Abstract

Mapping individual-tree crowns (ITCs) along with extracting tree morphological attributes provides the core parameters required for estimating thermal stress and carbon emission functions. However, calculating morphological attributes relies on the prior delineation of ITCs. Using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) framework, this review synthesizes how deep-learning (DL)-based methods enable the conversion of crown geometry into reliable biometric parameter extraction (BPE) from high-resolution imagery. This addresses a gap often overlooked in studies focused solely on detection by providing a direct link to forest inventory metrics. Our review showed that instance segmentation dominates (approximately 46% of studies), producing the most accurate pixel-level masks for BPE, while RGB imagery is most common (73%), often integrated with canopy-height models (CHM) to enhance accuracy. New architectural approaches, such as StarDist, outperform Mask R-CNN by 6% in dense canopies. However, performance differs with crown overlap, occlusion, species diversity, and the poor transferability of allometric equations. Future work could prioritize multisensor data fusion, develop end-to-end biomass modeling to minimize allometric dependence, develop open datasets to address model generalizability, and enhance and test models like StarDist for higher accuracy in dense forests.

1. Introduction

Forests are vital to the global environment: they store carbon, regulate water and climate, and support biodiversity [1,2,3,4]. Forest resources monitoring and management are crucial for climate-change mitigation, sustainable development, and accurate resource valuation [5,6]. Many applications, such as carbon accounting and biodiversity assessment, require accurate measurements at the individual-tree level, so high-quality inventories and detailed ecological studies remain essential [6]. Individual-Tree Crown Detection (ITCD) is a key first step because it identifies each tree and delineates its crown boundary [7]. These boundaries produce crown masks that support primary crown attributes such as crown area (CA) or crown projection area (CPA), tree height (TH), and crown width (CW) [8,9]. These primary attributes then enable biometric parameter extraction (BPE) for secondary estimates, including diameter at breast height (DBH), stem volume, above-ground biomass (AGB), and carbon storage [8,10]. While satellite imagery provides broad coverage, it often lacks the sub-decimeter resolution required for precise ITCD and delineation [11]. Similarly, although airborne LiDAR provides high-quality structural data, its high cost often limits frequent monitoring [12]. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based very-high-resolution (VHR) imagery bridges this gap by providing ultra-high-resolution imagery at a lower cost, which is essential for detailed individual-tree analysis [13,14].

Traditional ITCD methods, such as local-maximum filtering and watershed segmentation, depend on manually tuned parameters, which limit robustness and transferability across forest types [15,16]. These methods assume treetops form clear spectral or height peaks, but this often fails in multilayer or broadleaf canopies, leading to under-segmentation [6,17] when crowns overlap, and over-segmentation when crown shapes are complex [18,19]. As a result, they may produce inaccurate crown boundaries in VHR imagery, which can directly reduce the reliability of downstream biometric parameter extraction (BPE) [20,21]. Advances in deep learning, supported by improvements in GPU computing and neural network architectures, have addressed key limitations of traditional ITCD methods by enabling direct feature extraction from VHR imagery. As a result, deep-learning-based ITCD has become dominant, accounting for 45% of studies in 2022 [22] and 60.9% of publications after 2020 [8]. Within this framework, instance segmentation has emerged as the preferred paradigm due to its ability to generate precise crown-level masks that delineate individual-tree boundaries [23,24]. These polygon-based representations support reliable biometric parameter extraction, including CA, CW, and TH, and enable robust estimation of derived attributes such as DBH and AGB [2]. Consequently, instance-segmentation models now form the core of modern ITCD and BPE workflows [5,9,16].

Despite these advances, an important gap remains; much of the recent work emphasizes ITCD and delineation performance from UAV, airborne, or LiDAR data (often using segmentation metrics such as IoU and F1-score) (e.g., [1,8,22,25,26]). However, these provide limited synthesis on how crown outputs are converted into meaningful biometric parameters. In particular, there is a lack of consolidated guidance on the workflows, extraction principles, and evaluation protocols used to derive first-order attributes (CA, H/TH, CW) and second-order attributes (DBH, AGB, volume) from DL-generated crown masks. This produces a key gap in the literature, particularly in field-based forestry, where the effective value of ITCD and delineation depends on reliable secondary parameter estimation. In addition, while individual studies report strong results for TH, AGB, or DBH [7], comparisons across architectures and sensor combinations are still fragmented, and many DBH/AGB workflows remain dependent on site-specific allometric coefficients with limited transferability [19,20].

To address these gaps, this review is distinct in that it concentrates on UAV-based VHR imagery for individual-tree analysis and systematically links DL-based ITCD and delineation to the extraction of first- and second-order biometric parameters in diverse forest environments. We synthesize findings on extracting parameters such as CA, CW, H, AGB, and DBH, and organize the review around five themes: (1) the DL architectures and data types most commonly used for ITCD and delineation from VHR imagery; (2) the methods used to derive primary and secondary attributes, including extraction principles and evaluation; (3) the distinction between detection and delineation and the metrics used to assess them; (4) the influence of data type (e.g., RGB, CHM), platform, and sensor fusion on performance; and (5) remaining challenges, knowledge gaps, and future directions toward automated and transferable DL-based BPE.

2. Systematic Literature Review Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

We conducted this systematic review using the PRISMA reporting guideline (PRISMA 2020) [27] (Supplementary Materials). To capture peer-reviewed studies relevant to UAV-based forest remote sensing and DL, we searched Scopus and IEEE Xplore, which provide broad coverage of remote sensing, engineering, and forestry literature. Scopus and IEEE Xplore were selected as the primary databases, covering environmental and remote sensing studies as well as recent developments in neural networks and computer vision. The search string was structured into four interconnected thematic blocks using AND operators for precision. Within each block, terms related to the respective condition were combined using logical OR operators:

- (“tree crown” OR “individual-tree crown” OR ITC OR canopy OR crown* OR plant OR orchard OR forest OR plantation OR “urban tree”)

AND

- (UAV OR UAS OR drone OR “unmanned aerial vehicle” OR orthophoto OR Ortho mosaic OR “high-resolution imagery” OR “canopy-height model” OR “digital surface model” OR “digital terrain model” OR CHM OR DSM OR DTM OR DEM OR terrain* OR LiDAR)

AND

- (“deep learning” OR “convolutional neural network” OR “convolutional network” OR CNN OR “Mask R-CNN” OR “Faster R-CNN” OR R-CNN OR YOLO OR U-Net OR “instance segmentation” OR “semantic segmentation” OR detection OR delineation OR segmentation OR transformer)

AND

- (“tree height” OR “crown area” OR “crown size” OR “crown projection area” OR “crown width” OR “crown diameter” OR “canopy size” OR DBH OR “diameter at breast height” OR “trunk diameter” OR “tree morphological attributes” OR AGB OR biomass OR “Above-Ground Biomass” OR carbon OR “canopy volume” “OR “attribute estimation” OR “biophysical parameter retrieval”).

The search fields were limited to abstract, keywords, and title, while the document type was restricted to published journal articles or conference papers with full access in English. The search was further constrained to include only articles published between January 2020 and November 2025, capturing the surge in DL applications for UAV-based remote sensing post-2020 advancements in AI and drone technology. This temporal focus improves upon earlier reviews by emphasizing recent innovations in high-resolution imagery and biometric extraction. This five-year period was selected to capture recent advances in deep learning, particularly the shift toward Transformer-based models and the use of ultra-high-resolution UAV imagery.

2.2. Article Selection

Records retrieved from the database searches (n = 174; Scopus n = 39; IEEE Xplore n = 135) were screened in stages to identify studies relevant to UAV-based individual-tree analysis using DL. First, we screened subject areas and titles to remove clearly irrelevant records (e.g., studies focused on low-resolution satellite imagery or unrelated domains such as medical image analysis), which reduced the set to 112 articles. Next, abstracts and keywords were reviewed for topical relevance, resulting in 68 articles for full-text assessment. Full texts were then evaluated against predefined inclusion criteria, with eligibility independently cross-checked by two reviewers to reduce selection bias. Inter-reviewer agreement was high (approximately 90%), and any disagreements regarding eligibility were resolved through consensus discussion. Exclusion criteria included: (1) non-English publications, (2) studies that used only satellite or ground-based sensors, (3) studies that relied solely on traditional machine learning (e.g., SVM, Random Forest) or manual digitization, and (4) studies focused on stand-level classification without individual-tree analysis. The criteria for inclusion were:

- DL Implementation: The study must utilize a DL method (CNN, Transformer, or hybrid) for individual-tree analysis.

- ITCD or BPE Task: The study must address Individual-Tree Detection (ITD), Individual Crown Delineation (ICD), or quantitative Biometric Parameter Extraction (BPE). The inclusion of BPE (e.g., estimating tree height or diameter at breast height (DBH)) expands the analytical focus beyond qualitative detection to cover quantitative applications in forest inventory.

- Data Source: The primary remote sensing data must be acquired from a UAV platform (RGB, multispectral, or LiDAR); we also retained a limited number of VHR aerial (manned-aircraft) studies when they were comparable in resolution and crown-level objectives and directly supported biometric estimation.

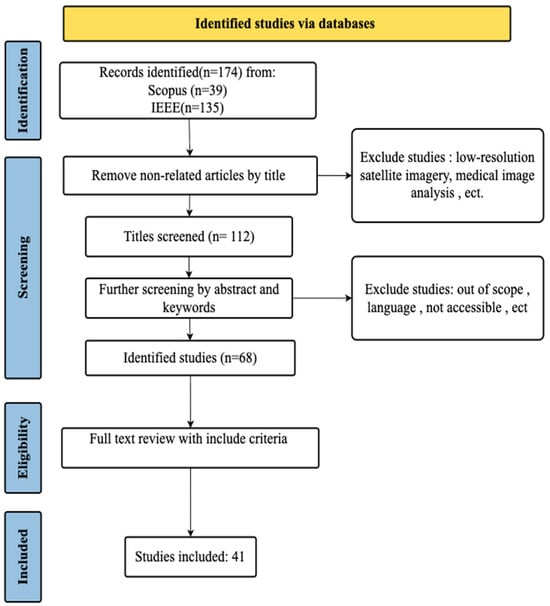

Based on these criteria, 41 studies were ultimately included in this review. A diagram of the selection process is shown in Figure 1. The included articles were selected from 15 different journals and conference proceedings, with the journal Remote Sensing containing the most studies (17 out of 41). The earliest published year is 2020, with 3 articles. This number later increased to 4 in 2021, 6 in 2022, 8 in 2023, 10 in 2024, and 10 in 2025. This indicates that applying DL to tree crown detection, delineation, and biometric extraction from UAV imagery is a rapidly expanding area of research, driven by advancements in UAV technology and AI integration—demonstrating a 233% growth in publications since 2020.

Figure 1.

Selection process of reviewed articles using the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) framework.

2.3. Synthesis Approach

We extracted data from each study using a structured protocol. Rather than simply organizing these data by study characteristics, we organized our analysis around five key research questions that cover the entire workflow from tree detection to biometric estimation.

First, we examined which deep-learning models and data types (RGB imagery, LiDAR, or combinations) work best for crown detection across different forest types. Second, we identified how crown masks are converted into tree measurements—distinguishing between direct measurements (crown area, tree height) taken from the masks themselves, and indirect measurements (DBH, biomass) that use mathematical equations or predictive models. Third, we compared tree detection (finding tree locations) with crown delineation (mapping precise crown boundaries), since they use different technical approaches. Fourth, we evaluated model performance by examining the metrics and validation methods used across studies, recognizing that accurate segmentation directly improves the reliability of biometric estimates. Finally, we identified key challenges and gaps in the literature. This approach ensures that our review provides practical insights about how methodological choices influence outcomes for forest monitoring, rather than simply summarizing individual studies. A summary of synthesis items and descriptions is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data synthesis items and descriptions.

3. Models, Data, and Environmental Context for ITCD and BPE

This section synthesizes how deep-learning methods, input data choices, and forest conditions shape the accuracy of ITCD and BPE. Model performance is not determined by architecture alone, but also depends on factors such as sensor type, spatial resolution, and canopy complexity.

3.1. Deep-Learning-Based ITCD Methods

Accurate extraction of biophysical forest attributes relies fundamentally on the preceding steps of ITCD and delineation [24,28]. Individual-tree crown detection focuses on locating individual trees (e.g., coordinates or bounding boxes) [8], while individual-tree delineation involves mapping the precise pixel-level contour and shape of the crown. Deep-learning approaches for ITCD can be grouped into four main categories: CNN-based classification models, semantic segmentation networks, object detection methods, and hybrid/emerging architectures. Most reviewed studies implement these models using widely adopted deep-learning frameworks (e.g., PyTorch) together with standard computer-vision toolkits. Table 2 summarizes the key characteristics of these groups and shows how architectural choices influence the extraction of crown geometric attributes.

Table 2.

DL Model Characteristics and Implications for Tree Attribute Extraction.

Recent studies increasingly favor instance segmentation, which produces a pixel-level binary mask for each tree within its predicted bounding box [54]. These masks help separate adjacent or overlapping crowns into distinct instances and can be converted to polygons when needed. The boundary, centroid, and area derived from the mask then provide the geometric inputs for downstream measurement and modeling steps [55,56].

Instance-segmentation models are preferred, particularly Mask R-CNN, due to the highest delineation accuracy in challenging dense or complex canopies, as shown repeatedly across studies [6,9,49,57]. For example, Hao et al. [20] applied Mask R-CNN to Chinese fir plantations using an NDVI-CHM input and reached an outstanding IoU of 91.27. This highlights how delineation quality provides the foundation for derived parameters. Another example, Xu et al. [5] utilized the Mask R-CNN-based Blend Mask algorithm for crown segmentation, achieving an accuracy of 0.893, significantly outperforming the traditional watershed algorithm’s accuracy of 0.721. While semantic segmentation (e.g., U-Net) is effective for pixel-level classification [58], its inability to separate individual-tree instances in dense canopies limits its utility for single-tree attribute extraction. Conversely, object detection models (e.g., YOLO) are fast and efficient for detection and counting [59], but their bounding-box output is fundamentally inadequate for the precise delineation needed for accurate CA estimation [40]. More recently, hybrid and emerging models have been explored to combine the advantages of different DL approaches, with the aim of improving crown delineation in complex forest scenes.

Instance segmentation often achieves high delineation accuracy but remains sensitive to labeled data quality and canopy conditions (e.g., overlapping crowns), which can reduce reliability in dense forests [44,49,60,61]. Object detection supports rapid tree counting, yet bounding boxes poorly capture irregular crown shapes, limiting accurate crown size estimation [61,62]. Semantic segmentation can delineate canopy cover, but separating adjacent trees in high-density areas remains challenging without additional refinement [52]. Therefore, model performance should be interpreted in relation to forest structure, sensor inputs (e.g., RGB versus RGB + CHM or LiDAR-derived height data), and the evaluation protocol used.

3.2. Data Sources: Platforms, Sensors, and Resolution

UAVs were the primary source for image data (34/41), with one incorporating both UAV and aerial imagery from manned aircraft. Compared to other options, UAVs typically operate at lower heights—usually below 500 m above ground level [1], yielding restricted coverage per flight but delivering VHR imagery with ground sampling distances (GSDs) often less than 5 cm and affordability compared to manned aircraft or satellite [25]. Our analysis of research showed GSDs varying from 0.3 cm to 60 cm, with an average of approximately 9.62 cm. In contrast, alternative aerial methods, like elevated airplanes or helicopters, yielded GSDs between 3 and 20 cm, with an average of roughly 10 cm. Satellite data were absent in these studies. Although LiDAR from diverse platforms exhibited pulse densities from 40 to 1000 points per square meter, averaging around 520.

As for sensors, RGB Camera imagery was the most data type used, featured in 30 studies due to low cost and technical accessibility [21,25]. Moreover, consumer-grade UAVs usually carry affordable RGB cameras, which makes data collection easy and the imagery straightforward to interpret and annotate. RGB data are also compatible with most CNN architectures, many of which were originally developed for three-channel inputs. In addition, large datasets such as COCO provide strong pre-trained RGB weights; these models can extract useful features efficiently and lower the cost of training specialized forestry models from the ground up [1,25,26].

VHR imagery is crucial due to DL-based ITCD and BPE, as it captures the detailed features essential for accurate crown detection and delineation [32,63,64,65,66,67]. Compared to satellite image, UAV imagery (e.g., 3.5 cm resolution) allows BPE to be accurately measured [17]. However, illumination/lighting conditions can affect height extraction and detection performance [68]. Model accuracy generally improves with finer spatial resolution, but the relationship is not always linear and depends on crown size and canopy complexity. For example, Zhao et al. [1] found that reducing the resolution from 4 cm to 6.5 cm decreased detection precision by 17% and the F1-score by 9% in an urban area, and GSD decreased from 10 cm to 8 cm, resulting in an 11.13% lower F1-score.

On the other hand, despite the general trend toward higher accuracy with finer resolution, accuracy does not always increase monotonically when resolution exceeds a certain level, and overly high resolution can sometimes reduce model accuracy due to interference from excessive detail or noise [9,20,23,69]. To address this issue, the concept of Crown Resolution was introduced to comprehensively evaluate the co-effect of image resolution and crown size on DL-based ITCD. The optimal image resolution is directly related to the target crown size. For classical remote sensing, it was suggested that the spatial resolution should be at least more than one-fourth of the crown diameter for detection accuracy.

3.3. Forest Environments and Parameter Coefficient Transferability

Many studies collected on ITCD and BPE generally focus on two broad categories of forest stands: pure/specific-species forests and complex mixed-species stands. Based on the review of available literature, mixed forest represents 34.1% of studies (14 studies). The remaining 65.9% (27 studies) focused on monoculture or specific-species environments, like oil palm plantations in Malaysia, apple orchards in China, eucalyptus stands in Vietnam, and olive groves in Turkey. This diversity shows that both mixed and specific-species forests are considered valuable for testing and validating ITCD models. Most studies were conducted in forest-rich countries, including China, the United States, South Korea, and Canada. China was the most frequently represented across the reviewed studies. Other contributing countries included China, Brazil, Finland, Germany, and Malaysia, highlighting a global interest in leveraging DL for forest monitoring. This wide distribution supports the applicability of ITCD frameworks in various ecological and climatic contexts.

Pine appeared most frequently among the reviewed species, representing over one-quarter of the studies, followed by spruce, fir, oak, and larch. Less common species—such as oil palm, apple, olive, eucalyptus, mango, and dipterocarps were mainly examined in agroforestry or orchard systems. The dominance of pine and other conifers is likely due to their structural uniformity and economic importance, which simplifies crown detection and parameter estimation. In contrast, species with irregular or highly variable crown shapes proved more difficult for model performance.

Dense forests with overlapping crowns reduce the accuracy of DL models for detection and parameter extraction [7]. One study reported declines from over 91% accuracy in conifer stands to around 82% in broadleaf plots due to under-segmentation [6]. Smaller or understory trees are frequently missed because upper canopies block sensor visibility, especially in regenerating or dense forests. Models such as Mask R-CNN also perform worse under these conditions, often mis-detecting individual trees or misestimating crown width [19]. Dense canopy can reduce height-estimation accuracy due to limited ground visibility, which can bias terrain models upward and, as a result, underestimate TH [18,40]. For example, Kwon et al. [31] studied canopy blockage that caused a weak correlation between crown diameter and height. To address these issues, high-resolution imagery—down to 3.5 cm/pixel—was necessary for accurate segmentation in complex natural forests. Urban environments can further weaken the usual DBH–height relationship. Because high-quality ground-truth data remain scarce in mixed forests, improved workflows should combine field calibration with stronger cross-site validation, supported where appropriate by synthetic/augmented data and coefficient recalibration.

Extraction of second-order attributes from first-order attributes depends on selecting suitable allometric coefficients, which often vary across species and sites. Allometric equations relate basic tree measurements to biomass [70], but their parameters are sensitive to local conditions and can introduce substantial uncertainty: (1) Species differences: Relationships can vary with wood density and growth form; crown-size–DBH relationships differ across species [19]. (2) Forest management: Practices such as thinning can alter crown form and change how crown metrics relate to biomass [19]. (3) Urban effects: In urban areas, pruning and nearby structures disrupt normal height-DBH ties [71]. This can lead to big biomass overestimates [63]. (4) Environmental conditions: Climate, soils, and ecological zones influence coefficient values and model transferability [51].

More geographically balanced research is also needed, particularly in underrepresented tropical regions such as Malaysia, where durian, dipterocarps, and oil palm are common. Future work should prioritize multisensor fusion, cross-site validation of coefficients, and broader inclusion of tropical species to improve generalizability.

4. Accuracy Assessment Methods

Accuracy assessment in ITCD and delineation using DL and UAV imagery and BPE typically combines quantitative and qualitative evaluation methods. The reviewed literature shows that categorical metrics are widely used to evaluate detection accuracy, while continuous metrics are generally applied to assess the precision of parameter estimation. For qualitative evaluation, visual inspection is widely used to see how well the model outputs, such as crown boundaries or detection centroids, match high-resolution reference data like UAV orthophotos, CHMs, or manually labeled polygons [6,16,33,52]. This method gives an immediate and clear view of model behavior and helps reveal spatial errors that may not appear in numerical metrics. It is useful for spotting issues in areas with dense crown overlap or big differences in tree height. In many studies, visual interpretation and manual delineation serve as the main source for building ground-truth and training datasets.

Quantitative evaluations rely on established metrics derived from computer vision and regression analysis to measure model performance. These are typically divided into two groups: categorical metrics, which address the accuracy of tree detection and delineation, and continuous metrics, which focus on the quality of parameter estimation [6,17]. However, visual assessment is subjective. Relying on it alone can lead to inconsistent validations. For robust results, visual checks should complement—not replace—quantitative metrics. Table 3 provides detailed explanations of these metrics.

Table 3.

A summary of the accuracy measures used across the reviewed studies and their meanings.

Precision and recall (PR; n = 27), F1-score (n = 19), average precision (AP; n = 12), and regression metrics (R2, RMSE, MAE; n = 18) were frequently reported metrics among the reviewed literature. Precision indicates how accurately tree crowns were identified without false positives, while recall measures the model’s ability to detect all trees present in the imagery. F1-score, the harmonic mean of precision and recall, provides a balanced view of detection accuracy, representing a specific trade-off point on the precision-recall curve. In contrast, AP captures the area under this curve by averaging precision over multiple recall levels, offering a broader performance measure. IoU measures how much the predicted crown overlaps with the reference crown. A threshold of ≥0.5 is commonly used to count a detection as a true positive. IoU-based evaluation was applied in 11 studies, apart from the R2 value, which indicates the proportion of the variance in the ground-truth measurements that is predictable from the model’s outputs, thus serving as a measure of goodness-of-fit. The RMSE provides a direct measure of the average magnitude of error in the units of the parameter (e.g., meters for width, square meters for area). Some studies also report the relative RMSE (rRMSE), which normalizes the RMSE by the mean of the observed values, providing a scale-independent measure of error.

Mask R-CNN models are recognized for their robust performance, maintaining high precision even when applied across images acquired under variable conditions (different cameras, dates, and processing techniques) [7]. Blend Mask achieved 0.893 accuracy in crown segmentation, significantly higher than the 0.721 reported for the traditional watershed algorithm [5]. In DL models designed specifically for segmentation, like StarDist, performance exceeded Mask R-CNN by over 6% in terms of delineation accuracy in mixed forests [53].

Detection and delineation accuracy generally declines as forest structure becomes more complex. Mixed-species stands with uneven canopy layers and overlapping crowns often produce lower accuracies than uniform plantations or open-grown trees [6,7,32]. For instance, Li et al. [6] reported consistently lower performance in mixed-wood and deciduous plots than in coniferous plots. Detection accuracy can also vary within the same genus, indicating that crown morphology and phenological differences among species can influence model performance [32]. Across the reviewed studies, fusing RGB imagery with height products (CHM/DSM) or vegetation indices (e.g., NDVI, VARI) more consistently improved results than using RGB alone [15,20,23,43].

Recent studies also report strong performance of DL models for extracting crown geometric parameters and tree height across different forest settings. For example, Ji et al. [23] applied ResU-Net to <10 cm UAV imagery with CHM to estimate crown width and crown projection area for Camellia oleifera in a Chinese plantation; the RGB–CHM inputs achieved the best fit (R2 = 0.9271; RMSE = 0.1282 m for width, and R2 = 0.9498; RMSE = 0.2675 m2 for CPA). Their results suggest that integrating elevation information improves crown-boundary delineation and increases measurement precision. They also found that simulated multispectral inputs (Green, Red, NIR) produced results comparable to a full hyperspectral dataset, pointing to a more cost-effective option for improving crown-geometry extraction through targeted spectral bands. Addressing the challenge of dense canopies, Cai et al. [40] developed a novel Faster R-CNN algorithm with an FPN-ResNet101 backbone specifically for a dense Loblolly pine stand in Texas, USA. Their architecture was designed to improve the extraction of shallow features, which is critical for distinguishing overlapping crowns. The model achieved a remarkable crown width extraction accuracy of R2 > 0.95, underscoring the necessity of specialized architectures for accurately quantifying tree dimensions in high-density forest environments where standard models often fail. Collectively, these studies confirm that deep DL learning models can consistently deliver high-accuracy measurements of crown geometric parameters (R2 often >0.90) from UAV data.

5. Morphological and Biophysical Attributes Extraction Methods

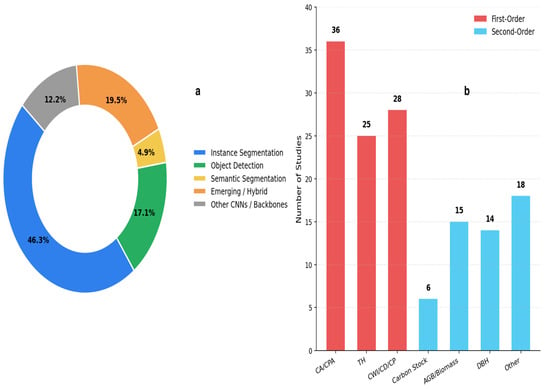

This section describes the principles and methodological approaches used to extract morphological and biophysical tree attributes from individual-tree crown delineation (ITCD) results across the reviewed studies. Instance segmentation is the most commonly used approach for individual-tree crown delineation and supports more reliable attribute extraction. First-order geometric attributes are reported more frequently than second-order parameters. Figure 2 provides a statistical summary of model usage and tree attribute extraction in ITCD research: Panel a shows the distribution of DL model types, highlighting the dominance of instance segmentation. Panel b summarizes the frequency of extracted tree attributes, distinguishing between first-order and second-order parameters.

Figure 2.

Distribution of DL model types and extracted tree attributes in UAV-based ITCD. (a) represents the types of DL models used. (b) shows the extracted tree attributes.

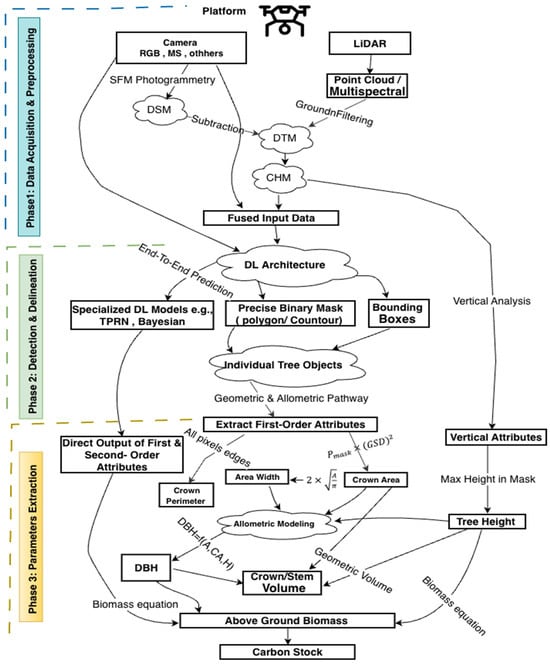

Extraction of morphological attributes can be grouped into first-order attributes (directly measured), such as tree height (TH), crown area (CA), and crown width or diameter (CW) [8], and second-order attributes (predictive or estimated), such as diameter at breast height (DBH), above-ground biomass (AGB), and basal area. First-order attributes are derived directly from remote sensing products, for example, CA and CW from segmented crown masks or bounding boxes [72], and TH from co-registered canopy-height models (CHM) or LiDAR data, and they form a crucial link between computer-vision outputs and practical forestry applications [73]. In contrast, second-order attribute extraction relies either on allometric relationships that statistically relate DBH, AGB, or carbon to measurable crown geometry and height metrics [28] or on specialized models such as Tree Parameter Regression Networks (TPRN) [24] and Bayesian frameworks that directly predict these parameters from remote sensing data [31]. Figure 3 shows a typical workflow described for DL-based models to detect/delineate the tree crown and extraction tree attributes. Table 4 provides a comprehensive overview of how various studies utilize specific deep learning models and data sources to extract key first- and second-order tree attributes. In this table, ✓ signifies that a study addressed the parameter, whereas x denotes that the parameter was not covered.

Figure 3.

Typical workflow describing the progression from UAV data acquisition and fusion to ITCD and subsequent estimation of structural and biophysical parameters.

Table 4.

Studies use DL models and data sources that are used to extract key first- and second-order tree attributes, highlighting imaging resolutions and forest type applied across recent studies.

5.1. Directly Measurable Geometric Attributes

5.1.1. Crown Geometric Parameters: Area, Projection, and Dimensional Measurements

Crown geometric parameters describe the horizontal size and shape of an individual-tree’s canopy and form the foundation of many forest measurements. The most derived metrics are CA or CPA, CW, and CP. Crown projection area is defined as the parallel vertical projection of the tree crown onto the horizontal panel [52]. Crown width, typically measured as the average north–south and east–west directions [47], while crown diameter, defined as the diameter of a circle with equivalent area, is useful for evaluating competition, productivity, and precision-agriculture tasks like variable-rate spraying [40,43,78]. Crown Perimeter (m) describes the outer boundary of the canopy and supports geometric indices like roundness and compactness, helping to describe crown symmetry and identify potential stress conditions [78].

Geometric parameters play a vital role in forestry, plantation management, orchard monitoring, and broader ecological studies as they link remotely sensed measurements to practical field decisions [44]. CA and CW support stand-density management, thinning plans, and tree health assessments. This is particularly evident in high-value plantations such as the Camellia oleifera orchards examined by Ji et al. [23], where accurate crown measurements support yield optimization. Crown size influences light interception and therefore affects photosynthesis, growth potential, competitive status, and carbon uptake. These dimensions are also associated with fruit production and resource allocation patterns [33]. Beyond productivity, crown metrics assist in evaluating habitat structure and understory light availability, which are vital for regeneration and wildlife movement [28]. Dimensional metrics like crown width and diameter are also used to assess mechanical stability and allometric scaling, guiding wind-risk evaluations and growth projections in urban or reforested stands [47], while crown perimeter indicates asymmetry that may signal stress, enabling early pest or drought diagnostics in mixed forests [30].

These metrics underpin allometric and empirical models by translating canopy shape and size into estimates of structural attributes. As shown by Goswami et al. [3], who used crown area to estimate stem stock volume in teak plantations, crown geometry is a powerful proxy for deriving diameter at breast height (DBH), above-ground biomass (AGB), and total carbon stocks [79,80]. This makes accurate, automated extraction of crown geometric parameters important for large-scale forest inventories, climate-change mitigation strategies, and sustainable forest management.

However, the accuracy of derived parameters depends strongly on how well the initial crown boundary is delineated, because under- or over-segmentation directly affects subsequent calculations [81]. Accuracy tends to decline in structurally diverse environments; for example, crown width estimation achieved high accuracy in uniform nursery plots (R2 > 0.94) but dropped in mixed forests (R2 > 0.85) and defoliated stands (R2 > 0.79) [18]. Spatial resolution also plays a critical role—coarser than 0.1 m reduces detection accuracy, while overly fine resolutions may introduce noise [32]. Optimal results are generally achieved when the crown diameter-to-pixel ratio exceeds 4:1, especially for precise attribute extraction using methods like pixel-based area estimation from VHR imagery [23].

The primary input is usually a georeferenced orthomosaic generated from UAV imagery, often combined with elevation products such as a canopy-height model (CHM) or digital surface model (DSM), which provide spatial context for crown-boundary identification [23]. The extraction pipeline follows a logical sequence. DL model, such as Mask R-CNN or a U-Net variant [82], processes the input imagery (e.g., RGB, multispectral, or fused data) to delineate the crowns. The output is a set of distinct masks, one for each tree. These pixel-based masks are converted into metric measurements using the image’s known ground sampling distance (GSD). Once a crown is segmented, the crown area (A) is calculated by multiplying the pixels of the mask by GSD. This assumes a thresholder mask (e.g., probability > 0.5) to define foliage extent, with post-processing like morphological closing to fill minor gaps.

where is the crown area, is the number of pixels in the crown mask, and GSD is the ground sampling distance (spatial resolution of the remote sensing image) in meters. Similarly, the crown diameter () [65] is often derived as.

Accurate calculation of crown area largely depends on how precisely the crown is delineated, since any over- or under-segmentation will directly affect the estimated area and diameter values [5]. To obtain the actual CA from the image, the following equation was used to determine the ratio between the number of pixels within the crown region and those within its bounding rectangle:

where represents the actual area of the tree crown, and represents the actual area of the bounding rectangle. and denote the number of pixels in the tree crown region and the rectangular region, respectively [24].

In a comparable detection-based approach, Gachana et al. [47] used DeepForest outputs from UAV orthophotos to calculate crown diameter by converting pixel-level detections into real-world coordinates and averaging the lengths of the longer and shorter sides of each bounding box. This method, also validated in studies combining airborne and LiDAR data, exemplifies how detection models can geometrically infer crown dimensions directly from bounding-box metrics rather than from polygonal areas. Finally, the crown perimeter is calculated by summing the lengths of all pixel edges along the outer boundary of the segmented crown mask, adjusted for image resolution.

5.1.2. Tree Height

Tree height describes the vertical distance from the ground to the top of the crown, typically measured in meters, and is one of the most important structural attributes in forest inventories [63]. Along with DBH, height helps determine tree volume and above-ground biomass through standard allometric equations [46,63], and it also reflects stand structure and carbon storage potential [6].

Height estimation from UAV imagery is generally based on three approaches: deriving height from elevation models, predicting it directly with DL, or inferring it through regression. The most widely used method relies on the canopy-height model (CHM) [83], which combines photogrammetric data with DL-based crown delineation to extract tree-level heights [19,63]. In most studies, this is done by linking each crown mask to a co-registered CHM and summarizing the height values inside the crown boundary (e.g., using a maximum or percentile), rather than emphasizing a fixed step-by-step pipeline. The main practical differences across papers relate to how the terrain surface is obtained (from external data such as LiDAR or from UAV-derived ground classification) and how well DSM/DTM/CHM products align with the crown masks, which can strongly affect height accuracy [84].

The height values are often validated against ground-measured heights, and accuracy is assessed using statistical metrics like R2, RMSE, and relative rRMSE (see Table 3) [9]. The accuracy of tree height estimation is highly dependent on the quality of both the DSM and, more critically, the DTM [85]. Inaccurate DTM generation, particularly in dense forests with limited ground visibility, can introduce systematic errors in the CHM, propagating directly into height estimates.

Several studies report end-to-end or multitask DL frameworks (e.g., Mask R-CNN-based pipelines) that jointly predict crown masks and tree height in a single model, reducing reliance on separate post-processing steps and external height products [9,20]. These models are trained on labeled data that include height information, often categorized into classes to allow the network to predict both crown masks and height simultaneously. This integrated approach enhances the automation of forest inventories by reducing the need for separate processing steps [20]. Other architectures, such as the Tree Parameter and Reconstruction Network (TPRN), are designed to extract structural traits like height and DBH directly from crown images, achieving high accuracy in field plots (92.7%–96%) [24].

Recent studies show that height predictions depend strongly on the input data used. Hao et al. [20] reported that NDVI-CHM inputs produced the most accurate results (R2 = 0.97, RMSE = 0.11 m, rRMSE = 4.35%), while DSM-based models performed noticeably worse (R2 < 0.70). Similarly, Fu et al. [9] found that fusing RGB with CHM yielded their best performance (R2 = 0.93, RMSE = 0.25 m, rRMSE = 3.10%), whereas RGB-DSM inputs led to substantial errors (R2 = 0.56). These findings confirm that CHM normalization is crucial for reliable height estimation.

In conclusion, overlapping tree crowns remain a major challenge in complex canopies, often leading to height overestimation. When delineation polygons unintentionally include the apex of a neighboring, taller tree, the extracted maximum CHM value reflects that tree instead, inflating the target’s height estimate [16]. Additionally, CHM accuracy is highly dependent on the underlying digital elevation model (DEM); in dense forests, limited ground returns can cause the DEM to be too high, leading to underestimated tree heights [19]. Data quality is another critical factor, especially in broadleaf forests where subtle height variation complicates CHM-based segmentation. In mixed forests, both vertical and horizontal structural complexity can reduce the reliability of height and crown-based allometric estimates, affecting the accuracy of biomass calculations [19].

5.2. Predictive and Estimated Attributes

5.2.1. Trunk Diameter

Diameter at breast height is the measurement of a tree’s trunk taken 1.3 m above the ground [86]. It is a key number in forestry, closely linked with how much wood, biomass, or carbon a tree holds, as well as its age. DBH is used in almost every forest survey to figure out basal area, timber volume, and above-ground biomass by plugging it into allometric equations. Ecologists look at DBH values to understand how crowded or diverse a forest is, and carbon researchers use them to estimate carbon storage. [86,87]. Due to DBH telling us so much about forest health, growth, and carbon stocks, it is an essential part of monitoring.

Across the reviewed studies, DBH is rarely measured directly from UAV imagery because the stem at breast height is usually hidden by the canopy. Instead, most papers estimate DBH in two ways: allometric/regression models that link DBH to crown geometry and/or height, and DL-based regression that learns DBH from crown and image features using field DBH as labels [88]. The DL model first outputs crown metrics, and an allometric equation or secondary network translates those into DBH.

Studies consistently demonstrate a strong correlation between crown attributes and DBH. CW often performs best in correlating with DBH, with reported correlation R2 reaching 0.75 [63]. For specific species, R2 between CA and field-measured DBH can reach 0.755 in complex mixed natural forest stands [17]. In tropical forests, crown diameter demonstrated a strong R2 value of 0.74 for trunk diameter prediction [46].

Allometric models express DBH as a mathematical function of crown or height metrics. The general principle:

When height is unavailable, DBH can be predicted directly from crown size. A common relationship is a power-law form:

where a and b are species-specific coefficients. This was applied by Gong et al. [17] for Malania oleifera using UAV–RGB crowns extracted with Mask R-CNN, obtaining:

Species-specific or regionally calibrated allometric equations (typically power functions or logarithmic regressions) relate crown dimensions and height to DBH. These equations are developed from field measurements and applied to remotely extracted metrics. Recent international studies have widely adopted the Jucker et al. [89] global allometric equation, which utilizes the product of tree height and crown diameter to robustly estimate DBH for a broad range of forest types and ecological regions.

Other researchers have employed alternative empirical equations to estimate DBH. For example, Xiong et al. [90] developed Equation (8) using UAV–LiDAR-derived tree height TH, CD for a 17-year-old Chinese fir plantation in Fujian, China. The model was calibrated under subtropical monsoon conditions with high-density LiDAR data (150–200 pts m−2) and validated through field measurements, achieving strong accuracy (R2 = 0.68; RMSE = 1.96 cm; rRMSE = 10.22%). This equation effectively compensates for UAV–LiDAR’s limitation in directly capturing trunk dimensions and supports precise biomass and growth estimation in subtropical plantation forests.

LiDAR studies estimate DBH from height alone, assuming a constant stem-form factor [91].

where a1 and a2 are estimated parameters from the curve fit, and when H and CA are available [92]:

where b1, to b3 are curve fit parameter estimates. These equations were tested against field data, with the Jucker model (Equation (10) variant) giving the best accuracy (R2 = 0.90, RMSE = 8.6 cm). However, Height-only allometry is efficient for uniform, mature stands with predictable taper but tends to underperform in heterogeneous forests where canopy competition modifies height–diameter ratios [91,92].

Advanced studies employ deep neural networks (DNNs), convolutional regression networks, for example, Hosingholizade et al. [43] trained a 13-layer CNN using DSM + VARI composites as inputs and field-measured DBH as labels for Pinus eldarica (2 cm GSD UAV–RGB). The model achieved RRMSE = 8.85% and R2 = 0.94 for large crowns, outperforming watershed and K-means delineations or Bayesian DL models that directly learn the nonlinear mapping from crown metrics to DBH without explicitly defining allometric equations. These models can incorporate additional environmental covariates and uncertainty quantification. Additionally, Ma et al. [24] combined Mask R-CNN with a Tree Parameter and Reconstruction Network (TPRN) (EfficientNet-B7 backbone) to predict DBH and height simultaneously from UAV–RGB. The model achieved R2 = 0.96 (DBH), illustrating the feasibility of multitask DL where DBH becomes one output node in a unified architecture.

Another strategy is using 3D reconstruction: with sufficient image overlap (including oblique angles), structure-from-motion photogrammetry or UAV–LiDAR can produce a 3D point cloud of the tree. From such point clouds, algorithms (e.g., circle-fitting at 1.3 m height) can directly estimate trunk diameter [87,93]. However, this requires penetrating the canopy; thus, it works best in sparse stands or with UAV–LiDAR that can capture lower stem points.

Performance of DBH estimation in UAV–DL studies is usually evaluated by comparing predicted values with field measurements using RMSE, MAE, and R2, often complemented by rRMSE to express error as a percentage of mean DBH. Recent work shows that Mask R-CNN and similar pipelines typically achieve R2 values of 0.77–0.85 and rRMSE of 10%–18%, depending on forest structure and crown visibility [31]. Uncertainty-aware approaches, including Bayesian DL, report that 96%–99% of predictions fall within the 95% prediction interval, highlighting good reliability for carbon and biomass applications. Overall, DL-based DBH estimation now matches and often exceeds traditional regression models, although its operational use in forestry is still emerging [94].

5.2.2. Above-Ground Biomass and Carbon Stocks

Above-ground biomass refers to the dry weight of all tree components above the soil, stems, branches, leaves, and bark, and is usually reported in Mg/ha or kg/tree. Carbon stock is then estimated from AGB by applying a species-specific carbon fraction, typically around 0.47–0.51 for most woody species. These two variables are central to evaluating forest ecosystem services, especially carbon sequestration and climate-mitigation potential [70,95]. Reliable AGB and carbon estimates are needed for applications such as REDD+ reporting, carbon-market verification, ecosystem health assessments, and timber valuation. At the tree level, AGB forms the basis for allometric models that scale biomass to stand and landscape levels, while carbon stock supports the feasibility and accountability of carbon-offset projects.

AGB is commonly estimated either with allometric regression equations that relate AGB to DBH, height, and/or crown dimensions [96] or with DL-based learned regression that predicts AGB directly from crown and image features.

Allometric Regression Equations: These empirically derived models use predictors like DBH, H, and crown dimensions to estimate AGB [19]. A common form is:

where : above-ground biomass for tree i, DBH: diameter at breast height, H: tree height, and : species-specific regression coefficients.

The selection of the final allometric equation depends critically on the tree species, local growth habits, and data availability. For example, Bhebhe et al. [91] used the simplified Chave Pantropical Model. This model estimated 161.5 Mg/ha AGB for the mixed Australian forest:

where AGB in Mg, is the species-specific wood density (), D is the diameter at breast height in cm, and H is tree height in cm (estimated using the Jucker mode, = 0.9005).

Similarly, Fu et al. [9] estimated AGB in a Pinus sylvestris plantation using UAV-derived RGB imagery and CHM processed through a Mask R-CNN pipeline (resolution: 0.01 m/pixel). After extracting CA and height, DBH was predicted via regression (R2 = 0.83), and AGB was computed using a species-specific allometric equation:

Gong et al. [17] estimated AGB for Malania oleifera in a mixed forest using UAV–RGB imagery and Mask R-CNN for crown segmentation (F1-score: 86%). DBH was predicted from canopy area using:

Then, AGB was calculated using an adapted camphor tree equation:

Kolanuvada et al. [77] introduced a simplified, crown-area–driven model that bypasses DBH entirely. Using multispectral UAV imagery (4-band, 3.48 cm GSD) over a 1.2 km2 mixed agricultural landscape in Tamil Nadu, India, they extracted individual-tree crowns via a CNN classifier (overall accuracy: 96.1%, kappa = 0.954), followed by canopy delineation using linear clustering. Instead of estimating DBH, they directly computed AGB using the following empirical allometric equation:

where AGB is in kilograms, crown area in m2, and tree height in meters.

This approach is suitable for heterogeneous tropical trees when field-based DBH is unavailable. Gong et al. [17] illustrated how UAV-based crown metrics can effectively replace DBH in biomass estimation under appropriate ecological and data conditions. Several studies calculate carbon stock from the estimated AGB using the following equation [63].

where C is the tree carbon storage, B is the tree biomass, and CF is the Carbon Content Ratio.

Recent studies also report DL-based learned regression as an alternative to allometric equations, where AGB and carbon are predicted directly from crown traits and image features. These models learn complex relationships from labeled datasets (image biomass). For instance, Kwon et al. [31] combined Mask R-CNN for object detection with Bayesian regression to predict DB probabilistically, which can then be used for AGB. A Deep Convolutional Neural Network (DCNN) approach, leveraging multiple spectral bands (G, R, NIR), achieved the highest accuracy in AGB estimation for rubber plantations, demonstrating the power of DL for direct prediction [74].

Bias appears when generalized allometric models are used across different forest types, since links between crown shape, DBH, and biomass are strongly species- and site-specific. Progress is further limited by the scarcity of field-measured AGB data, especially in tropical forests. Better accuracy requires combining high-resolution structural data, such as LiDAR, with RGB imagery to capture full 3D crown structure [19,34,43]. Using species-specific allometry and developing DL models that estimate AGB directly from crown features can also reduce error propagation [51]. Scalable labeling strategies, including unsupervised LiDAR-based methods, offer an alternative to labor-intensive field surveys [19,76].

5.2.3. Extraction of Volume-Related Attributes

Accurate estimation of 3D tree attributes—such as crown volume, stem volume, and stand-level metrics is increasingly important for precision forestry and ecological monitoring. Combining DL with UAV imagery and LiDAR makes it feasible to convert ITC delineation outputs into volumetric measurements. Crown volume, which represents the full space occupied by a tree crown, is especially useful in orchards for monitoring growth, forecasting yield, and planning spraying operations [42,75]. In forests and urban areas, CV also contributes to Living Vegetation Volume, which supports biomass and carbon-stock assessment through established allometric models [6,41].

Crown-volume estimation typically links DL-based crown segmentation with 3D structural data such as CHM or point clouds. In most studies, models like Mask R-CNN, blend Mask, or YOLOTree first identify and segment each crown [41,78], producing boundaries that define the region of interest for calculating canopy volume. These masks are then combined with height information usually derived from CHM or point-cloud data to generate a 3D representation of the crown for volume assessment [6,41]. Several methods are then used to estimate crown volume. One common approach involves computational geometry, where the 3D convex hull encloses all crown points to estimate total volume. Alternatively, the point cloud can be divided into horizontal slices, and the volume is calculated by summing the convex hull areas of each layer [75]. Another approach is voxel-based, where the space is split into small cubes (voxels), and the crown volume is the sum of occupied voxels [42]. For more uniform tree shapes, such as those found in orchards, geometric methods like the Ellipsoid Volume Method can be used [21]. This technique estimates volume based on 2D crown dimensions and height, treating the crown as a semi-ellipsoid [41]. It is especially suitable for species with regular, symmetrical shapes like Catalpa. Hu et al. [21] adopted Equation (18) to calculate the ellipsoid volume of the peach tree.

where are calculated using the North and East directional vectors obtained through the Vertical Crown Projected Area (VCPA) method. To determine the vertical axis (Ea), which represents half of the crown’s height, the normalized digital surface model (nDSM) is used to measure the tree height (Hp), and Ea is computed as half of Hp [21]. Semi-Ellipsoid Volume can be calculated using Equation (19):

where the major and minor axes (a, b) are obtained from the 2D segmentation, and the height (c) is obtained from the point-cloud data [41].

Stem volume is a primary quantitative parameter in forest inventory, directly informing timber production, economic returns, and sustainable logging plans [15,52]. Since it represents the bulk of a tree’s woody matter, stem volume is used as a foundational metric in allometric equations for AGB and carbon sequestration assessments [3].

Stem volume is typically estimated indirectly because aerial imagery provides limited visibility of the stem beneath the crown. Studies, therefore, combine DL-derived crown delineation (e.g., Mask R-CNN or BlendMask) with measurable crown attributes such as crown area (CA), crown width (CW), and tree height (H), which are then used in allometric/regression models to derive stem volume [5,20]. These attributes are then input into regression equations to estimate diameter at breast height (DBH). In the second stage, the estimated DBH and height are inserted into region-specific allometric equations to compute stem volume, most commonly using the two-parameter model where volume (V) is expressed as a function of DBH and tree height [63].

Accuracy depends on the terrain (ground) model used to generate height products, which can lead to underestimation of tree height and volume in dense stands [15,43]. In closed canopies, small ground-elevation errors can bias the CHM and propagate into height- and volume-related estimates. Another limitation is the lack of large, locally validated datasets for DBH and AGB, so researchers often use generalized allometric equations that may not match local species or site conditions, introducing bias [17,19,24,46]. To reduce these issues, stronger integration of 2D and 3D data is needed, along with DL models that estimate key biophysical traits more directly. Field calibration can also be scaled via semi-supervised learning and automated annotation, reducing dependence on extensive ground data.

6. Discussion

The systematic synthesis of findings shows a clear shift in ITCD and BPE toward DL, especially CNN-based instance-segmentation models. These approaches, such as Mask R-CNN, BlendMask, and Cascade Mask R-CNN, now appear in about 46% of recent work [1,8,16,17,19,20,75,92]. It produces an individual pixel-level mask for each tree crown, which preserves crown geometry and supports the separation of adjacent crowns. In stands with crown overlap, multilayer structure, and high within-plot variability in crown size and shape, bounding-box detection tends to include mixed-crown pixels, while semantic segmentation may label canopy cover correctly but still merges neighboring trees [16,17]. A consistent finding across the literature is that using DL-derived crown masks improves the accuracy of downstream biometric estimates by roughly 18%, showing how important geometric precision is for BPE. This is reflected in the best reported results: AGB estimation reached R2 = 0.99 [51], R2 = 0.9498 for CPA [23], and an impressively low rRMSE of 3.10% for tree height extraction through sophisticated Mask R-CNN models fused with CHM data [9]. These results confirm that combining DL with multisensor data produces reliable crown- and stand-level attributes [1,16,17,25,74]. However, accurate extraction, particularly for vertical attributes, depends on pairing RGB imagery with CHM, since CHM helps remove terrain effects and improves height-related measurements.

Despite these advances, several challenges remain: dense, multi-layered canopies still produce under-segmentation and tree miscounts [18,20,43], occlusion, complex crown shapes, spectral similarity among overlapping species and the frequent under-detection of small trees reduce accuracy in structurally complex stands [15,40,52] compounding these technical issues, about half of all studies rely on limited or geographically narrow field datasets, with tropical, Southeast Asian and African forests particularly underrepresented despite their ecological urgency. BPE accuracy is further complicated by the sensitivity of allometric equations, which depend on crown area and height [3,46]; small measurement errors propagate through nonlinear terms, often squared, introducing significant AGB estimation biases [45,63]. Allometric relationships are also highly species- and site-specific, so models derived from global databases often perform poorly when applied locally. Errors in crown delineation and height estimation propagate through allometric models, often increasing uncertainty in biomass and volume estimates; therefore, reporting errors at each processing stage is preferable to relying on a single RMSE [97]. Poor transferability of allometric equations across species and regions is repeatedly observed, for example, models built for Chinese fir, pine, or urban trees failing to generalize to new sites without recalibration [8,15,17,24,31,46,74,76]. In urban settings, the TH–DBH relationship itself becomes unstable due to pruning, shading, and restricted growing space, with R2 values reported as low as 0.04 [63]. Model transferability is often limited by differences in forest structure and species composition, variations in UAV sensors and acquisition settings, and the site-specific nature of allometric relationships used to estimate DBH and biomass, which reduce generalization across regions [98].

To address these challenges, several best practices and innovative techniques have emerged. Consistent use of RGB + CHM or RGB + DSM remains the strongest contributor to CA, height, and AGB accuracy [15,19,20,43], which consistently provide 2%–5% improvements in R2 for CW, CA, and tree density across heterogeneous forests [15,41]; for vertical attributes such as height and volume [19]. Model performance is context-dependent, as seen in the high accuracy attained in young regenerating conifers F1 = 0.91, R2 = 0.93 [16]. New architectural approaches, such as StarDist’s star-convex/polygon formulation, proved necessary and effective in handling complex irregular crowns, outperforming Mask R-CNN by 6% [53]. The success of StarDist is largely attributed to its ability to treat each tree as a distinct object with a unique mask, which is vital for calculating crown area. These improvements are often dataset-specific and highly dependent on the uniformity of crown shapes in the training set. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to claim these gains are statistically significant across diverse or irregular natural forest environments. Species- and site-specific allometry, supported by Bayesian or multivariate regression, improves generalizability where local models are lacking [5,31]. Self-supervised approaches that use LiDAR-derived crown pseudo-labels enhance AGB estimation in complex stands [19,42]. Direct point-cloud DL (PointNet++, MinkowskiNet, FPConv) avoids CHM interpolation artifacts and supports robust 3D volume estimation, especially when paired with convex hull or voxel-based models in orchards [18,43,44]. Integrating vegetation indices such as NDVI or VARI with DSM/CHM in CNN inputs improves discrimination of vegetation types and crown edges, particularly for pine and Chinese fir [20,43], while instance-segmentation models like Mask R-CNN and BlendMask are increasingly prioritized because their masks directly yield crown area and size for downstream allometric BPE [5,15,24,46]. Two-stage pipelines, for example, CHM-based Mask R-CNN detection followed by 3D U-Net clustering on LiDAR point clouds, show clear gains over Mask R-CNN alone by combining 2D efficiency with full 3D structural detail [6].

Compared with previous reviews, this work extends the literature by quantitatively benchmarking the added value of multimodal fusion, instance segmentation, and emerging architectures (e.g., StarDist, Transformer-based models), and by explicitly documenting how mask-based outputs are now used as primary inputs to predict secondary traits such as DBH and AGB [5,26,46,74]. It also shows that the performance gap between expensive LiDAR/HSI acquisitions and more accessible RGB-based workflows can be significantly narrowed by strategic fusion with derived CHM/DSM, easing hardware cost constraints in many operational settings [2,6,20]. Looking ahead, promising directions include direct crown-to-biomass regression that bypasses explicit allometry, systematic uncertainty quantification, large geographically balanced benchmarks focused on multilayer tropical forests, and advanced hybrid DL architectures that combine CNNs, transformers, multisensor fusion, and attention mechanisms such as EMA or BiFPN to better handle occlusion, mixed crowns, and contextual information [74,76].

7. Conclusions

This systematic review explores how recent advances in DL—particularly instance-segmentation models such as Mask R-CNN—provide the precise crown masks required for reliably measuring attributes like crown area, height, biomass, and carbon. Our analysis compared model types, data sources, and sensor fusion strategies. We consistently observed stronger performance when RGB imagery was integrated with CHM. However, challenges remain, including crown overlap, forest variability, and limited model generalizability across different sites. In addition, a critical “allometric bottleneck” persists when estimating biomass and carbon from crown data. Many workflows still rely on allometric equations calibrated for specific species and conditions, and these relationships may not transfer reliably across forest types without careful validation and recalibration. Future research should prioritize: (1) developing end-to-end DL models that directly predict biomass and carbon stocks to reduce allometric dependency, (2) develop large, open-access datasets for biodiverse tropical forests, (3) integrate multisensor fusion (e.g., RGB-LiDAR) to mitigate canopy occlusion in natural forests, and (4) develop and validate emerging architectures such as StarDist to dense canopy occlusion. Addressing this challenge is essential for transforming automated tree-level analysis into a reliable, scalable tool for global forest carbon accounting and sustainable management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17020179/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.T.M.A. and C.Y.K.; methodology, A.S.T.M.A.; formal analysis, A.S.T.M.A.; investigation, A.S.T.M.A., L.S.T., and C.Y.K.; resources, A.S.T.M.A. and C.Y.K.; data curation, A.S.T.M.A. and C.Y.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.T.M.A.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.K. and L.S.T.; visualization, A.S.T.M.A. and C.Y.K.; supervision, C.Y.K. and L.S.T.; project administration, A.S.T.M.A.; funding acquisition, M.R.B.A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Telekom Malaysia Research and Development (TM R&D) under Grant No. MMUE/240088.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, H.; Morgenroth, J.; Pearse, G.; Schindler, J. A Systematic Review of Individual Tree Crown Detection and Delineation with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN). Curr. For. Rep. 2023, 9, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dou, X.; Liang, X. Fine-Grained Individual Tree Crown Segmentation Based on High-Resolution Images. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2025, XLVIII-G-2, 1529–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, A.; Khati, U.; Goyal, I.; Sabir, A.; Jain, S. Automated Stock Volume Estimation Using UAV-RGB Imagery. Sensors 2024, 24, 7559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, C.; Ji, L.; Zuo, Z.; Beckline, M.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Xiao, X. Development of Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation, Its Problems and Future Solutions: A Review. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 159, 111653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Su, M.; Sun, Y.; Pan, W.; Cui, H.; Jin, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, P. Tree Crown Segmentation and Diameter at Breast Height Prediction Based on BlendMask in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hu, B.; Shang, J.; Remmel, T.K. Two-Stage Deep Learning Framework for Individual Tree Crown Detection and Delineation in Mixed-Wood Forests Using High-Resolution Light Detection and Ranging Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.; Pukrop, M.; Beckschäfer, P.; Waske, B. Individual Tree Detection and Crown Delineation in the Harz National Park from 2009 to 2022 Using Mask R–CNN and Aerial Imagery. ISPRS Open J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 13, 100071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yuan, S.; Li, W.; Fu, H.; Yu, L.; Huang, J. A Review of Individual Tree Crown Detection and Delineation from Optical Remote Sensing Images: Current Progress and Future. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2025, 13, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Xiao, W.; Du, S.; Guo, W.; Liu, X. Automatic Detection Tree Crown and Height Using Mask R-CNN Based 2 on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Images for Biomass Mapping. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 555, 121712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, N.; Narine, L.L.; Wilson, A.E. Forest Aboveground Biomass Estimation Using Airborne LiDAR: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. For. 2025, 123, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, R. Mapping Tree Species Using Advanced Remote Sensing Technologies: A State-of-the-Art Review and Perspective. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 2021, 9812624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Meng, R.; Tan, Y.; Lv, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, B.; Zhao, F. Comparison of UAV-Based LiDAR and Digital Aerial Photogrammetry for Measuring Crown-Level Canopy Height in the Urban Environment. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 69, 127489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizam Tahar, K.; Asmida Asmadin, M.; Alam, S.; Aman Hj Sulaiman, S.; Khalid, N.; Norhisyam Idris, A.; Hezri Razali, M. Individual Tree Crown Detection Using UAV Orthomosaic. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2021, 11, 7047–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, R.J.L.; Jayathunga, S.; Elleouet, J.S.; Steer, B.S.C.; Watt, M.S. UAV-Enabled Evaluation of Forestry Plantations: A Comprehensive Assessment of Laser Scanning and Photogrammetric Approaches. Sci. Remote Sens. 2025, 12, 100245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Liang, R.; Ding, Z.; Wang, B.; Huang, S.; Sun, Y. Instance Segmentation and Stand-Scale Forest Mapping Based on UAV Images Derived RGB and CHM. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, A.J.; Goodbody, T.R.H.; Coops, N.C.; Hervieux, A.; Bater, C.W.; Martens, L.A.; White, B.; Röeser, D. Automatic Delineation and Height Measurement of Regenerating Conifer Crowns under Leaf-off Conditions Using Uav Imagery. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Kou, W.; Lu, N.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Lai, H.; Chen, B.; Wang, J.; Li, C. Individual Tree AGB Estimation of Malania Oleifera Based on UAV-RGB Imagery and Mask R-CNN. Forests 2023, 14, 1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Jiang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yun, T. Individual Tree Crown Segmentation Directly from Uav-Borne Lidar Data Using the Pointnet of Deep Learning. Forests 2021, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, K.; Chau, J.; Rudd, S.; Robinson, D.T.; Chen, J.; Cyr, D.; Gonsamo, A. Direct Estimation of Forest Aboveground Biomass from UAV LiDAR and RGB Observations in Forest Stands with Various Tree Densities. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Lin, L.; Post, C.J.; Mikhailova, E.A.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.; Yu, K.; Liu, J. Automated Tree-Crown and Height Detection in a Young Forest Plantation Using Mask Region-Based Convolutional Neural Network (Mask R-CNN). ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 178, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, D.; Yang, G.; Chen, F.; Zhou, C.; Chen, W. A Robust Deep Learning Approach for the Quantitative Characterization and Clustering of Peach Tree Crowns Based on UAV Images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 3142288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Ho, H.W.; Zhou, Y.; Suandi, S.A.; Ismail, F. A Comprehensive Review on Tree Detection Methods Using Point Cloud and Aerial Imagery from Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Yan, E.; Yin, X.; Song, Y.; Wei, W.; Mo, D. Automated Extraction of Camellia Oleifera Crown Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Visible Images and the ResU-Net Deep Learning Model. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 958940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Yang, G.; Lu, H.; Zhang, X. Forest Three-Dimensional Reconstruction Method Based on High-Resolution Remote Sensing Image Using Tree Crown Segmentation and Individual Tree Parameter Extraction Model. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, Y.; Kentsch, S.; Fukuda, M.; Caceres, M.L.L.; Moritake, K.; Cabezas, M. Deep Learning in Forestry Using Uav-Acquired Rgb Data: A Practical Review. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abreu-Dias, R.; Santos-Gago, J.M.; Martín-Rodríguez, F.; Álvarez-Sabucedo, L.M. Advances in the Automated Identification of Individual Tree Species: A Systematic Review of Drone- and AI-Based Methods in Forest Environments. Technologies 2025, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Song, B.; Park, K. Mapping Individual Tree Crowns to Extract Morphological Attributes in Urban Areas Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Based LiDAR and RGB Data. Ecol. Inf. 2025, 88, 103165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, K.; Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Huang, Y.; Yan, Y. BlendMask: Top-Down Meets Bottom-Up for Instance Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Z.; Chai, G.; Lei, L.; Jia, X.; Zhang, X. Individual Tree Species Identification and Crown Parameters Extraction Based on Mask R-CNN: Assessing the Applicability of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Optical Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.; Im, S.K.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, Y.E.; Kwon, C.G. Estimation of Tree Diameter at Breast Height from Aerial Photographs Using a Mask R-CNN and Bayesian Regression. Forests 2024, 15, 1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Wang, Q.; Iio, A. Tree Crown Detection and Delineation in a Temperate Deciduous Forest from UAV RGB Imagery Using Deep Learning Approaches: Effects of Spatial Resolution and Species Characteristics. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, H.; Tan, T.; Cui, M.; Huang, Z.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L. Multi-Species Individual Tree Segmentation and Identification Based on Improved Mask R-CNN and UAV Imagery in Mixed Forests. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, M.; Mango, J.; Xin, L.; Meng, C.; Li, X. Individual Tree Detection and Counting Based on High-Resolution Imagery and the Canopy Height Model Data. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 27, 2162–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, J.G.C.; Hickman, S.H.M.; Jackson, T.D.; Koay, X.J.; Hirst, J.; Jay, W.; Archer, M.; Aubry-Kientz, M.; Vincent, G.; Coomes, D.A. Accurate Delineation of Individual Tree Crowns in Tropical Forests from Aerial RGB Imagery Using Mask R-CNN 2022. Remote Sens. Ecol. Conserv. 2023, 9, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terven, J.; Córdova-Esparza, D.M.; Romero-González, J.A. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leibe, B.; Matas, J.; Sebe, N.; Welling, M. (Eds.) Computer Vision-ECCV 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal Loss for Dense Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2999–3007. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, C.; Xu, H.; Chen, S.; Yang, L.; Weng, Y.; Huang, S.; Dong, C.; Lou, X. Tree Recognition and Crown Width Extraction Based on Novel Faster-RCNN in a Dense Loblolly Pine Environment. Forests 2023, 14, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Rao, S.; Ma, W.; Song, Q.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Xie, J.; Wen, X.; Gao, W.; Chen, Q.; et al. YOLOTree-Individual Tree Spatial Positioning and Crown Volume Calculation Using UAV-RGB Imagery and LiDAR Data. Forests 2024, 15, 1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gang, M.S.; Sutthanonkul, T.; Lee, W.S.; Liu, S.; Kim, H.J. Estimation of Strawberry Canopy Volume in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle RGB Imagery Using an Object Detection-Based Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2024, 24, 6920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosingholizade, A.; Erfanifard, Y.; Alavipanah, S.K.; Millan, V.E.G.; Mielcarek, M.; Pirasteh, S.; Stereńczak, K. Assessment of Pine Tree Crown Delineation Algorithms on UAV Data: From K-Means Clustering to CNN Segmentation. Forests 2025, 16, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straker, A.; Puliti, S.; Breidenbach, J.; Kleinn, C.; Pearse, G.; Astrup, R.; Magdon, P. Instance Segmentation of Individual Tree Crowns with YOLOv5: A Comparison of Approaches Using the ForInstance Benchmark LiDAR Dataset. ISPRS Open J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 9, 100045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jiang, M.; Li, H.; Shen, Y.; Song, J.; Zhong, X.; Ye, Z. Urban Carbon Stock Estimation Based on Deep Learning and UAV Remote Sensing: A Case Study in Southern China. All. Earth 2023, 35, 272–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, F.W.; Kurniawan, I.F.; Asyhari, A.T. Automated Biomass Estimation Leveraging Instance Segmentation and Regression Models with UAV Aerial Imagery and Forest Inventory Data. In Proceedings of the COMNETSAT 2024—IEEE International Conference on Communication, Networks and Satellite; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 521–528. [Google Scholar]