1. Introduction

The charcoal production sector in Brazil primarily utilizes raw materials from planted and sustainably managed forests [

1]. This practice reduces pressure on native forests and significantly contributes to a low-carbon economy. Charcoal produced from planted forests is a more sustainable and environmentally responsible alternative, reducing greenhouse gas emissions compared to mineral coal [

2,

3]. The production of charcoal from planted forests also generates jobs and income in rural areas, contributing to the economic and social development of these regions [

4]. Thus, the charcoal sector in Brazil plays a crucial role in the transition to a greener and more sustainable economy, aligning with global objectives for carbon emission reduction and climate change mitigation.

The expansion of the charcoal production sector depends on the creation of new technologies, such as continuous carbonization, to maintain the product’s competitiveness, especially against mineral coal [

5]. This process allows for greater efficiency and control in the conversion of biomass into charcoal. Unlike traditional methods, continuous carbonization uses advanced technologies that ensure uniform and constant burning, resulting in a higher quality product with lower pollutant emissions [

6]. Furthermore, this process optimizes the use of raw materials, reducing waste and increasing productivity. Continuous carbonization also contributes to the sustainability of the sector, as it can be integrated into energy recovery systems, such as the generation of heat and electricity from gases released during carbonization. Therefore, the adoption of continuous carbonization technologies is essential to promote cleaner, more efficient and sustainable charcoal production.

Wood drying is a crucial process in charcoal production [

7,

8], especially in continuous carbonization. Wet wood, when subjected to pyrolysis, releases water, requiring more energy and affecting charcoal quality. Dry wood ensures higher yield and better charcoal quality, in addition to reducing energy consumption and pollutant emissions [

9,

10,

11]. Artificial drying, compared to natural drying, offers advantages such as higher speed, precise moisture control, less dependence on climatic conditions, and reduced losses due to pest attacks [

12,

13]. Although artificial drying requires an initial investment, it can offer greater efficiency and long-term benefits. However, these systems may consume significant amounts of energy, particularly when heat recovery is not implemented, which can reduce overall efficiency and increase environmental impact [

14,

15]. Several technologies are available for artificial drying, including fixed-bed, fluidized-bed, rotary, microwave, and screw dryers [

16,

17,

18]. In fixed-bed systems, factors such as bed depth and airflow are critical for achieving uniform and efficient drying [

19]. Advanced methods, such as combining microwaves with superheated steam, can dramatically accelerate the drying process compared to conventional approaches [

20]. Microwave drying also enables precise control of temperature and moisture, improving wood permeability without compromising structural integrity [

21], while rotary dryers are widely used for chips and residues, effectively reducing moisture and enhancing energy value [

22].

Beyond the choice of technology, the characteristics of the biomass play a decisive role in drying performance. For example, log diameter strongly influences drying rate and uniformity, with smaller logs drying faster [

23]. Efficiency is also affected by the heat source and its application method. Integrating heat from carbonization gases into the drying process can reduce reliance on external fuels, provided the thermal supply remains stable. Overall, log geometry and the effective use of available heat are key factors for optimizing artificial drying [

24]. The choice between drying methods depends on factors such as wood type, production scale and costs [

24,

25].

Despite advances in continuous carbonization systems, there is still limited knowledge about how cutting arrangement, log diameter, and drying time influence heating, moisture loss, and energy efficiency during artificial drying in a fixed bed. Understanding these factors is essential to optimize drying, reduce energy consumption, and increase productivity in continuous carbonization, as well as to ensure the quality of the charcoal produced. Therefore, this study aimed to develop and evaluate an experimental fixed-bed drying system for eucalyptus logs, analyzing the effects of log geometry and residence time. Our hypothesis is that logs with smaller diameters exhibit greater drying efficiency. The results obtained will provide information for the planning and operation of industrial drying processes, contributing to more efficient, safe, and sustainable technologies in the charcoal production sector.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Material

The study used trees from a seven-year-old hybrid of Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill ex Maiden × Eucalyptus urophylla S.T. Blake cultivated in Paraopeba–MG, Brazil (−44.409 19° 16′ 54″ South, 44° 24′ 32″ West). The choice of Eucalyptus grandis × Eucalyptus urophylla was based on its widespread use in the Brazilian charcoal industry, where it represents one of the most common and economically important species for energy production. The logs were classified into four diameter classes and prepared in three cutting layouts (40 cm, 20 cm, and split).

2.2. Development and Construction of the Artificial Wood Drying System

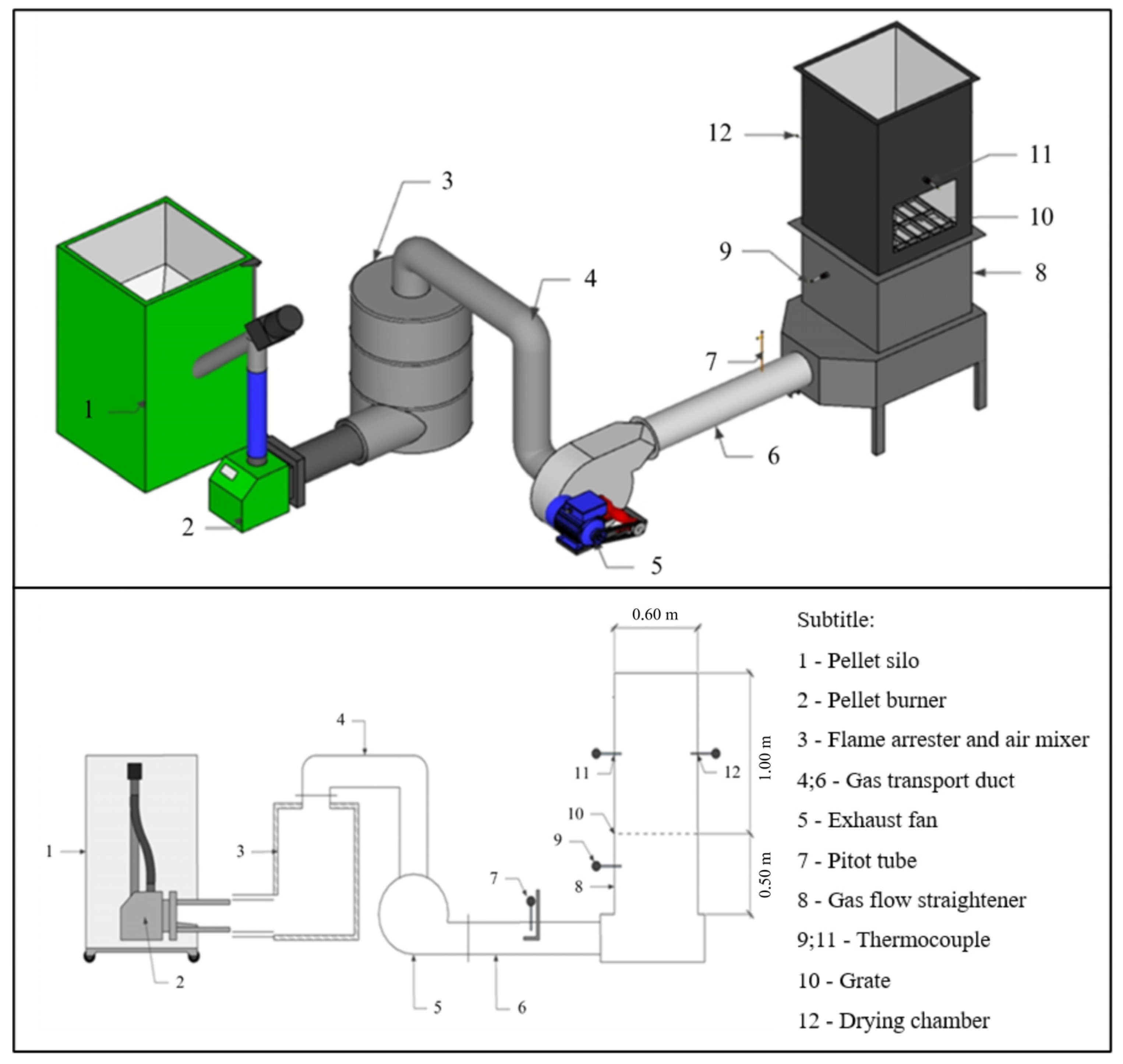

A wood drying system was developed to simulate artificial drying conditions at elevated temperatures, aiming to support the design of an industrial-scale log dryer (

Figure 1). The system employs a horizontal burner powered by wood pellets to generate hot gases. The experimental system was developed using a pellet burner (model QPJet, Lipel, Brazil) connected to a fixed-bed drying chamber designed for controlled high-temperature drying, chosen for its ability to provide a stable heat supply and simulate industrial conditions for continuous carbonization. The burner comprises a pellet reservoir, an auger feeder, a combustion fan, an electric ignition chamber, and thermocouples for temperature monitoring and control. To prevent direct flame contact with the exhaust system and to regulate gas temperature, an air mixer lined with ceramic fiber was installed, ensuring uniform heat distribution and operational safety.

The hot gases were conveyed to the drying chamber through carbon steel pipes insulated with ceramic fiber. A centrifugal exhaust fan was employed to draw the gases and direct them into the chamber, where a Pitot tube was used to measure the flow rate. The drying chamber, rectangular in shape, consists of two compartments: a lower section designed to straighten and stabilize the gas flow, and an upper section equipped with a grate to support the wood samples. This upper compartment also includes access openings for sample loading and thermocouples for temperature monitoring.

2.3. Artificial Wood Drying

Prior to the drying process, five bark-covered logs were selected to determine their initial moisture content. Discs were extracted from both ends and the center of each log and subsequently oven-dried at 103 ± 2 °C until a constant weight was achieved. The moisture content of the samples was then calculated using Equation (1):

where

W = Wood moisture content;

Wm = Wet mass;

Dm = Dry mass.

The average moisture content of the discs was considered representative of the initial moisture content of the logs subjected to drying. Each log designated for drying was weighed to determine its initial mass, and two thermocouples were inserted to monitor internal temperature during the drying process (

Figure 2). The thermocouple insertion points were created using a 3 mm drill bit. Type J thermocouples were used, featuring a 2 mm diameter iron stem encased in a braided fiber mesh for thermal protection and durability.

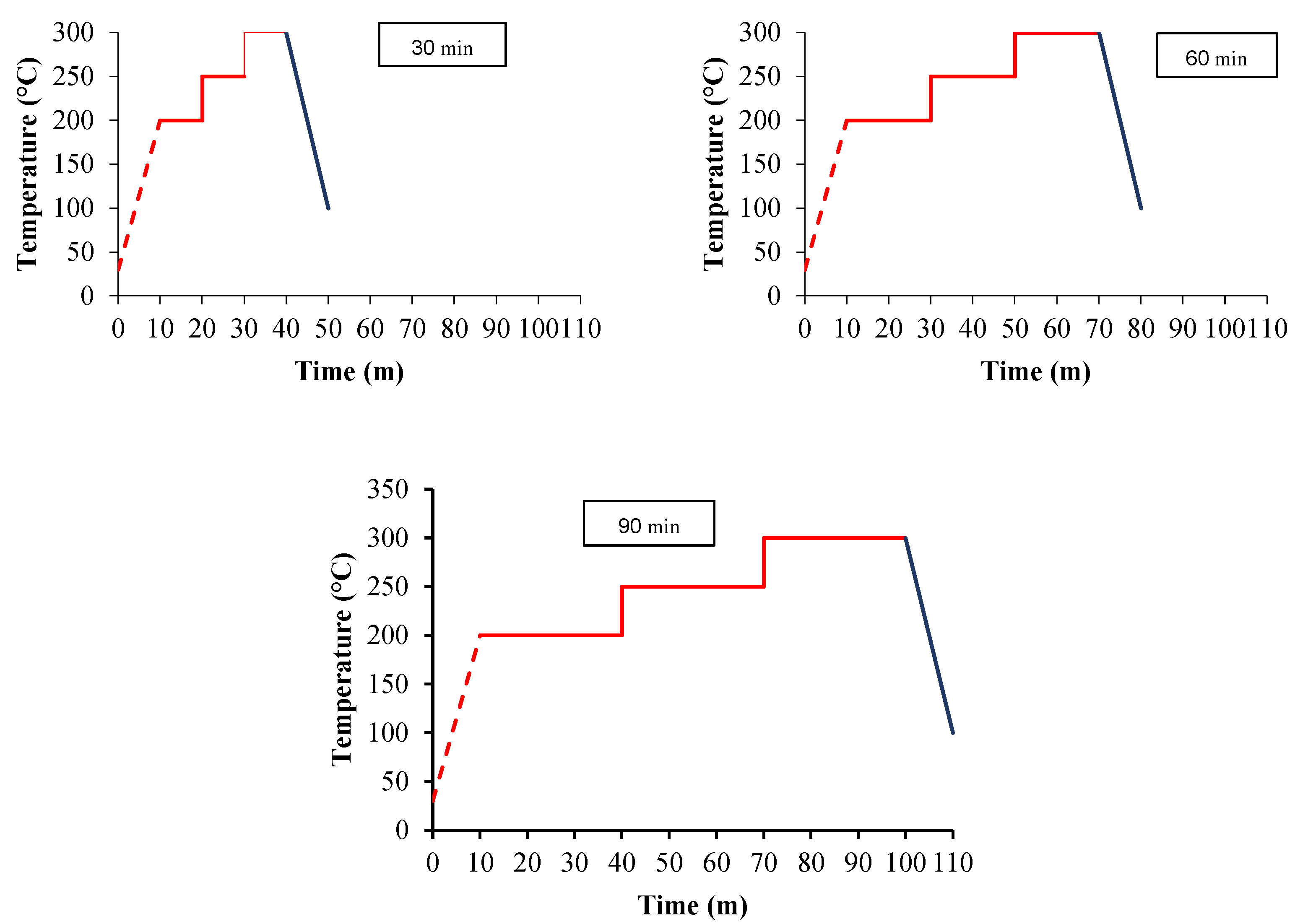

After the insertion of the thermocouples, the wood logs were loaded into the drying chamber, forming two layers: the first with logs of different diameter classes and the second with logs of medium diameter. The samples were previously weighed to determine the initial total mass. With the chamber closed, drying was initiated by igniting the pellet burner and turning on the fan. The drying process was carried out in three stages, lasting 30, 60, and 90 min (

Figure 3).

The wood drying process was carried out in three stages:

First stage: Heating the drying chamber up to 200 °C for ten minutes.

Second stage: Temperature increase up to 300 °C, with variation in the drying rate depending on the residence time. For durations of 30 and 60 min, the temperature was increased by 50 °C every 20 min. For 90 min, the increase was 50 °C every 30 min. This gradual increment was necessary to maintain a constant drying rate.

Third stage: Cooling, where after the drying time, the burner was turned off, and the samples remained in the chamber for an additional 10 min to reduce the temperature to approximately 100 °C.

After drying, the wood samples were weighed to determine the final mass and the amount of water removed. Samples of each diameter were prepared to obtain the moisture profile.

2.4. Moisture Profile

Two types of sectioning were performed on the collected wood samples to create the moisture profile of the logs after drying, varying according to the cutting layout and the length of the logs:

40 cm logs: Sectioned into three regions (P1, C, and P2) of 13.3 cm each, subdivided into nine parts in the transverse plane.

20 cm logs: Sectioned into two regions (P1 and P2) of 10 cm each, subdivided into nine parts in the transverse plane.

Cracked logs: Sectioned into three regions (P1, C, and P2) of 13.3 cm each, subdivided into six parts in the transverse plane (

Figure 4).

The collected wood samples were taken to a drying oven at a temperature of 103 ± 2 °C until reaching constant mass for moisture determination. The moisture content of the samples was determined using Equation (1).

2.5. Temperature and Flow Monitoring

During drying, the temperatures of the gas transport system, the dryer, and the interior of the wood logs were monitored and collected every ten minutes. The volumetric flow rate was measured by converting the differential pressure, using a U-tube manometer and Equations (2)–(4).

where

Q = volumetric gas flow rate (m3/h);

V = fluid velocity (m/s);

A = cross-sectional area of the pipeline (m

3).

where

V = fluid velocity, in m/s;

= pressure difference obtained by the manometer (dynamic pressure), in Pascal (Pa);

= fluid density, in kg/m

3.

where

= volumetric flow rate under normal conditions (0 °C and 1 atm) (Nm3/h);

Q = volumetric fluid flow rate (m3/h);

T = fluid temperature (K).

2.6. Drying Rate

The average drying rates for each treatment were obtained according to Equation (5).

where

: drying rate (%/min);

: initial moisture content (%);

: final moisture content (%);

t: time (min)

2.7. Drying Energy Efficiency

The drying energy efficiency was calculated based on the amount of thermal energy supplied for each temperature range of the drying program. The sensible heat supplied for each drying process was calculated according to Equation (6):

where

: sensible heat supplied for drying (kcal);

V: gas flow rate at the dryer inlet (m/s);

: gas density (g/m3);

: specific heat of the gas (Kcal/(kg*K));

T: temperature (K);

t: time (s);

1, 2, 3, 4, and 5: heating stage, first pre-established drying temperature (200 °C), second pre-established drying temperature (250 °C), third pre-established drying temperature (300 °C), and cooling stage, respectively.

The gas flow rate at the dryer inlet was measured with a Pitot tube for each drying stage. The specific heat and density of the gas were obtained from the literature, according to the average temperature of each stage. The amount of energy required to remove free water from the wood was calculated by multiplying the mass of water eliminated by 569 kcal/kg, as per Skaar [

26]. Finally, the thermal energy used to heat the wood logs during the drying stages was estimated (Equation (7)).

where

= amount of heat supplied for wood heating (kcal);

= dry wood mass (kg);

= specific heat of wood (Kcal/(kg.°C));

= temperature (°C);

The specific heat of wood was estimated according to Kollman and Cote [

27], based on Equations (8) and (9).

where

= specific heat of dry wood (kcal/kg.°C);

t = wood temperature (°C);

= specific heat of wood (Kcal/(kg.°C));

= wood moisture content (%/100);

= additional specific heat, due to wood–water binding energy.

The drying efficiency was calculated by dividing the sensible heat supplied by the sum of the energy used to remove free water from the wood and the heat supplied to heat the wood (Equation (10)).

where

= sensible heat supplied for drying (kcal);

= amount of heat supplied for wood heating (kcal);

= amount of heat supplied for water vaporization (kcal).

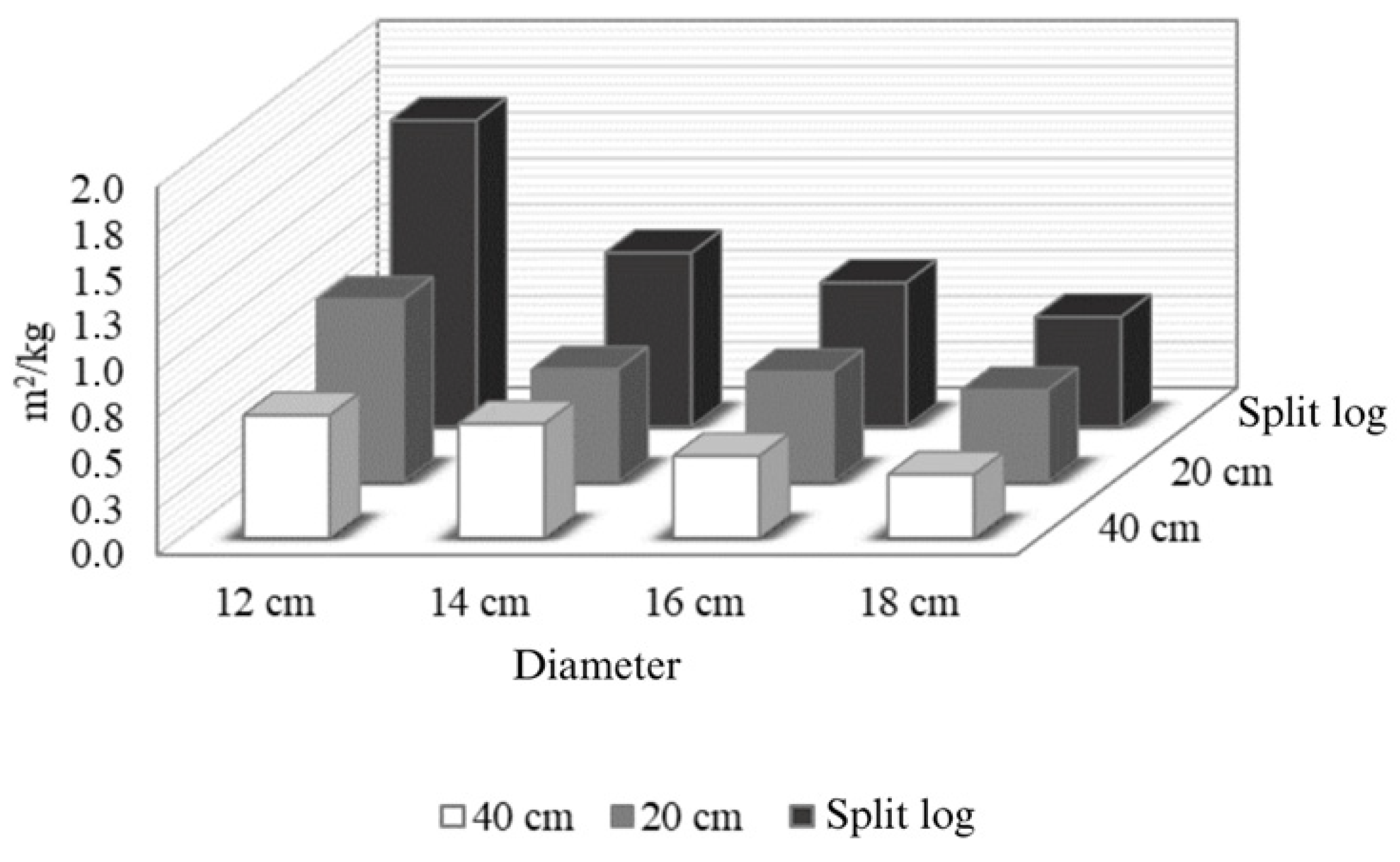

2.8. Wood Area Available for Contact with Flue Gas

The wood area available for contact with the flue gas and its calculation formula, according to the diameter and cutting layout are presented in

Figure 5 and Equation (11).

where

= wood area available for contact with gas (m2/kg);

= wood log area (m2);

= dry wood log mass (kg).

2.9. Data Analysis

The experiment was conducted in a completely randomized design with a triple factorial scheme (3 × 4 × 3) to evaluate the effect of wood cutting layout (40 cm, 20 cm, and cut in half), diameter class (<12 cm, 12.1–14 cm, 14.1–16 cm, and 16.1–18 cm), and residence time in the drying chamber (30, 60, 90 min). Four repetitions were performed, totaling 36 treatments and 144 experimental units.

To explain the effect of the variables on moisture loss, drying rate, and temperature profile in the wood, regression models were fitted. The criteria for selecting the best model included parameter significance, residual standard error, residual distribution, and adjusted coefficient of determination. Response surface and contour plots were created based on these adjustments.

The moisture profile of the wood logs after drying was constructed using Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) interpolation (Equation (12)), which calculates unknown points from the weighted average of sampled points, giving greater weight to closer points [

28].

where

= Estimated value of the property at point 0;

= Value of the property at the known point;

= Distance between point i and point 0;

= Number of known points used in the estimation.

The energy efficiency data, according to residence time and different layouts, were analyzed by ANOVA. When significant differences were found, treatments were compared using Tukey’s test at 5% significance. Statistical analyses were performed in R software (version 3.5.1, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the ‘gstat’ package for interpolation [

29].

3. Results and Discussion

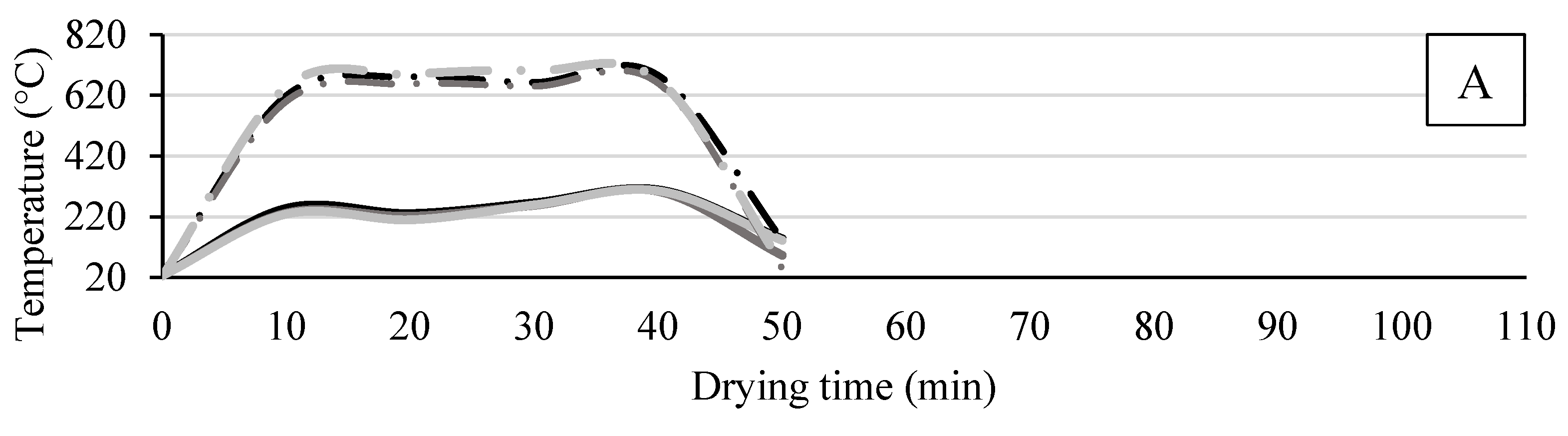

3.1. Thermal Profile of the Drying System

The gas supply system for the dryer reached temperatures exceeding 650 °C to achieve outlet temperatures above 220 °C at the exhaust (

Figure 6). A detailed analysis of the thermal profile throughout the drying system is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of heat and mass transfer involved in the process.

An increase in the dryer inlet temperature from 200 °C to 250 °C required an approximate 40 °C rise in the combustion chamber temperature of the pellet burner. However, to raise the dryer inlet temperature from 250 °C to 300 °C, only a 20 °C increase in the combustion chamber temperature was necessary. This behavior is attributed to the fact that higher inlet temperature demands lead to an increased pellet feed rate to the burner and, consequently, greater air demand for combustion [

30,

31]. Consequently, the flow rate of the combustion gases in the system increases significantly. According to Jia et al. [

32], the increase in gas flow in pellet burners, resulting from higher fuel feeding rates and air velocity, directly affects the temperature profile and gas distribution within the chamber, indicating that more intense flows can transport a higher density of thermal energy. Dessa forma, the resulting increase in the flow rate of combustion gases from the pellet burner, combined with a constant dilution rate in the system, implies that a smaller increase in the combustion chamber temperature is sufficient to achieve the desired rise in the dryer inlet temperature.

Treatments with a 90-min residence time and using 20 cm logs or split logs resulted in combustion, rendering these treatments unfeasible [

33,

34]. When wood is exposed to increasing heat, it may undergo pyrolysis and ignite without an external source, with the ignition time being highly dependent on the heat intensity [

35]. In our study, the larger surface area of the material led to rapid drying and a subsequent temperature rise, which triggered combustion.

The exhaust outlet temperature, after dilution of the combustion gas with atmospheric air, is directly related to the dryer inlet temperature (

Figure 7). Thermal losses between the exhaust outlet and the dryer inlet were approximately 10 °C. The combustion gas pipeline was insulated with ceramic fiber blanket to minimize these losses.

The gas temperatures within the drying chamber followed the pre-established drying schedule, demonstrating strict process control. Drying treatments using split wood exhibited the lowest outlet temperatures from the dryer, indicating more efficient utilization of thermal energy in this cutting layout. This result is consistent with findings reported in the literature, which attribute such efficiency to geometric factors. This configuration presents a higher surface-to-volume ratio, enabling more effective contact between the wood and the heat source, which facilitates greater energy absorption during drying and consequently reduces the outlet temperature of the dryer [

36]. In the same treatment, the shorter distance from the center to the longitudinal surface allowed for faster heat penetration into the internal regions of the wood. Given that wood is a poor conductor of heat [

37,

38], reducing the distance from the core to the periphery is an effective strategy to optimize the drying process [

39,

40].

Similar studies corroborate these mechanisms. Carneiro et al. [

24], confirmed that log diameter and, consequently, geometry and the surface-to-volume ratio significantly affect drying efficiency when studying different diameters of

Eucalyptus urophylla. Complementary studies on the same species show that shorter logs dry more rapidly when the moisture content is above the fiber saturation point, due to more efficient heat transfer and faster moisture migration [

41]. Taken together, these findings support that a favorable geometry enhances heat penetration and reduces the time required for moisture removal, which explains the lower dryer outlet temperature observed in the treatments with split wood in the present study.

3.2. Thermal Profile of Wood in Heartwood and Sapwood Regions

The temperature profiles of the sapwood and heartwood of the logs were influenced by the cutting layouts, log diameter, and drying residence time (

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Meanwhile, the moisture prediction models demonstrated high accuracy and low error rates (

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3).

The regression models fitted to predict temperature in both heartwood and sapwood regions exhibited high coefficients of determination (

R2 > 93%), indicating strong predictive capacity and reliability. Notably, the models for sapwood showed lower standard errors, reinforcing the greater thermal uniformity in this region. The significance of quadratic terms in several models suggests nonlinear interactions between diameter and drying time, highlighting the complexity of heat distribution within the wood matrix. The use of quadratic models for controlling the wood drying process was also found to be the most suitable approach for managing air-drying of

eucalyptus logs [

8,

42]. These values validate the quality of the models, supporting their application in predicting moisture content in logs subjected to artificial drying.

Sapwood temperatures were consistently higher than those of heartwood. This pattern is consistent with the thermal profile documented for different wood species. Studies show that the initial heating occurs in the sapwood, which is the region closest to the surface and exhibits higher moisture mobility. Pang [

43] verified that during the drying of

Pinus radiata D. Don, the sapwood reaches higher temperatures during the initial stages, whereas the heartwood exhibits slower heating even under the same external conditions. Similar results were observed in North American hardwoods, reinforcing that heartwood has lower permeability, which delays both moisture migration and temperature increase [

44].

In artificial drying, thermal energy from the combustion gases is transferred to the wood surface, promoting water vaporization and initial heating of the sapwood, which is located in this outer region. Wood has low thermal conductivity and high specific heat, resulting in a low heat transfer rate [

45]. Heating the internal regions, where the heartwood is located, requires greater energy input and longer residence time in the dryer [

24]. In split logs, part of the heartwood was exposed to the external surface, allowing direct contact with the heat source and a greater temperature increase, although still not reaching the levels observed in sapwood within the same time interval.

Logs with larger diameters exhibited lower heating in both sapwood and heartwood, showing greater resistance to convective heat transfer. The increase in wood temperature with longer residence time is attributed to prolonged exposure to the heat source, enhancing heat transfer.

Split wood showed greater heating in both sapwood and heartwood. In 60-min drying treatments, split logs heated 30% more in the sapwood and 20% more in the heartwood compared to 40 cm logs. The heat exchange between the hot gas and the log is proportional to the wood surface area available for convective heat transfer. Split wood has a larger contact area with the gas, resulting in improved heat transfer. In this context, splitting the wood is an important strategy to reduce moisture content and its heterogeneity. These results reinforce the hypothesis that mechanical modifications to log geometry can optimize drying efficiency, as reported by Carneiro et al. [

24].

Treatments involving split and 20 cm logs subjected to 90 min of drying resulted in combustion, indicating a critical threshold of thermal exposure. This phenomenon is associated with the combination of high temperatures and prolonged exposure time, which led to the formation of a dry surface layer [

46]. This layer acted as a barrier to heat conduction and moisture diffusion, causing heat accumulation inside the material and favoring ignition [

47]. The presence of cracks intensified this effect by increasing the exposed surface area and allowing greater oxygen ingress [

48]. These results highlight the need to revise operational parameters for this type of material, with special attention to residence time control and the segregation of pieces with structural defects, in order to prevent combustion risks, material losses, and compromise of process safety.

In summary, the observed thermal profiles reinforce the need for customized drying protocols based on wood quality and processing layout. Optimizing these parameters can significantly improve energy efficiency and product quality in continuous carbonization systems.

3.3. Wood Moisture Loss and Drying Rate

The results clearly demonstrate that residence time, log diameter, and cutting layout significantly influence both moisture loss and drying rate during artificial drying (

Figure 11). The statistical models developed for these variables exhibited high adjusted R

2 values (above 96%) and low residual standard errors, confirming their robustness and predictive accuracy (

Table 4).

Regression models also revealed nonlinear interactions between diameter and drying time, especially in cracked logs, suggesting that complex thermal dynamics govern moisture migration in wood. The equations fitted to the models that best explained moisture loss in the logs, as a function of diameter and drying residence time, showed satisfactory residual standard errors (Sy.x) ranging from 0.20 to 0.39 and adjusted coefficients of determination (R2) between 90 and 91%.

Moisture loss, and consequently the drying rate, was higher at the beginning of the drying process. At this stage, the greater moisture gradient between the wood and the external environment facilitates water movement to the outside [

13,

49]. Additionally, this phase is marked by the loss of free water, which is connected to the wood through weak capillary bonds, requiring low energy input for its removal [

50]. This behavior was also observed during the artificial drying of

Pinus, in which the drying rate progressively decreased as the residual moisture content diminished, indicating that the initial removal of water occurs more intensively [

51]. This effect was intensified in cracked logs due to the shorter path water must travel within the wood to reach the exterior, highlighting that smaller log diameters favor the drying process. This occurs because, during tree growth, the increase in trunk diameter results from the successive addition of cell wall layers over the years. Consequently, during drying, water migrates from the interior toward the wood surface through these structural layers [

52]. Thus, in larger-diameter logs, water must pass through a greater number of layers than in smaller logs, which imposes greater resistance to its movement [

53]. Over time, the moisture gradient between the wood and the environment decreases. Furthermore, bound water is removed, which is connected through strong hydrogen bonds and requires more energy for its removal, thereby reducing the drying rate of the logs [

12].

Smaller diameters showed greater moisture loss and drying rates. Logs with larger diameters are more resistant to heat transfer to the central region and have lower permeability. Wood permeability is higher in the longitudinal direction, and the presence of extractives and tyloses in the heartwood increases resistance to flow.

Residence time played a crucial role in drying performance. Although longer exposures (60 min) improved drying efficiency, 90-min treatments resulted in combustion in cracked and 20 cm logs, indicating a critical limit for safe drying. This reinforces the importance of balancing drying time with log geometry to avoid overheating and material degradation. Cracked wood showed the highest moisture losses and heating rates, about 50% higher than 40 cm wood. The larger surface area exposed to hot gases favors heat transfer by convection and accelerates water evaporation [

54]. Similar results were reported by Erber et al. [

55], who found that split logs exhibited drying rates between two and three times higher, primarily due to the increased surface area exposed to air and the reduced internal path for moisture transport. The shorter radial distance from the center to the surface in cracked logs also facilitates heat penetration, especially considering the low thermal conductivity of wood [

55].

Optimizing drying parameters, especially cutting layout and residence time, is essential to improve energy efficiency and product quality in continuous carbonization systems. In this context, studies based on dynamic modeling and advanced control techniques demonstrate that the automatic regulation of operational variables in the drying process increases operational stability and reduces undesirable oscillations throughout the process [

56]. Thus, the use of predictive models offers a valuable tool for industrial applications, enabling precise control of drying processes and minimizing risks such as combustion.

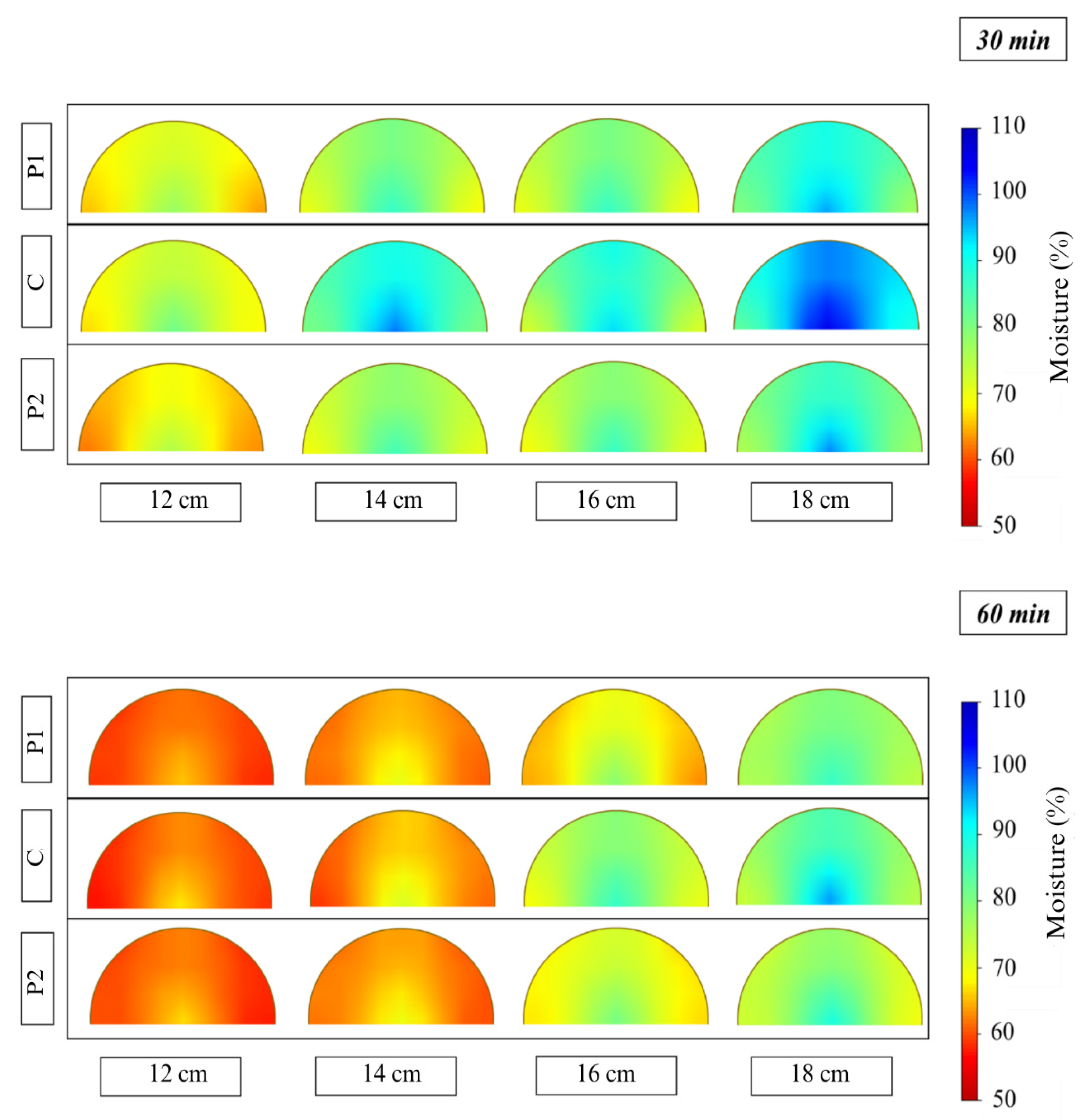

3.4. Moisture Profile

The moisture profiles of the logs (

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14) provide a detailed visualization of moisture distribution as a function of diameter, log region, and drying residence time, for different cutting patterns. These spatial analyses of moisture are crucial for understanding the dynamics of drying and identifying the most critical areas for water removal within the wood matrix.

In all treatments, a moisture gradient was observed from the pith to the bark of the logs. The outer regions of the wood (sapwood) showed lower moisture content, while the central regions (heartwood) retained higher levels. This pattern is consistent with the low thermal conductivity of wood, which limits heat penetration into the inner layers and, consequently, the diffusion of moisture from the core to the surface [

57]. Temperature gradients generated during high-temperature drying cause water particles to move between regions of higher and lower temperature, also creating a water concentration gradient [

58]. These gradients are key driving forces in heat and mass transfer during drying.

The influence of cutting patterns is particularly evident in the moisture profiles. Split logs demonstrated the most uniform moisture profiles and the lowest residual moisture contents compared to the 20 cm and 40 cm long logs (

Figure 14). This observation follows the trend of moisture loss and drying rate and is also attributed to the larger surface area exposed to hot gases, which facilitates convective heat transfer and accelerates water evaporation. Additionally, the reduced radial distance from the center to the surface in split logs shortens the path that water must travel to be removed, optimizing drying efficiency. This geometric modification of the log is an effective strategy to reduce moisture and its heterogeneity, optimizing the drying process.

Split logs with 12 cm diameter, subjected to a 60-min residence time, showed greater homogeneity in post-drying moisture distribution compared to other treatments. The larger surface area in contact with the gas in this treatment enhanced thermal transfer, resulting in a higher drying rate and moisture loss. This confirms the importance of increasing the surface-to-volume ratio to reduce moisture and its heterogeneity in logs [

59]. Consistent results were observed in a metal dryer heated with carbonization gases, in which

eucalyptus logs belonging to smaller diameter classes exhibited shorter drying times and lower final moisture contents when compared to larger-diameter logs. This indicates that drying efficiency is strongly conditioned by both log geometry and the stability of the thermal supply provided by the hot gases [

24].

The analysis of moisture profiles complements the data on moisture loss and drying rate, reinforcing the importance of diameter and cutting pattern—especially split cutting—for optimizing water removal and promoting more homogeneous drying. Precise control of residence time is essential to maximize efficiency without inducing undesirable phenomena such as combustion and ensuring material quality for continuous carbonization.

3.5. Drying Efficiency

Drying efficiency was demonstrated to be impacted by the applied temperature and wood cutting pattern, with the most favorable results observed in split logs subjected to 60 min of drying (

Figure 15). In the 60-min treatment, split logs exhibited the best drying efficiency results and the greatest moisture reduction, making this the most recommended treatment.

The energy efficiency of drying indicates how effectively wood logs utilized the available energy in the dryer for heating and moisture loss. For 40 cm logs, the energy supplied ranged from approximately 9000 kcal for 30 min, to around 19,000 kcal at 60 min, and reached nearly 29,000 kcal at 90 min. However, this increase in supplied energy did not translate linearly into higher efficiency, especially for longer drying times. Split logs exhibited the best energy efficiency due to their larger contact area with the heat source, resulting in higher drying rates and greater moisture loss. Nevertheless, combustion observed in split logs and 20 cm logs after 90 min of drying limited the operational feasibility of these treatments under these conditions. These results are consistent with those reported by Oliveira et al. [

23], who observed that

eucalyptus logs with smaller diameters dry more rapidly and exhibit greater water removal than larger logs. Although the study analyzed only whole logs, the authors emphasized that wood geometry is a determining factor for heat and mass transfer, thereby influencing the energy efficiency of the drying process. However, as in the present study, operational limitations, such as the risk of combustion, must be considered when adopting drying conditions aimed at optimizing energy efficiency.

Logs with improved drying energy efficiency contribute to the optimization of the energy balance during carbonization by reducing the water content in the process [

9,

24]. In carbonization, energy is initially consumed to evaporate water from wood. High moisture content in wood necessitates greater energy input for water removal, which in turn reduces the gravimetric yield of the process and prolongs carbonization time, consequently diminishing the productivity of carbonization kilns. Furthermore, wood moisture content impacts the mechanical strength of the charcoal, leading to increased production of fines; the rapid release of wood vapors can cause cracks, resulting in lower charcoal strength [

9,

42]. Pre-drying is therefore recognized as a vital step for efficient carbonization [

60]. Previous studies have demonstrated that the integration of artificial drying can improve charcoal yield and the overall energy balance of the process [

24], a trend that is confirmed by the results of our study.

The optimization of drying efficiency for eucalyptus logs in continuous carbonization systems critically depends on the combination of cutting pattern and residence time. The treatment involving split logs for 60 min proved to be the most effective, providing a high moisture removal rate with efficient energy utilization and preventing combustion. Artificial drying of logs allows for the use of pre-heated wood at the reactor inlet, favoring the initial stages of carbonization and improving the overall energy balance. Pre-heated wood exhibits lower resistance to heat transfer, thereby increasing the productivity of the continuous carbonization reactor.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the efficiency of artificial drying of eucalyptus logs for continuous carbonization systems is strongly influenced by log geometry and residence time. Split logs, particularly those subjected to 60 min of drying, achieved the highest moisture reduction and energy efficiency, making this configuration the most suitable under the tested conditions. These results highlight the importance of optimizing surface area and diffusion distance to improve heat and mass transfer during drying.

However, the study presents some limitations. The experiments were conducted in a pilot-scale fixed-bed system using a single eucalyptus hybrid and high-temperature conditions, which may restrict the extrapolation of results to industrial-scale operations. Additionally, the tests did not include heat recovery strategies or evaluate the impact of drying on charcoal quality, which are critical aspects for process sustainability and product performance.

Future research should focus on validating these findings in continuous industrial systems, exploring different species and log geometries, and assessing drying protocols at lower temperatures to minimize combustion risks. Studies integrating artificial drying with carbonization units, energy recovery systems, and renewable heat sources could enhance efficiency and reduce environmental impacts. Furthermore, investigations into the mechanical and chemical properties of charcoal produced from pre-dried logs, as well as advanced control strategies for drying processes, would provide valuable insights for improving operational safety and product quality.