, L.H.; Freitas, C.; Lima, F.R.S. The Impact of Microglial Activation on Blood-Brain Barrier in Brain Diseases. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satriotomo, I.; Bowen, K.K.; Vemuganti, R. JAK2 and STAT3 Activation Contributes to Neuronal Damage Following Transient Focal Cerebral Ischemia. J. Neurochem. 2006, 98, 1353–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Li, J.; Fu, M.; Zhao, X.; Wang, W. The JAK/STAT Signaling Pathway: From Bench to Clinic. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.-F.; Xu, R.-X.; Wei, J.-P.; Jiang, X.-D.; Liu, Z.-H. P-JAK2 and P-STAT3 Protein Expression and Cell Apoptosis Following Focal Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Rats. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao = J. South. Med. Univ. 2007, 27, 208–211, 218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Lu, H.; Guo, C.; Fang, W.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Berberine Attenuates Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury through Inhibiting HMGB1 Release and NF-κB Nuclear Translocation. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2018, 39, 1706–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.J.; Yun, H.-M.; Jung, Y.Y.; Lee, D.H.; Yoon, N.Y.; Seo, H.O.; Han, J.-Y.; Oh, K.-W.; Choi, D.Y.; Han, S.-B.; et al. Reducing Effect of IL-32α in the Development of Stroke through Blocking of NF-κB, but Enhancement of STAT3 Pathways. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 51, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.J. Astrocyte Heterogeneity in the Adult Central Nervous System. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.-S.; Peterson, T.C.; et al. Neurotoxic Reactive Astrocytes Are Induced by Activated Microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhang, D.-M.; Feng, X.; Wang, J.; Qin, Y.-Y.; Zhang, T.; Huang, Q.; Sheng, R.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; et al. TIGAR Inhibits Ischemia/Reperfusion-Induced Inflammatory Response of Astrocytes. Neuropharmacology 2018, 131, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, C.; Palomo, J.M.; Fernandez-Lorente, G.; Guisan, J.M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. Improvement of Enzyme Activity, Stability and Selectivity via Immobilization Techniques. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2007, 40, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennick, J.J.; Johnston, A.P.R.; Parton, R.G. Key Principles and Methods for Studying the Endocytosis of Biological and Nanoparticle Therapeutics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2021, 16, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, A.J.; Liu, Y.; Li, P.; Li, Z.; Wang, T.C.; Hupp, J.; Farha, O.K. Chemical, Thermal and Mechanical Stabilities of Metal-Organic Frameworks. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.U.; Park, J.-Y.; Kwon, S.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Khang, D.; Hong, J.H. Apoptotic Lysosomal Proton Sponge Effect in Tumor Tissue by Cationic Gold Nanorods. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 19980–19993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-L.; Mukda, S.; Chen, S.-D. Diverse Roles of Mitochondria in Ischemic Stroke. Redox Biol. 2018, 16, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, R.C.; Sexton, T.; Smyth, S.S. Translational Implications of Platelets as Vascular First Responders. Circ. Res. 2018, 122, 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Wang, C.; Liu, Z. Red Blood Cells as Smart Delivery Systems. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 852–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, R.J.C.; Lee, S.-H.; Park, H. Biofunctionalized Nanoparticles: An Emerging Drug Delivery Platform for Various Disease Treatments. Drug Discov. Today 2016, 21, 1303–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Chen, C.; Miao, X.; Wang, T.; Guan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Kang, J.; et al. Injury Site Specific Xenon Delivered by Platelet Membrane-Mimicking Hybrid Microbubbles to Protect Against Acute Kidney Injury via Inhibition of Cellular Senescence. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2203359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y.; Ai, K.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, T.; Zeng, C.; Lei, G. Engineered Platelet Microparticle-Membrane Camouflaged Nanoparticles for Targeting the Golgi Apparatus of Synovial Fibroblasts to Attenuate Rheumatoid Arthritis. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 18430–18447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, K.; Vaz, W.L.C. Model Systems, Lipid Rafts, and Cell Membranes. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2004, 33, 269–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milford, E.M.; Reade, M.C. Comprehensive Review of Platelet Storage Methods for Use in the Treatment of Active Hemorrhage. Transfusion 2016, 56 (Suppl. S2), S140–S148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, G.M.; Cliff, R.; Tandon, N. Thrombosomes: A Platelet-Derived Hemostatic Agent for Control of Noncompressible Hemorrhage. Transfusion 2013, 53 (Suppl. S1), 100S–106S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slichter, S.J.; Jones, M.; Ransom, J.; Gettinger, I.; Jones, M.K.; Christoffel, T.; Pellham, E.; Bailey, S.L.; Corson, J.; Bolgiano, D. Review of in Vivo Studies of Dimethyl Sulfoxide Cryopreserved Platelets. Transfus. Med. Rev. 2014, 28, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidcoke, H.F.; McFaul, S.J.; Ramasubramanian, A.K.; Parida, B.K.; Mora, A.G.; Fedyk, C.G.; Valdez-Delgado, K.K.; Montgomery, R.K.; Reddoch, K.M.; Rodriguez, A.C.; et al. Primary Hemostatic Capacity of Whole Blood: A Comprehensive Analysis of Pathogen Reduction and Refrigeration Effects over Time. Transfusion 2013, 53 (Suppl. S1), 137S–149S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Shi, T.; Li, J.; Chen, W.; Wei, Q.; Pan, H.; Xu, S.; et al. MOF-Engineered Platelet-Mimicking Nanocarrier-Encapsulated Cascade Enzymes for ROS Scavenging and Anti-Inflammation in Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111478

Li H, Xie X, Zhang Y, Han X, Shi T, Li J, Chen W, Wei Q, Pan H, Xu S, et al. MOF-Engineered Platelet-Mimicking Nanocarrier-Encapsulated Cascade Enzymes for ROS Scavenging and Anti-Inflammation in Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(11):1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111478

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hao, Xiaowei Xie, Yu Zhang, Xiaopeng Han, Ting Shi, Jiayin Li, Wanyu Chen, Qin Wei, Hong Pan, Shuxian Xu, and et al. 2025. "MOF-Engineered Platelet-Mimicking Nanocarrier-Encapsulated Cascade Enzymes for ROS Scavenging and Anti-Inflammation in Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 11: 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111478

APA StyleLi, H., Xie, X., Zhang, Y., Han, X., Shi, T., Li, J., Chen, W., Wei, Q., Pan, H., Xu, S., Chen, Q., Yin, L., & Qin, C. (2025). MOF-Engineered Platelet-Mimicking Nanocarrier-Encapsulated Cascade Enzymes for ROS Scavenging and Anti-Inflammation in Cerebral Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury. Pharmaceutics, 17(11), 1478. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111478