The Effect of Machining Fluid in the Process of Steam-Treated Pine and Beech Wood Turning on Selected Surface Roughness Parameters

Abstract

1. Introduction

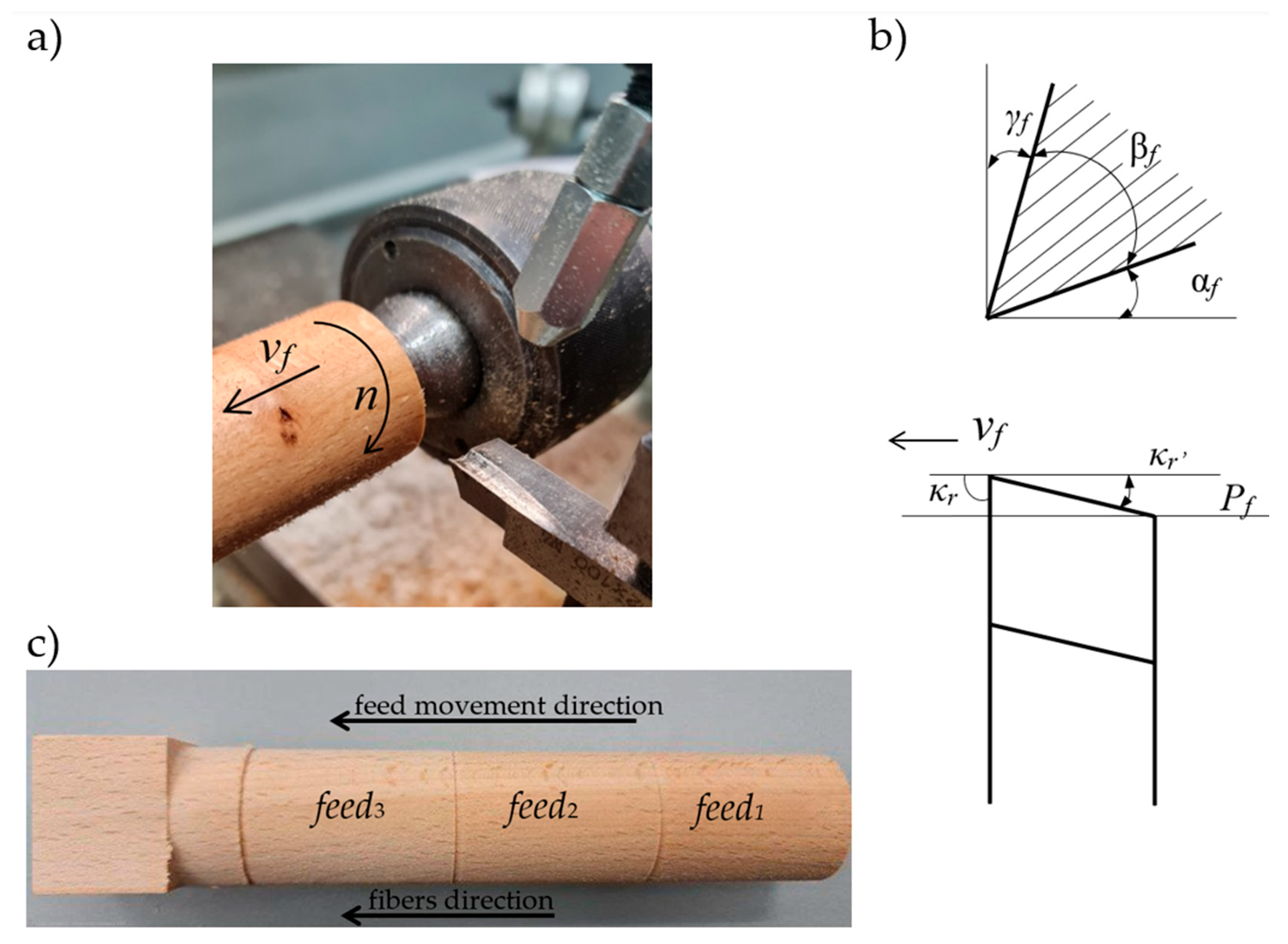

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Machine Tools, Cutting Tools, and Cutting Parameters

2.3. Surface Roughness Measurement

2.4. Statistical Analysis

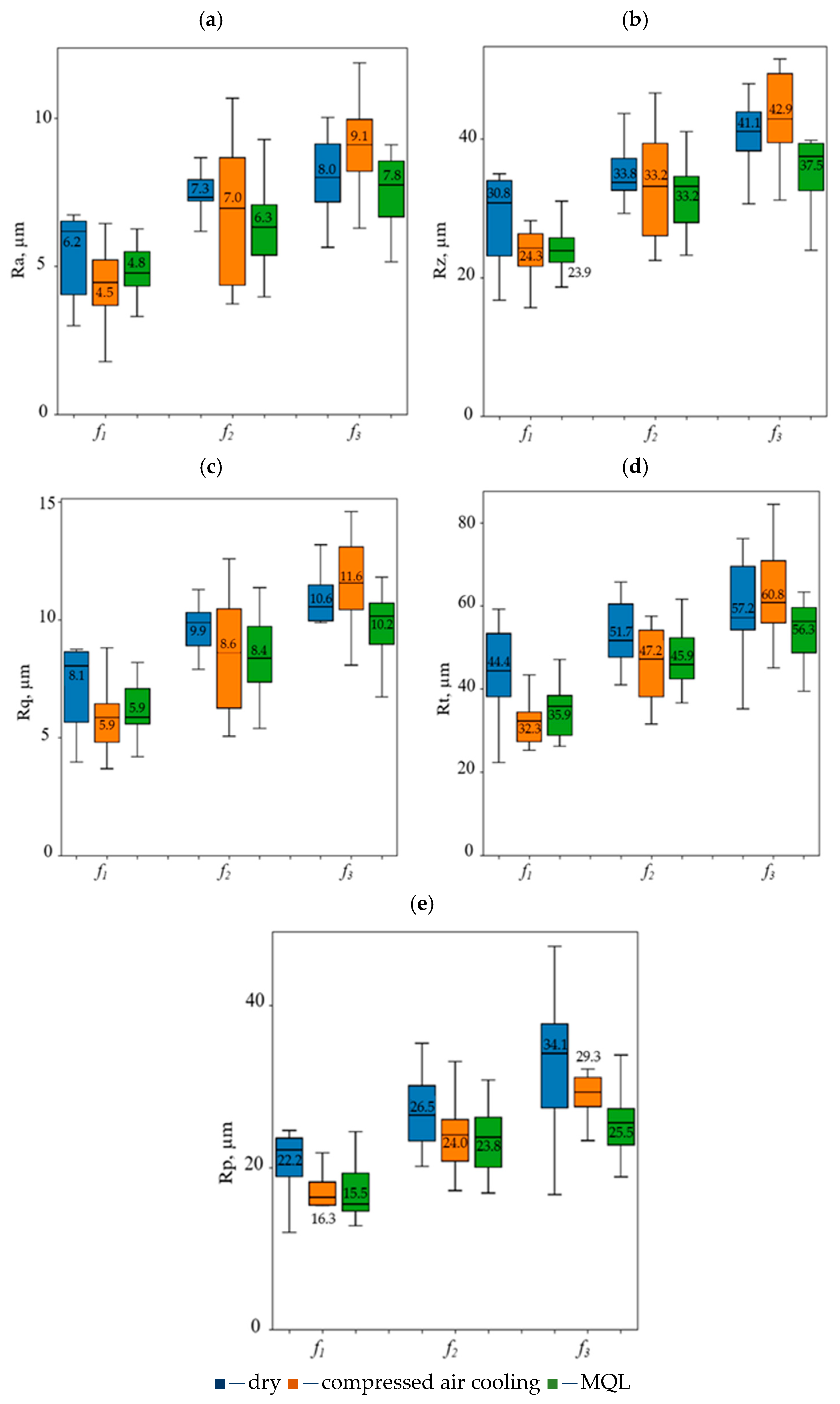

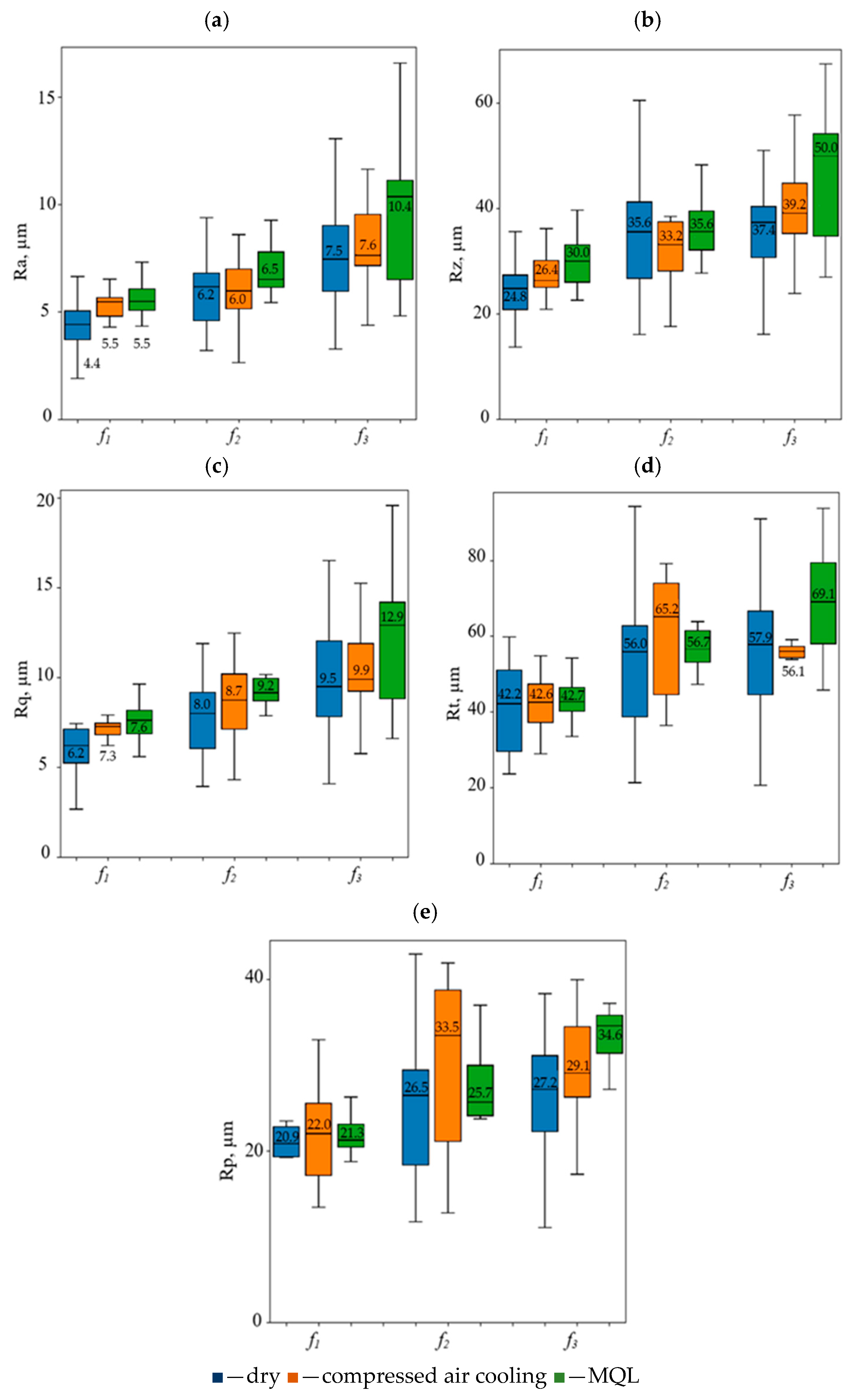

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

- For steam-treated pine wood, MQL provides lower surface roughness values compared to compressed air and dry turning, especially at higher values of feed per revolution.

- In the case of steam-treated beech wood, the lowest surface roughness values are observed during dry turning, while the use of MQL leads to an increase in the values of surface roughness, especially at high feeds per revolution.

- The use of different turning conditions has little effect on changes in surface roughness values. At the same time, increasing the feed per revolution (0.07–0.28 mm) under the same conditions results in statistically significant differences in surface roughness parameters for both pine and beech.

- In the case of pine wood, statistically significant differences were found between adjacent feed rates (f1–f2 and f2–f3) during turning with compressed air cooling. Under dry and MQL turning conditions, the differences between adjacent feed per revolution were not statistically significant.

- For beech wood, with dry conditions and compressed air cooling, the changes in surface roughness parameters between feeds per revolution f1 and f3 were not statistically significant. However, during MQL machining, significant differences in surface roughness were observed for the same feeds per revolution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramage, M.H.; Burridge, H.; Busse-Wicher, M.; Fereday, G.; Reynolds, T.; Shah, D.U.; Wu, G.; Yu, L.; Fleming, P.; Densley-Tingley, D.; et al. The wood from the trees: The use of timber in construction. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 333–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandak, A.; Sandak, J.; Brzezicki, M.; Kutnar, A. Bio-Based Building Skin; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salca, E.-A.; Hiziroglu, S. Evaluation of hardness and surface quality of different wood species as function of heat treatment. Mater. Des. 2014, 62, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásková, L.; Procházka, J.; Novák, V.; Čermák, P.; Kopecký, Z. Interaction between Thermal Modification Temperature of Spruce Wood and the Cutting and Fracture Parameters. Materials 2021, 14, 6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkut, S.; Akgul, M. Effect of drying temperature on surface roughness of oak (Quercus petraea ssp. iberica (Steven ex Bieb) Krassiln) veneer. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 1931–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budakçı, M.; İlçe, A.C.; Korkut, D.S.; Gürleyen, T. Evaluating the surface roughness of heat-treated wood cut with different circular saws. BioResources 2011, 6, 4247–4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ispas, M.; Gurau, L.; Campean, M.; Hacibektasoglu, M.; Racasan, S. Milling of heat-treated beech wood (Fagus sylvatica L.) and analysis of surface quality. BioResource 2016, 11, 9095–9111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogoziński, T.; Chuchala, D.; Pędzik, M.; Orlowski, K.; Dzurenda, L.; Muziński, T. Influence of drying mode and feed per tooth rate on the fine dust creation in pine and beech sawing on a mini sash gang saw. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. (Holz Roh Werkst.) 2021, 79, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásková, L.; Kopecký, Z.; Novák, V. Influence of wood modification on cutting force, specific cutting resistance and fracture parameters during the sawing process using circular sawing machine. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2020, 78, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuchala, D.; Orlowski, K.; Hiziroglu, S.; Wilmanska, A.; Pradlik, A.; Mietka, K. Analysis of surface roughness of chemically impregnated Scots pine processed using frame-sawing machine. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 18, 1809–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudiak, M.; Kminiak, R.; Banski, A.; Chuchala, D. The Effect of Steaming Beech, Birch and Maple Woods on Qualitative Indicators of the Surface. Coatings 2024, 14, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavenetidou, M.; Kamperidou, V. Impact of wood structure variability on the surface roughness of chestnut wood. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitosytė, J.; Ukvalbergienė, K.; Keturakis, G. Roughness of sanded wood surface: An impact of wood species, grain direction and grit size of abrasive material. Mater. Sci. 2015, 21, 255–259. [Google Scholar]

- Thoma, T.; Peri, L.; Lato, E. Evaluation of wood surface roughness depending on species characteristics. Maderas Cienc. Tecnol. 2015, 17, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandak, J.; Tanaka, C. Evaluation of surface smoothness by laser displacement sensor 1: Effect of wood species. J. Wood Sci. 2003, 49, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobrzynski, M.; Orlowski, K.A.; Biskup, M. Comparison of surface quality and tool-life of glulam window elements after planning. Drv. Ind. 2019, 70, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, M.; Hiziroglu, S.; Burdurlu, E. Effect of machining on surface roughness of wood. Build. Environ. 2006, 41, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkoçoǧlu, A. Machining properties and surface roughness of various wood species planed in different conditions. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 2562–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siklienka, M.; Mišura, L. Influence of saw blade clearance over the workpiece on tool-wear. Drv. Ind. 2008, 59, 151–155. [Google Scholar]

- Iskra, P.; Hernández, R.E. The influence of cutting parameters on the surface quality of routed paper birch and surface roughness prediction modeling. Wood Fiber Sci. 2009, 41, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Chladil, J.; Sedlák, J.; Šebelov, E.R.; Kučera, M.; Dado, M. Cutting conditions and tool wear when machining wood-based materials. BioResources 2019, 14, 3495–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Li, R.; Cao, P.; Ekevad, M.; Cristóvão, L.; Marklund, B.; Grönlund, A. Effect of average chip thickness and cutting speed on cutting forces and surface roughness during peripheral up milling of wood flour/polyvinyl chloride composite. Wood Res. 2015, 60, 147–156. [Google Scholar]

- Sedlecký, M.; Gašparík, M. Power Consumption during Edge Milling of Medium-Density Fiberboard and Edge-Glued Panel. BioResources 2017, 1, 7413–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.C.; Hernández, R.E.; Blais, C. Effect of knife wear on surface quality of black spruce cants produced by a chipper-canter. Wood Fiber Sci. 2015, 47, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.E.; de Moura, L.F. Effects of knife jointing and wear on the planed surface quality of northern red oak wood. Wood Fiber Sci. 2007, 3, 540–552. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández, R.E.; Rojas, G. Effects of knife jointing and wear on the planed surface quality of sugar maple wood. Wood Fiber Sci. 2007, 34, 293–305. [Google Scholar]

- Nasir, V.; Cool, J. A review on wood machining: Characterization, optimization, and monitoring of the sawing process. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bendikiene, R.; Keturakis, G. The effect of tool wear and planning parameters on birch wood surface roughness. Wood Res. 2016, 61, 791–798. [Google Scholar]

- Gurau, L.; Csiha, C.; Mansfield-Williams, H. Processing roughness of sanded beech surfaces. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2015, 73, 395–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau, L.; Mansfield-Williams, H.; Irle, M. Processing roughness of sanded wood surfaces. Holz Roh Werkst. 2005, 63, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škaljić, N.; Beljo Lučić, R.; Čavlović, A.; Obučina, M. Effect of feed speed and wood species on roughness of machined surface. Drv. Ind. 2009, 60, 229–234. [Google Scholar]

- Stanojevic, D.; Mandic, M.; Danon, G.; Svrzic, S. Prediction of the surface roughness of wood for machining. J. For. Res. 2017, 28, 1281–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yan, P.; Zhu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Jiao, L.; Wang, X. Effect of cutting fluid on machined surface integrity and corrosion property of nickel based superalloy. Materials 2023, 16, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vineet, D.; Sharma, K.A.; Vats, P.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Giasin, K.; Chuchala, D. Study of a Multicriterion Decision-Making Approach to the MQL Turning of AISI 304 Steel Using Hybrid Nanocutting Fluid. Materials 2021, 14, 7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez Battez, A.; Viescaa, J.L.; Gonzaleza, R.; Blancob, D.; Asedegbegab, E.; Osorioa, A. Friction reduction properties of a CuO nanolubricant used as lubricant for a NiCrBSi coating. Wear 2010, 268, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuchala, D.; Sommer, A.; Orlowski, K.; Staroszczyk, H.; Mania, S.; Sandak, J. Effect of applied standard wood machining fluid on colour and chemical composition of the machined wood surface. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2024, 82, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staszczyk, K.; Sommer, A.; Mania, S.; Orlowski, K.; Staroszczyk, H.; Chuchala, D. Effect of selected solvents on the properties of glue, wood surface and adhesive force during bio-machining fluid development. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2025, 83, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klement, I.; Vilkovská, T.; Barański, J.; Konopka, A. The impact of drying and steaming processes on surface color changes of tension and normal beech wood. Dry. Technol. 2019, 37, 1490–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konopka, A.; Chuchala, D.; Orlowski, K.; Tatiana, V.; Klement, I. The effect of beech wood (Fagus sylvatica L.) steaming process on the colour change versus depth of tested wood layer. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivimaa, E. Cutting Force in Wood Working; State Institute for Technical Research: Helsinki, Finland, 1950; p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Gurau, L.; Irle, M. Surface roughness evaluation methods for wood products: A review. Curr. For. Rep. 2017, 3, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 21920-1; Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS)—Surface Texture: Profile—Part 1: Indication of Surface Texture. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Sandak, J.; Negrı, M. Wood Surface Roughness—What is it? In Proceedings of the 17th International Wood Machining Seminar, Rosenheim, Germany, 26–28 September 2005; Volume 1, pp. 242–250. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, L. Applied Statistics: A Handbook of Techniques, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gurau, L.; Irle, M.; Buchner, J. Surface Roughness of Heat Treated and Untreated Beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) Wood after Sanding. BioResources 2019, 14, 4512–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogutlu, C. The effect of the feeding direction and feeding speed of planing on the surface roughness of oriental beech and Scotch pine woods. Wood Res. 2010, 55, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cutting speed | vc | 2.95 | m·s−1 |

| Feed per revolution | f1 | 0.07 | mm |

| f2 | 0.14 | mm | |

| f3 | 0.28 | mm | |

| Depth of cut | ap | 0.5 | mm |

| Air flow rate | qa | 0.4 | m3·h−1 |

| Air pressure | p | 0.5 | MPa |

| Fluid flow rate | qf | 0.18 × 10−3 | m3·h−1 |

| Pine Wood | Ra | Rz | Rq | Rt | Rp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | |||||

| f1d, f2d | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.50 | 0.45 |

| f1d, f3d | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.001 |

| f2d, f3d | 0.99 | 0.59 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.23 |

| f1a, f2a | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.06 |

| f1a, f3a | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| f2a, f3a | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.34 |

| f1o, f2o | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.28 |

| f1o, f3o | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.03 |

| f2o, f3o | 0.77 | 0.96 | 0.77 | 0.87 | 0.99 |

| Beech Wood | Ra | Rz | Rq | Rt | Rp |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-Value | |||||

| f1d, f2d | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 0.91 |

| f1d, f3d | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.69 |

| f2d, f3d | 0.84 | 1.00 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| f1a, f2a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.96 | 0.14 | 0.37 |

| f1a, f3a | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.58 | 0.21 |

| f2a, f3a | 0.38 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| f1o, f2o | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.86 | 0.60 | 0.99 |

| f1o, f3o | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.03 |

| f2o, f3o | 0.96 | 0.12 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.26 |

| Pine | f1d, f1a, f1o | f2d, f2a, f2o | f3d, f3a, f3o | f1d, f2d, f3d | f1a, f2a, f3a | f1o, f2o, f3o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | F | 1.43 | 0.74 | 2.97 | 11.07 | 16.06 | 10.97 |

| p | 0.26 | 0.48 | 0.07 | 3.08 × 10−4 | 2.54 × 10−5 | 3.27 × 10−4 | |

| Rz | F | 2.15 | 0.45 | 4.60 | 11.67 | 18.04 | 14.19 |

| p | 0.14 | 0.64 | 0.02 | 2.23 × 10−4 | 1.06 × 10−5 | 6.15 × 10−5 | |

| Rq | F | 2.48 | 1.21 | 2.52 | 9.85 | 18.86 | 16.56 |

| p | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 6.12 × 10−4 | 7.50 × 10−6 | 8.40 × 10−5 | |

| Rt | F | 3.30 | 1.94 | 1.65 | 4.72 | 18.53 | 17.85 |

| p | 0.05 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 1.75 × 10−2 | 8.60 × 10−6 | 1.15 × 10−5 | |

| Rp | F | 3.34 | 1.83 | 3.46 | 6.63 | 22.04 | 9.34 |

| p | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.05 | 4.55 × 10−3 | 2.11 × 10−6 | 8.26 × 10−4 | |

| Beech | f1d, f1a, f1o | f2d, f2a, f2o | f3d, f3a, f3o | f1d, f2d, f3d | f1a, f2a, f3a | f1o, f2o, f3o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ra | F | 3.76 | 0.36 | 1.23 | 5.79 | 6.85 | 7.87 |

| p | 0.04 | 0.70 | 0.31 | 8.10 × 10−3 | 4.07 × 10−3 | 2.03 × 10−3 | |

| Rz | F | 1.84 | 0.45 | 1.38 | 3.74 | 7.26 | 8.03 |

| p | 0.18 | 0.64 | 0.27 | 3.68 × 10−2 | 3.13 × 10−3 | 1.83 × 10−3 | |

| Rq | F | 2.10 | 0.54 | 0.97 | 4.16 | 4.85 | 8.09 |

| p | 0.14 | 0.59 | 0.39 | 2.67 × 10−2 | 1.62 × 10−2 | 1.85 × 10−3 | |

| Rt | F | 0.14 | 0.41 | 2.19 | 2.08 | 5.56 | 15.54 |

| p | 0.87 | 0.66 | 0.13 | 1.45 × 10−1 | 1.04 × 10−2 | 5.78 × 10−5 | |

| Rp | F | 0.31 | 0.96 | 1.95 | 1.73 | 3.04 | 8.97 |

| p | 0.73 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 1.97 × 10−1 | 6.46 × 10−2 | 1.03 × 10−3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Majek, M.; Karatkevich, Z.; Vilkovský, P.; Kminiak, R.; Chuchala, D. The Effect of Machining Fluid in the Process of Steam-Treated Pine and Beech Wood Turning on Selected Surface Roughness Parameters. Forests 2026, 17, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010024

Majek M, Karatkevich Z, Vilkovský P, Kminiak R, Chuchala D. The Effect of Machining Fluid in the Process of Steam-Treated Pine and Beech Wood Turning on Selected Surface Roughness Parameters. Forests. 2026; 17(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajek, Marta, Zoya Karatkevich, Peter Vilkovský, Richard Kminiak, and Daniel Chuchala. 2026. "The Effect of Machining Fluid in the Process of Steam-Treated Pine and Beech Wood Turning on Selected Surface Roughness Parameters" Forests 17, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010024

APA StyleMajek, M., Karatkevich, Z., Vilkovský, P., Kminiak, R., & Chuchala, D. (2026). The Effect of Machining Fluid in the Process of Steam-Treated Pine and Beech Wood Turning on Selected Surface Roughness Parameters. Forests, 17(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010024