Abstract

Forest carbon sinks (FCS)—referring specifically to ecosystem-based carbon sequestration provided by forest ecosystems—are being increasingly recognized as a strategic form of natural capital under China’s “dual carbon” goals. While the ecological value of FCS is being translated into economic benefits through carbon markets, eco-compensation, and green finance, the extent to which ecosystem carbon sinks can continuously drive regional economic growth—and how such effects differ across regions—remains insufficiently understood. Using panel data for 294 Chinese prefecture-level cities from 2010 to 2022, this study employs dynamic panel methods to examine the dynamic, nonlinear, and heterogeneous impacts of ecosystem-based FCS on economic growth. The results show that (1) FCS significantly promote economic growth but follow an inverted U-shaped pattern, indicating diminishing marginal returns; (2) notable regional heterogeneity exists, with the strongest effects in central and western regions, while eastern cities exhibit weaker responses due to structural and spatial constraints; and (3) clear threshold effects are present, suggesting that industrial upgrading, urbanization, and moderate government intervention can amplify the economic contribution of FCS. These findings clarify the mechanism through which FCS transitions from ecological assets to economic capital, providing theoretical and empirical support for sustainable forest management, ecological-industrial integration, and carbon market optimization in the pursuit of carbon neutrality.

1. Introduction

As climate risks intensify and the Paris Agreement enters full implementation, forests have become increasingly central to global climate action and sustainable development [1,2]. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report identifies terrestrial ecosystems as major global carbon sinks, with land and ocean systems together absorbing about 56% of anthropogenic CO2 emissions [3], among which forests play a dominant role and form a key component of nature-based climate solutions [4,5,6]. However, the economic returns of forest-based carbon sequestration remain theoretically underexplored and empirically ambiguous.

International research shows that forests contribute to mitigation through two primary channels. The first is biogenic carbon storage, referring to carbon captured by forest ecosystems and retained in harvested wood products over decades [7]. The second is the substitution effect, whereby timber and other bio-based materials replace carbon-intensive products such as steel, cement, and plastics, generating substantial indirect emissions reductions across value chains [8,9,10].

Yet the substitution effect operates through complex and highly context-dependent mechanisms, making its macroeconomic effects difficult to isolate empirically [11,12,13]. By contrast, carbon stored directly in forest ecosystems constitutes a clearer and more identifiable form of natural capital [14]. Improvements in forest ecological quality can enhance investment attractiveness and support forest-related industries through relatively direct and traceable economic channels, thereby influencing economic growth. For reasons of empirical clarity, this study therefore focuses exclusively on FCS derived from forest ecosystems. Carbon stored in harvested wood products, as well as emissions reductions generated through material substitution, are not included in our econometric analysis.

This context underpins China’s “dual-carbon” goals—to peak emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060—under which forests are positioned as a central pillar of national climate policy [15]. Studies estimate that China’s forests account for roughly 55 to 60 percent of the country’s total terrestrial carbon sink, making them one of the most effective and cost-efficient mitigation tools available [16]. A key institutional development is the relaunch of the China Certified Emission Reductions (CCER) voluntary carbon market in 2023. Although CCER operates as a voluntary mechanism, China’s emissions trading system allows regulated firms to use CCER credits—typically up to 5% of verified emissions—as compliance offsets [17]. This hybrid design elevates forestry projects, including afforestation, forest management, and bamboo carbon sinks, into important sources of high-quality tradable credits [18,19]. As a result, FCS are increasingly transformed from ecological assets into marketable forms of green capital.

Despite this progress, much of the existing literature still centers on ecological or mitigation functions, leaving the broader macroeconomic implications of FCS insufficiently understood [15,20]. Traditional Environmental Kuznets Curve models tend to treat natural capital as a constraint rather than a potential driver of growth, overlooking the possibility that ecological assets can generate positive economic spillovers [21]. In reality, the economic effects of FCS are likely nonlinear and highly dependent on local conditions [22,23]. Regional differences in development stages, institutional capacity, and resource-allocation efficiency mean that the growth effects of FCS may diverge substantially. While international studies have advanced methods for valuing ecosystem services [4,24], few investigate dynamic or nonlinear effects using empirical tools such as a system generalized method of moments model (System GMM) or threshold models—especially in large emerging economies.

To address these gaps, this study analyzes panel data from 294 Chinese prefecture-level cities between 2010 and 2022—a period marked by rapid industrial restructuring, stronger environmental regulation, and the gradual expansion of carbon-market institutions. By dynamic panel methods, we examine the dynamic, nonlinear, and regionally heterogeneous effects of FCS on economic growth. This approach helps resolve endogeneity and path-dependence issues while identifying how industrial upgrading, urbanization, and government intervention shape the transformation of ecological value into economic value.

This study makes three main contributions.

- (1)

- It develops a nonlinear analytical framework that explains how ecological assets—such as FCS—can be transformed into economic capital, adding new insights to the literature on forest carbon economics and green growth.

- (2)

- It offers the first systematic empirical verification and quantitative identification of the inverted-U-shaped relationship between FCS and economic growth—estimating both its magnitude and structural turning point—and thereby converts a long-standing theoretical expectation into measurable evidence.

- (3)

- It shows how institutional conditions influence the economic value of FCS, providing practical guidance for improving China’s carbon market mechanisms, advancing ecological product valuation, and designing region-specific forest management strategies.

This study is motivated by three central questions. Does FCS sequestration contribute to economic growth in a nonlinear manner over time? How do institutional capacity and development conditions influence the marginal economic effects of FCS? And do these effects vary across regions at different stages of development? Addressing these questions is essential for understanding the economic role of FCS in achieving carbon-neutrality goals.

2. Theoretical Mechanism Analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of the mechanism by which FCS influence regional economic growth, this paper adopts a dual ecological–economic perspective and develops a nonlinear, heterogeneous analytical framework, from which three core research hypotheses are derived. Table 1 summarizes the main theoretical channels through which FCS may affect economic growth. It outlines the expected effects, commonly used identification approaches, and remaining research gaps.

Table 1.

Summary of theoretical mechanisms linking FCS and economic growth.

2.1. Nonlinear Economic Effects of FCS

The economic value of FCS comes from two sources: “natural carbon sinks” and “product-based carbon sinks”. The former refers to the carbon captured and stored by forest ecosystems through photosynthesis—forming the biophysical foundation of the forest-carbon economy. The latter arises when timber, bamboo, and other bio-based materials substitute for carbon-intensive materials such as steel, cement, or plastics, thereby extending carbon-storage duration and reducing life-cycle industrial emissions [25]. Together, these mechanisms constitute the full value chain of forest resources. Among them, ecosystem carbon sequestration constitutes a more direct and traceable ecological–economic transmission pathway, while material substitution represents an indirect and complementary mechanism.

From a natural capital perspective, the carbon stock generated by forest ecosystems can be mobilized economically when supported by appropriate institutional and market arrangements. International evidence identifies FCS as one of the most efficient channels for converting natural capital into economic capital [26,27]. In China, this conversion mainly works through two mechanisms. First, afforestation and forest management projects generate additional, verifiable carbon sequestration that can be traded on the voluntary CCER market. Companies purchase these credits to offset part of their emissions, creating steady revenue for local governments and forest managers—funds that, in turn, support employment, forest operations, and ecological-infrastructure investment [28,29]. Second, FCS are built into ecological transfer payments, carbon asset pledge financing, and green bonds [30]. These arrangements create a cycle in which “ecological value is capitalized and reinvested”, giving natural capital both financing capacity and a leverage effect that helps drive the development of under-forest economies, eco-tourism, and biomass industries [31,32].

Beyond ecosystem carbon storage, forest resources also generate economic value through product-based carbon sinks. Long-living wood products—such as structural timber with service lives exceeding 50 years—store biogenic carbon and displace high-emission construction materials [33]. Empirical studies show that timber buildings can reduce life-cycle emissions by 30–40 percent relative to reinforced-concrete structures [34]. This demonstrates that forests contribute to economic development not only through direct carbon sequestration but also by supporting low-carbon manufacturing, wood-based industrial chains, and the transition toward green building systems.

More broadly, FCS serve as a critical component of natural capital, providing carbon sequestration, oxygen release, windbreak and sand fixation, and water conservation—functions essential for regional sustainable development [35,36]. Under the “dual-carbon” strategy, the ecological value of FCS is progressively converted into economic value as China’s carbon-trading system and ecological product value-realization mechanisms mature [37]. As a result, carbon sinks are increasingly priced as economic assets, enabling regions to access green finance, ecological compensation transfers, and industrial incubation resources [20], while simultaneously stimulating the expansion of green industries such as under-forest economies, eco-tourism, and biomass energy [22,38,39].

Consistent with prior theoretical arguments, the transformation of ecological assets into economic capital is expected to be nonlinear. According to the law of diminishing marginal returns, once carbon sequestration surpasses a critical threshold, incremental benefits decline and may even trigger ecological or economic backlash [40]. Excessive emphasis on carbon sink accumulation may tighten forest land controls, restrict construction land supply, and impede infrastructure expansion [41]. Large-scale afforestation or conservation may also reduce arable land, generating food security concerns. Forest-management and carbon-accounting costs tend to rise nonlinearly with carbon sink totals, narrowing the net contribution of FCS to gross domestic product (GDP) [42]. Thus, the relationship between FCS and economic growth is expected to follow an inverted-U-shaped pattern: at lower levels, FCS promote ecological restoration, green investment, and employment; at higher levels, marginal returns diminish and may hinder industrial performance and resource allocation efficiency [21,43]. Although such nonlinear dynamics are frequently discussed in the theoretical and policy-oriented literature, the underlying economic logic and boundary conditions of this inverted-U relationship remain insufficiently articulated at the urban level.

From the perspective of green economic development theory, this nonlinear mechanism also reflects the principle of ecological scale appropriateness, meaning that the utilization of ecological assets must align with the absorption and conversion capacities of the economic system. Excessive ecologicalization may be detrimental to short-term economic performance. Therefore, identifying the optimal range and nonlinear path of FCS’ impact on economic growth not only facilitates the coupled development of ecology and economy but also provides a theoretical basis for regions to formulate differentiated carbon sink policies [19]. Based on this, Hypothesis 1 is proposed:

Hypothesis 1.

There is an inverted U-shaped relationship between FCS and economic growth, and at low carbon sink levels, there is a positive promotional effect, but once a certain threshold is exceeded, the marginal effect diminishes and has an inhibitory effect.

2.2. Regional Heterogeneity and Absorptive Capacity

Regional development conditions play a key regulatory role in the resource–growth relationship and serve as an important background variable influencing the economic effects of FCS [44]. Both the new regional growth theory and sustainable development economics emphasize that the role of resources in growth depends not only on their endowment and quantity but also on a region’s capacity to absorb, transform, and institutionally embed them. Significant differences exist among regions in terms of natural ecology, economic structure, and policy implementation, leading to heterogeneity in the pathways and intensity through which FCS exert their economic effects across regions [43].

As the most economically developed region in China, the eastern region primarily relies on the tertiary sector and high-end manufacturing for its industrial structure, with capital, technology, and information serving as the dominant factors. The marginal contribution of green resources to its economic growth is relatively limited [45]. Additionally, land scarcity and compressed ecological space in eastern cities have constrained the growth of FCS, resulting in a smaller share of GDP. Furthermore, the region has already established relatively mature green institutional arrangements, such as carbon trading platforms and green credit mechanisms, so the policy dividends from carbon sinks are also stabilizing, making it difficult to continue significantly driving growth. Through carbon trading market mechanisms like the CCER mechanism, FCS have become tradable assets.

The central region is currently in a transitional phase of industrial transformation and accelerated urbanization, with green infrastructure and ecological systems still in their early stages of development [43,44]. FCS, as carriers of ecological compensation and green financing, still have a significant promotional effect on local economies. Carbon sink growth can drive forestry investment, green employment, and related services, especially in the context of carbon sink asset securitization and the gradual expansion of carbon markets. The central region has the potential to transform its ecological advantages into development advantages.

The western region is endowed with the richest forest resources and is a key national ecological function zone. Leveraging policy support from initiatives such as the “Natural Forest Conservation Program”, “Grain-for-Green Program”, and “Three-North Shelterbelt Forest Program”, the region’s carbon sink capacity has continued to grow [46,47]. However, due to the region’s weak economic foundation and underdeveloped transportation and market systems, the growth of FCS may initially significantly drive infrastructure and ecological industry development. Once carbon sink reserves reach a certain level, their marginal benefits are likely to decline rapidly. Without green technological innovation and industrial integration mechanisms, carbon sinks may struggle to sustainably convert into high-quality economic momentum [44]. Therefore, the role of FCS in economic growth exhibits different marginal effects and nonlinear structures due to regional differences, presenting a gradient characteristic of “weak in the east, strong in the central regions, and initially strong then declining in the west”. Based on this, Hypothesis 2 is proposed:

Hypothesis 2.

The impact of FCS on economic growth varies across regions, exhibiting a more pronounced inverted U-shaped structure in central and western regions, while its effect is relatively weak or insignificant in eastern regions.

2.3. Institutional Thresholds and Stage-Dependent Marginal Effects

The economic effects of FCS are not static but are significantly influenced by institutional foundations and development conditions. New structural economics and institutional economics both point out that the economic conversion capacity of natural resources depends not only on the resources themselves but also on the industrial system carrying capacity of the city, the stage of urbanization, and the government’s intervention capacity [37]. Differences in institutional environments may shape the mechanism through which FCS function within economic systems, leading to segmented, nonlinear changes in their marginal effects [48].

Industrial structure upgrading is a crucial prerequisite for FCS to realize their market value and economic transformation [44]. In regions where the industrial structure is heavily reliant on primary industries, carbon sink resources are often confined to the ecological sector, lacking integration with manufacturing and services, thereby limiting their contribution to GDP. In regions with a more balanced industrial structure and higher levels of integration among the three sectors, carbon sinks are more easily embedded into green industrial chains (such as forest-based economy, carbon asset development, and green technology services), thereby facilitating the spillover and conversion of ecological value.

The level of urbanization also largely determines the conversion channels for carbon sinks [49]. In areas with low urbanization, FCS are mostly located in remote ecological zones, lacking supporting infrastructure and human capital, resulting in high carbon sink development costs and weak economic spillover capacity. In contrast, highly urbanized areas not only have stronger market integration capabilities but are also more likely to integrate ecological assets into the urban economic system through technological platforms, financial tools, and policy mechanisms.

Government intervention is a key institutional safeguard for carbon sink development and utilization [50,51]. Moderate fiscal expenditures and policy incentives can lower the barriers to marketization of ecological resources and promote the establishment of carbon sink project standards, property rights clarification, and market transactions, thereby achieving the transformation of “green mountains and clear waters” into “golden mountains and silver mountains”. However, excessive intervention may distort market signals, suppress resource allocation efficiency, and generate negative externalities.

These considerations imply that the economic effects of FCS are likely to exhibit stage-dependent and segmented marginal returns under different institutional and developmental conditions. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 is proposed:

Hypothesis 3.

The marginal effect of FCS on economic growth exhibits segmented and nonlinear changes with respect to industrial upgrading, urbanization, and government intervention.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Model Settings

In order to comprehensively identify the impact of FCS on regional economic growth, this paper constructs the following three types of empirical models based on theoretical analysis:

- (1)

- Static Panel Fixed-Effects Model:

To examine the static relationship between FCS and economic growth, we set up the following fixed-effects regression model:

where represents the economic growth level of the city in year , represents the FCS level, captures nonlinear effects, are control variables, are city and province fixed effects and year fixed effects, respectively, and is the disturbance term. To further ensure the robustness of the static fixed-effects estimation, we conduct influence diagnostics using the DFBETA statistic to assess whether individual observations exert disproportionate effects on the estimated coefficients.

Considering that carbon sink levels () may have endogenous issues (such as mutual causality with economic growth), this paper further uses an instrumental variable fixed-effects model (IV-FE) for robust identification, in which the first-order lagged variable of the FCS variable is used as the instrumental variable, and two-stage least squares estimation (2SLS) is performed:

- Phase 1:

- Phase 2:

The Kleibergen–Paap LM, Cragg–Donald Wald F statistic, and Stock–Yogo critical value are used to determine whether the instrument variable has a weak identification problem. Within the instrumental-variable fixed-effects framework, we further apply the Durbin–Wu–Hausman test to formally examine the endogeneity of the FCS variable and justify the use of the instrument variable approach.

- (2)

- Dynamic System Generalized Method of Moments Model:

To identify the possible dynamic dependence and bidirectional causal mechanisms between FCS and economic growth, we further constructed a dynamic panel System GMM model with the following form:

The model simultaneously utilizes horizontal equations and difference equations, employing lagged variables as instrumental variables for endogenous explanatory variables to effectively control endogeneity and dynamic error structures. During the estimation process, two-way robust standard errors and Windmeijer corrections are used, and the validity of the model and the rationality of over-identification constraints are verified through AR (2) and Sargan/Hansen tests.

Compared with difference GMM, System GMM is more appropriate in this study because FCS and economic growth exhibit strong temporal persistence. Difference GMM may therefore suffer from weak instruments when lagged levels are used. By combining equations in differences and levels, System GMM improves estimation efficiency and reduces small-sample bias in persistent panel data settings [52,53,54]. Given the city-level panel structure and the dynamic nature of the ecological–economic relationship, System GMM provides a more reliable framework for identifying the long-run nonlinear effects of FCS.

- (3)

- Panel Threshold Model:

Considering that the mechanisms underlying the role of FCS may exhibit heterogeneity and nonlinear segmented effects under different regional development conditions, this study introduces the fixed-effects panel threshold model proposed by Hansen (1999) [55] to examine the marginal effect of FCS on economic growth under different threshold conditions, such as industrial structure upgrading, urbanization levels, and government intervention, from the perspective of institutional and development conditions. This study explores the trend of carbon sink effects within different threshold variable segments. The basic model form is as follows:

Among them, represents threshold variables (including urbanization rate, level of government intervention, and industrial structure), denotes interval indicator functions, and represents the estimated threshold values. The model allows for segmented changes in carbon sink effects across different intervals and uses the bootstrap method to perform F-tests on the significance of threshold effects.

3.2. Variables Selection

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

This study uses the logarithm of actual GDP (lnGDP) at the city level as the dependent variable to measure regional economic growth levels. Real GDP is measured in constant prices, eliminating inflationary factors and better reflecting the true trends in urban economic development. Logarithmic transformation not only reduces the influence of extreme values but also makes the regression results more linear, facilitating parameter estimation and marginal effect interpretation. This variable serves as the core dependent variable in both the System GMM model and threshold regression model in this paper.

3.2.2. Core Independent Variable

The central independent variable in this study is FCS, measured as the natural logarithm of carbon sequestration capacity per unit of urban forest area (lnCT). This measure captures how effectively a city’s forest ecosystems absorb and store atmospheric CO2, making it a key indicator of natural capital accumulation [35]. In this study, the measure of FCS is confined to ecosystem-based sequestration and excludes emission reductions from material substitution, such as the use of wood products in place of carbon-intensive materials. This restriction allows the analysis to focus on the direct ecosystem-service channel through which FCS affect economic growth and reduce potential identification bias arising from heterogeneous mechanisms.

Because the economic impact of FCS is unlikely to follow a straight line, we also include a squared term (lnCT2), to detect shifts in marginal effects and to test whether the relationship takes an inverted-U or U-shaped form [21].

Detailed procedures for constructing the FCS variable are provided in Appendix A.

3.2.3. Threshold Variable

To explore the heterogeneous characteristics of FCS on economic growth, this paper introduces three types of threshold variables, each reflecting structural differences in regional development conditions.

- (1)

- Urbanization rate (Urban) [56,57] measures the concentration of urban populations and the level of infrastructure development, typically expressed as the proportion of urban residents in the total population, and serves as an important indicator for assessing the stage of urban development.

- (2)

- The degree of government intervention (Gov) [58], measured by the proportion of government fiscal expenditure relative to GDP, reflects the strength of the government’s role in resource allocation and economic regulation.

- (3)

- The level of industrial structure upgrading (Isu) [59] describes the modernization process of a city’s economic structure, often using the proportion of the secondary and tertiary industries in GDP as an indicator, with higher values indicating a more rational industrial structure.

3.2.4. Control Variables

To reduce omitted variable bias, this paper introduces two key control variables. The first is the level of technological investment (Tec) [60], represented by the ratio of R&D expenditure to GDP, which reflects a city’s technological innovation capacity and potential for improving production efficiency and is an important driver of green economic growth. The second is the level of human capital (Edu) [61], which can be measured by the proportion of students enrolled in higher education or the ratio of education expenditure to GDP, reflects the quality of the labor force and the accumulation of knowledge, and plays a crucial role in improving the efficiency of carbon sink resource utilization and promoting green industrial development. These variables help enhance the explanatory power of the model and control the interference of non-carbon sink factors on economic growth.

3.3. Data Sources and Processing

The panel dataset used in this study covers 294 prefecture-level-and-above cities across China from 2010 to 2022. Key economic indicators—including GDP per capita (as a measure of economic growth), R&D expenditure, human capital, urbanization rates, and industrial structure—are sourced from the “China Urban Statistical Yearbook” and the Wind database (https://www.wind.com.cn, accessed on 20 May 2025), both of which provide standardized and comprehensive city-level information on macroeconomic conditions and social development.

Data on FCS are estimated based on forest resource inventories and biomass conversion methods, drawing on data from national forestry statistics and the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn, accessed on 10 May 2025) [35]. These datasets combine field-plot measurements, remote sensing inversion, and machine learning biomass models, ensuring broad spatial coverage and consistent time-series estimates. To match the data with city-level administrative units, the 1 km carbon sink raster layers were spatially aggregated using official boundary shapefiles from the Resource and Environment Science Data Center (RESDC). For cities that experienced administrative boundary adjustments during the sample period, all data were harmonized to the 2020 boundary standard to maintain comparability over time.

For data quality assurance, all continuous variables were transformed using natural logarithms, and extreme observations were winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Missing data were checked across years, and observations with persistent gaps were removed. After cleaning and validation, a balanced panel dataset was assembled, capturing FCS, socio-economic indicators, and environmental characteristics over a 13-year window.

To account for unobserved heterogeneity and macro-level shocks, all models include city fixed effects and year fixed effects. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 18.0, ensuring robust estimation and reproducibility.

DeepL Translator (https://www.deepl.com/en/translator, accessed on 10 September 2025) was used solely for linguistic refinement; it did not affect the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. FCS Evolution

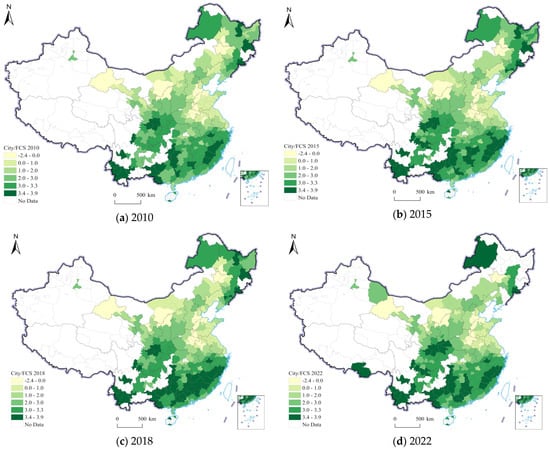

To examine the spatiotemporal evolution of FCS across Chinese cities, this study utilized ArcGIS 10.8 software to visualize the FCS levels of 294 prefecture-level-and-above cities. The specific years chosen for observation were 2010, 2015, 2018, and 2022; Figure 1a–d details this visualization.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution and temporal evolution of FCS. Prefecture-level cities are shown for each year: 2010 (a), 2015 (b), 2018 (c), and 2022 (d). Green color gradients represent intensity, darker green being a higher level of sink (Note: This map is based on the standard map with the review number GS (2024)0650 from the Standard Map Service of the Ministry of Natural Resources of China).

The results indicate a clear spatial distribution of FCS exhibiting both significant regional heterogeneity and a near-constant upward trend over time. High-carbon-sink-intensity areas were primarily concentrated in the southwestern and certain northeastern regions in 2010; northern and more inland provinces held relatively low values. A marked increase in near-universal “carbon sink” capacity was observed by 2022, with southern and central China being the prime examples. Large-scale ecological restoration projects—the Returning Farmland to Forest being one, along with more recently implemented national-level initiatives—are responsible for at least partially achieving these positive outcomes.

The overall spatial pattern of FCS follows a defined south-to-north gradient; continuous expansion (in all but the most remote areas) is what the previous paragraph describes. Ecological restoration and, to a point, carbon neutrality policies have and are still enhancing regional sequestration capabilities.

4.2. Descriptive Statistics

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the basic characteristics of the sample variables, this paper conducted descriptive statistical analysis on the main variables, with the results shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

From the perspective of the dependent variable, the log mean of urban actual GDP is 16.584, with a standard deviation of 0.936, indicating that there are significant differences in economic development levels among the sample cities, with the maximum and minimum values differing by nearly 4.5 log units. Regarding the core explanatory variables, the logarithmic mean of FCS levels is 2.122, with a maximum value of 3.964 and a minimum value of −2.410, showing a significant negative skewness (skewness of −0.996), indicating that some cities have relatively low forest carbon storage levels, resulting in a longer left tail in the data distribution. The mean of the squared term () is 6.090, with low kurtosis, indicating that carbon sink levels exhibit a certain degree of dispersion. Among the three threshold variables, the mean of urbanization rate (Urban) is 0.550, with a standard deviation of 0.149, indicating differences in the development stages of various cities; The mean of government intervention level (Gov) is 0.201, with a maximum value as high as 0.6 and a kurtosis of 7.353, indicating that some cities have a relatively high proportion of fiscal expenditures. The mean value of industrial structure upgrading level (Isu) is 1.027, with a skewness of 2.038 and a kurtosis of 8.461, indicating a strongly right-skewed distribution. This suggests that most cities remain in the early stages of industrialization dominated by the secondary sector, with only a few cities achieving a higher degree of industrial structure optimization.

4.3. Benchmark Regression Results

This section examines the impact of FCS on regional economic growth. To address potential endogeneity and dynamic adjustment, the empirical analysis proceeds in three steps. We first estimate a static fixed-effects model. We then apply an instrumental-variable fixed-effects specification. Finally, the System GMM dynamic model is employed to identify long-run effects.

4.3.1. Static Fixed-Effects Regression Analysis

Table 3 reports the results from the static fixed-effects estimations. Columns (1) and (2) present consistent coefficient patterns across specifications. After controlling for city, province, and year fixed effects, the linear term of FCS is significantly negative. The squared term is significantly positive. These findings indicate a statistically robust nonlinear relationship between FCS and regional economic growth.

Table 3.

Baseline static fixed-effects estimates of FCS and economic growth.

The estimated coefficients also carry clear economic meaning. In the baseline specification with controls (column (2)), the coefficient of lnCT equals −0.105 and is significant at the 1% level. The coefficient on lnCT2 equals 0.044 and is also significant at the 1% level. Holding other factors constant, an increase in FCS initially suppresses economic growth. As carbon sinks continue to accumulate, this negative effect gradually weakens. As carbon sinks continue to accumulate, the initially negative marginal effect gradually weakens and may eventually change sign. This nonlinear pattern reflects stage-dependent economic mechanisms. In the early phase, forest conservation and carbon sink construction impose land-use constraints. Industrial entry restrictions also emerge. The opportunity cost of forest land increases. Together, these factors crowd out short-term economic activity. At this stage, carbon sink expansion mainly represents ecological investment. Stable economic returns have not yet materialized.

As institutional conditions improve, the mechanism evolves. Carbon trading systems expand. Ecological compensation schemes become more effective. Green industrial chains begin to scale up. Under these conditions, ecological value is gradually converted into economic value. The growth-enhancing role of FCS becomes increasingly visible. Evidence from local practice supports this interpretation. In Sanming, Fujian Province, forest tenure reform and carbon sink integration extended the forestry value chain. Related industries, including herbal medicine and ecotourism, expanded rapidly. Forestry output value increased by more than 240%. In the Greater Khingan Range of Inner Mongolia, pilot programs for carbon sinks improved green investment conditions. Central state-owned enterprises invested approximately 15 billion yuan in zero-carbon industrial parks. Carbon quota incentives and policy support further reducing firms’ compliance costs.

These results should be interpreted with caution. Static fixed-effects models do not explicitly capture dynamic adjustment in economic growth. Path dependence may therefore be overlooked. Reverse causality also remains plausible. Economically stronger regions often possess greater fiscal and governance capacity. Such regions are more likely to invest in forest protection and carbon sink construction. Accordingly, the static estimates are best viewed as baseline correlations rather than long-term causal effects.

Robustness checks address the influence of extreme observations. Influence diagnostics based on the DFBETA statistic are conducted within the static fixed-effects framework. Following the conventional cutoff , influential observations account for less than 6% of the sample. After excluding these observations and re-estimating the model, the main coefficient signs and significance levels remain unchanged. The baseline results are therefore not driven by a small number of influential data points (see Appendix B).

FCS exhibit strong persistence and slow ecological adjustment. Ignoring this feature may introduce dynamic specification bias. The linear coefficient may be systematically underestimated. Such bias can mechanically generate upward curvature in static models. This concern motivates the use of endogeneity correction and dynamic specifications in subsequent analyses.

4.3.2. Instrumental-Variable Fixed-Effects Regression: Endogeneity Tests and Directional Correction

To further assess endogeneity, Table 4 reports the instrumental-variable fixed-effects estimates. Columns (1) and (2) implement lnCT and lnCT2 using their first-order lagged values. This strategy helps mitigate reverse causality from contemporaneous economic growth to carbon sink construction. It also reduces bias caused by omitted variables.

Table 4.

Instrumental variable fixed-effects results with endogeneity tests.

Identification tests support the validity of the instruments. Panel A reports Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistics of 14.810 and 14.620. Both statistics reject the null hypothesis of under-identification at the 1% level. The Cragg–Donald Wald F statistics equal 7.253 and 7.159. Both exceed the Stock–Yogo critical value of 7.03 at the 10% significance level. The Kleibergen–Paap rk Wald F statistics reach 17.293 and 17.113. These results indicate that weak instrument concerns are limited.

Panel B reports the Durbin–Wu–Hausman (DWH) test results. The F statistics equal 4.55 (p = 0.011) and 4.35 (p = 0.014). The null hypothesis of exogeneity is rejected. This confirms the presence of endogeneity in the static fixed-effects model. The use of instrumental variables is therefore statistically justified.

After correcting for endogeneity, the nonlinear pattern persists but becomes unstable. The squared term of FCS remains positive and significant at the 1% level. The linear term is negative but statistically insignificant. These results suggest that static specifications remain insufficient once endogeneity is addressed.

Importantly, this finding does not imply that the U-shaped relationship reflects a long-run causal effect. Instead, it highlights the limitations of static models without dynamic structure. Such models struggle to capture long-term adjustment paths and stage-dependent evolution.

Accordingly, the instrumental-variable fixed-effects model serves a diagnostic role in this study. It identifies and confirms endogeneity in static regressions. It also provides a necessary foundation for subsequent dynamic analysis. It does not replace dynamic models in identifying long-run mechanisms.

4.3.3. Dynamic Effects Identified by the System GMM Model

Table 5 reports the estimation results from the System GMM model. By explicitly incorporating the lagged dependent variable L.lnGDP, this framework controls for growth persistence while addressing potential endogeneity and unobserved heterogeneity. It therefore allows identification of the dynamic and nonlinear effects of FCS on economic growth.

Table 5.

System GMM estimates of the dynamic effects of FCS on economic growth.

In the nationwide sample shown in column (1), the coefficient on L.lnGDP equals 0.925 (t = 10.46), statistically significant at the 1% level. This result indicates strong growth persistence and path dependence in regional economic development, which provides a clear justification for adopting a dynamic modeling framework.

Turning to the core variables, the linear term of FCS (L.lnCT) is positive and statistically significant in column (1) (0.236, t = 2.00, significant at the 5% level). In contrast, the quadratic term (L.lnCT2) is negative and marginally significant in column (1) (−0.064, t = −1.66, significant at the 10% level). The consistent combination of a positive linear term and a negative squared term across specifications provides consistent directional evidence of a stage-dependent effect in the dynamic setting, with marginal effects gradually declining as carbon sink levels increase.

From an economic perspective, these results should not be interpreted as identifying a precise carbon sink threshold. Rather, they indicate a directional change in marginal effects over the course of long-term adjustment. At relatively low to moderate levels of FCS, further expansion may promote economic growth through channels such as ecological restoration, green industrial development, and improvements in environmental quality. As carbon sinks continue to accumulate, marginal returns gradually diminish, while rising ecological protection costs and tighter constraints on land and factor allocation may weaken their growth-enhancing role. The inverted U-shaped pattern identified here thus reflects a dynamic marginal adjustment process rather than a short-run or precisely defined policy cutoff.

Substantial regional heterogeneity is observed in the System GMM estimates. In the eastern region, as shown in column (2), neither the linear nor the quadratic term of FCS is statistically significant. This suggests that, within highly industrialized and service-oriented economic structures, FCS have not yet generated a clearly identifiable dynamic effect on economic growth. Strong land-use constraints and the limited marginal contribution of ecological assets may help explain this result.

In the central region, column (3) shows a positive and statistically significant linear effect of FCS (0.103, t = 1.64), while the quadratic term remains insignificant. This pattern indicates that, at the current development stage, FCS in the central region continue to play a growth-promoting role and have not yet entered a phase of diminishing marginal returns. This finding is consistent with the region’s relatively abundant forest resources and its transitional position in the process of green development.

By contrast, the results for the western region exhibit a more pronounced stage-dependent signal. Although overall statistical significance is relatively weak, the quadratic term in column (4) is negative and marginally significant at the 10% level (−0.064, t = −1.67), while the linear term remains positive. This combination suggests that, in some western areas, the marginal growth-enhancing effect of FCS may be weakening and gradually approaching a diminishing-returns phase. This pattern is consistent with the recent large-scale expansion of ecological restoration programs and the rapid development of carbon sink trading pilots in western China, though it does not imply that a fixed threshold has already been crossed.

With respect to model validity, the System GMM diagnostic tests support the reliability of the estimates. The Arellano–Bond tests indicate significant first-order serial correlation in differenced residuals, while no evidence of second-order serial correlation is detected, as the AR (2) p-values remain above conventional significance levels across specifications. The Hansen and Sargan over-identification tests are generally within acceptable ranges, suggesting that the instrument sets are statistically valid. To mitigate instrument proliferation, the instrument set is restricted through lag-depth limitation and instrument collapsing, which helps maintain a reasonable instrument-to-sample ratio. Although some regional specifications exhibit fluctuations in the Hansen test results, the nationwide estimates and most regional models display consistent coefficient directions and economic interpretations.

To further address potential concerns regarding instrument proliferation and diagnostic sensitivity in System GMM estimation, we conducted additional robustness checks by restricting lag depth, collapsing instruments, and comparing alternative estimator specifications. The main conclusions remain qualitatively unchanged, and detailed results are reported in Appendix C, Table A3.

The System GMM results demonstrate that the impact of FCS on economic growth is inherently dynamic, nonlinear, and region-specific. The key implication is that the growth effect of ecological capital does not expand linearly with scale but instead unfolds through a long-term adjustment process in which marginal effects gradually weaken at higher levels of accumulation. These results are in line with the static fixed-effects and instrumental-variable results, but the dynamic framework gives us more reliable evidence for understanding the long-term economic effects of FCS.

It should be noted that the statistical significance of the quadratic term is marginal in some specifications, which is not uncommon in dynamic panel settings involving highly persistent variables and long adjustment horizons. Accordingly, the System GMM results are interpreted as indicating a directional and gradual change in marginal effects rather than a sharply defined threshold. We prioritize model specifications with more reliable diagnostic performance over those with stronger statistical significance but unstable instrument validity.

To assess the economic magnitude of the nonlinear effects, as shown in Table 6, we compute the implied change in lnGDP associated with a one-standard-deviation increase in lnCT, taking into account both the linear and quadratic terms. For the nationwide sample, a one-standard-deviation increase in lnCT (SD = 1.263) is associated with an increase of approximately 0.196 in lnGDP, indicating a sizeable but not excessive growth effect. In the western region, the corresponding effect is smaller (around 0.099), consistent with emerging diminishing returns. For the eastern and central regions, effect sizes are not reported due to the absence of an interior turning point or imprecisely estimated quadratic terms.

Table 6.

Turning points and marginal effects of FCS on economic growth.

4.4. Robustness Testing

Given that the System GMM estimator explicitly addresses both endogeneity and dynamic persistence, the robustness analysis in this study focuses on alternative sample definitions and time windows rather than introducing additional estimators with different identification targets. This strategy ensures methodological consistency while avoiding over-specification.

Given the geographical nature of FCS, spatial correlation across neighboring cities may arise. As a robustness check, we therefore estimate a spatial Durbin model using a balanced subsample. The results are presented in Appendix D.

4.4.1. Exclusion of Municipalities

To further test the robustness of the System GMM regression results, this paper removed the four municipalities (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and Chongqing) from the original regional division and re-estimated the System GMM. The results are shown in Table 7.

Table 7.

Robustness test—excluding municipalities.

From the national sample (column (1)), the coefficient of the first-order term for FCS is 0.217, and the coefficient of the second-order term is −0.059. Although these coefficients did not pass the significance test, their direction still supports an inverted U-shaped relationship structure. This indicates that, after controlling for municipalities, FCS still exhibit a trend of first promoting and then inhibiting economic growth, thereby validating the robustness of the benchmark results.

From a regional perspective, the coefficient of the carbon sink variable in the eastern region (column (2)) is no longer significant, indicating that after excluding economically highly developed cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, the impact of carbon sinks has weakened to some extent, possibly due to differences in ecological pressure within the region and a decline in policy response capacity.

In the central region (column (3)), while the coefficients of the first and second terms are directionally correct, they are not significant overall, possibly due to reduced sample size leading to decreased estimation precision.

Notably, the western region (column (4)) still exhibits a clear inverted U-shaped structure, with the first-order term of carbon sinks at 0.160 and the second-order term at −0.064, with the latter being significant at the 10% level. This suggests that in the western region, which has stronger resource endowments and more sensitive ecological policies, the economic growth effects of FCS are more pronounced.

All regression results passed the AR (2) test and the Sargan/Hansen over-identification test, indicating that the instrumental variable specification is reasonable, and the System GMM estimation possesses strong identification and endogeneity control capabilities. The above results are consistent with the conclusions from the GMM model estimation in the benchmark regression analysis and have passed robustness tests.

4.4.2. Shortening the Sample Years

To eliminate the disturbance caused by the epidemic on urban economic growth, this paper further limits the sample period to 2011–2019 and conducts System GMM regression for the whole country and each region separately. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Robustness test—excluding pandemic years.

From the national sample, FCS exhibit diminishing marginal returns: the coefficient of the first term is positive (0.340), while the coefficient of the second term is negative (−0.103), with the latter being significant at the 10% significance level. This indicates that during non-pandemic years, FCS have a certain positive effect on economic growth, but there is a critical point beyond which the effect becomes counterproductive.

From the regression results of various regions, the FC in the western region still exhibits an inverted U-shaped characteristic, with the first-order term (0.059) being positive and the second-order term (−0.037) being significant at the 10% significance level, consistent with the results of the baseline regression. This further confirms that the western region exhibits the clearest nonlinear relationship between FCS and economic growth, implying the existence of an optimal range for carbon sink development. On one hand, the western region is endowed with abundant forest resources and a solid ecological engineering foundation, and promoting the development of the carbon sink industry can yield dual benefits for both ecology and the economy. On the other hand, overly pursuing carbon sink targets may crowd out construction land and hinder infrastructure expansion, increase forest management costs, and even generate ecological–economic trade-offs such as reduced agricultural land or misallocation of resources, thereby pushing the region toward the diminishing-returns zone.

The carbon sink coefficients for the eastern and central regions are not significant and no longer exhibit an inverted U-shaped pattern, indicating that after excluding pandemic years, the marginal effect of FCS on economic growth in the central and eastern regions is not significant. This may be attributed to the following: first, these regions are dominated by industries and services, with low carbon sink contributions to GDP and limited industrial linkage; second, carbon sink development operates mainly as an ecological responsibility rather than a growth-oriented industry, making it difficult to convert into economic momentum in the short term.

4.5. Threshold Regression

4.5.1. Threshold Value Verification

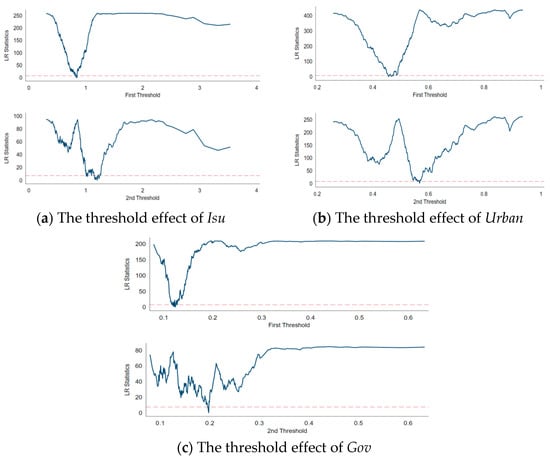

To further examine whether the impact of FCS on economic growth exhibits nonlinear characteristics, this study introduces a threshold panel regression model, using industrial structure (Isu), urbanization rate (Urban), and government intervention level (Gov) as threshold variables, to conduct significance tests on the number of thresholds.

Table 9 presents the test results for the single-, double-, and triple-threshold effects of the three types of threshold variables, including residual sum of squares (RSS), mean squared error (MSE), F statistic, and their critical values and significance levels calculated using the bootstrap method.

Table 9.

Threshold existence test.

As can be seen from the Table, the F-values for the single-threshold and double-threshold models of industrial structure are 397.67 and 86.77, respectively, both significantly higher than the corresponding critical values, with a significance level of 0.000. This indicates that the industrial structure variable exhibits a significant double-threshold effect. The F-value for the triple threshold is 49.07, which is far below the 10% critical value of 78.968, failing to pass the significance test, thus not supporting the triple-threshold structure. When urbanization rate is used as a threshold variable, the F-values for the single-threshold and double-threshold models are 500.01 and 259.97, respectively, both far exceeding the corresponding critical and statistically significant values (p = 0.000), indicating that urbanization rate also exhibits a clear double-threshold effect. However, the F-value for the triple threshold is 121.84, which is below the 10% critical value of 164.621, indicating that the triple threshold does not hold. Similarly, the F-values for the single and double thresholds of the government intervention variable are 192.98 and 77.53, respectively, both exceeding the critical value, and the significance level is 0.000, indicating that the double-threshold structure is significantly present. The F-value for the triple threshold is 49.59, with a significance level as high as 0.610, which is not statistically significant. All three types of variables exhibit the most significant double-threshold effect, while the triple threshold is not supported.

Therefore, the subsequent empirical analysis in this paper will be based on the double-threshold structure to explore the differences in the marginal effects of FCS on economic growth under different development conditions.

4.5.2. Threshold Effect Test

Based on the confirmation of the significant existence of threshold effects, the specific threshold values and their 95% confidence intervals for each threshold variable were further estimated, with the results shown in Table 10. All three types of threshold variables exhibit a dual threshold structure, indicating that the impact of FCS on economic growth is not linearly monotonic but rather exhibits segmented marginal change effects at different stages of development. Specifically,

- (1)

- The two threshold values for Isu are 0.8466 and 1.2015, with confidence intervals of [0.8404, 0.8484] and [1.1727, 1.2052], respectively. Both intervals are very narrow, indicating high precision and stability in the estimation of the threshold values. This indicates that the marginal effect of FCS on economic growth changes in stages as the level of industrial structure improves. For example, carbon sink tea garden products in Bijie, Guizhou, command a premium of 15%–20% and have obtained an exemption from the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) certification, resulting in significant brand value enhancement for the region.

- (2)

- The two threshold values for Urban are 0.4510 and 0.5631, with 95% confidence intervals of [0.4494, 0.4520] and [0.5610, 0.5649], respectively. Cities at different stages of urbanization may face distinct land-use structures, population densities, and infrastructure levels in carbon sink development, leading to changes in the mechanisms linking carbon sinks and growth. For example, during the transformation of state-owned forest areas in northeast China, carbon sink management training increased re-employment rates to 82%, enhancing human capital and reducing transformation costs.

- (3)

- The two threshold values for the degree of Gov are 0.1197 and 0.1938, with confidence intervals of [0.1180, 0.1203] and [0.1919, 0.1947], respectively, both of which are highly significant. This indicates that when government expenditure ratios are at different levels, differences in policy orientation and resource allocation efficiency moderate the direction and intensity of FCS’ impact on economic growth. For example, Ganzhou, Jiangxi Province, issued 1 billion yuan in green bonds using expected carbon sink revenues, leveraging seven times the amount of social capital into ecological infrastructure, demonstrating the multiplier effect of green finance. In the national key ecological function zone transfer payments, Yunnan receives over 7 billion yuan in fiscal transfer payments annually, with 30% linked to carbon sink performance.

Table 10.

Threshold estimate and confidence interval.

Table 10.

Threshold estimate and confidence interval.

| Threshold Variables | Threshold Value | Estimated Value | Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isu | Double-threshold | 0.8466; 1.2015 | [0.8404, 0.8484] |

| [1.1727, 1.2052] | |||

| Urban | Double-threshold | 0.4510; 0.5631 | [0.4494, 0.4520] |

| [0.5610, 0.5649] | |||

| Gov | Double-threshold | 0.1197; 0.1938 | [0.1180, 0.1203] |

| [0.1919, 0.1947] |

4.5.3. Threshold Estimation Results

After identifying significant double threshold effects for all three threshold variables, a fixed-effects threshold regression model was further used to estimate the nonlinear relationship between FCS (lnCT) and economic growth (lnGDP) in segments, with the results shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Threshold regression results.

- (1)

- Industrial structure as a threshold variable

The threshold values for industrial structure (Isu) as a threshold variable are 0.8466 and 1.2015, corresponding to the division of the sample into three stages of development. In column (1), the threshold regression results show that as the complexity of industrial structure increases, the marginal impact of FCS on economic growth gradually strengthens, with the coefficient rising from 0.144 to 0.340 and remaining significantly positive across all intervals. This indicates that in regions with a simpler industrial structure, FCS have a positive effect, but it is relatively weak; conversely, in regions with a more advanced industrial structure, the coupling effect between carbon sinks and modern services, green manufacturing, and other industries is stronger, and their promotional effect on economic growth is more pronounced.

- (2)

- Urbanization rate as a threshold variable

Using urbanization rate (Urban) as the threshold variable, the two threshold values are 0.4510 and 0.5631. In the regression results column (2), FCS have no significant impact on economic growth at the low urbanization stage (≤0.4510), with a coefficient of only 0.003 and a t-value of 0.08, indicating that the regional ecological foundation is weak at this stage, and carbon sink resources have not been effectively integrated into the economic system. However, in the medium (0.4510–0.5631) and high urbanization stages (>0.5631), its role gradually strengthens, with marginal effects of 0.239 and 0.357, respectively, both reaching the 1% significance level. This result highlights the importance of urban infrastructure.

- (3)

- The degree of government intervention as a threshold variable

Using the degree of government intervention (Gov) as a threshold variable, the two threshold values are 0.1197 and 0.1938. The threshold regression results column (3) indicates that FCS already exhibit strong economic effects at the low government intervention stage (coefficient = 0.286, t = 6.90). At the medium and high intervention stages, the marginal effects continue to strengthen, reaching 0.359 and 0.426, respectively, with higher significance levels. This suggests that moderate government involvement helps establish incentive mechanisms for carbon sink projects, improve the carbon market trading system, and enhance the economic value of FCS through fiscal support and policy guidance.

Figure 2a–c further illustrates the threshold effects of FCS on regional economic growth under different institutional and structural conditions, showing distinct nonlinear patterns across industrial structure upgrading, urbanization level, and government intervention.

Figure 2.

Threshold effects of FCS under different institutional and structural conditions: (a) industrial structure upgrading (Isu); (b) urbanization level (Urban); (c) government intervention (Gov).

In summary, the threshold regression results further validate that FCS have a typical segmented progressive positive effect on economic growth. Different regional conditions have a significant moderating effect on the strength of the carbon sink effect. This outcome provides strong evidence in support of Hypothesis 3. In terms of policy, emphasis should be placed on enhancing regional structural capacity building to unleash the growth potential of ecological assets and achieve coordinated economic and ecological development.

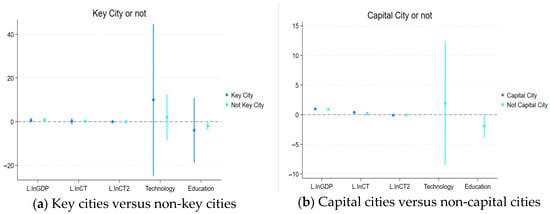

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

To further examine whether the nonlinear impact of FCS on economic growth exhibits urban hierarchy heterogeneity, this study uses grouping criteria that denotes whether a city is a central city (national or regional central city) [62] and whether it is a provincial capital city and conducts separate System GMM estimations. The results are shown in Table 12, and the corresponding forest plots are illustrated in Figure 3. Figure 3a compares key cities and non-key cities, while panel Figure 3b compares provincial capital and non-capital cities, providing a visual depiction of the estimated coefficients and confidence intervals for each subgroup.

Table 12.

Analysis of the heterogeneity effects of urban hierarchy.

Figure 3.

Forest plot for heterogeneity analysis. (a) Key cities versus non-key cities. (b) Capital cities versus non-capital cities.

4.6.1. Key Cities and Non-Key Cities

In the sample of key cities (column (1)), the coefficients of FCS and their quadratic terms (L.lnCT, L.lnCT2) for economic growth were not significant, indicating that they have not yet exhibited a clear impact pathway in such cities. This may be because key cities rely more on capital-intensive growth drivers such as technology, finance, and high-end services, thereby weakening the marginal contribution of forest resources.

In non-key cities (column (2)), although the carbon sink variables did not reach significance levels, their quadratic term coefficient was 1.198 (t = 0.92), showing a stronger positive trend. This suggests that in regions where resource endowments are more reliant on natural ecosystems, FCS may have the potential for a nonlinear enhancing effect on economic growth.

4.6.2. Provincial Capital Cities and Provincial Non-Capital Cities

For provincial capital cities (column (3)), the L.lnCT coefficient is 0.211 (positive), and L.lnCT2 is −0.316. The two coefficients form an inverted U-shaped structure, although they do not reach statistical significance. However, based on the coefficient structure, FCS may have a potential pathway of initially promoting and then inhibiting economic growth. This may reflect that in provincial capital cities, the initial utilization of forest resources has a stimulating effect on the economy, but once a certain threshold is exceeded, ecological protection pressures, land resource constraints, and increased ecological liabilities may lead to diminishing marginal benefits.

In non-provincial capital cities (column (4)), the first-order term for carbon sinks is 0.023, and the second-order term is −0.188 (t = −1.56), exhibiting a more significant inverted U-shaped characteristic. This may indicate that in general prefecture-level cities, the economic benefits of carbon sinks are in a more sensitive regulatory range, and their promotional effect on the regional economy depends on a reasonable balance point and institutional design.

The economic effects of FCS exhibit a certain degree of heterogeneity across cities of different tiers. As visualized in Figure 3a,b, carbon sink functions are more easily realized in non-key cities and non-provincial capital cities, with mechanisms potentially stemming from these cities’ higher reliance on ecological resources, stronger pressure for green industrial development, and a robust foundation of dual ecological and economic incentives.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study suggest an inverted U-shaped relationship between FCS and economic growth, which is broadly consistent with the law of diminishing marginal returns and earlier theoretical propositions [21]. This result resonates with international studies suggesting that ecosystem services initially contribute to economic development but may eventually face constraints due to rising costs and resource competition [19,41]. This pattern also reflects the dual economic pathways of FCS: while ecological carbon storage enhances environmental quality and stimulates green investment in the early stage, excessive expansion may trigger land-use tensions or rising management costs, thereby weakening net economic benefits. It should be noted, however, that the statistical strength of this nonlinear pattern varies across regions and model specifications, indicating that the inverted U-shape should be interpreted as a conditional tendency rather than a universal law.

The regional heterogeneity observed—with relatively stronger effects in central and western China and weaker effects in eastern regions—echoes findings from other developing contexts where resource-dependent regions show higher sensitivity to ecological investments [56,58]. This suggests that the economic returns of FCS are contingent upon regional development stages and industrial structures, a point also emphasized in studies on natural capital in Latin American and African contexts [58]. Central and western regions tend to rely more heavily on ecological assets and forestry-driven industries, whereas eastern cities—with more mature industrial structures—exhibit weaker marginal gains from carbon sinks. These patterns are observed within the specific institutional and development context of Chinese cities, and their magnitude may depend on local fiscal capacity, land-use regulations, and stages of industrialization.

The threshold effects associated with industrial structure, urbanization, and government intervention suggest that institutional and structural conditions may mediate the economic impacts of FCS. This aligns with Hansen’s (1999) [55] threshold model applications in environmental economics and reinforces the argument that institutional quality and economic structure are critical for leveraging natural capital for growth [37,48]. In particular, regions with stronger industrial absorption capacity or more advanced green finance systems are better positioned to convert ecological carbon sinks into sustained economic returns. Nevertheless, the estimated threshold effects are subject to sampling and measurement uncertainty and should be understood as indicative boundaries rather than precise policy cut-off points.

However, our results contrast with some international studies that report linear positive effects of FCS, possibly due to differences in measurement, context, or methodological approaches [56]. This discrepancy underscores the need for context-specific analyses and the importance of considering nonlinear and heterogeneous pathways. It also suggests that carbon sinks function within a broader ecological–industrial system and that their economic effects depend partly on local capabilities to embed ecological assets into industrial chains, land markets, or carbon finance mechanisms. In particular, differences in the definition of FCS, the exclusion of material-substitution effects, and the urban-scale focus of this study may partly explain why nonlinear effects emerge more clearly in this analysis than in some cross-country studies.

6. Research Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Research Conclusions

Based on Chinese urban panel data from 2010 to 2022, this paper examines the relationship between FCS and economic growth through a nonlinear identification farmwork. Using static fixed effects, instrumental-variable fixed-effects estimation, System GMM, and threshold panel models, we systematically investigate both the dynamic and structural characteristics of this relationship. The main conclusions are as follows:

First, FCS are associated with a nonlinear relationship with economic growth. Evidence from the static fixed-effects and IV-FE models indicates a statistically significant nonlinear association between FCS and regional GDP, while the System GMM results provide complementary dynamic evidence consistent with an inverted U-shaped pattern. Within the sample period, lower levels of FCS are associated with economic gains, plausibly linked to ecological restoration, improved environmental quality, and access to green financing. As FCS expand further, however, increasing management costs, land-use constraints, and ecological–economic trade-offs appear to reduce marginal benefits. The System GMM results further suggest a path-dependent process, in which ecological gains tend to arise earlier, whereas structural constraints become more pronounced over time.

Second, the economic effects of FCS exhibit clear regional heterogeneity. Estimates using System GMM show that central regions continue to benefit from FCS and have not yet reached the diminishing-returns stage; western regions display a more pronounced inverted U-shaped pattern, suggesting potential risks of over-reliance on ecological assets; in eastern regions, the effect is weak due to more advanced industrial structures, limited forest land, and stronger competition for urban land. This pattern reflects that ecological assets contribute more strongly to growth in regions where ecological industries, land markets, and green finance systems are at earlier development stages.

Third, institutional and structural conditions modulate the pathways through which FCS affect economic growth. Threshold regression reveals double-threshold effects for industrial structure, urbanization, and government intervention. When these threshold variables surpass critical levels, the marginal impact of FCS becomes significantly stronger, indicating that regions with more mature industrial absorption capacity or more developed green financial systems can better transform ecological carbon sinks into economic value. These findings emphasize that natural capital does not generate growth automatically—its economic returns depend on the capacity of regional institutions and production systems to internalize ecological benefits.

Finally, cities of different administrative levels experience different structural effects. Heterogeneity tests indicate that the inverted U-shaped pattern is more salient in non-central and non-provincial capital cities, where ecological assets constitute a more important component of local development strategies. These cities exhibit greater policy sensitivity and greater potential for carbon sink-driven development, underscoring the im-portance of differentiated ecological asset management.

These findings underscore that FCS influence economic growth through a combination of ecological improvements, green investment channels, carbon market instruments, and industrial spillover effects. Their economic impact is inherently nonlinear, institutionally contingent, and regionally heterogeneous.

6.2. Countermeasures and Recommendations

In response to the aforementioned research findings, this paper proposes the following policy recommendations to achieve synergistic advancement of FCS and economic growth:

- (1)

- Implement targeted policies by region to enhance the quality of carbon sink development in central and western regions. These regions possess abundant forest resources and should further improve ecological compensation systems and carbon trading mechanisms to guide the conversion of ecological capital into development capital. Particularly before the point of diminishing marginal returns, efforts should be made to enhance the integration of green finance and ecological industries to prevent ecological stagnation or resource misallocation.

- (2)

- Improve the efficiency of carbon sink utilization in eastern regions to achieve high-quality green transformation and enhanced efficiency. Eastern cities can leverage technological innovation, industrial upgrading, and green finance to establish a high-quality carbon sink development model, redefine the value of ecological resources, and drive the evolution of FCS toward integration with ecological services and carbon finance. In the long term, eastern regions may also explore the broader carbon value chain—such as promoting timber-based construction materials—to extend the economic benefits of forest resources through material substitution pathways.

- (3)

- Strengthen foundational capacity-building to enhance the coupling capacity between carbon sinks and structural conditions. By optimizing industrial structure, improving the quality of urbanization, and perfecting the government support system, the compatibility between FCS policy tools and regional economic structure can be enhanced, thereby unlocking growth potential under threshold effects.

- (4)

- Provide targeted support to unlock the carbon sink potential of small and medium-sized cities. Considering that non-central cities are more sensitive to FCS, regional coordination, targeted support for ecological projects, and fiscal transfers should be utilized to accelerate their green development capacity building, enabling them to play a foundational supporting role in the national dual-carbon strategy.

6.3. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. The analysis is limited by the lack of city-level data on FCS. The dataset records ecological carbon sequestration at the ecosystem level; however, it lacks comprehensive ecological details like soil quality, species composition, or forest age. These factors may influence both carbon dynamics and economic outcomes.

Second, while our dynamic panel estimation method tackles endogeneity and dynamic adjustment, certain unobserved factors may persist. Local environmental preferences or informal institutional structures are challenging to quantify at the municipal level and cannot be entirely regulated.

Third, spatial interconnections among cities are not the main focus of this study. Additional checks indicate that the primary results are not influenced by unmodeled spatial dependence. However, a more thorough spatial econometric analysis could yield further insights into cross-regional spillovers.

Finally, the results are based on the Chinese institutional environment. Because of this, the nonlinear patterns found here should be taken with a grain of salt when looking at other countries. Places with similar degrees of urbanization, industrial structure, and carbon market growth are more likely to experience similar impacts. In areas without these characteristics, the economic function of FCS may vary.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z. and S.L.; methodology, X.Z. and S.L.; software, S.L.; validation, S.L. and X.Z.; formal analysis, S.L., P.L. and X.Z.; investigation, X.Z. and S.L.; resources, S.N.; data curation, X.Z. and S.L.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, X.Z. and S.L.; project administration, S.L. and P.L.; writing—original draft, X.Z., S.L., P.L. and S.N.; writing—review and editing, X.Z., S.L., P.L. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2024.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the authors used DeepL Translator for the purposes of language polishing and improving readability. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication. We gratefully acknowledge the support provided by Wonkwang University throughout the development of this research. We also express our gratitude to the reviewers and editors for their invaluable recommendations in revising and enhancing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FCS | forest carbon sinks |

| System GMM | system generalized method of moments model |

| CCER | China Certified Voluntary Emission Reduction |

| SDGs | United Nations Sustainable Development Goals |

| RESDC | Resource and Environment Science Data Center |

| NDVI | normalized difference vegetation index |

| GDP | gross domestic product |

| ETS | emissions-trading system |

| RSS | residual sum of squares |

| MSE | mean squared error |