Abstract

Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) is a cornerstone timber species in southern China. However, yet its plantation productivity frequently declines under successive rotations, threatening long-term sustainability. While belowground processes are suspected drivers, the mechanisms—particularly plant–soil–microbe interactions—remain poorly resolved. To address this, we examined a chronosequence of C. lanceolata plantations (5, 15, 20, and 30 years) in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, integrating soil physicochemical assays, high-throughput sequencing, and extracellular enzyme activity profiling. We found that near-mature stands (20 years) exhibited a 60.7% decline in mean annual volume increment relative to mid-aged stands (15 years), despite continued increases in individual tree volume—suggesting a strategic shift from resource-acquisitive to nutrient-conservative growth. Peak values of soil organic carbon (32.87 g·kg−1), total nitrogen (2.51 g·kg−1), microbial biomass carbon (487.33 mg·kg−1), and phosphorus (25.65 mg·kg−1) coincided with this stage, reflecting accelerated nutrient turnover and intensified plant–microbe competition. Microbial communities shifted markedly over time: Basidiomycota and Acidobacteria became dominant in mature stands, replacing earlier Ascomycota and Proteobacteria. Random Forest and Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-SEM) identified total nitrogen, ammonium nitrogen, and total phosphorus as key predictors of productivity. PLS-SEM further revealed that stand age directly enhanced productivity (β = 0.869) via improved soil properties, but also indirectly suppressed it by stimulating microbial biomass (β = 0.845)—a “dual-effect” that intensified nutrient competition. Fungal and bacterial functional profiles were complementary: under phosphorus limitation, fungi upregulated acid phosphatase to enhance P acquisition, while bacteria predominately mediated nitrogen mineralization. Our results demonstrate a coordinated “soil–microbe–enzyme” feedback mechanism regulating productivity dynamics in C. lanceolata plantations. These insights advance a mechanistic understanding of rotation-associated decline and underscore the potential for targeted nutrient and microbial management to sustain long-term plantation yields.

1. Introduction

Stand productivity represents a fundamental ecosystem property [1], governing carbon sequestration capacity and ecological stability. In the context of increasing global timber demand and declining productive capacity of natural forests, large-scale afforestation has become a critical strategy for sustainable timber supply and climate-change mitigation [2]. Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata), the dominant plantation species in subtropical China, plays a central role in these efforts. However, successive rotations frequently induce soil degradation attributable to coniferous litter accumulation, progressive acidification, and impaired nutrient cycling [3,4], ultimately constraining stand growth and diminishing long-term carbon sink potential [5]. Although mixed-species plantations can partially offset these negative effects through complementary interactions [6] the mechanisms driving productivity decline in monoculture systems remain insufficiently understood. A comprehensive assessment of dynamic changes in soil nutrients [7,8], microbial characteristics [7,9], and enzyme activities [10] across stand development is therefore essential to elucidate the ecological processes that regulate productivity and to support the sustainable management of these intensively used forests.

Stand productivity emerges from complex interactions between stand structure and soil physicochemical and biological properties [11]. In monocultures where structural simplification reduces the buffering effects of species diversity, soil processes become particularly influential in shaping ecosystem functioning [11]. Within this context, shifts in soil pH, nutrient availability, microbial communities, and extracellular enzyme activities represent key components shaping belowground dynamics. A defining feature of C. lanceolata plantation development is a persistent decline in soil pH, closely linked to coniferous litter decomposition, microbial turnover, and organic acid accumulation [12]. These acidification trends occur alongside notable changes in major nutrient pools. Soil organic carbon generally increases with continuous litter input [13,14], whereas both total and available nitrogen (N) often rise with stand age, reflecting enhanced nitrogen turnover and mineralization [13,15]. By contrast, phosphorus (P), well recognized as the secondary limiting nutrient in highly weathered subtropical soils [10,16,17], exhibits progressively intensifying limitation during stand development [18]. Although plant–soil feedbacks, including root exudation and rhizosphere chemistry, modulate P acquisition, their linkage with microbial functional traits remains insufficiently clarified [19]. The acidification trajectory—co-regulated by litter chemistry, microbial composition, and extracellular enzyme activities [20,21]—emerges as a master driver of nutrient availability and thereby exerts a critical influence on stand productivity [22].

Microorganisms mediate fundamental transformations of soil organic matter and nutrients [23,24], yet their metabolic potential is highly sensitive to stand developmental stage. Young stands enriched in root exudates and labile litter typically sustain higher microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen [25], whereas mature stands characterized by recalcitrant inputs and intensified P limitation often show increased microbial biomass P, reflecting strategic shifts in microbial resource allocation [26]. Such changes in substrate quality and nutrient constraints shape successional microbial trajectories, including shifts from fast-growing copiotrophic taxa (e.g., Proteobacteria) to slow-growing oligotrophic taxa (e.g., Acidobacteria) [3,27], and transitions from Ascomycota- to Basidiomycota-dominated fungal assemblages associated with enhanced lignin-degrading capacity [28]. These changes are accompanied by adjustments in extracellular enzyme activities governing C, N, and P cycling [29,30,31]. Despite extensive evidence that soil nutrients, microbial composition, and enzyme activities individually influence plantation productivity [32,33], the synergistic relationships among these components remain poorly resolved.

Existing studies have largely examined soil properties, microbial dynamics, and enzymatic processes in isolation, limiting understanding of the integrated interactions that modulate plantation productivity. Critical knowledge gaps persist regarding: (1) how progressive shifts in nutrient limitation structure coordinated changes in microbial functional groups and enzyme activities; and (2) how soil, microbial, and enzymatic processes co-regulate productivity across stand development.

To address these gaps, we conducted an integrated investigation along a Chinese fir chronosequence in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province—an area representative of challenges linked to continuous monoculture forestry. Using a space-for-time substitution combined with high-throughput sequencing, enzymatic assays, and comprehensive soil analyses, we aimed to: (1) elucidate mechanisms governing shifts in C, N, and P availability and associated nutrient limitations across stand development; (2) characterize successional patterns of microbial communities and their contributions to nutrient transformation; (3) quantify adaptive responses of extracellular enzyme activities to changing edaphic conditions; and (4) construct a Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Model (PLS-SEM) to identify pathway contributions of soil nutrients, microbial biomass, enzyme activities, and stand structure to stand productivity. Through this integrative approach, we seek to advance mechanistic understanding of belowground processes governing productivity in Chinese fir plantations and to provide a theoretical foundation for sustainable management under successive rotations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Site Description

The experimental site was located in the Fengshushan Forest Farm (29°32′–29°33′ N, 117°36′–117°36′ E), Jingdezhen City, Jiangxi Province, China. The region is characterized by a subtropical monsoon climate, annual sunshine duration of 1800–2000 h, mean annual precipitation of 1650–1850 mm, average relative humidity of 79%, and a mean annual temperature of 17.8 °C. The test plot lies at an elevation of 150 m, characterized by low mountainous and hilly terrain. The soil is a typical red soil (Alisol, WRB) derived from weathered slate and granite, with a soil depth reaching up to 60 cm.

The management of these stands followed conventional regional silvicultural protocols, which typically involved vegetation control measures (e.g., manual weeding) during the early establishment phase. No fertilization, commercial thinning, or other major management interventions have been implemented in any plot during the past five years. This consistent management regime provides an ideal context for investigating plant–soil–microbe interactions without confounding effects from recent anthropogenic disturbances.

The vegetation is dominated by evergreen broad-leaved forest, with major species including C. lanceolata, Gleichenia linearis, Woodwardia japonica, Maesa japonica, Lindera aggregate, Urena lobata, Rubus buergeri, Smilax china. Field observations indicated that the understorey vegetation composition shifted with stand age, transitioning from heliophilous herbaceous species in young stands to shade-tolerant shrubs and herbs in older stands, consistent with successional patterns driven by canopy closure.

2.2. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

In August 2022, we established 12 sample plots (600 m2 each; projected area: 30 m × 20 m) in pure C. lanceolata plantations of different age classes: young stands (5 years), mid-aged stands (15 years), near-mature stands (20 years), and mature stands (30 years), with three replicate plots per age class. A full tree census was conducted in each plot, recording species, diameter at breast height (DBH), tree height, under-branch height, and crown width.

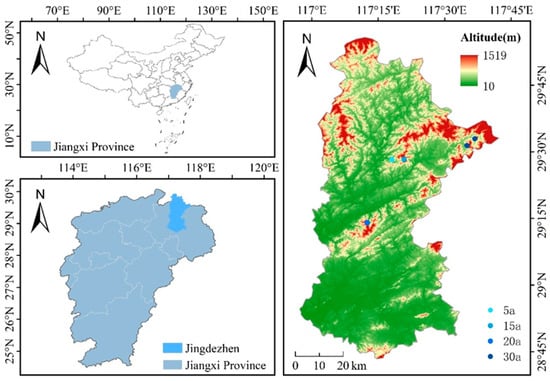

Plot locations were purposively selected to represent typical, even-aged, and healthy monoculture plantations for each target age class, based on the following criteria: (1) uniform canopy closure without major gaps; (2) absence of severe disease, pest infestation, or recent anthropogenic disturbance; (3) comparable slope position (mid-slope) and aspect to minimize topo-edaphic variation; and (4) consistent management history documented in forest farm records. All plots were established within the same forest farm. Within this area, replicate plots of the same age class were positioned in close proximity (>50 m apart to ensure ecological independence) to reduce the influence of localized environmental factors. Consequently, while symbols for these replicates may appear clustered on the regional-scale map (Figure 1), they represent independent sampling units. Different-aged stands were spatially interspersed throughout the forest farm to prevent confounding age effects with strict spatial gradients.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area and spatial distribution of long-term forest monitoring plots in Jingdezhen City, Jiangxi Province, China. The main panel displays a topographic and elevation base map of the broader Jingdezhen region. The red bounding box in the inset (top-left) delineates the exact study area. Sampling plots representing different stand ages (5a: 5 years, 15a: 15 years, 20a: 20 years, 30a: 30 years) are marked with distinct symbols. Essential cartographic elements—including a scale bar, graticule (indicating latitude and longitude), and north arrow—are provided. Owing to the regional scale of this map and the spatial proximity of replicate plots within the same age class, their symbols may appear clustered. For detailed relative positioning, consult Figure S1 and the sampling design outlined in Section 2.2.

Within each plot, soil samples were collected using a quincunx sampling design (5 sampling points per plot). After removing surface litter, soil cores (10 cm in depth, 5 cm in inner diameter) were extracted using a soil auger and stored in labeled, sealed bags. Subsequently, the five soil cores from each plot were thoroughly mixed to form one composite sample per plot for all subsequent analyses, in order to obtain a representative average value. Samples were transported to the laboratory in dry ice-sealed containers for preservation.

Following the removal of roots and debris by manual sorting, all soil samples were homogenized by passing through a 2 mm stainless steel sieve and subsequently partitioned for specific analytical procedures. One portion was immediately stored at −80 °C for subsequent DNA extraction and microbial community sequencing. Another portion was extracted with 2 M KCl from fresh soil for mineral nitrogen (NH4+-N and NO3−-N) analysis, and the resulting extracts were frozen at −20 °C until further measurement. The remaining portion was air-dried at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) to constant weight, finely ground using a planetary ball mill, and passed through a 0.15 mm sieve for physicochemical characterization.

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Soil Physicochemical Characterization

The soil pH was determined using a pH meter equipped with a glass electrode (PHS-3C, INESA Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with a soil-to-water ratio of 5:1 (w/v) [34]. Soil total organic carbon (TOC) content was measured by the potassium dichromate-sulfuric acid oxidation method, potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) and concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) [35]. Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) was determined from 1:5 (w/v) soil-water extracts after shaking and centrifugation, followed by filtration through a 0.45-μm membrane filter (MilliporeSigma, Burlington, MA, USA), and quantified using a Multi N/C 3100 TOC analyzer (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany) [36]. ROC content was determined by the potassium permanganate oxidation method with KMnO4 reagent obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) [37]. TN concentration was measured using the Kjeldahl digestion method with Kjeldahl catalyst tablets (Foss Analytical AB, Höganäs, Sweden) and analyzed with a 2300 Kjeltec Analyzer Unit (Foss Analytical AB, Höganäs, Sweden) [38,39]. Hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN) was determined by alkali hydrolysis-diffusion method, where the ammonia released from soil samples treated with NaOH and boric acid (H3BO3) supplied by Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) [40]. NH4+-N and NO3−-N were extracted from fresh soil samples with 2mol·L−1 KCl solution (1:5, w/v ratio; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and measured using a continuous flow analyzer (Skalar Analytical B.V., Breda, The Netherlands [41]. Total phosphorus (TP) content was determined by the molybdenum-antimony spectrophotometric method with ammonium molybdate and antimony potassium tartrate (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) [42]. Available phosphorus (AP) was extracted using 0.5 mol·L−1 NaHCO3 (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and quantified using the molybdenum blue method [43].

2.3.2. Determination of Soil Microbial Biomass and Enzyme Activities

Soil microbial biomass was determined by the chloroform fumigation-extraction method [44]. Microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and nitrogen (MBN) were extracted with 0.5 M K2SO4 (analytical grade; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and measured by potassium dichromate oxidation (K2Cr2O7, Sinopharm, Shanghai, China) and Kjeldahl (FOSS Analytical AB, Hillerød, Denmark) digestion, respectively. Microbial biomass phosphorus (MBP) was extracted with 0.5 M NaHCO3 (Sinopharm, Shanghai, China) and determined by molybdenum blue colorimetry using ammonium molybdate reagents (Sinopharm, Shanghai, China). All microbial biomass values were calculated using appropriate conversion factors.

Soil enzyme activities were determined as follows. Sucrase (Suc) activity was measured using 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetry (DNS reagent; Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) with sucrose as substrate, incubating at 37 °C for 24 h and quantifying glucose production was quantified colorimetrically using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) [45]. Urease (Ur) activity was determined by indophenol blue colorimetry with urea as substrate after 24 h incubation at 37 °C, measuring ammonium nitrogen generation was determined via indophenol blue colorimetry using phenol and sodium hypochlorite reagents (Sinopharm, Shanghai, China [45]. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity was assayed using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP; Aladdin, Shanghai, China) as substrate at pH 11.0 and 37 °C for 1 h, quantifying p-nitrophenol production was quantified using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer [45]. Cellulase (CEL) activity was measured with carboxymethyl cellulose sodium (CMC-Na; Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) as substrate, incubating at 37 °C for 72 h and determining reducing sugars were measured using DNS colorimetry [45]. Catalase (CAT) activity was determined by KMnO4 titration, where potassium permanganate (Sinopharm, Shanghai, China) was used to quantify H2O2 decomposition after 15 min [45]. Polyphenol oxidase (PO) activity was assayed using pyrogallol substrate (Aladdin, Shanghai, China) after incubation at 37 °C for 2 h, and absorbance was measured via UV–Vis spectrophotometry [45]. β-1,4-glucosidase (βG) and cellobiohydrolase (CBH) activities were measured using p-nitrophenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (pNPG; Aladdin, Shanghai, China) as substrate, incubating at 37 °C for 1 h and quantifying p-nitrophenol production at 400 nm [46]. Acid phosphatase (ACP) activity was determined with p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP; Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) as substrate at pH 6.5 and 37 °C for 1 h, following the colorimetric quantification of released p-nitrophenol using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UV-2600, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) [46]. L-Leucine aminopeptidase (LAP) and N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG) activities were determined by fluorometric methods with L-leucine-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and 4-methylumbelliferyl-N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide (MUB-NAG; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) as substrates, respectively, incubated at 20 °C for 4 h, and fluorescence was quantified using a fluorescence microplate reader (Infinite M200 Pro, Tecan Group Ltd., Zürich, Switzerland) [47]. All enzyme activities were expressed as the amount of substrate converted or product formed per unit time per gram of soil (e.g., mg·g−1·d−1, μmol·g−1·d−1, μg·g−1·min−1 or μg·g−1·d−1).

2.3.3. Soil Microbial Sequencing Analysis

We entrusted Beijing Biomarker Technologies Corporation to perform the soil microbial sequencing analysis. The total DNA extraction from the samples was conducted using the DN easy Power Soil Kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Venlo, The Netherlands) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of the DNA was assessed, and quantification was performed using agarose gel electrophoresis alongside the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer and the NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The qPCR was used to measure the abundance of soil bacteria and fungi with primer set 338F/806R (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′; 5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′) and ITS4/ITS5 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′; 5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′), respectively. The reaction was performed using an ABI 7500 (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA). A plasmid DNA preparation was obtained from the clone using a Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). Standard curves were generated by amplifying serial dilutions of the target regions cloned into plasmids, with amplification efficiencies ranging from 91 to 100% and R2 values > 0.99. Each of the 25 mL reaction mixture contained 12.5 mL SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (TakaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China), 0.5 mL of each primer (10 mM), and 1–10 ng of template DNA. The PCR condition was as follows: 3 min at 95 °C, 35 cycles of 40 s at 95 °C, 30 s at 54 °C, 40 s at 72 °C, and final extension step of 83 °C for 10 s. The qPCR assay was run in triplicate for each replicate, and amplification specificity was assessed using melt curve analysis.

Alpha and beta diversity analyses of soil microbial communities were performed based on the high-throughput sequencing data. Alpha diversity, reflecting the complexity within each sample, was assessed using four indices: the Chao1 and ACE indices (estimating species richness), and the Shannon and Simpson indices (estimating community diversity and evenness). Beta diversity, which reflects the compositional differences between samples, was analyzed using Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices. The stability and reliability of the NMDS ordinations were evaluated using stress values. These analyses were conducted using the vegan package (version 2.6–6) in R.

2.4. Data Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Treevolume Calculation

The individual tree volume of Chinese fir was calculated using a two-variable empirical volume equation (formula). Within the pure Chinese fir sample plots, each tree’s height was measured [48].

where VC represents the individual tree volume (m3), D denotes the diameter at breast height (DBH, cm), and H indicates the total tree height (m).

2.4.2. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (v4.3.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test (p < 0.05) was used to examine differences in tree growth, soil properties, and microbial biomass across stand age classes, following verification of normality and homogeneity of variances. Multivariate analyses included principal component analysis (PCA; FactoMineR v2.6) to identify major soil nutrient gradients, non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS; vegan v2.6–6) based on Bray–Curtis distances to visualize microbial community composition, and permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA; 999 permutations) to test for significant differences in community structure. Based on existing literature and preliminary research findings, the growth of Cunninghamia lanceolata is regulated by the combined effects of soil properties, enzyme activities, and microbial communities [49,50]. To systematically analyze the integrated pathways through which these factors influence stand productivity, this study employed partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), implemented using the “plspm” package (v0.5.1) on the R platform for model construction and path analysis. Model validity was evaluated according to established criteria [51], where average variance extracted (AVE) > 0.5 indicated convergent validity, composite reliability (CR) > 0.7 reflected internal consistency, and R2 values represented predictive accuracy. Graphical figures were generated using Origin 2018 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) and Adobe Illustrator 2023 (Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Growth Characteristics of Chinese Fir Plantations with Different Stand Ages

The growth parameters of C. lanceolata plantations showed significant variation along the developmental chronosequence (Table 1). Mean tree volume (MTV) exhibited a consistent increasing trend with stand age, reaching its peak value of 0.115 ± 0.028 m3 in the mature stands (30 years). In contrast, the mean annual increment (MAI) displayed a divergent, non-monotonic pattern. It reached a peak value of 0.84 ± 0.19 m3·year−1 in mid-aged stands (15 years), marking a significant increase over that in young stands (5 years). This peak was followed by a substantial decline in near-mature stands (20 years), where the MAI dropped to less than half of the maximum value, albeit this decrease was not statistically significant. Subsequently, MAI demonstrated a partial recovery in mature stands (30 years).

Table 1.

Growth characteristics of monoculture Chinese Fir plantations.

Morphological traits, including DBH and tree height, increased markedly from the young to mid-aged stages (5 to 15 years), with mean DBH showing an approximate 185% increase. No significant further diameter growth was observed beyond this stage. Tree height reached 8.5 ± 0.5 m in mid-aged stands, followed by a slow increase to 11.1 ± 1.5 m in mature stands (30 years), revealing characteristic asymptotic growth patterns typical of even-aged monocultures (p < 0.05).

3.2. Characteristics of Soil Nutrients and Microbial Biomass in Chinese Fir Plantations of Different Stand Ages

Soil nutrient characteristics in Chinese fir plantations exhibited significant stage-specific variations along the chronosequence (Table 2). While soil pH and AP concentration remained stable throughout stand development, OC, DOC, ROC, and NO3−-N concentrations followed a unimodal trend, peaking in near-mature stands. In contrast, TN, NH4+-N, HN, and TP concentrations increased significantly with stand age (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

Soil Properties of Monoculture Chinese Fir Plantations.

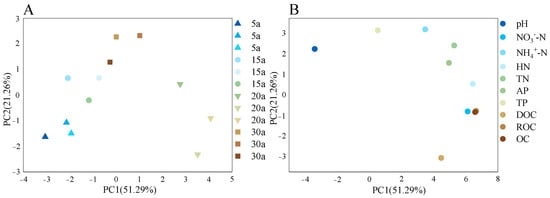

PCA revealed clear differentiation in soil physicochemical properties across the forest chronosequence (Figure 2). Soils in near-mature and mature stands exhibited distinct characteristics from younger stands, with significantly higher contents of NH4+-N, HN, TN, and TP (Table 2). Young stands were strongly associated with higher pH and available phosphorus (AP) levels, whereas near-mature stands showed close correlations with NO3−-N, readily oxidizable carbon (ROC), and organic carbon (OC). The PCA further indicated that PC1 was primarily driven by carbon and nitrogen cycling parameters (OC, ROC, NO3−-N), while PC2 reflected gradients in pH and AP (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

PCA of soil nutrients in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of soil nutrients across the stand age chronosequence. (A) PCA ordination plot showing the distribution of soil samples from different stand ages (5a, 15a, 20a, 30a). Ellipses represent confidence intervals for each age group. (B) Variable contribution (loading) plot for the same PCA, showing the direction and strength of contribution of each soil nutrient variable to the principal components. Points represent individual samples, with shapes denoting different stand types (triangle = 5a (5 years), circle = 15a (15 years), inverted triangle = 20a (20 years), square = 30a (30 years)). The axes correspond to the first two principal components, with the first principal component (PC1) explaining 51.29% of the variance and the second principal component (PC2) contributing 21.26%. Together, they account for 72.55% of the heterogeneity in the soil environment. The separation of samples along PC1 indicates significant differences in soil nutrient levels across forest stands of different ages (n = 36, p < 0.05).

Soil microbial biomass in Chinese fir plantations exhibited significant age-dependent dynamics (Table 3). MBC followed a unimodal pattern, increasing initially and then decreasing during stand development, with a peak value of 487.33 ± 22.09 mg·kg−1 in near-mature stands—significantly higher than in other stages. By the mature stage, MBC declined to 374.50 ± 0.29 mg·kg−1, yet remained 1.71- and 1.76-fold higher than in young and mid-aged stands, respectively. MBN showed a non-significant increasing trend from young (32.90 ± 6.00 mg·kg−1) to near-mature stands (60.00 ± 5.10 mg·kg−1), before decreasing to its lowest level in mature stands (39.49 ± 7.57 mg·kg−1). In contrast, MBP mirrored the trend of MBC, rising significantly from young (9.52 ± 2.85 mg·kg−1) to near-mature stands (25.65 ± 2.81 mg·kg−1), then declining slightly in mature stands (21.19 ± 4.13 mg·kg−1). Mid-aged stands exhibited intermediate MBP levels (18.02 ± 0.97 mg·kg−1; p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Soil microbial biomass of monoculture Chinese Fir plantations.

3.3. Soil Microbial Community Characteristics Shift with Stand Age in Chinese Fir Plantations

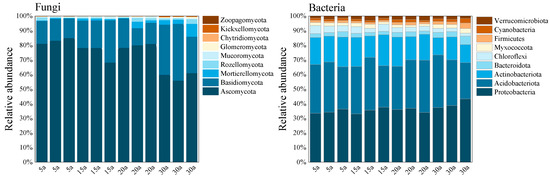

3.3.1. Dominant Soil Microbial Abundance at Phylum Levels Across Different Stand Ages

Figure 3 shows that Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, and Mucoromycota were the dominant fungal phyla (relative abundance > 5%) in C. lanceolata plantation soils. Ascomycota was the predominant phylum across all stand ages, with relative abundances exceeding 80.0%, while Basidiomycota also maintained high abundance levels, particularly in mature stands where it reached approximately 20.0%. With stand development, the relative abundance of Ascomycota decreased significantly, whereas those of Basidiomycota and Mucoromycota increased markedly.

Figure 3.

Relative abundance of soil microbes at the phylum level in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. The figure illustrates the relative abundance of different microbial taxa in soil samples. The left panel displays the fungal community, while the right panel shows the bacterial community, both comprising nine phylum-level taxonomic units. The height of the bars represents the mean relative abundance of each microbial taxon (5a: 5 years, 15a: 15 years, 20a: 20 years, 30a: 30 years; n = 36, p < 0.05).

Among bacterial communities, the dominant phyla were Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes. Proteobacteria dominated across all stand ages, with relative abundances exceeding 40.0%, while Acidobacteria also showed high abundance, reaching nearly 30.0% in mature stands. During stand development, the abundance of Actinobacteria decreased significantly, while that of Bacteroidetes increased. In contrast, the relative abundances of Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria remained stable throughout the chronosequence (p < 0.05).

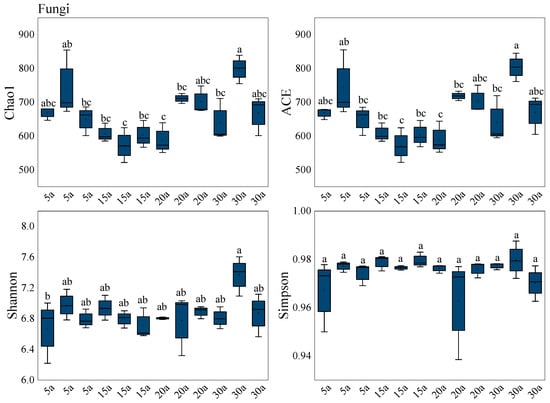

3.3.2. Variation in Soil Microbial Diversity with Different Stand Ages

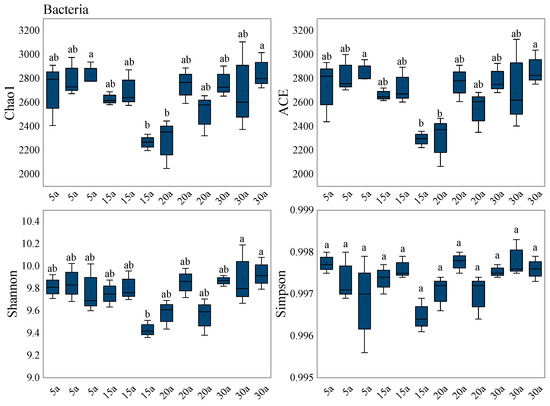

Soil fungal α-diversity indices exhibited significant age-related dynamics across the forest chronosequence (Figure 4). The Chao1 and ACE indices, reflecting species richness, followed an N-shaped trajectory with significantly higher values in mature stands than in younger or older developmental stages. The Shannon index, indicative of community diversity, showed a progressive increase and peaked in mature stands. In contrast, the Simpson index demonstrated no significant variation along the successional gradient. Collectively, these results indicate a significant increase in soil fungal α-diversity with stand development (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Alpha diversity of the soil fungal community in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. Box plots show the diversity indices of fungal microbial community structures across different forest stands. The center line within the box indicates the median, the box boundaries represent the interquartile range (IQR), and the error bars extending above the box indicate the standard error (SE). The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5× IQR. Solid points inside the box represent the mean values. Different lowercase letters above the boxes indicate significant differences between treatments based on Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). The sample size for each treatment group is n = 36. Stand age abbreviations: 5a (5 years), 15a (15 years), 20a (20 years), 30a (30 years).

With increasing stand age, soil bacterial alpha diversity—as indicated by the Chao1, ACE, and Shannon indices—displayed a consistent U-shaped trend (Figure 5), with all metrics peaking in mature stands. At this stage, bacterial species richness, community diversity, and evenness reached their maximum values. In contrast, the Simpson index showed no significant differences among stand ages. Overall, soil bacterial alpha diversity was lowest in mid-aged stands (p < 0.05).

Figure 5.

Alpha diversity of the soil bacterial community in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. Box plots show the diversity indices of bacterial microbial community structures across different forest stands. The center line within the box indicates the median, the box boundaries represent the interquartile range (IQR), and the error bars extending above the box indicate the standard error (SE). The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points within 1.5× IQR. Solid points inside the box represent the mean values. Different lowercase letters above the boxes indicate significant differences between treatments based on Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05). The sample size for each treatment group is n = 36. Stand age abbreviations: 5a (5 years), 15a (15 years), 20a (20 years), 30a (30 years).

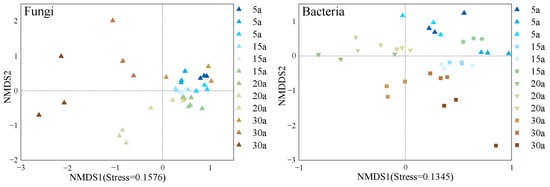

Non-metric multidimensional scaling (NMDS; Figure 6) based on Bray–Curtis distances revealed successional shifts in soil fungal and bacterial β-diversity across the chronosequence. Fungal communities in young stands formed a tight cluster, while those in mid-aged, near-mature, and mature stands exhibited a gradient-like distribution along the successional axis, with mature stands assembling into a distinct group, suggesting the development of a unique community structure. In contrast, bacterial communities showed partial overlap between young and near-mature stands, while near-mature and mature stands formed relatively discrete clusters. This pattern indicates that bacterial succession proceeds through distinct stages, with a notable transition occurring between mid-aged and near-mature stands. Stress values below 0.2 confirmed the reliability of the two-dimensional ordination. The significantly higher stress value for fungal communities reflects their greater structural complexity compared to bacterial communities.

Figure 6.

Beta diversity of the soil microbial community in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. The NMDS ordination displays β-diversity patterns of fungal and bacterial communities. Stress values (0.1576 for fungi and 0.1345 for bacteria, both < 0.2) indicate highly reliable ordination results. Points represent individual samples colored by different forest stands (see legend). Axes show unitless ordination coordinates where positive/negative values indicate relative positions in the reduced dimensional space. Stand age abbreviations: 5a (5 years), 15a (15 years), 20a (20 years), 30a (30 years).

3.4. Variation Characteristics of Soil Enzyme Activities in Chinese Fir Plantations with Different Stand Ages

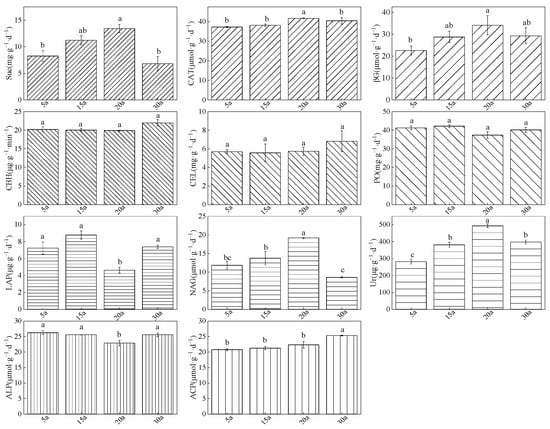

Soil enzyme activities, recognized as key indicators of soil nutrient cycling and fertility, exhibited significant age-dependent dynamics in Chinese fir plantations (Figure 7). For C-cycling enzymes, the activities of Suc, CAT, and βG showed a unimodal pattern across stand development, peaking significantly in mid-aged stands. In contrast, the activities of CBG, CEL, and PO remained relatively stable throughout all stand ages. Regarding N-cycling enzymes, both NAG and Ur activities also followed a unimodal trend, with maximal values observed in mid-aged stands. Conversely, LAP activity displayed a U-shaped pattern, reaching its lowest point in mid-aged stands. For P-cycling enzymes, ALP activity exhibited a U-shaped trend, with significantly reduced activity in mid-aged stands. ACP activity, however, demonstrated a generally increasing pattern, attaining its highest level in mature stands. Collectively, soil enzymes associated with C and N cycling generally increased during stand development, whereas P-cycling enzymes showed less consistent variation patterns (p < 0.05).

Figure 7.

Soil enzyme activities (with respective standard units) across a chronosequence of Chinese fir plantations. Bar charts show the results of soil enzyme activities across different forest stands (y-axis: enzyme activity unit). Error bars represent the standard error (n = 36). Different lowercase letters above the bars indicate significant differences between groups based on Tukey’s HSD test (p < 0.05), with the same letters indicating no significant difference. Stand age abbreviations: 5a (5 years), 15a (15 years), 20a (20 years), 30a (30 years). Abbreviations: Suc, Sucrase; CAT, Catalase; βG, β-Glucosidase; CBH, Cellobiohydrolase; CEL, Cellulase; PO, Polyphenol Oxidase; LAP, Leucine Aminopeptidase; NAG, N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase; Ur, Urease; ALP, Alkaline Phosphatase; ACP, Acid Phosphatase.

3.5. Drivers of Productivity: Linking Soil Nutrients, Microbial Communities, and Enzyme Activities

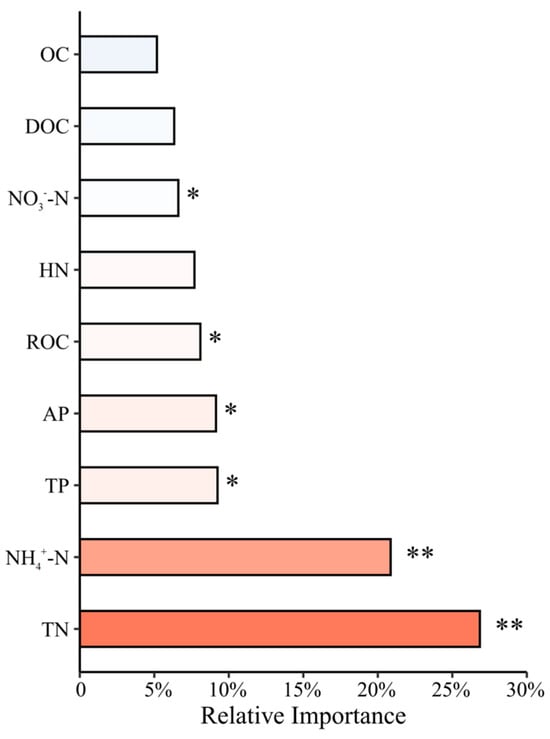

Random forest analysis (Figure 8) indicated that soil nutrient indicators—including TN, NH4+-N, TP, AP, and ROC—significantly promoted stand productivity accumulation, whereas NO3−-N exhibited a significant suppressive effect. These findings align with the results from the principal component analysis of soil nutrients. Furthermore, stands with higher concentrations of hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN), NH4+-N, and TN—particularly in near-mature and mature stands—showed correspondingly increased productivity (p < 0.05).

Figure 8.

Random Forest modeling of the impact of soil nutrients on stand productivity in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. The x-axis represents the relative importance of each predictor (0%–30%), and the analysis is based on n = 36 observations. Asterisks indicate levels of statistical significance for predictor–productivity relationships: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

3.6. Mechanism of Nutrient Cycling Impact on Stand Productivity in Chinese Fir Plantations

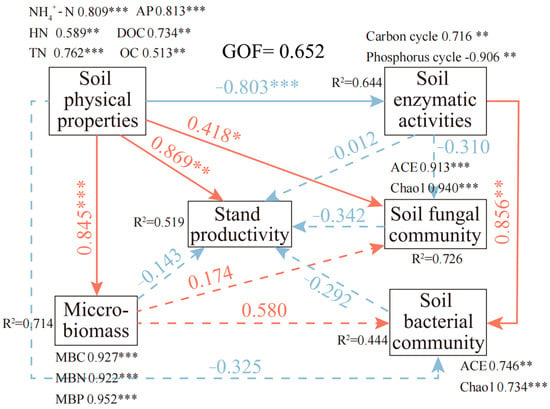

This study employed partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to elucidate the multi-factor mechanisms driving productivity in North Subtropical Chinese fir plantations (Figure 9). The PLS-SEM analysis revealed a complex “double-edged sword” effect of soil nutrients on stand productivity. While soil physicochemical properties exerted a strong direct positive effect on productivity (β = 0.869), they also induced a significant competitive inhibitory effect by stimulating microbial activity. Specifically, soil nutrient enrichment substantially increased microbial biomass (β = 0.845) and promoted the diversity of fungal and bacterial communities (explaining approximately 58.0% and 41.8% of the variance in these communities, respectively). However, these enhanced microbial communities likely competed with trees for nutrients, thereby suppressing productivity (β = −0.143). Concurrently, soil nutrients were associated with reduced soil enzyme activity (β = −0.803). With increasing stand age, the activity of carbon-cycle-related enzymes strengthened, while that of phosphorus-cycle-related enzymes weakened. This enzymatic inhibition subsequently diminished fungal community structure, fostering richer bacterial and fungal assemblages, which in turn further negatively impacted productivity through competition (β = −0.292 and β = −0.342, respectively). Ultimately, stand productivity reflects the net outcome of a trade-off between the direct promotional effect of nutrients and the microbe-mediated indirect inhibition (p < 0.01).

Figure 9.

PLS-SEM path diagram illustrating the effects of soil physicochemical properties, soil microorganisms, microbial community structure, and enzyme activities on stand productivity. The model quantifies both direct and indirect pathways linking soil properties (latent variable), fungal community structure (α- and β-diversity), bacterial community structure (α- and β-diversity), microbial biomass, and enzyme activities to stand productivity (latent variable). Standardized path coefficients are shown along arrows, with asterisks indicating statistical significance (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001). The model exhibits strong explanatory power, with a GOF index of 0.652 (exceeding the threshold of 0.36 for a large effect). Values adjacent to latent variables represent the proportion of variance explained (R2) in endogenous variables.

4. Discussion

Our results reinforce the premise outlined in the Introduction that soil nutrients strongly regulate stand productivity, but they further demonstrate that this relationship is inherently dynamic. Along the chronosequence, productivity shifts were shaped not only by changes in nutrient availability but also by transitions in nutrient limitation—from nitrogen sufficiency in young stands to pronounced phosphorus limitation in mature stands—and by corresponding adjustments in microbial nutrient demand. These coupled soil–microbe feedbacks, rather than nutrient pools alone, provide a mechanistic explanation for the observed decline in productivity during stand development.

4.1. Stage-Dependent Growth Dynamics and Productivity Responses of Chinese Fir Plantations to Stand Age Growth

Our study demonstrates nonlinear growth dynamics in Chinese fir plantations along a stand-age gradient, reflecting ecosystem-level adjustments in resource allocation. The observed growth stagnation and decline in productivity in near-mature stands represent a manifestation of a broader phenomenon common to intensively managed monoculture systems. Similar nonlinear growth patterns have been reported in successive rotations of various plantation species, including Eucalyptus spp. [52] and Pinus massoniana [53], although the underlying mechanisms may differ among ecological contexts.

From young to mid-aged stands, both stand-level and individual tree volume increased rapidly, driven primarily by substantial gains in DBH and tree height. This high-productivity phase likely reflects greater resource-use efficiency in younger stands, where lower stand density reduces intraspecific competition and thereby enhances the capture of both light and soil nutrients [54,55]. Thereafter, growth rates progressively decelerated in near-mature stands (20 years), a transition attributable to multiple interacting factors. These include intensified resource competition associated with canopy closure, which restricts light availability, and increasingly overlapping root systems that intensify belowground competition for nutrients [56]. At the same time, peak MBC and MBP indicate strong microbial nutrient immobilization—despite relatively high soil nitrogen (NH4+-N) and phosphorus (TP) levels—thereby exacerbating plant–microbe competition for limiting resources [57]. Additionally, the concurrent decline in soil pH to its minimum likely impairs rhizosphere processes and further constrains nutrient acquisition [58,59].

It should be noted that the growth dynamics identified in this study, based on a space-for-time substitution approach, reflect the combined influence of stand age and site-specific conditions. Productivity in Chinese fir plantations is co-regulated by stand structural attributes (e.g., DBH and tree height) and soil nutrient availability. Our integrative analysis suggests that growth deceleration in near-mature stands is not driven solely by absolute nutrient stocks, but more critically reflects a strategic shift at the ecosystem level. This transition is characterized by intensified plant–microbe competition and a shift from rapid, “resource-driven” growth towards a more conservative strategy under emerging nutrient-limited conditions. Furthermore, the limited number of replicate plots may have constrained the statistical power to detect more subtle differences in growth-related parameters.

4.2. Driving Mechanisms of Soil Nutrient Availability Across Stand-Age Gradients

Within the carbon cycle, TOC exhibited a distinct bimodal pattern—a phenomenon also reported in chronosequence studies of Larix principis-rupprechtii plantations [60]. The initial TOC peak in near-mature stands appears to arise from increased litter inputs and improved substrate quality (e.g., lower C/N ratios) [61], which, in combination with elevated β-glucosidase (βG) activity, enhanced the accumulation of labile carbon [62,63]. A secondary TOC peak in mature stands reflects a fundamental shift toward more recalcitrant carbon pools. With increasing stand age, the sustained input of lignin-rich litter stimulated phenol oxidase (PO) activity [64], promoting the conversion of labile carbon into more stable aromatic forms [65]. Concurrently, the decline in the microbial biomass carbon (MBC) to TOC ratio indicates increasing microbial carbon-use efficiency and a shift toward a “slow-cycling” carbon sequestration strategy [66,67], a trend consistent with global patterns in aging forests [68].

Nitrogen cycling was regulated by multiple interacting biological processes. The notable accumulation of nitrate (NO3−-N) in near-mature stands likely resulted from coordinated mechanisms, including (1) increased Basidiomycota abundance that stimulated manganese peroxidase production and facilitated the breakdown of nitrogen-rich macromolecules [69]; (2) enhanced organic nitrogen mineralization associated with higher acid phosphatase-to-urease ratios [70]; and (3) rhizospheric pH gradients that supported coupled nitrification–denitrification pathways [71]. Such multi-tiered regulation is characteristic of plantation ecosystems, although the specific microbial taxa involved may differ across regions and species [72].

Phosphorus (P) dynamics reflected a balance between geochemical constraints and microbial competition. While total phosphorus (TP) increased with stand age, available phosphorus (AP) remained relatively stable. This decoupling is primarily attributable to two factors: acidification-driven phosphate adsorption onto Fe/Al oxides [73], and increased microbial phosphorus immobilization (MBP as a proportion of TP). The strong positive correlation between acid phosphatase (ACP) activity and Basidiomycota abundance supports a key role of fungi in organic P mineralization [74]. Such fungus–enzyme synergies are critical for mobilizing recalcitrant P pools, thereby influencing nutrient acquisition in these P-limited soils [75], and align with the well-documented P limitation across subtropical forest plantations [76].

Collectively, these biogeochemical patterns illustrate a clear shift in dominant nutrient limitation—from relative nitrogen sufficiency in young stands to pronounced phosphorus limitation in mature stands—a trajectory consistent with global forest development theory [77,78]. Young stands exhibit minimal nitrogen limitation due to greater nitrogen availability and low microbial phosphatase investment, whereas aging stands show intensified P fixation and reduced nitrogen transformation efficiency. Elevated ACP activity combined with reduced nitrate availability in mature stands provides strong evidence for progressive P limitation. Under short-rotation management, this constraint is likely to persist due to the slow replenishment of soil P pools and continuous removal of biomass with harvest.

4.3. Coordinated Succession of Soil Microbial Structure-Function and Shift in Ecological Strategies

Our investigation documents a systematic shift in ecological strategies within soil microbial communities across the developmental chronosequence of Chinese fir plantations. The observed transition from copiotrophic to oligotrophic microbial strategists indicates functional adaptation through coordinated restructuring of community composition and biomass allocation patterns [79]. This strategic reorganization contributes fundamentally to ecosystem stability and highlights mechanistic linkages between microbial succession and coupled carbon–phosphorus cycling. Fungal communities exhibited clear successional patterns, with Ascomycota—characteristic r-strategists—dominating young stands through the utilization of labile organic substrates [80], but showing a marked decline in relative abundance as stands matured. Conversely, Basidiomycota and Mucoromycota increased progressively in relative abundance. Basidiomycota in particular displayed competitive superiority in later developmental stages through enhanced lignin-degrading capacity, facilitating the decomposition of recalcitrant substrates, including lignified litter [81].

Parallel examination of bacterial communities revealed analogous ecological strategy differentiation. Proteobacteria predominated in young stands (>40%), closely associated with elevated root exudation and the availability of easily metabolizable carbon sources [27,82]. In contrast, mature stands showed increased Acidobacteria abundance (approximately 30%), indicating adaptation to oligotrophic and acidic conditions, whereas Actinobacteria declined—likely reflecting their preference for near-neutral pH and the progressive impacts of soil acidification.

Microbial α-diversity exhibited divergent temporal patterns between fungi and bacteria. Fungal richness and diversity (Chao1 and Shannon indices) reached their highest values in mature stands, coinciding with increased heterogeneity of carbon substrates derived from accumulated litter [81]. In contrast, bacterial diversity reached its minimum in mid-aged stands, potentially reflecting intense nutrient competition during this transitional phase—a pattern previously reported in Pinus armandii plantations [83]. NMDS ordination further distinguished community assembly dynamics, with fungal communities exhibiting relatively continuous successional trajectories, whereas bacterial assemblages showed more discrete compositional shifts, suggesting stronger environmental filtering of bacterial communities along pH and nutrient gradients [84].

MBC and MBP attained their maximum values in near-mature stands, reflecting integrated responses to shifts in litter quality, changing nutrient limitations, and recalibrated ecological strategies. Increasing litter lignification stimulated microbial decomposition activity [85], while intensifying phosphorus limitation promoted microbial P storage in biomass, as reflected by higher MBP [86].

A comprehensive understanding of microbial functioning requires consideration within a broader belowground trophic framework. While microorganisms mediate core nutrient transformations, soil fauna exert critical top-down control through trophic cascades. Bacterivorous and fungivorous nematodes modify microbial community structure via selective predation, thereby accelerating nitrogen and phosphorus mineralization from microbial biomass [87,88,89]. Simultaneously, faunal excretory products (e.g., ammonium released by nematodes) directly augment bioavailable nutrient pools [90,91]. These faunal-mediated processes become particularly important in older stands experiencing intensified phosphorus limitation, where mobilization of recalcitrant organic phosphorus depends strongly on multitrophic interactions [92,93,94], representing a conserved mechanism for maintaining nutrient cycling in aging forests across biogeographic regions.

Consequently, the observed relationships among microbial communities, enzymatic activities, and ecosystem functions are likely embedded within complex multitrophic networks. Future research that explicitly incorporates soil fauna dynamics will be essential to fully elucidate the mechanisms governing the long-term sustainability of nutrient cycling in plantation ecosystems.

4.4. Enzyme Activity Dynamics Reveal Nutrient Cycling Strategies of the Plantations

Our study demonstrates pronounced shifts in soil enzyme activities along a chronosequence of Chinese fir plantations, reflecting adaptive resource-acquisition strategies employed by microbial communities in response to changing nutrient demands during stand development. These enzymatic responses are consistent with broader patterns reported for plantation ecosystems, where microbial communities reorganize metabolic investments to cope with stage-specific nutrient limitations [95].

The activities of carbon cycle-related enzymes (Suc and βG) and nitrogen cycle-related enzymes (Ur and NAG) showed unimodal patterns, peaking in near-mature stands (20 years) and subsequently declining. This trajectory corresponds closely to shifts in microbial metabolic demand. From young to mid-aged stands, abundant inputs of readily decomposable organic matter stimulated rapid microbial acquisition of carbon and nitrogen [96]. With further stand development, progressive litter lignification promoted a shift towards more specialized degradation pathways [81], leading to reduced investment in these C- and N-acquiring enzymes. The close synchrony between urease activity and soil nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) content underscores the ecological significance of microbially mediated nitrogen mineralization during the near-mature stage, whereas the significant negative correlation between urease activity and ammonium nitrogen (NH4+-N) reflects underlying patterns of nitrogen availability.

Phosphorus-acquiring enzymes exhibited distinct developmental dynamics. Acid phosphatase (ACP) activity increased steadily with stand age, reaching its maximum in mature stands (30 years). This pattern contrasts with increasing total soil phosphorus but relatively stable available phosphorus (AP), indicating progressively intensified constraints on phosphorus bioavailability during stand development [15]. The marked increase in microbial phosphatase production represents a community-level response to phosphorus stress, potentially alleviating P limitation in Chinese fir by enhancing organic phosphorus mineralization [97]. In contrast, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity fluctuated without a clear directional trend. This functional differentiation likely arises from two primary factors: first, ACP is predominantly secreted by fungi and acid-adapted bacteria, whereas ALP is mainly of bacterial origin [98,99]; second, ACP-dominated inorganic phosphorus mineralization is more competitive under acidic soil conditions [100]. Although some studies have reported declining ACP activity in certain plantation systems, the consistent increase observed here is consistent with progressive phosphorus limitation and likely reflects microbial adaptation through strategic adjustment of phosphatase secretion under sustained P stress [101].

From a resource-allocation perspective, the observed enzyme activity patterns reflect trade-offs in microbial investment in carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus acquisition. The synchronous peak in C- and N-cycle enzyme activities during the near-mature stage suggests that microbial communities initially prioritize meeting fundamental energy and nitrogen requirements, whereas the subsequent sustained increase in ACP activity indicates a shift in investment towards phosphorus acquisition [18,102]. This successional pattern of microbial nutrient investment—transitioning from coupled carbon–nitrogen acquisition to predominant phosphorus acquisition—represents a fundamental ecological strategy in forest ecosystems experiencing progressively stronger nutrient limitations [93]. Random forest analysis corroborates this interpretation, showing a decline in the relative importance of nitrogen indicators (e.g., total nitrogen, NH4+-N) for productivity with increasing stand age, while phosphorus-related variables gained prominence. Together, these patterns illustrate how microbial communities optimize resource allocation in a changing environment through flexible regulation of their enzyme systems—a mechanism that likely contributes to the productivity declines observed in aging plantations worldwide [103].

4.5. Integrated Effects of Multi-Factor Interactions on Productivity Change

Based on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), this study elucidates the multifactorial synergistic mechanisms governing productivity formation in C. lanceolata plantations. The model reveals that stand age directly enhances productivity through improved soil physicochemical properties (β = 0.869) while simultaneously exerting indirect effects via microbial biomass regulation (β = 0.845). This dual pathway corresponds with the progressive accumulation of soil nutrients (e.g., organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus availability) during stand development [104]. The “dual-effect mechanism” describes how soil nutrients exert a strong direct positive influence on stand productivity while simultaneously generating indirect negative effects by stimulating microbial biomass accumulation, community restructuring, and intensified nutrient competition, ultimately producing a net outcome shaped by the balance between promotion and inhibition.

Microbial communities and enzyme activities demonstrated complex interactions: fungal diversity significantly suppressed extracellular enzyme activity (β = −0.310), whereas bacterial communities enhanced it (β = 0.856). This functional antagonism reflects fundamental ecological strategy differences between these taxonomic groups. Fungi, particularly white-rot basidiomycetes, preferentially decompose complex organic matter through non-enzymatic oxidative pathways, thereby reducing their dependence on extracellular enzyme systems [105,106]. In contrast, bacteria predominantly rely on enzymatic hydrolysis for nutrient acquisition, resulting in positive regulation of enzyme production. Microbial functional groups therefore exert distinct influences on plantation productivity. The negative effect of fungal communities (β = −0.342) likely stems from their competition with plants for phosphorus. In mature stands, elevated fungal biomass coincided with increased acid phosphatase activity (Figure 6), indicating intensified microbial–plant competition for limited phosphorus resources. Conversely, the positive effect of bacterial communities (β = 0.292) is associated with their central role in nitrogen cycling; specifically, Proteobacteria enhance nitrogen availability through regulation of nitrification–denitrification pathways, thereby supporting plant growth [107]. This “push–pull” regulatory mechanism—where fungi suppress phosphorus-related enzymatic processes while bacteria promote nitrogen cycling—enables dynamic adjustment of nutrient supply to match C. lanceolata growth demands across stand developmental stages. The intensified plant–microbe competition for phosphorus, combined with the transition toward phosphorus limitation, provides a mechanistic explanation for the observed growth slowdown in near-mature stands.

Building on these mechanistic insights, we propose targeted nutrient management strategies to alleviate growth limitations during critical developmental stages. Precision application of bio-enzyme-activated phosphorus fertilizers during periods of declining growth could enhance soil available phosphorus and modulate microbial community composition (e.g., by promoting Acidobacteria dominance), thereby improving phosphorus-use efficiency [108,109]. Concurrent supplementation with nitrogen fertilizers and organic amendments (e.g., via litter management) would synergistically enhance bacterial activity and enzyme functioning, mitigating the limitations associated with single-nutrient applications.

Our study represents the first integrated multi-scale analysis conducted in Chinese fir plantations, quantitatively resolving cascading effects within the soil–microbe–enzyme continuum. The elucidated mechanisms not only clarify stand age–related successional patterns but also establish a theoretical foundation for targeted management strategies aimed at enhancing stand productivity and promoting sustainable silviculture. The synergy and antagonism within microbial communities collectively sustain long-term productivity in Chinese fir plantations, underscoring the central role of belowground processes in forest management [110].

4.6. Limitations and Future Perspectives

This study provides valuable insights into plant–soil–microbe interactions in Chinese fir plantations; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. The space-for-time chronosequence approach assumes comparable initial site conditions across stand ages, and potential legacy effects may have influenced the observed successional patterns. Sampling was restricted to the topsoil (0–10 cm) and a single time point, which limits inference regarding deeper soil layers and seasonal dynamics. In addition, replication within a single geographic region constrains the statistical robustness and generality of the findings.

Moreover, although the PLS-SEM revealed clear structural relationships among soil properties, microbial attributes, enzyme activities, and productivity, these results should be interpreted with caution given the relatively small number of observational units. Such sample sizes may reduce the stability of parameter estimates and increase the uncertainty associated with strong path coefficients; therefore, the inferred causal pathways should be regarded as indicative rather than definitive.

Several biological components were not explicitly quantified, including mycorrhizal associations that are critical for phosphorus acquisition and soil fauna that regulate nutrient cycling through trophic interactions. As a consequence, interpretations of microbial ecological strategies remain largely correlative and would benefit from functional validation using metatranscriptomic approaches or targeted enzyme assays.

Future research should incorporate longitudinal monitoring, multi-season sampling, and deeper soil profiling to improve temporal and spatial resolution. Broader geographic replication, together with the integration of mycorrhizal colonization assessments, soil fauna analyses, and multi-omics tools, would further strengthen mechanistic understanding of belowground processes that govern long-term productivity in Chinese fir plantations.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a conceptual model of the synergistic mechanisms operating within the “soil–microbe–enzyme” system, offering systematic insights into the sustainable management of Chinese fir plantation ecosystems. In contrast to previous studies that focused on individual components, our research integrates multiple belowground compartments to uncover key mechanisms driving productivity dynamics. The principal findings are as follows:

- (1)

- A belowground ecological strategy transition occurs during stand development: stand growth shifts from a resource-acquisition strategy to a nutrient-conservation strategy. This transition is closely associated with a shift from nitrogen to phosphorus limitation and concurrent microbial succession.

- (2)

- Microbial succession provides potential indicators: directional successional patterns in fungal and bacterial communities offer potential biomarkers for assessing ecosystem developmental status.

- (3)

- Enzyme activity acts as an early-warning signal: the sustained increase in phosphorus-cycle enzyme activity precedes detectable changes in soil available phosphorus, and thus may serve as an early-warning indicator of phosphorus limitation.

- (4)

- Productivity is regulated by a multi-pathway network: soil properties govern productivity through a complex network involving both direct effects and indirect pathways mediated by microbial communities and enzyme activities.

The integrative framework established here elucidates a mechanism through which belowground ecological processes sustain long-term productivity, providing a crucial theoretical basis for the sustainable management of global plantation ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16121854/s1. Figure S1. Spatial distribution of long-term forest monitoring plots representing four stand development stages (5, 15, 20, and 30 years) within the study area. Figure S2. Network correlation heatmap of soil nutrients and microbial community structure in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. Figure S3. Redundancy analysis of soil physicochemical properties and microbial community composition in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. Figure S4. Redundancy analysis of soil enzyme activities and microbial community composition in monoculture Chinese fir plantations. Figure S5. Conceptual representation of the dual-effect mechanism by which soil nutrients regulate stand productivity in Chinese fir plantations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, H.S. and L.W.; Data curation, H.S. and L.W.; Writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; Writing—review and editing, L.W., H.S., J.Z. and L.D.; Visualization, L.W.; Supervision, H.S. and J.Z.; project administration, Funding acquisition, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the National Key Technologies Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2021YFD2201303-03).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5a | 5-year-old |

| 10a | 10-year-old |

| 20a | 20-year-old |

| 30a | 30-year-old |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling |

| SOC | Soil organic carbon |

| Mean vol. | Mean volume per tree |

| MAI | Mean annual increment |

| DBH | Diameter at breast height |

| ha | Hectare |

| C | Carbon |

| N | Nitrogen |

| P | Phosphorus |

| NO3−-N | Nitrate Nitrogen |

| NH4+-N | Ammonium Nitrogen |

| HN | Hydrolyzable Nitrogen |

| TN | Total Nitrogen |

| AP | Available Phosphorus |

| TP | Total Phosphorus |

| DOC | Dissolved Organic Carbon |

| ROC | Readily Oxidizable Carbon |

| MBC | Microbial Biomass Carbon |

| MBN | Microbial Biomass Nitrogen |

| MBP | Microbial Biomass Phosphorus |

| Suc | Sucrase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| βG | β-Glucosidase |

| CBH | Cellobiohydrolase |

| CEL | Cellulase |

| PO | Phenol Oxidase |

| LAP | Leucine Aminopeptidase |

| NAG | N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase |

| Ur | Urease |

| ALP | Alkaline Phosphatase |

| ACP | Acid Phosphatase |

| NMDS | Non-metric multidimensional scaling |

References

- Michaletz, S.T.; Cheng, D.; Kerkhoff, A.J.; Enquist, B.J. Convergence of terrestrial plant production across global climate gradients. Nature 2014, 512, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doelman, J.C.; Stehfest, E.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Tabeau, A.; Hof, A.F.; Braakhekke, M.C.; Gernaat, D.E.; van den Berg, M.; van Zeist, W.J.; Daioglou, V. Afforestation for climate change mitigation: Potentials, risks and trade-offs. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 1576–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Ma, Q.; Marsden, K.A.; Chadwick, D.R.; Luo, Y.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wu, L.; Jones, D.L. Microbial community succession in soil is mainly driven by carbon and nitrogen contents rather than phosphorus and sulphur contents. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2023, 180, 109019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, S.; Duraisamy, V.; Huang, Z.; Guo, F.; Ma, X. Influence of long-term successive rotations and stand age of Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) plantations on soil properties. Geoderma 2017, 306, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Deng, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, J.; Meng, F.; Zuo, X.; Wu, L.; Cao, G.; Cao, S. Variations of rhizosphere and bulk soil microbial community in successive planting of Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata). Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 954777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Ge, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Huang, H.; Tong, Z.; Zhang, J. Forest conversion from pure to mixed Cunninghamia lanceolata plantations enhances soil multifunctionality, stochastic processes, and stability of bacterial networks in subtropical southern China. Plant Soil 2023, 488, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zeng, D.H.; Wang, G.; Li, X.; Lin, G. Shifts in soil nitrogen availability and associated microbial drivers during stand development of Mongolian pine plantations. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3156–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Guo, L.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, L. Drought and salinization stress induced by stand development alters mineral element cycling in a larch plantation. J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2020JG005906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Xiang, W.; Ouyang, S.; Wu, H.; Xia, Q.; Ma, J.; Zeng, Y.; Lei, P.; Xiao, W.; Li, S. Tight coupling of fungal community composition with soil quality in a Chinese fir plantation chronosequence. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 1164–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shao, Q.; Dan, Q.; Xu, Y.; Chen, X.; Dang, P. Soil nutrients, enzyme activities, and microbial communities along a chronosequence of Chinese fir plantations in subtropical China. Plants 2023, 12, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Dong, L.; Liu, Z. Stand structure is more important for forest productivity stability than tree, understory plant and soil biota species diversity. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1354508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Ye, S.; Liu, H.; Deng, X.; He, P.; Cheng, F. Linkage between Leaf–Litter–Soil, Microbial Resource Limitation, and Carbon-Use Efficiency in Successive Chinese Fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) Plantations. Forests 2023, 14, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smal, H.; Ligęza, S.; Pranagal, J.; Urban, D.; Pietruczyk-Popławska, D. Changes in the stocks of soil organic carbon, total nitrogen and phosphorus following afforestation of post-arable soils: A chronosequence study. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 451, 117536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ye, J.; Pei, J.; Fang, C.; Li, D.; Ke, W.; Song, X.; Sardans, J.; Peñuelas, J. Initial soil condition, stand age, and aridity alter the pathways for modifying the soil carbon under afforestation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ge, X.; Zhou, B.; Lei, L.; Xiao, W. Variations in rhizosphere soil total phosphorus and bioavailable phosphorus with respect to the stand age in Pinus massoniana Lamb. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 939683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, E.; Luo, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Chen, C.; Lu, X.; Jiang, L.; Luo, X.; Wen, D. Global meta-analysis shows pervasive phosphorus limitation of aboveground plant production in natural terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, B.L.; Brenes-Arguedas, T.; Condit, R. Pervasive phosphorus limitation of tree species but not communities in tropical forests. Nature 2018, 555, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yan, W.; Farooq, T.H.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Yuan, C.; Qi, Y.; Khan, K.A. Ecological stoichiometry of N and P across a chronosequence of Chinese fir plantation forests. Forests 2023, 14, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xiang, W.; Chen, L.; Ouyang, S.; Xiao, W.; Li, S.; Forrester, D.I.; Lei, P.; Zeng, Y.; Deng, X. Soil phosphorus bioavailability and recycling increased with stand age in Chinese fir plantations. Ecosystems 2020, 23, 973–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Xu, S.; Wang, G.G. Litter decomposition and nutrient release from monospecific and mixed litters: Comparisons of litter quality, fauna and decomposition site effects. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 1673–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, P.; Gong, L.; Chen, X.; Luo, Y.; Wu, X. Spatiotemporal variation and correlation of soil enzyme activities and soil physicochemical properties in canopy gaps of the Tianshan Mountains, Northwest China. J. Arid. Land 2022, 14, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Long, Q.; Chen, Y.; Duan, B.; Lu, X. Soil abiotic properties, not microbial composition or functional gene abundance, determine enzyme activities in alpine grassland soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2026, 217, 106645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Du, M.; Chen, J.; Tie, L.; Zhou, S.; Buckeridge, K.M.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Huang, C.; Kuzyakov, Y. Microbial necromass under global change and implications for soil organic matter. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 3503–3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babur, E.; Dindaroğlu, T.; Uslu, Ö.S.; Gozukara, G.; Ozlu, E. Long-Term Effects of Land Use Conversion on Soil Microbial Biomass and Stoichiometric Indices in Eastern Mediterranean Karst Ecosystems (1981–2018). Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 5666–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Gong, L.; Yang, L.; He, S.; Liu, X. Dynamics in C, N, and P stoichiometry and microbial biomass following soil depth and vegetation types in low mountain and hill region of China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Fang, X.; Wang, L.; Xiang, W.; Alharbi, H.A.; Lei, P.; Kuzyakov, Y. Regulation of soil phosphorus availability and composition during forest succession in subtropics. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 502, 119706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lladó, S.; López-Mondéjar, R.; Baldrian, P. Forest soil bacteria: Diversity, involvement in ecosystem processes, and response to global change. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2017, 81, e00063-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Zobel, M. How mycorrhizal associations drive plant population and community biology. Science 2020, 367, eaba1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooshammer, M.; Wanek, W.; Hämmerle, I.; Fuchslueger, L.; Hofhansl, F.; Knoltsch, A.; Schnecker, J.; Takriti, M.; Watzka, M.; Wild, B.; et al. Adjustment of microbial nitrogen use efficiency to carbon: Nitrogen imbalances regulates soil nitrogen cycling. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson-Teixeira, K.J.; Herrmann, V.; Morgan, R.B.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Cook-Patton, S.C.; Ferson, A.E.; Muller-Landau, H.C.; Wang, M.M. Carbon cycling in mature and regrowth forests globally. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 053009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Ma, W.; Song, L.; Tang, Y.; Long, Y.; Xu, G.; Yuan, J. Responses of soil N-cycle enzyme activities to vegetation degradation in a wet meadow on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1210643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiao, P.; Guo, W.; Du, D.; Hu, Y.; Tan, X.; Liu, X. Changes in bulk and rhizosphere soil microbial diversity and composition along an age gradient of Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolate) plantations in subtropical China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 777862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Hu, Y. Response of bacterial and fungal soil communities to Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolate) long-term monoculture plantations. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 10390:2021; Soil, Treated Biowaste and Sludge—Determination of pH. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Nelson, D.W.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. In Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 3 Chemical Methods; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1996; pp. 961–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Xu, Q.; Xu, Z.; Cao, Z. Seasonal changes in soil labile organic carbon pools within a Phyllostachys praecox stand under high rate fertilization and winter mulch in subtropical China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2006, 236, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, G.; Lefroy, R.; Lisle, L. Soil carbon fractions based on their degree of oxidation, and the development of a carbon management index for agricultural systems. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 1995, 46, 1459–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss Analytical AB. Manual for Kjeltec System 2300 Distilling and Titration Unit; Foss Analytical AB: Höganäs, Sweden, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldahl, J. Neue methode zur bestimmung des stickstoffs in organischen körpern. Z. Anorg. Chem. 1883, 22, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Mulvaney, R.; Hoeft, R. A simple soil test for detecting sites that are nonresponsive to nitrogen fertilization. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2001, 65, 1751–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M.; Mulvaney, C.S. Nitrogen—Total. In Methods of Soil Analysis. Part 2: Chemical and Microbiological Properties, 2nd ed.; Page, A.L., Miller, R.H., Keeney, D.R., Eds.; American Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1982; pp. 595–624. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, S.E. Chemical Analysis of Ecologicalmaterials; Blackwell Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, K. Analytical Methods of Soil and Agricultural Chemistry; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Xiao, H.; Tong, C. Methods and Applications of Soil Microbial Biomass Measurement; China Meteorological Press: Beijing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S. Soil Enzyme and Research Technology; Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin, R.; Yalcin, M.S.; Yildirim, D. Optimization of covalent immobilization of Trichoderma reesei cellulase onto modified ReliZyme HA403 and Sepabeads EC-EP supports for cellulose hydrolysis, in buffer and ionic liquids/buffer media. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German, D.P.; Weintraub, M.N.; Grandy, A.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Rinkes, Z.L.; Allison, S.D. Optimization of hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme methods for ecosystem studies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Cao, S.; Zheng, H.; Hu, D.; Lin, J.; Lin, H.; Hu, R.; Sun, Y.; Li, Y. Variation in the growth traits and wood properties of Chinese fir from six provinces of southern China. Forests 2016, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, P.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Trivedi, C.; Hu, H.; Anderson, I.C.; Jeffries, T.C.; Zhou, J.; Singh, B.K. Microbial regulation of the soil carbon cycle: Evidence from gene–enzyme relationships. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2593–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N. Embracing the unknown: Disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Qin, Q.; Ke, Q.; Chen, L.; Song, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, L.; Cao, J. Successive monoculture of Eucalyptus spp. alters the structure and network connectivity, rather than the assembly pattern of rhizosphere and bulk soil bacteria. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 203, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]