Abstract

Forest edges, which serve as transition zones between forests and adjacent land cover types, are essential for providing wildlife habitats and delivering a range of ecosystem services, including cultural benefits such as recreation and welfare for people. This study evaluates the economic value of these cultural ecosystem services (CESs) in Gyeonggi-do, South Korea. Despite increasing development pressures driven by urban expansion, the social and ecological significance of forest edges remains underexplored. By applying travel cost and medical expense substitution methods, this study estimates the economic value of cultural ecosystem services, specifically forest recreation, at approximately KRW 65 billion, and the forest healing function at around KRW 896.5 billion across Gyeonggi-do. These results highlight the need for balanced planning and development regulations to safeguard forest edges and sustain their contributions to public health and well-being. By revealing the hidden social value of these cultural ecosystem services, this study aims to guide policies that promote sustainable land use and improve the quality of life for residents in rapidly urbanizing areas.

1. Introduction

The forest edge is a boundary between forests and adjacent land cover types, serving as a transition zone for flora, fauna, and soil types. These areas are subject to edge effects and provide significant natural value for wildlife, as they are less susceptible to storm damage and receive ample sunlight, offering abundant food and cover resources for animals [1]. Forest edges are not only critical habitats for wildlife but also provide numerous ecosystem services to humans, including provisioning, supporting, regulating and cultural services [2].

The benefits derived from forest ecosystems, including their edges, encompass a wide range of services: (1) climate regulation through carbon sequestration, (2) environmental benefits such as air and water purification, (3) provision of commercial products, and (4) social and cultural ecosystem values [3]. Many of these functions are particularly pronounced at the forest edge, where natural resources are abundant [4]. Among these, cultural ecosystem services (CES)—particularly recreation and welfare benefits—play a substantial role in enhancing human health and quality of life.

Despite the recognition of these ecosystem services, forest edges have increasingly been subjected to development pressures over the past few decades, accelerating deforestation worldwide. In cities with a high proportion of mountains and forests, these development pressures for urban expansion are particularly intense [5]. Such areas are popular for development not only because old city centers are densely developed but also because they offer a natural retreat for those weary of urban life. Therefore, in countries with small territories and high population densities, development pressures on forest edges are inevitably more severe [6]. South Korea, for example, has a relatively small territory (100,210 km2) and significant mountain cover (70%), leading to increasing pressures to develop forest edge areas [7,8].

Fortunately, there is a growing interest from both the government and the public in preserving these ecosystem services, even amid strong development pressures. To align with public sentiment and environmental conservation goals, the national government should enact planning and development laws and regulations based on forest service assessments, ensuring a balance between developmental needs and the conservation of forest edges [9].

Among the various values of forest edges, their cultural ecosystem service value, especially in terms of social benefits, has not yet been extensively explored [10]. Forest edges, often used for recreational activities, contribute significantly to physical and mental well-being [11]. The social impact of these activities is increasingly being recognized, as exposure to natural environments has been shown to alleviate various psychological challenges faced by modern society [12].

Forest edge areas are frequently used for walking, hiking, forest bathing, and camping, which promote physical health and mental well-being [13]. The presence of forest edges near urban areas provides a natural retreat for city dwellers, offering a respite from the stresses of urban life, which emphasizes the recreational value of forests [14]. Moreover, previous studies have shown that exposure to natural environments can reduce stress, anxiety, and depression, highlighting the therapeutic value of these cultural ecosystem services [15]. Thus, the cultural ecosystem service value of forest edges extends beyond their ecological functions, playing a critical role in enhancing quality of life and fostering community well-being [16].

Given this context, this study aims to investigate the economic value of the recreational and welfare services—key cultural ecosystem services—provided by forest edges in Gyeonggi-do, South Korea, where forests cover 54% of the land [17]. While previous studies have examined the ecological and environmental roles of forest edges, few have quantitatively assessed their cultural ecosystem services, particularly in terms of economic valuation. The existing literature largely focuses on ecosystem service assessments at broader spatial scales, often overlooking the localized and context-specific importance of forest edges in peri-urban landscapes. This study fills this gap by applying a monetary valuation framework to forest edges, thereby providing empirical evidence that can guide policy decisions regarding conservation and sustainable land management. By integrating economic valuation with cultural ecosystem service assessments, this research contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the multifunctionality of forest edges in highly urbanized regions.

This study is structured as follows: the next section provides a brief review of the literature on the recreational and welfare services of forest edges [18], followed by an examination of development pressures in Gyeonggi-do [17]. We then present our analytical design and describe the results, including the monetary value of the recreational and health welfare functions of forest edges in Gyeonggi-do [19]. Finally, we discuss the implications of our findings and suggest directions for future research [20].

1.1. Assessment of Recreation and Welfare as Cultural Ecosystem Services of Forests

Previous studies have demonstrated a wide range of cultural ecosystem service benefits associated with interacting with forests, and these benefits are often intuitively perceived by individuals through their personal experiences [21]. Recreational activities in forests, such as hiking, walking, and picnicking, not only provide pleasure and relaxation but also contribute significantly to the improvement of human physical and mental health and overall well-being, which are key cultural ecosystem services. The tranquility of forest environments, coupled with the physical activity involved in exploring these natural spaces, can reduce stress levels, lower blood pressure, and enhance mood [22]. However, the increasingly urbanized structure of modern society, along with the fast-paced and busy lifestyles that many people lead, has diminished our regular interaction with forests, causing us to lose sight of the importance of these natural resources as essential cultural ecosystem services in our daily lives [23].

As a result, the development and management of forest policies aimed at enhancing human well-being must go beyond mere conservation. These policies should also actively integrate and promote the cultural ecosystem service benefits of human interaction with forests, ensuring that people can easily access and enjoy these spaces. Given that the advantages of forest interaction are often subjective and personal, it is essential to develop an assessment method that can effectively quantify these benefits in monetary terms, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of their value [24].

To effectively incorporate cultural ecosystem services into decision-making, it is crucial to evaluate their value systematically. However, these services are often undervalued or overlooked in decision-making processes because they do not have explicit market prices [25]. In particular, assessing cultural ecosystem services poses unique challenges due to their non-material benefits, such as recreation, aesthetic appreciation, and mental well-being [26].

Evaluating the value of ecosystem services is crucial for understanding their contributions to human well-being and informing sustainable environmental management and policy decisions [27]. Despite these challenges, assigning a monetary value to ecosystem services is essential, as it allows policymakers and stakeholders to compare ecological benefits with economic considerations in land-use planning and resource management [28]. Monetary valuation helps to integrate ecosystem services into cost–benefit analyses, ensuring that conservation efforts and sustainable development strategies are given appropriate weight in policy discussions [29]. Without proper valuation, ecosystems may be undervalued, leading to degradation and loss of critical services that support both the environment and society [30].

Thus, CES valuation is not just an academic exercise but a necessary step toward integrating nature-based solutions into environmental policies. Various methodologies have been developed to systematically assess CES and ensure their inclusion in planning and policy frameworks.

Researchers have explored various approaches to evaluate cultural ecosystem services (CES), as their non-material benefits make traditional valuation difficult. These approaches can be broadly categorized into monetary valuation, non-monetary valuation, and participatory approaches [31]. Monetary valuation methods such as the travel cost method (TCM) and contingent valuation method (CVM) are commonly used to estimate the economic value of recreational services, particularly in protected areas and urban forests [32]. Hedonic pricing models have also been applied to measure the influence of natural amenities on property values, providing an indirect monetary estimate of CES [33].

Beyond direct monetary assessments, non-monetary and participatory approaches offer alternative means of capturing cultural values. Social media data analysis and geotagged photographs are increasingly used to map cultural ecosystem values and public perceptions of landscape aesthetics and recreational preferences [34]. Participatory mapping and GIS-based assessments further help to identify high-value CES areas through community engagement [35]. Recent research suggests integrating qualitative and quantitative methodologies to better capture the multidimensional aspects of CES, acknowledging that cultural values are often context-dependent and subjective [31,36].

Furthermore, theoretical frameworks such as the Cultural Ecosystem Services Framework [37] and the Relational Values Approach [38] have been developed to conceptualize the complex relationship between people and landscapes. These frameworks emphasize that cultural benefits are not merely instrumental or economic but are deeply tied to identity, sense of place, and community well-being [39]. By incorporating these perspectives, studies on CES can more effectively bridge ecological and social dimensions, ensuring that cultural values are appropriately recognized in decision-making processes.

Among the various domains where CES valuation is applied, tourism and public health have gained significant attention.

One key area where CES valuation plays a crucial role is recreational tourism. Typically, with the exception of national parks, many recreational activities on the edges of forests are freely accessible to the public, meaning that their economic value is not always reflected in traditional financial terms. However, if these recreational services are evaluated from a tourism standpoint, their leisure value can be quantified in monetary terms, providing a clearer picture of their economic significance as cultural ecosystem services [40].

In South Korea, the growing interest in and desire for a healthier lifestyle—spurred by factors such as work-related stress, the demands of busy city life, and a rapidly aging population—has led to an increasing demand for opportunities to relax and rejuvenate in natural environments outside the city. This trend is evident in the recent popularity of various types of camping in South Korea, ranging from backpacking and auto camping to bushcraft, picnic camping, and glamping [41,42].

Another critical perspective in CES valuation is its role in public health. Numerous studies have documented the significant health benefits of spending time in nature, particularly in forested areas, for both physical and mental well-being. Exposure to natural environments has been shown to boost immune function, reduce anxiety and depression, and enhance cognitive function [43]. Thus, CES assessment provides not only economic but also public health insights, reinforcing the need to integrate such valuations into policy frameworks.

According to Article 2 of South Korea’s Forest Culture and Recreation Act, forest healing is defined as an activity that strengthens the immune system and promotes health by utilizing various elements of nature, such as fragrance and scenery. Forest healing is a key cultural ecosystem service recognized for its ability to bring recovery and well-being to human life through the restorative power of forests. As such, incorporating CES assessments into public health strategies further underscores their importance in sustainable urban planning [44].

1.2. Development Pressure in Gyeonggido, South Korea

Gyeonggi-do consists of thirty-one municipalities, with mountainous areas covering 547,158 ha (54%), which is relatively small compared to the national mountain area ratio. However, considering that Gyeonggi-do is a province with a high proportion of urbanized municipalities, this ratio is significant. Among the municipalities of Gyeonggi-do, Gapyeong has the largest mountain area, with 69,063 ha, and the highest proportion of mountainous land, at 81.86%. These thirty-one municipalities vary in population density, geography, key industries, and transportation development. Some are densely populated, with well-developed industries and transportation networks, yet still have abundant forests. These forests are often considered for urban expansion. In particular, forests adjacent to Seoul are under greater development pressure [45].

The consequences of urban expansion into forested areas are serious. When houses or infrastructure are built in these areas, the ground can weaken, increasing the risk of landslides during heavy rains. In Gyeonggi-do, the active development of forest edges has led to several small and medium-sized landslides shortly after such developments. Over the past five years (2016–2020), there were 36,683 cases (9989.5 ha) in which forest land in Gyeonggi-do was permitted to be converted for various development purposes. In the summer of 2020, torrential rain caused 132 ha of landslide damage in Gyeonggi-do, which was 1318 times larger than the damaged area in 2019 (0.1 ha) and 18 times more than that in 2018 (7.31 ha). The landslides in 2020 resulted in significant human and property losses, with five casualties (5 killed, one injured) and damages estimated at KRW 20.978 billion. It was found that KRW 30.81 billion was required for restoration [46].

As of 2018, 26.0% of the national permits for development activities and 17.8% of the permitted area were in Gyeonggi-do. Mountain conversion in Gyeonggi-do accounts for 22.8% of the country. The primary causes of land conversion in Gyeonggi-do are housing site construction (21.7%) and factory construction (16.9%), which is about twice the national average. Based on the status of land conversion in mountainous areas in Gyeonggi-do over the past 10 years (2008–2018), the largest area (3003 ha) was permitted for conversion in 2009. Although the permitted area decreased afterward, it increased again to 2926 ha in 2016. Due to the relatively low land prices in mountainous areas, small-scale developments such as farmhouse houses, general houses, and factories are concentrated in these regions. Despite efforts and systems to control reckless development in mountainous areas, land conversion continues in Gyeonggi-do, leading to landslides and damage to the landscape [47].

The existing standards for permits for land conversion in mountainous areas and for development activities are intended to prevent reckless development, but they are somewhat incomplete and often focused on facilitating development projects. In Gyeonggi-do, to establish a reasonable management plan for disaster prevention and to protect the social values of mountainous areas, cities and counties must ensure consistency with urban planning when permitting development activities. Additionally, they should prepare reasonable location standards (elevation, average slope) to prevent reckless development in mountainous areas [48].

While detailed research, methodologies, and data for estimating the profits from various development projects have been established, there are very few studies that quantitatively analyze the value obtained when mountainous areas are preserved. Forest areas provide numerous intangible ecosystem services, but converting these into monetary values is very difficult. There are various opinions on how to analyze these values. It is necessary to estimate the profit in quantitative monetary terms to understand and compare the economic benefits of mountain area development with those of mountain area conservation [49].

In response to these concerns over land conversion, South Korea has increasingly prioritized ecosystem services as a means to mitigate environmental risks and balance development with conservation. This growing emphasis on ecosystem services is largely driven by rapid urbanization, high population density, and environmental challenges such as climate change and disaster risks. Recognizing the necessity of balancing development and conservation, particularly in urban areas where natural spaces are limited, the country has adopted a more proactive approach in land-use planning. As urban expansion continues, there is a growing awareness that forests provide essential ecosystem services, such as climate regulation, disaster prevention, and public health benefits, which are increasingly factored into land-use decisions [50]. The rapid economic growth of recent decades has led to deforestation and the fragmentation of forested areas, prompting both public and governmental concern over the loss of ecosystem services [51].

Recent policies reflect this shift in perspective, emphasizing the integration of ecosystem service assessments into urban planning and environmental regulations. The Ministry of Environment has been actively promoting nature-based solutions (NbS) as a key strategy for mitigating climate risks, enhancing biodiversity, and improving the quality of life in densely populated areas [52]. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic further highlighted the importance of urban green spaces and natural environments in supporting mental and physical health, leading to increased public demand for forest conservation and access to natural areas [53].

Given these shifts, ecosystem service valuation has emerged as a critical tool in South Korea’s land-use planning, ensuring that conservation efforts are given due weight alongside economic considerations [54]. This growing emphasis on ecosystem services is set to play a crucial role in shaping future development policies. As regions like Gyeonggi-do face mounting development pressures, prioritizing sustainable land management strategies will be essential to balancing economic growth with ecological resilience.

1.3. Changes in Gyeonggi-do Forest Management Guidelines

Gyeonggi-do is currently planning a new mountain management system that uses both elevation and average slope to determine land available for development. As a result, there are concerns among local residents that development profits may decrease due to a reduction in available land for development if this new management method is implemented. Therefore, it is essential to objectively evaluate the economic benefits that arise from the preservation of mountain areas, rather than focusing solely on the reduction in development opportunities due to the new management system being promoted [55].

In November 2020, Gyeonggi-do introduced the “Guidelines for Management and Improvement of Development Activities in Mountain Areas” to preserve forests and prevent landslides and other damages from reckless mountain development. The guidelines incorporate slope and elevation standards as criteria for development permits, with a standard slope limit of 15 degrees, applied flexibly in some areas based on forest density and regulatory grade. Elevation standards, set by regional altitude, are also adjusted based on administrative districts or topography [56].

The Gyeonggi Research Institute conducted a GIS (ArcGIS Pro 3.3.0.) analysis using the National Geographic Information Service’s numerical topographic map, DEM data, KLIS cadastral map, and land price information to assess land available for development in accordance with the strengthened standards for slope and elevation. As a result of extracting the development potential before and after the implementation of the guidelines, it was found that two counties (Gwacheon and Seongnam) showed no changes. On the other hand, despite the new standards, three cities (Gunpo, Uijeongbu, and Hanam) saw an increase in the area available for development activities and a decrease in conservation areas. In twenty-six other cities, natural disasters due to development are expected to decrease as conservation areas expand following the implementation of the guidelines (Table A1 in Appendix A).

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Study Site

The study site encompasses the forest edges of twenty-three cities and counties in Gyeonggi-do that are eligible for development under the newly implemented mountain management guidelines of Gyeonggi-do. Out of the thirty-one cities and counties in the province, only twenty-three were selected for inclusion in this study. This selection process was guided by the fact that, following the implementation of the new guidelines, there was no observed increase in conservation areas in five specific cities and counties—namely Gunpo, Uijeongbu, Hanam, Gwacheon, and Seongnam—indicating that these regions did not meet the criteria set forth for expanded conservation efforts. On the other hand, conservation areas were expanded in twenty-six other cities and counties across the province, reflecting the broader impact of the new guidelines on forest preservation.

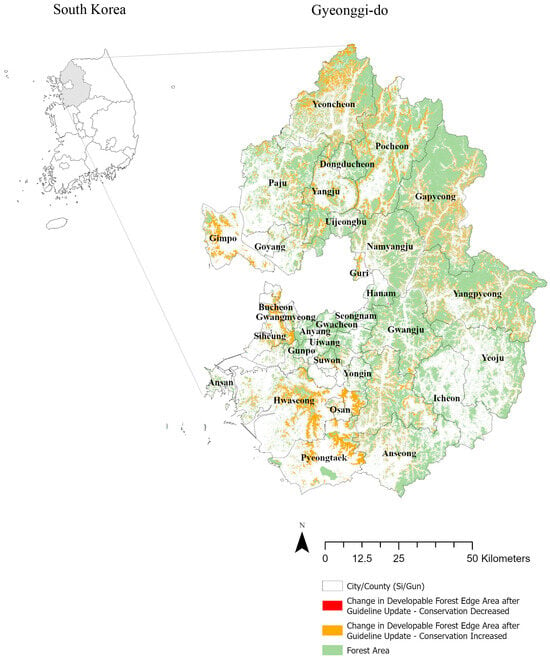

However, not all of these twenty-six areas were included in this study. Among them, three cities and counties—Gimpo, Yeoncheon, and Paju—are situated adjacent to the Military Demarcation Line, which posed significant challenges for data collection and analysis. The proximity to this highly sensitive and militarized zone introduced complexities that limited the availability and accuracy of environmental data, ultimately leading to their exclusion from the study. As a result, the final selection of twenty-three cities and counties provides a focused yet comprehensive representation of the regions where the new mountain management guidelines have influenced forest edge conservation and development. Additionally, we evaluated the areas designated by each city for conservation under the new guidelines (orange areas in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Area of developable forest edges in Gyeonggi-do (decreased under new guidelines).

2.2. Assumptions

This study was based on several key assumptions that underpin the calculation of the recreational and welfare values of forest edges. Notably, the recreational and welfare values were not calculated as a percentage of the total forest area; instead, the forest edge and the entire forest were assumed to share the same value. The reasoning behind this was as follows: first, as demonstrated in Functions 1 and 2 above, the area of the forest is not a factor in the calculations. This study assumed that the same recreational and healing effects can be obtained whether a user spends time in the forest edge or in the entire forest [57].

2.3. Evaluating Recreation Services

This study employed a calculation method based on the premise that the total travel expenses incurred by participants in forest recreation activities are directly equivalent to the monetary value of the recreational services provided by the forest edge [58]. This approach assumes that the financial outlay required for individuals to access and enjoy these natural spaces is a reasonable proxy for the economic value of the recreational benefits they derive from the experience. By assigning a monetary value to these services, we can better understand the economic significance of forest edges as recreational resources.

To accurately calculate the value of these recreation services, we collected data on the total travel cost at the county level, focusing on the expenses incurred by residents and visitors when accessing forested areas for leisure activities. Additionally, we analyzed the proportion of people who identified forests as their preferred leisure space among all available options, such as parks, urban green spaces, and other outdoor environments. These data on preferred leisure spaces were sourced from the ‘2019 National Leisure Activity Survey’ [59], a comprehensive report published by the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, which provides valuable insights into the recreational preferences of the South Korean population.

For the purpose of our analysis, the total travel cost of each county was calculated using the national average travel cost per person aged 15 and over, as provided by the Korea Tourism Organization. This figure was then adjusted to reflect the population aged 15 and over in the targeted counties, ensuring that the estimates accurately represented the local context [60]. By integrating these factors, our method provided a nuanced estimation of the recreational value of forest edges, highlighting their role as key contributors to regional economies and public well-being.

where

- = Monetary value of recreation services of forest

- = Total cost of travel at the county level

- = Ratio of people using forests for leisure (given as 0.03) [59]

- = Total cost of travel at the county level

- = Total traveling expense per capita (over 15 years old) (given as KRW 176,730.92/year) [61]

- = Population aged 15 and over in the municipality of analysis [60]

2.4. Evaluating Welfare Services

Several methods exist for estimating the value of forest welfare services, each tailored to capturing the diverse benefits that these natural environments offer to human health and well-being. One common approach involves conducting surveys of forest healing program participants, who often report significant improvements in mental and physical health following their interactions with forested areas. Similarly, surveys of hikers, who frequently engage with these natural landscapes, can provide valuable insights into the health benefits associated with regular exposure to forest environments. These surveys typically collect data on participants’ frequency of visits, types of activities engaged in, and perceived health benefits, which can then be translated into economic terms to estimate the value of forest welfare services.

In this study, the welfare services provided by forests were evaluated in monetary terms by calculating the medical expenses saved through mountaineering activities (Table 1). This approach recognizes that regular physical activity in natural settings, such as hiking in forested areas, can lead to substantial health benefits, including reduced risk of chronic diseases, improved mental health, and enhanced overall well-being. These health benefits, in turn, can result in significant cost savings by reducing the need for medical treatments and interventions.

To determine the medical cost substitution effects of forest edges, we employed a data-driven approach that utilized the ratio of mountaineering activity by county, as reported in the ‘Public Awareness Survey on Forests’ (Table 2) [62]. This survey provided detailed information on how frequently residents of different counties engage in mountaineering activities, allowing us to estimate the extent to which these activities contribute to their overall health. Additionally, we incorporated findings from a previous study [63], which provided a comprehensive analysis of the medical expense savings associated with participation in mountaineering activities (Table 1). This study offered critical data on the average reduction in medical costs for individuals who regularly engage in hiking and other forest-related activities, underscoring the significant economic value of these welfare services.

By combining these sources, we were able to quantify the welfare services of forest edges in monetary terms, offering a clearer understanding of their substantial contribution to public health and well-being. This approach not only underscores the importance of preserving and promoting access to forested areas but also provides a strong economic argument for the integration of forest welfare services into broader public health strategies.

where

- = Monetary value of welfare services of the forest

- = Hiker population by level of participation in hiking (for level )

- = Average medical cost savings by level of participation in hiking (for level ) [63]

- = Hiker population by level of participation in hiking (for level )

- = Hiking participation rate of the municipality of analysis [62]

- = Population aged 15 and over in the municipality of analysis [60]

Table 1.

Average medical cost savings by level of participation in hiking [63].

Table 1.

Average medical cost savings by level of participation in hiking [63].

| Participation in Hiking | Average Medical Cost Savings (KRW) |

|---|---|

| One or more/week | 284.6 |

| One or more/month | 90.9 |

| One or more/quarter | 39.3 |

| One or more/year | 13.6 |

| Total | 180.8 |

Table 2.

Hiking participation rate of municipality of analysis [62].

Table 2.

Hiking participation rate of municipality of analysis [62].

| Participation in Hiking | Hiking Participation Rate |

|---|---|

| One or more/week | 0.164 |

| One or more/month | 0.233 |

| One or more/quarter | 0.13 |

| One or more/year | 0.298 |

3. Results

3.1. Assessment of Recreation Services

The total recreational value of forest edge conservation areas across all cities and counties in Gyeonggi-do was estimated to be approximately KRW 50 billion (Table 3). This significant value underscores the importance of forest edge areas as vital recreational spaces for the residents of the region. Among the analyzed locations, Suwon City was found to have the highest recreational value, estimated at approximately KRW 5.9 billion (Table 3). This is likely due to Suwon’s large population and the accessibility of its forested areas, which are well utilized by residents for various recreational activities. Goyang City and Yongin City each followed closely, with recreational values estimated at approximately KRW 5 billion (Table 3). These cities are known for their dense urban environments, where forested areas provide essential spaces for outdoor activities and relaxation.

Table 3.

Monetary Value of Forest Recreation Services and Welfare Services in Increased Conservation Areas, Gyeonggi-do.

In terms of value per hectare, the analysis revealed that regions exceeding the Gyeonggi-do average of KRW 1,046,338/ha include Suwon, Goyang, Yongin, Bucheon, Ansan, Namyangju, Anyang, Siheung, Gwangju, Gwangmyeong, Osan, Icheon, Guri, Uiwang, and Dongducheon, covering 15 cities and counties in total (Table 3). These data suggest a strong correlation between population density and the per-hectare value of recreational services, highlighting the crucial role of forested areas in densely populated urban environments. The analysis further emphasizes that the higher the population in each city and county, the higher the recreation value, reflecting the demand for natural spaces in urbanized regions.

3.2. Assessment of Welfare Services

The total welfare service value of forest edge conservation areas across all cities and counties in Gyeonggi-do was estimated to be approximately KRW 701 billion (Table 3), reflecting the substantial impact of forested areas on public health and well-being. Suwon City, once again, was found to have the highest forest welfare function value at approximately KRW 81.9 billion (Table 3). This high value can be attributed to the extensive use of forested areas by Suwon’s large population for activities that promote physical and mental health, such as forest bathing and hiking.

Goyang City, with a forest welfare function value of approximately KRW 69.9 billion, and Yongin City, with approximately KRW 69.5 billion, also ranked highly in this analysis (Table 3). These cities, known for their extensive forested regions, provide significant opportunities for residents to engage in activities that enhance well-being, thereby contributing to the high valuation of forest welfare functions.

Bucheon City, with a welfare function value of about KRW 57 billion (Table 3), further illustrates the importance of urban forests in promoting health, particularly in densely populated areas where access to nature is essential for alleviating the stresses of city life. In terms of value per hectare, regions that exceed the Gyeonggi-do average of KRW 14,429,550/ha include Suwon, Goyang, Yongin, Bucheon, Ansan, Namyangju, Anyang, Siheung, Gwangju, Gwangmyeong, Osan, Icheon, Guri, Uiwang, Dongducheon, covering 15 cities and counties in total. This distribution underscores the significant health benefits that forested areas provide, particularly in urban settings where large populations can benefit from accessible green spaces (Table 3).

The forest welfare function value was also found to be closely correlated with population size, with higher population numbers in each city and county corresponding to higher welfare function values. This relationship highlights the critical role that forested areas play in supporting the health and well-being of urban populations, particularly in regions where access to natural environments is limited.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the substantial economic value of cultural ecosystem services provided by forest edges in Gyeonggi-do, South Korea. Forest edges serve as essential recreational spaces for urban residents, supporting activities such as walking, hiking, forest bathing, and camping. These activities contribute significantly to both physical and mental health, reducing stress, anxiety, and depression. While the ecological benefits of forest edges—such as biodiversity conservation and climate regulation—are widely recognized, their cultural ecosystem service functions in enhancing human well-being warrant greater attention [64].

Despite their recognized value, forest edges face increasing development pressures, particularly in densely populated regions experiencing urban expansion. As cities grow, forest edges are often targeted for development due to their accessibility and aesthetic appeal. This trend is particularly evident in Gyeonggi-do, where balancing urban development with conservation presents a growing challenge. Unregulated development not only threatens the ecological integrity of forest edges but also diminishes their capacity to provide essential cultural ecosystem services. Moreover, landscape alterations can lead to unintended consequences, such as increased vulnerability to natural disasters like landslides, resulting from soil destabilization and vegetation loss [65]. The financial and social costs of such disasters can be substantial, further emphasizing the need for sustainable land-use planning and conservation strategies [66].

This study has certain limitations due to data constraints. Distinguishing between local residents and non-local tourists would have improved the accuracy of travel cost estimations, but the absence of detailed visitor data made such differentiation difficult. Future research should incorporate more precise visitor segmentation methods, such as de facto population data, to refine travel cost estimates and improve economic valuations. Additionally, further studies should explore the broader cultural ecosystem services of forest edges, including their contributions to social cohesion, aesthetic value, and environmental education [67].

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study underscore the need for the preservation and sustainable management of forest edges, given their significant role in supporting human well-being. Protecting these areas from overdevelopment requires a comprehensive approach that integrates ecological, economic, and cultural considerations. Key strategies include establishing clear guidelines for sustainable land use, increasing public awareness of their cultural ecosystem service value, and promoting the adoption of green infrastructure solutions to minimize environmental impacts [68].

By prioritizing conservation strategies that align with both ecological sustainability and human well-being, policymakers can ensure that forest edges continue to provide vital recreational and welfare benefits. Strengthening the economic valuation of these services will offer a more robust foundation for policies that balance development and conservation, ultimately contributing to a higher quality of life for urban and peri-urban populations [69].

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, Y.C.; Writing—original draft, Y.C.; Project administration, H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the ‘Gyeonggi RE100 Platform Establishment’ project through the Gyeonggi Research Institute, funded by Gyeonggi-do, and also supported by the Sejong Science Fellowship through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT [grant number NRF2021R1C1C2014487].

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because it contains sensitive data of Gyeonggi-do. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Gyeonggi-do.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funding agencies had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Forest area in Gyeonggi-do and increased conservation area under new guidelines.

Table A1.

Forest area in Gyeonggi-do and increased conservation area under new guidelines.

| Name of City/County | Total Territory Area (ha) | Total Forest Area (ha) | Forest Ratio (%) | Increased Conservation Area Under New Guidelines (ha) | Increased Conservation Area/Total Forest Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gapyeong | 84,366 | 69,148 | 82.0 | 9659 | 14.0 |

| Goyang | 26,808 | 8515 | 31.8 | 900 | 10.6 |

| Gwacheon | 3587 | 2223 | 62.0 | N/A | N/A |

| Gwangmyeong | 3852 | 1217 | 31.6 | 182 | 15.0 |

| Gwangju | 43,106 | 27,801 | 64.5 | 1221 | 4.4 |

| Guri | 3331 | 1057 | 31.7 | 344 | 32.5 |

| Gunpo | 3641 | 1516 | 41.6 | N/A | N/A |

| Gimpo | 27,659 | 769 | 2.8 | N/A | N/A |

| Namyangju | 45,802 | 29,113 | 63.6 | 2327 | 8.0 |

| Dongducheon | 9567 | 6853 | 71.6 | 287 | 4.2 |

| Bucheon | 5344 | 788 | 14.7 | 272 | 34.5 |

| Seongnam | 14,166 | 7036 | 49.7 | N/A | N/A |

| Suwon | 12,105 | 2589 | 21.4 | 96 | 3.7 |

| Siheung | 13,579 | 3136 | 23.1 | 1187 | 37.9 |

| Ansan | 15,079 | 4374 | 29.0 | 240 | 5.5 |

| Anseong | 55,341 | 23,601 | 42.6 | 1894 | 8.0 |

| Anyang | 5847 | 2997 | 51.3 | 142 | 4.7 |

| Yangju | 31,028 | 17,284 | 55.7 | 3008 | 17.4 |

| Yangpyeong | 87,769 | 63,280 | 72.1 | 7829 | 12.4 |

| Yeoju | 60,832 | 26,228 | 43.1 | 941 | 3.6 |

| Yeoncheon | 67,601 | 4527 | 6.7 | N/A | N/A |

| Osan | 4273 | 902 | 21.1 | 116 | 12.9 |

| Yongin | 59,132 | 29,913 | 50.6 | 3612 | 12.1 |

| Uiwang | 5399 | 2929 | 54.3 | 88 | 3.0 |

| Uijeongbu | 8154 | 4688 | 57.5 | N/A | N/A |

| Icheon | 46,136 | 13,803 | 29.9 | 73 | 0.5 |

| Paju | 67,289 | 3653 | 5.4 | N/A | N/A |

| Pyeongtaek | 45,812 | 5216 | 11.4 | 2417 | 46.3 |

| Pocheon | 82,652 | 53,737 | 65.0 | 6960 | 13.0 |

| Hanam | 9303 | 4534 | 48.7 | N/A | N/A |

| Hwaseong | 68,974 | 17,230 | 25.0 | 4833 | 28.0 |

References

- Meeussen, C.; Govaert, S.; Vanneste, T.; Calders, K.; Bollmann, K.; Brunet, J.; Cousins, S.A.; Diekmann, M.; Graae, B.J.; Hedwall, P.O.; et al. Structural variation of forest edges across Europe. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 462, 117929. [Google Scholar]

- Pataki, D.E.; Alberti, M.; Cadenasso, M.L.; Felson, A.J.; McDonnell, M.J.; Pincetl, S.; Pouyat, R.V.; Setälä, H.; Whitlow, T.H. The benefits and limits of urban tree planting for environmental and human health. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 603757. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, L.; MacFarlane, D. Climate-smart forestry: Promise and risks for forests, society, and climate. PLoS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000212. [Google Scholar]

- Menge, J.H.; Magdon, P.; Wöllauer, S.; Ehbrecht, M. Impacts of forest management on stand and landscape-level microclimate heterogeneity of European beech forests. Landsc. Ecol. 2023, 38, 903–917. [Google Scholar]

- Qacami, M.; Khattabi, A.; Lahssini, S.; Rifai, N.; Meliho, M. Land-cover/land-use change dynamics modeling based on land change modeler. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2023, 70, 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yang, Z. Challenges, experience, and prospects of urban renewal in high-density cities: A review for Hong Kong. Land 2022, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Kwak, H.; Choi, S.; Kim, M.; Lim, C.H.; Lee, W.K.; Chae, Y. Assessing vulnerability of forests to climate change in South Korea. J. For. Res. 2016, 27, 489–503. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C.S.; Jung, S.; Lim, B.S.; Kim, A.R.; Lim, C.H.; Lee, H. Forest decline under progress in the urban forest of Seoul, central Korea. In Forest Degradation Around the World; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Stubenrauch, J.; Ekardt, F.; Hagemann, K.; Garske, B. Forest governance: Overcoming trade-offs between land-use pressures, climate, and biodiversity protection. In Global Forest Governance and Climate Change; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, L. Deforestation and Climate Change; Climate Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Green, L.W.; Richard, L.; Potvin, L. Ecological foundations of health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 270–281. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, T.W. The global tree restoration potential. Science 2019, 365, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Velarde, M.D.; Fry, G.; Tveit, M. Health effects of viewing landscapes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, I.; Sbihi, H.; Davis, Z.; Brauer, M.; Czekajlo, A.; Davies, H.W.; Gergel, S.; Guhn, M.; Jerrett, M.; Koehoorn, M.; et al. The influence of early-life residential exposure to different vegetation types and paved surfaces on early childhood development: A population-based birth cohort study. Environ. Int. 2022, 163, 107196. [Google Scholar]

- Paredes-Céspedes, D.M.; Vélez, N.; Parada-López, A.; Toloza-Pérez, Y.G.; Téllez, E.M.; Portilla, C.; González, C.; Blandón, L.; Santacruz, J.C.; Malagón-Rojas, J. The Effects of Nature Exposure Therapies on Stress, Depression, and Anxiety Levels: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 609–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astell-Burt, T.; Feng, X. Association of urban green space with mental health and general health among adults in Australia. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e198209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gyeonggi Global. Gyeonggi Province Accelerates Recreational Forest Amenity Expansion to Beat COVID Blues; Gyeonggi Global: Suwon City, Republic of Korea, 2021.

- Cupul-Magaña, A.L.; Rodríguez-Troncoso, A.P. Tourist carrying capacity at Islas Marietas National Park: An essential tool to protect the coral community. Appl. Geogr. 2017, 88, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Eggers, J.; Lindhagen, A.; Lind, T.; Lämås, T.; Öhman, K. Balancing landscape-level forest management between recreation and wood production. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 33, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Elands, B.H.M.; van Marwijk, R.B.M. Policy and management for forest and nature-based recreation and tourism. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 19, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Rathmann, J. Introduction: Forests as a recreation area. In Forest as a Health Resource; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, M.; Výbošťok, J.; Önkal, D.; Lamatungga, K.E.; Tamatam, D.; Marcineková, L.; Pichler, V. Increased appreciation of forests and their restorative effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ambio 2021, 50, 810–823. [Google Scholar]

- Labib, S.; Lindley, S.; Huck, J.J.; Hadfield, C. Nature engagement, health, and well-being in times of crisis: The role of green and blue spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 64, 127375. [Google Scholar]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Anderson, S.; Sutton, P. The future value of ecosystem services: Global scenarios and national implications. Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 26, 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; de Groot, R.; Sutton, P.; van der Ploeg, S.; Anderson, S.J.; Kubiszewski, I.; Farber, S.; Turner, R.K. Changes in the Global Value of Ecosystem Services. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 26, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heal, G. Valuing Ecosystem Services. Ecosystems 2000, 3, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Valuing Ecosystem Services: Toward Better Environmental Decision-Making; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Monetary Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Assets for Ecosystem Accounting; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, R.; Brander, L.; van der Ploeg, S.; Costanza, R.; Bernard, F.; Braat, L.; Christie, M.; Crossman, N.; Ghermandi, A.; Hein, L.; et al. Global Estimates of the Value of Ecosystems and Their Services in Monetary Units. Ecosyst. Serv. 2012, 1, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liquete, C.; Piroddi, C.; Drakou, E.G.; Gurney, L.; Katsanevakis, S.; Charef, A.; Egoh, B. Current Status and Future Prospects for the Assessment of Marine and Coastal Ecosystem Services: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e67737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.; Satterfield, T.; Goldstein, J. Rethinking Ecosystem Services to Better Address and Navigate Cultural Values. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 74, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, L.M.; Koetse, M.J. The Value of Urban Open Space: Meta-Analyses of Contingent Valuation and Hedonic Pricing Results. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 2763–2773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, H.A.; Polasky, S. The Value of Views and Open Space: Estimates from a Hedonic Pricing Model for Ramsey County, Minnesota, USA. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, D.R.; Tunçer, B. Using Geotagged Social Media Data to Infer Cultural Ecosystem Values in Urban Green Spaces. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 221, 104351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Nieto, A.P.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Castro, A.J.; Rodríguez, J.P.; Cabello, J. Ecosystem Services and Social-Ecological Resilience in Transhumance Cultural Landscapes: Learning from the Past, Looking for the Future. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, A.; Slotow, R.; Burns, J.K.; Di Minin, E. The Ecosystem Service of Sense of Place: Benefits for Human Well-Being and Biodiversity Conservation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, R.; Church, A.; Winter, M. Conceptualising Cultural Ecosystem Services: A Novel Framework for Research and Critical Engagement. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Gould, R.K.; Pascual, U. Relational Values: What Are They, and What’s the Fuss About? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 21, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Giusti, M.; Barthel, S. An Embodied Perspective on the Co-Production of Cultural Ecosystem Services: Toward Embodied Ecosystems. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2013, 56, 695–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heagney, E.C.; Rose, J.M.; Ardeshiri, A.; Kovac, M. The economic value of tourism and recreation across a large protected area network. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expat Guide Korea. All You Need to Know About Camping in Korea; Expat Guide Korea: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- KoreaTravelPost. 10 Best Camping and Glamping Sites in Korea; KoreaTravelPost: Naju-si, Republic of Korea, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, B.; Lee, K.J.; Zaslawski, C.; Yeung, A.; Rosenthal, D. Health and well-being benefits of spending time in forests: A systematic review. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2017, 22, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Yoon, H.; Kim, D. Where do people spend their leisure time on dusty days? Application of spatiotemporal behavioral responses to particulate matter pollution. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2019, 63, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britannica. Gyeonggi|South Korea, Map, History, & Geography; Britannica: Chicago, IL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk, U.; Froude, M.J.; Petley, D.N. How climate change and unplanned urban sprawl bring more landslides. Nature 2022, 608, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Regeneration. Gyeonggi Housing & Urban Development Corporation; GH Corporation: Kent, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.H.; Lee, S.R.; Ok, J.A.; Lim, J.H.; Lee, B.R. Current status of unplanned development in Gyeonggi Province and institutional improvement measures. Policy Res. 2020, 1, 1–144. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L.; Peng, J.; Liu, Y.X. Urbanization impact on landscape patterns in Beijing City, China: A spatial heterogeneity perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 82, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Lee, Y.; Seo, K. Ecosystem Services and Land-Use Planning: Challenges and Opportunities in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3569. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Son, W. Forest Fragmentation and Ecosystem Service Loss: A Case Study in Metropolitan Seoul. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Han, J.; Lee, T. Nature-Based Solutions in South Korean Environmental Policy: An Emerging Approach to Climate Resilience. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 134, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Kim, S.; Park, J. The Impact of Urban Green Spaces on Mental Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic in South Korea. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2023, 66, 874–892. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, E.; Jang, H.; Lee, C. Quantifying the Economic Benefits of Ecosystem Services in South Korea: A Policy-Driven Approach. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.; Gu, F.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Shi, C.; Fan, Z. Divergent growth between spruce and fir at alpine treelines on the east edge of the Tibetan Plateau in response to recent climate warming. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 276–277, 107631. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Seo, J.W. Evaluating forest conservation policies and their effectiveness in Gyeonggi-do. Environ. Res. 2021, 198, 111004. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, R.H.; Kaplan, R. People needs in the urban landscape: Analysis of landscape and urban planning contributions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.H.; Kretinin, V.M.; Marquis, R.J.; McPherson, E.G.; McPherson, E.G.; Nagy, K.A.; Royama, T.; Rytkönen, S.; Williams, J.R.; Numamoto, S.; et al. Valuation of nonmarket forest resources. J. Korean Inst. For. Recreat. 2012, 16, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. National Leisure Activity Survey; Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2019.

- Statistics Korea. Population Census; Statistics Korea: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2019.

- Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism. National Travel Survey; Ministry of Culture, Sports, and Tourism: Sejong-si, Republic of Korea, 2019.

- Korea Forest Service. Public Awareness Survey on Forests; Korea Forest Service: Daejeon, Republic of Korea, 2015.

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Li, N. The effects of forest therapy on medical expenses reduction. J. Korean Women’s Econ. Assoc. 2015, 12, 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Derks, J.; Giessen, L.; Winkel, G. COVID-19-induced visitor boom reveals the importance of forests as critical infrastructure. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102253. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D.; Clark, M.; Williams, D.R.; Kimmel, K.; Polasky, S.; Packer, C. Future threats to biodiversity and pathways to their prevention. Nature 2017, 546, 73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Geldmann, J.; Barnes, M.; Coad, L.; Craigie, I.D.; Hockings, M.; Burgess, N.D. Human pressures compromise the effectiveness of protected areas. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 601. [Google Scholar]

- Krzeminska, D.M.; Capobianco, V.; Mickovski, S.B. The role of vegetation in landslide risk mitigation: Insights from slope stability modeling. Landslides 2019, 16, 703–717. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, P.G.; Slay, C.M.; Harris, N.L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 2018, 361, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grizzetti, B.; Liquete, C.; Pistocchi, A.; Vigiak, O.; Zulian, G.; Bouraoui, F.; De Roo, A.; Cardoso, A.C. Relationship between ecological condition and ecosystem services in European rivers, lakes, and coastal waters. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 671, 452–465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).