Abstract

The survival of Quercus species in the Mediterranean region is challenged by root diseases caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands and Pythium spiculum Paul, as well as by drought. This study aimed to examine the interaction between both pathogens under varying soil moisture levels. Seedlings were inoculated with P. cinnamomi, Py. spiculum, or both, and exposed to soil moisture conditions ranging from saturation to drought. Results showed that P. cinnamomi caused high levels of root necrosis in saturated-to-moderately dry soils, but it was unable to cause infection under drought conditions. Conversely, Py. spiculum infected roots under drought but not under saturation conditions and was less virulent in wet soils compared to P. cinnamomi. In seedlings inoculated with both pathogens, symptoms were similar to those induced by P. cinnamomi alone, without any synergistic effect. This study highlights that P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum infect oak roots across a range of soil moistures, with P. cinnamomi being the predominant pathogen in wet-to-moderately dry soils, and Py. spiculum being the predominant pathogen in droughted soils. Under current and projected future water deficit conditions, oak woodlands infected by both pathogens face a significant threat to their survival.

1. Introduction

Cork oaks (Quercus suber L.) have high ecological, social, and economic value in the Mediterranean Basin [1], where they are considered keystone species [2]. In the Iberian Peninsula, evergreen oaks, including Q. suber, are the dominant species of dehesa agroforestry systems (montado in Portugal), which combine cork and acorn production with extensive livestock ranching [3], leading to a typical savannah-like landscape. The Mediterranean Basin is characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, producing pronounced seasonal fluctuations in water availability [4]. Quercus species must withstand hot and dry summers for up to 4–5 months [5], but summer droughts will become a limiting factor for oak trees in dehesa under the increasing aridity predicted for the region in climate change projections [6,7]. In fact, drought-related mortality has recently emerged as a widespread issue with important implications for Mediterranean forest conservation [8,9]. However, climatic factors resulting from global climate change are not the only damaging agents acting on vegetation; other drivers with negative effects in regions with a Mediterranean climate, such as invasive microorganisms [10,11], seem to be increasing, and both climatic and biotic factors can be co-related [12]. Changes in the intensity, length, and frequency of dry periods will likely affect forest vulnerability to attacks by biotic agents [13], such as Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands, infecting highly susceptible hosts, such as oak species [14], or Pythium spiculum Paul, whose presence in the south of the Iberian Peninsula, infecting evergreen oaks, has increased in the last three decades, and they also threaten the survival of oak-based agroecosystems [15].

Phytophthora cinnamomi causes its most severe outbreaks on poorly drained or periodically waterlogged sites [16,17,18], which promote sporangial production and the zoospore release required for the spreading of disease [19]. On the other hand, species in the genus Pythium are important root pathogens of many agricultural crops, including forest nursery seedlings, and their high soil moisture requirements are like those of Phytophthora spp. [20]. Nevertheless, Py. spiculum, together with a few other Pythium spp. [21,22], does not seem to produce flagellated zoospores [23], and root infections depend on direct germination of hyphal bodies (sporangium-like structures). For this reason, its putative inability to produce swimming zoospores has led to the hypothesis that it is better adapted to terrestrial habitats compared with other oomycetes [24,25].

Phytophthora cinnamomi and Py. spiculum are frequently found in Spanish and Portuguese oak woodlands, infecting the roots of adjacent oak trees in the same site or even infecting the roots from the same oak [26]. Nothing has been reported about the influence of soil moisture in the competition between the two pathogens for Q. suber infection and root rot development. In this context, the main objective of this work was to determine the level of competition between P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum on Q. suber, and whether it is dependent on soil water content, in pot experiments. Understanding how soil moisture can determine the etiology of oak root disease should lead to a better risk assessment of root rot development in cork oak open woodlands suffering the impact of climate change in the Mediterranean Basin.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Oomycete Material

Two isolates were used in this study: PE90 of P. cinnamomi, obtained from roots of Q. ilex L. subsp. ballota (GenBank AY943301); and PA54 of Py. spiculum, obtained from the rhizosphere of Q. suber (GenBank DQ196131). Both isolates were originally collected from woodlands in southern Spain [25] and were maintained at the oomycete collection of the Agroforest Pathology Group at the University of Cordoba, Spain, stored under sterile mineral oil. Identification of the isolates was previously confirmed by ITS region sequencing and comparison with sequences in GenBank [23,25].

2.2. Plant Material

Healthy 1-year-old cork oak seedlings potted in free-draining plastic containers with 40 cells of 0.3 L were obtained from San Jerónimo Forest Nursery, belonging to the Nursery Network of the Andalusian Government, Spain.

2.3. Soil Infestation

For pot experiments, fertilized peat (Turbas y Coco Mar Menor, Sucina, pH = 5.5, ρ = 170 g L−1), a standardized substrate for the growth of Mediterranean oak seedlings, was used. The substrate was infested with three different spore suspensions: (1) chlamydospores of P. cinnamomi PE90; (2) oospores of Py. spiculum PA54; and (3) a mix of resting spores (chlamydospores and oospores) from both pathogens. For inocula preparation, each isolate was grown separately in Petri dishes containing 20 mL of 20% carrot broth and incubated at 22 °C in the dark. After 4 weeks of incubation, the mycelium produced was aseptically filtered and washed with sterile water. The mycelium mats were shaken for 3 min with sterile water in an electric mixer at the highest speed (Oster™ Pulse-matic 16, London, UK), at a rate of three Petri dishes per 100 mL water. Spore concentration was estimated by counting in a Neubauer chamber and adjusted to 8 × 103 spores (chlamydospores or oospores) per mL. For P. cinnamomi soil infestation, the chlamydospore water suspension was added to the substrate in a ratio of 33 mL L−1 of substrate, resulting in 1.5 × 103 chlamydospores of P. cinnamomi per gram of dry substrate (corresponding to 640 CFU g−1 [27]). Similarly, the water suspension containing 8·103 oospores of Py. spiculum per mL−l was added to the substrate at the same ratio, resulting in a density of 1.5 × 103 oospores per gram of dry substrate. A third infested substrate was equally prepared by adding the same quantity of both inocula together, resulting in a density of 1.5 × 103 P. cinnamomi chlamydospores plus 1.5 × 103 Py. spiculum oospores per gram of dry substrate. Uninfested substrate with only water added was used as the control. Once the soils were infested, the oak saplings were removed from their original containers and re-potted in free-draining plastic pots, each containing 3 L of infested or control substrate. A total of 40 pots containing one oak seedling per inoculum plus 40 control pots were prepared, making a total of 160 pots (including replicates).

2.4. Watering Experiments

Eight pots per inoculum type and eight control pots were submitted to five different watering treatments corresponding to five experiments according to their soil water content (θs):

- Saturation (θs = 100%): The pots were maintained in trays filled with tap water for 4 weeks, which was described as the most favourable condition for P. cinnamomi infections [28].

- High moisture (θs ≈ 90%): Maintaining the pots inside trays filled with tap water for 2 days per week, while allowing them to freely drain for the remaining 5 days. This water treatment was maintained for 12 weeks, as previously was described [28].

- Moderate moisture (θs ≈ 60%): 500 mL of tap water was added to each pot every 3 days for 12 weeks [28,29,30].

- Low moisture (θs ≈ 30%): Similar to the typical spring and summer conditions in dry Mediterranean years, obtained by adding 200 mL of tap water to each pot once a week for 24 weeks [17].

- Drought (θs ≈ 10%): Obtained by adding 50 mL of tap water per pot once a week for 20 weeks, maintaining a minimum volumetric soil water content for the survival of cork oaks [31].

All the pots were maintained in an acclimatized greenhouse (25 ± 2 °C day and 10 ± 2 °C night). To avoid cross-contamination, pots containing seedlings with different inocula were placed in separate trays. The duration of each watering regime differed because each soil moisture level reflects a distinct seasonal condition in Mediterranean forests, and symptom development occurs at different rates depending on water availability. Following previous studies on P. cinnamomi infection dynamics in Quercus spp., the duration of each experiment was adjusted to ensure that symptoms could fully develop under each specific moisture regime [17,28,29,30,31]. Therefore, disease severity was compared only within each watering treatment at its final assessment point.

2.5. Determination of Soil Water Content

To determine the exact content of water from each experiment, 8 extra pots holding 3 L (510 g) of dry substrate and submitted to each watering treatment, as described above (40 pots in total), were weighed daily for 6 weeks. The water content of the substrate (θs) for each watering treatment was calculated as the average difference in weight between the time of watering (maximum value) and the weight just before the next watering (minimum value) for each pot, expressed as a percentage.

2.6. Symptom Assessment and Data Analysis

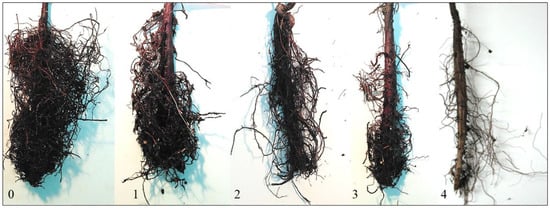

The severity of foliar symptoms was assessed weekly for each seedling according to the percentage of yellow, wilted leaves and defoliation on a 0–4 scale: 0 = 0%–10%; 1 = 11%–33%; 2 = 34%–66%; 3 = more than 67%; and 4 = dead foliage [28]. At the end of each experiment, root symptoms (Figure 1) were also assessed according to a similar 0–4 scale referring to the percentage of root necrosis or rootlet absence [28]. Segments from inoculated or control roots were plated on selective NARPH medium (17 g L−1 corn meal agar; nystatin, 27 mg; ampicillin, 272 mg; rifampicin, 10 mg; PCNB, 92 mg; and hymexazol, 50 mg) for the re-isolation of the pathogens [32].

Figure 1.

Scale (0–4) of root symptoms of Quercus suber L. seedlings inoculated with Phytophthora. cinnamomi Rands and/or Pythium spiculum Paul submitted to different soil moisture conditions.

Data of foliar and root symptoms at the end of the different experiments were tested for homoscedasticity via Levene’s test; then, a one-way ANOVA test was performed, considering inocula as factor. For each analysis, when significance was achieved (p < 0.05), mean values were compared among them via Tukey’s HSD test at α = 0.05 (Statistix software 10.0, Tallahassee, FL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Soil Water Content

The average maximum and minimum soil water content (θs) for each watering treatment were as follows: 100% for saturation; 73%–100% for high moisture; 50%–77% for moderate moisture; 25%–36% for low moisture; and 9%–12% for drought.

3.2. Inoculation Experiments

Symptoms observed in cork oak seedlings were similar to those previously described in the field or in pot experiments for oaks infected with P. cinnamomi or Py. spiculum [17,26]: leaf yellowing, wilting, and defoliation; and necrosis and death of feeder roots.

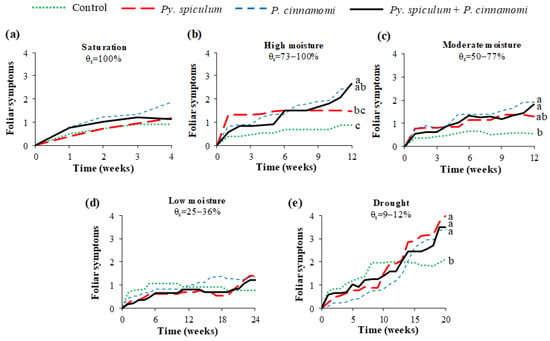

At the end of each experiment, significant differences in final foliar symptoms between inocula (Figure 2) were observed in seedlings submitted to high moisture (F = 9.70, p = 0.0001), moderate moisture (F = 6.45, p = 0.0019), and drought (F = 9.56, p = 0.0002). Under these watering conditions, all inoculated cork oaks showed higher final foliar symptoms compared to the controls, except for those inoculated with Py. spiculum under saturation, where foliar symptoms did not differ from those of the control group. In general, seedlings inoculated with P. cinnamomi showed more foliar symptoms than the controls in moisture conditions, where significant differences were detected.

Figure 2.

Evolution of foliar symptoms (0–4) of Quercus suber L. seedlings growing in uninoculated (control) soil and soils inoculated with Pythium spiculum Paul, Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands, or Py. spiculum + P. cinnamomi and submitted to five moisture conditions: (a) saturation; (b) high moisture; (c) moderate moisture; (d) low moisture; (e) drought. At the end of each experiment, lines with different letters differ significantly (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s HSD test.

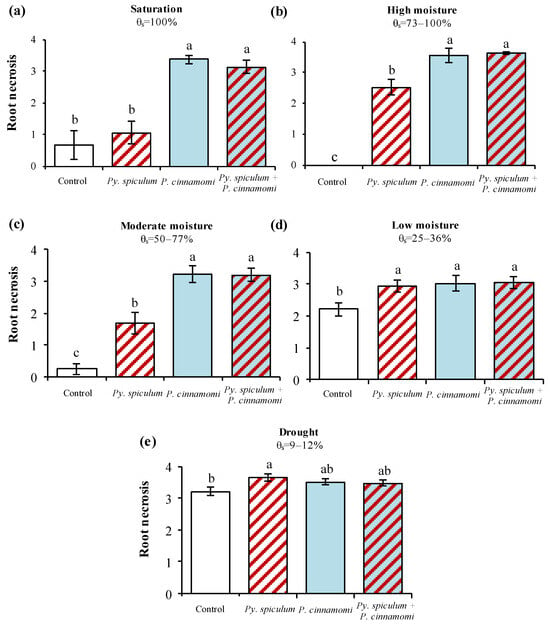

In terms of root symptoms (Figure 3), there were significant differences depending on inocula in all experiments. Under saturation (Figure 3a), only seedlings exposed to P. cinnamomi or P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum combined showed significantly higher root necrosis compared with controls (F = 20.69, p < 0.0001). For high moisture (Figure 3b), all inoculated plants presented root symptoms significantly higher than those of controls (F = 102.07, p < 0.0001), and root symptoms caused by P. cinnamomi or P. cinnamomi + Py. spiculum were significantly higher than those induced by Py. spiculum alone. Similar results were obtained for moderate moisture (Figure 3c): all the inoculated seedlings showed root symptoms significantly higher than those controls (F = 31.82, p < 0.0001), with P. cinnamomi and the mix of pathogens causing significantly higher root necrosis values than Py. spiculum alone. However, when seedlings grew under low moisture conditions (Figure 3d), no significant differences were found among the different inocula (F = 3.69, p = 0.0234). Finally, when seedlings were droughted (Figure 3e), the control plants already exhibited severe root necrosis, with average scores above 3, and only Py. spiculum induced necrosis levels significantly higher than those observed in the controls (F = 3.17, p = 0.0396).

Figure 3.

Average values of root symptoms (0–4) ± standard error recorded for cork oak seedlings growing in uninoculated soil (control) and soils inoculated with Pythium spiculum Paul, Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands, or Py. spiculum + P. cinnamomi and submitted to saturation (a), high moisture (b), moderate moisture (c), low moisture (d), and drought (e). For each graph, bars with different letters differ significantly (p < 0.05) according to Tukey’s HSD test.

3.3. Re-Isolation of Inoculated Oomycetes

In general, P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum were re-isolated from symptomatic roots from seedlings inoculated with these pathogens, either separately or mixed. Re-isolation frequencies varied from 3 to 36% of positive isolations. Nevertheless, there were a few remarkable exceptions: (i) under saturation, Py. spiculum was always absent from roots coming from seedlings inoculated with only Py. spiculum, while it was re-isolated when seedlings were inoculated with both pathogens together; and (ii) P. cinnamomi was neither re-isolated from seedlings inoculated with P. cinnamomi nor from seedlings inoculated with both pathogens in droughted soils. Neither P. cinnamomi nor Py. spiculum were isolated from uninoculated control seedlings.

4. Discussion

The present study confirms that soil moisture strongly influences the pathogenic behaviour of P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum on cork oak, with each species responding differently across the moisture gradient tested. These patterns align with previous observations regarding the contrasting ecological requirements and pathogenicity of these oomycetes in Mediterranean oak ecosystems. Many Phytophthora and some Pythium species have been associated with Mediterranean Quercus decline [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], but field outbreaks of Q. ilex or Q. suber root rot in southern Europe—and even in northern Africa—have been reported to be mainly associated with P. cinnamomi root infections [12,16,26,42,43,44,45]. In southern Spain and Portugal, Py. spiculum has also been consistently isolated from necrotic roots in declining oak woodlands [26,46], although its virulence has been described as lower than that of P. cinnamomi under controlled conditions [25,47]. The contrasting behaviour observed in our experiments under different moisture regimes is consistent with these previous findings.

Oomycete pathogens, both Phytophthora and Pythium spp., require wet soils for zoospore release and spread to the roots of host plants [20,48], whereas seasonal fluctuations between flooded soil and drought were especially favourable for P. cinnamomi epidemics [17,46]. Soil flooding is a common phenomenon in southern oak woodlands (dehesa) in Spain during rainy autumn–winter seasons, but the dry summer character of dehesa soils, in addition to their lack of nutrients and shallowness, is their most remarkable feature [49].

Comparative virulence between P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum were previously checked in potted Q. ilex and Q. suber seedlings submitted to periodic soil flooding, showing Py. spiculum to be less pathogenic than P. cinnamomi [47], as confirmed in the present work. However, Py. spiculum seemed able to compete with the highly virulent pathogen P. cinnamomi in the field, sharing Quercus hosts and being the main species isolated from symptomatic oak roots in some woodlands [46]. In this work, we observed how different soil water contents determined the preferential oak root infection by P. cinnamomi or Py. spiculum. Phytophthora cinnamomi acted like a virulent pathogen in wet soils (54% ≤ θs ≤ 100%) and even at medium water content (25% ≤ θs ≤ 36%), causing a high level of necrosis of the oak root system. As expected, this is in good agreement with previous field reports of P. cinnamomi infecting Q. ilex and Q. suber, inducing severe root damage both in waterlogged soils and when soil flooding seasonally occurs for short periods [17,30]. However, P. cinnamomi virulence was drastically reduced in drought conditions (9% ≤ θs ≤ 12%), becoming unable even to infect oak roots, as ascertained from the lack of reisolation from inoculated seedlings. Recent studies have observed that P. cinnamomi cause less infections on Q. suber and Q. ilex plants under soil moisture conditions near the wilting point [30]. This fact must be directly related to the requirement of soil moisture for sporangia development and zoospore release and spread in Phytophthora species [19,50].

In contrast with P. cinnamomi, Py. spiculum can infect cork oak roots under drought conditions, causing significant root necrosis when compared with roots from uninoculated control saplings, highly damaged by drought alone. However, Py. spiculum infections were not detected in flooded soil (θs = 100%) and were less virulent than P. cinnamomi in wet soils (θs ≥ 50%), as previously reported [25], and they were equally found for holm oaks [47]. This better adaptation of Py. spiculum to terrestrial habitats has previously been suggested, considering its inability to release infective zoospores [24], and this has been demonstrated in the current work.

When both pathogens were inoculated together, no synergistic effect was observed under any of the soil moisture conditions considered, and the mixed inoculum consistently induced the same level of root necrosis as P. cinnamomi alone. These results do not suggest direct competition or interaction between the two species; rather, they indicate that their capacity to infect roots is primarily governed by soil moisture. The capacity of P. cinnamomi to infect oak roots under a wide range of soil water contents makes it the main root pathogen for Mediterranean oaks, possibly demoting Py. spiculum to the role of a secondary root invader. In fact, Py. spiculum was reisolated, together with P. cinnamomi, from roots inoculated with both pathogens under flooding, even when Py. spiculum alone was not able to infect roots under high-water soil conditions. Nevertheless, during the dry summer season in the Mediterranean region, when soil moisture can drop to 5% [49], P. cinnamomi would be unable to infect roots, whereas Py. spiculum would be able to, adding necrosis symptoms to oak roots already highly affected by drought.

The Mediterranean Basin is considered a global climate change hotspot due to the forecasted rainfall reduction and warming and the expected increase in the occurrence of extreme climate events [6,51]. Trees growing under the increasingly long summer season in this region have evolved a wide range of morphological, physiological, and anatomical adaptations to survive the drought [8,52]. However, the present work indicates a high vulnerability to drought in cork oaks in the absence of pathogens, as previously reported for Q. ilex [53]. In contrast, cork oaks showed a low vulnerability to soil flooding, as previously reported in the field [26]. Accordingly, control seedlings maintained under saturated soil for only 4 weeks developed minimal root necrosis, whereas those subjected to low moisture were exposed to 24 weeks of drought and showed severe root damage, reflecting the cumulative effect of prolonged water deficit under pot conditions.

Overall, our results demonstrated how P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum, common in Mediterranean oak woodland soils, can infect cork oak roots, causing decline in a wide range of soil moisture, with P. cinnamomi infecting roots in wet-to-moderately dry soils, and Py. spiculum infecting roots in droughted soils. However, although reflective of root symptomatology (primary symptoms), secondary foliar symptoms were, in general, of lower magnitude than those detected at the root level due to a delay between root infection and aboveground symptom development, as frequently reported for trees with coriaceous leaves, such as evergreen oaks [54]. Despite its intentionally simple experimental design, this study provides relevant information on the interaction between P. cinnamomi and Py. spiculum in cork oak ecosystems and on how soil moisture influences disease development. Therefore, understanding the effects of global climate change drivers on the health status of trees necessitates a close look belowground, as canopy deterioration does not seem to be a good tool with which to evaluate decline driven by root pathogens.

5. Conclusions

Phytophthora cinnamomi and Py. spiculum infect oak roots across a wide range of soil moisture conditions, with P. cinnamomi infecting roots in wet-to-moderately dry soils, and Py. spiculum infecting roots in droughted soils. At present, and also under the future soil water deficit projected for the Mediterranean region, oaks growing in woodland soils infested by both pathogens are at high risk of root disease outbreaks, which seriously endanger their future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.E.S. and M.S.S.; methodology, M.G., M.E.S., and M.Á.R.; software, M.G.; validation, M.G. and M.E.S.; formal analysis, M.G. and M.E.S.; investigation, M.G., M.E.S., M.S.S., and M.Á.R.; resources, M.E.S.; data curation, M.G. and M.E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G. and M.E.S.; writing—review and editing, M.G., M.S.S., and M.E.S.; visualization, M.G., M.S.S., and M.E.S.; supervision, M.S.S. and M.E.S.; project administration, M.E.S.; funding acquisition, M.E.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by MINECO, Spain (project CGL2014-56739-R), and by the BioDehesa project (LIFE+ 11 BIO/ES/000726).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript is part of a Ph.D. thesis by the first author, available online at https://helvia.uco.es/xmlui/handle/10396/19309 accessed on 1 October 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- David, T.S.; Henriques, M.O.; Kurz-Besson, C.; Nunes, J.; Valente, F.; Vaz, M.; Pereira, J.S.; Siegwolf, R.; Chaves, M.M.; Gazarini, L.C.; et al. Water-use strategies in two co-occurring Mediterranean evergreen oaks: Surviving the summer drought. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, J.S.; Catry, F. Forest fires in cork oak (Quercus suber L.) stands in Portugal. Int. J. Environ. Stud. 2006, 63, 235–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Moreno, A.M.; Carbonero-Muñoz, M.D.; Serrano-Moral, M.; Fernández-Rebollo, P. Grazing affects shoot growth, nutrient and water status of Quercus ilex L. in Mediterranean open woodlands. For. Sci. 2014, 71, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lionello, P.; Abrantes, F.; Congedi, L.; Dulac, F.; Gacic, M.; Gomis, D.; Goodess, C.; Hoff, H.; Kutiel, H.; Luterbacher, J.; et al. Introduction: Mediterranean Climate-Background Information. In The Climate of the Mediterranean Region: From the Past to the Future; Lionello, P., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. xxxv–xc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Vide, J.; Gómez, L. Regionalization of peninsular Spain based on the length of dry spells. Int. J. Climatol. 1999, 19, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindner, M.; Maroschek, M.; Netherer, S.; Kremer, A.; Barbati, A.; García-Gonzalo, J.; Seidl, R.; Delzon, S.; Corona, P.; Kolström, M.; et al. Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC WGII. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. In Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.H.; et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Lloret, F.; Breshears, D.D. Drought-induced forest decline: Causes, scope and implications. Biol. Lett. 2012, 8, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sache, I.; Roy, A.S.; Suffert, F.; Desprez-Loustau, M.L. Invasive plant pathogens in Europe. In Biological Invasions: Economic and Environmental Costs of Alien Plant, Animal, and Microbe Species, 2nd ed.; Pimentel, D., Ed.; CRC Press: London, UK, 2011; pp. 227–242. [Google Scholar]

- Garbelotto, M.; Gonthier, P. Ecological, evolutionary, and societal impacts of invasions by emergent forest pathogens. In Forest Microbiology; Asiegbu, F.O., Kasanen, R., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2022; pp. 107–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasier, C.M. Phytophthora cinnamomi and oak decline in southern Europe. Environmental constraints including climate change. Ann. For. Sci. 1996, 53, 347–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desprez-Loustau, M.L.; Marçais, B.; Nageleisen, L.M.; Piou, D.; Vannini, A. Interactive effects of drought and pathogens in forest trees. Ann. For. Sci. 2006, 63, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T. Beech decline in Central Europe driven by the interaction between Phytophthora infections and climatic extremes. For. Path. 2009, 39, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.S.; De Vita, P.; Fernández-Rebollo, P.; Coelho, A.C.; Belbahri, L.; Sánchez, M.E. Phytophthora cinnamomi and Pythium spiculum as main agents of Quercus decline in Southern Spain and Portugal. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 2012, 76, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Brasier, C.M.; Robredo, F.; Ferraz, J.F. Evidence for Phytophthora cinnamoni involvement in Iberia oak decline. Plant Pathol. 1993, 42, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.E.; Caetano, P.; Ferraz, J.; Trapero, A. Phytophthora disease of Quercus ilex in south-western Spain. For. Pathol. 2002, 32, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbart, J.A.; Guyette, R.; Muzika, R.M. More than drought: Precipitation variance, excessive wetness, pathogens and the future of the western edge of the eastern deciduous forest. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566–567, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardham, A.R.; Blackman, L.M. Phytophthora cinnamomi. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2018, 19, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, M.W. The Peronosporomycetes. In The Mycota VII, Part A: Systematics and Evolution; McLaughlin, D.J., McLaughlin, E.G., Lemke, P.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 39–72. [Google Scholar]

- Benhamou, N.; Rey, P.; Chérif, M.; Hockenhull, J.; Tirilly, Y. Treatment with the mycoparasite Pythium oligandrum triggers induction of defense-related reactions in tomato roots when challenged with Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici. Phytopathology 1997, 87, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, G.; Jonathan, R.; Paul, B. Pythium stipitatum sp. nov. isolated from soil and plant debris taken in France, Tunisia, Turkey, and India. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 295, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, B.; Bala, K.; Belbahri, L.; Calmin, G.; Sánchez-Hernández, E.; Lefort, F. A new species of Pythium with ornamented oogonia: Morphology, taxonomy, internal transcribed spacer region of its ribosomal RNA, and its comparison with related species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 254, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vita, P.; Serrano, M.S.; Belbahri, L.; García, L.V.; Ramo, C.; Sánchez, M.E. Germination of hyphal bodies of Pythium spiculum isolated from declining cork oaks at Doñana National Park (Spain). Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2011, 50, 478–481. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, P.; Serrano, M.S.; Ramo, C.; Aponte, C.; García, L.V.; Belbahri, L.; Sánchez, M.E. First report of root rot caused by Pythium spiculum affecting cork oaks at Doñana Biological Reserve in Spain. Plant Dis. 2013, 97, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, M.A.; Sánchez, J.E.; Jiménez, J.J.; Belbahri, L.; Trapero, A.; Lefort, F.; Sánchez, M.E. New Pythium taxa causing root rot on Mediterranean Quercus species in south-west Spain and Portugal. J. Phytopathol. 2007, 155, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.S.; Ríos, P.; González, M.; Sánchez, M.E. Experimental minimum threshold for Phytophthora cinnamomi root disease expression on Quercus suber. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2015, 54, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.E.; Andicoberry, S.; Trapero, A. Pathogenicity of three Phytophthora spp. causing late seedling rot of Quercus ilex ssp. ballota. For. Pathol. 2005, 35, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, M.; Robin, C.; Capron, G.; Desprez-Loustau, M.L. Effects of root damage associated with Phytophthora cinnamomi on water relations, biomass accumulation, mineral nutrition and vulnerability to water deficit of five oak and chestnut species. For. Pathol. 2001, 31, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, A.C.; Rodrigues, A. Effect of soil water content and soil texture on Phytophthora cinnamomi infection on cork and holm oak. Silva Lusit. 2021, 29, 133–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, I.; Pardos, M.; Puértolas, J.; Jiménez, M.D.; Pardos, J.A. Water-use efficiency in cork oak (Quercus suber) is modified by the interaction of water and light availabilities. Tree Physiol. 2007, 27, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüberli, D.; Tommerup, I.C.; Hardy, G.E.S.J. False-negative isolations or absence of lesions may cause misdiagnosis of diseased plants infected with Phytophthora cinnamomi. Australas. Plant Path. 2000, 29, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Sala, B.; Abad-Campos, P.; Berbegal, M. Response of Quercus ilex seedlings to Phytophthora spp. root infection in a soil infestation test. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 154, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sierra, A.; López-García, C.; León, M.; García-Jiménez, J.; Abad-Campos, P.; Jung, T. Previously unrecorded low-temperature Phytophthora species associated with Quercus decline in a Mediterranean forest in eastern Spain. For. Path. 2013, 43, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcobado, T.; Cubera, E.; Pérez-Sierra, A.; Jung, T.; Solla, A. First report of Phytophthora gonapodyides involved in the decline of Quercus ilex in xeric conditions in Spain. New Dis. Rep. 2010, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linaldeddu, B.T.; Sirca, C.; Spano, D.; Franceschini, A. Variation of endophytic cork oak-associated fungal communities in relation to plant health and water stress. For. Path. 2010, 41, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcobado, T.; Miranda-Torres, J.J.; Martín-García, J.; Jung, T.; Solla, A. Early survival of Quercus ilex subspecies from different populations after infections and co-infections by multiple Phytophthora species. Plant. Pathol. 2016, 65, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Jung, M.H.; Cacciola, S.O.; Cech, T.; Bakonyi, J.; Seress, D.; Mosca, S.; Schena, L.; Seddaiu, S.; Pane, A.; et al. Multiple new cryptic pathogenic Phytophthora species from Fagaceae forests in Austria, Italy and Portugal. IMA Fungus 2017, 8, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, T.; Blaschke, H.; Neumann, P. Isolation, identification and pathogenicity of Phytophthora species from declining oak stands. For. Pathol. 1996, 26, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbahri, L.; McLeod, A.; Paul, B.; Calmin, G.; Moralejo, E.; Spies, C.F.; Botha, W.J.; Clemente, A.; Descals, E.; Sánchez-Hernández, E.; et al. Intraspecific and within-isolate sequence variation in the ITS rRNA gene region of Pythium mercuriale sp. nov. (Pythiaceae). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 284, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belbahri, L.; Calmin, G.; Sánchez-Hernández, E.; Oszako, T.; Lefort, F. Pythium sterilum sp. nov. isolated from Poland, Spain and France, its morphology and molecular phylogenetic position. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2006, 255, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilo-Alves, C.S.P.; Clara, M.I.E.; Ribeiro, N.M.C.A. Decline of Mediterranean oak trees and its association with Phytophthora cinnamomi: A review. Eur. J. For. Res. 2013, 132, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanu, B.; Linaldeddu, B.T.; Franceschini, A.; Anselmi, N.; Vannini, A.; Vettraino, A.M. Occurrence of Phytophthora cinnamomi in cork oak forests in Italy. For. Pathol. 2013, 43, 340–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smahi, H.; Belhoucine-Guezouli, L.; Franceschini, A.; Scanu, B. Phytophthora species associated with cork oak decline in a Mediterranean forest in western Algeria. IOBC/WPRS Bull. 2017, 127, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Frisullo, S.; Lima, G.; Magnano di San Lio, G.; Camele, I.; Melissano, L.; Puglisi, I.; Pane, A.; Agosteo, G.E.; Prudente, L.; Cacciola, S.O. Phytophthora cinnamomi involved in the decline of holm oak (Quercus ilex) stands in Southern Italy. For. Sci. 2018, 64, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcobado, T.; Cubera, E.; Moreno, G.; Solla, A. Quercus ilex forests are influenced by annual variations in water table, soil water deficit and fine root loss caused by Phytophthora cinnamomi. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 169, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, J.J.; Sánchez, J.E.; Romero, M.A.; Belbahri, L.; Trapero, A.; Lefort, F.; Sánchez, M.E. Pathogenicity of Pythium spiculum and P. sterilum on feeder roots of Quercus rotundifolia. Plant Pathol. 2008, 57, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeham, A.J.; Pettitt, T.R.; White, J.G. A novel method for detection of viable zoospores of Pythium in irrigation water. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1997, 131, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Rodríguez, V.; Villar, R.; Casado, R.; Suárez-Bonnet, A.; Quero, J.L.; Navarro-Cerrillo, R.M. Spatio-temporal heterogeneity effects on seedling growth and establishment in four Quercus species. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 1217–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erwin, D.C.; Ribeiro, O.K. Phytophthora Diseases Worldwide; APS Press: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, F.; Lionello, P. Climate change projections for the Mediterranean region. Glob. Planet. Change 2008, 63, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas, J.; Lloret, F.; Montoya, R. Severe drought effects on Mediterranean woody flora in Spain. For. Sci. 2001, 47, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcobado, T.; Cubera, E.; Juárez, E.; Moreno, G.; Solla, A. Drought events determine performance of Quercus ilex seedlings and increase their susceptibility to Phytophthora cinnamomi. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 192–193, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, C.; Capron, G.; Desprez-Loustau, M.L. Root infection by Phytophthora cinnamomi in seedlings of three oaks species. Plant Pathol. 2001, 50, 708–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.