Abstract

This study investigates the drivers of green production practices among forest-cultivated ginseng growers in Jilin Province, China, by integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework. Based on survey data from 369 households in the major production regions of Tonghua, Baishan, and Yanbian areas, an Ordered Probit model and a Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) algorithm are employed for cross-validation. The results indicate that growers’ cognitive traits (awareness of green production standards and ecological/quality safety) and willingness (acceptance of price premiums for green products) are the most stable and critical drivers. Policy incentives (e.g., certification subsidies and outreach) not only directly promote green practices but also exhibit synergistic effects through interactions with resource endowments and psychological cognition. Regional heterogeneity is evident: Tonghua shows policy–market co-drive, Baishan is dominated by ecological constraints and safeguard policies, while Yanbian relies more on education and individual resources. Accordingly, this study proposes a differentiated policy system based on diagnosis–intervention–evaluation to support the high-quality development of forest-cultivated ginseng industry and ecological-economic synergies.

1. Introduction

As a core production area in China, Jilin Province accounts for 60% of the nation’s total ginseng output and 40% of the global market share. Its comprehensive industrial product value surpassed RMB 800 billion in 2024, establishing itself as a pivotal pillar for regional agricultural modernization and rural revitalization [1]. The forest-cultivated ginseng industry, leveraging the unique forest ecosystem of the Changbai Mountains, is transitioning from the traditional “clearing forests for planting” model towards a green development paradigm of “co-cultivation and ecological symbiosis” [2]. By 2023, the total cultivation area for forest-grown ginseng in Jilin reached 1.165 million mu, with an annual output nearing RMB 10 billion, forming characteristic industrial clusters in regions like Tonghua, Baishan, and Yanbian. This transformation exemplifies the eco-economic principle that “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets” and represents a key pathway for realizing the sustainable utilization of forest land resources under Jilin’s Forest Granary strategy [3].

However, the large-scale diffusion of green production practices (GPB) for under-forest ginseng remains an uphill battle [4]. Empirically, the crop’s 15-year maturation cycle, farmers’ limited awareness of green technologies, tepid responses to policy incentives, high market volatility, shrinking forestland availability, and declining seed quality jointly stifle the spread of sustainable systems [5,6]. Theoretically, the literature has concentrated on macro-level industrial policies or technical optimization, leaving the micro-level drivers of farmer behavior under-examined; in particular, multi-factor interactions and non-linear pathways have been largely overlooked [7,8]. Ajzen’s (1991) theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) effectively captures how psychological motives—attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—shape behavioral intention, yet the framework privileges the micro-cognitive domain and offers limited traction on external contingencies such as policy signals or market conditions [9,10]. Conversely, the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework advanced by Tornatzky et al. (1990) systematically maps the contextual drivers of technology adoption, but it is thin on individual cognition and decision psychology [11]. Recent attempts to integrate the two lenses have not, to date, been extended to green agriculture—least of all to an eco-sensitive, forest-dependent sector such as under-forest ginseng [12,13,14]. A coherent account of how “psychological motives + external circumstances” jointly trigger GPB, including the interactive and non-linear mechanics at work, is still missing.

In practices observed in Tonghua and Baishan, the adoption of green technologies by ginseng farmers is influenced not only by their own cognition of ecological value but also highly dependent on external conditions such as policy subsidies and market premiums. To bridge this research gap, this study innovatively integrates the TPB and TOE frameworks to construct a two-dimensional analytical model encompassing Psychological Motivation-External Environment. Based on survey data from 369 households in Jilin’s major production regions (Tonghua, Baishan, Yanbian), we comprehensively employ an Ordered Probit model and the Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) algorithm to identify key driving factors of GPB from these dual perspectives. The research focuses on examining the independent and synergistic effects of multiple factors, including policy incentives, market conditions, individual cognition, and resource endowment, and analyzes the heterogeneous driving patterns across the three main production areas. Ultimately, it aims to construct a differentiated policy system integrating “diagnosis–intervention–evaluation,” reveal the complex driving mechanisms behind GPB, and provide practical references for the ecological value transformation of characteristic forest and agricultural products globally.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Foundational Role of Resource Endowment

Resource endowment serves as the material foundation and capacity prerequisite for farmers’ green production behavior (GPB), encompassing multiple dimensions such as natural, economic, human, and social resources [15]. At the micro-level, individual characteristics—including age, education level, and social roles—determine farmers’ learning ability and risk perception regarding green technologies [16]. Household-level conditions, such as total income and the proportion of agricultural income (particularly from forest-cultivated ginseng), directly reflect financial capacity and specialization motivation for green production investments. Natural conditions like soil fertility and location within ecological protection zones constitute ecological adaptability and external constraints. Empirical studies confirm that heterogeneity in resource endowment leads to significant differences in farmers’ willingness and capability to adopt green technologies, with well-endowed farmers demonstrating stronger conditions and motivation for GPB adoption [17,18].

2.2. Psychological Driving Effects of Cognition and Intention

Cognitive traits and behavioral intention are core constructs of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), collectively shaping farmers’ behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [9]. Specifically, farmers’ cognition of green production standards, understanding of ecological benefits, and mastery of relevant technologies directly influence their value recognition and self-efficacy toward GPB [19]. Behavioral intention acts as a key psychological bridge translating cognition into behavioral inclination. Research indicates that farmers with higher environmental literacy and stronger value recognition of green production are more likely to convert positive cognition into actual adoption intention [20,21].

2.3. External Catalysis and Compensation Effects of Policy Incentives

As a critical environmental factor in the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, policy incentives influence farmers’ decisions through three mechanisms: resource empowerment, information dissemination, and supervisory constraints [22,23]. Policy interventions not only directly reduce economic costs and market risks of green production but also indirectly promote behavioral transformation by enhancing cognitive levels and strengthening social norms (e.g., demonstration effects and community supervision). Particularly in industries with long cycles and high ecological dependence like forest-cultivated ginseng, policy incentives often exert a kick-start effect, helping farmers overcome initial investment barriers [24].

2.4. Interactive Enhancement Effects Between Policy Incentives and Resources

The effectiveness of policy incentives interacts with farmers’ intrinsic resource conditions, generating synergistic or heterogeneous effects [25,26]. For farmers with relatively weak resource endowment (e.g., low income, poor soil conditions, or low education), targeted policy interventions (e.g., precision subsidies, technical guidance) exhibit more significant marginal effects, effectively compensating for resource shortages via a compensation effect. Conversely, well-endowed farmers are better able to transform policy support into technological upgrades and scale expansion, yielding a gain effect. Identifying this interaction mechanism helps reveal the root of policy effect heterogeneity, providing a basis for differentiated policy design [27,28].

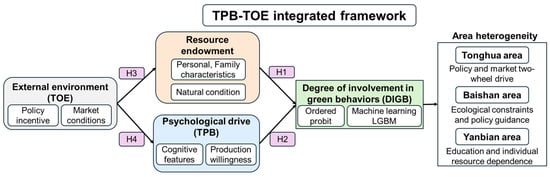

This study integrates TPB and TOE framework to construct a systematic analytical framework (Figure 1) encompassing intrinsic psychological motivation (cognition, intention), resource conditions (individual, household, natural), and external environment (policy incentives). This framework elucidates the driving mechanisms of GPB among forest-cultivated ginseng growers. Based on this framework, core research hypotheses are proposed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

TPB-TOE integrated framework.

Table 1.

Research hypotheses and corresponding variables.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Source and Processing

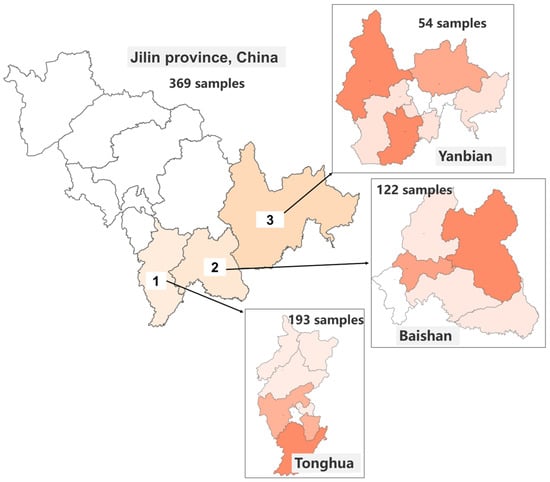

Geographically, Tonghua and Baishan are located in southeastern Jilin Province, while Yanbian is in the east. These three cities form a fan-shaped area covering the core region of the Changbai Mountains, which constitutes the main production area for forest-cultivated ginseng in Jilin Province, accounting for over 80% of the total cultivation area (Figure 2). Sampling from these three regions ensures coverage of diverse planting environments with varying altitudes and slopes within the Changbai Mountains, thereby avoiding potential biases caused by specific local geographical features. A stratified random sampling method was employed to conduct a questionnaire survey and government department interviews among forest-cultivated ginseng growers in Baishan, Tonghua, and Yanbian between July and September 2025. The sampling frame was stratified by city, and the sample size for each stratum was allocated disproportionally based on its respective forest-cultivated ginseng industry scale (primarily referring to the cultivation area) to ensure adequate representation from larger production regions. A total of 402 questionnaires were distributed, with 369 valid responses collected, yielding an effective response rate of 91.8%. The sample encompassed growers of different scales (ranging from several dozen to tens of thousands of mu). The valid responses from Tonghua, Baishan, and Yanbian were 193, 122, and 54, respectively, with high effective response rates of 91.0%, 92.4%, and 93.1% achieved in each stratum.

Figure 2.

Geographic locations and quantity distribution of sample collection.

The questionnaire used in this study was developed by the research team based on a literature review and expert consultations [4,5,15,26]. It covers seven modules: basic grower information, household economy, natural resource endowment, policy perception, technical cognition, market conditions, and the adoption of Green Production Behavior (GPB). Additionally, to supplement and validate the survey data, interviews were conducted with relevant local government departments (e.g., Forestry Bureau, Agriculture and Rural Affairs Bureau), obtaining policy documents and industry reports. The measurement of GPB adoption is based on the characteristics of forest-cultivated ginseng production, examined across three dimensions: pre-production (forest land preparation), in-production (planting management), and post-production (recycling and treatment). Respondents were presented with six specific green production practices to select from. Multicollinearity was assessed using the Pearson correlation coefficient. The formula for the Pearson correlation coefficient R is as follows:

where xi and yi are the individual data points, and are the sample means, and n is the sample size.

3.2. Econometric Model Specification

This study employs an Ordered Probit model to analyze the determinants of green production behavior (GPB) adoption among forest-cultivated ginseng growers. The model is appropriate since the dependent variable, GPB participation intensity, is an ordinal measure ranging from 0 to 6. The core concept is a latent variable framework, where the observed ordinal outcome is assumed to be determined by an unobserved, continuous latent variable (y*), The latent variable model is specified as follows (Liao et al., 2025 [4]):

where Xi is a vector of observed explanatory variables (e.g., individual, household, and policy characteristics), β is a vector of parameters to be estimated, and the error term ϵi is assumed to follow a standard normal distribution, ϵi ∼ N (0, 1). The relationship between the unobserved latent variable y* and the observed ordinal outcome yi is defined by a set of threshold parameters (μ1 < μ2 < … < μ6). The observation mechanism is:

Consequently, the probability that household i exhibits a GPB participation level j is given by:

where Φ(⋅) is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the standard normal distribution. The model parameters (β and μ) are estimated using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method.

To assess the robustness of the Ordered Probit model results, an Ordered Logit model is also estimated. The core structure of the Ordered Logit model is identical, but it assumes the error term ϵi follows a logistic distribution, using the logistic CDF [29,30]:

The model parameters (β and μ) are estimated using the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method. The likelihood function is derived from the probabilities specified in Equation (3). The robustness of the baseline results is supported if the signs and statistical significance levels of the key explanatory variables remain consistent across both the Ordered Probit and Ordered Logit specifications. Regional heterogeneity in driving mechanisms is examined by estimating the Ordered Probit model separately for sub-samples from the three major production areas: Yanbian, Baishan, and Tonghua. Differences in the estimated coefficients (β) across these groups indicate region-specific drivers. All econometric analyses are conducted using Stata 17.0 software. The oprobit command is used for the Ordered Probit model, and the ologit command can be applied for the Ordered Logit model.

3.3. Machine Learning Predictive Modeling

To capture complex nonlinear relationships and interaction effects among variables, this study establishes machine learning prediction models. The algorithm selection is based on an ensemble learning framework, comparing four algorithms: Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGB), Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), and Random Forest (RF). The dataset was randomly partitioned into a training set (80%, 295 samples) and a test set (20%, 74 samples) with a random seed of 0 to ensure reproducibility. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using Grid Search, focusing on key parameters: n_estimators (100–500), max_depth (3–10), learning_rate (0.01–0.3), and subsample (0.6–1.0). The models’ performance was comprehensively evaluated using Accuracy and F1-score. The calculation formulas are as follows [31,32]:

To investigate the interactive effects of multiple features, the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) algorithm, based on game theory, was employed to analyze the interactions between the dependent variable and predictors [33]. The SHAP algorithm adopts an additive feature attribution method to approximate the output of a “black-box” model as a linear sum of functions of the input variables, providing explanations for each individual prediction, as shown in Equation (9) [31,34]:

where f(x) is the prediction, ∅0 is a constant term (typically the mean prediction, i.e., the expected value of the model output), M is the number of input features, and ∅ij(x) is the SHAP value representing the contribution of the i-th input feature for the specific instance j. The contribution of each feature is weighted and summed over all possible subsets of input features, as detailed in Equation (10) [35,36]:

Here, F denotes the complete set of all features, S is a subset of F excluding feature i, is the prediction for instance xusing only the feature subset S, and is the prediction when feature i is added to the subset S. The difference quantifies the marginal contribution of the i-th input feature to the prediction for the subset S, while is the corresponding weighting factor that accounts for the number of ways the subset can be formed. All analyses were conducted using Python 3.9. The scikit-learn library was used for data preprocessing, model training, and evaluation, while the SHAP library was utilized for model interpretability analysis.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Data Description and Visualization Analysis

Prior to data analysis, this section defines the core variables involved in the study and provides their descriptive statistics, as shown in Table 2. The explained variable is the degree of green production behavior participation (DIGB) among forest-cultivated ginseng growers. This variable is an ordered categorical measure. It is operationalized by summing the number of six specific green production practices adopted by growers, based on survey responses. These practices include: adopting biological control techniques, using non-hazardous fertilizers, implementing crop rotation/fallow techniques, practicing ecological harvesting, recycling waste, and protecting forest flora and fauna. DIGB ranges from 0 to 6, corresponding to the adoption of “none” to “all six” practices, with higher values indicating greater participation intensity. The sample mean is 3.29 (standard deviation = 1.46), initially indicating a moderate overall level of green production participation among the growers.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

The explanatory variables, grounded in the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and related research, are categorized into six dimensions, comprising 17 characteristic variables. Their descriptive statistics are as follows:

(1) Individual Characteristics: This dimension includes gender, age, education level, and social role. The average age of the sampled growers is approximately 49.5, and the proportion of males is 41.8%. The education level is generally not high. The distribution of social roles indicates that a significant portion of the sampled growers is enterprise-contracted.

(2) Household Characteristics: These variables encompass annual total household income and the proportion of income derived from forest-cultivated ginseng. Both metrics exhibit considerable variation, reflecting the diverse economic conditions and income structures among the farming households.

(3) Natural Conditions: This category includes planting area, self-assessed soil fertility, and whether the plot is located within an ecological protection area. The planting area is predominantly small to medium scale. The self-assessed soil fertility is relatively high, and the majority of the sample plots are not located within ecological protection areas.

(4) Cognitive Traits: This dimension consists of awareness of green production standards, awareness of ecological and quality safety, understanding of green production techniques, and perception of the industry’s importance to ecological protection. Growers’ awareness of green production standards, ecological quality, safety, and green techniques shows considerable potential for improvement, with mean scores between 2.5 and 3.0. However, their recognition of the ecological importance of the forest-cultivated ginseng industry is very high.

(5) Production Intention: This includes willingness to accept a price premium for green products and willingness to subsidize the purchase of agricultural inputs. Regarding production intention, growers demonstrate a positive willingness to accept price premiums for green products and to receive subsidies for agricultural inputs.

(6) Policy and Market Environment: These variables encompass perceived government supervision, receipt of product certification subsidies, the degree of policy propaganda implementation, and the strictness of market management. In terms of policy implementation, the coverage of policy propaganda and market management is relatively high, while the reach of government supervision and product certification subsidies is comparatively limited.

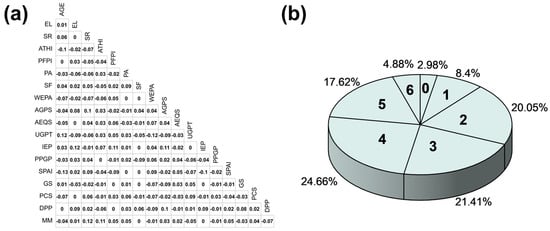

To assess potential multicollinearity in the model, the Pearson correlation coefficients among all explanatory variables were calculated. The results show that the maximum absolute value of the coefficients is below 0.2, confirming good independence among the variables (Figure 3a). Regarding the distribution of the explained variable (degree of green production behavior participation), frequency statistics reveal that the vast majority of samples (approximately 84%) fall within the range of 2 to 5. This indicates that the overall participation level of the respondents is at a medium level (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Correlation analysis and frequency statistics: (a) Pearson correlation coefficients; (b) frequency distribution of DIGB.

4.2. Econometric Results

The Ordered Probit model was employed to estimate the determinants of growers’ Green Production Behavior (GPB). The model demonstrates a satisfactory overall fit. The Likelihood Ratio (LR) test yields a chi-square statistic of 112.45 (p < 0.001) with 18 degrees of freedom, indicating that the set of independent variables jointly has significant explanatory power for the dependent variable. The pseudo-R2 value is 0.126, which is considered acceptable within the context of social science empirical research. The estimated threshold parameters (μ) range from −2.341 to 3.215 and are all statistically significant (p < 0.01), which aligns with the theoretical expectations of an ordered probability model and supports the rationality of the dependent variable’s categorization.

The coefficient estimates from the Ordered Probit model are presented in Table 3. A notable finding in the analysis of individual characteristics is the marginally significant negative effect of grower age (β = −0.021, p < 0.1). This stands in contrast to the positive influence of education level (β = 0.152, p < 0.05) and renders age as the only variable across all examined dimensions to exhibit a potentially inhibitory effect on the adoption of GPB. This unique negative relationship can be interpreted through several complementary lenses. From a behavioral economics perspective, it may reflect a higher degree of risk aversion and stronger path dependency among older growers, who might perceive the transition from established conventional methods to unfamiliar green techniques as economically and operationally risky. Conversely, younger operators are likely more adaptable and receptive to new knowledge, aligning with diffusion of innovation theory, which posits that earlier adopters are often characterized by a younger demographic. Regarding resource foundations, the proportion of income derived from forest-cultivated ginseng (β = 0.117, p < 0.05) reaches statistical significance, indicating that economic dependence on this crop serves as a key driver for behavioral change. Furthermore, being located within an ecological protection area (β = 0.185, p < 0.05) exhibits a positive influence, implying a synergistic effect between regulatory zoning and pro-environmental behavior.

Table 3.

Estimation results of the ordered probit and ordered logit models.

Cognitive traits and behavioral intentions demonstrate the most substantial impacts on GPB adoption. Specifically, awareness of green production standards (β = 0.212, p < 0.01) and awareness of ecological and quality safety (β = 0.276, p < 0.05) show strongly positive coefficients, underscoring that enhancing growers’ cognitions significantly increases adoption probability. This is reinforced by the significant effects of understanding green production techniques (β = 0.194, p < 0.05) and perceiving the industry’s ecological importance (β = 0.228, p < 0.05), emphasizing the critical role of knowledge dissemination. In terms of production intention, willingness to accept a price premium for green products (β = 0.279, p < 0.01) and willingness to subsidize agricultural inputs (β = 0.134, p < 0.1) have significant positive coefficients, confirming that economic incentives effectively encourage the shift towards green production. For policy implementation, product certification subsidy (β = 0.156, p < 0.1) shows preliminary positive effects, suggesting its potential as a policy tool. The Ordered Probit results support Hypotheses H1 and H2, while the verification of H3 and H4 requires subsequent interaction effect analysis.

To assess the robustness of the econometric model, the results of the Ordered Logit model are compared with those of the previously employed Ordered Probit model (Table 3). The pseudo-R2 values of the two models are very close (Ordered Probit: 0.126; Ordered Logit: 0.121), indicating nearly identical explanatory power for the dependent variable. The likelihood ratio chi-square statistics are also highly similar (Ordered Probit: 112.45; Ordered Logit: 126.62), further confirming no significant difference in the overall goodness-of-fit between the two models to the data. The coefficients of the Ordered Logit model, based on the logistic distribution, allow for an intuitive interpretation using Odds Ratios. For instance, the Odds Ratio for Awareness of Green Production Standards (AGPS) is 1.718. This means that for each one-unit increase in this awareness, the odds of a grower exhibiting a higher level of GPB become 1.718 times greater. The estimation results from the Ordered Logit and Ordered Probit models are highly consistent in terms of the signs of the coefficients, statistical significance levels, and overall model fit. This robustly confirms that the study’s core findings—regarding the impact of various factors on growers’ GPB—are reliable, as they are strongly supported by two distinct modeling approaches.

An analysis of regional heterogeneity was conducted for the sub-samples of forest-cultivated ginseng growers from Tonghua, Baishan, and Yanbian using the Ordered Probit model. The results, presented in Table 4, reveal significant differences in the drivers of GPB across these regions, reflecting their distinct industrial foundations, policy environments, and developmental stages. Tonghua Region: Policy–Market Co-Driven Maturity Model. As the core ginseng production area in Jilin Province, Tonghua boasts a solid industrial foundation and a complete industrial chain, with well-developed market mechanisms and policy support systems. This mature institutional environment explains why cognitive variables and market incentives exhibit stronger effects here. The significant positive impact of Understanding of Green Production Techniques (UGPT: β = 0.223, p < 0.05) and Willingness to Accept a Price Premium for Green Products (PPGP: β = 0.226, p < 0.05) indicates that Tonghua growers have transcended basic adoption barriers and can effectively translate technical knowledge and market expectations into concrete practices. The region’s established certification systems, premium markets, and technical support networks create an environment where knowledge and economic incentives directly drive behavioral change. The results show that cognitive traits (Awareness of Green Production Standards, AGPS: β = 0.398, p < 0.01; Awareness of Ecological & Quality Safety, AEQS: β = 0.351, p < 0.01) and policy implementation (Product Certification Subsidy, PCS: β = 0.312, p < 0.01; Government Supervision, GS: β = 0.203, p < 0.1) are significant factors. Furthermore, the proportion of income from forest-grown ginseng (PFPI: β = 0.187, p < 0.05) is most significant here, indicating high economic dependence on the industry and stronger motivation to adopt green technologies for long-term benefits.

Table 4.

Regional heterogeneity analysis results.

Baishan Region: Ecological Constraint-Safeguard Policy Led Transition Model. This region has a significant proportion of land within ecological protection areas, leading to stricter environmental regulations. The analysis results directly reflect this characteristic. Being located within an Ecological Protection Area (WEPA: β = 0.362, p < 0.05) is the most significant variable with the highest coefficient, highlighting the rigid constraint of ecological red lines. Additionally, the influence of Annual Total Household Income (ATHI: β = 0.193, p < 0.1) becomes significant, suggesting that household economic capital is an important basis for risk resistance and new technology adoption during industrial transition. In contrast, the effects of cognitive and policy variables, while present, are weaker than in Tonghua, indicating that the development model is still in a phase of adjustment and transition.

Yanbian Region: preliminary insights into an education and individual resource-oriented development path. It is important to note that the analysis for the Yanbian region is based on a relatively small sub-sample (n = 54), which limits the statistical power of the econometric model and necessitates a cautious, exploratory interpretation of the results. Within this context, the patterns observed may tentatively suggest that in this developing industrial area, internal resources at the individual and household levels could play a pivotal role in decision-making. Among the factors examined, the influence of Education Level (EL: β = 0.284, p < 0.1) appears most prominent, potentially indicating that knowledge capacity is a key element for overcoming technical and managerial challenges at this stage of growth. Similarly, the coefficient for Planting Area (PA: β = 0.234), while not achieving statistical significance, is relatively large and might hint at the emerging relevance of scale management. In contrast, variables associated with the external environment, such as policy implementation (e.g., DPP, MM) and market cognition (e.g., PPGP), were not significant in the model. This could reflect that institutional support and market mechanisms are still evolving in Yanbian, leading growers to rely more heavily on their own resource endowment. Therefore, these findings should be viewed as indicative rather than conclusive, offering valuable preliminary clues for understanding the distinctive drivers in Yanbian and highlighting the need for future research with a larger sample to validate these patterns.

4.3. Machine Learning Model Results

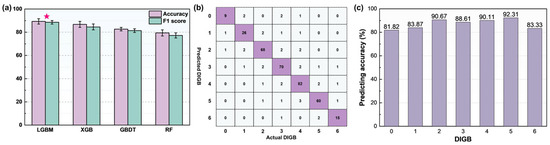

The predictive accuracy of different machine learning algorithms is shown in Figure 4a. On the full dataset, the Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM) model achieved the best balance between predictive accuracy and computational efficiency, with a mean accuracy of 89.32% and an F1-score of 88.56%, outperforming other comparative algorithms by all below 88%. Leveraging histogram-based algorithm optimization, LGBM significantly enhanced training speed while maintaining high accuracy, processing the dataset of this scale in only 0.85 s, which is considerably faster than other models. The confusion matrix (Figure 4b) shows the number of correctly classified samples on its diagonal. The subsequent calculation of per-class accuracy (Figure 4c) revealed that the highest prediction accuracy (reaching 90%) was achieved for behavior categories where DIGB was 2 and 4. This indicates that the high-accuracy classification model built on LGBM provides reliable support for subsequent analysis.

Figure 4.

Machine learning model results: (a) predictive accuracy of different algorithms (The star represents the optimal model); (b) confusion matrix of the LGBM model (Purple represents that the classification prediction is completely correct); (c) per-class accuracy.

After systematic optimization via the grid search method, the optimal hyperparameter combination for the LGBM model was determined, as presented in Table 5. The number of trees (n_estimators) and the maximum tree depth (max_depth) were identified as the two parameters most significantly impacting model performance, jointly determining the model’s complexity and learning capacity. Furthermore, hyperparameters including the learning rate (learning_rate), maximum number of leaves (num_leaves), and the proportion of training data used (subsample) were finely tuned. This careful adjustment ensured the model adequately learned the data characteristics while effectively preventing overfitting, thereby achieving the highest current prediction accuracy on the test set. This parameter set strikes the best balance among accuracy, generalization capability, and computational efficiency.

Table 5.

The optimal hyperparameters of LGBM.

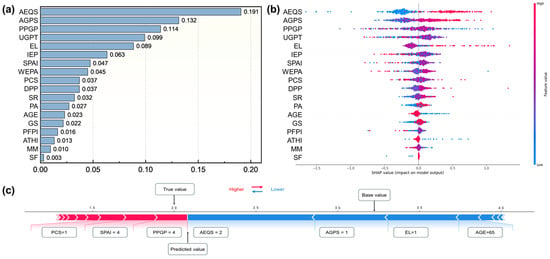

The feature importance analysis based on the LGBM model (Figure 5a) revealed that the top five most important features were, in order: Awareness of Ecological and Quality Safety (AEQS), Awareness of Green Production Standards (AGPS), Willingness to Accept a Price Premium for Green Products (PPGP), Understanding of Green Production Techniques (UGPT), and the Perception of the Industry’s Importance to Ecological Protection (IEP). The cumulative importance contribution of these five features reached 62.5. It is noteworthy that these features perfectly align with the five variables possessing the largest absolute values of regression coefficients in the Ordered Probit model (Table 3). This indicates a high degree of consistency between the two types of models in identifying key influencing factors, further validating the robustness of the research findings. SHAP dependence analysis (Figure 5b) further elucidated the direction of influence of key features on the prediction outcome. The SHAP values for AEQS and AGPS increased with their feature values, indicating that higher cognitive levels have a positive impact on DIGB, which corroborates the positive coefficients found in the Ordered Probit model. Conversely, the SHAP values for Age (AGE) showed a negative trend, also consistent with its negative estimated coefficient in the traditional econometric model, demonstrating agreement between the two model types regarding the direction of influence. The non-linear relationships uncovered by the SHAP interaction plots compensate for the limitation of the Ordered Probit model, which can only capture linear relationships, providing richer evidence for testing Hypotheses H3 and H4.

Figure 5.

Model interpretability analysis: (a) LGBM feature importance ranking; (b) SHAP dependence plots for features; (c) one-sample decision analysis.

Taking a single grower sample as an example (Figure 5c), a farmer predicted by the model as having low-level DIGB (Level 2) was selected for a SHAP decision analysis. The results indicate that the model’s base prediction value was approximately 3.2. In terms of feature contributions, PPGP = 4 and SPAI = 4 (both at a high level) acted as the main positive driving factors, significantly elevating the predicted level; PCS = 1 (at a relatively high level) also produced a positive contribution. However, AEQS = 2 and AGPS = 1 (both far below the average level) served as key negative inhibiting factors, substantially reducing the predicted level; simultaneously, AGE = 65 and its corresponding low education level (EL) also exerted a slight negative influence. The net effect of all feature contributions caused the final predicted value to decrease from the base value of 3.2 to 2.0. This case clearly shows that although a favorable policy environment (such as production subsidies) has a positive effect on green production behavior, the farmer is ultimately classified as a low-level DIGB group by the model due to possible age-related cognitive conservatism and other constraints. This result highlights the complexity of farmers’ green production decision-making under the interaction of multiple factors, and proves that effective intervention needs to take into account both internal cognition and external economic conditions. By integrating the global interaction model and individual case studies, this analysis provides strong support for H3 and H4, profoundly explains the synergistic enhancement effect between policy incentives and psychological cognition, and provides a scientific basis for designing differentiated and precise policy systems.

Based on the dual verification of case and method, the TPB-TOE integrated framework shows its value as a comprehensive tool for understanding complex environmental behaviors. The framework can accommodate the adjustment of regional heterogeneity while maintaining the integrity of the core theory, so it is particularly useful for policy design in diversified agricultural landscapes. In addition, studies have shown that policy tools need to be matched with specific cognitive and resource endowments, which provides a generalizable principle for global sustainable agricultural interventions: successful policy transplantation requires careful debugging based on local behavioral dynamics, rather than simply copying specific measures.

4.4. Interaction Analysis Results

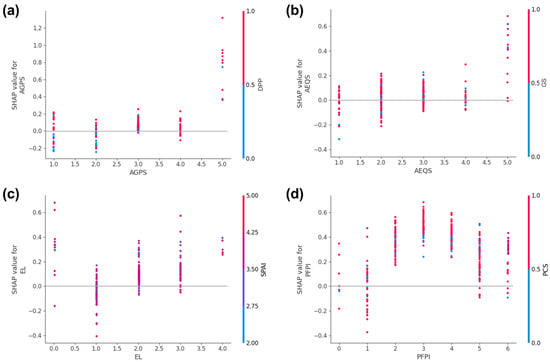

4.4.1. Interaction Effects Analysis Based on SHAP

Building upon the theoretical analytical framework and research hypotheses, this study focuses on examining the driving roles of policy incentives and psychological intention, as well as the interactive enhancement effects between policy and resource characteristics. The analysis of SHAP interaction values reveals significant synergistic effects among key variables influencing GPB. Specifically, a clear positive interaction exists between policy propaganda (DPP) and awareness of green production standards (AGPS) (Figure 6a). When policy propaganda intensity is high, their combined effect on promoting GPB far exceeds the simple sum of the individual effects of either factor alone. Similarly, a synergistic enhancement effect is observed between government supervision (GS) and awareness of ecological and quality safety (AEQS) (Figure 6b). This interaction is most prominent when AEQS ≥ 3 and supervision intensity is high, reflecting the effectiveness of the dual-driver mechanism of “external regulation—internal cognition.”

Figure 6.

Interaction analysis results: (a) DPP and AGPS; (b) GS and AEQS; (c) SPAI and EL; (d) PCS and PFPI.

On the other hand, the willingness to subsidize agricultural inputs (SPAI) has a more significant impact on groups with lower education levels (EL), suggesting this demographic is more sensitive to economic incentives (Figure 6c). This non-linear relationship highlights the heterogeneity of policy impacts and confirms that a one-size-fits-all policy design can generate efficiency losses. From a behavioral economics perspective, the finding is consistent with the core prediction of bounded-rationality theory. Farmers with low education levels face greater information asymmetry and cognitive constraints, so their adoption decisions rely heavily on intuitive, easily interpretable economic signals. A direct subsidy on green inputs lowers their perceived risk and behavioral threshold, producing a pronounced “kick-start” effect. The result also corroborates the compensation mechanism posited by motivation-crowding theory: for resource-poor actors, an external economic incentive can offset weak intrinsic motivation and create positive behavioral reinforcement. By contrast, better-educated farmers already possess stronger environmental awareness or longer-term profit expectations, so the marginal effect of an additional subsidy is comparatively small. Combined with age (AGE) characteristics, older growers with lower education levels pay more attention to actual costs, suggesting that policy promotion should emphasize differentiated design. Furthermore, product certification subsidies (PCS) have a more pronounced effect on households with a higher proportion of income from forest-grown ginseng (PFPI), reflecting their stronger reliance on this type of economic support (Figure 6d).

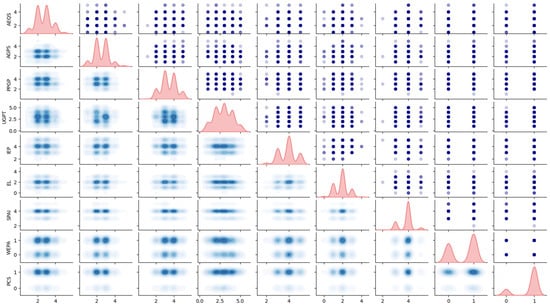

4.4.2. Matrix Visualization of Feature Interactions

To deeply investigate the complex interaction mechanisms among key influencing factors and address the limitations of traditional regression models in revealing bidirectional relationships between variables, this study further employs the Pairs Plot method to systematically analyze the top 9 important features identified by the LGBM model. This aims to intuitively reveal potential synergistic or antagonistic effects these variables might have on DIGB among forest-cultivated ginseng growers. Figure 7 shows the pairs plot matrix for these 9 core features. This matrix consists of three parts: the lower-left triangle displays the data distribution density areas between pairs of variables in the form of color-gradient density plots, effectively overcoming scatter point overlap issues and clearly revealing the core patterns of variable relationships; the diagonal presents the kernel density estimation curves for each variable, reflecting their own distribution shapes. For instance, awareness of green production standards (AGPS) and awareness of ecological and quality safety (AEQS) exhibit approximately normal distributions, while perception of industry ecological importance (IEP) shows a right-skewed characteristic; the upper-right triangle directly plots the scatter plots between variables, presenting the most primitive data relationships.

Figure 7.

Pairs plot of key features.

The matrix reveals deep-seated patterns beyond the influence of single variables. The four core cognitive variables—AEQS, AGPS, UGPT, and IEP—all show evident positive linear correlations with each other. Their scatter plots exhibit elliptical distributions from the bottom-left to the top-right, and the density plots also show data points densely distributed from low-low value areas to high-high value areas. This indicates that growers’ various cognitive levels do not exist in isolation but rather increase or decrease together, forming a multi-dimensional “cognitive literacy” complex. This explains why these cognitive variables exhibit the strongest predictive power and explanatory power in both the LGBM and Ordered Probit models. The relationships for some variables (e.g., AGE with certain cognitive variables) appear more dispersed in the scatter plots, and the density plots do not show clear linear patterns, suggesting that the relationships between these variables might be more complex or involve nonlinear interactions.

The analysis found that policy incentives and cognitive enhancement present linked pathways. Policy incentive variables (particularly product certification subsidy PCS) show stable positive correlation patterns with multiple cognitive variables (e.g., AGPS, AEQS). This implies that in areas where PCS policy implementation is stronger, or for growers who pay more attention to this policy, their cognitive levels regarding green production standards and ecological safety are generally higher. This visual evidence strongly supports the theoretical hypothesis path of “policy incentives → cognitive enhancement → behavioral response” (H3, H4). Policies might bring additional effects, such as through accompanying propaganda, indirectly promoting a leap in growers’ cognitive levels, rather than solely through direct economic drivers. The willingness to accept a price premium for green products (PPGP) also shows a positive correlation trend with key cognitive variables (AEQS, AGPS). This not only reflects the direct pull of economic return expectations on behavioral intention but also suggests that a higher cognitive level is the psychological foundation for forming reasonable price expectations and premium acceptance. The more growers understand the benefits of green production for ecology and quality, the more likely they are to recognize its market value.

4.4.3. Cross-Analysis Revealing Synergistic Effects

Cross-analysis reveals the intrinsic mechanisms through which multiple factors synergistically drive GPB. The specific findings are as follows:

(1) Policy synergistic effects: The significant synergy between ecological subsidies and policy propaganda indicates that standalone financial subsidies or policy promotion have a limited effect. In contrast, a combined strategy of “policy propaganda + financial subsidies + cognitive enhancement” proves more effective in motivating growers to adopt GPB, as demonstrated by practices in regions like Tonghua, where integrated approaches have enhanced subsidy efficiency. The interaction between policy perception and technical cognition underscores the importance of capacity building for growers, as enhancing their ability to understand policies and master technologies is a core link in ensuring policy effectiveness.

(2) Regional heterogeneity in interaction patterns: The differences in interaction patterns across regions suggest that policy interventions must consider local characteristics. For instance, in Yanbian, where the industry is in a growth phase, policies could focus on strengthening ecological protection zone management, while in Tonghua, which has a mature industrial base and market mechanisms, policies should emphasize the integration of market mechanisms with policy support, such as enhancing brand certification and a premium mechanism. This regional variation demonstrates that a one-size-fits-all policy approach is ineffective.

The cross-analysis method used in this study not only verifies the interaction mechanisms of multi-dimensional factors within the integrated TPB-TOE framework but also provides an empirical basis for subsequent precise policy design. However, a limitation is that the interaction analysis was confined to pairwise interactions between major variables. Future research could further explore higher-order interaction effects and more complex nonlinear relationship networks.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Conclusions

This study empirically analyzes the drivers of Green Production Behavior (GPB) among forest-cultivated ginseng growers in Jilin Province by integrating the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, and employing both an Ordered Probit model and an LGBM learning algorithm. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Verification of core driving mechanism Hypotheses (H1 & H2): The results provide robust empirical support for H1 and H2. Psychological cognition variables—particularly awareness of green production standards (β = 0.212, p < 0.01) and ecological quality safety (β = 0.276, p < 0.05)—significantly drive GPB, confirming H1. Similarly, resource endowment variables, especially income dependence on ginseng (β = 0.117, p < 0.05), validate H2. Consistency between Ordered Probit and LGBM results reinforces the robustness of these findings.

(2) Partial verification of interactive effect Hypotheses (H3 & H4): Partial but compelling evidence supports H3 and H4. SHAP analysis confirms synergistic policy-cognition interactions (H3), notably between policy propaganda and green standards awareness. However, policy–resource interactions (H4) display complex, context-dependent nonlinearity, with significance varying regionally, necessitating nuanced interpretation.

(3) Regional heterogeneity and hypothesis moderation: Support for hypotheses varies considerably across regions. Tonghua strongly supports H1 and H2, Baishan shows modified relationships emphasizing ecological constraints, and Yanbian highlights education and individual resources. This regional moderation underscores that while core hypotheses generally hold, their manifestation is shaped by local conditions. Methodological convergence between Ordered Probit and LGBM enhances verification credibility while revealing additional complex relationships.

5.2. Policy Recommendations

Based on the empirical evidence of heterogeneous driving factors across the three regions and the insights from machine learning interaction analysis, this study proposes the following policy recommendations.

1. Precise interventions should be applied and a differentiated policy system based on diagnosis–intervention–evaluation should be built. Tonghua Region: Policy focus should shift from universal subsidies to quality and efficiency enhancement. Efforts should concentrate on improving the green ginseng product certification and traceability system, strengthening the premium capability of regional brands like Changbai Mountain Ginseng, and clearing the market channel for high-quality and premium-priced products to stimulate endogenous market motivation among growers. Baishan Region: Policies should reinforce the rigid constraints of the ecological red line and couple them with supporting safeguard measures. It is advisable to tightly link ecological compensation policies with green production technology standards and provide more direct technical guidance and ecological compensation to growers within protection areas, thereby resolving the conflict between environmental protection and livelihoods. Yanbian area: building a differentiated cultivation system with capacity building as the core. Hierarchical training mechanism: carry out systematic training on green production technology and digital agriculture for young practitioners, and focus on ecological planting demonstration with strong practicality for traditional farmers. Cooperative empowerment model: Through the establishment of joint procurement and a shared technology platform, break through the limitations of individual resources and reach large-scale operational ability. Science and education integration network: Build a ‘science and technology courtyard’ practice base, promote the guidance of scientific research personnel in the village, and realize the coordination of technology promotion and localization innovation.

2. Optimize policy tool design, emphasizing the synergy between incentives and target group characteristics: Given the interaction effects identified, policies should be designed as a combination punch. When implementing subsidies for agricultural inputs, provide technical guidelines that are visualized and easy to understand for growers with lower education levels and older age, making economic incentives easier to comprehend and accept, thus leveraging the compensation effect. For specialized households with a high proportion of income from forest-grown ginseng—who are most sensitive to economic policies like certification subsidies—policies should maintain continuity and stability to firm up their confidence in long-term green investment. Policy formulation should identify group heterogeneity and implement higher-intensity subsidies or simpler subsidy application processes for low-education groups to improve policy efficiency.

3. Strengthen Market Drivers and Scientific Support to Build a Long-Term Ecosystem for Green Development: The government should collaborate with industry associations to vigorously promote regional public brands. Establishing traceability systems to enhance consumer trust and ensure premium realization for green products is crucial. Integrate the technical strengths of research institutions and enterprises to promote models like Science and Technology Backyards, delivering the latest green production technologies to growers in low-cost, easy-to-operate forms, thereby reducing the barriers to technology adoption.

4. Promote industrial integrated development and expand the pathways for realizing green value: Drawing on the “ginseng plus” integrated development concept, encourage areas with a solid industrial base, like Tonghua and Baishan, to develop green industrial chains integrating planting, sightseeing, health wellness, and cultural experiences. This enhances the added value of the industry, allows growers to gain diversified benefits from the green transition, and consolidates their green production behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.-B.Z. and C.-L.W.; formal analysis, Y.-J.L. and Y.-N.J.; investigation, Y.-J.L., Y.-N.J. and J.-F.H.; project administration, Y.Z. and C.-L.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.-B.Z. and Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Beijing Forestry University Science and Technology Innovation Project (Grant number 2021SCL01).

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

All participants in the study received informed consent to participate, and the study did not contain identifiable participant information. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Li, P.; Du, J.; Shahzad, F. Leader’s strategies for designing the promotional path of regional brand competitiveness in the context of economic globalization. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 972371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Guan, P.; Hao, C.; Yang, J.; Xie, Z.; Wu, D. Changes in assembly processes of soil microbial communities in forest-to-cropland conversion in Changbai Mountains, northeastern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 818, 151738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, Z.; Zhou, W.; Razzaq, A.; Yang, Y. Land resource management and sustainable, development: Evidence from China’s regional data. Resour. Policy 2023, 84, 103732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Wang, X.; Yang, R. Complements or substitutes? The impact of social interactions and Internet use on farmers’ green production technology adoption behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 518, 145964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, H. Farmers’ adoption of agriculture green production technologies: Perceived value or policy-driven? Heliyon 2024, 10, e23925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Liu, K.; Wu, Y.J. Overcoming Barriers to Agriculture Green Technology Diffusion through Stakeholders in China: A Social Network Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6976. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.; Wang, H.; Long, W.; Ma, J.; Cui, Y. Can Agricultural Cooperatives Promote Chinese Farmers’ Adoption of Green Technologies? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, R. Study on the influence mechanism of adoption of smart agriculture technology behavior. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatzky, L.G.; Fleischer, M. The Processes of Technological Innovation; Lexington Books: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 27–50. ISBN 0669203483. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Gao, Y.; Tang, M.; Ma, A. Promoting or inhibiting? The impact of urban–rural integration on the green transformation of arable land utilization: Evidence from China’s major grain-producing regions. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 176, 113617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.A.; Rasiah, R.; Furuoka, F.; Kumar, S.; Adnan, Z.H.; Chowdhury, N.H. Antecedents and firm performance of sustainable technology adoption in the clothing industry: A study based on the technology–organization–environment framework. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benchis, M.P.; Shahzad, K.; Dan, S. Comparative analysis of blockchain adoption in the public and private sectors. A technology-organization-environment (TOE) framework approach. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Zhao, P.; Chen, K.; Wu, L. Factors affecting the willingness of agricultural green production from the perspective of farmers’ perceptions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 738, 140289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Meng, W.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Wang, C. Driving factors of farmers’ green agricultural production behaviors in the multi-ethnic region in China based on NAM-TPB models. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 50, e02812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilahun, G.; Bantider, A.; Yayeh, D. Empirical and methodological foundations on the impact of climate-smart agriculture on food security studies: Review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greiner, R.; Gregg, D. Farmers’ intrinsic motivations, barriers to the adoption of conservation practices and effectiveness of policy instruments: Empirical evidence from northern Australia. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liang, X.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Xue, Y. Can government regulation weak the gap between green production intention and behavior? Based on the perspective of farmers’ perceptions. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xie, S.; Li, X.; Xia, X. Adoption of green production technologies by farmers through traditional and digital agro-technology promotion—An example of physical versus biological control technologies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, C. Exploring pathways for enhancing green total factor productivity in high-carbon emission enterprises: A configurational analysis based on the TOE framework and fsQCA. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Cai, H.H.; Khan, N.U.; Yin, H.; Al Shammre, A.S.; Ariza-Montes, A. Driving sustainability: Role of economic incentives, and environmental awareness in electronic sector. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 394, 127229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Lyu, C.; Tian, X.; Jiang, C.; Li, Q. The impact of digital marketing literacy on digital marketing strategy to enhance the library patrons’ engagement: An application of the TOE framework. Acta Psychol. 2025, 260, 105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, H.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L. The impact of incentive policies on shipowners’ adoption behavior of clean energy technologies: Evidence from China. Mar. Policy 2024, 167, 106277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Song, Z.; Xie, Y. Why incentive-regulatory policy synergy underperforms in driving energy transition: Evidence from China. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 27, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Xing, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, Y. Substitution or complementary effects: The impact of neighborhood effects and policy interventions on farmers’ pesticide packaging waste recycling behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 482, 144198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Hu, H.; Xiao, W. Spatiotemporal heterogeneity of ecosystem services in the context of policy intervention in Shanxi Province. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 28, 100975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chu, L.; Wang, C.; Pan, Y.; Su, W.; Qin, Y.; Cai, C. What drives the spatial heterogeneity of cropping patterns in the Northeast China: The natural environment, the agricultural economy, or policy? Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, G.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.; Tarefder, R.A. Examining driver injury severity outcomes in rural non-interstate roadway crashes using a hierarchical ordered logit model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2016, 96, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, F.; Lord, D. Comparing three commonly used crash severity models on sample size requirements: Multinomial logit, ordered probit and mixed logit models. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2014, 1, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Sadeghi, M.; Mauriello, F.; Riccardi, M.R.; Aghabayk, K.; Montella, A. Cyclist crash severity modeling: A hybrid approach of XGBoost-SHAP and random parameters logit with heterogeneity in means and variances. J. Saf. Res. 2025, 93, 373–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yin, Y.; Dong, C.; Yang, G.; Zhou, G. On the Class Imbalance Problem. In Proceedings of the 2008 Fourth International Conference on Natural Computation, Jinan, China, 18–20 October 2008; pp. 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samerei, S.A.; Aghabayk, K. Analyzing the transition from two-vehicle collisions to chain reaction crashes: A hybrid approach using random parameters logit model, interpretable machine learning, and clustering. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 202, 107603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, X.; Xie, Y.; Wu, L.; Jiang, L. Quantifying and comparing the effects of key risk factors on various types of roadway segment crashes with LightGBM and SHAP. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 159, 106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).