Abstract

Forest canopies effectively remove airborne particles, reducing the frequency of atmospheric haze and improving air quality as well as playing a crucial role in maintaining human health. In this study, we examined the retention of particulate matter by Picea crassifolia Kom. (P. crassifolia) needles using an aerosol regenerator in two typical catchments, while the concentrations of dissolved trace elements (Na, Zn, Pb, and Cd) were determined only in the Tianlaochi catchment. The results showed that the retention of airborne particles was lower in the Tianlaochi catchment (e.g., total suspended particles (TSP): 0.0049 μg cm−2 in summer) than in the Sancha catchment (e.g., TSP: 0.0145 μg cm−2) in summer and autumn, while the opposite trend was found in winter and spring, with Tianlaochi catchment reaching higher TSP levels (0.0230 μg cm−2 in spring) compared to Sancha catchment (0.0205 μg cm−2). The big tree exhibited the highest particulate retention, with a maximum flux of 84.870 μg cm−2, indicating it was the most effective at particle trapping. The highest Na, Zn, Cd, and Pb values absorbed by the needle samples were 1.794 mg L−1, 11.345 μg L−1, 0.081 μg L−1, and 4.316 μg L−1, respectively. P. crassifolia needles absorbed more Na, Zn, and Cd in July and August than in June. The absorption capacity of the needles decreased in the order Na > Zn > Pb > Cd. P. crassifolia forest can effectively reduce airborne particulate matter. Our study provides a theoretical foundation to examine the role of forest ecosystems in the retention of atmospheric particulate matter in the Qilian Mountains region.

1. Introduction

Air particles, particularly fine particles, have a strong scattering effect that reduces air visibility and causes atmospheric haze [1]. The concentration of air particles can effectively reflect regional air purification, which is the clearest indicator of air quality [2]. Based on particle diameter, air particles can be divided into total suspended particles (TSP, particle size ≤ 100 μm), inhalable particulate matter (PM10, particle size ≤ 10 μm), fine particles (PM2.5, particle size ≤ 2.5 μm), and ultrafine particles (PM1, particle size ≤ 1 μm) [3]. Air particles can significantly impact on human health [4]. At present, the global problem of particulate matter pollution remains severe, and particulate matter is the main pollutant that endangers human health and ecosystems. The World Health Organization reported that outdoor air pollution in urban and rural areas caused an estimated 4.2 million premature deaths in 2019 [5]. Exposure to fine particles can cause mortality due to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and cancer. Therefore, studying changes in air particles is crucial for both the atmospheric environment and human health.

In recent years, the issue of how to reduce the concentration of airborne particles and control atmospheric haze has become an important and challenging area of scientific research [6]. One of the principal methods for haze prevention and mitigation is the interception of particulate matter by vegetation. Plants increase ground surface roughness, reducing wind speeds and increasing deposition of airborne particulate matter, and also capture airborne particles due to their large canopies, vast leaf surface area and surface structures [7]. This reduces the concentration of atmospheric particulates, purifying the air and improving environmental quality. Many studies have shown that the retention and adsorption of airborne particulate matter by plants can effectively reduce air pollution [8,9,10]. Beckett et al. [11] concluded that coniferous plants are more effective at adsorbing airborne particulate matter than broadleaf species, which may be due to their leaf function and structure and complex branch and stem structure, among other factors. Freer-Smith et al. [12] studied the ability of three broadleaf and conifer species in the United Kingdom to capture particulate matter, showing that oil pine had the greatest ability to trap both coarse and fine particulate matter, followed by rowan and triangular-leafed poplar. Nowak et al. [13] found that vegetation canopies in 10 cities in the United States can directly remove 4.7–64.5 t a−1 of airborne PM2.5 in a year. Zhang et al. [14] modeled the removal of 2.85 × 107 t PM2.5 from the atmosphere by dry deposition in the Three-North Shelter Forest in China between 1999 and 2010. While vegetation is widely recognized for its capacity to capture atmospheric particulate matter globally, the effectiveness of this ecosystem service is highly dependent on local environmental conditions and specific plant traits.

Studies on airborne particulate matter retention have focused on the adsorption of particulate matter by urban plants [15]. However, the retention of airborne particulate matter by ecosystems in remote areas has been less studied. Currently, the main methods used to quantify the capture of airborne particulate matter by forests include aerosol regenerators, filter membrane methods, scanning electron microscopy, mass difference subtraction, and ultrasonically cleaned elution-based weighing particle size analysis [16]. Most research on the capacity of forest leaves to capture airborne particulate matter has primarily relied on a single method, with few studies integrating multiple approaches.

Forests are a crucial component of the earth’s natural resources and terrestrial ecosystems. Forests perform a wide range of important ecological functions, including nitrogen fixation, oxygen release, water conservation, wind and sand prevention, water and soil conservation, and protection of species diversity [17,18,19]. The importance of forests in purifying the atmosphere cannot be underestimated; however, this vital function has often been overlooked. Forest ecosystems can degrade and purify toxic substances in the air, reduce noise pollution, and produce negative ions and terpenes through processes such as absorption, filtration, blocking, and decomposition [20]. Plant purification is the process by which plants use metabolic processes (alienation and assimilation) to remove potentially harmful pollutants from the environment, including the purification of atmospheric pollution by terrestrial plants and the purification of water pollution by aquatic plants. Air purification is primarily achieved through the leaves by (1) absorbing CO2 and releasing O2; (2) retaining and filtering floating dust; (3) absorbing harmful gases including SO2, HF, Cl2, and O3 within the plant resistance range; (4) reducing photochemical smoke pollution within the resistance range; (5) filtration or sterilization; (6) absorption and purification of heavy metals in particulate matter; and (7) reducing noise pollution and radioactive contamination [21]. Particulate matter is a significant atmospheric pollutant and forests can block, filter, and adsorb particulate matter. The dust retention capacity of plant leaves is related to the size of their stomata, and species with larger stomata tend to have a greater dust retention capacity [22]. Wang et al. [23] conducted a study on common deciduous tree species in Beijing and showed that Koelreuteria paniculata and Robinia pseudoacacia retained the most particulate matter (of different particle sizes) per unit area of leaves, while Populus had the lowest retention value. Guo et al. [24] reported that Picea asperata and Pinus tabulaeformis are effective at retaining dust. These studies show that there are significant differences in the dust retention capabilities of tree species, which are mainly due to differences in crown shape, branch and leaf arrangement, leaf morphology, and leaf cross-section. In addition to forest structure and vegetation characteristics, the capacity of forests to retain airborne particulate matter is also influenced by factors such as wind speed and turbulence, temperature and seasonal variations, as well as humidity and precipitation. For instance, previous studies have simulated the effects of precipitation, rainfall amount, and rainfall frequency on the accumulation, retention, and resuspension processes of particulate matter on plant leaves [25,26].

Atmospheric particulates can contain trace metals including As, Cu, Cd, Cr, Mn, Pb, Ni, Zn, and Co [27,28]. These metals can enter the human body through various pathways and can pose a threat to human health. Several studies have demonstrated an association between particulate matter and lung diseases, such as lung cancer, and heart disease [29,30,31,32]. PM1 can contains sulfates, nitrates, and trace elements including Cu, Pb, Zn, Cd, and Ni [33,34,35]. Plant leaves can absorb trace elements in atmospheric particulate matter. The particulate matter adheres to the leaf surface, coming into direct contact with the leaf. Trace elements can then enter the interior of the leaf through the stomata, potentially damaging the plant. Leaf uptake via stomata is particularly significant for elements with high atmospheric deposition but low soil bioavailability (e.g., Pb, Cd). It becomes the dominant pathway at local scales near emission sources or in regions where atmospheric input substantially exceeds soil input, such as arid, high-deposition areas like the Qilian Mountains. Therefore, reducing the adsorption of particulate matter by trees by preventing and controlling air pollution is of great significance.

The Qilian Mountains are located in the northeast of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and span the Gansu and Qinghai provinces in China. The mountains serve as a natural barrier against the southern encroachment of the Tengger, Badain Jaran, and Kumtag deserts and are a critical ecological security barrier and vital water source in western China. They are also a significant ecological functional area and a priority area for biodiversity conservation in China. As a critical ecological barrier, the Qilian Mountains face atmospheric deposition pressures comparable to those in other fragile mountain or dryland regions globally, such as the Mediterranean Atlas, the eastern slopes of the Australian Alps, and parts of the Himalayan foothills, where vegetation plays a vital role in intercepting both natural dust and anthropogenic particles. At present, the air quality in the Qilian Mountains region is affected by various factors such as global warming and increased human activities, leading to an increase in the vulnerability and risk level of the climate and ecological environment. Studies on air quality in the Qilian Mountains have addressed various aspects, including atmospheric deposition in forests [36], particulate matter sources and transport [37], aerosol chemical characteristics [38], glacial dust properties [39], and anthropogenic aerosols’ role in cloud formation [40]. P. crassifolia is the dominant tree species in the Qilian Mountains, covering an area of approximately 132,806.8 ha. Due to its needles containing numerous stomata and its large specific leaf area, P. crassifolia can effectively capture particulate matter provided that conditions are favorable [8]. Therefore, the objectives of this study are: (1) investigate the TSP, PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 retention capacity of P. crassifolia in two typical catchments in the Qilian Mountains using an aerosol regenerator; (2) examine the effects of needle location and tree age on particulate flux using the elution-weighing method; and (3) assess the concentrations of dissolved trace elements (Na, Zn, Pb, and Cd) in particulate matter adsorbed on the needle of P. crassifolia in the Tianlaochi catchment. We hypothesize that (1) the retention capacity of P. crassifolia for particulate matter (TSP, PM10, PM2.5, and PM1) varies significantly between seasons and is influenced by catchment-specific environmental conditions; (2) big trees possess a greater capacity to retain airborne particles compared to medium and small trees within the same stand; and (3) the concentration of dissolved trace elements (Na, Zn, Pb, and Cd) on needles varies both temporally (across seasons) and spatially (with tree height or location), reflecting differences in deposition sources and pathways. This study addresses a key knowledge gap by integrating two complementary techniques to quantify particulate matter retention by P. crassifolia in the Qilian Mountains, and by uniquely evaluating trace elements from both environmental and ecological perspectives to inform regional policy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

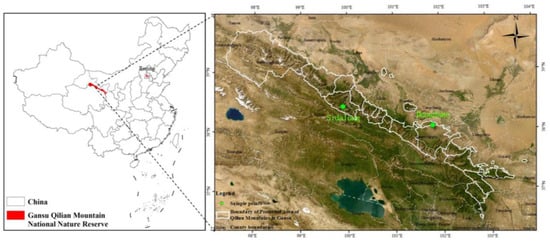

Two typical small catchments in the center of the Qilian Mountains were selected: the Tianlaochi and Sancha catchments (Figure 1). The Tianlaochi catchment (99°53′57″–99°57′10″ E, 38°23′56″–38°26′47″ N) is located in the Sidalong Nature Reserve Station (Sidalong) and has an altitude of 2600–4400 m. The climate is primarily alpine semi-arid and semi-humid. While 2022 precipitation aligned with long-term averages, the findings may vary in drier or wetter years, a factor to consider for inter-annual comparison. Based on the meteorological station records from the study area for the year 2022, the annual mean temperature was 0.9 °C with a total precipitation of 500 mm. The annual evaporation was 1264 mm, and the typical frost-free period ranges from 90 to 120 d [41]. Dust events in the region occur predominantly from March to May, with annual dust storm days exceeding 10, classifying the area as a dust storm-prone zone. Along the elevational gradient of the mountain terrain, soil and vegetation exhibit distinct vertical zonation. The main soil types consist of mountain grey-cinnamon soil, mountain chestnut soil, alpine meadow soil, and frigid desert soil [36]. P. crassifolia. is the dominant tree species in the catchment. Its forests are distributed on north-facing slopes at elevations between 2600 and 3540 m. Subalpine shrubland, dominated by Potentilla fruticosa L. and Caragana jubata, occurs between 3250 and 3750 m. Subalpine steppe, found on sunny and semi-sunny slopes at 2900–3100 m, is primarily composed of Elymus nutans Griseb., Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Polygonum viviparum L., Carex spp., and Potentilla anserina L., collectively covering 3.50% of the catchment area. Alpine bare rock and permanent snow/ice zones are present above 3800 m [36,42].

Figure 1.

The study area.

The Sancha catchment (101°24′04″–102°09′41″ E, 38°01′44″–38°09′48″ N) is situated within the Dongdahe Nature Reserve Station (Dongdahe) and has an altitude of 2500–4200 m. According to meteorological records for the year 2022, the catchment experienced an annual mean temperature of 5.6 °C and received a total annual precipitation of 290 mm. The Sancha catchment features a semi-arid alpine mountain climate. The soil types primarily consist of mountain grey-brown soil, mountain chestnut soil, alpine meadow soil, and frigid desert soil. P. crassifolia is the dominant forest species in this catchment. The grassland vegetation is mainly composed of Achnatherum splendens, Agropyron cristatum, and Peganum harmala.

P. crassifolia, a species within the Pinaceae family, is endemic to China. This conifer reaches heights of 23 m and occupies montane habitats at 1600–3800 m elevation across the Qilian Mountains (Qinghai, Gansu), Ningxia, and Inner Mongolia’s Daqingshan Mountains. It typically forms monodominant stands in valleys and shaded slopes, exhibiting slow growth rates and ecological adaptations including cold, drought, and nutrient-poor soil tolerance. The species demonstrates a preference for cold, humid environments. The Tianlaochi catchment covers an area of approximately 12.8 km2, with P. crassifolia forest encompassing 25.39% of its land area [42]. The Sancha catchment covers an area of approximately 66.2 km2, with P. crassifolia forest accounting for 18.43% of its area. The locations of meteorological stations in the two catchments are within a fixed sample plot (Figure 1). The monthly variations of meteorological factors (wind speed, wind direction, air temperature, relative humidity, precipitation) in the Tianlaochi and Sancha catchments are shown in Supplementary Materials Table S1. The prevailing winds in both catchments are primarily south-to-southwesterly, consistent with the general atmospheric circulation pattern in the Qilian Mountains region. The Sancha catchment exhibits greater seasonal variation in wind direction, notably with dominant westerly winds in autumn, which may be associated with local topography or circulation differences.

2.2. Forest Retention of Airborne Particles

The samples in this study were collected from fixed sample plots of P. crassifolia in the two catchments. Within the fixed sample plots, per-tree surveys were conducted to determine diameter at breast height (DBH) and tree height. Based on the results of the per-tree survey, three standing trees with diameter at breast height near the mean were selected as average standard trees (Table 1). In selecting the standard trees, normal trees that did not undergo stem bending and did not fork at the base were chosen. The sample plots were located at an altitude of 2850 m in the Tianlaochi catchment (99°54′22″ E, 38°26′31″ N) and 2838 m in the Sancha catchment (101°48′27″ E, 38°06′05″ N). Three standard trees were selected in each catchment based on the following criteria: they were dominant, healthy individuals representative of the local P. crassifolia stand, with similar age, size, and canopy structure. This approach aimed to control for intraspecific variability and focus the investigation on the comparative effects of altitude and season between the two catchments. Samples were collected from the selected trees across four seasons: summer (June 2022), autumn (September 2022), winter (January 2023), and spring (March 2023). The samples were collected using pruning shears from the eastern, southern, western, and northern parts of the upper, middle and lower layers of each tree canopy, and were sealed in the sample bags, marked, stored in cold storage at 4 °C, and then sent to a laboratory to analyze the particulate matter retention capacity.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sampling sites for P. crassifolia in the Tianlaochi and Sancha catchments.

2.3. Needle Sampling for Dissolved Trace Elements Analysis

To determine the concentration of trace elements in the particulate matter, needle samples were collected from the fixed sample plot of the P. crassifolia forest in the Tianlaochi catchment. For each of three size classes (big, medium, and small), three representative trees were selected based on height and diameter at breast height (DBH), providing biological replicates (n = 3 per class). The basic information of P. crassifolia trees of different sizes in the Tianlaochi catchment is shown in Table 2. From each tree, needle samples were collected monthly in June, July, and August. At each sampling, one sample was taken from each of the four cardinal directions (east, west, north, and south) within both the middle and lower canopy layers, resulting in a total of 8 samples per tree per month. All samples were promptly transported to the laboratory for analysis.

Table 2.

Characteristics of P. crassifolia trees of different sizes in the Tianlaochi catchment.

2.4. Chemical Analysis

An aerosol regenerator was used to analyze the particle retention of P. crassifolia needles. The air aerosol regenerator consisted of two main parts: the QRJZFSQ aerogel regenerator (Liaoning Lida, Jinzhou, China) and Dustmate dust particle detector (Turnkey Instruments Ltd., Northwich, UK). The QRJZFSQ aerogel regenerator utilizes the principle of wind erosion to resuspend particles that have adhered to the blade within its inner chamber. The Dustmate dust particle detector can detect changes in TSP, PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 levels before and after air outlet treatment. The particle retention capacity of the tested blade per unit area was calculated by detecting the change in particle concentration in the inner chamber, measuring the blade’s surface area with the drainage method, and combining it with the internal volume (1100 mm × 600 mm × 600 mm). The measurement range of the aerosol regenerator is 0–6000 μg m−3. It had a minimum detection limit of 10 μg m−3 and a measurement accuracy of 0.01 μg m−3. The gas flow rate is 10 L min−1 and the resuspension process lasts for 6 min. The aerosol regenerator should be in a closed environment with low air flow and an outside ambient air humidity value of 40%–50%. The air temperature in the inner chamber shall not be higher than 35 °C.

The needles of this experiment were selected based on different forest ages (big, middle and small trees) of P. crassifolia. The number of branches in each layer (middle and lower layers) was counted according to the branch basal diameter, and three standard branches with good growth were selected in each of the four directions. Finally, we collected needles from every branch of P. crassifolia in every layer and direction of the tree crown. After the calculation, approximately 1290 needles from each standard branch were placed in a beaker to ensure experimental consistency. A volume of 200 mL deionized water (maintained at 25 °C) was added to soak and clean the needles. The beaker was then placed on a magnetic stirrer and gently mixed for 30 min to facilitate the detachment of deposited particulate matter. Following the cleaning process, the needles were removed, and the resulting suspension was filtered through a 0.45 μm polyester fiber membrane. Finally, the particulate flux and the concentrations of dissolved trace elements were determined from the filtered solution.

Replicates of the samples and method blanks were used for quality control and assurance. Each experiment has three duplicate samples to ensure the accuracy of the results. The solution samples were digested with 1% HNO3. The total Na, Zn, Pb, and Cd concentrations in the solution samples were analyzed using an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (7800 ICP-MS, Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). The digestion blanks were below the detection limits of ICP-MS. All glassware containers used in this study were soaked in 10% (v/v) HNO3 for 24 h and then rinsed with tap water and deionized water. The detection limits of Na, Zn, Pb, and Cd in ICP-MS were 0.9011, 0.4028, 0.1800, and 0.0545 µg L−1, respectively.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

The measured data were analyzed using One-way ANOVA with Duncan’s method in SPSS 20.0 software. One-way ANOVA was applied to assess significant differences in three comparisons: airborne particle retention across seasons for a given particle size (n = 3); particulate flux of individual trees across months and regions (n = 3); and dissolved trace element concentrations from the same tree across months and sampling positions (n = 3). This method assumes that only one factor (i.e., the independent variable) differs between groups, and that all other factors that could affect the results are the same across groups. Duncan’s method is a method of multiple comparisons used to perform two-by-two comparisons in analyzing variance to determine significant differences between groups. The data were tested to ensure they met the assumptions for ANOVA. The normality of residuals was verified using the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances across groups was assessed with Levene’s test. All conditions were satisfied. The significance level is p < 0.05. Data are presented as mean ± standard error. The chart was created using Excel 2019, and the study area map was generated using ArcGIS 10.8.

3. Results

3.1. Forest Retention Capacity of Airborne Particles

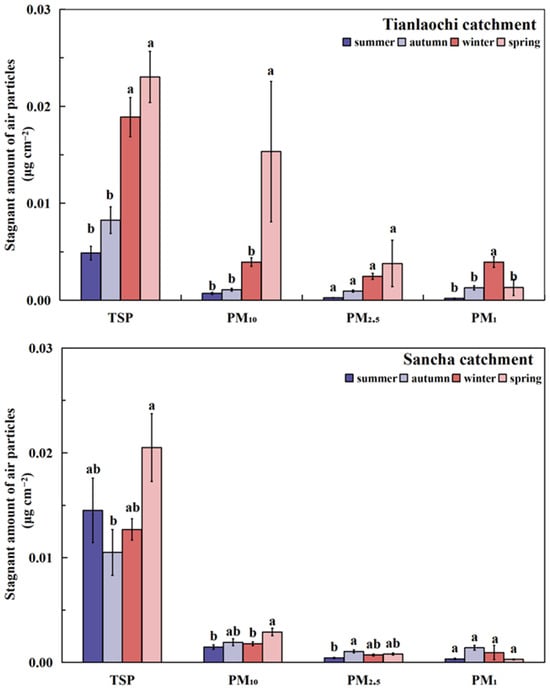

The retention capacity of P. crassifolia forest varied across the two study sites and the different seasons (Figure 2). The TSP levels in the needles samples from the Tianlaochi catchment were highest in spring (0.0230 μg cm−2), followed by winter (0.0189 μg cm−2), autumn (0.0083 μg cm−2), and then summer (0.0049 μg cm−2). In the Tianlaochi catchment, P. crassifolia exhibited significant seasonal variation in particulate retention: TSP retention was significantly higher in winter and spring than in summer and autumn (p < 0.05); PM10 retention peaked in spring compared to the other three seasons (p < 0.05); no significant seasonal difference was observed for PM2.5 (p > 0.05); and PM1 retention was significantly greater in winter than in the remaining seasons (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

The stagnant amount of air particles in P. crassifolia. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between different seasons with the same particle size. The same lowercase letters represent no significant differences within the group, while different lowercase letters represent significant differences within the group.

In the Sancha catchment, TSP levels in the needles were highest in spring (0.0205 μg cm−2), followed by summer (0.0145 μg cm−2), winter (0.0127 μg cm−2), and then autumn (0.0105 μg cm−2). The PM10 retention capacity was highest in spring (0.0029 μg cm−2), followed by autumn (0.0019 μg cm−2), winter (0.0018 μg cm−2), and then summer (0.0015 μg cm−2). In the Sancha catchment, P. crassifolia showed significant seasonal differences in particulate retention: TSP retention was significantly higher in spring than in autumn (p < 0.05); PM10 retention was greater in spring than in summer and winter (p < 0.05); PM2.5 retention was higher in autumn than in summer (p < 0.05); and no significant seasonal variation was detected for PM1 (p > 0.05). The TSP retention capacity of the trees in the Sancha catchment was higher than that in the Tianlaochi catchment, while the PM10, PM2.5 and PM1 retention capacities in the Sancha catchment were lower than in the Tianlaochi catchment. In spring, it was higher than the retention capacity to TSP and PM10 by P. crassifolia needles of the Tianlaochi catchment.

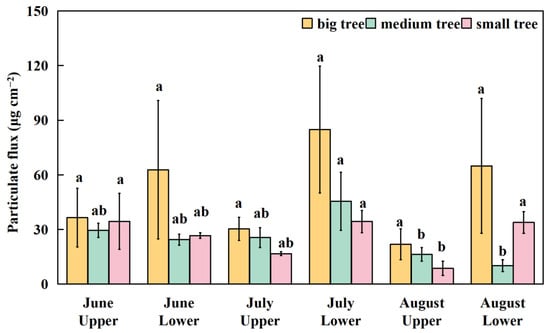

3.2. Flux of the Particulate Matter in Needle of P. crassifolia

The results showed that the particulate flux of the big tree was higher than that of the middle tree and small tree in the Tianlaochi catchment (Figure 3). The particulate flux on P. crassifolia needles showed different patterns by tree size. For big trees, no significant differences were detected across months or canopy heights (p > 0.05). Medium trees exhibited significantly higher flux in June and July than in August (p < 0.05). For small trees, the flux in the upper canopy in August was significantly lower than in other months and canopy layers (p < 0.05). However, samples taken from the lower in needles of P. crassifolia in August showed particulate flux was highest in the big tree, followed by the small tree, and then the middle tree. The maximum particulate flux of big tree (84.870 μg cm−2) and middle tree (45.498 μg cm−2) appeared in the lower needles of P. crassifolia in July. The maximum particulate flux of small tree was 34.451 μg cm−2. The minimum particulate flux level for the big tree (21.866 μg cm−2) and for the small tree (8.602 μg cm−2) were recorded in the upper needles of P. crassifolia in August, while the minimum particulate flux level for the middle tree (10.162 μg cm−2) was recorded in samples from the lower canopy in August.

Figure 3.

Flux of the particulate matter in needle of P. crassifolia. Data are mean ± SE. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences in particle flux of the same tree between different months and regions (p < 0.05). The same lowercase letters represent no significant differences within the group, while different lowercase letters represent significant differences within the group.

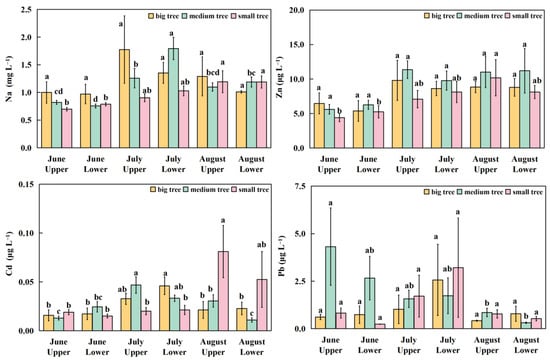

3.3. Dissolved Trace Elements in Particulate Matter

The concentrations of Na, Zn, and Cd in the particulate matter in summer of the Tianlaochi catchment presented as a trend of first increasing and then decreasing, and the concentrations of Pb in middle tree showed a decrease trend (Figure 4). The trace element with the highest concentration was Na, while Cd had the lowest concentration. The concentrations of Na in the big tree and the middle trees were highest in July, followed by August, and then June. In the small tree, the Na concentrations were highest in August, followed by July, and then June. The maximum concentration of Na recorded was 1.794 mg L−1 in samples from the lower part of middle tree of P. crassifolia in July. In contrast, the minimum concentration of Na was 0.698 mg L−1 in the upper canopy of the small tree of P. crassifolia in June. The maximum Zn concentrations in the big tree (9.797 μg L−1) and middle tree (11.345 μg L−1) were recorded in the needle samples from the upper parts of both trees in July. For big trees, no significant differences in Na, Zn, or Pb were found across months or canopy heights (p > 0.05), while Cd was significantly higher in July than in other months. In medium trees, Na was significantly higher in the lower canopy in July, Zn showed no significant variation, Cd was significantly elevated in the upper canopy in July, and Pb was higher in June and July than in August (p < 0.05). For small trees, Na and Zn were significantly higher in the upper canopy in August compared to June, Cd was also higher in the upper canopy in August than in June and July, and Pb showed no significant differences across months or canopy layers (p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Concentration of dissolved trace elements in particulate matter absorbed into needle of P. crassifolia. Data are mean ± SE. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences in dissolved trace elements in particulate matter of the same tree between different months and parts (p < 0.05). The same lowercase letters represent no significant differences within the group, while different lowercase letters represent significant differences within the group.

The concentrations of Cd in the big tree and middle trees were highest in July, followed by August, and then June. For the small tree, the concentrations of Cd were highest in August, followed by July, and then June. The maximum Cd concentrations in the big tree, middle tree and small trees were 0.046 μg L−1 (July, Lower), 0.047 μg L−1 (July, Upper), 0.081 μg L−1 (August, Upper), respectively. The maximum Pb concentrations in the big tree (2.567 μg L−1) and the small tree (3.213 μg L−1) were recorded in the samples from the lower canopy in each tree in July. And the maximum Pb concentrations in the middle tree (4.316 μg L−1) was from needles from the upper canopy in June. There was no obvious change trend for the Pb concentrations.

4. Discussion

4.1. Forest Stagnant Air Particles

Due to rapid societal and economic development in China, which has accelerated industrialization and urbanization and intensified energy consumption and other problems, air pollution has become an increasingly serious issue, and air quality has declined significantly [43,44]. Atmospheric haze caused by PM2.5, PM10, and TSP pollution can readily form secondary aerosols that contain a large number of toxic and harmful chemical components, which will pose a serious threat to human health [45,46]. Simultaneously causing significant adverse effects on the environment, including reduced atmospheric visibility, acid rain, smog, and interference with ground radiation. A recent study showed that particulate matter is a complex mixture of solid and liquid particles suspended in the air, whose physicochemical properties and biological effects vary geographically and temporally [47]. Wang et al. [48] analyzed data from 24 stations of China Atmospheric Monitoring Network, including urban, suburban, rural, and remote areas, and found that the three stations with the highest PM10, PM2.5, and PM1 concentrations were Xi’an (135.4 μg m−3, 93.6 μg m−3 and 77.0 μg m−3, respectively), Zhengzhou (131.7 μg m−3, 84.8 μg m−3 and 71.0 μg m−3, respectively), and Gucheng (127.8 μg m−3, 89.7 μg m−3 and 79.4 μg m−3, respectively). Atmospheric particulate matter has both natural and anthropogenic sources, and human activities are the main cause of its production. Atmospheric particulate matter varies with seasonal changes.

A further study showed that PM2.5 levels was high in cities in northern and western China were high, while levels in forested regions in remote areas were low [46]. Forest vegetation can reduce the concentration of air pollutants by absorbing, delaying, slowing down the transmission rate, changing the transmission direction and other ways, which is one of the ways to reduce air pollutants [49]. Fang et al. [50] studied the saturated amounts of saturated atmospheric particles of the main tree species in Shaanxi province, such as Juniperus chinensis and Populus przewalskii, and the results showed that the saturated hysteresis of TSP, PM10, PM2.5 and PM1 of leaves per unit area ranged from 4.02–36.46 μg cm−2, 1.22–27.70 μg cm−2, 0.11–3.71 μg cm−2 and 0.04–0.83 μg cm−2, respectively, and that difference between tree species varied between 9 and 30.9 times. The observed seasonal reversal in particulate retention between the two catchments—higher in Sancha during summer/autumn but higher in Tianlaochi during spring/winter—may be attributed to distinct environmental drivers. The pattern is consistent with the known regional climatic regime. Spring and winter are characterized by frequent dust events originating from southern Mongolia and Xinjiang province. The differences in particulate matter retention between the two catchments may be influenced by their distinct wind regimes. The Sancha catchment experienced a higher average wind speed (1.25 m s−1) compared to Tianlaochi (0.63 m s−1) (Table S1), which could enhance the horizontal advection and turbulent deposition of particles. Furthermore, Sancha exhibited greater seasonal variability in wind direction, notably shifting to strong westerly winds in autumn, while Tianlaochi maintained more stable south-to-southwesterly flows. This difference in exposure likely affects both the source regions of deposited particles and the microclimatic conditions governing their retention on needle surfaces. These wind characteristics, as detailed in the Study Area description, provide a physical basis for interpreting the observed spatial and seasonal patterns in particulate matter retention. Future studies incorporating continuous monitoring of precipitation, wind speed, and particle source apportionment at the catchment scale are needed to quantitatively resolve these mechanisms. In winter and spring, evergreen needle-leaved trees can sustain the retention of particulate matter more effectively. Tree species possessing denser canopies demonstrated greater effectiveness in particulate matter removal [51]. Winter heating significantly increased airborne particulate matter concentrations. Diurnal patterns differed: PM1 and PM2.5 peaked at noon and dipped morning/evening, whereas PM10 and TSP concentrations decreased gradually over time [52].

Ma et al. [53] analyzed a range of factors affecting typical roadside protection forests (oil pine, cypress, and ginkgo) in Beijing, which showed that precipitation had the greatest influence on the dust retention of the three roadside protection forests and was the most important limiting factor for the dust retention of the three roadside protection forests, and that the extreme wind speed, temperature, relative humidity, and PM10 concentration had different degrees of positive and direct influence on the dust retention in these forests. Increased humidity facilitates the coalescence of airborne particulate matter, with larger moisture droplets in the air increasing the settlement of particulate matter [54]. Studies have also shown that trees block and adsorb atmospheric particulate matter, and that the overall structure of the tree, the micromorphology of its leaf surfaces, and the degree of wetness affect this process [55]. The dust retention effect of trees is also influenced by factors such as weather conditions, seasonal variations, and the composition of the particulate matter [56]. Therefore, studies on the ability of forests to trap airborne particulate matter should not only consider meteorological factors and micromorphology, but also focus on the effects of altitudes and different vegetation types, as well as different scales (leaf, species and stand). Leaf-surface characteristics—including stomatal density, cuticular waxes, trichome density, surface roughness, and hydrophilicity—primarily govern interspecific variation in airborne particulate matter retention capacity. The thick, waxy cuticle of P. crassifolia needles may enhance the adhesion and solubilization of coarse particles (e.g., influencing Na uptake), while stomatal regulation could govern the internalization of fine, metal-rich aerosols (e.g., Cd). These unmeasured traits offer a plausible physiological framework for the observed elemental accumulation patterns. Consequently, under identical environmental conditions, differences in particulate matter capture between tree species are determined by three key foliar traits: micromorphological structure, surface roughness, and moisture content [57].

Dzierżanowski et al. [58] studied the retention of particulate matter in the leaves of four broad-leaved tree species in highly polluted areas in Poland. Different pore size filters were used to distinguish between particulate matter with different particle sizes. The study found that the adhesion of particulate matter with a particle size of 10–100 μm on the surface of the leaves was 13–21 μg cm−2, while for particulate matter with a particle size of 2.5–10 μm the values were 0.6–2.5 μg cm−2. Xie et al. [59] showed that the amount of PM2.5, PM10 and TSP in Picea wilsonii trees reached a maximum of 0.1222 g m−2, 0.2996 g m−2, and 1.3566 g m−2, respectively. The current study showed that the particulate flux ranges of big, medium and small trees were 21.866–84.870 μg cm−2, 10.162–45.498 μg cm−2 and 8.602–34.451 μg cm−2, respectively. Overall, the adsorption of particulate matter is higher than the middle and small trees, which may be because the trees began to resist the erosion of the sand earlier and reduce the concentration of particulate matter in the air. This finding is consistent with the results of Lü et al. [60], which showed that trees with a larger the tree crown and more complex the canopy structure had a greater particulate matter adsorption capacity and a more stabilizing effect. With the end of the growing season and the rainy season, the stomatal closure of P. crassifolia needles also changed accordingly. Specific performance in this study is that the absorption of particulate matter in big tree and middle tree rise first and then decrease with the change of time, while small tree showed a decreasing trend. In addition, leaf area dominated particulate matter accumulation compared to leaf size and morphology. Canopy density, by altering air turbulence, promotes dry particulate matter deposition. Studies show species with higher leaf area index (LAI) and smaller leaves adsorb particulate matter most effectively [61]. Therefore, this study shows that P. crassifolia of different sizes vary in their particulate matter absorption capacities and that larger trees can absorb greater amounts of airborne particulate matter.

4.2. Trace Elements in Particulate Matter on Needles

Atmospheric particulate matter can contain a large number of trace elements, which can enter the human body through a variety of pathways and pose a threat to human health. This is currently a widespread environmental problem in China and many other countries. Many studies on trace elements in atmospheric particulate matter have focused on trace elements in atmospheric deposition, which are tested and analyzed after collecting dry and wet atmospheric deposition by certain means. For example, Cable and Deng [62] analyzed 22 elements in rain and snow samples from the Detroit metropolitan area and showed that the levels of the trace elements ranged from ~0.03 to ~1.8 × 103 μg kg−1. Wu et al. [63] conducted a study on the fluxes and sources of trace elements in wet and dry deposition in Daya Bay, in the South China Sea, and found that the wet deposition fluxes of trace elements were higher than the dry deposition fluxes due to the high rainfall frequency in that area, and that wet deposition was highest in the summer and lowest in the winter. Regarding plant retention of airborne particulate matter, the characterization of atmospheric particulate matter adsorbed and retained on plant foliage as a biomonitoring tool and bioindicationor is gradually becoming an important research topic in the field of atmospheric environment science [64]. While root uptake from soil is a major pathway for trace elements, foliar absorption represents a significant complementary route, particularly in areas with high atmospheric deposition. Trace elements contained in particulate matter deposited on leaf surfaces can enter the interior tissues primarily through stomata, especially for elements with high solubility or under conducive environmental conditions (e.g., high humidity). This pathway is environmentally most significant at local to regional scales where atmospheric inputs are elevated, such as in arid, dust-influenced regions like the Qilian Mountains. Therefore, the absorption of trace elements by vegetation is of great significance for the control of air pollution control.

The elements Na, Mn, Al, and Fe are unique to the Earth’s crust [65], while Cu, Cr, Pb, and Zn are produced by human sources [66,67]. These particulate pollutants can affect the physiology of vegetation. For example, during photosynthesis and respiration, particulate particles can also be absorbed through the stomata [49], leading to a decrease in chlorophyll content. The inhalation of toxic elements including Cd, Zn, Cr, Pb, and Ni can also harm human health [68,69]. Both Na and Zn are needed for the growth and development of the human body; however, Na intake may affect the acid-base balance in the body, causing diseases such as hypertension [70]. In addition, excessive Zn can cause poisoning, which can also affect human health. In this study, P. crassifolia needles absorb more Na in July and August, while Zn concentrations increased with the change of time. We hypothesize that these patterns may be attributed to seasonal shifts in deposition sources: the Na peak coincides with the rainy season, potentially reflecting enhanced soluble dust input, whereas the rise in Zn could be linked to increased atmospheric particulate loading during drier periods. In addition, these months are the peak of the plant growth season, and in P. crassifolia, the absorption capacity of plant leaves to air particles is enhanced. Waste incineration and industrial activities are the main sources of Zn, while Na mainly comes from natural sources. In the case of Pb and Cd, both are toxic metals that are harmful to humans. Pb leads to renal ailments and nervous disorders [71,72], and Cd causing gastrointestinal diseases, emphysema, and various other cardiopulmonary ailments [73]. This study showed that Pb absorption peaked in the middle tree in June, while overall, absorption by P. crassifolia needles was highest in July, followed by June, and then August. In comparison, Cd absorption was highest in August, followed by July, and then June. Emissions from industry and combustion are the main sources of Pb in dust [74]. The concentration of Cd is mainly influenced by human activities [75], and Cd is the primary pollutant in the city of Changsha in Hunan province [76]. The region surrounding the study area is rich in mineral resources and relies heavily on coal combustion for winter heating, along with biomass burning in rural areas. These local and regional anthropogenic activities—encompassing industrial emissions, transportation, and seasonal residential burning—are likely important sources for trace elements such as Zn, Pb, and Cd detected in the particulate matter. The seasonal patterns in elemental concentrations may thus reflect a combination of localized emissions and medium-range atmospheric transport influenced by prevailing winds [42]. The elements may be transported long-range via atmospheric circulation and deposited in high-elevation regions. Our findings on trace elements in Picea crassifolia can be further contextualized. Similar to the differential accumulation observed among species (e.g., P. abies, Q. robur), the uptake pathways and resultant foliar concentrations are strongly influenced by species-specific traits (e.g., needle morphology enhancing surface deposition) and proximity to emission sources. The spatial patterns—where some elements increase with distance linked to finer particles—highlight that foliar absorption serves as a direct indicator of atmospheric deposition dynamics. This underscores the role of dominant conifers like P. crassifolia not only in capturing particulate matter but also in bio-monitoring trace element inputs in protected, yet deposition-impacted, mountain ecosystems [77].

The source of this study area is located within the Qilian Mountains, which are far from the industrial zone, and experience a relatively low degree of human interference. However, July and August represent the peak season for undertaking monitoring surveys, during which there is more human activity in the study area, which may cause fluctuations in atmospheric Pb and Cd in the air that are easily affected by human activities and life behavior. The significance of studying dissolved trace elements in atmospheric particulate matter is as follows: (1) From an environmental point of view, forests in different regions hold different trace elements, and research can clarify the role of forests in purifying the air and reducing harmful trace elements, so as to provide a basis for precise management of regional air pollution. (2) For ecosystem studies, trace elements have an important impact on the cycling of matter and energy flow in forest ecosystems. Studying the differences will enable us to know how forest ecosystems in different regions are affected by inputs of trace elements from airborne particulate matter, so that we can understand the processes such as the accumulation and transport of these elements in ecosystems, and assess their potential impacts on forest organisms (e.g., tree growth, understory vegetation, animals). (3) Considered at the human health level, trace elements in airborne particulate matter can affect human health. Studying these differences can help us better understand the health benefits of different regional populations as a result of air quality regulation by forests, and provide references for urban greening planning, etc., so that forests can better protect human health. Therefore, it can be seen from this that the P. crassifolia forest in the Qilian Mountains can effectively intercept air particulate matter and reduce the content of air pollutants, benefiting human health, and enhancing its ecological service function.

4.3. Novelties, Limitations, and Environmental Implications

The novelties of this study are as follows: (1) two different methods were used to comparatively analyze airborne particulate matter retention by P. crassifolia needles, and (2) the concentration of dissolved trace elements in particulate matter was analyzed from both nutrient and toxicity perspectives. The limitations of this study are that it was restricted to two small catchments in the Qilian Mountains and a single tree species (P. crassifolia). The site-specific conditions of the two studied catchments, including their distinct altitudes, microclimates, and limited sample size, may constrain the direct extrapolation of the results to other areas within the Qilian Mountains. Future research should incorporate a broader range of sites and larger sample sizes to enhance the generalizability of the findings. By comparing the capacity of P. crassifolia needles in two typical catchments to hold airborne particulate matter, this study clarifies the efficiency of forests in different areas of the Qilian Mountains to hold particulate matter, which can be used for the local rational planning of the distribution of plantations to maximise the function of forests in purifying the air. For example, in the poor air quality, particulate matter pollution in the region, targeted to increase the area of forest vegetation, directly reduce the particulate matter content in the air, thereby improving air quality. In addition, through the study of dissolved trace elements in particulate matter, pollution sources can be accurately identified and targeted measures can be taken in time to reduce air pollution, which can also help to assess the potential risk of air quality to human health. In addition, the research results can provide key parameters for environmental modelling, and the research data can be used to formulate more reasonable environmental quality standards to promote air quality improvement. Based directly on our findings, we recommend: (1) prioritizing the conservation and expansion of mature P. crassifolia stands, given their significantly higher particulate retention capacity; (2) tailoring afforestation strategies to local altitude and seasonal dust deposition patterns to optimize placement of protective forest belts; and (3) establishing a bio-monitoring network using P. crassifolia needles to track trace element pollution sources and inform targeted emission controls in the region.

5. Conclusions

Our study quantified the particulate matter retention capacity of P. crassifolia forests in the Qilian Mountains. Key findings indicate the following: (1) Particulate matter retention in the Tianlaochi catchment was significantly lower than in the Sancha catchment during summer and autumn. (2) Big trees exhibited the highest particulate matter adsorption capacity (21.866–84.870 μg cm−2), exceeding that of middle and small trees. (3) Elemental analysis revealed Na as the dominant metal in adsorbed particulate matter (0.698–1.794 mg L−1), followed by Zn, Pb, and Cd. (4) Seasonal maxima for needle-adsorbed metals occurred differentially—dissolved Na and Zn peaked in July (middle tree), Cd in August (small tree), and Pb in June (middle tree). These results establish baseline data that highlight the significant retention potential of P. crassifolia for airborne particles. This work provides a scientific basis for evaluating the species’ role in regional particulate matter deposition within forest ecosystems. Future studies should integrate modeling with field measurements to assess whole-forest particulate matter dynamics across the Qilian Mountains.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f17010140/s1.

Author Contributions

W.Z.: Writing—original draft, Software, Formal analysis, Data curation; J.C.: Supervision, Investigation; Y.Z.: Supervision, Investigation; W.L.: Software; Z.Y.: Investigation; F.Z.: Investigation, Formal analysis; H.H.: Methodology, Formal analysis, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Natural Resources Survey and Monitoring Project of Central Finance (No.7, 2023), Provincial Financial Forestry and Grassland Project Fund of the Forestry and Grassland Bureau of Gansu Province (No.936, 2021), Gansu Province Forestry and Grassland Science and Technology Plan Project (2021kj072), and the Natural Science Foundation of Gansu Province, China (24JRRG012).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Chen, X.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, W.; Li, Z. Comparison between dust and haze aerosol properties of the 2015 Spring in Beijing using ground-based sun photometer and lidar. Opt. Optoelectron. Sens. Imaging Technol. 2015, 9674, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.P.; Wang, Y.S. Atmospheric wet and dry deposition of trace elements at 10 sites in Northern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, J.A.; Nel, A.E. Particulate matter and atherosclerosis: Role of particle size, composition and oxidative stress. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2009, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cai, J.; Chen, R.; Sera, F.; Guo, Y.; Tong, S.; Li, S.; Lavigne, E.; Correa, P.M.; Ortega, N.V.; et al. Coarse particulate air pollution and daily mortality: A global study in 205 cities. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Ambient (Outdoor) Air Pollution; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Zhao, H.; Du, R.; Guo, L. Seasonal variation of microbial activity in atmospheric particulate matter and its lagging response to environmental factors. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 358, 121359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Mandal, M.; Popek, R. Decoding leaf micro- and macro-morphology: A path to effective particulate matter phytoremediation. Int. J. Phytorem. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, K.P.; Freer-Smith, P.H.; Taylor, G. Effective tree species for local air quality management. J. Arboric. 2000, 26, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- El-Khatib, A.A.; El-Rahman, A.M.; Elsheikh, O.M. Leaf geometric design of urban trees: Potentiality to capture airborne particle pollutants. J. Environ. Stud. 2011, 7, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H.J.; Yook, S.J.; Ahn, K.H. Experimental investigation of submicron and ultrafine soot particle removal by tree leaves. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 6987–6994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, K.P.; Freer-Smith, P.H.; Taylor, G. Urban woodlands: Their role in reducing the effects of particulate pollution. Environ. Pollut. 1998, 99, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freer-Smith, P.H.; El-khatib, A.A.; Taylor, G. Capture of particulate pollution by trees: A comparison of species typical of semi-arid areas (Ficus nitida and Eucalyptus globulus) with European and North American species. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2004, 55, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Bodine, A.; Hoehn, R. Modeled PM2.5 removal by trees in ten US cities and associated health effects. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 178, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Du, J.; Huang, T.; Zhang, L.; Gao, H.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, J. Atmospheric removal of PM2.5 by man-made Three Northern Regions Shelter Forest in Northern China estimated using satellite retrieved PM2.5 concentration. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 593, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Mandal, M.; Przybysz, A.; Haynes, A.; Robinson, S.A.; Sarkar, A.; Popek, R. Phytoremediating the air down under: Evaluating airborne particulate matter accumulation by 12 plant species in Australia. Ecol. Res. 2025, 40, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, A.; Zhang, J.Q.; Zhang, H.J.; Dong, R.Z. Research progress on the influencing factors and response mechanisms of plant adsorption of atmospheric particulate matter. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 35, 2013–2014. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottle, A.; Sène, E.H. Forest functions related to protection and environmental conservation. Unasylva 1997, 48, 30–37. [Google Scholar]

- Núñez, D.; Nahuelhual, L.; Oyarzún, C. Forests and water: The value of native temperate forests in supplying water for human consumption. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 58, 606–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlan, T. Forest resource management and forest biodiversity conservation in Peninsular Malaysia. In Proceedings of the National Conference on the Management and Conservation of Forest Biodiversity in Malaysia, Putrajaya, Malaysia, 20–21 March 2007; pp. 1–13. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122640/records/647473a979cbb2c2c1b363a9 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, F.; Wang, B.; Guo, H.; Lu, S.; Wei, W.; Hu, W.; Chen, L. Study on Forest Ecosystem Service Function in China; China Science Publishing Media Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X.; Lu, G.; Zhou, K.; Liu, H.; Dang, Z. Phytodecontamination of atmosphere chemical pollution: A review. Energy Ecol. Environ. 2007, 16, 1546–1550. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hong, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. Particle-retaining characteristics of six tree species and their relations with micro-configurations of leaf epidermis. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2017, 39, 70–77. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Niu, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Atmospheric particle retaining function of common deciduous tree species leaves in Beijing. Environ. Sci. 2015, 36, 2005–2009. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Tang, L.; Hu, J. Study on the dust catching property of the several evergreen conifers in Huhhot. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2009, 25, 62–65. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Setiawan, G.D.; Przybysz, A.; Treesubsuntorn, C.; Popek, R. Effect of simulated rain and rain frequency on particulate matter re-accumulation in roadside climbers Parthenocissus quinquefolia. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 382, 126649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popek, R.; Przybysz, A. Precipitation plays a key role in the processes of accumulation, retention and re-suspension of particulate matter on Betula pendula, Tilia cordata and Quercus robur foliage. Desalin. Water Treat. 2022, 275, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunekreef, B.; Holgate, S.T. Air pollution and health. Lancet 2002, 360, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Singh, G. Human health risk assessment in PM10-bound trace elements, seasonal patterns, and source apportionment study in a critically polluted coking coalfield area of India. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2022, 18, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, A.; Dockery, D.W.; Muller, J.E.; Mittleman, M.A. Increased particulate air pollution and the triggering of myocardial infarction. Circulation 2001, 103, 2810–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D.; Rajagopalan, S.; Pope, C.A., III; Brook, J.R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Diez-Roux, A.V.; Holguin, F.; Hong, Y.; Luepker, R.V.; Mittleman, M.A.; et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010, 121, 2331–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, K.A.; Hopke, P.K.; Utell, M.J.; Kane, C.; Thurston, S.W.; Ling, F.S.; Chalupa, D.; Rich, D.Q. Triggering of ST-elevation myocardial infarction by ambient wood smoke and other particulate and gaseous pollutants. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2017, 27, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santibáñez-Andrade, M.; Sánchez-Pérez, Y.; Chirino, Y.I.; Morales-Bárcenas, R.; Quintana-Belmares, R.; García-Cuellar, C.M. Particulate matter (PM10) destabilizes mitotic spindle through downregulation of SETD2 in A549 lung cancer cells. Chemosphere 2022, 295, 133900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzdek, B.R.; Pennington, M.R.; Johnston, M.V. Single particle chemical analysis of ambient ultrafine aerosol: A review. J. Aerosol. Sci. 2012, 52, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, P.; Delgado-Saborit, J.M.; Harrison, R.M. A review of chemical and physical characterisation of atmospheric metallic nanoparticles. Atmos. Environ. 2014, 94, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, I.L.; Teixeira, E.C.; Dotto, G.L.; Pinto, D.; Yang, C.; Silva, L.F.O. Geochemical study of submicron particulate matter (PM1) in a metropolitan area. Geosci. Front. 2022, 13, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, F.; Chang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Nan, Z.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y. Influence of atmospheric trace elements wet deposition on soils and vegetation of Qilian Mountain forests, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Xu, J.; Kang, S.; Ren, J.; Cui, X. Trajectory analysis of atmospheric transport of particles in Laohugou area, Western Qilian Mountains. Arid. Zone Res. 2020, 37, 671–679. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yu, G. The changing characteristics of soluble ions in PM2.5 in summer over Laohugou region in the Qilian Mountains. J. Glaciol. Geocryol. 2017, 39, 1022–1028. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Qin, D.; Kang, S.; Ren, J.; Chen, J.; Cui, X.; Du, Z.; Qin, X. Physicochemical characteristics and sources of atmospheric dust deposition in snow packs on the glaciers of western Qilian Mountains, China. Tellus B 2014, 66, 20956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.Z.; Mei, F.; Zhang, X.H.; Zhao, W.H.; Zhai, L.X.; Zhong, M.; Hou, S.G. Impact of anthropogenic aerosol transport on cloud condensation nuclei activity during summertime in Qilian Mountain, in the northern Tibetan Plateau. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2024, 129, e2023JD040519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hao, H.; Zhao, C.; Zang, F.; An, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, H. Effects of rainfall and temperature on river runoff during growing season in Tianlaochi catchment in the upper reaches of Heihe River Basin. Res. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 29, 263–269. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, F.; Wang, H.; Zhao, C.; Nan, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, J.; Li, N. Atmospheric wet deposition of trace elements to forest ecosystem of the Qilian Mountains, northwest China. Catena 2021, 197, 104966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wen, Z. Review and challenges of policies of environmental protection and sustainable development in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 88, 1249–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Zhou, H. Impact of China’s economic growth and energy consumption structure on atmospheric pollutants: Based on a panel threshold model. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 236, 117694. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, D.; Skiba, U.; Nemitz, E.; Choubedar, F.; Branford, D.; Donovan, R.; Rowland, P. Measuring aerosol and heavy metal deposition on urban woodland and grass using inventories of 210Pb and metal concentrations in soil. Water Air Soil Pollut. Focus 2004, 4, 483–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Tan, J.; Zhao, Q.; Du, Z.; He, K.; Ma, Y.; Duan, F.; Chen, G.; Zhao, Q. Characteristics of PM2.5 speciation in representative megacities and across China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2011, 11, 5207–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, K.; Greenbaum, D.S.; Shaikh, R.; van Erp, A.M.; Russell, A.G. Particulate matter components, sources, and health: Systematic approaches to testing effects. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2015, 6, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, X.; Che, H.; Li, Y. Spatial and temporal variations of the concentrations of PM10, PM2.5 and PM1 in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 2015, 15, 3585–13598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Peng, Y.; Liao, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, G. A review of the relationship between forest vegetation and atmospheric particulate matter. Plant Sci. J. 2017, 35, 790–796. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Wang, B.; Niu, X. Atmospheric particles-capturing capability of main afforestation tree species in Central Shaanxi Plain. Chin. J. Ecol. 2015, 34, 1516–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, M.J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Park, S.; Lim, Y.; Kim, J.E.; Baek, S.G.; Seo, S.M.; Kim, K.N.; Woo, S.Y. The removal efficiencies of several temperate tree species at adsorbing airborne particulate matter in urban forests and roadsides. Forests 2019, 10, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Sun, C.; Mu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Y.; Qiu, L.; Gao, T. Differences in airborne particulate matter concentration in urban green spaces with different spatial structures in Xi’an, China. Forests 2022, 13, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wang, C.; Du, W.; Liu, W. Spatio-temporal distribution and impact analysis on dust-retention effect of typical road protection forests in Beijing. For. Res. 2018, 31, 110–117. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruijgrok, W.; Tieben, H.; Eisinga, P. The dry deposition of particles to a forest canopy: A comparison of model and experimental results. Atmos. Environ. 1997, 31, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Tripathi, B.D. Seasonal variation of leaf dust accumulation and pigment content in plant species exposed to urban particulates pollution. J. Environ. Qual. 2008, 37, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ha, S.; Liu, L.; Gao, S. Effects of weather condition in spring on particulates density on conifers leaves in Beijing. Chin. J. Ecol. 2006, 25, 998–1002. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallis, M.; Taylor, G.; Sinnett, D.; Freer-Smith, P. Estimating the removal of atmospheric particulate pollution by the urban tree canopy of London, under current and future environments. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2011, 103, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierżanowski, K.; Popek, R.; Gawrońska, H.; Sæbø, A.; Gawroński, S.W. Deposition of particulate matter of different size fractions on leaf surfaces and in waxes of urban forest species. Int. J. Phytorem. 2011, 13, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhao, M.; He, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, J. Dust-retaining ability of Picea wilsonii and Pinus tabuliformis forests with different diameter classes. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2020, 35, 17–24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lü, L.; Li, H.; Yang, J. The temporal-spatial variation characteristics and influencing factors of absorbing air par-ticulate matters by plants: A review. Chin. Afr. J. Ecol. 2016, 35, 524–533. [Google Scholar]

- Weerakkody, U.; Dover, J.W.; Mitchell, P.; Reiling, K. Particulate matter pollution capture by leaves of seventeen living wall species with special reference to rail-traffic at a metropolitan station. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, E.; Deng, Y. Trace elements in atmospheric wet precipitation in Detroit metropolitan area: Levels and possible sources. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ni, Z.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Z.; Huang, X. Atmospheric deposition of trace elements to Daya Bay, South China Sea: Fluxes and sources. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 127, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Ma, K.; Bao, L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, D. Distribution of particle matters and contamination of heavy metals in the foliar dust of Sophora japonica in parks and their neighboring roads in Beijing. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2013, 33, 154–162. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inerb, M.; Phairuang, W.; Paluang, P.; Hata, M.; Furuuchi, M.; Wangpakapattanawong, P. Carbon and Trace element compositions of Total Suspended Particles (TSP) and Nanoparticles (PM0.1) in ambient air of Southern Thailand and Characterization of Their Sources. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alias, N.F.; Khan, M.F.; Sairi, N.A.; Zain, S.M.; Suradi, H.; Rahim, H.A.; Banerjee, T.; Bari, M.A.; Othman, M.; Latif, M.T. Characteristics, emission sources, and risk factors of heavy metals in PM2.5 from southern Malaysia. ACS Earth Space Chem. 2020, 4, 1309–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahari, N.; Muda, K.; Latif, M.T.; Hussein, N. Studies of atmospheric PM2.5 and its inorganic water soluble ions and trace elements around southeast Asia: A Review. Asia-Pac. J. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 57, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Jia, C.; Yu, H.; Xu, H.; Ji, D.; Wang, C.; Xiao, H.; He, J. Characteristics, sources, and health risks of PM2.5-bound trace elements in representative areas of Northern Zhejiang Province, China. Chemosphere 2021, 272, 129632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phairuang, W.; Inerb, M.; Hata, M.; Furuuchi, M. Characteristics of trace elements bound to ambient nanoparticles (PM0.1) and a health risk assessment in southern Thailand. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 425, 127986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacheva, N.; Eliseeva, T. Sodium (Na)–Body & Health Importance+ Top 30 Sources. J. Healthy Nutr. Diet. 2022, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, K.; Flora, S.J.S. Strategies for safe and effective therapeutic measures for chronic arsenic and lead poisoning. J. Occup. Health 2005, 47, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora, G.; Gupta, D.; Tiwari, A. Toxicity of lead: A review with recent updates. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2012, 5, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suhani, I.; Sahab, S.; Srivastava, V.; Singh, R.P. Impact of cadmium pollution on food safety and human health. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, C.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Z.; Jia, J.; Bao, X. Heavy metals and lead isotopes in soils, road dust and leafy vegetables and health risks via vegetable consumption in the industrial areas of Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, P.; Zhao, X.; Yin, B.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Yu, H.; Yang, W.; Wang, X. Distribution Characteristics and Source Apportionment of Elements Bonded with PM2.5 and PM10 in Linyi. Environ. Sci. 2020, 41, 2036–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Li, F.; Zeng, G.; Zeng, G.; Liu, W.; Huang, X.; Xiao, Z.; Wu, H.; Gu, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Integrating hierarchical bioavailability and population distribution into potential eco-risk assessment of heavy metals in road dust: A case study in Xiandao District, Changsha city, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popek, R.; Przybysz, A.; Łukowski, A.; Baranowska, M.; Bułaj, B.; Hauke–Kowalska, M.; Jagiełło, R.; Korzeniewicz, R.; Moniuszkoa, H.; Robakowski, P.; et al. Shields against pollution: Phytoremediation and impact of particulate matter on trees at Wigry National Park, Poland. Int. J. Phytorem. 2025, 27, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.