Abstract

Climate change significantly impacts the survival and distribution of alpine vegetation on the Tibetan Plateau. Endangered Rhodiola species, represented by Rhodiola crenulata (Hook. f. & Thomson) H. Ohba and Rhodiola tangutica (Maxim.) S.H. Fu. are highly sensitive to climate change. Modeling their adaptive distribution and identifying ecological corridors are crucial for developing conservation strategies. Using the biomod2 platform and the MCR model, this study projects the potential geographical distribution of the two Rhodiola species under current and future climate scenarios and further identifies key ecological corridors. The results indicate that under current climate conditions, Rhodiola crenulata is mainly distributed in the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau, while Rhodiola tangutica is primarily concentrated in the northeastern region. Temperature, precipitation, and elevation are identified as key environmental drivers influencing their distribution. Under future climate scenarios, the total adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata is projected to expand. The most significant expansion, reaching 22%, is projected under the SSP585 scenario in the 2090s. In contrast, the total adaptive area of Rhodiola tangutica is expected to contract, with a reduction of 2.99% under the SSP585 scenario in the 2070s. Based on the migration trends of the two species, ecological corridors suitable for development, such as primary corridors and secondary corridors, were established to support species migration and biodiversity conservation. By integrating species distribution models with the MCR model, this study provides a scientific basis for the conservation of endangered Rhodiola species under climate change.

1. Introduction

Climate change is a key driver reshaping global species distribution patterns, exerting profound impacts on the geographical ranges of species at an unprecedented rate and scale. Global warming not only directly leads to rising temperatures but also alters precipitation regimes, increases the frequency and intensity of droughts, and triggers more frequent extreme climate events [1]. In recent years, extreme phenomena such as heatwaves, heavy rainfall, and persistent droughts have become increasingly prominent worldwide, particularly in mid-to-high latitude regions [2]. As regional temperatures continue to rise, changes in species biomass and community structure occur, leading to succession within certain areas and thereby altering species growth and distribution [3,4,5]. More critically, climate change can also lead to the fragmentation of suitable habitats, not only posing a threat to biodiversity [6,7], but also affecting species’ survival, reproduction, and spatial distribution patterns [8,9]. These changes further exacerbate ecosystem vulnerability, forcing many species to migrate towards higher latitudes and altitudes in response to the rapidly changing climate [10,11,12]. Therefore, studying the impact of climate change on species’ adaptive distribution areas not only helps elucidate the ecological mechanisms of species responses to climate change but also provides a crucial scientific basis for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem management. This field has now become a hotspot in ecological research and has garnered widespread attention from scholars.

The Tibetan Plateau, known as the “Roof of the World,” the “Water Tower of Asia,” and the “Third Pole,” is globally recognized as a climate-sensitive region [13,14]. In recent years, the impacts of global warming have been particularly pronounced in this area, posing severe threats to the plateau’s ecosystems and biodiversity. In response to rising temperatures, some species are forced to migrate to higher elevations or latitudes [15], significantly altering original habitat patterns and resulting in the contraction and fragmentation of adaptive habitats. This poses particular stress to rare species with limited dispersal capabilities, such as Androsace tapete Maxim. [16] and Rheum nobile Hook. f. & Thomson [17], whose suitable habitats continue to diminish. Concurrently, global warming accelerates glacier retreat and permafrost degradation, leading to the functional decline of alpine wetland and meadow ecosystems that depend on snowmelt, thereby worsening the living conditions for species such as Saussurea medusa Maxim. [18] and Meconopsis spp. Vig. [19], increasing their risk of extinction. Furthermore, the increased frequency of extreme climate events causes reproductive failure or direct mortality in species adapted to stable cold environments. Such abrupt climatic disturbances further weaken population resilience and accelerate biodiversity loss. Under climatic stress, the biodiversity of the Tibetan Plateau is facing unprecedented challenges, necessitating systematic research and conservation interventions.

Plants of the Crassulaceae family are perennial herbs, with over 1500 species distributed globally and more than 200 species found in China [20]. Characterized by their short stature, succulent leaves with sunken stomata, water storage capacity, and waxy coatings, Crassulaceae species exhibit strong drought resistance and can thrive in harsh environments [21,22]. In China, the earliest emergence of Rhodiola species can be traced back to the Tibetan Plateau, where their origin is closely linked to the region’s geological evolution [23]. As the Tibetan Plateau gradually uplifted, plants originally inhabiting low-altitude areas, including Rhodiola L., began migrating to higher elevations [24,25]. Through adaptation to extreme conditions such as low temperatures, hypoxia, intense ultraviolet radiation, and drought, Rhodiola gradually evolved to survive in these environments [26]. However, in recent years, global climate change has led to continuous temperature increases, altered precipitation patterns, and more frequent extreme climate events on the Tibetan Plateau. These changes have led to habitat degradation and fragmentation for Rhodiola species, resulting in ongoing population declines and pushing some species to the brink of extinction [27]. Under this context, this study focuses on two endangered Crassulaceae species predominantly distributed on the Tibetan Plateau: Rhodiola crenulata (Hook. f. & Thomson) H. Ohba and Rhodiola tangutica (Maxim.) S.H. Fu. Methodologically, we integrate multiple species distribution models with the Minimum Cumulative Resistance (MCR) model to systematically simulate changes in the adaptive distribution of these two Rhodiola species under current and future climate conditions. Based on these projections, we construct ecological corridors suitable for migration, including primary corridors and secondary corridors. This approach provides a spatial basis for alleviating habitat fragmentation and facilitating natural species migration, while also offering a scientific reference for biodiversity conservation and adaptive management in alpine regions.

Species Distribution Models (SDMs) are important tools in ecology and biogeography research [28]. These mathematical models use statistical methods to estimate species’ ecological requirements based on relationships between environmental variables and species distribution data [29,30], thereby predicting potential species distribution ranges across different regions and assessing the contributions of environmental variables [31,32]. This study employs the R-based Biomod2 platform for ensemble modeling [33], By integrating multiple algorithms and utilizing weighted averages or consensus mechanisms, this platform effectively enhances prediction accuracy and stability [34], making it one of the most mature multi-model platforms available [35]. Previous studies have used ensemble models to investigate the potential distribution of coniferous plants [36], and endangered species [37] in China. To address habitat fragmentation and enhance connectivity among populations, the establishment of ecological corridors has become a critical strategy for biodiversity conservation. The MCR model is widely used to simulate potential pathways for species during spatial migration, thereby identifying the locations of key ecological corridors. The integration of ensemble modeling with the MCR model enables not only the prediction of suitable habitats for the two endangered Rhodiola species but also the further construction of ecological corridors to facilitate gene flow and population dispersal. This integrated approach provides a spatial planning basis for their conservation and restoration.

Based on species occurrence data and environmental variables of Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica on the Tibetan Plateau, an ensemble model is developed using the Biomod2 platform to predict the impact of future climate change on the potential adaptive distribution of these two Rhodiola species. The objectives of this study are: (1) to simulate the adaptive distribution of the two endangered Rhodiola species under current climatic conditions and identify the key environmental factors influencing their distribution using the ensemble model; (2) to predict and analyze dynamic changes in the adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica under future climate change scenarios; (3) to calculate the minimum cumulative resistance of ecological source areas using the MCR model, establish key ecological corridors, and identify optimal dispersal pathways. This study provides a scientific theoretical basis for the ecological restoration of habitats for the endangered alpine plant Rhodiola on the Tibetan Plateau under the influence of climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Screening and Processing

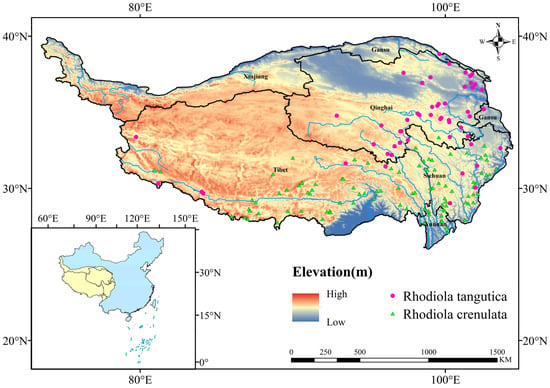

Geographic distribution data for two Rhodiola Species on the Tibetan Plateau were primarily sourced from open-access databases: the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF: https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.7enrd7 (accessed on 22 October 2024)) and the Chinese Virtual Herbarium (CVH: https://www.cvh.ac.cn (accessed on 5 June 2023)). The initial dataset underwent a cleaning process to remove duplicate and invalid records, followed by the extraction of latitude and longitude coordinates from the geographical locations. To mitigate overfitting caused by spatial clustering of samples, a 5 km × 5 km grid buffer was established using the SDMtoolbox in ArcGIS 10.8.1, retaining only one unique occurrence record per grid cell. Ultimately, a total of 159 distribution points were collected for the two Rhodiola species (Figure 1). The boundary data of the Tibetan Plateau were obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Science Data Centre. Provincial boundary data were sourced from the Centre for Resource and Environmental Science and Data of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. All spatial data were resampled to a uniform resolution of 1 km.

Figure 1.

Distribution of two Rhodiola species on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau.

Contemporary climate data used in this study were obtained from WorldClim (https://worldclim.org/ (accessed on 16 October 2024)) at a spatial resolution of 1 km and included 19 bioclimatic variables. Elevation factors were obtained from WorldClim (https://worldclim.org/ (accessed on 20 October 2024)) at a spatial resolution of 1 km, and slope and aspect data were extracted using the surface analysis tool of ArcGIS 10.8.1. Soil data were obtained from the World Soil Database HWSD 2.0, (https://gaez.fao.org/pages/hwsd (accessed on 22 October 2024)). The spatial resolution was 1 km. Land use data and NDVI data for China were obtained from the Centre for Resource and Environmental Science and Data of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://www.resdc.cn, (accessed on 26 May 2025)), with a spatial resolution of 1 km.

Future climate data were obtained from WorldClim (https://worldclim.org/, (accessed on 16 October 2024)) at a spatial resolution of 1 km, which includes 19 bioclimatic variables. Future climate scenarios were based on data from the BCC-CSM2-MR climate model of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6), as released in the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The data were statistically downscaled and bias-corrected using the delta method and considered three Shared Socioeconomic Pathways SSP126 (low carbon emissions), SSP370 (medium carbon emissions), and SSP585 (high carbon emissions). Using the current period (1970–2000) as the baseline, environmental variables for three future projection periods—2041–2060, 2061–2080, and 2081–2100—were selected. Since changes in topography and soil are expected to be minimal under climate change, this study assumed no alterations in terrain or soil conditions within the study area during the projection periods.

Given the large number of bioclimatic factors, and to reduce multicollinearity among environmental variables that could lead to model overfitting, 32 environmental variables from the current period and the filtered species occurrence data were imported into ArcGIS 10.8. The corresponding environmental values were then extracted at each species occurrence point. The extracted data were divided into climatic and non-climatic variables, and Pearson correlation analysis was performed using R4.3.3 to avoid overfitting caused by high correlations among environmental predictors. Finally, environmental variables with a correlation coefficient of less than 0.8 and greater biological relevance were retained for subsequent modeling [38] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Environmental factors involved in species modeling.

2.2. Identification of Driving Factors, Adaptive Distribution, and Centroid Shift

During the modeling process, this study utilized the Biomod2 platform within R to incorporate the two Rhodiola species distributed across the Tibetan Plateau into the model. We selected and evaluated 11 single-species distribution models available in Biomod2, including GAM, GBM, GLM, RF, MaxEnt, CTA, FDA, MARS, SRE, XGBOOST, and ANN. Customized parameters were set for each model within the Biomod2 platform to optimize algorithmic performance and avoid overfitting (Table S1). As these models require both presence and absence data, two sets of pseudo-absence points (1000 points each) were randomly generated. Modeling of the potential adaptive distribution for Rhodiola was performed with five replicates for each algorithm. A 5-fold cross-validation was applied, with 75% of species occurrence records used as training data and 25% as validation data [39,40]. Based on the model evaluation results, the top-performing individual models were selected and integrated using a weighted average algorithm to create an ensemble model (EM).

The performance of the 11 models was evaluated using the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the True Skill Statistic (TSS). The AUC is one of the most effective metrics in Species Distribution Modeling (SDM), as it is independent of specific diagnostic thresholds and shows low sensitivity to changes in species prevalence, ensuring objectivity and accuracy. AUC values range from 0.5 to 1, with values closer to 1 indicating better predictive performance. TSS not only inherits the advantage of Kappa in accounting for random agreement but also overcomes Kappa’s limitations in dealing with unimodal responses to species prevalence. TSS values closer to 1 indicate superior predictive accuracy [41]. All models with AUC > 0.8 and TSS > 0.7 were selected to construct the EM, which was subsequently used to predict the adaptive habitats for the two Rhodiola species. For the individual models used in the modeling, the standard deviations of AUC and TSS values from cross-validation were calculated to assess the stability of model evaluation (Table S2).

The selected environmental variables were input into the EM to calculate their contribution rates. The results were exported to a CSV file, and the variables were ranked based on their contributions. The variable with the highest contribution was identified as the most important influencing factor. Using these data, we qualitatively analyzed the impact of environmental variables on the distribution of the two Rhodiola species and plotted response curves for the most significant factors. Generally, in the resulting response curves, the range of a variable where the probability of survival exceeds 0.5 is considered the most favorable for the species’ persistence in the community.

Based on the adaptive habitat distributions of Rhodiola species across different periods, we classified the study area into four categories using the Jenks natural breakpoint classification method: not adaptive (0–0.3), minimally adaptive (0.3–0.5), moderately adaptive (0.5–0.7), and highly adaptive (0.7–1). A presence/absence (1/0) binary matrix was generated for current and future climate scenarios using the threshold that maximizes the True Skill Statistic (MaxTSS). Comparative calculations of habitat area changes were performed between time periods, where matrix transitions 0 to 1 represented habitat expansion, 1 to 0 indicated habitat contraction, and 1 to 1 denoted unchanged habitat [42]. These matrix values were subsequently converted into spatial attributes and imported into ArcGIS 10.8.1 to generate change distribution maps depicting spatiotemporal dynamics of adaptive habitats. Finally, the centroid of adaptive habitats was derived using the SDM toolbox in ArcGIS 10.8.1. The directional shift of the centroid under future climate scenarios was calculated based on its movement trajectory.

2.3. MCR Modeling for Corridor Identification

Based on the MCR model, this study constructed ecological corridors to facilitate the migration and dispersal of the two endangered Rhodiola species [43,44]. The MCR model identifies optimal pathways by calculating the least-cost route across an ecological resistance surface, simulating the migration process from a source to a target location. Pathways with lower cumulative resistance are more conducive to efficient ecological flows.

Adaptive habitats for the two Rhodiola species, identified using the biomod2 model, served as the basis for data selection and integration. Six habitat patches with the highest dPC (probability of connectivity) values were selected as ecological sources using Conefor software. The dPC index, which measures patch importance, effectively evaluates the connectivity level between core patches within a region [45]. Furthermore, four environmental factors—elevation, slope, land use type, and normalized difference vegetation Index—were selected to construct the ecological resistance surface influencing species dispersal. Based on the ecological habits of Rhodiola species and expert judgment, the raster data of the ecological resistance surface were reclassified and assigned values from 1 to 6 (Table 2) using ArcGIS 10.8.1, with higher values representing greater ecological landscape resistance [46]. The analytical software yaahp was used to evaluate the resistance values among these factors and calculate the weight of each resistance factor. The weight for each factor was calculated as 0.25, and the resulting consistency ratio (CR < 0.1) confirmed the validity of the comparative judgments. Based on the gravity model, an interaction matrix among the six ecological sources was calculated. The interaction strengths derived from this matrix were used to identify primary corridors and secondary corridors.

Table 2.

Categorization and Weighting of Resistance Factors.

3. Results

3.1. Adaptive Distribution and Environmental Driving Factors

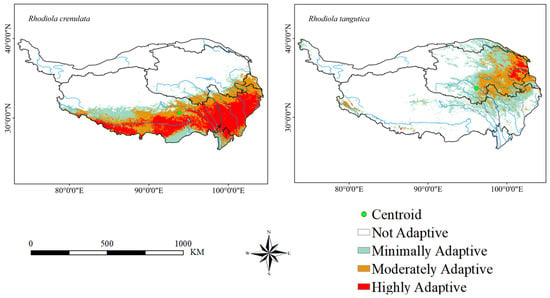

The results based on the EM indicate that under current conditions, the adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata is mainly distributed in the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau, with its primary concentration in Yunnan, Sichuan, and southern Tibet. Additionally, a small portion of the adaptive area is found in Gansu and Qinghai. The centroid of the adaptive area is located in southern Tibet. The highly adaptive area of Rhodiola tangutica is mainly distributed in the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau, primarily concentrated in Qinghai Province, with smaller distributions in Tibet, Gansu, and Sichuan. The centroid of its adaptive area lies within Qinghai Province. The adaptive areas of the two species partially overlap. The adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata accounts for 33% of the total area of the Tibetan Plateau, of which the highly adaptive area accounts for 16%. The adaptive area of Rhodiola tangutica accounts for 26.5% of the total area of the Tibetan Plateau, of which the highly adaptive area accounts for 1.35% (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of adaptations of two Rhodiola species under current climatic conditions.

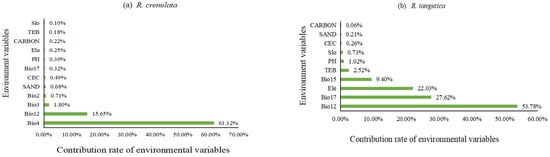

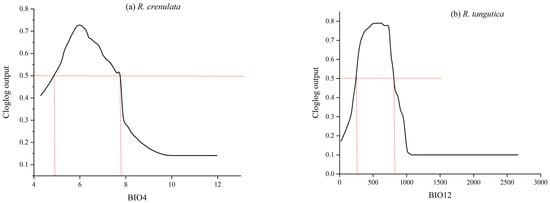

The dominant factors influencing the spatial distribution of the adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata are primarily climatic variables, specifically BIO4 (61.12%) and BIO12 (15.65%), which have a substantial impact on its distribution. In contrast, soil and topographic factors have relatively minor influences. For Rhodiola tangutica, the dominant factors are BIO12 (53.78%) and BIO7 (27.62%), which greatly affect its spatial distribution, while the topographic factor ELEV (22.03%) also has a certain degree of influence (Figure 3). Response curves were plotted for the most critical environmental factors of the two Rhodiola species. For Rhodiola crenulata, suitable survival conditions occur when BIO4 is within the range of 5–7 °C. Similarly, for Rhodiola tangutica, the suitable range for the key factor BIO12 is 260–800 mm (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

(a) Contribution Rates of Environmental Variables for Rhodiola crenulate; (b) Contribution Rates of Environmental Variables for Rhodiola tangutica.

Figure 4.

(a) Response curves of the most important factors for Rhodiola crenulate; (b) Response curves of the most important factors for Rhodiola tangutica.

3.2. Climate Change-Driven Shifts in Adaptive Distribution and Centroid Migration

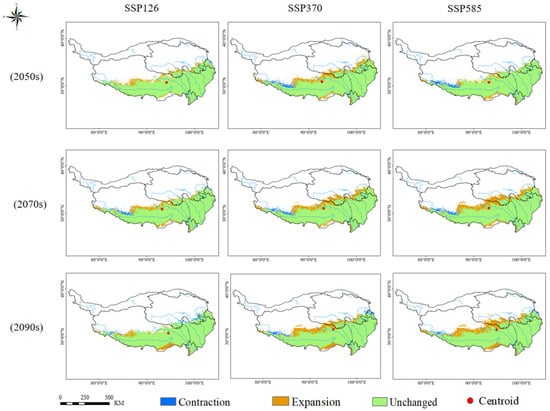

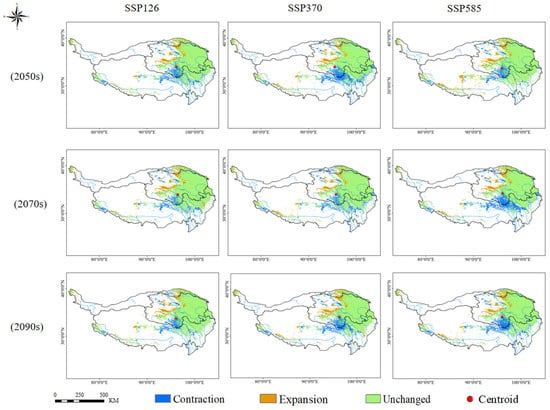

Under future climate scenarios (2050s, 2070s, 2090s; SSP126, SSP370, SSP585), the adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata expanded both northward and southward, with expansion being more pronounced in the north. Under the SSP126 scenario across different periods, the expansion of the adaptive area was the smallest and relatively stable. By the 2090s, the highly adaptive area showed contraction, but the moderately adaptive area expanded considerably, resulting in a net increase of 5.66% in the total adaptive area. Under the SSP370 scenario, the centroid of Rhodiola crenulata shifted northwest by the 2050s and continued northward in the 2070s and 2090s. The adaptive area expanded both north and south, with a particular marked increase in northern high-latitude regions. With rising CO2 concentrations under the SSP585 scenario, the highly adaptive area reached its maximum extent by the 2070s, accounting for 28.41% of the total area. By the 2090s, the adaptive area showed the greatest increase, expanding northward by 22%, with the total adaptive area reaching 40.56% of the plateau (Figure 5, Figures S1 and S3 and Table S3).

Figure 5.

Changes in the Adaptive Area of Rhodiola crenulata under Future Climate Scenarios.

For Rhodiola tangutica under future scenarios, the adaptive area remained relatively stable and changed little compared to current conditions under the low-emission SSP126 scenario. However, by the 2050s, the highly adaptive area was minimal, constituting only 0.47% of the total adaptive area. Under the medium-emission SSP370 scenario, the centroid shifted northwest in the 2050s, then eastward in the 2070s, and northeast by the 2090s, while the adaptive area continuously contracted from the south. Under the SSP585 scenario, a slight northern expansion (≤1%) occurred in the 2050s, but contraction was observed under other scenarios and periods. The most significant contraction occurred in the 2070s, with a 2.99% reduction in the south, bringing the total adaptive area to 23.93% of the plateau (Figure 6, Figures S2 and S3 and Table S4).

Figure 6.

Changes in the Adaptive Area of Rhodiola tangutica under Future Climate Scenarios.

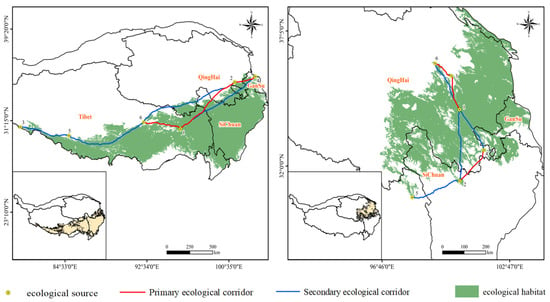

3.3. Corridor Identification of Endangered Rhodiola Plants

In this study, the ecological sources of Rhodiola crenulata are located in the southern part of the Tibetan Plateau in China. A total of six ecological source points were identified, including four within Tibet, and one each in Qinghai and Gansu. Based on the MCR model, 15 ecological corridors were identified, comprising three primary corridors and four secondary corridors. Among them, the longest primary corridor spans Tibet, Sichuan, and Gansu, crossing the Bayankala Mountain and Kunlun Mountain with an average elevation exceeding 4000 m, extending from Lhorong County in Tibet to Henan Mongol Autonomous County in Qinghai, with a total length of 1398.001 km. The shortest primary corridor, without obstruction from mountains or rivers, stretches from Henan Mongol Autonomous County in Qinghai to Hezuo City in Gansu, with a total length of 378.770 km. Among the secondary corridors, three continuous ecological corridors extend from Zali County in the westernmost part of the Tibetan Plateau to Henan Mongol Autonomous County within Qinghai Province, with a total length of 4522.935 km (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Ecological corridor identification in Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica.

The ecological sources of Rhodiola tangutica are located in the eastern part of the Tibetan Plateau in China. Six ecological source points were identified, with four predominantly concentrated within Qinghai Province, and the remaining two distributed in Sichuan and Tibet. Among them, two primary ecological corridors are situated within Qinghai. These corridors are not separated by mountains, with the shortest ecological corridor spanning 167.702 km, connecting Gonghe County and Wulan County within Qinghai Province. The other primary corridor crosses the Dadu River, connecting Sichuan Province and Qinghai Province, and is the longest primary ecological corridor, extending from Sertar County in Sichuan to Jiuzhi County in Qinghai, with a total length of 362.7161 km. Additionally, there are four secondary corridors connecting Qinghai with Tibet and Gansu, overcoming the isolation of species by the Bayan Har Mountains and Kunlun Mountains.

4. Discussion

Species distribution models are important tools for studying potential species distributions. However, traditional single-model approaches (e.g., MaxEnt) may suffer from issues such as insufficient accuracy or overfitting due to their reliance on limited occurrence data and susceptibility to the complex topography of the Tibetan Plateau [47,48,49]. This study employed the ensemble modeling platform Biomod2, which integrates multiple single-species models to construct an EM, significantly improving prediction accuracy and stability compared to individual models. The results show that although single models performed well in terms of AUC values (>0.8), other metrics like TSS and KAPPA exhibited considerable fluctuation (0.6–0.9). In contrast, all evaluation metrics for the EM remained consistently above 0.8, indicating significantly superior predictive performance compared to any single model [50]. The EM for Rhodiola crenulata achieved an AUC of 0.937 and a TSS of 0.831, while that for Rhodiola tangutica achieved an AUC of 0.928 and a TSS of 0.849. The predictive accuracy for both species is substantial, enabling reliable projection of their adaptive habitats.

For alpine sparse vegetation growing on the Tibetan Plateau, environmental factors such as temperature, precipitation, and elevation play crucial roles in influencing potential geographical distribution and growth [51,52]. Some studies have found that temperature and precipitation significantly affect alpine vegetation [53], a conclusion consistent with our findings. Our results indicate that BIO4 is the primary driver for Rhodiola crenulata. Distributed in the southern Tibetan Plateau and influenced by the Indian Ocean monsoon, this area experiences considerable intra-seasonal temperature variability. Temperature significantly affects the survival limits of Rhodiola crenulata by regulating its phenological cycle and cold resistance adaptability. Specifically, shifts in the timing of key phenological events (e.g., flowering onset) driven by temperature variability could disrupt synchronization with pollinators, thereby affecting reproductive success and ultimately population viability in marginal habitats [54,55]. In contrast, Rhodiola tangutica, located in the eastern Tibetan Plateau, is mainly driven by BIO7, which modulates its cold resistance through annual temperature variation. Furthermore, studies have shown that precipitation is the dominant factor controlling vegetation growth in the arid and semi-arid regions of the southwestern and northeastern Tibetan Plateau [56]. This study found that annual precipitation (BIO12) is an environmental factor constraining the distribution of both Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica. Rhodiola crenulata utilizes a snowmelt recharge pattern, forming a synergistic water retention mechanism with sandy soil at high altitudes [57]. Rhodiola tangutica relies on moisture availability during the spring snowmelt period, which affects its water-use efficiency. The synergistic effect of precipitation and temperature, through their combined hydrothermal influence, collectively defines the survival boundaries of these species.

Climate is the primary factor determining vegetation types and their distribution on Earth, while vegetation represents the most distinct reflection and indicator of Earth’s climate. The interaction between vegetation and climate constitutes a complex system, with vegetation responding to climatic changes through migration. Researchers have found that alpine vegetation on the Tibetan Plateau tends to migrate toward higher latitudes under climatic influence, which may be related to the horizontal patterns of climate change [58,59]. These findings align with our results. Our study demonstrates that under future climate scenarios, the adaptive areas of both Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica shift toward higher latitudes on the Tibetan Plateau. This phenomenon is mainly attributed to the positive effects of specific drivers of future climate change on the ecological requirements of these Rhodiola species. The adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata, located in the Himalayan region, is particularly narrow, and its northward migration to higher latitudes enables it to seek more adaptive survival zones. This latitudinal shift, however, is not merely a spatial translation of suitable climate space. It represents a critical ecological response to alleviate thermal stress and align phenology with the new local climate regime, a process essential for long-term population persistence [60]. For Rhodiola tangutica in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau, rising temperatures accelerate the succession of alpine meadows to shrublands, allowing more competitive plants to invade and further compress its already limited habitat [61], Consequently, its adaptive area continues to shrink, driving persistent migration to higher latitudes in search of adaptive living conditions. This habitat compression and forced migration highlight the profound impact of climate change-induced biotic interactions and habitat fragmentation pressures [62]. Other scholars have noted that under significant global warming, migration to higher latitudes can alleviate thermal stress in alpine plants by maintaining temperature variations within adaptive ranges for plant survival [63]. These findings are consistent with our results.

Different species exhibit varying adaptive capacities to environmental changes, demonstrating distinct migration patterns. Even within similar geographical regions, closely related species may evolve different environmental adaptation strategies [64]. Diversified ecological environments are more conducive to the survival of endangered species. The construction of ecological corridors facilitates biological migration and flow, improves ecosystem services, and better maintains ecological balance. Against the backdrop of climate change, ecological corridors can rebuild landscape connectivity by linking isolated habitat patches, providing fundamental pathways for species migration, gene exchange, and population re-establishment. They are crucial for addressing habitat fragmentation, maintaining biodiversity, and enhancing ecosystem resilience. For the endangered Rhodiola species, identifying and establishing ecological corridors enables more effective, site-specific conservation.

It is noteworthy that this study considered the cumulative impact of environmental resistance on the dispersal of Rhodiola, ensuring that the corridor pathways align with the actual ecological processes of dispersing species. By establishing both primary corridors and secondary corridors within the selected ecological source areas, this approach not only connects interprovincial core sources, breaking the constraints of regional boundaries and highlighting the integrity of ecosystems, but also fills intra-provincial networks to meet current conservation needs.

The long-distance corridors of Rhodiola crenulata provide pathways for the species to migrate toward higher latitudes, directly responding to its future northward expansion trend of the adaptive area. The prioritized primary corridors originate within Tibet, pass through Gansu Province, and reach Qinghai Province, linking the two ecological barriers of the Bayan Har Mountains and Kunlun Mountains. This connects previously isolated and scattered ecological patches through corridors forming a continuous ecosystem, thereby providing essential habitat space and migration pathways for various endangered species along the corridors. Under future climate stress, in response to the northward expansion trend of Rhodiola crenulata, it is necessary to extend the existing primary corridor terminus in Hezuo City, Gansu Province northward to the Inner Mongolia border and pre-establish climate migratory dynamic corridors. For Rhodiola tangutica, due to its narrow distribution and weak migration capacity, two primary corridors and one secondary corridor were established within Qinghai Province to prioritize in situ conservation of this endangered species [65], ensuring connectivity between core habitats. These corridors are designed to mitigate the negative impacts of habitat fragmentation by promoting gene flow among sub-populations, which is essential for maintaining genetic diversity and evolutionary potential under changing environmental conditions [66]. Furthermore, as future climate change causes a progressive reduction in the habitat area of Rhodiola tangutica, single corridor restoration can no longer meet its conservation and management needs. On this basis, in situ conservation measures such as mountain closure for forest cultivation can be implemented around the corridors, applying special protection and management [67] to maintain habitat integrity and prevent further fragmentation caused by human activities.

In summary, this study has systematically identified a potential ecological corridor network for two endangered Rhodiola species, providing a direct basis for current conservation planning. It should be noted, however, that the constructed network reflects a “baseline” condition under current environmental settings. As the structure and functionality of corridors may shift dynamically with environmental changes, their long-term robustness requires further assessment. A key future direction involves applying this analytical framework to multiple climate and land use scenarios. By comparing the stability of corridor patterns across different scenarios, the resilience of currently identified key corridors can be evaluated, thereby supporting the development of more adaptive strategies for dynamic conservation network planning.

5. Conclusions

As a keystone species in alpine ecosystems, Rhodiola plants play a crucial role in maintaining water conservation and biodiversity on the Tibetan Plateau. However, under the dual pressures of climate change and human activities, their adaptive distribution may undergo changes and face migration challenges. This study integrated species distribution models with landscape ecology methods to predict the potential distribution patterns of Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica under current and future climate scenarios, constructed ecological corridors, and quantitatively analyzed corridor categories. Our findings reveal the following:

Under current climate conditions, Rhodiola crenulata primarily inhabits the southern Tibetan Plateau, with its adaptive area accounting for 33% of the plateau. In contrast, Rhodiola tangutica is mainly concentrated in the northeastern Tibetan Plateau, featuring a narrow adaptive area that covers 26.5% of the region. BIO4 is identified as the most influential factor for Rhodiola crenulata, while BIO12 is the key driver for Rhodiola tangutica. Under future climate scenarios, the adaptive area of Rhodiola crenulata is projected to expand northward, gradually shifting toward higher latitudes. The adaptive area of Rhodiola tangutica is expected to contract southward, though overall, it shows a trend of migrating toward higher latitudes with increasing carbon emissions. To better protect these endangered Rhodiola species, ecological sources are selected in the southern and eastern adaptive areas of the Tibetan Plateau, respectively. Six ecological source points are identified, and three primary corridors and four secondary corridors are established accordingly.

This study not only reveals the distribution dynamics of the two Rhodiola species under future climate conditions but also proposes conservation strategies based on ecological corridor optimization. These strategies aim to enhance gene flow among populations, improve long-term ecosystem stability, and provide a scientific basis for the conservation and sustainable management of alpine vegetation on the Tibetan Plateau.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16121865/s1, Figure S1: Adaptive Distribution of Rhodiola crenulata Under Future Climate Scenarios; Figure S2: Adaptive Distribution of Rhodiola tangutica Under Future Climate Scenarios; Figure S3: Centroid Shift Trajectories of two Rhodiola Species; Table S1: Key parameter configurations for each algorithm used in the Species Distribution Models; Table S2: Prediction accuracy and standard deviation of the two Rhodiola species models; Table S3: Changes in the Adaptive Area for Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica under Future Climate Scenarios; Table S4: Contraction and Expansion Rates of Rhodiola crenulata and Rhodiola tangutica under Future Climate Scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z.; methodology, H.Z.; software, L.M.; validation, H.Z., Y.Z. and Z.W.; formal analysis, L.M.; investigation, H.Z. and L.M.; resources, H.Z.; data curation, L.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z. and L.M.; writing—review and editing, H.Z., L.M., Y.Z., Z.W. and Z.L.; visualization, L.M.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, H.Z. and Z.L.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Water Pollution Control and Treatment Science and Technology Major Project (2017ZX07101) and the Discipline Construction Program of HuayongZhang, Distinguished Professor of Shandong University, School of Life Sciences (61200082363001).

Data Availability Statement

All links to input data are reported in the manuscript and all output data are available upon request to the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mboka, J.M.; Kouna, S.B.; Chouto, S.; Djuidje, F.K.; Nguy, E.B.; Fotso-Kamga, G.; Matsaguim, C.N.; Fotso-Nguemo, T.C.; Nghonda, J.P.; Vondou, D.A.; et al. Simulated Impact of Global Warming on Extreme Rainfall Events over Cameroon during the 21st Century. Weather 2021, 76, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, W.D.; Smith, C.B. What Are the Effects of Global Warming? In The Global Climate Crisis; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 75–103. ISBN 978-0-443-27322-3. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, N.; Salzmann, U.; Hutchinson, D.K.; Strother, S.L.; Pound, M.J.; Utescher, T.; Brugger, J.; Hickler, T.; Hocking, E.P.; Lunt, D.J. Global Vegetation Zonation and Terrestrial Climate of the Warm Early Eocene. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2025, 261, 105036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wo, J.; Keiling, T.; Chen, Y. Unraveling Drivers and Patterns of Species Richness in Coastal Marine Ecosystem under Global Warming: Insights from Ecosystem Connectivity. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellweger, F.; De Frenne, P.; Lenoir, J.; Vangansbeke, P.; Verheyen, K.; Bernhardt-Römermann, M.; Baeten, L.; Hédl, R.; Berki, I.; Brunet, J.; et al. Forest Microclimate Dynamics Drive Plant Responses to Warming. Science 2020, 368, 772–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casazza, G.; Abeli, T.; Bacchetta, G.; Dagnino, D.; Fenu, G.; Gargano, D.; Minuto, L.; Montagnani, C.; Orsenigo, S.; Peruzzi, L.; et al. Combining Conservation Status and Species Distribution Models for Planning Assisted Colonisation under Climate Change. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 2284–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.J.; Neilson, R.P.; Dale, V.H.; Flather, C.H.; Iverson, L.R.; Currie, D.J.; Shafer, S.; Cook, R.; Bartlein, P.J. Global Change in Forests: Responses of Species, Communities, and Biomes. Bioscience 2001, 51, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Belmar, M.; Tantillo, M.F.; Sarà, G. Impacts of Increasing Temperature Due to Global Warming on Key Habitat-Forming Species in the Mediterranean Sea: Unveiling Negative Biotic Interactions. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 50, e02844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, R.; Lenoir, J.; Piedallu, C.; Riofrío-Dillon, G.; De Ruffray, P.; Vidal, C.; Pierrat, J.-C.; Gégout, J.-C. Changes in Plant Community Composition Lag behind Climate Warming in Lowland Forests. Nature 2011, 479, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Ochoa-Hueso, R.; Sun, W.; Piñeiro, J.; Power, S.A.; Wang, J.; Singh, B.K.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. Pre-Existing Global Change Legacies Regulate the Responses of Multifunctionality to Warming. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 204, 105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munz, L.; Mosimann, M.; Kauzlaric, M.; Martius, O.; Zischg, A.P. Storylines of Extreme Precipitation Events and Flood Impacts in Alpine and Pre-Alpine Environments under Various Global Warming Levels. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; He, Y.; Guan, X. Increasing Trends of Land and Coastal Heatwaves under Global Warming. Atmos. Res. 2025, 318, 108007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Thompson, L.; Yang, W.; Yu, W.; Gao, Y.; Guo, X.; Yang, X.; Duan, K.; Zhao, H.; Xu, B.; et al. Different Glacier Status with Atmospheric Circulations in Tibetan Plateau and Surroundings. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diffenbaugh, N.S.; Giorgi, F. Climate Change Hotspots in the CMIP5 Global Climate Model Ensemble. Clim. Change 2012, 114, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-C.; Hill, J.K.; Ohlemüller, R.; Roy, D.B.; Thomas, C.D. Rapid Range Shifts of Species Associated with High Levels of Climate Warming. Science 2011, 333, 1024–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Luo, T.; Tang, Y.; Du, M.; Zhang, X. The Altitudinal Distribution Center of a Widespread Cushion Species Is Related to an Optimum Combination of Temperature and Precipitation in the Central Tibetan Plateau. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 88, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, H.K.; Rana, S.K.; Sun, H.; Luo, D. Genomic Signatures of Habitat Isolation and Paleo-Climate Unveil the “Island-like” Pattern in the Glasshouse Plant Rheum Nobile. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 58, e03471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Sun, L.; Pritchard, H.W.; Yang, J.; Sun, H.; Li, Z. Species Distribution Modelling and Seed Germination of Four Threatened Snow Lotus (Saussurea), and Their Implication for Conservation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 17, e00565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wu, R.; Wu, M.; Liu, J.; Yan, H.; Nie, W.; Bao, Z. Predicting the Impacts of Climate Change on the Distribution of Rare Meconopsis Species in China: Habitat Shifts and Conservation Implications. Ecol. Front. 2026, 46, 82–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, A.B.; Li, H.L.; Luo, P.; Zhao, W.J.; Long, X.C.; Brinckmann, J.A. There “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough”?: The Drivers, Diversity and Sustainability of China’s Rhodiola Trade. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 252, 112379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Sun, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Malik, I.; Wistuba, M.; Yu, R. Predicting the Potential Geographical Distribution of Rhodiola L. in China under Climate Change Scenarios. Plants 2023, 12, 3735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Nazhand, A.; Coêlho, A.G.; Souto, E.B.; Arcanjo, D.D.R.; Santini, A. Rhodiola Rosea: Main Features and Its Beneficial Properties. Rend. Lincei Sci. Fis. E Nat. 2022, 33, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, T.; Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Ge, X. Genetic Variation within and among Populations of Rhodiola alsia (Crassulaceae) Native to the Tibetan Plateau as Detected by ISSR Markers. Biochem. Genet. 2005, 43, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.-Q.; Meng, S.-Y.; Allen, G.A.; Wen, J.; Rao, G.-Y. Rapid Radiation and Dispersal out of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau of an Alpine Plant Lineage Rhodiola (Crassulaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014, 77, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, D.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, Y. The Lost Biodiversity and Degraded Alpine Wetlands Caused by Strong Earthquake on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Did Not Self-Restore in the Short Term. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 50, e02830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, G. Altitudinal Patterns of Maximum Plant Height on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Plant Ecol. 2016, 11, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, T.; Li, X.; Yao, H.; Lin, Y.; Ma, X.; Cheng, R.; Song, J.; Ni, L.; Fan, C.; Chen, S. Survey of Commercial Rhodiola Products Revealed Species Diversity and Potential Safety Issues. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.P. Harnessing the World’s Biodiversity Data: Promise and Peril in Ecological Niche Modeling of Species Distributions. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1260, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozhoridze, G.; Orlovsky, N.; Orlovsky, L.; Blumberg, D.G.; Golan-Goldhirsh, A. Geographic Distribution and Migration Pathways of Pistacia–Present, Past and Future. Ecography 2015, 38, 1141–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lembrechts, J.J.; Nijs, I.; Lenoir, J. Incorporating Microclimate into Species Distribution Models. Ecography 2019, 42, 1267–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracy, J.L.; Kantola, T.; Baum, K.A.; Coulson, R.N. Modeling Fall Migration Pathways and Spatially Identifying Potential Migratory Hazards for the Eastern Monarch Butterfly. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guisan, A.; Thuiller, W. Predicting Species Distribution: Offering More than Simple Habitat Models. Ecol. Lett. 2005, 8, 993–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Subedi, S.C.; Bhandari, S.; Baral, K.; Lamichhane, S.; Maraseni, T. Climate-driven Decline in the Habitat of the Endemic Spiny Babbler (Turdoides nipalensis). Ecosphere 2023, 14, e4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Elith, J.; Guillera-Arroita, G.; Lahoz-Monfort, J.J. A Review of Evidence about Use and Performance of Species Distribution Modelling Ensembles like BIOMOD. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 839–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuiller, W.; Lafourcade, B.; Engler, R.; Araújo, M.B. BIOMOD—A Platform for Ensemble Forecasting of Species Distributions. Ecography 2009, 32, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, W.; Liang, Y. Analysis of the Potential Distribution of Shoot Blight of Larch in China Based on the Optimized MaxEnt and Biomod2 Ensemble Models. Forests 2024, 15, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; An, Q.; Huang, S.; Tan, G.; Quan, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liao, H. Biomod2 Modeling for Predicting the Potential Ecological Distribution of Three Fritillaria Species under Climate Change. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, B.; Huang, T.; Chen, H.; Yue, J.; Tian, Y. Responses of the Distribution Pattern of the Suitable Habitat of Juniperus Tibetica Komarov to Climate Change on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Forests 2023, 14, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z. Climate Change Drives Shifts in Suitable Habitats of Three Stipa Purpurea Alpine Steppes on the Western Tibetan Plateau. Diversity 2025, 17, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Zou, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z. Global Warming Drives Transitions in Suitable Habitats and Ecological Services of Rare Tinospora Miers Species in China. Diversity 2024, 16, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wu, N.; Shi, Z.; Li, C.; Jiang, N.; Fu, C.; Wang, M. Biomod2 for Evaluating the Changes in the Spatiotemporal Distribution of Locusta migratoria tibetensis Chen in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau under Climate Change. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 58, e03508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Xia, Y.; Shen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Xiang, M.; Yang, Y. Genetic Diversity Analysis and Potential Suitable Habitat of Chuanminshen violaceum for Climate Change. Ecol. Inform. 2023, 77, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, I.J.C.; Biondi, D.; Corte, A.P.D.; Reis, A.R.N.; Oliveira, T.G.S. A Methodological Framework to Create an Urban Greenway Network Promoting Avian Connectivity: A Case Study of Curitiba City. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 87, 128050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, W. Identify Ecological Corridors and Build Potential Ecological Networks in Response to Recent Land Cover Changes in Xinjiang, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Cheng, Q.; Wang, M. Construction and Evaluation of the Panjin Wetland Ecological Network Based on the Minimum Cumulative Resistance Model. Ecol. Model. 2025, 505, 111118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhu, C.; Fan, X.; Li, M.; Xu, N.; Yuan, Y.; Guan, Y.; Lyu, C.; Bai, Z. Analysis of Ecological Network Evolution in an Ecological Restoration Area with the MSPA-MCR Model: A Case Study from Ningwu County, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 170, 113067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Cui, X.; Sun, J.; Li, T.; Wang, Q.; Ye, X.; Fan, B. Analysis of the Distribution Pattern of Chinese Ziziphus Jujuba under Climate Change Based on Optimized Biomod2 and MaxEnt Models. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 132, 108256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xiang, D.; Wang, J.; Jiang, K.; Zhu, H.; Huang, S.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H. Comparative Analysis of Modeling Methods and Prediction Accuracy for Japanese Sardine Habitat under Three Climate Scenarios with Differing Greenhouse Emission Pathways. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 215, 117867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Hu, X.; Li, Q.; Liu, L.; He, Y.; Chen, C. Gap Analysis of Firmiana danxiaensis, a Rare Tree Species Endemic to Southern China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.-L.; Mambo, W.W.; Liu, J.; Zhu, G.-F.; Khan, R.; Abdullah; Khan, S.M.; Lu, L. Spatiotemporal Range Dynamics and Conservation Optimization for Endangered Medicinal Plants in the Himalaya. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2025, 57, e03390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Ma, Y.; Salama, M.S.; Su, Z. Assessment of Vegetation Dynamics and Their Response to Variations in Precipitation and Temperature in the Tibetan Plateau. Clim. Change 2010, 103, 519–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, D.; Ge, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Cui, A.; Dong, Y.; Zuo, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, N.; et al. Climate Change Was More Important than Human Activity in Late Holocene Vegetation Change on the Southern Tibetan Plateau. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2025, 354, 109245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Zhang, S.; Hua, T.; Sun, J.; Zhao, W. Spatiotemporal Variations in Alpine Grassland Quality and Its Response to Climate Change and Grazing Activity on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Front. 2025, 45, 1595–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, G. Vulnerability of Phenological Synchrony between Plants and Pollinators in an Alpine Ecosystem. Ecol. Res. 2014, 29, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Manincor, N.; Fisogni, A.; Rafferty, N.E. Warming of Experimental Plant–Pollinator Communities Advances Phenologies, Alters Traits, Reduces Interactions and Depresses Reproduction. Ecol. Lett. 2023, 26, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Y. Heterogeneous Impacts of Human Activities and Climate Change on Transformed Vegetation Dynamics on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 392, 126575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Song, X.; Hu, R.; Guo, D. Ecosystem-Dependent Responses of Vegetation Coverage on the Tibetan Plateau to Climate Factors and Their Lag Periods. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cai, M.; Shao, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, D. Vegetation and Climate Change since the Late Glacial Period on the Southern Tibetan Plateau. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2021, 572, 110403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Keyimu, M.; Zeng, F.; Liu, Y. Modeling Future Changes in Potential Habitats of Five Alpine Vegetation Types on the Tibetan Plateau by Incorporating Snow Depth and Snow Phenology. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chmura, H.E.; Kharouba, H.M.; Ashander, J.; Ehlman, S.M.; Rivest, E.B.; Yang, L.H. The Mechanisms of Phenology: The Patterns and Processes of Phenological Shifts. Ecol. Monogr. 2019, 89, e01337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykhailenko, O.; Jalil, B.; McGaw, L.J.; Echeverría, J.; Takubessi, M.; Heinrich, M. Climate Change and the Sustainable Use of Medicinal Plants: A Call for “New” Research Strategies. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1496792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.M.; Brudvig, L.A.; Clobert, J.; Davies, K.F.; Gonzalez, A.; Holt, R.D.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Sexton, J.O.; Austin, M.P.; Collins, C.D.; et al. Habitat Fragmentation and Its Lasting Impact on Earth’s Ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Y.; Ma, N.; Zhang, Y.; Zang, C.; Szilagyi, J.; Tian, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z.; Tang, Z.; Wei, H. Response of Alpine Vegetation Function to Climate Change in the Tibetan Plateau: A Perspective from Solar-Induced Chlorophyll Fluorescence. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 952, 175845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Meng, S.; Rao, G. Quaternary Climate Change and Habitat Preference Shaped the Genetic Differentiation and Phylogeography of Rhodiola Sect. Prainia in the Southern Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 9, 8305–8319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares-Filho, B.; Moutinho, P.; Nepstad, D.; Anderson, A.; Rodrigues, H.; Garcia, R.; Dietzsch, L.; Merry, F.; Bowman, M.; Hissa, L.; et al. Role of Brazilian Amazon Protected Areas in Climate Change Mitigation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10821–10826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Chacón, C.; Valderrama-A, C.; Klein, A.-M. Biological Corridors as Important Habitat Structures for Maintaining Bees in a Tropical Fragmented Landscape. J. Insect Conserv. 2020, 24, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smithers, R.J.; Blicharska, M. Indirect Impacts of Climate Change. Science 2016, 354, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).