Abstract

As viruses have a capacity to rapidly evolve and continually alter the coding of their protein repertoires, host cells have evolved pathways to sense viruses through the one invariable feature common to all these pathogens—their nucleic acids. These genomic and transcriptional pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) trigger the activation of germline-encoded anti-viral pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that can distinguish viral nucleic acids from host forms by their localization and subtle differences in their chemistry. A wide range of transmembrane and cytosolic PRRs continually probe the intracellular environment for these viral PAMPs, activating pathways leading to the activation of anti-viral gene expression. The activation of Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NFκB) and Interferon (IFN) Regulatory Factor (IRF) family transcription factors are of central importance in driving pro-inflammatory and type-I interferon (TI-IFN) gene expression required to effectively restrict spread and trigger adaptive responses leading to clearance. Poxviruses evolve complex arrays of inhibitors which target these pathways at a variety of levels. This review will focus on how poxviruses target and inhibit PRR pathways leading to the activation of IRF family transcription factors.

1. Introduction

Germline-encoded pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) ‘sense’ infection by binding invariable chemical features of invading pathogens called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Each PRR activates signal transduction pathways leading to gene expression, which orchestrates clearance of the specific type of pathogen from which the PAMP was derived. The principle PAMPs of viruses are their nucleic acids, which are distinguished from native host nucleic acids by cellular location and subtle differences in chemistry [1]. In order to evade or suppress anti-viral immunity, viruses invariably evolve targeted strategies to prevent activation of these sensing systems at a variety of points along the pathway to sensing-induced gene expression. Anti-viral PRRs typically drive expression of type I interferons (TI-IFNs) and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin−1 (IL−1) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF), which heavily rely on the activity of IFN Regulatory Factor (IRF) and Nuclear Factor Kappa B (NFκB) family transcription factors. The induction of TI-IFNs requires the combined activity of NFκB and IRFs [2,3], whilst the regulation of pro-inflammatory genes has a stronger reliance on NFκB activity [4].

Poxviruses comprise a diverse family of large, enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses. Their genomes range between 134 and 365 kb, which are spatially organized into central, relatively conserved regions which typically encode everything required for basic life cycle functions and diverse terminal regions with a higher degree of genetic plasticity where immunomodulatory proteins tend to be encoded. Approximately 130 to 328 open reading frames (ORFs) are bidirectionally encoded throughout their genomes [5,6]. Poxviruses broadly group into two subfamilies: Chordopoxvirinae, which infect vertebrates, and Entomopoxvirinae, which infect invertebrates. Chordopoxvirinae subdivide into ten genera: orthopoxviruses, leporipoxviruses, yatapoxviruses, parapoxviruses, cervidpoxviruses, capripoxviruses, suipoxviruses, molluscipoxviruses, crocodylipoxviruses and avipoxviruses. They can be also grouped into four phylogenetic categories by order of divergence [7]. Group I is the most divergent and includes the Avipoxvirus genera with Fowlpox (FPV) and Canarypox viruses. Group II, the next most divergent, includes Molluscipoxvirus with Molluscum Contagiosum virus (MCV) and Parapoxvirus (PPV) genera. The remaining two groups, III and IV, are closely clustered together, often being referred to as ‘sister groups’ based on the relative proximity of their phylogenetic grouping. Group III comprises members of Capripoxvirus, Leporipoxvirus, such as myxoma virus (MYXV), Suipoxvirus and Yatapoxvirus genera and Group IV includes the seven members of the Orthopoxvirus genera, such as camelpoxvirus (CMPV), variola virus (VARV), vaccinia virus (VACV), monkeypox virus (MPV), ectromelia virus (ECTV) and cowpox virus (CPV) which are arguably the best characterized of the poxviruses.

Poxviruses have well-characterized immunoevasive and immunomodulatory strategies to suppress activation of the host innate immune system, seeking to sense them in order to drive effector responses leading to their clearance [8]. These strategies target signaling pathways at a variety of points in activation, with a preference for targeting downstream at common points of convergence in the activation of NFκB and IRF family transcription factors. These transcription factors collaborate in transactivating a wide range of target genes, but the NFκB family bias towards pro-inflammatory gene regulation and the IRF family towards interferon gene induction. By inhibiting activation of both these transcription factors with both discrete and multi-functional inhibitors, poxviruses can delay or silence pro-inflammatory and interference responses, depending on how efficiently targeting evolves to be.

Poxviruses appear to have a larger number of dedicated inhibitors focused on the inhibition of NFκB-activating pathways [8] but less dedicated IRF-targeting inhibitors have been discovered thus far. This could suggest that (a) IRF signaling is easier to inhibit with less targeting inhibitors, (b) the requirement for NFκB in TI-IFN regulation makes dedicating inhibitors to IRFs less important or (c) that inhibiting inflammation is a higher priority for these viruses. Poxviral inhibitors of NFκB activation have been covered at length in other reviews [8,9]. In this review, we will discuss the strategies that poxviruses have evolved to target pathways leading to the activation of IRF-family transcription factors, with a focus on preventing the induction of TI-IFNs.

4. Inhibition of IRF Activation by Cytosolic Nucleic Acid Sensors by Poxviruses

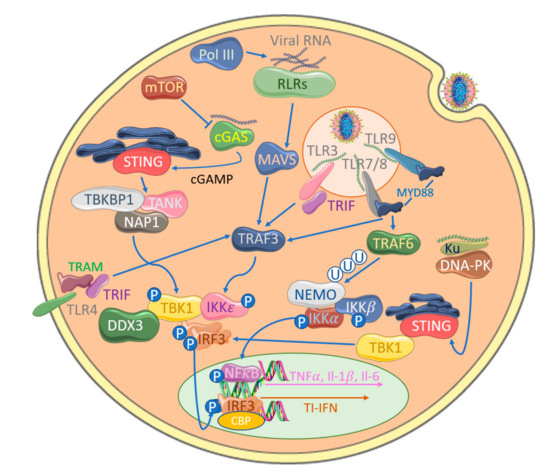

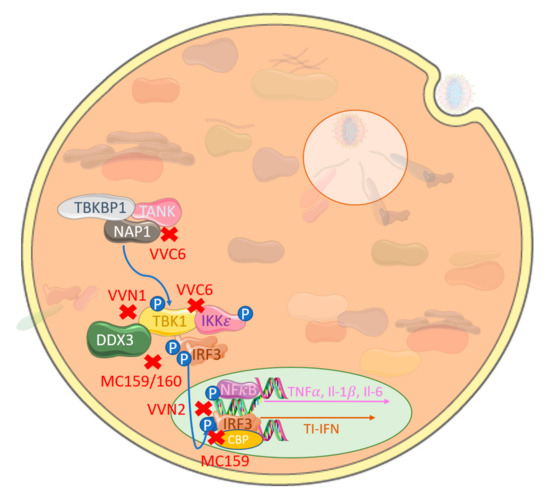

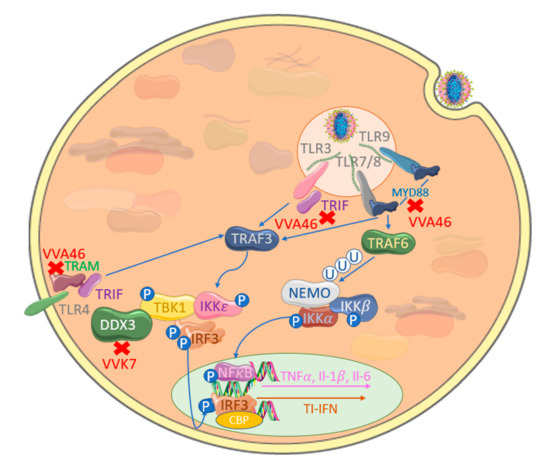

Despite the ability of TLRs to sense poxvirus infection, the attenuated modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA), which possesses several of the previously described inhibitors, still induces TI-IFNs in a TLR-independent fashion [97]. Consistent with this, a range of additional cytosolic PRRs can detect both poxviral RNA and DNA. The cytosolic RNA receptors melanoma differentiation factor 5 (MDA5) and retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG-I) detect long dsRNA and dsRNA with a 5′ triphosphate group, respectively, in the cytoplasm of cells infected with RNA viruses [98]. Upon activation, these RLRs engage the adaptor protein MAVS, resulting in TBK1-induced IRF3 phosphorylation through TBK1 and IKKε [37] (Figure 4). Several reports demonstrate how poxviruses are also sensed by RLRs. For example, MYXV stimulates IRF-dependent TI-IFN production in primary human macrophages through RIG-I [99], while VACV induces TI-IFN in a RIG-I- and MDA5-dependent manner in different cell types and MVA-induced IFNβ and IFN-dependent chemokines via MDA5 and MAVS but not RIG-I in macrophages, suggesting both virus and cell type differences in these responses [100,101,102]. A third RLR, LGP−2, has also been shown to be important for the IRF3 activation and upregulation of IRF3-dependant genes in response to VACV DNA [103]. MVA infection also causes increased cellular expression of the RLRs, thus increasing the sensitivity of DCs to aberrant RNA [104].

Figure 4.

Poxviral inhibition of cytosolic nucleic acid sensing leading to IRF activation. VACV-encoded E3 (VVE3) binds dsDNA acting as a competitive inhibitor of RLR activation. Similarly, VACV-encoded C4 and C16 (VVC4/C16) inhibit DNA binding to Ku, therefore blocking DNA-PK-mediated stimulator of interferon genes (STING) activation and, hence, TBK1 activation. The VACV-encoded poxin B2 (VVB2) hydrolyses the 3′−5′ bond on cGAMP, thus inactivating this key messenger molecule in cGAS-STING activation. A further target is mTOR-dependent cGAS degradation by VACV-encoded F17 (VVF17), thus suppressing cGAS-mediated TI-IFN gene expression.

The importance of RLRs in managing poxviral infection is reflected in the fact that there is evidence that poxviral infection has played a role in positive selection of RLR families in different mammalian species over time [105]. A rationale for how cytosolic dsRNA PRRs are involved in detecting poxviruses is provided by the fact that poxviruses generate large quantities of dsRNA during an infection. Although poxviral genomes are organized to cluster ORFs that express in the same direction, simultaneous transcription of both strands to generate complementary dsRNA can still occur [106]. To counter this, VACV E3, which binds dsRNA, was shown to block RLR-driven IRF3 activation in keratinocytes with E3-deleted virus, displaying increased levels of IRF3 phosphorylation [107] (Figure 4). The requirement for RLRs in anti-viral responses to poxviruses also involves the RNA polymerase III intermediate system of cytosolic DNA detection, whereby RNA polymerase III transcribes short RNA sequences from cytosolic AT-rich DNA that are direct ligands for RIG-I activation [108,109]. Interestingly, E3 can also antagonize this system [110].

Although the physiological relevance of AT-rich dsDNA-sensing by RNA polymerase III in poxviral infections is unclear, additional cytosolic DNA sensors play a central role in the potency of cytosolic DNA, whether from viral infection or from aberrant host DNA localization, to drive IRF activation and induce TI-IFNs [111]. Such DNA sensors, in many cases, strongly activate IRF3 via a well-defined STING-TBK1-IRF3 signaling axis (Figure 1), whereas the DNA-sensing cytosolic pathways to NFkB activation are still less clear. Both genetic and biochemical studies have demonstrated the importance of STING in signaling a response to DNA viruses in the cytoplasm, though how STING itself is activated by upstream DNA sensors was initially unclear [112]. A series of elegant studies then showed that cyclic-GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthase (cGAS) is a DNA sensor upstream of STING, whose enzyme activity is stimulated by direct binding of DNA, leading to production of the novel second messenger cGAMP (reviewed in [113]). cGAMP is a direct ligand for STING, which is initially localized in the endoplasmic reticulum, but on binding, it translocates to TBK1-containing membrane-bound compartments, leading to IRF3 activation. Interestingly, after infection of cells with MVA, cGAMP can diffuse through cellular gap junctions to activate the TI-IFN response in adjacent, uninfected cells, implying that the cGAS-STING system may directly stimulate bystander cells for resistance to incoming poxviral infection [114,115]. The cGAS-STING system was also shown to sense MVA DNA in the cytoplasm of conventional DCs during infection [116]. A number of papers have demonstrated that TI-IFN induction by VACV in some cell types requires cGAS [115,116].

We have recently reviewed DNA virus inhibitors of the cGAS-STING pathway, including those of poxviruses [117]. In addition to the poxviral inhibitors that target at the level of the IRF activation or IRF activity, which inhibit this system by default, a recently discovered family of poxvirus immune nucleases (poxins) were discovered in a screen for cGAS inhibitors. The authors described how VACV B2 protein degrades cGAMP by hydrolyzing the canonical 3′–5′ bond (Figure 4) and significantly reducing IFNβ production [118]. Additionally, a component of poxviral lateral bodies expressed late in infection, F17, specifically modulates the cGAS-STING pathway to interfere with IRF-induced TI-IFN production. Targeting mTOR-dependent cGAS degradation [119] by this conserved poxvirus gene highlights precise targeting of a key viral cytosolic sensing modulatory pathway. Of interest, its late gene expression has a further target in facilitating viral protein synthesis through mTOR dysregulation [120].

Cytosolic DNA-sensing pathways outside of cGAS-STING signaling are poorly defined, but multi-layered immune defense mechanisms for every PAMP are common. A cytosolic DNA-sensing mechanism in fibroblasts has been shown to be targeted by poxviruses for immune evasion; Ferguson et al. [121] showed that DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) senses MVA, leading to STING-dependent IRF3 activation, and DNA-PK associates with a heterodimer of Ku70 and Ku80 and is a serine/threonine protein kinase. Primarily associated with DNA damage repair, specifically double-stranded breaks, it is an emergent potential therapeutic target to enhance the success of cancer treatment [122]. However, it has also surfaced as a key component in initializing the innate immune response to viral DNA. Recently identified in humans, DNA-PK binds cytosolic DNA and acts in a STING-independent manner [123]. This pathway is antagonized by VACV through two distinct proteins, highlighting complementary multi-layered viral immune evasion mechanisms. VACV-encoded C16 is able to bind to the Ku heterodimer through its C-terminal region to block DNA binding [124] (Figure 4). A second VACV Ku-binding protein with sequence homology, C4, additionally stops DNA binding, quelling cytokine release [125]. The presence of multiple proteins targeting the same pathways directs our understanding further into these complex interactions.

Given the importance of these cytosolic sensing systems pathways for detecting poxviruses to drive TI-IFNs, as their pathways are further elaborated, along with new components and mechanisms that regulate them, we expect that additional as-yet undiscovered poxviral inhibitors that target them will also be identified.

5. Concluding Remarks

The induction of TI-IFNs by nucleic acid sensors is a critical feature of the response to poxviruses and indeed all viruses with differences in pathways employed, depending on the nature of the nucleic acids presented to the innate immune system during infection. These pathways have a rate-limiting reliance on IRF-family activation. Once secreted, TI-IFNs then drive IFN-stimulated gene expression in surrounding cells to induce the interference state, making uninfected cells non-permissive for the incoming virus. This IFN system aims to quarantine the virus and limit replication whilst assisting the emergence of a robust adaptive response needed for clearance. Consequently, poxviruses evolve highly efficient and, in some cases, multifunctional inhibitors which target IRF-activating pathways at multiple levels in order to prevent TI-IFN production, which would limit its spread. The extent to which they achieve this underlies the delicate balance between persistence, invasiveness and pathology that defines their presentation in disease.

Author Contributions

Both authors contributed equally to the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Science Foundation Ireland grant number 19/FFP/6848 - 210295-16377. No competing financial interest exists.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Science Foundation Ireland for funding this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| PAMP | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| PRR | Pattern Recognition Receptors |

| NFκB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| IFN | Interferon |

| IRF | Interferon Regulatory Factor |

| TI-IFN | Type 1 Interferon |

| Il−1 | Interleukin 1 |

| TNF | Tumor Necrosis Factor |

| FPV | Fowlpox |

| MCV | Molluscum Contagiosum Virus |

| PPV | Parapoxvirus |

| MYXV | Myxoma Virus |

| CMPV | Camelpoxvirus |

| VARV | Variola Virus |

| VACV | Vaccinia Virus |

| MPV | Monkey Pox Virus |

| ECTV | Ectromelia Virus |

| CPV | Cowpox Virus |

| CPV | Cowpox Virus |

| TLR | Toll-Like Receptors |

| IKK | I KappaB Kinase |

| TBK1 | TANK binding kinase 1 |

| CBP | CREB Binding Protein |

| NEMO | Nuclear Factor Kappa B essential modulator |

| TRAF | TNF Receptor Associated Factors |

| NAP1 | Nuclear Factor Kappa B Activating Protein |

| FLIPS | viral FLICE Inhibitory Proteins |

| STING | stimulator of interferon genes |

| TIR | Toll Il−1R |

| TRIF | TIR-domain-containing adapter-inducing interferon-β |

| MyD88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 |

| MAL | MyD88-adapter-like |

| TRAM | TRIF-related adapter molecule |

| MDA5 | melanoma differentiation factor 5 |

| RIG−1 | retinoic acid-inducible gene |

| RLR | retinoic acid-inducible gene-I-like receptors |

| MAVS | Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling Protein |

| GAS | cyclic GMP AMP Synthase |

| GAMP | cyclic GMP-AMP |

| DNA-PK | DNA-dependent protein kinase |

References

- Lee, H.C.; Chathuranga, K.; Lee, J.S. Intracellular sensing of viral genomes and viral evasion. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.K.; Maniatis, T. The mechanism of transcriptional synergy of an in vitro assembled interferon-beta enhanceosome. Mol. Cell. 1997, 1, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marie, I.; Durbin, J.E.; Levy, D.E. Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-alpha genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor. EMBO J. 1998, 17, 6660–6669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, T. The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a001651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tulman, E.R.; Afonso, C.L.; Lu, Z.; Zsak, L.; Kutish, G.F.; Rock, D.L. The genome of canarypox virus. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, C.R.; Amano, H.; Ueda, Y.; Qin, J.; Miyamura, T.; Suzuki, T.; Li, X.; Barrett, J.W.; McFadden, G. Complete genomic sequence and comparative analysis of the tumorigenic poxvirus Yaba monkey tumor virus. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 13335–13347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, K.; Deng, R.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Huang, M.; Wang, X. Genome-based phylogeny of poxvirus. Intervirology 2006, 49, 207–214. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, G.; Bowie, A.G. Innate immune activation of NFkappaB and its antagonism by poxviruses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2014, 25, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, M.; Cheng, A.; Jia, R.; Chen, S.; Zhu, D.; Liu, M.; Yang, Q.; Wu, Y.; et al. Suppression of NF-kappaB Activity: A Viral Immune Evasion Mechanism. Viruses 2018, 10, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamane, Y.; Heylbroeck, C.; Génin, P.; Algarté, M.; Servant, M.J.; Lepage, C.; DeLuca, C.; Kwon, H.; Lin, R.; Hiscott, J.; et al. Interferon regulatory factors: The next generation. Gene 1999, 237, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, T.; Yanai, H.; Savitsky, D.; Taniguchi, T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 26, 535–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, T.; Ogasawara, K.; Takaoka, A.; Tanaka, N. IRF family of transcription factors as regulators of host defense. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2001, 19, 623–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nehyba, J.; Hrdličková, R.; Burnside, J.; Bose, H.R. A novel interferon regulatory factor (IRF), IRF-10, has a unique role in immune defense and is induced by the v-Rel oncoprotein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 3942–3957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darnell, J.E., Jr.; Kerr, I.M.; Stark, G.R. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science 1994, 264, 1415–14521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honda, K.; Takaoka, A.; Taniguchi, T. Type I interferon [corrected] gene induction by the interferon regulatory factor family of transcription factors. Immunity 2006, 25, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Au, W.C.; Moore, P.A.; LaFleur, D.W.; Tombal, B.; Pitha, P.M. Characterization of the interferon regulatory factor-7 and its potential role in the transcription activation of interferon A genes. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273, 29210–29217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgerald, K.A.; McWhirter, S.M.; Faia, L.M.; Rowe, D.C.; Latz, E.; Golenbock, D.T.; Coyle, A.J.; Liao, S.-M.; Maniatis, T. IKKepsilon and TBK1 are essential components of the IRF3 signaling pathway. Nat. Immunol. 2003, 4, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McWhirter, S.M.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Rosains, J.; Rowe, D.C.; Golenbock, D.T.; Maniatis, T. IFN-regulatory factor 3-dependent gene expression is defective in Tbk1-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Tenoever, B.R.; Grandvaux, N.; Zhou, G.-P.; Lin, R.; Hiscott, J. Triggering the interferon antiviral response through an IKK-related pathway. Science 2003, 300, 1148–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, H.; Chiba, S.; Hangai, S.; Kometani, K.; Inoue, A.; Kimura, Y.; Abe, T.; Kiyonari, H.; Nishio, J.; Taguchi-Atarashi, N.; et al. Revisiting the role of IRF3 in inflammation and immunity by conditional and specifically targeted gene ablation in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5253–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, M.; Yoneyama, M.; Ito, T.; Takahashi, K.; Inagaki, F.; Fujita, T. Identification of Ser-386 of interferon regulatory factor 3 as critical target for inducible phosphorylation that determines activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 9698–9702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panne, D.; McWhirter, S.M.; Maniatis, T.; Harrison, S.C. Interferon regulatory factor 3 is regulated by a dual phosphorylation-dependent switch. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 22816–22822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, B.Y.; Liu, C.; Lam, S.S.; Srinath, H.; Delston, R.; Correia, J.J.; Derynck, R.; Lin, K. Crystal structure of IRF-3 reveals mechanism of autoinhibition and virus-induced phosphoactivation. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003, 10, 913–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahasi, K.; Suzuki, N.N.; Horiuchi, M.; Mori, M.; Suhara, W.; Okabe, Y.; Fukuhara, Y.; Terasawa, H.; Akira, S.; Fujita, T.; et al. X-ray crystal structure of IRF-3 and its functional implications. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2003, 10, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, A. The IKK complex, a central regulator of NF-kappaB activation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol. 2010, 2, a000158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pomerantz, J.L.; Baltimore, D. NF-kappaB activation by a signaling complex containing TRAF2, TANK and TBK1, a novel IKK-related kinase. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 6694–6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnard, M.; Mirtsos, C.; Suzuki, S.; Graham, K.; Huang, J.; Ng, M.; Itié, A.; Wakeham, A.; Shahinian, A.; Henzel, W.J.; et al. Deficiency of T2K leads to apoptotic liver degeneration and impaired NF-kappaB-dependent gene transcription. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4976–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, D.; Yeh, W.C.; Wakeham, A.; Nallainathan, D.; Potter, J.; Elia, A.J.; Mak, T.W. Severe liver degeneration and lack of NF-kappaB activation in NEMO/IKKgamma-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 854–862. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Van Antwerp, D.; Mercurio, F.; Lee, K.F.; Verma, I.M. Severe liver degeneration in mice lacking the IkappaB kinase 2 gene. Science 1999, 28, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.W.; Chu, W.; Hu, Y.; Deerinck, T.; Ellisman, M.; Johnson, R.; Karin, M. The IKKbeta subunit of IkappaB kinase (IKK) is essential for nuclear factor kappaB activation and prevention of apoptosis. J. Exp. Med. 1999, 189, 1839–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; Fuente, M.E.; Yamaguchi, K.; Dalrymple, S.A.; Hardy, K.L.; Goeddel, D.V. Embryonic lethality, liver degeneration, and impaired NF-kappa B activation in IKK-beta-deficient mice. Immunity 1999, 10, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, T.; Kawai, T.; Takeda, K.; Matsumoto, M.; Inoue, J.; Tatsumi, Y.; Kanamaru, A.; Akira, S. IKK-i, a novel lipopolysaccharide-inducible kinase that is related to IkappaB kinases. Int. Immunol. 1999, 11, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmi, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Sato, S.; Yamamoto, M.; Tsuneyasu, K.; Sanjo, H.; Kawai, T.; Hoshino, K.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S. The roles of two IkappaB kinase-related kinases in lipopolysaccharide and double stranded RNA signaling and viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 199, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.; Plater, L.; Peggie, M.; Cohen, P. Use of the pharmacological inhibitor BX795 to study the regulation and physiological roles of TBK1 and IkappaB kinase epsilon: A distinct upstream kinase mediates Ser-172 phosphorylation and activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 14136–14146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.K.; Chow, E.K.; Goodnough, J.B.; Yeh, W.-C.; Cheng, G. Differential requirement for TANK-binding kinase-1 in type I interferon responses to toll-like receptor activation and viral infection. J. Exp. Med. 2004, 199, 1651–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balka, K.R.; Louis, C.; Saunders, T.L.; Smith, A.M.; Calleja, D.J.; D’Silva, D.B.; Moghaddas, F.; Tailler, M.; Lawlor, K.E.; Zhan, Y.; et al. TBK1 and IKKepsilon Act Redundantly to Mediate STING-Induced NF-kappaB Responses in Myeloid Cells. Cell. Rep. 2020, 31, 107492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; Guan, Y.; Tao, J.; Xi, J.; Feng, J.-M.; Jiang, Z. MAVS activates TBK1 and IKKepsilon through TRAFs in NEMO dependent and independent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Cheng, G. TRAF3: A new regulator of type I interferons. Cell Cycle 2006, 5, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Pietras, E.M.; He, J.Q.; Kang, J.R.; Liu, S.-Y.; Oganesyan, G.; Shahangian, A.; Zarnegar, B.; Shiba, T.L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Regulation of antiviral responses by a direct and specific interaction between TRAF3 and Cardif. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 3257–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.H.; Matsuzawa, A.; Zhang, W.; Mino, T.; Vignali, D.A.A.; Karin, M. Different modes of ubiquitination of the adaptor TRAF3 selectively activate the expression of type I interferons and proinflammatory cytokines. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Jin, J.; Zhu, L.; Jie, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhao, B.; Cheng, X.; Li, P.; Sun, S.-C. Cell type-specific function of TRAF2 and TRAF3 in regulating type I IFN induction. Cell Biosci. 2019, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.; Zhong, B. Regulation of cellular innate antiviral signaling by ubiquitin modification. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2015, 47, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Xu, M.; Liu, S.; Sun, L.; Chen, Z.J. Key Role of Ubc5 and Lysine-63 Polyubiquitination in Viral Activation of IRF3. Mol. Cell 2009, 36, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, S.; Hesson, L.; Peggie, M.; Cohen, P. Enhanced binding of TBK1 by an optineurin mutant that causes a familial form of primary open angle glaucoma. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 997–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, F.; Taniguchi, Y.; Kato, T.; Narita, Y.; Furuya, A.; Ogawa, T.; Sakurai, H.; Joh, T.; Itoh, M.; Delhase, M.; et al. Identification of NAP1, a regulatory subunit of IkappaB kinase-related kinases that potentiates NF-kappaB signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 7780–7793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryzhakov, G.; Randow, F. SINTBAD, a novel component of innate antiviral immunity, shares a TBK1-binding domain with NAP1 and TANK. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 3180–3190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chariot, A.; Leonardi, A.; Müller, J.; Bonif, M.; Brown, K.; Siebenlist, U. Association of the Adaptor TANK with the IκB Kinase (IKK) Regulator NEMO Connects IKK Complexes with IKKε and TBK1 Kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 37029–37036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Yang, L.; Sun, Q.; Arguello, M.; Ballard, D.W.; Hiscott, J.; Lin, R. The NEMO adaptor bridges the nuclear factor-kappaB and interferon regulatory factor signaling pathways. Nat. Immunol. 2007, 8, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.; Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S.; Cohen, P. The TRAF-associated protein TANK facilitates cross-talk within the IkappaB kinase family during Toll-like receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 17093–17098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.; Xiao, Y.; Chang, J.-H.; Yu, J.; Hu, H.; Starr, R.; Brittain, G.C.; Chang, M.; Cheng, X.; Sun, S.-C. The kinase TBK1 controls IgA class switching by negatively regulating noncanonical NF-kappaB signaling. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 13, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoyagi, M.; Zhai, D.; Jin, C.; Aleshin, A.E.; Stec, B.; Reed, J.C.; Liddington, R.C. Vaccinia virus N1L protein resembles a B cell lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) family protein. Protein Sci. 2006, 16, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiPerna, G.; Stack, J.; Bowie, A.G.; Boyd, A.; Kotwal, G.; Zhang, Z.; Arvikar, S.; Latz, E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Marshall, W.L. Poxvirus protein N1L targets the I-kappaB kinase complex, inhibits signaling to NF-kappaB by the tumor necrosis factor superfamily of receptors, and inhibits NF-kappaB and IRF3 signaling by toll-like receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 36570–36578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterholzner, L.; Sumner, R.P.; Baran, M.; Ren, H.; Mansur, D.S.; Bourke, N.M.; Randow, F.; Smith, G.L.; Bowie, A.G. Vaccinia Virus Protein C6 Is a Virulence Factor that Binds TBK-1 Adaptor Proteins and Inhibits Activation of IRF3 and IRF7. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, J.H.; Sumner, R.P.; Lu, Y.; Snowden, J.S.; Smith, G.L. Vaccinia Virus Protein C6 Inhibits Type I IFN Signalling in the Nucleus and Binds to the Transactivation Domain of STAT2. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soday, L.; Lu, Y.; Albarnaz, J.D.; Davies, C.; Antrobus, R.; Smith, G.L.; Weekes, M.P. Quantitative Temporal Proteomic Analysis of Vaccinia Virus Infection Reveals Regulation of Histone Deacetylases by an Interferon Antagonist. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 1920–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza-Romero, R.; Navarrete-Dechent, C.; Downey, C. Molluscum contagiosum: An update and review of new perspectives in etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2019, 12, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Anstey, A.V.; Bugert, J.J. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 877–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.B.; Shisler, J.L. The MC160 Protein Expressed by the Dermatotropic Poxvirus Molluscum Contagiosum Virus Prevents Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha-Induced NF-κB Activation via Inhibition of I Kappa Kinase Complex Formation. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, C.M.; Jokela, J.A.; Shisler, J.L. The MC159 protein from the molluscum contagiosum poxvirus inhibits NF-kappaB activation by interacting with the IkappaB kinase complex. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shisler, J.L. Viral and Cellular FLICE-Inhibitory Proteins: A Comparison of Their Roles in Regulating Intrinsic Immune Responses. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 6539–6541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Randall, C.M.; Biswas, S.; Selen, C.V.; Shisler, J.L. Inhibition of interferon gene activation by death-effector domain-containing proteins from the molluscum contagiosum virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 111, E265–E272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gates, L.T.; Shisler, J.L. cFLIPL Interrupts IRF3-CBP-DNA Interactions to Inhibit IRF3-Driven Transcription. J. Immunol. 2016, 197, 923–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, B.J.; Benfield, C.T.O.; Ren, H.; Lee, V.H.; Frazer, G.L.; Strnadova, P.; Sumner, R.P.; Smith, G.L. Vaccinia virus protein N2 is a nuclear IRF3 inhibitor that promotes virulence. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 2070–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sparrer, K.M.J.; Pfaller, C.K.; Conzelmann, K.-K. Measles Virus C Protein Interferes with Beta Interferon Transcription in the Nucleus. J. Virol. 2011, 86, 796–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, M.L.; Cardenas, W.B.; Zamarin, D.; Palese, P.; Basler, C.F. Nuclear Localization of the Nipah Virus W Protein Allows for Inhibition of both Virus- and Toll-Like Receptor 3-Triggered Signaling Pathways. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 6078–6088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, L.A.; Golenbock, D.; Bowie, A.G. The history of Toll-like receptors—A redefining innate immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 453–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leifer, C.A.; Medvedev, A.E. Molecular mechanisms of regulation of Toll-like receptor signaling. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2016, 100, 927–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, M.; Luker, K.E.; Sottile, P.; Sonstein, J.; Lukacs, N.W.; Núñez, G.; Curtis, J.L.; Luker, G.D. TLR3 Increases Disease Morbidity and Mortality from Vaccinia Infection. J. Immunol. 2007, 180, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchens, M.A.; Luker, K.E.; Sonstein, J.; Núñez, G.; Curtis, J.L.; Luker, G.D. Protective Effect of Toll-like Receptor 4 in Pulmonary Vaccinia Infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurt-Jones, E.A.; Popova, L.; Kwinn, L.; Haynes, L.M.; Jones, L.P.; Tripp, R.A.; Walsh, E.E.; Freeman, M.W.; Golenbock, D.T.; Anderson, L.J.; et al. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat. Immunol. 2000, 1, 398–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgel, P.; Jiang, Z.; Kunz, S.; Janssen, E.M.; Mols, J.; Hoebe, K.; Bahram, S.; Oldstone, M.B.; Beutler, B. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein G activates a specific antiviral Toll-like receptor 4-dependent pathway. Virology 2007, 362, 304–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirey, K.A.; Lai, W.; Scott, A.J.; Lipsky, M.; Mistry, P.; Pletneva, L.M.; Karp, C.L.; McAlees, J.W.; Gioannini, T.L.; Weiss, J.; et al. The TLR4 antagonist Eritoran protects mice from lethal influenza infection. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 497, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gorman, W.E.; Sampath, P.; Simonds, E.F.; Sikorski, R.; O’Malley, M.; Krutzik, P.O.; Chen, H.; Panchanathan, V.; Chaudhri, G.; Karupiah, G.; et al. Alternate Mechanisms of Initial Pattern Recognition Drive Differential Immune Responses to Related Poxviruses. Cell Host Microbe 2010, 8, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, M.L.; Sei, J.J.; Siciliano, N.A.; Xu, R.-H.; Roscoe, F.; Sigal, L.J.; Eisenlohr, L.C.; Norbury, C.C. MyD88-Dependent Immunity to a Natural Model of Vaccinia Virus Infection Does Not Involve Toll-Like Receptor 2. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 3557–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Hemmi, H.; akeuchi, O.; Kawai, T.; Kaisho, T.; Sato, S.; Sanjo, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Hoshino, K.; Wagner, H.; Takeda, K.; et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 408, 740–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Dai, P.; Wang, W.; Li, H.; Yuan, J.; Wang, F.; Fang, C.-M.; Pitha, P.M.; Liu, J.; Condit, R.C.; et al. Innate Immune Response of Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells to Poxvirus Infection Is Subverted by Vaccinia E3 via Its Z-DNA/RNA Binding Domain. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, J.; Huang, X.; Yang, Y. Toll-like receptor 8-mediated activation of murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells by vaccinia viral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6442–6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, C.; ausmann, J.; Lauterbach, H.; Schmidt, M.; Akira, S.; Wagner, H.; Chaplin, P.; Suter, M.; O’Keeffe, M.; Hochrein, H. Survival of lethal poxvirus infection in mice depends on TLR9, and therapeutic vaccination provides protection. J. Clin. Investig. 2008, 118, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Cao, H.; Merghoub, T.; Avogadri, F.; Wang, W.; Parikh, T.; Fang, C.-M.; Pitha, P.M.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Rahman, M.M.; et al. Myxoma virus induces type I interferon production in murine plasmacytoid dendritic cells via a TLR9/MyD88-, IRF5/IRF7-, and IFNAR-dependent pathway. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 10814–10825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Shimura, H.; Minagawa, M.; Ito, A.; Tomiyama, K.; Ito, M. Expression of functional Toll-like receptor 2 on human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2002, 30, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, J.K.; Kwon, H.J.; Kim, M.-Y.; Kang, H.; Song, P.I.; Armstrong, C.A.; Ansel, J.C.; Kim, H.O.; Park, Y.M. Expression of Toll-Like Receptors in Verruca and Molluscum Contagiosum. J. Korean Med Sci. 2008, 23, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seleit, I.; Bakry, O.A.; Abdou, A.G.; Dawoud, N.M. Immunohistochemical expression of aberrant Notch-1 signaling in vitiligo: An implication for pathogenesis. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2014, 18, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowie, A.; Kiss-Toth, E.; Symons, J.A.; Smith, G.L.; Dower, S.K.; O’Neill, L.A.J. A46R and A52R from vaccinia virus are antagonists of host IL-1 and toll-like receptor signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10162–10167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fedosyuk, S.; Grishkovskaya, I.; de Almeida, R.E., Jr.; Skern, T. Characterization and structure of the vaccinia virus NF-kappaB antagonist A46. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 3749–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, S.; Bahar, M.W.; Cooray, S.; Chen, R.A.; Whalen, D.M.; Abrescia, N.G.; Alderton, D.; Owens, R.J.; Stuart, D.I.; Smith, G.L.; et al. Vaccinia virus proteins A52 and B14 Share a Bcl-2-like fold but have evolved to inhibit NF-kappaB rather than apoptosis. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J.; Bowie, A.G. Poxviral Protein A46 Antagonizes Toll-like Receptor 4 Signaling by Targeting BB Loop Motifs in Toll-IL-1 Receptor Adaptor Proteins to Disrupt Receptor: Adaptor Interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 22672–22682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J.; Haga, I.R.; Schröder, M.; Bartlett, N.W.; Maloney, G.; Reading, P.C.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Smith, G.L.; Bowie, A.G. Vaccinia virus protein A46R targets multiple Toll-like–interleukin-1 receptor adaptors and contributes to virulence. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 1007–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysakova-Devine, T.; Keogh, B.; Harrington, B.; Nagpal, K.; Halle, A.; Golenbock, D.T.; Monie, T.; Bowie, A.G. Viral Inhibitory Peptide of TLR4, a Peptide Derived from Vaccinia Protein A46, Specifically Inhibits TLR4 by Directly Targeting MyD88 Adaptor-Like and TRIF-Related Adaptor Molecule. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 4261–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stack, J.; Doyle, S.L.; Connolly, D.J.; Reinert, L.S.; O’Keeffe, K.M.; McLoughlin, R.M.; Paludan, S.R.; Bowie, A.G. TRAM is required for TLR2 endosomal signaling to type I IFN induction. J. Immunol. 2014, 193, 6090–6102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstak, B.; Stack, J.; Ve, T.; Mangan, M.; Hjerrild, K.; Jeon, J.; Stahl, R.; Latz, E.; Gay, N.; Kobe, B.; et al. The TLR signaling adaptor TRAM interacts with TRAF6 to mediate activation of the inflammatory response by TLR4. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014, 96, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalverda, A.P.; Thompson, G.S.; Vogel, A.; Schröder, M.; Bowie, A.G.; Khan, A.R.; Homans, S.W. Poxvirus K7 Protein Adopts a Bcl-2 Fold: Biochemical Mapping of Its Interactions with Human DEAD Box RNA Helicase DDX3. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 385, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, M.; Baran, M.; Bowie, A.G. Viral targeting of DEAD box protein 3 reveals its role in TBK1/IKK epsilon-mediated IRF activation. EMBO J. 2008, 27, 2147–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Kim, S.; Ryu, W.-S. DDX3 DEAD-Box RNA Helicase Inhibits Hepatitis B Virus Reverse Transcription by Incorporation into Nucleocapsids. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 5815–5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamiya, N.; Worman, H.J. Hepatitis C Virus Core Protein Binds to a DEAD Box RNA Helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 15751–15756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedavalli, V.S.; Neuveut, C.; Chi, Y.-H.; Kleiman, L.; Jeang, K.-T. Requirement of DDX3 DEAD Box RNA Helicase for HIV-1 Rev-RRE Export Function. Cell 2004, 119, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandt, T.A.; Jacobs, B.L. Both Carboxy- and Amino-Terminal Domains of the Vaccinia Virus Interferon Resistance Gene, E3L, Are Required for Pathogenesis in a Mouse Model. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 850–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waibler, Z.; Anzaghe, M.; Ludwig, H.; Akira, S.; Weiss, S.; Sutter, G.; Kalinke, U. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Induces Toll-Like Receptor-Independent Type I Interferon Responses. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 12102–12110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, Y.M.; Gale, M. Immune Signaling by RIG-I-like Receptors. Immunology 2011, 34, 680–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Gao, X.; Barrett, J.W.; Shao, Q.; Bartee, E.; Mohamed, M.R.; Rahman, M.; Werden, S.; Irvine, T.; Cao, J.; et al. RIG-I Mediates the Co-Induction of Tumor Necrosis Factor and Type I Interferon Elicited by Myxoma Virus in Primary Human Macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2008, 4, e1000099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myskiw, C.; Arsenio, J.; Booy, E.P.; Hammett, C.; Deschambault, Y.; Gibson, S.B.; Cao, J. RNA species generated in vaccinia virus infected cells activate cell type-specific MDA5 or RIG-I dependent interferon gene transcription and PKR dependent apoptosis. Virology 2011, 413, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichlmair, A.; Schulz, O.; Tan, C.-P.; Rehwinkel, J.; Kato, H.; Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S.; Way, M.; Schiavo, G.; Sousa, C.R.E. Activation of MDA5 Requires Higher-Order RNA Structures Generated during Virus Infection. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 10761–10769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaloye, J.; Roger, T.; Steiner-Tardivel, Q.-G.; Le Roy, D.; Reymond, M.K.; Akira, S.; Pétrilli, V.; Gómez, C.E.; Perdiguero, B.; Tschopp, J.; et al. Innate Immune Sensing of Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara (MVA) Is Mediated by TLR2-TLR6, MDA-5 and the NALP3 Inflammasome. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollpeter, D.; Komuro, A.; Barber, G.N.; Horvath, C.M. Impaired Cellular Responses to Cytosolic DNA or Infection with Listeria monocytogenes and Vaccinia Virus in the Absence of the Murine LGP2 Protein. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guerra, S.; Nájera, J.L.; González, J.M.; López-Fernández, L.A.; Climent, N.; Gatell, J.M.; Gallart, T.; Esteban, M. Distinct Gene Expression Profiling after Infection of Immature Human Monocyte-Derived Dendritic Cells by the Attenuated Poxvirus Vectors MVA and NYVAC. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8707–8721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Matos, A.L.; McFadden, G.; Esteves, P.J. Evolution of viral sensing RIG-I-like receptor genes in Leporidae genera Oryctolagus, Sylvilagus, and Lepus. Immunogenetics 2013, 66, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, F.; Wagner, V.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Hartmann, R.; Paludan, S.R. Double-Stranded RNA Is Produced by Positive-Strand RNA Viruses and DNA Viruses but Not in Detectable Amounts by Negative-Strand RNA Viruses. J. Virol. 2006, 80, 5059–5064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Dai, P.; Parikh, T.; Cao, H.; Bhoj, V.; Sun, Q.; Chen, Z.; Merghoub, T.; Houghton, A.; Shuman, S. Vaccinia Virus Subverts a Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling Protein-Dependent Innate Immune Response in Keratinocytes through Its Double-Stranded RNA Binding Protein, E3. J. Virol. 2008, 82, 10735–10746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ablasser, A.; Bauernfeind, F.G.; Hartmann, G.; Latz, E.; Fitzgerald, K.A.; Hornung, V. RIG-I-dependent sensing of poly(dA:dT) through the induction of an RNA polymerase III–transcribed RNA intermediate. Nat. Immunol. 2009, 10, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, Y.H.; Macmillan, J.B.; Chen, Z.J. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell 2009, 138, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, R.; Smith, G.L. Inhibition of the RNA polymerase III-mediated dsDNA-sensing pathway of innate immunity by vaccinia virus protein E3. J. Gen. Virol. 2010, 91, 2221–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paludan, S.R.; Bowie, A.G. Immune Sensing of DNA. Immunology 2013, 38, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burdette, D.L.; Vance, R.E. STING and the innate immune response to nucleic acids in the cytosol. Nat. Immunol. 2012, 14, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, X.; Chiu, Y.-H.; Chen, Z.J. The cGAS-cGAMP-STING Pathway of Cytosolic DNA Sensing and Signaling. Mol. Cell 2014, 54, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablasser, A.; Goldeck, M.; Cavlar, T.; Deimling, T.; Witte, G.; Röhl, I.; Hopfner, K.-P.; Ludwig, J.; Hornung, V. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 498, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablasser, A.; Schmid-Burgk, J.L.; Hemmerling, I.; Horvath, G.L.; Schmidt, T.; Latz, E.; Hornung, V. Cell intrinsic immunity spreads to bystander cells via the intercellular transfer of cGAMP. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 503, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, P.; Wang, W.; Cao, H.; Avogadri, F.; Dai, L.; Drexler, I.; Joyce, J.A.; Li, X.-D.; Chen, Z.; Merghoub, T.; et al. Modified Vaccinia Virus Ankara Triggers Type I IFN Production in Murine Conventional Dendritic Cells via a cGAS/STING-Mediated Cytosolic DNA-Sensing Pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, T.; Little, M.A.; Brady, G. Targeting of the cGAS-STING system by DNA viruses. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2020, 174, 113831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaglesham, J.B.; Pan, Y.; Kupper, T.S.; Kranzusch, P.J. Viral and metazoan poxins are cGAMP-specific nucleases that restrict cGAS–STING signalling. Nature 2019, 566, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, N.; Furey, C.; Li, H.; Verma, R.; Chai, Q.; Rollins, M.G.; DiGiuseppe, S.; Naghavi, M.H.; Walsh, D. Poxviruses Evade Cytosolic Sensing through Disruption of an mTORC1-mTORC2 Regulatory Circuit. Cell 2018, 174, 1143–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meade, N.; King, M.; Munger, J.; Walsh, D. mTOR Dysregulation by Vaccinia Virus F17 Controls Multiple Processes with Varying Roles in Infection. J. Virol. 2019, 93, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, B.J.; Mansur, D.S.; Peters, E.N.; Ren, H.; Smith, G.L. DNA-PK is a DNA sensor for IRF-3-dependent innate immunity. eLife 2012, 1, e0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fok, J.H.L.; Ramos-Montoya, A.; Vazquez-Chantada, M.; Wijnhoven, P.W.G.; Follia, V.; James, N.; Farrington, P.M.; Karmokar, A.; Willis, S.E.; Cairns, J.; et al. AZD7648 is a potent and selective DNA-PK inhibitor that enhances radiation, chemotherapy and olaparib activity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burleigh, K.; Maltbaek, J.H.; Cambier, S.; Green, R.; Gale, M.; James, R.C.; Stetson, D.B. Human DNA-PK activates a STING-independent DNA sensing pathway. Sci. Immunol. 2020, 5, eaba4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, N.E.; Ferguson, B.J.; Mazzon, M.; Fahy, A.S.; Krysztofinska, E.; Arribas-Bosacoma, R.; Pearl, L.H.; Ren, H.; Smith, G.L. A Mechanism for the Inhibition of DNA-PK-Mediated DNA Sensing by a Virus. PLOS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scutts, S.R.; Ember, S.W.; Ren, H.; Ye, C.; Lovejoy, C.A.; Mazzon, M.; Veyer, D.L.; Sumner, R.P.; Smith, G.L. DNA-PK Is Targeted by Multiple Vaccinia Virus Proteins to Inhibit DNA Sensing. Cell Rep. 2018, 25, 1953–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).