Abstract

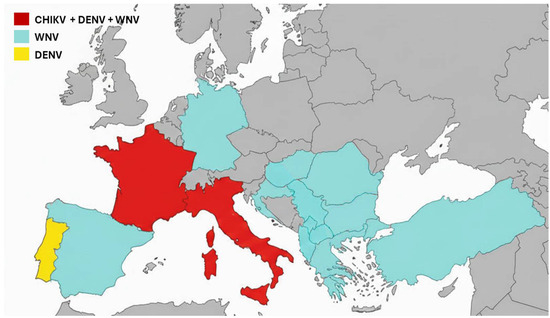

The year 2025 likely marks a turning point in both the perception and the reality of mosquito-borne arboviral diseases in Europe. While chikungunya and dengue viruses have long been regarded as tropical illnesses confined to intertropical regions, West Nile virus has circulated for decades in temperate areas, including southern Europe. Nevertheless, all three mosquito-borne viruses are now increasingly established across the European continent. This evolution reflects a profound transformation of the European epidemiological landscape, where arboviral diseases are increasingly emerging as endemic and seasonal threats. This shift concerns not only the scale but also the dynamics of transmission, with the appearance of newly affected regions, an earlier onset of the transmission season, and a broader diversity of arboviruses involved. Europe is thus entering a new phase in which longer, wider, and more intense transmission of vector-borne diseases is likely to become the new norm requiring strengthened preparedness.

4. Convergence of Factors Favoring Emergence and Re-Emergence, with Climate Change as a Primary Driver

The continuous rise in arboviral cases in Europe results from the convergence of several additive factors. Climate change is altering distribution ranges of arthropod vectors and lengthening transmission seasons. Consequently, the mosquito-borne virus transmission season now starts earlier and ends later. Rising average temperatures also promote viral replication within the vector and accelerate its blood-feeding cycle, thereby increasing the probability of viral transmission [31]. Most climate models predict a northward expansion of transmission across the continent, accompanied by increasingly prolonged transmission windows [32,33]. Traveler flows, notably tourism and migration, facilitate virus introduction via viremic travelers. Furthermore, rapid, often poorly planned urbanization creates environments favorable to mosquito proliferation, providing multiple larval breeding sites in urban and peri-urban areas. This phenomenon can be further amplified by poorly regulated urban greening strategies, which generate shelters for mosquitoes and promote larval habitats. Moreover, most European countries lack historical experience in managing arboviral diseases. Surveillance systems are often fragmented, healthcare professionals are insufficiently trained to recognize clinical manifestations of arboviral infections, and vector control policies are highly heterogeneous, sometimes even within the same region. This situation limits the capacity for rapid and coordinated responses.

The climatic conditions of 2025 were particularly favorable for arboviral transmission, with one of the warmest years on record. The year was marked by early heat episodes (late May–early June) and daily temperatures frequently exceeding 30 °C, with nights often remaining above 20 °C, while the preceding winter was milder than usual [34]. In addition, precipitation patterns included intense rainfall followed by dry periods, favoring the accumulation of standing water suitable for mosquito oviposition. Altogether, these conditions enabled prolonged vector activity and promoted the emergence of local epidemic foci, with transmission peaks observed from May through the end of September.

Another important driver of arbovirus expansion is biodiversity loss. Reduced predator populations and simplified ecosystems favor arthropod vectors proliferation by eliminating natural regulatory mechanisms. This ecological imbalance, combined with urbanization, creates optimal conditions for vector expansion and arbovirus transmission [35,36]. Moreover globalisation accelerates the spread of invasive vectors. International trade, particularly in used tires and ornamental plants, has facilitated the introduction of Aedes species from endemic regions to Europe. Combined with increased air travel, these pathways enable rapid dissemination of both vectors and viruses [37]. Increased freight volume, accelerated delivery timelines, and expanding commercial routes all amplify the probability that vector species are transported from endemic regions to Europe.

5. Major Challenges for European Public Health

Europe is entering a phase in which arboviral diseases are becoming seasonal endemic threats. This evolution poses several major challenges. Entomological and epidemiological surveillance remain insufficient in many European countries, not only because systems are unevenly implemented, but also due to several structural limitations. Case definitions and reporting criteria differ between countries, complicating direct comparisons of incidence and hindering timely interpretation of epidemiological trends [38,39]. Diagnostic laboratory capacities remain highly heterogeneous across Europe. Some countries rely on only a few reference facilities, whereas others lack the capability to perform confirmatory molecular or serological testing, leading to diagnostic delays and substantial underreporting. In addition, surveillance of arboviral diseases still relies largely on passive clinical reporting, a system in which mild or atypical cases, particularly common for DENV or WNV, are frequently missed. Vector surveillance programs are equally heterogeneous, varying widely in frequency, methodology, and the entomological indicators monitored. While some countries perform routine mosquito trapping and viral testing, others operate only seasonal or reactive surveillance, generating gaps in early warning capacity. Collectively, these limitations hinder coordinated risk assessment and delay the implementation of effective vector-control measures. With case numbers still relatively low, healthcare professionals are not always adequately trained to recognize the polymorphic symptoms of chikungunya or other arboviruses such as WNV. Cross-border coordination is also suboptimal, with vector control policies varying widely between countries and data sharing remaining limited.

A more comprehensive approach is therefore essential to better anticipate epidemic waves, coordinate interventions, and harmonize responses. Effective preparation requires the development of strategic priorities at the European level. Integrated surveillance, combining entomological, climatic, and clinical data, needs to be strengthened. Tools such as real-time vector mapping and climate modeling could help anticipate the highest-risk periods and enable more targeted surveillance measures.

Diagnosis of arboviral diseases represents another major challenge. Clinical presentations are often nonspecific, multiple virus strains and lineages with varying virulence may co-circulate, and the limited availability of rapid, sufficiently specific and sensitive tests complicates early detection. Cross-reactivity observed in many serological, and even molecular, tests further hampers diagnostic reliability. It is therefore crucial to strengthen the diagnostic capacities of European laboratories, including university hospitals, to continue developing multiplex tools suitable for European contexts and to promote access to testing in high-risk areas, including in primary care. In this context, structured laboratory networks and a degree of centralization of highly specialized capacities are essential to ensure diagnostic quality and efficiency [39,40] The recent designation of the European Union Reference Laboratory for Public Health on Vector-borne Viral Pathogens provides a framework to harmonize protocols, distribute reference materials, coordinate external quality assessments and support national expert laboratories for confirmatory testing and training

Vaccine development must also be accelerated. Two chikungunya vaccines, IXCHIQ (Valneva) and Vimkunya (Bavarian Nordic), have recently been approved in Europe [41,42,43]. Ensuring their availability in high-risk areas and for vulnerable populations, including the elderly, immunocompromised individuals, and healthcare workers, is essential to limit the impact of future outbreaks. Regarding DENV, several vaccine candidates are under evaluation or already available in certain countries. However, their variable efficacy depending on serotype and prior immunity necessitates a cautious and targeted deployment strategy [44,45]. For WNV, no human vaccine is currently available, unlike equine vaccines, which have proven effective. Research in this field must therefore be supported to develop preventive solutions tailored to the most at-risk populations. In addition, the development of antiviral therapies should be pursued to provide treatment options for infected individuals, particularly those at higher risk of severe disease.

Improved training of healthcare professionals constitutes another key pillar of the response. Arboviral diseases should be more fully integrated into continuing medical education programs, and clinical guidelines adapted to new European contexts should be widely disseminated. Community engagement is also crucial. Public awareness campaigns on preventive measures, such as eliminating larval habitats and using personal protective strategies, should be strengthened, particularly in urban and peri-urban areas, which are most exposed to arboviral risk.

A One Health approach, integrating human, animal, and environmental health sectors, is essential for arbovirus monitoring, particularly for WNV, given the diversity and still incomplete knowledge of the avian reservoir species involved in its transmission. This requires integrated strategies that combine entomological, veterinary, and human surveillance activities, as well as enhanced collaboration between human and animal health sectors to enable rapid risk identification. Integrated One Health surveillance systems involving mosquitoes and birds across several European countries have already demonstrated their usefulness for the early detection of WNV circulation, with Italy providing a particularly illustrative example of how coordinated, multi-sectoral monitoring can be effectively implemented. Such systems must be integrated with USUV surveillance, as this virus co-circulates with WNV in both space and time. Their eco-epidemiology relies on complex interactions between Culex vectors, diverse avian reservoirs, and incidental mammalian hosts, and may complicate diagnosis due to serological cross-reactivity [1]. Likewise, horses act as highly sensitive sentinel hosts for WNV, providing a critical interface between veterinary and human health surveillance. Strengthening these animal-health components, together with robust local and national integrated surveillance programs, is essential for the timely and effective detection of future outbreaks and for improving Europe’s preparedness to manage potential epidemic situations.

6. Conclusions

The year 2025 should not be seen as an anomaly in the epidemiological picture of mosquito-borne arboviral circulation in Europe but as a warning signal. Arboviral diseases are now clearly identified as seasonal threats in Europe and public health systems must adapt to this changing situation. It is time to shift from a reactive mindset to a sustained culture of preparedness, integrating arboviruses into public health plans, engaging citizens, and investing in research, surveillance, and vaccination. Only by implementing these measures can Europe face this new epidemiological reality, in which viruses once considered tropical are becoming recurrent seasonal threats.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Simonin, Y. Circulation of West Nile Virus and Usutu Virus in Europe: Overview and Challenges. Viruses 2024, 16, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J.J.; Haussig, J.M.; Aberle, S.W.; Pervanidou, D.; Riccardo, F.; Sekulić, N.; Bakonyi, T.; Gossner, C.M. Epidemiology of human West Nile virus infections in the European Union and European Union enlargement countries, 2010 to 2018. Eurosurveillance 2021, 26, 2001095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sejvar, J.J. Clinical Manifestations and Outcomes of West Nile Virus Infection. Viruses 2014, 6, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Surveillance of West Nile Virus Infections in Humans and Animals in Europe, Monthly Report. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/west-nile-fever/surveillance-and-disease-data/disease-data-ecdc (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Carrasco, L.; Utrilla, M.J.; Fuentes-Romero, B.; Fernandez-Novo, A.; Martin-Maldonado, B. West Nile Virus: An Update Focusing on Southern Europe. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SPF. Chikungunya, Dengue, Zika et West Nile en France Hexagonale. Bulletin de la Surveillance renforcée du 5 Novembre 2025. Available online: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/maladies-et-traumatismes/maladies-a-transmission-vectorielle/chikungunya/documents/bulletin-national/chikungunya-dengue-zika-et-west-nile-en-france-hexagonale.-bulletin-de-la-surveillance-renforcee-du-5-novembre-2025 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Gonzalez, G.; Migné, C.V.; Duvignaud, A.; Martin-Latil, S.; Bigeard, C.; Touzet, T.; Fontaine, A.; Zientara, S.; de Lamballerie, X.; Malvy, D. Paradigm Shift Toward “One Health” Monitoring of Culex-Borne Arbovirus Circulation in France: The 2022 Inaugural Spotlight on West Nile and Usutu Viruses in Nouvelle-Aquitaine. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12, ofaf243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Seasonal Surveillance of Dengue in the EU/EEA, Weekly Report. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/dengue/surveillance-and-updates/seasonal-surveillance-dengue-eueea-weekly (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- Nasir, M.; Irfan, J.; Asif, A.B.; Khan, Q.U.; Anwar, H. Complexities of Dengue Fever: Pathogenesis, Clinical Features and Management Strategies. Discoveries 2024, 12, e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, N.; Hasan, M.N.; Onyango, J.; Billah, M.; Khan, S.; Papakonstantinou, D.; Paudyal, P.; Asaduzzaman, M. Global dengue epidemic worsens with record 14 million cases and 9000 deaths reported in 2024. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2025, 158, 107940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Seasonal Surveillance of Chikungunya Virus Disease in the EU/EEA, Weekly Report. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/chikungunya-virus-disease/surveillance-and-updates/seasonal-surveillance (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Worsening Spread of Mosquito-Borne Disease Outbreaks in EU/EEA, According to Latest ECDC Figures. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/worsening-spread-mosquito-borne-disease-outbreaks-eueea-according-latest-ecdc-figures?.com (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- OhAinle, M.; Balmaseda, A.; Macalalad, A.R.; Tellez, Y.; Zody, M.C.; Saborío, S.; Nuñez, A.; Lennon, N.J.; Birren, B.W.; Gordon, A.; et al. Dynamics of Dengue Disease Severity Determined by the Interplay Between Viral Genetics and Serotype-Specific Immunity. Sci. Transl. Med. 2011, 3, 114ra128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krutikov, M.; Manson, J. Chikungunya Virus Infection: An Update on Joint Manifestations and Management. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2016, 7, e0033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumence, E.; Piorkowski, G.; Traversier, N.; Amaral, R.; Vincent, M.; Mercier, A.; Ayhan, N.; Souply, L.; Pezzi, L.; Lier, C.; et al. Genomic insights into the re-emergence of chikungunya virus on Réunion Island, France, 2024 to 2025. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2500344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohers, C.; Vazeille, M.; Bernaoui, L.; Pascalin, L.; Meignan, K.; Mousson, L.; Jakerian, G.; Karch, A.; de Lamballerie, X.; Failloux, A.B. Aedes albopictus is a competent vector of five arboviruses affecting human health, greater Paris, France, 2023. Eurosurveillance 2024, 29, 2400271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, Z.; Segelmark, L.; Rocklöv, J.; Lillepold, K.; Sewe, M.O.; Briet, O.J.T.; Semenza, J.C. Impact of climate and Aedes albopictus establishment on dengue and chikungunya outbreaks in Europe: A time-to-event analysis. Lancet Planet. Health 2025, 9, e374–e383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón-Elbal, P.M.; Suárez-Balseiro, C.; De Souza, C.; Soriano-López, A.; Riggio-Olivares, G. History of research on Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Europe: Approaching the world’s most invasive mosquito species from a bibliometric perspective. Parasitol. Res. 2024, 123, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC, E.C. for D.P. and C. Aedes Albopictus—Current Known Distribution: June 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/aedes-albopictus-current-known-distribution-june-2025 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Santos, J.M.; Capinha, C.; Rocha, J.; Sousa, C.A. The current and future distribution of the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) on Madeira Island. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, M.I.; Notarides, G.; Meletiou, S.; Patsoula, E.; Kavran, M.; Michaelakis, A.; Bellini, R.; Toumazi, T.; Bouyer, J.; Petrić, D. Two invasions at once: Update on the introduction of the invasive species Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Cyprus—A call for action in Europe. Parasite 2023, 30, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Rúa, A.; Lourenço-De-Oliveira, R.; Mousson, L.; Vazeille, M.; Fuchs, S.; Yébakima, A.; Gustave, J.; Girod, R.; Dusfour, I.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; et al. Chikungunya virus transmission potential by local Aedes mosquitoes in the Americas and Europe. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazeille, M.; Moutailler, S.; Coudrier, D.; Rousseaux, C.; Khun, H.; Huerre, M.; Thiria, J.; Dehecq, J.S.; Fontenille, D.; Schuffenecker, I.; et al. Two Chikungunya isolates from the outbreak of La Reunion (Indian Ocean) exhibit different patterns of infection in the mosquito, Aedes albopictus. PLoS ONE 2007, 2, e1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsetsarkin, K.A.; McGee, C.E.; Volk, S.M.; Vanlandingham, D.L.; Weaver, S.C.; Higgs, S. Epistatic roles of E2 glycoprotein mutations in adaption of chikungunya virus to Aedes albopictus and Ae. aegypti mosquitoes. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Shan, C.; Zhu, Y.; Ma, E.; Wang, J.; Wang, P.; Shi, P.Y.; Cheng, G. A mutation-mediated evolutionary adaptation of Zika virus in mosquito and mammalian host. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2113015118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daudt-Lemos, M.; Ramos-Silva, A.; Faustino, R.; Noronha, T.G.d.; Vianna, R.A.d.O.; Cabral-Castro, M.J.; Cardoso, C.A.A.; Silva, A.A.; Carvalho, F.R. Rising Incidence and Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Emerging and Reemerging Arboviruses in Brazil. Viruses 2025, 17, 158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoellinger, B.; Parfut, A.; Grisard, M.; Martin-Latil, S.; Denis, J.; Augereau, O.; Gregorowicz, G.; Martinot, M.; Hansmann, Y.; Velay, A. Tick-borne encephalitis: An ancient pathology, but a current emergence in Europe. Infect. Dis. Now 2026, 56, 105187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gömer, A.; Lang, A.; Janshoff, S.; Steinmann, J.; Steinmann, E. Epidemiology and global spread of emerging tick-borne Alongshan virus. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2404271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, F.F.; Arce, O.A.; Díaz-Menéndez, M.; Belhassen-García, M.; González-Sanz, M. Changes in the epidemiology of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever: Impact of travel and a One Health approach in the European region. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 64, 102806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadar, D.; Simonin, Y. Human Usutu Virus Infections in Europe: A New Risk on Horizon? Viruses 2023, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellone, R.; Lechat, P.; Mousson, L.; Gilbart, V.; Piorkowski, G.; Bohers, C.; Merits, A.; Kornobis, E.; Reveillaud, J.; Paupy, C.; et al. Climate change and vector-borne diseases: A multi-omics approach of temperature-induced changes in the mosquito. J. Travel Med. 2023, 30, taad062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, S. Climate change impacts on vector-borne diseases in Europe: Risks, predictions and actions. Lancet Reg. Health-Eur. 2020, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, C.; McKenzie, T.; Gaw, I.M.; Dean, J.M.; Hammerstein, H.; von Knudson, T.A.; Setter, R.O.; Smith, C.Z.; Webster, K.M.; Patz, J.A.; et al. Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2022, 12, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus European Summer 2025—Hot in the West and South, Dry in the Southeast. Available online: https://climate.copernicus.eu/european-summer-2025-hot-west-and-south-dry-southeast (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Perrin, A.; Glaizot, O.; Christe, P. Worldwide impacts of landscape anthropization on mosquito abundance and diversity: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 6857–6871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunti, G.; Becker, N.; Benelli, G. Invasive mosquito vectors in Europe: From bioecology to surveillance and management. Acta Trop. 2023, 239, 106832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, T.; Russell, T.L.; Staunton, K.M.; Field, M.A.; Ritchie, S.A.; Burkot, T.R. A literature review of dispersal pathways of Aedes albopictus across different spatial scales: Implications for vector surveillance. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotakis, E.A.; Grau-Pujol, B.; Kelly, D.; Leite, P.P.; Martins, J.V.; Alves, M.J.; Di Luca, M.; Venturi, G.; Ferraro, F.; Franke, F.; et al. Description and comparison of national surveillance systems and response measures for Aedes-borne diseases in France, Italy and Portugal: A benchmarking study, 2023. Eurosurveillance 2025, 30, 2400515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reusken, C.B.; Ieven, M.; Sigfrid, L.; Eckerle, I.; Koopmans, M. Laboratory preparedness and response with a focus on arboviruses in Europe. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018, 24, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasbergen, L.M.R.; de Bruin, E.; Chandler, F.; Sigfrid, L.; Chan, X.H.S.; Hookham, L.; Wei, J.; Chen, S.; GeurtsvanKessel, C.H.; Scherbeijn, S.; et al. Multi-antigen serology and a diagnostic algorithm for the detection of arbovirus infections as novel tools for arbovirus preparedness in southeast Europe (MERMAIDS-ARBO): A prospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency New Chikungunya Vaccine for Adolescents from 12 and Adults. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/new-chikungunya-vaccine-adolescents-12-adults (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- European Medicines Agency Ixchiq. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/ixchiq (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- European Medicines Agency First Vaccine to Protect Adults from Chikungunya. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/first-vaccine-protect-adults-chikungunya (accessed on 31 May 2024).

- Sridhar, S.; Luedtke, A.; Langevin, E.; Zhu, M.; Bonaparte, M.; Machabert, T.; Savarino, S.; Zambrano, B.; Moureau, A.; Khromava, A.; et al. Effect of Dengue Serostatus on Dengue Vaccine Safety and Efficacy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, M.; Stollenwerk, N. The Impact of Serotype Cross-Protection on Vaccine Trials: DENVax as a Case Study. Vaccines 2020, 8, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).