1. Introduction

Slime moulds (Eumycetozoa) constitute a monophyletic lineage within Amoebozoa comprising three principal groups: Myxogastria (traditionally “myxomycetes”), Dictyostelia, and Protosporangiida [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Foundational syntheses emphasise their distinct life histories and their separation from fungi and other protists on molecular grounds [

6,

7]. In temperate forests, the best-studied group, Myxogastria, alternates between microscopic trophic stages and macroscopic sporocarps. Trophic stages graze on bacteria and other microorganisms in moisture-retentive substrates such as coarse woody debris, bark, and leaf litter, and fruiting occurs when conditions permit [

8,

9,

10]. Phenotypic plasticity promotes persistence across fluctuating hydric regimes: amoeboflagellate cells alternate between flagellated and amoeboid forms, and dormant structures enable survival during adverse periods [

11,

12,

13].

Moisture, shading, and substrate porosity are widely regarded as proximate controls on sporulation frequency and community composition [

6,

9,

14]. Dead wood, in particular, buffers humidity, concentrates microbial prey and provides sheltered pathways for trophic stages to migrate, with sporocarps often appearing on more exposed surfaces once conditions shift [

5,

10,

15]. These properties, together with consistent responses to stand structure and the continuity of dead wood, have motivated the use of slime mould assemblages as practical bioindicators of forest condition and change [

7,

16]. Substrate affinities are prominent: lignicolous assemblages dominated by genera such as

Arcyria,

Lycogala,

Stemonitis, and

Trichia are typically richer where decomposing xylem is abundant; corticolous communities specialise on living bark; and leaf-litter assemblages are often associated with genera such as

Diderma,

Didymium, and

Physarum [

6,

8,

13,

17]. Conifer-dominated detritus can favour more acid-tolerant consortia, illustrating how tree composition and substrate chemistry interact to structure communities [

6,

17].

Despite these insights, continental-scale syntheses that harmonise taxonomy, georeferencing, and environmental descriptors remain scarce for Central and Eastern Europe. The absence of integration has impeded statistically robust comparisons across forest habitats and management regimes, limited the ability to quantify elevation responses consistently, and hindered objective gap mapping for targeted surveys. Regional checklists and inventories highlight strong local signals but also expose methodological heterogeneity that complicates cross-country inference [

18,

19]. A recently assembled, Darwin Core-mapped resource addresses these barriers by standardising the names, coordinates, and descriptors relevant to forests across countries, providing traceable provenance and controlled vocabularies for cross-study comparability [

4,

20]. Such integration is essential for evaluating substrate affinities and bioindicator potential in a way that is reproducible and extensible as new data accrue, and it complements habitat-based and elevation-focused surveys that show compressed development windows at high altitudes. This integration is foundational for Europe-wide bioindication with slime moulds and underpins the cross-country generalisation assessed here.

Within this framework, the study investigated how forest habitat, management intensity, and elevation organised slime mould assemblages at a regional scale and assessed the extent to which particular taxa functioned as indicators along these gradients. The approach was pragmatic. Diversity comparisons were effort-controlled to mitigate uneven sampling; models of expected record intensity summarised differences among habitats and management levels after accounting for elevation and spatial structure; and habitat-stratified elevation curves quantified optima and tolerance ranges that were directly interpretable in the field. Relations between communities and environment were summarised by constrained ordination, and indicator testing was performed at species and higher ranks with appropriate control for multiple comparisons. Model generalisation was appraised using spatially blocked evaluation and by repeating fits after excluding each country in turn, thereby gauging the stability of effect directions across geopolitical units. Habitat-structured inventory designs of this kind provide an indirect yet necessary baseline for resolving cryptic diversity and interpreting functional turnover across management gradients [

21]. Transferability was evaluated explicitly so that indicator knowledge can be applied at the European scale and read through habitat and elevation.

The study clarified that habitat composition was a dominant organiser of assemblages relative to management intensity once effort and broad spatial structure were considered, with elevation shaping responses in a habitat-specific manner. It yielded compact, elevation-aware indicator sets: species-level indicators were suited to fine-grained assessments where taxonomic expertise and fruiting material permit, whereas robust genus-level signals can be deployed where species identification is a bottleneck. It also provided an explicit account of generalisation: cross-validated predictions were conservatively calibrated, yet the directions of habitat and management effects remained stable across countries, an important property for transferring indicator knowledge between regions and for designing gap-filling surveys.

More broadly, a harmonised, georeferenced corpus can advance the ecological interpretation of slime moulds in forests without over-engineering models or fragmenting categories. By concentrating on forest habitat, management intensity, and elevation, which jointly modulate moisture regimes, substrate supply and microclimatic buffering, the analysis linked substrate affinities to operational indicators. The indicator sets and elevation curves can be read directly onto routine field contexts (for example, dead wood retention, canopy openness, and montane versus lowland settings) and provide a reproducible baseline against which future changes in forest structure and climate can be tracked. As additional data become available, the same framework can absorb more detailed substrate descriptors and microhabitat information while retaining comparability with the present results, thereby supporting an iterative programme of bioindication using slime moulds across European forests. Taken together, these properties provide a robust continental-scale foundation for developing Europe-wide bioindication schemes based on slime mould assemblages, rather than a fully standardised system at this stage, and underline the importance of making the habitat and elevation structure explicit in any application.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

This study used the Georeferenced Checklist and Occurrence Dataset of Slime Moulds (Eumycetozoa) Across Central and Eastern Europe Emphasising Forest Ecosystems, published as a Darwin Core Archive under a CC-BY-4.0 licence [

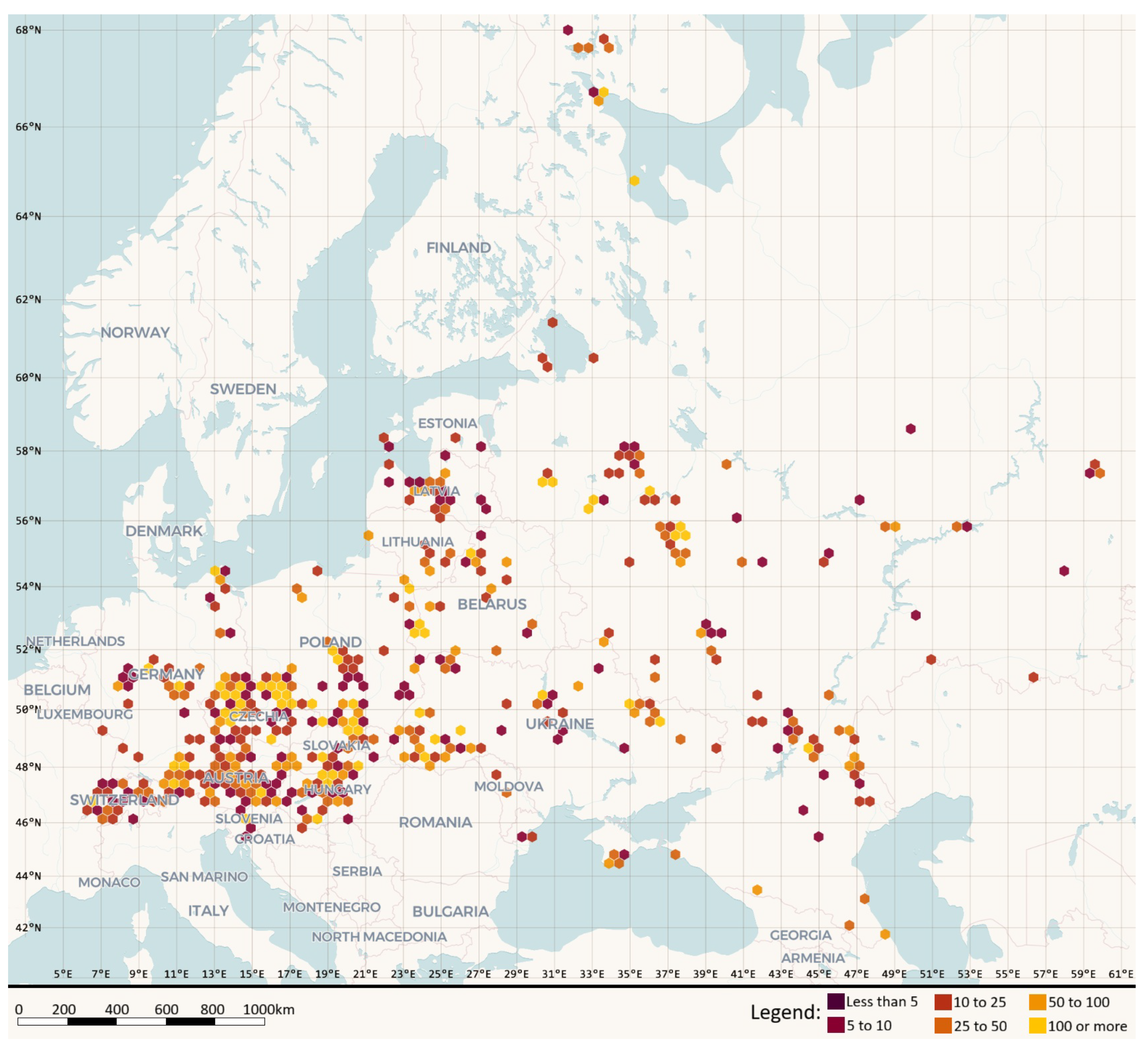

20]. The resource comprised presence-only occurrences paired with a taxonomically standardised regional checklist and full bibliographic provenance. Spatial coverage spanned 16 countries in Central and Eastern Europe, and temporal coverage extended from 1857 to 1 August 2025 with mixed date precision. Georeferencing followed WGS84 with explicit uncertainty metadata, providing traceable spatial information suitable for regional ecological analyses. Spatial coverage and sampling intensity are shown in

Figure 1, where records are aggregated to 20 km hexagons across Central and Eastern Europe.

Taxonomic usage was harmonised against the online nomenclatural information system Eumycetozoa.com [

4], with the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) backbone [

22]; used as a fallback, and higher ranks were completed consistently so that summaries and indicators could be derived at the species, genus, family, and order. Controlled vocabularies central to this study included eight consolidated forest habitat classes, seven management intensity classes, and ten substrate categories, ensuring coherence across sources and countries.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of Eumycetozoa records aggregated to 20 km hexagons; colour classes show counts per hexagon (0, 1–5, 6–10, 11–20, 21–50, 51–100, 101–200, >200). Base map rendered with MapLibre GL JS, generated in kepler.gl [

23].

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of Eumycetozoa records aggregated to 20 km hexagons; colour classes show counts per hexagon (0, 1–5, 6–10, 11–20, 21–50, 51–100, 101–200, >200). Base map rendered with MapLibre GL JS, generated in kepler.gl [

23].

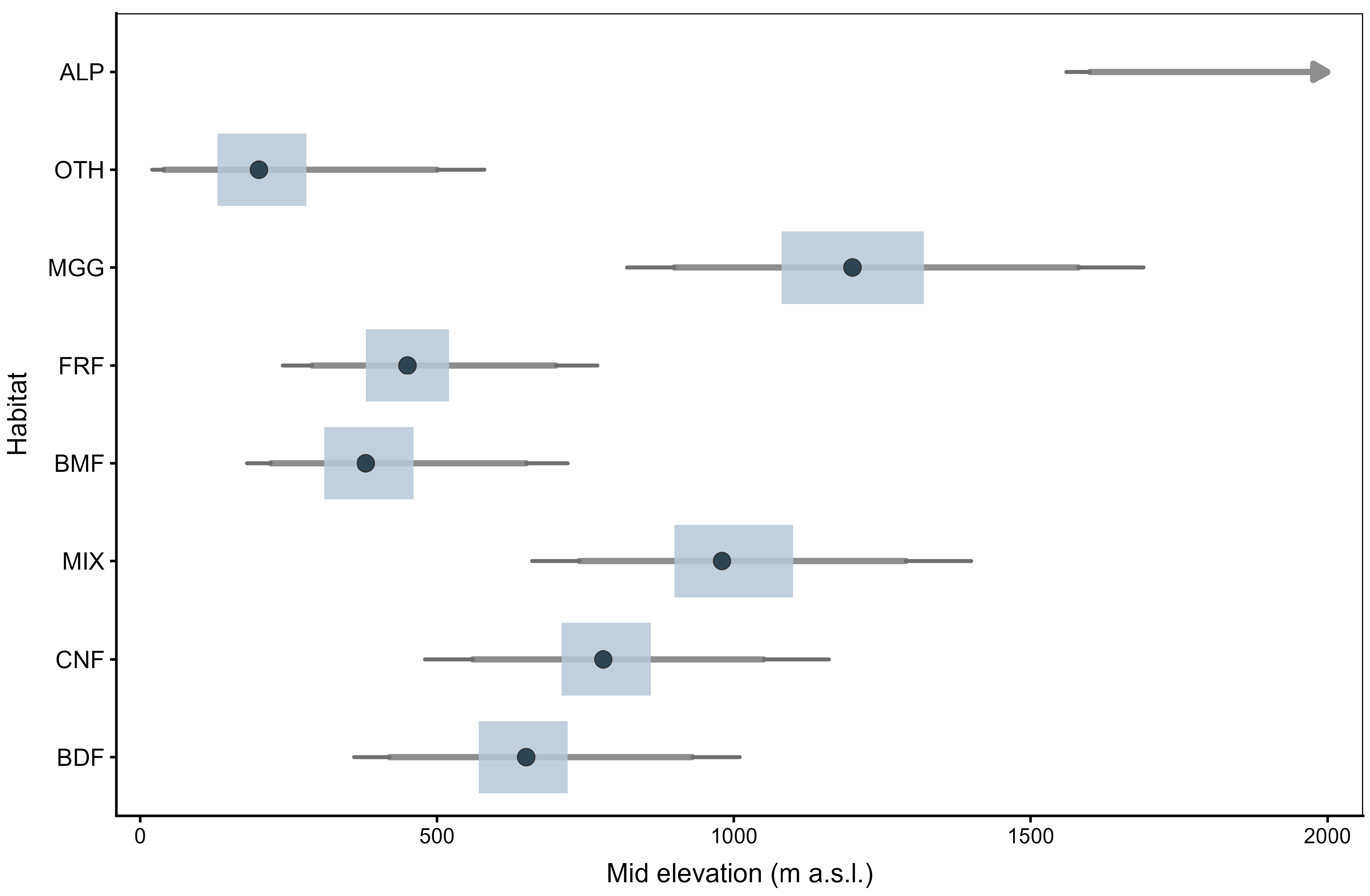

Environmental and contextual attributes were curated to support forest-focused analyses. Location was recorded as geographic coordinates in decimal degrees (, ). Terrain context was provided by minimum elevation above sea level () and maximum elevation above sea level (); from these, a midpoint elevation was derived as a continuous covariate (), and a three-level elevation band was defined for analysis (<300 m, 300–1000 m, >1000 m; ). Climatic context included near-surface air temperature in degrees Celsius () and annual precipitation in millimetres per year (). Chemical conditions were represented by acidity (), recorded as a unitless measure. The stand structure was captured by stand age in years () and a detailed forest type descriptor (). Habitat classification was provided as a consolidated forest class (), while anthropogenic influence was encoded as a management intensity class (). Substrate context distinguished broad substrate categories relevant to trophic stages and sporulation (), and a fine-grained microhabitat field () documented immediate occurrence context (for example bark, coarse woody debris, and litter). Administrative and grouping fields included country, alongside the taxonomic ranks used for summaries (order, family, genus, and species).

Data ingestion and harmonisation were performed in R (RStudio, version 4.5.2). Numeric fields were standardised (including tolerance to comma decimals); was rounded to two decimal places for consistency; and the derived midpoint elevation () and elevation bands () were created from the reported elevation bounds. Quality control assessed the completeness of key descriptors (country, coordinates, species, consolidated forest class, management intensity, and elevation), validated coordinate domains, ensured non-negative precipitation, and checked the logical ordering of elevation bounds. Several contextual attributes, particularly air temperature, precipitation, , and stand age, were present for fewer records, reflecting limited reporting in many primary sources; consequently, these fields were treated as optional covariates and used only in sensitivity analyses rather than as core predictors in the primary models. The controlled vocabularies and harmonised structure aligned directly with the study’s focus on habitat, management intensity, and elevation, while the substrate and microhabitat descriptors provided the contextual basis for interpreting substrate affinities and assembling indicator sets.

Voucher specimens of Eumycetozoa from Central and Eastern Europe are primarily held in national and university fungaria and herbaria, many of which are progressively being digitised in community portals such as MyCoPortal. No additional field collections were made specifically for this synthesis; rather, the Darwin Core archive re-uses these existing holdings as mobilised through the primary literature and collection databases. Because the resource spans more than 150 years of collecting and draws on numerous primary sources, a complete crosswalk to all individual repositories and exsiccata series lies beyond the scope of this paper; instead, voucher information is retained in the original publications and in the metadata of the Darwin Core archive, which is intended as a living resource. The GBIF-hosted version of the dataset [

20] is updated as new inventories and clarifications become available and will, in future iterations, incorporate explicit herbarium and fungarium codes.

Several regions of Central and Eastern Europe remain comparatively poorly surveyed for slime moulds, and the present dataset therefore also serves to highlight spatial gaps in available information. Recent and ongoing inventories from Northern and North-eastern Poland, including the Białowieża Forest, Wigry National Park, Biebrza National Park, and swamp forest stands of the Knyszyn Forest, illustrate that these areas have only recently begun to accumulate systematic records of Eumycetozoa and still require intensive further survey and analysis [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. As new inventories from such under-sampled regions become available, they can be incorporated into updated versions of the Darwin Core archive and will progressively reduce the spatial imbalance in coverage.

2.2. Environmental Classification: Consolidated Forest Classes and Management Intensity

To obtain statistically comparable and interpretable results across heterogeneous sources, habitat descriptors and management terms were harmonised a priori into two controlled vocabularies: consolidated forest habitat classes (

Table 1) and management intensity classes (

Table 2). The consolidation addressed divergent national typologies and fine-grained phytosociological labels that would otherwise fragment the dataset into many sparse categories and compromise representativeness. A many-to-one crosswalk mapped original labels to eight ecologically coherent forest habitat classes aligned, where relevant, with Natura 2000 Annex I habitat codes; management settings were standardised to seven intensity levels reflecting gradients of naturalness, silvicultural intervention, and substrate or soil modification.

Habitat classes followed the consolidation proposed by Pawłowicz et al. [

30], whereas the management intensity “pressure” framework was introduced here as a complementary categorisation specific to this study. For modelling and graphics, classes were encoded with stable three-letter codes (habitat: BDF, CNF, MIX, ALP, BMF, FRF, MGG, OTH; pressure: PRI, NEA, SEM, MAN, PLN, PLT, ART). Operationally, this pressure gradient spans from strictly protected, structurally complex stands with high volumes of dead wood and minimal direct intervention (PRI–NEA), through semi-natural and multi-use forests, where management and planting are present but stand structure remains comparatively heterogeneous (SEM–MAN–PLN), to plantation and artificial settings (PLT–ART) characterised by simplified species composition, short rotations, regular spacing, and strongly reduced amounts of dead wood and other microhabitats.

Assignments followed explicit decision rules recorded with the dataset. Original phytosociological or habitat terms were matched to the nearest overarching class using vegetation structure, tree dominance, hydrology, and elevational context; when provided, Natura 2000 codes guided the mapping. Where local labels mixed features of two classes, precedence was given to the dominant structural or hydrological signal (for example, bog woodland to BMF). Management intensity levels were assigned from source descriptions of logging history, planting, rotation structure, stand age distribution, dead wood volume, and hydrological alteration. These consolidations reduced category sparsity, enabled effort-controlled comparisons, and supported robust estimation and indicator testing while preserving traceability to verbatim labels.

Together, these crosswalks ensured that habitat and management information drawn from diverse sources was reduced to parsimonious, ecologically meaningful classes with adequate sample sizes. The stable codes were used consistently in figures, tables, and model summaries, and the definitions enabled the transparent replication of assignments for future updates.

2.3. Data Assembly and Scope Definition

All data ingestion, harmonisation, and analyses were conducted in R (RStudio). Required columns were checked explicitly, numeric fields were standardised with tolerance to comma decimals, and was rounded to two decimal places. A mid-elevation variable () was computed as the midpoint of reported minimum and maximum elevations, and a three-level elevation band () was defined a priori as <300 m, 300–1000 m, and >1000 m. Core variables were typed as factors where appropriate, with treated as an ordered factor. A variable dictionary summarised class, completeness, ranges, and numbers of levels, and an analysis scope table designated , , , and as focal predictors. Country was treated as a grouping or random effect. and (mm y) were optional covariates; , , , and were excluded from primary analyses and reserved for sensitivity checks; (years) was contextual; order and family were treated as descriptors. Substrate, microhabitat, and effects are therefore not modelled explicitly in the present paper but are being examined in detail in a separate companion analysis based on the same Darwin Core archive; here we focus on habitat-, management-, and elevation-structured responses to keep the models tractable and the exposition centred on continental-scale patterns. Habitat and management labels were mapped to strict three-letter codes (, ) for modelling and summaries.

2.4. Quality Control and Preprocessing

Quality control used a conservative, rule-based framework. Mandatory completeness was verified for country, coordinates, species, consolidated habitat class, management intensity, and mid-elevation. Exact duplicates (same species, , , year, location, and source) were flagged and retained in the raw table; downstream analyses applied within-unit de-duplication so that each species contributed a single presence per analysis unit. A quality control ledger reported duplicate flags by country (3.3% of rows overall). Elevation records with were marked for removal, and elevation outliers were flagged using the rule. Where any filter risked breaching the row-count guardrail, rows were flagged rather than dropped. A quality control snapshot tabulated counts by , , , and country.

2.5. Analysis Units, Response, and Effort

Analysis units were defined as the cross-classification of country, year,

,

,

,

, and

. For modelling and incidence summaries, the response (

) was computed after collapsing exact duplicates within a unit so that multiple identical occurrences contributed a single presence to that unit. Sampling effort at the country-by-year scale (

) was defined as the total number of Eumycetozoa records available for that country and year, and the exposure term was set to

Under this convention, at prediction corresponds to one unit of standardised effort per analysis unit. Stable unit identifiers were generated by concatenating the unit-defining fields. A machine-readable table documented the analysis unit, response, effort, and offset definitions. For the higher taxon indicator analysis, the same unit definition (including year) was used, and normalised country-by-year totals informed the weights.

2.6. Representativeness, Richness and Elevation Summaries

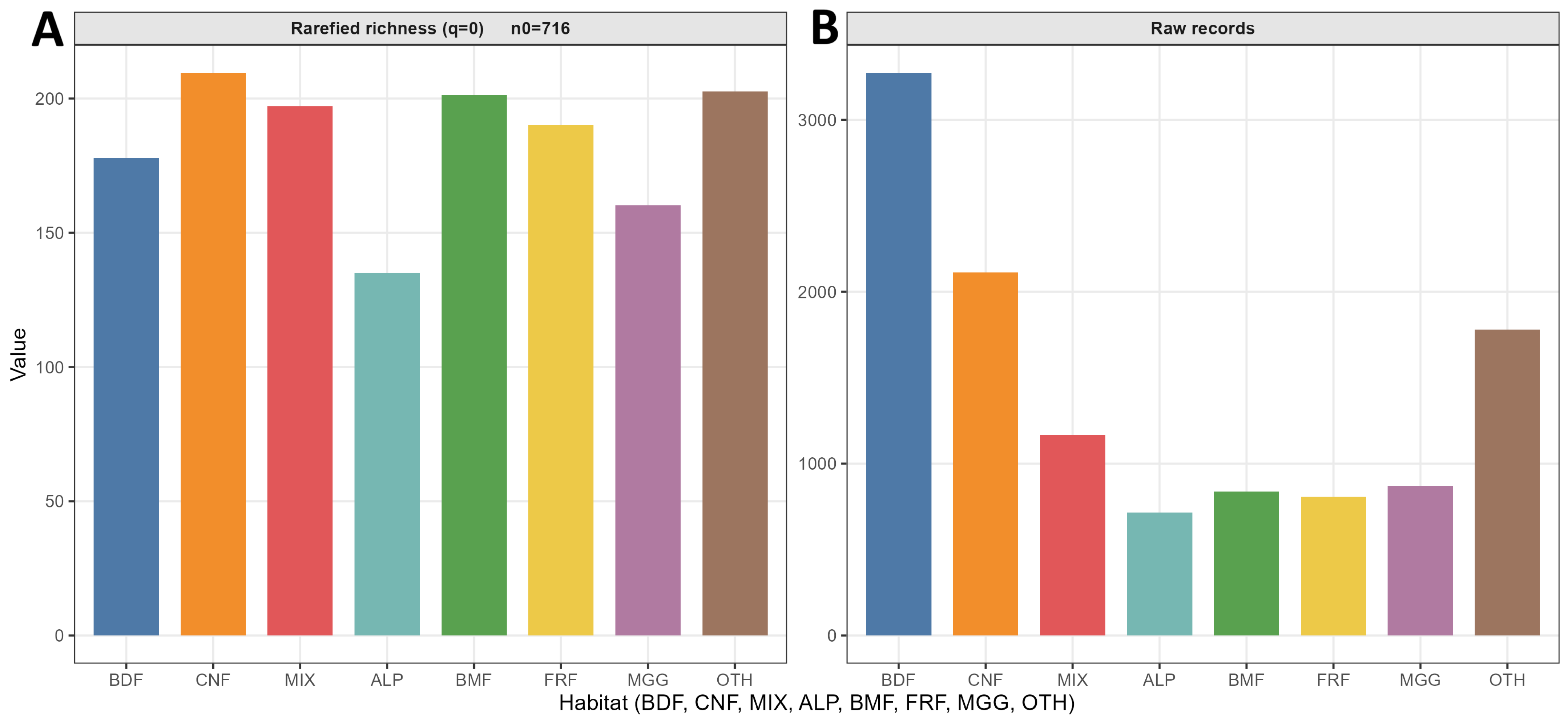

Representativeness was assessed by cross-classifying with , both overall and stratified by country. For each stratum, the record count (), species count (), and the number of singletons () were computed. The analysis unit served as the replicate for each grouping (habitat, pressure, and elevation), yielding incidence–frequency vectors supplied to iNEXT/estimateD (datatype = incidence). Sample coverage for incidence data was estimated with the incidence-based estimator implemented in iNEXT; group contrasts used a common coverage target where attainable, and groups not reaching were reported at their maximum attained coverage.

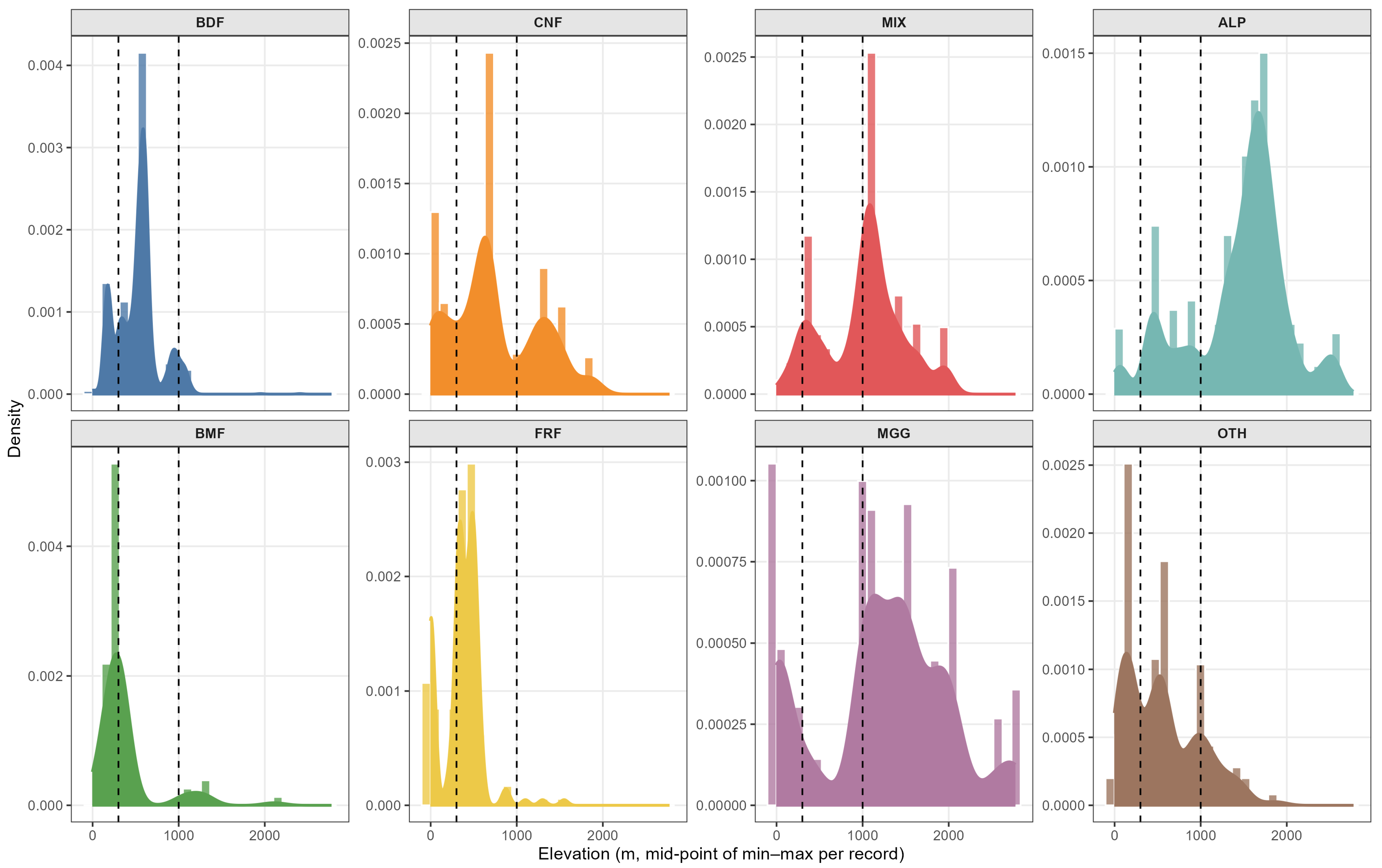

Alpha diversity (Hill numbers; , , ) was estimated from incidence with coverage-based standardisation. Main figures report coverage parity. Elevational distributions used as defined above.

2.7. Modelling Frameworks for Eumycetozoa Intensity

Counts of Eumycetozoa records per analysis unit were modelled with a zero-truncated negative binomial generalised additive mixed model (ZTNB GAMM) on the support, conditional on units with at least one record. The specification estimated a standardised record yield per analysis unit rather than an incidence rate per exogenous effort. Categorical effects were included for

and

, together with a temporal smooth

, habitat-specific elevation smooths

, a spatial smooth

, a country-level random effect, and a country-by-year fixed effect

to capture residual effort differences by year. The linear predictor was

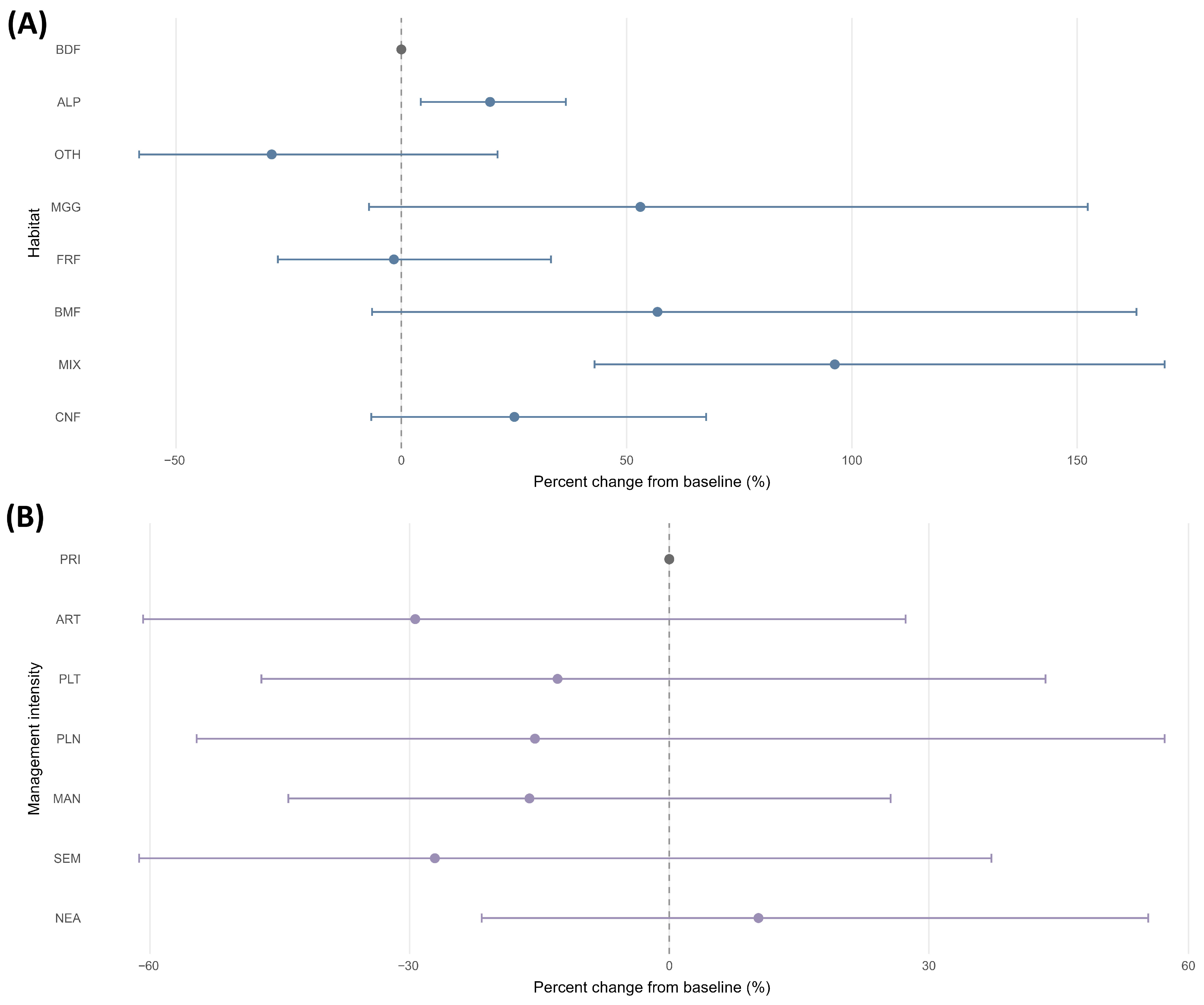

Smoothing parameters were estimated by restricted maximum likelihood. The longitude–latitude smooth used a reduced thin plate basis () with shrinkage to avoid absorbing residual effort gradients. Predicted means were obtained on the response scale at the median elevation and location with the country random effect excluded. Link-scale contrasts to the baselines (BDF for , PRI for ) were reported as percentage changes with 95% Wald confidence intervals. Under the adopted normalisation, at prediction corresponds to one unit of standardised effort per analysis unit.

As a complementary sensitivity framework, negative binomial generalised linear models (log-link) were fitted to the count of species presences per analysis unit. These models included an effort offset based on log country–year totals and a natural spline term for elevation (df = 4). Sensitivity variants used centred and scaled climate covariates with thin plate regression spline terms under shrinkage penalties and a low basis () for , , and . Model selection relied on AICc and concurvity diagnostics; climate terms were retained for sensitivity summaries only. Baselines were set to BDF () and PRI (). Sensitivity to modelling choices was evaluated across four variants: A (no climate covariates), B (with climate covariates), C (representativeness weights for sparse cells), and D (Huber-type robust weights from Pearson residuals). For each level, rate ratios (RR) and 95% confidence intervals were obtained by exponentiating model coefficients; percentage drift in RR relative to variant A was summarised.

2.8. Post Hoc Estimation and Factor Contrasts

Estimated marginal means for

and

were computed at the median elevation and location, with

(one unit of standardised effort per analysis unit) and the country random effect excluded, to obtain population-level contrasts. All pairwise contrasts were obtained with Tukey adjustment for multiplicity [

31]. For each contrast, link-scale differences were expressed as percentage change with Tukey-adjusted 95% confidence intervals and

p values. Labels were harmonised to strict three-letter codes; empty or missing values were omitted from outputs.

2.9. Elevation Responses

Elevation responses of Eumycetozoa intensity were analysed within the same ZTNB GAMM structure, with habitat-specific elevation smooths alongside fixed effects for and , spatial smooths, a temporal smooth , and a country random effect. For the alpine or subalpine class (ALP), a thin plate regression spline with shrinkage was used so that the elevation curve could shrink towards zero where support was sparse, while remaining estimable. Partial dependence predictions were obtained on habitat-wise elevation grids spanning the central observed range, with longitude and latitude set to their medians and interpreted as one unit of standardised effort. For each habitat, the optimum was defined as the grid point maximising the fitted curve on a dense grid (10-m step within the observed domain). The 80% tolerance was defined, within the observed elevation domain, as the narrowest interval where the predicted intensity was at least 80% of the habitat-specific maximum. Uncertainty was quantified by a parametric bootstrap from the fitted ZTNB GAMM ( coefficient draws); for each draw, the grid was re-evaluated, the optimum and the 80% tolerance were re-extracted, and 95% confidence intervals were summarised. Monotonic or flat-top curves (no interior maximum) were flagged as having no interior optimum; for these, tolerance was reported where definable and the optimum point was omitted.

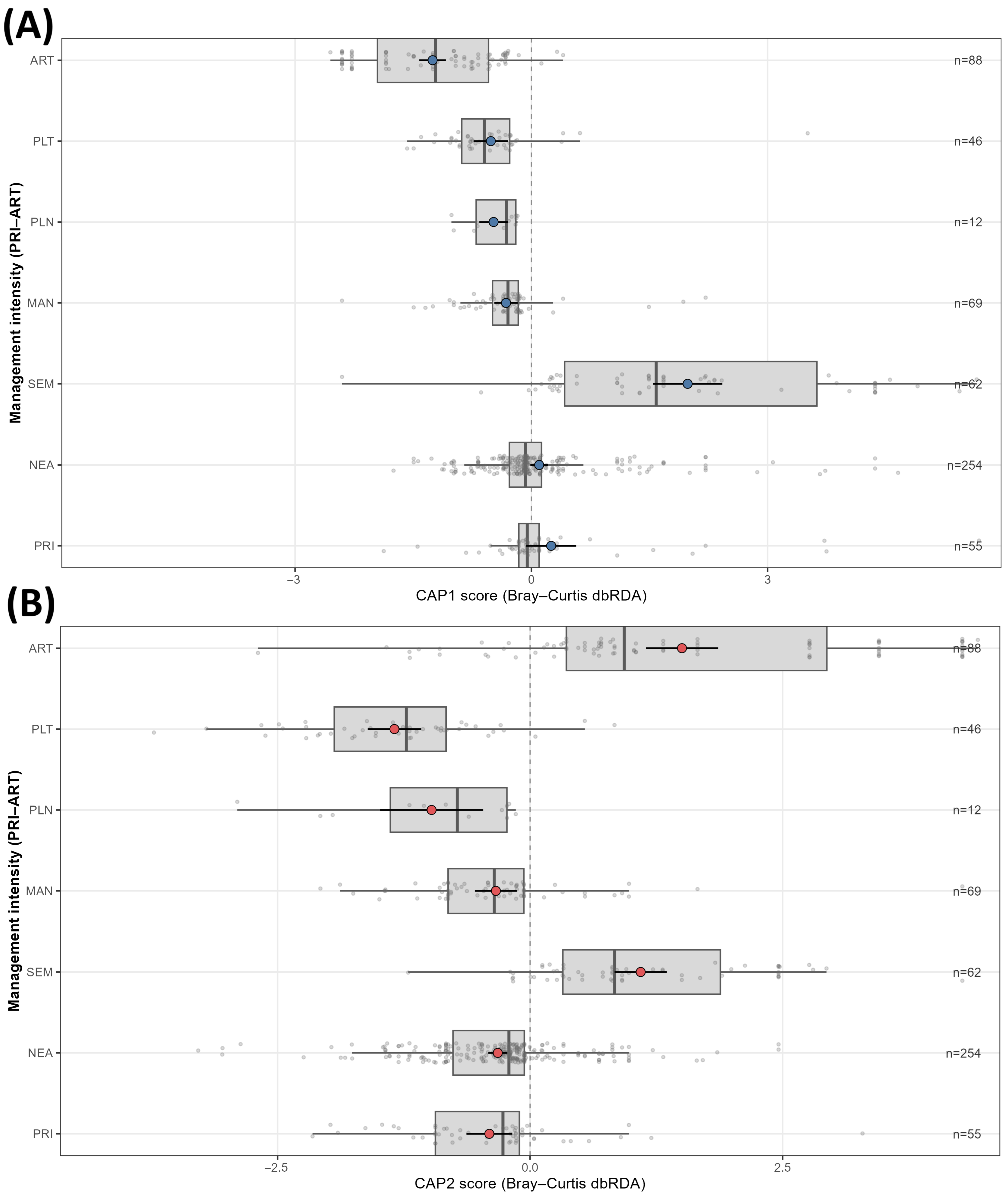

2.10. Community Structure and Indicator Analyses

Community–environment relations were evaluated using distance-based redundancy analysis (Bray–Curtis dbRDA) implemented as a constrained analysis of principal coordinates (CAP) on a presence–absence species matrix at the analysis unit level. For management intensity, a partial dbRDA was performed with as the constraint and as the conditioning matrix. Significance was assessed with 999 permutations constrained within countries. Because analysis units are spatially structured, p values were interpreted conservatively.

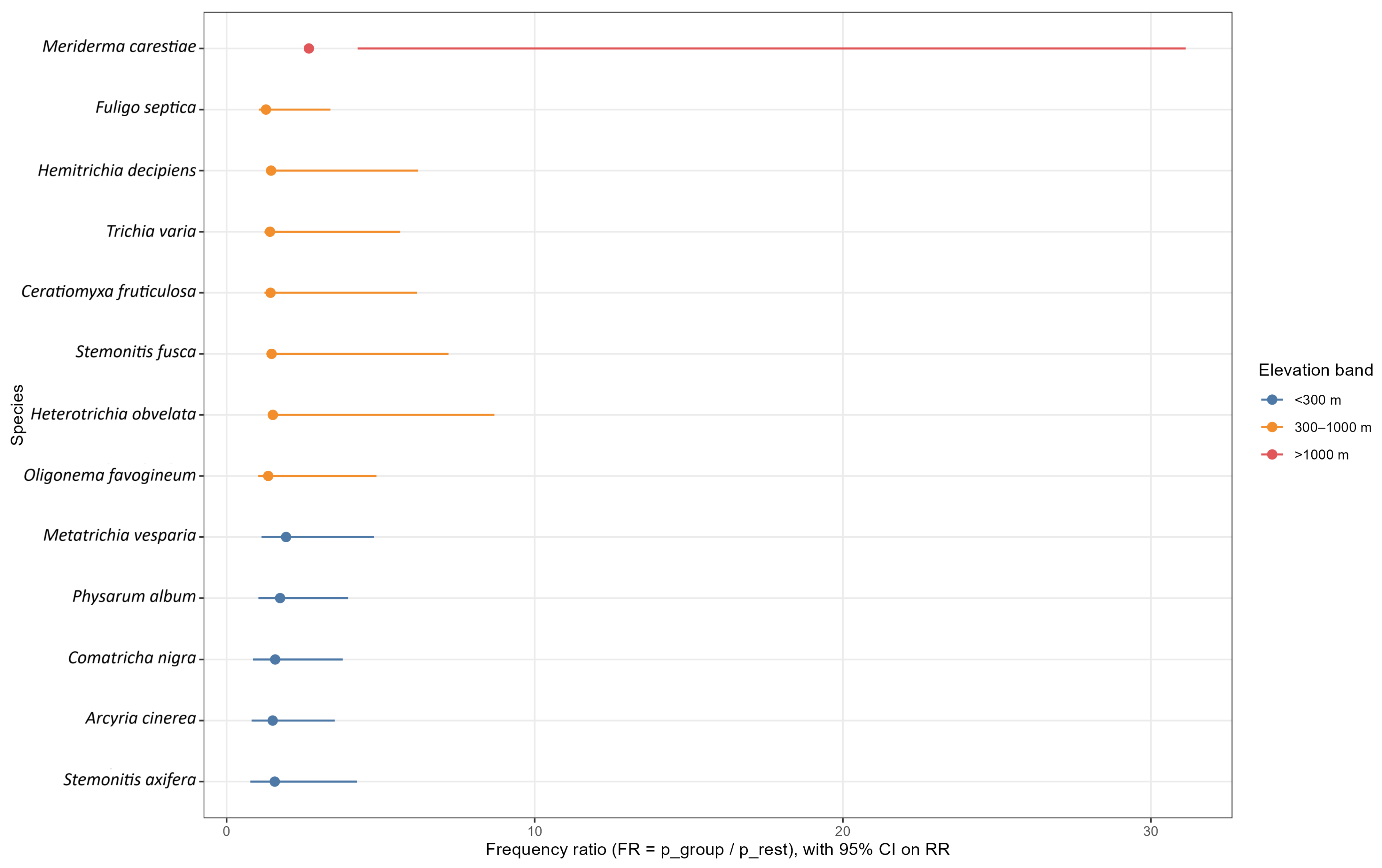

Indicator development proceeded at two resolutions. First, indicator species for , , and were identified using with effort-proportional weights. For management intensity, inference controlled for habitat via country-by-habitat-stratified permutations (999) within countries. Benjamini–Hochberg adjustment was applied within each dimension, and emphasis was placed on effect directions and adjusted significance.

Secondly, effort-weighted association testing identified higher taxon indicators (family, genus, order) across the same dimensions. Presence (at least one record per unit) was aggregated to the focal rank; only taxa occurring in at least 25 units across at least three countries were evaluated. For each taxon and candidate group, a Mantel–Haenszel common odds ratio stratified by country () was estimated, with a Haldane 0.5 continuity correction applied within any country stratum containing a zero cell. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals were obtained on the log scale from the Mantel–Haenszel variance and then transformed back. Two-sided p values used the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test and were adjusted within dimension using Benjamini–Hochberg. The group with the largest positive was reported per taxon, and top sets were presented by rank and dimension.

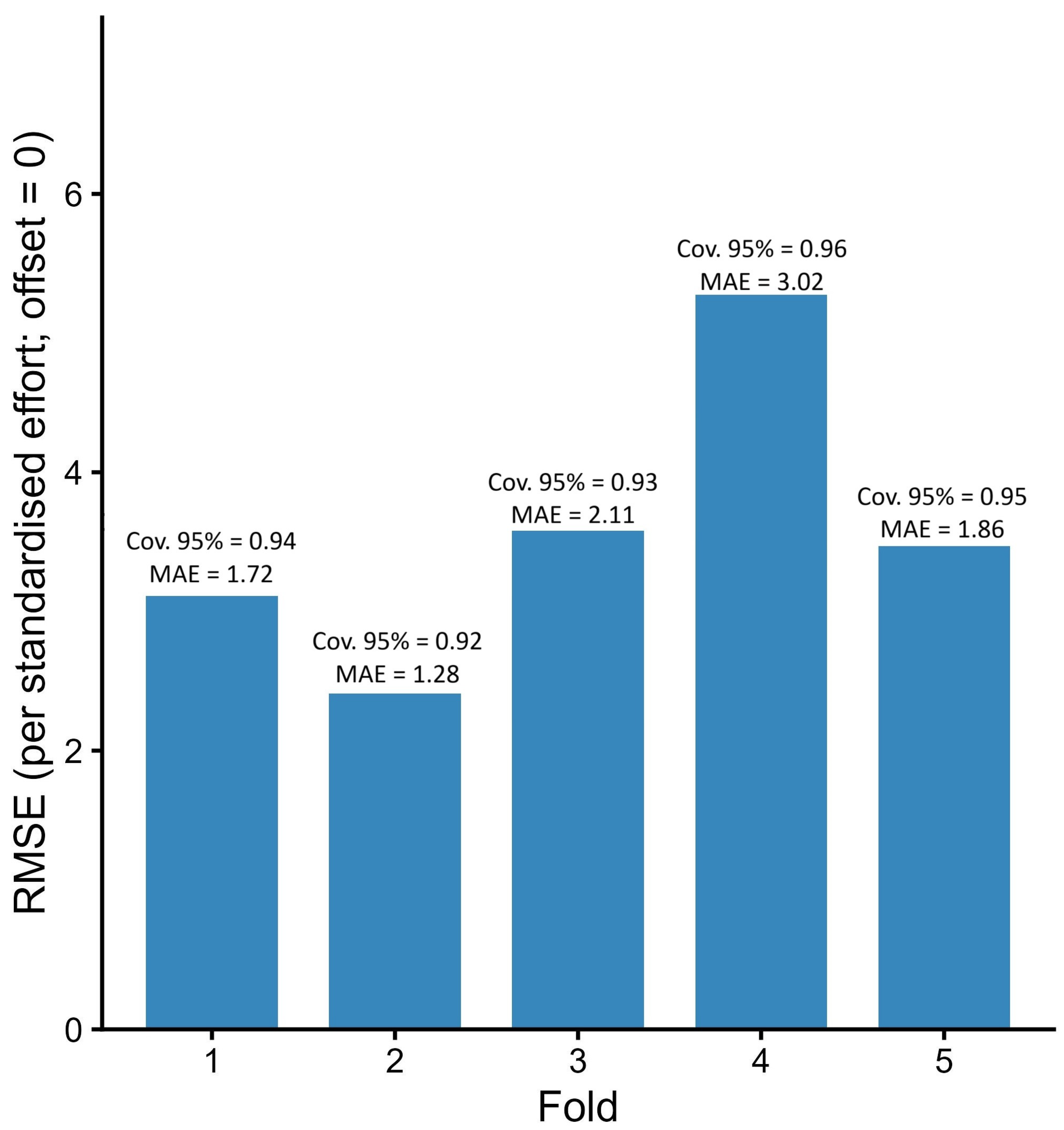

2.11. Diagnostics, Cross-Validation, and Robustness

Pearson residuals from count models were summarised using histograms with a fixed bin width of 2 and a symmetric display cap of 50 in each direction on the x-axis, comparing zero-truncated Poisson (ZTP) and zero-truncated negative binomial (ZTNB) specifications fitted with the normalised exposure offset.

Model generalisation and stability were evaluated by refitting the ZTNB GAMM of record intensity under a five-fold, country-stratified spatial block cross-validation (block size 275 km). For each held-out fold, raw mean calibration by deciles (mean observed versus mean predicted) was computed, an isotonic regression of observed on predicted means was fitted (monotonic, no intercept), and 95% prediction intervals were generated by parametric simulation from the fitted ZTNB model (including the estimated dispersion; 2000 draws per unit). Predictions excluded the country random effect to yield population-level transfer and used (one unit of standardised effort). Root-mean-squared error, mean absolute error, and empirical 95% coverage were reported, and both 1:1 and isotonic calibration lines were displayed.

Spatial structure in Pearson residuals was examined using an empirical semivariogram and distance-binned Moran’s I. Effect robustness was assessed by leave-one-country-out refits, computing link-scale contrasts at the median elevation and spatial location against the model baselines (BDF for , PRI for ) and reporting these as percentage changes.

5. Conclusions

This study showed that Eumycetozoa responded coherently to habitat composition, management intensity, and elevation, and that these responses could be harnessed for bioindication and forecasting. At the European scale, the evidence supports using slime moulds as a promising bioindicator group and offers a solid, continental-scale basis for the future development of universal Europe-wide indicators, provided that assessments are stratified by habitat and elevation and interpreted at an appropriate taxonomic resolution.

Forest habitat acted as the principal organiser of Eumycetozoa intensity. Mixed stands were higher than broadleaved baselines; riparian settings were broadly comparable, and non-forest or anthropogenic contexts were consistently lower. Elevation further modulated these differences within habitats. Management intensity influenced assemblages, but the signal was secondary and model dependent; departures from primary or old growth were modest and often statistically indistinct once effort and broad spatial structure were controlled, so management information should refine rather than replace habitat information in bioindication.

Coverage-standardised diversity patterns were congruent with the intensity contrasts. Coniferous habitats were richest across Hill orders; alpine or subalpine habitats were poorest; near-natural management exceeded planted systems; and richness peaked at mid elevations. In contrast, diversity weighted towards common species was greater at low elevations. Because elevation effects were habitat-specific, optima and tolerances differed among habitats and several responses approached gradient bounds, implying near-monotonic behaviour within the sampled ranges; elevation-aware interpretation was therefore essential.

At the habitat scale, bioindication was strongest at the species level yet scalable across ranks. Species such as Trichia varia, Fuligo septica, Hemitrichia decipiens, Stemonitis axifera, and Arcyria cinerea typified broadleaved contexts; Lycogala epidendrum characterised mixed forests; Stemonitis fusca was associated with bogs, mires, and fens; and Meriderma carestiae with meadows, grasslands, and glades. At the genus level, Meriderma, Polyschismium, and Badhamia were most informative across habitats; at the family level, Liceaceae (broadleaved deciduous), Didymiaceae (meadows, grasslands, and glades) and Cribrariaceae (conifer linked) provided robust signals; and at the order level, Trichiales and Cribrariales typified broadleaved habitats, whereas Physarales characterised non-forest or anthropogenic settings.

For management intensity, bioindication was clearest at higher ranks. The genera Meriderma and Polyschismium diagnosed semi-natural contexts, whereas Stemonitis indicated planted systems. At the family level, Didymiaceae aligned with semi-natural conditions and Physaraceae with anthropogenic settings; at the order level, Physarales typified artificial or converted sites. Because elevation partitioned indicator assemblages, complementary sets emerged across bands: at low elevations, species such as Metatrichia vesparia, Physarum album, and Arcyria cinerea; at mid elevations, Hemitrichia decipiens, Trichia varia, and Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa; and at high elevations, Meriderma carestiae was dominant. At the genus level, Meriderma and Polyschismium concentrated above 1000 m, whereas Ceratiomyxa and Hemitrichia peaked at mid elevations; at the family level, Ceratiomyxaceae were strongest at mid elevations, and Didymiaceae at high elevations; and at the order level, Cribrariales characterised low elevations, Ceratiomyxales mid elevations, and Stemonitidales high elevations.

Assemblage composition shifted systematically with increasing pressure, mirroring indicator patterns across ranks and supporting multiscale application in assessment and monitoring. Because out-of-sample calibration was conservative under spatial block cross-validation, forecasts based on these indicators should adopt appropriately cautious uncertainty bounds. Climate augmented sensitivity fits, centred and scaled with shrinkage and a low basis (), were stable, altered key contrasts by < and improved AICc only marginally, so parsimonious effort offset models with elevation terms remained preferable for operational use, with climate retained as a sensitivity layer.

Representativeness conditioned the precision of inference. Well-sampled strata yielded the most reliable indicators, whereas sparse habitat-by-pressure combinations should be interpreted with caution. Substrate-focused analyses were intentionally deferred to a companion paper; here, habitat and management classes served as operational proxies for substrate regimes. From the standpoint of forest management, the present analysis should be viewed as an initial, quantitative step towards integrating Eumycetozoa-based information into existing assessment frameworks rather than as a fully specified bioindication system. By documenting how indicator assemblages vary with broad habitat classes, management intensity and elevation, the study provides a basis for refining the ecological characterisation of slime moulds along gradients of habitat naturalness and anthropogenic pressure and for exploring their potential use as supplementary indicators of forest habitat type and stand “naturalness”, for example in relation to environmental pressure and the amount of dead wood in managed forests. Realising this potential will require further targeted sampling and finer-scale typologies, especially at the level of national forest habitat classifications, before explicit thresholds or decision rules can be embedded in policy, certification, or forest management schemes. Finally, the directions of habitat and management effects were stable across countries, and the elevation responses and indicator sets were transferable at the European scale, supporting the use of slime mould assemblages as a continent-wide bioindicator framework in forest monitoring and forecasting and providing a solid basis for future efforts towards universal Europe-wide standardisation, while stopping short of a formal, fully standardised system at this stage.