Phylogeographic and Host Interface Analyses Reveal the Evolutionary Dynamics of SAT3 Foot-And-Mouth Disease Virus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Sequence Dataset Preparation

2.2. Sequence Alignment and Recombination Screening

2.3. Saturation and Phylogenetic Signal Testing

2.4. Phylogenetic Reconstruction and Clade Assignment

2.5. Genetic Distance Analysis

2.6. Temporal Signal and Molecular Clock Estimation

2.7. Spatiotemporal Spread and Host Transition Analyses

2.8. Selection Pressure and Co-Evolutionary Signal Analysis

3. Results

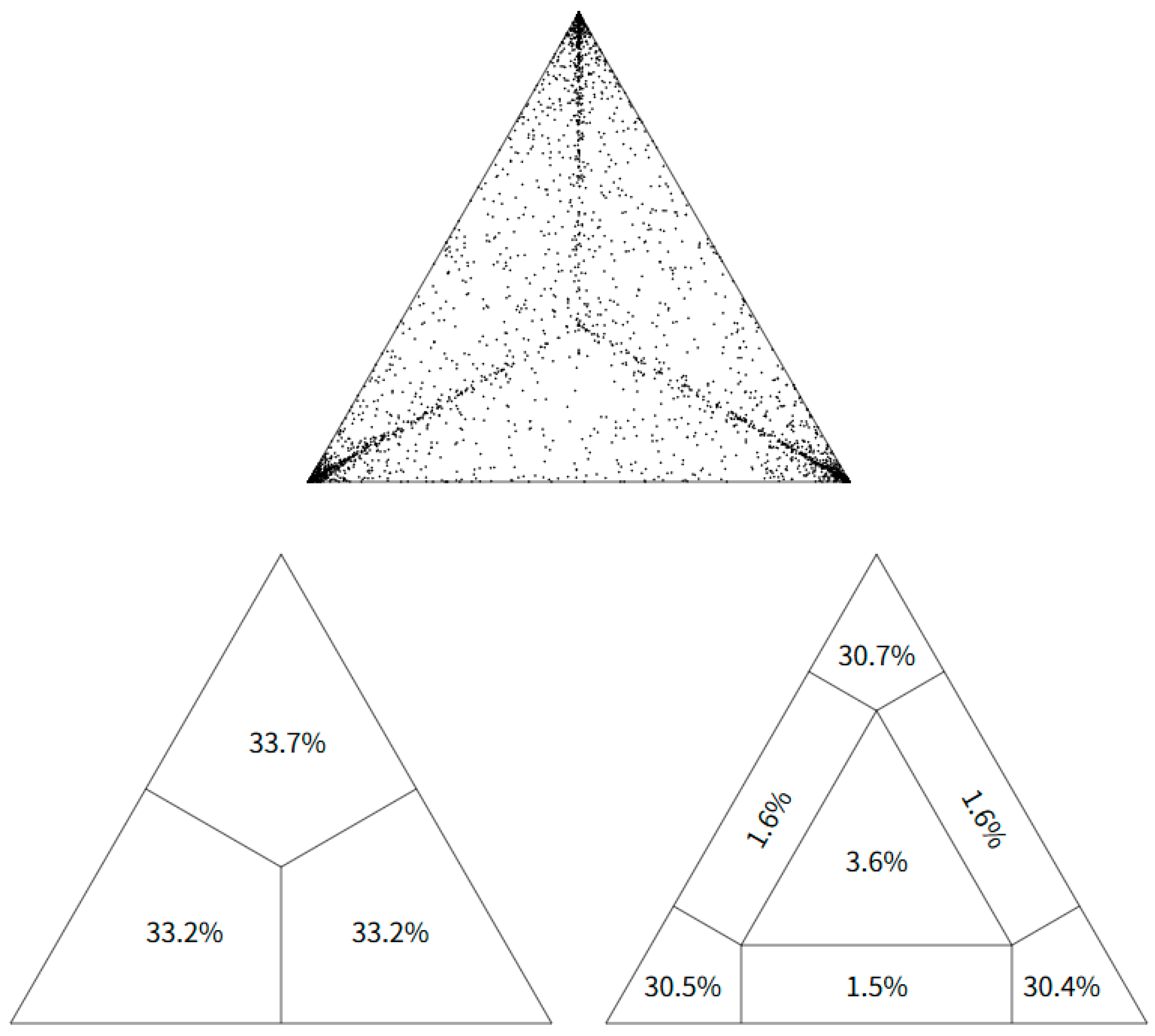

3.1. Likelihood Mapping and Phylogenetic Analysis

3.2. Demographic and Temporal Analysis

3.3. Geographic Dispersal Analysis

3.4. Host-Associated Transmission Analysis

3.5. Selection Pressure and Co-Evolutionary Signals

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chase-Topping, M.E.; Handel, I.; Bankowski, B.M.; Juleff, N.D.; Gibson, D.; Cox, S.J.; Windsor, M.A.; Reid, E.; Doel, C.; Howey, R.; et al. Understanding foot-and-mouth disease virus transmission biology: Identification of the indicators of infectiousness. Vet. Res. 2013, 44, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockcroft, P.D. Bovine Medicine; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Zell, R.; Delwart, E.; Gorbalenya, A.E.; Hovi, T.; King, A.M.Q.; Knowles, N.J.; Lindberg, A.M.; Pallansch, M.A.; Palmenberg, A.C.; Reuter, G.; et al. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Picornaviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2017, 98, 2421–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knowles, N.J.; Samuel, A.R. Molecular epidemiology of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Virus Res. 2003, 91, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rweyemamu, M.; Roeder, P.; Mackay, D.; Sumption, K.; Brownlie, J.; Leforban, Y.; Valarcher, J.F.; Knowles, N.J.; Saraiva, V. Epidemiological patterns of foot-and-mouth disease worldwide. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2008, 55, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knight-Jones, T.J.D.; Rushton, J. The economic impacts of foot and mouth disease–What are they, how big are they and where do they occur? Prev. Vet. Med. 2013, 112, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooksby, J.B. The virus of foot-and-mouth disease. Adv. Virus Res. 1958, 5, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, F. The history of research in foot-and-mouth disease. Virus Res. 2003, 91, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maake, L.; Harvey, W.T.; Rotherham, L.; Opperman, P.; Theron, J.; Reeve, R.; Maree, F.F. Genetic Basis of Antigenic Variation of SAT3 Foot-And-Mouth Disease Viruses in Southern Africa. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyason, E. Summary of foot-and-mouth disease outbreaks reported in and around the Kruger National Park, South Africa, between 1970 and 2009. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2010, 81, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, A.D.; Boshoff, C.I.; Keet, D.F.; Bengis, R.G.; Thomson, G.R. Natural transmission of foot-and-mouth disease virus between African buffalo (Syncerus caffer) and impala (Aepyceros melampus) in the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Epidemiol. Infect. 2000, 124, 591–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, B.P.; Jori, F.; Dwarka, R.; Maree, F.F.; Heath, L.; Perez, A.M. Transmission of Foot-and-Mouth Disease SAT2 Viruses at the Wildlife-Livestock Interface of Two Major Transfrontier Conservation Areas in Southern Africa. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, P.W.; Grubman, M.J.; Baxt, B. Molecular basis of pathogenesis of FMDV. Virus Res. 2003, 91, 9–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belsham, G.J. Distinctive features of foot-and-mouth disease virus, a member of the picornavirus family; aspects of virus protein synthesis, protein processing and structure. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1993, 60, 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachanek-Bankowska, K.; Di Nardo, A.; Wadsworth, J.; Mioulet, V.; Pezzoni, G.; Grazioli, S.; Brocchi, E.; Kafle, S.C.; Hettiarachchi, R.; Kumarawadu, P.L.; et al. Reconstructing the evolutionary history of pandemic foot-and-mouth disease viruses: The impact of recombination within the emerging O/ME-SA/Ind-2001 lineage. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, V.P.; Vu, T.T.; Duong, H.Q.; Than, V.T.; Song, D. Evolutionary phylodynamics of foot-and-mouth disease virus serotypes O and A circulating in Vietnam. BMC Vet. Res. 2016, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangula, A.K.; Belsham, G.J.; Muwanika, V.B.; Heller, R.; Balinda, S.N.; Masembe, C.; Siegismund, H.R. Evolutionary analysis of foot-and-mouth disease virus serotype SAT 1 isolates from east Africa suggests two independent introductions from southern Africa. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010, 10, 371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015, 1, vev003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X. DAMBE7: New and Improved Tools for Data Analysis in Molecular Biology and Evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1550–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S.; Minh, B.Q.; Wong, T.K.F.; von Haeseler, A.; Jermiin, L.S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.A.; Strimmer, K.; Vingron, M.; von Haeseler, A. TREE-PUZZLE: Maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis using quartets and parallel computing. Bioinformatics 2002, 18, 502–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Tamura, K. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 7.0 for Bigger Datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Susko, E.; Inagaki, Y.; Roger, A.J. On inconsistency of the neighbor-joining, least squares, and minimum evolution estimation when substitution processes are incorrectly modeled. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004, 21, 1629–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Lam, T.T.; Max Carvalho, L.; Pybus, O.G. Exploring the temporal structure of heterochronous sequences using TempEst (formerly Path-O-Gen). Virus Evol. 2016, 2, vew007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchard, M.A.; Lemey, P.; Baele, G.; Ayres, D.L.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vey016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Zwickl, D.J.; Beerli, P.; Holder, M.T.; Lewis, P.O.; Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F.; Swofford, D.L.; Cummings, M.P.; et al. BEAGLE: An application programming interface and high-performance computing library for statistical phylogenetics. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Lewis, P.O.; Fan, Y.; Kuo, L.; Chen, M.H. Improving marginal likelihood estimation for Bayesian phylogenetic model selection. Syst. Biol. 2011, 60, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourment, M.; Magee, A.F.; Whidden, C.; Bilge, A.; Matsen, F.A.; Minin, V.N. 19 Dubious Ways to Compute the Marginal Likelihood of a Phylogenetic Tree Topology. Syst. Biol. 2020, 69, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambaut, A.; Drummond, A.J.; Xie, D.; Baele, G.; Suchard, M.A.; Susko, E. Posterior Summarization in Bayesian Phylogenetics Using Tracer 1.7. Syst. Biol. 2018, 67, 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahata, K.D.; Bielejec, F.; Monetta, J.; Dellicour, S.; Rambaut, A.; Suchard, M.A.; Baele, G.; Lemey, P. SPREAD 4: Online visualisation of pathogen phylogeographic reconstructions. Virus Evol. 2022, 8, veac088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delport, W.; Poon, A.F.; Frost, S.D.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L. Datamonkey 2010: A suite of phylogenetic analysis tools for evolutionary biology. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 2455–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Frost, S.D.W. Not So Different After All: A Comparison of Methods for Detecting Amino Acid Sites Under Selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005, 22, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murrell, B.; Moola, S.; Mabona, A.; Weighill, T.; Sheward, D.; Kosakovsky Pond, S.L.; Scheffler, K. FUBAR: A Fast, Unconstrained Bayesian AppRoximation for Inferring Selection. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, G.M.; Ho, C.H.; Chiang, M.J.; Sanno-Duanda, B.; Chung, C.S.; Lin, M.Y.; Shi, Y.Y.; Yang, M.H.; Tyan, Y.C.; Liao, P.C.; et al. Phylodynamic analysis of the canine distemper virus hemagglutinin gene. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastos, A.D.; Anderson, E.C.; Bengis, R.G.; Keet, D.F.; Winterbach, H.K.; Thomson, G.R. Molecular epidemiology of SAT3-type foot-and-mouth disease. Virus Genes 2003, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosloo, W.; Boshoff, K.; Dwarka, R.; Bastos, A. The possible role that buffalo played in the recent outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease in South Africa. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 969, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasecka-Dykes, L.; Wright, C.F.; Di Nardo, A.; Logan, G.; Mioulet, V.; Jackson, T.; Tuthill, T.J.; Knowles, N.J.; King, D.P. Full Genome Sequencing Reveals New Southern African Territories Genotypes Bringing Us Closer to Understanding True Variability of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus in Africa. Viruses 2018, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, M.D.; Knowles, N.J.; Wadsworth, J.; Rambaut, A.; Woolhouse, M.E. Reconstructing geographical movements and host species transitions of foot-and-mouth disease virus serotype SAT 2. mBio 2013, 4, e00591-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lycett, S.; Tanya, V.N.; Hall, M.; King, D.P.; Mazeri, S.; Mioulet, V.; Knowles, N.J.; Wadsworth, J.; Bachanek-Bankowska, K.; Ngu Ngwa, V.; et al. The evolution and phylodynamics of serotype A and SAT2 foot-and-mouth disease viruses in endemic regions of Africa. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, G.R. Overview of foot and mouth disease in southern Africa. Rev. Sci. Tech. 1995, 14, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey-Bryars, M.; Reeve, R.; Bastola, U.; Knowles, N.J.; Auty, H.; Bachanek-Bankowska, K.; Fowler, V.L.; Fyumagwa, R.; Kazwala, R.; Kibona, T.; et al. Waves of endemic foot-and-mouth disease in eastern Africa suggest feasibility of proactive vaccination approaches. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 2, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bronsvoort, B.M.; Radford, A.D.; Tanya, V.N.; Nfon, C.; Kitching, R.P.; Morgan, K.L. Molecular epidemiology of foot-and-mouth disease viruses in the Adamawa province of Cameroon. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 2186–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calkins, C.M.; Scasta, J.D. Transboundary Animal Diseases (TADs) affecting domestic and wild African ungulates: African swine fever, foot and mouth disease, Rift Valley fever (1996–2018). Res. Vet. Sci. 2020, 131, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omondi, G.P.; Gakuya, F.; Arzt, J.; Sangula, A.; Hartwig, E.; Pauszek, S.; Smoliga, G.; Brito, B.; Perez, A.; Obanda, V.; et al. The role of African buffalo in the epidemiology of foot-and-mouth disease in sympatric cattle and buffalo populations in Kenya. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2020, 67, 2206–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillian, S. African Buffalo persistently exposed to contagious foot and mouth diseases. Nat. Afr. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosloo, W.; Swanepoel, S.P.; Bauman, M.; Botha, B.; Esterhuysen, J.J.; Boshoff, C.I.; Keet, D.F.; Dekker, A. Experimental infection of giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) with SAT-1 and SAT-2 foot-and-mouth disease virus. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2011, 58, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdar, M.M.; Fosgate, G.T.; Blignaut, B.; Mampane, L.R.; Rikhotso, O.B.; Du Plessis, B.; Gummow, B. Spatial distribution of foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreaks in South Africa (2005–2016). Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jori, F.; Etter, E. Transmission of foot and mouth disease at the wildlife/livestock interface of the Kruger National Park, South Africa: Can the risk be mitigated? Prev. Vet. Med. 2016, 126, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastroeni, P.; Grant, A.; Restif, O.; Maskell, D. A dynamic view of the spread and intracellular distribution of Salmonella enterica. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vosloo, W.; Thompson, P.N.; Botha, B.; Bengis, R.G.; Thomson, G.R. Longitudinal study to investigate the role of impala (Aepyceros melampus) in foot-and-mouth disease maintenance in the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2009, 56, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashinagu, M.M.; Wambura, P.N.; King, D.P.; Paton, D.J.; Maree, F.; Kimera, S.I.; Rweyemamu, M.M.; Kasanga, C.J.; Samrat, S. Challenges of Controlling Foot-and-Mouth Disease in Pastoral Settings in Africa. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2024, 2024, 2700985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramaniam, S.; Mohapatra, J.K.; Sharma, G.K.; Das, B.; Dash, B.B.; Sanyal, A.; Pattnaik, B. Phylogeny and genetic diversity of foot and mouth disease virus serotype Asia1 in India during 1964–2012. Vet. Microbiol. 2013, 167, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahiya, S.S.; Subramaniam, S.; Mohapatra, J.K.; Rout, M.; Biswal, J.K.; Giri, P.; Nayak, V.; Singh, R.P. Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus Serotype O Exhibits Phenomenal Genetic Lineage Diversity in India during 2018–2022. Viruses 2023, 15, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ularamu, H.G.; Ibu, J.O.; Wood, B.A.; Abenga, J.N.; Lazarus, D.D.; Wungak, Y.S.; Knowles, N.J.; Wadsworth, J.; Mioulet, V.; King, D.P.; et al. Characterization of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Viruses Collected in Nigeria Between 2007 and 2014: Evidence for Epidemiological Links Between West and East Africa. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2017, 64, 1867–1876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T.; King, A.M.; Stuart, D.I.; Fry, E. Structure and receptor binding. Virus Res. 2003, 91, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haydon, D.T.; Bastos, A.D.; Knowles, N.J.; Samuel, A.R. Evidence for positive selection in foot-and-mouth disease virus capsid genes from field isolates. Genetics 2001, 157, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, M.A.; Dopazo, J.; Hernandez, J.; Mateu, M.G.; Sobrino, F.; Domingo, E.; Knowles, N.J. Evolution of the capsid protein genes of foot-and-mouth disease virus: Antigenic variation without accumulation of amino acid substitutions over six decades. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 3557–3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, C.; Tulman, E.R.; Delhon, G.; Lu, Z.; Carreno, A.; Vagnozzi, A.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. Comparative genomics of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 6487–6504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, D.C.; Fares, M.A. Unravelling Selection Shifts among Foot-and-Mouth Disease virus (FMDV) Serotypes. Evol. Bioinform. 2006, 2, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, D.C.; Fares, M.A. Shifts in the selection-drift balance drive the evolution and epidemiology of foot-and-mouth disease virus. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, D.; Abu-Ghazaleh, R.; Blakemore, W.; Curry, S.; Jackson, T.; King, A.; Lea, S.; Lewis, R.; Newman, J.; Parry, N.; et al. Structure of a major immunogenic site on foot-and-mouth disease virus. Nature 1993, 362, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, R.; Fry, E.; Stuart, D.; Fox, G.; Rowlands, D.; Brown, F. The three-dimensional structure of foot-and-mouth disease virus at 2.9 A resolution. Nature 1989, 337, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topotype | Country | Host | Number of Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | South Africa, Zimbabwe | African buffalo, Cattle | 34 |

| II | Zimbabwe, Botswana, Zambia | African buffalo, Cattle | 16 |

| III | Zimbabwe; Malawi | African buffalo Cattle | 21 |

| IV | Zambia | African buffalo | 3 |

| V | Uganda | African buffalo | 3 |

| VI | Zimbabwe | African buffalo | 1 |

| VII | Mozambique | African buffalo | 3 |

| From | To | Rate Mean (/Year) (ESS) | Bayes Factor | Posterior | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle Bos taurus | African buffalo Syncerus caffer | 0.871 (9001) | 0.034 | 0.16 | No (BF < 3) |

| African buffalo Syncerus caffer | Cattle Bos taurus | 1.08 (9001) | 1631.09 | 1 | Yes (BF > 3) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Lv, J.; Lin, Y.; Chai, R.; Liang, J.; Su, Y.; Tian, Z.; Guo, H.; Chen, F.; Ni, G.; et al. Phylogeographic and Host Interface Analyses Reveal the Evolutionary Dynamics of SAT3 Foot-And-Mouth Disease Virus. Viruses 2025, 17, 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121641

Zhang S, Lv J, Lin Y, Chai R, Liang J, Su Y, Tian Z, Guo H, Chen F, Ni G, et al. Phylogeographic and Host Interface Analyses Reveal the Evolutionary Dynamics of SAT3 Foot-And-Mouth Disease Virus. Viruses. 2025; 17(12):1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121641

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shuang, Jianing Lv, Yao Lin, Rong Chai, Jiaxi Liang, Yan Su, Zhuo Tian, Hanyu Guo, Fuyun Chen, Guanying Ni, and et al. 2025. "Phylogeographic and Host Interface Analyses Reveal the Evolutionary Dynamics of SAT3 Foot-And-Mouth Disease Virus" Viruses 17, no. 12: 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121641

APA StyleZhang, S., Lv, J., Lin, Y., Chai, R., Liang, J., Su, Y., Tian, Z., Guo, H., Chen, F., Ni, G., Wang, G., Song, C., Li, B., Wang, Q., Zhao, S., Huang, Q., Ji, X., Duo, J., Bai, F., ... Wang, X. (2025). Phylogeographic and Host Interface Analyses Reveal the Evolutionary Dynamics of SAT3 Foot-And-Mouth Disease Virus. Viruses, 17(12), 1641. https://doi.org/10.3390/v17121641