A Meta-Analysis of In Vitro Release of Hydrophilic Therapeutics from Contact Lenses Using Mathematical Modeling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Data

2.1.1. Cumulative Therapeutic Release Experiment

2.1.2. Estimated Partition Coefficient

2.1.3. Lens and Therapeutic Properties

2.2. Mathematical Model

2.3. Parameter Estimation Algorithm

- Inputs: The inputs to the parameter estimate algorithm were

- (i)

- An experimental time-series dataset of the cumulative release of the therapeutic from a contact lens placed in a vial of fluid, i.e., , , ;

- (ii)

- The initial amount of therapeutic loaded into the contact lens, i.e., ;

- (iii)

- The radius (R) and the thickness (), of the contact lens (see Figure 1—1. Input).

- When total lens therapeutic absorption was provided, as reported by Torres-Luna et al. [13], the reported value was used to compute the initial condition (); otherwise, was approximated using the average of the last three time points of the therapeutic cumulative release data, i.e.,

- Step 1. An approximation of the diffusion coefficient (D), denoted by , was found by fitting the experimental data to an exponential functional approximating Equation (5). More specifically, the time-series cumulative release data was fitted to an exponential function given bywhich was found by taking the first three terms of the series in Equation (4) and plugging them into Equation (5). The lsqnonlin nonlinear least squares solver in MATLAB 2022b (Natick, MA, USA) was used to find values of , , and that minimized the sum of the squares of the residuals given by

- The approximation of the diffusion coefficient () was found by setting

- Step 2. An estimate () was found by minimizing a different nonlinear least squares error given bywhere was approximated using the numerical solution of the partial differential equation problem in Equation (3) and evaluating the integral of Equation (5). To find the numerical solution of Equation (3), the method of lines was used. The spatial partial derivatives were approximated by second-order centered finite differences (, where ) and the temporal partial derivative by a forward finite difference (). The integral in Equation (5) was approximated using the trapezoidal rule.

- Outputs. Given the variability of the data, for each lens–therapeutic combination, a range of diffusion coefficients was estimated and a region (range) of cumulative therapeutic release was predicted. For each dataset, the algorithm was performed to fit the average data of cumulative release and obtain the average value of , denoted as . The average data plus or minus their standard deviations were fitted to obtain the upper and lower bounds for .

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Validation of the Model and Algorithm

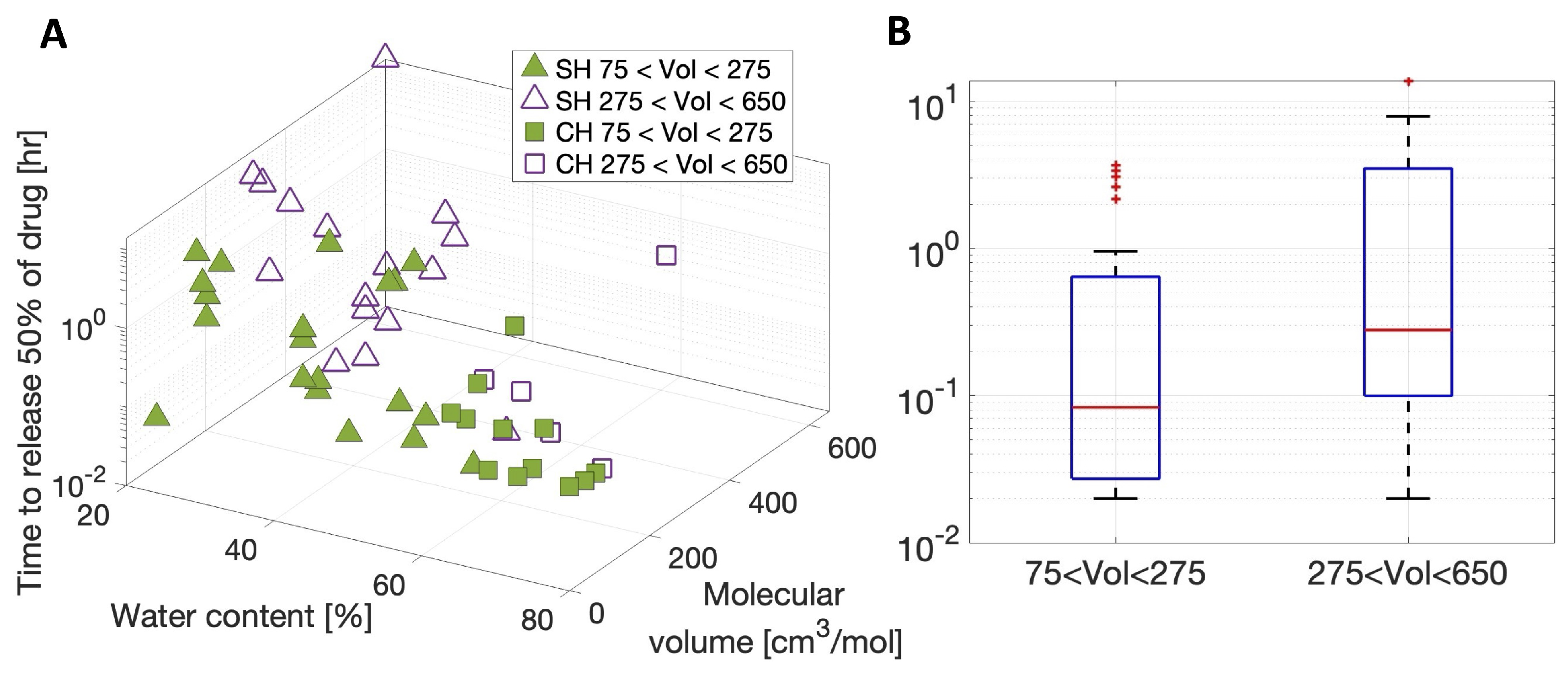

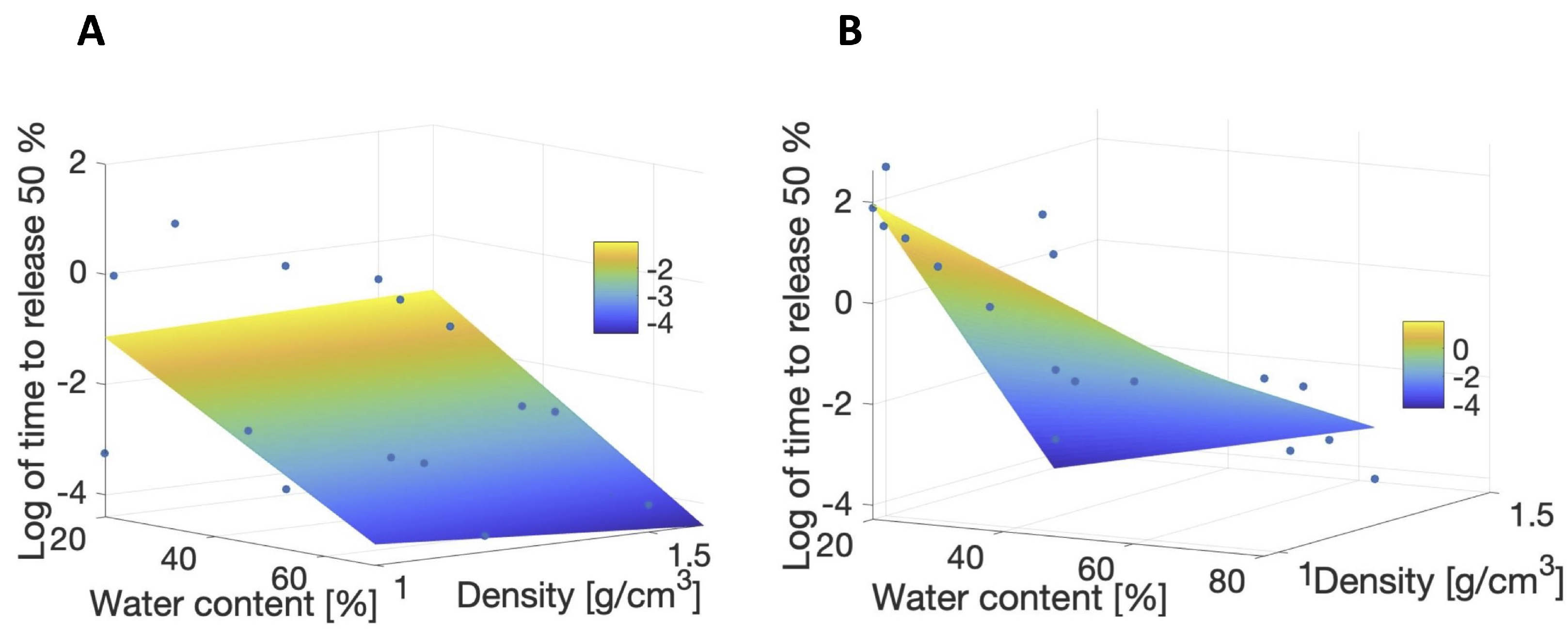

3.2. Meta-Analysis of Estimated Diffusion Coefficients

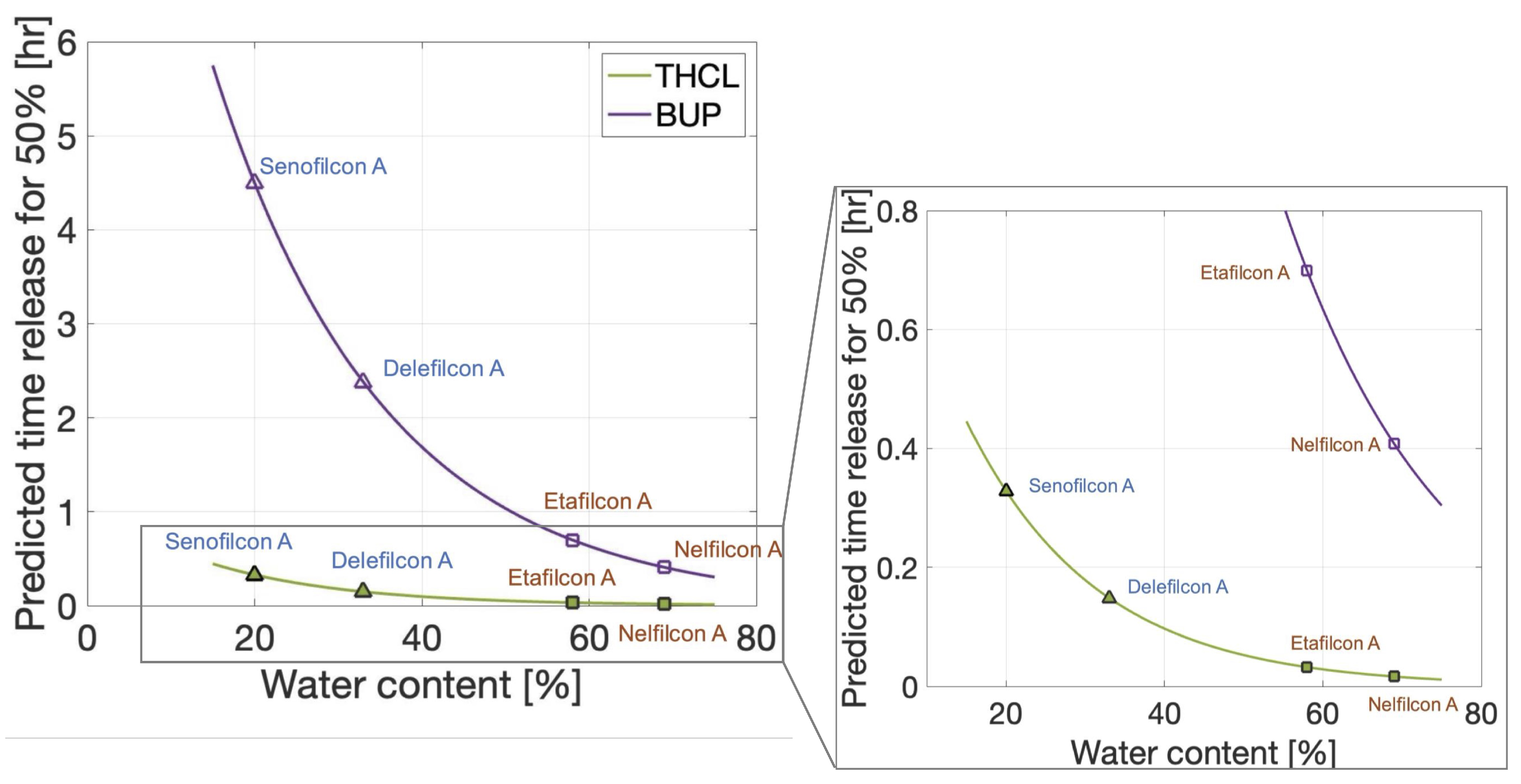

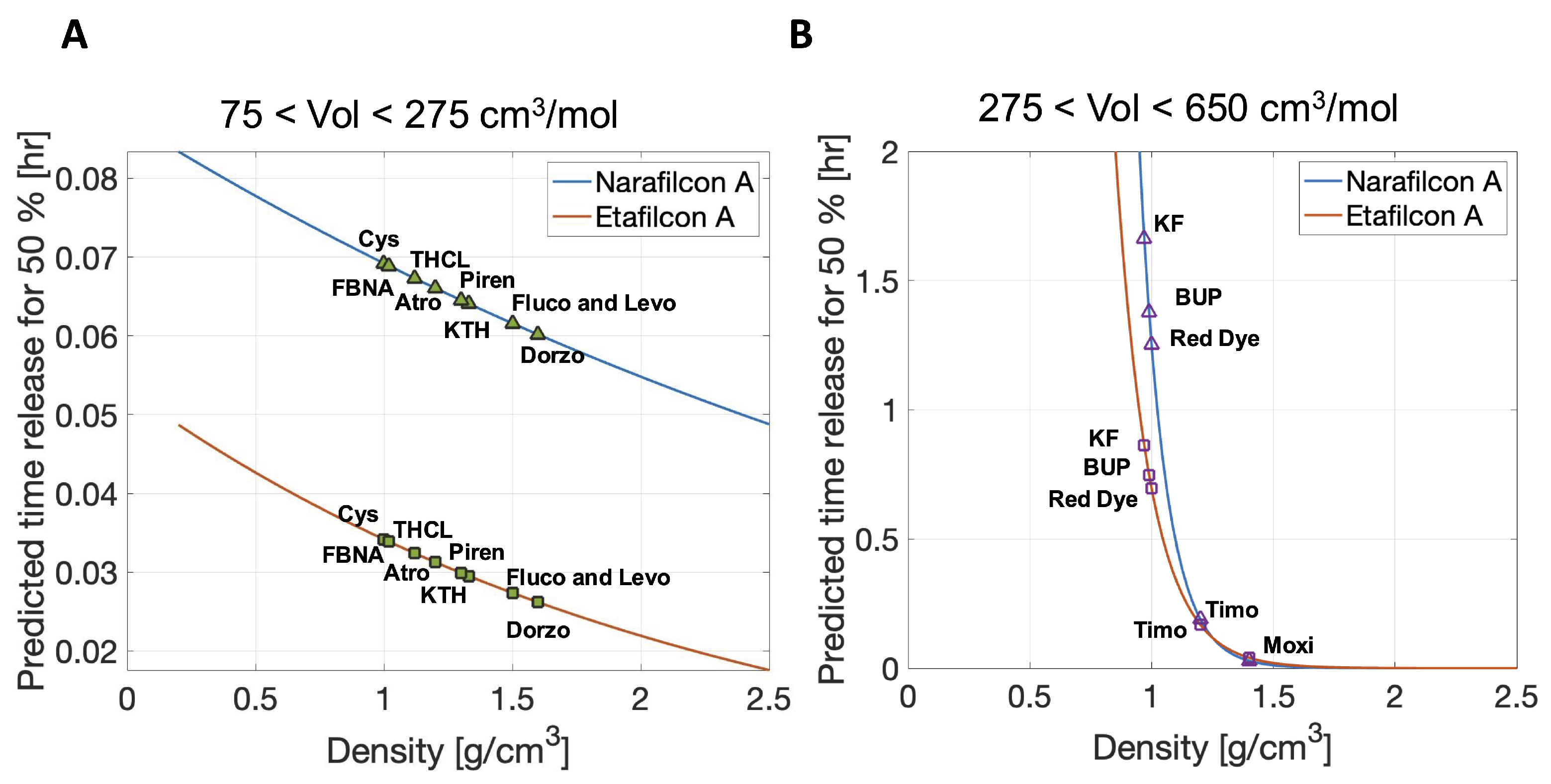

3.3. Predictions of Therapeutic Release Times

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CH | Commercial hydrogel |

| SH | Silicone hydrogel |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| EGDMA | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| FMA | N-Formylmethyl acrylamide |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| NVP | N-vinylpyrrolidone |

| DMA | N,N-Dimethylacrylamide |

| PC | Phosphorylcholine |

| MPDMS | Monofunctional polydimethylsiloxane |

| TEGDMA | Tetraethleneglycol dimethacrylate |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| HEMA | Hydroxyethyl methacrylate |

| MAA | Methacrylic acid |

| TRIS | 3-(trimethylsiloxy)silylpropyl methacrylate |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| FMA | Fluorinated methacrylate |

| MA-PDMS-MA | Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) long chains with methacrylate (MA) at both ends. |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| Cys | Cysteamine |

| THCL | Tetracaine hydrochloride |

| FBNA | Flurbiprofen sodium |

| KTH | Ketorolac tromethamine |

| Atro | Atropine |

| Fluco | Fluconazole |

| KF | Ketotifen fumarate |

| Dorzo | Dorzolamide |

| BUP | Bupivacaine |

| Piren | Pirenzepine |

| Levo | Levofloxacin |

| Moxi | Moxifloxacin |

| Timo | Timolol |

| RD | Red dye |

Appendix A. Justification of Sink Boundary Conditions

Appendix B. Partition Coefficient Estimates

| Therapeutic | Lens | Loading Conc [mg/mL] | Vial Volume [mL] | Lens vol [mL] | Partition Coeff K | [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atropine | Delefilcon A [12] | 10.00 | 4.0 | 0.014 | 0.0019 | 0.35 |

| Narafilcon A [12] | 10.000 | 4.0 | 0.014 | 0.0021 | 0.36 | |

| Ocufilcon B [12] | 10.000 | 4.0 | 0.013 | 0.0076 | 0.32 | |

| Etafilcon A [12] | 10.000 | 4.0 | 0.013 | 0.0080 | 0.32 | |

| Omafilcon A [12] | 10.000 | 4.0 | 0.014 | 0.0052 | 0.36 | |

| Nelfilcon A [12] | 10.000 | 4.0 | 0.015 | 0.0020 | 0.38 | |

| Bupivacaine | Senofilcon A [13] | 1.000 | 10.0 | 0.013 | 13.0376 | 0.13 |

| Narafilcon A [13] | 1.000 | 10.0 | 0.014 | 19.5144 | 0.14 | |

| Cysteamine | Senofilcon A [29] | 50.000 | 3.0 | 0.013 | 0.9192 | 0.45 |

| Narafilcon A [29] | 50.000 | 3.0 | 0.014 | 0.9996 | 0.47 | |

| Dorzolamide | Senofilcon A [31] | 0.800 | 3.5 | 0.013 | 12.0636 | 0.39 |

| Fluconazole | Senofilcon A [21] | 0.700 | 2.0 | 0.013 | 6.9860 | 0.67 |

| Lotrafilcon A [21] | 0.700 | 2.0 | 0.012 | 6.9830 | 0.60 | |

| Lotrafilcon B [21] | 0.700 | 2.0 | 0.012 | 8.9742 | 0.60 | |

| Delefilcon A [15] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.014 | 10.5269 | 0.29 | |

| Narafilcon A [15] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.014 | 5.6290 | 0.30 | |

| Somofilcon A [15] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.013 | 6.3846 | 0.28 | |

| Ocufilcon B [15] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.013 | 14.9514 | 0.26 | |

| Etafilcon A [15] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.013 | 12.0924 | 0.27 | |

| Omafilcon A [15] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.014 | 9.0005 | 0.30 | |

| Nelfilcon A [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.015 | 3.0853 | 0.32 | |

| Fluobriprofen | Senofilcon A [32] | 0.200 | 3.0 | 0.013 | 49.1691 | 0.45 |

| sodium | Narafilcon A [32] | 0.200 | 3.0 | 0.014 | 45.5571 | 0.47 |

| Ketotifen | Senofilcon A [12] | 0.300 | 10.0 | 0.013 | 44.1014 | 0.13 |

| fumarate | SCL3 [11] | 1.945 | 5.0 | 0.009 | 18.6872 | 0.18 |

| SCL2 [11] | 1.945 | 5.0 | 0.009 | 23.2798 | 0.18 | |

| SCL1 [11] | 1.945 | 5.0 | 0.010 | 27.2340 | 0.19 | |

| Narafilcon A [12] | 0.300 | 10.0 | 0.014 | 44.1298 | 0.14 | |

| Ketorolac | Senofilcon A [12] | 1.200 | 3.0 | 0.013 | 8.2319 | 0.45 |

| tromethamine | Narafilcon A [12] | 1.200 | 3.0 | 0.014 | 7.6045 | 0.48 |

| Levofloxacin | Delefilcon A [11] | 1.500 | 3.0 | 0.014 | 0.8624 | 0.47 |

| Moxifloxacin | Delefilcon A [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.014 | 1.6297 | 0.29 |

| Narafilcon A [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.014 | 2.1655 | 0.30 | |

| Somofilcon A [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.013 | 2.6676 | 0.28 | |

| Ocufilcon B [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.013 | 17.1895 | 0.26 | |

| Etafilcon A [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.013 | 17.5985 | 0.27 | |

| Omafilcon A [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.014 | 9.7811 | 0.30 | |

| Nelfilcon A [14] | 1.000 | 4.8 | 0.015 | 2.5900 | 0.32 | |

| Pirenzepine | Delefilcon A [13] | 1.000 | 4.0 | 0.014 | 0.0142 | 0.35 |

| Narafilcon A [13] | 1.000 | 4.0 | 0.014 | 0.0161 | 0.36 | |

| Ocufilcon B [13] | 1.000 | 4.0 | 0.013 | 0.0253 | 0.32 | |

| Etafilcon A [13] | 1.000 | 4.0 | 0.013 | 0.0265 | 0.32 | |

| Omafilcon A [13] | 1.000 | 4.0 | 0.014 | 0.0372 | 0.36 | |

| Nelfilcon A [13] | 1.000 | 4.0 | 0.015 | 0.0182 | 0.38 | |

| Red dye | Senofilcon A [16] | 1004.800 | 2.0 | 0.013 | 3.7044 | 0.67 |

| Etafilcon A [16] | 1004.800 | 2.0 | 0.013 | 1.6533 | 0.64 | |

| Tetracaine | Senofilcon A [12] | 0.200 | 10.0 | 0.013 | 41.4192 | 0.13 |

| hydrochloride | Narafilcon A [12] | 0.200 | 10.0 | 0.014 | 35.6946 | 0.14 |

| Timolol | Senofilcon A [21] | 0.800 | 2.0 | 0.013 | 8.8011 | 0.67 |

| Lotrafilcon A [21] | 0.800 | 2.0 | 0.012 | 4.7859 | 0.60 | |

| Lotrafilcon B [21] | 0.800 | 2.0 | 0.012 | 7.4657 | 0.60 | |

| Delefilcon A [18] | 5.000 | 3.0 | 0.014 | 1.7667 | 0.47 | |

| Balafilcon A [21] | 0.800 | 2.0 | 0.011 | 14.8461 | 0.55 |

Appendix C. Additional Results

| Therapeutic | Lens | Initial Loaded Therapeutic Mass [μg] | Estimated Diffusion Coefficient | 50% Release Time T50 [h] | Relative Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atropine | Delefilcon A [12] | mean: 0.27 range: 0.25–0.28 | mean: 16,400 range: 13,990–20,000 | 0.0210 | 1.33 |

| Narafilcon A [12] | mean: 0.36 range: 0.35–0.38 | mean: 6900 range: 6300–7500 | 0.0600 | ||

| Ocufilcon B [12] | mean: 0.96 range: 0.94–0.99 | mean: 4515 range: 4200–4800 | 0.0540 | ||

| Etafilcon A [12] | mean: 1.03 range: 0.10–1.05 | mean: 5808 range: 5400–6200 | 0.0522 | ||

| Omafilcon A [12] | mean: 0.74 range: 0.71–0.77 | mean: 14,680 range: 12,600–17,300 | 0.0202 | ||

| Nelfilcon A [12] | mean: 0.31 range: 0.29–0.33 | mean: 29,750 range: 27,900–31,700 | 0.0201 | ||

| Bupivacaine | Senofilcon A [13] | mean: 175.80 range: 170.33–181.27 | mean: 80 range: 65–92 | 4.3100 | |

| Narafilcon A [13] | mean: 278 range: 232.59–320.96 | mean: 117 range: 67–122 | 3.3800 | ||

| Cysteamine | Senofilcon A [29] | mean: 619.7 range: 569.7–669.7 | mean: 10,200 range: 8300–12,700 | 0.0390 | |

| Narafilcon A [29] | mean: 712.4 range: 684.0–740.8 | mean: 4310 range: 3880–4870 | 0.0923 | ||

| Dorzolamide | Senofilcon A [31] | mean: 122 range: 119.4–124.6 | mean: 1500 range: 1400–1600 | 0.2615 | |

| Fluconazole | Senofilcon A [15] | mean: 65.94 range: 64.48–67.39 | mean: 690 range: 444–762 | 0.5000 | |

| Lotrafilcon A [15] | mean: 58.60 range: 57.29–59.64 | mean: 920 range: 609–1122 | 0.3700 | ||

| Lotrafilcon B [15] | mean: 75.13 range: 73.96–76.28 | mean: 1130 range: 1055–1202 | 0.2700 | ||

| Delefilcon A [15] | mean: 147.86 range: 142.19–153.53 | mean: 1220 range: 1163–1813 | 0.0816 | ||

| Narafilcon A [15] | mean: 80.19 range: 77.99–82.38 | mean: 390 range: 367–606 | 0.0849 | ||

| Somofilcon A [15] | mean: 86.09 range: 81.15–91.03 | mean: 927 range: 357–2071 | 0.0219 | ||

| Ocufilcon B [15] | mean: 189.33 range: 174.40–204.26 | mean: 710 range: 430–936 | 0.0864 | ||

| Etafilcon A [15] | mean: 155.29 range: 125.58–184.99 | mean: 2288 range: 1830–3062 | 0.0212 | ||

| Omafilcon A [15] | mean: 128.22 range: 107.09–149.35 | mean: 5040 range: 4451–5587 | 0.0215 | ||

| Nelfilcon A [15] | mean: 47.47 range: 32.68–62.26 | mean: 4500 range: 4460–5587 | 0.0230 | ||

| Flubriprofen sodium | Senofilcon A [32] | mean: 132.7 range: 126.5–138.9 | mean: 356 range: 337–385 | 0.9582 | |

| Narafilcon A [32] | mean: 129.8 range: 124.6–135 | mean: 107.6 range: 107.1–108 | 3.6800 | ||

| Ketotifen fumarate | Senofilcon A [13] | mean: 178.40 range: 151.56–193.37 | mean: 52 range: 45–61 | 6.6375 | |

| SCL3 [11] | mean: 319.62 range: 301.54–337.36 | mean: 72 range: 70–95 | 3.8600 | ||

| SCL2 [11] | mean: 415.52 range: 387.81–443.23 | mean: 141 range: 108–150 | 2.3400 | ||

| SCL1 [11] | mean: 503.81 range: 470.04–513.00 | mean: 300 range: 250–422 | 1.1500 | ||

| Narafilcon A [13] | mean: 188.60 range: 176.68–200.52 | mean: 50 range: 35–95 | 7.9000 | ||

| Ketrorolac tromethamine | Senofilcon A [32] | mean: 133.2 range: 127.8–138.6 | mean: 436 range: 434–440 | 0.7859 | |

| Narafilcon A [32] | mean: 130 range: 135–140 | mean: 129 range: 126–132 | 3.0800 | ||

| Levofloxacin | Delefilcon A [18] | mean: 4500 range: 4408–4592 | mean: 8900 range: 8700–10,405 | 0.2615 | |

| Moxifloxacin | Delefilcon A [14] | mean: 22.89 range: 20.15–25.64 | mean: 5700 range: 5190–5800 | 0.0703 | |

| Narafilcon A [14] | mean: 30.85 range: 27.54–34.16 | mean: 320 range: 190–330 | 2.0337 | ||

| Somofilcon A [14] | mean: 35.97 range: 34.77–37.18 | mean: 6760 range: 6038–6800 | 0.0315 | ||

| Ocufilcon B [14] | mean: 217.67 range: 214.04–221.31 | mean: 1460 range: 1228–1550 | 0.1200 | ||

| Etafilcon A [14] | mean: 226 range: 223.18–226.50 | mean: 373 range: 300–401 | 0.1100 | ||

| Omafilcon A [14] | mean: 139.34 range: 136.91–141.76 | mean: 5880 range: 5540–5983 | 0.0400 | ||

| Nelfilcon A [14] | mean: 39.85 range: 37.69–42.00 | mean: 43,000 range: 32,555–44,000 | 0.0200 | ||

| Pirenzepine | Delefilcon A [12] | mean: 0.20 range: 0.19–0.21 | mean: 11,600 range: 11,200–13,300 | 0.0315 | |

| Narafilcon A [12] | mean: 0.23 range: 0.22–0.24 | mean: 151 range: 135–251 | 2.6300 | ||

| Ocufilcon B [12] | mean: 0.32 range: 0.29–0.35 | mean: 1890 range: 1800–2100 | 0.1400 | ||

| Etafilcon A [12] | mean: 0.34 range: 0.30–0.38 | mean: 2820 range: 2520–3100 | 0.8400 | ||

| Omafilcon A [12] | mean: 0.53 range: 0.50–0.57 | mean: 10,200 range: 1055–11,500 | 0.0517 | ||

| Nelfilcon A [12] | mean: 0.28 range: 0.26–0.30 | mean: 25,400 range: 22,380–29,300 | 0.0200 | ||

| Red dye | Senofilcon A [16] | mean: 47,800 range: 45,100–50,500 | mean: 25 range: 17–30 | 13.8400 | |

| Etafilcon A [16] | mean: 22,400 range: 20,400–24,400 | mean: 776 range: 607–800 | 0.3100 | ||

| Tetracaine hydrochloride | Senofilcon A [13] | mean: 111.70 range: 105.37–116.08 | mean: 160 range: 110–200 | 2.1633 | |

| Narafilcon A [13] | mean: 101.70 range: 90.91–112.72 | mean: 131 range: 124–149 | 3.0211 | ||

| Timolol | Senofilcon A [21] | mean: 94.94 range: 74.95–114.93 | mean: 1250 range: 1240–1325 | 0.2820 | |

| Lotrafilcon A [21] | mean: 45.79 range: 25.79–65.78 | mean: 1190 range: 1098–1826 | 0.2614 | ||

| Lotrafilcon B [21] | mean: 71.43 range: 51.44–91.42 | mean: 1760 range: 1609–3649 | 0.1764 | ||

| Delefilcon A [18] | mean: 1500 range: 1489.93–1510.70 | mean: 111,000 range: 8900–14,100 | 0.0458 | ||

| Balafilcon A [21] | mean: 131.11 range: 127.51–134.70 | mean: 2700 range: 2227–5316 | 0.1500 |

Appendix D. Outlier Removal Process

| 75 < Vol < 275 [cm3/mol] | 275 < Vol < 650 [cm3/mol] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Size of the sample N | Pre outlier removal | 32 | 21 |

| Post outlier removal | 26 | 19 | |

| Regression and p-value | pre-outlier removal | , | , |

| post-outlier removal | , | , | |

| Shapiro–Wilk test p-value | pre-outlier removal | ||

| post-outlier removal |

References

- Swenor, B.; Ehrlich, J. Ageing and vision loss: Looking to the future. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e385–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xue, Y.; Hu, G.; Lin, T.; Gou, J.; Yin, T.; He, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. A comprehensive review on contact lens for ophthalmic drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2018, 281, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Aranguez, A.; Colligris, B.; Pintor, J. Contact lenses: Promising devices for ocular drug delivery. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2013, 29, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.; Hui, A.; Phan, C.M.; Read, M.; Azar, D.; Buch, J.; Ciolino, J.; Naroo, S.; Pall, B.; Romond, K.; et al. CLEAR - Contact lens technologies of the future. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2021, 44, 398–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciolino, J.; Dohlman, C.; Kohane, D. Contact lenses for drug delivery. Semin. Ophthalmol. 2009, 24, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Torres-Luna, C.; Azadi, M.; Domszy, R.; Hu, N.; Yang, A.; David, A. Evaluation of commercial soft contact lenses for ocular drug delivery: A review. Acta Biomater. 2020, 115, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreddu, R.; Vigolo, D.; Yetisen, A. Contact lens technology: From fundamentals to applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1900368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson & Johnson Vision Care. Johnson & Johnson Vision Care Receives FDA Approval for ACUVUE® Theravision™ with Ketotifen—World’s First and Only Drug-Eluting Contact Lens. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/johnson–johnson-vision-care-receives-fda-approval-for-acuvue-theravision-with-ketotifen–worlds-first-and-only-drug-eluting-contact-lens-301493964.html (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Silbert, J. A review of therapeutic agents and contact lens wear. J. Am. Optom. Assoc. 1996, 67, 165–172. [Google Scholar]

- Karlgard, C.C.S.; Wong, N.S.; Jones, L.W.; Moresoli, C. In vitro uptake and release studies of ocular pharmaceutical agents by silicon-containing and p-HEMA hydrogel contact lens materials. Int. J. Pharm. 2003, 257, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Li, X.; Sun, F. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of ketotifen fumarate-loaded silicone hydrogel contact lenses for ocular drug delivery. Drug Deliv. 2011, 18, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, A.; Bajgrowicz-Cieslak, M.; Phan, C.M.; Jones, L. In vitro release of two anti-muscarinic drugs from soft contact lenses. Clin. Ophthalmol. 2017, 11, 1657–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Luna, C.; Hu, N.; Fan, X.; Domszy, R.; Yang, J.; Briber, R.; Yang, A. Extended delivery of cationic drugs from contact lenses loaded with unsaturated fatty acids. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2020, 155, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajgrowicz, M.; Phan, C.M.; Subbaraman, L.; Jones, L. Release of Ciprofloxacin and Moxifloxacin From Daily Disposable Contact Lenses From an In Vitro Eye Model. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2015, 56, 2234–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, C.M.; Bajgrowicz, M.; Gao, H.; Subbaraman, L.; Jones, L. Release of Fluconazole from Contact Lenses Using a Novel In Vitro Eye Model. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2016, 93, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, C.M.; Shukla, M.; Walther, H.; Heynen, M.; Suh, D.; Jones, L. Development of an In Vitro Blink Model for Ophthalmic Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Horikawa, S.; Venkatesh, S.; Saha, J.; Hong, J.; Byrne, M. Zero-order therapeutic release from imprinted hydrogel contact lenses within in vitro physiological ocular tear flow. J. Control. Release 2007, 124, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, P.; Chauhan, A. Effect of the surface layer on drug release from delefilcon—A (Dailies Total1®) contact lenses. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 529, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanier, O.L.; Manfre, M.; Kulkarni, S.; Bailey, C.; Chauhan, A. Combining modeling of drug uptake and release of cyclosporine in contact lenses to determine partition coefficient and diffusivity. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 164, 105891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenta, A.; Serro, A.; Paradiso, P.; Saramago, B.; Colaço, R. Diffusion-Based Design of Multi-Layered Ophthalmic Lenses for Controlled Drug Release. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.C.; Kim, J.; Chauhan, A. Extended delivery of hydrophilic drugs from silicone-hydrogel contact lenses containing vitamin E diffusion barriers. Biomaterials 2010, 31, 4032–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.C.; Chauhan, A. Extended cyclosporine delivery by silicone–hydrogel contact lenses. J. Control. Release 2011, 154, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.C.; Chauhan, A. Modeling Ophthalmic Drug Delivery by Soaked Contact Lenses. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 3718–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Luke, R. Mathematical Models of Drug Delivery via a Contact Lens During Wear. La Mat. 2024, 3, 1510–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoletto, N.; Saramago, B.; Serro, A.; Chauhan, A. A physiology-based mathematical model to understand drug delivery from contact lenses to the back of the eye. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 1939–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gause, S.; Hsu, K.H.; Shafor, C.; Dixon, P.; Powell, K.C.; Chauhan, A. Mechanistic modeling of ophthalmic drug delivery to the anterior chamber by eye drops and contact lenses. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 233, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. Mathematical modeling of drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2008, 364, 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. Modeling of diffusion controlled drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dixon, P.; Fentzke, R.; Bhattacharya, A.; Konar, A.; Hazra, S.; Chauhan, A. In vitro drug release and in vivo safety of vitamin E and cysteamine loaded contact lenses. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 544, 380–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gay, K. LinkedIn Profile. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/in/kerstyn-gay-09230121b (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Hsu, K.H.; Carbia, B.; Plummer, C.; Chauhan, A. Dual drug delivery from vitamin E loaded contact lenses for glaucoma therapy. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2015, 94, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Luna, C.; Hu, N.; Tammareddy, T.; Domszy, R.; Yang, J.; Wang, N.; Yang, A. Extended delivery of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs through contact lenses loaded with Vitamin E and cationic surfactants. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2019, 42, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA). Database. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/devicesatfda/index.cfm (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Green, J. 510(k) Summary K182902. 2018. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/cdrh_docs/pdf18/K182902.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Rhea, A. Clinical Review of ACUVUE Theravision with Ketotifen. 2017. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/02_22388%20etafilcon%20clinical%20prea.pdf (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Hutter, J.; Green, J.; Eydelman, M. Proposed silicone hydrogel contact lens grouping system for lens care product compatibility testing. Eye Contact Lens 2012, 38, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, B. The Evolution of Silicone Hydrogel Lenses. 2008. Available online: https://www.clspectrum.com/issues/2008/june/the-evolution-of-silicone-hydrogel-lenses (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Chatterjee, S.; Upadhyay, P.; Mishra, M.; Dhara, S.; Akshara, M.; Pal, K.; Zaidi, Z.; Iqbal, S.; Misra, S. Advances in chemistry and composition of soft materials for drug releasing contact lenses. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 36751–36777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PubChem. National Library of Medicine Database. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- ChemSpider. Search and Share Chemistry. Available online: https://www.chemspider.com/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Thal, D.; Sun, B.; Feng, D.; Nawaratne, V.; Leach, K.; Felder, C.; Bures, M.; Evans, D.; Weis, W.; Bachhawat, P.; et al. Crystal structures of the M1 and M4 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors. Nature 2016, 531, 335–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lui, A.; Polis, T.; Cicutti, N. Densities of cerebrospinal fluid and spinal anaesthetic solutions in surgical patients at body temperature. Can. J. Anaesth. 1998, 45, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Na, D. Simultaneous Determination of Cysteamine and Cystamine in Cosmetics by Ion-Pairing Reversed-Phase High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. Toxicol. Res. 2019, 35, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsson, T. Drug Stability for Pharmaceutical Sciences; Loftsson, T., Ed.; Academic Press: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Housiny, S.; Shams Eldeen, M.A.; El-Attar, Y.A.; Salem, H.A.; Attia, D.; Bendas, E.R.; El-Nabarawi, M.A. Fluconazole-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles topical gel for treatment of pityriasis versicolor: Formulation and clinical study. Drug Deliv. 2018, 25, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciences, B. Best of Chemicals. Available online: https://www.bocsci.com/ (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- ChemSrc. Ketorolac. Available online: https://www.chemsrc.com/en/cas/74103-06-3_895499.html (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Shahid, M.; Hussain, A.; Khan, A.; Ramzan, M.; Alaofi, A.; Alanazi, A.; Alanazi, M.; Rauf, M. Ketoconazole-Loaded Cationic Nanoemulsion: In Vitro–Ex Vivo–In Vivo Evaluations to Control Cutaneous Fungal Infections. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 20267–20279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatarchuk, T.; Soltys, L.; Macyk, W. Magnetic adsorbents for removal of pharmaceuticals: A review of adsorption properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 384, 122174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uivarosi, V. Metal complexes of quinolone antibiotics and their applications: An update. Molecules 2013, 18, 11153–11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez-Bravo, E.; Alonso-Calderon, A.; Sanchez-Calvario, L.; Castaneda-Roldan, E.; Vidal Robles, E.; Salazar-Robles, G. Characterization of the Degradation Products from the Red Dye 40 by Enterobacteria. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 10, 2569–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ChemicalBook. Database. Available online: www.chemicalbook.com (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Kim, S.; Ozalp, E.; Darwish, M.; Weldon, J. Electrically gated nanoporous membranes for smart molecular flow control. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 20740–20747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BenSaïda, A. Shapiro-Wilk and Shapiro-Francia Normality Tests. 2025. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/13964-shapiro-wilk-and-shapiro-francia-normality-tests (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- Keine, C. Moods Median Test. 2025. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/fileexchange/70081-moods-median-test (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Kim, G.; Kim, J.H.; Noh, H. Influence of Solution pH on Drug Release from Ionic Hydrogel Lens. Macromol. Res. 2019, 27, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, C.-M.; Subbaraman, L.N.; Jones, L. In vitro uptake and release of natamycin from conventional and silicone hydrogel contact lens materials. Eye Contact Lens 2013, 39, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thang, N.; Chien, T.; Cuong, D. Polymer-Based Hydrogels Applied in Drug Delivery: An Overview. Gels 2023, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhao, M.; Xing, D.; Zhang, J.; Fang, T.; Zhang, F.; Nie, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, J. Contact lens as an emerging platform for ophthalmic drug delivery: A systematic review. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Mooney, D. Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez-Martinez, V.; Mann, A.; Lydon, F.; Molock, F.; Layton, S.; Toolan, D.; Howse, J.; Topham, P.; Tighe, B. The influence of structure and morphology on ion permeation in commercial silicone hydrogel contact lenses. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2021, 109, 137–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.C.; Chauhan, A. Ion transport in silicone hydrogel contact lenses. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 399, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soluri, A.; Hui, A.; Jones, L. Delivery of Ketotifen Fumarate by Commercial Contact Lens Materials. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2012, 89, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, A.R.; Maulvi, F.A.; Pandya, M.M.; Ranch, K.M.; Vyas, B.A.; Shah, S.A.; Shah, D.O. Co-delivery of timolol and hyaluronic acid from semi-circular ring-implanted contact lenses for the treatment of glaucoma: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 1580–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.C.T.; Dowling, J.; Ryan, R.; McLoughlin, P.; Fitzhenry, L. Pharmaceutical-loaded contact lenses as an ocular drug delivery system: A review of critical lens characterization methodologies with reference to ISO standards. Contact Lens Anterior Eye 2021, 44, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Therapeutics | Lenses |

|---|---|---|

| Peng et al. [21] | Fluconazole Timolol | Balafilcon A |

| Lotrafilcon A | ||

| Lotrafilcon B | ||

| Senofilcon A | ||

| Xu et al. [11] | Ketotifen fumarate | SCL1 SCL2 SCL3 |

| Bajgrowicz et al. [14] | Moxifloxacin | Delefilcon A |

| Etafilcon A | ||

| Narafilcon A | ||

| Nelfilcon A | ||

| Ocufilcon B | ||

| Omafilcon A | ||

| Somofilcon A | ||

| Hsu et al. [31] | Dorzolamide | Senofilcon A |

| Phan et al. [15] | Fluconazole | Delefilcon A Etafilcon A Narafilcon A Nelfilcon A Ocufilcon B Omafilcon A Somofilcon A |

| Dixon and Chauhan [18] | Levofloxacin Timolol | Delefilcon A |

| Hui et al. [12] | Atropine Pirenzepine | Delefilcon A Etafilcon A Narafilcon A Nelfilcon A Ocufilcon B Omafilcon A |

| Dixon et al. [29] | Cysteamine | Narafilcon A Senofilcon A |

| Torres-Luna et al. [32] | Flurbiprofen sodium Ketorolac tromethamine | Narafilcon A Senofilcon A |

| Torres-Luna et al. [13] | Bupivacaine Ketotifen fumarate Tetracaine hydrochloride | Narafilcon A Senofilcon A |

| Phan et al. [16] | Red dye | Etafilcon A Senofilcon A |

| Contact Lens Monomers | Commercial Name | FDA Group | Ionic | Water Content [%] | Thickness [mm] | Radius R [mm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nelfilcon A PVA, FMA, PEG [14] | DAILIES Aquacomfort Plus | II | No | 69 [14] | [14] | [14] |

| Omafilcon A HEMA, PC, EGDMA [14] | Proclear 1-Day | II | No | 62 [14] | [14] | [14] |

| Etafilcon A HEMA, MAA [14] | 1-Day Acuvue Moist | IV | Yes | 58 [14] | [14,16] | [14,16] |

| Ocufilcon B HEMA, PVP, MAA [14] | Biomedics 1-Day | IV | Yes | 53 [14] | [14] | [14] |

| Balafilcon A TRIS, NVP [37] | Pure Vision 2 | V | Yes | 36 [21] | [21] | [21] |

| Delefilcon A Not disclosed [14] | DAILIES TOTAL 1 | V | No | 33 [14] | [14] | [14] |

| Lotrafilcon A DMA, TRIS, Siloxane [38] | NIGHT & DAY | V | No | 24 [21] | [21] | [21] |

| Lotrafilcon B DMA, TRIS, Siloxane [38] | O2 Optix | V | No | 33 [21] | [21] | [21] |

| Narafilcon A HEMA, DMA, TEGDMA, Siloxane, MPDMS, PVP [14] | 1-Day ACUVUE TruEye | V | No | 46 [14] | [14] | [14] |

| SCL1 DMA, TRIS, EGDMA, MA-PDMS-MA [11] | - | V | - | 38 [11] | [11] | [11] |

| SCL2 DMA, TRIS, EGDMA, MA-PDMS-MA [11] | - | V | - | 30 [11] | [11] | [11] |

| SCL3 DMA, TRIS, EGDMA, MA-PDMS-MA [11] | - | V | - | 25 [11] | [11] | [11] |

| Senofilcon A HEMA, DMA, Siloxane, TEGDMA, PVP, MPDMS [14] | Acuvue Oasys | V | No | 20 [14,21] | [14,21] | [14,21] |

| Somofilcon A Not disclosed [14] | Clariti 1-Day | V | - | 56 [14] | [14] | [14] |

| Therapeutic | Molecular Mass [g/mol] | Density [g/cm3] | Molecular Volume [cm3/mol] | Charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atropine | [39] | [40] | Positive [41] | |

| Bupivacaine | [39] | [42] | Positive [13] | |

| Cysteamine | [39] | [40] | Positive [43] | |

| Dorzolamide | [39] | [40] | 202.78 | Positive [44] |

| Fluconazole | 306.27 [39] | 1.50 [40] | 204.18 | Negative [45] |

| Flurbiprofen sodium | [39] | [40] | 240.42 | Negative [41] |

| Ketotifen fumarate | [39] | [46] | Positive [13] | |

| Ketorolac tromethamine | [39] | [47] | Positive [32,48] | |

| Levofloxacin | [39] | [40] | Positive [49] | |

| Moxifloxacin | [39] | [40] | 286.74 | Positive [50] |

| Pirenzepine | [39] | [40] | 270.31 | Positive [41] |

| Red dye | [39] | [16] | Negative [51] | |

| Tetracaine hydrochloride | [39] | [52] | Positive [13] | |

| Timolol | [39] | [40] | Positive [53] |

| Lens Drug | Thickness τ [mm] | Radius R [mm] | Initial Mass Loaded πR2τcl0 [μg] | Estimated Value DPDE [] | Reported Value D [] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEMA Cyclosporine | 0.15 | 6.0 | 20.00 | 15.80 | 15.91 ± 1.90 [19] |

| HEMA Levofloxacin | 0.30 | 6.0 | 24.52 | 2780 | 2700 [20] |

| Senofilcon A Red dye | 0.084 | 7.150 | 47,800 ± 2700 | mean: 25 range: 17–30 | 27.04 [24] |

| Etafilcon A Red dye | 0.080 | 7.150 | 22,400 ± 2000 | mean: 776 range: 607–800 | 813.60 [24] |

| Water Content | Thickness | Radius | Molecular Density | Molecular Mass | Molecular Volume | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water content | |||||||

| * | |||||||

| Thickness | |||||||

| * | |||||||

| Radius R | |||||||

| * | |||||||

| Molecular density | |||||||

| * | |||||||

| Molecular mass | |||||||

| Molecular volume | |||||||

| * | * | ||||||

| * | * | * |

| Estimated Diffusion Coefficient | Silicone Hydrogel (SH) Lenses (N = 36) | Conventional Hydrogel (CH) Lenses (N = 17) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD Median | ± | ||

| Group V (N = 36) | Group II † (N = 8) | Group IV † (N = 9) | |

| Mean | |||

| ± SD | same as | ||

| SH Lenses | |||

| Median | 1.231 | ||

| t-test, p-value | Group II † ≠ Group IV †, * (Group II † > Group IV †, *) | ||

| Mood’s median test, p-value | SH ≠ CH, * | ||

| Group II † ≠ Group V, * | |||

| Group IV † ≠ Group V, * | |||

| Estimated Diffusion Coefficient | Ionic Lenses † (N = 10) | Non-Ionic Lenses (N = 38) | Unknown Ionicities Lenses (N = 5) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.622 | ||

| ± | ± | ± | ± |

| SD | |||

| Median | |||

| Mood’s median test, p-value | Ionic † ≠ Non-ionic, * | ||

| Ionic † ≠ Unknown ionicity, | |||

| Non-ionic ≠ Unknown ionicity, | |||

| 75 < Vol < 275 [cm3/mol] (N = 26) | 275 < Vol < 650 [cm3/mol] (N = 19) | |

|---|---|---|

| Outliers: Lens, Therapeutic | Narafilcon A, KTH Etafilcon A, Piren Nelefilcon A, Piren Narafilcon A, Piren Narafilcon A, THCL Narafilcon A, FBNA | Delefilcon A, Moxi Narafilcon A, Moxi |

| Coefficient of determination, , p-value | , * | , * |

| Regression coefficient, , 90% Confidence interval () |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carichino, L.; Maki, K.L.; Gunputh, N.D.; Phan, C.-M. A Meta-Analysis of In Vitro Release of Hydrophilic Therapeutics from Contact Lenses Using Mathematical Modeling. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111479

Carichino L, Maki KL, Gunputh ND, Phan C-M. A Meta-Analysis of In Vitro Release of Hydrophilic Therapeutics from Contact Lenses Using Mathematical Modeling. Pharmaceutics. 2025; 17(11):1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111479

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarichino, Lucia, Kara L. Maki, Narshini D. Gunputh, and Chau-Minh Phan. 2025. "A Meta-Analysis of In Vitro Release of Hydrophilic Therapeutics from Contact Lenses Using Mathematical Modeling" Pharmaceutics 17, no. 11: 1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111479

APA StyleCarichino, L., Maki, K. L., Gunputh, N. D., & Phan, C.-M. (2025). A Meta-Analysis of In Vitro Release of Hydrophilic Therapeutics from Contact Lenses Using Mathematical Modeling. Pharmaceutics, 17(11), 1479. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17111479