Modelling the Variability in Immunity Build-Up and Waning Following RNA-Based Vaccination

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Basic Assumptions

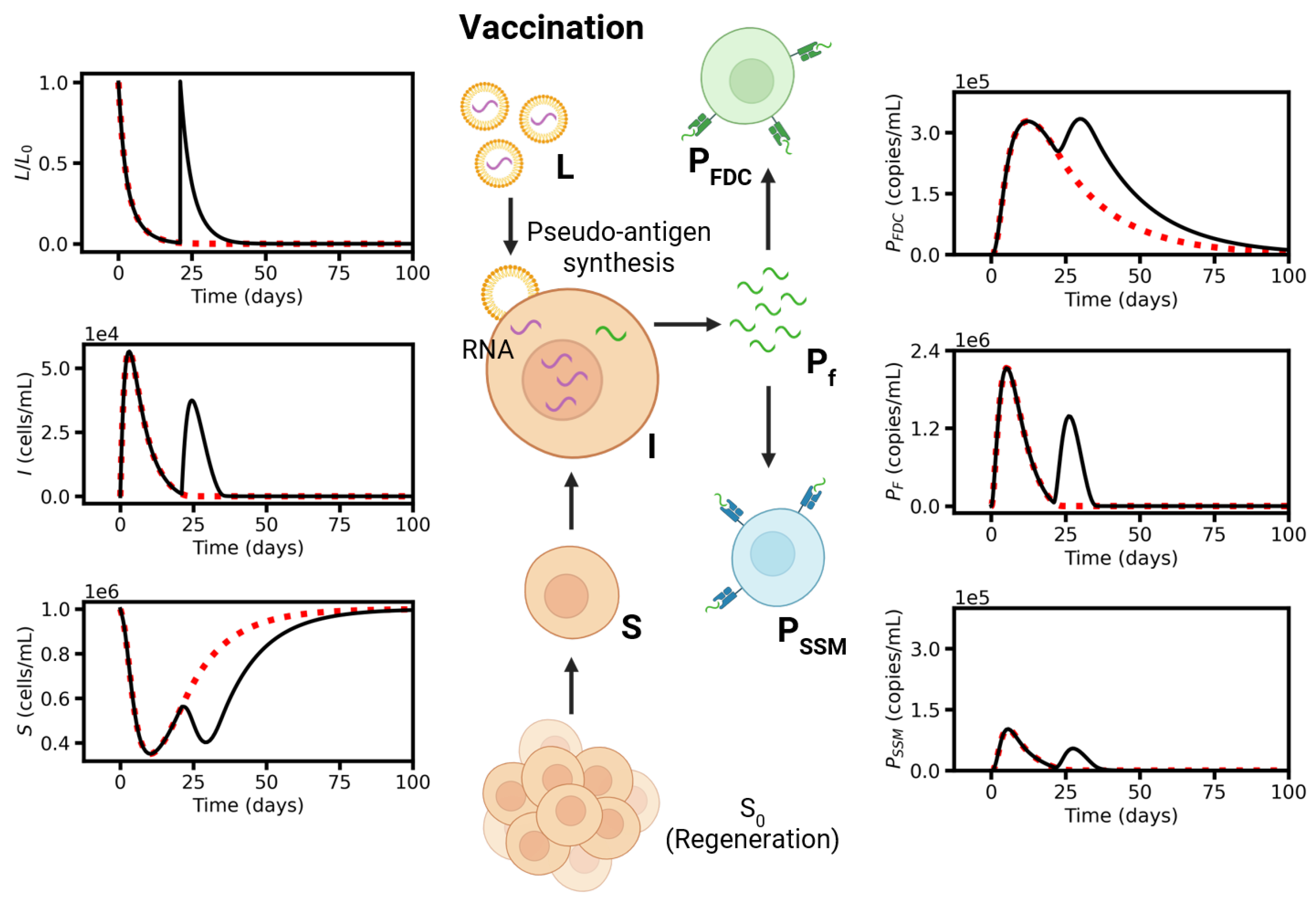

2.1. Vaccination Model

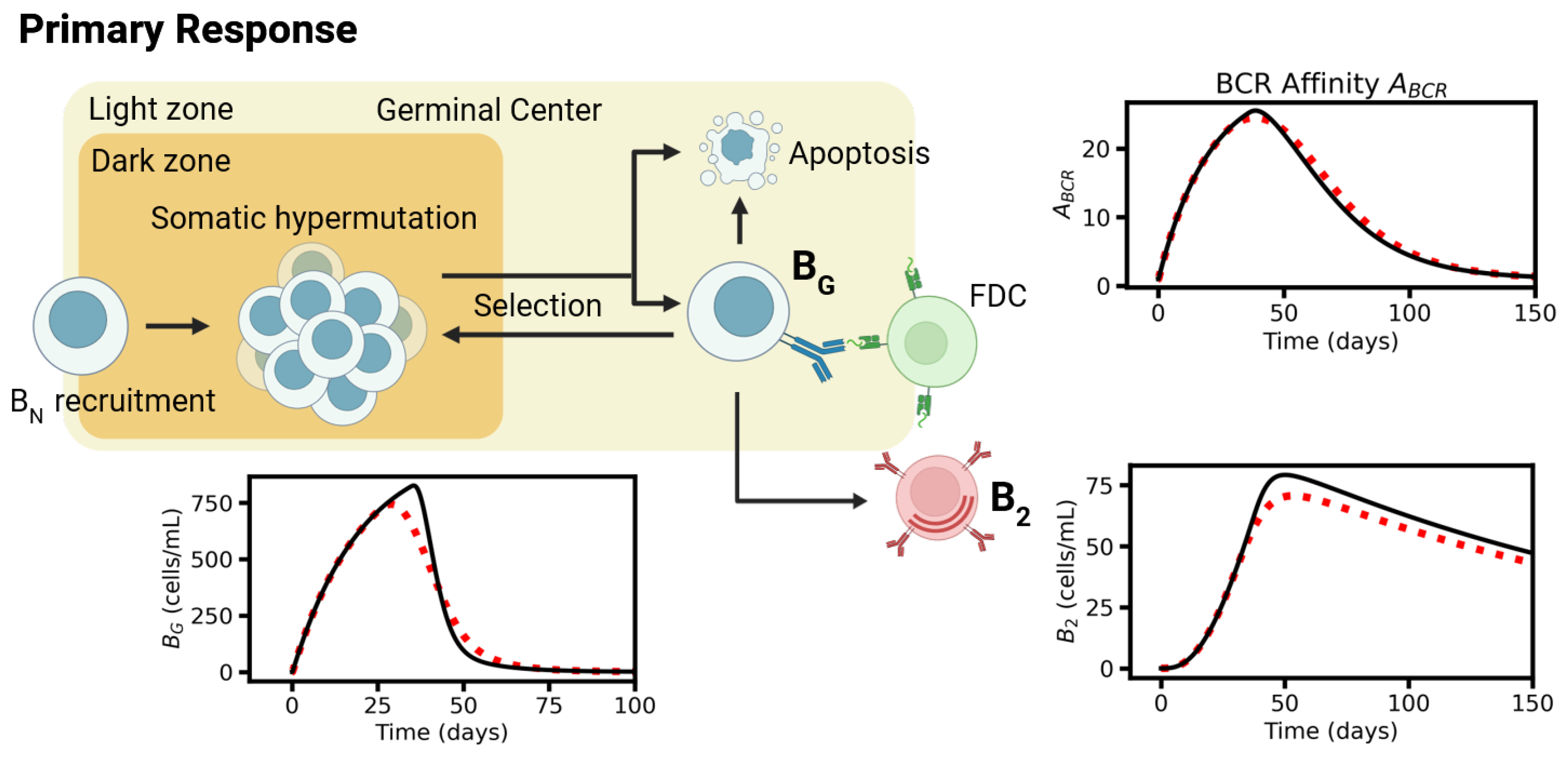

2.2. Primary Response Model

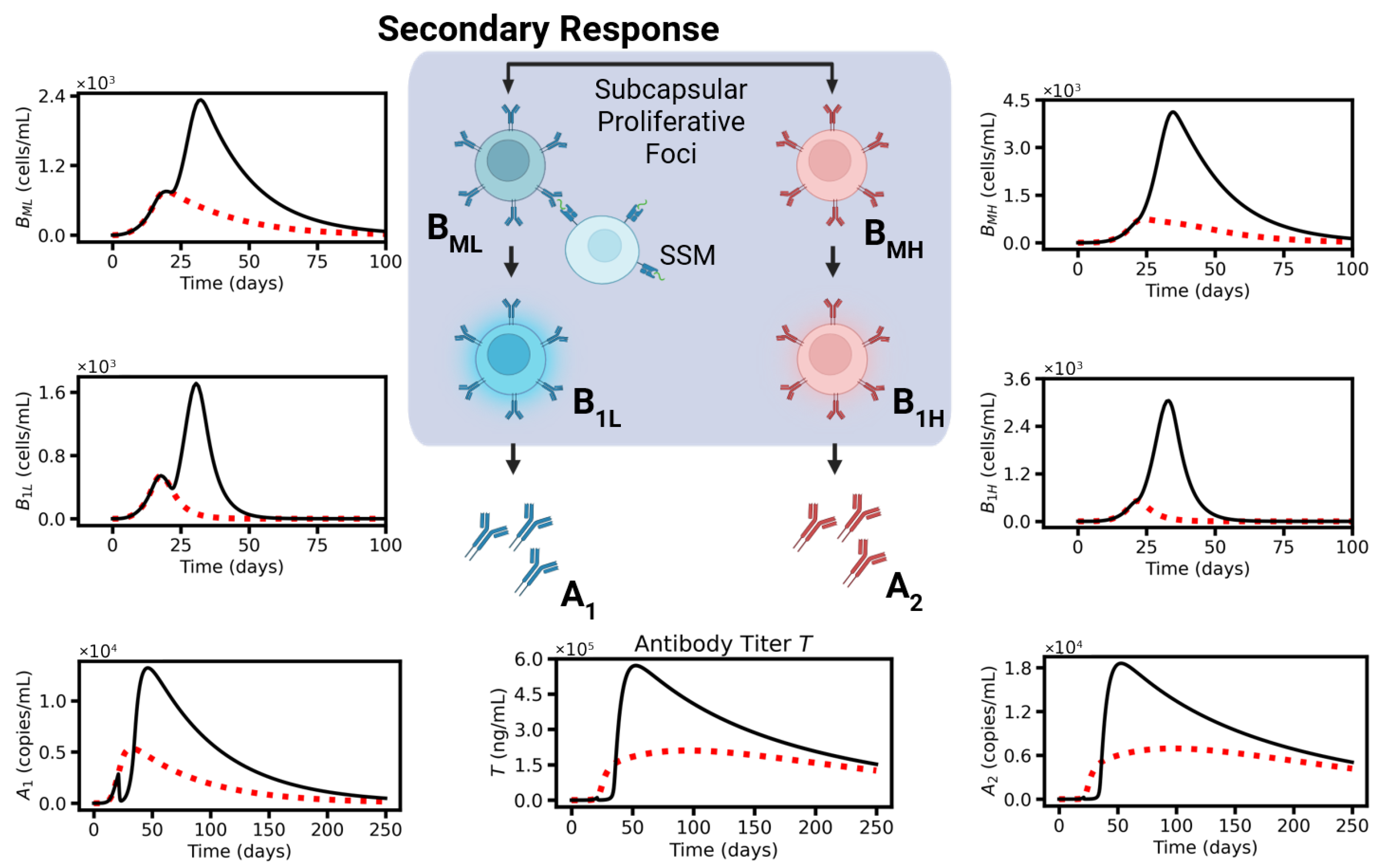

2.3. Secondary Response

3. Mathematical Formulation: Vaccination Model

3.1. LNPs

3.2. Susceptible Cells

3.3. Infected Cells

3.4. Pseudo-Antigen P

3.5. Injected LPC Density

3.6. Second Vaccination Time

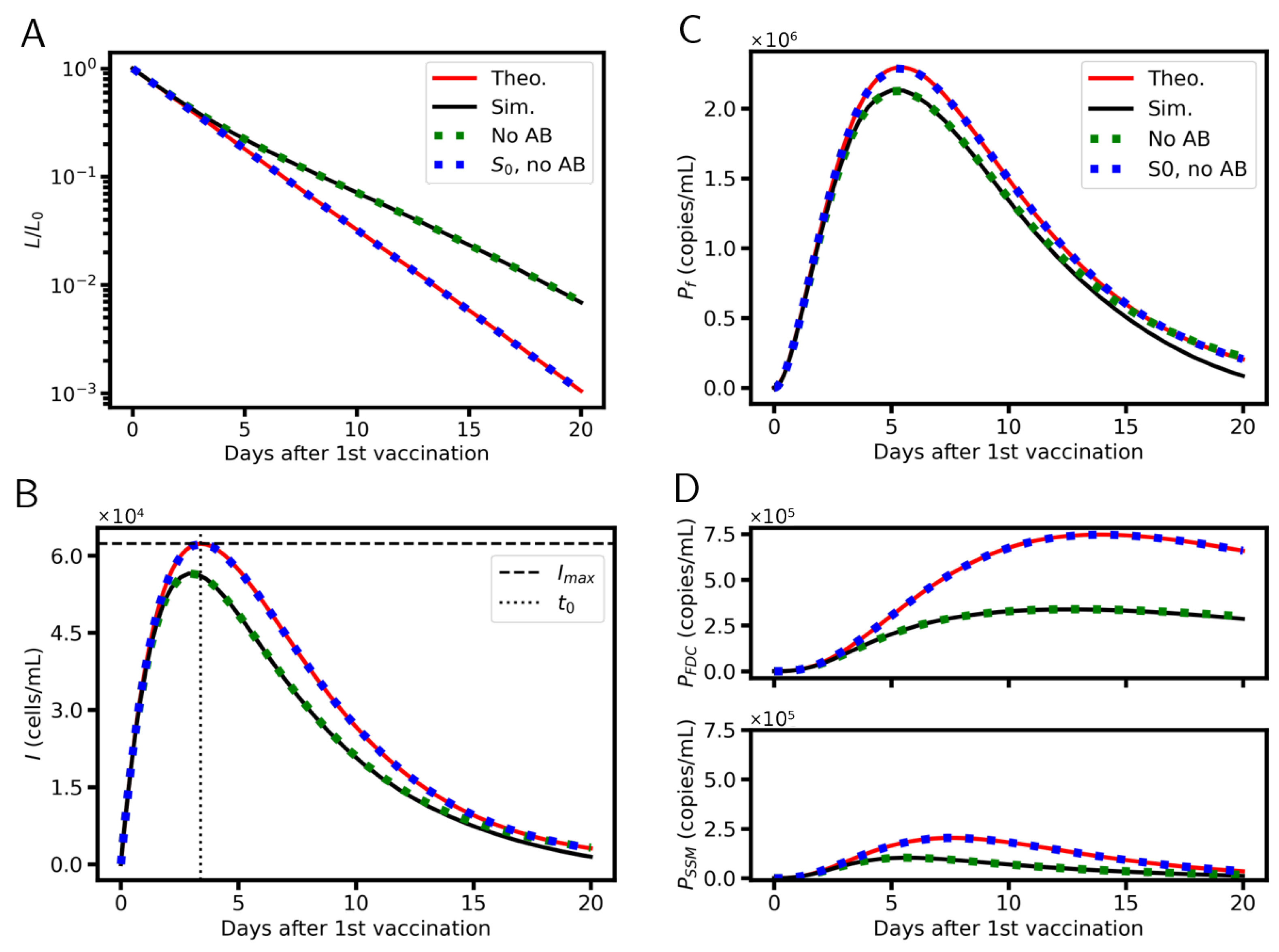

3.7. Analytical Solutions

4. Mathematical Formulation: Primary Response Model

4.1. Naïve B-Cell

4.2. Germinal Center B-Cells

4.3. Affinity Maturation

4.4. Specification

4.5. Memory B-Cells

4.6. Long-Living Plasma Cells

5. Mathematical Formulation: Secondary Response Model

5.1. Expanding Memory B-Cells

5.2. Short-Living Plasma Cells

5.3. Antibodies (A)

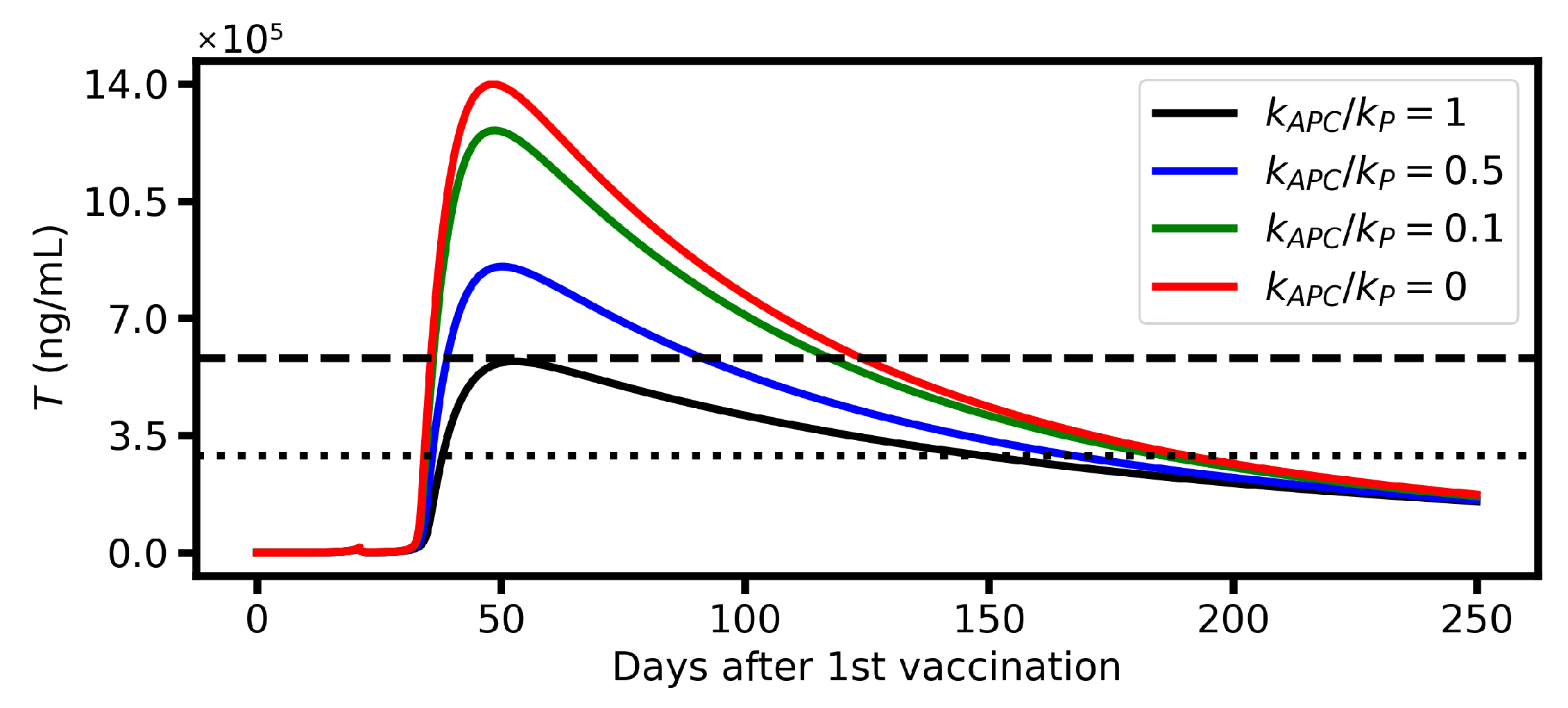

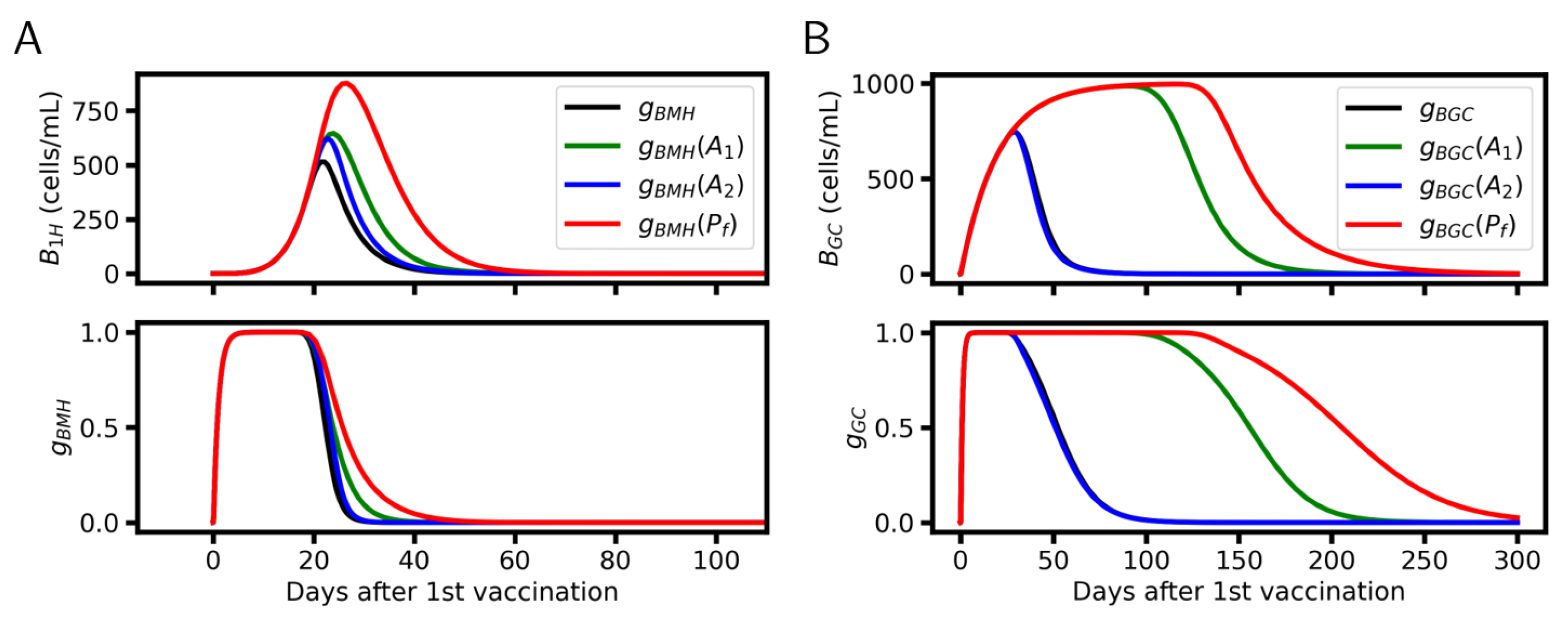

5.4. Antibody-Dependent Feedback on AM

6. Simulation Results

6.1. Systems Dynamics

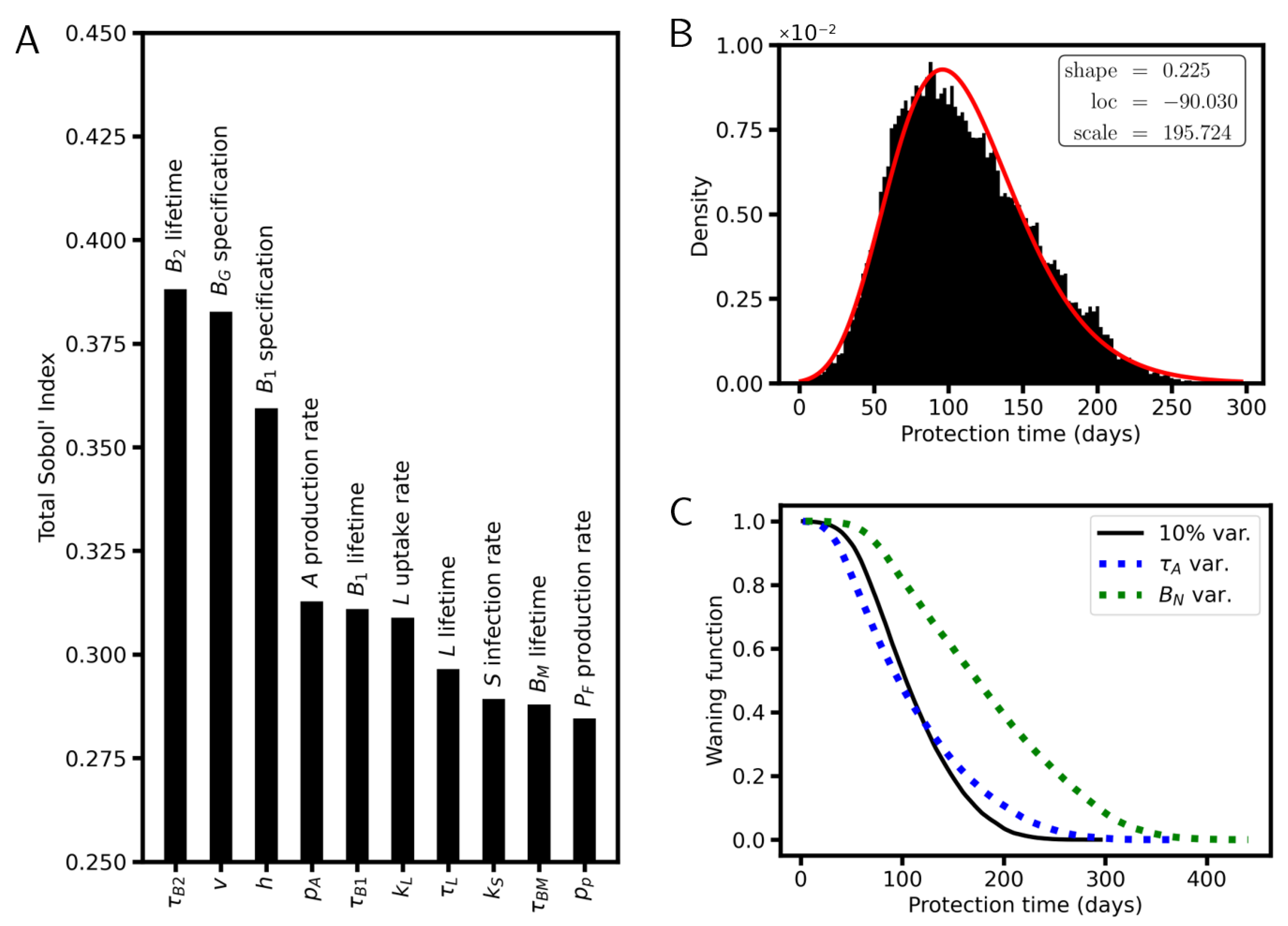

6.2. Protective Potential of Vaccination

6.3. Vaccination Timing

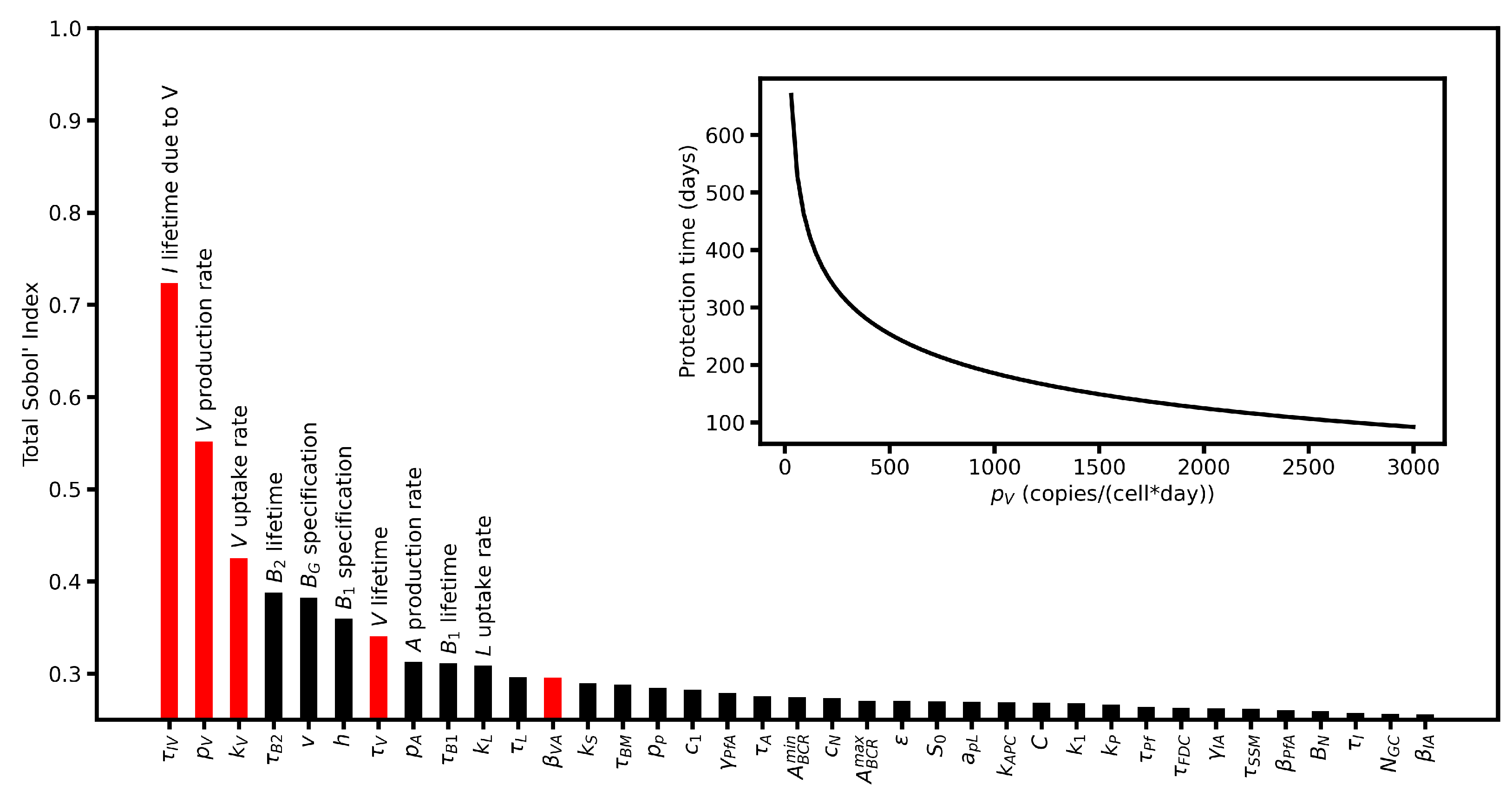

6.4. Sensitivity Analysis

7. Discussion

7.1. Mechanisms Responsible for Waning

7.2. Waning Immunity in Cohorts

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Analytical Solutions for the Vaccination Model

Appendix B. Details on Antibody Feedback

Appendix B.1. ADCC Experiment

Appendix B.2. Neutralization Experiment

Appendix C. Virus Infection Model

Appendix C.1. Susceptible Cells

Appendix C.2. Infected Cells

Appendix C.3. Virus

Appendix C.4. Analytical Solution for the Critical Titer Tc

Appendix D. Reference Parameter Sets

| Parameter | Description | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uptake rate of L | mL/day/cell | [19] | |

| Lifetime of L | 7 days | [19] | |

| Infection rate | mL/day/cell | [19] | |

| Lifetime of I | 4 days | [25] | |

| Recruitment rate of S | /day | Set | |

| S-pool density | cells/mL | [23] | |

| Protein production rate | 25 copies/day/cell | [28] | |

| Internalization rate of | mL/day/copy | See text | |

| Activation rate of APC | mL/day/copy | See text | |

| Lifetime of and | 2 days | [29] | |

| Lifetime of | 20 days | [32] |

| Parameter | Description | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| density | cells/mL | See text | |

| Number of productive GCs | 1 /mL | See text | |

| Maximum recruitment rate | /day | [33] | |

| GC apoptosis rate | 0.5/day | Set | |

| Rate of leaving GC | 0.05/day | [33] | |

| Minimum | 1 | Set | |

| Maximum | 30 | Set | |

| v | Fraction of to | 0.9 | Set |

| Maximum amplification rate | 0.6/day | [46] | |

| h | Fraction of to | 0.6 | Set |

| Lifetime of | 18 days | [42] | |

| Lifetime of | 5 days | [47] | |

| Lifetime of | 180 days | [45] | |

| Antibody production rate | 2 ng/day/cell | [50] | |

| Antibody lifetime | 60 days | [48,49] |

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| C | Scaling rate | 0.1 cells/copy |

| Cell destruction rate | mL/day/ng | |

| Neutralization rate | mL/day/ng | |

| Antibody consumption of I | ng/cell | |

| Antibody consumption of | ng/copy |

| Population | Initial Density |

|---|---|

| L | copies/mL [19] |

| S | |

| 0 | |

| 0 | |

| 0 |

| Parameter | Description | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell infection rate | mL/days/copy | Set | |

| Lifetime of infected cells | 0.5 days | [93] | |

| S-pool density | cells/mL | Set | |

| Virus internalization rate | mL/days/cell | Set | |

| Virus production rate | 2500 copies/day/cell | [93] | |

| Virus lifetime | 2 days | [95] |

References

- Lee, H.Y.; Topham, D.J.; Park, S.Y.; Hollenbaugh, J.; Treanor, J.; Mosmann, T.R.; Jin, X.; Ward, B.M.; Miao, H.; Holden-Wiltse, J.; et al. Simulation and Prediction of the Adaptive Immune Response to Influenza A Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 7151–7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molari, M.; Eyer, K.; Baudry, J.; Cocco, S.; Monasson, R. Quantitative modeling of the effect of antigen dosage on B-cell affinity distributions in maturating germinal centers. eLife 2020, 9, e55678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer-Hermann, M. A molecular theory of germinal center B cell selection and division. Cell Rep. 2021, 36, 109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, M.; Kwak, K.; Pierce, S.K. B cell memory: Building two walls of protection against pathogens. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 20, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, C.; Tokarev, A.; Bouchnita, A.; Volpert, V. Modelling of the Innate and Adaptive Immune Response to SARS Viral Infection, Cytokine Storm and Vaccination. Vaccines 2023, 11, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustin, T.; Harel, N.; Finkel, U.; Perchik, S.; Harari, S.; Tahor, M.; Caspi, I.; Levy, R.; Leshchinsky, M.; Ken Dror, S.; et al. Evidence for increased breakthrough rates of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in BNT162b2-mRNA-vaccinated individuals. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menegale, F.; Manica, M.; Zardini, A.; Guzzetta, G.; Marziano, V.; d’Andrea, V.; Trentini, F.; Ajelli, M.; Poletti, P.; Merler, S. Evaluation of Waning of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine–Induced Immunity: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2310650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicher, M.; Zuba, M.; Rainer, L.; Bachner, F.; Rippinger, C.; Ostermann, H.; Popper, N.; Thurner, S.; Klimek, P. Supporting COVID-19 policy-making with a predictive epidemiological multi-model warning system. Commun. Med. 2022, 2, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwamino, Y.; Nagashima, K.; Yoshifuji, A.; Suga, S.; Nagao, M.; Fujisawa, T.; Ryuzaki, M.; Takemoto, Y.; Namkoong, H.; Wakui, M.; et al. Estimating immunity with mathematical models for SARS-CoV-2 after COVID-19 vaccination. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, T.W.; Townsley, H.; Hellewell, J.; Gahir, J.; Shawe-Taylor, M.; Greenwood, D.; Hodgson, D.; Hobbs, A.; Dowgier, G.; Penn, R.; et al. Real-time estimation of immunological responses against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants in the UK: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, D.C.; Hentenaar, I.T.; Morrison-Porter, A.; Solano, D.; Haddad, N.S.; Castrillon, C.; Runnstrom, M.C.; Lamothe, P.A.; Andrews, J.; Roberts, D.; et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific plasma cells are not durably established in the bone marrow long-lived compartment after mRNA vaccination. Nat. Med. 2024, 31, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, I.; Nguyen, A.; Khoo, W.H.; Butt, D.; Bourne, K.; Young, C.; Hermes, J.R.; Biro, M.; Gracie, G.; Ma, C.S.; et al. Memory B cells are reactivated in subcapsular proliferative foci of lymph nodes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tellier, J.; Nutt, S.L. Plasma cells: The programming of an antibody-secreting machine. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018, 49, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, M.; Küppers, R. Human memory B cells. Leukemia 2016, 30, 2283–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulana, A.; Dupic, T.; Phillips, A.M.; Chang, J.; Roffler, A.A.; Greaney, A.J.; Starr, T.N.; Bloom, J.D.; Desai, M.M. The landscape of antibody binding affinity in SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 evolution. eLife 2023, 12, e83442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, K.J.; Rajlic, I.L.; Bahl, K.; White, R.; Cowens, K.; Jacquinet, E.; Burke, K.E. mRNA vaccine trafficking and resulting protein expression after intramuscular administration. Mol. Ther.-Nucleic Acids 2024, 35, 102083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, K.E.; Bhosle, S.M.; Zurla, C.; Beyersdorf, J.; Rogers, K.A.; Vanover, D.; Xiao, P.; Araínga, M.; Shirreff, L.M.; Pitard, B.; et al. Visualization of early events in mRNA vaccine delivery in non-human primates via PET–CT and near-infrared imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 3, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bepperling, A.; Richter, G. Determination of mRNA copy number in degradable lipid nanoparticles via density contrast analytical ultracentrifugation. Eur. Biophys. J. 2023, 52, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, S.J.; Li, S.; Amarasena, T.H.; Reynaldi, A.; Lee, W.S.; Leeming, M.G.; O’Connor, D.H.; Nguyen, J.; Kent, H.E.; Caruso, F.; et al. Blood Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Lipid Nanoparticle mRNA Vaccine in Humans. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 27077–27089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castruita, J.A.S.; Schneider, U.V.; Mollerup, S.; Leineweber, T.D.; Weis, N.; Bukh, J.; Pedersen, M.S.; Westh, H. SARS-CoV-2 spike mRNA vaccine sequences circulate in blood up to 28 days after COVID-19 vaccination. J. Pathol. Microbiol. Immunol. 2023, 131, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, W.S.; Chen, L.M.; Kroschewski, R.; Ebersold, M.; Turley, S.; Trombetta, S.; Galán, J.E.; Mellman, I. Developmental Control of Endocytosis in Dendritic Cells by Cdc42. Cell 2000, 102, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, P.; Franke, C.; Stöter, M.; Höijer, A.; Bartesaghi, S.; Sabirsh, A.; Lindfors, L.; Arteta, M.Y.; Dahlén, A.; Bak, A.; et al. Endosomal escape of delivered mRNA from endosomal recycling tubules visualized at the nanoscale. J. Cell Biol. 2021, 221, e202110137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sender, R.; Weiss, Y.; Navon, Y.; Milo, I.; Azulay, N.; Keren, L.; Fuchs, S.; Ben-Zvi, D.; Noor, E.; Milo, R. The total mass, number, and distribution of immune cells in the human body. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2308511120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winheim, E.; Rinke, L.; Lutz, K.; Reischer, A.; Leutbecher, A.; Wolfram, L.; Rausch, L.; Kranich, J.; Wratil, P.R.; Huber, J.E.; et al. Impaired function and delayed regeneration of dendritic cells in COVID-19. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalod, M.; Chelbi, R.; Malissen, B.; Lawrence, T. Dendritic cell maturation: Functional specialization through signaling specificity and transcriptional programming. EMBO J. 2014, 33, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heesters, B.A.; Chatterjee, P.; Kim, Y.A.; Gonzalez, S.F.; Kuligowski, M.P.; Kirchhausen, T.; Carroll, M.C. Endocytosis and Recycling of Immune Complexes by Follicular Dendritic Cells Enhances B Cell Antigen Binding and Activation. Immunity 2013, 38, 1164–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, A.F.; Cheng, C.A.; Desjardins, M.; Senussi, Y.; Sherman, A.C.; Powell, M.; Novack, L.; Von, S.; Li, X.; Baden, L.R.; et al. Circulating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Vaccine Antigen Detected in the Plasma of mRNA-1273 Vaccine Recipients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 74, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, W.J.; Branham, P.J.; Williamson, Y.M.; Cooper, H.C.; Najjar, F.N.; Pierce-Ruiz, C.L.; Barr, J.R.; Williams, T.L. Quantification of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein expression from mRNA vaccines using isotope dilution mass spectrometry. Vaccine 2023, 41, 3872–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cognetti, J.S.; Miller, B.L. Monitoring Serum Spike Protein with Disposable Photonic Biosensors Following SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination. Sensors 2021, 21, 5857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogna, C.; Cristoni, S.; Marino, G.; Montano, L.; Viduto, V.; Fabrowski, M.; Lettieri, G.; Piscopo, M. Detection of recombinant Spike protein in the blood of individuals vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2: Possible molecular mechanisms. Proteom. Clin. Appl. 2023, 17, 2300048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.K.; Leisching, G.R.; Snyders, C.I.; Gutschmidt, A.; van Rensburg, I.C.; Loxton, A.G. Immunoglobulin profile and B-cell frequencies are altered with changes in the cellular microenvironment independent of the stimulation conditions. Immunity, Inflamm. Dis. 2020, 8, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.S.; O’Halloran, J.A.; Kalaidina, E.; Kim, W.; Schmitz, A.J.; Zhou, J.Q.; Lei, T.; Thapa, M.; Chen, R.E.; Case, J.B.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines induce persistent human germinal centre responses. Nature 2021, 596, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, P.A.; Arulraj, T.; Meyer-Hermann, M. Germinal centers are permissive to subdominant antibody responses. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1238046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.T.; Gazumyan, A.; Kara, E.E.; Gitlin, A.D.; Golijanin, J.; Viant, C.; Pai, J.; Oliveira, T.Y.; Wang, Q.; Escolano, A.; et al. The microanatomic segregation of selection by apoptosis in the germinal center. Science 2017, 358, eaao2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.C.; Okada, T.; Tang, H.L.; Cyster, J.G. Imaging of Germinal Center Selection Events During Affinity Maturation. Science 2007, 315, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolin, D.H.; Helmuth Saunders, E.F.; Bronfin, B.; de Rosa, N.; Axthelm, M.K.; Alvarez, X.; Letvin, N.L. High Frequency of Virus-Specific B Lymphocytes in Germinal Centers of Simian-Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Rhesus Monkeys. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 3965–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schemel, C.M.; Wurzel, P.; Scharf, S.; Schäfer, H.; Hartmann, S.; Koch, I.; Hansmann, M.L. Three-dimensional human germinal centers of different sizes in patients diagnosed with lymphadenitis show comparative constant relative volumes of B cells, T cells, follicular dendritic cells, and macrophages. Acta Histochem. 2023, 125, 152075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wishnie, A.J.; Chwat-Edelstein, T.; Attaway, M.; Vuong, B.Q. BCR Affinity Influences T-B Interactions and B Cell Development in Secondary Lymphoid Organs. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 703918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broketa, M.; Sokal, A.; Mor, M.; Canales-Herrerias, P.; Perima, A.; Meola, A.; Fernández, I.; Iannascoli, B.; Chenon, G.; Vandenberghe, A.; et al. Qualitative monitoring of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in humans using droplet microfluidics. JCI Insight 2023, 8, e166602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirelli, K.M.; Crotty, S. Germinal center enhancement by extended antigen availability. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2017, 47, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisel, F.J.; Zuccarino-Catania, G.V.; Chikina, M.; Shlomchik, M.J. A Temporal Switch in the Germinal Center Determines Differential Output of Memory B and Plasma Cells. Immunity 2016, 44, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macallan, D.C.; Wallace, D.L.; Zhang, Y.; Ghattas, H.; Asquith, B.; de Lara, C.; Worth, A.; Panayiotakopoulos, G.; Griffin, G.E.; Tough, D.F.; et al. B-cell kinetics in humans: Rapid turnover of peripheral blood memory cells. Blood 2005, 105, 3633–3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.G.; Paus, D.; Chan, T.D.; Turner, M.L.; Nutt, S.L.; Basten, A.; Brink, R. High affinity germinal center B cells are actively selected into the plasma cell compartment. J. Exp. Med. 2006, 203, 2419–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, K.J.; Scharer, C.D. Roadmap to a plasma cell: Epigenetic and transcriptional cues that guide B cell differentiation. Immunol. Rev. 2020, 300, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, R.A.; Thiel, A.; Radbruch, A. Lifetime of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature 1997, 388, 133–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangye, S.G.; Avery, D.T.; Hodgkin, P.D. A Division-Linked Mechanism for the Rapid Generation of Ig-Secreting Cells from Human Memory B Cells. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, L.; Cheng, Q.; Radbruch, A.; Hiepe, F. The Maintenance of Memory Plasma Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, T.W.; Schulte-Pelkum, J.; Steller, L.; Filchtinski, D.; Jenness, R.; Williams, M.R.; Kober, C.; Manni, S.; Hauser, T.; Hahn, A.; et al. Determination of neutralising anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody half-life in COVID-19 convalescent donors. Clin. Immunol. 2021, 232, 108871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.S.; Phua, S.K.; Liang, Y.L.; Oh, M.L.H.; Aw, T.C. SARS-CoV-2 Spike and Neutralizing Antibody Kinetics 90 Days after Three Doses of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 Vaccine in Singapore. Vaccines 2022, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromage, E.; Stephens, R.; Hassoun, L. The third dimension of ELISPOTs: Quantifying antibody secretion from individual plasma cells. J. Immunol. Methods 2009, 346, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, M.; Castro, M.; Faro, J. B cell receptors and free antibodies have different antigen-binding kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2220669120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, A.; Nordenfelt, P. Protective non-neutralizing SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies. Trends Immunol. 2024, 45, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Meyer-Hermann, M.; George, L.A.; Figge, M.T.; Khan, M.; Goodall, M.; Young, S.P.; Reynolds, A.; Falciani, F.; Waisman, A.; et al. Germinal center B cells govern their own fate via antibody feedback. J. Exp. Med. 2013, 210, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney, J.; Yeh, C.; Kelsoe, G.; Kuraoka, M. Germinal center responses to complex antigens. Immunol. Rev. 2018, 284, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägglöf, T.; Cipolla, M.; Loewe, M.; Chen, S.T.; Kara, E.E.; Mesin, L.; Hartweger, H.; ElTanbouly, M.A.; Cho, A.; Gazumyan, A.; et al. Continuous germinal center invasion contributes to the diversity of the immune response. Cell 2023, 186, 147–161.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, R.V.; Ersching, J.; Barbulescu, A.; Hobbs, A.; Castro, T.B.; Mesin, L.; Jacobsen, J.T.; Phillips, B.K.; Hoffmann, H.H.; Parsa, R.; et al. Clonal replacement sustains long-lived germinal centers primed by respiratory viruses. Cell 2023, 186, 131–146.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.R.; Painter, M.M.; Apostolidis, S.A.; Mathew, D.; Meng, W.; Rosenfeld, A.M.; Lundgreen, K.A.; Reynaldi, A.; Khoury, D.S.; Pattekar, A.; et al. mRNA vaccines induce durable immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Science 2021, 374, abm0829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasca, D.; Diaz, A.; Romero, M.; Landin, A.M.; Blomberg, B.B. Age effects on B cells and humoral immunity in humans. Ageing Res. Rev. 2011, 10, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shioda, K.; Breskin, A.; Harati, P.; Chamberlain, A.T.; Komura, T.; Lopman, B.A.; Rogawski McQuade, E.T. Comparative effectiveness of alternative intervals between first and second doses of the mRNA COVID-19 vaccines. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menni, C.; May, A.; Polidori, L.; Louca, P.; Wolf, J.; Capdevila, J.; Hu, C.; Ourselin, S.; Steves, C.J.; Valdes, A.M.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine waning and effectiveness and side-effects of boosters: A prospective community study from the ZOE COVID Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 1002–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanishi, E.; Levy, O.; Ozonoff, A. Waning effectiveness of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in older adults: A rapid review. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2045857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Beltran, W.F.; St. Denis, K.J.; Hoelzemer, A.; Lam, E.C.; Nitido, A.D.; Sheehan, M.L.; Berrios, C.; Ofoman, O.; Chang, C.C.; Hauser, B.M.; et al. mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine boosters induce neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Cell 2022, 185, 457–466.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobol’, I. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Math. Comput. Simul. 2001, 55, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Dhingra, R.; Gambhir, M.; Remais, J.V. Sensitivity analysis of infectious disease models: Methods, advances and their application. J. R. Soc. Interface 2013, 10, 20121018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paludan, S.R.; Pradeu, T.; Pichlmair, A.; Wray, K.B.; Mikkelsen, J.G.; Olagnier, D.; Mogensen, T.H. Early host defense against virus infections. Cell Rep. 2024, 43, 115070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Termote, M.; Marques, R.C.; Hyllner, E.; Guryleva, M.V.; Henskens, M.; Brutscher, A.; Baken, I.J.; Dopico, X.C.; Gasull, A.D.; Murrell, B.; et al. Antigen affinity and site of immunization dictate B cell recall responses. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 115221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Garcia-Ibanez, L.; Ulbricht, C.; Lok, L.S.C.; Pike, J.A.; Mueller-Winkler, J.; Dennison, T.W.; Ferdinand, J.R.; Burnett, C.J.M.; Yam-Puc, J.C.; et al. Recycling of memory B cells between germinal center and lymph node subcapsular sinus supports affinity maturation to antigenic drift. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fair-Mäkelä, R.; Thorén, P.; Näsiaho, J.; Sundqvist, P.; Piiroinen, I.; Kähäri, L.; Julkunen, I.; Ivaska, J.; Hub, E.; Rot, A.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine type controls stromal reprogramming in draining lymph nodes. Sci. Immunol. 2025, 10, eadr6787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidlaw, B.J.; Ellebedy, A.H. The germinal centre B cell response to SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 22, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulroney, T.E.; Pöyry, T.; Yam-Puc, J.C.; Rust, M.; Harvey, R.F.; Kalmar, L.; Horner, E.; Booth, L.; Ferreira, A.P.; Stoneley, M.; et al. N1-methylpseudouridylation of mRNA causes +1 ribosomal frameshifting. Nature 2023, 625, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Rostad, C.A.; Anderson, L.J.; Sun, H.y.; Lapp, S.A.; Stephens, K.; Hussaini, L.; Gibson, T.; Rouphael, N.; Anderson, E.J. The development and kinetics of functional antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Virology 2021, 559, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sun, J.; Li, F.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; Wu, G.; Guan, J.; Zhu, J.; et al. OP0221 LBL-047, A novel afucosylated anti-BDCA2/TACI fusion protein with YTE mutation inhibiths the functiouns of both pDCs and B cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2024, 83, 17–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, K.L.; Mylvaganam, G.; Villasmil-Ocando, A.; Stuart, H.; Maus, M.V.; Rashidian, M.; Ploegh, H.L.; Walker, B.D. HIV-infected macrophages resist efficient NK cell-mediated killing while preserving inflammatory cytokine responses. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 435–447.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajnik, R.L.; Plante, J.A.; Liang, Y.; Alameh, M.G.; Tang, J.; Bonam, S.R.; Zhong, C.; Adam, A.; Scharton, D.; Rafael, G.H.; et al. Dual spike and nucleocapsid mRNA vaccination confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron and Delta variants in preclinical models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabq1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kachko, A.; Selvaraj, P.; Rotstein, D.; Stauft, C.B.; Rajasagi, N.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, T.; Major, M. Combined immunization with SARS-CoV-2 spike and SARS-CoV nucleocapsid protects K18-hACE2 mice but increases lung pathology. npj Vaccines 2025, 10, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, K.; Esmaeili, S.; Schiffer, J.T. Heterogeneous SARS-CoV-2 kinetics due to variable timing and intensity of immune responses. JCI Insight 2024, 9, e176286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Vulesevic, B.; Vigano, M.; As’sadiq, A.; Kang, K.; Fernandez, C.; Samarani, S.; Anis, A.H.; Ahmad, A.; Costiniuk, C.T. The Impact of HIV on B Cell Compartment and Its Implications for COVID-19 Vaccinations in People with HIV. Vaccines 2024, 12, 1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moir, S.; Buckner, C.M.; Ho, J.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Waldner, A.J.; Posada, J.G.; Kardava, L.; O’Shea, M.A.; Kottilil, S.; et al. B cells in early and chronic HIV infection: Evidence for preservation of immune function associated with early initiation of antiretroviral therapy. Blood 2010, 116, 5571–5579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, D.W.; Pai Mangalore, R.; Hoy, J.F.; McMahon, J.H. Immunogenicity, effectiveness, and safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in people with HIV. AIDS 2023, 37, 1345–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, K.A.; Ings, D.P.; Harnum, D.O.A.; Russell, R.S.; Grant, M.D. Moderate to severe SARS-CoV-2 infection primes vaccine-induced immunity more effectively than asymptomatic or mild infection. npj Vaccines 2022, 7, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Pandey, A.; Bawden, C.; Sumsuzzman, D.M.; Rajput, R.; Shoukat, A.; Singer, B.H.; Moghadas, S.M.; Galvani, A.P. Integrating artificial intelligence with mechanistic epidemiological modeling: A scoping review of opportunities and challenges. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, O.O. The immunopathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Overview of lessons learned in the first 5 years. J. Immunol. 2025, 214, 1095–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, A.; Pollard, A.J.; Davis, M.M. Systems Immunology: Revealing Influenza Immunological Imprint. Viruses 2021, 13, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, M.D.; Heyer, L.N.; Williams, D.E.J.; Harvey, J.D.; Greenough, T.; Allhorn, M.; Evans, D.T. A Novel Assay for Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity against HIV-1- or SIV-Infected Cells Reveals Incomplete Overlap with Antibodies Measured by Neutralization and Binding Assays. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 12039–12052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, G.; Ciric, C.; Gibson, T.; Anderson, L.J.; Rostad, C.A. Fc-effector functional antibody assays for SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1571835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordi, L.; Piralla, A.; Lalle, E.; Giardina, F.; Colavita, F.; Tallarita, M.; Sberna, G.; Novazzi, F.; Meschi, S.; Castilletti, C.; et al. Rapid and sensitive detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA using the Simplexa™ COVID-19 direct assay. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 128, 104416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compans, R.W.; Herrler, G. Virus Infection of Epithelial Cells. In Mucosal Immunology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 769–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Wang, X.; Ho, W.Z. Roles of Macrophages in Viral Infections. Viruses 2024, 16, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raach, B.; Bundgaard, N.; Haase, M.J.; Starruß, J.; Sotillo, R.; Stanifer, M.L.; Graw, F. Influence of cell type specific infectivity and tissue composition on SARS-CoV-2 infection dynamics within human airway epithelium. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2023, 19, e1011356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.S.; Ejima, K.; Iwanami, S.; Fujita, Y.; Ohashi, H.; Koizumi, Y.; Asai, Y.; Nakaoka, S.; Watashi, K.; Aihara, K.; et al. A quantitative model used to compare within-host SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV dynamics provides insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of SARS-CoV-2. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, N.G.; Alfajaro, M.M.; Gasque, V.; Huston, N.C.; Wan, H.; Szigeti-Buck, K.; Yasumoto, Y.; Greaney, A.M.; Habet, V.; Chow, R.D.; et al. Single-cell longitudinal analysis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in human airway epithelium identifies target cells, alterations in gene expression, and cell state changes. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainu, F.; Shiratsuchi, A.; Nakanishi, Y. Induction of Apoptosis and Subsequent Phagocytosis of Virus-Infected Cells As an Antiviral Mechanism. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timm, A.; Yin, J. Kinetics of virus production from single cells. Virology 2012, 424, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapuy-Regaud, S.; Allioux, C.; Capelli, N.; Migueres, M.; Lhomme, S.; Izopet, J. Vectorial Release of Human RNA Viruses from Epithelial Cells. Viruses 2022, 14, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guang, Y.; Hui, L. Determining half-life of SARS-CoV-2 antigen in respiratory secretion. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 69697–69702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magalang, J.; Krueger, T.; Galle, J. Modelling the Variability in Immunity Build-Up and Waning Following RNA-Based Vaccination. Viruses 2025, 17, 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121643

Magalang J, Krueger T, Galle J. Modelling the Variability in Immunity Build-Up and Waning Following RNA-Based Vaccination. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121643

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagalang, Juan, Tyll Krueger, and Joerg Galle. 2025. "Modelling the Variability in Immunity Build-Up and Waning Following RNA-Based Vaccination" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121643

APA StyleMagalang, J., Krueger, T., & Galle, J. (2025). Modelling the Variability in Immunity Build-Up and Waning Following RNA-Based Vaccination. Viruses, 17(12), 1643. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121643