Topographic Heterogeneity Drives the Functional Traits and Stoichiometry of Abies georgei var. smithii Bark in the Sygera Mountains, Southeast Tibet

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Trees on the shady slope will develop thicker bark to improve insulation against low temperatures, while trees on the sunny slope will develop denser bark to reduce water loss and resist radiation stress.

- (2)

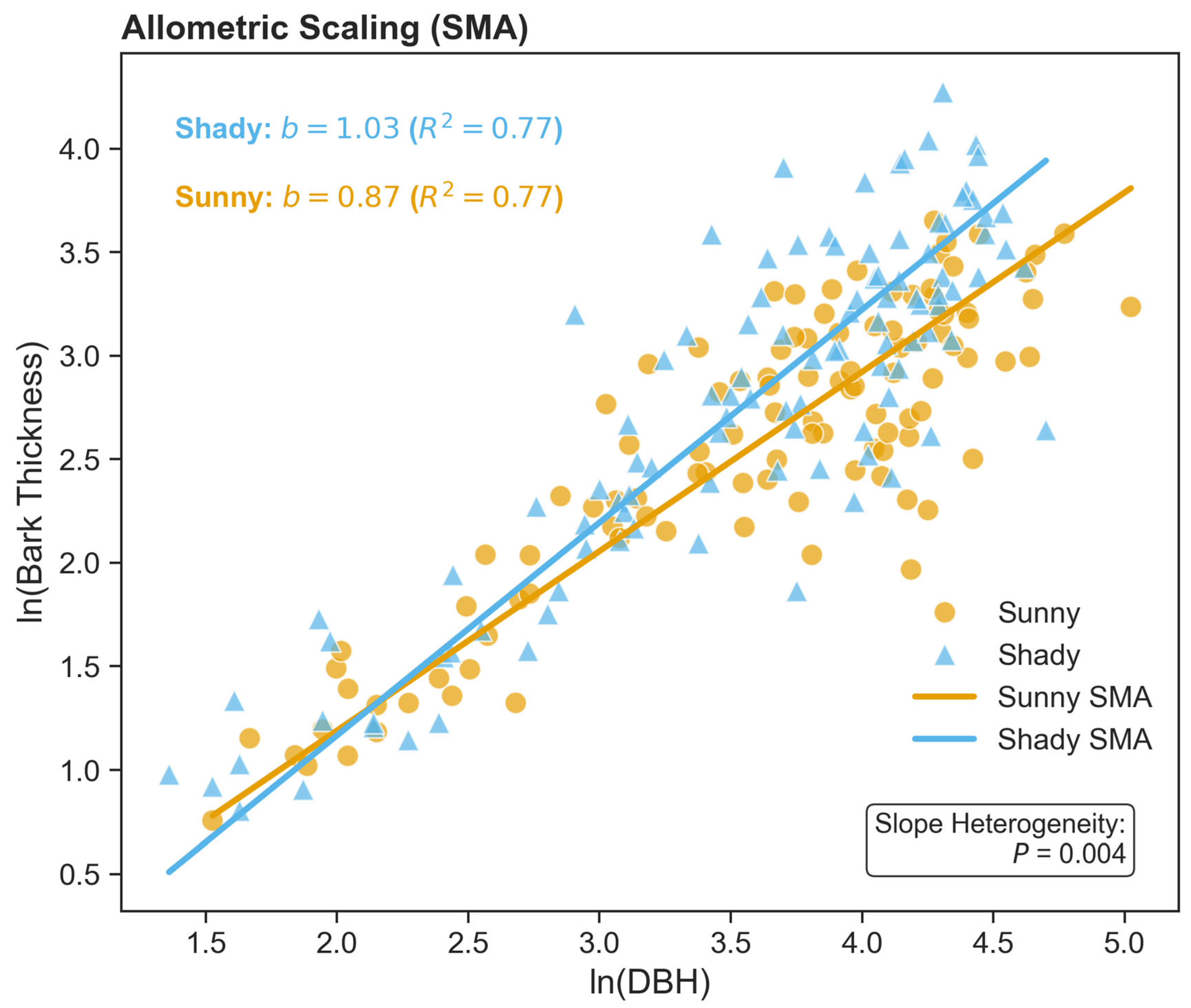

- The allometric scaling relationship for bark thickness is not fixed but flexible; specifically, we expect isometric scaling () on shady slopes for thermal maintenance and allometric scaling () on sunny slopes for hydraulic safety.

- (3)

- Bark stoichiometric traits will change from a resource-acquisitive pattern (high nitrogen) on the shady slope to a conservative/defensive pattern (high C/N ratio) on the sunny slope, primarily due to microclimatic differences rather than soil nutrients.

2. Materials and Methods

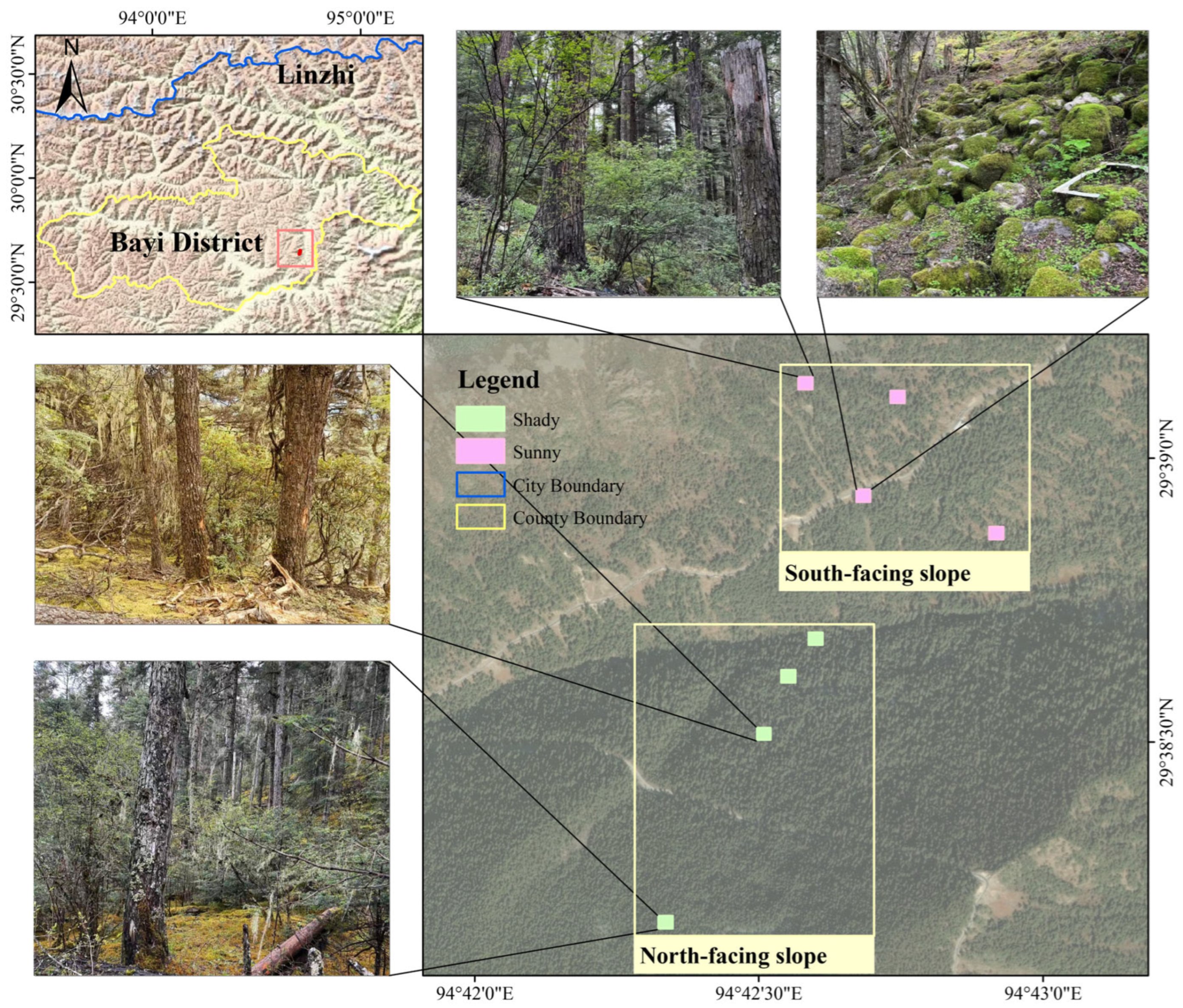

2.1. Study Area and Sampling

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. AI Tool Usage

3. Results

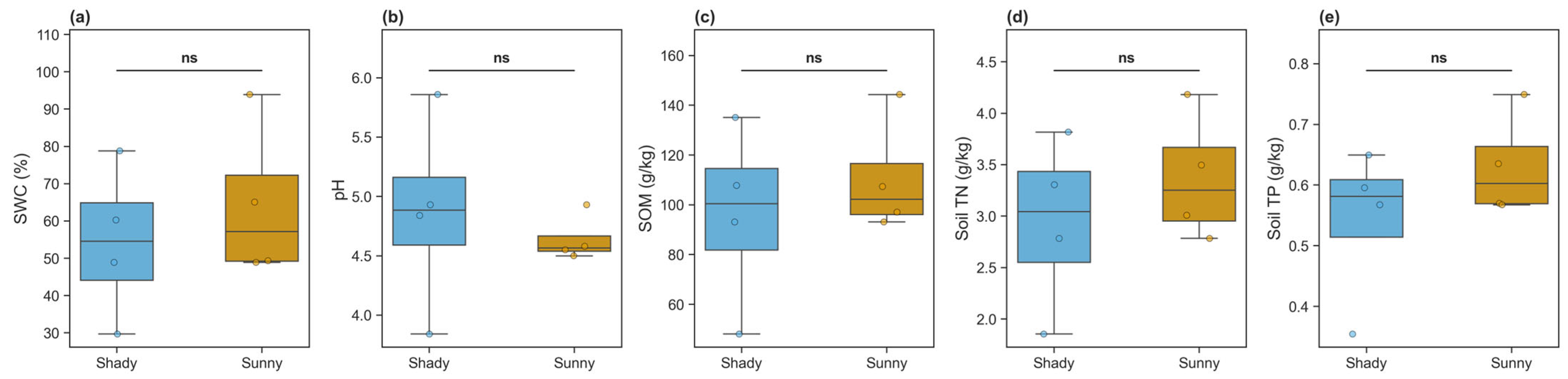

3.1. Variations in Soil Physicochemical Properties

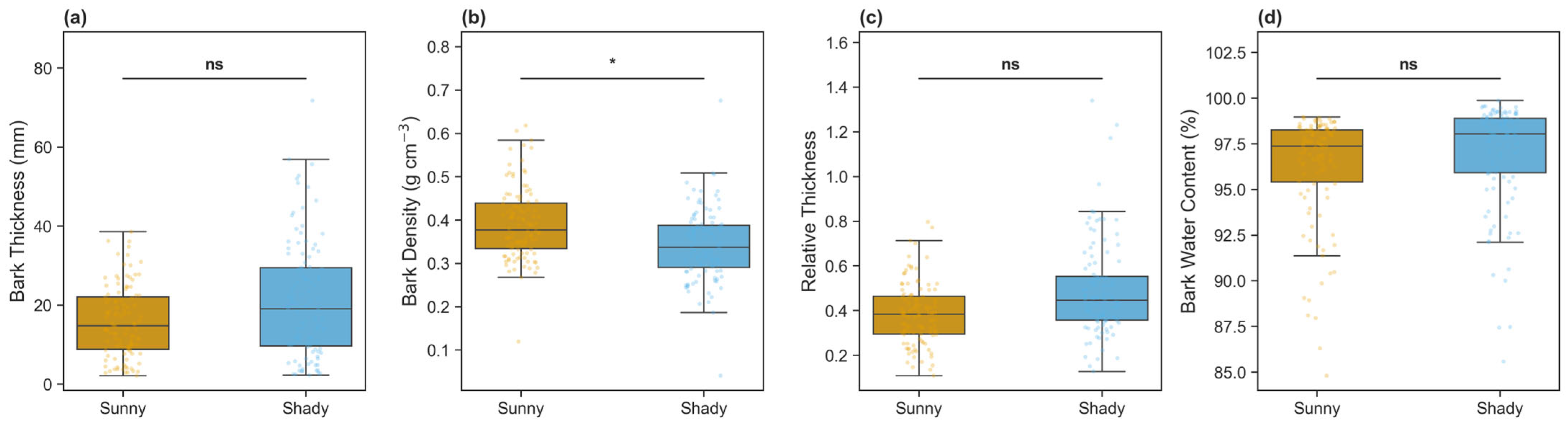

3.2. Variations in Bark Physical and Stoichiometric Traits

3.3. Allometric Scaling of Bark Thickness

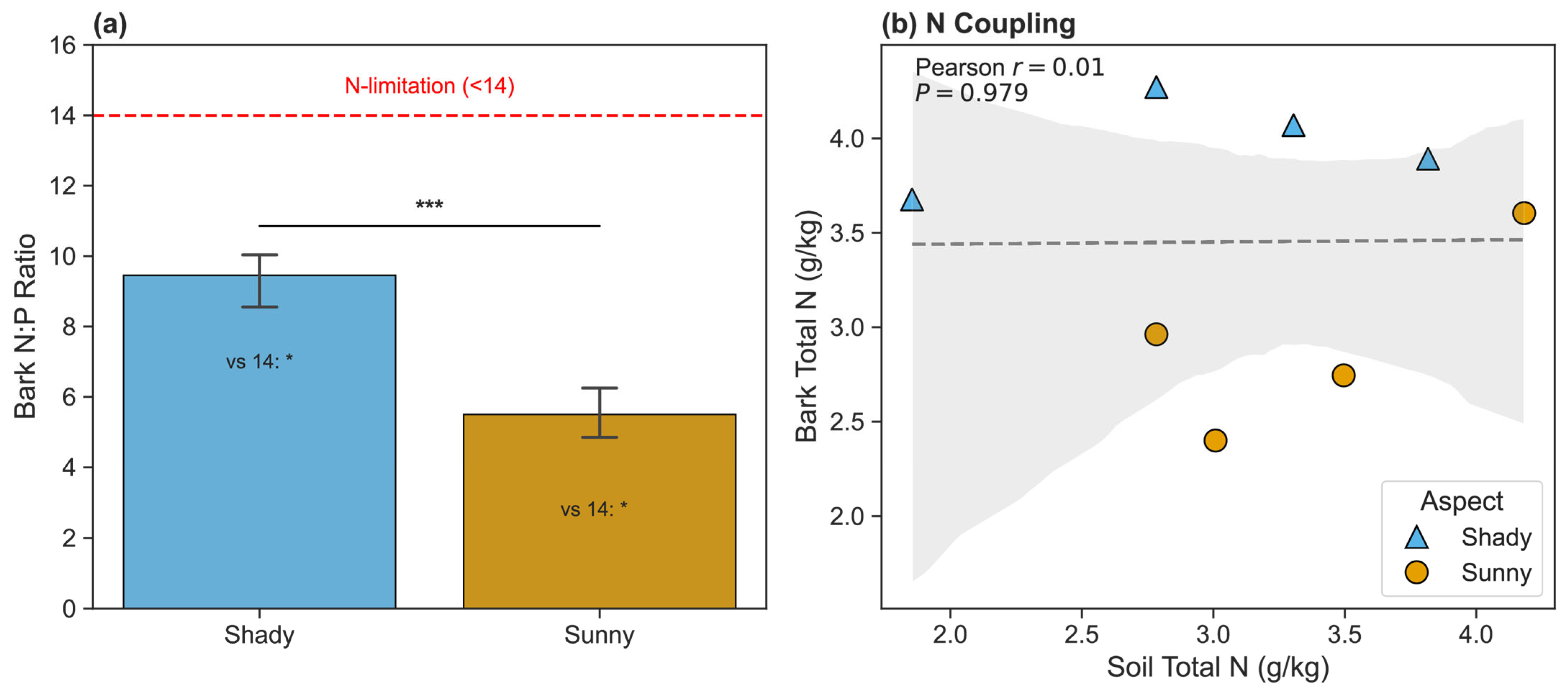

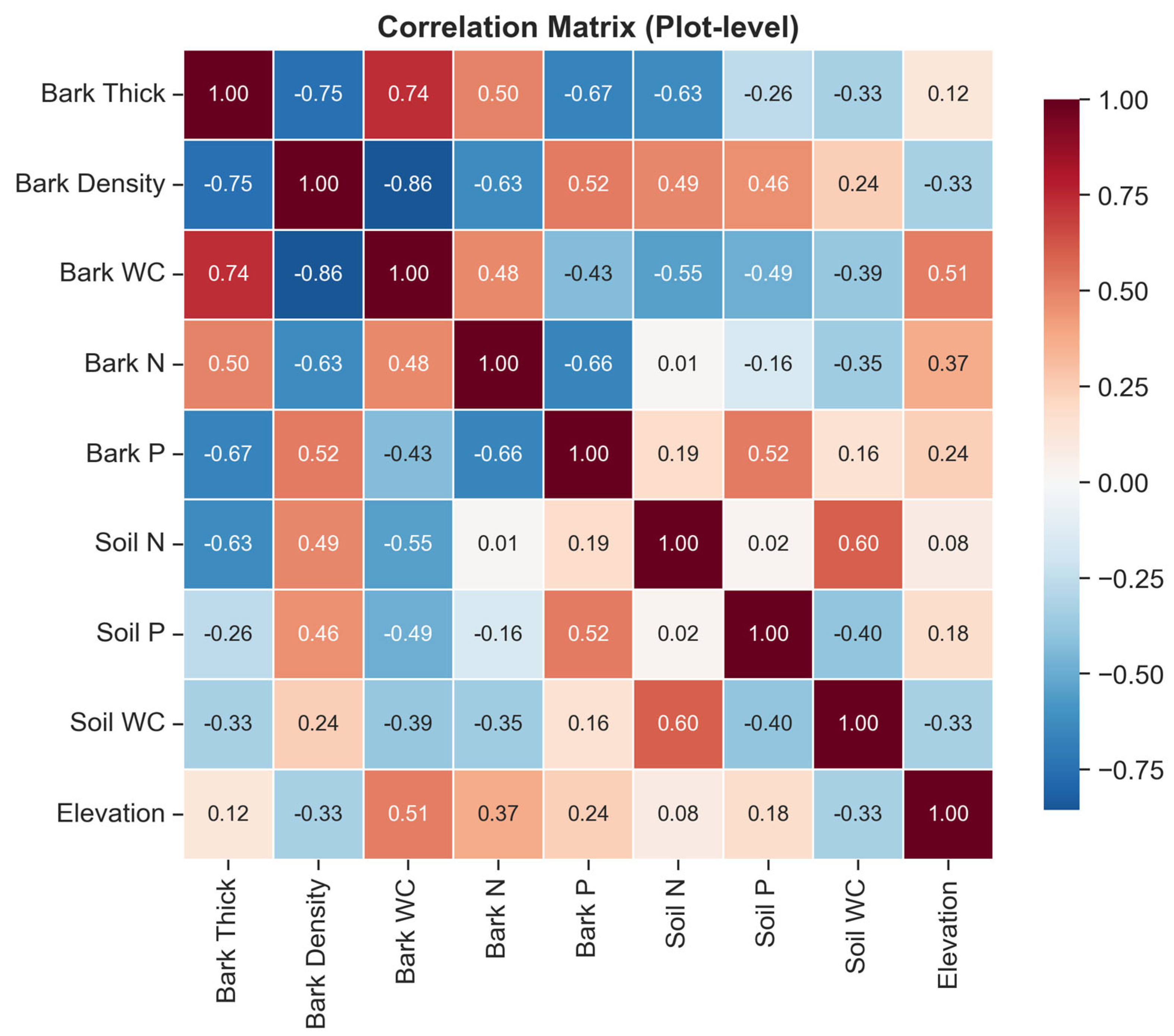

3.4. Correlations Between Soil and Bark Traits

4. Discussion

4.1. Trade-Offs in Bark Physical Architecture: Insulation vs. Hydraulic Safety

4.2. Stoichiometric Plasticity and Resource Allocation

4.3. Divergent Allometric Scaling and Ontogenetic Shifts in Bark Allocation

4.4. Decoupling of Soil and Bark Traits: Ecological Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Violle, C.; Navas, M.-L.; Vile, D.; Kazakou, E.; Fortunel, C.; Hummel, I.; Garnier, E. Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos 2007, 116, 882–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.J.; Reich, P.B.; Westoby, M.; Ackerly, D.D.; Baruch, Z.; Bongers, F.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Chapin, T.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Diemer, M.; et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 2004, 428, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, J.A.; Gleason, S.; Méndez-Alonzo, R.; Chang, Y.; Westoby, M. Bark functional ecology: Evidence for tradeoffs, functional coordination, and environment producing bark diversity. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschi, V.R.; Krokene, P.; Christiansen, E.; Krekling, T. Anatomical and chemical defenses of conifer bark against bark beetles and other pests. New Phytol. 2005, 167, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, L.; McNeil, A.; Hurtado, V.-H.; Prins, H.H.T.; Putz, F.E. Bark traits and life-history strategies of tropical dry- and moist forest trees. Funct. Ecol. 2014, 28, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körner, C. A re-assessment of high elevation treeline positions and their explanation. Oecologia 1998, 115, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valladares, F.; Matesanz, S.; Guilhaumon, F.; Araújo, M.B.; Balaguer, L.; Benito-Garzón, M.; Cornwell, W.; Gianoli, E.; van Kleunen, M.; Naya, D.E.; et al. The effects of phenotypic plasticity and local adaptation on forecasts of species range shifts under climate change. Ecol. Lett. 2014, 17, 1351–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennie, J.; Huntley, B.; Wiltshire, A.; Hill, M.O.; Baxter, R. Slope, aspect and climate: Spatially explicit and implicit models of topographic microclimate in chalk grassland. Ecol. Model. 2008, 216, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.; Deslauriers, A.; Griçar, J.; Seo, J.-W.; Rathgeber, C.B.K.; Anfodillo, T.; Morin, H.; Levanic, T.; Oven, P.; Jalkanen, R. Critical temperatures for xylogenesis in conifers of cold climates. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2008, 17, 696–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niklas, K.J. Plant allometry: Is there a grand unifying theory? Biol. Rev. 2004, 79, 871–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.C.; Enquist, B.J. Consistency between an allometric approach and optimal partitioning theory in global patterns of plant biomass allocation. Funct. Ecol. 2007, 21, 713–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elser, J.J.; Fagan, W.F.; Denno, R.F.; Dobberfuhl, D.R.; Folarin, A.; Huberty, A.; Interlandi, S.; Kilham, S.S.; McCauley, E.; Schulz, K.L.; et al. Nutritional constraints in terrestrial and freshwater food webs. Nature 2000, 408, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ågren, G.I. Stoichiometry and Nutrition of Plant Growth in Natural Communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2008, 39, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordoñez, J.C.; Van Bodegom, P.M.; Witte, J.-P.M.; Wright, I.J.; Reich, P.B.; Aerts, R. A global study of relationships between leaf traits, climate and soil measures of nutrient fertility. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2009, 18, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.; Wang, Y.; Eckstein, D.; Luo, T. Little change in the fir tree-line position on the southeastern Tibetan Plateau after 200 years of warming. New Phytol. 2011, 190, 760–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farjon, A. A Handbook of the World’s Conifers; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mátyás, C.; Beran, F.; Dostál, J.; Čáp, J.; Fulín, M.; Vejpustková, M.; Božič, G.; Balázs, P.; Frýdl, J. Surprising Drought Tolerance of Fir (Abies) Species between Past Climatic Adaptation and Future Projections Reveals New Chances for Adaptive Forest Management. Forests 2021, 12, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, E.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Liu, B.; Shao, X. Growth variation in Abies georgei var. smithii along altitudinal gradients in the Sygera Mountains, southeastern Tibetan Plateau. Trees 2010, 24, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Guo, L. Variation and Driving Mechanisms of Bark Thickness in Larix gmelinii under Surface Fire Regimes. Forests 2024, 15, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.D. Soil and Agricultural Chemistry Analysis; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental algorithms for scientific computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Koerselman, W.; Meuleman, A.F.M. The vegetation N:P ratio: A new tool to detect the nature of nutrient limitation. J. Appl. Ecol. 1996, 33, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warton, D.I.; Wright, I.J.; Falster, D.S.; Westoby, M. Bivariate line-fitting methods for allometry. Biol. Rev. 2006, 81, 259–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Jia, J.; Yu, D.; Lewis, B.J.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, L. Effects of climate change on biomass carbon sequestration in old-growth forest ecosystems on Changbai Mountain in Northeast China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 300, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Nie, H.; Yi, J.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Ren, Q.; Li, S.; Fei, Y.; Hu, K.; Nan, X.; et al. Characteristics of Soil Moisture Response to Rainfall under Different Land Use Patterns at Red Soil Region in Southern China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 6813–6826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G. Bark thickness and fire regime. Funct. Ecol. 2015, 29, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmeier, H. Functional traits explaining plant responses to past and future climate changes. Flora 2019, 254, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.K.; Germino, M.J.; Hancock, T.E.; Johnson, D.M. Another perspective on altitudinal limits of alpine timberlines. Tree Physiol. 2003, 23, 1101–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chave, J.; Coomes, D.; Jansen, S.; Lewis, S.L.; Swenson, N.G.; Zanne, A.E. Towards a worldwide wood economics spectrum. Ecol. Lett. 2009, 12, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, F.G.; Bucci, S.J.; Goldstein, G.; Meinzer, F.C.; Franco, A.C.; Miralles-Wilhelm, F. Biophysical properties and functional significance of stem water storage tissues in Neotropical savanna trees. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, K.; André, M.-F. New insights into rock weathering from high-frequency rock temperature data: An Antarctic study of weathering by thermal stress. Geomorphology 2001, 41, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, G. Ecological Stoichiometry: Biology of Elements from Molecules to the Biosphere. J. Plankton Res. 2003, 25, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Kattge, J.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Wright, I.J.; Lavorel, S.; Dray, S.; Reu, B.; Kleyer, M.; Wirth, C.; Colin Prentice, I.; et al. The global spectrum of plant form and function. Nature 2016, 529, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, J.P.; Chapin, F.S.; Klein, D.R. Carbon/Nutrient Balance of Boreal Plants in Relation to Vertebrate Herbivory. Oikos 1983, 40, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B. The world-wide ‘fast–slow’ plant economics spectrum: A traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, J. Allocation, plasticity and allometry in plants. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004, 6, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, V. The bark of trees: Thermal properties, microclimate and fauna. Oecologia 1986, 69, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacke, U.G.; Sperry, J.S.; Pockman, W.T.; Davis, S.D.; McCulloh, K.A. Trends in wood density and structure are linked to prevention of xylem implosion by negative pressure. Oecologia 2001, 126, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.J.; Chapin, F.S.; Mooney, H.A. Resource Limitation in Plants-An Economic Analogy. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 1985, 16, 363–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, B.; Meziane, D. The balanced-growth hypothesis and the allometry of leaf and root biomass allocation. Funct. Ecol. 2002, 16, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorter, H.; Niklas, K.J.; Reich, P.B.; Oleksyn, J.; Poot, P.; Mommer, L. Biomass allocation to leaves, stems and roots: Meta-analyses of interspecific variation and environmental control. New Phytol. 2012, 193, 30–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, R.; Merino, J. Comparison of leaf construction costs in woody species with differing leaf life-spans in contrasting ecosystems. New Phytol. 2001, 151, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yin, M.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Wang, R.; Yin, H. Differential aboveground-belowground adaptive strategies to alleviate N addition-induced P deficiency in two alpine coniferous forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 849, 157906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deltedesco, E.; Keiblinger, K.M.; Piepho, H.-P.; Antonielli, L.; Pötsch, E.M.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S.; Gorfer, M. Soil microbial community structure and function mainly respond to indirect effects in a multifactorial climate manipulation experiment. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 142, 107704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsch, M.A.; Bader, M.Y. Treeline form—A potential key to understanding treeline dynamics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011, 20, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, J.A. Bark thickness across the angiosperms: More than just fire. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, E.; Weng, E.; Yan, E.; Xia, J. Robust leaf trait relationships across species under global environmental changes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Sunny Slope | Shady Slope | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude Range (m) | 3696–4200 | 3680–4200 | - |

| Soil WC (%) | 64.31 ± 21.13 | 54.41 ± 20.59 | 0.527 |

| Soil TN (g/kg) | 3.37 ± 0.62 | 2.94 ± 0.84 | 0.446 |

| Soil TP (g/kg) | 0.63 ± 0.09 | 0.54 ± 0.13 | 0.302 |

| Soil N/P | 5.34 ± 0.64 | 5.97 ± 3.32 | 0.733 |

| Trait | Sunny Slope (Mean ± SD) | Shady Slope (Mean ± SD) | p-Value | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Bark Thickness (mm) | 15.83 ± 9.02 | 21.19 ± 14.76 | 0.002 | −0.44 |

| Relative Bark Thickness | 0.39 ± 0.14 | 0.49 ± 0.21 | <0.001 | −0.60 |

| Bark Density (g/cm3) | 0.39 ± 0.08 | 0.34 ± 0.08 | <0.001 | 0.59 |

| Bark Water Content (%) | 0.96 ± 0.03 | 0.97 ± 0.03 | 0.079 | −0.24 |

| Bark Total C (g/kg) | 505.95 ± 15.57 | 505.61 ± 28.13 | 0.912 | 0.02 |

| Bark Total N (g/kg) | 2.93 ± 1.99 | 3.98 ± 0.81 | <0.001 | −0.69 |

| Bark Total P (g/kg) | 0.57 ± 0.20 | 0.47 ± 0.19 | <0.001 | 0.52 |

| Bark C/N Ratio | 194.82 ± 50.99 | 132.15 ± 26.55 | <0.001 | 1.54 |

| Bark N/P Ratio | 5.50 ± 2.93 | 9.45 ± 3.25 | <0.001 | −1.28 |

| Slope Aspect | Intercept (SMA a) | Slope (SMA b) | R2 | p-Value (Correlation) | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunny | −0.54 | 0.87 | 0.77 | <0.001 | 108 |

| Shady | −0.89 | 1.03 | 0.77 | <0.001 | 108 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xu, W.; Lu, J.; Wang, C.; Li, R. Topographic Heterogeneity Drives the Functional Traits and Stoichiometry of Abies georgei var. smithii Bark in the Sygera Mountains, Southeast Tibet. Forests 2026, 17, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020163

Xu W, Lu J, Wang C, Li R. Topographic Heterogeneity Drives the Functional Traits and Stoichiometry of Abies georgei var. smithii Bark in the Sygera Mountains, Southeast Tibet. Forests. 2026; 17(2):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020163

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Wenyan, Jie Lu, Chao Wang, and Rui Li. 2026. "Topographic Heterogeneity Drives the Functional Traits and Stoichiometry of Abies georgei var. smithii Bark in the Sygera Mountains, Southeast Tibet" Forests 17, no. 2: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020163

APA StyleXu, W., Lu, J., Wang, C., & Li, R. (2026). Topographic Heterogeneity Drives the Functional Traits and Stoichiometry of Abies georgei var. smithii Bark in the Sygera Mountains, Southeast Tibet. Forests, 17(2), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17020163