Abstract

In the context of climate change and greenhouse gas emissions, the forestry sector holds significant potential to contribute to global mitigation efforts. One of the primary drivers of deforestation is land expansion for livestock production. However, both sectors are closely linked to issues of food security and food sovereignty, with the livestock sector playing a crucial role in ensuring food availability. Integrating these two sectors through silvopastoral systems offers a promising solution that supports forest conservation while simultaneously addressing the global food crisis. Among the leading initiatives in forest conservation is REDD+, a mechanism under the UNFCCC that has proven effective in reducing deforestation and forest degradation, as well as in enhancing carbon stock conservation. Following the ratification of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement in 2024, REDD+ has gained recognition as a viable approach for generating international carbon credits. Given the intersection of the livestock and forestry sectors, and the potential of carbon credits to advance the goals of the Paris Agreement, silvopastoral systems could be considered for inclusion in REDD+ strategies under the framework of Article 6.

1. Introduction

Worldwide, livestock expansion is recognized as one of the major drivers of permanent deforestation. In Central and South America, extensive land-use change, particularly the conversion of forests to pasture, has been strongly influenced by the growing demand for livestock production [1]. In Nicaragua, for instance, the primary driver of forest cover loss was pasture conversion, accounting for approximately 93% of total deforestation between 1978 and 2011 [2]. To combat deforestation, several countries have implemented various strategies, including REDD+ (reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries) activities. As of February 2025, 19 countries have received results-based payments for their REDD+ achievements through the REDD+ mechanism under the UNFCCC [3].

At COP26, leaders from 145 nations (as of 21 February 2025), through the Glasgow Declaration on Forests and Land Use, committed to halting and reversing forest loss and land degradation by 2030 [4]. Soon after, the 29th Conference of the Parties (COP29) in 2024 marked a key milestone in implementing Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, setting the stage for establishing an international carbon market under the UNFCCC. During nearly a decade of negotiation, one of the main focuses has been the role of REDD+ activities, which are central to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation [5]. In this context, REDD+ serves as a cornerstone mechanism with well-established rules that link national efforts to global markets.

Countries implementing REDD+ activities may be eligible to receive results-based payments under the UNFCCC if they meet the criteria of the Warsaw Framework for REDD+ (WFR), a comprehensive set of decisions that provides the complete rules and modalities for implementing the REDD+ activities. This framework has contributed to significant emissions reductions in the forest sector [6]. Under the Paris Agreement’s Article 6, mitigation efforts, such as those conducted through WFR are considered eligible. Article 6.2 (decision 18/CMA.1, annex, para 64(e)), does not limit the types of mitigation activities that can produce Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs). Additionally, the Article 6.4 Methodology Standard (Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies)) paragraph 87 clearly acknowledges that activities under Paris Agreement Article 5.2 (formalization the architecture of implementation and support approaches for REDD+ framework under the UNFCCC) can be part of the mechanism as long as they adhere to the required methodologies and safeguards. These provisions collectively affirm that REDD+ activities are allowed to engage in Article 6 mechanisms and can be traded within the carbon market established by the Paris Agreement. While REDD+ provides the overarching framework, the effectiveness of its outcomes also depends on the specific activities implemented at national and local scales, tailored to each country’s circumstances [7].

A wide range of activities has been implemented in accordance with national circumstances. The silvopastoral system, a tree-based production approach, integrates tree planting with pastures, often in combination with livestock. This system helps reduce forest loss by mitigating the need to expand livestock activities (and related crops or pastures) into forested areas. Additionally, silvopastoral systems are known to store more carbon than conventional livestock farming and to enhance biodiversity within the system [8]. Recognizing these co-benefits, it is valuable to explore how silvopastoral systems can be integrated into REDD+ activities and aligned with opportunities under Article 6.

This paper aims to provide an overview of the REDD+ mechanism, with a particular focus on the UNFCCC REDD+ results-based payment framework and the silvopastoral system. It further examined the extent to which silvopastoral systems have been included in existing or past REDD+ activities among countries officially registered on the UNFCCC REDD+ Web Platform. The information presented aims to offer a general understanding of how silvopastoral systems can be incorporated into REDD+ activities for carbon credit generation, particularly within the framework of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

2. Methodology

This study adopts a narrative review approach rather than an exhaustive systematic review, with an explicit emphasis on conceptual scope and analytical depth. The review was developed focusing on the integration of silvopastoral systems within the UNFCCC REDD+ framework and extending the analysis to their potential relevance under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

The analytical foundation of the review is grounded in countries’ official submissions on REDD+ activities, as documented on the UNFCCC REDD+ Web Platform. Particular attention is given to Latin American countries, as these submissions indicate that the region has the most extensive experience with the implementation of silvopastoral systems and related agroforestry practices.

Sources were selected based on their relevance to each thematic component of the review. Strategy and policy-oriented components largely relied on countries’ submissions to UNFCCC REDD+ Web-platform (National REDD+ Strategies, Forest Reference Level (FRL), and proposal for results-based payments to Green Climate Fund (GCF)), submitted Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) to UNFCCC, official UNFCCC documents (e.g., COP decisions), reports from international organizations (e.g., FAO), and official webpage of international organizations. Discussions on underlying evidences or considerations rely on peer-reviewed article and technical reports. Wherever feasible, the most recent sources were used.

3. Silvopastoral Systems, Emission Reduction, and Co-Benefits

The silvopastoral system is an agroforestry practice that integrates livestock, forage production, and forestry within the same land area, effectively combining the livestock and forestry sectors to enhance sustainability. By strategically planting trees alongside grazing pastures, silvopastoral systems provide multiple ecological and economic benefits, including improved animal welfare through shade provision, increased forage quality, and diversified farm income from timber and non-timber forest products. The presence of trees significantly reduces erosion, enhances soil fertility, and promotes biodiversity by creating diverse habitats. As a multifunctional land-use system, silvopastoral systems not only mitigate deforestation pressures associated with conventional livestock farming but also contribute to climate change adaptation and mitigation by sequestering carbon, both above and below ground [9,10]. Various types of silvopastoral systems exist and can be categorized by tree arrangement, management practices, and species composition [11].

Silvopastoral systems also contribute significantly to emission reduction by optimizing land use, reducing dependence on synthetic fertilizers, and enhancing soil health by improving its structure, nutrient availability and microbial activity [12]. Integrating trees into livestock grazing areas improves nitrogen and nutrient cycling, thereby lowering the requirement for chemical fertilizers. The production and application of such fertilizers are major sources of greenhouse gases (GHGs), particularly nitrous oxide emissions [13]. The improved vegetation cover in silvopastoral systems reduces soil erosion and enhances organic matter accumulation, resulting in higher soil carbon sequestration rates approximately 18.5 times more than those with low coverage [14]. By fostering these natural processes, silvopastoral systems not only curtail emissions directly associated with livestock farming but also promote ecosystem resilience and sustainable agricultural practices [15]. The integration of trees into grazing lands enhances biodiversity by creating diverse habitats that attract birds, insects, and other beneficial wildlife, thus, contributing to ecosystem stability and resilience [16]. Trees act as windbreaks, moderating microclimates and reducing heat stress in livestock, thereby improving animal health and productivity [17].

Silvopastoral systems and agroforestry practices contribute to climate change mitigation primarily through carbon sequestration, with studies indicating that they can store approximately 27%–163% more carbon than open pasture systems. In addition to their mitigation potential, these systems enhance biodiversity and improve soil fertility, as well as water regulation functions [18,19]. Existing literature also frames traditional livestock systems as socioecological systems, highlighting the central role of smallholders and the integration of indigenous knowledge in facilitating sustainable land-use transitions [20,21].

Nevertheless, carbon stock across different ecosystem pools within silvopastoral systems can vary considerably depending on management practices [14,22,23], creating uncertainty in their overall carbon balance. Long-term trade-offs between woody encroachment and tree survival may further result in declining tree density and carbon storage over time [24]. In addition, the spatial distribution and growth dynamics of livestock populations introduce further uncertainty in CO2 emissions estimates within silvopastoral systems [25]. More broadly, the ecosystem services delivered by these systems are highly context-dependent, influenced by local climate conditions, soil properties, species selection, system design, and management practices [19,22]. Carbon storage capacity or potential volume of carbon that can be captured and stored, also varies across regions (e.g., in tropical humid land up to 228 Mg C/ha in Southeast Asia and up to 51 Mg C/ha in Australia) and systems with various tree species demonstrates greater resilience to climate variability and higher potential for carbon sequestration [22].

4. Understanding the REDD+ Mechanism and Article 6 of the Paris Agreement

REDD refers to “Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation” in developing countries, while the plus (+) signifies additional forest-related activities that contribute to climate protection, namely, the sustainable management of forests and the conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks [26]. The origins of the REDD+ mechanism trace back to COP11, when Costa Rica and Papua New Guinea first called on the COP to address the issue of reducing emissions from deforestation (RED). This initiative later evolved into REDD+ and was formally incorporated into the Bali Action Plan in 2007 (COP13). In 2013, the COP adopted the WFR, which provides guidance and criteria for measuring results, ensuring safeguards, and accessing results-based finance for developing countries [27]. The REDD+ mechanism, originally designed within a national-scale framework under the UNFCCC, has since been adopted and implemented by independent actors at the project level (REDD+ projects). Consequently, REDD+ projects, primarily operating within the voluntary carbon market (VCM), function separately from the REDD+ mechanism under the UNFCCC.

REDD+ actions comprise both policies (enabling environments) and measures (implementation activities) [28]. REDD+ activities are not strictly defined in the UNFCCC decision texts, allowing developing countries to flexibly interpret and adapt their meaning, implications, and relevance within their national context. Nevertheless, REDD+ activities are broadly defined in general terms. Reducing emissions from deforestation targets GHG emissions from human-induced forest conversion. These emissions occur when forests are cleared for agriculture, infrastructure, or other uses, representing long-term or permanent land-use changes. Forest degradation involves activities that reduce forest carbon stocks without changing land use (e.g., logging or fuelwood collection). Enhancement generally includes afforestation, reforestation, and forest restoration. Conservation, however, lacks precedent under the UNFCCC [29].

In the VCM, REDD+ is categorized as a nature-based solution project type, which may include activities such as avoided deforestation, improved forest management, and afforestation, reforestation, and regeneration (ARR). REDD+ in the VCM can be implemented at both project and jurisdictional scales. At both scales, REDD+ projects generate carbon credits that can be transacted in the VCM. The demand for such credits grew rapidly, particularly between 2017 and 2021, with approximately 356 projects implemented across 51 countries in 2021 [30].

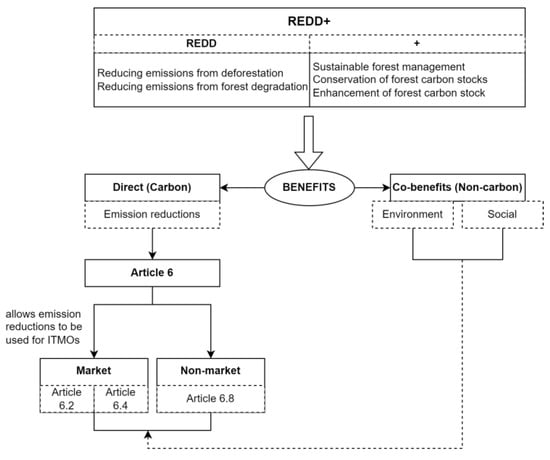

Article 6 of the Paris Agreement provides a framework that enables international collaborative approach in climate actions. The framework is defined in Paris Agreement text, consisting of market approach, reflected in Article 6 paragraph 2 (Article 6.2) and paragraph 4 (Article 6.4), and non-market approach, reflected in paragraph 8 (Article 6.8). The relationship between REDD+ and Article 6 is rooted in the eligibility of emission reductions generated through REDD+ to be used as ITMOs (Figure 1), and transacted through market approach. Article 6 of the Paris Agreement aims to enable countries to trade mitigation outcomes to achieve their NDC targets. Although ITMOs represent the central concept of the market-based approach under Article 6, the implementation of both market and non-market mechanisms also requires compliance with specific criteria related to sustainable development and environmental integrity. Under Article 6.2, activities are jointly defined by participating countries as part of a cooperative approach. However, under Article 6.4, paragraph 87 of the Article 6.4 Methodology Standard explicitly states “for those activities falling under the scope of Article 5, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement…,” implying that REDD+ activities under the UNFCCC are eligible for trading within the Article 6.4 mechanism. Article 5, paragraph 2, of the Paris Agreement text specifies actions to implement and support results-based payment programs for REDD+ activities in developing countries. The inclusion of REDD+ activities within Article 6 is also reflected in COP Decision 1/CP.17, paragraphs 66 and 67, and COP Decision 14/CP.19, paragraph 15.

Figure 1.

Relationship between REDD+ activities and Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

5. Silvopastoral Systems in UNFCCC REDD+ Results-Based Payments

The interpretation of including silvopastoral systems in REDD+ activities may vary. However, it is evident that silvopastoral systems are recognized as sustainable practices because they not only preserve the environment and biodiversity but also maintain productive benefits. Furthermore, the transition from extensive grazing to silvopastoral systems can reduce both soil and forest degradation [31]. Additionally, silvopastoral systems represent one of the strategies for enhancing forest carbon stocks. This is due to their ability to reduce overall pressure on forests, thereby implying eligibility under REDD+ mechanisms [31].

Silvopastoral systems can be aligned with several of the five REDD+ activity categories. While such systems help reduce pressure to clear additional forest land for grazing and lessen degradation caused by extensive open grazing, their most significant alignment lies in the plus (+) elements of REDD+ activities. Silvopastoral systems maintain tree cover, as well as integrate shrubs and fodder trees that help conserve on-farm biomass and associated carbon stocks. Furthermore, silvopastoral systems actively sequester carbon both above and below ground through enrichment planting, the establishment of fodder banks, and increased tree density within grazing lands [9].

Table 1 illustrates the number of countries engaged in UNFCCC REDD+ mechanisms that have referenced silvopastoral systems in their various REDD+-related submissions, i.e., National REDD+ Strategy and Forest Reference Level (FRL), and NDC submission. This suggests that, in some cases, silvopastoral practices have been incorporated either directly or indirectly into REDD+ implementation. The inclusion of silvopastoral systems in REDD+ strategies enables the creation of co-benefits for REDD+ activities, representing a synergy between climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Table 1.

Inclusion of silvopastoral systems in countries’ submissions of National REDD+ strategies, NDCs, and FRLs.

The relationship between agriculture and deforestation is complex, particularly due to the dependence of rural populations on the agricultural sector. This complexity should be considered when designing programs or policies that address agriculture, specifically livestock production as a driver of deforestation, since socio-economic factors may influence the effectiveness of achieving REDD+ goals [32]. Among REDD+ projects in Mexico, one analysis showed that in certain regions, silvopastoral systems were among the most preferred practices because livestock production was perceived as the main contributor to household income. Furthermore, participants valued that the proposed scenario included support and equipment to optimize the use of agricultural residues as livestock feed [33].

Across Latin America, silvopastoral systems have evolved from traditional land-use practices into structured policy instruments for sustainable land management. Table 2 illustrates the countries’ REDD+ proposal submission to GCF to receive payments based on their emission reduction results from REDD+ activities. As summarized in Table 2, five countries have integrated silvopastoral or agroforestry-based approaches into broader climate and forest policy frameworks. A key similarity among these countries is their recognition of silvopastoral systems as a means to reconcile livestock production with forest conservation, balancing productivity with forest integrity. Furthermore, the inclusion of social and gender dimensions is also emphasized in these programs, particularly in Costa Rica and Colombia, which support and prioritize the engagement of women and local communities. Emphasis on environmental outcomes such as forest restoration and biodiversity conservation, is also evident. These national experiences suggest that integrating forest and livestock systems under robust policy frameworks can generate multiple co-benefits, including reduced deforestation, enhanced climate resilience, and improved rural livelihoods.

Table 2.

Silvopastoral systems in REDD+ proposal submissions by countries.

6. The Interplay Among Silvopastoral Systems, REDD+, and Article 6 of the Paris Agreement

Many countries receiving results-based payments under the UNFCCC REDD+ program, are considered to be among the first candidates to issue ITMOs under Article 6, particularly Article 6.2. Owing to the flexibility regarding project types under Article 6.2, host countries may determine which activities are eligible, referred to as a “positive list.” Furthermore, many host countries have established sustainable development criteria tailored to their national priorities. For instance, Cambodia requires projects to contribute to poverty alleviation by increasing income-generation opportunities and improving local livelihoods [38]. Similarly, in Ghana, ITMOs must originate from mitigation activities that are consistent with and contribute to Ghana’s sustainable development objectives [39]. This suggests that emission reduction remains the primary objective for buyer countries and financial support serves as a key incentive for host countries. Nevertheless, the co-benefits associated with each credit have become increasingly important. Although often difficult to quantify, co-benefits provide tangible value to local communities and play a vital role in advancing national development strategies.

Agroforestry can function either as a direct REDD+ activity or as an enabling condition for its implementation, depending on whether it meets the national forest definition. When included directly, it contributes to sustainable forest management, the enhancement of forest carbon stocks, and the prevention of conversion to monoculture systems. As an enabling measure, agroforestry helps address deforestation drivers by reducing pressure on forest land through sustainable intensification and diversification [40]. In addition, the long-term success of REDD+ depends on the systematic identification, monitoring, and incentivization of non-carbon benefits, such as biodiversity enhancement, improved livelihoods, and strengthened forest governance [41]. Smallholder agroforestry parklands have a high carbon sequestration potential and marketable carbon value relevant for REDD+ [42].

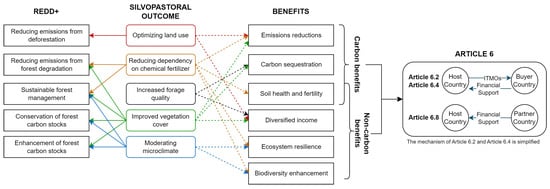

While funding through compliance mechanisms under Article 6 is often primarily focused on emission reductions rather than on generating or sustaining non-carbon benefits [41], the inclusion of silvopastoral systems through REDD+ activities under Article 6 goes beyond emission reduction (Figure 2). The non-carbon benefits generated by silvopastoral systems align closely with the elements required in Article 6 documentation (Table 3), reflecting their potential to contribute to both environmental and socio-economic objectives. Moreover, agroforestry systems are often rooted in long-standing experience and local knowledge with high cultural importance, which enhances their compatibility with REDD+ safeguards and broader sustainability objectives [43].

Figure 2.

Examples of interlinkages between silvopastoral systems, REDD+ activities, and the resulting environmental and socioeconomic benefits.

Table 3.

Relevance between non-carbon benefits in silvopastoral systems and Article 6 elements.

A prior precedent, established through the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol, enabled agroforestry systems owned by subsistence farmers to sell sequestered carbon credits, thereby providing both economic opportunities and sustainable development pathways for smallholder systems [31]. This connection becomes increasingly relevant because co-benefits serve as a key justification for including silvopastoral systems in REDD+ under Article 6. These systems align with sustainable development goals by contributing to ecology (e.g., biodiversity enhancement and soil health), labor (e.g., rural employment), and gender equality (e.g., diversified income opportunities for smallholders, particularly benefiting women in farming communities) [44]. Moreover, evidence suggests that carbon markets reward projects delivering strong co-benefits. For instance, Lou et al. [45] found that the greater the number of co-benefits a project provides, the higher the price its credits can command. Within REDD+ activities, non-carbon benefits are integrated through various mechanisms, including (i) early incorporation during readiness and implementation phases, (ii) the use of non-carbon benefits as conditions for results-based payments, (iii) linking co-benefits to increased credit value, and (iv) certification or payments for ecosystem services (PES) to monetize such benefits [46].

The eligibility of REDD+ activities approved under Article 6.4 methodologies remains limited to those recognized under the UNFCCC, which may also influence the eligibility of REDD+ activities under Article 6.2. This implies that, unless REDD+ activities meet all requirements listed in the WFR, such activities may not qualify for inclusion under Article 6.4. This presents a significant opportunity for countries implementing UNFCCC REDD+ mechanisms to convert their verified emission reductions into ITMOs. Furthermore, the newly approved standard (Addressing non-permanence and reversals in mechanism methodologies) explicitly states that it applies to various activity types, including agricultural practices aimed at enhancing soil organic carbon. Collectively, the supporting standards and the Article 6.4 rulebook create space for silvopastoral systems to emerge as potential activities under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

7. Existing Challenges of the Silvopastoral System

Despite the many benefits of silvopastoral systems, they are uncommonly integrated into REDD+ activities because of technical challenges. The complexity of silvopastoral systems makes measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) particularly difficult, limiting their inclusion in national MRV frameworks. In Bangladesh, Bolivia, and Rwanda, for example, national policies and governance arrangements do not sufficiently prioritize agroforestry or trees outside forests; as a result, despite the availability of data on their extent, and carbon benefits, integration into national MRV systems remains unlikely in the short term, particularly in the absence of dedicated institutional authority and stable policy support [47]. Furthermore, the forest definitions commonly used in REDD+ exclude agroforestry systems (including silvopastoral systems), reinforcing their marginalization within MRV frameworks.

A study by Rosenstock TS et al. [48] revealed the challenges associated with agroforestry MRV systems faced by developing countries fall into three main categories: institutional arrangements and enabling environments, technical capacity and facilities, and finance. In some national systems, land categories distinguish between forested and non-forested lands (i.e., recently afforested areas). While this allows certain agroforestry types to be included, such categorization often limits transparency in reporting on the nature and extent of agroforestry systems. Technical limitations are among the most common constraints, ranging from the high cost of high-resolution satellite imagery to unreliable statistical approaches. Furthermore, forest definitions were described as both enabling and constraining factors. Discrepancies among national, FAO, and IPCC definitions create ambiguity and inconsistencies between domestic and international reporting. Countries that have successfully incorporated agroforestry into their national GHG inventories achieved this by integrating agroforestry into their regular statistical systems, ensuring access to satellite data, and utilizing multiple data sources tailored to different forest categories. Nevertheless, many countries emphasized that improvements cannot rely solely on better data and methods. An enabling institutional and political context is also essential and continues to represent a major obstacle for many developing countries.

As highlighted in several Forest Reference Level (FRL) submissions (Table 1), silvopastoral systems are often excluded from national forest definitions. In some cases, they are even considered drivers of forest degradation, particularly where primary forests are converted into silvopastoral systems. In several countries, traditional silvopastoral practices have been identified as key causes of deforestation and degradation, as they often involve clearing native forests rather than restoring degraded lands [8]. Therefore, it is essential to clarify that the inclusion of silvopastoral systems should not be interpreted as endorsing forest conversion. Instead, it should represent an approach to rehabilitate degraded lands or forests, thereby enhancing environmental integrity and generating non-carbon benefits. For instance, agroforestry systems are presented as sustainable alternative to shifting cultivation, which is linked to deforestation in the Amazon [49].

In addition, the scope of non-carbon benefits remains loosely defined, creating challenges in their identification, targeting, and promotion within REDD+ programs. The absence of standardized practices to incentivize non-carbon benefits has constrained both their quality and long-term sustainability. Therefore, while the operationalization of Articles 6.2, 6.4, and 6.8 offers new opportunities to facilitate REDD+ investment [41], the adoption remains limited due to the complexity of silvopastoral practices, technical limitation, and inadequate support.

Adoption of silvopastoral systems is also limited by high initial establishment costs and limited access to capital. These are the primary constraints for smallholders, particularly because economic returns often take years to materialize. Evidence shows that direct incentives, such as Payments for Ecosystem Services, are more effective in encouraging adoption than conventional credit. Beyond financial barriers, uptake is further hindered by insecure land tenure, post-conflict land speculation in frontier areas, and legal uncertainties related to tree planting. Persistent technical and knowledge gaps, along with cultural perceptions that trees reduce pasture productivity, also discourage adoption. These challenges are compounded by environmental risks, including vulnerability to droughts and floods, which increase farmers’ reluctance to invest in silvopastoral practices [21,50,51,52].

A unified, research-driven strategy is essential to overcome technical and policy barriers, foster collaboration between stakeholders, and fully realize the economic and environmental benefits of integrating trees into agricultural landscapes [53]. In this context, addressing market and management barriers requires bridging existing market and management gaps through an integrated framework that combines support for local innovation, enhanced market branding, direct economic incentives, and effective technical knowledge transfer. Such approach is essential for ensuring the long-term viability and scaling of agroforestry and silvopastoral systems [54,55].

8. Conclusions

Across Latin America, silvopastoral systems are increasingly recognized within National REDD+ Strategies, particularly in countries where livestock and agriculture are central to national economies. Existing evidence demonstrates that silvopastoral systems can address key drivers of deforestation while maintaining productive land use and contributing to climate change mitigation through enhanced carbon sequestration. These attributes position silvopastoral systems as potentially important instruments for supporting the achievement of NDC. However, this recognition does not yet equal formal inclusion in REDD+ or carbon accounting.

The literature consistently characterizes silvopastoral systems as a multifunctional land-use strategy, highlighting their capacity to improve livestock productivity, diversify rural incomes, enhance resilience through microclimatic regulation, reduce GHG emissions, and increase carbon storage in pastures and woody biomass. In addition to mitigation benefits, silvopastoral systems deliver a wide range of ecosystem services, including soil and water conservation, biodiversity enhancement, reduced pressure on forest conservation, and improved animal welfare, while also contributing to multiple SDGs [56].

Despite this growing body of evidence on environmental and socio-economic benefits, existing research has focused predominantly on farm and landscape-level outcomes. Comparatively, limited attention has been paid to the institutional, definitional, and methodological barriers. As a result, a persistent gap remains between demonstrated local effectiveness and formal recognition within international carbon accounting.

This review argues that integrating silvopastoral systems into REDD+ and linking them to Article 6 of the Paris Agreement represents a significant opportunity to bridge this gap. Such integration would connect farm-level and subnational land management directly to international climate finance mechanisms, repositioning silvopastoral systems from localized interventions to nationally scalable tools for achieving Paris Agreement objectives. This shift reflects a broader paradigm in which environmental sustainability and climate resilience are embedded within, rather than traded off against core economic activities. Nevertheless, this potential requires addressing critical institutional barriers, particularly the need for robust MRV frameworks and alignment with forest definitions.

A well-defined MRV system is essential to ensure effective implementation and to secure formal recognition of silvopastoral systems within REDD+ and Article 6 mechanism. MRV innovation and land-use classification offer promising pathways to support scalable implementation. For instance, the convergence of advanced technologies such as remote sensing, GIS, blockchain, offers significant opportunities to improve the MRV systems in REDD+ [57]. In parallel, the adoption of hybrid land-use systems, for example, combining silvopastoral and Taungya systems, may help address the exclusion of silvopastoral systems from forest definition, as Taungya is classified as forest land by FAO definition [58]. Repositioning silvopastoral systems as multifunctional land-use strategies can therefore simultaneously support forest conservation, sustain rural livelihoods, and enhance food security. Effectively addressing these institutional barriers is essential for enabling silvopastoral systems beyond localized implementation and toward nationally scalable approaches for achieving the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

While this review offers a conceptual assessment of the potential for integrating silvopastoral systems into REDD+ and Article 6 mechanism, it is not exhaustive. Consequently, context-specific operational and institutional challenges may not be fully captured. Future research should therefore prioritize national and subnational case studies focused on MRV design, forest definition, and accounting under REDD+ and Article 6 to support the scalable inclusion of silvopastoral systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.N.; Resource, E.N., Y.S.P. and J.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, E.N. and Y.S.P.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.N., J.C. and M.S.; Visualization, E.N.; Supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Forest Science (Grant no. FM0800-2022-01-2025).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FAO | Food and Agriculture Organization |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ITMOs | Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes |

| NDC | Nationally Determined Contribution |

| REDD+ | Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

| VCM | Voluntary Carbon Market |

| WFR | Warsaw Framework for REDD+ |

References

- FAO. Cattle Ranching and Deforestation [Internet]. FAO Livestock Policy Briefs. 2007. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0b4d2952-b42c-4725-8aad-24deb2bb1de1/content (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Tobar-lópez, D.; Bonin, M.; Andrade, H.J.; Pulido, A.; Ibrahim, M. Deforestation processes in the livestock territory of La Vía Láctea, Matagalpa, Nicaragua. J. Land Use Sci. 2019, 14, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. UNFCCC REDD+ Web Platform [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://redd.unfccc.int/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- COP26. Glasgow Leader’s Declaration on Forests and Land Use [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20230418175226/https://ukcop26.org/glasgow-leaders-declaration-on-forests-and-land-use/ (accessed on 27 February 2025).

- The Nature Conservancy. Key Takeaways on Article 6 at COP29 [Internet]. 2024. Available online: https://www.nature.org/content/dam/tnc/nature/en/documents/COP29-Article-6-Key-Outcomes.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Coalition for Rainforest Nations. REDD+ Under the UNFCCC Primer Report [Internet]. 2023. Available online: https://www.rainforestcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/CfRN_REPORT_ReddplusUnderUNFCCC_PRIMER_B2.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Aryal, K.; Maraseni, T.; Rana, E.; Subedi, B.P.; Laudari, H.K.; Ghimire, P.L.; Khanal, S.C.; Zhang, H.; Timilsina, R. Carbon emission reduction initiatives: Lessons from the REDD+ process of the Asia and Pacific region. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AAryal, D.R.; Morales-Ruiz, D.E.; López-Cruz, S.; Tondopó-Marroquín, C.N.; Lara-Nucamendi, A.; Jiménez-Trujillo, J.A.; Pérez-Sánchez, E.; Betanzos-Simon, J.E.; Casasola-Coto, F.; Martínez-Salinas, A.; et al. Silvopastoral systems and remnant forests enhance carbon storage in livestock-dominated landscapes in Mexico. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jose, S.; Dollinger, J. Silvopasture: A sustainable livestock production system. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 93, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montagnini, F.; Metzel, R. The Contribution of Agroforestry to Sustainable Development Goal 2: End Hunger, Achieve Food Security and Improved Nutrition, and Promote Sustainable Agriculture. In Integrating Landscapes: Agroforestry for Biodiversity Conservation and Food Sovereignty; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 11–45. [Google Scholar]

- Mosquera-Losada, M.R.; McAdam, J.; Rigueiro-Rodriguez, A. Silvopastoralism and Sustainable Land Management; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Agunbiade, G.; Sahoo, D.; O’Halloran, L.; Silva, L.; Malcomson, H. Impact of silvopasture on soil health and water quality in the Southeast US: A review. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102448. [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano, D.; Ledo, A.; Hillier, J.; Nayak, D.R. Which agroforestry options give the greatest soil and above ground carbon benefits in different world regions? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 254, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavisoy, H.; Vallejos, A.R.R.; Rincón, E.C.; Narváez-Herrera, J.P.; Rosas, L.; Acosta, A.d.S.G.; Salcedo, A.A.R.; Alban, D.M.A.; Chingal, C.; Fangueiro, D.; et al. Carbon balance in dairy cattle silvopastoral production systems in Colombia’s Andean-Amazon region. Agrofor. Syst. 2025, 99, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran Nair, P.; Moham Kumar, B.; Nair, V.D. An Introduction to Agroforestry: Four Decades of Scientific Developments, 2nd ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Torralba, M.; Fagerholm, N.; Burgess, P.J.; Moreno, G.; Plieninger, T. Do European agroforestry systems enhance biodiversity and ecosystem services? A meta-analysis. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 230, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, H.M.; Kayed, M. Applying porous trees as a windbreak to lower desert dust concentration: Case study of an urban community in Dubai. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 57, 126915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebaw, S.E.; Yeshiwas, E.M.; Feleke, T.G. A Systematic Review on the Role of Agroforestry Practices in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation. Clim. Resil. Sustain. 2025, 4, e70018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Macêdo Carvalho, C.B.; de Mello, A.C.; da Cunha, M.V.; de Oliveira Apolinário, V.X.; Júnior, J.C.D.; da Silva, V.J.; Medeiros, A.S.; Izidro, J.L.; Bretas, I.L. Ecosystem services provided by silvopastoral systems: A review. J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 162, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Romero, R.; Balvanera, P.; Castillo, A.; Mora, F.; García-Barrios, L.E.; González-Esquivel, C.E. Management strategies, silvopastoral practices and socioecological drivers in traditional livestock systems in tropical dry forests: An integrated analysis. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 479, 118506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, S.A.G.; Ortiz, M.G.A.; Sangache, V.L.C.; Andrade, J.A.C.; Teran, J.E.L.; Lara, J.C.B.; Blacio, M.V.F.; Toulkeridis, T. Silvopastoral Systems: A Sustainable Livestock Farming Strategy for the Ecuadorian Amazon. J. Lifestyle SDGs Rev. 2025, 5, e04928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.A.; Khan, S.M.; Jahangir, S.; Ali, S.; Tulindinova, G.K. Carbon Storage and Dynamics in Different Agroforestry Systems. In Agroforestry; Scrivener Publishing LLC: Beverly, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 345–374. [Google Scholar]

- Bateni, C.; Ventura, M.; Tonon, G.; Pisanelli, A. Soil carbon stock in olive groves agroforestry systems under different management and soil characteristics. Agrofor. Syst. 2019, 95, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, P.D.; de Waroux Yle, P.; Jobbágy, E.G.; Loto, D.E.; Gasparri, N.I. A hard-to-keep promise: Vegetation use and aboveground carbon storage in silvopastures of the Dry Chaco. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 303, 107117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbohessou, Y.; Delon, C.; Grippa, M.; Mougin, E.; Ngom, D.; Gaglo, E.K.; Ndiaye, O.; Salgado, P.; Roupsard, O. Modelling CO2 and N2O emissions from soils in silvopastoral systems of the West African Sahelian band. Biogeosciences 2024, 21, 2811–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. What Is REDD+? [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://unfccc.int/topics/land-use/workstreams/redd/what-is-redd (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Voigt, C.; Nemitz, D.; Ferreira, F.; Brana-Varela, J.; Sanchez, M.S. The Paris Agreement and the importance of the Warsaw Framework for REDD+ (WFR). Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2025, 34, 228–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. REDD+ Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/redd/initiatives/un-redd/en/ (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- UN-REDD. Towards a Common Understanding of REDD+ Under the UNFCCC; UN-REDD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Primer, V.C.M. The Voluntary Carbon Market Explained. Chapter 13 [Internet]. 2021. Available online: https://vcmprimer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/vcm-explained-chapter3-compressed_1.pdf (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Pradhan, C.; Ghosh, A.K.; Singh, P. Agroforestry Systems: An Effective Tool for Carbon Sequestration [Internet]. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380168651 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Graham, K.; Vignola, R. REDD+ and Agriculture: A Cross-Sectoral Approach to REDD+ and Implication for the Poor; ODI Global: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Spiric, J.; Reyes, A.E.M.; Rodriguez, M.L.A.; Ramirez, M.I. Impacts of REDD+ in Mexico: Experiences of two local communities in Campeche. Soc. Ambiente 2021, 24, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund. Argentina REDD-Plus RBP for Results Period 2014–2016; Green Climate Fund: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund. Colombia REDD+ Results-Based Payments for Result Period 2015–2016; Green Climate Fund: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund. Costa Rica REDD-Plus Results-Based Payments for 2014 and 2015; Green Climate Fund: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Green Climate Fund. REDD+ Results-Based Payments in Paraguay for the Period 2015–2017; Green Climate Fund: Incheon, Republic of Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Environment. Operational Manual for the Implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change in Cambodia; Ministry of Environment: Cambodia, 2024. Volume 5. Available online: https://moe.gov.kh/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Article-6-OM_EN.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Government of Ghana. Ghana’s Framework on International Carbon Markets and Non-Market Approaches; Government of Ghana: Accra, Ghana, 2022. Available online: https://cmo.epa.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ghana-Carbon-Market-Framework-For-Public-Release_15122022.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Minang, P.A.; Duguma, L.A.; Bernard, F.; Mertz, O.; van Noordwijk, M. Prospects for agroforestry in REDD+ landscapes in Africa. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2014, 6, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugasseh, F.A.; Andersen, M.S. Non-carbon benefits of REDD+ implementation and sustainable emission reductions—A review. For. Trees Livelihoods 2024, 33, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neya, T.; Abunyewa, A.A.; Neya, O.; Zoungrana, B.J.-B.; Dimobe, K.; Tiendrebeogo, H.; Magistro, J. Carbon Sequestration Potential and Marketable Carbon Value of Smallholder Agroforestry Parklands Across Climatic Zones of Burkina Faso: Current Status and Way Forward for REDD+ Implementation. Environ. Manag. 2020, 65, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reang, D.; Hazarika, A.; Sileshi, G.W.; Pandey, R.; Das, A.K.; Nath, A.J. Assessing tree diversity and carbon storage during land use transitioning from shifting cultivation to indigenous agroforestry systems: Implications for REDD+ initiatives. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aynekulu, E.; Suber, M.; van Noordwijk, M.; Arango, J.; Roshetko, J.M.; Rosenstock, T.S. Carbon Storage Potential of Silvopastoral Systems of Colombia. Land 2020, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Hultman, N.; Patwardhan, A.; Qiu, Y.L. Integrating sustainability into climate finance by quantifying the co-benefits and market impact of carbon projects. Commun. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katerere, Y.; Fobissie, K.; Annies, A. Non-Carbon Benefits of REDD+ The Case for Supporting Non-Carbon Benefits in Africacarbon Benefits of REDD+: The Case for Supporting Non-Carbon Benefits in Africa; Climate and Development Knowledge Network and Economic Commission for Africa African Climate Policy Centre: Cape Town, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Wilkes, A.; Jallo, C.; Namoi, N.; Bulusu, M.; Suber, M.; Bernard, F.; Mboi, D. Making Trees Count Measurement, Reporting and Verification of Agroforestry Under the UNFCCC [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/world/making-trees-count-measurement-reporting-and-verification-agroforestry-under-unfccc (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Rosenstock, T.S.; Wilkes, A.; Jallo, C.; Namoi, N.; Bulusu, M.; Suber, M.; Mboi, D.; Mulia, R.; Simelton, E.; Richards, M.; et al. Making trees count: Measurement and reporting of agroforestry in UNFCCC national communications of non-Annex I countries. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 284, 106569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, P.M.; Martins, S.V.; de Oliveira Neto, S.N.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Hernández, E.P.; Kim, D.G. Policy forum: Shifting cultivation and agroforestry in the Amazon: Premises for REDD+. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Bonatti, M.; Löhr, K.; Palacios, V.; Lana, M.A.; Sieber, S. Adoption potentials and barriers of silvopastoral system in Colombia: Case of Cundinamarca region Adoption potentials and barriers of silvopastoral system in Colombia: Case of Cundinamarca region. Cogent Environ. Sci. 2020, 6, 1823632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Vargas, C.T.; Morgan, S.; Pantevéz, H.; Gomez, M.; Kennedy, C.M.; Kremen, C. Enablers and barriers to adoption of sustainable silvopastoral practices for livestock production in Colombia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1600091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado Sandino, C.O.; Barnes, A.P.; Sepúlveda, I.; Garratt, M.P.D.; Thompson, J.; Escobar-Tello, M.P. Examining factors for the adoption of silvopastoral agroforestry in the Colombian Amazon. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera-Losada, M.R.; Santos, M.G.S.; Gonçalves, B.; Ferreiro-Domínguez, N.; Castro, M.; Rigueiro-Rodríguez, A.; González-Hernández, M.P.; Fernández-Lorenzo, J.L.; Romero-Franco, R.; Aldrey-Vázquez, J.A.; et al. Policy challenges for agroforestry implementation in Europe. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1127601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolo, V.; Hartel, T.; Aviron, S.; Berg, S.; Crous-Duran, J.; Franca, A.; Mirck, J.; Palma, J.H.N.; Pantera, A.; Paulo, J.A.; et al. Challenges and innovations for improving the sustainability of European agroforestry systems of high nature and cultural value: Stakeholder perspectives. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1301–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro-Vargas, C.T.; Cudney-Valenzuela, S.; Morgan, S.; Kremen, C. Review of enablers and barriers to the adoption of silvopastoral systems in Latin America. Discov. Agric. 2025, 3, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezo, D.; Ríos, N. Silvopastoral Systems for Intensifying Cattle Production and Enhancing Forest Cover: The Case of Costa Rica [Internet]. 2019. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330576239 (accessed on 1 January 2026).

- Jang, E.K.; Kwak, D.; Choi, G.; Moon, J. Opportunities and challenges of converging technology and blended finance for REDD+ implementation. Front. For. Glob. Change 2023, 6, 1154917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Terms and Definitions FRA 2025; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/a6e225da-4a31-4e06-818d-ca3aeadfd635/content (accessed on 1 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.