Evaluation of Soil Health of Panax notoginseng Forest Plantations Based on Minimum Data Set

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

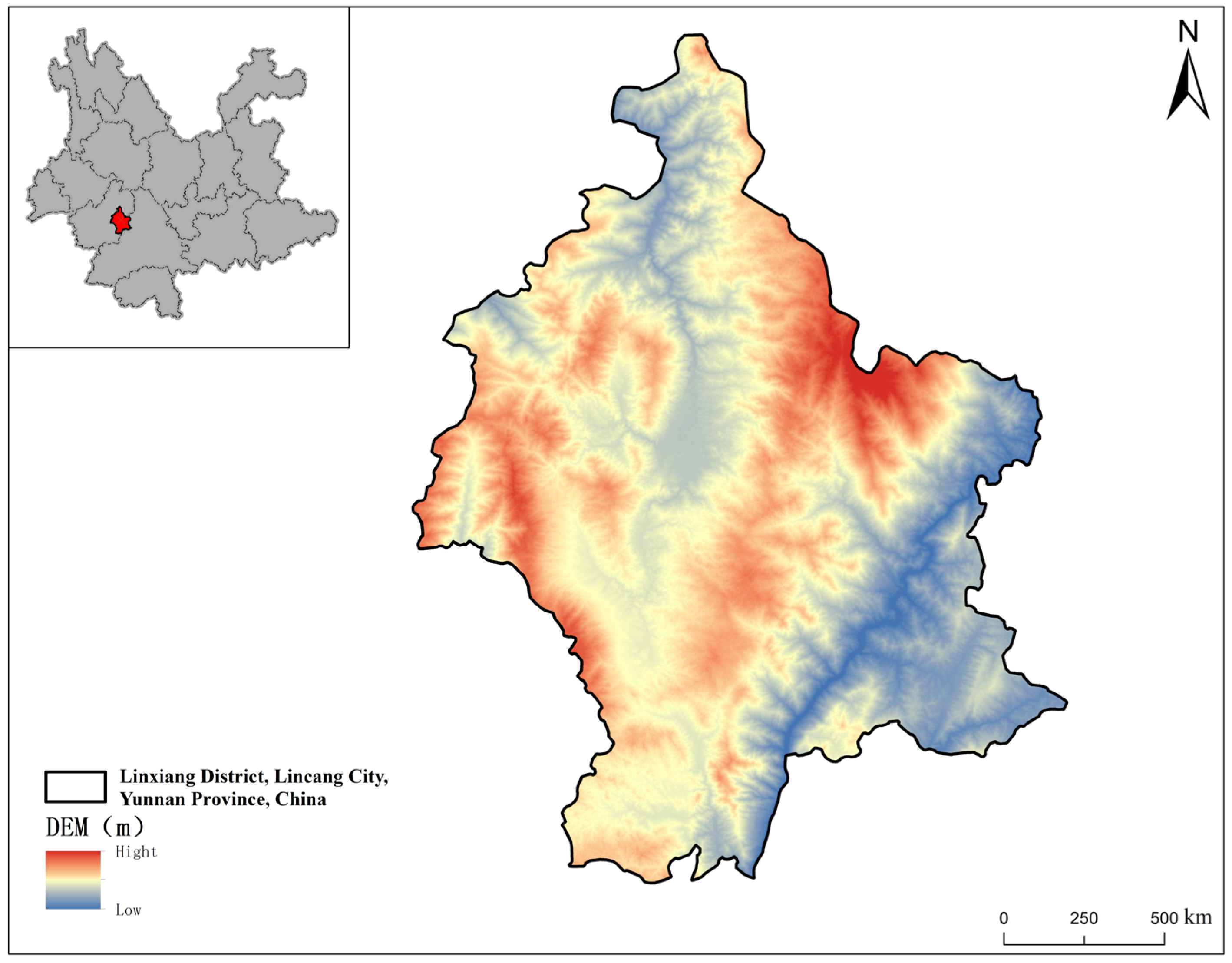

2.1. Overview of the Study Area

2.2. Soil Sample Collection

2.3. Analysis of Soil Physicochemical Properties and Enzyme Activities

2.4. Analysis of Soil Microbial Community Structure

2.4.1. DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

2.4.2. Bioinformatics Analysis

2.5. Soil Health Assessment

2.5.1. Minimum Dataset Construction

2.5.2. Construction of Soil Health Evaluation Function

2.5.3. Calculation of the Soil Health Index

2.6. Statistical Analysis of Data

2.7. Suitability Test for Multivariate Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Construction and Testing of a Full Dataset of Panax notoginseng in the Forest

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of Soil Health Indicators for Understory Panax notoginseng

3.3. Minimum Data Set Establishment for Soil Health Evaluation

3.3.1. Principal Component Analysis and Selection of Candidate Indicators

3.3.2. Correlation Analysis and Finalization of the Minimum Data Set

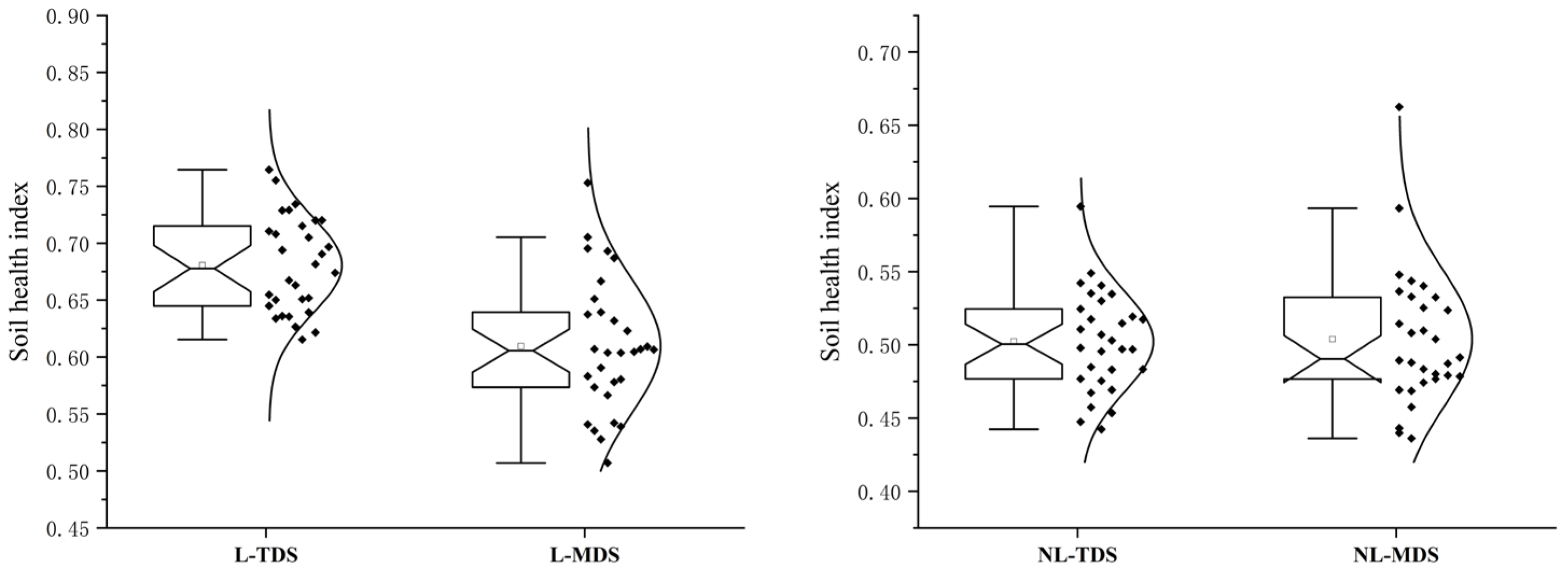

3.4. Soil Health Assessment Based on Minimum and Total Datasets

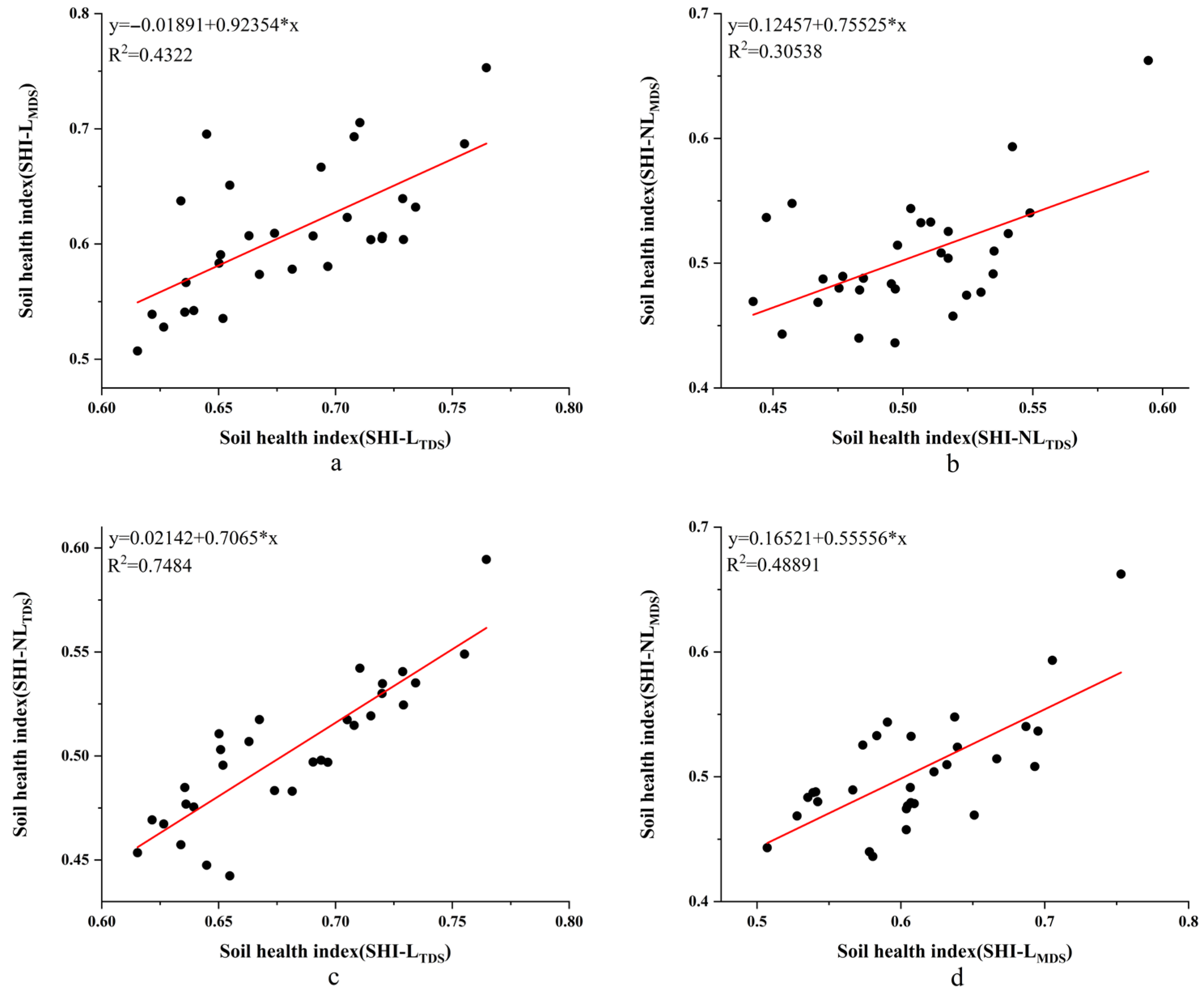

3.5. Validation of Soil Health Evaluation Method for Understory Panax notoginseng Based on Minimum Data Set

4. Discussion

4.1. Construction of the Minimum Dataset for Soil Health Evaluation of Understory Panax notoginseng and Analysis of the Role of Key Indicators

4.2. Impact of Forest Panax notoginseng Cultivation on Soil Health

5. Conclusions

- Control of Planting Duration: Given the significant decline in the Soil Health Index (SHI) observed after the third year of cultivation, it is recommended that the monoculture period be strictly limited to two years. Subsequently, crop rotation with nitrogen-fixing plants or non-medicinal crops should be implemented to disrupt the development of continuous cropping obstacles.

- Seasonal Precision Management: In response to the consistent pattern of superior soil health during the dry season compared to the rainy season, soil conservation measures should be enhanced prior to the onset of the rainy season. Specific recommendations include using mulches (e.g., straw or plastic film) to reduce nutrient leaching and applying organic amendments to improve soil buffering capacity and resilience.

- Microbial Community Regulation: The inclusion of key microbial indicators in the MDS highlights that soil biological degradation is a core driver of health decline. In practice, the application of microbial inoculants or functional organic fertilizers can be employed to directionally modulate the soil microbiome and counteract the functional degradation associated with deleterious shifts in fungal community structure.

- Establishment of an SHI-based Early Warning and Intervention Mechanism: The SHI values obtained using linear and non-linear scoring functions ranged from 0.53 to 0.72 (mean 0.62) and 0.48–0.59 (mean 0.51), respectively, establishing the baseline soil health status for the region. Based on the more conservative non-linear scoring results, it is proposed to set an SHI value of 0.50 as the early warning threshold, triggering intensified monitoring and management optimization when values fall below this level. An SHI value of 0.48 should be established as the mandatory intervention threshold, necessitating practices such as crop rotation, fallowing, or comprehensive soil remediation when breached.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kalinowska, B.; Bórawski, P.; Bełdycka-Bórawska, A.; Klepacki, B.; Perkowska, A.; Rokicki, T. Sustainable Development of Agriculture in Member States of the European Union. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurett, R.; Paço, A.; Mainardes, E.W. Sustainable development in agriculture and its antecedents, barriers and consequences–an exploratory study. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, A.; Yadav, D.; Srivastava, P.; Babu, S.; Kumar, D.; Singh, D.; Vishwakarma, D.K.; Sharma, V.; Madhu, M. Restoration of agroecosystems with conservation agriculture for food security to achieve sustainable development goals. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3079–3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Jin, H.; Pu, X. Evaluation of green agricultural development and its influencing factors under the framework of sustainable development goals: Case study of Lincang city, an underdeveloped mountainous region of China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.-W.; Bao, D.-F.; Bhat, D.J.; Su, H.-Y.; Luo, Z.-L. Lignicolous freshwater fungi in Yunnan Province, China: An overview. Mycology 2022, 13, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Xiong, J.; Bian, J.; Jin, H.; Cheng, W.; Li, A. Vegetation Change and Its Response to Climate Change in Yunnan Province, China. Adv. Meteorol. 2021, 2021, 8857589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, Y.; Gao, B.; Zheng, K.; Wu, Y.; Li, C.J.E.I. Multi-scenario simulation of ecosystem service value for optimization of land use in the Sichuan-Yunnan ecological barrier, China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zheng, J.; He, M.; Feng, G.; He, K.; Ma, T.; Coffman, D.; Mi, Z.; Wang, S. A multi-regional input-output database linking Chinese subnational regions and global economies. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, W.; Shen, Z.; Duan, X. Spatiotemporal patterns and drivers of soil erosion in Yunnan, Southwest China: RULSE assessments for recent 30 years and future predictions based on CMIP6. CATENA 2023, 220, 106703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, W. Revealing the ecological impact of low-speed mountain wind power on vegetation and soil erosion in South China: A case study of a typical wind farm in Yunnan. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 419, 138020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Zhao, J.; Duan, X.; Tang, B.; Zuo, L.; Wang, X.; Guo, Q. Spatial quantification of cropland soil erosion dynamics in the yunnan plateau based on sampling survey and multi-source LUCC data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Q.; Zeng, Z.; Shi, J.-Y. Study on the path of high-quality development of under-forest economy in Yunnan under the background of rural revitalization. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2023, 51, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Han, X.; Lv, S.; Song, B.; Zhang, X.; Li, H. The influencing factors of pro-environmental behaviors of farmer households participating in understory economy: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2022, 15, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Rui, R.; Yang, Y.; Hei, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Yi, Z.; He, X. Soil Extracellular Enzyme Stoichiometry Reveals an Alleviation of Microbial C Limitation in Pinus armandii Forests Following Panax notoginseng Cultivation in Yunnan, China. preprint. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4768607 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Qiao, Q.; Lei, S.; Zhang, W.; Shao, G.; Sun, Y.; Han, Y. Contrasting Non-Timber Forest Products’ Case Studies in Underdeveloped Areas in China. Forests 2024, 15, 1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.Q.; Lu, X.; Du, M.-R.; Xiao, S.-L.; Li, S.; Han, P.-B.; Zeng, J.-L.; Wen, J.-R.; Yao, S.-Q.; Shi, Y.-C.; et al. Forest characteristics and population structure of a threatened palm tree Caryota obtusa in the karst forest ecosystem of Yunnan, China. J. Plant Ecol. 2022, 15, 829–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Wang, H.; Luo, L.; Zhu, S.; Huang, H.; Wei, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, L.; He, X. Effects of different soil moisture on the growth, quality, and root rot disease of organic Panax notoginseng cultivated under pine forests. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 329, 117069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tian, G.; Yang, S.; Chen, J.; Zi, S.; Fan, W.; Ma, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Panax notoginseng Planted Under Coniferous Forest: Effects on Soil Health and the Soil Microbiome. Forests 2024, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.; Wang, S.; He, X.; Zhao, X. Different factors drive the assembly of pine and Panax notoginseng-associated microbiomes in Panax notoginseng-pine agroforestry systems. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1018989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Yang, J.; Li, Q.; PinChu, C.; Song, Z.; Yang, H.; Luo, Y.; Liu, C.; Fan, W. Diversity and correlation analysis of different root exudates on the regulation of microbial structure and function in soil planted with Panax notoginseng. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1282689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zheng, W.; Rao, C.; Wang, E.; Yan, W. Soil quality assessment and management in karst rocky desertification ecosystem of Southwest China. Forests 2022, 13, 1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M. Soil health assessment and management: Recent development in science and practices. Soil Syst. 2021, 5, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, M.R.; Veum, K.S.; Parker, P.A.; Holan, S.H.; Karlen, D.L.; Amsili, J.P.; van Es, H.M.; Wills, S.A.; Seybold, C.A.; Moorman, T.B. The soil health assessment protocol and evaluation applied to soil organic carbon. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2021, 85, 1196–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hei, J.; Wang, S.; He, X. Effects of exogenous organic acids on the growth, edaphic factors, soil extracellular enzymes, and microbiomes predict continuous cropping obstacles of Panax notoginseng from the forest understorey. Plant Soil 2024, 503, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; He, S.; Rui, R.; Hei, J.; He, X.; Wang, S. Introduction of Panax notoginseng into pine forests significantly enhances the diversity, stochastic processes, and network complexity of nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the soil. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1531875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamehpour, N.; Rezapour, S.; Ghaemian, N. Quantitative assessment of soil quality indices for urban croplands in a calcareous semi-arid ecosystem. Geoderma 2021, 382, 114781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaca, S.; Dengiz, O.; Turan, İ.D.; Özkan, B.; Dedeoğlu, M.; Gülser, F.; Sargin, B.; Demirkaya, S.; Ay, A. An assessment of pasture soils quality based on multi-indicator weighting approaches in semi-arid ecosystem. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 121, 107001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.; Li, Z.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, Y. Evaluation of ecological suitability and quality suitability of panax notoginseng under multi-regionalization modeling theory. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 818376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, T.; Ji, C.; Zang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Liang, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, J.; Li, N.; Liu, X. Harnessing water and salt synergy: Elevating Panax notoginseng growth and quality under drip irrigation in southwest China. Soil Use Manag. 2025, 41, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klute, A. Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 1. Physical and Mineralogical Methods; American Society of Agronomy, Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Page, A.L. Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2. Chemical and Microbiological Properties; American Society of Agronomy, Soil Science Society of America: Madison, WI, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottomley, P.J.; Angle, J.S.; Weaver, R. Methods of Soil Analysis, Part 2: Microbiological and Biochemical Properties; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moebius, B.N.; van Es, H.M.; Schindelbeck, R.R.; Idowu, O.J.; Clune, D.J.; Thies, J.E. Evaluation of laboratory-measured soil properties as indicators of soil physical quality. Soil Sci. 2007, 172, 895–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weil, R.R.; Islam, K.R.; Stine, M.A.; Gruver, J.B.; Samson-Liebig, S.E. Estimating active carbon for soil quality assessment: A simplified method for laboratory and field use. Am. J. Altern. Agric. 2003, 18, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.F.; Upadhyaya, A. Extraction of an abundant and unusual protein from soil and comparison with hyphal protein of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Soil Sci. 1996, 161, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Fierer, N.; Knight, R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 4516–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.J.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. Guide Methods Appl. 1990, 18, 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magoč, T.; Salzberg, S.L. FLASH: Fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2957–2963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. UPARSE: Highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 996–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Garrity, G.M.; Tiedje, J.M.; Cole, J.R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 5261–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schloss, P.D.; Westcott, S.L.; Ryabin, T.; Hall, J.R.; Hartmann, M.; Hollister, E.B.; Lesniewski, R.A.; Oakley, B.B.; Parks, D.H.; Robinson, C.J.; et al. Introducing mothur: Open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7537–7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S.S.; Karlen, D.L.; Mitchell, J.P. A comparison of soil quality indexing methods for vegetable production systems in Northern California. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 90, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Hao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, S. Soil quality evaluation for reclamation of mining area on Loess Plateau based on minimum data set. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2019, 35, 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S.S.; Karlen, D.L.; Cambardella, C.A. The soil management assessment framework: A quantitative soil quality evaluation method. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 1945–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, M.S.; Holden, N.M. Quantitative soil quality indexing of temperate arable management systems. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 150, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiesi, F. A minimum data set and soil quality index to quantify the effect of land use conversion on soil quality and degradation in native rangelands of upland arid and semiarid regions. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 75, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, R.L.; Whittaker, T.A. Scale development research: A content analysis and recommendations for best practices. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 806–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thao, N.T.; Van Tan, N.; Tuyet, M.T. KMO and Bartlett’s test for components of workers’ working motivation and loyalty at enterprises in Dong Nai Province of Vietnam. Int. Trans. J. Eng. Manag. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2022, 13, 13A10M. [Google Scholar]

- Faloye, O.T.; Ajayi, A.E.; Oguntunde, P.G.; Kamchoom, V.; Fasina, A. Modeling and Optimization of Maize Yield and Water Use Efficiency under Biochar, Inorganic Fertilizer and Irrigation Using Principal Component Analysis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, N.; Gu, Y.; Li, D.; Liang, Y.; Yuan, J.; Liu, J.; Ren, J.; Cai, H. Soil quality evaluation in topsoil layer of black soil in Jilin Province based on minimum data set. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2021, 37, 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, R.; Feng, G.; Liu, X.; Zuo, Y.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Evaluating the effects of agricultural inputs on the soil quality of smallholdings using improved indices. CATENA 2022, 209, 105838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, O.; Ali, T.; Baba, Z.A.; Rather, G.; Bangroo, S.; Mukhtar, S.D.; Naik, N.; Mohiuddin, R.; Bharati, V.; Bhat, R.A. Soil organic matter and its impact on soil properties and nutrient status. In Microbiota and Biofertilizers, Vol 2: Ecofriendly Tools for Reclamation of Degraded Soil Environs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 129–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Chen, S.; Zhu, N.; Jeyakumar, P.; Wang, J.; Xie, W.; Feng, Y. Hydrothermal carbonization aqueous phase promotes nutrient retention and humic substance formation during aerobic composting of chicken manure. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 385, 129418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, D.V.; Silva, M.L.N.; Beniaich, A.; Pio, R.; Gonzaga, M.I.S.; Avanzi, J.C.; Bispo, D.F.A.; Curi, N. Dynamics and losses of soil organic matter and nutrients by water erosion in cover crop management systems in olive groves, in tropical regions. Soil Tillage Res. 2021, 209, 104863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.E. How effective are existing phosphorus management strategies in mitigating surface water quality problems in the US? Sustainability 2021, 13, 6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xie, T.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, C.; Xiong, W.; Xu, L.; Wu, Y.; He, Z.; Li, X. Alkaline phosphatase activity mediates soil organic phosphorus mineralization in a subalpine forest ecosystem. Geoderma 2021, 404, 115376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ren, X.; Cai, L. Effects of different straw incorporation amounts on soil organic carbon, microbial biomass, and enzyme activities in Dry-Crop Farmland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Jin, V.L.; Konkel, J.Y.M.; Schaeffer, S.M.; Schneider, L.G.; DeBruyn, J.M. Soil health management enhances microbial nitrogen cycling capacity and activity. mSphere 2021, 6, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Han, M.; Yuan, X.; Cao, G.; Zhu, B. Seasonal changes in soil properties, microbial biomass and enzyme activities across the soil profile in two alpine ecosystems. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2021, 3, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babur, E.; Dindaroğlu, T.; Solaiman, Z.M.; Battaglia, M.L. Microbial respiration, microbial biomass and activity are highly sensitive to forest tree species and seasonal patterns in the Eastern Mediterranean Karst Ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 775, 145868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Ai, N.; Liu, G.; Liu, C.; Qiang, F. Soil quality evaluation of various microtopography types at different restoration modes in the loess area of Northern Shaanxi. CATENA 2021, 207, 105633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Sun, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, J. Construction and application of the phaeozem health evaluation system in Liaoning Province. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, L.; Zhou, D. Root morphological responses to population density vary with soil conditions and growth stages: The complexity of density effects. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 10590–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Nie, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, K.; Querejeta, J.I. Water uptake depth is coordinated with leaf water potential, water-use efficiency and drought vulnerability in karst vegetation. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 1339–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mageed, T.A.A.; El-Mageed, S.A.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Abdelaziz, S.; Abdou, N.M. Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria improve growth, morph-physiological responses, water productivity, and yield of rice plants under full and deficit drip irrigation. Rice 2022, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, A.; Sinha, R.; Singla-Pareek, S.L.; Pareek, A.; Singh, A.K. Shaping the root system architecture in plants for adaptation to drought stress. Physiol. Plant. 2022, 174, e13651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Hui, W.; Zhao, F.; Wang, P.; Su, C.; Gong, W. Physiology of plant responses to water stress and related genes: A review. Forests 2022, 13, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; An, Z.; Suo, L.; Ding, J.; Li, S.; Wei, D.; Jin, L. Effects of the rainfall intensity and slope gradient on soil erosion and nitrogen loss on the sloping fields of miyun reservoir. Plants 2023, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H. Effect of soil conservation measures and slope on runoff, soil, TN, and TP losses from cultivated lands in northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 126, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bartlett’s Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| KMO | Approximate Chi-Square | Degrees of Freedom | Significance |

| 0.666 | 1324.508 | 406 | 0.000 |

| Indicator | Soil Health Indicators | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical indicators | Total Porosity/% | 69.82 | 78.00 | 74.61 | 2.36 | 3.2% |

| Saturated Water Holding Capacity/% | 17.22 | 23.94 | 20.99 | 1.92 | 9.2% | |

| Capillary Water Holding Capacity/% | 10.56 | 14.94 | 13.08 | 1.30 | 9.9% | |

| Field Capacity/% | 4.29 | 8.41 | 6.49 | 1.08 | 16.7% | |

| Capillary Porosity/% | 2.61 | 4.72 | 4.04 | 0.64 | 15.8% | |

| Non-capillary Porosity/% | 65.37 | 75.27 | 70.57 | 2.37 | 3.4% | |

| Bulk Density/mg m−3 | 0.51 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.05 | 8.6% | |

| Clay Content/% | 3.23 | 12.99 | 7.91 | 2.69 | 34.0% | |

| Silt Content/% | 53.88 | 87.11 | 71.95 | 7.66 | 10.7% | |

| Very Fine Sand Content/% | 1.70 | 8.42 | 5.13 | 1.85 | 36.2% | |

| Fine Sand Content/% | 0.00 | 4.68 | 0.78 | 1.00 | 128.1% | |

| Chemical indicators | PH/% | 4.23 | 5.65 | 5.07 | 0.32 | 6.4% |

| Soil Organic Matter/(mg·kg−1) | 11.06 | 21.81 | 15.48 | 3.03 | 19.6% | |

| Microbial Biomass Carbon/(mg·kg−1) | 0.12 | 1.58 | 0.77 | 0.46 | 59.8% | |

| Microbial Biomass Nitrogen/(mg·kg−1) | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 32.3% | |

| Total Nitrogen/(mg·kg) | 2.05 | 6.49 | 4.37 | 1.10 | 25.1% | |

| Sucrase Activity/(mg·kg) | 0.75 | 5.31 | 2.28 | 1.20 | 52.8% | |

| Acid Phosphatase Activity/(g·kg) | 0.53 | 1.69 | 1.03 | 0.38 | 37.0% | |

| Available Phosphorus/(mg·kg−1) | 9.37 | 31.54 | 20.33 | 6.27 | 30.8% | |

| Urease Activity/(mg·kg) | 0.12 | 1.82 | 0.84 | 0.43 | 50.6% | |

| Catalase Activity/(μg·kg−1) | 9.03 | 12.07 | 10.57 | 0.78 | 7.3% | |

| Biological indicators | Bacterial Chao1 index | 1715.48 | 3453.06 | 2570.87 | 420.09 | 16.3% |

| Fungal Chao1 index | 348.33 | 1411.08 | 947.41 | 240.51 | 25.4% | |

| Bacterial ACE index | 1705.76 | 3442.75 | 2600.69 | 426.54 | 16.4% | |

| Fungal ACE index | 344.68 | 1450.40 | 995.10 | 263.05 | 26.4% | |

| Bacterial Shannon index | 4.92 | 6.10 | 5.64 | 0.29 | 5.1% | |

| Fungal Shannon index | 2.94 | 4.58 | 3.82 | 0.43 | 11.3% | |

| Bacterial Simpson index | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 34.2% | |

| Fungal Simpson index | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 41.4% |

| Indicators of Soil Properties | Post-Rotation Factor Loadings | Clusters | Norm | Variance of a Common Factor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||||

| Bulk density | −0.001 | 0.123 | −0.011 | 0.181 | 0.203 | −0.847 | −0.084 | 6 | 1.192945754 | 0.813 |

| Total porosity | 0.329 | 0.110 | 0.133 | −0.162 | 0.824 | −0.178 | 0.219 | 5 | 1.530009473 | 0.923 |

| Capillary porosity | 0.829 | 0.354 | −0.042 | −0.108 | 0.244 | −0.161 | 0.091 | 1 | 2.567159318 | 0.921 |

| Non-capillary porosity | 0.478 | 0.064 | 0.169 | 0.000 | 0.693 | −0.132 | 0.152 | 5 | 1.702397325 | 0.781 |

| Saturated water holding capacity | 0.380 | 0.443 | −0.575 | −0.015 | 0.009 | 0.270 | −0.257 | 3 | 1.955820026 | 0.810 |

| Capillary water holding capacity | 0.837 | 0.328 | −0.037 | −0.030 | −0.130 | 0.140 | −0.108 | 1 | 2.549130242 | 0.859 |

| Field Capacity | 0.826 | 0.107 | 0.083 | −0.204 | 0.233 | 0.009 | −0.154 | 1 | 2.444988813 | 0.819 |

| Clay content | 0.460 | 0.292 | 0.273 | −0.483 | 0.300 | 0.070 | −0.132 | 1 | 1.797171955 | 0.717 |

| Silt content | −0.096 | 0.235 | 0.112 | 0.288 | −0.204 | 0.678 | 0.231 | 6 | 1.13997348 | 0.714 |

| Very Fine Sand Content | 0.006 | 0.261 | −0.137 | 0.798 | −0.061 | 0.031 | 0.236 | 4 | 1.386406533 | 0.784 |

| Fine Sand Content | 0.266 | −0.050 | 0.275 | 0.307 | 0.107 | −0.746 | −0.069 | 4 | 1.350260399 | 0.816 |

| pH | 0.269 | 0.412 | −0.564 | 0.116 | −0.003 | 0.333 | −0.065 | 2 | 1.741748821 | 0.689 |

| Soil Organic Matter | 0.210 | −0.052 | 0.909 | 0.052 | 0.182 | −0.101 | 0.098 | 3 | 1.983138784 | 0.928 |

| Microbial Biomass Carbon | −0.057 | −0.107 | −0.133 | −0.539 | 0.262 | 0.295 | −0.556 | 7 | 1.180359536 | 0.788 |

| Microbial Biomass Nitrogen | −0.245 | −0.222 | 0.023 | −0.198 | 0.292 | 0.429 | −0.597 | 7 | 1.284072075 | 0.776 |

| Total nitrogen | 0.009 | 0.086 | 0.863 | −0.100 | 0.147 | 0.055 | −0.115 | 3 | 1.800131052 | 0.799 |

| Available phosphorus | −0.034 | 0.364 | −0.044 | −0.134 | 0.451 | 0.392 | −0.509 | 5 | 1.270095788 | 0.770 |

| Urease Activity | −0.605 | 0.031 | 0.436 | 0.310 | −0.249 | 0.055 | 0.183 | 3 | 2.052415906 | 0.752 |

| Sucrase Activity | −0.579 | −0.133 | 0.727 | 0.160 | 0.026 | 0.158 | 0.073 | 3 | 2.279872248 | 0.938 |

| Acid Phosphatase Activity | 0.840 | 0.383 | 0.182 | 0.043 | 0.120 | −0.131 | −0.100 | 1 | 2.623063376 | 0.929 |

| Catalase Activity | 0.224 | −0.033 | 0.869 | 0.239 | −0.094 | 0.005 | 0.103 | 3 | 1.934685493 | 0.883 |

| Bacterial Chao1 Index | 0.312 | 0.814 | 0.010 | 0.199 | −0.210 | 0.095 | −0.286 | 2 | 2.167069447 | 0.934 |

| Fungal Chao1 Index | 0.185 | 0.848 | −0.107 | −0.286 | 0.209 | 0.135 | 0.058 | 2 | 2.130345807 | 0.911 |

| Bacterial ACE index | 0.349 | 0.780 | −0.017 | 0.237 | −0.156 | 0.134 | −0.241 | 2 | 2.14433525 | 0.888 |

| Fungal ACE index | 0.173 | 0.917 | −0.111 | −0.140 | 0.138 | 0.134 | −0.008 | 2 | 2.233135243 | 0.939 |

| Bacterial Simpson Index | −0.150 | −0.137 | 0.212 | −0.037 | 0.335 | 0.087 | 0.782 | 7 | 1.180094673 | 0.819 |

| Fungal Simpson Index | −0.161 | −0.067 | 0.172 | 0.824 | −0.091 | 0.089 | −0.219 | 4 | 1.391290448 | 0.803 |

| Bacterial Shannon Index | 0.318 | 0.595 | 0.021 | 0.141 | −0.242 | −0.063 | −0.599 | 2 | 1.829233859 | 0.898 |

| Fungal Shannon Index | 0.308 | 0.339 | −0.273 | −0.727 | 0.152 | 0.028 | 0.108 | 2 | 1.715936425 | 0.849 |

| Eigenvalue | 8.328 | 5.464 | 4.195 | 2.197 | 1.687 | 1.209 | 1.166 | |||

| variance contribution | 28.718 | 18.718 | 14.467 | 7.575 | 5.819 | 4.168 | 4.020 | |||

| Cumulative Variance Contribution Rate (%) | 28.718 | 47.561 | 62.028 | 69.603 | 75.422 | 79.589 | 83.609 | |||

| Indicators of Soil Properties | TDS | TDS | MDS | MDS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variance of a Common Factor | Weights | Variance of a Common Factor | Weights | |

| Non-capillary Porosity | 0.781 | 0.032 | 0.703 | 0.083 |

| Soil Organic Matter | 0.928 | 0.038 | 0.909 | 0.108 |

| Microbial Biomass Nitrogen | 0.776 | 0.032 | 0.716 | 0.085 |

| Sucrase Activity | 0.938 | 0.039 | 0.909 | 0.108 |

| Acid Phosphatase Activity | 0.929 | 0.038 | 0.912 | 0.108 |

| Bulk Density | 0.813 | 0.034 | 0.648 | 0.077 |

| Silt Content | 0.714 | 0.029 | 0.677 | 0.080 |

| Fine Sand Content | 0.816 | 0.034 | 0.844 | 0.100 |

| Total Nitrogen | 0.799 | 0.033 | 0.803 | 0.095 |

| Fungal ACE Index | 0.939 | 0.039 | 0.713 | 0.085 |

| Fungal Simpson Index | 0.803 | 0.033 | 0.598 | 0.071 |

| Total Porosity | 0.923 | 0.038 | ||

| Capillary Porosity | 0.921 | 0.038 | ||

| Saturated Water Holding Capacity | 0.810 | 0.033 | ||

| Capillary Water Holding Capacity | 0.859 | 0.035 | ||

| Field Capacity | 0.819 | 0.034 | ||

| Aggregate | 0.717 | 0.030 | ||

| Very Fine Sand Content | 0.784 | 0.032 | ||

| pH | 0.689 | 0.028 | ||

| Microbial Biomass Carbon | 0.788 | 0.033 | ||

| Available Phosphorus | 0.770 | 0.032 | ||

| Urease Activity | 0.752 | 0.031 | ||

| Catalase Activity | 0.883 | 0.036 | ||

| Bacterial Chao1 Index | 0.934 | 0.039 | ||

| Fungal Chao1 Index | 0.911 | 0.038 | ||

| Bacterial ACE Index | 0.888 | 0.037 | ||

| Bacterial Simpson Index | 0.819 | 0.034 | ||

| Bacterial Shannon Index | 0.898 | 0.037 | ||

| Fungal Shannon Index | 0.849 | 0.035 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tang, W.; Li, J.; Yan, H.; Cha, L.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L. Evaluation of Soil Health of Panax notoginseng Forest Plantations Based on Minimum Data Set. Forests 2025, 16, 1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121869

Tang W, Li J, Yan H, Cha L, Yang Y, Wang L. Evaluation of Soil Health of Panax notoginseng Forest Plantations Based on Minimum Data Set. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121869

Chicago/Turabian StyleTang, Wenqi, Jianqiang Li, Huiying Yan, Lianling Cha, Yuan Yang, and Linling Wang. 2025. "Evaluation of Soil Health of Panax notoginseng Forest Plantations Based on Minimum Data Set" Forests 16, no. 12: 1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121869

APA StyleTang, W., Li, J., Yan, H., Cha, L., Yang, Y., & Wang, L. (2025). Evaluation of Soil Health of Panax notoginseng Forest Plantations Based on Minimum Data Set. Forests, 16(12), 1869. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121869