Abstract

Accurate Digital Terrain Models (DTMs) are essential for managing forest drainage networks as a crucial element of water management, yet dense canopies and complex micro-topography challenge Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) precision. This study evaluates the vertical accuracy of an ALS-derived DTM specifically within forest drainage ditches, utilizing 706 GNSS and total station measurements for validation. The results indicate a positive elevation bias, with a mean elevation error of 0.415 m and an RMSE of 0.464 m, 54.7% higher than the 0.3 m declared in the DTM technical report. Forest height, acting as a proxy for forest structural density and canopy closure, was significantly associated with a reduction in ground reflection density and an increase in the distance to the nearest ground reflection (p < 0.05). Mixed-effects ANOVA confirmed that there are significantly more ground reflections in low vegetation (0–1 m). Crucially, multiple regression analysis revealed that forest height was not the primary driver of elevation error; instead, ditch geometry was the most significant predictor. Narrower ditches exhibited substantially higher errors than wider ones, regardless of the canopy height. Furthermore, while ground reflection density decreased in mature stands, this reduction did not significantly diminish DTM vertical accuracy, suggesting that some of the LiDAR reflections of low vegetation could be misclassified as ground reflections, decreasing accuracy. These findings suggest that while ALS is effective for general forest topography and mapping drainage infrastructure, its application may require corrections for ditch dimensions rather than vegetation height alone to mitigate systematic overestimation of ditch bed elevations.

1. Introduction

Water plays a crucial role in forestry, and effective water cycle management is essential for maintaining healthy forests and achieving optimal production [1,2,3]. One of the critical elements of water management in waterlogged forest stands is the use of drainage ditches [4]. Their importance is particularly evident in locations where the forest itself is not sufficient to maintain the water balance [5]. The use of a network of drainage ditches is also common in other sectors, such as agriculture, where it has a positive impact on soil quality, pollution control, and increased biodiversity [6,7,8]. They are regularly maintained (Figure 1a), but during logging or disaster removal, they are often damaged or destroyed (Figure 1b). For them to function correctly, it is necessary to prevent them from becoming clogged or blocked [9,10,11]. Maintaining drainage ditches to keep them working properly is key not only in forestry but also in other sectors, such as agriculture [8]. To assess the effectiveness and functionality of a drainage ditch network, it is necessary to know not only its characteristics, such as the position, number, and density of individual ditches, but also their condition and any existing damage.

Figure 1.

(a) Maintenance of a drainage ditch. (b) Damage to the drainage ditch network after logging, caused by the movement of machinery.

Manual mapping of the position and condition of drainage ditches in stands using surveying methods is a demanding process that requires specific equipment and qualified personnel. If it is necessary to map the entire complex network, the manual method is also time-consuming. When using the Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), it is necessary to also utilize real-time kinematics (RTK), which allows the achievement of centimeter-level accuracy [12]. Without RTK, it is only possible to achieve an accuracy of around 2–10 m. Also, it is not always possible to use the GNSS in a forest environment because forest stands negatively affect accuracy. While it is technically possible to achieve centimeter-level accuracy [13], other studies state that GNSS-RTK accuracy under forest stands ranges from 1 to 5 m [14,15]. The advantage of this approach is its high accuracy and the ability to assess specific conditions at a given location [16,17]. A possible alternative to manual mapping of drainage ditches is the use of modern technologies, such as light detection and ranging (LiDAR), which allows for the capturing of the earth’s surface in the form of a point cloud. To capture large areas, it is suitable to use methods like aerial laser scanning (ALS) [18]. Based on point cloud data, it is possible to create detailed digital elevation models (DEMs). The digital surface model (DSM) is a type of DEM that includes vegetation and artificial structures, and it can be used to identify them [19]. These modern methods are already commonly used in forestry, for example, to assess biodiversity in stands [20], the effects of stress factors, stand height, biomass stocks [21], or to identify structures within forest stands [19,22] or their heights [23,24]. In the context of these modern methods, manual measurements are primarily used for correction and calibration [17] and to verify accuracy [25,26]. There are also several ways to identify the position of a ditch-like structure [27,28,29]. For this purpose, another type of DEM called a digital terrain model (DTM) is used. DTM captures the bare ground, and it is created by filtering out LiDAR reflections that did not land on terrain using specialized algorithms [30]. In the case of DMR5G, which is the source of DTM for the Czech Republic, this process is known as robust filtration. However, this process is not entirely reliable, and therefore, a manual check is subsequently performed using specialized software [31]. One of the most commonly used methods to identify the ditches is based on the principle of determining the flow direction from each cell of the raster representing the DTM. To achieve this, it is possible to use algorithms such as D8, MFD, or D-infinity [32]. Before the flow analysis, it is necessary to remove local terrain depressions from the DTM [33,34]. Subsequently, the flow-accumulation algorithm is used to determine the position of the runoff lines [35]. The second commonly used method identifies the presence of channels by using landscape curvature and identifies channels in places where there is a significant, positive curvature in one direction and almost no curvature in the perpendicular direction [36,37,38]. The ability of these methods to identify ditches is dependent on the accuracy and resolution of the used DTM [39], which, in turn, depends on the accuracy and density of the underlying LiDAR point cloud dataset [40].

LiDAR systems are complex and consist of several parts (GPS, INS, and laser scanner), and due to this high complexity, there are many factors that can affect their accuracy [41,42]. For the accuracy of the resulting DTM, the type of land cover is an essential factor [43]. Dense vegetation, such as a forest stand, obstructs the direct view of the surface and decreases the penetration power of the LiDAR laser beam [44]. Studies show that the presence of forest cover has a significant impact on the number of reflections classified as ground, and thus on the resolution and probably the accuracy of the resulting DTM [45,46,47]. According to Brázdil [31], the error of DMR5G is almost twice as high in forested terrain as in open areas. Adam et al. [48], on the contrary, state that forest stands do not cause a significantly lower DTM accuracy compared to open fields. Other studies claim that while forest stands can significantly affect the accuracy of DTM, lower vegetation such as bushes and shrubs can pose a bigger problem than forest stands [16]. This is probably due to its higher relative density [49] or because there is a bigger chance that reflections on this type of vegetation are incorrectly classified as ground by used algorithms [46,50,51,52]. A significant effect of the season of data acquisition on DTM accuracy was also observed. This is mainly true for deciduous forests for leaf-on and leaf-off intervals, where there is a significant difference in LiDAR reflection density [46,53,54]. An important factor influencing the elevation accuracy of a LiDAR-derived DEM is the presence of water, which can scatter and or absorb NIR light wavelengths [55]. This is a problem when extracting DTM of bare ground, where even small amounts of moisture content in soil can lead to an overestimation of elevation [56,57]. A similar effect can be observed for DEMs in general or when modeling under wet vegetation [58]. The ability of DEMs to capture topographic structures is also dependent on their size in relation to the resolution of the digital model. He [59] stated that the STRM-derived DEM lacks sufficient resolution to identify smaller gullies, cracks, and similar features. Similarly, digital elevation models with higher resolutions derived from ALS LiDAR data may still struggle to identify ditches and channels that are narrower than 1 m. The accuracy of LiDAR technology when scanning through forest cover is also the subject of research in other fields, such as the study of archeological finds [30,60,61]. This research aimed to determine whether the vertical accuracy of the digital relief model of the Czech Republic (DMR5G) as a DTM source for the Czech Republic within drainage ditch networks is influenced by forest cover and its structural characteristics. While the physical obstruction of LiDAR pulses is directly caused by canopy density and the leaf area index, these structural parameters are often difficult to obtain across large scales. Consequently, this study utilizes forest height as a proxy metric for stand maturity and structural complexity. As canopy height is one of the most readily available products derived from ALS data, understanding its relationship with ground penetration is essential for practical topographic mapping. Based on this approach, the following hypotheses were tested: H1: Forest height, acting as a proxy for canopy closure and stand density, will have a significant impact on the difference between the GNSS- and a DTM-derived elevation. H2: There will be a significant effect of forest height on the density of LiDAR ground reflections, reflecting the increased probability of signal interception in taller, more mature stands. H3: The density of LiDAR ground reflections will be negatively correlated with the elevation difference between GNSS and the DTM, as lower point densities reduce the model’s ability to resolve narrow ditch bed geometries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

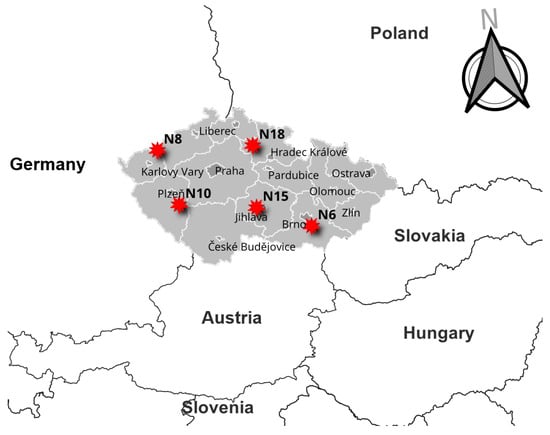

Data collection took place at five locations in different parts of the Czech Republic (Figure 2). The first location (N6) comprises pasture fields, meadow enclaves, and strips of trees in the Bažantnice Měnín area of southern Moravia, at coordinates 49.067225, 16.694078. The average vegetation height was the second smallest of all locations. This location had the widest range of ditch depth and width out of all locations. The overall slope at this location is near zero, and its area was 161 ha. The appearance of this location is captured in Supplementary Figures S1–S4. The second location (N8) comprises water-influenced habitats in the northern part of the country, located in the Ore Mountains at coordinates 50.422809, 13.081773. There is an extensive backbone system of drainage channels. The range of ditch depth and width was the second widest, but the average ditch depth and width was the largest out of all locations. The average height of forest stands was 0.76 m, and it comprises mainly smaller trees, bushes, or shrubs. The overall terrain slope was near zero, and the location area was 75 ha. The appearance of this location is captured in Supplementary Figures S5–S10. The third location (N10) is situated in the southwest of the Czech Republic, near the Chejlava National Park, at coordinates 49.545073, 13.543798. The average height of the forest stands was 20.31 m, and it comprised mostly adult spruce trees. The overall slope was around 5%–6%, and the location area was 164 ha. The drainage ditches were relatively smaller, and the range of both depth and width was narrower compared to previous locations. The appearance of this location is captured in Supplementary Figures S11–S15. The fourth location (N15) is situated in central Bohemia at coordinates 49.428879, 15.410424. It consists of a system of relatively shallow and narrow ditches. The average height of the forest stands was 22.28 m, and it comprised mostly adult spruce trees. The range of both width and depth was very narrow. The overall slope was around 1%–3%, and the location area was 14 ha. The appearance of this location is captured in Supplementary Figures S16–S20. The fifth location (N18) comprises water-influenced habitats in northern Bohemia at coordinates 50.410048, 15.430901. The average height of the forest stands was 1.18 m. It comprised low-growth forest stands, and a large part of the measured area was in an open field. The ditches here were very narrow, and their average depth was the smallest of all locations. The overall slope was around 1%–2%, and the location area was 23 ha. At the same time, these were the fewest measured points (45) out of a total of more than 700. The appearance of this location is captured in Supplementary Figures S21–S25.

Figure 2.

Map of research locations (indicated by red stars) within the Czech Republic.

2.2. Reference GNSS Data

Selected sections of drainage ditches at individual locations were surveyed in the summer of 2022. Three points of the cross-section (edge, bottom, edge) perpendicular to the axis of the ditch were measured. The EPSG:5514 (S-JTSK/Krovak East North) coordinate system was used for the measurements, as it is the native coordinate system of the Czech Republic. Reference geodetic data, where an accuracy of less than 1 cm could be achieved, was obtained using GNSS technology. A Trimble Rover R2 receiver and a TRIMBLE TSC5 controller connected to the State Network of Permanent Stations (CZEPOS), which provides RTK (real-time kinematics) service, were used. Use of RTK was crucial to achieve the required accuracy around 1–2 cm. Without RTK, it is not possible to achieve a centimeter level of accuracy. In areas where it was not possible to achieve the required accuracy, a Trimble C5 total station was used. Points were then selected based on measurement accuracy, specifically the Position Dilution of Precision (PDOP) value. Measurements with a PDOP value of <2 were used for the research. A total of 706 points were selected from all locations, representing 93% of the original 763 measured points. The points were converted to a vector layer for further processing, which was performed in QGIS 3.40.

2.3. DMR5G as a Source for DTM in the Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic, the source (DTM) is a fifth-generation digital terrain model (DMR 5G), which is created using LiDAR technology and aerial laser scanning (ALS). Data collection of DMR5G took place between 2009 and 2016, and the results in the form of a triangulated irregular network (TIN) are available on the website of the Czech Institute of Surveying, Mapping and Cadastre (ČÚZK). DMR5G is in the EPSG: 5514 (S-JTSK/Krovak East North) coordinate system and uses the Baltic Vertical System After Adjustment (Bpv). In the technical report [31], the declared mean error is 0.18 m in open terrain and 0.30 m in forested terrain. DTM, for purposes of this study, was created from the DMR5G-based point cloud dataset in LAS (ASPRS LASer) format. We used the tool “Export to raster” in QGIS 3.40 software. The pixel size of this DTM was chosen to be 0.1 m.

2.4. Difference in Elevation Between DMR5G-Derived DEM and Reference GNSS Data

The DTM created from the DMR5G data was used to determine the elevation at each point measured using the GNSS reference method. The QGIS 3.40 software and the “Sample raster values” tool were used to determine the elevation, the value of the “z” coordinate, according to DMR5G. This sampled value was added to the attributes and then compared with the attribute representing the elevation obtained using the GNSS reference method. The “field calculator” tool in QGIS 3.40 software was used for comparing these two values. The value of the reference elevation from the GNSS was subtracted from the value of the DMR5G-derived elevation so that the differential value is positive when DMR5G overestimates and negative when it underestimates the elevation. This way, a new attribute was created for the layer of measured GNSS points, expressing the value of the difference between the two elevation values (z_DELTA).

2.5. Forest Height

Data on forest stand height in proximity to each measured point were obtained by subtracting values of elevation from DTM and DSM. DSM was based on a first-generation digital surface model (DMP1G). The DMP1G point cloud contains all points that were not filtered in any way, and therefore, it includes forest stands. Creation of DSM was carried out as described for DTM. The value of forest height (f_HEIGHT) was added to the attribute table utilizing the “sample raster values” tool in QGIS 3.40 software. Both DMR5G and DMP1G were created based on the same ALS data, and therefore, the forest height is valid as of the date the DMR5G was created.

2.6. Ditch Width and Depth

The width of the ditch (d_WIDTH) measured in meters was determined for each measurement point. The width was defined as the distance between points on the edges of the banks that were part of the same cross-section as a specific measurement point on the bottom of the ditch. This distance was determined in QGIS 3.40 software using the tools “Distance to nearest feature” and “Join attributes by nearest”. The depth of the ditch (d_DEPTH) measured in meters was determined as the difference between the average values of the elevation at two points of the given cross-section and the elevation of the point at the bottom of the ditch. Both values were added to the attributes of the GNSS-measured points layer.

2.7. Number of Ground Reflections and Distance from GNSS Measurement to Nearest Reflection

For each measured point, the number of LiDAR ground reflections within a radius of 2.5 m (r_COUNT) and the distance to the nearest reflection (r_DIST) were determined. First, the LAS (ASPRS LASer) file with DMR5G data was converted to vector form in QGIS 3.40 software using the “Export to vector” tool. The number of reflections was determined in QGIS 3.40 software using the “Join attributes by location” tool as the number of DMR5G points located in a 2.5 m buffer zone created using the “Buffer” tool around the measured GNSS points. The distance to the nearest reflection was determined in QGIS 3.40 software using the “Distance to nearest feature” tool. Both values were added to the attributes of the measured GNSS points layer.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed in the R programming language. The significance level α = 0.05 was chosen for the analysis. Descriptive statistical parameters were calculated for all variables in the entire dataset (Table 1) and separately for each of the five locations (Table 2). The normality of the distribution of the dependent variable, which was the difference in elevation derived from the GNSS and DTM, was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. RMSE was calculated to obtain the actual accuracy of the DTM-derived elevation. Variables were scaled by standard deviation. Data were collected from five different stands. Since the data distribution was slightly different from the normal distribution, a one-way nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis test) was used to assess the difference between these stands. Duncan’s post hoc test has been used to determine the sites that differed most from one another. We expected a significant effect of ditch dimensions. For this reason, multiple regression was used to model the impact of the forest height and its significance on the value of the difference in elevation, with the values of ditch depth and width also included in the model as predictor variables. First, all locations were modeled together. Next, we used mixed-effects models with location as a cluster variable. This allowed us to assess the relationship between variables separately for each location. Finally, we created a separate model for measurements where the forest height was under and above 3 m, respectively. Each full model was then compared to a corresponding reduced model without forest height as a predictor. The R2 values for each model were compared. This approach allowed us to assess the significance of forest height while controlling for the influence of ditch dimensions. Since the distribution of our data was slightly different from a normal distribution, we used robust linear regression, which is more appropriate for this case. To test the effect of forest cover on LiDAR reflection density, we tested the relationship between both the number of reflections and the distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest reflection as dependent variables, and forest height as a predictor variable. Dependent variables followed Poisson and Gamma distributions, respectively; therefore, we used generalized linear models with appropriate link functions. Next, we used generalized mixed-effects models with location as a cluster variable to assess the relationship between variables separately for each location. Finally, we created a separate model for measurements where the forest height was under and above 3 m, respectively. We tested if there was significantly more ground reflections around measurements with a vegetation height between 0 and 1 m using mixed-effects ANOVA with the forest height category used as the clustering variable. To investigate the last hypothesis, we modeled the effect of the number of LiDAR ground reflections on the difference in elevation between the GNSS and DTM. We also added the distance from the measurement to the nearest reflection as a predictor. We first modeled all locations together and then used mixed-effects models with random slopes and intercepts for each location as a cluster variable. Finally, we created a separate model for measurements where the forest height was under and above 3 m, respectively. Each full model was then compared to a corresponding reduced model without the number of LiDAR ground reflections as a predictor, and values of R2 for both models were compared. Because the distribution of our data was slightly different from the normal distribution, we used robust linear regression.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of monitored variables summarized for all locations.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of monitored variables for individual locations.

3. Results

Descriptive statistics for the monitored variables are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. The values of the difference in elevation between the GNSS and DMR5G did not follow a normal distribution, as indicated by the Shapiro–Wilk test (p-value < 0.05). The calculated RMSE value of the difference between the GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations was 0.46. Of all 706 measurements, this difference was negative only for seven of them, and the largest negative difference was −0.34 m. This means that DEM tends to overestimate elevation values, especially at the bottom of a ditch. We used absolute error values for further analysis, and all predictor variables were scaled by their standard deviation.

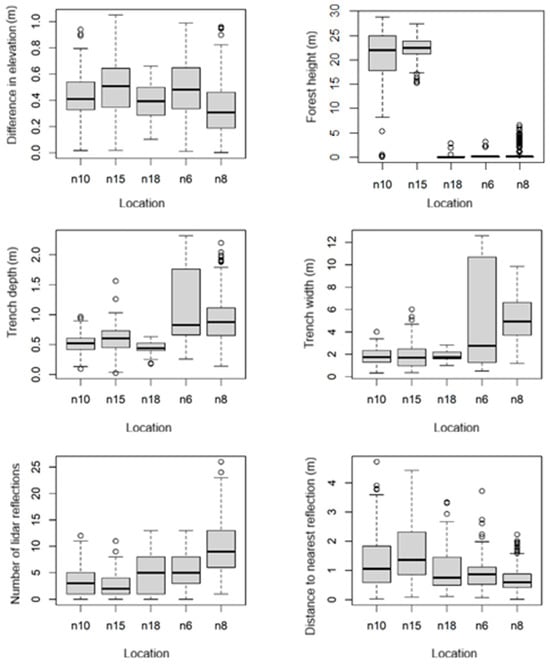

A one-way nonparametric ANOVA (Kruskal–Wallis’s test) confirmed a significant difference in elevation between individual stands (p-value < 0.05). At the same time, it confirmed a significant difference between all locations in all other variables. A graphical comparison of all variables for each location is shown in Figure 3. The most considerable difference in elevation between the GNSS and DTM was between sites N8, where the mean value and RMSE were 0.34 m and 0.39 m, respectively, and N15, where the mean value and RMSE were 0.50 m and 0.54 m, respectively, which is a 47% and 40% increase. The most significant difference in forest height was also observed between these two locations. At location N8, grassy areas and lower pine stands with an average height of under 1 m prevailed. In contrast, at location N15, the entire area was covered with tall vegetation, with an average height of 22.3 m. Duncan’s post hoc test confirmed the largest difference between these two locations in the average values of both the difference in elevation and forest height. The results of Duncan’s post hoc test for the values of difference in elevation and forest height are shown in Table 3. Thus, the location with the largest difference in elevation was also the location with the highest stand.

Figure 3.

Comparison of monitored variables for individual locations. Note: Within each box plot, the black horizontal line indicates the median value, the circle symbols represent outlier data points, and the vertical lines (whiskers) extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range.

Table 3.

Z-statistic values and p-values from Duncan’s post hoc test between individual locations for the difference in elevation between GNSS and DTM, and forest height. Note: The ‘xxx’ entries denote intentionally excluded data points to maintain a non-redundant, single entry per comparison pair in this symmetric matrix.

3.1. The Effect of Forest Height on the Difference Between GNSS- and DTM-Derived Elevations

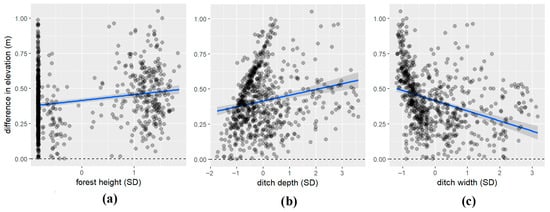

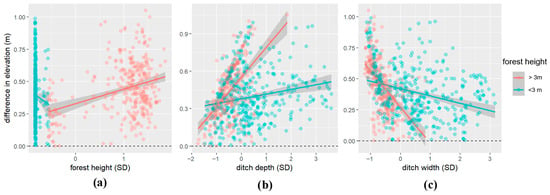

The effect of forest height was verified using a multivariate robust regression model, which allowed for the control of the influence of ditch depth and width, both of which proved to be significant (t = 14.030; p-value < 0.05 and t = −12.929; p-value < 0.05). Forest height was also significant in this model (t = 2.221; p-value < 0.05), but its significance was lower than the other two predictors. The model predicted an increase of 0.17 or a decrease of 0.19 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in ditch depth or ditch width, respectively. In the case of forest height, this value was 0.02 m increase in elevation difference per standard deviation increase. For the full model, the value of R2 was 0.500, while for the reduced model without forest height, the value of R2 was 0.497. Thus, only 0.003 of R2 is attributable to the forest height parameter in this model. Relationships between differences in elevation and predictors are seen in Figure 4a–c. Collinearity between the predictor variables was checked with the Robust Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Moderate collinearity was found for the ditch depth and width, with VIF 2.55 and 2.76, respectively, for the full model and with VIF 2.58 for both the reduced model. More detailed parameters and characteristics for the models in this section are in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 4.

Model of differences between GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations (m) as the dependent variables and (a) forest height (SD), (b) ditch depth (SD), and (c) ditch width (SD) as predictor variables. Note: The gray shading represents the 95% confidence interval for the fitted linear model (blue line), and individual data points are shown as black circles.

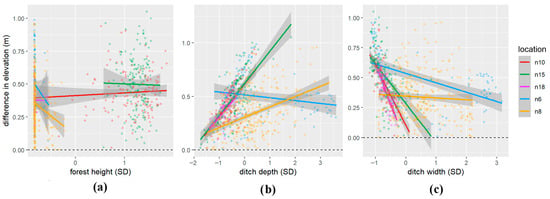

Data visualization revealed visible clusters and anomalies in the data. Therefore, we used mixed-effects models with location as a cluster variable to assess whether these anomalies are tied to data points from individual locations. The first model allowed only the intercept to vary while the slopes were fixed for each cluster (location). This model showed that the ditch depth and width were both significant predictors (t = 18.740; p-value < 0.05 and t = −18.831; p-value < 0.05). The effect of the forest height was not significant in this model (t = −0.160; p-value > 0.05). The model predicted an increase of 0.15 or a decrease of 0.16 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in ditch depth or ditch width, respectively. In the case of forest height, this value was a 0.002 m decrease in elevation difference for every standard deviation increase. For the full model, the value of R2m for just fixed effects was 0.399, R2c for fixed and random effects was 0.433, and ICC was 0.055. For the reduced model without forest height as a predictor, the value of R2m was 0.404, R2c was 0.431, and ICC was 0.045. The next model allowed both the intercept and slopes to vary for all predictors in each cluster (location). This model showed that the effect of the ditch depth and width remained significant (t = 6.657; p-value < 0.05 and t = −4.047; p-value < 0.05). Similarly, the effect of the forest height remained insignificant in this model (t = −0.979; p-value > 0.05). The model predicted an increase of 0.18 or a decrease of 0.26 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in ditch depth or ditch width, respectively. In the case of forest height, this value was 0.05 m decrease in elevation difference for every standard deviation increase. For the full model, the value of R2m was 0.367, R2c was 0.787, and ICC was 0.155. For the reduced model without forest height as a predictor, the value of R2m was 0.450, R2c was 0.736, and ICC was 0.124. Relationships between differences in elevation and predictors separately for each location are shown in Figure 5a–c. Collinearity between predictor variables was checked with the Robust Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Low collinearity with VIF < 2 was found for all the above models. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S2.

Figure 5.

Model of difference between GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations (m) as dependent variables and (a) forest height (SD), (b) ditch depth (SD), and (c) ditch width (SD) as predictor variables separately for each location. Note: The gray shading represents the 95% confidence interval for the fitted linear model (colored lines), and individual data points are shown as colored circles corresponding to their respective locations.

Some of the locations had similar trends. Mainly, location N6 was close to N8, while both had very low average forest heights. Similarly, location N10 was close to N15, and both had an average forest height over 20 m. To investigate this similarity, we created separate models for measurements with forest heights under and above 3 m. The Kruskal–Wallis test showed a statistically significant difference in the difference in DTM-derived elevation compared to the GNSS between measurements in these two categories (p-value < 0.05). Robust multivariate regression models for measurements with forest heights below 3 m did not show a significant effect of forest height (t = −0.924; p-value > 0.05). A significant effect of ditch depth (t = 12.164; p-value < 0.05) and ditch width (t = −12.449; p-value < 0.05) was confirmed, and the model predicted an increase of 0.13 or a decrease of 0.15 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in ditch depth or ditch width, respectively. The value of the full model (R2 = 0.398) was almost identical to that of the reduced model without forest height used as the predictor (R2 = 0.395). The significant influence of forest height was also not confirmed in the model for measurements with a forest height above 3 m (t = 1.549; p-value > 0.05). This model also showed a very significant influence of ditch depth (t = 12.691; p-value < 0.05) and ditch width (t = −8.495; p-value < 0.05), and predicted an increase of 0.24 and a decrease of 0.27 m difference in elevation for each standard deviation increase in ditch depth or ditch width, respectively. A comparison of the value (R2 = 0.704) of the full model with the value (R2 = 0.706) of the reduced model, excluding forest height as a predictor, showed that there is no benefit in adding forest height as a predictor. Relationships between differences in elevation and predictors separately for each forest height category are shown in Figure 6a–c. Collinearity between predictor variables was checked with the Robust Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Low collinearity with VIF < 2 was found for all the above models. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S3.

Figure 6.

Model of differences between GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations (m) as dependent variables and (a) forest height (SD), (b) ditch depth (SD), and (c) ditch width (SD), as predictor variables separately for each forest height category. Note: The gray shading represents the 95% confidence interval for the fitted linear model (colored lines), and individual data points are shown as colored circles corresponding to their respective category.

3.2. The Effect of Forest Height on the Number of LiDAR Ground Reflections

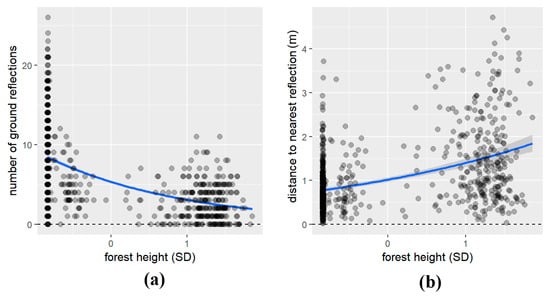

The generalized regression model revealed a significant effect of forest stand height on the number of ground reflections (t = −27.590; p-value < 0.05). The model predicted that for every increase in forest height by a standard deviation, the number of ground reflections will decrease by 42.3% (mean # of reflections = 6.07). The value of R2 was 0.753 for this model. The model for the distance from the measurement to the nearest ground reflection showed a significant effect of forest height (t = 12.640, p-value < 0.05). The model predicted that for every increase in forest height by a standard deviation, the distance to the nearest ground reflection will increase by 37.7% (mean distance to nearest reflection = 1.07 m). The value of R2 was 0.229 for this model. Relationships between dependent variables and forest height as a predictor variable are shown in Figure 7a,b. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S4.

Figure 7.

Model of dependent variables: (a) number of LiDAR ground reflections; (b) distance from GNSS measurement to nearest ground reflection (m) and forest height (SD) as predictor variables. Note: The blue line represents the fitted generalized linear model, and individual data points are shown as black circles.

Generalized mixed-effects regression with a random intercept and slope for each location, which was a cluster variable, showed that the effect of forest height on the number of ground reflections was significant (t = −2.252, p-value < 0.05). Values of R2m for fixed effects and R2c for fixed and random effects for this model were 0.442 and 0.936, respectively. The ICC of this model was 0.122. The model predicted that for every increase in forest height by a standard deviation, the number of ground reflections will decrease by 57.3% (mean # of reflections = 6.07). In the case of distance to the nearest ground reflection, the effect of forest height was also significant (t = 4.052, p-value < 0.05). Values of R2m for fixed effects and R2c for fixed and random effects for this model were 0.165 and 0.192, respectively, which are significantly lower than in the case of the number of ground reflections. The ICC of this model was 0.007. The model predicted that for every increase in forest height by a standard deviation, the distance to the nearest ground reflection will increase by 30.2% (mean distance to nearest reflection = 1.07 m). Relationships between dependent variables and forest height as a predictor variable for each cluster (location) are shown in Figure 8a,b. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S5.

Figure 8.

Model of dependent variables: (a) number of LiDAR ground reflections; (b) distance from GNSS measurement to nearest ground reflection (m) and forest height (SD) as predictor variables separately for each location. Note: The gray shading represents the 95% confidence interval for the fitted generalized linear model (colored lines), and individual data points are shown as colored circles corresponding to their respective locations.

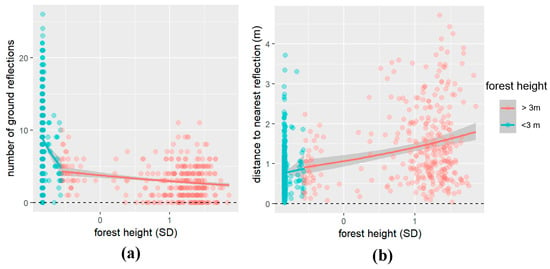

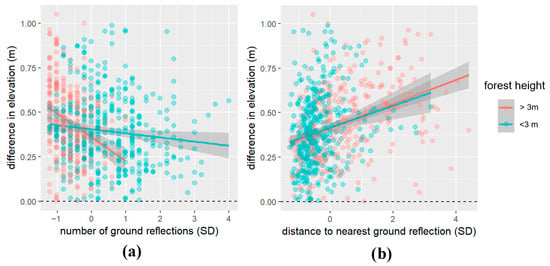

We then carried out generalized regression models separately for measurements with forest heights under and above 3 m. The model for points with stand heights below 3 m showed a significant effect of forest height on the number of reflections (t = −5.314; p-value < 0.05). The value of R2 for this model was 0.085. In the case of distance to nearest ground reflection, the effect of forest height was not significant (t = 0.697, p-value > 0.05). The value of R2 for this model was 0.002. The model for points with stand heights above 3 m showed a significant effect of forest height on the number of reflections (t = −5.195; p-value < 0.05). The value of R2 for this model was 0.088. In the case of distance to nearest ground reflection, the effect of forest height was significant (t = 4.853, p-value < 0.05). The value of R2 of this model was 0.067. Relationships between dependent variables and forest height as a predictor variable for each forest height category are shown in Figure 9a,b. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S6. The overall number of ground reflections seemed to be higher for measurements with a vegetation height between 0 and 1 m. To test this, we used mixed-effects ANOVA, which confirmed a significant difference between this category and the remainder of the dataset (F = 78.344, p-value < 0.05).

Figure 9.

Model of dependent variables: (a) number of LiDAR ground reflections; (b) distance from GNSS measurement to nearest ground reflection (m) and forest height (SD) as predictor variables separately for each forest height category. The gray shading represents the 95% confidence interval for the fitted generalized linear model (colored lines), and individual data points are shown as colored circles corresponding to their respective category.

3.3. The Effect of the Number of Ground Reflections on the Difference in GNSS and DTM Elevations

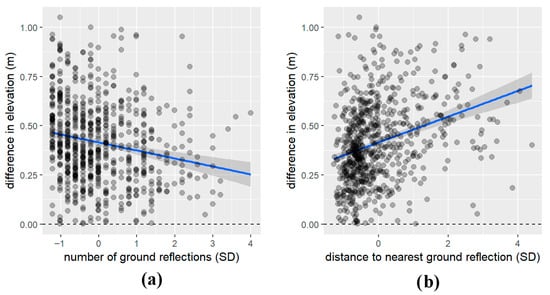

The effect of the number of LiDAR ground reflections on the difference between GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations was verified using a multivariate robust regression model. The number of ground reflections was not significant in this model (t = −0.567; p-value > 0.05). In this model, we also included distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR ground reflection as a second predictor, which proved to be significant (t = 6.715; p-value < 0.05). The model predicted a decrease of 0.01 or an increase of 0.07 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in the number of ground reflections and distance to nearest ground reflection, respectively. For the full model, the value of R2 was 0.114, while for the reduced model without the number of ground reflections as a predictor, the value of R2 was 0.111. Relationships between differences in elevation and both predictors are shown in Figure 10a,b. Collinearity between predictor variables was checked with the Robust Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Very low collinearity was found for both predictors, with a VIF of 1.18 in the full model. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S7.

Figure 10.

Model of differences between GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations (m) as dependent variables and (a) the number of LiDAR ground reflections (SD) and (b) the distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR ground reflection (SD) as a predictor variable. Note: The blue line represents the fitted linear model, and individual data points are shown as black circles.

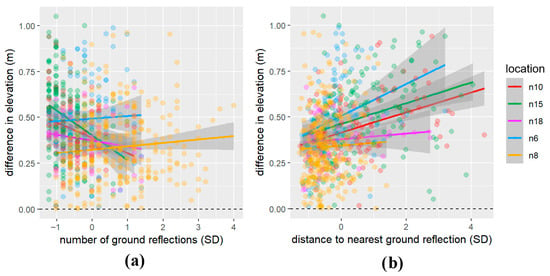

In the next step, we used mixed-effects multivariate robust regression to investigate the effect of the number of LiDAR ground reflections on the difference between the GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations. The second predictor in this model was the distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR ground reflection. The model showed that the number of ground reflections was significant (t = −2.394; p-value < 0.05). Distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR ground reflection proved to be significant (t = 6.763; p-value < 0.05). The model predicted a decrease of 0.02 or an increase of 0.06 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in the number of ground reflections and the distance to the nearest ground reflection, respectively. For the full model, the value of R2m just for fixed effects was 0.060, R2c for fixed and random effects was 0.152, and ICC was 0.098. For the reduced model without the number of ground reflections as a predictor, these values of R2m, R2c, and ICC were 0.061, 0.135, and 0.078, respectively. Relationships between the difference in elevation and both predictors for each location separately are shown in Figure 11a,b. Collinearity between predictor variables was checked with the Robust Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Very low collinearity was found for both predictors with a VIF of 1.18 in the full model. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S8.

Figure 11.

Model of differences between GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations (m) as dependent variables and (a) the number of LiDAR ground reflections (SD) and (b) the distance from GNSS measurement to nearest LiDAR ground reflection (SD) as a predictor variable separately for each location. Note: The gray shading represents the 95% confidence interval for the fitted linear model (colored lines), and individual data points are shown as colored circles corresponding to their respective locations.

The effect of the number of LiDAR ground reflections on the difference between the GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations in each forest height category was verified using the multivariate robust regression model. These models also included the distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR ground reflection as a predictor. In the case of measurements with a forest height below 3 m, the number of ground reflections was not significant (t = −0.711; p-value > 0.05). Distance to the nearest ground reflection proved to be significant (t = 3.389; p-value < 0.05). The model predicted an increase of 0.05 or a decrease of 0.01 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in distance to the nearest ground reflection and number of ground reflections, respectively. For the full model, the value of R2 was 0.037, while for the reduced model without the number of ground reflections as a predictor, the value of R2 was 0.035. Similarly, in the case of measurements with a forest height above 3 m, the number of ground reflections was not significant (t = −0.438; p-value > 0.05), and the distance to the nearest ground reflection proved to be significant (t = 4.311; p-value < 0.05). The model predicted an increase of 0.07 or a decrease of 0.01 m in elevation difference for each standard deviation increase in distance to the nearest ground reflection and number of ground reflections, respectively. For the full model, the value of R2 was 0.174, while for the reduced model without the number of ground reflections as a predictor, the value of R2 was 0.173. Relationships between the difference in elevation and both predictors separately for each forest height category are shown in Figure 12a,b. Collinearity between predictor variables was checked with the Robust Variance Inflation Factor (VIF). Very low collinearity with a VIF < 2 was found for all models above. More detailed parameters and characteristics for models in this section are in Supplementary Table S9.

Figure 12.

Model of differences between GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations (m) as dependent variable and (a) the number of LiDAR ground reflections (SD) and (b) the distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR ground reflection (SD) as a predictor variable separately for each forest height category. The gray shading represents the 95% confidence interval for the fitted generalized linear model (colored lines), and individual data points are shown as colored circles corresponding to their respective category.

4. Discussion

Mapping the network of drainage channels and overall water regime management is currently an important topic. Ditches can be used as a drainage measure in water-affected areas, or conversely, they can be removed, dammed, or otherwise modified in drought-affected areas [2,5,6]. Accurate Digital Terrain Models (DTM) are essential for managing forest drainage networks as a crucial element of water management [4], yet dense canopies and complex micro-topography challenge Airborne Laser Scanning (ALS) precision [45]. The accuracy of digital terrain models (DEMs) remains a critical cross-disciplinary concern addressed through fundamental sensor physics [62] and the modeling of systematic errors within system components [41]. Within forested environments, research has highlighted how seasonal changes and low-stature understory vegetation, such as ferns, can severely degrade DTM accuracy [46]. To mitigate these distortions, specialized filtering that classifies vegetation and non-vegetation echoes based on pulse width and backscatter cross-sections has been shown to significantly improve DTM quality [20]. The applicability of DEMs for hydrological mapping is widely investigated, though typically at a macro-scale. While Zhang et al. [33] introduced correction methods to improve watershed delineation in large, flat regions, our study addresses the finer topographic precision needed for small-scale artificial features. The necessity of high-resolution LiDAR is further supported by Graf et al. [63], who demonstrated that coarse resolution and systematic distortions in global datasets (like SRTM or ASTER) negatively impact flow routing and stream network accuracy. To ensure this precision, Fowler et al. [17] suggested using high-precision terrestrial data to calibrate airborne datasets, a validation strategy mirrored in our assessment of drainage ditch geometry. The influence of forest cover remains a primary variable in vertical accuracy. Hodgson et al. [16] established that land cover type significantly alters error budgets, with deciduous forests and steep slopes, which are common in ditch banks, yielding higher RMSE values than simpler surfaces. Furthermore, Hu et al. [47] found that the interaction between canopy density and flight altitude is a determining factor; when canopy cover exceeds 0.9, elevation errors can double, necessitating lower flight altitudes for accurate understory mapping. In forestry, the accuracy of DEMs is frequently assessed for infrastructure like forest road networks. Kardoš et al. [64] demonstrated that ALS can achieve high precision on hard road surfaces such as asphalt or concrete (RMSE ±0.03–0.04 m). However, the accuracy of the model, which focuses on a network of relatively small drainage ditches, specifically the bottom of the ditches themselves, has not been extensively studied. This study evaluates the vertical accuracy of an ALS-derived DTM specifically within forest drainage ditches. It has been proven that a network of ditches can be identified from DEM without the need for fieldwork [36,37,39,65]. Information about the existence, density, and possibly attributes of the network can be used when adjusting the water regime of specific areas is necessary. Thanks to identification from DEM, it is possible to plan this modification without the need for fieldwork or to identify locations that require more accurate field surveys. This method can thus reduce the personnel and financial demands of the mapping process.

Our results indicate a systematic overestimation of ditch bed elevations (mean error = 0.42 m; RMSE = 0.46 m), which significantly exceeds the 0.30 m threshold reported in the DMR5G technical specifications for forested areas [31]. This consistent positive bias—with only 1% of measurements showing negative errors—confirms that DTMs in drainage networks tend to ‘fill in’ narrow depressions, a trend consistent with the findings by Bonin [66] and Mesa-Mingorance [67]. While vegetation is known to cause generalized elevation overestimation [16,63], our data suggest that for drainage systems, this effect is intensified by the interaction between forest structure and ditch geometry. A critical analysis of site-specific errors reveals that forest height is a primary, but not exclusive, driver of this inaccuracy. For example, the highest error (0.50 m) was observed at location N15, which also featured the greatest average forest height (22.3 m), whereas the lowest error (0.34 m) occurred at N8, where forest height was minimal (0.76 m). However, an important anomaly was observed at site N6; despite a negligible forest height (0.2 m), the error remained high at 0.49 m. This suggests that when forest height is not a limiting factor, the physical dimensions of the ditch itself likely become the dominant constraint. In these cases, the narrowness of the ditch bed relative to the LiDAR pulse footprint may prevent ground penetration regardless of canopy cover. Statistical validation (Kruskal–Wallis and Duncan’s tests) confirms that these differences between locations are significant (Table 3). By comparing site N10 (high forest stand, high error) with N18 (low forest stand, low error), we can conclude that while forest height serves as a proxy for signal obstruction, the DTM’s failure to capture the ditch bed is a multi-factorial issue, where local ditch morphology can override the benefits of an open canopy.

4.1. The Effect of Forest Height on the Difference Between GNSS- and DTM-Derived Elevations

A robust multivariate regression model with forest height, ditch depth, and width as independent explanatory variables showed that the influence of forest height was statistically significant. The value of R2 of this model was 0.500, although a comparison of this complete model with a reduced model excluding forest height as an independent variable and a value of R2 of 0.497 revealed that including forest height as a predictor can only explain a 0.3% additional variability in the elevation difference between the GNSS and DTM. A similar conclusion was reached by Edson [68], who stated that errors in DTM-derived elevation in forest stands do not prevent practical use. We also observed that wider ditches had a significantly lower difference in elevation. This was partly expected, as the ability of DEM to capture topographic structures decreases with the decrease in the size of these structures. This finding is consistent with several studies that have addressed the identification and extraction of various geographic structures from digital terrain models [59,61,63,69]. On the other hand, the elevation difference increased significantly with ditch depth. We observed clustering and anomalies within the dataset.

Therefore, we employed robust mixed-effects regression with location used as a clustering factor. In both random intercepts and random intercepts plus random slopes models, the ditch dimensions remained the only significant predictors, and both ditch depth and width exerted a strong, statistically significant influence on the difference in elevation between the GNSS and DTM. The models predicted an increase in elevation difference as the depth increased and a decrease as the width increased. In contrast, forest height was consistently found to be an insignificant predictor, contributing negligible changes to the elevation error per standard deviation increase. The substantial increase in the conditional R2c of 0.787 compared to the marginal R2m of 0.367 in the full mixed-effects model showed that ditch dimensions explain a significant portion of the global error, but local site-specific characteristics also play a critical role in determining DTM vertical accuracy.

We investigated the structural vegetation height differences between locations characterized by contrasting vegetation profiles to better understand the site-specific clustering that was revealed in the previous analysis. Sites such as N6, N8, and N18 were dominated by low, dense vegetation around or under 1 m on average, likely consisting of shrubs, bushes, and logging residues that create a physically compact barrier near the ground surface. In contrast, sites N10 and N15 comprised mature forest stands with an average height exceeding 20 m, where the understory was less dense, probably due to canopy shading. The Kruskal–Wallis test confirmed a significant difference in elevation error between these two categories; however, subsequent robust multivariate regression showed that absolute forest height remained a non-significant predictor within either group. In the low-vegetation category (under 3 m), ditch depth and width were the sole significant drivers of error, with the model explaining approximately 40% of the variance. The value of R2 of 0.398 of this full model then dropped just by 0.003 after the exclusion of forest, suggesting that within dense understory vegetation, the difference in elevation between the GNSS and DTM does not scale linearly with the specific height of the shrubs. In the mature stand category (above 3 m), the model’s explanatory power increased significantly, denoted by the value of R2 of 0.704, yet forest height, again, remained statistically insignificant. Interestingly, the impact of ditch dimensions was much more pronounced in these tall stands; for every standard deviation increase in ditch width, the overestimation error decreased by 0.274 m, nearly double the effect observed in low-vegetation sites. This suggests a complex interaction where the primary source of error is not the height of the trees themselves, but the different vertical distributions of biomass. In mature stands, the LiDAR laser pulses may penetrate the upper canopy relatively well, but the narrow geometry of the ditch becomes the critical limiting factor [45,46]. Conversely, in low, dense vegetation, the proximity of biomass to the ditch bed creates a consistently high reading [16].

4.2. The Effect of Forest Height on the Number of LiDAR Ground Reflections

Following previous results, which disproved a direct significant relationship between forest stand height and DTM vertical accuracy, we wanted to investigate the density of ground reflections in the source point cloud dataset. We expected that differences in forest height and vegetation structure would influence ground reflection density. Generalized regression models confirmed that forest height was a powerful predictor of LiDAR ground reflection density. For every standard deviation increase in forest height, the number of ground reflections decreased by 42.3% (mean # of reflections = 6.07), explaining a high degree of variance (R2 = 0.753). Conversely, the distance to the nearest ground reflection increased by 37.7% (mean distance to nearest reflection = 1.07 m) (R2 = 0.229). These findings demonstrated that as forest stands mature and the height increases, the ground surface is represented by a progressively sparser point cloud [46]. This likely reflects the cumulative probability of LiDAR laser pulses being intercepted by the vertical biomass of the canopy [47].

Next, we used mixed-effects models with random intercepts and slopes and location as a cluster variable to account for the diverse structural characteristics of different research locations. The effect of forest height on the number of ground reflections remained highly significant, with a predicted decrease of 57.3% per standard deviation increase (mean # of reflections = 6.07). The substantial gap between the marginal R2m of 0.442 and the conditional R2c of 0.936 showed that while forest height was a dominant global predictor, site-specific variables—such as species composition or stand density—accounted for nearly half of the remaining variance. In contrast, the distance to the nearest ground reflection showed a much lower conditional R2c of 0.192, suggesting that the spatial distribution of these sparse points is more random and less tied to specific site characteristics than the total count of reflections.

Analysis of GNSS measurements, divided into two categories separated by a forest height of 3 m, provided critical insight into why point density varies so dramatically. A mixed-effects ANOVA with the forest height category as a cluster variable highlighted that the 0–3 m height class contained a significantly higher number of ground reflections than the remainder of the data. These results lead to the hypothesis that in adult forest stands, the lower ground reflection density may be a result of the classification algorithms correctly identifying and removing reflections from a high, distinct canopy [46,51]. Conversely, the high density of ground reflections in areas with shrubs, understory vegetation, and logging residues may indicate a systematic failure of classification algorithms. In these low-vegetation environments, the vertical separation between the ground and the vegetation surface is often smaller than the laser’s footprint or the algorithm’s filtering threshold [52]. Consequently, reflections from the surface of dense understory or logging debris are likely misclassified as true ground returns [49,50]. This suggests that the higher resolution found in low vegetation may actually be composed of false ground points. On the other hand, a lower resolution in adult forests represents a more accurately filtered, albeit sparser, true ground reflections. This potential for misclassification in low vegetation could be an explanation for the low value of forest height as a predictor for the actual vertical accuracy of DTM.

4.3. The Effect of the Number of Ground Reflections on the Difference in GNSS and DTM Elevations

In the final part of our analysis, we wanted to determine if the reduction in ground reflection density caused by forest cover directly translates into a difference between the GNSS- and DTM-derived elevations. Multivariate robust regression revealed that the total number of ground reflections was a non-significant predictor of elevation error in most models. In contrast, the distance to the nearest ground reflection proved to be a consistently significant driver of vertical errors across all analyses. Specifically, for every standard deviation increase in distance, the model predicted an increase in elevation error of up to 0.071 m. This suggests that the spatial distribution and proximity of ground points to a given measurement were more critical for DTM vertical accuracy than the sheer volume of points available for interpolation. When accounting for site-specific variability via mixed-effects modeling, the number of ground reflections became statistically significant, yet its practical impact remained marginal. The predicted decrease in error was only 0.024 m per standard deviation increase in point count, and the exclusion of this variable from the model resulted in nearly identical R2c values of 0.152 and 0.135, respectively. These results confirmed that while a higher density of points theoretically improves the surface, the effect is statistically overwhelmed by the distance to the nearest ground. A similar conclusion was made by Li in [70]. Categorical analysis by forest height category further reinforced this finding. In both low-vegetation sites (<3 m) and mature forest stands (>3 m), the distance to the nearest ground reflection was the only significant predictor. Interestingly, the explanatory power of the model was higher in mature stands compared to low-vegetation areas, indicated by the values of R2 of 0.174 and 0.037, respectively. This was likely because mature stands have larger gaps between reflections, making the DTM more reliant on interpolation over distance. Collectively, these results explain the paradox identified earlier: while forest stands reduce the number of ground reflections, this decrease does not substantially degrade DTM accuracy as long as the spatial distribution of the points remains sufficient to resolve the terrain.

4.4. Practical Implications

The findings of this study provide critical insights into the practical applicability and limitations of ALS-derived DTMs for managing forest drainage networks, specifically regarding a reduction in reliance on intensive field surveys. A primary implication for the identification of drainage ditches is the shift in focus from canopy characteristics to ditch geometry. Because forest height was disproven as a direct driver of vertical error, practitioners can proceed with ALS mapping in various stand ages with relative confidence. However, the consistent positive vertical bias, averaging 0.42 m, can affect the reliability of automated identification. Without applying systematic vertical corrections, narrow ditches may appear as shallow depressions or be completely masked by interpolation, leading to an underestimation of the drainage network density. The reliability of this identification is strictly constrained by the interplay between ditch geometry and ground point density. In the context of this study, the average ditch width was 3.67 m, and these ditches were mostly identifiable. Large ditches over 5 m, with some up to 10 m wide, seemed to be consistently captured even under forest cover. Conversely, smaller ditches (0.5 to 1.0 m wide) were almost impossible to identify even in open areas without vegetation and remained. This occurs because the ground-return densities for large-scale elevation models are relatively low compared, for example, to data acquired with UAV (drone-based). In our study, the point cloud density ranged from 0.14 to 0.52 points/m2, depending on the vegetation cover. At these densities, the spatial sampling frequency is insufficient to guarantee a laser strike within a 0.5 m wide feature. Our results indicate that with a ground density below 0.6 points/m2, the system cannot reliably resolve drainage features much narrower than 2 m. Regarding hydrological functionality, the observed overestimation of ditch bed elevations poses a direct risk to water management modeling. In low-slope forest environments, a 0.4 m vertical error can exceed the actual hydraulic gradient of the ditch bed, potentially causing hydrological models to predict incorrect flow directions or erroneously identify functional ditches as stagnant. Consequently, raw DTM data cannot be used reliably for assessing ditch capacity or network condition without a post-processing stage that accounts for these systematic errors. To improve the usability of DTMs for hydrological purposes, we suggest implementing correction algorithms that adjust ditch bed elevations based on local geometric profiles. Finally, this study offers a framework for optimizing mapping workflows by using ditch width as a decisive criterion for determining the appropriate methodology. We propose that for wide, well-defined drainage features, ALS-derived DTMs provide sufficient accuracy for some management and mapping tasks, significantly reducing the need for ground-based surveys. Conversely, for narrow ditches—where we identified the highest vertical errors—field-based GNSS or total station measurements remain essential to capture true bed elevations. By prioritizing field work for narrow features while relying on corrected ALS data for larger channels, forest managers can maximize resources while maintaining the high-fidelity terrain models necessary for effective forest water management and drainage maintenance.

4.5. Study Limitations

This study has a limited scope; in particular, there is a relative gap in the data for average forest heights between approximately 8 and 18 m. There is also a lack of information regarding vegetation density for our research locations. Unfortunately, we did not have data describing the characteristics mentioned. This can pose a problem when interpreting different trends in low forests with a height of less than 3 m, where the relationship of DTM vertical accuracy and predictor variables is different compared to the remainder of the data. In connection with this problem, we lack data on whether and when logging occurred at the research sites. We also did not have information on whether damage to ditches caused by heavy machinery had been repaired and whether logging residues had been removed before the DEM of a specific location was acquired. To maintain model parsimony and ensure direct interpretability of results, we employed linear regression as the primary analytical framework. This decision was based on the objective of describing general trends across diverse forest stands and to avoid the significant risk of overfitting inherent in higher-order polynomials, particularly given the high variance of ALS data. However, we acknowledge that this linear approach is a simplification. Our findings, supported by mixed-effects ANOVA, suggest that the relationship between vegetation height and DTM error may follow a nonlinear threshold or ‘step-function’—particularly in the 0–1 m height range—rather than a continuous linear slope. Consequently, while our models effectively capture the direction and significance of the observed impacts, they may not fully account for the complex, nonlinear physical interactions occurring at the extremes of vegetation density. However, despite its limitations, this study can contribute to a better understanding of the accuracy and applicability of digital terrain models in forest environments. We believe that it can provide experts with adequate information when considering an approach using this technology and can serve as a basis for further research.

5. Conclusions

This study focused on the vertical accuracy of a digital terrain model (DTM) generated in a forest environment using aerial laser scanning (ALS). We investigated whether LiDAR reflection density is affected by forest height, utilizing it as a primary proxy metric for forest stand structure, density, and maturity. While forest height is not the direct physical cause of signal attenuation, it serves as a highly accessible indicator of canopy closure and biomass volume, which represent the actual mechanisms—such as pulse interception and multi-pathing—that impede ground penetration. Given that Canopy Height Models (CHMs) are among the most standard and readily available LiDAR products, our analysis sought to determine how this specific metric impacts ground reflection density and, subsequently, the vertical accuracy of the resulting DTM, with a focused assessment of drainage ditch beds The analysis revealed that the root mean square error (RMSE) of the DTM-derived elevation was 0.46 m. This represents an increase of approximately 54.7% compared to the 0.30 m accuracy value specified in the DTM’s technical report for forested areas [31]. The mean elevation error was 0.42 m, and the error was negative for only 7 out of 706 total measurements. This indicates a strong tendency for DTM to overestimate the elevation of the ditch bed. A statistically significant influence of vegetation height on DTM vertical accuracy was demonstrated in a simple regression. However, the predicted error was negligible in relation to the absolute value of the elevation error at the bottom of the ditches. When using multiple regression and accounting for the influence of ditch dimensions, the statistically significant impact of forest height was not demonstrated.

The dimensions of the ditch itself, especially its width, proved to be the most significant indicator of the resulting error. Narrow ditches showed a much greater error than wide ditches. Vegetation height significantly affected the DEM’s resolution at a given location. The number of LiDAR ground reflections showed a statistically significant negative correlation with vegetation height. Analyzing each location separately showed a steep negative correlation for locations with small or no forest stands and almost no correlation for locations with high forest stands. A similar relationship was revealed in the case of the forest height category. Mixed-effects ANOVA confirmed that there are significantly more ground reflections around GNSS measurements with a vegetation height between 0 and 1 m when compared to the rest of the data. The relationship between forest height and distance from a GNSS measurement to the nearest ground reflection showed strong similarities, with the key distinction being a positive correlation rather than a negative one. A statistically significant effect of the number of LiDAR ground reflections in proximity to the GNSS measurement and the resulting DTM vertical accuracy was not demonstrated. However, a significant effect was shown for the distance from the GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR ground reflection.

We concluded that adult forest stands can lead to a decrease in ground reflection density compared to open fields. Surprisingly, this decrease in resolution did not affect the vertical accuracy of the DTM. Therefore, the presence and height of the forest stand did not have any major effect on the accuracy of a DTM-derived elevation. These findings suggest that while ALS is effective for general forest topography and mapping drainage infrastructure, its application may require specific corrections for ditch dimensions rather than the vegetation height alone to mitigate systematic overestimation of ditch bed elevations. Building on these findings, future research should prioritize the development of geometry-based correction algorithms that utilize ditch width and bank slope as primary variables to mitigate systematic vertical overestimation. While forest height impacted point density without significantly degrading DTM accuracy, the resilience of interpolation models to low ground-return densities suggests that deep learning architectures, such as Graph Neural Networks, could be trained to reconstruct narrow ditch beds more effectively than standard interpolation. Furthermore, investigating the hydrological propagation of these errors—specifically how a ~ 0.400 m vertical bias affects flow-accumulation models and catchment runoff predictions—is essential for improving forest water management. Finally, integrating high-density UAV-LiDAR with traditional ALS data could help determine if increased point density can overcome the geometric challenges of narrow drainage features where satellite-scale ALS currently fails.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17020162/s1, Figure S1: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N6 research site; Figure S2: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N6 research site; Figure S3: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N6 research site; Figure S4: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N6 research site; Figure S5: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N8 research site; Figure S6: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N8 research site; Figure S7: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N8 research site; Figure S8: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N8 research site; Figure S9: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N8 research site; Figure S10: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N8 research site; Figure S11: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N10 research site; Figure S12: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N10 research site; Figure S13: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N10 research site; Figure S14: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N10 research site; Figure S15: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N10 research site; Figure S16: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N15 research site; Figure S17: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N15 research site; Figure S18: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N15 research site; Figure S19: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N15 research site; Figure S20: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N15 research site; Figure S21: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N18 research site; Figure S22: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N18 research site; Figure S23: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N18 research site; Figure S24: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N18 research site; Figure S25: A representative view of a ditch appearance at the N18 research site; Table S1: Summary table of robust regression models used in chapter 3.1. The effect of forest height on difference between GNSS and DTM derived elevation; Table S2: Summary table of mixed effects regression models used in chapter 3.1. The effect of forest height on difference between GNSS and DTM derived elevation; Table S3: Summary table of robust regression models separate for each forest height category used in chapter 3.1. The effect of forest height on difference between GNSS and DTM derived elevation; Table S4: Summary table of generalized regression models used in chapter 3.2. The effect of forest height on number of LiDAR ground reflections; Table S5: Summary table of generalized mixed effects regression models used in chapter 3.2. The effect of forest height on number of LiDAR ground reflections; Table S6: Summary table of generalized regression models separate for each forest height category used in chapter 3.2. The effect of forest height on number of LiDAR ground reflections; Table S7: Summary table of robust regression models used in chapter 3.3. The effect of the number of ground reflections on difference in GNSS and DTM elevation; Table S8: Summary table of mixed effects regression models used in chapter 3.3. The effect of the number of ground reflections on difference in GNSS and DTM elevation; Table S9: Summary table of robust regression models separate for each forest height category used in chapter 3.3. The effect of the number of ground reflections on difference in GNSS and DTM elevation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.Z., M.D. and V.M.; methodology, M.D. and K.Z.; software, M.D.; validation, K.Z. and M.J.; formal analysis, M.D. and A.T.; investigation, M.D. and V.M.; resources, M.D., A.T. and K.Z.; data curation, M.D. and A.T.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D. and K.Z.; writing—review and editing, K.Z., M.J. and V.M.; visualization, M.D., A.T. and V.M.; supervision, K.Z. and V.M.; project administration, V.M., M.J., M.D. and K.Z.; funding acquisition, M.D., K.Z. and M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by grants from the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague: IGA FLD ČZU A 24/25 - 43160/1312/3161 (Specifics of the use of laser scanning in the field of torrent and gully control); and The Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic: NAZV, project number QL25020051 (The forest road network influence on runoff from forests in changing climatic conditions).

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are openly available in [zenodo] at [https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17612063].

Acknowledgments

The author team would like to thank our colleague Dana Tollingerová for consulting and help with surveying and accuracy, and our colleague Ondřej Nuhlíček for consulting on the translation of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DEM | Digital elevation model |

| DTM | Digital terrain model |

| DSM | Digital surface model |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GPS | Global positioning systems |

| LiDAR | Light detection and ranging |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| z_DELTA | The difference between the elevation derived from the GNSS measurement and DEM |

| f_HEIGHT | Height of the forest stand nearest to a particular GNSS measurement |

| d_WIDTH | Width of amelioration ditch in place of a particular GNSS measurement |

| d_DEPTH | Depth of amelioration ditch in place of a particular GNSS measurement |

| r_COUNT | Number of LiDAR reflections around a particular GNSS measurement |

| r_DIST | Distance from a particular GNSS measurement to the nearest LiDAR reflection |

| l_NAME | Name of location |

References

- Andréassian, V. Waters and Forests: From Historical Controversy to Scientific Debate. J. Hydrol. 2004, 291, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vose, J.M.; Sun, G.; Ford, C.R.; Bredemeier, M.; Otsuki, K.; Wei, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Forest Ecohydrological Research in the 21st Century: What Are the Critical Needs? Ecohydrology 2011, 4, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Forner, A.; Cuesta, B.; Valladares, F. Species-Specific Water Use by Forest Tree Species: From the Tree to the Stand. Agric. Water Manag. 2012, 114, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paavilainen, E.; Päivänen, J. Peatland Forestry: Ecology and Principles; Ecological Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Päivänen, J.; Sarkkola, S. The Effect of Thinning and Ditch Net-Work Maintenance on the Water Table Level in a Scots Pine Stand on Peat Soil. Suo 2000, 51, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Herzon, I.; Helenius, J. Agricultural Drainage Ditches, Their Biological Importance and Functioning. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 1171–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riesinger, P.; Herzon, I. Variability of herbage production in mixed leys as related to ley age and environmental factors: A farm survey. Agric. Food Sci. 2008, 17, 394–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollinger, J.; Dagès, C.; Bailly, J.-S.; Lagacherie, P.; Voltz, M. Managing Ditches for Agroecological Engineering of Landscape. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 999–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, O.; Zachar, D. Forest Amelioration; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ahti, E.; Päivänen, J. Response of Stand Growth and Water Table Level to Maintenance of Ditch Networks within Forest Drainage Areas. In Northern Forested Wetlands; Trettin, C.C., Jurgensen, M.F., Grigal, D.F., Gale, M.R., Jeglum, J.K., Eds.; Routledge: New York City, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 449–457. [Google Scholar]

- Koivusalo, H.; Ahti, E.; Laurén, A.; Kokkonen, T.; Karvonen, T.; Nevalainen, R.; Finér, L. Impacts of Ditch Cleaning on Hydrological Processes in a Drained Peatland Forest. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2008, 12, 1211–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, T.G.R.; Pervez, N.; Ibrahim, U.; Houts, S.E.; Pandey, G.; Alla, N.K.R.; Hsia, A. Standalone and RTK GNSS on 30,000 km of North American Highways. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation, Miami, FL, USA, 11 October 2019; pp. 2135–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Bakuła, M.; Oszczak, S.; Pelc-Mieczkowska, R. Performance of RTK Positioning in Forest Conditions: Case Study. J. Surv. Eng. 2009, 135, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]