Abstract

To date, there has been a noticeable lack of a systematic and structured approach to the development of forest therapy tourism. This study addresses this problem by introducing a forest tourism attractiveness model and an evidence-based framework for the conceptual development of Forest Climatic Spa Resorts. Based on an attributive theory approach, a comprehensive set of forest tourism attractiveness attributes is defined, a model of forest tourism attractiveness is developed, and theoretical and conceptual foundations to support the criteria for the development of Forest Climatic Spa Resorts are presented. This research contributes to the ongoing discourse on sustainable tourism practices and emphasises the role of forest environments in promoting health and well-being in therapeutic tourism activities. Ultimately, our findings offer valuable insights for policymakers, tourism developers, and practitioners in the field of forest therapy tourism, providing a foundation for future initiatives aimed at enhancing the appeal and sustainability of forest-based tourism experiences.

1. Introduction

Attractions are fundamental building blocks in the development of the tourism industry [1], representing tourists’ main motivation for visiting a destination [2]. However, the current literature on tourists’ use of forests lacks a definition of the attractiveness of forests to tourists. The literature also reveals a considerable lack of a systematic approach to the development of a structured and standardised framework for the sustainable development, implementation, and evaluation of forest therapy tourism (hereinafter referred to as FTT) as a specific form of tourism. Only in recent years studies have focused more on forest tourism activities [3,4,5,6,7,8]. Even though forest tourism activities have been increasing for decades [9,10], no foundation for further development has been established or thoroughly researched. Very few studies, if any, have examined forest tourism as a system or forests as a specific type of destination. Additionally, all findings related to tourism or recreational activities in forests have demonstrated that the natural and tourism potential of forests exceeds the economic value of timber production, as stated in the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment [11]. For example, a study in Sweden thirty years ago showed that tourists attribute significant value to forest attributes. As noted by Bostedt and Mattsson [12] (pp. 671–680), the results suggest that the economic value of forest attributes could be increased if current forest management practices were changed. The outcomes of such studies are recommended as tools for cost–benefit analyses and for informing investment decisions in forest development; however, they do not represent a well-founded and comprehensively structured conceptual framework that would enable the systematic and sustainable development of forest therapy tourism activities. Additionally, very few studies have examined forest tourism (hereinafter referred to as FT) from a product-oriented perspective, even though every tourist activity inherently involves a commercial transaction between the tourist and the service provider, and it appears across many disciplines [13,14].

To address the above and to provide a comprehensive understanding of forest therapy tourism attractiveness, research questions have been formulated. The conceptual framework of the research design is defined by individual phases, each of which has specific research objectives and tools, which are explained in detail in the Section 3. To take into account the above as well as to support biodiversity conservation while aligning with the measures outlined in the EU Forest Strategy for 2030 [9]—particularly its emphasis on “promoting alternative forest industries, such as ecotourism”—it is essential to establish well-structured recommendations. These guidelines should provide a sustainable framework for developing FT activities, as well as for climate resorts. Herein, this study aimed to highlight the specific methodological tools as appropriate for addressing the research problem. To ensure clarity, we have structured the research design, methodology, and materials in this article to explicitly demonstrate the role of each activity or study conducted. Defining the roles of different theories also helped to clarify how the study’s contribution should be evaluated [15]. Consequently, when we describe our research design (see the Section 3), we present seven studies on a timeline, structured as follows: (1) defining the research objectives, (2) outlining key qualitative and quantitative methods and tools, and (3) providing a conceptual framework of the research design. With this structure, we aimed to summarise and integrate current knowledge while outlining the conceptual domain of a new phenomenon: the justification of necessary and sufficient criteria for defining a Forest Climatic Spa Resort.

2. Literature Review

To appropriately address FT and FTT activities, it is essential to adopt an ecosystem services-based approach and to conceptualise the forest ecosystem as a natural capital resource [16]. The sustainable utilisation of ecosystem services—particularly the socio-cultural values of forests for tourism purposes—requires an in-depth and, above all, interdisciplinary examination of forest tourism attractiveness [14]. Therefore, in the following sections, the theoretical foundations for a sustainable approach to identifying the starting points of FT are presented, with a particular focus on forest therapy tourism. As identifying the attributes and factors of forest tourism attractiveness is a key contribution to further research, the theoretical background is grounded in the attributive approach [17,18,19,20]. According to Pike [21,22], Pike and Page [23], Wu et al. [24], Kim and Park [25], and Dwyer [26,27], the attributive model is mainly based on natural attributes. Applying the attributive theory, this study aimed to define the tourist attractiveness of forests and establish the necessary conditions for implementing therapeutic and wellness activities in a particular forest area and to design a foundational framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts in a certain forest area suitable for Climatic Resort development. In this case, the forest is regarded as a specific type of destination that, in addition to aligning with the key concept of sustainability, also satisfies the climatic conditions and geomorphological criteria of a particular forest area and bases its activities on a predefined carrying capacity.

2.1. Tourist Attractiveness of Forests—An Attributive Theory Approach

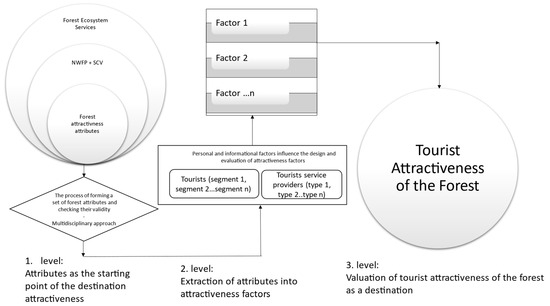

The attribution theory, developed by Austrian psychologist Fritz Heider in 1958, seeks to explain consumer satisfaction and purchasing behaviour by analysing how individuals attribute causes to observed outcomes, particularly in relation to the perceived attributes of a product or service [28]. Building on this theoretical foundation, Lancaster [29] introduced the concept that consumer demand is derived not from the product per se but from the attributes it embodies. Weiner [30] extended these ideas with a three-dimensional attributional model that further explains consumer decision-making by stating that attribution is a three-stage process involving a locus of causality, stability, and controllability [14]. The rationale behind attributive theory is to recognise that people’s decisions and behaviour can be explained by attributes. Typologically, FT is considered tourism in the natural environment, and, as a tourist destination, the forest is considered a natural destination whose fundamental competitive advantages are based on natural attributes [13]. Furthermore, the principal attributes of a particular destination, such as local, natural resources, cultural heritage, accessibility, and similar, represent a competitive and distinguishing advantage of the destination on which the sales strategy should be based, while the attributes of tourist infrastructure represent its added value [27]. All these natural features and benefits, called forest attributes, can serve as the main building blocks of forest tourism attractiveness. Therefore, when assessing the tourist attractiveness of the forest as a natural environment, the attributive model should be applied. Basic tourist resources include natural, cultural, and social resources and natural and derived attractions [31]. Secondary tourist resources include tourist services (restaurants and accommodation services, travel agency services, additional services, and so on). Supporting tourist resources include infrastructure [32], while Leiper’s [33] model of an open tourist system considers free time and industries that support an individual destination to be tourist resources as well. Almost all tourist resources have to be treated as limited and perhaps non-renewable: they have to be maintained and protected and take into account the carrying capacity of a given tourist area [34,35]. Additionally, the basic concept underlying the use of forests as tourist resources advocates sustainability, protecting the ecosystem and forest resources while deriving socio-cultural values and benefits from the forest. A forest is regarded as the only ecosystem type among basic ecosystems (land, towns, seas, islands, mountains, polar areas, coastal areas, land waters, cultivated land) that ensures the use of all ecosystem services (hereinafter referred to as ESs) [10], several of which may be included in tourist activities. The tourist function of the forest provides tourist resources or benefits, such as natural beauty, educational benefits, and recreational services [36]. Among these, the aesthetic pleasures and healing effects that the forest offers to its visitors are included. This means that the forest provides more ESs than just its traditional aesthetic functions when visitors observe its natural beauty. The use of forests for maintaining physical and mental health and supporting the immune system is also considered to provide socio-cultural value [37,38,39]. Therefore, when defining a forest tourism attractiveness model, it is essential to start with ecosystem services (ESs), as presented in Figure 1. Non-wood forest products (hereinafter referred to as NWFPs) and the socio-cultural values of the forest (hereinafter referred to as SCVs) form the core of the tourist attractiveness of the forest. Conceptually, the forest attributes in the model are shown in an Euler diagram where the smaller circle indicates a subset of the bigger one. It is evident from these circles that the basis is forest ecosystem services which represent natural capital for numerous economic activities. A subset of ecosystem forest services is non-wood forest products and forest SCVs, which can serve as the basis for defining those attributes of the forest that form its tourist attractiveness. They are offered by the forest in situ and serve to meet human needs [11] (p. 7), [40] (p. 28). A model of the tourist attractiveness of the forest, shown in Figure 1, was created on the basis of the described models and attractiveness theory. The hierarchy described in [19,41,42] was applied to structure the levels of the model. All the listed research first deals with the attributes that define the attractiveness of the subject concerned, and then those attributes are extracted as factors of attractiveness. The basic or first level in the model concerns the destination’s attractiveness components. Conceptually, the forest attributes in the model are shown in an Euler–Venn diagram, where the smaller circle indicates a subset of the bigger category. It is evident from these circles that the basis of forest attractiveness is forest ecosystem services that represent natural capital for numerous economic activities. A subset of ecosystem forest services is NWFPs and forest SCVs, which can serve as the basis for identifying those attributes of the forest that define its tourist attractiveness. At the second level, the factors of forest attractiveness are presented. They are usually extracted by analysing the set of attributes using an analytical method, such as descriptive analysis or CatPac text analysis [43], or a quantitative method, such as factor analysis [27,44,45,46], Cronbach’s alpha test, or t-test. The third level is the general tourist attractiveness of the forest and represents the result of valuation, which we believe should take place at the second level and originates from the attributive approach. The impact of individual factors on tourist demand depends on the individual tourist segment or the type of provider.

Figure 1.

Attributive model of tourist attractiveness of the forest. Source: [47].

Not every naturally attractive resource is suitable for valorisation as a tourist attraction.

As a tourist resource and natural capital, the forest is one of the most important systems on our planet, as it includes human, financial, living, and non-living resources that can be used for different purposes, meet human needs, and improve the quality of life [47]. Therefore, the existence and sustainable development of all resources on Earth must be ensured [48]. By taking into account certain recommended principles, we also aim to distinguish the meaning of natural resources from that of natural attractions and point out that this research only focuses on attributes that also meet the criteria of the production dimension [49], stability [50,51] (p. 1091), and the presence of economic indicators [52], since the tourism industry consists of profit-making activities and must therefore consider and carefully plan to ensure its economic value. A tourist resource can only acquire market value and become a tourist attraction with a certain market value through the process of valorisation (by tourists or visitors) [53,54]. However, not every naturally attractive resource meets the criteria needed to become a tourist attraction. Specifically, not every attractive forest feature or popular forest activity is appropriate or commercially viable as a tourist activity or product. Only by adhering to sustainability principles can forest tourism attractions generate revenue from services that are essential for the sustainable development of tourism within a given geographical area. This means that the valorisation of FT’s potential must be conducted in accordance with key criteria for sustainable business operations. This aligns with the “three-pillar” concept, which defines sustainable tourism as being rooted in economic, socio-cultural, and environmental dimensions, as outlined by the World Tourism Organization [55] in its definition of sustainable tourism and integrated into tourism strategies worldwide [56]. This approach is also critical for the effective positioning of forest areas as specific tourism destinations and for a deeper conceptualisation of forest therapy (hereinafter referred to as FT). FT should be presented as a type of tourism with certain specifications, which have not been established despite the fact that tourist activities have long been carried out in forests. A certain forest area can only be considered to have an established FT system when its tourist function is managed and monitored and when the tourist forest products are marketed with at least some interaction among the stakeholders in the local environment and the destination manager.

2.2. Designing Foundational Framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts

Numerous activities are carried out in the forest, including tourist and leisure activities, aimed at enjoyment in green and unpolluted nature [57]. Tourist use of the forest has great potential, as stated in an important European development document [58]. They encourage the use of forest ESs, including the NWFPs and SCVs of the forest, for tourist purposes [59,60,61]. The estimated growth in the added value of new markets for NWFPs, such as mushrooms, berries, and clean water, and services, such as recreation and tourism, is extremely high [9]. Since 2010, nature-based tourism has been gaining increasing importance [62,63,64], as spending time in natural environments has become an increasingly sought-after form of leisure, health promotion, and well-being. Within this context, FT has emerged as a new and specific type of tourism that combines the SCVs and NWFPs of forests [65]. Of particular interest are the climatically conditioned attributes of the forest, which provide beneficial or even healing effects. This includes the use of (natural) mineral waters, gases, and peloids (hydrotherapy, balneotherapy, or crenotherapy with various healing baths); the use of plain water (tap water; hydrotherapy), the use of climatic factors (climatotherapy); nutrition (nutritional therapy); exercise; massage therapy; psychotherapy; health education; complementary and alternative therapies; and so on [66]. Furthermore, this includes the use of environmental factors, such as those classified according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, and the performance of individual activities, such as walking, lounging, sitting, bathing, drinking, inhalation, and so on, as well as the taste or sensation of natural conditions, such as spring or running water, ordinary water, gases, peloids (sludge or silt dispersions with healing effects, or fango, the term for mineral-rich and nutritious mud), among others. The climate of a certain forest area can prove to be healing [37]. This is supported by a growing body of scientific research documenting the measurable physiological and psychological effects of forest environments on human health. Some studies have focused on direct biophysiological measurements, such as reductions in blood pressure, heart rate variability, and cortisol levels during or after exposure to forested areas [67,68,69,70]. Others have explored the broader therapeutic potential through the lens of balneology, emphasising the synergistic effects of the forest microclimate, clean air, negative air ions, and other natural elements in promoting overall health and well-being [71]. For example, Stier-Jarmer et al. [66] argued that forest-based interventions have a positive impact on the cardiovascular system. As claimed in [69], some activities that are typical of outdoor tourism, such as tai chi and yoga, have been suggested as stress-reducing and immune-boosting exercises that should be practised in forests for individuals who are in good health to prevent COVID-19. Moreover, Andersen et al. [72] conducted a systematic review of studies conducted from 1995 to 2018 in which the physiological and psychological effects of forests on people were measured, and they identified that volatile substances from plants in the selected forest ecosystem had anti-inflammatory effects on people. In another study, a Japanese forest bath (or “shinrin yoku”) was identified as an anti-stress forest product, which means that forest bathing has beneficial effects on depression, anxiety, and negative emotions [73,74,75]. These findings can play a significant role in evaluating the therapeutic potential of forest climates. Assessing the physical, chemical, and microbiological factors in forest environments can provide a strong scientific rationale for designating specific forest areas as therapeutic or healing environments, particularly in the context of establishing forest climate resorts and promoting evidence-based forest therapy tourism. The wide range of traditional and non-traditional forest activities that are attractive to tourists, including the use of material and non-material goods offered by NWFPs and SCVs, is expanding (Article 8 of the Alpine Convention mentions the growth in tourism and relaxation activities, as well as the increasing use of social and ecological functions of the forest, as the forest is becoming increasingly important for everybody due to its recreational function (https://www.alpconv.org/sl/domaca-stran/konvencija/okvirna-konvencija/, accessed on 18 May 2025). According to the Future of Wellness report [76], caring for one’s own health is a growing trend, as guests’ demand for health and wellness products continues to grow, according to GoodSpaGuide data [77]. This includes the demand for alternative therapies, such as thermotherapy, massage, heliotherapy, hydrotherapy, and so on, as well as the demand for natural and personalised products, such as the preparation of antioxidants, natural ointments, edible herbal spreads, and natural preparative cosmetics, among others.

3. Materials and Methods

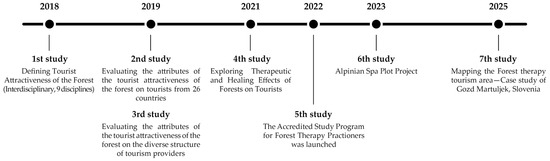

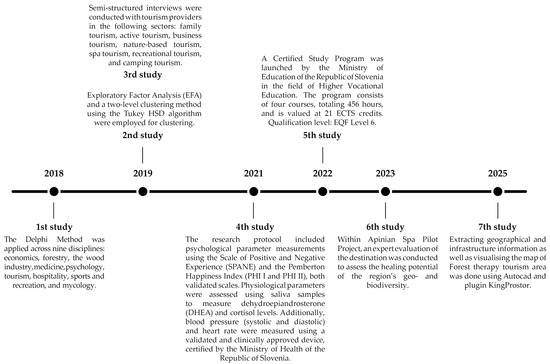

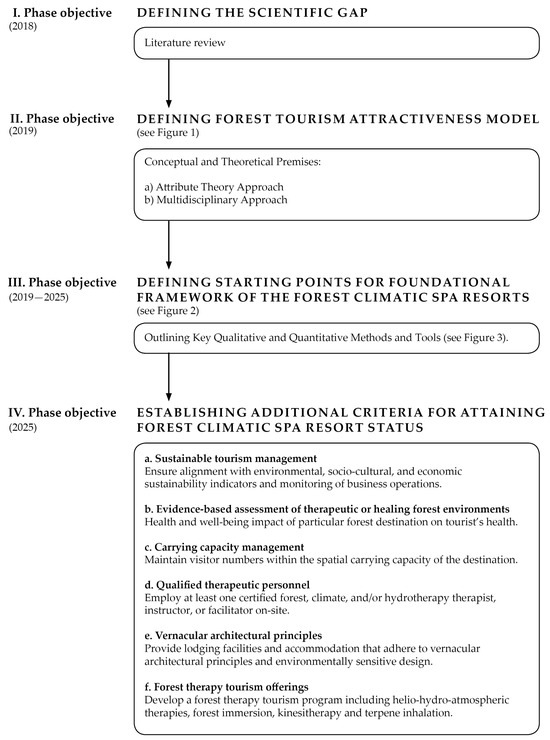

To address the research gap, we have formulated the following research questions: What are the key attributes and factors that define the attractiveness of forests to tourists? What specific requirements are needed for a sustainable management approach when operating a forest tourism business? Which specific conditions constitute the criteria for developing a foundational framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts? With the aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of forest attractiveness and to support the sustainable development of forest therapy tourism, the tourist attractiveness of forests evaluated in this study was defined in order to establish a professional framework with expert recommendations for the development of Forest Climatic Spa Resorts by using an attributive theory approach. In this section, the research methods are presented in detail. These methods were employed in various studies, which aimed to address the research questions posed in this study. Seven studies were conducted from 2018 to 2025 to evaluate forest attractiveness: each study was aligned with specific research goals and grounded in either a qualitative or quantitative methodological approach, depending on the nature of the research questions posed. (Due to the scope and complexity of the overall study, it is not possible to present all aspects in detail within the scope of this paper. Therefore, we focus on highlighting the key findings and essential insights. The sampling and sample design for the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th, and 7th studies entailed the comprehensive incorporation of all relevant participants and elements (i.e., typical tourism service providers, tourists, or geomorphological features) situated within or near the forest. Taken together, these seven studies provide a coherent and empirically grounded foundation for the formulation of a framework to guide the designation and development of Forest Climatic Spa Resorts. The author of this paper conducted the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 7th studies independently and served as a co-author in the 4th and 5th studies. The 6th study was carried out within the Alpine Spa Plot Project under the auspices of the Strategic Research and Innovation Partnership for Tourism (SRIPT), Slovenia, where a consortium worked to develop an innovative, green, and boutique product named “Climatic Resort.” The author was contractually engaged by the Centre of Business Excellence (Ljubljana, Slovenia) to define the professional terminology and conceptual framework for Climatic Resorts. A brief overview of the materials and methods used in each study is provided in this section. In designing this research, our primary methodological objective was to establish a structured and transparent research framework that would enhance the clarity and usability of findings related to the tourist attractiveness of forests and the growing demand for forest-based tourism. Therefore, each of the studies mentioned in the following text is presented according to three criteria: (1) the definition of research objectives, which are specified under each successive study in Figure 2, (2) outlining key qualitative and quantitative methods and tools (see Figure 3), and (3) providing a conceptual framework of the research design (see Figure 4). At the foundation of this methodological design lies the attributive theory approach [29,78,79], which was employed in the initial 1st study to assess natural and perceived forest attributes as fundamental determinants of tourism attractiveness. The sequential alignment of the seven studies reflects a cumulative process—each building upon the insights of the previous one—culminating in the identification of criteria for designating forest areas as potential sites for Forest Climatic Spa Resort development. Some of the mentioned studies were carried out in Kranjska Gora (4th, 6th, and 7th studies), a destination area in Slovenia, while others were conducted in different forested areas of Slovenia and Croatia; only the 1st study was conducted by mail correspondence with experts from different countries (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2.

Timeline of studies conducted from 2018 to 2025: phases, research objectives, and temporal distribution.

Figure 3.

Outlining key qualitative and quantitative methods and tools. Source: the author.

Figure 4.

The conceptual framework of the research design. Source: author.

All research methods and tools are briefly described in the following section and are presented in Figure 3. Due to space limitations, this article does not provide a detailed description of the methodological procedures for all seven studies. Instead, we aim to conceptually outline the key phases and approaches undertaken.

The first research objective was to identify a set of attributes that define the tourist attractiveness of the forest. Based on the attributive theory approach, this research was conducted with ten (10) researchers from nine (9) different disciplines who appeared in a literary review on the topic of forest tourism during the observed period and accepted the call to collaborate in a Delphi conference. Since a different number of experts representing each profession responded to our call (see Table 1), we decided to use a balanced formula, based on which each profession was equally represented in the evaluation of the attributes of the tourist attractiveness of the forest (for more information about the Balanced Formula for Expert Evaluation of Forest Tourism Attributes Across Different Disciplinary Domains, please refer to the repository of the University of Primorska, PhD, Cvikl, Darija: https://repozitorij.upr.si/IzpisGradiva.php?id=18100&lang=slv (accessed on 18 May 2025). Table 1 shows that only the field of mycology was represented by one expert, whereas all the other fields were represented by multiple professionals. This was also why a formula to balance the results was developed for ten participants in a Delphi conference, as we wanted an objective and unbiased final opinion, where no discipline is overrepresented. The obtained set of attributes was designed to be verified by tourists and tourism providers in one of the following research projects.

Table 1.

Representation of individual disciplines in Delphi conference.

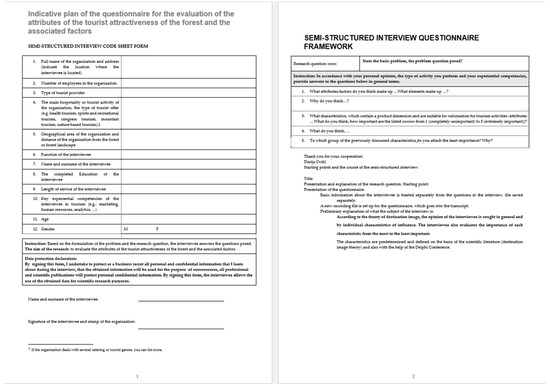

The second objective in the following research was to rank the importance of the obtained attributes on the tourist demand and supply sides. The attributes of the tourist attractiveness of the forest were evaluated in the 2nd study by 333 tourists from 26 countries. In implementing the 2nd study, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and a Two-level Clustering Method with Tukey’s HSD algorithm were used. This procedure is suggested for hypothesis testing when groups or clusters have different sizes [80]. Factor analysis is often used to eliminate individual factors based on a larger number of attributes [21] (p. 542), which applies to our research. The 3rd study explored the attitudes of ten tourism providers in diverse fields located in or near a forest area towards the obtained set of attributes by analysing their opinions and views about the tourist attractiveness of the forest. (The first, second, and third studies are presented in more detail in the author’s Doctoral Dissertation. This Dissertation is available in the repository of the University of Primorska. Accessed on 14 April 2025 at the following link: https://repozitorij.upr.si/IzpisGradiva.php?id=18100&lang=eng&prip=rul:25151954:d2.) Companies or tourist organisations in the sample varied in size—from 3 to 30 employees (campsite) to a maximum of 400 (camping resort). The following types of tourist service providers were involved: campsite, camping resort, specialised agency for bicycle tours, medium-sized hotel, hotel resort, and health resort and restaurant in the forest. (For more information, please see the author’s Doctoral Dissertation. This Dissertation is available in the repository of the University of Primorska. Accessed 14 April 2025 at the following link: https://repozitorij.upr.si/IzpisGradiva.php?id=18100&lang=eng&prip=rul:25151954:d2.) Semi-structured interviews were conducted using a designed questionnaire and coding sheets. Interviews were conducted in the period from June to October 2018 and in April and June 2019. Descriptive coding was applied to identify individual interviewees’ reasoning and answers to questions on the basis of similar or the same collocations, sentences, or examples given.

The third objective was to explore the therapeutic and healing effects of forests on tourists. The results of this 4th study, conducted in 2021, along with the measured parameters, the implemented methodology, and the research protocol design, are published in the journal Forests. (View the published study by Cvikl et al. (2022) [67]. Accessed 14 April 2025 at the following link: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/13/10/1670.) Fifty (50) volunteers in the age group from 19 to 100, both male and female, were initially included in the study. An online announcement was made to recruit volunteer participants who were tourists—defined as individuals residing at least 50 kilometres away from their permanent residence and staying overnight at the Kranjska Gora destination. People who were unable to complete the questionnaire, were unable to walk in the woods, did not submit all the necessary samples before and after the therapies, and did not adhere to the deadlines in the implementation protocol (submitted samples or completed questionnaires late or at different deadlines) were excluded. The tourists underwent two forest therapy sessions in a forest. They walked approximately 1 km during each of the two forest therapy (hereinafter referred to as FTh) sessions on pre-selected forest paths. On Saturday, 19 June 2021, after the first night of sleeping at the destination, all participants were considered tourists. After breakfast, all tourists provided their first saliva samples in the morning to measure stress hormone concentrations (cortisol and DHEA), blood pressure (systolic and diastolic), and heart rate. In accordance with the protocol, measurements based on the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) [81,82] were taken before and after the FTh experience at the Kranjska Gora destination. Sampling tubes and sampling instructions were provided by the diagnostic laboratory, validated by the Ministry of Health, Slovenia. Saliva samples were collected instead of blood samples, mainly to avoid possible inconveniences or stress from needle insertion and because it is more user-friendly. On Saturday, 19 June 2021, during the day, tourists were divided into 4 groups 2× (1× morning and 1× afternoon) and participated in FTh. The first FTh session lasted 3 h and was conducted between 10 a.m. and 1 p.m., and the second lasted for 2 h between 3 p.m. and 5 p.m. On Sunday, 20 June 2021 (after the second night at the resort), all tourists participated in the survey in the morning between 8 and 9 a.m. and underwent the same set of tests and measurements as on Saturday, at the same time as on the previous day.

The fourth research objective was to develop and officially verify a Nationally Accredited Certified Study Programme for Forest Therapy Providers, which was the focus of the 5th study. This study programme was certified at the state level by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Slovenia as a wellness programme. This programme is the result of a multidisciplinary collaboration between representatives of the tourism and medical sectors and is based on the national curriculum for welfare-related activities, adopted by the Expert Council of the Republic of Slovenia for Vocational and Technical Education 196th session, 21 October 2022. It is the first of its kind in Europe. The programme consists of four courses, totalling 456 h, and is valued at 21 ECTS credits; the qualification level is EQF Level 6.

Within the framework of the Alpine Spa Pilot Project, the 6th study, three main objectives (i.e., fifth, sixth, and seventh) were defined and implemented. The first objective was the expert evaluation of the destination’s healing potential based on the region’s geological and biological diversity. (Terpenes were identified using gas chromatography with a mass-selective detector (GC/MSD). Further information about the expert evaluation of the healing potential of the Kranjska Gora destination is available at the following link (page 49): https://obcina.kranjska-gora.si/Files/TextContent/70/1736340113456_Strategija%20razvoja%20in%20upravljanja%20turizma%20v%20obc%CC%8Cini%20KRANJSKA%20GORA%202035_sprejeta_18122024_1.pdf (accessed on 14 April 2025). The second objective was to develop a manual for awarding the status of a Climatic Health Resort, intended for destination managers, and the third was to organise and implement the 5th Congress on Forest and its Potential for Health, held in Slovenia under the auspices of the International Society of Forest Therapy (ISFT), Piaristengasse 1, A-3500 Krems/Donau, Austria. The primary objective was to produce validated knowledge that would serve as the foundation for a comprehensive manual, intended to assist tourism stakeholders in implementing health-promoting tourism practices at the local level. The Alpine Spa Project was implemented under the auspices of the Strategic Research and Innovation Partnership for Tourism (SRIPT) (for more information about the Alpine Spa Pilot Project, see https://www.slovenia.info/sl/novinarsko-sredisce/novice/7240-turisticno-gostinska-zbornica-slovenije-je-nosilka-srip-turizma (accessed on 14 April 2025) and the internal archive of Tourism Kranjska Gora) and involved the collaboration of key stakeholders, including the Chamber of Tourism and Hospitality of Slovenia, the Kranjska Gora Municipality, the Kranjska Gora Tourism Board, Hit Alpinea, d.d., Jasna Chalet Resort, and the Vocational College for Hospitality, Wellness and Tourism, Bled.

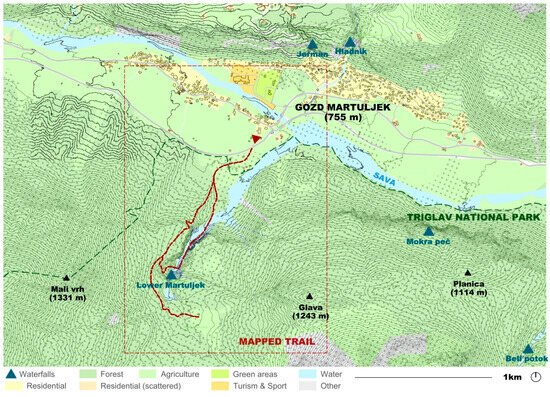

The eighth objective, the focus of the 7th study, was to map a therapeutic forest path as an FTh activity based on carrying capacity. In this research, an area of lower Martuljek Slap was chosen, where clinical trials have already been carried out and proven the therapeutic effects of geodiversity as well. The FTP in Gozd Martuljek, together with its natural value, was studied in situ through fieldwork and with the help of the Nature Information System—NarcIS version QNarcIS_2.2.1.1. The website narcis.gov.si was developed under the auspices of the Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO) and represents the natural heritage database of the Republic of Slovenia. Architectural software Autocad 2025 and KingProstor 2025 plugin v25.8.2 were used to map the area of the lower Martuljek Slap. The conceptual framework of the research design for all the above studies can be seen in Figure 4.

4. Results

In this section, we present the findings of individual research projects, which also represent the evidence-based criteria that a particular destination must meet in order to qualify as a Forest Climatic Spa Resort. Due to space constraints, only essential findings are presented. In addition, not all results are displayed for each criterion, as some concepts are already very well known and established, such as carrying capacity. In the final part, we also present the foundational framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts, formulated on the basis of all previous findings. The foundational framework presents a well-founded summary of all targeted research conducted so far on the topic of forest therapy tourism. The subsections are named based on the essential objectives achieved by each study.

4.1. A Comprehensive Set of 36 Attributes and 7 Principal Factors Defining Forest Tourism Attractiveness

A Delphi conference was conducted in order to obtain a comprehensive set of attributes. The aim of defining attributes was not only to obtain a certain set attractive to different users of the forest but also to define the characteristics that define a potential tourist resource, i.e., those that can also be valorised. Consequently, the experts who participated in the Delphi conference were asked to consider the overall concept of tourist attractiveness and not only to identify an attractive characteristic of the attribute itself. Furthermore, during the Delphi conference, we aimed to include temporal stability and the production dimension when defining attributes because such characteristics can also be suitable for the creation and valorisation of a tourist product. Therefore, the criteria of validity [50] (p. 85), stability, and the production dimension in time and space [49] were taken into account. In the three repeated rounds of the Delphi conference implementation, 27 attributes characterising the tourist attractiveness of the forest were defined with an 80 per cent consensus among nine (9) different professions (see Appendix A.1). It was found that some attributes in the set merged several characteristics and, therefore, had to be broken down; furthermore, in accordance with the literature and factors of tourist attractiveness of the forest, more attributes were defined. For example, the attribute of sensoriality, which is under number 8 in the original set (see Appendix A.1), was broken down into several attributes in accordance with the senses, such as smell, taste, and sight. After the breakdown, there were thirty-six attributes (36) in the final stage. Forest attributes are considered as stated. The most important forest attributes that define the tourist function of the forest—from the most to least important—are shown in Table 2. Tourists and tourism providers rated biotic diversity first, followed by nature and the absence of pollution, while experts emphasised species diversity and natural beauty as key elements of the forest ecosystem. Following the environmental attributes, tourists ranked the forest’s healing and well-being attributes in the fourth, fifth, eighth, ninth, and tenth positions. This discovery subsequently directed the primary focus of further research towards exploring the forest as a therapeutic environment for the development of tourism activities.

Table 2.

Attributes defining the tourist attractiveness of the forest with a product dimension assessment, ranked by importance.

Considering the above, it can be concluded that the forest represents a highly suitable environment for wellness, therapeutic, and even healing tourism.

The previously obtained set of thirty-six (36) forest attributes were used as the foundation for conducting the second study (see Table 3). To ensure the quality of the sample and the data, both univariate and bivariate analyses were conducted. Univariate analysis was performed to review the significance of the data and perform data cleaning, as well as to determine the actual size of the sample (N). Bivariate analyses, such as the calculation of the correlation matrix between individual pairs of variables, were employed to examine interrelationships within the dataset. A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient value close to 1 was obtained, indicating high reliability and confirming that the selected sample of variables was appropriate for further statistical processing. Subsequently, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation was performed as part of the exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to process the thirty-six attributes. The suitability of the PCA method was confirmed by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. Prior to executing the final PCA, the distribution of all thirty-six variables was assessed by examining the skewness and kurtosis. Two attributes—nature and non-pollution—were excluded from further analysis because their skewness and kurtosis values significantly exceeded the acceptable range (−2 to +2). This indicates that, although tourists clearly recognise the importance of an unpolluted forest and its natural beauty, the non-normal distribution of these attributes necessitated their removal to maintain the validity of the factor analysis (see Appendix A.2). The skewness and kurtosis values for the remaining attributes fell within the acceptable range, making them suitable for inclusion in further analysis. Following the completion of the factor analysis and the extraction of five rotated component matrices, the final rotation showed that there were no more cross-loadings. Therefore, a final set of twenty-nine (29) attributes and seven (7) principal factors of forest tourism attractiveness were identified. The final solution showed a very good KMO test result for sampling adequacy, as it amounted to 0.87, and Bartlett’s test was significant. The study identified seven factors influencing the attractiveness of forest tourism. Each factor included specific associated attributes, with a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient calculated separately for each factor. Additionally, factor weights were applied for every attribute. A total of 242 tourists from 26 different countries participated in the ranking of these factors. All participants were adults and held the status of tourists. The factors were named based on the attributes they include. Six of the factors correspond to those commonly found in the existing literature. One factor was newly developed in this study. This new factor, named the ecosystem specifics factor, consists of attributes related to the forest ecosystem, particularly the presence of diverse plant and animal species. All derived factors were found to have a significant impact on the perceived attractiveness of forests. Based on the participants’ evaluations, the factors are ranked in the following order of importance: perception–recognition factor, infrastructural factor, factor of natural characteristics, educational factor, ecosystem specifics factor, social and environmental responsibility factor, and personal–behavioural factor. The derived factors influencing forest tourism attractiveness, along with their associated attributes, are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comprehensive set of 29 attributes and assessment of 7 principal factors of tourist attractiveness, ranked by relevance according to tourists.

In the third study, ten (10) semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of tourist service providers. The interviews were conducted in the period from June to October 2018 and in April and June 2019 and were coded based on unified coding sheets (see Appendix A.3). The main result of collecting and analysing the opinions and views obtained can be defined as the identification of tourist attributes and factors of forest attractiveness (see Appendix A.4). A comparison of the factors of tourist attractiveness of the forest, as evaluated by tourists and tourist service providers, showed that the following five factors were identified by both groups: the factor of natural characteristics, the infrastructural factor, the educational factor, the personal–behavioural factor, and the perception–recognition factor. It should be pointed out that the respondents and interviewees in both groups, i.e., tourists and tourist service providers, assessed the natural characteristics factor and its attributes, biotic diversity and non-pollution, with the highest grade possible. On average, tourist service providers evaluated the infrastructural factor higher than tourists, while they attributed the lowest significance to the information or educational factor. Some factors were identified only by tourists, while others were identified only by tourist service providers. There were discrepancies in the economic factor, which was identified only by tourist service providers, who recognised it as an autonomous factor. On the other hand, tourists distributed individual attributes that represent the economic factor, such as the price level and the quality of accommodation, among other factors. The opposite was found for the ecosystem specifics factor and the social and environmental responsibility factor. The PCA algorithm recognised both factors as independent. Tourist service providers grouped individual attributes that constitute social and environmental responsibility within the personal factor of behavioural characteristics. During the interviews, tourist service providers associated the attributes that belong to ecosystem specifics, such as biodiversity and the size of trees, with the natural factor of tourist attractiveness of the forest. The evaluations of the factors of tourist attractiveness of the forest by tourists and tourist service providers are compared in Table 4.

Table 4.

Factors of tourist attractiveness common to tourists and tourist service providers.

4.2. The Therapeutic Effects of Forests on Tourists and the Therapeutic Effects of the Destination’s Healing Potential

Fifty (50) participants were reached and agreed to undergo physiological and psychological measurements according to the designed protocol (further information is available at the following link: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/13/10/1670, accessed on 14 April 2025). Additionally, they agreed to be granted the status of tourist by accepting two nights of accommodation in the Kranjska Gora destination. Of the 50 selected volunteers, 47 valid samples for physiological measurements were obtained. Due to COVID-19 or the non-submission of a saliva sample prior to therapy, three participants cancelled their registration or did not completely undergo the required physiological measurements. In addition, each participant filled out two psychological questionnaires twice. Due to incomplete answers or unsubmitted questionnaires, 7 questionnaires were invalid, and 43 valid questionnaires were obtained for the further processing of the results.

The following parameters were measured according to the study protocol design before and after the FTh experience: the stress-indicating hormone DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone) with a saliva sample; the stress-indicating hormone cortisol with a saliva sample; blood pressure (systolic and diastolic); heart rate; stress index; the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE); and the Pemberton Happiness Index (PHI I and PHI II). Differences in the average values of the measurements of physiological parameters before and after forest therapy are presented in Table 5. The hormone dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) decreased much more than cortisol during FT. It decreased by 26% in the general population, 41% in men, and 18% in women. Because men had high variability in this hormone, this decrease was not significant in men or the general population, but it was significant in women. The decrease in systolic pressure, diastolic pressure, and heart rate (pulse) was statistically significant both in the entire population and in a separate analysis of the female subpopulation. In men, due to greater variability and a smaller blood pressure reduction, the result was not significant.

Table 5.

Differences in average values of measurements of physiological parameters before and after forest therapy.

In this study, the stress index was also taken into account. It is calculated as the average of the normalised values of all five measured physiological parameters according to the following formula:

The decrease in the stress index was statistically significant both in the overall population and in a separate analysis of the female subpopulation. In men, due to greater variability or a lower pressure reduction, the decrease in the stress index was not significant, although the decrease was larger than in women. We observed that volunteers who had a higher level of stress at the first measurement had a larger stress reduction during FT. Therefore, we performed an additional calculation from which we excluded 19 volunteers with a baseline stress index of less than 85. In the remaining 28 volunteers with higher stress, the reduction in the stress index was as high as 11.7%. In the overall population, there was an improvement of 7%. As normalisation coefficients (nk, nD, ns, nd, and np), we used the average normal values of each parameter as follows: ten (10) for cortisol, one thousand (1000) for DHEA, one hundred and twenty (120) for systolic pressure, eighty (80) for diastolic pressure, and seventy (70) for pulse. In this study, the stress index decreased during FT by more than 7% in the entire population. The decrease was 5% for women and 13% for men, as presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Average values of stress index before and after forest therapy.

The results of the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) before and after the FTh experience showed that individual positive emotions improved, while the impact of negative emotions decreased. Except for the stress parameter, all other measured parameters showed statistically significant positive results, as presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE) before and after the forest therapy experience: display of paired samples.

In addition to assessing the beneficial and therapeutic effects on tourists, within the framework of the Alpine Spa Pilot Project at the request of the Kranjska Gora Tourism Board, an expert evaluation (further information on this study is available at the following link (page 49): https://obcina.kranjska-gora.si/Files/TextContent/70/1736340113456_Strategija%20razvoja%20in%20upravljanja%20turizma%20v%20obc%CC%8Cini%20KRANJSKA%20GORA%202035_sprejeta_18122024_1.pdf, accessed on 14 April 2025) of terpenes in the mapped area was conducted, and they were identified to have healing effects on respiratory problems (chronic obstructive pulmonary bronchitis, inflammation of the upper respiratory tract, allergic irritations of the respiratory system), cardiovascular complications (chronic heart failure patients, rehabilitation of patients after cardiology treatment, and other cardiovascular problems that do not require emergency cardiology treatment), psychosomatic disorders, and skin problems.

4.3. A Nationally Accredited Certified Study Programme for Forest Therapy Providers

The goal of the fifth study was to launch a study programme certified by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Slovenia in the field of Higher Vocational Education. A Nationally Accredited Certified Study Programme for Forest Therapy Providers was launched in 2022 (further information on this education programme is available at the following link: https://cpi.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Izvajalec_izvajalka-gozdnih-terapij.pdf, accessed on 14 April 2025) to ensure professional standards, scientific grounding, and the safe and effective delivery of forest therapy interventions in the tourism sector. This programme fosters interdisciplinary knowledge, enhances credibility within the healthcare and tourism sectors, and supports the institutional recognition of forest therapy as an evidence-based practice. Therefore, a higher education specialisation programme in the field of wellness has been developed as a result of multidisciplinary collaboration among experts from tourism, medical sciences, and didactics. The programme consists of four courses, totalling 456 h, and is valued at 21 ECTS credits. The qualification level is EQF Level 6.

4.4. The Development of a Manual for Awarding the Status of an Alpine Spa Resort

This manual was developed for destination managers in Slovenia (further information on this manual is available at the Supplementary Materials. It was created under the auspices of the Strategic Development and Innovation Partnership for Tourism—SRIPT (author’s note: the author was invited to participate in the SRIPT primarily to clarify key terminology, to participate in the development of recommendations for obtaining the status of an Alpine Climatic Resort, and to contribute to the definition of emerging forest therapy potential)—and aligned with the Slovenian Tourism Strategy (2022–2028). It defines an Alpine Climatic Resort as a rounded geographical entity or destination that has favourable climatic conditions in the alpine macro-region, especially in parts where clean air, clean water, and coniferous forests with a favourable forest climate prevail. In achieving the above effects, the resort must base its work on ecosystem services, pursue sustainability, and take into account the recommendations of the profession, which is why these recommendations are listed in the manual.

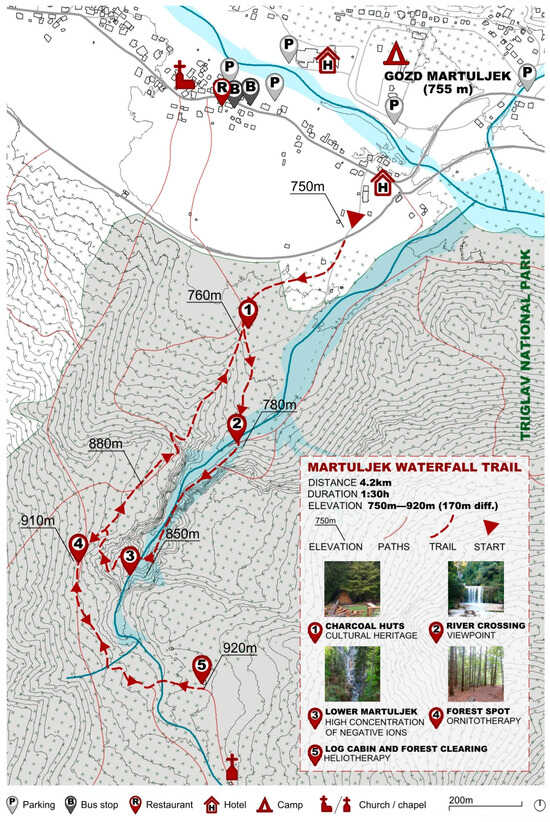

4.5. Mapping the Forest Therapeutic Path (FTP)—The Case of Martuljek Waterfall Trail

The framework of the NarcIS (further information on this natural heritage database of the Republic of Slovenia is available at the following link: https://narcis.gov.si/ords/r/narcis/narcis/life, accessed on 14 April 2025) was used in the design of the Forest Therapeutic Path (FTP) in Gozd Martuljek, as well as in identifying the natural and socio-cultural values of the studied local area and its product development potential and in assessing the spatial carrying capacity of the studied area. The NarcIS was developed under the auspices of the Slovenian Environment Agency (ARSO), Ministry of Enviroment, Climate and Energy, Vojkova cesta 1b, 1000 Ljubljana, SLO and represents the natural heritage database of the Republic of Slovenia. It was established in the field of habitat types and enables the monitoring of the environmental state and effective nature conservation planning in Slovenia, specifically based on the PHYSIS Catalogue of Habitat Types, which contains 708 habitat types, and the Natura 2000 Catalogue of Habitat Types, which includes 63 habitat types. When designing the FTP, which will be used for tourist purposes, it was necessary to rely on the findings which define the product dimension of socio-cultural values in a particular forest area and its intended use. Therefore, we started mapping the FTP in the destination of Kranjska Gora, more precisely in the forest area of the lower Martuljek Waterfall, located 876 m above sea level. The topographic map with natural attributes (mountain peaks, water bodies, land use, etc.) shows the position of the analysed Martuljek trail in relation to the natural and built environment (see Figure 5). At this location, healing effects were found near Martuljek Waterfall in one of the previous studies, which verified the positive healing effects of the forest climate on tourists’ bodies and minds based on their psychological and physiological measurements (see fourth and sixth studies) and on the high content of biogenic volatile organic substances in the area. The mapped area is part of one of the oldest protected areas of national importance in Slovenia—the Martuljkova mountain group—and the international protected area Natura 2000 (author’s note: internationally important sites are protected under the Convention on the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, the Convention on Wetlands or the Ramsar Convention, the international Geosciences and Geoparks Programme, and the Man and the Biosphere Programme (MAB); Electronic Source Retrieved 15 May 2025: https://narcis.gov.si/ords/r/narcis/narcis/obmocja-s-statusom), situated in the northwesternmost part of Slovenia. The municipality of Kranjska Gora, in its marginal southern part, lies next to the Triglav National Park (more information about fauna of Triglav National Park is available at the following link: https://www.tnp.si/en/park/nature/fauna/, accessed on 15 May 2025), which is home to rare species of plants and animals, such as the rock ptarmigan (the only songbird that can dive and swim), the Soča trout, the alpine marmot, the red deer, the brown bear, the chamois, and the ruffed grouse. The lower Martuljek Waterfall has three waterfall stages and exceptional design features. Access to the trail is easy and suitable for all generations; the starting point is the village of Gozd Martuljek, with a well-arranged system of bus stops. The FTP is not intended for access by private cars. The Martuljška Bistrica River flows through the gorge along the way, connecting the upper and lower Martuljški Waterfalls, and in the village of Gozd Martuljek, it flows into the Sava Dolinka. The landscape of this area is glacial in origin and is characterised by high rocky ridges, grassy slopes, magnificent waterfalls, lakes and rivers, and rich flora and fauna. The largest part of this area is covered with alpine beech and spruce, and areas at higher altitudes are covered with larch and those on more developed soils with fir. The selected forest area is extremely rich in natural features and attractions and has the status of a forest of special importance, intended for tourist use.

Figure 5.

Topographic map of the mapped FTP area. Source: author.

The defined FTP is 4.2 km long and takes 1.5 h to traverse. It is situated mainly on a forested/wild trail or path (3.2 km); only the beginning of the FTP is asphalt (0.4 km). The trailhead is located at an altitude of 754 m. Based on the findings for the dimensions of forest product potential and SCVs, we designed the Martuljek Waterfall Trail (see Figure 6). The mapped area is located within the highly developed mountain destination of Kranjska Gora, close to the local hospital. Despite its position, the site remains remote from major traffic infrastructure and is free from noise pollution, offering a tranquil and health-supportive environment. The first FTh spot is dedicated to local cultural heritage, as charcoal huts are located there. The second FTh spot is mapped at the river crossing point and is designated for dendrotherapy (therapeutically guided forest therapy by touching the vegetation, especially the stems and branches of trees) and colour therapy (where green exerts a sedative effect on the vegetative and hormonal system of the organism). Therefore, observing and smelling the forest’s natural beauty and ambience is recommended here. The third FTh spot was chosen because of its proven high content of medicinal terpenes, intended for their healing effects on respiratory problems, cardiovascular complications, and skin problems and aromatherapy (due to their ethereal characteristics, specific smells in the forest have enhanced effects on the vegetative nervous system). The fourth FTh spot is intended for ornithotherapy (listening to birdsong, which, together with the sounds of the forest and the rustling of leaves in a gentle breeze, has been proven to have a beneficial effect on human well-being). The fifth spot is located at a forest clearing for heliotherapy (exposure to natural mountain sunlight for its health benefits), which is used to boost the immune system, improve mood, and stimulate vitamin D production in order to treat various conditions, such as skin problems and stress.

Figure 6.

Martuljek Waterfall forest therapy map. Source: author.

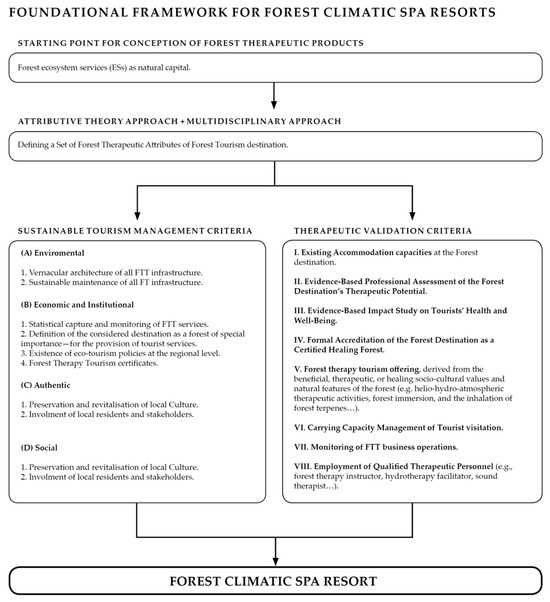

4.6. Foundational Framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts

The proposed foundational framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts is based on empirical evidence, research-based findings, and well-established theoretical concepts, with ecosystem services serving as a starting point in the development of destinations aspiring to obtain the status of a Forest Climatic Spa Resort. The tourist attractiveness of forests evaluated in this study was defined in order to establish a professional framework with expert recommendations for the development of Forest Climatic Spa Resorts by using an attributive theory approach. This framework is evidence-based and pragmatic, designed to guide the actual development and classification of destinations. It serves as a primary foundation for the standardisation, implementation, and application of forest therapy offerings, operations, and management within the tourism and economic sectors. The term Forest Climatic Spa Resort typologically defines a form of forest-based wellness and tourism activity situated within developed tourism infrastructure. Therefore, it is classified under forest tourism, which itself falls under the broader category of nature-based tourism. Based on these scientifically validated findings, we propose that destinations align their development and positioning strategies with the proposed framework by following the given recommendations.

It is important to clearly differentiate the conception and understanding between destination managers who want to offer a forest therapy service and those who want to develop a Forest Climatic Spa Resort. According to the schematic presented in Figure 7, the Forest Climatic Spa Resort term can be used for a destination that demonstrates sustainable tourism management using an environmental, economic and institutional, authentic, and social approach. Additionally, such a destination should provide existing accommodation capacities at the particular forest destination; an evidence-based professional assessment of the particular forest destination’s therapeutic potential; an evidence-based impact study on tourists’ health and well-being; the formal accreditation of the forest destination as a certified healing forest; structured forest therapy offerings; carrying capacity management of tourist visitation; the monitoring of forest therapy tourism operations; and the employment of qualified therapeutic personnel. On the other hand, the designation Forest Therapy Destination applies to specific forest areas where the offerings follow structured forest therapy programmes led by qualified forest therapists, established practices are in accordance with an evidence-based certified forest area, and the destination is in accordance with sustainable tourism management using an environmental, economic and institutional, authentic, and social approach.

Figure 7.

Foundational framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts. Source: author.

5. Discussion

Forest tourism is being increasingly recognised, as evidenced by the works of Chen and Nakama [37], Rantala [83], and Font and Tribe [84]. The number of green tourists, so called by Bixia and Zhenmian [63], (p. 288), has been growing continuously, and the healing attributes of forests are increasingly recognised and form the basis for the development of new, trendy tourist activities, as also stated in EU development documents [58,60,85] and many scientific reports [3,4,5,6,86]. Nevertheless, despite increasing interest in forest therapy tourism, the field remains critically underdeveloped, lacking a coherent, evidence-based framework to guide the establishment of Forest Therapy Destinations and Forest Climatic Spa Resorts. There has been no systemically and conceptually comprehensive research on the attractiveness of the forest as a tourist destination. Furthermore, recreation or tourist activity in the forest is discussed mostly to ensure sustainability in the provision of ecosystem services and the interaction between nature and users rather than from the aspect of a tourist destination and the need for the segmentation of forest users. Therefore, this study was structured into seven different research stages, aiming to address this scientific gap by defining a comprehensive set of forest tourism attractiveness attributes, developing a model of forest tourism attractiveness, and formulating appropriate theoretical and conceptual foundations to support the criteria for the development of Forest Climatic Spa Resorts. This conceptual paper offers significant contributions at both scientific and applicative levels. In the field of the theory about destination attractiveness, a model for the general attractiveness of the forest is presented for the first time. It is an attributive model that originates from ecosystem services and considers the forest as natural capital. Bayliss et al. [62] classified natural tourism and recreation into ecosystem services, which may include market goods as well as public goods. To the author’s knowledge, to date, no comprehensive model of forest tourism attractiveness has been developed, nor has there been an attempt to establish evidence-based justifications for sustainable concepts designed for the development of criteria for the Forest Therapy Destination status or the Forest Climatic Spa Resort framework. Considering the results obtained from the conducted research, it can be concluded that the forest represents a highly suitable environment for wellness, therapeutic, and even healing tourism. However, the greatest limitation of the research findings on forest attributes and tourist attractiveness to date lies in the reliance on expert focus or panel groups, which are too narrow and, consequently, fail to recognise the diversity of user segment groups (including tourists) and their needs. The existing literature often considers the forest as an environment within which forest therapy activities with a tourist or recreational character are carried out, and it acknowledges that tourism plays a significant role in the region’s economy [3,7,8]; however, these studies have only partially addressed the field of forest tourism, as they are conceptually framed primarily from non-tourism disciplines (forestry, land economics, ecology, etc.). They do not sufficiently consider the perspective of tourism studies, where tourist behaviour and preferences are clearly linked to the attractiveness attributes of a destination or its product dimension [87].

In the first stage of the research, the Delphi method was selected because of the interdisciplinary nature of the use of forests for tourist purposes, due to which numerous tourist activities have been developed and are developing in forests on the basis of different disciplines. It was assumed that such a versatile use of forests by tourists originates from their versatile needs. In our opinion, such an approach is appropriate because, to date, research has not accounted for interdisciplinary perspectives when identifying the attributes that define the tourist attractiveness of the forest, which we consider a gap that must be filled. The attributes that represent the attractiveness of a certain destination can significantly vary [21] and may represent push or pull motivators [27,45] and include the psychological characteristics of tourists or their cognitive or affective perceptions or attributes of the natural attractiveness of a destination, psychographic attributes. Tourists ranked some attributes of the recreational–tourist use of the forest that are the most important for forestry [14] rather low. These include the size of the trees, the transparency of treetops, and a picturesque forest edge. Several limitations must be acknowledged in the second phase of the research. Although tourists spent only two nights at the destination and experienced forest therapy (FT) within a single day, the physiological and psychological measures showed a significant reduction in stress levels, making the findings very encouraging. However, the small sample size of interviewed tourism providers limits the generalisability of the qualitative findings; isolating the effects of accommodation from the forest environment remains challenging, and achieving a sufficiently large sample under controlled conditions is economically demanding. Additionally, measurement tools such as SPANE are designed for longer-term assessment (several weeks to a month), whereas short-term tourist stays (typically 2–3 days) may introduce variability in the results. Despite efforts to minimise interfering factors by timing measurements between two nights, a truly controlled study comparing forest and non-forest environments remains necessary. Practical and financial constraints in tourism research also prevent longer observational periods, even though psychological scales are more stable over longer timespans. Nevertheless, the study design reflects realistic tourist behaviour and accommodation patterns, strengthening its relevance for tourism practice. In addition, when designing any tourism activity, especially those carried out in forest environments and protected areas, it is essential to consider the carrying capacity of the area in the planning process [21,88]. A Forest Therapeutic Path needs to be sustainably developed and maintained for long-term use, including for tourism purposes, only through collaboration with local communities, district foresters, and nature conservation experts. This is particularly relevant since tourism encompasses various multidisciplinary fields, each of which can, through a structured approach, appropriately evaluate the forest therapy tourism potential of a given destination. Therefore, we recommend that destination management, when planning FTT activities, implement a web-based geographic information system (GIS) platform, such as the NarcIS, which provides an excellent foundation for improving the quality of decision-making. Developing a Nationally Accredited Certified Study Programme for Forest Therapy Providers fosters interdisciplinary knowledge, enhances credibility within healthcare and tourism sectors, and supports the institutional recognition of forest therapy as an evidence-based practice. Equally important is the standardisation of criteria for obtaining the title of Forest Therapy Provider. At the moment, the current global situation is characterised by a fragmented range of forest therapy training programmes, including numerous short-term or fully online courses, many of which lack scientific rigour or formal pedagogical structure. This heterogeneity presents significant risks in terms of quality assurance and the public’s trust in the profession. A global comparison of forest therapy study programmes and training courses reveals that few have been formally institutionalised at the national level, with notable exceptions such as South Korea (forestry sector) and Slovenia (wellness sector). Elsewhere, programmes have emerged in diverse disciplines, including forestry (Slovakia), medicine (Japan), public health (Germany), and psychology (the United States). However, significant differences in the conceptualisation of forest therapy remain worldwide. Alongside these national approaches, numerous international organisations have been established, including the International Society of Forest Therapy (ISFT®), the only global association that unites researchers from different disciplines worldwide under a patented trademark, headquartered in Krems, Austria (https://isft.info/). The Korea Forest Welfare Institute (FoWI) (https://fowi.or.kr), the Japanese Society of Forest Therapy (https://www.fo-society.jp/), and the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy (ANFT) in the United States also reflect the growing institutional support for forest therapy worldwide (https://anft.earth/). The results of this research are also applicable in practice—in health tourism, forestry, and medicine—because of the strategic cooperation among the planners and managers of the forest–economic area with tourist service providers in that field. In light of the new reality, where nature has become even more important due to COVID-19 [89], the findings of the research can be useful also for health policymakers.

6. Conclusions

This study examines the significance of tourist attractiveness of the forest in order to find out why and how the forest is attractive to tourists and tourist service providers. In spite of the fact that the forest and its material and non-material goods and values have been used for tourist purposes for a long time, the tourism industry has not dealt with the forest as a destination. We tried to bridge this gap by examining the general tourist attractiveness of the forest and defining and valuing the attributes and factors that affect it. In addition, FTT activities have been increasingly integrated across diverse professional domains, including tourism, forestry, public health, and spa and wellness tourism, as well as specialised forest tourism. However, the highly commercialised nature of many FTh offerings, together with fragmented development within forest environments, raises substantial concerns regarding their unstructured implementation, quality, and evidence-based foundation. Without appropriate conceptualisation, standardisation, validation, and management oversight by destination authorities or forest site managers, such activities can pose considerable risks, such as credibility loss, potential health effects on participants due to unvalidated methods, and decreased trust among stakeholders, such as tourism providers, healthcare providers, local communities, and so on.

With the aim of providing clear support for the sustainable development of forest-based therapy tourism, this conceptual study provides a comprehensive framework of an attributive model for defining the tourist attractiveness of a forest, seven factors of tourist attractiveness of the forest, and a foundational framework for Forest Climatic Spa Resorts with criteria presented for Forest Therapy Destinations and Forest Climatic Spa Resorts. The proposed frameworks thus address an essential gap by providing scientifically grounded guidance for responsible development and implementation when seeking to obtain the status of Forest Therapy Destination or Forest Climatic Spa Resort. The implications of this study are dual: first, it offers a structured and evidence-based framework that can guide policymakers and tourism developers in designing Forest Climatic Spa Resorts; second, it contributes to academic discourse by integrating attribution theory with sustainability criteria in forest-based tourism planning.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16071149/s1.

Funding

The fourth study was funded by the municipality of Kranjska Gora, Slovenia. The sixth study, the Alpine Spa Pilot Project, was funded by the Strategic Research and Innovation Partnership for Tourism (SRIPT) (for more information about the Alpine Spa Pilot Project, see https://www.slovenia.info/sl/novinarsko-sredisce/novice/7240-turisticno-gostinska-zbornica-slovenije-je-nosilka-srip-turizma, (accessed on 18 May 2025) and the internal archive of Tourism Kranjska Gora) and involved collaboration with and partial financing by the Kranjska Gora Municipality, Kranjska Gora Tourism Board, Slovenian Forestry Institute, and Jasna Chalet Resort.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. For more information regarding the fifth study about the Certified Study Programme, please visit https://cpi.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Izvajalec_izvajalka-gozdnih-terapij.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025). Further information regarding the sixth study and the expert evaluation of the healing potential of Kranjska Gora destination is available at the following link (page 49): https://obcina.kranjska-gora.si/Files/TextContent/70/1736340113456_Strategija%20razvoja%20in%20upravljanja%20turizma%20v%20obc%CC%8Cini%20KRANJSKA%20GORA%202035_sprejeta_18122024_1.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025). The full report is available at the Tourism Kranjska Gora Organization’s archive: https://kranjska-gora.si/en/about-kranjska-gora. More information regarding the sixth study and manuals can be found in Supplementary material. More information regarding the sixth study and the 5th ICPFH Congress can be found at the following links: https://kranjska-gora.si/en/events/5th-international-congress-forest-and-its-potential-for-health (accessed on 18 May 2025) and https://www.gozdis.si/en/events/5th-international-congress-forest-and-its-potential-for-health/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

Data Availability Statement

The following supporting information can be downloaded: For more information regarding the first, second, and third studies, please see the author’s Doctoral Dissertation. This Dissertation is available in the repository of the University of Primorska at the following link (accessed on 14 April 2025): https://repozitorij.upr.si/IzpisGradiva.php?id=18100&lang=eng&prip=rul:25151954:d2. For more information regarding the fourth study, please see the paper published in Forests at the following link: https://www.mdpi.com/1999-4907/13/10/1670#B25-forests-13-01670 (accessed on 18 May 2025). Further information is also available at the following link: https://kranjska-gora.si/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Porocilo-dela-Turizem-Kranjska-Gora-2021.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

Acknowledgments

The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DHEA | Dehydroepiandrosterone |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

| ESs | Ecosystem services |

| FT | Forest tourism |

| FTT | Forest therapy tourism |

| FTh | Forest therapy |

| NWFP | Non-wood forest product |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| SCV | Socio-cultural value |

| SPANE | Scale of Positive and Negative Emotions |

| PHI I, PHI II | Pemberton Happiness Index I and II |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

The most important tourist forest attributes, ranked by the total number of points according to experts in nine different professions.

Table A1.

The most important tourist forest attributes, ranked by the total number of points according to experts in nine different professions.

| Attribute ID | The Most Important Forest Attributes that Define the Tourist Function of the Forest—from the Most to the Least Important | Result = Total Number of Points Gained |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diversity, biodiversity; presence of diverse plant and animal species in the forest | 379 |

| 2 | Nature; natural environment | 376 |

| 3 | Natural environment, suitable for connection, spiritual renewal, healing; refreshment, awakening; regenerator of autoimmune human system; inspiration for connecting with own nature; re-connection with nature | 322 |

| 4 | Tranquillity; privacy; serenity; | 305 |

| 5 | Natural environment, beneficial for health (healing effects of trees and ambience) | 295 |

| 6 | Well rated and maintained hiking and cycling paths | 293 |

| 7 | Safety; cleanliness | 269 |

| 8 | Set of sensory emotional perceptions, such as colours, aromatherapy, sounds, taste of edible forest products, breathing in aromas, clean air, listening to sounds, and observation of forest colourfulness. | 269 |

| 9 | Optimal environment for conducting different workshops; physical activity stimulator | 225 |