Soil Carbon Storage in Forest and Grassland Ecosystems Along the Soil-Geographic Transect of the East European Plain: Relation to Soil Biological and Physico-Chemical Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

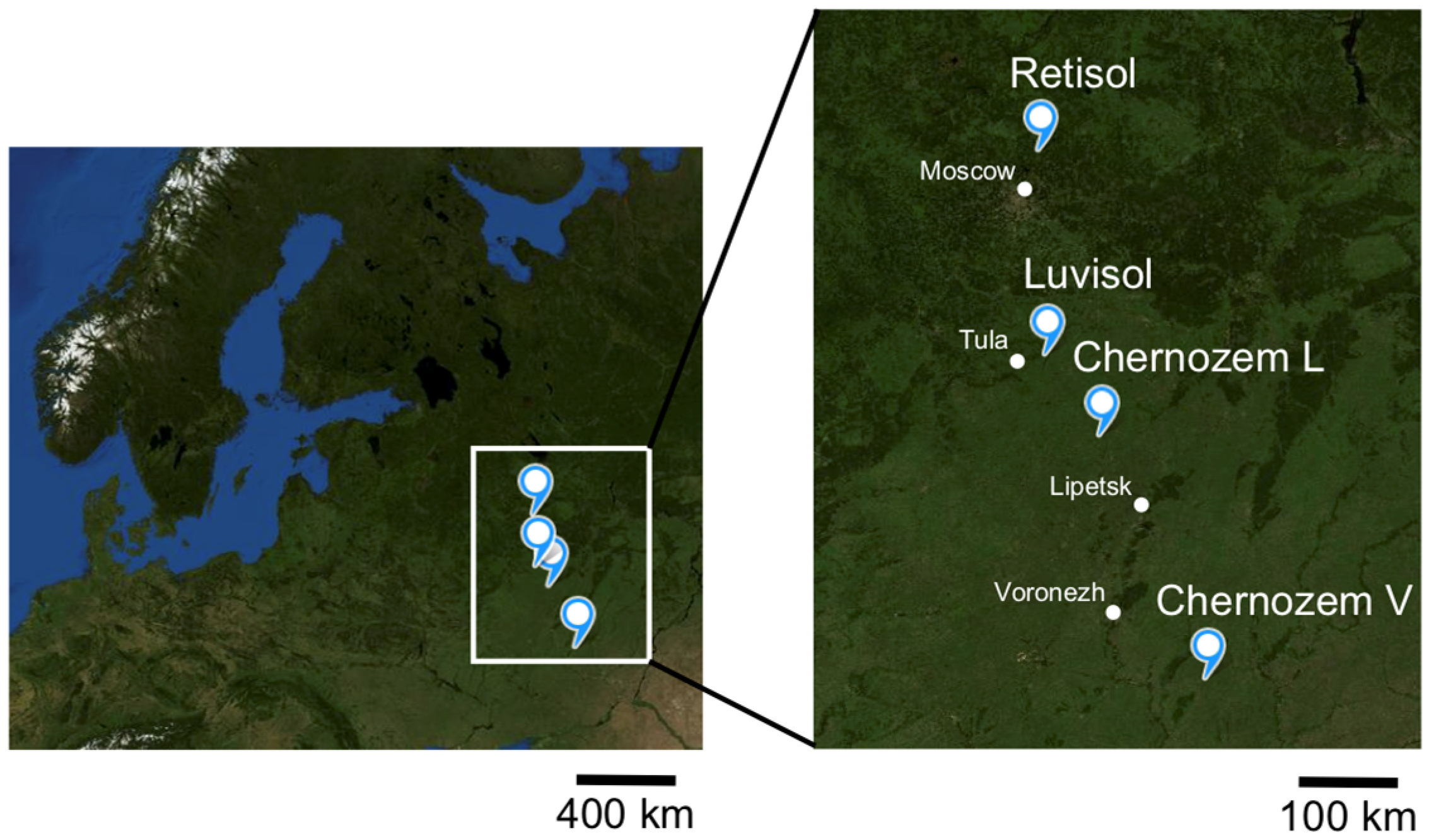

2.1. Study Area

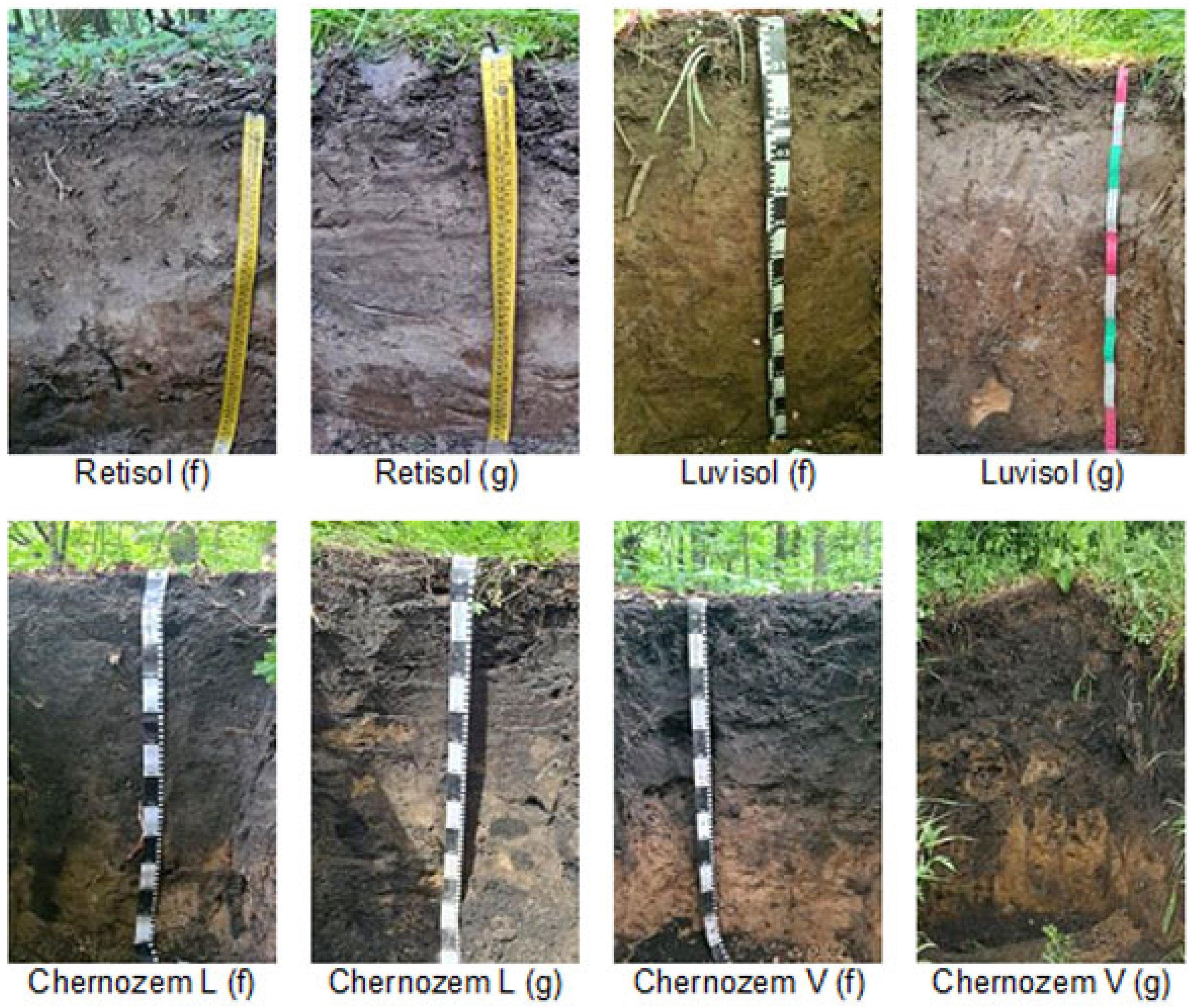

2.2. Soil Samples Collection

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Soil Physico-Chemical Properties

2.5. Contents and Storage of Total Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen

2.6. Humus Fractional Composition

2.7. Isolation of Culturable Bacteria and Microscopic Fungi

2.8. Measurement of Soil Respiration and Determination of Microbial Biomass

2.9. Community-Level Physiological Profiling (CLPP-Assay)

2.10. Laccase Activity

2.11. Dehydrogenase Activity Assay

2.12. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physico-Chemical Characteristics

3.2. Total Organic Carbon, Total Nitrogen Content, and Storage

3.3. Humus Fractional Composition

3.4. Soil Biological Properties

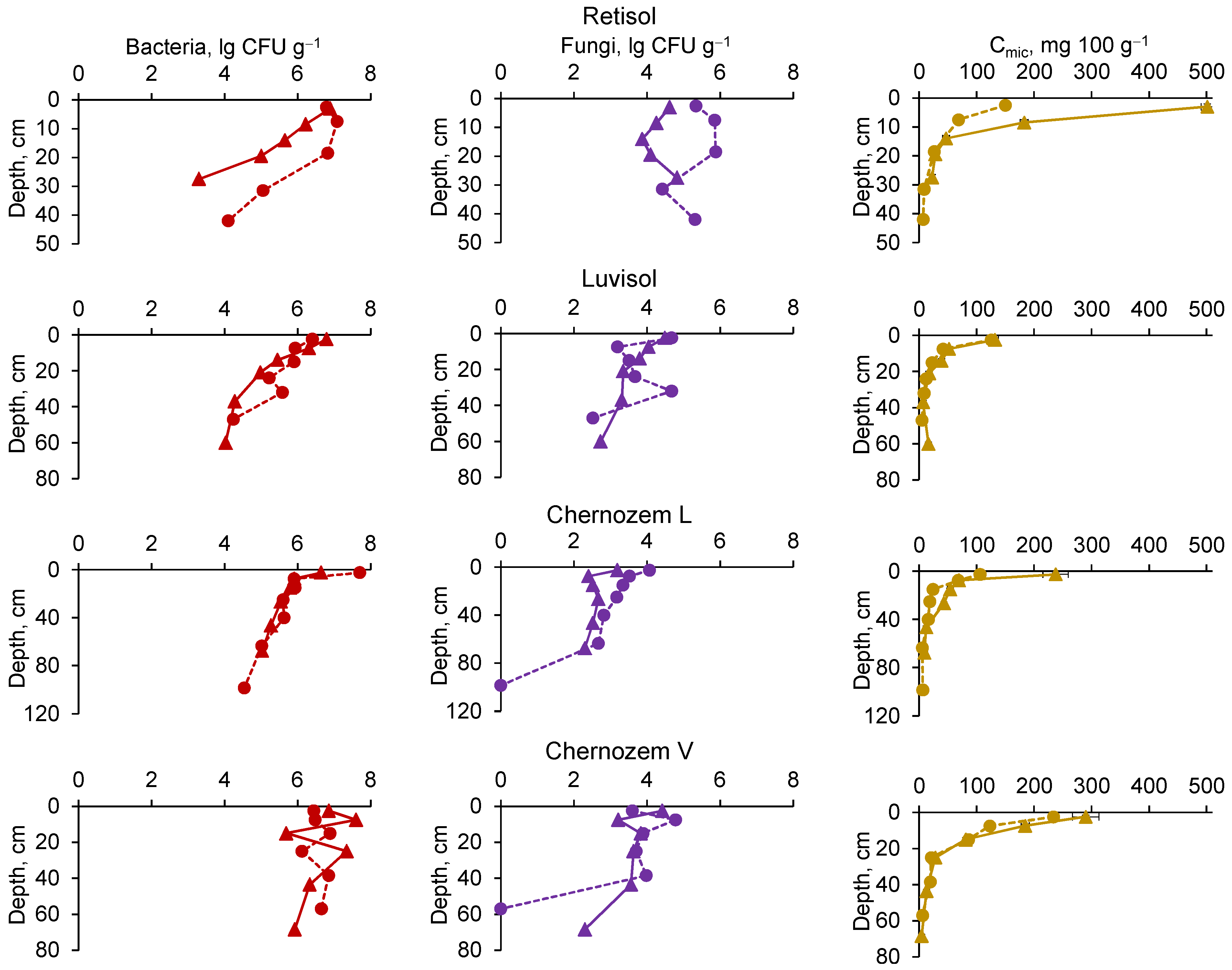

3.4.1. Culturable Fungi and Bacteria and Microbial Biomass Content

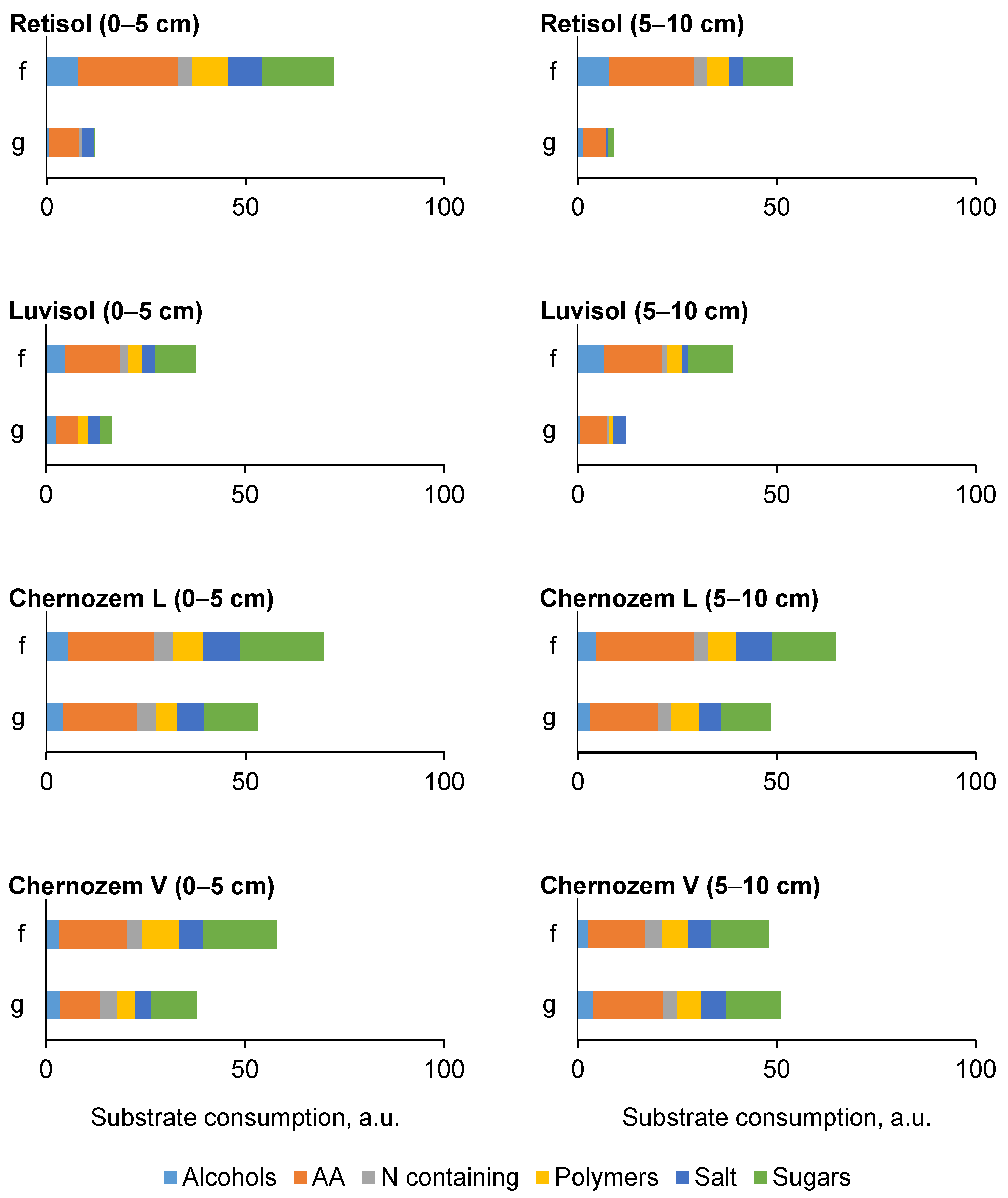

3.4.2. Community-Level Physiological Profiling

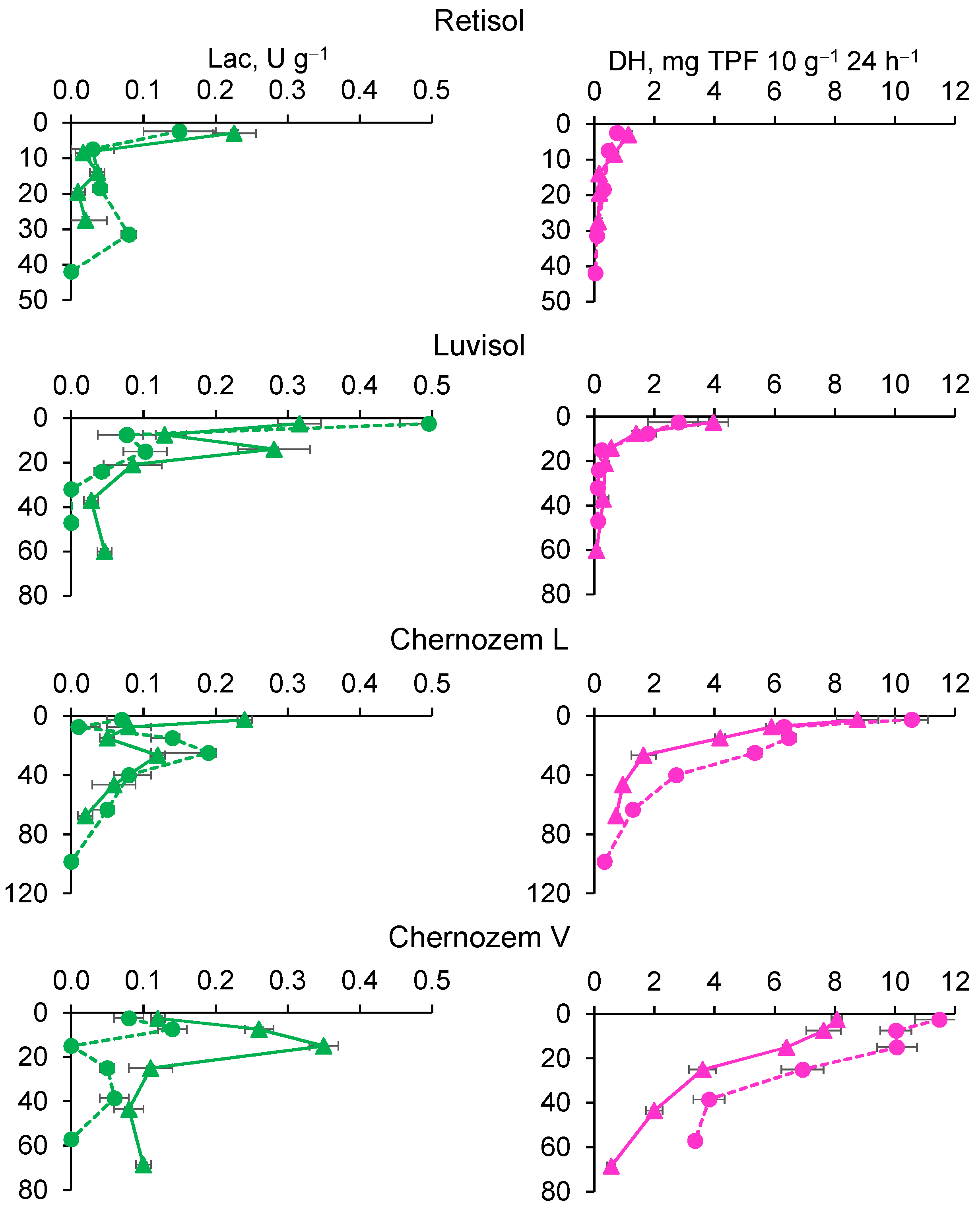

3.4.3. Laccase and Dehydrogenase Activities

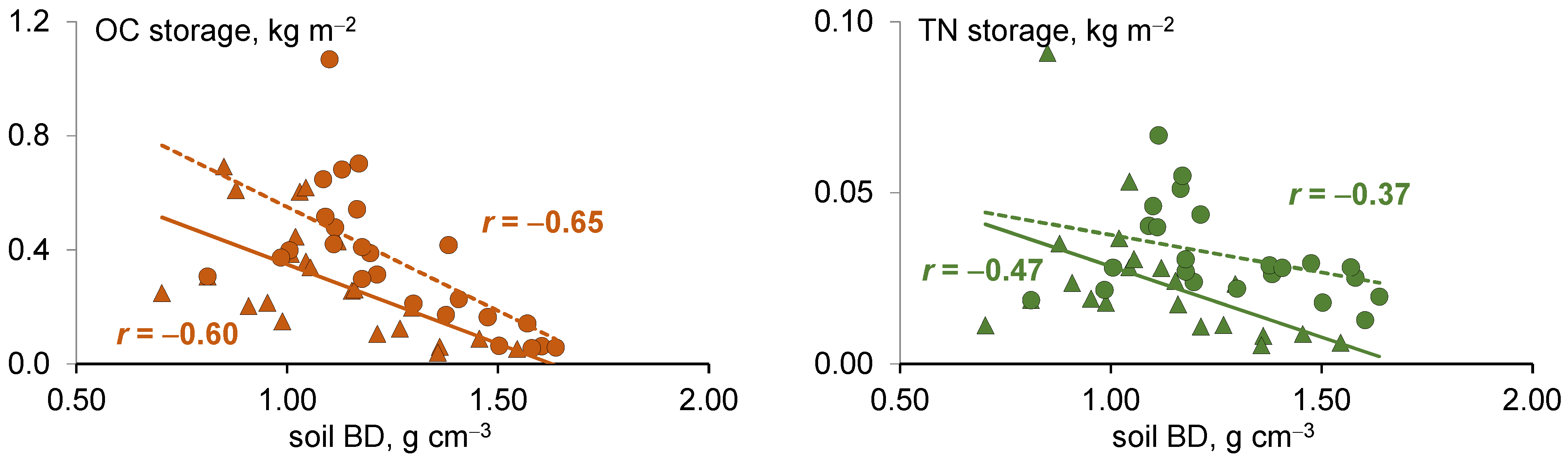

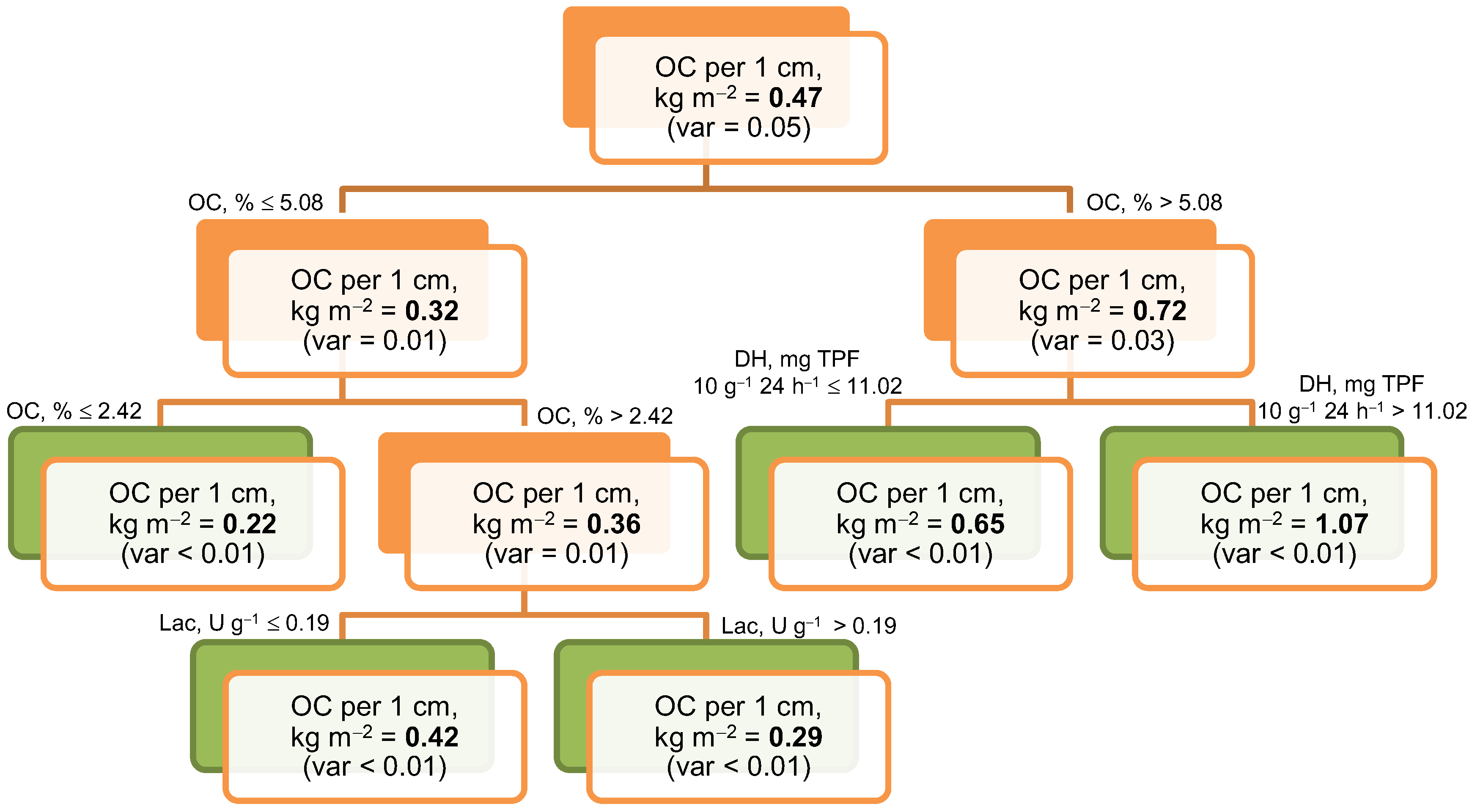

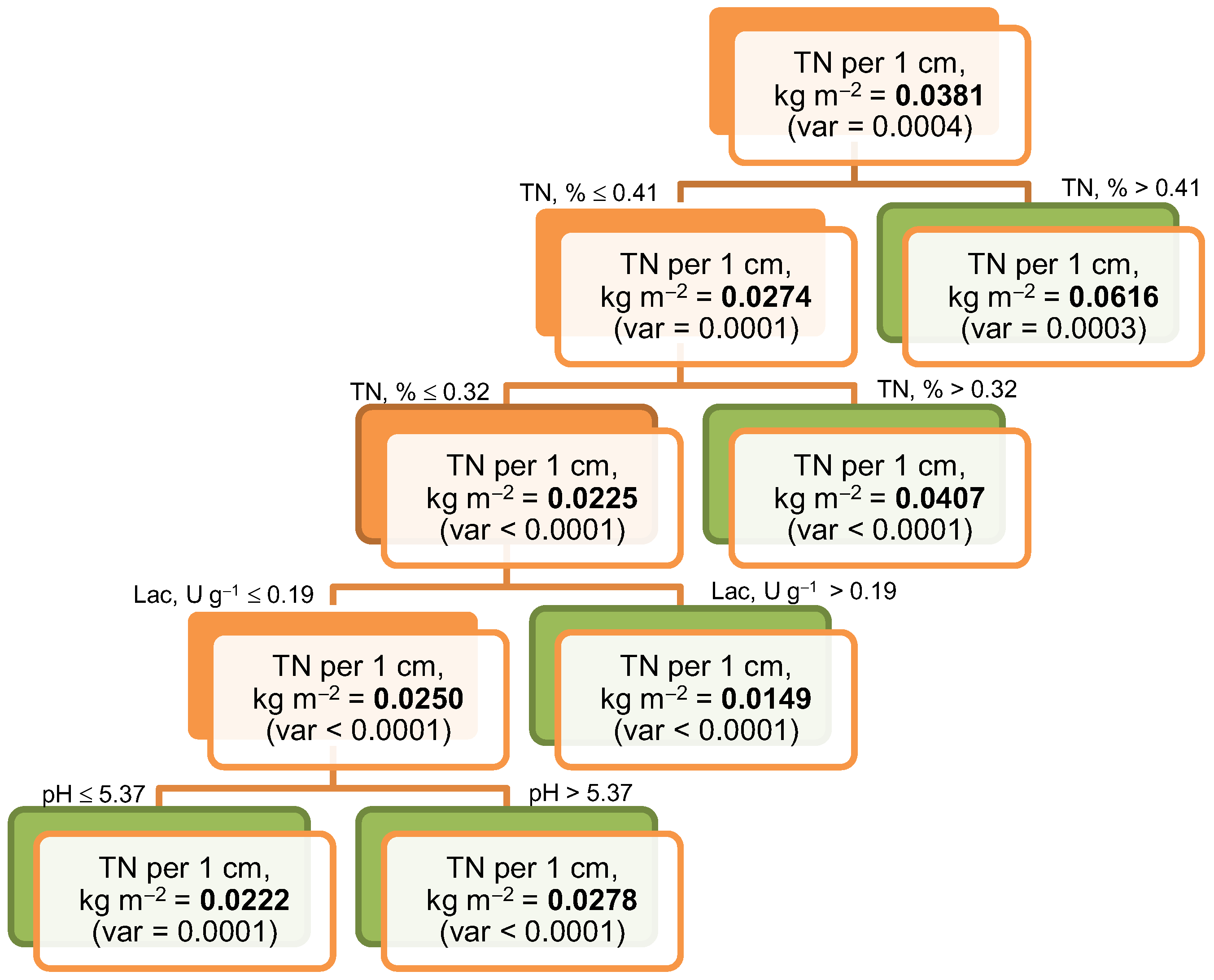

3.5. Relationships Between Organic Carbon and Total Nitrogen Storage and Soil Properties

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AA | Amino acid |

| BD | Bulk density |

| DH | Dehydrogenase activity |

| FAs | Fulvic acids |

| HAs | Humic acids |

| HSs | Humic substances |

| Lac | Laccase activity |

| OC | Organic carbon |

| SOM | Soil organic matter |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| TTC | 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride |

| CLPP | Community-level physiological profiling assay |

| ABTS | 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline)-6-sulfonic acid |

| TBT | Triphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| R2A | Reasoner 2A |

| TPF | Triphenylformazan |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| CART | Classification and Regression Tree |

References

- Batjes, N.H. Total carbon and nitrogen in the soils of the world. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 65, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, H.Y.; Chen, C.; Ma, Z.; Searle, E.B.; Yu, Z.; Huang, Z. Effects of plant diversity on soil carbon in diverse ecosystems: A global meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 2020, 95, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, K.; Lal, R. Carbon Sequestration in Forest Ecosystems; Springer: Dordrecht, Germany, 2010; 289p. [Google Scholar]

- Eze, S.; Palmer, S.M.; Chapman, P.J. Soil organic carbon stock in grasslands: Effects of inorganic fertilizers, liming and grazing in different climate settings. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrumpf, M.; Schulze, E.D.; Kaiser, K.; Schumacher, J. How accurately can soil organic carbon stocks and stock changes be quantified by soil inventories? Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 1193–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricard, M.F.; Viglizzo, E.F. Improving carbon sequestration estimation through accounting carbon stored in grassland soil. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bárcena, T.G.; Kiær, L.P.; Vesterdal, L.; Stefánsdóttir, H.M.; Gundersen, P.; Sigurdsson, B.D. Soil carbon stock change following afforestation in Northern Europe: A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2014, 20, 2393–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padbhushan, R.; Sharma, S.; Rana, D.S.; Kumar, U.; Kohli, A.; Kumar, R. Delineate soil characteristics and carbon pools in grassland compared to native forestland of India: A meta-analysis. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokołowska, J.; Józefowska, A.; Woźnica, K.; Zaleski, T. Succession from meadow to mature forest: Impacts on soil biological, chemical and physical properties—Evidence from the Pieniny Mountains, Poland. Catena 2020, 189, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Chang, S.X.; Cai, Z.; Mueller, C.; Zhang, J. Nitrogen deposition affects both net and gross soil nitrogen transformations in forest ecosystems: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 244, 608–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Yuan, J.; Liu, S.; Xu, G.; Lu, Y.; Yan, L.; Li, G. Soil carbon and nitrogen pools and their storage characteristics under different vegetation restoration types on the Loess Plateau of Longzhong, China. Forests 2024, 15, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhu, G.; Tang, Z.; Shangguan, Z. Global patterns of the effects of land-use changes on soil carbon stocks. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 5, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.G.; Kirschbaum, M.U.; Eichler-Loebermann, B.; Gifford, R.M.; Liáng, L.L. The effect of land-use change on soil C, N, P, and their stoichiometries: A global synthesis. Agricult. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 348, 108402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickels, M.C.L.; Prescott, C.E. Soil carbon stabilization under coniferous, deciduous and grass vegetation in post-mining reclaimed ecosystems. Front. For. Glob. Change 2021, 4, 689594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billings, S.A. Soil organic matter dynamics and land use change at a grassland/forest ecotone. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 2934–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeplau, C.; Don, A.; Vesterdal, L.; Leifeld, J.; Van Wesemael, B.; Schumacher, J.; Gensior, A. Temporal dynamics of soil organic carbon after land-use change in the temperate zone—Carbon response functions as a model approach. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 2415–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, W.; Liu, W. Comparing the effect of naturally restored forest and grassland on carbon sequestration and its vertical distribution in the Chinese Loess Plateau. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Don, A.; Schumacher, J.; Freibauer, A. Impact of tropical land-use change on soil organic carbon stocks—A meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1658–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignac, M.F.; Derrien, D.; Barré, P.; Barot, S.; Cécillon, L.; Chenu, C.; Basile-Doelsch, I. Increasing soil carbon storage: Mechanisms, effects of agricultural practices and proxies. A review: Soil C storage: Mechanisms, practices and proxies. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 37, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhongaray, G.; Alvarez, R. Soil carbon sequestration of Mollisols and Oxisols under grassland and tree plantations in South America-A review. Geoderma Regional 2019, 18, e00226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, C.; Vesterdal, L.; Gianelle, D.; Rodeghiero, M. Changes in soil organic carbon and nitrogen following forest expansion on grassland in the Southern Alps. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 328, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basile-Doelsch, I.; Balesdent, J.; Pellerin, S. Reviews and syntheses: The mechanisms underlying carbon storage in soil. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 5223–5242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saviozzi, A.; Levi-Minzi, R.; Cardelli, R.; Riffaldi, R. A comparison of soil quality in adjacent cultivated, forest and native grassland soils. Plant Soil 2001, 233, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Trasar-Cepeda, C.; Leirós, M.C.; Seoane, S.; Gil-Sotres, F. Biochemical properties of acid soils under native grassland in a temperate humid zone. New Zealand J. Agricult. Res. 2007, 50, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.; Maiti, S.K. Different soil factors influencing dehydrogenase activity in mine degraded lands—State-of-art review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2021, 232, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavarzina, A.G.; Kulikova, N.A.; Trubitsina, L.I.; Belova, O.V.; Pyatova, M.I.; Danilin, I.V.; Pogozhev, P.E.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Lisov, A.V. Disentangling two and three domain laccases in soils: Contribution of fungi, bacteria and abiotic processes to oxidative activities. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2025, 208, 109861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, O.I.; Kholodov, V.A.; Safronova, N.A.; Yudina, A.V.; Kulikova, N.A. Particle-size, microaggregate-size, and aggregate-size distributions in humus horizons of the zonal sequence of soils in european russia. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burst, M.; Chauchard, S.; Dambrine, E.; Dupouey, J.L.; Amiaud, B. Distribution of soil properties along forest-grassland interfaces: Influence of permanent environmental factors or land-use after-effects? Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 289, 106739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, P.; Yu, Y.; Ding, F. A synthesis of change in deep soil organic carbon stores with afforestation of agricultural soils. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 296, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, D.S.; Grishina, L.A. Manual on Humus Chemistry; Moscow University Press: Moscow, Russia, 1981; 183p. [Google Scholar]

- Slepetiene, A.; Slepetys, J. Status of humus in soil under various long-term tillage systems. Geoderma 2005, 127, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slepetiene, A.; Butkute, B. Use of multichannel photometer (Multiskan MS) for determination of humic materials in soil after their dichromate oxidation. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 375, 1260–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reasoner, D.J.; Geldreich, E. A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1985, 49, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, M.P.; Patil, R.H.; Maheshwari, V.L. A novel and sensitive agar plug assay for screening of asparaginase-producing en-dophytic fungi from Aegle marmelos. Acta Biol. Szeged. 2012, 56, 175–177. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.P.E.; Domsch, K.H. A physiological method for the quantitative measurement of microbial biomass in soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1978, 10, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheptsov, V.S.; Vorobyova, E.A.; Osipov, G.A.; Manucharova, N.A.; Polyanskaya, L.M.; Gorlenko, M.V.; Pavlov, A.K.; Rosanova, M.S.; Lomasov, V.N. Microbial activity in Martian analog soils after ionizing radiation: Implications for the preserva-tion of subsurface life on Mars. AIMS Microbiol. 2018, 4, 541–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedor, P.; Zvaríková, M. Biodiversity indices. Encycl. Ecol. 2019, 2, 337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Casida, L.; Klein, D.; Santoro, T. Soil dehydrogenase activity. Soil Sci. 1964, 98, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błońska, E.; Lasota, J.; Gruba, P. Effect of temperate forest tree species on soil dehydrogenase and urease activities in relation to other properties of soil derived from loess and glaciofluvial sand. Ecol. Res. 2016, 31, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Dai, G.; Zhu, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, L.; Lü, X.; Feng, X. Vertical variations in plant-and microbial-derived carbon components in grassland soils. Plant Soil 2020, 446, 441–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lăcătuşu, A.R.; Domnariu, H.; Paltineanu, C.; Dumitru, S.; Vrînceanu, A.; Moraru, I.; Marica, D. Influence of some environmental variables on organic carbon and nitrogen stocks in grassland mineral soils from various temperate-climate ecosystems. Environ. Exp. Botany 2024, 217, 105554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Hua, Y.; Sarwar, M.T.; Yang, H. Nanoscale interactions of humic acid and minerals reveal mechanisms of carbon protection in soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley, M.C.; Grand, S.; Verrecchia, É.P. Calcium-mediated stabilisation of soil organic carbon. Biogeochemistry 2018, 137, 27–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Hue, N.V. Ameliorating subsoil acidity by surface application of calcium fulvates derived from common organic materials. Biol. Fert. Soils 1996, 21, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yao, Y.; Yang, Y. Fulvic acid-like substance-Ca (II) complexes improved the utilization of calcium in rice: Chelating and absorption mechanism. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 237, 113502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Shangguan, Z.; Chang, F.; Jia, F.A.; Deng, L. Effects of grassland afforestation on structure and function of soil bacterial and fungal communities. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 676, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; He, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, D.; Zhang, R.; Yang, S. Pedogenic carbonate and soil dehydrogenase activity in response to soil organic matter in Artemisia ordosica community. Pedosphere 2010, 20, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuerl, S.; Buscot, F. Laccases: Toward disentangling their diversity and functions in relation to soil organic matter cycling. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2010, 46, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, S.; Zhuang, Q.; Yang, Z.; Gan, C.; Jin, X. Process-based modeling of forest soil carbon dynamics. Forests 2025, 16, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Guan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, X.; Shi, D.; Zhang, M. Response of topsoil organic carbon in the forests of Northeast China under future climate scenarios. Forests 2024, 15, 2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Biome, Average Annual Temperature and Precipitation | Soil Index | Soil Reference Group * WRB 2022 | Ecosystem | Dominant Species | GPS Coordinates, DD/ Altitude, m a.s.l. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern taiga 3.5–5.8 °C, 500–700 mm | Retisol (f) | Retisol (Loamic, Cutanic) | forest | trees: Picea abies (L.) H. Karst., Betula pendula Roth; herbs: Oxalis acetosella L., Aegopodium podagraria L., Asarum europaeum L. | 56.227922 37.953847/ 205 |

| Retisol (g) | Retisol (Loamic, Cutanic) | grassland | Poa pratensis L. | 56.228078 37.953366/ 200 | |

| Broadleaf forest +4.0 °C 550–600 mm | Luvisol (f) | Albic Luvisol (Loamic, Cutanic) | forest | trees: Tilia cordata Mill., Fraxinus excelsior L., Quercus robur L.; Corylus avellana L., Acer platanoides L.; herbs: Mercurialis perennis L. | 53.973211 37.181616/ 180 |

| Luvisol (g) | Albic Luvisol (Loamic Cutanic, Aric) | grassland | Elytrigia repens (L.) Nevski, Poa palustris L., Poa pratensis L. | 53.93623 37.187284/ 180 | |

| Forest–steppe +4.5 °C 450–500 mm | Chernozem L (f) | Luvic Calcic Chernozem (Loamic, Pachic) | forest | trees: Acer platanoides L., Acer campestre L., Tilia cordata Mill.; shrubs: Prunus padus L. | 53.505994 38.978772/ 145 |

| Chernozem L (g) | Vermic Hypocalcic Chernozem (Loamic, Hyperhumic) | grassland | Poa angustifolia L. | 53.505994 38.979772/ 145 | |

| Steppe +5.7 °C 470 mm | Chernozem V (f) | Vermic Luvic Endocalcic Chernozem (Clayic, Pachic) | forest | trees: Acer campestre L., Quercus robur L. | 51.02908 40.72758/ 150 |

| Chernozem V (g) | Vermic Calcic Chernozem (Loamic, Pachic) | grassland | Festuca valesiaca Schleich. ex Gaudin. | 51.02900 40.72617/ 150 |

| Soil Index | Horizon | Soil Moisture, % | pH (H2O) | Density, g cm−3 | Clay Content, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retisol (f) | Ah (0–6 cm) | 44.3 ± 4.1 | 4.57 ± 0.02 | 0.70 ± 0.18 | 9 ± 2 |

| A (6–11 cm) | 29.8 ± 4.6 | 4.74 ± 0.03 | 0.95 ± 0.19 | 10 ± 2 | |

| AE (11–17 cm) | 23.8 ± 0.9 | 4.88 ± 0.03 | 1.30 ± 0.15 | 10 ± 4 | |

| E (17–22 cm) | 18.8 ± 2.1 | 5.03 ± 0.02 | 1.46 ± 0.17 | 9 ± 5 | |

| Ebtg (22–33 cm) | 18.9 ± 1.2 | 5.05 ± 0.03 | 1.54 ± 0.16 | 12 ± 2 | |

| Retisol (g) | Ap1 (0–5 cm) | 27.7 ± 4.3 | 5.16 ± 0.03 | 1.20 ± 0.24 | 8 ± 2 |

| Ap2 (5–10 cm) | 24.5 ± 2.3 | 5.57 ± 0.02 | 1.38 ± 0.15 | 8 ± 1 | |

| Ap3 (10–27 cm) | 25.3 ± 1.0 | 5.35 ± 0.02 | 1.38 ± 0.13 | 8 ± 2 | |

| E (27–36 cm) | 20.0 ± 0.4 | 5.14 ± 0.03 | 1.60 ± 0.12 | 8 ± 2 | |

| Ebt (36–48 cm) | 19.6 ± 0.3 | 4.92 ± 0.03 | 1.58 ± 0.18 | 13 ± 4 | |

| Luvisol (f) | Ah (0–5 cm) | 29.5 ± 1.4 | 5.43 ± 0.01 | 0.81 ± 0.18 | 8 ± 2 |

| A (5–10 cm) | 28.9 ± 2.2 | 5.16 ± 0.03 | 0.91 ± 0.12 | 9 ± 3 | |

| A (10–18 cm) | 32.2 ± 1.0 | 4.93 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 9 ± 4 | |

| AE (18–24 cm) | 23.9 ± 1.2 | 4.78 ± 0.01 | 1.21 ± 0.20 | 10 ± 1 | |

| Ebt (24–50 cm) | 17.7 ± 0.4 | 4.72 ± 0.02 | 1.36 ± 0.14 | 11 ± 4 | |

| Bt (50–70 cm) | 22.5 ± 0.1 | 4.67 ± 0.02 | 1.36 ± 0.17 | 11 ± 4 | |

| Luvisol (g) | Ah (0–5 cm) | 31.4 ± 2.2 | 5.69 ± 0.03 | 1.21 ± 0.19 | 8 ± 2 |

| Ap (5–10 cm) | 21.9 ± 1.1 | 5.62 ± 0.02 | 1.41 ± 0.15 | 9 ± 2 | |

| Ap (10–20 cm) | 18.1 ± 0.4 | 5.61 ± 0.03 | 1.48 ± 0.14 | 10 ± 2 | |

| Ap (20–28 cm) | 16.0 ± 1.5 | 5.71 ± 0.01 | 1.57 ± 0.15 | 10 ± 2 | |

| AE (28–36 cm) | 15.5 ± 0.8 | 5.29 ± 0.07 | 1.64 ± 0.14 | 9 ± 3 | |

| Ebt (36–58 cm) | 16.2 ± 0.8 | 4.95 ± 0.03 | 1.50 ± 0.14 | 10 ± 4 | |

| Chernozem L (f) | Ah (0–5 cm) | 17.4 ± 0.9 | 6.28 ± 0.02 | 0.88 ± 0.12 | 14 ± 3 |

| Ah (5–10 cm) | 12.0 ± 0.6 | 6.38 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.15 | 14 ± 1 | |

| Ah (10–20 cm) | 12.8 ± 0.7 | 6.13 ± 0.01 | 1.04 ± 0.12 | 18 ± 2 | |

| Ah (20–33 cm) | 14.8 ± 0.6 | 5.81 ± 0.03 | 1.06 ± 0.19 | 20 ± 1 | |

| Abh (33–60 cm) | 14.4 ± 0.2 | 5.24 ± 0.07 | 1.15 ± 0.23 | 20 ± 4 | |

| Bt (60–75 cm) | 12.1 ± 0.3 | 5.36 ± 0.01 | 1.27 ± 0.16 | 16 ± 3 | |

| Chernozem L (g) | Ah (0–5 cm) | 15.9 ± 1.8 | 6.24 ± 0.02 | 1.09 ± 0.12 | 16 ± 2 |

| Ah (5–10 cm) | 15.6 ± 0.9 | 6.32 ± 0.01 | 1.11 ± 0.16 | 20 ± 1 | |

| Ah (10–20 cm) | 14.6 ± 0.4 | 6.87 ± 0.03 | 1.17 ± 0.18 | 19 ± 3 | |

| Ah (20–30 cm) | 14.7 ± 0.4 | 6.75 ±0.04 | 1.01 ± 0.20 | 21 ± 1 | |

| Ah (30–50 cm) | 16.7 ± 0.4 | 6.77 ± 0.10 | 0.99 ± 0.15 | 20 ± 1 | |

| Abh (50–77 cm) | 14.6 ± 0.3 | 6.68 ± 0.02 | 1.18 ± 0.19 | 19 ± 2 | |

| Bk (77–120 cm) | 13.8 ± 0.3 | 7.39 ± 0.05 | 1.30 ± 0.13 | – | |

| Chernozem V (f) | Ah (0–5 cm) | 50.7 ± 2.3 | 7.20 ± 0.03 | 0.85 ± 0.16 | 15 ± 1 |

| Ah (5–10 cm) | 36.1 ± 1.1 | 7.33 ± 0.03 | 1.03 ± 0.14 | 17 ± 2 | |

| Ah (10–20 cm) | 26.8 ± 1.2 | 7.08 ± 0.02 | 1.04 ± 0.15 | 21 ± 3 | |

| Ah (20–30 cm) | 22.5 ± 0.9 | 7.32 ± 0.04 | 1.02 ± 0.12 | 23 ± 3 | |

| Abh (30–57 cm) | 16.4 ± 0.4 | 6.66 ± 0.03 | 1.12 ± 0.13 | 23 ± 3 | |

| Bt (57–80 cm) | 12.1 ± 0.2 | 6.39 ± 0.04 | 1.16 ± 0.15 | 22 ± 1 | |

| Chernozem V (g) | Ah (0–5 cm) | 30.9 ± 1.3 | 6.87 ± 0.01 | 1.10 ± 0.18 | 17 ± 2 |

| Ah (5–10 cm) | 36.1 ± 1.2 | 6.67 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.16 | 19 ± 2 | |

| Ah (10–20 cm) | 18.2 ± 0.5 | 6.18 ± 0.01 | 1.17 ± 0.21 | 20 ± 1 | |

| Ah (20–30 cm) | 14.9 ± 0.7 | 6.21 ± 0.02 | 1.09 ± 0.16 | 21 ± 1 | |

| Ah (30–47 cm) | 19.1 ± 0.6 | 7.13 ± 0.01 | 1.11 ± 0.15 | 22 ± 1 | |

| Bk (47–67 cm) | 12.9 ± 0.5 | 7.20 ± 0.03 | 1.18 ± 0.13 | 22 ± 3 | |

| LSD 0.05 * | 3.5 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 1 |

| Soil Index | Horizon (Depth, cm) | OC | TN | C/N | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | kg m−2 | % | kg m−2 | |||

| Retisol (f) | Ah (0–6) | 3.53 ± 0.01 | 1.49 | 0.16 ± 0.06 | 0.07 | 22 |

| A (6–11) | 2.25 ± 0.11 | 1.07 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.10 | 11 | |

| AE (11–17) | 1.52 ± 0.14 | 1.18 | 0.18 ± 0.01 | 0.14 | 8 | |

| E (17–22) | 0.61 ± 0.11 | 0.44 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 0.04 | 10 | |

| Ebtg (22–33) | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.57 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.07 | 8 | |

| Retisol (g) | Ap (10–5) | 3.25 ± 0.08 | 1.94 | 0.20 ± 0.02 | 0.12 | 16 |

| Ap2 (5–10) | 3.02 ± 0.11 | 2.09 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.13 | 16 | |

| Ap3 (10–27) | 1.26 ± 0.08 | 2.94 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.49 | 6 | |

| E (27–36) | 0.39 ± 0.01 | 0.56 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.12 | 5 | |

| Ebt (36–48) | 0.36 ± 0.04 | 0.67 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.30 | 2 | |

| Luvisol (f) | Ah (0–5) | 3.78 ± 0.01 | 1.53 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.09 | 16 |

| A (5–10) | 2.23 ± 0.15 | 1.01 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.12 | 9 | |

| A (10–18) | 1.51 ± 0.20 | 1.19 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.14 | 8 | |

| AE (18–24) | 0.87 ± 0.08 | 0.63 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.07 | 10 | |

| Ebt (24–50) | 0.44 ± 0.07 | 1.56 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.21 | 7 | |

| Bt (50–70) | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.77 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.11 | 7 | |

| Luvisol (g) | Ah (0–5) | 2.59 ± 0.06 | 1.57 | 0.36 ± 0.12 | 0.22 | 7 |

| Ap (5–10) | 1.62 ± 0.06 | 1.14 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.14 | 8 | |

| Ap (10–20) | 1.12 ± 0.01 | 1.64 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.30 | 6 | |

| Ap (20–28) | 0.91 ± 0.06 | 1.14 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 0.23 | 5 | |

| AE (28–36) | 0.35 ± 0.03 | 0.46 | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.16 | 3 | |

| Ebt (36–58) | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 1.42 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.40 | 4 | |

| Chernozem L (f) | Ah (0–5) | 6.93 ± 0.13 | 3.05 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | 0.18 | 17 |

| Ah (5–10) | 3.82 ± 0.16 | 1.93 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | 0.14 | 13 | |

| Ah (10–20) | 3.44 ± 0.02 | 3.59 | 0.27 ± 0.04 | 0.28 | 13 | |

| Ah (20–33) | 3.21 ± 0.06 | 4.40 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.40 | 11 | |

| Abh (33–60) | 2.23 ± 0.10 | 6.94 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.65 | 11 | |

| Bt (60–75) | 0.98 ± 0.06 | 1.86 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.17 | 11 | |

| Chernozem L (g) | Ah (0–5) | 5.97 ± 0.03 | 3.24 | 0.40 ± 0.14 | 0.33 | 15 |

| Ah (5–10) | 4.30 ± 0.13 | 2.39 | 0.60 ± 0.05 | 0.33 | 7 | |

| Ah (10–20) | 4.65 ± 0.06 | 5.42 | 0.44 ± 0.05 | 0.51 | 11 | |

| Ah (20–30) | 3.97 ± 0.18 | 3.99 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.28 | 14 | |

| Ah (30–50) | 3.79 ± 0.18 | 7.46 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 0.43 | 17 | |

| Abh (50–77) | 2.54 ± 0.08 | 8.06 | 0.23 ± 0.02 | 0.73 | 11 | |

| Bk (77–120) | 1.64 ± 0.09 | 9.13 | 0.17 ± 0.02 | 0.95 | 10 | |

| Chernozem V (f) | Ah (0–5) | 8.14 ± 0.84 | 3.46 | 1.07 ± 0.32 | 0.45 | 8 |

| Ah (5–10) | 5.86 ± 0.94 | 3.02 | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 0.27 | 11 | |

| Ah (10–20) | 5.93 ± 0.35 | 6.19 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.53 | 12 | |

| Ah (20–30) | 4.37 ± 0.11 | 4.46 | 0.36 ± 0.01 | 0.37 | 12 | |

| Abh (30–57) | 3.83 ± 0.28 | 11.6 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.76 | 15 | |

| Bt (57–80) | 2.25 ± 0.18 | 6.00 | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.40 | 15 | |

| Chernozem V (g) | Ah (0–5) | 9.71 ± 0.55 | 5.34 | 0.42 ± 0.06 | 0.23 | 23 |

| Ah (5–10) | 6.04 ± 0.17 | 3.41 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.25 | 14 | |

| Ah (10–20) | 6.01 ± 0.19 | 7.03 | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 0.55 | 13 | |

| Ah (20–30) | 4.74 ± 0.04 | 5.17 | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.40 | 13 | |

| Ah (30–47) | 3.79 ± 0.16 | 7.15 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.68 | 11 | |

| Bk (47–67) | 3.48 ± 0.19 | 8.19 | 0.26 ± 0.01 | 0.61 | 13 | |

| LSD 0.05 * | 0.75 | 0.07 | ||||

| Parameter | Retisol | Luvisol | Chernozem L | Chernozem V | LSD 0.05 * | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f | g | f | g | f | g | f | g | ||

| Humus 1, % | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 6.8 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.1 | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.1 | 0.1 |

| HA1, % | 15.5 ± 0.2 | 13.5 ± 0.4 | 10.2 ± 0.2 | 3.9 ± 0.2 | 10.3 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 0.2 |

| HA2, % | 0 | 0 | 6.3 ± 0.8 | 19.5 ± 0.8 | 17.5 ± 0.7 | 19.0 ± 0.7 | 19.0 ± 0.8 | 28.3 ± 0.7 | 0.8 |

| HA3, % | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 11.2 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 0.3 |

| ΣHA, % | 16.4 ± 0.3 | 14.3 ± 0.4 | 22.0 ± 0.4 | 25.4 ± 0.4 | 37.4 ± 0.4 | 31.0 ± 0.3 | 25.8 ± 0.3 | 32.2 ± 0.3 | 0.3 |

| FA1, % | 16.1 ± 0.3 | 19.4 ± 0.3 | 13.3 ± 0.2 | 14.7 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 10.8 ± 0.2 | 8.8 ± 0.2 | 7.0 ± 0.2 | 0.3 |

| FA1a, % | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.3 |

| FA2, % | 5.3 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 9.8 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 7.8 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.2 |

| FA3, % | 15.0 ± 0.3 | 19.5 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.3 | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 11.5 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 0.2 | 8.4 ± 0.2 | 6.8 ± 0.2 | 0.4 |

| ΣFA, % | 38.0 ± 1.0 | 41.4 ± 1.1 | 37.7 ± 1.1 | 28.3 ±0.9 | 15.1 ± 1.0 | 25.4 ± 1.2 | 18.6 ± 1.0 | 16.5 ± 1.0 | 1.2 |

| CHA/CFA 2 | 0.43 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.58 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.02 | 2.47 ± 0.02 | 1.22 ± 0.02 | 1.39 ± 0.01 | 1.95 ± 0.01 | 0.09 |

| Humin, % | 45.6 ± 0.3 | 44.3 ± 0.2 | 40.3 ± 0.2 | 46.3 ± 0.3 | 47.5 ± 0.4 | 43.6 ± 0.2 | 55.5 ± 0.2 | 51.3 ± 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Soil Index | Depth, cm | n | W | H | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retisol (f) | 0–5 | 45 | 1.6 | 5.19 | 0.94 |

| 5–10 | 44 | 1.23 | 5.01 | 0.92 | |

| Retisol (g) | 0–5 | 11 | 1.12 | 0.90 | 0.11 |

| 5–10 | 12 | 0.75 | 0.85 | 0.25 | |

| Luvisol (f) | 0–5 | 41 | 0.92 | 4.93 | 0.92 |

| 5–10 | 38 | 1.02 | 4.80 | 0.91 | |

| Luvisol (g) | 0–5 | 21 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.61 |

| 5–10 | 15 | 0.8 | 0.93 | 0.65 | |

| Chernozem L (f) | 0–5 | 47 | 1.48 | 3.63 | 0.79 |

| 5–10 | 47 | 1.38 | 5.22 | 0.94 | |

| Chernozem L (g) | 0–5 | 44 | 1.21 | 5.27 | 0.97 |

| 5–10 | 45 | 1.08 | 5.15 | 0.94 | |

| Chernozem V (f) | 0–5 | 47 | 1.23 | 5.18 | 0.93 |

| 5–10 | 44 | 1.09 | 5.19 | 0.95 | |

| Chernozem V (g) | 0–5 | 40 | 0.95 | 5.03 | 0.95 |

| 5–10 | 46 | 1.11 | 5.27 | 0.95 |

| Soil Index | Depth, cm | BD, g cm−3 | Content, % | Storage, kg m−2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | TN | OC | TN | |||

| Retisol (f) | 0–5 | 0.70 | 3.53 | 0.16 | 1.25 | 0.06 |

| 0–10 | 0.80 | 2.92 | 0.18 | 2.35 | 0.14 | |

| 0–20 | 1.06 | 1.90 | 0.16 | 4.01 | 0.33 | |

| 0–30 | 1.21 | 1.26 | 0.11 | 4.60 | 0.40 | |

| Retisol (g) | 0–5 | 1.20 | 3.25 | 0.20 | 1.94 | 0.12 |

| 0–10 | 1.29 | 3.13 | 0.19 | 4.03 | 0.25 | |

| 0–20 | 1.33 | 2.16 | 0.20 | 5.76 | 0.54 | |

| 0–30 | 1.37 | 1.74 | 0.19 | 7.16 | 0.78 | |

| Luvisol (f) | 0–5 | 0.81 | 3.78 | 0.23 | 1.53 | 0.09 |

| 0–10 | 0.86 | 2.96 | 0.25 | 2.55 | 0.21 | |

| 0–20 | 0.95 | 2.09 | 0.20 | 3.95 | 0.38 | |

| 0–30 | 1.07 | 1.48 | 0.15 | 4.73 | 0.47 | |

| Luvisol (g) | 0–5 | 1.21 | 2.59 | 0.36 | 1.57 | 0.22 |

| 0–10 | 1.31 | 2.07 | 0.27 | 2.71 | 0.36 | |

| 0–20 | 1.39 | 1.56 | 0.23 | 4.35 | 0.65 | |

| 0–30 | 1.46 | 1.28 | 0.21 | 5.61 | 0.92 | |

| Chernozem L (f) | 0–5 | 0.88 | 6.93 | 0.40 | 3.05 | 0.18 |

| 0–10 | 0.94 | 5.27 | 0.19 | 4.97 | 0.32 | |

| 0–20 | 0.99 | 4.31 | 0.23 | 8.56 | 0.60 | |

| 0–30 | 1.01 | 3.92 | 0.25 | 11.94 | 0.91 | |

| Chernozem L (g) | 0–5 | 1.09 | 5.97 | 0.60 | 3.24 | 0.33 |

| 0–10 | 1.10 | 5.12 | 0.60 | 5.63 | 0.66 | |

| 0–20 | 1.13 | 4.88 | 0.52 | 11.05 | 1.17 | |

| 0–30 | 1.09 | 4.60 | 0.44 | 15.04 | 1.45 | |

| Chernozem V (f) | 0–5 | 0.85 | 8.14 | 1.07 | 3.46 | 0.45 |

| 0–10 | 0.94 | 6.89 | 0.48 | 6.48 | 0.73 | |

| 0–20 | 0.99 | 6.39 | 0.50 | 12.67 | 1.26 | |

| 0–30 | 1.00 | 5.70 | 0.45 | 17.13 | 1.63 | |

| Chernozem V (g) | 0–5 | 1.10 | 9.71 | 0.42 | 5.34 | 0.23 |

| 0–10 | 1.12 | 7.85 | 0.21 | 8.75 | 0.48 | |

| 0–20 | 1.14 | 6.91 | 0.34 | 15.78 | 1.03 | |

| 0–30 | 1.13 | 6.21 | 0.35 | 20.95 | 1.43 | |

| Parameter | All Studied Soils (n = 16) | Forest Soils (n = 8) | Grassland Soils (n = 8) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | TN | OC | TN | OC | TN | |

| OC, % | 0.95 | 0.62 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.43 |

| TN, % | 0.55 | 0.96 | 0.82 | 0.99 | 0.46 | 0.99 |

| Clay content, % | 0.73 | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.84 |

| pH | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.72 |

| Density, g cm−3 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.22 | −0.67 | −0.70 |

| Cmic, g kg−1 | 0.40 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.41 | 0.76 | 0.10 |

| Bacteria, CFU g−1 | 0.17 | 0.21 | −0.21 | −0.50 | 0.10 | 0.44 |

| Fungi, CFU g−1 | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.55 | 0.84 | −0.23 | −0.55 |

| Lac, U g−1 | −0.15 | −0.07 | 0.24 | −0.07 | −0.28 | −0.04 |

| DH, mg TPF 10 g−1 24−1 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 0.72 | 0.85 | 0.63 |

.

.| Group of Parameters | Parameter | All Soils (n = 16) | Forest Soils (n = 8) | Grassland Soils (n = 8) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OC | TN | OC | TN | OC | TN | ||

| Substrate consumption | Alcohols | −0.22 | −0.34 | −0.81 | −0.76 | 0.70 | 0.74 |

| AA | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.17 | −0.33 | 0.44 | 0.70 | |

| N containing | 0.60 | 0.38 | 0.77 | 0.47 | 0.80 | 0.62 | |

| Polymers | 0.26 | 0.40 | 0.53 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.94 | |

| Salt | 0.28 | 0.20 | 0.44 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.68 | |

| Sugars | 0.34 | 0.29 | 0.63 | 0.38 | 0.72 | 0.80 | |

| CLPP indexes | n | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.41 | 0.67 | 0.85 |

| W | 0.04 | −0.06 | 0.11 | −0.12 | 0.39 | 0.37 | |

| H | 0.32 | 0.26 | −0.24 | 0.12 | 0.75 | 0.77 | |

| E | −0.12 | −0.16 | 0.41 | −0.00003 | −0.78 | −0.67 | |

.

.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zavarzina, A.; Kulikova, N.; Belov, A.; Demin, V.; Rozanova, M.; Pogozhev, P.; Danilin, I. Soil Carbon Storage in Forest and Grassland Ecosystems Along the Soil-Geographic Transect of the East European Plain: Relation to Soil Biological and Physico-Chemical Properties. Forests 2026, 17, 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010069

Zavarzina A, Kulikova N, Belov A, Demin V, Rozanova M, Pogozhev P, Danilin I. Soil Carbon Storage in Forest and Grassland Ecosystems Along the Soil-Geographic Transect of the East European Plain: Relation to Soil Biological and Physico-Chemical Properties. Forests. 2026; 17(1):69. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010069

Chicago/Turabian StyleZavarzina, Anna, Natalia Kulikova, Andrey Belov, Vladimir Demin, Marina Rozanova, Pavel Pogozhev, and Igor Danilin. 2026. "Soil Carbon Storage in Forest and Grassland Ecosystems Along the Soil-Geographic Transect of the East European Plain: Relation to Soil Biological and Physico-Chemical Properties" Forests 17, no. 1: 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010069

APA StyleZavarzina, A., Kulikova, N., Belov, A., Demin, V., Rozanova, M., Pogozhev, P., & Danilin, I. (2026). Soil Carbon Storage in Forest and Grassland Ecosystems Along the Soil-Geographic Transect of the East European Plain: Relation to Soil Biological and Physico-Chemical Properties. Forests, 17(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010069