Abstract

The nitrogen (N) uptake preferences of mature tropical trees remain poorly understood, largely because traditional hydroponic methods fail to adequately simulate field conditions. To address this, we applied an in situ whole-tree paired 15N labeling experiment to quantify N acquisition strategies in three common species of tropical plantations in southern China: Hevea brasiliensis, Pinus caribaea, and Acacia mangium. The in situ whole-tree paired 15N labeling experiment revealed distinct species-specific nitrogen uptake strategies: Hevea brasiliensis preferentially absorbed nitrate (contributing 76% to total N uptake), Pinus caribaea relied more heavily on ammonium (61%), while Acacia mangium exhibited no strong preference for either N form but demonstrated the highest N uptake rate. These findings indicate the significant role of mycorrhizal type and biological nitrogen fixation in shaping N uptake patterns. Importantly, even when accounting for the dilution by the soil nitrogen pool, nitrate still contributed 42–99% of the total nitrogen uptake across the three tree species. All three species showed a substantial capacity for nitrate assimilation, challenging the conventional view of ammonium dominance in tropical trees and providing a mechanistic basis for refining nitrogen management practices in plantation forestry.

1. Introduction

Planted forests serve as a significant component of China’s forest carbon sink. The expansion of planted forest areas is considered a major strategic initiative for achieving peak carbon and carbon neutrality [1]. Benefiting from favorable hydrothermal conditions and abundant solar radiation, southern China has developed into the primary plantation region in China, accounting for approximately 63% of the total plantation area nationwide [2]. However, the widespread practice of monoculture plantation management in this region has led to a decline in soil nitrogen (N) availability [3], resulting in a N supply deficit that struggles to meet the high demands of rapidly growing plantations. This N limitation restricts the sustained enhancement of productivity in plantation ecosystems. In this context, elucidating N acquisition strategies of common tree species in tropical plantations becomes a central scientific question for improving N use efficiency and maintaining long-term carbon sequestration capacity in plantations.

For tropical trees, the long-standing consensus holds a strong preference for ammonium (NH4+) over nitrate (NO3−) [4]. However, this view is not without uncertainties. Tree nitrogen uptake strategies are governed by a complex interplay of physiological trade-offs and biotic associations. Plants primarily take up ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) from the soil, while the physicochemical properties of inorganic N influence their assimilation: while ammonium assimilation is traditionally considered energetically less costly and faster [5,6,7], excessive NH4+ absorption may induce phytotoxicity that partially offsets its energetic advantages [8]. In contrast, nitrate exhibits greater mobility in soil, thereby enhancing its accessibility to roots [9,10]. Additionally, mycorrhiza types significantly shape tree N uptake strategies. Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) tree species often exhibit a greater capacity for nitrate uptake [11,12,13], whereas trees associated with ectomycorrhizal fungi (ECM) tend to prefer ammonium [14,15,16]. Thus, the interactions among physiological trade-offs, such as assimilation cost versus toxicity, edaphic mobility, and mycorrhizal symbiosis, collectively determine N acquisition strategies, contributing to the uncertainty in predicting plant N uptake preferences.

The limitations of methodologies in previous studies have further exacerbated the current uncertainty regarding conclusions on tree nitrogen uptake preferences. Most prior research predominantly relied on hydroponic experiments, in which seedlings or excised roots from mature trees were exposed to 15N-labeled solutions to assess N uptake [17,18]. However, such hydroponic methodologies fail to account for soil microbial competition for ammonium and nitrogen immobilization mediated by organic matter [19,20]. In addition, this approach overlooks organ-specific variation in N translocation and assimilation within plants. For example, nitrate is often transported via the xylem to leaves for reduction [21], whereas ammonium is primarily assimilated in roots [22]. Consequently, hydroponic methods using excised roots tend to overestimate the NH4+ uptake capacity of trees and inadequately reflect the N utilization strategies of mature trees under field conditions.

Recently developed in situ 15N paired-labeling techniques for mature trees provide a robust methodological framework for accurately determining tree N uptake preferences [23]. This approach integrates rhizospheric processes, nitrogen transformations, and whole-plant nitrogen allocation, having been successfully implemented in temperate conifers of northern China [23,24]. The results from these studies indicated that conifers assimilate 39%–90% of nitrogen as nitrate (NO3−), contrasting sharply with the ammonium preference suggested by earlier hydroponic experiments. Nevertheless, this methodology has not yet been employed to investigate N uptake in mature trees within tropical plantations, significantly hindering the development of precision nitrogen management practices in this region. Importantly, the high temperature, high humidity, and intensified soil leaching dynamics characteristics of southern China may substantially alter soil nitrogen availability and cycling processes [25], potentially leading to fundamental divergences in tree nitrogen acquisition strategies compared with those in temperate forests [4]. Therefore, a systematic investigation of N acquisition strategies in southern plantation species is imperative for optimizing forest management and enhancing plantation productivity.

Integrating differences in mycorrhizal associations and physiological traits, three representative tree species from southern tropical plantations, Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A. Juss.) Müll. Arg. (H. brasiliensis, an AM-associated latex-producing economic species), Pinus caribaea Morelet (P. caribaea, an ECM-associated fast-growing timber species), and Acacia mangium Willd. (A. mangium, an ECM-associated N-fixing species), were selected to investigate interspecific variation in N acquisition strategies. We hypothesized that (1) nitrogen uptake preferences are influenced by tree species traits and mycorrhizal type, with ECM species (e.g., P. caribaea) preferentially acquiring NH4+, AM species (e.g., H. brasiliensis) favoring NO3−, and the nitrogen-fixing A. mangium exhibiting no strong preference due to access to multiple N sources; and (2) regional climate conditions further drive divergence in N acquisition, whereby the warm, humid environment and accelerated nitrogen cycling in southern plantations promote greater reliance on NH4+ compared with northern temperate forests. To test these hypotheses, we employed an in situ whole-tree 15N labeling approach with the following specific aims: (1) to quantify and compare the N uptake strategies of these three species, and (2) to determine whether systematic differences in N acquisition correspond to mycorrhizal type and species traits.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

This study was conducted in the Jianfengling National Natural Reserve, on Hainan Island, southern China. The region is characterized by a tropical monsoon climate, with a wet season (from May to October) and a dry season (from November to April). Between 2009 and 2018, annual precipitation averaged 2414 mm (from 1637 mm to 3458 mm), and the mean annual temperature was 19.7 °C. The soil type is acidic lateritic. This experiment was performed in three plantations: H. brasiliensis, P. caribaea, and A. mangium. The plantation forests were all c. 30–40 yr. old.

2.2. Experimental Design

The labeling experiment was conducted in September 2024, during the late rainy season. This period corresponds to a key active growth phase for all species, yet with distinct phenological emphases: H. brasiliensis is in a phase of sustained vegetative growth, A. mangium is typically entering its flowering period, and P. caribaea is in a late growing and nutrient storage stage. Within each monoculture plantation, ten trees of similar diameter at breast height were selected and grouped into five pairs, with >10 m between any two pairs. Paired trees were spaced 5–10 m apart to minimize root system intermingling. For each pair, one tree received 15NH4NO3 (99.14 atom%, Shanghai Research Institute of Chemical Industry CO., LTD. Shanghai China) while the other received NH415NO3 (99.21 atom%, Shanghai Research Institute of Chemical Industry CO., LTD. Shanghai China). The 15N labeling dose of 50 mg 15N m−2 was added to a 1.5 m radius of each tree, thus each tree individual received 353.25 mg 15N (1.907 g N in total) dissolved in 7 L of tap water containing equimolar concentrations of ammonium nitrate, with either N form labeled (15NH4NO3 or NH415NO3).

To reflect realistic N uptake by mature trees in situ, we tried to minimize disturbance by using a custom-made metal net of 1.5 m radius gridded at 10 cm intervals to locate positions for the injection of 15N tracer solutions. Prior to injection, understory shrubs and grasses were cleared within the labeling area to limit non-tree root uptake. The 15N tracer solutions were injected into the mineral soil at a depth of 10 cm using a 50 mL syringe equipped with a side-hole needle, with injections made at 5 cm intervals. After finishing tracer injections, another 7 L of tap water (pH = 7, 0.153 mg NO3− L−1, 0.008 mg NH4+ L−1) was spread evenly over the labeling area (7.065 m2) to diffuse the 15N tracers. These tracer solutions and water additions were equivalent to 2 mm of precipitation.

Prior to 15N labeling, and 3 and 7 days after 15N tracer application, leaves, fine roots, and bulk soil within the 15N labeling area were sampled for analysis. For each sampling, at least one branch of the target trees was harvested from the middle crown; leaves and branches were separated. Mineral soil samples were extracted using an auger (5 cm in inner diameter) and divided into two layers (0–10 and 10–20 cm). Six soil cores were extracted randomly in each plot and mixed into one composite sample based on soil depth. Fine roots (0–20 cm) were hand-sorted from each composite soil sample and then cleaned with deionized water.

2.3. Chemical Analyses

All leaf and fine root samples were oven-dried at 65 °C to constant weight. Mineral soil from each plot was passed through a 2 mm mesh to remove fine roots and coarse fragments, and then the soil was air-dried at room temperature. After drying, the samples were ball-milled and analyzed for 15N natural abundance and total N and total carbon (C) concentrations using elemental analyzer–isotope ratio mass spectrometry (Elementar Analysen Systeme GmbH, Hanau, Germany; IsoPrime100, IsoPrime Ltd., Stockport, UK). Four reference compounds were calibrated: L-histidine, D-glutamic acid, glycine, and acetanilide. The analytical precision for both δ15N and δ13C was 0.2‰.

The soil samples were extracted with a 2 M KCl solution at a 1:4 soil-to-solution ratio. The KCl solution was pre-combusted at 450 °C for 48 h to eliminate background nitrate (NO3–) and ammonium (NH4+) contamination. Extractions were performed within 12 h after soil sampling. The extracts were shaken for 1 h, filtered, and frozen at −36 °C until analysis. The ammonium-N concentrations were determined colorimetrically using the indophenol blue method, while nitrate-N concentrations were measured via hydrazine reduction spectrophotometry (SmartChem200, Rome, Italy).

Soil pH was determined by placing 10 g of air-dried soil into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. A soil suspension was prepared at a soil-to-water ratio of 1:2.5 (dry weight basis) using CO2-free deionized water. The mixture was shaken on an orbital shaker for 10 min and then allowed to settle for 30 min. Subsequently, the pH of the supernatant was measured with a PHS-3E pH meter (INESA (Group) Co., Ltd. Shanghai China).

Soil bulk density was determined by collecting soil samples using a 100 cm3 soil core sampler (ring knife), followed by oven-drying and calculation based on dry soil mass and core volume.

2.4. Calculation of 15N Uptake and Biomass Metrics

The 15N atom% excess (APE) was calculated as the difference in atom% 15N between 15N-labeled plant organs and prior to 15N labeling samples (control). The 15N enrichment value was calculated using the following formula: [(sample abundance (δ15Nsample) − natural abundance of the control (δ15Nref))/(control abundance (δ15Nref) − 1000)] × 1000 [26].

The 15N uptake and assimilation rates (µg 15N g−1 dry mass d−1) were calculated by multiplying fine root and leaf N content (µg g−1 dry mass) by the corresponding (APE/100), and then dividing by the labeling time (in days) and the atom% 15N/100 of the applied 15N-labeled N form (99.14 atom% for 15NH4NO3 and 99.21 atom% for NH415NO3) [18]. The contribution percentage of each inorganic nitrogen source was calculated as follows: absorption rate of ammonium nitrogen or nitrate nitrogen/sum of absorption rates of two nitrogen sources × 100%.

Leaf biomass was estimated using species-specific allometric equations for H. brasiliensis, A. mangium, and P. caribaea [27,28,29], as shown below, where W represents the leaf biomass and D represents the diameter at breast height:

while fine root biomass within labeled areas was extrapolated from collected root samples.

WA. mangium = 0.0228 × D1.7535

WH. brasiliensis = 0.007 × D2.215

WP. caribaea = 0.332 × D0.855

2.5. Data Compilation

We identified 12 articles from the Web of Science reporting on the N uptake strategies of tropical tree species. The selected studies were categorized based on the key methodological consideration of whether they accounted for soil microbial competition, resulting in two main groups (including considering microbial competition result and no microbial competition results), each encompassing two prevalent experimental subtypes (including seedling nitrogen-15 (15N) labeling experiment; natural 15N abundance methods; seedling root 15N labeling and mature tree root 15N labeling). Studies were selected based on three criteria: (1) the experiment directly assessed plant N uptake (excluding long-term atmospheric deposition fate studies); (2) it was conducted in a (sub)tropical region; (3) the contribution of NO3− to total N uptake was reported or calculable. The NO3− contribution was standardized as: NO3− uptake/(NO3− uptake + NH4+ uptake). Details are in Supplementary Table S1.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

To test the hypothesis that nitrogen uptake strategies differ among species, one-way ANOVA followed by LSD post hoc tests and independent t-test were used to compare the three tree species across key response variables: soil physicochemical properties, plant traits, 15N abundance, and uptake/assimilation rates of 15NH4+ and 15NO3−. Effect sizes (Eta-squared, η2, for ANOVA; Cohen’s d for t-tests) were calculated to quantify the magnitude of observed differences beyond mere statistical significance. All analyses were performed at a significance level of p < 0.05 using SPSS 19.0 (version 19.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Soil and Stand Properties

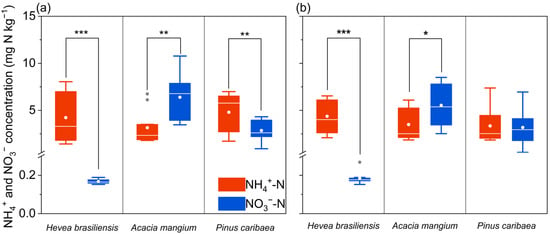

Soil ammonium and nitrate concentrations differed significantly among the three plantations. Ammonium is the dominant N form in H. brasiliensis and P. caribaea plantations, with concentrations ranging from 1.0 to 8.4 mg N kg−1 (Figure 1, η2 = 0.566, η2 = 0.247). By contrast, A. mangium plantations were nitrate-dominated, showing nitrate-N concentrations of 2.5–10.8 mg N kg−1 (Figure 1, η2 = 0.386).

Figure 1.

Concentrations of ammonium (NH4+) and nitrate (NO3−) in 0–20 cm mineral soil across the Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea forest plantations. (a) Soil N concentration in the 0–10 cm soil layer. (b) Soil N concentration in the 10–20 cm soil layer. In the box plot above, asterisks indicate significant differences between two nitrogen forms (one-way ANOVA *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; and ***, p < 0.001). Gray dots represent outliers, with the box showing the median (internal line), mean (white dot), interquartile range (box edges: Q1–Q3), and whiskers extending to the minimum and maximum values.

Soil C:N ratios were significantly higher in P. caribaea plantations than in the other two forest types (Table 1). All soils were consistently acidic, with pH values ranging from 4.5 to 4.8 and exhibiting significant differences among the plantations (Table 1). Leaf biomass of sampled trees ranged from 6.3 to 10.9 Mg ha−1, while fine root biomass per tree in the labeled area varied between 0.55 and 1.64 kg (Table 2). Significant differences in leaf N concentration and fine root C/N content were found among the three plantations (Table 2).

Table 1.

Soil physicochemical properties in the 0–20 cm mineral soil for the Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea forest plantations.

Table 2.

Plant traits in the Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea forest plantations.

3.2. The 15N Enrichment and 15N Uptake Rates

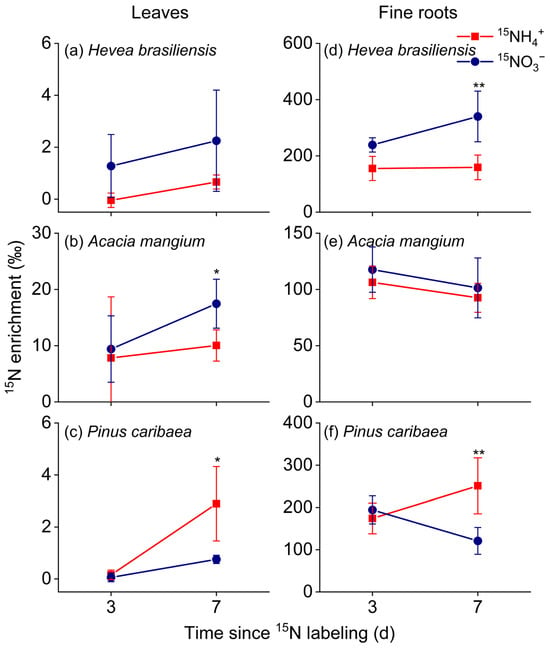

Before 15N labeling, fine root and leaf exhibited δ15N values of −0.4‰ to 9.1‰ and −2.4‰ to 3.7‰, respectively (Figure S3). After 15N labeling, a marked contrast in fine root 15N enrichment dynamics was observed: whereas H. brasiliensis and P. caribaea showed progressive enrichment peaking at day 7, A. mangium reached its maximum by day 3 and then declined slightly (Figure 2). In contrast, leaf δ15N continued to increase over the entire measurement period.

Figure 2.

The nitrogen-15 (15N) enrichment of leaves (a–c) and fine roots collected from 0 to 20 cm mineral soil (d–f) in the three studied forest plantations of (a,d) Hevea brasiliensis, (b,e) Acacia mangium, and (c,f) Pinus caribae (means ± SE, n = 5). The asterisks denote significant differences in the 15N enrichment between the two nitrogen forms on days 3 or 7 (independent samples t-test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

The three plantation species exhibited distinct responses to 15NO3− and 15NH4+ labeling in terms of 15N enrichment. In fine roots, H. brasiliensis showed significantly higher 15N enrichment under 15NO3− labeling than under 15NH4+ labeling on day 7 (Figure 2, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 2.57), whereas P. caribaea displayed the opposite pattern, with higher enrichment following 15NH4+ labeling on day 7. In leaves, the enrichment of 15NO3− was significantly higher than that of 15NH4+ in A. mangium on day 7 (p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 2.03), and a consistent nitrogen preference was observed in the other two species, mirroring the patterns observed in their fine roots.

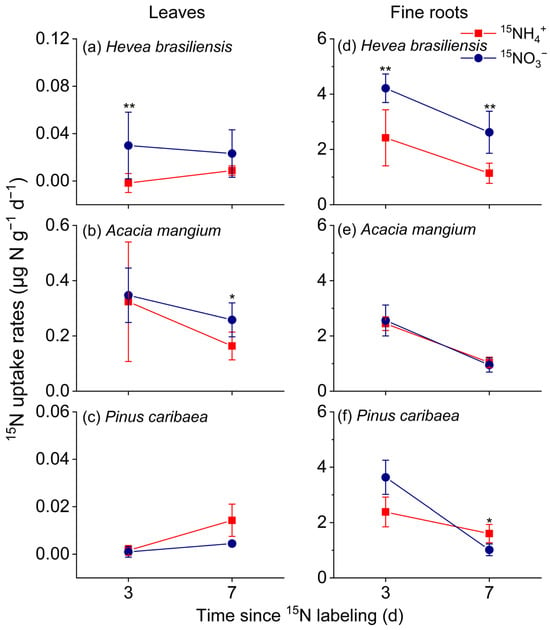

After 15N labeling, the three studied species exhibited clear organ-specific and species-specific patterns in nitrogen uptake dynamics. Fine root uptake peaked uniformly on day 3 before declining across all species (Figure 3), with rates ranging from 0.50 to 4.92 μg 15N g−1 d−1. Fine roots of H. brasiliensis showed a pronounced preference for 15NO3− (0.91–5.3 μg 15N g−1 d−1), significantly exceeding 15NH4+ uptake (Figure 3, p < 0.01, Cohen’s d = 2.24). A. mangium exhibited no statistically significant difference between nitrogen forms, though 15NO3− uptake (0.61–4.55 μg 15N g−1 d−1) was numerically higher than 15NH4+ uptake (0.53–3.03 μg 15N g−1 d−1). In contrast, P. caribaea fine roots demonstrated a marked dependence on 15NH4+ (0.76–3.56 μg 15N g−1 d−1), which became significantly greater than 15NO3− uptake by day 7 (p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 2.1).

Figure 3.

The nitrogen-15 (15N) uptake and assimilation rates of leaves (a–c) and fine roots collected from 0 to 20 cm mineral soil (d–f) in the three studied forest plantations of ((a,d) Hevea brasiliensis, (b,e) Acacia mangium, and (c,f) Pinus caribae (means ± SE, n = 5). The asterisks denote significant differences in the 15N uptake rates between the two nitrogen forms on days 3 or 7 (independent samples t-test; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

Leaf 15N uptake rates remained consistently lower than those in fine roots, ranging from −0.03 to 0.65 μg 15N g−1 d−1, and displayed a gradual increase over time. A. mangium exhibited the highest foliar uptake capacity, followed by H. brasiliensis, while P. caribaea showed the lowest rates (Figure 3). By day 7, clear species-specific nitrogen form preferences emerged: A. mangium leaves absorbed 15NO3− (0.08–0.45 μg 15N g−1 d−1) at rates higher than 15NH4+ (Figure 3); H. brasiliensis displayed similar uptake for both forms with marginally elevated 15NO3− assimilation; and P. caribaea demonstrated significantly greater 15NH4+ uptake (0.0003–0.018 μg 15N g−1 d−1) compared with 15NO3 (0.001–0.007 μg 15N g−1 d−1) (p < 0.05, Cohen’s d = 1.81).

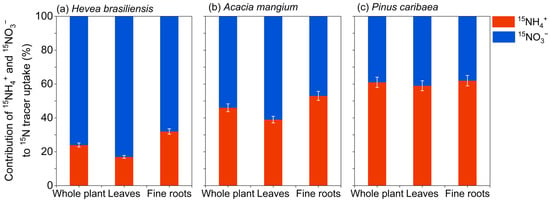

3.3. Contribution of Nitrogen Uptake

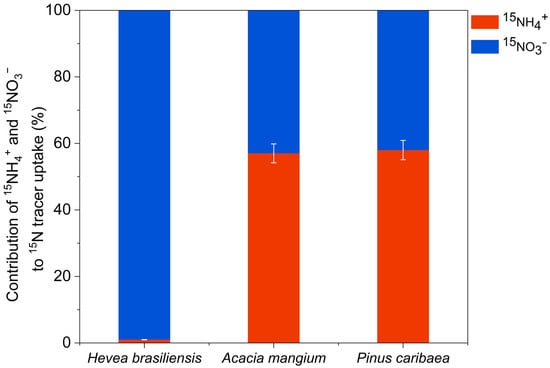

Since preliminary results showed that obvious 15N enrichment in leaves could not be detected on day 3, nitrogen contribution percentages were derived from 15N uptake rates measured at day 7. At the whole-plant level, H. brasiliensis exhibited a clear preference for nitrate, with 15NO3− accounting for 76% of total nitrogen uptake. In contrast, A. mangium showed comparable assimilation of both nitrogen forms, though with a slightly higher contribution from 15NO3− (53%), while P. caribaea demonstrated a marked dependence on ammonium, with 15NH4+ contributing 61% to total uptake (Figure 4). Additionally, even after accounting for the dilution effect of the soil inorganic N pool on the 15N-labeled sources, the proportional nitrate uptake by the three tree species remained between 42% and 99% (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Contribution of ammonium (15NH4+) and nitrate (15NO3−) to total nitrogen-15 (15N) tracer uptake and assimilation by different plant organs (fine roots and leaves) and whole-plant (N-pool-weighted mean) in the forest plantations of (a) Hevea brasiliensis, (b) Acacia mangium, and (c) Pinus caribaea at day 7 after 15N labeling (mean ± SE, n = 5).

Figure 5.

Contribution of 15NH4+ and 15NO3− to total N uptake by whole-tree (N-pool-weighted mean) in the Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea plantations by taking the dilution effect into account (mean ± SE, n = 5).

A similar nitrogen contribution pattern of nitrogen contribution at the whole-plant level was observed at the plant organ level. For fine roots, 15NO3− uptake substantially exceeded that of 15NH4+ in H. brasiliensis and A. mangium, contributing 68% and 47% of total root uptake, respectively. This contrasted sharply with P. caribaea, which showed a 59% contribution from 15NH4+ (Figure 4). For leaves, the nitrogen uptake mirrored the strategies observed in fine roots. Both H. brasiliensis and A. mangium maintained higher 15NO3− contributions (83% and 61%, respectively), whereas P. caribaea continued to rely predominantly on 15NH4+ (62% contribution) (Figure 4).

4. Discussion

4.1. Efficient Nitrate Uptake by Tropical Tree Species

Our in situ whole-tree paired 15N labeling experiment reveals clear interspecific divergence in N acquisition strategies among three species in tropical plantations. Contrary to the prevailing view that tropical tree species exhibit a predominant preference for ammonium [4], our results indicated that tropical tree species assimilated nitrate efficiently, with 15NO3− contributing 39% to 76% of total 15N tracer uptake (Figure 4). Even considering the dilution effect, all three tree species still demonstrated a capacity for nitrate absorption (Figure 5).

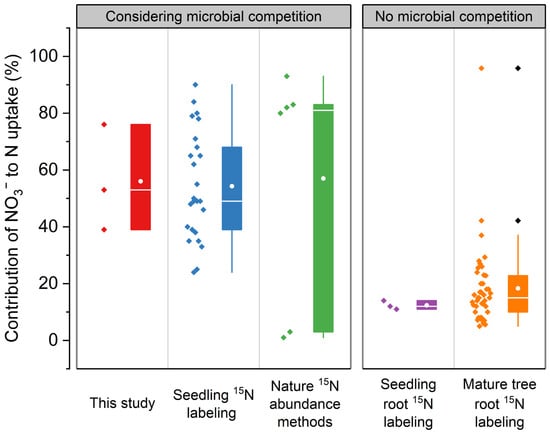

Specifically, H. brasiliensis and A. mangium exhibited a clear tendency toward nitrate uptake, accounting for 76% and 53% of their respective tracer uptake. This finding challenges conclusions derived primarily from hydroponic studies (Figure 6), which may overlook critical field complexities such as microbial competition for ammonium and soil N immobilization [19,20]. The observed nitrate preference may represent an ecological strategy to circumvent these competitions. Nitrate’s higher mobility enhances its diffusion to root surfaces in soil [30], thereby enhancing its plant availability [10,31]. Moreover, NO3− can be assimilated in both roots and leaves, offering metabolic flexibility. In contrast, NH4+ is prone to adsorption by soil organic matter [20] and must be assimilated rapidly in roots to avoid toxicity [32]. It is also preferentially consumed by soil microorganisms [20,33,34]. Thus, although nitrate assimilation is energetically more costly [35,36], it may represent a strategy to circumvent microbial competition [37].

Figure 6.

Comparative analysis of nitrogen contribution: present in situ vs. previous labeling experiments. The considering microbial competition results include this study (Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea), seedling nitrogen-15 (15N) labeling experiment [38,39,40,41,42], and natural 15N abundance methods [43]. The no microbial competition results include seedling root 15N labeling [44] and mature tree root 15N labeling [18,45,46,47,48].

Notably, P. caribaea derived 61% of the total N uptake from ammonium, indicating a distinct NH4+ preference. This contrasts with findings from in situ 15N labeling studies in temperate coniferous forests of northeastern China, where NO3− contributed 39%–90% to N acquisition in conifers [49]. Climatic influences may explain this discrepancy [4]. Compared with temperate regions, the tropical monsoon climate at our site, characterized by high temperature and humidity, likely accelerates N cycling and alters N bioavailability. Elevated temperatures can enhance the diffusion rate of NH4+ in soil [6], increasing its mobility and thus improving root accessibility. Concurrently, evidence suggests that shifts in precipitation regimes also modulate plant nitrogen uptake preference [18,43]. Under combined thermal and hydrological drivers, NH4+ in tropical forest soils may reach root surfaces more rapidly than in temperate systems, thereby facilitating plant acquisition. This mechanism offers a plausible explanation for the high 15NH4+-N uptake rates observed in the P. caribaea, underscoring the role of regional climate in shaping nitrogen uptake strategies.

4.2. Nitrogen Uptake Regulated by Mycorrhizal Types and Nitrogen-Fixing Capacity

Our results indicated significant interspecific differences in inorganic nitrogen acquisition strategies among the three tropical tree species. H. brasiliensis, commonly associated with AM fungi, exhibited a strong preference for NO3−, while A. mangium (an ECM-associated nitrogen-fixing species) also showed a tendency toward NO3− uptake, albeit to a lesser extent. In contrast, P. caribaea (commonly associated with ECM fungi) demonstrated a clear preference for NH4+. Although the present study did not experimentally quantify mycorrhizal colonization in the study trees, the observed nitrogen acquisition preferences align closely with the known mycorrhizal associations of these species in natural and cultivated settings, supporting the well-established framework of mycorrhizal-mediated niche differentiation in N nutrition [45].

Under field conditions, AM tree species often exhibit a preference for NO3− [11,12,13,47], which may be attributed to the enhanced nitrate uptake capacity mediated by AM fungal symbiosis. Genomic analyses indicate that AM fungi rarely assimilate organic nitrogen but primarily acquire inorganic nitrogen from soil [50,51]. Furthermore, their high nitrate reductase activity enables efficient assimilation of environmental nitrate [52], which may explain the generally high nitrate uptake observed in AM-associated trees. In contrast, ECM fungi can secrete extracellular hydrolytic enzymes [52], facilitating access to both organic and inorganic nitrogen sources. However, the expression of genes involved in nitrate assimilation is often suppressed in the presence of ammonium [53]. Cultivation experiments have confirmed that most ECM fungi grow more efficiently and exhibit higher nitrogen uptake rates with ammonium than with nitrate [54,55], suggesting a physiological bias toward ammonium utilization in ECM systems.

Consistent with our hypothesis, A. mangium, an ECM species with nitrogen-fixing capacity, displayed no strong preference for either nitrogen form. This flexibility likely stems from its reduced dependence on soil inorganic N due to symbiotic biological nitrogen fixation. This finding is consistent with a previous pot experiment showing that nitrogen-fixing tree species exhibit no specific preference for inorganic nitrogen forms [56]. The slight tendency toward NO3−-N observed in A. mangium may be attributed to the higher mobility of nitrate in soil [31]. Furthermore, A. mangium exhibited higher foliar nitrogen uptake rates than the other two species (Figure 3), which is consistent with the observation that nitrogen-fixing plants often exhibit elevated rates of inorganic nitrogen uptake [57,58]. This may be linked to the upregulation of nitrogen assimilation pathways by symbiotic rhizobia, which enhance the expression of key genes involved in nitrogen uptake and metabolism, such as ammonium transporters (AMTs), nitrate transporters (NRTs), nitrate reductase (NR), and glutamine synthetase (GS) [59,60]. In plant transport systems, AMTs and NRTs play central roles in regulating ammonium and nitrate uptake, respectively [61], while NR and GS are key enzymes in nitrate and ammonium assimilation [62,63].

5. Conclusions

This study employed an in situ 15N labeling technique to quantify NH4+-N and NO3−-N uptake preferences in three common tropical plantation species in southern China: H. brasiliensis (AM-associated), P. caribaea (ECM-associated), and A. mangium (ECM-associated and N-fixing). Our results demonstrate that the AM-associated species H. brasiliensis showed a tendency toward NO3−-N assimilation, while the ECM-associated species P. caribaea depended more heavily on NH4+-N. In contrast, A. mangium did not exhibit a strong preference for either nitrogen form but instead showed higher nitrogen uptake and greater metabolic flexibility. This supports our first hypothesis that both mycorrhizal type and nitrogen fixation capacity are important factors influencing plant nitrogen acquisition preferences. Notably, our results also challenge the conventional view that tropical trees predominantly favor ammonium. Contrary to our second hypothesis, all three species exhibited measurable NO3−-N uptake, with H. brasiliensis and A. mangium assimilating nitrate as a major nitrogen source. This suggests that mature tropical trees retain physiological adaptations for nitrate utilization, likely reflecting the rapid nitrogen cycling characteristic of warm, humid ecosystems. These mechanistic insights provide a scientific basis for refining nitrogen management in plantation forestry, including the strategic selection of tree species and mycorrhizal types to optimize nitrogen use efficiency and long-term productivity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16121866/s1. Figure S1: Locations of the study region and the Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea plantations in the Jianfengling National Natural Reserve on Hainan, Southern China; Figure S2: δ15N values of mineral soil at different depths (0–20 cm) for Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea plantationss; Figure S3: δ15N values in fine roots and leaves of Hevea brasiliensis, Acacia mangium, and Pinus caribaea; Notes S1: Data compilation and classified according to the experimental methods from literature; Table S1: Data collecting from 12 published papers, used in Figure 6.

Author Contributions

T.B., A.W., Y.F. and Y.L. planned and designed the research. T.B., A.W., T.Z. and D.C. performed experiments and conducted fieldwork. T.B., A.W., X.W., Y.Q., Y.T. and C.S. analyzed the data. T.B., A.W., X.W., Y.Q., F.Z., Y.T. and C.S. wrote the manuscript. T.B., A.W., Y.L. and Y.F. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD1500800), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA28020302), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271671, 42507318, and 32571856), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS to CW (2022194), the Natural Science Foundation of Liaoning Province (2023-MSLH-206), the Basic Research Project of the Educational Department of Liaoning Province (LJ212413201006), and the Liaoning Province Science and Technology Project (2022-JH2/101300128 and 2023012116-JH3/4500). Liaoning Provincial Science and Technology Plan Joint Program (Key Research and Development Program Project) (Grant No. 2023JH2/101800056).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The work was jointly supported by the Jianfengling National Key Field Station. We thank the many staff members for their assistance in sampling and analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

References

- Cheng, Y.; Luo, P.; Yang, H.; Li, M.W.; Ni, M.; Li, H.L.; Huang, Y.; Xie, W.W.; Wang, L.H. Land use and cover change accelerated China’s land carbon sinks limits soil carbon. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.P. China’s Forestry, 1999–2005; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.L.; Wang, D.X.; Zhao, H.; Yang, T. Discussion the status quality of plantation and near nature forestry management in China. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2008, 23, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.H.; Wang, J.S.; Liao, J.Q.; Xu, X.L.; Tian, D.S.; Zhang, R.Y.; Peng, J.L.; Niu, S.L. Plant nitrogen uptake preference and drivers in natural ecosystems at the global scale. New Phytol. 2025, 246, 972–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Percival, F.; Merino, J.; Mooney, H.A. Estimation of tissue construction cost from heat of combustion and organic nitrogen content. Plant Cell Environ. 1987, 10, 725–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courty, P.E.; Smith, P.; Koegel, S.; Redecker, D.; Wipf, D. Inorganic nitrogen uptake and transport in beneficial plant root-microbe interactions. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2015, 34, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, D.; Bardgett, R.D.; Finlay, R.D.; Jones, D.L.; Philippot, L. A plant perspective on nitrogen cycling in the rhizosphere. Funct. Ecol. 2019, 33, 540–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britto, D.T.; Kronzucker, H.J. Ecological significance and complexity of N-source preference in plants. Ann. Bot. 2013, 112, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, A.; Högberg, P.; Näsholm, T. Soil nitrogen form and plant nitrogen uptake along a boreal forest productivity gradient. Oecologia 2001, 129, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.X.; Macko, S.A. Constrained preferences in nitrogen uptake across plant species and environments. Plant Cell Environ. 2011, 34, 525–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcón, R.; Tobar, R.M. Activity of nitrate reductase and glutamine synthetase in shoot and root of mycorrhizal Allium cepa: Effect of drought stress. Plant Sci. 1998, 133, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcón, R.; Ruiz-Lozano, J.M.; Rodríguez, R. Differential contribution of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to plant nitrate uptake (15N) under increasing N supply to the soil. Can. J. Bot. 2001, 79, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, I.; Trappe, J.M. Nitrate reducing capacity of two vesiculararbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Mycologia 1975, 67, 886–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielland, K. Amino acid absorption by Arctic plants: Implications for plant nutrition and nitrogen cycling. Ecology 1994, 75, 2373–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D. The symbionts forming arbuscular mycorrhizas. In Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Smith, S.E., Read, D., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 13–41. [Google Scholar]

- Leberecht, M.; Dannenmann, M.; Tejedor, J.; Simon, J.; Rennenberg, H.; Polle, A. Segregation of nitrogen use between ammonium and nitrate of ectomycorrhizas and beech trees. Plant Cell Environ. 2016, 39, 2691–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Socci, A.M.; Templer, P.H. Temporal patterns of inorganic nitrogen uptake by mature sugar maple (Acer saccharum Marsh.) and red spruce (Picea rubens Sarg.) trees using two common approaches. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2011, 4, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Li, C.C.; Xu, X.L.; Wanek, W.; Jiang, N.; Wang, H.M.; Yang, X.D. Organic and inorganic nitrogen uptake by 21 dominant tree species in temperate and tropical forests. Tree Physiol. 2017, 37, 1515–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisseler, D.; Horwath, W.R.; Joergensen, R.G.; Ludwig, B. Pathways of nitrogen utilization by soil microorganisms—A review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 2058–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraterrigo, J.M.; Strickland, M.S.; Keiser, A.D.; Bradford, M.A. Nitrogen uptake and preference in a forest understory following invasion by an exotic grass. Oecologia 2011, 167, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.R.; Joly, C.A.; Smirnoff, N. Partitioning of inorganic nitrogen assimilation between the roots and shoots of cerrado and forest trees of contrasting plant communities of South East Brasil. Oecologia 1992, 91, 511–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalcsits, L.A.; Min, X.J.; Guy, R.D. Interspecific variation in leaf–root differences in δ15N among three tree species grown with either nitrate or ammonium. Trees 2015, 29, 1069–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.F.; Dai, L.M.; Hobbie, E.A.; Qu, Y.Y.; Huang, D.; Gurmesa, G.A.; Zhou, X.L.; Wang, A.; Li, Y.H.; Fang, Y.T. Quantifying nitrogen uptake and translocation for mature trees: An in situ whole-tree paired 15N labeling method. Tree Physiol. 2021, 41, 2109–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Wang, A.; Hobbie, E.A.; Zhu, F.F.; Wang, X.Y.; Li, Y.H.; Fang, Y.T. Nitrogen uptake strategies of mature conifers in Northeastern China, illustrated by the 15N natural abundance method. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrys, A.S.; Desoky, E.S.M.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, L.; Yun-Xing, W.; Wang, C.; Shuirong, T.; Yanzheng, W.; Meng, L.; Zhang, J. Climate controls on nitrate dynamics and gross nitrogen cycling response to nitrogen deposition in global forest soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 920, 171006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedrich, U.; Falk, K.; Bahlmann, E.; Marquardt, T.; Meyer, H.; Niemeyer, T.; Schemmel, S.; von Oheimb, G.; Härdtle, W. Fate of airborne nitrogen in heathland ecosystems: A 15N tracer study. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.P.; Cai, X.; Zhao, P.; Rao, X.Q.; Zou, B.; Zhou, L.X.; Lin, Y.B.; Fu, S.L. Biomass and net primary productivity of three plantations in the hilly region of South Subtropical China. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2008, 30, 148–152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.W.; Pang, J.P.; Chen, M.Y.; Guo, X.M.; Zeng, R. Biomass and its estimation model of rubber plantations in Xishuangbanna, Southwest China. Chin. J. Ecol. 2009, 28, 1942–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.C.; Du, H.; Song, T.; Peng, W.; Zeng, F.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, H. Allometric models of major tree species and forest biomass in Guangxi. ACTA Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 4462–4472. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.W.; Cheng, W.; Burke, I.C. Biotic and abiotic nitrogen retention in a variety of forest soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2000, 64, 1503–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epron, D.; Koutika, L.S.; Tchichelle, S.V.; Bouillet, J.P.; Mareschal, L. Uptake of soil mineral nitrogen by Acacia mangium and Eucalyptus urophylla x grandis: No difference in N form preference. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2016, 179, 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engels, C.; Marschner, H. Plant uptake and utilization of nitrogen. In Nitrogen Fertil. Environ.; Bacon, P.E., Ed.; Marcel Dekker Inc: New York, USA, 1995; pp. 41–81. [Google Scholar]

- Merrick, M.J.; Edwards, R.A. Nitrogen control in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 59, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzluf, G.A. Genetic regulation of nitrogen metabolism in the fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1997, 61, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Boudsocq, S.; Niboyet, A.; Lata, J.C.; Raynaud, X.; Loeuille, N.; Mathieu, J.; Blouin, M.; Abbadie, L.; Barot, S. Plant Preference for Ammonium versus Nitrate: A Neglected Determinant of Ecosystem Functioning? Am. Nat. 2012, 180, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huangfu, C.H.; Li, H.Y.; Chen, X.W.; Liu, H.M.; Wang, H.; Yang, D.L. Response of an invasive plant, Flaveria bidentis, to nitrogen addition: A test of form-preference uptake. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 3365–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Xu, X.L. Competition between roots and microorganisms for nitrogen: Mechanisms and ecological relevance. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, K.M.; Turner, B.L. Preferences or plasticity in nitrogen acquisition by understorey palms in a tropical montane forest. J. Ecol. 2013, 101, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.M.; Mayor, J.R.; Turner, B.L. Plasticity in nitrogen uptake among plant species with contrasting nutrient acquisition strategies in a tropical forest. Ecology 2017, 98, 1388–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, S.E.; Kochsiek, A.; Olney, J.; Thompson, L.; Miller, A.E.; Tan, S. Nitrogen uptake strategies of edaphically specialized Bornean tree species. Plant Ecol. 2013, 214, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, C.R. Uptake of inorganic and amino acid nitrogen from soil by Eucalyptus regnans and Eucalyptus pauciflora seedlings. Tree Physiol. 2009, 29, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Chen, C.; Yu, S. Uptake of organic nitrogen and preference for inorganic nitrogen by two Australian native Araucariaceae species. Plant Ecol. Divers. 2015, 8, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houlton, B.Z.; Sigman, D.M.; Schuur, E.A.G.; Hedin, L.O. A climate-driven switch in plant nitrogen acquisition within tropical forest communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 8902–8906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Stewart, G.R. Waterlogging and fire impacts on nitrogen availability and utilization in a subtropical wet heathland (wallum). Plant Cell Environ. 1997, 20, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.C.; Li, Q.; Qiao, N.; Xu, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, H. Inorganic and organic nitrogen uptake by nine dominant subtropical tree species. Iforest-Biogeosci. For. 2016, 9, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Y.; Wang, H.M.; Xu, X.L. Root nitrogen acquisition strategy of trees and understory species in a subtropical pine plantation in southern China. Eur. J. For. Res. 2020, 139, 791–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xu, F.Z.; Xu, X.L.; Wanek, W.; Yang, X.D. Age alters uptake pattern of organic and inorganic nitrogen by rubber trees. Tree Physiol. 2018, 38, 1685–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Xu, X.; Jin, P.; Bruelheide, H.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Bardgett, R.D.; Wanek, W. Advancing predictive understanding of tree organic and inorganic nitrogen uptake across forest biomes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2026, 213, 110027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.L.; Wang, A.; Hobbie, E.A.; Zhu, F.F.; Qu, Y.Y.; Dai, L.M.; Li, D.J.; Liu, X.Y.; Zhu, W.X.; Koba, K.; et al. Mature conifers assimilate nitrate as efficiently as ammonium from soils in four forest plantations. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 3184–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, D.J.; Perez-Moreno, J. Mycorrhizas and nutrient cycling in ecosystems—A journey towards relevance? New Phytol. 2003, 157, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, C.J.; Kasiborski, B.; Koul, R.; Lammers, P.J.; Bücking, H.; Shachar-Hill, Y. Regulation of the nitrogen transfer pathway in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis: Gene characterization and the coordination of expression with nitrogen flux. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 1175–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makarov, M.I. The role of mycorrhiza in transformation of nitrogen compounds in soil and nitrogen nutrition of plants: A review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2019, 52, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, R. Nitrogen acquisition in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis. In Molecular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Martin, F., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay, R.D.; Frostegard, Å.; Sonnerfeldt, A.-M. Utilization of organic and inorganic nitrogen sources by ectomycorrhizal fungi in pure culture and in symbiosis with Pinus contorta Dougl. ex Loud. New Phytol. 1992, 120, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallander, H.; Massicotte, H.B.; Nylund, J.E. Seasonal variation in protein, ergosterol and chitin in five morphotypes of Pinus sylvestris L. ectomycorrhizae in a mature Swedish forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1997, 29, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Dumroese, R.K.; Pinto, J.R. Organic or inorganic nitrogen and rhizobia inoculation provide synergistic growth response of a leguminous forb and tree. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellstedt, A. Nitrogen and carbon utilization in Alnus incana fixing N2 or supplied with NO3− at the same rate. J. Exp. Bot. 1986, 37, 786–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellstedt, A.; Huss-Danell, K. Biomass production and nitrogen utilization by Alnus incana when grown on N2 or NH4+ made available at the same rate. Planta 1986, 167, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, T.L.G.; Balsemão-Pires, E.; Saraiva, R.M.; Ferreira, P.C.G.; Hemerly, A.S. Nitrogen signalling in plant interactions with associative and endophytic diazotrophic bacteria. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5631–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.B.; Li, Y.L.; Zhang, H.W.; Wang, M.Y.; Chen, S.Y. Diazotrophic BJ-18 provides nitrogen for plant and promotes plant growth, nitrogen uptake and metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Rodríguez, V.; Cañas, R.A.; de la Torre, F.N.; Pascual, M.B.; Avila, C.; Cánovas, F.M. Molecular fundamentals of nitrogen uptake and transport in trees. J. Exp. Bot. 2017, 68, 2489–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beevers, L.; Hageman, R.H. Nitrate reduction in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 1969, 20, 495–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Lali, M.N.; Xiong, H.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Lu, M.; Wang, J.; He, X.; Shi, X.; et al. Seedlings of Poncirus trifoliata exhibit tissue-specific detoxification in response to NH4+ toxicity. Plant Biol. 2024, 26, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).