Aluminum Stress Stimulates Growth in Phyllostachys edulis Seedlings: Evidence from Phenotypic and Physiological Stress Resistance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Sample Treatment

2.4. Sample Analysis

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

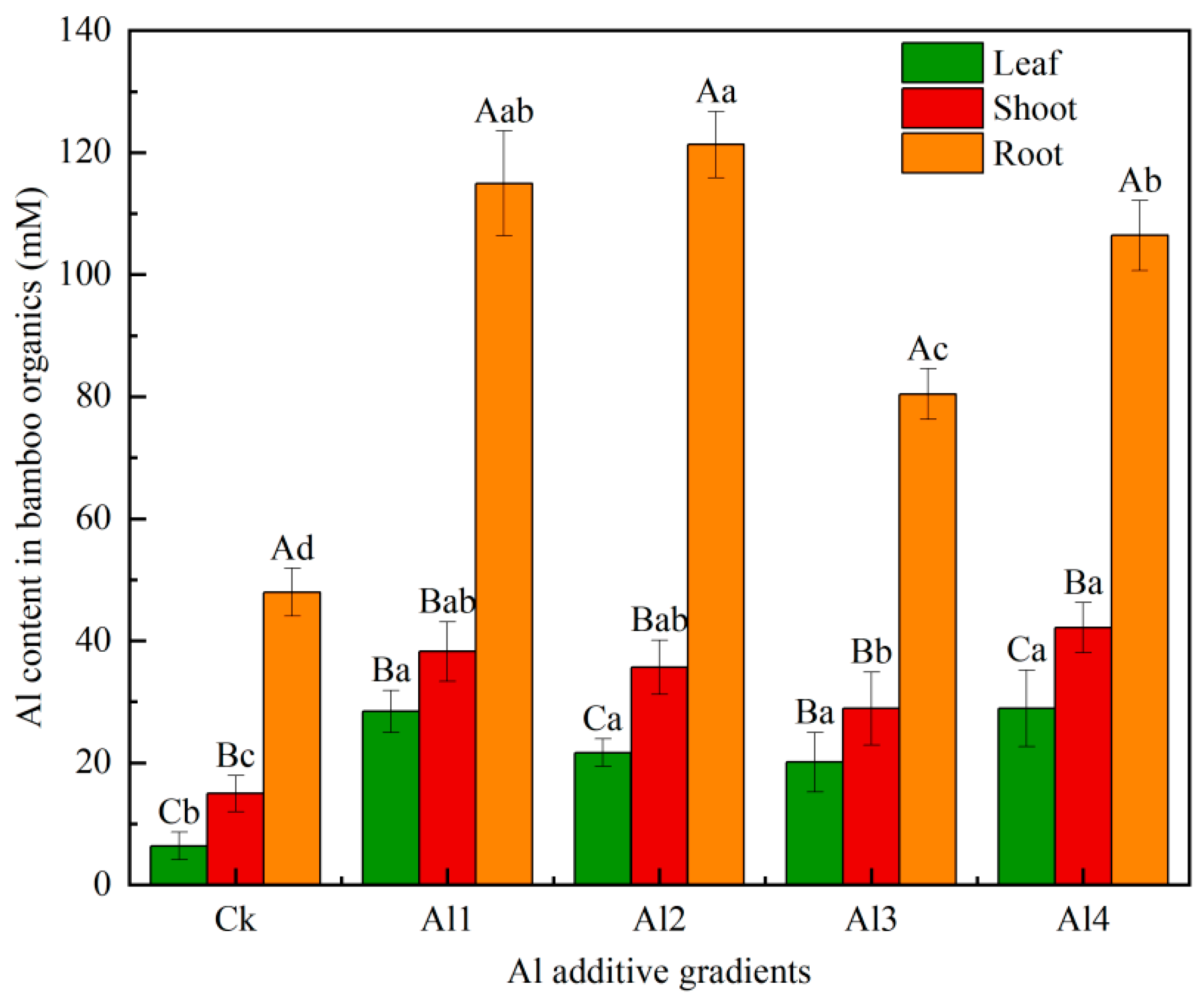

3.1. Comparison of Aluminum Content in P. edulis Seedlings Among Treatments

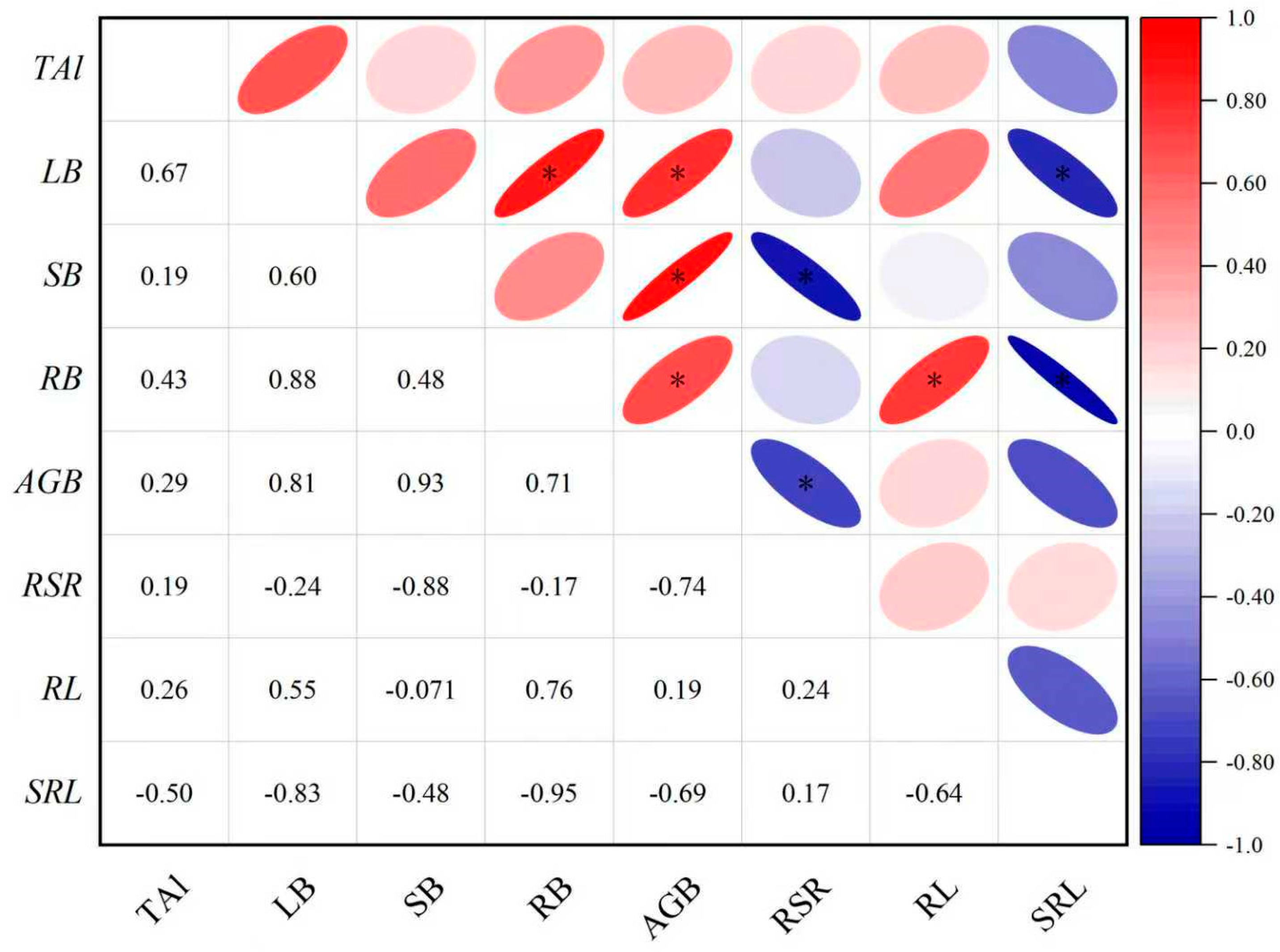

3.2. Differences in Growth Traits of P. edulis Seedlings with Aluminum Addition

3.3. Physiological Responses of P. edulis Seedlings Under Aluminum Treatment

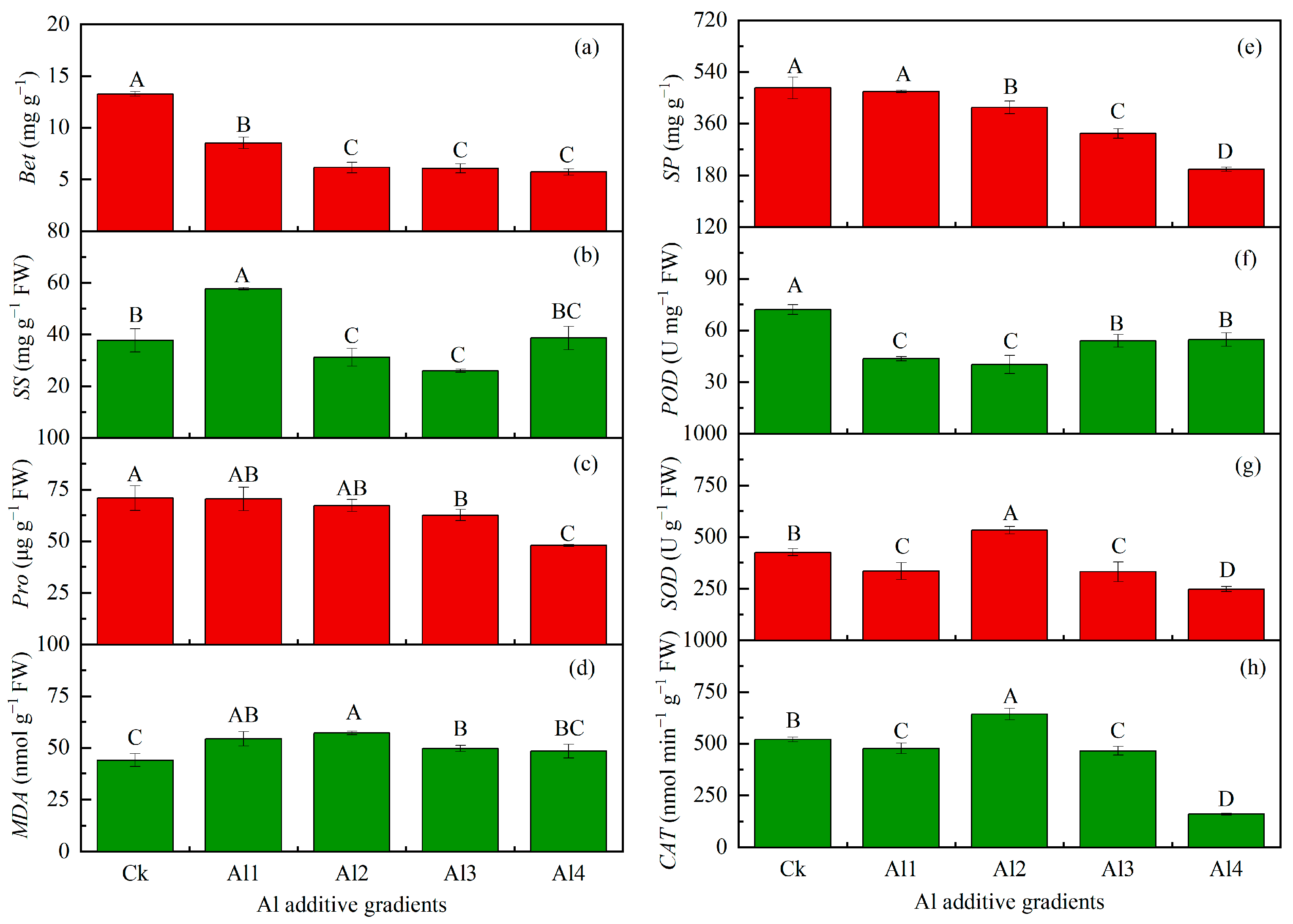

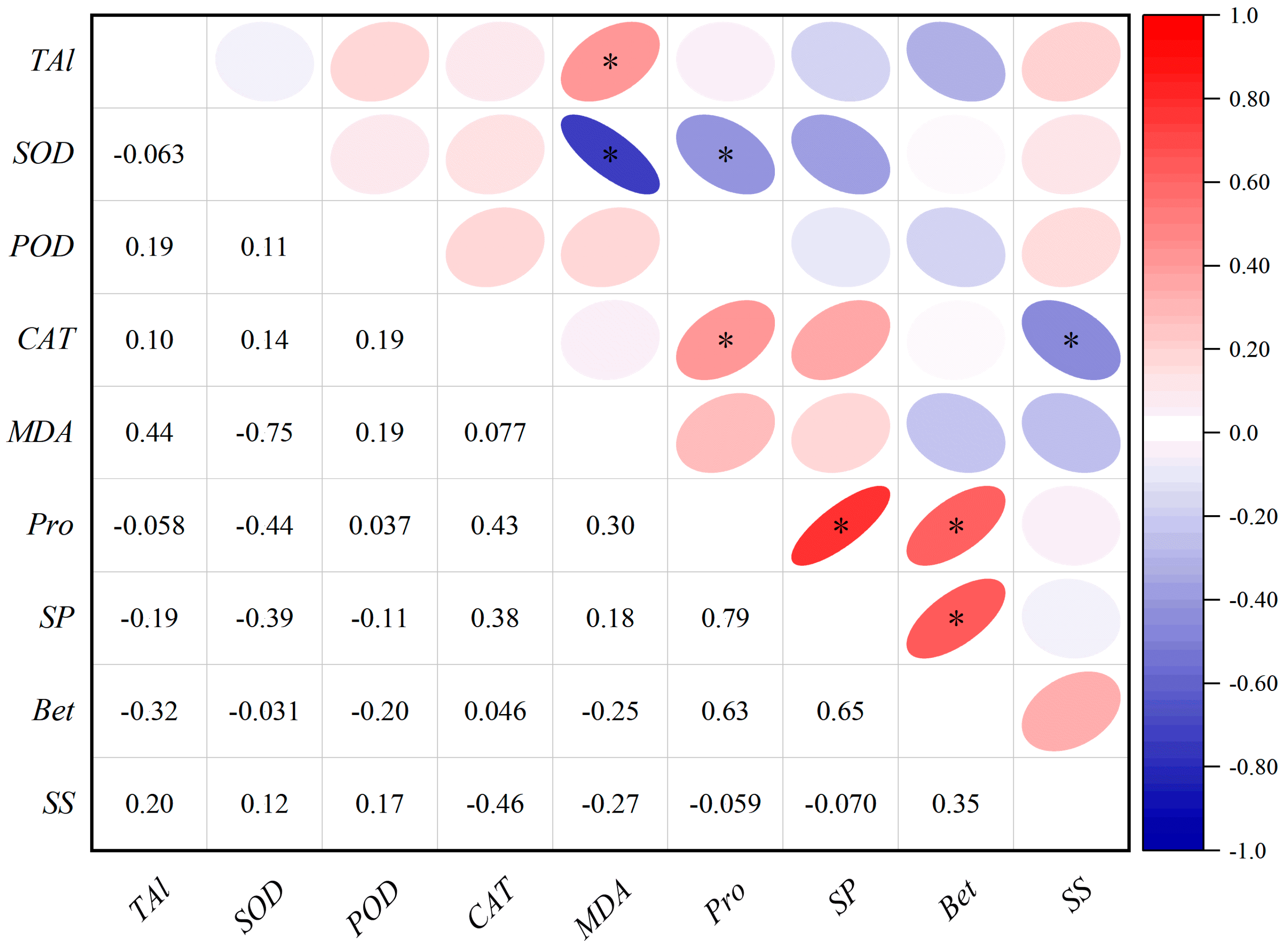

3.4. Correlation Between Morphological/Physiological Indicators and Aluminum Content in P. edulis

4. Discussion

4.1. Spatial Distribution of Aluminum in P. edulis and Its Effect on Phenotype

4.2. Physiological Responses of P. edulis to Aluminum Stress

4.3. Analysis of Aluminum Tolerance in P. edulis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LTAl | Leaf total aluminum concentration |

| STAl | Shoot total aluminum concentration |

| RTAl | Root total aluminum concentration |

| RL | Root length |

| LB | Leaf biomass |

| SB | Stem biomass |

| RB | Root biomass |

| AGB | Above-ground biomass |

| RSR | Root-to-shoot ratio |

| SRL | Specific root length |

| SOD | Superoxide dismutase |

| POD | Peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| SP | Soluble protein |

| Pro | Free proline |

| Bet | Betaine |

| SS | Soluble sugar |

References

- Von Uexküll, H.R.; Mutert, E. Global extent, development and economic impact of acid soils. Plant Soil 1995, 171, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J. Researches on the threshold of aluminum toxicity and the decline of Chinese fir plantation in hilly area around the Sichuan basin. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2000, 36, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, J.; Agrawal, S.B.; Agrawal, M. Global trends of acidity in rainfall and its impact on plants and soil. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2022, 23, 398–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ofoe, R.; Thomas, R.H.; Asiedu, S.K.; Wang-Pruski, G.; Fofana, B.; Abbey, L. Aluminum in plant: Benefits, toxicity and tolerance mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1085998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L. Acid sulfate soils and their management: A global perspective. In Proceedings of the 7th Acid Sulfate Soil Conference, Vassa, Finland, 26 August–1 September 2012; pp. 127–129. [Google Scholar]

- Slessarev, E.W.; Lin, Y.; Bingham, N.L.; Johnson, J.E.; Dai, Y.; Schimel, J.P.; Chadwick, O.A. Water balance creates a threshold in soil pH at the global scale. Nature 2016, 540, 567–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulding, K.W.T.; de Varennes, A. Soil acidification and the importance of liming agricultural soils with particular reference to the United Kingdom. Soil Use Manag. 2016, 32, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.; Upadhyaya, H. Aluminium toxicity and its tolerance in plant: A review. J. Plant Biol. 2020, 64, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochian, L.V. Cellular mechanisms of aluminum toxicity and resistance in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995, 46, 237–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.F.; Ferreira, B.G.; dos Santos Isaias, R.M.; Alexandre, S.S.; França, M.G.C. Immunocytochemistry and density functional theory evidence the competition of aluminum and calcium for pectin binding in Urochloa decumbens roots. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 153, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Tripathi, D.K.; Singh, S.; Sharma, S.; Dubey, N.K.; Chauhan, D.K.; Vaculík, M. Toxicity of aluminium on various levels of plant cells and organism: A review. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2017, 137, 177–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, N.; Zvobgo, G.; Zhang, G.-p. A review: The beneficial effects and possible mechanisms of aluminum on plant growth in acidic soil. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tao, J.; Cao, J.; Zeng, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, J.; Huang, Z.; Jiang, M.; Sun, L. The beneficial effects of aluminum on the plant growth in Camellia japonica. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2020, 20, 1799–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Lv, T.; Huang, L.; Liu, X.; Jin, C.; Lin, X. Melatonin ameliorates aluminum toxicity through enhancing aluminum exclusion and reestablishing redox homeostasis in roots of wheat. J. Pineal Res. 2020, 68, e12642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Jansen, S.; Osaki, M. The beneficial effect of aluminium and the role of citrate in Al accumulation in Melastoma malabathricum. New Phytol. 2004, 165, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochian, L.V.; Piñeros, M.A.; Liu, J.; Magalhaes, J.V. Plant adaptation to acid soils: The molecular basis for crop aluminum resistance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 571–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Activation and activity of STOP1 in aluminium resistance. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 2269–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Yue, T.; Jiang, P.; Zhou, G.; Liu, J. Effects of intensive management on soil C and N pools and soil enzyme activities in Moso bamboo plantations. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2016, 27, 3455–3462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poschenrieder, C.; Gunsé, B.; Corrales, I.; Barceló, J. A glance into aluminum toxicity and resistance in plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2008, 400, 356–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyaneza, V.; Zhang, W.; Haider, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, C.; Ding, G. Strategies for alleviating aluminum toxicity in soils and plants. Plant Soil 2024, 504, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, H. Cell biology of aluminum toxicity and tolerance in higher plants. Int. Rev. Cytol. 2000, 200, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengel, Z.; Elliott, D.C. Mechanism of aluminum inhibition of net 45Ca2+ uptake by Amaranthus Protoplasts. Plant Physiol. 1992, 98, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, J.; Babourina, O.; Rengel, Z. Role of magnesium in alleviation of aluminium toxicity in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 2251–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Feng, H.; Sun, K. Effects of different aluminum stress on the growth of rice roots. Bulletia Bot. Res. 2011, 31, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.J.; Yang, J.L.; He, Y.F.; Yu, X.H.; Zhang, L.; You, J.F.; Shen, R.F.; Matsumoto, H. Immobilization of aluminum with phosphorus in roots is associated with high aluminum resistance in buckwheat. Plant Physiol. 2005, 138, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.F.; Ma, J.F.; Matsumoto, H. Pattern of aluminum-induced secretion of organic acids differs between rye and wheat. Plant Physiol. 2000, 123, 1537–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Singha, L.; Khan, M. Does aluminium phytotoxicity induce oxidative stress in greengram (Vigna radiata). Bulg. J. Plant Physiol. 2003, 29, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Canavan, S.; Richardson, D.M.; Visser, V.; Roux, J.J.L.; Vorontsova, M.S.; Wilson, J.R.U. The global distribution of bamboos: Assessing correlates of introduction and invasion. AoB Plants 2016, 9, plw078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhuang, S.; Gui, R.; Ji, H.; Li, G.; Zheng, K. Chemical properties and distribution of phytotoxic Al species in intensively cultivated soils of Phyllostachys praecox stands. J. Zhejiang A F Univ. 2011, 28, 837–844. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Bo, M. Effects of different fertilizations on soil acidification of Phyllostachys heterocycla cv. Pubescens Stands. Zhejiang Acad. For. 2017, 37, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Li, G.; Gui, R.; Fang, W. Changes of aluminum form in Phyllostachy spraecox. Preveynalis soils with planting time. Soils 2008, 40, 1013–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Zhuang, S.; Liu, G.; Li, G.; Gui, R.; He, G. Effect of lei bamboo plantation on soil basic properties under intensive cultivation managemen. Soils 2009, 41, 784–789. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, H.; Sun, X.; Gui, R.; Zhuang, S. Influence of intensive management on soil extractable Al and Phyllostachys praecox Al content. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2014, 50, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zhou, G.; Qing, H.; Lin, L. Effect of long-term intensive management of Phyllostachys praecox stands on carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus pools in the soil. Acta Pedol. Sin. 2012, 49, 1170–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Wang, C.; Pan, X.; Bai, S. Effects of simulated acid rain on soil bacterial community diversity in buffer zone of broad-leaved forest invaded by moso bamboo. Res. Environ. Sci. 2020, 33, 1478–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Ding, A.; Hu, Q.; Meng, L. Effects of simulated acid rain on soil acidification and base ions transplant. J. Nanjing For. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2001, 25, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Xie, Y.; Yu, W.; Chen, S.; Guo, Z.; Xu, S.; Gi, R. Effects of long-term mulching on appearance, nutrition and taste of bamboo shoots of Phyllostachys violascens. J. Bamboo Res. 2021, 40, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, R.; Leng, H.; Zhuang, S.; Zheng, K.; Fang, W. Aluminum Tolerance in Moso Bamboo (Phyllostachys pubescens). Bot. Rev. 2011, 77, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Liu, P.; Xu, G.; Shen, L. Comparism of Plasma Membrane Response to Al3+ Stress Between Polygonaceae Plants and Gramineae Plants. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2005, 19, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weydert, C.J.; Cullen, J.J. Measurement of superoxide dismutase, catalase and glutathione peroxidase in cultured cells and tissue. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 5, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillo, P.; Gibon, Y. Protocol: Extraction and determination of proline. PrometheusWiki 2011, 2011, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Jack, C.N.; Rowe, S.L.; Porter, S.S.; Friesen, M.L. A high-throughput method of analyzing multiple plant defensive compounds in minimized sample mass. Appl. Plant Sci. 2019, 7, e01210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowra, U.; Yanase, E.; Koyama, H.; Panda, S.K. Aluminium-induced excessive ROS causes cellular damage and metabolic shifts in black gram Vigna mungo (L.) Hepper. Protoplasma 2016, 254, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorello, V.A.; Capaldi, F.R.; Stefanuto, V.A. Recent advances in aluminum toxicity and resistance in higher plants. Braz. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 17, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krstic, D.; Djalovic, I.; Nikezic, D.; Bjelic, D. Aluminium in acid soils: Chemistry, toxicity and impact on maize plants. Food Prod.–Approaches Chall. Tasks 2012, 13, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; XIao, B.; Yan, L.; Suo, L.; Gao, T.; Xiao, X. Effects of aluminum from fertilization on qualities and aluminum contents of tea under different pH levels in South Shaanxi Province. J. Northwest A F Univ. 2012, 40, 187–191+196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; He, L.; Zhang, A.; Men, Y. Advance in the study of effects of aluminum stress on plant photosynthesis and its mechanism. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. 2008, 27, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, B.; Wang, M.; Yu, C.; Weng, M. Physiological response and resistance of three cultivars of Acer rubrum L. to continuous drought stress. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2015, 35, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toufiq Iqbal, M. Effect of elevated Al and pH on the growth and root morphology of Al-tolerant and Al-sensitive wheat seedlings in an acid soil. Span. J. Soil Sci. 2014, 4, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiyama, K.O.; Kobayashi, J.; Ogita, N.; Ueda, M.; Kimura, S.; Maki, H.; Umeda, M. ATM-mediated phosphorylation of SOG1 is essential for the DNA damage response in Arabidopsis. EMBO Rep. 2013, 14, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; He, G. Effects of aluminum stress on the activities of SOD, POD, CAT and the contents of MDA in the seedlings of different wheat cultivars. Biotechnology 2006, 16, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Ma, H.; Chen, Y.; Lin, S. Physiological Response of Chinese Fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata) Seedlings Under Acid and/or Aluminum Stresses. Fujian J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 34, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M. Physiological Responses of Phyllostachys edulis to the Elevated O3, and CO2 Alone and in Combination Concentration. Master’s Thesis, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, X.; Xue, L.; Ren, X.; Feng, H.; Zheng, W.; Fu, J. Preliminary study on drought resistance of four broadleaved seedlings under water stress in south China. For. Res. 2011, 24, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, M.; He, R.; Pan, K.; Bao, F.; Ying, Y. Analysis of differential metabolites of Phyllostachys edulis shoots at different growth stages by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Sci. 2023, 44, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkan, I. ROS and RNS: Key signalling molecules in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3313–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čiamporová, M. Morphological and Structural Responses of Plant Roots to Aluminium at Organ, Tissue, and Cellular Levels. Biol. Plant. 2002, 45, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, C.; Liu, G. Respnses to aluminum stress and critical aluminum concentration of Cynodon dactylon. Chin. J. Trop. Crops 2015, 36, 645–649. [Google Scholar]

- Haftom, B.; Edossa, F.; Teklehaimanot, H.; Kassahun, T. Threshold aluminium toxicity in finger millet. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2017, 12, 1144–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmus, A.; Bigalke, M.; Valarezo, C.; Castillo, J.M.; Wilcke, W. Aluminum toxicity to tropical montane forest tree seedlings in southern Ecuador: Response of biomass and plant morphology to elevated Al concentrations. Plant Soil 2014, 382, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Chen, R. The aluminum toxicity of some crop seedlings in red soil of southern Hunan. J. Plant Nutr. Fertil. 1999, 5, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofoe, R.; Gunupuru, L.R.; Wang-Pruski, G.; Fofana, B.; Thomas, R.H.; Abbey, L. Seed priming with pyroligneous acid mitigates aluminum stress, and promotes tomato seed germination and seedling growth. Plant Stress 2022, 4, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, H.; Zheng, K.; Li, G.; Gui, Y. Aluminum stress with seed germination and seedling growth in Phyllostachys pubescens. J. Zhejiang For. Coll. 2010, 27, 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Gui, R.; Liu, G.; Zhuang, S.; Fang, W. Aluminum form and transformation in the soil of intensive farming bamboo forests of Phyllostachys praecox cv. Prevernalis. J. Bamboo Res. 2008, 27, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

| Treatment | LB (g) | SB (g) | RB (g) | AGB (g) | RSR | RL (g) | SRL (cm/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ck | 1.71 ± 0.02 d | 4.31 ± 0.22 c | 4.75 ± 0.14 e | 6.02 ± 0.24 b | 0.79 ± 0.01 c | 20.52 ± 1.05 c | 4.32 ± 0.14 a |

| Al1 | 2.16 ± 0.45 cd | 3.54 ± 0.23 d | 10.72 ± 0.09 d | 5.7 ± 0.68 b | 1.9 ± 0.21 a | 21.89 ± 0.66 Bc | 2.04 ± 0.04 b |

| Al2 | 3.66 ± 0.02 a | 5.0 ± 0.29 b | 18.38 ± 0.21 a | 8.66 ± 0.31 a | 1.43 ± 0.03 b | 24.76 ± 1.09 a | 1.35 ± 0.06 d |

| Al3 | 2.36 ± 0.25 c | 4.08 ± 0.15 c | 11.92 ± 0.41 c | 6.44 ± 0.4 b | 1.85 ± 0.05 a | 24.21 ± 0.73 ab | 2.03 ± 0.02 b |

| Al4 | 3.02 ± 0.31 b | 5.9 ± 0.12 a | 12.51 ± 0.2 b | 8.92 ± 0.43 a | 1.4 ± 0.05 b | 22.72 ± 0.79 b | 1.82 ± 0.05 c |

| F values | 24.583 | 55.332 | 1259.0 | 36.335 | 59.7 | 11.471 | 697.73 |

| p values | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | <0.001 *** | 0.001 ** | <0.001 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, Z.; Zhang, B.; Tu, J.; Peng, C.; Ai, W.; Yang, M.; Meng, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, C. Aluminum Stress Stimulates Growth in Phyllostachys edulis Seedlings: Evidence from Phenotypic and Physiological Stress Resistance. Forests 2025, 16, 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121855

He Z, Zhang B, Tu J, Peng C, Ai W, Yang M, Meng Y, Li M, Zhou C. Aluminum Stress Stimulates Growth in Phyllostachys edulis Seedlings: Evidence from Phenotypic and Physiological Stress Resistance. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121855

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Zhujun, Bin Zhang, Jia Tu, Chao Peng, Wensheng Ai, Ming Yang, Yong Meng, Meiqun Li, and Cheng Zhou. 2025. "Aluminum Stress Stimulates Growth in Phyllostachys edulis Seedlings: Evidence from Phenotypic and Physiological Stress Resistance" Forests 16, no. 12: 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121855

APA StyleHe, Z., Zhang, B., Tu, J., Peng, C., Ai, W., Yang, M., Meng, Y., Li, M., & Zhou, C. (2025). Aluminum Stress Stimulates Growth in Phyllostachys edulis Seedlings: Evidence from Phenotypic and Physiological Stress Resistance. Forests, 16(12), 1855. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121855